- Privacy Policy

Home » Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Table of Contents

Evaluating Research

Definition:

Evaluating Research refers to the process of assessing the quality, credibility, and relevance of a research study or project. This involves examining the methods, data, and results of the research in order to determine its validity, reliability, and usefulness. Evaluating research can be done by both experts and non-experts in the field, and involves critical thinking, analysis, and interpretation of the research findings.

Research Evaluating Process

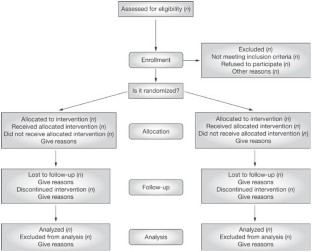

The process of evaluating research typically involves the following steps:

Identify the Research Question

The first step in evaluating research is to identify the research question or problem that the study is addressing. This will help you to determine whether the study is relevant to your needs.

Assess the Study Design

The study design refers to the methodology used to conduct the research. You should assess whether the study design is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce reliable and valid results.

Evaluate the Sample

The sample refers to the group of participants or subjects who are included in the study. You should evaluate whether the sample size is adequate and whether the participants are representative of the population under study.

Review the Data Collection Methods

You should review the data collection methods used in the study to ensure that they are valid and reliable. This includes assessing the measures used to collect data and the procedures used to collect data.

Examine the Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis refers to the methods used to analyze the data. You should examine whether the statistical analysis is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce valid and reliable results.

Assess the Conclusions

You should evaluate whether the data support the conclusions drawn from the study and whether they are relevant to the research question.

Consider the Limitations

Finally, you should consider the limitations of the study, including any potential biases or confounding factors that may have influenced the results.

Evaluating Research Methods

Evaluating Research Methods are as follows:

- Peer review: Peer review is a process where experts in the field review a study before it is published. This helps ensure that the study is accurate, valid, and relevant to the field.

- Critical appraisal : Critical appraisal involves systematically evaluating a study based on specific criteria. This helps assess the quality of the study and the reliability of the findings.

- Replication : Replication involves repeating a study to test the validity and reliability of the findings. This can help identify any errors or biases in the original study.

- Meta-analysis : Meta-analysis is a statistical method that combines the results of multiple studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic. This can help identify patterns or inconsistencies across studies.

- Consultation with experts : Consulting with experts in the field can provide valuable insights into the quality and relevance of a study. Experts can also help identify potential limitations or biases in the study.

- Review of funding sources: Examining the funding sources of a study can help identify any potential conflicts of interest or biases that may have influenced the study design or interpretation of results.

Example of Evaluating Research

Example of Evaluating Research sample for students:

Title of the Study: The Effects of Social Media Use on Mental Health among College Students

Sample Size: 500 college students

Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling

- Sample Size: The sample size of 500 college students is a moderate sample size, which could be considered representative of the college student population. However, it would be more representative if the sample size was larger, or if a random sampling technique was used.

- Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling technique, which means that the sample may not be representative of the population. This technique may introduce bias into the study since the participants are self-selected and may not be representative of the entire college student population. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Participant Characteristics: The study does not provide any information about the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status. This information is important because social media use and mental health may vary among different demographic groups.

- Data Collection Method: The study used a self-administered survey to collect data. Self-administered surveys may be subject to response bias and may not accurately reflect participants’ actual behaviors and experiences.

- Data Analysis: The study used descriptive statistics and regression analysis to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics provide a summary of the data, while regression analysis is used to examine the relationship between two or more variables. However, the study did not provide information about the statistical significance of the results or the effect sizes.

Overall, while the study provides some insights into the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students, the use of a convenience sampling technique and the lack of information about participant characteristics limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the use of self-administered surveys may introduce bias into the study, and the lack of information about the statistical significance of the results limits the interpretation of the findings.

Note*: Above mentioned example is just a sample for students. Do not copy and paste directly into your assignment. Kindly do your own research for academic purposes.

Applications of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the applications of evaluating research:

- Identifying reliable sources : By evaluating research, researchers, students, and other professionals can identify the most reliable sources of information to use in their work. They can determine the quality of research studies, including the methodology, sample size, data analysis, and conclusions.

- Validating findings: Evaluating research can help to validate findings from previous studies. By examining the methodology and results of a study, researchers can determine if the findings are reliable and if they can be used to inform future research.

- Identifying knowledge gaps: Evaluating research can also help to identify gaps in current knowledge. By examining the existing literature on a topic, researchers can determine areas where more research is needed, and they can design studies to address these gaps.

- Improving research quality : Evaluating research can help to improve the quality of future research. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies, researchers can design better studies and avoid common pitfalls.

- Informing policy and decision-making : Evaluating research is crucial in informing policy and decision-making in many fields. By examining the evidence base for a particular issue, policymakers can make informed decisions that are supported by the best available evidence.

- Enhancing education : Evaluating research is essential in enhancing education. Educators can use research findings to improve teaching methods, curriculum development, and student outcomes.

Purpose of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the key purposes of evaluating research:

- Determine the reliability and validity of research findings : By evaluating research, researchers can determine the quality of the study design, data collection, and analysis. They can determine whether the findings are reliable, valid, and generalizable to other populations.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies: Evaluating research helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies, including potential biases, confounding factors, and limitations. This information can help researchers to design better studies in the future.

- Inform evidence-based decision-making: Evaluating research is crucial in informing evidence-based decision-making in many fields, including healthcare, education, and public policy. Policymakers, educators, and clinicians rely on research evidence to make informed decisions.

- Identify research gaps : By evaluating research, researchers can identify gaps in the existing literature and design studies to address these gaps. This process can help to advance knowledge and improve the quality of research in a particular field.

- Ensure research ethics and integrity : Evaluating research helps to ensure that research studies are conducted ethically and with integrity. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines to protect the welfare and rights of study participants and to maintain the trust of the public.

Characteristics Evaluating Research

Characteristics Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Research question/hypothesis: A good research question or hypothesis should be clear, concise, and well-defined. It should address a significant problem or issue in the field and be grounded in relevant theory or prior research.

- Study design: The research design should be appropriate for answering the research question and be clearly described in the study. The study design should also minimize bias and confounding variables.

- Sampling : The sample should be representative of the population of interest and the sampling method should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Data collection : The data collection methods should be reliable and valid, and the data should be accurately recorded and analyzed.

- Results : The results should be presented clearly and accurately, and the statistical analysis should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Interpretation of results : The interpretation of the results should be based on the data and not influenced by personal biases or preconceptions.

- Generalizability: The study findings should be generalizable to the population of interest and relevant to other settings or contexts.

- Contribution to the field : The study should make a significant contribution to the field and advance our understanding of the research question or issue.

Advantages of Evaluating Research

Evaluating research has several advantages, including:

- Ensuring accuracy and validity : By evaluating research, we can ensure that the research is accurate, valid, and reliable. This ensures that the findings are trustworthy and can be used to inform decision-making.

- Identifying gaps in knowledge : Evaluating research can help identify gaps in knowledge and areas where further research is needed. This can guide future research and help build a stronger evidence base.

- Promoting critical thinking: Evaluating research requires critical thinking skills, which can be applied in other areas of life. By evaluating research, individuals can develop their critical thinking skills and become more discerning consumers of information.

- Improving the quality of research : Evaluating research can help improve the quality of research by identifying areas where improvements can be made. This can lead to more rigorous research methods and better-quality research.

- Informing decision-making: By evaluating research, we can make informed decisions based on the evidence. This is particularly important in fields such as medicine and public health, where decisions can have significant consequences.

- Advancing the field : Evaluating research can help advance the field by identifying new research questions and areas of inquiry. This can lead to the development of new theories and the refinement of existing ones.

Limitations of Evaluating Research

Limitations of Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Evaluating research can be time-consuming, particularly if the study is complex or requires specialized knowledge. This can be a barrier for individuals who are not experts in the field or who have limited time.

- Subjectivity : Evaluating research can be subjective, as different individuals may have different interpretations of the same study. This can lead to inconsistencies in the evaluation process and make it difficult to compare studies.

- Limited generalizability: The findings of a study may not be generalizable to other populations or contexts. This limits the usefulness of the study and may make it difficult to apply the findings to other settings.

- Publication bias: Research that does not find significant results may be less likely to be published, which can create a bias in the published literature. This can limit the amount of information available for evaluation.

- Lack of transparency: Some studies may not provide enough detail about their methods or results, making it difficult to evaluate their quality or validity.

- Funding bias : Research funded by particular organizations or industries may be biased towards the interests of the funder. This can influence the study design, methods, and interpretation of results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Research Project – Definition, Writing Guide and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

Purpose of Research – Objectives and Applications

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

1 Important points to consider when critically evaluating published research papers

Simple review articles (also referred to as ‘narrative’ or ‘selective’ reviews), systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide rapid overviews and ‘snapshots’ of progress made within a field, summarising a given topic or research area. They can serve as useful guides, or as current and comprehensive ‘sources’ of information, and can act as a point of reference to relevant primary research studies within a given scientific area. Narrative or systematic reviews are often used as a first step towards a more detailed investigation of a topic or a specific enquiry (a hypothesis or research question), or to establish critical awareness of a rapidly-moving field (you will be required to demonstrate this as part of an assignment, an essay or a dissertation at postgraduate level).

The majority of primary ‘empirical’ research papers essentially follow the same structure (abbreviated here as IMRAD). There is a section on Introduction, followed by the Methods, then the Results, which includes figures and tables showing data described in the paper, and a Discussion. The paper typically ends with a Conclusion, and References and Acknowledgements sections.

The Title of the paper provides a concise first impression. The Abstract follows the basic structure of the extended article. It provides an ‘accessible’ and concise summary of the aims, methods, results and conclusions. The Introduction provides useful background information and context, and typically outlines the aims and objectives of the study. The Abstract can serve as a useful summary of the paper, presenting the purpose, scope and major findings. However, simply reading the abstract alone is not a substitute for critically reading the whole article. To really get a good understanding and to be able to critically evaluate a research study, it is necessary to read on.

While most research papers follow the above format, variations do exist. For example, the results and discussion sections may be combined. In some journals the materials and methods may follow the discussion, and in two of the most widely read journals, Science and Nature, the format does vary from the above due to restrictions on the length of articles. In addition, there may be supporting documents that accompany a paper, including supplementary materials such as supporting data, tables, figures, videos and so on. There may also be commentaries or editorials associated with a topical research paper, which provide an overview or critique of the study being presented.

Box 1 Key questions to ask when appraising a research paper

- Is the study’s research question relevant?

- Does the study add anything new to current knowledge and understanding?

- Does the study test a stated hypothesis?

- Is the design of the study appropriate to the research question?

- Do the study methods address key potential sources of bias?

- Were suitable ‘controls’ included in the study?

- Were the statistical analyses appropriate and applied correctly?

- Is there a clear statement of findings?

- Does the data support the authors’ conclusions?

- Are there any conflicts of interest or ethical concerns?

There are various strategies used in reading a scientific research paper, and one of these is to start with the title and the abstract, then look at the figures and tables, and move on to the introduction, before turning to the results and discussion, and finally, interrogating the methods.

Another strategy (outlined below) is to begin with the abstract and then the discussion, take a look at the methods, and then the results section (including any relevant tables and figures), before moving on to look more closely at the discussion and, finally, the conclusion. You should choose a strategy that works best for you. However, asking the ‘right’ questions is a central feature of critical appraisal, as with any enquiry, so where should you begin? Here are some critical questions to consider when evaluating a research paper.

Look at the Abstract and then the Discussion : Are these accessible and of general relevance or are they detailed, with far-reaching conclusions? Is it clear why the study was undertaken? Why are the conclusions important? Does the study add anything new to current knowledge and understanding? The reasons why a particular study design or statistical method were chosen should also be clear from reading a research paper. What is the research question being asked? Does the study test a stated hypothesis? Is the design of the study appropriate to the research question? Have the authors considered the limitations of their study and have they discussed these in context?

Take a look at the Methods : Were there any practical difficulties that could have compromised the study or its implementation? Were these considered in the protocol? Were there any missing values and, if so, was the number of missing values too large to permit meaningful analysis? Was the number of samples (cases or participants) too small to establish meaningful significance? Do the study methods address key potential sources of bias? Were suitable ‘controls’ included in the study? If controls are missing or not appropriate to the study design, we cannot be confident that the results really show what is happening in an experiment. Were the statistical analyses appropriate and applied correctly? Do the authors point out the limitations of methods or tests used? Were the methods referenced and described in sufficient detail for others to repeat or extend the study?

Take a look at the Results section and relevant tables and figures : Is there a clear statement of findings? Were the results expected? Do they make sense? What data supports them? Do the tables and figures clearly describe the data (highlighting trends etc.)? Try to distinguish between what the data show and what the authors say they show (i.e. their interpretation).

Moving on to look in greater depth at the Discussion and Conclusion : Are the results discussed in relation to similar (previous) studies? Do the authors indulge in excessive speculation? Are limitations of the study adequately addressed? Were the objectives of the study met and the hypothesis supported or refuted (and is a clear explanation provided)? Does the data support the authors’ conclusions? Maybe there is only one experiment to support a point. More often, several different experiments or approaches combine to support a particular conclusion. A rule of thumb here is that if multiple approaches and multiple lines of evidence from different directions are presented, and all point to the same conclusion, then the conclusions are more credible. But do question all assumptions. Identify any implicit or hidden assumptions that the authors may have used when interpreting their data. Be wary of data that is mixed up with interpretation and speculation! Remember, just because it is published, does not mean that it is right.

O ther points you should consider when evaluating a research paper : Are there any financial, ethical or other conflicts of interest associated with the study, its authors and sponsors? Are there ethical concerns with the study itself? Looking at the references, consider if the authors have preferentially cited their own previous publications (i.e. needlessly), and whether the list of references are recent (ensuring that the analysis is up-to-date). Finally, from a practical perspective, you should move beyond the text of a research paper, talk to your peers about it, consult available commentaries, online links to references and other external sources to help clarify any aspects you don’t understand.

The above can be taken as a general guide to help you begin to critically evaluate a scientific research paper, but only in the broadest sense. Do bear in mind that the way that research evidence is critiqued will also differ slightly according to the type of study being appraised, whether observational or experimental, and each study will have additional aspects that would need to be evaluated separately. For criteria recommended for the evaluation of qualitative research papers, see the article by Mildred Blaxter (1996), available online. Details are in the References.

Activity 1 Critical appraisal of a scientific research paper

A critical appraisal checklist, which you can download via the link below, can act as a useful tool to help you to interrogate research papers. The checklist is divided into four sections, broadly covering:

- some general aspects

- research design and methodology

- the results

- discussion, conclusion and references.

Science perspective – critical appraisal checklist [ Tip: hold Ctrl and click a link to open it in a new tab. ( Hide tip ) ]

- Identify and obtain a research article based on a topic of your own choosing, using a search engine such as Google Scholar or PubMed (for example).

- The selection criteria for your target paper are as follows: the article must be an open access primary research paper (not a review) containing empirical data, published in the last 2–3 years, and preferably no more than 5–6 pages in length.

- Critically evaluate the research paper using the checklist provided, making notes on the key points and your overall impression.

Critical appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess the quality of a study. Assessment of various factors, including the importance of the research question, the design and methodology of a study, the validity of the results and their usefulness (application or relevance), the legitimacy of the conclusions, and any potential conflicts of interest, are an important part of the critical appraisal process. Limitations and further improvements can then be considered.

Evaluating Research Articles

Understanding research statistics, critical appraisal, help us improve the libguide.

Imagine for a moment that you are trying to answer a clinical (PICO) question regarding one of your patients/clients. Do you know how to determine if a research study is of high quality? Can you tell if it is applicable to your question? In evidence based practice, there are many things to look for in an article that will reveal its quality and relevance. This guide is a collection of resources and activities that will help you learn how to evaluate articles efficiently and accurately.

Is health research new to you? Or perhaps you're a little out of practice with reading it? The following questions will help illuminate an article's strengths or shortcomings. Ask them of yourself as you are reading an article:

- Is the article peer reviewed?

- Are there any conflicts of interest based on the author's affiliation or the funding source of the research?

- Are the research questions or objectives clearly defined?

- Is the study a systematic review or meta analysis?

- Is the study design appropriate for the research question?

- Is the sample size justified? Do the authors explain how it is representative of the wider population?

- Do the researchers describe the setting of data collection?

- Does the paper clearly describe the measurements used?

- Did the researchers use appropriate statistical measures?

- Are the research questions or objectives answered?

- Did the researchers account for confounding factors?

- Have the researchers only drawn conclusions about the groups represented in the research?

- Have the authors declared any conflicts of interest?

If the answer to these questions about an article you are reading are mostly YESes , then it's likely that the article is of decent quality. If the answers are most NOs , then it may be a good idea to move on to another article. If the YESes and NOs are roughly even, you'll have to decide for yourself if the article is good enough quality for you. Some factors, like a poor literature review, are not as important as the researchers neglecting to describe the measurements they used. As you read more research, you'll be able to more easily identify research that is well done vs. that which is not well done.

Determining if a research study has used appropriate statistical measures is one of the most critical and difficult steps in evaluating an article. The following links are great, quick resources for helping to better understand how to use statistics in health research.

- How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: “Significant” relations and their pitfalls This article continues the checklist of questions that will help you to appraise the statistical validity of a paper. Greenhalgh Trisha. How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: “Significant” relations and their pitfalls BMJ 1997; 315 :422 *On the PMC PDF, you need to scroll past the first article to get to this one.*

- A consumer's guide to subgroup analysis The extent to which a clinician should believe and act on the results of subgroup analyses of data from randomized trials or meta-analyses is controversial. Guidelines are provided in this paper for making these decisions.

Statistical Versus Clinical Significance

When appraising studies, it's important to consider both the clinical and statistical significance of the research. This video offers a quick explanation of why.

If you have a little more time, this video explores statistical and clinical significance in more detail, including examples of how to calculate an effect size.

- Statistical vs. Clinical Significance Transcript Transcript document for the Statistical vs. Clinical Significance video.

- Effect Size Transcript Transcript document for the Effect Size video.

- P Values, Statistical Significance & Clinical Significance This handout also explains clinical and statistical significance.

- Absolute versus relative risk – making sense of media stories Understanding the difference between relative and absolute risk is essential to understanding statistical tests commonly found in research articles.

Critical appraisal is the process of systematically evaluating research using established and transparent methods. In critical appraisal, health professionals use validated checklists/worksheets as tools to guide their assessment of the research. It is a more advanced way of evaluating research than the more basic method explained above. To learn more about critical appraisal or to access critical appraisal tools, visit the websites below.

- Last Updated: Jun 11, 2024 10:26 AM

- URL: https://libguides.massgeneral.org/evaluatingarticles

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Critical Evaluation

Authority: Critical Evaluation

- World Views and Voices

- Understanding Peer Review

Critical Evaluation of Information Sources

After initial evaluation of a source, the next step is to go deeper. This includes a wide variety of techniques and may depend on the type of source. In the case of research, it will include evaluating the methodology used in the study and requires you to have knowledge of those discipline-specific methods. If you are just beginning your academic career or just entered a new field, you will likely need to learn more about the methodologies used in order to fully understand and evaluate this part of a study.

Lateral reading is a technique that can, and should, be applied to any source type. In the case of a research study, looking for the older articles that influenced the one you selected can give you a better understanding of the issues and context. Reading articles that were published after can give you an idea of how scholars are pushing that research to the next step. This can also help with understanding how scholars engage with each other in conversation through research and even how the academic system privileges certain voices and established authorities in the conversation. You might find articles that respond directly to studies that provide insight into evaluation and critique within that discipline.

Evaluation at this level is central to developing a better understanding of your own research question by learning from these scholarly conversations and how authority is tested.

Check out the resources below to help you with this stage of evaluation.

Scientific Method/Methodologies

Here is a general overview of how the scientific method works and how scholars evaluate their work using critical thinking. This same process is used when scholars write up their scholarly work.

The Steps of the Scientific Method

Question something that was observed, do background research to better understand, formulate a hypothesis (research question), create an experiment or method for studying the question, run the experiment and record the results, think critically about what the results mean, suggest conclusions and report back, lateral reading.

Critical Thinking

Thinking critically about the information you encounter is central to how you develop your own conclusions, judgement, and position. This analysis is what will allow you to make a valuable contribution of your own to the scholarly conversation.

- TEDEd: Dig Deeper on the 5 Tips to Improve Your Critical Thinking

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking: College and University Students

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Critical Thinking

Scholarship as Conversation

It sounds pretty bad if you say an article was retracted, but is it always? As with most things, it depends on the context. Someone retracting a statement made based on false information or misinformation is one thing. It happens fairly often in the case of social media--removed tweets or Instagram posts for example.

In scholarship, there are a number of reasons an article might be retracted. These range from errors in the methods used, experiment structure, data, etc. to issues of fraud or misrepresentation. Central to scholarship is the community of scholars actively participating in the scholarly conversation even after the peer review process. Careful analysis of published research by other scholars is vital to course correction.

In science research, it's a central part of the process ! An inherent part of discovery is basing conclusions on the information at hand and repeating the process to gather more information. If further research is done that provides new information and insight, that might mean an older conclusion gets corrected. Uncertainty is unsettling, but trust in the process means understanding the important role of retraction.

- << Previous: Evaluation

- Next: Resources >>

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 20 January 2009

How to critically appraise an article

- Jane M Young 1 &

- Michael J Solomon 2

Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology volume 6 , pages 82–91 ( 2009 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

99 Citations

448 Altmetric

Metrics details

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article in order to assess the usefulness and validity of research findings. The most important components of a critical appraisal are an evaluation of the appropriateness of the study design for the research question and a careful assessment of the key methodological features of this design. Other factors that also should be considered include the suitability of the statistical methods used and their subsequent interpretation, potential conflicts of interest and the relevance of the research to one's own practice. This Review presents a 10-step guide to critical appraisal that aims to assist clinicians to identify the most relevant high-quality studies available to guide their clinical practice.

Critical appraisal is a systematic process used to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a research article

Critical appraisal provides a basis for decisions on whether to use the results of a study in clinical practice

Different study designs are prone to various sources of systematic bias

Design-specific, critical-appraisal checklists are useful tools to help assess study quality

Assessments of other factors, including the importance of the research question, the appropriateness of statistical analysis, the legitimacy of conclusions and potential conflicts of interest are an important part of the critical appraisal process

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Making sense of the literature: an introduction to critical appraisal for the primary care practitioner

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 2: systematic reviews and meta-analyses

How to appraise the literature: basic principles for the busy clinician - part 1: randomised controlled trials

Druss BG and Marcus SC (2005) Growth and decentralisation of the medical literature: implications for evidence-based medicine. J Med Libr Assoc 93 : 499–501

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glasziou PP (2008) Information overload: what's behind it, what's beyond it? Med J Aust 189 : 84–85

PubMed Google Scholar

Last JE (Ed.; 2001) A Dictionary of Epidemiology (4th Edn). New York: Oxford University Press

Google Scholar

Sackett DL et al . (2000). Evidence-based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM . London: Churchill Livingstone

Guyatt G and Rennie D (Eds; 2002). Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: a Manual for Evidence-based Clinical Practice . Chicago: American Medical Association

Greenhalgh T (2000) How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-based Medicine . London: Blackwell Medicine Books

MacAuley D (1994) READER: an acronym to aid critical reading by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 44 : 83–85

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hill A and Spittlehouse C (2001) What is critical appraisal. Evidence-based Medicine 3 : 1–8 [ http://www.evidence-based-medicine.co.uk ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Public Health Resource Unit (2008) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Pages/PHD/CASP.htm ] (accessed 8 August 2008)

National Health and Medical Research Council (2000) How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature . Canberra: NHMRC

Elwood JM (1998) Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials (2nd Edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2002) Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence? Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 47, Publication No 02-E019 Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Crombie IK (1996) The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: a Handbook for Health Care Professionals . London: Blackwell Medicine Publishing Group

Heller RF et al . (2008) Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health 122 : 92–98

Article Google Scholar

MacAuley D et al . (1998) Randomised controlled trial of the READER method of critical appraisal in general practice. BMJ 316 : 1134–37

Article CAS Google Scholar

Parkes J et al . Teaching critical appraisal skills in health care settings (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 3. Art. No.: cd001270. 10.1002/14651858.cd001270

Mays N and Pope C (2000) Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ 320 : 50–52

Hawking SW (2003) On the Shoulders of Giants: the Great Works of Physics and Astronomy . Philadelphia, PN: Penguin

National Health and Medical Research Council (1999) A Guide to the Development, Implementation and Evaluation of Clinical Practice Guidelines . Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

US Preventive Services Taskforce (1996) Guide to clinical preventive services (2nd Edn). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

Solomon MJ and McLeod RS (1995) Should we be performing more randomized controlled trials evaluating surgical operations? Surgery 118 : 456–467

Rothman KJ (2002) Epidemiology: an Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: sources of bias in surgical studies. ANZ J Surg 73 : 504–506

Margitic SE et al . (1995) Lessons learned from a prospective meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 43 : 435–439

Shea B et al . (2001) Assessing the quality of reports of systematic reviews: the QUORUM statement compared to other tools. In Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context 2nd Edition, 122–139 (Eds Egger M. et al .) London: BMJ Books

Chapter Google Scholar

Easterbrook PH et al . (1991) Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 337 : 867–872

Begg CB and Berlin JA (1989) Publication bias and dissemination of clinical research. J Natl Cancer Inst 81 : 107–115

Moher D et al . (2000) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Br J Surg 87 : 1448–1454

Shea BJ et al . (2007) Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 7 : 10 [10.1186/1471-2288-7-10]

Stroup DF et al . (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283 : 2008–2012

Young JM and Solomon MJ (2003) Improving the evidence-base in surgery: evaluating surgical effectiveness. ANZ J Surg 73 : 507–510

Schulz KF (1995) Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 274 : 1456–1458

Schulz KF et al . (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273 : 408–412

Moher D et al . (2001) The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology 1 : 2 [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/ 1471-2288/1/2 ] (accessed 25 November 2008)

Rochon PA et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ 330 : 895–897

Mamdani M et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 330 : 960–962

Normand S et al . (2005) Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ 330 : 1021–1023

von Elm E et al . (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335 : 806–808

Sutton-Tyrrell K (1991) Assessing bias in case-control studies: proper selection of cases and controls. Stroke 22 : 938–942

Knottnerus J (2003) Assessment of the accuracy of diagnostic tests: the cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 56 : 1118–1128

Furukawa TA and Guyatt GH (2006) Sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies and the diagnostic process. CMAJ 174 : 481–482

Bossyut PM et al . (2003)The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 138 : W1–W12

STARD statement (Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies). [ http://www.stard-statement.org/ ] (accessed 10 September 2008)

Raftery J (1998) Economic evaluation: an introduction. BMJ 316 : 1013–1014

Palmer S et al . (1999) Economics notes: types of economic evaluation. BMJ 318 : 1349

Russ S et al . (1999) Barriers to participation in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 52 : 1143–1156

Tinmouth JM et al . (2004) Are claims of equivalency in digestive diseases trials supported by the evidence? Gastroentrology 126 : 1700–1710

Kaul S and Diamond GA (2006) Good enough: a primer on the analysis and interpretation of noninferiority trials. Ann Intern Med 145 : 62–69

Piaggio G et al . (2006) Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 295 : 1152–1160

Heritier SR et al . (2007) Inclusion of patients in clinical trial analysis: the intention to treat principle. In Interpreting and Reporting Clinical Trials: a Guide to the CONSORT Statement and the Principles of Randomized Controlled Trials , 92–98 (Eds Keech A. et al .) Strawberry Hills, NSW: Australian Medical Publishing Company

National Health and Medical Research Council (2007) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 89–90 Canberra: NHMRC

Lo B et al . (2000) Conflict-of-interest policies for investigators in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 343 : 1616–1620

Kim SYH et al . (2004) Potential research participants' views regarding researcher and institutional financial conflicts of interests. J Med Ethics 30 : 73–79

Komesaroff PA and Kerridge IH (2002) Ethical issues concerning the relationships between medical practitioners and the pharmaceutical industry. Med J Aust 176 : 118–121

Little M (1999) Research, ethics and conflicts of interest. J Med Ethics 25 : 259–262

Lemmens T and Singer PA (1998) Bioethics for clinicians: 17. Conflict of interest in research, education and patient care. CMAJ 159 : 960–965

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JM Young is an Associate Professor of Public Health and the Executive Director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney,

Jane M Young

MJ Solomon is Head of the Surgical Outcomes Research Centre and Director of Colorectal Research at the University of Sydney and Sydney South-West Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.,

Michael J Solomon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane M Young .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Young, J., Solomon, M. How to critically appraise an article. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 6 , 82–91 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Download citation

Received : 10 August 2008

Accepted : 03 November 2008

Published : 20 January 2009

Issue Date : February 2009

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep1331

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Emergency physicians’ perceptions of critical appraisal skills: a qualitative study.

- Sumintra Wood

- Jacqueline Paulis

- Angela Chen

BMC Medical Education (2022)

An integrative review on individual determinants of enrolment in National Health Insurance Scheme among older adults in Ghana

- Anthony Kwame Morgan

- Anthony Acquah Mensah

BMC Primary Care (2022)

Autopsy findings of COVID-19 in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Anju Khairwa

- Kana Ram Jat

Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology (2022)

The use of a modified Delphi technique to develop a critical appraisal tool for clinical pharmacokinetic studies

- Alaa Bahaa Eldeen Soliman

- Shane Ashley Pawluk

- Ousama Rachid

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

Critical Appraisal: Analysis of a Prospective Comparative Study Published in IJS

- Ramakrishna Ramakrishna HK

- Swarnalatha MC

Indian Journal of Surgery (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

Critically analyze and evaluate

Tip: read and annotate pdfs.

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write a Literature Review

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- What is the research question?

- What is the primary methodology used?

- How was the data gathered?

- How is the data presented?

- What are the main conclusions?

- Are these conclusions reasonable?

- What theories are used to support the researcher's conclusions?

Take notes on the articles as you read them and identify any themes or concepts that may apply to your research question.

This sample template (below) may also be useful for critically reading and organizing your articles. Or you can use this online form and email yourself a copy .

- Sample Template for Critical Analysis of the Literature

Opening an article in PDF format in Acrobat Reader will allow you to use "sticky notes" and "highlighting" to make notes on the article without printing it out. Make sure to save the edited file so you don't lose your notes!

Some Citation Managers like Mendeley also have highlighting and annotation features.Here's a screen capture of a pdf in Mendeley with highlighting, notes, and various colors:

Screen capture from a UO Librarian's Mendeley Desktop app

- Learn more about citation management software in the previous step: 4. Manage Your References

- << Previous: 4. Manage Your References

- Next: 6. Synthesize >>

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 11:48 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Critically appraising...

Critically appraising qualitative research

- Related content

- Peer review

- Ayelet Kuper , assistant professor 1 ,

- Lorelei Lingard , associate professor 2 ,

- Wendy Levinson , Sir John and Lady Eaton professor and chair 3

- 1 Department of Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and Wilson Centre for Research in Education, University of Toronto, 2075 Bayview Avenue, Room HG 08, Toronto, ON, Canada M4N 3M5

- 2 Department of Paediatrics and Wilson Centre for Research in Education, University of Toronto and SickKids Learning Institute; BMO Financial Group Professor in Health Professions Education Research, University Health Network, 200 Elizabeth Street, Eaton South 1-565, Toronto

- 3 Department of Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

- Correspondence to: A Kuper ayelet94{at}post.harvard.edu

Six key questions will help readers to assess qualitative research

Summary points

Appraising qualitative research is different from appraising quantitative research

Qualitative research papers should show appropriate sampling, data collection, and data analysis

Transferability of qualitative research depends on context and may be enhanced by using theory

Ethics in qualitative research goes beyond review boards’ requirements to involve complex issues of confidentiality, reflexivity, and power

Over the past decade, readers of medical journals have gained skills in critically appraising studies to determine whether the results can be trusted and applied to their own practice settings. Criteria have been designed to assess studies that use quantitative methods, and these are now in common use.

In this article we offer guidance for readers on how to assess a study that uses qualitative research methods by providing six key questions to ask when reading qualitative research (box 1). However, the thorough assessment of qualitative research is an interpretive act and requires informed reflective thought rather than the simple application of a scoring system.

Box 1 Key questions to ask when reading qualitative research studies

Was the sample used in the study appropriate to its research question.

Were the data collected appropriately?

Were the data analysed appropriately?

Can I transfer the results of this study to my own setting?

Does the study adequately address potential ethical issues, including reflexivity?

Overall: is what the researchers did clear?

One of the critical decisions in a qualitative study is whom or what to include in the sample—whom to interview, whom to observe, what texts to analyse. An understanding that qualitative research is based in experience and in the construction of meaning, combined with the specific research question, should guide the sampling process. For example, a study of the experience of survivors of domestic violence that examined their reasons for not seeking help from healthcare providers might focus on interviewing a …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £50 / $60/ €56 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis

- Critical Appraisal and Analysis

Initial Appraisal : Reviewing the source

- What are the author's credentials--institutional affiliation (where he or she works), educational background, past writings, or experience? Is the book or article written on a topic in the author's area of expertise? You can use the various Who's Who publications for the U.S. and other countries and for specific subjects and the biographical information located in the publication itself to help determine the author's affiliation and credentials.

- Has your instructor mentioned this author? Have you seen the author's name cited in other sources or bibliographies? Respected authors are cited frequently by other scholars. For this reason, always note those names that appear in many different sources.

- Is the author associated with a reputable institution or organization? What are the basic values or goals of the organization or institution?

B. Date of Publication

- When was the source published? This date is often located on the face of the title page below the name of the publisher. If it is not there, look for the copyright date on the reverse of the title page. On Web pages, the date of the last revision is usually at the bottom of the home page, sometimes every page.

- Is the source current or out-of-date for your topic? Topic areas of continuing and rapid development, such as the sciences, demand more current information. On the other hand, topics in the humanities often require material that was written many years ago. At the other extreme, some news sources on the Web now note the hour and minute that articles are posted on their site.

C. Edition or Revision

Is this a first edition of this publication or not? Further editions indicate a source has been revised and updated to reflect changes in knowledge, include omissions, and harmonize with its intended reader's needs. Also, many printings or editions may indicate that the work has become a standard source in the area and is reliable. If you are using a Web source, do the pages indicate revision dates?

D. Publisher

Note the publisher. If the source is published by a university press, it is likely to be scholarly. Although the fact that the publisher is reputable does not necessarily guarantee quality, it does show that the publisher may have high regard for the source being published.

E. Title of Journal

Is this a scholarly or a popular journal? This distinction is important because it indicates different levels of complexity in conveying ideas. If you need help in determining the type of journal, see Distinguishing Scholarly from Non-Scholarly Periodicals . Or you may wish to check your journal title in the latest edition of Katz's Magazines for Libraries (Olin Reference Z 6941 .K21, shelved at the reference desk) for a brief evaluative description.

Critical Analysis of the Content

Having made an initial appraisal, you should now examine the body of the source. Read the preface to determine the author's intentions for the book. Scan the table of contents and the index to get a broad overview of the material it covers. Note whether bibliographies are included. Read the chapters that specifically address your topic. Reading the article abstract and scanning the table of contents of a journal or magazine issue is also useful. As with books, the presence and quality of a bibliography at the end of the article may reflect the care with which the authors have prepared their work.

A. Intended Audience

What type of audience is the author addressing? Is the publication aimed at a specialized or a general audience? Is this source too elementary, too technical, too advanced, or just right for your needs?

B. Objective Reasoning

- Is the information covered fact, opinion, or propaganda? It is not always easy to separate fact from opinion. Facts can usually be verified; opinions, though they may be based on factual information, evolve from the interpretation of facts. Skilled writers can make you think their interpretations are facts.

- Does the information appear to be valid and well-researched, or is it questionable and unsupported by evidence? Assumptions should be reasonable. Note errors or omissions.

- Are the ideas and arguments advanced more or less in line with other works you have read on the same topic? The more radically an author departs from the views of others in the same field, the more carefully and critically you should scrutinize his or her ideas.

- Is the author's point of view objective and impartial? Is the language free of emotion-arousing words and bias?

C. Coverage

- Does the work update other sources, substantiate other materials you have read, or add new information? Does it extensively or marginally cover your topic? You should explore enough sources to obtain a variety of viewpoints.

- Is the material primary or secondary in nature? Primary sources are the raw material of the research process. Secondary sources are based on primary sources. For example, if you were researching Konrad Adenauer's role in rebuilding West Germany after World War II, Adenauer's own writings would be one of many primary sources available on this topic. Others might include relevant government documents and contemporary German newspaper articles. Scholars use this primary material to help generate historical interpretations--a secondary source. Books, encyclopedia articles, and scholarly journal articles about Adenauer's role are considered secondary sources. In the sciences, journal articles and conference proceedings written by experimenters reporting the results of their research are primary documents. Choose both primary and secondary sources when you have the opportunity.

D. Writing Style

Is the publication organized logically? Are the main points clearly presented? Do you find the text easy to read, or is it stilted or choppy? Is the author's argument repetitive?

E. Evaluative Reviews

- Locate critical reviews of books in a reviewing source , such as the Articles & Full Text , Book Review Index , Book Review Digest, and ProQuest Research Library . Is the review positive? Is the book under review considered a valuable contribution to the field? Does the reviewer mention other books that might be better? If so, locate these sources for more information on your topic.

- Do the various reviewers agree on the value or attributes of the book or has it aroused controversy among the critics?

- For Web sites, consider consulting this evaluation source from UC Berkeley .

Permissions Information

If you wish to use or adapt any or all of the content of this Guide go to Cornell Library's Research Guides Use Conditions to review our use permissions and our Creative Commons license.

- Next: Tips >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2024 3:08 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/critically_analyzing

JEPS Bulletin

The Official Blog of the Journal of European Psychology Students

How to critically evaluate the quality of a research article?

So what’s the criteria to determine whether a result can be trusted? As it is taught in the first classes in psychology, errors may emerge from any phase of the research process. Therefore, it all boils down to how the research has been conducted and the results presented.

Meltzoff (2007) emphasizes the key issues that can produce flawed results and interpretations and should therefore be carefully considered when reading articles. Here is a reminder on what to bear in mind when reading a research article:

Research question The research must be clear in informing the reader of its aims. Terms should be clearly defined, even more so if they’re new or used in specific non-spread ways. You as a reader should pay particular attention should to errors in logic, especially those regarding causation, relationship or association.

Sample To provide trustworthy conclusions, a sample needs to be representative and adequate. Representativeness depends on the method of selection as well as the assignment. For example, random assignment has its advantages in front of systematic assignment in establishing group equivalence. The sample can be biased when researchers used volunteers or selective attrition. The adequate sample size can be determined by employing power analysis.

Control of confounding variables Extraneous variation can influence research findings, therefore methods to control relevant confounding variables should be applied.

Research designs The research design should be suitable to answer the research question. Readers should distinguish true experimental designs with random assignment from pre-experimental research designs.

Criteria and criteria measures The criteria measures must demonstrate reliability and validity for both, the independent and dependent variable.

Data analysis Appropriate statistical tests should be applied for the type of data obtained, and assumptions for their use met. Post hoc tests should be applied when multiple comparisons are performed. Tables and figures should be clearly labelled. Ideally, effect sizes shou

ld be included throughout giving a clear indication of the variables’ impact.

Discussion and conclusions Does the study allow generalization? Also, limitations of the study should be mentioned. The discussion and conclusions should be consistent with the study’s results. It’s a common mistake to emphasizing the results that are in accordance with the researcher’s expectations while not focusing on the ones that are not. Do the authors of the article you hold in hand do the same?

Ethics Last but not least, ere the ethical standards met? For more information, refer to the APA’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2010).

References American Psychological Association (2010, June 1). American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct . Retrieved July 28, 2011 from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

Meltzoff, J. (2007). Critical Thinking About Research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Edited by: Maris Vainre

Zorana Zupan

Share this:

Related posts:.

- How to critically evaluate internet-based sources?

- How to write a good literature review article?

- How to Read and Get the Most Out of a Journal Article

- Can you find an article in 5 sec? The world of DOIs

How to do library research: Critically Evaluate Information

- Refine your Topic

- Background Information & Facts

- Develop Keywords

- Find Books & eBooks

- Quick Article How-To

- Detailed Article How-To

- Evaluating Web Sources

- How to Create an Annotated Bibliography

Critically Evaluate Information Links

Primary and secondary sources, common information source formats.

Critically evaluating sources using the CRAP Method

Uses of different types of sources

Evaluating web sources

What is a primary source?

A primary source is original information about an event, person, object, product, or work of art in which there has been no comment or analysis about it; a primary source presents information in its original form, neither interpreted nor condensed nor evaluated by other writers.

Think about it in your own context. What primary sources have you created to tell the story of you? (For example, maybe a tweet, a picture of something you enjoy doing, or your student ID card).

What is a secondary source?

A secondary source is an interpretation of a primary source. For example, if your professor asks you to view a film and then write a paragraph about it's meaning to you, the film is the primary source, while your analysis of the film is the secondary source.

What do we mean by “sources”?

|

|

|

|

|

Available in print or as ebooks from your academic library; these are often "monographs" or books that focus closely on a research topic. |

SU Libraries’ Quick Search: See: | Books contain background or historical facts and can be used to frame an analysis or argument. Locate only the information you need in books by skimming chapter titles or by finding keywords in the Index located at the end. |

|

Articles are published within newspapers, magazines, and scholarly journals on a daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly basis. | Go to SU Libraries home page, Find See: | Because they are published more frequently than books, articles can contain the most up-to-date information on a topic. Information found in scholarly journal articles can be used to support specific aspects of your analysis or argument. |

|

Any information made public on the open web. | Search engines on the open web such as Google See Critically Evaluating Sources above. | Although you should generally begin research using the SU Libraries’ resources, you may need to find additional sources using popular search engines like Google. Information from the open web can be created by anyone, so it’s important to any sources you might consider for use in academic work. |

Critically Evaluate Information

Critically Evaluating Sources ( what do we mean by "sources"? )

For college-level research, you'll want to consider using only the highest-quality information sources that you can find. Between the internet and SU’s library, the “ best ” information can depend on the assignment. Here are some ways to determine the best information sources to lend support to your own research.

Use the C.R.A.P. method to evaluate information that you may consider using: (Currency, Relevance, Author expertise, and Purpose)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Check your research assignment directions. Some majors/disciplines require students to use only the most current scholarship in the field, while current scholarship is not important for others. In the sciences, the most up-to-date research is often considered the most valuable. For example, a research study about new technology from ten years ago might be less important than a study conducted last year. |

|

|

| Every single source that shows up in your work should be there for a reason and your reader should not have to guess what that reason is. Every source that you include in your research work should be there to strengthen your idea or argument. |

|

| Consider an author’s credentials before you commit to using the information that they have made public. Experts often have advanced academic degrees, institutional affiliations, and long track records of publishing articles and books containing earlier research. Find author information: – About the Author page – the article citation or the article itself. – See Evaluating Web Sources below | |

|

| An author’s bias can affect the validity or even the truthfulness of the information they have made public, treating one side of an issue more favorably than another. For example, an Apple website will claim its iPhone is the best in the world. Motorola will claim its Droid is the best. They both make this claim because they want to sell their phones. Consumer Reports, an un-biased group who rates products, will study both phones and determine superiority based on what consumers desire and they make that viewpoint known to readers. Using biased sources to support your ideas makes it easy for your audience to challenge the validity of your argument or analysis.

|

Bean, J. C. (2011). Designing and sequencing assignments to teach undergraduate research. In Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed., p. 239). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This information is an adaptation of Evaluating Information – Applying the CRAAP Test created by Meriam Library, CSU, Chico

- << Previous: Detailed Article How-To

- Next: Evaluating Web Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 8, 2021 12:52 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.salisbury.edu/howtodolibrary

- Asbury University

- Research Help

- Critical Evaluation of Sources

- Why Evaluate?

Critical Evaluation of Sources: Why Evaluate?

- Introduction and Criteria

- Web and Articles

While most of us realize that we can’t trust all the information we see or read, we don’t always spend a lot of time considering how we actually make decisions about what to trust. Whether we’re watching the news, reading a friend’s blog, researching a health condition, or using information in some other way, we generally draw on our own values and life experiences to make relatively quick judgments about the validity of the information we are exposed to or seek out. Sometimes we don’t even consider the fact that we made a judgment about what to trust in the first place. We’re simply on autopilot.

Although the amount of deep thinking we need to put into evaluating the validity of an information source can vary depending on the significance of the situation, we ultimately make better decisions and construct more convincing arguments when we have a strong understanding of the quality of the information we’re using (or not using). This is especially true in an academic context, where our ability to create knowledge and meaning depends on our ability to analyze and interpret information with precision.

To evaluate information, then, is to analyze information from a critical perspective. The evaluative process requires us to step back and carefully consider the sources we use and how we use them, to not rush to judgment but to think through the content of the articles we’re reading or the online search results we’re browsing. We also need to consider the relationships among different sources and how they work together to form “conversations” around certain topics or issues. A “conversation” in this sense refers to the diverse perspectives and arguments surrounding a particular research question (or set of questions).

The questions in this guide can help you think through the evaluation of information sources. Keep in mind that evaluation is not simply about determining whether a source is “reliable” or “not reliable.” It’s rarely that easy or straightforward. Instead, it’s more useful to consider the degree to which a source is reliable for a given purpose. The primary goal of evaluation is to understand the significance and value of a source in relation to other sources and your own thinking on a topic.

Note that some evaluative questions will be more important than others depending on your needs as a researcher. Figuring out which questions are important to ask in a given situation is part of the research process. Also note that your evaluation of a source may evolve over time. For instance, a source that seems very useful early on may prove less useful as your project develops. Likewise, a source that seems insignificant at the beginning of a project may turn out to be your most significant source later in the research process.

From: http://louisville.libguides.com/evaluation

This evaluation process is really no different than the process people use everyday as they acquire all types of information from a neighbor, a friend, a newspaper, a television broadcast, or a bulletin board flyer.

All of this happens so automatically, you don't even realize you're doing it. While you should evaluate all of information sources (books, periodical articles, etc.) before using them in your research, it is most vital that you evaluate the information you find on the Internet. Every book and article published (even those available in Internet-based databases) goes through some sort of evaluation process, but Web pages go through no such pre-publication evaluation.

The number of resources available via the Internet is immense. Companies, organizations, educational institutions, communities and individual people all serve as information providers for the Internet community. Savvy members of the Internet community are aware that there are few, if any, quality controls for the information that is made available. Accurate and reliable data may share the computer screen with data that is inaccurate, unreliable, or even purposely false. In addition, the differences between the two types of data may be imperceptible, especially for someone who is not an expert in the topic area. Because the Internet is not the responsibility of any one organization or institution, it seems unlikely that any universal quality control will be established in the near future. In view of this, members of the Internet community must prepare themselves to be critically skilled consumers of the information they find.

Hoaxes, Fallacies, Propaganda - OH MY!

Types of hoaxes with examples - http://virtualchase.justia.com/hoaxes-and-other-bad-information

Listing of Types of Fallacies - http://www.nizkor.org/features/fallacies/

Propaganda - http://guides.library.jhu.edu/content.php?pid=198142&sid=1657614

Critical Thinkers

Characteristics of Critical Thinkers: http://www.mhhe.com/socscience/philosophy/reichenbach/m1_chap02studyguide.html

Defining Critical Thinking

A Source: http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766

Which states:

The Problem Everyone thinks; it is our nature to do so. But much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or down-right prejudiced. Yet the quality of our life and that of what we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought. Shoddy thinking is costly, both in money and in quality of life. Excellence in thought, however, must be systematically cultivated.

A Definition Critical thinking is that mode of thinking - about any subject, content, or problem - in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them.

The Result A well cultivated critical thinker:

- raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- thinks openmindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

Critical thinking is, in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism.

Critical Thinking

Critical Thinking and introduction to the basic skills by William Hughes 1992 Broadview Press Ltd. Lewiston, NY Isbn 1-921149-73-2 The primary focus of critical thinking skills is on determining whether arguments are sound, i.e. whether they have true premises and logical strength.But determining the soundness of arguments is not a simple matter, for three reasons.First, before we can assess an argument we must determine its precise meaning. Second, determining the truth or falsity of statements is often a difficult task. Third, assessing argument is complex because there are several different types of inferences and each type requires a different kind of assessment. There three types of skills—

interpretive skills, verification skills, and reason skills—constitutes what are usually referred to as critical thinking skills. … mastering critical thinking skills is also a matter of intellectual self-respect. We all have the capacity to learn how to distinguish good arguments from bad ones and to work out for ourselves what we ought and ought not to believe, and it diminishes us as persons if we let others do our thinking for us. If we are not prepared to think for ourselves, and to make the effort to learn how do this well, we will always remain slaves to the ideas and values of others and to our own ignorance. P. 11 Argumentation and Debate Critical thinking for reasoned decision Making Austin J. Freeley and David L. Steinberg 10th edition 2000 Wadsworth/Thomson Learning Belmont, CA Isbn 0-534-46115-2