Is Google Making Us Stupid?

24 pages • 48 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Essay Analysis Story Analysis

Analysis: “is google making us stupid”.

In this essay, Carr asserts that the Internet, rather than Google specifically or exclusively, is in the process of revolutionizing human consciousness and cognition. For Carr, this is a negative revolution that threatens to evacuate human intellectual inquiry of its nuance, and to squeeze human interactions with both complex ideas and our own intellectual lives into a dangerously oversimplified mechanism designed only to create productivity and efficiency: two things that he sees as antithetical to a robust intellectual life.

Related Titles

By Nicholas Carr

The Shallows

Featured Collections

Essays & Speeches

View Collection

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Future of the Internet IV

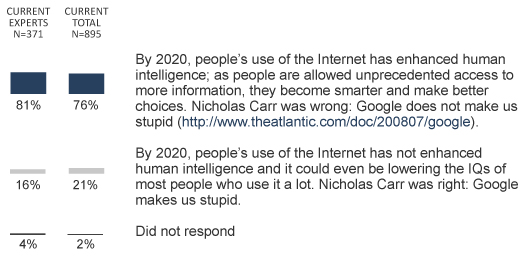

- Part 1: A review of responses to a tension pair about whether Google will make people stupid.

Table of Contents

- Part 2: A review of responses to a tension pair about the impact of the internet on reading, writing, and the rendering of knowledge

- Part 3: A review of responses to a tension pair about how takeoff technologies will emerge in the future

- Part 4: A review of responses to a tension pair about the evolution of the architecture and structure of the Internet: Will the Internet still be dominated by the end-to-end principle?

- Part 5: A review of responses to a tension pair about the future of anonymity online

The future of intelligence

Eminent tech scholar and analyst Nicholas Carr wrote a provocative cover story for the Atlantic Monthly magazine in the summer of 2008 1 with the cover line: “ Is Google Making us Stupid ?” He argued that the ease of online searching and distractions of browsing through the web were possibly limiting his capacity to concentrate. “I’m not thinking the way I used to,” he wrote, in part because he is becoming a skimming, browsing reader, rather than a deep and engaged reader. “The kind of deep reading that a sequence of printed pages promotes is valuable not just for the knowledge we acquire from the author’s words but for the intellectual vibrations those words set off within our own minds. In the quiet spaces opened up by the sustained, undistracted reading of a book, or by any other act of contemplation, for that matter, we make our own associations, draw our own inferences and analogies, foster our own ideas…. If we lose those quiet spaces, or fill them up with ‘content,’ we will sacrifice something important not only in our selves but in our culture.”

Jamais Cascio, an affiliate at the Institute for the Future and senior fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, challenged Carr in a subsequent article in the Atlantic Monthly ( http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200907/intelligence ). Cascio made the case that the array of problems facing humanity — the end of the fossil-fuel era, the fragility of the global food web, growing population density, and the spread of pandemics, among others – will force us to get smarter if we are to survive. “Most people don’t realize that this process is already under way,” he wrote. “In fact, it’s happening all around us, across the full spectrum of how we understand intelligence. It’s visible in the hive mind of the Internet, in the powerful tools for simulation and visualization that are jump-starting new scientific disciplines, and in the development of drugs that some people (myself included) have discovered let them study harder, focus better, and stay awake longer with full clarity.” He argued that while the proliferation of technology and media can challenge humans’ capacity to concentrate there were signs that we are developing “fluid intelligence—the ability to find meaning in confusion and solve new problems, independent of acquired knowledge.” He also expressed hope that techies will develop tools to help people find and assess information smartly.

With that as backdrop, respondents were asked to explain their answer to the tension pair statements and “share your view of the Internet’s influence on the future of human intelligence in 2020 – what is likely to stay the same and what will be different in the way human intellect evolves?” What follows is a selection of the hundreds of written elaborations and some of the recurring themes in those answers:

Nicholas Carr and Google staffers have their say

“I feel compelled to agree with myself. But I would add that the Net’s effect on our intellectual lives will not be measured simply by average IQ scores. What the Net does is shift the emphasis of our intelligence, away from what might be called a meditative or contemplative intelligence and more toward what might be called a utilitarian intelligence. The price of zipping among lots of bits of information is a loss of depth in our thinking.”– Nicholas Carr

[the institution of time-management and worker-activity standards in industrial settings]

“Google will make us more informed. The smartest person in the world could well be behind a plow in China or India. Providing universal access to information will allow such people to realize their full potential, providing benefits to the entire world.” – Hal Varian, Google, chief economist

The resources of the internet and search engines will shift cognitive capacities. We won’t have to remember as much, but we’ll have to think harder and have better critical thinking and analytical skills. Less time devoted to memorization gives people more time to master those new skills.

“Google allows us to be more creative in approaching problems and more integrative in our thinking. We spend less time trying to recall and more time generating solutions.” – Paul Jones , ibiblio, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

“Google will make us stupid and intelligent at the same time. In the future, we will live in a transparent 3D mobile media cloud that surrounds us everywhere. In this cloud, we will use intelligent machines, to whom we delegate both simple and complex tasks. Therefore, we will loose the skills we needed in the old days (e.g., reading paper maps while driving a car). But we will gain the skill to make better choices (e.g., knowing to choose the mortgage that is best for you instead of best for the bank). All in all, I think the gains outweigh the losses.” — Marcel Bullinga , Dutch Futurist at futurecheck.com

“I think that certain tasks will be “offloaded” to Google or other Internet services rather than performed in the mind, especially remembering minor details. But really, that a role that paper has taken over many centuries: did Gutenberg make us stupid? On the other hand, the Internet is likely to be front-and-centre in any developments related to improvements in neuroscience and human cognition research.” – Dean Bubley, wireless industry consultant

“What the internet (here subsumed tongue-in-cheek under “Google”) does is to support SOME parts of human intelligence, such as analysis, by REPLACING other parts such as memory. Thus, people will be more intelligent about, say, the logistics of moving around a geography because “Google” will remember the facts and relationships of various locations on their behalf. People will be better able to compare the revolutions of 1848 and 1789 because “Google” will remind them of all the details as needed. This is the continuation ad infinitum of the process launched by abacuses and calculators: we have become more “stupid” by losing our arithmetic skills but more intelligent at evaluating numbers.” – Andreas Kluth, writer, Economist magazine

“It’s a mistake to treat intelligence as an undifferentiated whole. No doubt we will become worse at doing some things (‘more stupid’) requiring rote memory of information that is now available though Google. But with this capacity freed, we may (and probably will) be capable of more advanced integration and evaluation of information (‘more intelligent’).” – Stephen Downes, National Research Council, Canada

“The new learning system, more informal perhaps than formal, will eventually win since we must use technology to cause everyone to learn more, more economically and faster if everyone is to be economically productive and prosperous. Maintaining the status quo will only continue the existing win/lose society that we have with those who can learn in present school structure doing ok, while more and more students drop out, learn less, and fail to find a productive niche in the future.” – Ed Lyell , former member of the Colorado State Board of Education and Telecommunication Advisory Commission

“The question is flawed: Google will make intelligence different. As Carr himself suggests, Plato argued that reading and writing would make us stupid, and from the perspective of a preliterate, he was correct. Holding in your head information that is easily discoverable on Google will no longer be a mark of intelligence, but a side-show act. Being able to quickly and effectively discover information and solve problems, rather than do it “in your head,” will be the metric we use.” – Alex Halavais , vice president, Association of Internet Researchers

“What Google does do is simply to enable us to shift certain tasks to the network – we no longer need to rote-learn certain seldomly-used facts (the periodic table, the post code of Ballarat) if they’re only a search away, for example. That’s problematic, of course – we put an awful amount of trust in places such as Wikipedia where such information is stored, and in search engines like Google through which we retrieve it – but it doesn’t make us stupid, any more than having access to a library (or in fact, access to writing) makes us stupid. That said, I don’t know that the reverse is true, either: Google and the Net also don’t automatically make us smarter. By 2020, we will have even more access to even more information, using even more sophisticated search and retrieval tools – but how smartly we can make use of this potential depends on whether our media literacies and capacities have caught up, too.” – Axel Bruns, Associate Professor, Queensland University of Technology

“My ability to do mental arithmetic is worse than my grandfathers because I grew up in an era with pervasive personal calculators…. I am not stupid compared to my grandfather, but I believe the development of my brain has been changed by the availability of technology. The same will happen (or is happening) as a result of the Googleization of knowledge. People are becoming used to bite sized chunks of information that are compiled and sorted by an algorithm. This must be having an impact on our brains, but it is too simplistic to say that we are becoming stupid as a result of Google.” – Robert Acklund, Australian National University

“We become adept at using useful tools, and hence perfect new skills. Other skills may diminish. I agree with Carr that we may on the average become less patient, less willing to read through a long, linear text, but we may also become more adept at dealing with multiple factors…. Note that I said ‘less patient,’ which is not the same as ‘lower IQ.’ I suspect that emotional and personality changes will probably more marked than ‘intelligence’ changes.” – Larry Press , California State University, Dominguz Hills

Technology isn’t the problem here. It is people’s inherent character traits. The internet and search engines just enable people to be more of what they already are. If they are motivated to learn and shrewd, they will use new tools to explore in exciting new ways. If they are lazy or incapable of concentrating, they will find new ways to be distracted and goof off.

“The question is all about people’s choices. If we value introspection as a road to insight, if we believe that long experience with issues contributes to good judgment on those issues, if we (in short) want knowledge that search engines don’t give us, we’ll maintain our depth of thinking and Google will only enhance it. There is a trend, of course, toward instant analysis and knee-jerk responses to events that degrades a lot of writing and discussion. We can’t blame search engines for that…. What search engines do is provide more information, which we can use either to become dilettantes (Carr’s worry) or to bolster our knowledge around the edges and do fact-checking while we rely mostly on information we’ve gained in more robust ways for our core analyses. Google frees the time we used to spend pulling together the last 10% of facts we need to complete our research. I read Carr’s article when The Atlantic first published it, but I used a web search to pull it back up and review it before writing this response. Google is my friend.” – Andy Oram , editor and blogger, O’Reilly Media

“For people who are readers and who are willing to explore new sources and new arguments, we can only be made better by the kinds of searches we will be able to do. Of course, the kind of Googled future that I am concerned about is the one in which my every desire is anticipated, and my every fear avoided by my guardian Google. Even then, I might not be stupid, just not terribly interesting.” – Oscar Gandy, emeritus professor, University of Pennsylvania

“I don’t think having access to information can ever make anyone stupider. I don’t think an adult’s IQ can be influenced much either way by reading anything and I would guess that smart people will use the Internet for smart things and stupid people will use it for stupid things in the same way that smart people read literature and stupid people read crap fiction. On the whole, having easy access to more information will make society as a group smarter though.” – Sandra Kelly, market researcher, 3M Corporation

“The story of humankind is that of work substitution and human enhancement. The Neolithic revolution brought the substitution of some human physical work by animal work. The Industrial revolution brought more substitution of human physical work by machine work. The Digital revolution is implying a significant substitution of human brain work by computers and ICTs in general. Whenever a substitution has taken place, men have been able to focus on more qualitative tasks, entering a virtuous cycle: the more qualitative the tasks, the more his intelligence develops; and the more intelligent he gets, more qualitative tasks he can perform…. As obesity might be the side-effect of physical work substitution my machines, mental laziness can become the watermark of mental work substitution by computers, thus having a negative effect instead of a positive one.” – Ismael Pe ñ a-Lopez , lecturer at the Open University of Catalonia, School of Law and Political Science

“Well, of course, it depends on what one means by ‘stupid’ — I imagine that Google, and its as yet unimaginable new features and capabilities will both improve and decrease some of our human capabilities. Certainly it’s much easier to find out stuff, including historical, accurate, and true stuff, as well as entertaining, ironic, and creative stuff. It’s also making some folks lazier, less concerned about investing in the time and energy to arrive at conclusions, etc.” – Ron Rice, University of California, Santa Barbara

“Google isn’t making us stupid – but it is making many of us intellectually lazy. This has already become a big problem in university classrooms. For my undergrad majors in Communication Studies, Google may take over the hard work involved in finding good source material for written assignments. Unless pushed in the right direction, students will opt for the top 10 or 15 hits as their research strategy. And it’s the students most in need of research training who are the least likely to avail themselves of more sophisticated tools like Google Scholar. Like other major technologies, Google’s search functionality won’t push the human intellect in one predetermined direction. It will reinforce certain dispositions in the end-user: stronger intellects will use Google as a creative tool, while others will let Google do the thinking for them.” – David Ellis, York University, Toronto

It’s not Google’s fault if users create stupid queries.

“To be more precise, unthinking use of the Internet, and in particular untutored use of Google, has the ability to make us stupid, but that is not a foregone conclusion. More and more of us experience attention deficit, like Bruce Friedman in the Nicholas Carr article, but that alone does not stop us making good choices provided that the “factoids” of information are sound that we use to make out decisions. The potential for stupidity comes where we rely on Google (or Yahoo, or Bing, or any engine) to provide relevant information in response to poorly constructed queries, frequently one-word queries, and then base decisions or conclusions on those returned items.” – Peter Griffiths, former Head of Information at the Home Office within the Office of the Chief Information Officer, United Kingdom

“The problem isn’t Google; it’s what Google helps us find. For some, Google will let them find useless content that does not challenge their minds. But for others, Google will lead them to expect answers to questions, to explore the world, to see and think for themselves.” – Esther Dyson , longtime Internet expert and investor

“People are already using Google as an adjunct to their own memory. For example, I have a hunch about something, need facts to support, and Google comes through for me. Sometimes, I see I’m wrong, and I appreciate finding that out before I open my mouth.” – Craig Newmark, founder Craig’s List

“Google is a data access tool. Not all of that data is useful or correct. I suspect the amount of misleading data is increasing faster than the amount of correct data. There should also be a distinction made between data and information. Data is meaningless in the absence of an organizing context. That means that different people looking at the same data are likely to come to different conclusions. There is a big difference with what a world class artist can do with a paint brush as opposed to a monkey. In other words, the value of Google will depend on what the user brings to the game. The value of data is highly dependent on the quality of the question being asked.” – Robert Lunn, consultant, FocalPoint Analytics

The big struggle is over what kind of information Google and other search engines kick back to users. In the age of social media where users can be their own content creators it might get harder and harder to separate high-quality material from junk.

“Access to more information isn’t enough — the information needs to be correct, timely, and presented in a manner that enables the reader to learn from it. The current network is full of inaccurate, misleading, and biased information that often crowds out the valid information. People have not learned that ‘popular’ or ‘available’ information is not necessarily valid.”– Gene Spafford , Purdue University CERIAS, Association for Computing Machinery U.S. Public Policy Council

“If we take ‘Google’ to mean the complex social, economic and cultural phenomenon that is a massively interactive search and retrieval information system used by people and yet also using them to generate its data, I think Google will, at the very least, not make us smarter and probably will make us more stupid in the sense of being reliant on crude, generalised approximations of truth and information finding. Where the questions are easy, Google will therefore help; where the questions are complex, we will flounder.” – Matt Allen, former president of the Association of Internet Researchers and associate professor of internet studies at Curtin University in Australia

“The challenge is in separating that wheat from the chaff, as it always has been with any other source of mass information, which has been the case all the way back to ancient institutions like libraries. Those users (of Google, cable TV, or libraries) who can do so efficiently will beat the odds, becoming ‘smarter’ and making better choices. However, the unfortunately majority will continue to remain, as Carr says, stupid.” – Christopher Saunders, managing editor internetnews.com

“The problem with Google that is lurking just under the clean design home page is the “tragedy of the commons”: the link quality seems to go down every year. The link quality may actually not be going down but the signal to noise is getting worse as commercial schemes lead to more and more junk links.” – Glen Edens, former senior vice president and director at Sun Microsystems Laboratories, chief scientist Hewlett Packard

Literary intelligence is very much under threat.

“If one defines — or partially defines — IQ as literary intelligence, the ability to sit with a piece of textual material and analyze it for complex meaning and retain derived knowledge, then we are indeed in trouble. Literary culture is in trouble…. We are spending less time reading books, but the amount of pure information that we produce as a civilization continues to expand exponentially. That these trends are linked, that the rise of the latter is causing the decline of the former, is not impossible…. One could draw reassurance from today’s vibrant Web culture if the general surfing public, which is becoming more at home in this new medium, displayed a growing propensity for literate, critical thought. But take a careful look at the many blogs, post comments, Facebook pages, and online conversations that characterize today’s Web 2.0 environment…. This type of content generation, this method of ‘writing,’ is not only sub-literate, it may actually undermine the literary impulse…. Hours spent texting and e-mailing, according to this view, do not translate into improved writing or reading skills.” – Patrick Tucker, senior editor, The Futurist magazine

New literacies will be required to function in this world. In fact, the internet might change the very notion of what it means to be smart. Retrieval of good information will be prized. Maybe a race of “extreme Googlers” will come into being.

“The critical uncertainty here is whether people will learn and be taught the essential literacies necessary for thriving in the current infosphere: attention, participation, collaboration, crap detection, and network awareness are the ones I’m concentrating on. I have no reason to believe that people will be any less credulous, gullible, lazy, or prejudiced in ten years, and am not optimistic about the rate of change in our education systems, but it is clear to me that people are not going to be smarter without learning the ropes.” – Howard Rheingold, author of several prominent books on technology, teacher at Stanford University and University of California-Berkeley

“Google makes us simultaneously smarter and stupider. Got a question? With instant access to practically every piece of information ever known to humankind, we take for granted we’re only a quick web search away from the answer. Of course, that doesn’t mean we understand it. In the coming years we will have to continue to teach people to think critically so they can better understand the wealth of information available to them.” — Jeska Dzwigalski , Linden Lab

“We might imagine that in ten years, our definition of intelligence will look very different. By then, we might agree on “smart” as something like a ‘networked’ or ‘distributed’ intelligence where knowledge is our ability to piece together various and disparate bits of information into coherent and novel forms.” – Christine Greenhow, educational researcher, University of Minnesota and Yale Information and Society Project

“Human intellect will shift from the ability to retain knowledge towards the skills to discover the information i.e. a race of extreme Googlers (or whatever discovery tools come next). The world of information technology will be dominated by the algorithm designers and their librarian cohorts. Of course, the information they’re searching has to be right in the first place. And who decides that?” – Sam Michel, founder Chinwag, community for digital media practitioners in the United Kingdom

One new “literacy” that might help is the capacity to build and use social networks to help people solve problems.

“There’s no doubt that the internet is an extension of human intelligence, both individual and collective. But the extent to which it’s able to augment intelligence depends on how much people are able to make it conform to their needs. Being able to look up who starred in the 2nd season of the Tracey Ullman show on Wikipedia is the lowest form of intelligence augmentation; being able to build social networks and interactive software that helps you answer specific questions or enrich your intellectual life is much more powerful. This will matter even more as the internet becomes more pervasive. Already my iPhone functions as the external, silicon lobe of my brain. For it to help me become even smarter, it will need to be even more effective and flexible than it already is. What worries me is that device manufacturers and internet developers are more concerned with lock-in than they are with making people smarter. That means it will be a constant struggle for individuals to reclaim their intelligence from the networks they increasingly depend upon.” – Dylan Tweney, senior editor, Wired magazine

Nothing can be bad that delivers more information to people, more efficiently. It might be that some people lose their way in this world, but overall, societies will be substantially smarter.

“The Internet has facilitated orders of magnitude improvements in access to information. People now answer questions in a few moments that a couple of decades back they would not have bothered to ask, since getting the answer would have been impossibly difficult.” – John Pike, Director, globalsecurity.org

“Google is simply one step, albeit a major one, in the continuing continuum of how technology changes our generation and use of data, information, and knowledge that has been evolving for decades. As the data and information goes digital and new information is created, which is at an ever increasing rate, the resultant ability to evaluate, distill, coordinate, collaborate, problem solve only increases along a similar line. Where it may appear a ‘dumbing down’ has occurred on one hand, it is offset (I believe in multiples) by how we learn in new ways to learn, generate new knowledge, problem solve, and innovate.” — Mario Morino, Chairman, Venture Philanthropy Partners

Google itself and other search technologies will get better over time and that will help solve problems created by too-much-information and too-much-distraction.

“I’m optimistic that Google will get smarter by 2020 or will be replaced by a utility that is far better than Google. That tool will allow queries to trigger chains of high-quality information – much closer to knowledge than flood. Humans who are able to access these chains in high-speed, immersive ways will have more patters available to them that will aid decision-making. All of this optimism will only work out if the battle for the soul of the Internet is won by the right people – the people who believe that open, fast, networks are good for all of us.” – Susan Crawford , former member of President Obama’s National Economic Council, now on the law faculty at the University of Michigan

“If I am using Google to find an answer, it is very likely the answer I find will be on a message board in which other humans are collaboratively debating answers to questions. I will have to choose between the answer I like the best. Or it will force me to do more research to find more information. Google never breeds passivity or stupidity in me: It catalyzes me to explore further. And along the way I bump into more humans, more ideas and more answers.” – Joshua Fouts, Senior Fellow for Digital Media & Public Policy at the Center for the Study of the Presidency

The more we use the internet and search, the more dependent on it we will become.

“As the Internet gets more sophisticated it will enable a greater sense of empowerment among users. We will not be more stupid, but we will probably be more dependent upon it.” – Bernie Hogan, Oxford Internet Institute

Even in little ways, including in dinner table chitchat, Google can make people smarter.

[Family dinner conversations]

‘We know more than ever, and this makes us crazy.’

“The answer is really: both. Google has already made us smarter, able to make faster choices from more information. Children, to say nothing of adults, scientists and professionals in virtually every field, can seek and discover knowledge in ways and with scope and scale that was unfathomable before Google. Google has undoubtedly expanded our access to knowledge that can be experienced on a screen, or even processed through algorithms, or mapped. Yet Google has also made us careless too, or stupid when, for instance, Google driving directions don’t get us to the right place. It ahs confused and overwhelmed us with choices, and with sources that are not easily differentiated or verified. Perhaps it’s even alienated us from the physical world itself – from knowledge and intelligence that comes from seeing, touching, hearing, breathing and tasting life. From looking into someone’s eyes and having them look back into ours. Perhaps it’s made us impatient, or shortened our attention spans, or diminished our ability to understand long thoughts. It’s enlightened anxiety. We know more than ever, and this makes us crazy.” – Andrew Nachison, co-founder, We Media

A final thought: Maybe Google won’t make us more stupid, but it should make us more modest.

“There is and will be lots more to think about, and a lot more are thinking. No, not more stupid. Maybe more humble.” — Sheizaf Rafaeli, Center for the Study of the Information Society, University of Haifa

- Note: Previously, this sentence had incorrectly stated that the article was published in the summer of 2009. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Future of the Internet (Project)

- Online Privacy & Security

- Platforms & Services

- Privacy Rights

- Social Media

- Technology Adoption

72% of U.S. high school teachers say cellphone distraction is a major problem in the classroom

U.s. public, private and charter schools in 5 charts, is college worth it, half of latinas say hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains, a quarter of u.s. teachers say ai tools do more harm than good in k-12 education, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Nicholas Carr's blog

“is google making us stupid”: sources and notes.

Since the publication of my essay Is Google Making Us Stupid? in The Atlantic, I’ve received several requests for pointers to sources and related readings. I’ve tried to round them up below.

The essay builds on my book The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google, particularly the final chapter, “iGod.” The essential theme of both the essay and the book – that our technologies change us, often in ways we can neither anticipate nor control – is one that was frequently, and deeply, discussed during the last century, in books and articles by such thinkers as Lewis Mumford, Eric A. Havelock, J. Z. Young, Marshall McLuhan, and Walter J. Ong.

The screenplay for the film 2001: A Space Odyssey was written by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Clarke’s book 2001 , a lesser work than the film, was based on the screenplay rather than vice versa.

Scott Karp’s blog post about how he’s lost his capacity to read books can be found here , and Bruce Friedman’s post can be found here . Both Karp and Friedman believe that what they’ve gained from the Internet outweighs what they’ve lost. An overview of the University of College London study of the behavior of online researchers, “Information Behaviour of

the Researcher of the Future,” is here . Maryanne Wolf’s fascinating Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain was published last year by Harpercollins.

I found the story of Friedrich Nietzsche’s typewriter in J. C. Nyíri’s essay Thinking with a Word Processor as well as Friedrich A. Kittler’s winningly idiosyncratic Gramophone, Film, Typewriter and Darren Wershler-Henry’s history of the typewriter, The Iron Whim .

Lewis Mumford discusses the impact of the mechanical clock in his 1934 Technics and Civilization . See also Mumford’s later two-volume study The Myth of the Machine . Joseph Weizenbaum’s Computer Power and Human Reason remains one of the most thoughtful books written about the human implications of computing. Weizenbaum died earlier this year, and I wrote a brief appreciation of him here .

Alan Turing’s 1936 paper on the universal computer was titled On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem . Tom Bodkin’s explanation of the New York Times ‘s design changes came in this Slate interview with Jack Shafer.

For Frederick Winslow Taylor’s story, I drew on Robert Kanigel’s biography The One Best Way and Taylor’s own The Principles of Scientific Management .

Eric Schmidt made his comments about Google’s Taylorist goals during the company’s 2006 press day . The Harvard Business Review article on Google, “Reverse Engineering Google’s Innovation Machine,” appeared in the April 2008 issue. Google describes its “mission” here and here . A much lengthier recital of Sergey Brin’s and Larry Page’s comments on Google’s search engine as a form of artificial intelligence, along with sources, can be found at the start of the “iGod” chapter in The Big Switch . Schmidt made his comment about “using technology to solve problems that have never been solved before” at the company’s 2006 analyst day .

I used Neil Postman’s translation of the excerpt from Plato’s Phaedrus, which can be found at the start of Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology . Walter J. Ong quotes Hieronimo Squarciafico in Orality and Literacy . Clay Shirky’s observation about the printing press was made here .

Richard Foreman’s “pancake people” essay was originally distributed to members of the audience for Foreman’s play The Gods Are Pounding My Head . It was reprinted in Edge. I first noted the essay in my 2005 blog post Beyond Google and Evil .

Promulgate:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

10 thoughts on “ “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”: sources and notes ”

I mention your article and link this very useful blog posting in my latest Berkshire Artsblog entry, where I briefly mention a couple of counter-examples from personal experience. If you make an effort to control the effect of online reading, you can still read books, I think.

The Atlantic article was great – thanks. Have you noticed the connection with an earlier edition of the Atlantic?

Oliver Wendell Holmes Snr. famously observed in an early edition of the Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1858, “Every now and then a man’s mind is stretched by a new idea or sensation, and never shrinks back to its former dimensions.” This was published almost exactly 150 years ago, as part of a series of monographs subsequently compiled into a book titled ‘The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table’.

In 1858 philosophers enthused at the way a new idea could expand one’s intellectual horizons. By 2008 there are so many new ideas, so easily found, that our minds are overstretched and overwhelmed by them!

I like your comments about shallow/pancake brains. It causes one to ponder how Holmes would regard the manner in which our minds are stretched by the internet? Deeply or shallowly? One is reminded of the old jest about the difference between people from Melbourne and Sydney, the former being shallowly deep and the later deeply shallow. Are we clogging our minds with shallow ephemera and ‘social networking’ while we upload our deep knowledge to the internet … and with it our practical, dirt under the fingernails, wisdom? Can anyone now become an instant expert on any topic in the manner of Trinity downloading the ability to fly a helicopter in the movie The Matrix? University lecturers frequently comment with dismay about the digital generation’s scant disregard for deep learning. Why bother memorizing when you can just Google knowledge when you need it? Are we now happy with shallow, thin, brains knowing that we can go deep on demand by plugging ourselves into the cloud?

Perhaps ‘diving deep’ into the colder waters of offline knowledge, savored on paper and discussed with face-to-face people, is good for the brain in the same way that good food and regular exercise are good for our bodies?

If Trinity’s ability to fly that helicopter is dependent on her connection to The Matrix what happens when she needs to operate in offline mode?

How about Vannevar Bush As We May Think ? Although crude and anachronistic, the thoughts of the guy who actually invented the idea of a search engine are important as well. At least in terms of how the technology could provide an adjunct to human reasoning rather than as a replacement for it. Eric Schmidt’s idea that Google as a form of AI is a “little bit out there” – too much Starbuck’s, EC?

Did you ever consider the potential effects of screens and their light on our behaviour? Maybe the observed psychological effects are due to the fact that we stare more or less directly at a source of light all the time during the reading process from a screen, which may lead to some unphysiological form of arousal. I observe personally that in evenings I can remain awake behind a laptop screen for hours without feeling tired, but when I switch the screen off and start to read from paper, it takes no more than 5 to 10 minutes and I have to fight against sleep. I attribute this much more to effects of the hardware than to any form of the content.

I just read The Big Switch, and really enjoyed it. Besides all else, it was delightfully well written. I note that you discuss the themes of “Is Google making us stupid?” at some length near the end of the book. However, unless I’ve missed something, none of the commenters in this debate have pointed this out. Maybe they didn’t have enough attention span to get to those last pages… ;-)

Perhaps the Internet and Google are also making us international conformists. As more of us read the same ideas and are less exposed to fringe-thinking (that’s after all what Google [and popular/mass Media] does) we will tend to adopt more popular ideas as our own. Individualism is what has led to the great persons of history and their ideas which themselves have had the most impact on human history. Perhaps, on the positive side, it will lead to greater peace – wars are frequently about clashing ideals and purposes after all. I would not ,however, vote for peace if it meant trading humanity’s progress in the bargain.

When the Atlantic runs a full page ad in Business Week (Nov 03 Issue) with only the words ‘Is google making us stupid?”

You can safely say you hit a nerve

Hello Nick,

My name is Jessica, and I am a senior at Milken Community High School. My history class, America 3.0 (a study of the last 40 years of American history and how it will affect the future of our country) recently read your book, The Big Switch, and I particularly found your iGod chapter to be riveting, as well as frightening when discussing the looming future of artificial intelligence integrated into our brains.

When I discussed this topic with my friends, they seemed very aggressive and quick to put down my feelings of ambivalence towards this future technology. One friend in particular strongly supports the utilization of this technology, claiming that it will improve our quality of life ten fold due to the instant gratification that the brain chip will give us. Mass amounts of information readily available at our fingertips will allow for learning to elevate to a new level.

My issue with this technology is the potential it provides for mind infiltration. It is no secret, there are people all around the world that hack computers, and steal extremely important information. Take China for example, with online communities designated to attack the United States government websites through Denial of Service attacks. They’ve stolen terabytes of information on the F-25 joint strike fighter, which America and other NATO supporting companies have supported billions into. We still don’t know what they did with the information, except that they have it and that it can be used against us.

Now, with the issue of hackers getting into computer databases in our government, an institution that is supposed to be the safest in the country, how are we supposed to allow computer chips to be installed into our brains? I truly believe that it doesn’t matter how advanced technology gets, there will always be a way to break it down and I definitely don’t feel comfortable with the idea of someone getting into my mind. When the information being stolen is external, tangible, outside of my body, it is explainable. It can be taken by anyone. But, when something is in the safety of my mind, and is open to be absconded with, that is where the true fear begins to erupt.

This type of hacking opens to door to all different kinds of mind based warfare, and Orwellian opportunities. Who is to say that America won’t enter the age of 1984, and use computer databases in our minds just as the Thought Police did? We are entering uneasy times in our country, and already you can slowly see civil liberties being taken away. Say the word ‘bomb’ in an airport, and you will see what our country has come to. No longer will you have to say the word ‘bomb’, all you will have to do is think it. People will be wrongly attacked and questioned for harmless thoughts, and involuntary daydreams that were not floating through the id with violent intentions.

You speak about the technology, “…offer[ing] the ‘potential for outside control of human behavior through digital media.’ We will become programmable, too” (pg 217). The age in which humans will no longer be able to be differentiated on the basis of intelligence, where we will be able to technologically advance our brains without the labor of learning, will be a very dark age. No longer will education be respected, or necessary for that matter. Why even live if every single documented human experience will be readily available in our minds? There will no longer be surprise…accomplishment…competition…we will turn into a conformist country, ruled by robots.

We recently read your article “Is Google Making Us Stupid” in my College English class. I am a mom of two and the artical actually really made me think about why my girls don’t like to sit down and read a book. The article made me realize that their brains were never trained to be that quiet and that still. We are now working with them to train their brains to slow down so they can sit and read for long periods of time. I no longer get severely frustrated with them because I understand them a little better. Thank you.

Thanks for this list of sources. Even if you read a book on a kindle it’s not the same as reading a real book – it’s ontologically different!

See Ong’s lectures:

http://libraries.slu.edu/special/digital/ong/audio.php

and Michael Heim’s argument:

http://www.mheim.com/files/21c-heim.pdf

Comments are closed.

Is Google Making Us Stupid? Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Works cited.

The world is growing too fast in terms of technology since the emergence of the internet. The internet remains important in bringing about technological change, thus influencing changes in human behavior.

In the view of many, the internet has greatly contributed to the growth of knowledge and research. However, although the internet has greatly contributed to the growth of knowledge, it has been opposed by a section of people arguing that it has numerous negative implications to innovation and creativity.

In his July Article, Nicholas Carr wrote “Is Google making Us Stupid.” Google is a widely used search engine across the internet. It is fundamental to note that although technology is essential in the context of the society, it comes with fear of deteriorating human development in some way. In this paper, I seek to argue in favor of the statement that Google is not making us stupid.

Developments in technology and growth of knowledge would need necessary tools for their success. Therefore, knowledge requires tools of technology to ensure easy access, growth and distribution of information.

To argue that the minds are being made stupid by a tool that enables access to information with a view to advance the same body of knowledge is unsustainable. We note that research is a continuous exercise that needs scholars and academicians to link various pieces of knowledge with an aim of making it better.

Therefore, technological tools that promote this process are critically important (Leven 112). It is true according to DarkHawke that there shall constantly be fear of the advancements in technology by the masses (Schlesinger 68).

Science has done far-reaching research and predictions on what can go wrong with the advancements in technology. This fear has been in existence among people since their childhood. In many occasions, parents have exhibited their fear of technology by dictating and perhaps prescribing what their kids should watch, listen to, and play with.

Indeed those who argue against the extent to which Goggle has contributed to the growth of knowledge do so in the spirit that it has acted to obliterate the public discourses. They argue that no individual can now think about an answer when he or she can just “Google” the outcome (Schlesinger 68).

The mere fact that people can access information at a touch of a button does not amount to idleness of the mind, but rather, the idea of using the search engine is self-fulfilling.

Fundamentally, no stupid mind can navigate around the internet trying to seek knowledge and expand neither his nor her scope of understanding. It is perhaps important that I table the essence of for which the search engine was established to serve.

The need for faster access to information has been there since the historical moments. It may be necessary to state that Google is not solely responsible for making the minds stupid, but if in case stupidity exists, individuals are virtually responsible for it.

Research calls for moral and professional responsibility. Indeed no individual can now take another person’s piece of work and present for marking. For many decades, people have delivered their research materials at various level, whose ownership has been suspect.

These presentations went unnoticed since no tool was in place to ensure originality and authenticity of these materials (Leven 11).

Today, Google take up a position of faster access and navigation through any form of data and information previously completed by various researchers. It is worth not6ing that plagiarism is an academic and professional offence whose image does not does not occupy space in the realms of research.

Nothing can be wrong if someone wants to learn about a given phenomenon or subject. Let us imagine the trouble that one would go through searching into the entire book looking for a specific piece of information. Firstly, the essence of time serves as the best rubric for continuous use of search engines like Google and yahoo.

The essence of the search tools in facilitation the access to information serves far-reaching importance in cushioning academicians against the implications of time3 wastage. Traditionally, the process of looking for information, processing and presenting was too long.

This led to delayed spread of knowledge to the intended destinations and people. Because the spread of information has contributed to the emergence of numerous innovations through creative imaginations, it follows that technological tools should be made available, accessible and efficient in achieving this noble course.

Google represents the common struggle that people have engaged in though it achieves this objective though in a more convenient manner (Sherman 110). It still resembles that act of flipping through voluminous pages of old books to look for a specific index, words, or phrase.

This engine should be viewed as a facilitator of finding information within short span of time without much struggle. Additionally, traditional mode of looking for information has been limited in scope and approach. It is critical to examine the extent to which this search engine has demanded of us to make and unite various pieces of information to emerge with a unique piece.

Today, people can now access various sources, books, articles, and journals in order to come up with a succinct piece that reflects the demands of dynamic world. Initially, we have been restricted in the manner and scope of knowledge in which our home libraries have been the order of the day in establishing what we consume.

Growth and development of academicians cannot depend upon physical information whose nature of study is tiring and exhaustive.

Let us take the introduction of scientific calculators, which automatically gives answers to mathematical problems. Before this technology came in, complex mathematical problems could take numerous days or hours before arriving at an answer by manually performing the calculations. Now, everyone began using these tools in solving their problems in mathematics and other scenarios.

However, even though this is the order of the day, does this mean that we are eventually being made stupid, or is it just a sheer adaptation to the changing world and times? Should humanity revert to the olden days and mode of doing things in order to avoid being stupid?

Can it be fundamentally correct to propose that we have been made stupid by cars by letting go on walking? Should people stop listening and using digital music, videos and films and revert to analog forms of entertainment without appreciating the new ones?

Perhaps these questions should be essential in demonstrating the significant role played by Google in illuminating the minds of people, rather than making them stupid (Jones 112). Anyone who has stopped thinking in anew style and manner of doing things merits falling in the classification of stupid beings.

Those who have perhaps sought to revert to the traditional ways of searching for information by shutting the computers have convinced themselves that print media is virtually different from electronic media. To depart from using high-tech tools that gives you what you need in a real-time mode serves to demonstrate some sense of “stupidity of the mind.”

In conclusion, the creation of Google and other search engines has greatly facilitated access to crucial information in a timely manner as compared to the traditional modes.

Although it may be true that individuals have been made inactive in thinking because of the readily available information, this availability has enabled a successful growth of knowledge. For example, Google has served critical roles in making available relevant information in real time (Sherman 110).

Therefore, it is not exclusively true that Google serves as the means to achieving the necessary ends, but not an end in itself.

The idea that Google widens the scope of our minds allows us to imagine of the troubles suffered by our ancestors during the historical moments (Books LLC, General Books LLC 114). To create and develop a sense of imagination about a subject that makes you stupid reveals just how the problem resides in you.

To blame computer engineers and developers of programs for one’s growing stupidity demonstrates that perhaps one has decided to stop engaging in critical thinking and reverted to blame-games. Finally, the fundamental roles played by the search engines such as Google remain important in ensuring ease of acquisition of knowledge.

Books LLC, General Books LLC. 2008 Works: Is Google Making Us stupid? I Love the World, Barrack Obama Hope poster, Texas Medal of Honor Memorial, Playing Gods . New York: General Books, 2010. Print.

Jones, Kristopher. Search Engine Optimization: Your vision blue print for effective internet Marketing . New York: John Willey and Sons, 2010.

Leven, Mark. An Introduction to Search engines and web navigation. New York: John Willey and Sons, 2010. Print. 111.

Schlesinger, Andrea. The Death of “Why?” The Decline of Questioning and the future of Demogracy . Berret Koehler Publishers, 2009. Print.

Sherman, Chris. Google Power: Unleash the full potential of Google . New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005. Print.

- The Implications and the Effects of Confusion

- Comparison and Contrast Assignment on “Paradoxical Effects of Presentation Modality on False Memory,” Article and “Individual Differences in Learning and Remembering Music.”

- "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" Article by Carr: Rhetorical Analysis

- Flight into Canada by Ishmael Reed

- Relationships in the “Crazy, Stupid, Love” Movie

- Intelligence in Two Psychological Journals Written by Thorndike and Hagopian

- Learning and Cognition Project

- Applying Problem Solving

- Attention Biases in Anxiety

- Lifespan Development and Personality Paper

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, March 26). Is Google Making Us Stupid? https://ivypanda.com/essays/is-google-making-us-stupid/

"Is Google Making Us Stupid?" IvyPanda , 26 Mar. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/is-google-making-us-stupid/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Is Google Making Us Stupid'. 26 March.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" March 26, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/is-google-making-us-stupid/.

1. IvyPanda . "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" March 26, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/is-google-making-us-stupid/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" March 26, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/is-google-making-us-stupid/.

Get Smarter

Pandemics. Global warming. Food shortages. No more fossil fuels. What are humans to do? The same thing the species has done before: evolve to meet the challenge. But this time we don’t have to rely on natural evolution to make us smart enough to survive. We can do it ourselves, right now, by harnessing technology and pharmacology to boost our intelligence. Is Google actually making us smarter?

Image: Anastasia Vasilakis

S eventy-four thousand years ago, humanity nearly went extinct. A super-volcano at what’s now Lake Toba, in Sumatra, erupted with a strength more than a thousand times that of Mount St. Helens in 1980. Some 800 cubic kilometers of ash filled the skies of the Northern Hemisphere, lowering global temperatures and pushing a climate already on the verge of an ice age over the edge. Some scientists speculate that as the Earth went into a deep freeze, the population of Homo sapiens may have dropped to as low as a few thousand families.

The Mount Toba incident, although unprecedented in magnitude, was part of a broad pattern. For a period of 2 million years, ending with the last ice age around 10,000 B.C. , the Earth experienced a series of convulsive glacial events. This rapid-fire climate change meant that humans couldn’t rely on consistent patterns to know which animals to hunt, which plants to gather, or even which predators might be waiting around the corner.

How did we cope? By getting smarter. The neurophysiologist William Calvin argues persuasively that modern human cognition—including sophisticated language and the capacity to plan ahead—evolved in response to the demands of this long age of turbulence. According to Calvin, the reason we survived is that our brains changed to meet the challenge: we transformed the ability to target a moving animal with a thrown rock into a capability for foresight and long-term planning. In the process, we may have developed syntax and formal structure from our simple language.

Our present century may not be quite as perilous for the human race as an ice age in the aftermath of a super-volcano eruption, but the next few decades will pose enormous hurdles that go beyond the climate crisis. The end of the fossil-fuel era, the fragility of the global food web, growing population density, and the spread of pandemics, as well as the emergence of radically transformative bio- and nanotechnologies—each of these threatens us with broad disruption or even devastation. And as good as our brains have become at planning ahead, we’re still biased toward looking for near-term, simple threats. Subtle, long-term risks, particularly those involving complex, global processes, remain devilishly hard for us to manage.

But here’s an optimistic scenario for you: if the next several decades are as bad as some of us fear they could be, we can respond, and survive, the way our species has done time and again: by getting smarter. But this time, we don’t have to rely solely on natural evolutionary processes to boost our intelligence. We can do it ourselves.

Most people don’t realize that this process is already under way. In fact, it’s happening all around us, across the full spectrum of how we understand intelligence. It’s visible in the hive mind of the Internet, in the powerful tools for simulation and visualization that are jump-starting new scientific disciplines, and in the development of drugs that some people (myself included) have discovered let them study harder, focus better, and stay awake longer with full clarity. So far, these augmentations have largely been outside of our bodies, but they’re very much part of who we are today: they’re physically separate from us, but we and they are becoming cognitively inseparable. And advances over the next few decades, driven by breakthroughs in genetic engineering and artificial intelligence, will make today’s technologies seem primitive. The nascent jargon of the field describes this as “ intelligence augmentation.” I prefer to think of it as “You+.”

Scientists refer to the 12,000 years or so since the last ice age as the Holocene epoch. It encompasses the rise of human civilization and our co-evolution with tools and technologies that allow us to grapple with our physical environment. But if intelligence augmentation has the kind of impact I expect, we may soon have to start thinking of ourselves as living in an entirely new era. The focus of our technological evolution would be less on how we manage and adapt to our physical world, and more on how we manage and adapt to the immense amount of knowledge we’ve created. We can call it the Nöocene epoch, from Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s concept of the Nöosphere, a collective consciousness created by the deepening interaction of human minds. As that epoch draws closer, the world is becoming a very different place.

Of course, we’ve been augmenting our ability to think for millennia. When we developed written language, we significantly increased our functional memory and our ability to share insights and knowledge across time and space. The same thing happened with the invention of the printing press, the telegraph, and the radio. The rise of urbanization allowed a fraction of the populace to focus on more-cerebral tasks—a fraction that grew inexorably as more-complex economic and social practices demanded more knowledge work, and industrial technology reduced the demand for manual labor. And caffeine and nicotine, of course, are both classic cognitive-enhancement drugs, primitive though they may be.

With every technological step forward, though, has come anxiety about the possibility that technology harms our natural ability to think. These anxieties were given eloquent expression in these pages by Nicholas Carr, whose essay “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” (July/August 2008 Atlantic ) argued that the information-dense, hyperlink-rich, spastically churning Internet medium is effectively rewiring our brains, making it harder for us to engage in deep, relaxed contemplation.

Carr’s fears about the impact of wall-to-wall connectivity on the human intellect echo cyber-theorist Linda Stone’s description of “continuous partial attention,” the modern phenomenon of having multiple activities and connections under way simultaneously. We’re becoming so accustomed to interruption that we’re starting to find focusing difficult, even when we’ve achieved a bit of quiet. It’s an induced form of ADD—a “continuous partial attention-deficit disorder,” if you will.

There’s also just more information out there—because unlike with previous information media, with the Internet, creating material is nearly as easy as consuming it. And it’s easy to mistake more voices for more noise. In reality, though, the proliferation of diverse voices may actually improve our overall ability to think. In Everything Bad Is Good for You , Steven Johnson argues that the increasing complexity and range of media we engage with have, over the past century, made us smarter, rather than dumber, by providing a form of cognitive calisthenics. Even pulp-television shows and video games have become extraordinarily dense with detail, filled with subtle references to broader subjects, and more open to interactive engagement. They reward the capacity to make connections and to see patterns—precisely the kinds of skills we need for managing an information glut.

Scientists describe these skills as our “fluid intelligence”—the ability to find meaning in confusion and to solve new problems, independent of acquired knowledge. Fluid intelligence doesn’t look much like the capacity to memorize and recite facts, the skills that people have traditionally associated with brainpower. But building it up may improve the capacity to think deeply that Carr and others fear we’re losing for good. And we shouldn’t let the stresses associated with a transition to a new era blind us to that era’s astonishing potential. We swim in an ocean of data, accessible from nearly anywhere, generated by billions of devices. We’re only beginning to explore what we can do with this knowledge-at-a-touch.

Moreover, the technology-induced ADD that’s associated with this new world may be a short-term problem. The trouble isn’t that we have too much information at our fingertips, but that our tools for managing it are still in their infancy. Worries about “information overload” predate the rise of the Web (Alvin Toffler coined the phrase in 1970), and many of the technologies that Carr worries about were developed precisely to help us get some control over a flood of data and ideas. Google isn’t the problem; it’s the beginning of a solution.

In any case, there’s no going back. The information sea isn’t going to dry up, and relying on cognitive habits evolved and perfected in an era of limited information flow—and limited information access—is futile. Strengthening our fluid intelligence is the only viable approach to navigating the age of constant connectivity.

W hen people hear the phrase intelligence augmentation , they tend to envision people with computer chips plugged into their brains, or a genetically engineered race of post-human super-geniuses. Neither of these visions is likely to be realized, for reasons familiar to any Best Buy shopper. In a world of ongoing technological acceleration, today’s cutting-edge brain implant would be tomorrow’s obsolete junk—and good luck if the protocols change or you’re on the wrong side of a “format war” (anyone want a Betamax implant?). And then there’s the question of stability: Would you want a chip in your head made by the same folks that made your cell phone, or your PC?

Likewise, the safe modification of human genetics is still years away. And even after genetic modification of adult neurobiology becomes possible, the science will remain in flux; our understanding of how augmentation works, and what kinds of genetic modifications are possible, would still change rapidly. As with digital implants, the brain modification you might undergo one week could become obsolete the next. Who would want a 2025-vintage brain when you’re competing against hotshots with Model 2026?

Yet in one sense, the age of the cyborg and the super-genius has already arrived. It just involves external information and communication devices instead of implants and genetic modification. The bioethicist James Hughes of Trinity College refers to all of this as “exocortical technology,” but you can just think of it as “stuff you already own.” Increasingly, we buttress our cognitive functions with our computing systems, no matter that the connections are mediated by simple typing and pointing. These tools enable our brains to do things that would once have been almost unimaginable:

• powerful simulations and massive data sets allow physicists to visualize, understand, and debate models of an 11‑dimension universe;

• real-time data from satellites, global environmental databases, and high-resolution models allow geophysicists to recognize the subtle signs of long-term changes to the planet;

• cross-connected scheduling systems allow anyone to assemble, with a few clicks, a complex, multimodal travel itinerary that would have taken a human travel agent days to create.

If that last example sounds prosaic, it simply reflects how embedded these kinds of augmentation have become. Not much more than a decade ago, such a tool was outrageously impressive—and it destroyed the travel-agent industry.

That industry won’t be the last one to go. Any occupation requiring pattern-matching and the ability to find obscure connections will quickly morph from the domain of experts to that of ordinary people whose intelligence has been augmented by cheap digital tools. Humans won’t be taken out of the loop—in fact, many, many more humans will have the capacity to do something that was once limited to a hermetic priesthood. Intelligence augmentation decreases the need for specialization and increases participatory complexity.

As the digital systems we rely upon become faster, more sophisticated, and (with the usual hiccups) more capable, we’re becoming more sophisticated and capable too. It’s a form of co-evolution: we learn to adapt our thinking and expectations to these digital systems, even as the system designs become more complex and powerful to meet more of our needs—and eventually come to adapt to us .

Consider the Twitter phenomenon, which went from nearly invisible to nearly ubiquitous (at least among the online crowd) in early 2007. During busy periods, the user can easily be overwhelmed by the volume of incoming messages, most of which are of only passing interest. But there is a tiny minority of truly valuable posts. (Sometimes they have extreme value, as they did during the October 2007 wildfires in California and the November 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai.) At present, however, finding the most-useful bits requires wading through messages like “My kitty sneezed!” and “I hate this taco!”

But imagine if social tools like Twitter had a way to learn what kinds of messages you pay attention to, and which ones you discard. Over time, the messages that you don’t really care about might start to fade in the display, while the ones that you do want to see could get brighter. Such attention filters—or focus assistants—are likely to become important parts of how we handle our daily lives. We’ll move from a world of “continuous partial attention” to one we might call “continuous augmented awareness.”

As processor power increases, tools like Twitter may be able to draw on the complex simulations and massive data sets that have unleashed a revolution in science. They could become individualized systems that augment our capacity for planning and foresight, letting us play “what-if” with our life choices: where to live, what to study, maybe even where to go for dinner. Initially crude and clumsy, such a system would get better with more data and more experience; just as important, we’d get better at asking questions. These systems, perhaps linked to the cameras and microphones in our mobile devices, would eventually be able to pay attention to what we’re doing, and to our habits and language quirks, and learn to interpret our sometimes ambiguous desires. With enough time and complexity, they would be able to make useful suggestions without explicit prompting.

And such systems won’t be working for us alone. Intelligence has a strong social component; for example, we already provide crude cooperative information-filtering for each other. In time, our interactions through the use of such intimate technologies could dovetail with our use of collaborative knowledge systems (such as Wikipedia), to help us not just to build better data sets, but to filter them with greater precision. As our capacity to provide that filter gets faster and richer, it increasingly becomes something akin to collaborative intuition—in which everyone is effectively augmenting everyone else.

In pharmacology, too , the future is already here. One of the most prominent examples is a drug called modafinil. Developed in the 1970s, modafinil—sold in the U.S. under the brand name Provigil—appeared on the cultural radar in the late 1990s, when the American military began to test it for long-haul pilots. Extended use of modafinil can keep a person awake and alert for well over 32 hours on end, with only a full night’s sleep required to get back to a normal schedule.

While it is FDA-approved only for a few sleep disorders, like narcolepsy and sleep apnea, doctors increasingly prescribe it to those suffering from depression, to “shift workers” fighting fatigue, and to frequent business travelers dealing with time-zone shifts. I’m part of the latter group: like more and more professionals, I have a prescription for modafinil in order to help me overcome jet lag when I travel internationally. When I started taking the drug, I expected it to keep me awake; I didn’t expect it to make me feel smarter, but that’s exactly what happened. The change was subtle but clear, once I recognized it: within an hour of taking a standard 200-mg tablet, I was much more alert, and thinking with considerably more clarity and focus than usual. This isn’t just a subjective conclusion. A University of Cambridge study, published in 2003, concluded that modafinil confers a measurable cognitive-enhancement effect across a variety of mental tasks, including pattern recognition and spatial planning, and sharpens focus and alertness.

I’m not the only one who has taken advantage of this effect. The Silicon Valley insider webzine Tech Crunch reported in July 2008 that some entrepreneurs now see modafinil as an important competitive tool. The tone of the piece was judgmental, but the implication was clear: everybody’s doing it, and if you’re not, you’re probably falling behind.

This is one way a world of intelligence augmentation emerges. Little by little, people who don’t know about drugs like modafinil or don’t want to use them will face stiffer competition from the people who do. From the perspective of a culture immersed in athletic doping wars, the use of such drugs may seem like cheating. From the perspective of those who find that they’re much more productive using this form of enhancement, it’s no more cheating than getting a faster computer or a better education.

Modafinil isn’t the only example; on college campuses, the use of ADD drugs (such as Ritalin and Adderall) as study aids has become almost ubiquitous. But these enhancements are primitive. As the science improves, we could see other kinds of cognitive-modification drugs that boost recall, brain plasticity, even empathy and emotional intelligence. They would start as therapeutic treatments, but end up being used to make us “better than normal.” Eventually, some of these may become over-the-counter products at your local pharmacy, or in the juice and snack aisles at the supermarket. Spam e-mail would be full of offers to make your brain bigger, and your idea production more powerful.

Such a future would bear little resemblance to Brave New World or similar narcomantic nightmares; we may fear the idea of a population kept doped and placated, but we’re more likely to see a populace stuck in overdrive, searching out the last bits of competitive advantage, business insight, and radical innovation. No small amount of that innovation would be directed toward inventing the next, more powerful cognitive-enhancement technology.

This would be a different kind of nightmare, perhaps, and cause waves of moral panic and legislative restriction. Safety would be a huge issue. But as we’ve found with athletic doping, if there’s a technique for beating out rivals (no matter how risky), shutting it down is nearly impossible. This would be yet another pharmacological arms race—and in this case, the competitors on one side would just keep getting smarter.

The most radical form of superhuman intelligence, of course, wouldn’t be a mind augmented by drugs or exocortical technology; it would be a mind that isn’t human at all. Here we move from the realm of extrapolation to the realm of speculation, since solid predictions about artificial intelligence are notoriously hard: our understanding of how the brain creates the mind remains far from good enough to tell us how to construct a mind in a machine.

But while the concept remains controversial, I see no good argument for why a mind running on a machine platform instead of a biological platform will forever be impossible; whether one might appear in five years or 50 or 500, however, is uncertain. I lean toward 50, myself. That’s enough time to develop computing hardware able to run a high-speed neural network as sophisticated as that of a human brain, and enough time for the kids who will have grown up surrounded by virtual-world software and household robots—that is, the people who see this stuff not as “Technology,” but as everyday tools—to come to dominate the field.

Many proponents of developing an artificial mind are sure that such a breakthrough will be the biggest change in human history. They believe that a machine mind would soon modify itself to get smarter—and with its new intelligence, then figure out how to make itself smarter still. They refer to this intelligence explosion as “the Singularity,” a term applied by the computer scientist and science-fiction author Vernor Vinge. “Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence,” Vinge wrote in 1993 . “Shortly after, the human era will be ended.” The Singularity concept is a secular echo of Teilhard de Chardin’s “Omega Point,” the culmination of the Nöosphere at the end of history. Many believers in Singularity—which one wag has dubbed “the Rapture for nerds”—think that building the first real AI will be the last thing humans do. Some imagine this moment with terror, others with a bit of glee.

My own suspicion is that a stand-alone artificial mind will be more a tool of narrow utility than something especially apocalyptic. I don’t think the theory of an explosively self-improving AI is convincing—it’s based on too many assumptions about behavior and the nature of the mind. Moreover, AI researchers, after years of talking about this prospect, are already ultra-conscious of the risk of runaway systems.

More important, though, is that the same advances in processor and process that would produce a machine mind would also increase the power of our own cognitive-enhancement technologies. As intelligence augmentation allows us to make ourselves smarter, and then smarter still, AI may turn out to be just a sideshow: we could always be a step ahead.

S o what’s life like in a world of brain doping, intuition networks, and the occasional artificial mind?

Not from our present perspective, of course. For us, now, looking a generation ahead might seem surreal and dizzying. But remember: people living in, say, 2030 will have lived every moment from now until then—we won’t jump into the future. For someone going from 2009 to 2030 day by day, most of these changes wouldn’t be jarring; instead, they’d be incremental, almost overdetermined, and the occasional surprises would quickly blend into the flow of inevitability.

By 2030, then, we’ll likely have grown accustomed to (and perhaps even complacent about) a world where sophisticated foresight, detailed analysis and insight, and augmented awareness are commonplace. We’ll have developed a better capacity to manage both partial attention and laser-like focus, and be able to slip between the two with ease—perhaps by popping the right pill, or eating the right snack. Sometimes, our augmentation assistants will handle basic interactions on our behalf; that’s okay, though, because we’ll increasingly see those assistants as extensions of ourselves.