Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Integrating Critical Thinking Into the Classroom

- Share article

(This is the second post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

Part One ‘s guests were Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Today, Dr. Kulvarn Atwal, Elena Quagliarello, Dr. Donna Wilson, and Diane Dahl share their recommendations.

‘Learning Conversations’

Dr. Kulvarn Atwal is currently the executive head teacher of two large primary schools in the London borough of Redbridge. Dr. Atwal is the author of The Thinking School: Developing a Dynamic Learning Community , published by John Catt Educational. Follow him on Twitter @Thinkingschool2 :

In many classrooms I visit, students’ primary focus is on what they are expected to do and how it will be measured. It seems that we are becoming successful at producing students who are able to jump through hoops and pass tests. But are we producing children that are positive about teaching and learning and can think critically and creatively? Consider your classroom environment and the extent to which you employ strategies that develop students’ critical-thinking skills and their self-esteem as learners.

Development of self-esteem

One of the most significant factors that impacts students’ engagement and achievement in learning in your classroom is their self-esteem. In this context, self-esteem can be viewed to be the difference between how they perceive themselves as a learner (perceived self) and what they consider to be the ideal learner (ideal self). This ideal self may reflect the child that is associated or seen to be the smartest in the class. Your aim must be to raise students’ self-esteem. To do this, you have to demonstrate that effort, not ability, leads to success. Your language and interactions in the classroom, therefore, have to be aspirational—that if children persist with something, they will achieve.

Use of evaluative praise

Ensure that when you are praising students, you are making explicit links to a child’s critical thinking and/or development. This will enable them to build their understanding of what factors are supporting them in their learning. For example, often when we give feedback to students, we may simply say, “Well done” or “Good answer.” However, are the students actually aware of what they did well or what was good about their answer? Make sure you make explicit what the student has done well and where that links to prior learning. How do you value students’ critical thinking—do you praise their thinking and demonstrate how it helps them improve their learning?

Learning conversations to encourage deeper thinking

We often feel as teachers that we have to provide feedback to every students’ response, but this can limit children’s thinking. Encourage students in your class to engage in learning conversations with each other. Give as many opportunities as possible to students to build on the responses of others. Facilitate chains of dialogue by inviting students to give feedback to each other. The teacher’s role is, therefore, to facilitate this dialogue and select each individual student to give feedback to others. It may also mean that you do not always need to respond at all to a student’s answer.

Teacher modelling own thinking

We cannot expect students to develop critical-thinking skills if we aren’t modeling those thinking skills for them. Share your creativity, imagination, and thinking skills with the students and you will nurture creative, imaginative critical thinkers. Model the language you want students to learn and think about. Share what you feel about the learning activities your students are participating in as well as the thinking you are engaging in. Your own thinking and learning will add to the discussions in the classroom and encourage students to share their own thinking.

Metacognitive questioning

Consider the extent to which your questioning encourages students to think about their thinking, and therefore, learn about learning! Through asking metacognitive questions, you will enable your students to have a better understanding of the learning process, as well as their own self-reflections as learners. Example questions may include:

- Why did you choose to do it that way?

- When you find something tricky, what helps you?

- How do you know when you have really learned something?

‘Adventures of Discovery’

Elena Quagliarello is the senior editor of education for Scholastic News , a current events magazine for students in grades 3–6. She graduated from Rutgers University, where she studied English and earned her master’s degree in elementary education. She is a certified K–12 teacher and previously taught middle school English/language arts for five years:

Critical thinking blasts through the surface level of a topic. It reaches beyond the who and the what and launches students on a learning journey that ultimately unlocks a deeper level of understanding. Teaching students how to think critically helps them turn information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom. In the classroom, critical thinking teaches students how to ask and answer the questions needed to read the world. Whether it’s a story, news article, photo, video, advertisement, or another form of media, students can use the following critical-thinking strategies to dig beyond the surface and uncover a wealth of knowledge.

A Layered Learning Approach

Begin by having students read a story, article, or analyze a piece of media. Then have them excavate and explore its various layers of meaning. First, ask students to think about the literal meaning of what they just read. For example, if students read an article about the desegregation of public schools during the 1950s, they should be able to answer questions such as: Who was involved? What happened? Where did it happen? Which details are important? This is the first layer of critical thinking: reading comprehension. Do students understand the passage at its most basic level?

Ask the Tough Questions

The next layer delves deeper and starts to uncover the author’s purpose and craft. Teach students to ask the tough questions: What information is included? What or who is left out? How does word choice influence the reader? What perspective is represented? What values or people are marginalized? These questions force students to critically analyze the choices behind the final product. In today’s age of fast-paced, easily accessible information, it is essential to teach students how to critically examine the information they consume. The goal is to equip students with the mindset to ask these questions on their own.

Strike Gold

The deepest layer of critical thinking comes from having students take a step back to think about the big picture. This level of thinking is no longer focused on the text itself but rather its real-world implications. Students explore questions such as: Why does this matter? What lesson have I learned? How can this lesson be applied to other situations? Students truly engage in critical thinking when they are able to reflect on their thinking and apply their knowledge to a new situation. This step has the power to transform knowledge into wisdom.

Adventures of Discovery

There are vast ways to spark critical thinking in the classroom. Here are a few other ideas:

- Critical Expressionism: In this expanded response to reading from a critical stance, students are encouraged to respond through forms of artistic interpretations, dramatizations, singing, sketching, designing projects, or other multimodal responses. For example, students might read an article and then create a podcast about it or read a story and then act it out.

- Transmediations: This activity requires students to take an article or story and transform it into something new. For example, they might turn a news article into a cartoon or turn a story into a poem. Alternatively, students may rewrite a story by changing some of its elements, such as the setting or time period.

- Words Into Action: In this type of activity, students are encouraged to take action and bring about change. Students might read an article about endangered orangutans and the effects of habitat loss caused by deforestation and be inspired to check the labels on products for palm oil. They might then write a letter asking companies how they make sure the palm oil they use doesn’t hurt rain forests.

- Socratic Seminars: In this student-led discussion strategy, students pose thought-provoking questions to each other about a topic. They listen closely to each other’s comments and think critically about different perspectives.

- Classroom Debates: Aside from sparking a lively conversation, classroom debates naturally embed critical-thinking skills by asking students to formulate and support their own opinions and consider and respond to opposing viewpoints.

Critical thinking has the power to launch students on unforgettable learning experiences while helping them develop new habits of thought, reflection, and inquiry. Developing these skills prepares students to examine issues of power and promote transformative change in the world around them.

‘Quote Analysis’

Dr. Donna Wilson is a psychologist and the author of 20 books, including Developing Growth Mindsets , Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , and Five Big Ideas for Effective Teaching (2 nd Edition). She is an international speaker who has worked in Asia, the Middle East, Australia, Europe, Jamaica, and throughout the U.S. and Canada. Dr. Wilson can be reached at [email protected] ; visit her website at www.brainsmart.org .

Diane Dahl has been a teacher for 13 years, having taught grades 2-4 throughout her career. Mrs. Dahl currently teaches 3rd and 4th grade GT-ELAR/SS in Lovejoy ISD in Fairview, Texas. Follow her on Twitter at @DahlD, and visit her website at www.fortheloveofteaching.net :

A growing body of research over the past several decades indicates that teaching students how to be better thinkers is a great way to support them to be more successful at school and beyond. In the book, Teaching Students to Drive Their Brains , Dr. Wilson shares research and many motivational strategies, activities, and lesson ideas that assist students to think at higher levels. Five key strategies from the book are as follows:

- Facilitate conversation about why it is important to think critically at school and in other contexts of life. Ideally, every student will have a contribution to make to the discussion over time.

- Begin teaching thinking skills early in the school year and as a daily part of class.

- As this instruction begins, introduce students to the concept of brain plasticity and how their brilliant brains change during thinking and learning. This can be highly motivational for students who do not yet believe they are good thinkers!

- Explicitly teach students how to use the thinking skills.

- Facilitate student understanding of how the thinking skills they are learning relate to their lives at school and in other contexts.

Below are two lessons that support critical thinking, which can be defined as the objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgment.

Mrs. Dahl prepares her 3rd and 4th grade classes for a year of critical thinking using quote analysis .

During Native American studies, her 4 th grade analyzes a Tuscarora quote: “Man has responsibility, not power.” Since students already know how the Native Americans’ land had been stolen, it doesn’t take much for them to make the logical leaps. Critical-thought prompts take their thinking even deeper, especially at the beginning of the year when many need scaffolding. Some prompts include:

- … from the point of view of the Native Americans?

- … from the point of view of the settlers?

- How do you think your life might change over time as a result?

- Can you relate this quote to anything else in history?

Analyzing a topic from occupational points of view is an incredibly powerful critical-thinking tool. After learning about the Mexican-American War, Mrs. Dahl’s students worked in groups to choose an occupation with which to analyze the war. The chosen occupations were: anthropologist, mathematician, historian, archaeologist, cartographer, and economist. Then each individual within each group chose a different critical-thinking skill to focus on. Finally, they worked together to decide how their occupation would view the war using each skill.

For example, here is what each student in the economist group wrote:

- When U.S.A. invaded Mexico for land and won, Mexico ended up losing income from the settlements of Jose de Escandon. The U.S.A. thought that they were gaining possible tradable land, while Mexico thought that they were losing precious land and resources.

- Whenever Texas joined the states, their GDP skyrocketed. Then they went to war and spent money on supplies. When the war was resolving, Texas sold some of their land to New Mexico for $10 million. This allowed Texas to pay off their debt to the U.S., improving their relationship.

- A detail that converged into the Mexican-American War was that Mexico and the U.S. disagreed on the Texas border. With the resulting treaty, Texas ended up gaining more land and economic resources.

- Texas gained land from Mexico since both countries disagreed on borders. Texas sold land to New Mexico, which made Texas more economically structured and allowed them to pay off their debt.

This was the first time that students had ever used the occupations technique. Mrs. Dahl was astonished at how many times the kids used these critical skills in other areas moving forward.

Thanks to Dr. Auwal, Elena, Dr. Wilson, and Diane for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

The Will to Teach

Critical Thinking in the Classroom: A Guide for Teachers

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, teaching students the skill of critical thinking has become a priority. This powerful tool empowers students to evaluate information, make reasoned judgments, and approach problems from a fresh perspective. In this article, we’ll explore the significance of critical thinking and provide effective strategies to nurture this skill in your students.

Why is Fostering Critical Thinking Important?

Strategies to cultivate critical thinking, real-world example, concluding thoughts.

Critical thinking is a key skill that goes far beyond the four walls of a classroom. It equips students to better understand and interact with the world around them. Here are some reasons why fostering critical thinking is important:

- Making Informed Decisions: Critical thinking enables students to evaluate the pros and cons of a situation, helping them make informed and rational decisions.

- Developing Analytical Skills: Critical thinking involves analyzing information from different angles, which enhances analytical skills.

- Promoting Independence: Critical thinking fosters independence by encouraging students to form their own opinions based on their analysis, rather than relying on others.

Creating an environment that encourages critical thinking can be accomplished in various ways. Here are some effective strategies:

- Socratic Questioning: This method involves asking thought-provoking questions that encourage students to think deeply about a topic. For example, instead of asking, “What is the capital of France?” you might ask, “Why do you think Paris became the capital of France?”

- Debates and Discussions: Debates and open-ended discussions allow students to explore different viewpoints and challenge their own beliefs. For example, a debate on a current event can engage students in critical analysis of the situation.

- Teaching Metacognition: Teaching students to think about their own thinking can enhance their critical thinking skills. This can be achieved through activities such as reflective writing or journaling.

- Problem-Solving Activities: As with developing problem-solving skills , activities that require students to find solutions to complex problems can also foster critical thinking.

As a school leader, I’ve seen the transformative power of critical thinking. During a school competition, I observed a team of students tasked with proposing a solution to reduce our school’s environmental impact. Instead of jumping to obvious solutions, they critically evaluated multiple options, considering the feasibility, cost, and potential impact of each. They ultimately proposed a comprehensive plan that involved water conservation, waste reduction, and energy efficiency measures. This demonstrated their ability to critically analyze a problem and develop an effective solution.

Critical thinking is an essential skill for students in the 21st century. It equips them to understand and navigate the world in a thoughtful and informed manner. As a teacher, incorporating strategies to foster critical thinking in your classroom can make a lasting impact on your students’ educational journey and life beyond school.

1. What is critical thinking? Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment.

2. Why is critical thinking important for students? Critical thinking helps students make informed decisions, develop analytical skills, and promotes independence.

3. What are some strategies to cultivate critical thinking in students? Strategies can include Socratic questioning, debates and discussions, teaching metacognition, and problem-solving activities.

4. How can I assess my students’ critical thinking skills? You can assess critical thinking skills through essays, presentations, discussions, and problem-solving tasks that require thoughtful analysis.

5. Can critical thinking be taught? Yes, critical thinking can be taught and nurtured through specific teaching strategies and a supportive learning environment.

Related Posts

7 simple strategies for strong student-teacher relationships.

Getting to know your students on a personal level is the first step towards building strong relationships. Show genuine interest in their lives outside the classroom.

Connecting Learning to Real-World Contexts: Strategies for Teachers

When students see the relevance of their classroom lessons to their everyday lives, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and retain information.

Encouraging Active Involvement in Learning: Strategies for Teachers

Active learning benefits students by improving retention of information, enhancing critical thinking skills, and encouraging a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

Collaborative and Cooperative Learning: A Guide for Teachers

These methods encourage students to work together, share ideas, and actively participate in their education.

Experiential Teaching: Role-Play and Simulations in Teaching

These interactive techniques allow students to immerse themselves in practical, real-world scenarios, thereby deepening their understanding and retention of key concepts.

Project-Based Learning Activities: A Guide for Teachers

Project-Based Learning is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic approach to teaching, where students explore real-world problems or challenges.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Campus Life

- ...a student.

- ...a veteran.

- ...an alum.

- ...a parent.

- ...faculty or staff.

- Class Schedule

- Crisis Resources

- People Finder

- Change Password

UTC RAVE Alert

Critical thinking and problem-solving, jump to: , what is critical thinking, characteristics of critical thinking, why teach critical thinking.

- Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical Thinking Skills

References and Resources

When examining the vast literature on critical thinking, various definitions of critical thinking emerge. Here are some samples:

- "Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action" (Scriven, 1996).

- "Most formal definitions characterize critical thinking as the intentional application of rational, higher order thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, problem recognition and problem solving, inference, and evaluation" (Angelo, 1995, p. 6).

- "Critical thinking is thinking that assesses itself" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996b).

- "Critical thinking is the ability to think about one's thinking in such a way as 1. To recognize its strengths and weaknesses and, as a result, 2. To recast the thinking in improved form" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996c).

Perhaps the simplest definition is offered by Beyer (1995) : "Critical thinking... means making reasoned judgments" (p. 8). Basically, Beyer sees critical thinking as using criteria to judge the quality of something, from cooking to a conclusion of a research paper. In essence, critical thinking is a disciplined manner of thought that a person uses to assess the validity of something (statements, news stories, arguments, research, etc.).

Back

Wade (1995) identifies eight characteristics of critical thinking. Critical thinking involves asking questions, defining a problem, examining evidence, analyzing assumptions and biases, avoiding emotional reasoning, avoiding oversimplification, considering other interpretations, and tolerating ambiguity. Dealing with ambiguity is also seen by Strohm & Baukus (1995) as an essential part of critical thinking, "Ambiguity and doubt serve a critical-thinking function and are a necessary and even a productive part of the process" (p. 56).

Another characteristic of critical thinking identified by many sources is metacognition. Metacognition is thinking about one's own thinking. More specifically, "metacognition is being aware of one's thinking as one performs specific tasks and then using this awareness to control what one is doing" (Jones & Ratcliff, 1993, p. 10 ).

In the book, Critical Thinking, Beyer elaborately explains what he sees as essential aspects of critical thinking. These are:

- Dispositions: Critical thinkers are skeptical, open-minded, value fair-mindedness, respect evidence and reasoning, respect clarity and precision, look at different points of view, and will change positions when reason leads them to do so.

- Criteria: To think critically, must apply criteria. Need to have conditions that must be met for something to be judged as believable. Although the argument can be made that each subject area has different criteria, some standards apply to all subjects. "... an assertion must... be based on relevant, accurate facts; based on credible sources; precise; unbiased; free from logical fallacies; logically consistent; and strongly reasoned" (p. 12).

- Argument: Is a statement or proposition with supporting evidence. Critical thinking involves identifying, evaluating, and constructing arguments.

- Reasoning: The ability to infer a conclusion from one or multiple premises. To do so requires examining logical relationships among statements or data.

- Point of View: The way one views the world, which shapes one's construction of meaning. In a search for understanding, critical thinkers view phenomena from many different points of view.

- Procedures for Applying Criteria: Other types of thinking use a general procedure. Critical thinking makes use of many procedures. These procedures include asking questions, making judgments, and identifying assumptions.

Oliver & Utermohlen (1995) see students as too often being passive receptors of information. Through technology, the amount of information available today is massive. This information explosion is likely to continue in the future. Students need a guide to weed through the information and not just passively accept it. Students need to "develop and effectively apply critical thinking skills to their academic studies, to the complex problems that they will face, and to the critical choices they will be forced to make as a result of the information explosion and other rapid technological changes" (Oliver & Utermohlen, p. 1 ).

As mentioned in the section, Characteristics of Critical Thinking , critical thinking involves questioning. It is important to teach students how to ask good questions, to think critically, in order to continue the advancement of the very fields we are teaching. "Every field stays alive only to the extent that fresh questions are generated and taken seriously" (Center for Critical Thinking, 1996a ).

Beyer sees the teaching of critical thinking as important to the very state of our nation. He argues that to live successfully in a democracy, people must be able to think critically in order to make sound decisions about personal and civic affairs. If students learn to think critically, then they can use good thinking as the guide by which they live their lives.

Teaching Strategies to Help Promote Critical Thinking

The 1995, Volume 22, issue 1, of the journal, Teaching of Psychology , is devoted to the teaching critical thinking. Most of the strategies included in this section come from the various articles that compose this issue.

- CATS (Classroom Assessment Techniques): Angelo stresses the use of ongoing classroom assessment as a way to monitor and facilitate students' critical thinking. An example of a CAT is to ask students to write a "Minute Paper" responding to questions such as "What was the most important thing you learned in today's class? What question related to this session remains uppermost in your mind?" The teacher selects some of the papers and prepares responses for the next class meeting.

- Cooperative Learning Strategies: Cooper (1995) argues that putting students in group learning situations is the best way to foster critical thinking. "In properly structured cooperative learning environments, students perform more of the active, critical thinking with continuous support and feedback from other students and the teacher" (p. 8).

- Case Study /Discussion Method: McDade (1995) describes this method as the teacher presenting a case (or story) to the class without a conclusion. Using prepared questions, the teacher then leads students through a discussion, allowing students to construct a conclusion for the case.

- Using Questions: King (1995) identifies ways of using questions in the classroom:

- Reciprocal Peer Questioning: Following lecture, the teacher displays a list of question stems (such as, "What are the strengths and weaknesses of...). Students must write questions about the lecture material. In small groups, the students ask each other the questions. Then, the whole class discusses some of the questions from each small group.

- Reader's Questions: Require students to write questions on assigned reading and turn them in at the beginning of class. Select a few of the questions as the impetus for class discussion.

- Conference Style Learning: The teacher does not "teach" the class in the sense of lecturing. The teacher is a facilitator of a conference. Students must thoroughly read all required material before class. Assigned readings should be in the zone of proximal development. That is, readings should be able to be understood by students, but also challenging. The class consists of the students asking questions of each other and discussing these questions. The teacher does not remain passive, but rather, helps "direct and mold discussions by posing strategic questions and helping students build on each others' ideas" (Underwood & Wald, 1995, p. 18 ).

- Use Writing Assignments: Wade sees the use of writing as fundamental to developing critical thinking skills. "With written assignments, an instructor can encourage the development of dialectic reasoning by requiring students to argue both [or more] sides of an issue" (p. 24).

- Written dialogues: Give students written dialogues to analyze. In small groups, students must identify the different viewpoints of each participant in the dialogue. Must look for biases, presence or exclusion of important evidence, alternative interpretations, misstatement of facts, and errors in reasoning. Each group must decide which view is the most reasonable. After coming to a conclusion, each group acts out their dialogue and explains their analysis of it.

- Spontaneous Group Dialogue: One group of students are assigned roles to play in a discussion (such as leader, information giver, opinion seeker, and disagreer). Four observer groups are formed with the functions of determining what roles are being played by whom, identifying biases and errors in thinking, evaluating reasoning skills, and examining ethical implications of the content.

- Ambiguity: Strohm & Baukus advocate producing much ambiguity in the classroom. Don't give students clear cut material. Give them conflicting information that they must think their way through.

- Angelo, T. A. (1995). Beginning the dialogue: Thoughts on promoting critical thinking: Classroom assessment for critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 6-7.

- Beyer, B. K. (1995). Critical thinking. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996a). The role of questions in thinking, teaching, and learning. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996b). Structures for student self-assessment. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univclass/trc.nclk

- Center for Critical Thinking (1996c). Three definitions of critical thinking [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Cooper, J. L. (1995). Cooperative learning and critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 7-8.

- Jones, E. A. & Ratcliff, G. (1993). Critical thinking skills for college students. National Center on Postsecondary Teaching, Learning, and Assessment, University Park, PA. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 358 772)

- King, A. (1995). Designing the instructional process to enhance critical thinking across the curriculum: Inquiring minds really do want to know: Using questioning to teach critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22 (1) , 13-17.

- McDade, S. A. (1995). Case study pedagogy to advance critical thinking. Teaching Psychology, 22(1), 9-10.

- Oliver, H. & Utermohlen, R. (1995). An innovative teaching strategy: Using critical thinking to give students a guide to the future.(Eric Document Reproduction Services No. 389 702)

- Robertson, J. F. & Rane-Szostak, D. (1996). Using dialogues to develop critical thinking skills: A practical approach. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 39(7), 552-556.

- Scriven, M. & Paul, R. (1996). Defining critical thinking: A draft statement for the National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/univlibrary/library.nclk

- Strohm, S. M., & Baukus, R. A. (1995). Strategies for fostering critical thinking skills. Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, 50 (1), 55-62.

- Underwood, M. K., & Wald, R. L. (1995). Conference-style learning: A method for fostering critical thinking with heart. Teaching Psychology, 22(1), 17-21.

- Wade, C. (1995). Using writing to develop and assess critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 24-28.

Other Reading

- Bean, J. C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, & active learning in the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

- Bernstein, D. A. (1995). A negotiation model for teaching critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 22-24.

- Carlson, E. R. (1995). Evaluating the credibility of sources. A missing link in the teaching of critical thinking. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 39-41.

- Facione, P. A., Sanchez, C. A., Facione, N. C., & Gainen, J. (1995). The disposition toward critical thinking. The Journal of General Education, 44(1), 1-25.

- Halpern, D. F., & Nummedal, S. G. (1995). Closing thoughts about helping students improve how they think. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 82-83.

- Isbell, D. (1995). Teaching writing and research as inseparable: A faculty-librarian teaching team. Reference Services Review, 23(4), 51-62.

- Jones, J. M. & Safrit, R. D. (1994). Developing critical thinking skills in adult learners through innovative distance learning. Paper presented at the International Conference on the practice of adult education and social development. Jinan, China. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 373 159)

- Sanchez, M. A. (1995). Using critical-thinking principles as a guide to college-level instruction. Teaching of Psychology, 22(1), 72-74.

- Spicer, K. L. & Hanks, W. E. (1995). Multiple measures of critical thinking skills and predisposition in assessment of critical thinking. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, San Antonio, TX. (Eric Document Reproduction Services No. ED 391 185)

- Terenzini, P. T., Springer, L., Pascarella, E. T., & Nora, A. (1995). Influences affecting the development of students' critical thinking skills. Research in Higher Education, 36(1), 23-39.

On the Internet

- Carr, K. S. (1990). How can we teach critical thinking. Eric Digest. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://ericps.ed.uiuc.edu/eece/pubs/digests/1990/carr90.html

- The Center for Critical Thinking (1996). Home Page. Available HTTP: http://www.criticalthinking.org/University/

- Ennis, Bob (No date). Critical thinking. [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://www.cof.orst.edu/cof/teach/for442/ct.htm

- Montclair State University (1995). Curriculum resource center. Critical thinking resources: An annotated bibliography. [On-line]. Available HTTP: http://www.montclair.edu/Pages/CRC/Bibliographies/CriticalThinking.html

- No author, No date. Critical Thinking is ... [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://library.usask.ca/ustudy/critical/

- Sheridan, Marcia (No date). Internet education topics hotlink page. [On-line], April 4, 1997. Available HTTP: http://sun1.iusb.edu/~msherida/topics/critical.html

Walker Center for Teaching and Learning

- 433 Library

- Dept 4354

- 615 McCallie Ave

- 423-425-4188

CTL Guide to the Critical Thinking Hub Area

Guidance for designing or teaching a Critical Thinking (CRT) course, including assignment resources and examples.

From the BU Hub Curriculum Guide

“The ability to think critically is the fundamental characteristic of an educated person. It is required for just, civil society and governance, prized by employers, and essential for the growth of wisdom. Critical thinking is what most people name first when asked about the essential components of a college education. From identifying and questioning assumptions, to weighing evidence before accepting an opinion or drawing a conclusion—all BU students will actively learn the habits of mind that characterize critical thinking, develop the self-discipline it requires, and practice it often, in varied contexts, across their education.” For more context around this Hub area, see this Hub page .

Learning Outcomes

Courses and cocurricular activities in this area must have all outcomes.

- Students will both gain critical thinking skills and be able to specify the components of critical thinking appropriate to a discipline or family of disciplines. These may include habits of distinguishing deductive from inductive modes of inference, methods of adjudicating disputes, recognizing common logical fallacies and cognitive biases, translating ordinary language into formal argument, distinguishing empirical claims about matters of fact from normative or evaluative judgments, and/or recognizing the ways in which emotional responses or cultural assumptions can affect reasoning processes.

- Drawing on skills developed in class, students will be able to critically evaluate, analyze, and generate arguments, bodies of evidence, and/or claims, including their own.

If you are proposing a CRT course or if you want to learn more about these outcomes, please see this Interpretive Document . Interpretive Documents, written by the General Education Committee , are designed to answer questions faculty have raised about Hub policies, practices, and learning outcomes as a part of the course approval process. To learn more about the proposal process, start here .

Area Specific Resources

- Richard Paul , Center for Critical Thinking ( criticalthinking.org ). Includes sample lessons, syllabi, teaching suggestions, and interdisciplinary resources and examples.

- John Bean ’s Engaging Ideas – The Professor’s Guide to integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active learning in the Classroom is an invaluable resource for developing classroom activities and assignments that promote critical thinking and the scaffolding of writing.

Assignment Ideas

Weekly writing assignments.

These assignments are question-driven, thematic, and require students to integrate disciplinary and critical thinking literature to evaluate the validity of arguments in case studies, as well as the connections among method, theory, and practice in the case studies. Here, students are asked to utilize a chosen critical thinking framework throughout their written responses. These assignments can evolve during the semester by prompting students to address increasing complex case studies and arguments while also evaluating their own opinions using evidence from the readings. Along the way, students have ample opportunities for self-reflection, peer feedback, and coaching by the instructor.

Argument Mapping

A visual technique that allows students to analyze persuasive prose. This technique allows students to evaluate arguments–that is, distinguish valid from invalid arguments, and evaluate the soundness of different arguments. Advanced usage can help students organize and navigate complex information, encourage clearly articulated reasoning, and promote quick and effective communication. To learn more, please explore the following resources:

- Carnegie Mellon University’s Open Learning Initiative course on this topic provides an excellent i ntroduction to exploring and understanding arguments. The course explains what the parts of an argument are, how to break arguments into their component parts, and how to create diagrams to show how those parts relate to each other.

- Philmaps.com provides a handout that introduces the concept of argument mapping to students, and also includes a number of sample activities that faculty can use to introduce students to argument mapping.

- Mindmup’s Argument Visualization platform is an online mind map tool easily leveraged for creating argument maps.

Research Proposal and Final Research Paper

Demonstrates students’ ability to identify, distinguish, and assess ideological and evaluative claims and judgments about the selected research topic. Throughout the semester, students have the opportunity to practice their ability to evaluate the validity of arguments, including their own beliefs about the topic. Formative and summative assessments are provided to students at regular intervals and during each stage of the project.

Facilitating discussion that Presses Students for Accuracy and Expanded Reasoning . This resource is part of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education “Instructional Moves” video series.

Additional sample assignments and assessments can be found throughout the selected Resources section located above.

Course Design Questions

As you are integrating critical thinking into your course, here are a few questions that you might consider:

- What framework/vocabulary/process do you use to teach the key elements of critical thinking in your course?

- What assigned readings or other materials do you use to teach critical thinking specifically?

- Do students have opportunities throughout the semester to apply and practice these skills and receive feedback?

- What graded assignments evaluate how well students can both identify the key elements of critical thinking and demonstrate their ability to evaluate the validity of arguments (including their own)?

You may also be interested in:

Thinking critically in college workshop, ctl guide to the teamwork/collaboration hub area, ctl guide to writing-intensive hub courses, ctl guide to the individual in community hub area, ctl guide to digital/multimedia expression, oral & signed communication hub guide, creativity/innovation hub guide, research and information literacy hub guide.

- Our Mission

Helping Students Hone Their Critical Thinking Skills

Used consistently, these strategies can help middle and high school teachers guide students to improve much-needed skills.

Critical thinking skills are important in every discipline, at and beyond school. From managing money to choosing which candidates to vote for in elections to making difficult career choices, students need to be prepared to take in, synthesize, and act on new information in a world that is constantly changing.

While critical thinking might seem like an abstract idea that is tough to directly instruct, there are many engaging ways to help students strengthen these skills through active learning.

Make Time for Metacognitive Reflection

Create space for students to both reflect on their ideas and discuss the power of doing so. Show students how they can push back on their own thinking to analyze and question their assumptions. Students might ask themselves, “Why is this the best answer? What information supports my answer? What might someone with a counterargument say?”

Through this reflection, students and teachers (who can model reflecting on their own thinking) gain deeper understandings of their ideas and do a better job articulating their beliefs. In a world that is go-go-go, it is important to help students understand that it is OK to take a breath and think about their ideas before putting them out into the world. And taking time for reflection helps us more thoughtfully consider others’ ideas, too.

Teach Reasoning Skills

Reasoning skills are another key component of critical thinking, involving the abilities to think logically, evaluate evidence, identify assumptions, and analyze arguments. Students who learn how to use reasoning skills will be better equipped to make informed decisions, form and defend opinions, and solve problems.

One way to teach reasoning is to use problem-solving activities that require students to apply their skills to practical contexts. For example, give students a real problem to solve, and ask them to use reasoning skills to develop a solution. They can then present their solution and defend their reasoning to the class and engage in discussion about whether and how their thinking changed when listening to peers’ perspectives.

A great example I have seen involved students identifying an underutilized part of their school and creating a presentation about one way to redesign it. This project allowed students to feel a sense of connection to the problem and come up with creative solutions that could help others at school. For more examples, you might visit PBS’s Design Squad , a resource that brings to life real-world problem-solving.

Ask Open-Ended Questions

Moving beyond the repetition of facts, critical thinking requires students to take positions and explain their beliefs through research, evidence, and explanations of credibility.

When we pose open-ended questions, we create space for classroom discourse inclusive of diverse, perhaps opposing, ideas—grounds for rich exchanges that support deep thinking and analysis.

For example, “How would you approach the problem?” and “Where might you look to find resources to address this issue?” are two open-ended questions that position students to think less about the “right” answer and more about the variety of solutions that might already exist.

Journaling, whether digitally or physically in a notebook, is another great way to have students answer these open-ended prompts—giving them time to think and organize their thoughts before contributing to a conversation, which can ensure that more voices are heard.

Once students process in their journal, small group or whole class conversations help bring their ideas to life. Discovering similarities between answers helps reveal to students that they are not alone, which can encourage future participation in constructive civil discourse.

Teach Information Literacy

Education has moved far past the idea of “Be careful of what is on Wikipedia, because it might not be true.” With AI innovations making their way into classrooms, teachers know that informed readers must question everything.

Understanding what is and is not a reliable source and knowing how to vet information are important skills for students to build and utilize when making informed decisions. You might start by introducing the idea of bias: Articles, ads, memes, videos, and every other form of media can push an agenda that students may not see on the surface. Discuss credibility, subjectivity, and objectivity, and look at examples and nonexamples of trusted information to prepare students to be well-informed members of a democracy.

One of my favorite lessons is about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus . This project asks students to explore what appears to be a very real website that provides information on this supposedly endangered animal. It is a wonderful, albeit over-the-top, example of how something might look official even when untrue, revealing that we need critical thinking to break down “facts” and determine the validity of the information we consume.

A fun extension is to have students come up with their own website or newsletter about something going on in school that is untrue. Perhaps a change in dress code that requires everyone to wear their clothes inside out or a change to the lunch menu that will require students to eat brussels sprouts every day.

Giving students the ability to create their own falsified information can help them better identify it in other contexts. Understanding that information can be “too good to be true” can help them identify future falsehoods.

Provide Diverse Perspectives

Consider how to keep the classroom from becoming an echo chamber. If students come from the same community, they may have similar perspectives. And those who have differing perspectives may not feel comfortable sharing them in the face of an opposing majority.

To support varying viewpoints, bring diverse voices into the classroom as much as possible, especially when discussing current events. Use primary sources: videos from YouTube, essays and articles written by people who experienced current events firsthand, documentaries that dive deeply into topics that require some nuance, and any other resources that provide a varied look at topics.

I like to use the Smithsonian “OurStory” page , which shares a wide variety of stories from people in the United States. The page on Japanese American internment camps is very powerful because of its first-person perspectives.

Practice Makes Perfect

To make the above strategies and thinking routines a consistent part of your classroom, spread them out—and build upon them—over the course of the school year. You might challenge students with information and/or examples that require them to use their critical thinking skills; work these skills explicitly into lessons, projects, rubrics, and self-assessments; or have students practice identifying misinformation or unsupported arguments.

Critical thinking is not learned in isolation. It needs to be explored in English language arts, social studies, science, physical education, math. Every discipline requires students to take a careful look at something and find the best solution. Often, these skills are taken for granted, viewed as a by-product of a good education, but true critical thinking doesn’t just happen. It requires consistency and commitment.

In a moment when information and misinformation abound, and students must parse reams of information, it is imperative that we support and model critical thinking in the classroom to support the development of well-informed citizens.

Critical Thinking for Teachers

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Diler Oner 3 &

- Yeliz Gunal Aggul 3

Part of the book series: Integrated Science ((IS,volume 13))

994 Accesses

3 Citations

Developing critical thinking is an important educational goal for all grade levels today. To foster their students’ critical thinking, future teachers themselves must become critical thinkers first. Thus, critical thinking should be an essential aspect of teacher training. However, despite its importance, critical thinking is not systematically incorporated into teacher education programs. There exist several conceptualizations of critical thinking in the literature, and these have different entailments regarding the guidelines and instructional strategies to teach critical thinking. In this paper, after examining the critical thinking literature, we suggested that critical thinking could be conceptualized in two distinct but complementary ways—as the acquisition of cognitive skills (instrumental perspective) and as identity development (situated perspective). We discussed the implications of these perspectives in teacher education. While the instrumental perspective allowed us to consider what to teach regarding critical thinking, the situated perspective enabled us to emphasize the broader social context where critical thinking skills and dispositions could be means of active participation in the culture of teaching.

Graphical Abstract/Art Performance

Critical thinking.

Everything we teach should be different from machines. If we do not change the way we teach, 30 years from now, we will be in trouble . Jack Ma

Jack Ma Co-founder of the Alibaba Group.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Teaching Critical Thinking: An Operational Framework

Transformative Critique: What Confucianism Can Contribute to Contemporary Education

Teaching critical thinking for lifelong learning.

Burbules N-C, Berk R (1999) Critical thinking and critical pedagogy: relations, differences, and limits. In: Popkewitz T-S, Fendler L (eds) Critical theories in education. Routledge, New York, pp 45–65

Google Scholar

Hitchcock D (2018) Critical thinking. In: Zalta E-N (ed) The Stanford Encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/critical-thinking . Accessed 8 Aug 2020

Costa A-L (1985) Developing minds: preface to the revised edition. In: Costa A-L (ed) Developing minds: a resource book for teaching thinking. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Virginia, pp ix–x

National Education Association (2012) Preparing 21st-century students for a global society: an educator’s guide to “the four Cs.” http://www.nea.org/assets/docs/A-Guide-to-Four-Cs.pdf . Accessed 08 Aug 2020

Oner D (2019) Education 4.0: the skills needed for the future. In: Paper presented at the 5th Turkish-German frontiers of social science symposium (TUGFOSS) by Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Stiftung Mercator, and Koç University, Leipzig, Germany, 24–27 Oct 2019

Elder L, Paul R (1994) Critical thinking: why we must transform our teaching. J Dev Educ 18(1):34–35

Williams R-L (2005) Targeting critical thinking within teacher education: the potential impact on society. Teach Educ Q 40(3):163–187

Holder J-J (1994) An epistemological foundation for thinking: a Deweyan approach. Stud Philos Educ 13:175–192

Article Google Scholar

Dewey J (1910) How we think. D.C. Heath and Company, Lexington

Bruner J (1966) Toward a theory of instruction. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Laanemets U, Kalamees-Ruubel K (2013) The Taba-Tyler rationales. J Am Assoc Advance Curriculum Stud 9:1–12

McTighe J, Schollenberger J (1985) Why teach thinking? A statement of rationale. In: Costa A-L (ed) Developing minds: a resource book for teaching thinking. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, pp 2–5

Taba H (1962) The teaching of thinking. Element English 42(5):534–542

Pressesien B-Z (1985) Thinking skills: meanings and models revisited. In: Costa A-L (ed) Developing minds: a resource book for teaching thinking Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, pp 56–62

Cohen J (1971) Thinking. Rand McNally, Chicago

Iowa Department of Education (1989) A guide to developing higher-order thinking across the curriculum. Department of Education, Des Moines (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED-306-550)

Jonassen D (1996) Computers as mindtools for schools: engaging critical thinking. Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Ennis R-H (1996) Critical thinking dispositions: their nature and accessibility. Informal Logic 18:165–182

Facione P (1990) Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. California Academic Press, Millbrae

Paul R-W (1985) Goals for a critical thinking curriculum. In: Costa A-L (ed) Developing minds: a resource book for teaching thinking. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, pp 77–84

Ennis R-H (1964) A definition of critical thinking. Read Teach 17(8):599–612

Ennis R-H (1985) Goals for a critical thinking curriculum. In: Costa A-L (ed) Developing minds: a resource book for teaching thinking. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, pp 68–71

Ennis R-H (2015) Critical thinking: a streamlined conception. In: Davies M, Barnett R (eds) The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 31–47

Chapter Google Scholar

Davies M (2015) A model of critical thinking in higher education. In: Paulsen M (ed) Higher education: handbook of theory and research, vol 30. Springer, Cham, pp 41–92

Walters K-S (1994) Introduction: beyond logicism in critical thinking. In: Walters K-S (ed) Re-thinking reason: new perspectives in critical thinking. SUNY Press, Albany, pp 1–22

Barnett R (1997) Higher education: a critical business. Open University Press, Buckingham

Phelan A-M, Garrison J-W (1994) Toward a gender-sensitive ideal of critical thinking: a feminist poetic. Curric Inq 24(3):255–268

Kaplan L-D (1991) Teaching intellectual autonomy: the failure of the critical thinking movement. Educ Theory 41(4):361–370

McLaren P (1994) Critical pedagogy and predatory culture. Routledge, London

Giroux H-A (2010) Lessons from Paulo Freire. https://www.chronicle.com/article/lessons-from-paulo-freire/ . Accessed 8 Aug 2020

Freire P (2000) Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum, New York

Giroux H-A (2011) On critical pedagogy. The Continuum International Publishing Group, Auckland

Volman M, ten Dam G (2015) Critical thinking for educated citizenship. In: Davies M, Barnett R (eds) The Palgrave handbook of critical thinking in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, pp 593–603

Belenky M-F, Clinchy B-M, Goldberger N-R, Tarule J-M (1997) Women’s ways of knowing: the development of self, voice, and mind. Basic Books, New York

Warren K-J (1994) Critical thinking and feminism. In: Walters K-S (ed) Re-thinking reason: new perspectives in critical thinking. SUNY Press, Albany, pp 199–204

Thayer-Bacon B (2000) Transforming critical thinking. Teachers College Press, New York

Atkinson D (1997) A critical approach to critical thinking in TESOL. TESOL Q 31(1):71–94

ten Dam G, Volman M (2004) Critical thinking as a citizenship competence: teaching strategies. Learn Instr 14:359–379

Sfard A (1998) On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educ Res 27:4–13

Tsui L (1999) Courses and instruction affecting critical thinking. Res High Educ 40(2):185–200

Abrami P-C, Bernard R-M, Borokhovski E, Waddington D-I, Anne Wade C, Persson T (2015) Strategies for teaching students to think critically: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 85(2):275–314

Mpofu N, Maphalala M-C (2017) Fostering critical thinking in initial teacher education curriculums: a comprehensive literature review. Gender Behav 15(2):9226–9236

Ennis R-H (1989) Critical thinking and subject specificity: clarification and needed research. Educ Res 18(3):4–10

Norris S-P (1985) The choice of standard conditions in defining critical thinking competence. Educ Theory 35(1):97–107

Paul R-W (1985) McPeck’s mistakes. Informal Logic 7(1):35–43

Siegel H (1991) The generalizability of critical thinking. Educ Philos Theory 23(1):18–30

McPeck J-E (1981) Critical thinking and education. St Martin’s Press, New York

McPeck J-E (1984) Stalking beasts, but swatting flies: the teaching of critical thinking. Can J Educ 9(1):28–44

McPeck J-E (1990) Critical thinking and subject-specificity: a reply to Ennis. Educ Res 19(4):10–12

Adler M (1986) Why critical thinking programs won’t work. Educ Week 6(2):28

Brown A (1997) Transforming schools into communities of thinking and learning about serious matters. Am Psychol 52(4):399–413

Article CAS Google Scholar

Oner D (2010) Öğretmenin bilgisi özel bir bilgi midir? Öğretmek için gereken bilgiye kuramsal bir bakış. Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Eğitim Dergisi 27(2):23–32

Shulman L-S (1987) Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educ Rev 57(1):61–77. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

Oner D, Adadan E (2011) Use of web-based portfolios as tools for reflection in preservice teacher education. J Teach Educ 62(5):477–492

Oner D, Adadan E (2016) Are integrated portfolio systems the answer? An evaluation of a web-based portfolio system to improve preservice teachers’ reflective thinking skills. J Comput High Educ 28(2):236–260

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Brookfield S (2012) Teaching for critical thinking: tools and techniques to help students question their assumptions. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Korthagen F-A-J (2010) Situated learning theory and the pedagogy of teacher education: towards an integrative view of teacher behavior and teacher learning. Teach Teach Educ 26(1):98–106

Putnam R-T, Borko H (2000) What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educ Res 29(1):4–15

Brown J-S, Collins A, Duguid P (1989) Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res 18(1):32–42

Scardamalia M, Bereiter C (1991) Higher levels of agency for children in knowledge building: a challenge for the design of new knowledge media. J Learn Sci 1(1):37–68

Shaffer D-W (2005) Epistemic games. Innovate J Online Educ 1(6):Article 2

Oner D (2020) A virtual internship for developing technological pedagogical content knowledge. Australas J Educ Technol 36(2):27–42

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bogazici University, Istanbul, Turkey

Diler Oner & Yeliz Gunal Aggul

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Diler Oner .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Stockholm, Sweden

Nima Rezaei

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Oner, D., Aggul, Y.G. (2022). Critical Thinking for Teachers. In: Rezaei, N. (eds) Integrated Education and Learning. Integrated Science, vol 13. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15963-3_18

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15963-3_18

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-15962-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-15963-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Call for Volunteers!

- Our Team of Presenters

- Fellows of the Foundation

- Dr. Richard Paul

- Dr. Linda Elder

- Dr. Gerald Nosich

- Contact Us - Office Information

- Permission to Use Our Work

- Create a CriticalThinking.Org Account

- Contributions to the Foundation for Critical Thinking

- Testimonials

- Center for Critical Thinking

- The National Council for Excellence in Critical Thinking

- International Center for the Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

- Library of Critical Thinking Resources

- Professional Development

- Inservice Information Request Form

- Certification Online Course

- The State of Critical Thinking Today

- Higher Education

- K-12 Instruction

- Customized Webinars and Online Courses for Faculty

- Business & Professional Groups

- The Center for Critical Thinking Community Online

- Certification in the Paul-Elder Approach to Critical Thinking

- Professional Development Model - College and University

- Professional Development Model for K-12

- Workshop Descriptions

- Online Courses in Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking Training for Law Enforcement

- Consulting for Leaders and Key Personnel at Your Organization

- Critical Thinking Therapy

- Conferences & Events

- Upcoming Learning Opportunities

- 2024 Fall Academy on Critical Thinking

- Daily Schedule

- Transportation, Lodging, and Social Functions

- Critical Thinking Therapy Release & Book Signing

- Academy Presuppositions

- Save the Date: 45th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Presuppositions of the Conference

- Call for Proposals

- Conference Archives

- 44th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Focal Session Descriptions

- Guest Presentation Program

- Presuppositions of the 44th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Recommended Reading

- 43rd Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Register as an Ambassador

- Testimonials from Past Attendees

- Thank You to Our Donors

- 42nd Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Overview of Sessions (Flyer)

- Presuppositions of the Annual International Conference

- Testimonials from Past Conferences

- 41st Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Recommended Publications

- Dedication to Our Donors

- 40th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Session Descriptions

- Testimonials from Prior Conferences

- International Critical Thinking Manifesto

- Scholarships Available

- 39th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Travel and Lodging Info

- FAQ & General Announcements

- Focal and Plenary Session Descriptions

- Program and Proceedings of the 39th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- The Venue: KU Leuven

- Call for Critical Thinking Ambassadors

- Conference Background Information

- 38th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Call for Ambassadors for Critical Thinking

- Conference Focal Session Descriptions

- Conference Concurrent Session Descriptions

- Conference Roundtable Discussions

- Conference Announcements and FAQ

- Conference Program and Proceedings

- Conference Daily Schedule

- Conference Hotel Information

- Conference Academic Credit

- Conference Presuppositions

- What Participants Have Said About the Conference

- 37th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking

- Registration & Fees

- FAQ and Announcements

- Conference Presenters

- 37th Conference Flyer

- Program and Proceedings of the 37th Conference

- 36th International Conference

- Conference Sessions

- Conference Flyer

- Program and Proceedings

- Academic Credit

- 35th International Conference

- Conference Session Descriptions

- Available Online Sessions

- Bertrand Russell Distinguished Scholar - Daniel Ellsberg

- 35th International Conference Program

- Concurrent Sessions

- Posthumous Bertrand Russell Scholar

- Hotel Information

- Conference FAQs

- Visiting UC Berkeley

- 34th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

- Bertrand Russell Distinguished Scholar - Ralph Nader

- Conference Concurrent Presenters

- Conference Program

- Conference Theme

- Roundtable Discussions

- Flyer for Bulletin Boards

- 33rd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

- 33rd International Conference Program

- 33rd International Conference Sessions

- 33rd International Conference Presenters

- The Bertrand Russell Distinguished Scholars Critical Thinking Conversations

- 33rd International Conference - Fees & Registration

- 33rd International Conference Concurrent Presenters

- 33rd International Conference - Hotel Information

- 33rd International Conference Flyer

- 32nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

- 32nd Annual Conference Sessions

- 32nd Annual Conference Presenter Information

- 32nd Conference Program

- The Bertrand Russell Distinguished Scholars Critical Thinking Lecture Series

- 32nd Annual Conference Concurrent Presenters

- 32nd Annual Conference Academic Credit

- 31st INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE

- 31st Conference Sessions

- Comments about previous conferences

- Conference Hotel (2011)

- 31st Concurrent Presenters

- Registration Fees

- 31st International Conference

- 30th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CRITICAL THINKING

- 30th International Conference Theme

- 30th Conference Sessions

- PreConference Sessions

- 30th Concurrent Presenters

- 30th Conference Presuppositions

- Hilton Garden Inn

- 29th International Conference

- 29th Conference Theme

- 29th Conference Sessions

- 29th Preconference Sessions

- 29th Conference Concurrent Sessions

- 2008 International Conference on Critical Thinking

- 2008 Preconference Sessions (28th Intl. Conference)

- 2007 Conference on Critical Thinking (Main Page)

- 2007 Conference Theme and sessions

- 2007 Pre-Conference Workshops

- 2006 Annual International Conference (archived)

- 2006 International Conference Theme

- 2005 International Conference (archived)

- Prior Conference Programs (Pre 2000)

- Workshop Archives

- Spring 2022 Online Workshops

- 2021 Online Workshops for Winter & Spring

- 2019 Seminar for Military and Intelligence Trainers and Instructors

- Transportation, Lodging, and Recreation

- Seminar Flyer

- 2013 Spring Workshops

- Our Presenters

- 2013 Spring Workshops - Hotel Information

- 2013 Spring Workshops Flyer

- 2013 Spring Workshops - Schedule

- Spring Workshop 2012

- 2012 Spring Workshop Strands

- 2012 Spring Workshop Flier

- 2011 Spring Workshop

- Spring 2010 Workshop Strands

- 2009 Spring Workshops on Critical Thinking

- 2008 SPRING Workshops and Seminars on Critical Thinking

- 2008 Ethical Reasoning Workshop

- 2008 - On Richard Paul's Teaching Design

- 2008 Engineering Reasoning Workshop

- 2008 Academia sobre Formulando Preguntas Esenciales

- Fellows Academy Archives

- 2017 Fall International Fellows Academy

- 4th International Fellows Academy - 2016

- 3rd International Fellows Academy

- 2nd International Fellows Academy

- 1st International Fellows Academy

- Academy Archives

- October 2019 Critical Thinking Academy for Educators and Administrators

- Transportation, Lodging, and Leisure

- Advanced Seminar: Oxford Tutorial

- Recreational Group Activities

- Limited Scholarships Available

- September 2019 Critical Thinking Educators and Administrators Academy

- 2019 Critical Thinking Training for Trainers and Advanced Academy

- Academy Flyer

- Seattle, WA 2017 Spring Academy

- San Diego, CA 2017 Spring Academy

- 2016 Spring Academy -- Washington D.C.

- 2016 Spring Academy -- Houston, TX

- The 2nd International Academy on Critical Thinking (Oxford 2008)

- 2007 National Academy on Critical Thinking Testing and Assessment

- 2006 Cambridge Academy (archived)

- 2006 Cambridge Academy Theme

- 2006 Cambridge Academy Sessions

- Accommodations at St. John's College

- Assessment & Testing

- A Model for the National Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

- International Critical Thinking Essay Test

- Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Test

- Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Sample Test

- Consequential Validity: Using Assessment to Drive Instruction

- News & Announcements

- Newest Pages Added to CriticalThinking.Org

- Online Learning

- Critical Thinking Online Courses

- Critical Thinking Blog

- 2019 Blog Entries

- 2020 Blog Entries

- 2021 Blog Entries

- 2022 Blog Entries

- 2023 Blog Entries

- Online Courses for Your Students

- 2023 Webinar Archives

- 2022 Webinar Archives

- 2021 Webinar Archive

- 2020 Webinar Archive

- Guided Study Groups

- Critical Thinking Channel on YouTube

- CT800: Fall 2024

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Critical Thinking: Where to Begin

- For College and University Faculty

- For College and University Students

- For High School Teachers

- For Jr. High School Teachers

- For Elementary Teachers (Grades 4-6)

- For Elementary Teachers (Kindergarten - 3rd Grade)

- For Science and Engineering Instruction

- For Business and Professional Development

- For Nursing and Health Care

- For Home Schooling and Home Study

If you are new to critical thinking or wish to deepen your conception of it, we recommend you review the content below and bookmark this page for future reference.

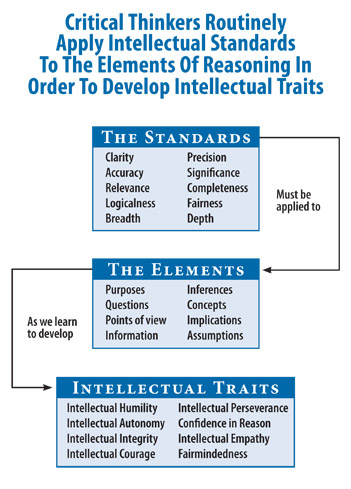

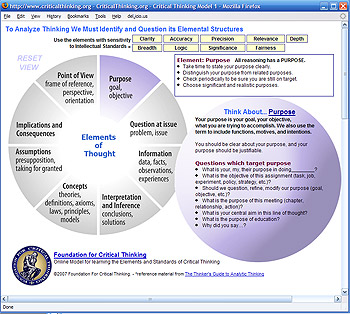

Our Conception of Critical Thinking...

"Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness..."

"Critical thinking is self-guided, self-disciplined thinking which attempts to reason at the highest level of quality in a fairminded way. People who think critically attempt, with consistent and conscious effort, to live rationally, reasonably, and empathically. They are keenly aware of the inherently flawed nature of human thinking when left unchecked. They strive to diminish the power of their egocentric and sociocentric tendencies. They use the intellectual tools that critical thinking offers – concepts and principles that enable them to analyze, assess, and improve thinking. They work diligently to develop the intellectual virtues of intellectual integrity, intellectual humility, intellectual civility, intellectual empathy, intellectual sense of justice and confidence in reason. They realize that no matter how skilled they are as thinkers, they can always improve their reasoning abilities and they will at times fall prey to mistakes in reasoning, human irrationality, prejudices, biases, distortions, uncritically accepted social rules and taboos, self-interest, and vested interest.

They strive to improve the world in whatever ways they can and contribute to a more rational, civilized society. At the same time, they recognize the complexities often inherent in doing so. They strive never to think simplistically about complicated issues and always to consider the rights and needs of relevant others. They recognize the complexities in developing as thinkers, and commit themselves to life-long practice toward self-improvement. They embody the Socratic principle: The unexamined life is not worth living , because they realize that many unexamined lives together result in an uncritical, unjust, dangerous world."

Why Critical Thinking?

The Problem:

Everyone thinks; it is our nature to do so. But much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed, or down-right prejudiced. Yet the quality of our lives and that of what we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought. Shoddy thinking is costly, both in money and in quality of life. Excellence in thought, however, must be systematically cultivated.

A Brief Definition:

Critical thinking is the art of analyzing and evaluating thinking with a view to improving it. The Result:

A well-cultivated critical thinker:

- raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively;

- comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;