What this handout is about

This handout discusses common logical fallacies that you may encounter in your own writing or the writing of others. The handout provides definitions, examples, and tips on avoiding these fallacies.

Most academic writing tasks require you to make an argument—that is, to present reasons for a particular claim or interpretation you are putting forward. You may have been told that you need to make your arguments more logical or stronger. And you may have worried that you simply aren’t a logical person or wondered what it means for an argument to be strong. Learning to make the best arguments you can is an ongoing process, but it isn’t impossible: “Being logical” is something anyone can do, with practice.

Each argument you make is composed of premises (this is a term for statements that express your reasons or evidence) that are arranged in the right way to support your conclusion (the main claim or interpretation you are offering). You can make your arguments stronger by:

- using good premises (ones you have good reason to believe are both true and relevant to the issue at hand),

- making sure your premises provide good support for your conclusion (and not some other conclusion, or no conclusion at all),

- checking that you have addressed the most important or relevant aspects of the issue (that is, that your premises and conclusion focus on what is really important to the issue), and

- not making claims that are so strong or sweeping that you can’t really support them.

You also need to be sure that you present all of your ideas in an orderly fashion that readers can follow. See our handouts on argument and organization for some tips that will improve your arguments.

This handout describes some ways in which arguments often fail to do the things listed above; these failings are called fallacies. If you’re having trouble developing your argument, check to see if a fallacy is part of the problem.

It is particularly easy to slip up and commit a fallacy when you have strong feelings about your topic—if a conclusion seems obvious to you, you’re more likely to just assume that it is true and to be careless with your evidence. To help you see how people commonly make this mistake, this handout uses a number of controversial political examples—arguments about subjects like abortion, gun control, the death penalty, gay marriage, euthanasia, and pornography. The purpose of this handout, though, is not to argue for any particular position on any of these issues; rather, it is to illustrate weak reasoning, which can happen in pretty much any kind of argument. Please be aware that the claims in these examples are just made-up illustrations—they haven’t been researched, and you shouldn’t use them as evidence in your own writing.

What are fallacies?

Fallacies are defects that weaken arguments. By learning to look for them in your own and others’ writing, you can strengthen your ability to evaluate the arguments you make, read, and hear. It is important to realize two things about fallacies: first, fallacious arguments are very, very common and can be quite persuasive, at least to the casual reader or listener. You can find dozens of examples of fallacious reasoning in newspapers, advertisements, and other sources. Second, it is sometimes hard to evaluate whether an argument is fallacious. An argument might be very weak, somewhat weak, somewhat strong, or very strong. An argument that has several stages or parts might have some strong sections and some weak ones. The goal of this handout, then, is not to teach you how to label arguments as fallacious or fallacy-free, but to help you look critically at your own arguments and move them away from the “weak” and toward the “strong” end of the continuum.

So what do fallacies look like?

For each fallacy listed, there is a definition or explanation, an example, and a tip on how to avoid committing the fallacy in your own arguments.

Hasty generalization

Definition: Making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate (usually because it is atypical or too small). Stereotypes about people (“librarians are shy and smart,” “wealthy people are snobs,” etc.) are a common example of the principle underlying hasty generalization.

Example: “My roommate said her philosophy class was hard, and the one I’m in is hard, too. All philosophy classes must be hard!” Two people’s experiences are, in this case, not enough on which to base a conclusion.

Tip: Ask yourself what kind of “sample” you’re using: Are you relying on the opinions or experiences of just a few people, or your own experience in just a few situations? If so, consider whether you need more evidence, or perhaps a less sweeping conclusion. (Notice that in the example, the more modest conclusion “Some philosophy classes are hard for some students” would not be a hasty generalization.)

Missing the point

Definition: The premises of an argument do support a particular conclusion—but not the conclusion that the arguer actually draws.

Example: “The seriousness of a punishment should match the seriousness of the crime. Right now, the punishment for drunk driving may simply be a fine. But drunk driving is a very serious crime that can kill innocent people. So the death penalty should be the punishment for drunk driving.” The argument actually supports several conclusions—”The punishment for drunk driving should be very serious,” in particular—but it doesn’t support the claim that the death penalty, specifically, is warranted.

Tip: Separate your premises from your conclusion. Looking at the premises, ask yourself what conclusion an objective person would reach after reading them. Looking at your conclusion, ask yourself what kind of evidence would be required to support such a conclusion, and then see if you’ve actually given that evidence. Missing the point often occurs when a sweeping or extreme conclusion is being drawn, so be especially careful if you know you’re claiming something big.

Post hoc (also called false cause)

This fallacy gets its name from the Latin phrase “post hoc, ergo propter hoc,” which translates as “after this, therefore because of this.”

Definition: Assuming that because B comes after A, A caused B. Of course, sometimes one event really does cause another one that comes later—for example, if I register for a class, and my name later appears on the roll, it’s true that the first event caused the one that came later. But sometimes two events that seem related in time aren’t really related as cause and event. That is, correlation isn’t the same thing as causation.

Examples: “President Jones raised taxes, and then the rate of violent crime went up. Jones is responsible for the rise in crime.” The increase in taxes might or might not be one factor in the rising crime rates, but the argument hasn’t shown us that one caused the other.

Tip: To avoid the post hoc fallacy, the arguer would need to give us some explanation of the process by which the tax increase is supposed to have produced higher crime rates. And that’s what you should do to avoid committing this fallacy: If you say that A causes B, you should have something more to say about how A caused B than just that A came first and B came later.

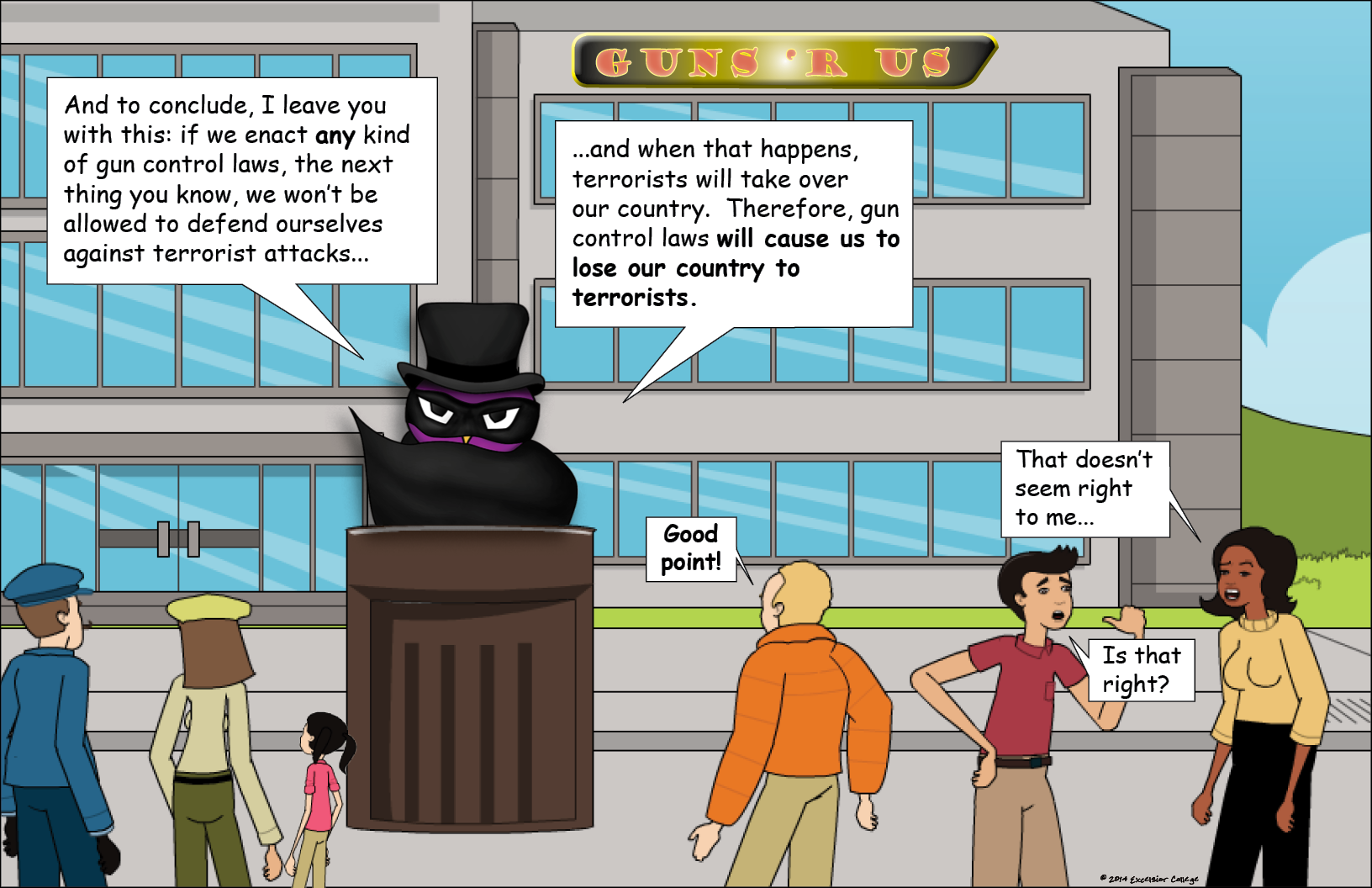

Slippery slope

Definition: The arguer claims that a sort of chain reaction, usually ending in some dire consequence, will take place, but there’s really not enough evidence for that assumption. The arguer asserts that if we take even one step onto the “slippery slope,” we will end up sliding all the way to the bottom; they assume we can’t stop partway down the hill.

Example: “Animal experimentation reduces our respect for life. If we don’t respect life, we are likely to be more and more tolerant of violent acts like war and murder. Soon our society will become a battlefield in which everyone constantly fears for their lives. It will be the end of civilization. To prevent this terrible consequence, we should make animal experimentation illegal right now.” Since animal experimentation has been legal for some time and civilization has not yet ended, it seems particularly clear that this chain of events won’t necessarily take place. Even if we believe that experimenting on animals reduces respect for life, and loss of respect for life makes us more tolerant of violence, that may be the spot on the hillside at which things stop—we may not slide all the way down to the end of civilization. And so we have not yet been given sufficient reason to accept the arguer’s conclusion that we must make animal experimentation illegal right now.

Like post hoc, slippery slope can be a tricky fallacy to identify, since sometimes a chain of events really can be predicted to follow from a certain action. Here’s an example that doesn’t seem fallacious: “If I fail English 101, I won’t be able to graduate. If I don’t graduate, I probably won’t be able to get a good job, and I may very well end up doing temp work or flipping burgers for the next year.”

Tip: Check your argument for chains of consequences, where you say “if A, then B, and if B, then C,” and so forth. Make sure these chains are reasonable.

Weak analogy

Definition: Many arguments rely on an analogy between two or more objects, ideas, or situations. If the two things that are being compared aren’t really alike in the relevant respects, the analogy is a weak one, and the argument that relies on it commits the fallacy of weak analogy.

Example: “Guns are like hammers—they’re both tools with metal parts that could be used to kill someone. And yet it would be ridiculous to restrict the purchase of hammers—so restrictions on purchasing guns are equally ridiculous.” While guns and hammers do share certain features, these features (having metal parts, being tools, and being potentially useful for violence) are not the ones at stake in deciding whether to restrict guns. Rather, we restrict guns because they can easily be used to kill large numbers of people at a distance. This is a feature hammers do not share—it would be hard to kill a crowd with a hammer. Thus, the analogy is weak, and so is the argument based on it.

If you think about it, you can make an analogy of some kind between almost any two things in the world: “My paper is like a mud puddle because they both get bigger when it rains (I work more when I’m stuck inside) and they’re both kind of murky.” So the mere fact that you can draw an analogy between two things doesn’t prove much, by itself.

Arguments by analogy are often used in discussing abortion—arguers frequently compare fetuses with adult human beings, and then argue that treatment that would violate the rights of an adult human being also violates the rights of fetuses. Whether these arguments are good or not depends on the strength of the analogy: do adult humans and fetuses share the properties that give adult humans rights? If the property that matters is having a human genetic code or the potential for a life full of human experiences, adult humans and fetuses do share that property, so the argument and the analogy are strong; if the property is being self-aware, rational, or able to survive on one’s own, adult humans and fetuses don’t share it, and the analogy is weak.

Tip: Identify what properties are important to the claim you’re making, and see whether the two things you’re comparing both share those properties.

Appeal to authority

Definition: Often we add strength to our arguments by referring to respected sources or authorities and explaining their positions on the issues we’re discussing. If, however, we try to get readers to agree with us simply by impressing them with a famous name or by appealing to a supposed authority who really isn’t much of an expert, we commit the fallacy of appeal to authority.

Example: “We should abolish the death penalty. Many respected people, such as actor Guy Handsome, have publicly stated their opposition to it.” While Guy Handsome may be an authority on matters having to do with acting, there’s no particular reason why anyone should be moved by his political opinions—he is probably no more of an authority on the death penalty than the person writing the paper.

Tip: There are two easy ways to avoid committing appeal to authority: First, make sure that the authorities you cite are experts on the subject you’re discussing. Second, rather than just saying “Dr. Authority believes X, so we should believe it, too,” try to explain the reasoning or evidence that the authority used to arrive at their opinion. That way, your readers have more to go on than a person’s reputation. It also helps to choose authorities who are perceived as fairly neutral or reasonable, rather than people who will be perceived as biased.

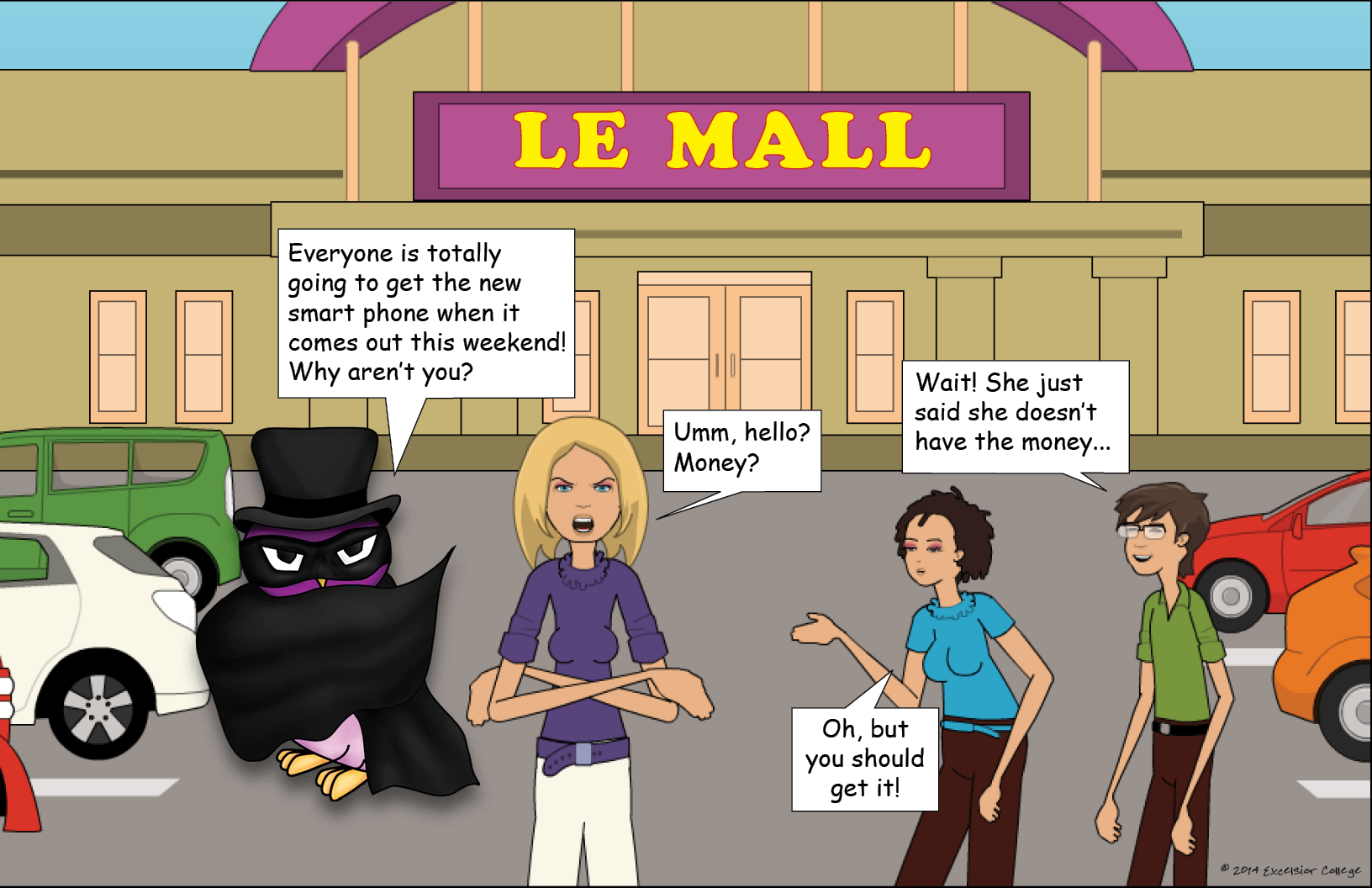

Definition: The Latin name of this fallacy means “to the people.” There are several versions of the ad populum fallacy, but in all of them, the arguer takes advantage of the desire most people have to be liked and to fit in with others and uses that desire to try to get the audience to accept their argument. One of the most common versions is the bandwagon fallacy, in which the arguer tries to convince the audience to do or believe something because everyone else (supposedly) does.

Example: “Gay marriages are just immoral. 70% of Americans think so!” While the opinion of most Americans might be relevant in determining what laws we should have, it certainly doesn’t determine what is moral or immoral: there was a time where a substantial number of Americans were in favor of segregation, but their opinion was not evidence that segregation was moral. The arguer is trying to get us to agree with the conclusion by appealing to our desire to fit in with other Americans.

Tip: Make sure that you aren’t recommending that your readers believe your conclusion because everyone else believes it, all the cool people believe it, people will like you better if you believe it, and so forth. Keep in mind that the popular opinion is not always the right one.

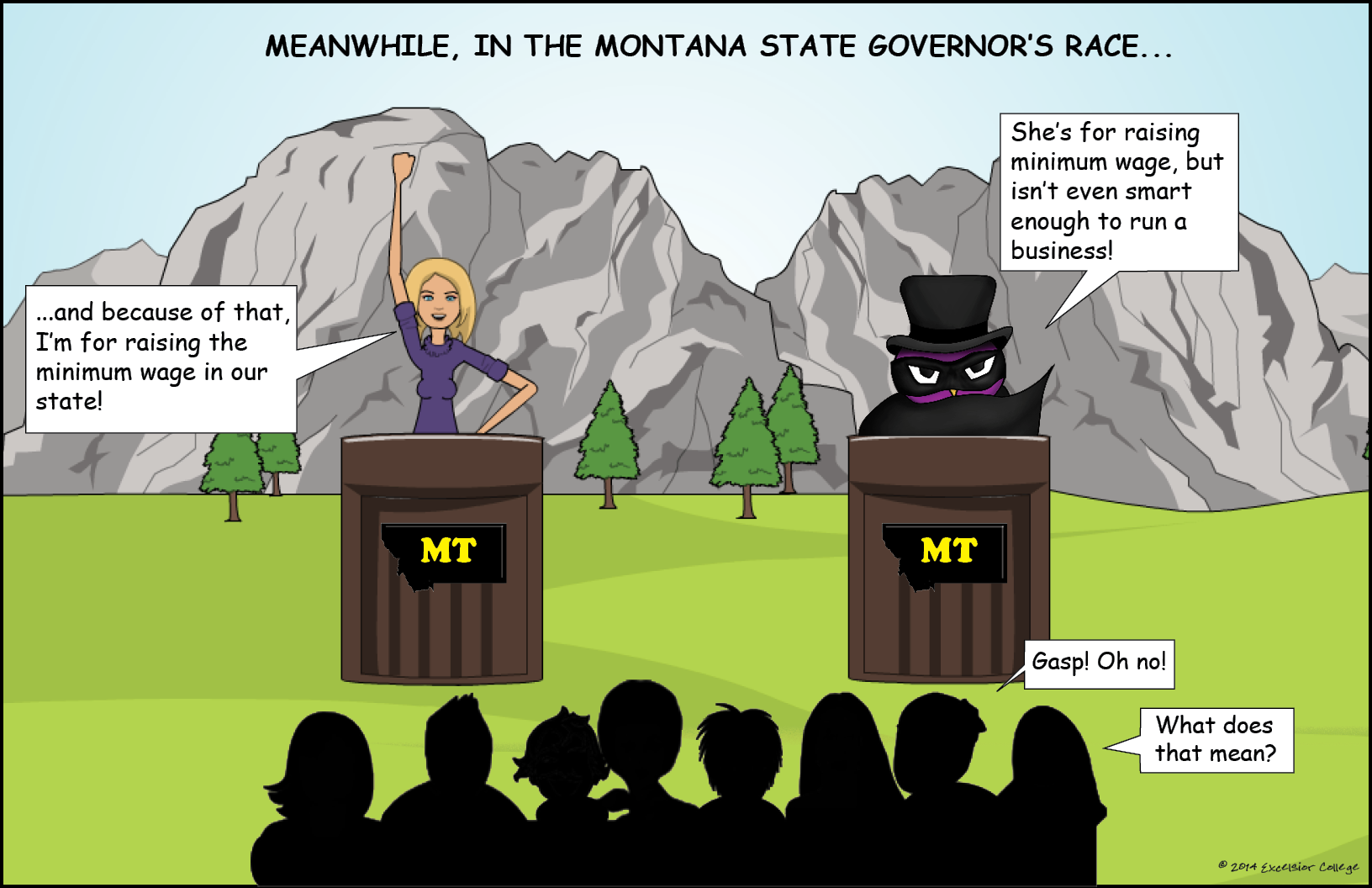

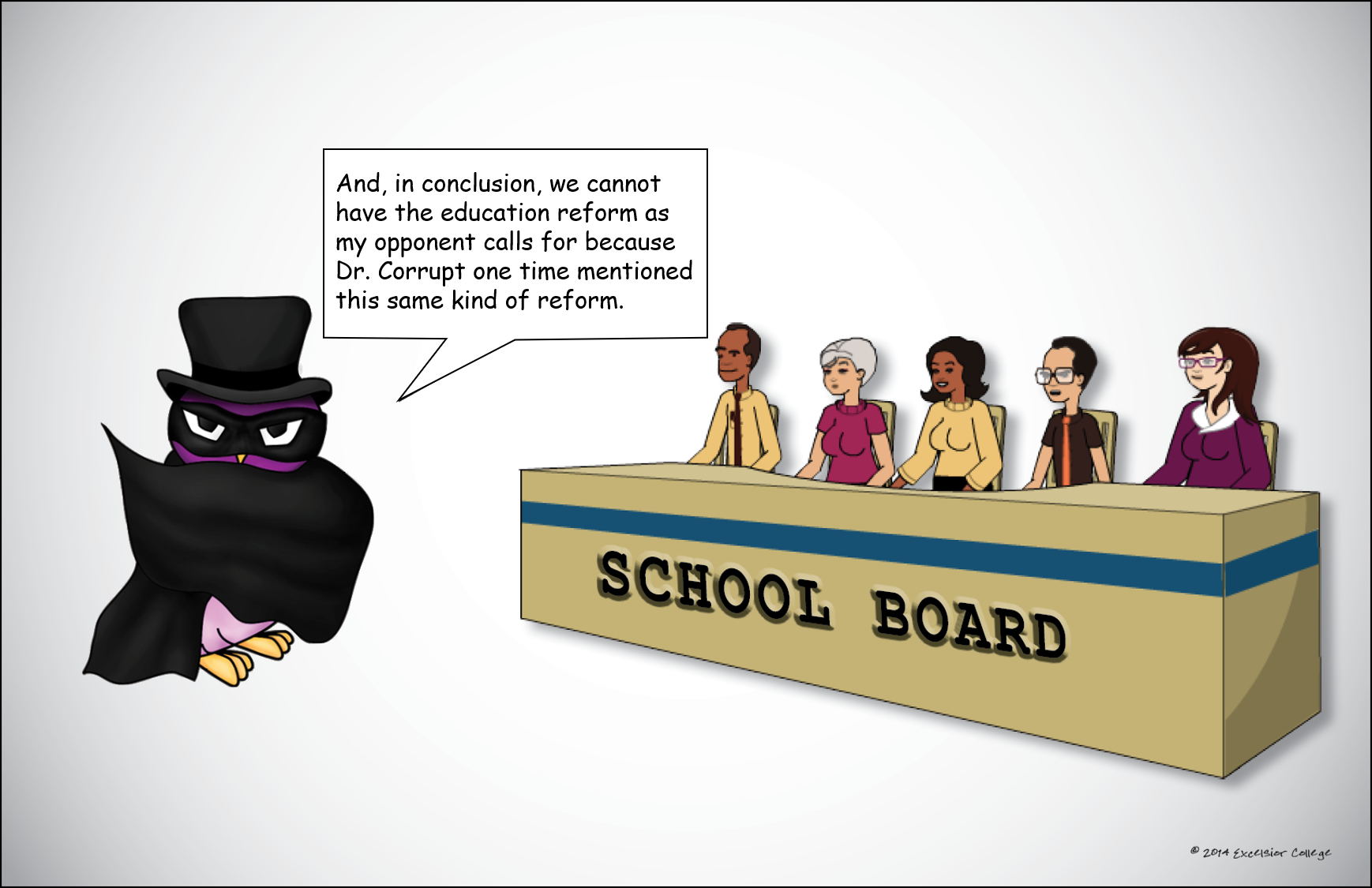

Ad hominem and tu quoque

Definitions: Like the appeal to authority and ad populum fallacies, the ad hominem (“against the person”) and tu quoque (“you, too!”) fallacies focus our attention on people rather than on arguments or evidence. In both of these arguments, the conclusion is usually “You shouldn’t believe So-and-So’s argument.” The reason for not believing So-and-So is that So-and-So is either a bad person (ad hominem) or a hypocrite (tu quoque). In an ad hominem argument, the arguer attacks their opponent instead of the opponent’s argument.

Examples: “Andrea Dworkin has written several books arguing that pornography harms women. But Dworkin is just ugly and bitter, so why should we listen to her?” Dworkin’s appearance and character, which the arguer has characterized so ungenerously, have nothing to do with the strength of her argument, so using them as evidence is fallacious.

In a tu quoque argument, the arguer points out that the opponent has actually done the thing they are arguing against, and so the opponent’s argument shouldn’t be listened to. Here’s an example: imagine that your parents have explained to you why you shouldn’t smoke, and they’ve given a lot of good reasons—the damage to your health, the cost, and so forth. You reply, “I won’t accept your argument, because you used to smoke when you were my age. You did it, too!” The fact that your parents have done the thing they are condemning has no bearing on the premises they put forward in their argument (smoking harms your health and is very expensive), so your response is fallacious.

Tip: Be sure to stay focused on your opponents’ reasoning, rather than on their personal character. (The exception to this is, of course, if you are making an argument about someone’s character—if your conclusion is “President Jones is an untrustworthy person,” premises about her untrustworthy acts are relevant, not fallacious.)

Appeal to pity

Definition: The appeal to pity takes place when an arguer tries to get people to accept a conclusion by making them feel sorry for someone.

Examples: “I know the exam is graded based on performance, but you should give me an A. My cat has been sick, my car broke down, and I’ve had a cold, so it was really hard for me to study!” The conclusion here is “You should give me an A.” But the criteria for getting an A have to do with learning and applying the material from the course; the principle the arguer wants us to accept (people who have a hard week deserve A’s) is clearly unacceptable. The information the arguer has given might feel relevant and might even get the audience to consider the conclusion—but the information isn’t logically relevant, and so the argument is fallacious. Here’s another example: “It’s wrong to tax corporations—think of all the money they give to charity, and of the costs they already pay to run their businesses!”

Tip: Make sure that you aren’t simply trying to get your audience to agree with you by making them feel sorry for someone.

Appeal to ignorance

Definition: In the appeal to ignorance, the arguer basically says, “Look, there’s no conclusive evidence on the issue at hand. Therefore, you should accept my conclusion on this issue.”

Example: “People have been trying for centuries to prove that God exists. But no one has yet been able to prove it. Therefore, God does not exist.” Here’s an opposing argument that commits the same fallacy: “People have been trying for years to prove that God does not exist. But no one has yet been able to prove it. Therefore, God exists.” In each case, the arguer tries to use the lack of evidence as support for a positive claim about the truth of a conclusion. There is one situation in which doing this is not fallacious: if qualified researchers have used well-thought-out methods to search for something for a long time, they haven’t found it, and it’s the kind of thing people ought to be able to find, then the fact that they haven’t found it constitutes some evidence that it doesn’t exist.

Tip: Look closely at arguments where you point out a lack of evidence and then draw a conclusion from that lack of evidence.

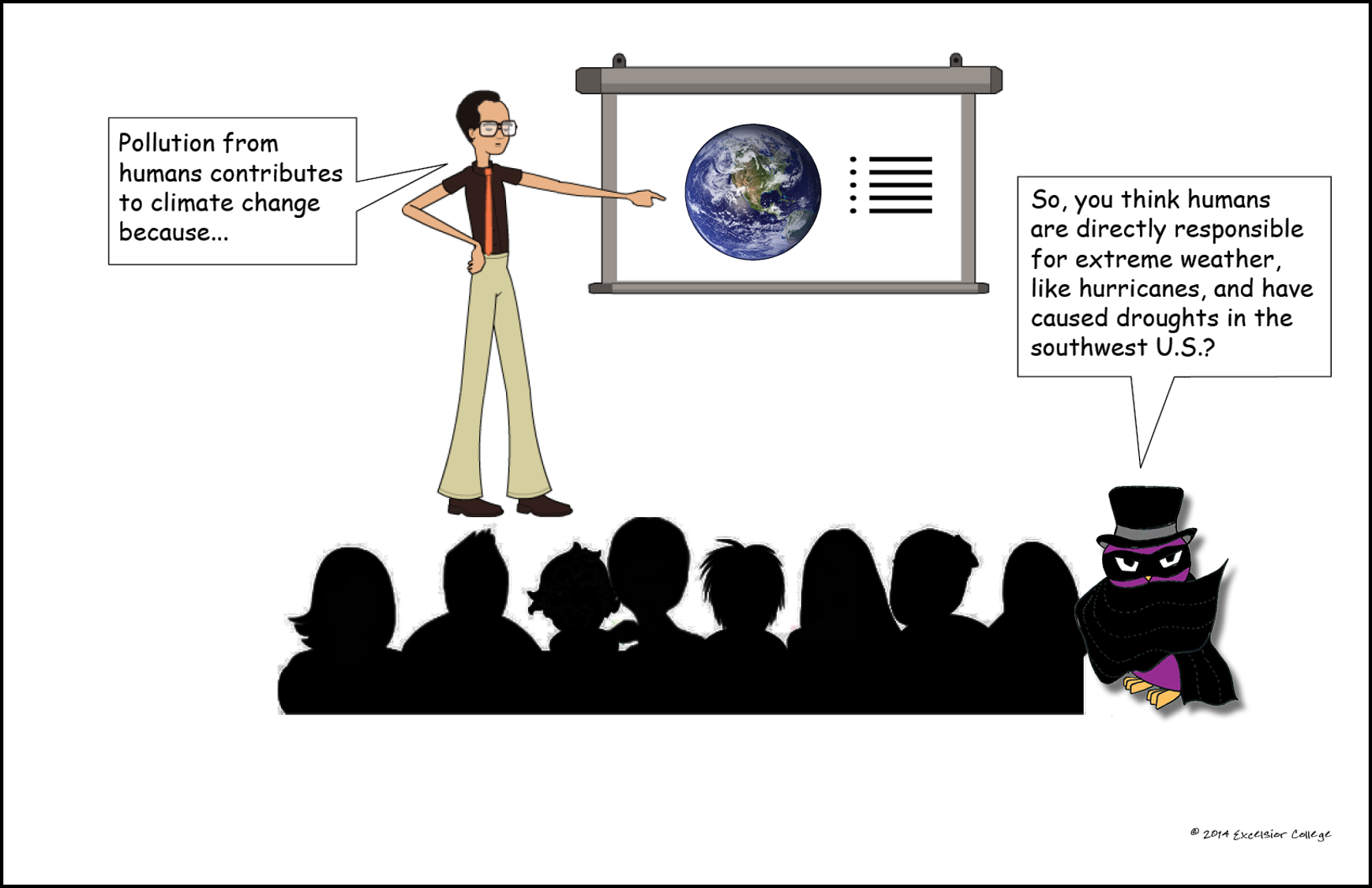

Definition: One way of making our own arguments stronger is to anticipate and respond in advance to the arguments that an opponent might make. In the straw man fallacy, the arguer sets up a weak version of the opponent’s position and tries to score points by knocking it down. But just as being able to knock down a straw man (like a scarecrow) isn’t very impressive, defeating a watered-down version of your opponent’s argument isn’t very impressive either.

Example: “Feminists want to ban all pornography and punish everyone who looks at it! But such harsh measures are surely inappropriate, so the feminists are wrong: porn and its fans should be left in peace.” The feminist argument is made weak by being overstated. In fact, most feminists do not propose an outright “ban” on porn or any punishment for those who merely view it or approve of it; often, they propose some restrictions on particular things like child porn, or propose to allow people who are hurt by porn to sue publishers and producers—not viewers—for damages. So the arguer hasn’t really scored any points; they have just committed a fallacy.

Tip: Be charitable to your opponents. State their arguments as strongly, accurately, and sympathetically as possible. If you can knock down even the best version of an opponent’s argument, then you’ve really accomplished something.

Red herring

Definition: Partway through an argument, the arguer goes off on a tangent, raising a side issue that distracts the audience from what’s really at stake. Often, the arguer never returns to the original issue.

Example: “Grading this exam on a curve would be the most fair thing to do. After all, classes go more smoothly when the students and the professor are getting along well.” Let’s try our premise-conclusion outlining to see what’s wrong with this argument:

Premise: Classes go more smoothly when the students and the professor are getting along well.

Conclusion: Grading this exam on a curve would be the most fair thing to do.

When we lay it out this way, it’s pretty obvious that the arguer went off on a tangent—the fact that something helps people get along doesn’t necessarily make it more fair; fairness and justice sometimes require us to do things that cause conflict. But the audience may feel like the issue of teachers and students agreeing is important and be distracted from the fact that the arguer has not given any evidence as to why a curve would be fair.

Tip: Try laying your premises and conclusion out in an outline-like form. How many issues do you see being raised in your argument? Can you explain how each premise supports the conclusion?

False dichotomy

Definition: In false dichotomy, the arguer sets up the situation so it looks like there are only two choices. The arguer then eliminates one of the choices, so it seems that we are left with only one option: the one the arguer wanted us to pick in the first place. But often there are really many different options, not just two—and if we thought about them all, we might not be so quick to pick the one the arguer recommends.

Example: “Caldwell Hall is in bad shape. Either we tear it down and put up a new building, or we continue to risk students’ safety. Obviously we shouldn’t risk anyone’s safety, so we must tear the building down.” The argument neglects to mention the possibility that we might repair the building or find some way to protect students from the risks in question—for example, if only a few rooms are in bad shape, perhaps we shouldn’t hold classes in those rooms.

Tip: Examine your own arguments: if you’re saying that we have to choose between just two options, is that really so? Or are there other alternatives you haven’t mentioned? If there are other alternatives, don’t just ignore them—explain why they, too, should be ruled out. Although there’s no formal name for it, assuming that there are only three options, four options, etc. when really there are more is similar to false dichotomy and should also be avoided.

Begging the question

Definition: A complicated fallacy; it comes in several forms and can be harder to detect than many of the other fallacies we’ve discussed. Basically, an argument that begs the question asks the reader to simply accept the conclusion without providing real evidence; the argument either relies on a premise that says the same thing as the conclusion (which you might hear referred to as “being circular” or “circular reasoning”), or simply ignores an important (but questionable) assumption that the argument rests on. Sometimes people use the phrase “beg the question” as a sort of general criticism of arguments, to mean that an arguer hasn’t given very good reasons for a conclusion, but that’s not the meaning we’re going to discuss here.

Examples: “Active euthanasia is morally acceptable. It is a decent, ethical thing to help another human being escape suffering through death.” Let’s lay this out in premise-conclusion form:

Premise: It is a decent, ethical thing to help another human being escape suffering through death.

Conclusion: Active euthanasia is morally acceptable.

If we “translate” the premise, we’ll see that the arguer has really just said the same thing twice: “decent, ethical” means pretty much the same thing as “morally acceptable,” and “help another human being escape suffering through death” means something pretty similar to “active euthanasia.” So the premise basically says, “active euthanasia is morally acceptable,” just like the conclusion does. The arguer hasn’t yet given us any real reasons why euthanasia is acceptable; instead, they have left us asking “well, really, why do you think active euthanasia is acceptable?” Their argument “begs” (that is, evades) the real question.

Here’s a second example of begging the question, in which a dubious premise which is needed to make the argument valid is completely ignored: “Murder is morally wrong. So active euthanasia is morally wrong.” The premise that gets left out is “active euthanasia is murder.” And that is a debatable premise—again, the argument “begs” or evades the question of whether active euthanasia is murder by simply not stating the premise. The arguer is hoping we’ll just focus on the uncontroversial premise, “Murder is morally wrong,” and not notice what is being assumed.

Tip: One way to try to avoid begging the question is to write out your premises and conclusion in a short, outline-like form. See if you notice any gaps, any steps that are required to move from one premise to the next or from the premises to the conclusion. Write down the statements that would fill those gaps. If the statements are controversial and you’ve just glossed over them, you might be begging the question. Next, check to see whether any of your premises basically says the same thing as the conclusion (but in different words). If so, you’re probably begging the question. The moral of the story: you can’t just assume or use as uncontroversial evidence the very thing you’re trying to prove.

Equivocation

Definition: Equivocation is sliding between two or more different meanings of a single word or phrase that is important to the argument.

Example: “Giving money to charity is the right thing to do. So charities have a right to our money.” The equivocation here is on the word “right”: “right” can mean both something that is correct or good (as in “I got the right answers on the test”) and something to which someone has a claim (as in “everyone has a right to life”). Sometimes an arguer will deliberately, sneakily equivocate, often on words like “freedom,” “justice,” “rights,” and so forth; other times, the equivocation is a mistake or misunderstanding. Either way, it’s important that you use the main terms of your argument consistently.

Tip: Identify the most important words and phrases in your argument and ask yourself whether they could have more than one meaning. If they could, be sure you aren’t slipping and sliding between those meanings.

So how do I find fallacies in my own writing?

Here are some general tips for finding fallacies in your own arguments:

- Pretend you disagree with the conclusion you’re defending. What parts of the argument would now seem fishy to you? What parts would seem easiest to attack? Give special attention to strengthening those parts.

- List your main points; under each one, list the evidence you have for it. Seeing your claims and evidence laid out this way may make you realize that you have no good evidence for a particular claim, or it may help you look more critically at the evidence you’re using.

- Learn which types of fallacies you’re especially prone to, and be careful to check for them in your work. Some writers make lots of appeals to authority; others are more likely to rely on weak analogies or set up straw men. Read over some of your old papers to see if there’s a particular kind of fallacy you need to watch out for.

- Be aware that broad claims need more proof than narrow ones. Claims that use sweeping words like “all,” “no,” “none,” “every,” “always,” “never,” “no one,” and “everyone” are sometimes appropriate—but they require a lot more proof than less-sweeping claims that use words like “some,” “many,” “few,” “sometimes,” “usually,” and so forth.

- Double check your characterizations of others, especially your opponents, to be sure they are accurate and fair.

Can I get some practice with this?

Yes, you can. Follow this link to see a sample argument that’s full of fallacies (and then you can follow another link to get an explanation of each one). Then there’s a more well-constructed argument on the same topic.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Copi, Irving M., Carl Cohen, and Victor Rodych. 1998. Introduction to Logic . London: Pearson Education.

Hurley, Patrick J. 2000. A Concise Introduction to Logic , 7th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

30 Common Logical Fallacies–A Study Starter

We help improve your debate skills with our rundown of the 30 most common logical fallacies. Not even sure what a logical fallacy is? Stick with us, we’ll cover the basics in this Study Starter.

What is a logical fallacy?

Nothing is more frustrating than debating somebody who has no idea what they’re talking about. Well, actually there is. It’s even more frustrating to debate somebody when you, yourself, have no idea what you’re talking about. So what must you do to avoid these frustrations? You can start by getting to know the most common logical fallacies.

A logical fallacy is an argument based on faulty reasoning. While fallacies come in a variety of forms, they all share the same destructive power, namely, to dismantle the validity of your entire argument. Whether you’re building a case for a position paper, engaging your classmates in a lively debate, or storing up pithy political one-liners for your next Twitter war, you need to know these common logical fallacies.

But first...

What is Logic?

Logic describes the rules and principles for making correct arguments and avoiding incorrect arguments. Logic is a key branch of philosophy, and logic students learn how to analyze and appraise arguments. In logic, certain valid rules of inference must be acknowledged and adhered to in order for an argument to be considered legitimate. Logic attempts to take us from truth to truth. In deductive logic, the truth of premises guarantees the truth of conclusions. In other types of logical inference (such as with inductive logic), the point is to make the conclusion more probable based on the truth of the premises.

Logic acknowledges the shared truths among us and guides us to uncover new truths. Logic is therefore the very fabric of meaningful debate. Without logic, human inquiry grinds to a standstill because we have no reliable way to build our knowledge based on previously uncovered truths.

What is a Logical Fallacy?

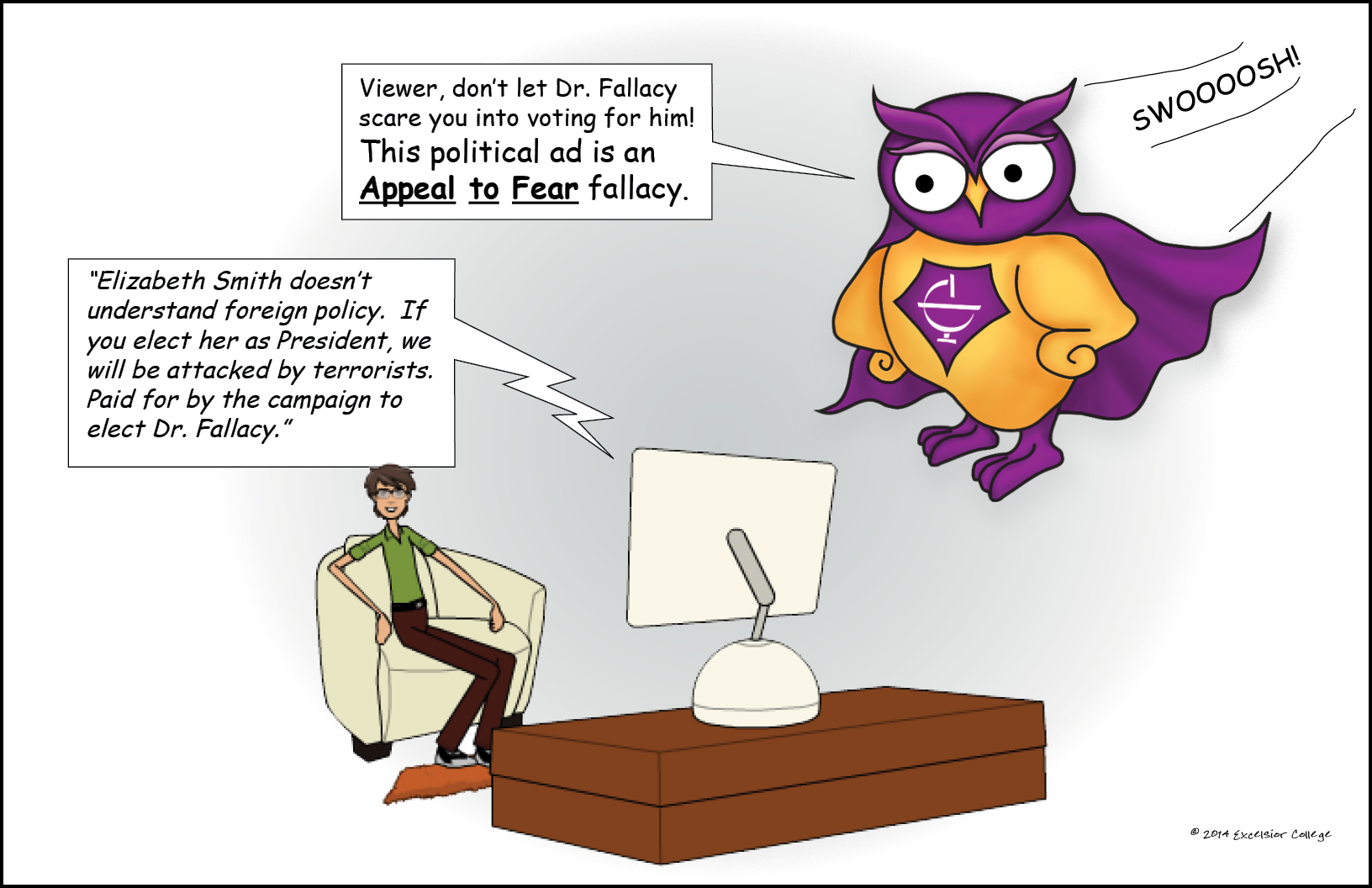

Logical fallacies are bogus modes of reasoning that can appear legitimate but in fact violate accepted rules of inference. Logical fallacies can be tricky. By masquerading as legitimate arguments, they can fool us into thinking that they are legitimate. But closer inspection reveals the critical flaw at the heart of any given logical fallacy. Such flaws are not always easily detected, especially in the heat of debate.

To confound matters, logical fallacies often have an element of truth. But the truth gets misused by faulty logic so that the desired conclusion is not properly justified. A fallacy may even reach a true conclusion, but by arriving there in the wrong way, render the conclusion unconvincing. Moreover, fallacies aren’t always driven by the desire to deceive or manipulate. Fallacies can also be rooted in bias, emotion, or misunderstanding, which can sometimes be less immediately apparent.

Why are logical fallacies so common? The answer is simple: they work! To say that logical fallacies work does not mean that they help us gain knowledge or insight into truths about the world. Rather, it means that bogus types of reasoning are often amazingly effective at getting people to believe things that they shouldn’t believe.

Lawyers, politicians, and marketers often have the keen ability to use fallacious arguments as weapons. This is rarely an accident. Unfortunately, when people want to believe something, they’ll often enlist logical fallacies to help convince themselves and others of its truth. Clear, careful, and critical thinking, therefore, requires calling out logical fallacies.

Broadly speaking, logical fallacies fall into two categories:

- Informal Fallacies, in which what the argument says, or how it says it, is flawed; and

- Formal Fallacies, in which the step-by-step progression or “form” of logical reasoning in an argument is flawed.

Why Does It Matter?

Detecting the flaws in an argument is important. Sure, identifying the flaws in an argument can be personally gratifying by helping you win a debate. But logical fallacies do a lot of damage. They threaten to undermine shared truths and advance unwarranted conclusions that rest on flawed foundations. In an age of fake news, they help fake news to proliferate.

This is your chance to spot the devil in the details. Learn how not to be deceived, because, at the risk of sounding like an alarmist, there are people out there trying to deceive you. If the purpose of debate is to illuminate the truth at the center of a discussion, logical fallacies are the smoke and shadows that obscure this truth, keeping the participants on every side of the issue from seeing clearly.

Learn these logical fallacies. Call them out when you see them. Avoid committing them yourself. This is one of the most powerful actions you can take toward preserving and advancing truth.

Not convinced? Check out our 5 Reasons You Should Take Logic Your First Year in College .

Otherwise, read on and find out which logical fallacies you’re most likely to encounter in a debate...

Common Informal Fallacies

1. ad hominem.

An abbreviated phrase meaning “to the person,” argumentum ad hominem refers to an argument which relies on an attack directed at the speaker rather than the substance of the speaker’s argument. This rhetorical strategy is often fallacious in nature, employing an approach designed to discredit the character, substance or motive of a person in lieu of deconstructing the person’s claims.

- Speaker 1: I think the idea of a moral law requires the existence of a lawgiver (i.e. God).

- Speaker 2: Of course you would say that. You’re a Christian. Why should we listen to you?

- Speaker 1: I think marijuana should be legalized. It would be better for the country if we didn’t have this drug war.

- Speaker 2: Of course you think that. You’re a pothead.

- Speaker 1: No fault divorce has proven to be detrimental to society and the family.

- Speaker 2: You didn’t seem to think that when you got divorced.

- Speaker 1: We should have single payer, government funded health care. That would be the best solution to the health care crisis in our country.

- Speaker 2: You voted for Bernie Sanders. You’re probably a communist.

Fun Fact: An ad hominem observation is not always fallacious. If the qualities attributed to the speaker are provable and relevant to the argument, an ad hominem observation may be a useful point of strategy. For instance:

- Speaker A: Private health insurance is the only way to ensure the equal distribution of resources to the public.

- Speaker B: As a former CEO of a private health insurance company who was convicted for falsifying performance reports, you can’t be trusted on this issue.

2. Appeal to Authority

The argumentum ad verecundiam , sometimes also called an “argument from authority,” describes an argument in which a speaker claims that their view is endorsed by a relevant authority figure. This claim of endorsement is presented as a sufficient argument unto itself, relieving the speaker of presenting any additional evidence to further their case. An alternate form of this fallacy is sometimes called the appeal to false or unqualified authority. In this case, the speaker might cite an individual with some measure of clout, but generally in an area outside the subject of the given argument. For instance, one might fallaciously cite a medical doctor’s opinion about politics simply because she is a very smart doctor.

- My philosophy professor believes in ghosts and goes to séances. She’s an intelligent, educated, person, so ghosts must be real, and spiritualism must be true.

- My minister says the Covid vaccine will cause genetic mutations. He has a college degree, and is a holy man, so he must be right.

- Aristotle thought women were inferior to men. Aristotle is one of the smartest men who ever lived, so he must be right about this.

Fun Fact: If both parties in a debate agree that the cited individual is a relevant authority figure, and that the facts stated in reference to this figure are accurately attributed, this appeal may not be fallacious. For this reason, there is some debate about whether or not the appeal to authority is always fallacious. However, in contexts such as science, where authority must be challenged in order for new findings to be yielded, any such appeal that comes without the support of empirical evidence should be dismissed as fallacious.

3. Appeal to Ignorance

Argumentum ad ignorantiam , also sometimes referred to as an “argument from ignorance,” occurs when a speaker presents an argument as fact simply because there is no readily available evidence to prove the contrary. This fallacy is based on a false dichotomy which posits that what we don’t know must not be true. This strategy incorrectly assumes that a lack of sufficient evidence is concrete proof that something can’t be true, a position which precludes the possibility that things may be unknown or even unknowable.

- No one has proven God exists, so He doesn’t.

- You can’t prove God doesn’t exist, so He does.

- We haven’t proven aliens didn’t create life on earth, so aliens created life on earth.

- We haven’t found life on other planets, so there’s no life on any other planet, anywhere.

- We haven’t found the ruins of Troy, so the city of Troy didn’t really exist.

- We haven’t found King David’s tomb, so King David didn’t really exist.

Fun Fact: Philosopher John Locke is sometimes credited with first coining the phrase in his 1690 text “On Reason.” Here, he explains that one way “men ordinarily use to drive others and force them to submit to their judgments, and receive their opinion in debate, is to require the adversary to admit what they allege as a proof, or to assign a better.”

4. Appeal to Pity

The argumentum ad misericordiam is a strategy in which one speaker appeals to the emotions of another by exploiting their feelings of guilt or pity. This strategy of debate seeks to validate one’s argument by playing on the sympathy or sensitivity of the other. The aim is to invoke an array of emotions that might cloud the individual’s ability to approach the argument in a rational way. It should also be noted though that the invocation of empathy is not by itself evidence that a fallacy has occurred. If we take, for instance, commercials which feature starving people in developing countries, the goal of invoking our pity is not to deceive but to connect real human emotion with a call to action. An appeal to any type of emotion is not by itself fallacious, but becomes fallacious when combined with a faulty premise.

- You should give me a promotion. I have a lot of debt and am behind on my rent.

- You can’t give me a C. I’ll lose my scholarship.

- I can’t take home a B in this course. My parents will be angry with me.

- If you don’t give me a passing grade, I won’t get accepted to medical school. That will break my grandmother’s heart.

- You should marry me. I know we’re not compatible, but I only have a year to live, and you’re my last chance.

Fun Fact: The appeal to sympathy is sometimes also referred to as the Galileo argument, so-named in honor of the Italian astronomer who lived out his final decade under house arrest for scientific claims that were deemed heretical by the Catholic Church. Presumably, what is meant by this attribution is that one’s sympathy for Galileo’s ordeal does not necessarily confer agreement with Galileo’s theories. There is no recorded instance in which the pioneering astronomer employed such a rhetorical strategy on his own behalf.

5. Appeal to Popular Opinion

The argumentum ad populum , also sometimes referred to as the common belief fallacy, refers to an instance in which a speaker asserts that something is true because many people believe it to be so. This is a fallacy in which the speaker, in lieu of providing evidence to support an argument, asserts that something is demonstrably true only because a majority of people believe it to be the case. Another form of this fallacy is called the bandwagon fallacy, so named for its implication that one should adopt a view or opinion (i.e. join the bandwagon) because so many others believe it to be so. One more variation, the appeal to elite status, suggests that you might want to share a view or position because it is held by an elite set of individuals. For instance, a well-known recruitment slogan “The few. The proud. The Marines.” both conferred elite status upon the Marines and in doing so, implied that you might want to join this select group.

- Most people think the world is flat, therefore it is flat.

- Most actors in Hollywood were against the war in Iraq, therefore the war in Iraq was wrong. (This is a subsection of ad populum: snob appeal. In this case, the opinion is outside the expertise of the people appealed to.)

- Most wealthy women wear Gucci, therefore Gucci items are beautiful, and worth the price. (Snob appeal: appeal to the elite.)

- Throughout history, most philosophers thought men were more rational than women, therefore this is true.

- Most people don’t think it’s wrong to eat meat, so it’s not.

- Most people believe in ghosts, so ghosts are real.

- Slavery is accepted by just about everyone in our society, so it’s ethical to keep slaves.

Fun Fact: If an argument is actually centered on matters of public or democratic interest, the appeal to popular opinion may be a logically sound strategy. For instance, if provable, you may argue that because 9 of 10 dentists recommend Crest toothpaste, your dentist is likely to view Crest as a superior brand of toothpaste. This would not be a fallacy.

6. Appeal to the Stone

The argumentum ad lapidem is a logical fallacy in which one speaker dismisses the argument of another as being outright absurd and patently untrue without presenting further evidence to support this dismissal. This constitutes a rhetorical effort to exploit a lack of readily available evidence to support an initial argument without necessarily presenting sufficient evidence to the contrary. By its very nature, Appeal to the Stone preempts further debate. It insulates itself against counter-argument by declining to present sufficient evidence to be rebutted. A fallacy relying on inductive reasoning, appeal to the stone is a particularly vulnerable fallacy in contexts where new evidence may eventually reveal itself.

- Speaker 1: Humans share a common ancestor with the chimpanzee.

- Speaker 2: No they don’t. Don’t be ridiculous.

- Speaker 1: Why am I ridiculous?

- Speaker 2: Evolution is absurd.

- Speaker 1: Why do you say that?

- Speaker 2: Well, it just obviously is. Look at apes, and then look at us. It’s just obviously an absurd theory.

- Speaker 1: Race is a social construct.

- Speaker 2: No, it isn’t. Don’t be absurd.

- Speaker 1: What’s absurd?

- Speaker 2: The idea that race is a social construct.

- Speaker 1: What’s absurd about it?

- Speaker 2: It just is.

Fun Fact: This fallacy is drawn from a pretty entertaining origin story. 18th century English writer Dr. Samuel Johnson and his future biographer, Scottish-born James Boswell , discussed a theory offered by Church of Ireland bishop, George Berkeley . Berkeley had claimed, through the concept of subjective idealism, that reality and material objects are dependent upon an individual’s perceptions. Both Johnson and Boswell were firm in their shared rejection of this idea. However, according to Boswell’s biography of Johnson , “I observed, that though we are satisfied his doctrine is not true, it is impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he rebounded from it, ‘I refute it thus.’”

7. Causal Fallacy

Also sometimes called the fallacy of the single cause, or causal reductionism, this is a logical fallacy in which the speaker presumes that because there is a single clear explanation for an effect, that this must be the only cause. This fallacy makes the incorrect and reductive assumption that one cause precludes that possibility of multiple causes. This is a false dilemma, one which requires the speaker to ignore the possibility of other overlapping explanations and to consequently draw an unwarranted connection between a perceived cause and effect.

- I go to my front porch every morning and yell, “May no tigers enter this house!” and for 20 years, not a single tiger has entered my house. My tiger prevention strategy clearly works. .

- It’s cold on a summer day. Global warming is a hoax.

- I’ve never had the flu because I take my vitamins everyday.

Fun Fact: In essence, causal fallacy is the technical term for the exceedingly common phenomenon of “jumping to conclusions.” This is simply worth noting because it is, in many ways, a natural human behavior to which we are all predisposed at one time or another—as you await the results of a medical test; ponder the whereabouts of your missing wallet; or question the reasons somebody hasn’t texted you back even though you can clearly see that the message was delivered. In other words, uncertainty and human emotion make us all vulnerable to the occasional logical fallacy.

8. Circular Argument

Circulus in probando in Latin, this logical fallacy occurs when the premise of an argument is dependent upon acceptance of the conclusion, and the conclusion is dependent upon acceptance of the argument. In other words, both the argument and the conclusion are left wanting further proof. In circular reasoning, the originating premise lacks grounding in independent evidence, and therefore brings to the discussion no further proof to support the conclusion.

- Speaker 1: You should trust the Bible because it’s the Word of God.

- Speaker 2: How do you know it’s the Word of God?

- Speaker 1: Because God tells us it is.

- Speaker 2: Where does God tell us this?

- Speaker 1: Right here, in the Bible.

- Speaker 1: Jesus was not really crucified.

- Speaker 2: How do I know that’s true?

- Speaker 1: Because the Koran says so.

- Speaker 2: How do I know the Koran is correct?

- Speaker 1: Because the Koran is the Word of God, and everything it says is true.

- Speaker 1: Because God tells us so, here in the Koran.

Fun Fact: Circular reasoning forms the basis for the famous literary phrase “Catch-22,” which is drawn from the Joseph Heller novel of the same name. According to the satirical novel, the military maintains a policy of discharging soldiers who can demonstrate insanity. However, the military also recognizes that any sane person would desire a discharge to avoid the horrors of war. Therefore, any person seeking a discharge on the grounds of insanity is logically too sane to be eligible for discharge. This absurd contradiction is what is known, according to the author, as a “Catch-22.”

9. Equivocation

Sometimes called the Motte-and-Bailey fallacy, this is a logical fallacy in which a speaker blurs the line between two distinct positions which have some overlapping qualities. By blurring this line, it becomes possible to create an association between one position which is modest (Motte), and therefore easily defended, and a position which is likely to be more extreme (Bailey), and which is therefore more difficult to defend. By equating these positions, the speaker is presenting a false equivalence, thus forcing the other speaker to move to the defense of a position which is more difficult to defend.

- Speaker 1: Did you torture the prisoner?

- Speaker 2: No, we just held him under water for a while, and then did a mock hanging.

- According to the Supreme Court, we have a right to abortion. Therefore, it is right to have an abortion. (Legal right v. morally correct)

- A slight variation on equivocation occurs when common terms are used in an argument but with different meanings. For instance:

- Speaker 1: We are using thousands of people, who are going door to door to help us spread the word about social injustice and the need for change.

- Speaker: Well then, I can’t be a part of this because I was always been taught that it’s wrong to use people.

- Motte & Bailey Fallacy (Subset of equivocation)

- Motte (easily defensible): Different cultures and individuals have different opinions on morality.

- Bailey (more controversial/radical): Morality is completely subjective, and only a matter of opinion. There is no objective morality.

Fun Fact: The term Motte-and-Bailey was coined by philosopher Nicholas Shackell , who described the phrase as a reference to medieval castle defense systems, explaining that “A Motte and Bailey castle is a medieval system of defence in which a stone tower on a mound (the Motte) is surrounded by an area of land (the Bailey) which in turn is encompassed by some sort of a barrier such as a ditch...the Bailey, represents a philosophical doctrine or position with similar properties: desirable to its proponent but only lightly defensible. The Motte is the defensible but undesired position to which one retreats when hard pressed.”

10. Fallacy of Sunk Costs

The sunk cost fallacy proceeds from the faulty logic that the expenditure of past resources justifies the continued expenditure of resources. This fallacy contradicts rational choice theory, which holds that in economics, the only rational decisions are those which are made based on future expenses, rather than past expenses. In a broader sense, this fallacy can apply to a wide range of scenarios including the sunk cost of having remained in an unhappy relationship, having engaged in a failed war, or having dedicated years to an unsatisfying job. In each case, one might commit a fallacy by determining that past commitment to any of these scenarios necessitates a continuation of the status quo.

- Our marriage is terrible, but we’ve been together so long we might as well stay together. If we get divorced, I will have wasted 30 years.

- I hate this book. It isn’t very good. I’ve started reading it, though, so I should finish it. If I don’t finish it, I will have wasted 8 hours of my life.

- Our country has been in this war for 10 years. We’re not winning, but we continue to invest time, money, and soldiers in it because of past expenditures.

Fun Fact: A “sunk cost” is essentially the opposite of “cutting one’s losses.” For instance, in a hand of poker, a player may determine that while he is likely to lose based on his cards, he has already spent too much money on the hand to fold. This is a demonstration of the sunk cost fallacy. By contrast, the same player may recognize that while he has already spent a sum of money on this losing hand, he can still fold and hold on to his remaining funds. This is called cutting one’s losses.

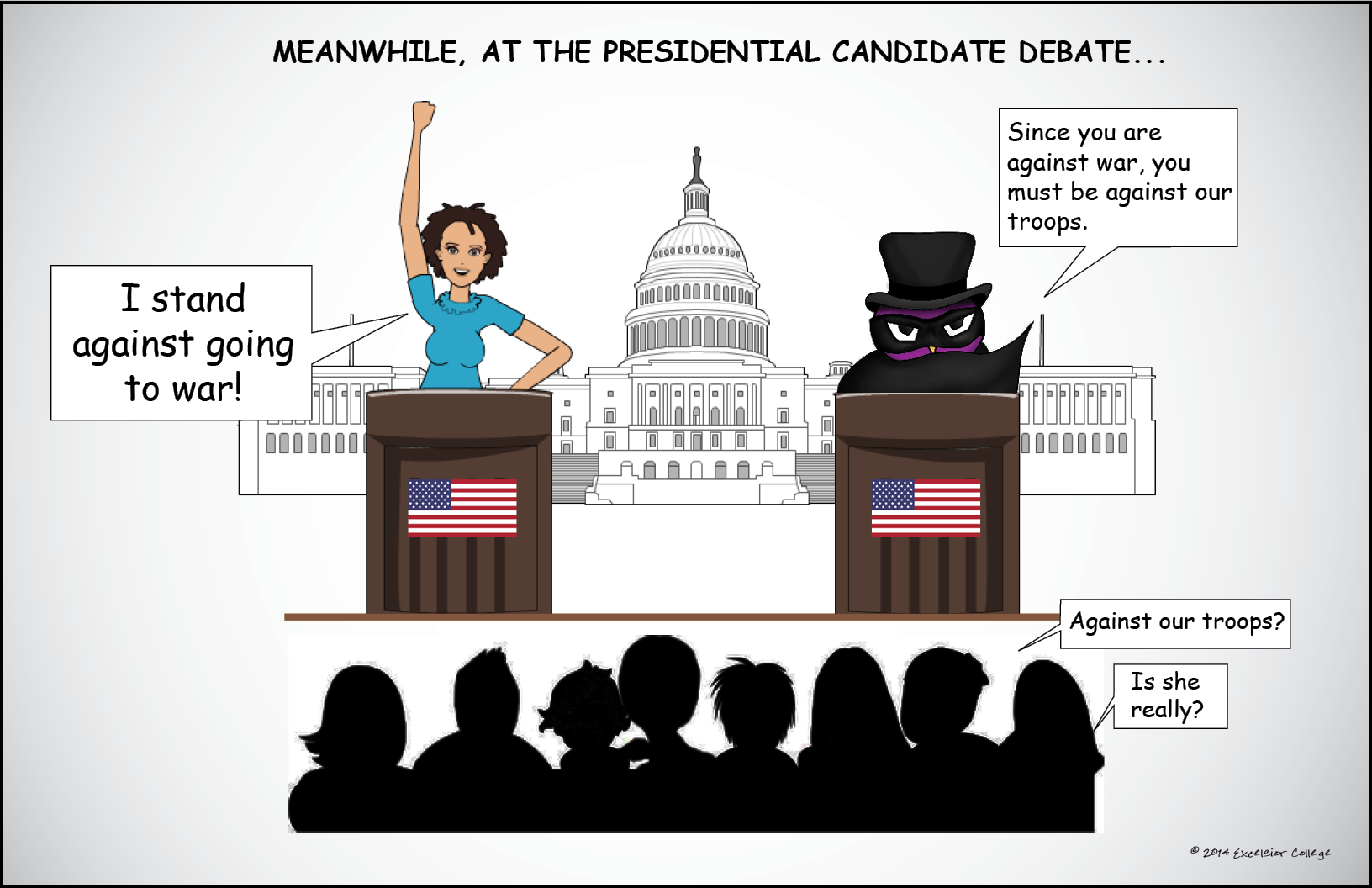

11. False Dilemma

Also sometimes referred to as a “false dichotomy,” this is a fallacy in which one incorrectly places limitations on one’s possible options in a given scenario. This fallacy rests on the false premise that one is faced with a binary choice when it’s possible that multiple options are available. In essence, this occurs when one reduces the array of available options and alternatives to a simplified either-or condition.

- If you aren’t a capitalist, you must be a communist.

- Either God created the world or evolution is true.

- Speaker 1: I’m against the war.

- Speaker 2: You must hate our troops.

- You can either support our police or Black Lives Matter.

Fun Fact: The false dichotomy conflates “contraries” with “contradictories.” With contradictories, it is true that one or the other must be true. For instance, if we say somebody is alive, it means they must not be dead, and vice versa. By contrast, contraries are statements in which, at most, one such statement must be true, but in which it is also possible that neither statement is true. For instance, if we say that somebody “is not here,” we can’t definitively conclude that the person must be at home. It’s possible that the person is at home, at the supermarket, or aboard the international space station. We don’t know. From the statement, all we can conclude is that the person is not here. The false dichotomy overlooks the full array of possibilities.

12. Genetic Fallacy

Also sometimes referred to as the fallacy of origins, this is a fallacy which presumes that an argument holds no merit simply because of its source. In this instance, the history or origin of the source is used to dismiss an argument, in lieu of using actual rhetoric to address the substance of the argument.

- Speaker 1: That scientist gave a report last week on the relationship between fossil fuel and global warming. He says burning fossil fuels contributes to global warming.

- Speaker 2: He belongs to the Sierra Club and owns stock in a solar energy company. What he says cannot be true.

- Primitive people believed in gods to explain natural phenomena. We have science, and are not primitive anymore. Therefore, there is no God.

- Speaker 1: Dr. Singh says meat eating is bad for the environment.

- Speaker 2: He’s a Sikh. They don’t eat meat. Of course he would say that. He can’t be telling the truth.

Fun Fact: In one of the earliest recorded cases of usage, author Mortimer J. Adler characterized this fallacy as “the substitution of psychology for logic.”

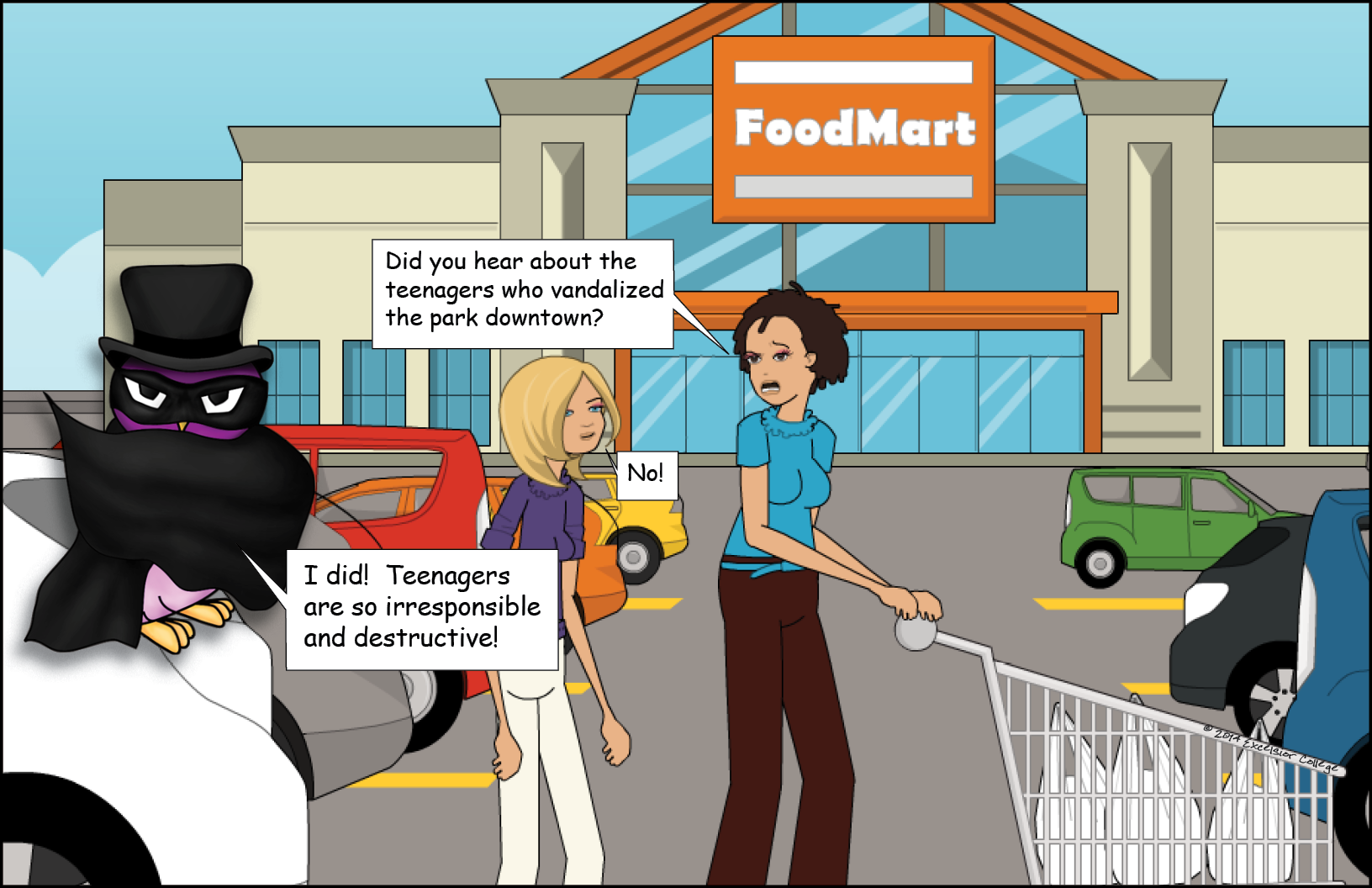

13. Hasty Generalization

Also sometimes called a faulty generalization, this is a form of argument which arrives at a conclusion about numerous instances of a phenomenon based on evidence which is limited to only one or a few instances of said phenomenon. This denotes that one might attempt to generalize the explanation for an occurrence based on an unreliably small sample set.

- My grandmother smoked for 80 years and died at 100. Obviously, smoking isn’t harmful.

- I know five people from Kentucky. They are all racists. Therefore, Kentuckians are racist.

- My neighbor’s child was kidnapped while playing alone in her yard. My city must be a dangerous place for children.

- I know four poor families. They are lazy drug addicts. Therefore, all poor people are lazy drug addicts.

Fun Fact: The hasty or faulty generalization is the fallacy which is most at play when we apply stereotypes to full demographic groups based on anecdotal evidence or limited interaction with only select representation from that group. For instance, a person who owned a pet cat with a bad temper might make the stereotypical generalization that all cats have bad tempers.

14. Loaded Question Fallacy

A loaded question is one in which the speaker has employed rhetorical manipulation in order to limit the possible array of answers that another speaker can rationally provide. The fallacy is couched in the phrasing of such a question, which presupposes certain facts that may not be true or proven, within the content of the question. The fallacy occurs when that question is underscored by a presupposition which is not agreed upon by the person to whom the question is posed.

- Have you stopped beating your wife?

- Why did you steal my keys?

- Are you one of those stupid religious people that reject science?

Fun Fact: This form of fallacy is distinct from “begging the question,” which presumes the conclusion before the question is answered. By contrast, this strategy traps the respondent into admitting a fact which is implied by the question. Simply by virtue of answering the question, the respondent has unwittingly conceded the point.

15. Post Hoc Fallacy

In full Latin phrasing, Post hoc ergo propter hoc means “after this, therefore because of this.” Instances of this fallacy occur when one incorrectly attributes a cause and effect relationship between two phenomena in the absence of proof that one causes the other. The flaw in this strategy is that it draws a singular relationship between a premise and a conclusion without considering an array of variables that might disqualify the possibility of such a relationship.

- Every time we sacrifice virgins, it rains. Therefore, sacrificing virgins causes it to rain.

- Violence among teens has risen the last five years. Video game playing among teens has also risen the last five years. Therefore, playing video games causes teens to be violent.

- Every time I wear this necklace, I pass my exams. Therefore, wearing this necklace causes me to pass my exams.

- Every person who has ever drunk water has died. Therefore, drinking water causes death.

Fun Fact: A famous phrase often used as a counterpoint to the Post Hoc fallacy is that “correlation does not equal causation.” This denotes that just because two phenomena sometimes, or even frequently, appear in connection with one another does not mean that one causes the other.

16. Red Herring Fallacy

The red herring fallacy refers to an instance in which one speaker attempts to divert the attention of another speaker from the primary argument by offering a point which may be true, but which does not actually further the substance of a counterargument. So named for the implication that the odoriferous fish in question might “throw one off the scent” of the actual argument itself, the red herring will typically support a conclusion with a fact which does not actually provide substantive support.

- Child: This fish tastes funny. I don’t want to eat this.

- Parent: There are children starving in Africa. Eat your dinner.

- Speaker 1: I think it’s terrible that a game hunter killed Cecil the lion.

- Speaker 2: What about all the babies that are killed every day by abortion?

- Speaker 1: I really think we need to do something about the rising levels of poverty and homelessness in our country.

- Speaker 2: Why are you worried about poverty? Look how many children we abort every day.

Fun Fact: While the red herring can take the form of a logical fallacy, it is also a familiar literary and cinematic device which can be employed to misdirect the attention of the reader or viewer. This is a commonly employed tactic in mysteries, suspense thrillers, and other narratives that conclude with unexpected plot twists. For instance, in a murder mystery, the author might offer a number of clues implying that an innocent character is the killer while the actual killer hides in plain sight.

17. Slippery Slope Fallacy

Sometimes also called the continuum fallacy, this fallacy occurs when a speaker claims that a single step taken in a particular direction will inevitably lead to a series of subsequent and unintended events. This argument is used to draw a series of unforeseen and unprovable conclusions based on a single provable premise. The flaw in the slippery slope argument is that it typically forecasts an extreme range of likely subsequent events, thereby excluding the possibility that a series of more moderate events might play out instead.

- You smoke pot? If you keep doing that, you’ll be a heroin addict within two years.

- If we legalize pot, the next thing you know people will want to legalize meth and heroin.

Fun Fact: In the literary context, “slippery slope” is sometimes referred to as “the camel’s nose.” This refers to a metaphor taken from an allegory published by Geoffrey Nunberg in 1858, which tells the story of a miller who allows a camel to stick its nose through the doorway of his bedroom. Bit by bit, the camel moves other body parts into the room until he is entirely inside. Once this occurs, the camel refuses to leave.

18. Strawman Argument

The strawman fallacy occurs when a speaker appears to refute the argument of another speaker by replacing that argument with a similar but far flimsier premise. In essence, the speaker is “setting up a straw man” which can then be easily knocked down by a counterargument. The flaw in this rhetorical approach is that it fails to actually engage the original argument, in essence changing the subject so as to face a more manageable argument.

- Speaker 1: I think we should lower the age of sexual consent to 16.

- Speaker 2: 16 year olds are children. So, you think it’s OK for children to have sex? No, we shouldn’t lower the age of consent.

- Speaker 1: I think we should have single payer, universal, health care.

- Speaker 2: Communist countries tried that. We don’t want America to be a communist country. We shouldn’t have single payer health care.

- Speaker 1: I think we should have an expanded social safety net for the poor in our country.

- Speaker 2: So, you think we should just throw money at lazy people who don’t want to work and think they are entitled to be kept up by other people, right?

Fun Fact: In the U.K., the strawman argument is also sometimes referred to as “Aunt Sally,” so named for a pub game in which competitors will hurl sticks at a “skittle” balanced atop a post. The individual who knocks this precariously balanced object from its post is the winner.

19. Tu Quoque

Tu quoque , which translates to “you also,” is a fallacy in which one speaker discredits another by attacking their behavior as being inconsistent with their argument. This is a specious attack line because it seizes on certain characteristics presented by the speaker rather than on the merits of the speaker’s actual argument. Similar to ad hominem in that it resorts to a personal line of attack rather than a rhetorical argument, the primary distinction is that this personal attack is framed as having a direct connection to the argument itself. This framing is not designed to disqualify the speaker for who they are (as with ad hominem) but for how they act, and consequently, how this action appears to diverge from the premise of the speaker’s argument.

- Speaker 1: No fault divorce is really harmful to the family and the larger society.

- Speaker 2: Well, you must not really think that since you’re divorced yourself.

- Parent: I really don’t want you to smoke pot. It’s still illegal, and could get you into trouble.

- Child: Didn’t you smoke pot when you were my age? You must not think it’s a big deal.

- Speaker 1 (Democrat) : “Donald Trump is a known adulterer. It reflects badly on his character, and suggests he might not be trustworthy.”

- Speaker 2 (Republican) : “What about Bill Clinton? You didn’t seem to care when he cheated.”

Fun Fact: The high level of polarization in today’s American political discourse leads frequently to a form of the tu quoque fallacy referred to as “whataboutism.” This form of the fallacy occurs when one speaker, in lieu of responding directly to an argument, accuses another speaker of taking a hypocritical position. Take, for instance, a debate over gun control between a Republican and a Democrat:

- Democrat: Republicans support fewer regulations on gun ownership, which leads to more gun-related deaths in America.

- Republican: Well what about how Democrats support drug legalization, which leads to more drug-related deaths in America?

Common Formal Fallacies

20. affirming the consequent.

Sometimes also referred to as a converse error, this is a fallacy which occurs when one assumes that, because a conditional statement is true, then the converse of that statement must also be true. In such instances, this assumption is based on a failure to consider other possible antecedents which might also be used to offer true conditional statements. In other words, the speaker has failed to consider the full range of possible conditions for that which is consequent.

- If Hunter was human, he would be mortal. Hunter is mortal. Therefore, Hunter is a human. (Hunter may actually be my cat.)

- If it was raining outside, it would be dark. It’s dark outside, so it must be raining. (It might be 10PM.)

- If I’m psychic, I will be able to see dead people. I see dead people, therefore I’m psychic. (I might actually just be insane.)

21. Affirming the Disjunct

In the case of Affirming the Disjunct, also sometimes referred to as the false exclusionary disjunct, it is incorrectly presumed that an “or” condition excludes the possibility that “either/or” could be true. In other words, when a speaker makes a statement indicating “A or B,” the fallacy occurs when the responding speaker assumes “A, therefore, not B.” This is a fallacy of equivocation in which one assumes that because one disjunct is true, the other must be untrue.

- Gus is Christian or Gus is politically liberal.

- Gus is a Christian.

- Therefore, Gus is not politically liberal.

- Either God created the world or evolution happened.

- Evolution happened.

- Therefore, God did not create the world.

Fun Fact: Whereas Affirming the Disjunct is a logical fallacy, it should not be conflated with the disjunctive syllogism which is actually a valid form of argument. An example of an accurate disjunctive syllogism states the following:

- Bruce is American, or he is not from New Jersey.

- Bruce is not American, therefore, he is not from New Jersey.

This is a valid form of inference.

22. Appeal to Probability

The possibiliter ergo probabiliten refers to a fallacy in which one conflates possibility with probability, or in which one conflates probability with certainty. At the heart of this inductive fallacy is the error in presuming that because there is evidence that a thing is possible, one can take for granted either its probability or its certainty.

- It is possible aliens built the pyramids. Therefore, aliens built the pyramids.

- It is possible to fake the moon landing through special effects. Therefore, the moon landing was a fake using special effects.

- It’s possible to pass the class without attending regularly. Therefore, you will pass even if you don’t attend regularly.

Fun Fact: Murphy’s Law famously states that anything which can go wrong, will go wrong. This is a playful and purposeful manifestation of the Appeal to Probability Fallacy.

23. Argument From Fallacy

Also redundantly known as the fallacy fallacy, this fallacy occurs when one speaker identifies a fallacy in the argument of another and uses it in order to assert that the conclusion must be false. This fallacy incorrectly assesses that a fallacy within the argument of another necessarily precludes the possibility that the argument’s conclusion is correct.

- Speaker 1: If Hunter was human, he would be mortal. Hunter is mortal. Therefore, Hunter is a human.

- Speaker 2: You just committed the fallacy of affirming the consequent. Therefore, Hunter is not a human.

- Speaker 1: Single payer health care would be the fairest and most efficient way of giving medical care to our citizens.

- Speaker 2: You must be a communist.

- Speaker 1: You just committed the ad hominem fallacy. Therefore, I’m not a communist.

Fun Fact: This fallacy is a special form of the formal “Denying the Antecedent” fallacy. (See below.)

24. Conjunction Fallacy

In a conjunction fallacy, one assumes that a set of specific and combined conditions is likelier to be true than a single condition, without concrete evidence that either is true. In this instance, the specific set of conditions may appear to be more true because it seems to represent certain facts that seem likely to connect with the premise. However, because these conditions are more specific and because these conditions combine multiple factors which must all be true in order for the entire statement to be true, it is mathematically less likely that the statement is true than would be a simpler proposition.

Classic Example: The Linda Problem

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

- 1. Linda is a bank teller.

- 2. Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

If you chose #2, you have committed the conjunction fallacy. The probability of them both being true is less than or equal to the probability of only one being true. We do not know, in fact, whether either of them is true.

Fun Fact: This fallacy is sometimes called the “Linda problem,” following from the first known example supplied by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman .

25. Denying the Antecedent

Sometimes also referred to as the fallacy of the inverse, denying the antecedent occurs when one deduces that because a valid premise leads to a valid conclusion, that the inverse can’t be true. In this case, the fallacy occurs when an individual presumes that because a premise and conclusion are true, the opposite of that premise must inherently mean that the conclusion is not true. In other words, one may make the valid statement that “If A, then B.” It would be a fallacy to determine that “If not A, then not B.”

- If you live in Kentucky, you love horses.

- You don’t live in Kentucky.

- Therefore, you don’t love horses.

- If you’re a hippie, you smoke weed.

- You are not a hippie.

- Therefore, you don’t smoke weed.

- If you are a communist, you believe in socialized medicine.

- You are not a communist.

- Therefore, you do not believe in socialized medicine.

Fun Fact: An argument based on denying the antecedent may actually be valid if the biconditional terminology is added to indicate “if and only if.” For instance:

- If and only if tomatoes grow on trees, then tomatoes must be fruit.

- Tomatoes don’t grow on trees. Therefore, tomatoes are not fruit.

26. Denying a Conjunct

This fallacy occurs under the condition that two premises cannot both be true at the same time. Under said condition, it is incorrect to presume that because A is not true, then B must be true. The primary flaw in this presumption is the preclusion of the possibility that neither premise is true.

- It isn’t both sunny and raining.

- It isn’t sunny.

- Therefore, it’s raining.

- Teena is not both a hippie and a communist.

- Teena is not a hippie.

- Therefore, Teena is a communist.

- I can’t be a pothead and get a job at the factory.

- I’m not a pothead.

- Therefore, I can get a job at the factory.

Fun Fact: The conclusion of the sequence need not be false in order for Denying a Conjunct to be a logical fallacy. In the example above, it is possible that the speaker could get a job at a factory. But we can’t presume that this is the case simply because the speaker isn’t a pothead. It’s possible, for instance, that regardless of whether or not the speaker smokes pot, this individual lacks the training to be hired as a factory worker.

27. Existential Fallacy

Also sometimes called existential instantiation, this fallacy occurs when one makes an argument about a category without first presenting any proof that such a category exists. In other words, it is not logical to attribute characteristics to that which doesn’t exist. Therefore, an argument which simply assumes existence while attributing such characteristics is based on an unproven premise.

- All sea creatures live in the water.

- All mermaids are sea creatures.

- Therefore, some mermaids live in the water.

(The problem here is that you may have a category of things that actually do not exist. What if there are no mermaids?)

- All cats are aliens. All aliens are dangerous. Therefore, some cats are dangerous. (What if cats didn’t exist?)

Fun Fact: “All trespassers will be prosecuted” is an oft-used existential fallacy, one which fallaciously assumes without evidence that there are trespassers even though we can’t presume the existence of trespassers based on the information provided in the statement. This fallacy can be readily corrected when one adds the condition “if such-and-such exists.” Thus, while it would not fit so elegantly on a posted sign, it would not be a fallacy to say, “If trespassers are found on my property, they will be prosecuted.”

28. Fallacy of the Undistributed Middle

Referred to in Latin as non distributio medii , this fallacy is considered a syllogistic fallacy. A syllogism is a kind of argument which occurs when two propositions are asserted to be true and, therefore, may allow one to arrive at a particular conclusion through deductive reasoning. A syllogistic fallacy occurs when there is a logical flaw in either or both propositions which prevents one from deducing this conclusion. With the undistributed middle, a fallacy occurs when a “middle term,” which is needed to reach the desired conclusion, is not included in either of two propositions.

- All students carry backpacks.—(Z is B)

- My grandfather carries a backpack.—(Y is B

- Therefore, my grandfather is a student.—(Y is Z)

A valid form of this argument would be as follows:

- All students carry backpacks.—(Y is B)

- My grandfather is a student.—(Z is Y)

- Therefore, my grandfather carries a backpack.—(Z is B)

Fun Fact: Technically, all fallacies of the Undistributed Middle are actually fallacies of either Affirming the Consequent or Denying the Antecedent. The primary distinction is that the fallacy of the undistributed middle may actually be corrected by distributing the middle, as it were. For instance, the following would be considered a fallacy:

- All billionaires are astronauts.

- Jeff Bezos is an astronaut.

- Therefore, Jeff Bezos is a billionaire.

- Everyone who is an astronaut is a billionaire.

By adding the third statement in this sequence, we have provided the “middle term” which may then be distributed to the conclusion.

29. Masked-man Fallacy

Sometimes also called the epistemic fallacy, this occurs when one assumes that because one object has a certain property, and the other does not have this property, that they cannot be the same thing. This is a fallacious assumption because it concludes that one’s knowledge of the object is equivalent to the object itself. It erroneously precludes the possibility that the object in question has some properties which are unknown to the subject.

- I know who my father is.

- I don’t know who the masked man is.

- Therefore, the masked man cannot be my father.

- I know who my husband is.

- I do not know who the robber is.

- Therefore, my husband cannot be the robber.

Fun Fact: The Masked-man Fallacy is actually an illicit use of Leibniz’s law. According to the law proposed by the German logician, if A is the same as B, then A and B share the same properties and are therefore indiscernible from one another.

30. Non-Sequitur Fallacy

Technically, a non sequitur is any invalid argument where a given premise does not logically support the given conclusion. In this way, the phrase non sequitur is practically synonymous with the word fallacy. However, in the context of a discussion on formal fallacies, a non-sequitur is a statement in which the premise has no apparent relationship with the conclusion, and therefore cannot be used to ascertain that this conclusion is true.

- I dated a lawyer. All he talked about was work. Lawyers are boring.

- My last boyfriend was really mean to me. All men are abusive.

- People like to walk on the beach. Beaches have sand. We should put sand on the floor in our living room.

Fun Fact: A non sequitur is also a commonly used device in literature and especially comedy. Here, by pairing an expected premise with an unexpected and technically fallacious conclusion, a comedian may offer an absurd and humorous observation. Take, for example, this observation from stand-up comedian Steven Wright:

- “I saw a sign: ‘Rest Area 25 Miles.’ That’s pretty big. Some people must be really tired.”

If you need to prepare for a debate, but feel clueless about how to even take notes in class, check out our guide to effective note-taking .

If you’re fascinated by the mechanics of logic, you may be naturally predisposed to the philosophy discipline. The list above really only scratches the surface on deeply intertwined subjects like logic, reason, and rhetoric. Check out these resources and rankings when you’re ready to plunge beneath this surface:

- How to Major in Philosophy

- What Can I do With a Master’s in Philosophy

- Five Reasons You Should Take Logic in Your First Year of College

- Top Influential Philosophers Today

- 25 Most Influential Philosophy Books

Find additional study resources with a look at our study guides for students at every stage of the educational journey.

Or get valuable study tips, advice on adjusting to campus life, and much more at our student resource homepage .

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Logical Fallacies

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.