- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

A guide to critical appraisal of evidence

Fineout-Overholt, Ellen PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN

Ellen Fineout-Overholt is the Mary Coulter Dowdy Distinguished Professor of Nursing at the University of Texas at Tyler School of Nursing, Tyler, Tex.

The author has disclosed no financial relationships related to this article.

Critical appraisal is the assessment of research studies' worth to clinical practice. Critical appraisal—the heart of evidence-based practice—involves four phases: rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation. This article reviews each phase and provides examples, tips, and caveats to help evidence appraisers successfully determine what is known about a clinical issue. Patient outcomes are improved when clinicians apply a body of evidence to daily practice.

How do nurses assess the quality of clinical research? This article outlines a stepwise approach to critical appraisal of research studies' worth to clinical practice: rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation. When critical care nurses apply a body of valid, reliable, and applicable evidence to daily practice, patient outcomes are improved.

Critical care nurses can best explain the reasoning for their clinical actions when they understand the worth of the research supporting their practices. In c ritical appraisal , clinicians assess the worth of research studies to clinical practice. Given that achieving improved patient outcomes is the reason patients enter the healthcare system, nurses must be confident their care techniques will reliably achieve best outcomes.

Nurses must verify that the information supporting their clinical care is valid, reliable, and applicable. Validity of research refers to the quality of research methods used, or how good of a job researchers did conducting a study. Reliability of research means similar outcomes can be achieved when the care techniques of a study are replicated by clinicians. Applicability of research means it was conducted in a similar sample to the patients for whom the findings will be applied. These three criteria determine a study's worth in clinical practice.

Appraising the worth of research requires a standardized approach. This approach applies to both quantitative research (research that deals with counting things and comparing those counts) and qualitative research (research that describes experiences and perceptions). The word critique has a negative connotation. In the past, some clinicians were taught that studies with flaws should be discarded. Today, it is important to consider all valid and reliable research informative to what we understand as best practice. Therefore, the author developed the critical appraisal methodology that enables clinicians to determine quickly which evidence is worth keeping and which must be discarded because of poor validity, reliability, or applicability.

Evidence-based practice process

The evidence-based practice (EBP) process is a seven-step problem-solving approach that begins with data gathering (see Seven steps to EBP ). During daily practice, clinicians gather data supporting inquiry into a particular clinical issue (Step 0). The description is then framed as an answerable question (Step 1) using the PICOT question format ( P opulation of interest; I ssue of interest or intervention; C omparison to the intervention; desired O utcome; and T ime for the outcome to be achieved). 1 Consistently using the PICOT format helps ensure that all elements of the clinical issue are covered. Next, clinicians conduct a systematic search to gather data answering the PICOT question (Step 2). Using the PICOT framework, clinicians can systematically search multiple databases to find available studies to help determine the best practice to achieve the desired outcome for their patients. When the systematic search is completed, the work of critical appraisal begins (Step 3). The known group of valid and reliable studies that answers the PICOT question is called the body of evidence and is the foundation for the best practice implementation (Step 4). Next, clinicians evaluate integration of best evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and values to determine if the outcomes in the studies are realized in practice (Step 5). Because healthcare is a community of practice, it is important that experiences with evidence implementation be shared, whether the outcome is what was expected or not. This enables critical care nurses concerned with similar care issues to better understand what has been successful and what has not (Step 6).

Critical appraisal of evidence

The first phase of critical appraisal, rapid critical appraisal, begins with determining which studies will be kept in the body of evidence. All valid, reliable, and applicable studies on the topic should be included. This is accomplished using design-specific checklists with key markers of good research. When clinicians determine a study is one they want to keep (a “keeper” study) and that it belongs in the body of evidence, they move on to phase 2, evaluation. 2

In the evaluation phase, the keeper studies are put together in a table so that they can be compared as a body of evidence, rather than individual studies. This phase of critical appraisal helps clinicians identify what is already known about a clinical issue. In the third phase, synthesis, certain data that provide a snapshot of a particular aspect of the clinical issue are pulled out of the evaluation table to showcase what is known. These snapshots of information underpin clinicians' decision-making and lead to phase 4, recommendation. A recommendation is a specific statement based on the body of evidence indicating what should be done—best practice. Critical appraisal is not complete without a specific recommendation. Each of the phases is explained in more detail below.

Phase 1: Rapid critical appraisal . Rapid critical appraisal involves using two tools that help clinicians determine if a research study is worthy of keeping in the body of evidence. The first tool, General Appraisal Overview for All Studies (GAO), covers the basics of all research studies (see Elements of the General Appraisal Overview for All Studies ). Sometimes, clinicians find gaps in knowledge about certain elements of research studies (for example, sampling or statistics) and need to review some content. Conducting an internet search for resources that explain how to read a research paper, such as an instructional video or step-by-step guide, can be helpful. Finding basic definitions of research methods often helps resolve identified gaps.

To accomplish the GAO, it is best to begin with finding out why the study was conducted and how it answers the PICOT question (for example, does it provide information critical care nurses want to know from the literature). If the study purpose helps answer the PICOT question, then the type of study design is evaluated. The study design is compared with the hierarchy of evidence for the type of PICOT question. The higher the design falls within the hierarchy or levels of evidence, the more confidence nurses can have in its finding, if the study was conducted well. 3,4 Next, find out what the researchers wanted to learn from their study. These are called the research questions or hypotheses. Research questions are just what they imply; insufficient information from theories or the literature are available to guide an educated guess, so a question is asked. Hypotheses are reasonable expectations guided by understanding from theory and other research that predicts what will be found when the research is conducted. The research questions or hypotheses provide the purpose of the study.

Next, the sample size is evaluated. Expectations of sample size are present for every study design. As an example, consider as a rule that quantitative study designs operate best when there is a sample size large enough to establish that relationships do not exist by chance. In general, the more participants in a study, the more confidence in the findings. Qualitative designs operate best with fewer people in the sample because these designs represent a deeper dive into the understanding or experience of each person in the study. 5 It is always important to describe the sample, as clinicians need to know if the study sample resembles their patients. It is equally important to identify the major variables in the study and how they are defined because this helps clinicians best understand what the study is about.

The final step in the GAO is to consider the analyses that answer the study research questions or confirm the study hypothesis. This is another opportunity for clinicians to learn, as learning about statistics in healthcare education has traditionally focused on conducting statistical tests as opposed to interpreting statistical tests. Understanding what the statistics indicate about the study findings is an imperative of critical appraisal of quantitative evidence.

The second tool is one of the variety of rapid critical appraisal checklists that speak to validity, reliability, and applicability of specific study designs, which are available at varying locations (see Critical appraisal resources ). When choosing a checklist to implement with a group of critical care nurses, it is important to verify that the checklist is complete and simple to use. Be sure to check that the checklist has answers to three key questions. The first question is: Are the results of the study valid? Related subquestions should help nurses discern if certain markers of good research design are present within the study. For example, identifying that study participants were randomly assigned to study groups is an essential marker of good research for a randomized controlled trial. Checking these essential markers helps clinicians quickly review a study to check off these important requirements. Clinical judgment is required when the study lacks any of the identified quality markers. Clinicians must discern whether the absence of any of the essential markers negates the usefulness of the study findings. 6-9

The second question is: What are the study results? This is answered by reviewing whether the study found what it was expecting to and if those findings were meaningful to clinical practice. Basic knowledge of how to interpret statistics is important for understanding quantitative studies, and basic knowledge of qualitative analysis greatly facilitates understanding those results. 6-9

The third question is: Are the results applicable to my patients? Answering this question involves consideration of the feasibility of implementing the study findings into the clinicians' environment as well as any contraindication within the clinicians' patient populations. Consider issues such as organizational politics, financial feasibility, and patient preferences. 6-9

When these questions have been answered, clinicians must decide about whether to keep the particular study in the body of evidence. Once the final group of keeper studies is identified, clinicians are ready to move into the phase of critical appraisal. 6-9

Phase 2: Evaluation . The goal of evaluation is to determine how studies within the body of evidence agree or disagree by identifying common patterns of information across studies. For example, an evaluator may compare whether the same intervention is used or if the outcomes are measured in the same way across all studies. A useful tool to help clinicians accomplish this is an evaluation table. This table serves two purposes: first, it enables clinicians to extract data from the studies and place the information in one table for easy comparison with other studies; and second, it eliminates the need for further searching through piles of periodicals for the information. (See Bonus Content: Evaluation table headings .) Although the information for each of the columns may not be what clinicians consider as part of their daily work, the information is important for them to understand about the body of evidence so that they can explain the patterns of agreement or disagreement they identify across studies. Further, the in-depth understanding of the body of evidence from the evaluation table helps with discussing the relevant clinical issue to facilitate best practice. Their discussion comes from a place of knowledge and experience, which affords the most confidence. The patterns and in-depth understanding are what lead to the synthesis phase of critical appraisal.

The key to a successful evaluation table is simplicity. Entering data into the table in a simple, consistent manner offers more opportunity for comparing studies. 6-9 For example, using abbreviations versus complete sentences in all columns except the final one allows for ease of comparison. An example might be the dependent variable of depression defined as “feelings of severe despondency and dejection” in one study and as “feeling sad and lonely” in another study. 10 Because these are two different definitions, they need to be different dependent variables. Clinicians must use their clinical judgment to discern that these different dependent variables require different names and abbreviations and how these further their comparison across studies.

Sample and theoretical or conceptual underpinnings are important to understanding how studies compare. Similar samples and settings across studies increase agreement. Several studies with the same conceptual framework increase the likelihood of common independent variables and dependent variables. The findings of a study are dependent on the analyses conducted. That is why an analysis column is dedicated to recording the kind of analysis used (for example, the name of the statistical analyses for quantitative studies). Only statistics that help answer the clinical question belong in this column. The findings column must have a result for each of the analyses listed; however, in the actual results, not in words. For example, a clinician lists a t -test as a statistic in the analysis column, so a t -value should reflect whether the groups are different as well as probability ( P -value or confidence interval) that reflects statistical significance. The explanation for these results would go in the last column that describes worth of the research to practice. This column is much more flexible and contains other information such as the level of evidence, the studies' strengths and limitations, any caveats about the methodology, or other aspects of the study that would be helpful to its use in practice. The final piece of information in this column is a recommendation for how this study would be used in practice. Each of the studies in the body of evidence that addresses the clinical question is placed in one evaluation table to facilitate the ease of comparing across the studies. This comparison sets the stage for synthesis.

Phase 3: Synthesis . In the synthesis phase, clinicians pull out key information from the evaluation table to produce a snapshot of the body of evidence. A table also is used here to feature what is known and help all those viewing the synthesis table to come to the same conclusion. A hypothetical example table included here demonstrates that a music therapy intervention is effective in reducing the outcome of oxygen saturation (SaO 2 ) in six of the eight studies in the body of evidence that evaluated that outcome (see Sample synthesis table: Impact on outcomes ). Simply using arrows to indicate effect offers readers a collective view of the agreement across studies that prompts action. Action may be to change practice, affirm current practice, or conduct research to strengthen the body of evidence by collaborating with nurse scientists.

When synthesizing evidence, there are at least two recommended synthesis tables, including the level-of-evidence table and the impact-on-outcomes table for quantitative questions, such as therapy or relevant themes table for “meaning” questions about human experience. (See Bonus Content: Level of evidence for intervention studies: Synthesis of type .) The sample synthesis table also demonstrates that a final column labeled synthesis indicates agreement across the studies. Of the three outcomes, the most reliable for clinicians to see with music therapy is SaO 2 , with positive results in six out of eight studies. The second most reliable outcome would be reducing increased respiratory rate (RR). Parental engagement has the least support as a reliable outcome, with only two of five studies showing positive results. Synthesis tables make the recommendation clear to all those who are involved in caring for that patient population. Although the two synthesis tables mentioned are a great start, the evidence may require more synthesis tables to adequately explain what is known. These tables are the foundation that supports clinically meaningful recommendations.

Phase 4: Recommendation . Recommendations are definitive statements based on what is known from the body of evidence. For example, with an intervention question, clinicians should be able to discern from the evidence if they will reliably get the desired outcome when they deliver the intervention as it was in the studies. In the sample synthesis table, the recommendation would be to implement the music therapy intervention across all settings with the population, and measure SaO 2 and RR, with the expectation that both would be optimally improved with the intervention. When the synthesis demonstrates that studies consistently verify an outcome occurs as a result of an intervention, however that intervention is not currently practiced, care is not best practice. Therefore, a firm recommendation to deliver the intervention and measure the appropriate outcomes must be made, which concludes critical appraisal of the evidence.

A recommendation that is off limits is conducting more research, as this is not the focus of clinicians' critical appraisal. In the case of insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for practice change, the recommendation would be to continue current practice and monitor outcomes and processes until there are more reliable studies to be added to the body of evidence. Researchers who use the critical appraisal process may indeed identify gaps in knowledge, research methods, or analyses, for example, that they then recommend studies that would fill in the identified gaps. In this way, clinicians and nurse scientists work together to build relevant, efficient bodies of evidence that guide clinical practice.

Evidence into action

Critical appraisal helps clinicians understand the literature so they can implement it. Critical care nurses have a professional and ethical responsibility to make sure their care is based on a solid foundation of available evidence that is carefully appraised using the phases outlined here. Critical appraisal allows for decision-making based on evidence that demonstrates reliable outcomes. Any other approach to the literature is likely haphazard and may lead to misguided care and unreliable outcomes. 11 Evidence translated into practice should have the desired outcomes and their measurement defined from the body of evidence. It is also imperative that all critical care nurses carefully monitor care delivery outcomes to establish that best outcomes are sustained. With the EBP paradigm as the basis for decision-making and the EBP process as the basis for addressing clinical issues, critical care nurses can improve patient, provider, and system outcomes by providing best care.

Seven steps to EBP

Step 0–A spirit of inquiry to notice internal data that indicate an opportunity for positive change.

Step 1– Ask a clinical question using the PICOT question format.

Step 2–Conduct a systematic search to find out what is already known about a clinical issue.

Step 3–Conduct a critical appraisal (rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation).

Step 4–Implement best practices by blending external evidence with clinician expertise and patient preferences and values.

Step 5–Evaluate evidence implementation to see if study outcomes happened in practice and if the implementation went well.

Step 6–Share project results, good or bad, with others in healthcare.

Adapted from: Steps of the evidence-based practice (EBP) process leading to high-quality healthcare and best patient outcomes. © Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2017. Used with permission.

Critical appraisal resources

- The Joanna Briggs Institute http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists

- Center for Evidence-Based Medicine www.cebm.net/critical-appraisal

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

A full set of critical appraisal checklists are available in the appendices.

Bonus content!

This article includes supplementary online-exclusive material. Visit the online version of this article at www.nursingcriticalcare.com to access this content.

critical appraisal; decision-making; evaluation of research; evidence-based practice; synthesis

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Determining the level of evidence: experimental research appraisal, caring for hospitalized patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, the qt interval, evidence-based practice for red blood cell transfusions, searching with critical appraisal tools.

- Teesside University Student & Library Services

- Learning Hub Group

Critical Appraisal for Health Students

- Critical Appraisal of a quantitative paper

- Critical Appraisal: Help

- Critical Appraisal of a qualitative paper

- Useful resources

Appraisal of a Quantitative paper: Top tips

- Introduction

Critical appraisal of a quantitative paper (RCT)

This guide, aimed at health students, provides basic level support for appraising quantitative research papers. It's designed for students who have already attended lectures on critical appraisal. One framework for appraising quantitative research (based on reliability, internal and external validity) is provided and there is an opportunity to practise the technique on a sample article.

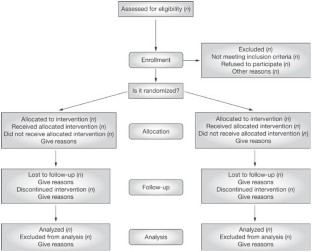

Please note this framework is for appraising one particular type of quantitative research a Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) which is defined as

a trial in which participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more groups: the experimental group or groups receive the intervention or interventions being tested; the comparison group (control group) receive usual care or no treatment or a placebo. The groups are then followed up to see if there are any differences between the results. This helps in assessing the effectiveness of the intervention.(CASP, 2020)

Support materials

- Framework for reading quantitative papers (RCTs)

- Critical appraisal of a quantitative paper PowerPoint

To practise following this framework for critically appraising a quantitative article, please look at the following article:

Marrero, D.G. et al. (2016) 'Comparison of commercial and self-initiated weight loss programs in people with prediabetes: a randomized control trial', AJPH Research , 106(5), pp. 949-956.

Critical Appraisal of a quantitative paper (RCT): practical example

- Internal Validity

- External Validity

- Reliability Measurement Tool

How to use this practical example

Using the framework, you can have a go at appraising a quantitative paper - we are going to look at the following article:

Marrero, d.g. et al (2016) 'comparison of commercial and self-initiated weight loss programs in people with prediabetes: a randomized control trial', ajph research , 106(5), pp. 949-956., step 1. take a quick look at the article, step 2. click on the internal validity tab above - there are questions to help you appraise the article, read the questions and look for the answers in the article. , step 3. click on each question and our answers will appear., step 4. repeat with the other aspects of external validity and reliability. , questioning the internal validity:, randomisation : how were participants allocated to each group did a randomisation process taken place, comparability of groups: how similar were the groups eg age, sex, ethnicity – is this made clear, blinding (none, single, double or triple): who was not aware of which group a patient was in (eg nobody, only patient, patient and clinician, patient, clinician and researcher) was it feasible for more blinding to have taken place , equal treatment of groups: were both groups treated in the same way , attrition : what percentage of participants dropped out did this adversely affect one group has this been evaluated, overall internal validity: does the research measure what it is supposed to be measuring, questioning the external validity:, attrition: was everyone accounted for at the end of the study was any attempt made to contact drop-outs, sampling approach: how was the sample selected was it based on probability or non-probability what was the approach (eg simple random, convenience) was this an appropriate approach, sample size (power calculation): how many participants was a sample size calculation performed did the study pass, exclusion/ inclusion criteria: were the criteria set out clearly were they based on recognised diagnostic criteria, what is the overall external validity can the results be applied to the wider population, questioning the reliability (measurement tool) internal validity:, internal consistency reliability (cronbach’s alpha). has a cronbach’s alpha score of 0.7 or above been included, test re-test reliability correlation. was the test repeated more than once were the same results received has a correlation coefficient been reported is it above 0.7 , validity of measurement tool. is it an established tool if not what has been done to check if it is reliable pilot study expert panel literature review criterion validity (test against other tools): has a criterion validity comparison been carried out was the score above 0.7, what is the overall reliability how consistent are the measurements , overall validity and reliability:, overall how valid and reliable is the paper.

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal of a qualitative paper

- Next: Useful resources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:37 PM

- URL: https://libguides.tees.ac.uk/critical_appraisal

Research Evaluation

- First Online: 23 June 2020

Cite this chapter

- Carlo Ghezzi 2

1041 Accesses

1 Citations

- The original version of this chapter was revised. A correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_7

This chapter is about research evaluation. Evaluation is quintessential to research. It is traditionally performed through qualitative expert judgement. The chapter presents the main evaluation activities in which researchers can be engaged. It also introduces the current efforts towards devising quantitative research evaluation based on bibliometric indicators and critically discusses their limitations, along with their possible (limited and careful) use.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Change history

19 october 2021.

The original version of the chapter was inadvertently published with an error. The chapter has now been corrected.

Notice that the taxonomy presented in Box 5.1 does not cover all kinds of scientific papers. As an example, it does not cover survey papers, which normally are not submitted to a conference.

Private institutions and industry may follow different schemes.

Adler, R., Ewing, J., Taylor, P.: Citation statistics: A report from the international mathematical union (imu) in cooperation with the international council of industrial and applied mathematics (iciam) and the institute of mathematical statistics (ims). Statistical Science 24 (1), 1–14 (2009). URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/20697661

Esposito, F., Ghezzi, C., Hermenegildo, M., Kirchner, H., Ong, L.: Informatics Research Evaluation. Informatics Europe (2018). URL https://www.informatics-europe.org/publications.html

Friedman, B., Schneider, F.B.: Incentivizing quality and impact: Evaluating scholarship in hiring, tenure, and promotion. Computing Research Association (2016). URL https://cra.org/resources/best-practice-memos/incentivizing-quality-and-impact-evaluating-scholarship-in-hiring-tenure-and-promotion/

Hicks, D., Wouters, P., Waltman, L., de Rijcke, S., Rafols, I.: Bibliometrics: The leiden manifesto for research metrics. Nature News 520 (7548), 429 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/520429a . URL http://www.nature.com/news/bibliometrics-the-leiden-manifesto-for-research-metrics-1.17351

Parnas, D.L.: Stop the numbers game. Commun. ACM 50 (11), 19–21 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1145/1297797.1297815 . URL http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1297797.1297815

Patterson, D., Snyder, L., Ullman, J.: Evaluating computer scientists and engineers for promotion and tenure. Computing Research Association (1999). URL https://cra.org/resources/best-practice-memos/incentivizing-quality-and-impact-evaluating-scholarship-in-hiring-tenure-and-promotion/

Saenen, B., Borrell-Damian, L.: Reflections on University Research Assessment: key concepts, issues and actors. European University Association (2019). URL https://eua.eu/component/attachments/attachments.html?id=2144

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dipartimento di Elettronica, Informazione e Bioingegneria, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Carlo Ghezzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carlo Ghezzi .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ghezzi, C. (2020). Research Evaluation. In: Being a Researcher. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_5

Published : 23 June 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-45156-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-45157-8

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Introduction

- Related Guides

- Getting Help

Critical Appraisal of Studies

Critical appraisal is the process of carefully and systematically examining research to judge its trustworthiness, and its value/relevance in a particular context by providing a framework to evaluate the research. During the critical appraisal process, researchers can:

- Decide whether studies have been undertaken in a way that makes their findings reliable as well as valid and unbiased

- Make sense of the results

- Know what these results mean in the context of the decision they are making

- Determine if the results are relevant to their patients/schoolwork/research

Burls, A. (2009). What is critical appraisal? In What Is This Series: Evidence-based medicine. Available online at What is Critical Appraisal?

Critical appraisal is included in the process of writing high quality reviews, like systematic and integrative reviews and for evaluating evidence from RCTs and other study designs. For more information on systematic reviews, check out our Systematic Review guide.

- Next: Critical Appraisal Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duq.edu/critappraise

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

99 Citations

448 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical History

- Classical Reception

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

3 Critically Appraising the Quality and Credibility of Quantitative Research for Systematic Reviews

- Published: September 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter looks at how to evaluate the quality and credibility of various types of quantitative research that might be included in a systematic review. Various factors that determine the quality and believability of a study will be presented, including, • assessing the study’s methods in terms of internal validity • examining factors associated with external validity and relevance; and • evaluating the credibility of the research and researcher in terms of possible biases that might influence the research design, analysis, or conclusions. The importance of transparency is highlighted.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 9 |

| November 2022 | 10 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| February 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 13 |

| May 2023 | 12 |

| June 2023 | 2 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 18 |

| February 2024 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 17 |

| May 2024 | 20 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Appraising Quantitative Research in Health Education: Guidelines for Public Health Educators

Leonard jack, jr..

Associate Dean for Research and Endowed Chair of Minority Health Disparities, College of Pharmacy, Xavier University of Louisiana, 1 Drexel Drive, New Orleans, Louisiana 70125; Telephone: 504-520-5345; Fax: 504-520-7971

Sandra C. Hayes

Central Mississippi Area Health Education Center, 350 West Woodrow Wilson, Suite 3320, Jackson, MS 39213; Telephone: 601-987-0272; Fax: 601-815-5388

Jeanfreau G. Scharalda

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center School of Nursing, 1900 Gravier Street, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112; Telephone: 504-568-4140; Fax: 504-568-5853

Barbara Stetson

Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, 317 Life Sciences Building, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292; Telephone: 502-852-2540; Fax: 502-852-8904

Nkenge H. Jones-Jack

Epidemiologist & Evaluation Consultant, Metairie, Louisiana 70002. Telephone: 678-524-1147; Fax: 504-267-4080

Matthew Valliere