Replication Crisis

The importance of research to the practice of counseling, why is research literacy important for mental health counseling.

Posted July 30, 2024 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- The replication crisis challenges reliability—many landmark studies fail to replicate.

- Publication bias distorts findings—positive results are more likely to be published than null ones.

- Careerism impacts quality—the pressure to publish frequently can prioritize quantity over quality.

In the field of social science, particularly within psychology and counseling, several critical issues have emerged that undermine the scientific rigor of research and practice. One of the most significant challenges is the replication crisis , where many studies, including landmark research, fail to reproduce consistent results when tested in subsequent experiments. And we're not talking about little-known, oddball studies. This problem covers the whole gamut of social science research, from the seminal studies that change the field, to lesser-known research. This crisis casts doubt on the reliability of established findings and calls into question the foundations upon which many clinical practices are built.

Another pervasive issue is publication bias , where studies with significant or positive results are more likely to be published than those with null or negative findings. This skews the body of available literature, leading to an overestimation of the effectiveness of certain interventions and underrepresentation of alternative or null outcomes. Closely related is the phenomenon of idea laundering , where weak or untested theories are presented as established facts through a cycle of citations and publications, further muddying the waters of scientific clarity.

Careerism or "publish or perish" also poses a significant obstacle, as the pressure to publish frequently and in high-impact journals can lead researchers to prioritize quantity over quality. This environment can foster a focus on novel, eye-catching results rather than thorough, rigorous investigations. Moreover, inadequate graduate training in research methodology and critical thinking exacerbates these issues, leaving emerging counselors ill-prepared to both conduct and critically assess research.

These challenges collectively diminish the quality and credibility of research in social science, which is particularly concerning given the direct impact these studies have on clinical practice. For counselors, a deep understanding of research methods and critical evaluation is essential. It not only equips them to produce meaningful, replicable studies but also empowers them to discern the reliability of existing research, ensuring they base their clinical decisions on solid evidence. However, if counselors in training are not aware of the importance of research, how to conduct research, how to read research, how to integrate the findings of research, AND how to digest research critically given the problems present in research mentioned above, then it will directly affect clinical work, client outcomes and welfare. This is simply not okay since counselors have an ethical duty to provide best practices and safeguard client welfare. But, if you need some convincing, below are some of the reasons I see literacy in research as essential for competent clinical practice.

Research Guides Practice and Limits of Intuition

As clinicians, we often rely on our training, experience, and intuition to make decisions. However, it's essential to recognize that our perceptions are inherently limited and can be biased. Human reasoning, while valuable, is not infallible and can lead us astray. For instance, confirmation bias , the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms our preconceptions, can significantly impact clinical judgments. Therefore, it's crucial to complement our intuition with empirical evidence from social science research. This reliance on research helps to ground our decisions in verified data, ensuring that our interventions are based on more than just subjective judgment.

The Counterintuitive Nature of Research

One of the most valuable aspects of research is its ability to challenge our assumptions. What may seem obvious or intuitive to a seasoned counselor might not hold true for every client. For example, while it may seem intuitive that talking about suicidal thoughts could increase the likelihood of a client acting on them, research indicates that discussing these thoughts in a supportive environment can actually reduce the risk. This highlights the importance of adhering to evidence-based practices, which often provide insights that run counter to common beliefs or intuitive thinking.

Universals and Particulars in Counseling

In the realm of clinical practice, it is crucial to distinguish between universal principles and individual variations. Research can provide us with general trends and effective interventions for broad populations, but every client is unique. What works broadly might not be effective for a specific individual due to various factors such as cultural background, personal history, and psychological makeup. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is widely recognized as an effective treatment for depression , but its applicability may vary based on a client's readiness, cultural context, and specific needs. Thus, while research provides a foundation, clinicians must remain flexible and responsive to the particulars of each client's situation.

Harm Prevention and Ethical Responsibility

Ethical practice in counseling involves a commitment to "do no harm." This principle necessitates that we have a reasonable expectation of the outcomes of our interventions before implementing them. Without a solid research foundation, we risk applying treatments that may be ineffective or even harmful. For example, some outdated or unsupported therapeutic practices, such as "conversion therapy" for sexual orientation , have been shown to cause significant harm. Therefore, staying informed about current research is not only a best practice but an ethical obligation to ensure we are providing safe and effective care.

Harm Detection and Differentiating Counseling Models

Not all therapeutic models are equally beneficial, and some may even be detrimental if applied inappropriately. It's vital for clinicians to discern which models are supported by robust evidence and which are not. For instance, while mindfulness -based therapies have proven effective in managing anxiety and depression, they may not be suitable for individuals with certain types of trauma -related disorders, where grounding techniques might be more appropriate. Understanding these nuances allows clinicians to tailor their approaches to better meet the needs of their clients, thereby optimizing the therapeutic outcomes.

In conclusion, the integration of research into clinical practice serves as a critical tool for enhancing the quality of care provided to clients. By recognizing the limitations of intuition, valuing counterintuitive insights from research, distinguishing between universal principles and individual differences, and adhering to ethical standards of harm prevention, clinicians can ensure that their practice is both scientifically grounded and ethically sound. This commitment to evidence-based practice ultimately fosters a more effective and compassionate therapeutic environment, better serving the diverse needs of clients.

Dan Bates, Ph.D., is a clinical mental health counselor licensed in the state of Washington and certified nationally.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Further Recommendations Regarding The Future Of AI In Counseling

Ai work group recommendations.

The American Counseling Association has convened a panel of counseling experts representing academia, private practice and students to comprise its AI Work Group. The work group used research-based and contextual evidence; the ACA Code of Ethics; and clinical knowledge and skill to develop the following recommendations. The goal is to both prioritize client well-being, preferences, and values in the advent and application of AI, while informing counselors, counselor-educators and clients about the use of AI today. The recommendations also highlight the additional research needed to inform counseling practice as AI becomes a more widely available and accepted part of mental health care.

Recommendations for:

- Practicing Counselors

- Assessment, and Diagnosis

- Further Recommendations

Recommendation: Interdisciplinary collaboration on the development of AI for counseling Research on AI for counseling requires interdisciplinary efforts. We encourage the formulation of research teams comprising practicing counselors, counseling researchers, AI developers (e.g., computer scientists), and representatives from diverse client populations. This fosters a holistic approach to AI development, ensuring it meets clinical needs while being ethically sound and culturally sensitive.

Recommendation: Keep a keen eye on bias and potential discrimination in AI. AI shows great promise, and the potential for great peril comes with that. As AI relates to counseling, there is potential great harm in biased AI output. The training data and algorithms used to create the AI are the typical culprits, but with machine learning, users can “train” the AI to be harmful. See the infamous “Tay bot” case from Microsoft as an example. We should note that most therapeutic chatbots are designed to prevent the bot from going rogue, so to speak. Some chatbots have research backing for their efficacy as mental health support agents. We neither endorse or recommend against chatbots at this stage, but encourage more research and promote efforts to eliminate bias and discrimination in AI.

Recommendation: The benefits and risks identified for AI may shift with additional experience and research. Updates to statements and guidelines about AI are necessary, considering the ever-changing nature of AI. Few areas change and advance as quickly as AI. The ACA helps to ensure that counselors engage in practice based on rigorous research methodologies. Therefore, as AI advances, the ACA should retain an open mind, work to ensure safety measures are in place, and change its recommendations based on evidence.

Recommendation: Remember the value of human relationships. AI and technology in a general sense can change the nature of relationships. We know that social media use can impact the quality of human relationships. AI may change relationships further. Avatars, chatbots, and potentially humanoid robots may stress or otherwise challenge human-to-human relationships. We encourage you to remember the value of human relationships.

Recommendation: The ACA should consider including the topic of AI in the next revision of the ACA Code of Ethics. The 2014 ACA Code of Ethics does not currently mention Artificial Intelligence. The next publication of the Code should include references to the role of AI in counseling and supervision.

Recommendation: Consider adding ‘explicability’ in the ethics code as a principle in relation to AI work. Explicability is a term used to make AI less opaque (Ursin et al., 2023). Put another way, it implies that AI creators and users, counselors in this context, should have intelligibility and accountability (How does it work? Who is responsible?) (Floridi & Cowls, 2023).

Recommendation: Continuously evaluate and reflect. Counselors should regularly assess the impact of AI on their practice, seeking feedback from clients and colleagues. They should adjust their approach as needed to ensure the highest quality of care.

Recommendation: Monitor the role of AI in diagnosis and assessment. A growing body of literature has shown that AI has the potential to assist in diagnosis and assessment (Abd-alrazaq et al., 2022, Graham et al., 2019). AI may help in predicting, classifying, or subgrouping mental health conditions utilizing diverse data sources like Electronic Health Records (EHRs), brain imaging data, monitoring systems (e.g., smartphones, video), and social media platforms (Graham et al., 2019). With all of this in mind, we cannot solely rely on AI for diagnosis. The current state of AI technology does not fully encompass certain real-world aspects of clinical diagnosis in mental health care. AI does not adequately address essential elements like gathering a client's history, understanding their personal experiences, the reliability of electronic health records (EHR), the inherent uncertainties in diagnosing mental health conditions, and the vital role of empathy and direct communication in therapy. As we look to enhance diagnostic processes in counseling with AI, these critical factors must be integrated to ensure comprehensive, empathetic, and accurate care in the 21st century. Nevertheless, with continual advancements, it might not only be a tool to assist with diagnosis and assessment, but in some regards, it might one day surpass human-level abilities. The ACA should keep a keen eye on the diagnostic abilities of AI.

Recommendation: Developing client-centered AI tools. When developing AI tools for client use, we encourage the research and development team to involve clients and counselors in the design process, ensuring the AI tools are client-centered, address real-world needs, and respect client preferences and values.

Recommendation: Integrating Ethical AI Training into Counselor Professional Development Develop a comprehensive and continuous AI training program for counselors and trainees, emphasizing the proper and ethical use of AI in line with the need for continuing education according to the ACA Code of Ethics (C.2.f). This training program should include a detailed understanding of AI technologies, their applications in various counseling services, and crucial ethical considerations such as privacy and confidentiality. Additionally, the program should be part of counselors' ongoing professional development, incorporating regular updates and refreshers to keep pace with the rapidly evolving field of AI. This integrated approach ensures that counselors are both technically proficient and ethically informed in using AI tools.

Selected Publications and References

Abd-Alrazaq, A., Alhuwail, D., Schneider, J., Toro, C. T., Ahmed, A., Alzubaidi, M., ... & Househ, M. (2022). The performance of artificial intelligence-driven technologies in diagnosing mental disorders: an umbrella review. NPJ Digital Medicine, 5(1), 87.

American Counseling Association (2014). ACA Code of Ethics. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2022). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Machine learning and the city: Applications in architecture and urban design , 535-545.

Graham, S., Depp, C., Lee, E. E., Nebeker, C., Tu, X., Kim, H. C., & Jeste, D. V. (2019). Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: an overview. Current psychiatry reports, 21, 1-18.

Ursin, F., Lindner, F., Ropinski, T., Salloch, S., & Timmermann, C. (2023). Levels of explicability for medical artificial intelligence: What do we normatively need and what can we technically reach?. Ethik in der Medizin , 35 (2), 173-199.

AI Work Group Members

| S. Kent Butler, PhD University of Central Florida | Russell Fulmer, PhD Husson University | Morgan Stohlman Kent State University |

| Fallon Calandriello, PhD Northwestern University | Marcelle Giovannetti, EdD Messiah University- Mechanicsburg, PA | Olivia Uwamahoro Williams, PhD College of William and Mary |

| Wendell Callahan, PhD University of San Diego | Marty Jencius, PhD Kent State University | Yusen Zhai, PhD UAB School of Education |

| Lauren Epshteyn Northwestern University | Sidney Shaw, EdD Walden University | Chip Flater |

| Dania Fakhro, PhD University of North Carolina, Charlotte |

2461 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite 300, Alexandria, Va. 22314 | 800-347-6647 | (fax) 800-473-2329

My ACA Join Now Contact Us Privacy Policy Terms of Use © All Rights Reserved.

Counseling Psychology Research Paper Topics

This page provides a comprehensive list of counseling psychology research paper topics , tailored to support students in their exploration of this vital field. Counseling psychology encompasses a broad range of practices designed to help individuals overcome challenges, achieve personal growth, and improve overall well-being. By delving into topics that span from therapeutic approaches and techniques to the nuances of client-counselor dynamics and the impact of cultural and social diversity in counseling, this resource aims to inspire a deeper investigation into the ways counseling psychology can address the complexities of human experience. Highlighting both established and emerging areas within the discipline, such as the integration of technology in therapy and the ethical considerations unique to counseling practice, the topics presented are curated to encourage thoughtful research and contribute meaningful insights to the field. This collection is designed not only as an academic resource but also as a springboard for future professionals to engage with the pressing issues and innovations shaping the landscape of counseling psychology today.

100 Counseling Psychology Research Paper Topics

Counseling psychology, a dynamic and essential field, plays a critical role in enhancing personal and interpersonal functioning across the lifespan. It encompasses a wide array of practices aimed at supporting individuals through various challenges, promoting mental health and well-being, and facilitating growth and development. The breadth of research topics within counseling psychology mirrors its diverse applications, spanning clinical, educational, and research settings. From exploring innovative therapeutic approaches to understanding the intricate dynamics between clients and counselors, the field offers a rich landscape for investigation and discovery.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Principles and Applications

- Person-Centered Therapy: Techniques and Outcomes

- Integrative Approaches in Counseling

- The Effectiveness of Group Therapy

- Solution-Focused Brief Therapy: Strategies and Efficacy

- Mindfulness and Meditation in Therapy

- Narrative Therapy and Storytelling in Healing

- Art and Music Therapy: Methods and Mental Health Benefits

- Trauma-Informed Care in Counseling Practice

- Psychoanalytic Approaches in Modern Counseling

- Building Therapeutic Alliances: Strategies and Challenges

- The Impact of Counselor Self-Disclosure on Therapy Outcomes

- Client Resistance and Engagement Techniques

- Boundary Issues in the Therapeutic Relationship

- The Role of Empathy in Counseling

- Counseling Competencies and Client Satisfaction

- Confidentiality and Trust in Counseling

- Power Dynamics and Ethics in Client-Counselor Relationships

- Cultural Competence in Therapeutic Settings

- Feedback-Informed Treatment in Counseling

- Anxiety Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment

- Depression: Prevention Strategies and Therapeutic Interventions

- Wellness and Positive Psychology Interventions in Counseling

- The Role of Counseling in Suicide Prevention

- Substance Abuse Counseling: Approaches and Recovery Support

- Eating Disorders: Counseling Strategies and Recovery Models

- Counseling for Chronic Illness and Disability

- Stress Management Techniques in Therapy

- The Psychology of Happiness and Contentment

- Mental Health Stigma and Access to Counseling Services

- Multicultural Counseling Techniques and Outcomes

- Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Services

- Gender and Sexuality Issues in Counseling

- Counseling Immigrant and Refugee Populations

- Socioeconomic Factors in Mental Health and Therapy

- Cross-Cultural Communication Skills in Therapy

- Indigenous Healing Practices and Counseling

- Religion and Spirituality in Counseling Practice

- Age-Related Considerations in Counseling

- Counseling Veterans and Military Personnel

- Informed Consent in Counseling Practice

- Confidentiality and Privacy in the Digital Age

- Dual Relationships and Ethical Boundaries

- Legal Responsibilities of Counselors

- Ethical Decision-Making Models in Counseling

- Record-Keeping and Documentation Standards

- Managing Ethical Dilemmas with Supervision

- Cultural Sensitivity and Ethical Practice

- Ethical Considerations in Teletherapy

- Client Rights and Advocate Roles in Counseling

- Psychological Testing and Assessment in Counseling

- Outcome Measures and Their Importance in Therapy

- Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methods in Counseling

- Program Evaluation Techniques for Counseling Services

- Diagnostic Criteria and Differential Diagnosis in Mental Health

- The Use of Technology in Psychological Assessments

- Evaluating Therapeutic Interventions and Their Effectiveness

- Client Feedback Mechanisms and Therapy Adjustment

- Assessment of Risk Factors in Mental Health

- The Role of Neuropsychological Testing in Counseling

- Career Counseling Theories and Models

- Vocational Assessment Tools and Techniques

- Counseling for Work-Life Balance Issues

- Transition Services for Youth and Young Adults

- Retirement Planning and Counseling

- Workforce Re-entry and Counseling Support

- Entrepreneurship and Psychological Well-being

- Job Loss and Grief Counseling

- Career Change and Identity Shifts

- The Impact of Workplace Stress on Mental Health

- Play Therapy: Techniques and Outcomes

- Counseling Strategies for Adolescents with Behavioral Issues

- School-Based Mental Health Services

- Parent-Child Relationship Counseling

- Counseling for Gifted and Talented Youth

- Addressing Bullying and Cyberbullying in Counseling

- Childhood Trauma and Resilience Building

- Adolescent Substance Use and Counseling Interventions

- Special Education Needs and Counseling Support

- Peer Relationships and Social Skills Training

- Couple Therapy: Approaches and Challenges

- Family Dynamics and Systemic Therapy

- Counseling for Blended Families

- Divorce and Separation: Counseling Support for Families

- Parenting Strategies and Family Counseling

- Intimacy Issues and Sexual Health Counseling

- Conflict Resolution Techniques in Family Therapy

- Grief and Loss within the Family Context

- Family Therapy for Substance Abuse Issues

- Communication Skills Training for Couples and Families

- Efficacy of Online Therapy Platforms

- Digital Ethics: Confidentiality and Security in Online Counseling

- Utilizing Mobile Apps in Mental Health Interventions

- Virtual Reality Therapy: Applications and Limitations

- Social Media’s Impact on Mental Health and Counseling

- Online Support Groups and Peer Counseling

- Teletherapy: Best Practices and Client Outcomes

- Technology-Assisted Relaxation Techniques

- Cyberbullying: Counseling Strategies and Prevention

- Bridging the Digital Divide in Access to Mental Health Services

The exploration of counseling psychology research paper topics is a journey into the heart of what it means to support and understand human behavior and mental health. With a vast array of topics ranging from the intricacies of therapeutic relationships to the cutting-edge applications of technology in therapy, students are invited to delve deep into the subjects that resonate most with their academic interests and future aspirations. These topics not only offer a platform for significant academic contribution but also equip students with the knowledge and insights to advance counseling practices and mental health support in a rapidly evolving society. By engaging with these diverse research areas, students can play a crucial role in shaping the future of counseling psychology, fostering well-being, and making a meaningful impact on the lives of those they will serve.

What is Counseling Psychology

Counseling Psychology as an Essential Field of Study

Advancing Counseling Techniques, Understanding Client Needs, and Improving Therapeutic Outcomes

Research in counseling psychology is crucial for the continual advancement of counseling techniques, deepening the understanding of client needs, and enhancing therapeutic outcomes. Through empirical studies, researchers can evaluate the efficacy of various therapeutic approaches, tailoring interventions to meet the diverse needs of clients effectively. This ongoing research helps in identifying best practices, informing evidence-based treatments, and ensuring that counseling methods evolve in response to new psychological insights and societal changes. Moreover, research contributes to the training of counseling psychologists, equipping them with the latest tools and knowledge to support their clients effectively.

Investigations into client needs and preferences play a significant role in developing client-centered therapies that honor the individual’s experience and autonomy. Understanding the factors that contribute to psychological well-being and distress informs the creation of supportive environments and therapeutic relationships that facilitate change. Furthermore, research on therapeutic outcomes assesses the long-term impact of counseling services, guiding improvements in practice and highlighting the value of counseling psychology in mental health care.

Diverse Research Topics within Counseling Psychology

The field of counseling psychology encompasses a broad array of research topics, reflecting the complexity of human behavior and the myriad challenges individuals face throughout their lives. Topics include the development of effective therapeutic approaches and techniques, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, and narrative therapy, which are tailored to address specific psychological issues or client populations. Research on client-counselor dynamics delves into the factors that enhance therapeutic alliances, the role of empathy, and the impact of counselor characteristics on the counseling process.

Cultural and social diversity in counseling is another critical area of research, examining how cultural, racial, ethnic, and gender identities influence mental health and counseling outcomes. This research is instrumental in promoting culturally competent practices and addressing disparities in mental health care. Additionally, studies on ethics and legal issues ensure that counseling practices adhere to the highest standards of professional conduct, safeguarding client welfare and confidentiality. The exploration of these and other topics within counseling psychology is directly relevant to addressing current challenges in the field, driving innovations that enhance the quality and accessibility of mental health services.

Recent Advancements in Counseling Psychology Research

Recent advancements in counseling psychology research have significantly contributed to the field’s growth and the effectiveness of counseling services. Evidence-based practices, which rely on empirical evidence to guide treatment decisions, have gained prominence, ensuring that clients receive interventions proven to be effective. Research in this area not only evaluates the efficacy of traditional therapeutic approaches but also explores the potential of emerging therapies to address complex mental health issues.

Digital interventions, including online therapy, mobile apps for mental health, and teletherapy, represent another area of rapid advancement. These technologies have expanded access to counseling services, making psychological support more accessible to individuals in remote or underserved areas. Research into the effectiveness of these digital interventions is critical for understanding their impact on therapeutic outcomes and client satisfaction.

Furthermore, holistic approaches to mental health that consider the interplay between psychological, physical, social, and spiritual factors are increasingly being integrated into counseling psychology. Research in this area explores the benefits of incorporating wellness practices, such as exercise, nutrition, and meditation, into therapeutic interventions. These holistic approaches emphasize the whole person, supporting comprehensive well-being and resilience.

Ethical Considerations in Counseling Psychology Research and Practice

Ethical considerations are paramount in counseling psychology, guiding the conduct of researchers and practitioners to ensure the protection and respect of clients’ rights and well-being. Confidentiality is a fundamental ethical principle, safeguarding the privacy of client information and fostering a safe therapeutic environment. Research in counseling psychology often addresses the challenges and implications of maintaining confidentiality, especially in the context of digital interventions and group therapy settings.

Informed consent is another critical area of ethical focus, ensuring that clients are fully aware of the counseling process, their rights, and the potential risks and benefits of therapy. Research explores the best practices for obtaining informed consent, particularly when working with vulnerable populations or employing novel therapeutic techniques.

Therapist-client boundaries are also a significant concern, with research examining the importance of maintaining professional relationships to prevent harm and conflict of interest. Studies in this area contribute to the development of guidelines and training programs that help counselors navigate these ethical dilemmas, promoting integrity and trust within the counseling relationship.

Future Directions and Emerging Trends in Counseling Psychology

The future of counseling psychology research is poised to address a range of emerging trends and challenges, reflecting the evolving needs of society and advances in technology. Teletherapy has emerged as a critical area of focus, with researchers exploring its efficacy, the nuances of therapist-client interactions in virtual settings, and the ethical considerations unique to digital counseling formats. This trend underscores the field’s adaptation to technological advancements, ensuring that counseling services remain accessible and effective in a digital age.

Multicultural counseling continues to gain attention, with future research likely to delve deeper into the experiences of diverse client populations, the development of culturally sensitive therapeutic approaches, and the training of counselors in cultural competence. This area of study is crucial for addressing health disparities and promoting equity in mental health care.

Integrative health approaches that combine psychological, medical, and alternative therapies are also becoming more prominent. Research in this area examines the benefits of a holistic view of mental health, exploring how integrating various health modalities can support comprehensive well-being. These future directions in counseling psychology research reflect the field’s commitment to innovation, inclusivity, and the holistic well-being of individuals and communities.

The Role of Research in Shaping Effective Counseling Practices

Research plays an indispensable role in shaping the practices of counseling psychology, guiding the field toward more effective, inclusive, and ethical approaches to mental health care. Through the diligent exploration of diverse research topics, counseling psychology continues to advance our understanding of therapeutic processes, client needs, and the complex factors that contribute to mental health and wellness. As the field looks to the future, embracing emerging trends and addressing new challenges, the insights gained from research will remain pivotal in developing interventions that are both innovative and grounded in evidence. Ultimately, the continued emphasis on research in counseling psychology will ensure that the field remains at the forefront of promoting mental health, well-being, and positive change in the lives of individuals and communities.

Custom Writing Services by iResearchNet

iResearchNet is dedicated to providing customized writing services tailored specifically for students delving into the complexities of counseling psychology. Understanding the nuanced and multifaceted nature of counseling psychology research, we offer support designed to meet the unique challenges and demands of this field. Our services are crafted to assist students in navigating through their academic journey, providing them with the tools and resources necessary to produce insightful and impactful research papers that contribute meaningfully to the field.

- Expert degree-holding writers : Our team is composed of professionals who possess advanced degrees in counseling psychology and related areas, ensuring your work is informed by deep expertise.

- Custom written works : Every paper is uniquely tailored, reflecting your specific research questions and academic requirements, providing a personalized research experience.

- In-depth research : We commit to conducting thorough research, utilizing the latest studies and theoretical frameworks within the field of counseling psychology to enrich your paper.

- Custom formatting : Our writers are proficient in all major formatting styles, ensuring your paper meets the academic standards and preferences of your institution.

- Top quality : Quality underpins our services, with each project undergoing rigorous review to ensure it meets the highest academic standards and contributes valuable insights to the field.

- Customized solutions : Recognizing the diversity within counseling psychology, we offer solutions specifically designed to address your unique topic, ensuring relevance and depth.

- Flexible pricing : Our pricing model is designed with students in mind, offering competitive rates that accommodate your budget without compromising on quality.

- Short deadlines : For those urgent assignments, we have the capability to deliver high-quality work within tight timeframes, ensuring you meet your academic deadlines.

- Timely delivery : We understand the importance of punctuality in academic submissions; thus, we guarantee the timely delivery of your research paper.

- 24/7 support : Our support team is available around the clock, ready to assist you with any queries, updates, or additional support you may require throughout the process.

- Absolute privacy : Your privacy is paramount. We adhere to strict confidentiality policies to protect your personal and project information.

- Easy order tracking : Our user-friendly platform allows for seamless tracking of your order’s progress, providing transparency and peace of mind.

- Money-back guarantee : We stand by the quality of our work. If the final product does not meet your expectations, we offer a money-back guarantee, reaffirming our commitment to your satisfaction.

At iResearchNet, our commitment to supporting students in the field of counseling psychology is unwavering. Through our customized, high-quality writing services, we aim to empower your research endeavors, enabling you to explore and contribute to the vital conversations within counseling psychology. Our dedicated team of expert writers, comprehensive support, and tailored solutions are designed to facilitate your academic success and advance your understanding of the complex dynamics of mental health counseling. Choose iResearchNet for your counseling psychology research paper needs, and take a significant step towards achieving academic excellence and making a meaningful impact in the field.

Advance Your Counseling Psychology Research with iResearchNet!

Unlock the full potential of your academic endeavors in counseling psychology with the unparalleled support of iResearchNet. Our expert writing services are meticulously designed to cater to your specific research needs, offering a solid foundation for your exploration into the intricate world of counseling psychology. This is your opportunity to dive deep into the subjects that spark your passion, with the backing of a team committed to your success.

We invite you to take advantage of the wealth of knowledge, expertise, and specialized assistance that iResearchNet offers. Our team of expert degree-holding writers is equipped to handle topics across the spectrum of counseling psychology, ensuring your research is both profound and impactful. Whether you’re tackling complex theories, exploring innovative counseling methods, or examining the ethical dimensions of practice, we’re here to support your academic journey.

Experience the ease of our ordering process, designed with your convenience in mind, and benefit from our flexible pricing that accommodates your budget. With iResearchNet, you’re guaranteed top-quality, custom-written works, tailored to meet the rigorous demands of counseling psychology research. Plus, our commitment to timely delivery, absolute privacy, and round-the-clock support ensures a seamless and stress-free research experience.

Don’t let the complexities of counseling psychology research deter your academic progress. Choose iResearchNet for comprehensive support that empowers you to delve into your studies with confidence and clarity. Advance your counseling psychology research with iResearchNet and embark on a successful and insightful academic journey that sets the stage for a future of meaningful contributions to the field.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Innovative approaches to exploring processes of change in counseling psychology: Insights and principles for future research

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychology.

- 2 Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy.

- PMID: 32614223

- DOI: 10.1037/cou0000426

In recent years, innovative approaches have been implemented in counseling and psychotherapy research, creating new and exciting interdisciplinary subfields. The findings that emerged from the implementation of these approaches demonstrate their potential to deepen our understanding of therapeutic change. This article serves as an introduction to the "Innovative Approaches to Exploring Processes of Change in Counseling Psychology" special issue. The special issue includes articles representing several of the most promising approaches. Each article seeks to serve as a sourcebook for implementing a given approach in counseling research, in such areas as the assessment of coregulation processes, language processing, physiology, motion synchrony, event-related potentials, hormonal measures, and sociometric signals captured by a badge. The studies included in this special issue represent some of the most promising pathways for future studies and provide valuable resources for researchers, as well as clinicians interested in implementing such approaches and/or being educated consumers of empirical findings based on such approaches. This introduction synthesizes the articles in the special issue and proposes a list of guidelines for conducting and consuming research that implements new approaches for studying the process of therapeutic change. We believe that we are not far from the day when these approaches will be instrumental in everyday counseling practice, where they can assist therapists and patients in their collaborative efforts to reduce suffering and increase thriving. (PsycInfo Database Record (c) 2020 APA, all rights reserved).

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Machine learning and natural language processing in psychotherapy research: Alliance as example use case. Goldberg SB, Flemotomos N, Martinez VR, Tanana MJ, Kuo PB, Pace BT, Villatte JL, Georgiou PG, Van Epps J, Imel ZE, Narayanan SS, Atkins DC. Goldberg SB, et al. J Couns Psychol. 2020 Jul;67(4):438-448. doi: 10.1037/cou0000382. J Couns Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32614225 Free PMC article.

- Using event-related potentials to explore processes of change in counseling psychology. Matsen J, Perrone-McGovern K, Marmarosh C. Matsen J, et al. J Couns Psychol. 2020 Jul;67(4):500-508. doi: 10.1037/cou0000410. J Couns Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32614230 Review.

- Introduction to the special section "Big'er' Data": Scaling up psychotherapy research in counseling psychology. Owen J, Imel ZE. Owen J, et al. J Couns Psychol. 2016 Apr;63(3):247-8. doi: 10.1037/cou0000149. J Couns Psychol. 2016. PMID: 27078195

- Oxytocin as a biomarker of the formation of therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and counseling psychology. Zilcha-Mano S, Shamay-Tsoory S, Dolev-Amit T, Zagoory-Sharon O, Feldman R. Zilcha-Mano S, et al. J Couns Psychol. 2020 Jul;67(4):523-535. doi: 10.1037/cou0000386. J Couns Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32614232 Review.

- Physiological synchronization in the clinical process: A research primer. Kleinbub JR, Talia A, Palmieri A. Kleinbub JR, et al. J Couns Psychol. 2020 Jul;67(4):420-437. doi: 10.1037/cou0000383. J Couns Psychol. 2020. PMID: 32614224 Review.

- Therapists' Views of Mechanisms of Change in Psychotherapy: A Mixed-Method Approach. Tzur Bitan D, Shalev S, Abayed S. Tzur Bitan D, et al. Front Psychol. 2022 Apr 14;13:565800. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.565800. eCollection 2022. Front Psychol. 2022. PMID: 35496206 Free PMC article.

- Movement Synchrony in the Psychotherapy of Adolescents With Borderline Personality Pathology - A Dyadic Trait Marker for Resilience? Zimmermann R, Fürer L, Kleinbub JR, Ramseyer FT, Hütten R, Steppan M, Schmeck K. Zimmermann R, et al. Front Psychol. 2021 Jun 30;12:660516. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660516. eCollection 2021. Front Psychol. 2021. PMID: 34276484 Free PMC article.

- The Psychodynamic Approach During COVID-19 Emotional Crisis. Conversano C. Conversano C. Front Psychol. 2021 Apr 9;12:670196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670196. eCollection 2021. Front Psychol. 2021. PMID: 33897574 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Disentangling Trait-Like Between-Individual vs. State-Like Within-Individual Effects in Studying the Mechanisms of Change in CBT. Zilcha-Mano S, Webb CA. Zilcha-Mano S, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Jan 21;11:609585. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.609585. eCollection 2020. Front Psychiatry. 2021. PMID: 33551873 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- Israel Science Foundation

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- American Psychological Association

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

14 emerging trends

Vol. 53 No. 1 Print version: page 42

In 2022, psychological science will play an increasingly outsize role in the debate about how to solve the world’s most intractable challenges. Human behavior is at the heart of many of the biggest issues with which we grapple: inequality, climate change, the future of work, health and well-being, vaccine hesitancy, and misinformation. Psychologists have been asked not only to have a seat at the table but to take the lead on these issues and more (See the full list of emerging trends ).

Psychologists are being called upon to promote equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI): Amid a nationwide reckoning on race—and a 71% increase in EDI roles at organizations over the past 5 years—psychologists are increasingly being tapped to serve as chief diversity officers and act in other similar roles. But the field is also at an inflection point, being called upon to be more introspective about its own diversity in terms of the people who choose to become psychologists, the people who are the subjects of psychological research, and the people who have access to psychological services.

Psychologists are now the most requested experts by the mainstream media. As our culture increasingly sees mental health as an important piece of overall well-being, psychologists are being called to serve in a wider array of roles, including in entertainment, sports, advocacy, and technology.

On the technology front, the delivery and data collection of psychological services is gaining increased interest from venture capitalists. Private equity firms are expected to pour billions of dollars into mental health projects this year—psychologists working on these efforts say greater investments will help bring mental health care to millions of underserved patients.

That said, the urgent need for mental health services will be a trend for years to come. That is especially true among children: Mental health–related emergency department visits have increased 24% for children between ages 5 and 11 and 31% for those ages 12 to 17 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That trend will be exacerbated by the climate crisis, the destructive effects of which will fall disproportionately on communities that are already disadvantaged by social, economic, and political oppression.

Reporters and editors for the Monitor spoke with more than 100 psychologists to compile our annual trends report, which you’ll find on the following pages. As always, we appreciate your feedback and insights— email us .

The rise of psychologists

Reworking work

Open science is surging

Prominent issues in health care

Mental health, meet venture capital

Kicking stigma to the curb

New frontiers in neuroscience

Millions of women have left the workforce. Psychology can help bring them back

Children’s mental health is in crisis

Burnout and stress are everywhere

Climate change intensifies

Big data ups its reach

Psychology’s influence on public health messaging is growing

Telehealth proves its worth

Trent Spiner is editor in chief of the Monitor . Follow him on Twitter: @TrentSpiner

Recommended Reading

Contact apa, you may also like.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 September 2024

BRCA genetic testing and counseling in breast cancer: how do we meet our patients’ needs?

- Peter Dubsky ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9566-0209 1 , 2 ,

- Christian Jackisch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8537-3743 3 ,

- Seock-Ah Im 4 ,

- Kelly K. Hunt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9156-8723 5 ,

- Chien-Feng Li 6 ,

- Sheila Unger 7 &

- Shani Paluch-Shimon 8

npj Breast Cancer volume 10 , Article number: 77 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Breast cancer

- Genetic testing

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes that have been linked to inherited susceptibility of breast cancer. Germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (gBRCAm) are clinically relevant for treatment selection in breast cancer because they confer sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors. BRCA1/2 mutation status may also impact decisions on other systemic therapies, risk-reducing measures, and choice of surgery. Consequently, demand for gBRCAm testing has increased. Several barriers to genetic testing exist, including limited access to testing facilities, trained counselors, and psychosocial support, as well as the financial burden of testing. Here, we describe current implications of gBRCAm testing for patients with breast cancer, summarize current approaches to gBRCAm testing, provide potential solutions to support wider adoption of mainstreaming testing practices, and consider future directions of testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

BRCA-mutated breast cancer: the unmet need, challenges and therapeutic benefits of genetic testing

Genetic counseling and genetic testing for pathogenic germline mutations among high-risk patients previously diagnosed with breast cancer: a traceback approach

Mainstream genetic testing for breast cancer patients: early experiences from the Parkville Familial Cancer Centre

Introduction.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 were identified in the 1990s as genes linked to inherited susceptibility to breast cancer 1 , 2 . As tumor suppressor genes, they encode proteins that are crucial for the repair of complex DNA damage (such as double-strand breaks) by homologous recombination 3 . Germline mutations (i.e., pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants) in BRCA1/2 (gBRCAm) affecting this vital DNA repair pathway predispose individuals to developing breast cancer by impairing homologous recombination and causing genomic instability 3 .

The advent of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors has revolutionized the therapeutic landscape for cancers associated with gBRCAm, including breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancer 4 . For breast cancer, the focus of this article, PARP inhibitors are approved for early and advanced disease harboring gBRCAm based on the results of major clinical trials: for olaparib, OlympiAD and OlympiA; and for talazoparib, EMBRACA 5 , 6 , 7 . Given the opportunity for therapeutic targeting of gBRCAm, timely determination of gBRCAm status is critical to guide treatment decisions, and demand for gBRCAm testing has rapidly increased in recent years 8 . High-throughput sequencing technologies have made analysis of cancer-susceptibility genes rapid and affordable 8 . However, there is concern that the demand for gBRCAm testing may overwhelm current genetic services 9 . Furthermore, barriers at the individual-, provider-, systems-, and policy-levels exist, which restrict access to genetic testing resources and genetic counseling 10 . Innovative methods of mainstreaming genetic services may help overcome some of these challenges. Education and resources to support appropriate counseling for gBRCAm testing, as well as information on the implications of testing, and models for genetic test consent, are urgently needed to support the evolving clinical space.

In this review, we describe the implications of gBRCAm testing for potential surgical approaches and treatment in patients with breast cancer, summarize the various approaches to gBRCAm testing (including traditional and alternative models), provide practical resources to support mainstreaming of the gBRCAm testing pathway, and consider the relevance of genetic testing in breast cancer in the future.

Biology of BRCAm in breast cancer

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome accounts for approximately 10% of breast cancer cases 11 . BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the main genes involved in genetic susceptibility to breast cancer 12 . HBOC is associated with early-onset breast cancer, and an increased risk of other cancers, including ovarian, pancreatic, fallopian tube, and prostate 3 . The cumulative lifetime risk of developing breast cancer by age 80 years is high at 72 and 69% for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, respectively 13 . Female gBRCAm carriers also have a 44% ( BRCA1 ) and 17% ( BRCA2 ) cumulative risk of developing ovarian cancer 13 .

Patients harboring gBRCAm are more likely to develop breast cancer at a younger age, with approximately 12% of the cases arising in women ≤40 years of age attributed to pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in BRCA1 or BRCA2 14 . These breast cancers have distinct biological features: among individuals with g BRCA1 m, breast cancers are typically hormone receptor-negative (~76%) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative (94%), while breast cancers developing in individuals with g BRCA2 m are more frequently hormone receptor-positive (83%) and HER2-negative (89%) 14 .

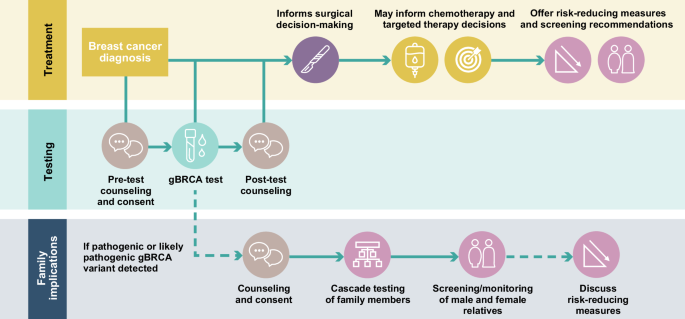

Goals of gBRCAm testing in breast cancer

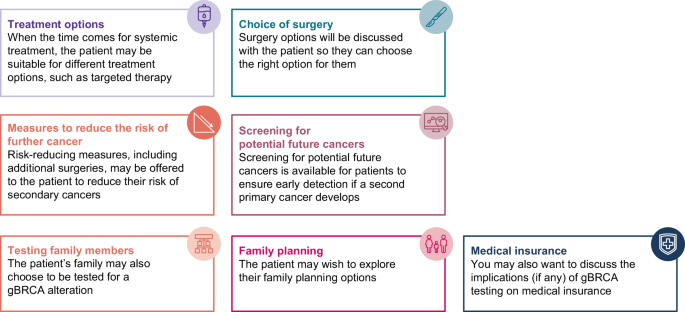

Available evidence regarding surgical and systemic treatment outcomes in patients with gBRCAm breast cancer highlights the importance of determining gBRCAm status prior to finalizing treatment decisions. Clinical practice guidelines further reinforce the role of gBRCAm testing in the context of treatment decision-making, beyond its importance for risk management and cascade testing 11 , 15 . The presence of gBRCAm may impact decisions about risk-reducing measures, choice of surgery, and systemic therapies (Fig. 1 ).

The pathway from gBRCAm testing to decisions relating to risk-reducing measures, choice of surgery, and systemic therapies.

Surgical decision-making

Breast-conserving surgery (bcs).

BCS aims to remove the breast tumor, with clear margins, in a manner that is cosmetically acceptable to the patient 16 . Although BCS is recommended for most patients with early-stage operable breast cancer 15 , the best approach for patients harboring gBRCAm is unclear. Practice guidelines recommend that gBRCAm status should not preclude the use of BCS as a surgical option for breast cancer 17 . However, these patients should be counseled regarding the risk of ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence, new primary breast cancer in the treated breast, and contralateral breast cancer, noting that intensified surveillance is a reasonable treatment strategy for breast cancer 11 , 17 .

Contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy (CRRM)

Some women with a confirmed gBRCAm opt for CRRM over BCS, which is removal of the unaffected breast to reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer, with or without the option of breast reconstruction 18 . A meta-analysis of outcomes in patients with gBRCAm found that CRRM reduced the relative risk of contralateral breast cancer by 93% versus surveillance and significantly increased overall survival (OS) versus surveillance 19 . It should be noted that benefit from CRRM was not maintained in all studies after adjusting for confounding factors 20 , and the absolute survival benefits of mastectomy (both ipsilateral and contralateral) are heavily dependent on patient prognosis; patients with aggressive types of disease, and especially those with little response from neoadjuvant systemic therapy regimens, are at higher risk from distant metastasis than local recurrence or a new primary in the contralateral breast.

Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO)

While RRSO is indicated in gBRCAm carriers, its effect on breast cancer risk reduction is not clear 21 . A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 21,022 patients demonstrated a 37 and 49% reduction in the risk of developing breast cancer following RRSO compared with no RRSO in patients with g BRCA1 m and g BRCA2 m, respectively, with the effect particularly pronounced in younger women with gBRCAm 22 . A retrospective analysis in 676 women harboring gBRCAm showed that oophorectomy decreased mortality in patients with g BRCA1 m and decreased breast cancer-specific mortality in patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-negative gBRCAm breast cancer 23 . Other studies have failed to demonstrate a benefit of RRSO on breast cancer risk 24 , 25 .

Systemic treatment decision-making

Chemotherapy.

gBRCAm advanced breast cancers are sensitive to platinum-based and non-platinum-based chemotherapy regimens 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 . For early breast cancer, patients with gBRCAm are treated with anthracycline/taxane-based regimens, similar to those individuals with sporadic breast cancers 30 . The clinical value of adding platinum therapy to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with gBRCAm tumors is inconclusive. The phase 3 BrighTNess trial concluded that the addition of carboplatin, with or without veliparib, to neoadjuvant chemotherapy significantly improved pathological complete response (pCR) rates among patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), regardless of gBRCA status 31 . Furthermore, a meta-analysis of neoadjuvant regimens in patients with gBRCAm TNBC reported improved pCR rates when platin derivatives were combined with anthracyclines and taxanes, although it was unclear if this combination offered a clinically meaningful benefit over standard chemotherapy alone 32 . However, GeparSixto and INFORM did not show a benefit to adding carboplatin or cisplatin, respectively, to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with gBRCAm early breast cancer 26 , 33 . Exploratory translational analyses of BrighTNess sought to elucidate the differences in benefit observed for patients with breast cancer and gBRCAm 34 . Higher PAM50 proliferation score, CIN70 score, and GeparSixto immune signature were associated with higher odds of pCR for both patients with and without gBRCAm, and thus have been proposed as potentially useful biomarkers for determining addition of carboplatin to neoadjuvant chemotherapy 34 , but have yet to be validated for clinical practice.

PARP inhibition

PARP inhibitors block the enzyme that has a vital role in repairing DNA single-strand breaks. They exploit the double-strand break repair deficiency of BRCAm cells, which accumulate unrepaired, toxic DNA double-strand breaks, thus resulting in tumor cell death (i.e., synthetic lethality). Olaparib is licensed for the adjuvant treatment of gBRCAm, HER2-negative high-risk early breast cancer, and for gBRCAm (tumor BRCAm in Japan), HER2-negative locally advanced (EU) or metastatic (EU and US) breast cancer. Talazoparib is approved for the treatment of gBRCAm, HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in the US, Europe, and several other countries worldwide.

For advanced gBRCAm HER2-negative breast cancer, PARP inhibitors were approved based on the results of the OlympiAD (olaparib) and EMBRACA (talazoparib) clinical trials 5 , 6 , 35 , 36 . In OlympiAD, olaparib had significantly improved median progression-free survival (PFS) versus standard chemotherapy treatment of physician’s choice (7.0 months vs 4.2 months; HR 0.58 [95% CI 0.43–0.80]; P < 0.001) in patients with gBRCAm HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer 5 . Median OS was 19.3 months for olaparib and 17.1 months for standard chemotherapy (HR 0.89 [95% CI 0.67–1.18]) 35 . In subanalyses, a potential OS benefit with first-line olaparib versus chemotherapy was observed (median 22.6 vs 14.7 months; HR 0.55 [95% CI 0.33–0.95]), with 3-year survival at 40.8% with olaparib and 12.8% with treatment of physician’s choice, which, notably, did not include a platinum regimen 5 , 35 . In EMBRACA, talazoparib significantly improved median PFS versus standard chemotherapy (8.6 vs 5.6 months; HR 0.54 [95% CI 0.41–0.71]; P < 0.001) in patients with gBRCAm advanced breast cancer 6 , with no observed improvements in OS 37 .

For early breast cancer, olaparib was approved based on the results of the phase 3 OlympiA study in patients with high-risk early gBRCAm HER2-negative breast cancer who had completed local treatment and neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy 7 , 38 . In the second prespecified analysis of OlympiA, adjuvant olaparib was associated with significantly improved OS versus placebo, with a 32% reduced risk of death (HR 0.68; 98.5% CI 0.47–0.97; P = 0.009) 7 . Significantly improved invasive disease-free survival (IDFS; HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.50–0.78) was also shown, consistent with the significantly improved IDFS reported at the first prespecified analysis (HR 0.58; 99.5% CI 0.41–0.82; P = 0.001) 7 .

These positive results in the adjuvant setting raised the question of whether PARP inhibitors may also have a place for neoadjuvant treatment of HER2-negative early breast cancer; however, trials have reported mixed results. In the BrighTNess trial, described above, addition of veliparib did not add benefit over neoadjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel alone 31 . The phase 2 GeparOLA study comparing neoadjuvant paclitaxel plus olaparib to paclitaxel/carboplatinum in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer and homologous recombinant deficiency did not meet its primary endpoint (exclusion of a pCR rate of ≤55%) 39 , but did report a numerically improved pCR rate with paclitaxel/olaparib followed by epirubicin/cyclophosphamide (55.1%) versus paclitaxel/carboplatinum (48.6%) followed by epirubicin/cyclophosphamide, and a more favorable tolerability profile for paclitaxel/olaparib 39 . In the single-arm neoTALA trial, patients with gBRCAm, early-stage TNBC were treated with talazoparib followed by definitive surgery 40 . Although neoadjuvant talazoparib was active, the pCR rates did not meet the prespecified threshold of efficacy 40 . Other neoadjuvant trials are ongoing to enhance our understanding of the potential use of PARP inhibitors in early breast cancer. Of potential interest is the opportunity to evaluate alternative PARP inhibitor combinations (e.g., with immunotherapy), and tailor therapy according to the patient. For example, in the ongoing OlympiaN trial (NCT05498155) patients with deleterious/suspected deleterious BRCAm and operable, early-stage, HER2-negative, ER-negative/ER-low breast cancer are assigned olaparib (lower-risk cohort) or olaparib plus durvalumab (higher-risk cohort), and assessed for pCR 41 .

PARP inhibitors are an important treatment strategy for gBRCAm breast cancer and rely on timely access to genetic testing to guide the most appropriate treatment selection, particularly in the early breast cancer setting.

Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors

A CDK4/6 inhibitor in combination with endocrine therapy is a recommended option for first-line treatment for certain patients with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative advanced or metastatic breast cancer 15 , 42 . Use of CDK4/6 inhibitors has also extended into earlier lines of treatment, with abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy a treatment option in the adjuvant setting for patients with hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative, high-risk breast cancer 15 , and positive results having been reported for ribociclib (NATALEE) 43 . While the optimal sequence is not known, recent guideline updates note that when patients are eligible for both adjuvant olaparib and abemaciclib then olaparib should be given first 30 , 44 . Real-world evidence has suggested that patients with hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer and gBRCAm may have inferior outcomes with CDK4/6 inhibition or endocrine therapy versus those without gBRCAm 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 . This emerging finding highlights the potential importance of early detection of gBRCAm in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer ahead of treatment selection, especially in light of recent CDK4/6 inhibitor approval in the early breast cancer setting.

Immunotherapy

There is limited evidence on the effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with gBRCAm breast cancer. A recent substudy from the phase 3 IMpassion130 trial of the anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibody atezolizumab showed that, in combination with nab-paclitaxel, patients with PD-L1-positive advanced TNBC had an OS and PFS benefit regardless of BRCA1/2 mutation status (germline or somatic) 50 . The efficacy of neoadjuvant PARP inhibition in combination with immunotherapy is under investigation; for example, olaparib in combination with durvalumab is being investigated in the aforementioned OlympiaN study 41 .

Screening and counseling for family members

The burden of gBRCAm in breast cancer extends beyond the affected individual, with other family members facing decisions regarding gBRCAm testing, as well as considerations of family planning. In case of a familial association, genetic testing is recommended by the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines ® ) for unaffected family members 21 . If a pre-symptomatic individual is identified as a carrier of gBRCAm, intensified surveillance for breast cancer is recommended, which differs per guideline but may include regular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, mammography, and/or clinical breast exam, with guidance provided based on age 11 , 21 . For patients harboring gBRCAm with a diagnosis of breast cancer who have not undergone bilateral mastectomy, National Comprehensive Cancer Network ® (NCCN ® ) recommends that breast MRI and mammography should continue as recommended, based on age 21 .

For individuals undergoing pre-symptomatic testing (known gBRCAm in a family member), it is recommended that pre-test counseling topics include options for screening and early detection, the benefits and disadvantages of risk-reducing surgery (including the extent of cancer risk reduction, risks associated with surgery, management of menopausal symptoms with RRSO, psychosocial and quality-of-life impacts, and life expectancy), the benefits and limitations of reconstructive surgery and reproductive options, and the psychological implications of pre-symptomatic diagnosis 11 , 21 . Consideration is required with regard to reproductive concerns and the psychosocial impact of undergoing RRSO in gBRCAm carriers 21 .

gBRCAm counseling and testing in clinical practice

Implementation of guideline recommendations for gbrcam counseling and testing.

Practice guidelines for genetic counseling and gBRCAm testing are predominantly based on personal and family history of breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and/or prostate cancer; young age at diagnosis; male breast cancer; and multiple tumors (breast and ovarian) in the same patient 21 . More than 32 guidelines for gBRCAm testing relevant to breast cancer exist worldwide 11 , 21 , 51 , 52 , and the recommendations are often inconsistent. Many guidelines do not include recommendations for genetic counseling, or only provide counseling recommendations for patients who have been identified as carriers of gBRCAm 51 . Some guidelines recommend gBRCAm testing after genetic counseling and personalized risk assessment, and/or if the result is likely to influence the individual’s choice of primary treatment 51 . Some guidelines recommend testing based upon percentage risk of harboring a BRCA mutation, but there is a lack of consensus on the threshold used to determine whether an individual is eligible for genetics clinic referral/testing (10% vs 5%) 21 , 53 , and some guidelines propose testing all patients under certain circumstances (e.g., with ER-positive advanced breast cancer and resistance to endocrine therapy), considering that PARP inhibitors have a greater risk-benefit ratio than chemotherapy 54 . There are limited treatment recommendations and algorithms for women with gBRCAm-associated advanced breast cancer 51 . Greater consensus and cohesion of guidelines would be useful for patients and the medical community covering the topics highlighted in Fig. 2 .

gBRCAm counseling and testing in clinical practice.

Disparities in gBRCAm testing in clinical practice

There has been a systemic underuse of gBRCAm testing over the past two decades, which has led to inappropriate and inconsistent testing and, consequently, missed opportunities for cancer prevention and management 55 . Historically, NCCN criteria have been seen to be the least restrictive of the models, identifying a larger percentage of carriers compared with other models. However, the complex nature of the NCCN criteria render them difficult to implement in real-world clinical practice 51 , with low adherence rates reported 56 . Expansion of NCCN criteria to include all women diagnosed at ≤65 years of age was shown to improve sensitivity of the selection criteria, without requiring testing of all women with breast cancer 57 .

Although recent data from some centers and countries suggest widespread routine gBRCAm testing 58 , a number of reports highlight the need for broader eligibility criteria for gBRCAm testing to ensure that more individuals can have access 55 , 57 , 59 , 60 . Notably, patient eligibility for gBRCAm testing has been shown to vary depending on different testing criteria and recommendations, ranging from over 98% using recent guidelines published by the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) to only around 30% eligibility using the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Cancer Estimation Algorithm (BOADICEA) criteria 55 , 57 (Fig. 3 ). Simplified, cost-effective eligibility criteria for gBRCAm testing, based on individual rather than family history criteria, have been proposed by the Mainstreaming Cancer Genetics (MCG) group. The five eligibility criteria include: (1) ovarian cancer diagnosis, (2) breast cancer diagnosed ≤45 years of age, (3) two primary breast cancers, both diagnosed ≤60 years of age, (4) TNBC diagnosis, and (5) male breast cancer diagnosis 55 . In an analysis of different guidelines, using these criteria would have tested 92% of people and detected 100% of gBRCAm carriers 55 . An additional sixth criteria (breast cancer, plus a parent, sibling, or child meeting any of the other criteria) further improved the eligibility rate to 97% (MCGplus) 55 , while expansion of NCCN criteria (v1.2020) to include individuals diagnosed at ≤65 years of age, as recommended by ASBrS, increased testing eligibility to include over 98% of BRCAm carriers 57 (Fig. 3 ). Both the MCG and MCGplus criteria were deemed cost-effective, with cost-effective ratios of $1330 and $1225 per discounted quality-adjusted life year for the MCG and MCGplus criteria, respectively 55 . Additional studies have sought to investigate the cost-effectiveness of BRCA testing in all patients with breast cancer, with several studies conducted in countries such as Australia, China, Norway, Malaysia, the UK, and the US finding this to be a potentially cost-effective strategy 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 .

The graph shows estimates of patient eligibility for BRCA testing among BRCAm carriers. Data to the left of the dashed line is reproduced from a report in 2019 by the MCG group assessing rates of testing eligibility by different criteria 55 , while the bar to the right of the dashed line illustrates the result of an analysis by ASBrS published in 2020, examining the effect of including all individuals meeting NCCN criteria v1.2020 plus those diagnosed with breast cancer at ≤65 years 57 . ASBrS, American Society of Breast Surgeons; BOADICEA, Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Cancer Estimation Algorithm (≥10 refers to a 10% or greater probability that a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation is present); MCG, Mainstreaming Cancer Genetics; MSS, Manchester Scoring System; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network ® (NCCN ® ).

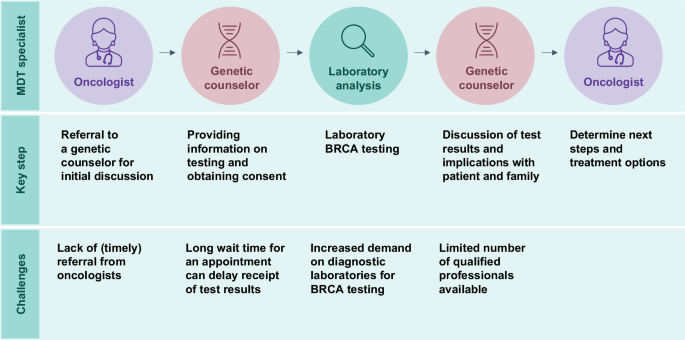

Traditional genetic counseling and testing pathway

The traditional pathway of genetic testing involves individualized patient referral to the genetics department for the management of pre-test genetic counseling, consenting, sample acquisition, and return of results (Fig. 4 ). Pre-test counseling, and the process of informed consent, focuses on giving patients sufficient information about the test, its limitations, and the consequences (including psychological) of a positive result, to enable an informed decision as to whether or not to proceed 9 . Patients who test positive for gBRCAm receive post-test support from a geneticist/genetic counselor/expert 9 , 66 .

MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Genetic professionals offering counseling include both medical genetic physicians (professionals with advanced training, such as an MD with a specialization in genetic medicine) and genetic counselors (professionals with a specialized Masters degree in genetic counseling) 67 , 68 . Genetic counseling by a trained genetics clinician has been shown to improve patient knowledge, understanding, and satisfaction among patients 69 , and is recommended in multiple guidelines 11 , 21 . While advantages of this type of care are clear, disadvantages include that it can be time-consuming, and a limited number of professionals are appropriately trained. When rapid access to test results is required to inform treatment decisions in a time-sensitive manner, especially for those undergoing upfront surgery, it may not be possible to maintain this workflow, and innovative alternatives may be required 70 .

Although genetic counseling is recommended, a dearth of adequately trained professionals in this field may limit access 71 , with some countries imposing legal requirements for practicing genetic counseling 72 . Where possible, non-geneticist physicians might feel the need to counsel and test patients themselves without support, despite increasing demands on their time and shorter appointment times 69 , 71 . Across Canada and the US, there are approximately 1.5 genetic counselors per 100,000 individuals, and it is estimated that double the workforce will be needed to meet future demands 73 . There has been an increase in genetic counselors reporting the use of multiple types of delivery models, including telephone and telegenetics, with an aim of improving access and efficiency of genetic counseling; however, barriers remain that can hinder implementation of these models 74 . In a large, US population-based study, only 62% of high-risk patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer who were tested had a genetic counselor session 75 . Furthermore, 66% of all patients, and 81% of high-risk patients, wanted testing but only 29 and 53% received it, respectively 75 . The most common reason for high-risk patients not being tested was “my doctor didn’t recommend it” 75 . Wait times to see genetic specialists can also be substantial. In the UK, the Nottingham University Hospitals National Health Service (NHS) Trust reports wait times of 12–14 weeks for an initial appointment and 4–6 months to receive results 76 . This highlights the need for alternative models of counseling and consenting of patients to ensure all eligible patients receive testing in a timely manner.

Systemic and societal barriers can impede equitable access to the benefits of genetic testing. Suboptimal testing rates among individuals of low socioeconomic status have been largely attributed to perceived/actual financial costs of genetic testing, with patients and healthcare providers often unclear as to whether genetic counseling services and follow-up care are covered by health insurance 10 , 77 . Strategies to improve testing rates in this patient demographic include the integration of genetic counselors into primary care settings to reduce travel time and costs to the patient 78 , and lobbying for expanded health insurance coverage for genetic counseling and testing services 79 .

Reports from US ovarian and breast cancer centers have consistently found racial/ethnic disparity in access to genetic testing, with referral rates being higher for non-Hispanic White women than for women of other races 80 , 81 , 82 . Lower awareness of the genetic basis of risk, incomplete family history, and mistrust of medical confidentiality may contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in referrals for genetic testing 79 , 83 . In addition, the detection of pathogenic variants may be decreased, and variants of uncertain significance increased, in non-White individuals 84 , 85 , 86 , as genomic reference databases provide poor genetic representation of non-White populations 87 , 88 . Whilst initiatives have been established to address gaps in the diversity of genomic data 89 , additional strategies are required to increase genetic testing rates among non-White populations. These include the development of culturally and linguistically tailored educational material, extended appointment availability, increased training of primary care-based specialists to mitigate unconscious or implicit biases, and a drive to recruit and train more healthcare providers from minority backgrounds 79 , 80 , 90 .

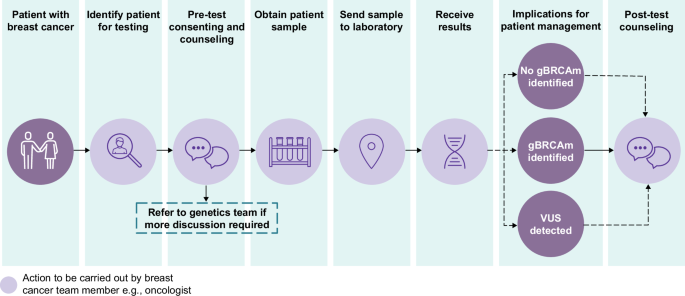

Mainstream genetic counseling and testing pathways

In mainstream genetic testing pathways, medical oncology teams are responsible for pre-test genetic counseling, obtaining consent, scheduling the genetic test, and using the results to guide treatment decisions (Fig. 5 ) 55 , 91 , 92 . Implementation of mainstream models has enabled more efficient testing of patients with ovarian cancer and has significantly increased the proportion of patients being offered genetic testing 93 , 94 , 95 .

VUS, variant of uncertain significance.