Teaching & Learning

- Education Excellence

- Professional development

- Case studies

- Teaching toolkits

- MicroCPD-UCL

- Assessment resources

- Student partnership

- Generative AI Hub

- Community Engaged Learning

- UCL Student Success

Researching your teaching practice: an introduction to pedagogic research

What is pedagogic research, why should you do it and what effect can it have on your academic career?

1 August 2019

The Academic Careers Framework at UCL recognises that education activities which support students to learn can strengthen an application for promotion. This includes contributing to pedagogic research.

When applying for UCL Arena Fellowships (nationally recognised teaching awards accredited by the Higher Education Academy), contributing to pedagogic research is recognised in the UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) as an area of activity [A5] and as a professional value [V3].

At the heart of both the UKPSF and pedagogic research is a philosophy of reflective practice, dissemination of research, engagement of students, and attention to disciplinary specificity.

- The Academic Careers Framework at UCL

- The UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF)

What pedagogic research means

Also known as the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), or education enquiry, pedagogic research is an established field of academic discourse involving carefully investigating your teaching practice and in turn developing the curriculum.

It requires a systematic and evidence-based study of student learning, often through a small-scale research projects engaging students.

Pedagogic research is a form of self-study, and/or action research involving critical reflection and reflexivity on current practice, which gives way to new knowledge. It encourages investigating learning, including what works and what does not.

As with any rigorous research endeavour, you will need to be well-informed and critically reflective.

Pedagogic research has the goal of improving the quality of education locally and further afield, through dissemination of best practice to colleagues at UCL and beyond, in conferences and in either discipline-specific education journals or education-focused journals.

Pedagogic research brings together key objectives in UCL’s Education Strategy , by encouraging:

- active connections between education and research

- reflection on and development of our education provision

- connections between staff and students in partnership to improve education.

Pedagogic research allows educators to examine their own practice, reflect on successes and challenges, and share experiences so others can learn from this, improving education more widely.

Consider aligning your research to UCL’s education strategy

A number of pedagogic research projects focus on research-based education , specifically through uncovering answers to the following:

“What kinds of impact, if any, does UCL’s research-based education strategy (Connected Curriculum) have on changing real practice within and across the disciplines, at UCL and beyond?”

- Contact [email protected] to find out more and get involved in this research.

Pedagogic research will support a community of scholars

Making transparent how learning is possible and developing practice may well involve collaboration with students in research activities and data collection. Students are well-suited to be co-researchers on pedagogic research projects.

Engaging with the existing body of scholarship will position your work in a larger field and allow you to contribute to the community while learning from others.

Finally, sharing your findings in public forums to help others develop practice will support community-based and shared knowledge construction.

Pedagogic research resembles rigorous disciplinary research

“ “You spend some time looking at different approaches to teaching and learning within a specific field of knowledge and about learning in general in that area. You research how the knowledge is known and practised and applied within the discipline and you consider what others have done and then you plan your program and you monitor the results and improve it. It is also about writing about it and communicating it to others in the larger arena. You communicate what you do locally so other students within the discipline or profession can be helped to learn and more can be known about how the learning is achieved and how thinking and knowledge is structured in the areas. It’s about reflective practice and it’s about active dissemination of that practice for the benefit of learning and teaching.” (Trigwell et al. 2000: 167)

Subject disciplines have distinctive approaches to conducting research into education.

6 key steps to develop your own pedagogic research project

1. identify the problem and set clear goals.

Identify the focused problem you wish to consider. You may already know the intervention or practice you would like to improve, but it is important to have clear goals in mind.

You may focus on overcoming a challenge you face in your education practice. Taking a problem-based approach will make connection between pedagogic research and discipline-specific issues. For example, you could focus on massification and large class teaching, or developing cross-cultural understanding in diverse political science courses.

A helpful place to start is to identify a gap in the existing pedagogic research.

It’s also useful at this early stage to begin thinking about potential audiences for disseminating your work. This will allow you to strategically frame the project in line with what stakeholders need to know; demonstrating the initiative has value will make the work more publishable and relevant to your career development.

- What do I want to know about student learning in my discipline and/or how do I want to develop it?

- What do I want to do to develop my practice?

- Who will I communicate my findings to?

- How will this goal advance the work of other scholars?

2. Prepare adequately and begin to implement your development

You’ll want to be as prepared as possible.

Conducting a literature review relevant to your discipline and education context will help ensure your project has not already been done and help you refine the study and methodology.

Begin to implement your enhancement activity, for example through revising rubrics, assessment criteria or learning activities.

Avoid conducting a controlled experiment, where only some students receive the benefit of development.

Set a research question that allows you to explore, understand and improve student learning in specific contexts.

Discuss your plans with colleagues and students. Consider engaging collaborators.

Find out if an ethics application is required. At UCL, education research is generally considered ‘low-risk’, involving completing a simple ‘low risk’ ethics application form for Chair’s review. Allow on average two weeks for review.

As part of the application process a participant information sheet and consent form need to be produced if you are recruiting participants to your study. Data protection registration is required only if you are using ‘personal data’.

- What will my students learn and why is it worth learning?

- Who are my students and how do students learn effectively?

- What can I do to support students to learn effectively?

- What does the literature tell me about this issue?

- What activities will I design to improve education?

- What ethical implications are there?

- How will I measure and evaluate the impact of my practice on student learning?

The British Educational Research Association (BERA) offers a wealth of information on ethics in their online guide.

3. Establish and employ appropriate methods of enquiry

In order to investigate changes to education practice, a range of methods could be employed, including:

- reflection and analysis

- focus groups

- questionnaires and surveys

- content analysis of text

- Ethnography

- Phenomenography

- observational research and speculation.

Capturing students’ views are important; they will value the opportunity to be involved in improving education at UCL.

Treat your programme as a source of data to answer interesting questions about learning: collect data available at your fingertips.

Your colleagues may also be able to contribute to the research.

Be sure to gain participants’ consent.

- What methods do I need to employ to measure my practice?

- Who will I engage?

- What are my students doing as a result of my practice?

For more on methods:

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Educatio n. London: Routledge.

- Stierer, B. and Antoniou, M. (2004). Are there distinctive methodologies for pedagogic research in higher education? Teaching in Higher Education 9, no. 3: 275–285.

4. Evaluate results

Analyse your data using appropriate strategies.

Draw appropriate conclusions and critically reflect on your findings and intervention.

Return to earlier stages if further development or data collection is needed, before continuing with the project.

How has student learning changed as a result of my practice and what evidence do I have?

- What lessons have I learned?

- What adjustments have been made to my teaching?

5. Prepare your presentation

Begin to write up your work, presenting the evidence and results of your intervention.

Use the evidence you gathered to design and refine new activities, assignments and assessments for further iterations. Be critically reflective.

- What worked and what did not go according to plan?

- What can others learn from my project?

- How has enhancement developed student learning?

- What makes my intervention worth implementing?

6. Share your project with others

Go public with your project and communicate your findings (whether work-in-progress or complete) with peers, who can comment, critique and build on this work.

Engage your students in the work and invite feedback.

Share results internally (at teaching committees, or in reports), across UCL (at the UCL Education Conference , or a UCL Arena event ), or internationally (in open-access publications, and through conference presentations).

More dissemination ideas can be found below.

- What can engaging others tell me about this development?

- What impact does my work actually have on others interested in developing their practice?

This may lead to you examining the medium and long-term impact of the education development project.

Engaging multiple stakeholders over a long period of time may result in returning to step 1, through another iteration of development.

How to disseminate your pedagogic research

Sharing your findings and intervention is an important part of pedagogic research.

Look to disseminate through the following forums.

With the UCL community

- Local teaching committees.

- Faculty education events.

- Write a case study for the UCL Teaching & Learning Portal .

- Propose to deliver an Arena event . Submit a proposal if you'd like to run an event by completing the form (word document) or emailing [email protected] .

- Present at the annual UCL Education Conference .

At a higher education conference

Within the uk.

- Assessment in Higher Education

- British Educational Research Association

- Higher Education Academy Annual Conference

- Higher Education Conference & Exhibition

- Society for Research into Higher Education

- Staff and Education Development Association

- Universities UK

Wonkhe has a calendar of many major UK events and conferences.

Outside the UK

- Educause (Information Technology in Higher Education, USA)

- Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australia

- International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (Canada)

Through publication

In a pedagogy-based book series:

- Palgrave’s Critical University Studies Series

In a higher education journal, cross-disciplinary or discipline-specific:

- Active Learning in Higher Education

- Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education

- Studies in Higher Education

- Teaching & Learning Enquiry

The IOE, UCL's Faculty of Education and Society website has an updated long list of journals, both cross-disciplinary and discipline-specific.

Successful pedagogic research

Projects with maximum impact:

- investigate learning processes

- partner with students in the research and education development

- engage the body of pedagogic research

- critically reflect on changes

- are relevant to a wide audience

- communicate through open-access forums.

“ Teaching is the most impactful thing we do as academics in higher education. The sheer number of students we encounter and influence over our careers is incredible. Pedagogic research (SoTL) offers an opportunity for us as academics to refine our practice and to generate understanding through evidence of what works and doesn’t in student learning. In a research intensive institution, like UCL, pedagogic research offers us the chance to link the teaching and learning space more clearly with our research agendas, whilst at the same time contributing to opening up new opportunities to foster student learning.” David J. Hornsby, Deputy Head of Department (Education), UCL STEAPP

An example of pedagogic research at UCL

“Recognising that students could better engage with core writing concepts through acting like a teacher, I designed peer review exercises to follow draft submissions of work, as part of a module I coordinate in The Bartlett School of Architecture. After consulting the literature, I realised that there was very little by way of guidance on how to set this up.

Following the implementation phase, I held a focus group with students to find out their views, which were overwhelmingly positive. This enhancement project also improved students’ marks. I published this work and placed it on the module reading list, which helps underscore the value of this pedagogic tool and makes transparent the learning process.” Brent Carnell, UCL Arena Centre for Research-based Education and The Bartlett School of Architecture

- Carnell, B. (2016). Aiming for autonomy: Formative peer assessment in a final-year undergraduate course . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 41, no. 8: 1269–1283.

Case studies of interest on the Teaching & Learning Portal:

- A hybrid teaching approach transforms the functional anatomy module

- Novel assessment on anatomy module inspires reconfiguration of assessment on entire programme

- Peer instruction transforms the medical science classroom

Where to find help and support

The following initiatives and opportunities are available to colleagues to support research:

- Meet with colleagues experienced in pedagogic research, including from the IOE or the Arena Centre for Research-based Education.

- Funding from UCL ChangeMakers to work in partnership with students to develop education.

- Funding from the Arena Centre for Research-based Education. Sign up to the monthly newsletter to hear about the latest funding opportunities.

- A Guide to Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL), Vanderbilt University

- International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning resources

- Early-career researcher information and resources from the British Educational Research Association (BERA)

- Bass, R. (1999). “ The scholarship of teaching: What’s the problem? ” Inventio: Creative Thinking about Learning and Teaching 1 (February), no. 1.

- Boyer, E. (1990). Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate . Princeton, New Jersey: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Cleaver, E., Lintern, M. and McLinden, M. (2014). Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Disciplinary Approaches to Educational Enquiry . London: Sage.

- Fanghanel, J., McGowan, S., Parker, P., McConnell, C., Potter, J., Locke, W., Healey, M. (2015). “ Defining and supporting the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL): A sector wide study .” York, UK: Higher Education Academy.

- Felten, P. (2013). “ Principles of good practice in SoTL .” Teaching & Learning Inquiry 1, no. 1: 121–125.

- Fung, D. (2017). “ Strength-based scholarship and good education: The scholarship circle. ” Innovations in Education and Training 54, no. 2: 101–110.

- Greene, M. J. (2014). “ On the inside looking in: Methodological insights and challenges in conducting qualitative insider research .” The Qualitative Report 19, no. 29: 1–13.

- Healey, M. (2000). “ Developing the scholarship of teaching in higher education: A disciplinebased approach .” Higher Education Research & Development 19, no. 2: 169–189.

- Healey, M. Resources from Professor Mick Healey (Higher Education Consultant and Researcher) - a range of resources including bibliographies and handouts.

- Healey, M., Matthews, K. E., & Cook-Sather, A. (2019). Writing Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Articles for Peer-Reviewed Journals . Teaching & Learning Inquiry , 7 (2), 28-50.

- Hutchings, P. (2000). “ Approaching the scholarship of teaching and learning .” In Opening Lines: Approaches to the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, by P. Hutchings, 1–10. Mento Park: The Carnegie Foundation.

- Hutchings, P., Huber, M. and Ciccone, A. (2011). The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Reconsidered . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Koster, B. and van den Berg, B. (2014). “ Increasing professional self-understanding: Self-study research by teachers with the help of biography, core reflection and dialogue. ” Studying Teacher Education 10, no. 1: 86–100.

- O’Brien, M. (2008). “ Navigating the SoTL landscape: A compass, map and some tools for getting started .” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 2 (July), no. 2: 1–20.

- Rowland, S. and Myatt, P. (2014). “ Getting started in the scholarship of teaching and learning: A “how to” guide for science academics .” Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education 42, no. 1: 6–14.

- Tight, M. (2012). Researching Higher Education. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

- Trigwell, K., Martin, E. Benjamin, J. and Prosser, M. (2000). “ Scholarship of teaching: A model .” Higher Education Research & Development 19, no. 2: 155–168.

This guide has been produced by UCL Arena . You are welcome to use this guide if you are from another educational facility, but you must credit UCL Arena.

Further information

More teaching toolkits - back to the toolkits menu

Learning and Development at UCL

Academic Careers Framework

Gain recognition for your role in education at UCL. There are pathways for teaching staff, researchers, postgraduate teaching assistantsand professional services staff:

Arena one: for postgraduate teaching assistants (PGTAs) - enables you to apply to become an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA).

Arena two: for Lecturers and Teaching Fellows on probation - enables you to apply to become a UCL Arena Fellow and Fellow of the HEA.

Arena open: for all other staff who teach, supervise, assess or support students’ learning at UCL - accredited by the HEA.

Sign up to the monthly UCL education e-newsletter to get the latest teaching news, events & resources.

Professional development events

Funnelback feed: https://search2.ucl.ac.uk/s/search.json?collection=drupal-teaching-learn... Double click the feed URL above to edit

Education news

Funnelback feed: https://cms-feed.ucl.ac.uk/s/search.json?collection=drupal-teaching-lear... Double click the feed URL above to edit

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Research methods in teacher education: meaningful engagement through service-learning.

- 1 Department of Education and Centre for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 2 Ecological Economics & RCE Vienna, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria

- 3 Centre for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Competence in research methods is a major contribution to (future) teachers’ professionalism. In the pedagogical approach presented here, which we call the Teaching Clinic, we combine service-learning and design-based research to create meaningful learning engagements. We present two cases to illustrate the objectives, processes, and outcomes of the service-learning projects and reflect about both in terms of learning and service outcomes. This includes discussions of how this pedagogical approach led to motivation and engagement, how principles of transfer of training are obeyed, and what this means quite generally for school-university relationships.

Introduction

Research skills, such as the knowledge and skills necessary to pose clear (scientific) questions, to critically review the literature, and to collect, analyze, and interpret data, are important to navigate the complexity of daily life. This is also true for teachers, where research skills and increasingly seen as important elements of professionalism ( Amirova et al., 2020 ) and the establishment of evidence-based teaching practices ( Burke et al., 2005 ). In this article, we aim to present case studies of a pedagogical approach that helps in increasing the perceived relevance of discussing methodological issues within teacher education ( Davidson and Palermo, 2015 ): the Teaching Clinic (TC).

TCs are designed as semester-long courses in which teachers in training (now “students”) collaborate with practicing teachers (now “teachers”) on pedagogical innovations in the teachers’ classrooms through design-based research ( Bakker, 2018 ). They can be seen as instances of service learning in the domain of teacher education ( Stoecker, 2016 ). TCs tackle the combined needs of students, such as the wish for more formal experiences directly in the school-context and obtaining well-transferable competences and knowledge, and teachers, who may want a more direct access to state-of-the-art knowledge and support in implementing pedagogical innovations.

The objective of this article is to present the pedagogical approach taken in the TC and to explore its outcomes in terms of research competence and service through the accounts of stakeholders to the TC. Specifically, we present two exemplary projects that were conducted within the TC and showcase the reflections from students, teachers, and the course facilitators.

Context and Frameworks

The Teaching Clinic (TC) is a course for Master students in a teacher education curriculum at an Austrian university. Established teachers submit research questions about current professional challenges. These questions are then picked up by students, who conceptualize and execute research projects to find evidence based solutions.

The primary objective of doing research at this very local and practical level is to instill a scientific mindset in the students. Research skills are increasingly seen as tools of the professional practice; not as something confined to academic research. Importantly, this perspective is not only shared with the students that work on the projects, but also with the teachers that submit them. In that sense, the TC is about the transfer from university to practice (see also the current debate about “Third Mission”; Schober et al., 2016 ).

In terms of research methods, two secondary objectives of the format exist. First, the TC presents a clear purpose, and, therefore, motivation, to apply research methods. Second, the students apply research methods in a context that is almost identical to the context of their later work. This facilitates the transfer from the training context to the subsequent professional work as teachers ( Blume et al., 2010 ; Quesada-Pallarès and Gegenfurtner, 2015 ).

Main Pedagogical Approach: Service-Learning

The main pedagogical frame used to conduct the TC was service-learning ( Sotelino-Losada et al., 2021 ). There are numerous definitions of service-learning, but perhaps the most cited is the one formulated by Bringle and Hatcher (1995) , who define service-learning as a

“...course-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students (a) participate in an organized service activity that meets identified community needs and (b) reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of course content, a broader appreciation of the discipline, and an enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility” (p. 212).

Service-learning is an experience-based learning approach ( Biberhofer and Rammel, 2017 ) that combines learning objectives with community service and emphasizes individual development and social responsibility through providing a service for others; service situations are viewed as learning settings and opportunities for public engagement ( Forman and Wilkinson, 1997 ). According to Furco (1996) , the key lies in the equal benefit for providers (TC: students) and recipients (TC: teachers). The TC could also be discussed from the perspective of transformative learning ( Mezirow and Taylor, 2009 ), as the learning goal of the seminar is not about pure knowledge acquisition, but about “building the capacity of students as agents of change” ( Biberhofer and Rammel, 2017 , p. 66). The TC provides a rather open learning environment, in which students engage in an open dialogue with each other, with the teachers, and the course facilitator, who does not necessarily possess the necessary subject-matter expertize but provides feedback and guidance throughout this process of dialectic inquiry.

Useful Methodological Lens: Design-Based Research and Action Research

As stipulated above, the main objective of the TC is to implement research projects at a local level in the teaching context. One methodological perspective that is very well adapted to this aim is design-based research (DBR). DBR is a research approach that claims to overcome “the gap between educational practice and theory, because it aims both at developing theories about domain-specific learning and the means that are designed to support that learning” ( Bakker and Van Eerde, 2015 , p. 430). In DBR, the design of learning environments proceeds in a reflective and cyclic process simultaneous to the testing or development of theory. The design includes the selection and creation of interventions which is done in cooperation with practitioners, while holding only little control of the situation. This research approach aims to explain and advise on ways of teaching and learning that proved to be useful and to develop theories that can be of predictive nature for educational practice. Because of its interventionist nature, researchers conducting this type of research are often referred to as “didactical engineers” ( Anderson and Shattuck, 2012 ; Bakker and Van Eerde, 2015 ).

In the TC, we use DBR as a methodological frame to set up the projects. On a micro level, different projects feature very different data (e.g., video recordings, surveys among pupils, interviews, texts, etc.) and methods (e.g., field experiments, statistical analyses, content analysis, etc.). The students need to decide which ones to use, get appropriate data, and run the analysis.

In this section, we present how TCs are a useful context for becoming teachers to develop research competences. Since this is the very first discussion about TCs, we use case studies to explore the outcomes of this pedagogical format. The case studies presented here contain reflections of students, teachers, and course facilitators based on a set of guiding questions in the direction of research methods and service-learning. Specifically, two independent TC projects will be presented. The first project focused on implementing concepts of Education for Sustainable Development (EDS) in the context of socio-economically disadvantaged classes in the field of Science, Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology (STEM). A team of two students and two teachers collaborated to further develop and evaluate lesson plans based on classroom experience, pupils’ feedback, and expert knowledge. The second project focused on improving the feedback strategies in response to students’ writing in language classrooms. Using an experimental research design, a team of four students generated data to allow for the evidence-based improvement of personal feedback and marking strategies.

Both projects will be reflected from the angles of multiple stakeholders; the team of authors of this article include a Master student, a teacher, and a researcher (and facilitator of the course). This reflects the nature of the TC as a learning experience that is co-created by multiple stakeholders; the participating students are not just learners, but also co-researchers and pedagogical co-designers (see Bovill et al., 2016 ). In the context of this publication students not only helped by providing additional reflections and data (see Case 1), but also by taking the position as a co-author (Case 2 was written by a student of the project; the course facilitator, an experienced researcher and first author of this text, provided feedback but otherwise did not interfere in the writing process; for student faculty-student co-authoring also see Abbott et al., 2021 ). For each case, we will first describe the objectives as laid out by the submitting teacher(s), the methodological process to find answers to the questions posed, and the final outcomes as reported back to the teacher(s).

Case 1: Education for Sustainable Development for Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Classes in the Prevocational School Sector (Teacher’s View)

This first case about Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) for socio-economically disadvantaged classes in the prevocational school sector is presented from the point of view of the teacher (who submitted the problem to the TC).

The relevance of the global educational environment for social fields of action was already taken up by the United Nations (UN) before the turn of the millennium and led to the years 2005–2014 being declared the World Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (WDESD) ( Combes, 2005 ). In the German-speaking countries, the Orientation framework for the learning area “ Global Development ” serves as an essential contribution to explicit didactics for ESD in the secondary education sector ( Schreiber and Siege, 2016 ).

This pedagogical concept was used by the students to support two teachers at a prevocational school in implementing ESD didactics into Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) lessons. The aim of the curriculum was to help low-income pupils at a vulnerable prevocational school location to develop highly demanded competences in the field of STEM professions.

Another objective was to strengthen the students’ sense of responsibility for society and environment in alignment with the bottom-up drive of the “FridaysforFuture” movement. The starting point for the research needs in schools was a study conducted by the German Federal Environment Agency, which asked whether environmental protection as a motive is useful for addressing young people’s motivation to enter STEM professions more successfully than before ( Örtl, 2017 ). The results of the study imply, among other aspects, that STEM didactics have close links to ESD and that synergetic overlaps in this area seem to be a promising approach for STEM lessons at prevocational schools.

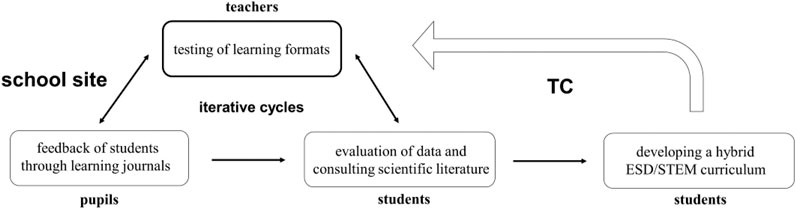

Throughout the TC, promising learning formats in STEM lessons were tested in iterative cycles of implementation, evaluation, and adjustment in the sense of DBR at the chosen school site. Here, learning journals produced by students for different learning formats in STEM lessons on the topic “Renewable Energies” and “Climate Change” served as the primary data to create a scientifically and empirically driven curriculum for motivating students to pursue STEM professions (see Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1 . Overview over the work process in Case 1.

The method of structured qualitative content analysis ( Mayring, 2014 ) was used to search for indicators that make learning formats subjectively interesting for students. The students were required to document steps and problems that occurred during the implementation and evaluate the learning opportunities on an ordinal scale from one to five after completion of the learning journal. The underlying learning formats include problem-centered films, concrete technical tasks (programming, mechanics, construction, electronics, and applied computer science), external workshops and lectures with companies from the technology sector.

After an initial review of the data, implications for the indicator “perceived as subjectively interesting by the students” could be concluded. The finding showed that individual isolated learning opportunities on the topic of climate change do not necessarily lead to the desired effect of students showing intrinsic motivation to acquire relevant professional skills for finding solutions.

Based on these interim results, the TC students consulted the scientific literature, which allowed for contextualization of socially relevant and scientific-technical dimensions in the acquisition of competencies in the sense of ESD. The framework for this approach was provided by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BWZ) and the German Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (KMK) ( Schreiber and Siege, 2016 ).

Through the continuous cycles of the DBR approach using different learning formats in ongoing school lessons, the students were able to develop a hybrid ESD/STEM curriculum step by step by evaluating the data material. Decisive input for the concrete lesson plans was derived from the indicators identified through the structured content analysis according to Mayring (2014) , which were perceived by the students as subjectively interesting and motivating. Due to COVID-19-related school closures, it was not possible to complete an annual curriculum. Nevertheless, a total of 16 lessons that met the requirements of the research assignment based on the identified indicators were designed. The curriculum created through the cooperation of school and TC now serves as a preliminary study and basis for a fully empirical main study, which is to be carried out at several school locations after the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. The results of the qualitative preliminary study were used by the students in the final step to formulate hypotheses for the main study in accordance with the underlying research question following Mayring (2014) methodological approach.

In addition to the general results of the qualitative preliminary study, various positive effects on the stakeholders could be identified in the present case as a result of the service-learning offering. The question chosen in the case study whether environmental protection issues can contextually contribute to motivating young people in STEM classes to take an interest in related professions could not be fully answered. However, the DBR approach has served to identify those indicators based on different learning formats that were rated as subjectively interesting and motivating for students. As a pedagogical and didactic core concept, the approach of the “Recognize- Evaluate- Act”-principle from the Orientation framework for the learning area “ Global Development ” ( Schreiber and Siege, 2015 ) turned out to be particularly promising. Furthermore, a concrete further research assignment for the TC could be derived from the results to initiate a fully comprehensive empirical study based on pre-formulated hypotheses.

The TC research semester was described by the students as an eye-opening experience between university teaching and practical school experience. In this case, the service-learning project enabled the Master students to implement theoretically learned scientific methods in a practical way within the school environment. The scholarly exposure to ESD content along with instructional development using STEM learning opportunities gave the Master students a holistic view into practice-based teaching and learning research.

“The exchange, especially the feedback, with teaching staff at a preparatory vocational school with difficult socio-economic conditions was far more informative and practically relevant to me than most frontal lectures at the university. In addition to the practical and school-relevant part of the research semester, the TC together with ESD principles was an enriching support for me to be able to conduct current educationally relevant research in a scientifically and methodologically correct way. The balance between the cornerstones of school practice, TC and the final research work has given me a new perspective and understanding of the profession of a teacher and the different places of work.” (Student)

Furthermore, the underlying DBR approach has been identified as a promising approach for adapting hybrid ESD-STEM learning formats and teaching contents to determine successful learning effects with students.

The service-learning concept offered freed up additional resources for instructional development that would have been difficult to implement during the regular school year due to administrative duties and other teacher commitments. This gave teachers the opportunity not only to get ideas for lesson design, but also to further develop their own teaching based on sound and up-to-date scientific methodology. Learnings reportedly included new ways “to inspire the students with new approaches and to show them that STEM cannot be purely theoretical, but that it is important for them and society.”

Through the joint development of the curriculum, it was possible to link subject-related STEM lessons with social relevance, which often seems intangible for students, especially in STEM subjects. Teachers attributed great importance to this interconnection in identifying students' ability to explore, reflect, and critically evaluate scientific content from multiple perspectives.

“Experiencing values such as sustainability, environmental awareness and solidarity […] provide a good basis for developing into independent and responsible personalities.” (Teacher)

Particularly the context of teaching at a socially vulnerable school site suggests a value-oriented attitude and precise concept of learning formats next to topics that are relevant to the realities of the young people’s lives.

The composition of the student body in the underlying pre-vocational preparation school class showed a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of country of origin and socio-economic status. 90% of the students had a first language other than German and the vast majority could be classified as belonging to a deprivileged class of the population. The empowerment of being able to work on a curriculum for their future career led to increased motivation for the lessons, which could be seen in the underlying learning journals. The motivation was also reflected in an increased learning curve in STEM-related subject knowledge. Moreover, students’ involvement with environmental and social issues of the 21st century led to an observable increased interest in technical and scientific career profiles.

Case 2: Effective Feedback (Student’s View)

The second case shall illustrate the student’s perspective and is written by a student of the TC. The project had been carried out in the summer term 2020 and was conducted by a team of four students. The collaboration took place in a school in Vienna with two teachers and two lower-secondary classes of theirs.

At the beginning of the TC, we were confronted with a common problem of teachers: An English and a German teacher reported that they spend much time correcting their pupils’ assignments while suspecting that their pupils did not use the feedback for their own progress. In close exchange with the teachers and after an initial evaluation of the problem, we formulated a project goal: an invention should be set to counteract this problem and improve the situation for both learners and teachers.

As a first step, a thorough literature review was necessary to find appropriate strategies to tackle the problem. There exists a plethora of publications about feedback strategies; to narrow down our focus, we opted for the “minimal marking” approach because this strategy directly addresses both issues voiced by the teachers. As Hyland (1990) puts it very precisely:

Many teachers find marking to be a tedious and unrewarding chore. While it is a crucial aspect of the classroom writing process, our diligent attention and careful comments only rarely seem to bring about improvements in subsequent work (p. 279).

Besides Hyland (1990) , also Haswell (1983) dedicated a publication to the same issue. Both suggested minimal marking as a solution to reduce the teacher’s workload by simultaneously increasing the positive effect of the feedback. The basic principle of minimal marking is that instead of detailed feedback, only a cross or a check is set beside the line in which the mistake occurred; subsequently, it is the pupil’s task to correct his/her own text by identifying the mistakes and correcting it using prior knowledge or a dictionary (p. 600). Thus, the pupil receives as minimal information as necessary and is encouraged to edit the text independently ( Haswell, 1983 , p. 601). Through this approach, pupils shall be enabled to edit their texts without much support of the teacher or other adults, which shall help them to develop essential writing skills. This method is considered especially effective because it requires the pupil to act on the feedback received by the teacher ( Hyland, 1990 , p. 279). Although this approach is still applied nowadays ( McNeilly, 2014 ), it has received little attention in research. Due to this research gap and our personal interest in the topic as future language teachers, we ventured out to explore the effects of minimal marking on (a) learner’s mistake awareness, (b) the time teachers spend on giving feedback and (c) the quality as perceived by pupils and teachers.

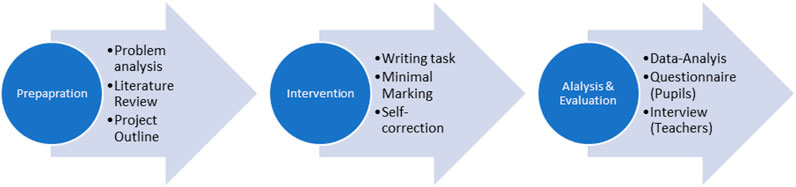

To answer these research questions, we chose a set of methods consisting of quantitative and qualitative tools (see Figure 2 ). The procedure can be described as the following: Pupils of both classes were divided in an experimental group and a control group. Then all pupils of one class were asked to write a text in response to the same task. Teachers gave feedback using their traditional method, in which they indicate every mistake and write a short comment to each one, among the control group and using the minimal marking strategy to give feedback on the texts of the experimental group. Both teachers measured the time they needed to correct every single text. Then the pupils got their texts back and edited them. Then the edited texts were collected again. Discovered and undiscovered mistakes were counted and analyzed in the texts of both groups. Time spent on correction was analyzed for each group and juxtaposed. The pupils were asked for their opinion after the experiment through an online survey which consisted of closed and open questions. Finally, the teachers shared their experience in a narrative interview, which was also conducted online.

FIGURE 2 . Experimental setup of case 2.

Although the results of this small-scale study were not statistically significant, some interesting insights could be gained. Although an increased mistake awareness among pupils could not be proved with the number of mistakes occurring in the first and second text, an increased mistake awareness can be inferred from the pupil’s answers given in the questionnaire. Several pupils highlighted the positive aspects of the minimal marking approach and considered it as (really) helpful; one of the learners summarized: “I thought more about my mistakes than I usually do and, hence, I could improve my writing skills. It was more difficult to find the mistakes, but it also helped me to get better” (translated by the authors).

Regarding the time spent for correction, an advantage of the minimal marking approach could only be detected in one of both classes. The German teacher reported an average correction time of 3:14 (first round) and 2:12 (second round) per text using the traditional method and an average time of 1:39 (first round) and 1:14 (second round) per text using the minimal marking approach. The English teacher measured similar times for both feedback strategies. Limiting factors, such as the small sample size of the project and the pupils’ unfamiliarity with the new method, need to be kept in mind when conclusions are drawn. However, this only highlights the need for further research about the effects of this specific feedback method.

Probably the most promising outcomes can be reported about the attitudes of teachers and pupils. Both teachers described the collaboration between them and the students as enriching and both want to continue the collaboration with the university. Additionally, they reported an increased interest in action research for themselves but also among their colleagues. Through the questionnaire we could also observe a positive attitude toward the experiment among pupils, which gives reason for further projects in class and to further incorporate pupils in research. And finally, we students were able to develop a deeper understanding of teacher professionalism and a more positive attitude toward the application of research in teaching. Additionally, all members of the team were convinced that they wanted to apply this method as teachers in their future practice.

As outlined above, the objectives of the pedagogical/didactical concept of the TC are to create a highly effective (co-creative) learning environment for teachers in training while at the same time delivering valuable service to practice.

Reflections on Learning

Several themes of learning emerged in the cases above. The opportunity to combine own learning with delivering a service was described as important. Being of service to someone matters and enhances the motivation of students to engage also with the methodological parts of the course. The ESD case confirms the findings of Biberhofer and Rammel (2017) derived in the context of their two-semester “Sustainability Challenge”, which has been successfully executed since 2010. Participation in real life problems increases intrinsic motivation to investigate solutions (and to apply the methods needed to carry out this investigation). The master students who carried out the minimal marking project pointed out that this collaboration enabled them to apply research methods in an authentic environment and, thus, rendered them more meaningful. Additionally, this project allowed them to engage with research methods in a demanding but motivating manner which is a frequently neglected part in teacher education. The project enabled them to practice teaching methods and evaluate them through scientific methods in a systematic way; this led to a better understanding of the vital symbiosis between research and practical teaching ( Paran, 2017 ). The exploratory case studies presented in this paper cannot give an in-depth account of the learnings processes and outcomes. Future research could seek to further explore the impact of service-learning approaches to the students’ motivation (cf. Medina and Gordon, 2014 ; Huber, 2015 ).

There are some indications that the course had a positive impact on the students’ future professionalism as teachers and their scientific attitude. In the ESD case, students’ engagement with the dimensions of ecological and social justice (which are integral components of ESD) was evident primarily at two levels. On the one hand, the professional engagement with ESD led to the desire to make its impact on students measurable through scientific methodologies. On the other hand, a reframing in the sense of transformative learning ( Mezirow and Taylor, 2009 ) about the subjective role perception as a teacher for shaping an sustainable worldview for future generations of pupils could be observed. The master students of the minimal marking project considered the collaboration with already practicing teachers as especially helpful. Firstly, this special constellation allowed them to gain practical experience besides the obligatory practicum and benefit from the teachers’ experience. Secondly, the conduction within the university context required them to combine academic research and practical teaching. This supported them in their professional development as teachers because it made them realize the importance of research methods in evidence-based teaching ( Paran, 2017 ).

Basically, having learned and experienced how to utilize research methods not just for the purpose of “pure research”, but framing it as a practice of evidence-based teaching, is expected to make teachers perform better in an increasingly VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous; Johansen and Euchner, 2013 ; LeBlanc, 2018 ) world. The COVID-19 pandemic is a case in point here. While all teachers needed to react to the changing context, not all did so in a thoughtful and effective manner ( Hodges et al., 2020 ). Different levels of professionalism and of having a scientific mindset could be a major factor in this equation. As described above, increasing this mindset was the primary objective of the course format and we hypothesize that this is an important ingredient to foster teachers’ lifelong learning ( Bakkenes et al., 2010 ; Hoekstra and Korthagen, 2011 ).

An important strategy to increase the learning outcomes for students used in the TC is to work directly in the context that the knowledge should later be applied in. Put differently, the Master students support one individual overcoming a teaching-related challenge. This similarity of contexts aids the transfer of the learnings and helps to make them more applicable ( Blume et al., 2010 ; Burns, 2008 ). Additionally, the learning process is highly social, including peers, the course facilitator(s), and the teachers. Previous research indicates that this social dimension may additionally increase the odds of “successful” learning ( Daniel et al., 2013 ; Penuel et al., 2012 ). In the ESD case, confirmation of the success of the underlying ESD/STEM concept for increasing young people’s enthusiasm for STEM careers was a transformational realization for the teachers and master’s students in the collaborative learning process. Similarly, the minimal marking group reported an unprecedented feeling of responsibility in comparison with other university courses. Because of the knowledge that their collaborating teachers and their students profited from the project, the students’ work felt meaningful and important. Simultaneously, this environment enabled them to gain experience in research methods and practical teaching which would not be possible without this unique course format.

On the other hand, students gained practical experience in non-university organizations during their studies. In the feedback, the students commented on both, gaining experience from the school context in cooperation with the teachers and the methodological and research-oriented support by the TC itself. The work at local school sites additionally motivates the students to further develop their pedagogical and didactic knowledge in a practical setting based on current school challenges. Furthermore, the interaction of the scientific approach together with the practical school experiences enables the students to internalize their own values for contemporary teaching for their future role as teachers themselves.

Reflections on Service

The teachers involved in the projects described above reported high satisfaction with the project results and an increased interest in research even extending to their colleagues. Teachers valued the opportunity to develop and improve their teaching formats and methods based on evidence and through scientific methods. Through the collaboration with students, time-consuming research could be outsourced, and the desired role of the teacher researcher could be fulfilled despite time constraints.

As shown in Figure 1 of the ESD case, the clear division of roles with clear lines of communication and distributions of action items was a major advantage in the creation and implementation of the ESD/STEM curriculum. The well-structured method of the DBR approach throughout the semester allowed for proper planning at each point in time for the scarce time resources of the various stakeholders involved during the school year. The teachers engaged in the minimal marking project also reported an increased interest in research and collaboration with the university which further extended among their colleagues. At the end of the project, they expressed their wish to continue collaboration with students of next courses to further improve their teaching. This illustrates the positive influence on the teachers’ attitude toward research and even a potential multiplying factor of the teaching clinic on teachers beyond the active participants.

Finally, the TC can function as a promising channel to maintain communication between teachers and research ( Paran, 2017 ). The collaboration between teachers working in the field and university may lead to the identification of new research gaps on the one side and more evidence-based teaching on the other. Introducing teachers to the concept of evidence-based teaching in early stages of their education may have a positive effect on their attitude toward research in teaching and be the key to the development of a professional role teacher as researcher ( Paran, 2017 ). This illustrates the close interconnections between research at university, teacher education and practicing teachers and their potential to profit from collaboration with each other.

Other Outcomes

The TC aims to create value in terms of enhancing university social responsibility ( Vasilescu et al., 2010 ). Universities play an important role in addressing global challenges, such as growing socio-economic differences, the climate crisis, or the current COVID-19 pandemic. Irrespective of the specific disciplines, the concept of university social responsibility suggests that universities should not limit themselves to research and teaching, but should commit to solving economic, social, and ecological problems. Universities play a central role in raising students’ awareness of social responsibility to help them develop into social personalities ( Bokhari, 2017 ). In that sense, special attention must be paid to teacher education for its promise of achieving multiplication effects that will eventually reach all educational levels. The principle of “Third Mission” provides a key point of reference in this context, which emphasizes the targeted use of scientific findings to deal with a wide range of societal challenges and proposes the transfer of technologies and innovations to non-academic institutions ( Schober et al., 2016 ).

The systematic approach at hand uses a university research service to address concrete issues in the local field of schooling. The benefit lies in the possibility of merging education theory with socially relevant topics from multiple perspectives. The TC initiates a sustainable circular process, which facilitates the generation of a mutual learning curve for the university system and the school system by instrumentalizing research on an evidence-based level. Thereby, the TC acts as a door opener for practice researchers with access to the otherwise difficult to access compulsory school system.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

DF designed the didactical concept and has written the conceptual part of this article. UH and KM were stakeholders to the two case studies presented in the article. Both have collected data for their case-study and offered their own reflections. All authors contributed to the overall discussion.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbott, L., Andes, A., Pattani, A., and Mabrouk, P. A. (2021). An Authorship Partnership with Undergraduates Studying Authorship in Undergraduate Research Experiences. Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education 1 (32).

Google Scholar

Amirova, A., Iskakovna, J. M., Zakaryanovna, T. G., Nurmakhanovna, Z. T., and Elmira, U. (2020). Creative and research competence as a factor of professional training of future teachers: Perspective of learning technology. Wjet 12 (4), 278–289. doi:10.18844/wjet.v12i4.5181

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anderson, T., and Shattuck, J. (2012). Design-Based Research. Educ. Res. 41 (1), 16–25. doi:10.3102/0013189X11428813

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., and Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learn. Instruct. 20 (6), 533–548. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.09.001

Bakker, A. (2018). Design research in education: A practical guide for early career researchers . Abingdon, UK: Routledge . doi:10.4324/9780203701010

CrossRef Full Text

Bakker, A., and Van Eerde, D. (2015). “An introduction to design-based research with an example from statistics education”, in Approaches to qualitative research in mathematics education . Springer , 429–466. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9181-6_16

Biberhofer, P., and Rammel, C. (2017). Transdisciplinary learning and teaching as answers to urban sustainability challenges. Ijshe 18 (1), 63–83. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-04-2015-0078

Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T. T., and Huang, J. L. (2010). Transfer of Training: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Manag. 36 (4), 1065–1105. doi:10.1177/0149206309352880

Bokhari, A. A. H. (2017). Universities‟ Social Responsibility (USR) and Sustainable Development: A Conceptual Framework. Ijems 4 (12), 8–16. doi:10.14445/23939125/IJEMS-V4I12P102

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., Felten, P., Millard, L., and Moore-Cherry, N. (2016). Addressing potential challenges in co-creating learning and teaching: overcoming resistance, navigating institutional norms and ensuring inclusivity in student-staff partnerships. High Educ. 71 (2), 195–208. doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9896-4

Bringle, R. G., and Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A Service-Learning Curriculum for Faculty. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 2 (1), 112–122.

Burke, L. E., Schlenk, E. A., Sereika, S. M., Cohen, S. M., Happ, M. B., and Dorman, J. S. (2005). Developing research competence to support evidence-based practice. J. Professional Nursing 21 (6), 358–363. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Burns, J. Z. (2008). Informal learning and transfer of learning: How new trade and industrial teachers perceive their professional growth and development. Career Techn. Educ. Res. 33, 3–24. doi:10.5328/cter33.1.3

Combes, B. P. Y. (2005). The United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014): Learning to Live Together Sustainably. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 4 (3), 215–219. doi:10.1080/15330150591004571

Daniel, G. R., Auhl, G., and Hastings, W. (2013). Collaborative feedback and reflection for professional growth: Preparing first-year pre-service teachers for participation in the community of practice. Asia-Pac. J. Teacher Educ. 41 (2), 159–172. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2013.777025

Davidson, Z. E., and Palermo, C. (2015). Developing Research Competence in Undergraduate Students through Hands on Learning. J. Biomed. Educ. 2015, 1–9. doi:10.1155/2015/306380

Forman, S. G., and Wilkinson, L. C. (1997). Educational policy through service learning: Preparation for citizenship and civic participation. Innov. High Educ. 21 (4), 275–286. doi:10.1007/BF01192276

Furco, A. (1996). Service-Learning: A balanced approach to experiential education , 7

Haswell, R. H. (1983). Minimal Marking. College English 45 (6), 600–604. doi:10.2307/377147

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., and Bond, A. (2020). The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. EDUCAUSE Quarterly 15.

Hoekstra, A., and Korthagen, F. (2011). Teacher Learning in a Context of Educational Change: Informal Learning Versus Systematically Supported Learning. J. Teacher Educ. 62 (1), 76–92. doi:10.1177/0022487110382917

Huber, A. M. (2015). Diminishing the Dread: Exploring service learning and student motivation. Ijdl 6 (1). doi:10.14434/ijdl.v6i1.13364

Hyland, K. (1990). Providing productive feedback. ELT J. 44 (4), 279–285. doi:10.1093/elt/44.4.279

Johansen, B., and Euchner, J. (2013). Navigating the VUCA World. Res.-Technol. Manag. 56 (1), 10–15. doi:10.5437/08956308X5601003

LeBlanc, P. J. (2018). Higher Education in a VUCA World. Change Magazine Higher Learn. 50 (3–4), 23–26. doi:10.1080/00091383.2018.1507370

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis. doi:10.4135/9781446282243

McNeilly, A. (2014). Minimal Marking: A Success Story. cjsotl-rcacea 5 (1). doi:10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2014.1.7

Medina, A., and Gordon, L. (2014). Service Learning, Phonemic Perception, and Learner Motivation: A Quantitative Study. Foreign Language Annals 47 (2), 357–371. doi:10.1111/flan.12086

Mezirow, J., and Taylor, E. W. (2009). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education . John Wiley & Sons .

Örtl, E. (2017). MINT the gap – Umweltschutz als Motivation für technische Berufsbiographien? Umweltbundesamt . https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/mint-the-gap-umweltschutz-als-motivation-fuer

Paran, A. (2017). 'Only connect': researchers and teachers in dialogue. ELT J. 71 (4), 499–508. doi:10.1093/elt/ccx033

Penuel, W. R., Sun, M., Frank, K. A., and Gallagher, H. A. (2012). Using social network analysis to study how collegial interactions can augment teacher learning from external professional development. Am. J. Educ. 119 (1), 103–136. doi:10.1086/667756

Quesada-Pallarès, C., and Gegenfurtner, A. (2015). Toward a unified model of motivation for training transfer: A phase perspective. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft 18 (S1), 107–121. doi:10.1007/s11618-014-0604-4

Schober, B., Brandt, L., Kollmayer, M., and Spiel, C. (2016). Overcoming the ivory tower: Transfer and societal responsibility as crucial aspects of the Bildung-Psychology approach. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 13 (6), 636–651. doi:10.1080/17405629.2016.1231061

J.-R. Schreiber, and H. Siege (2015). Orientierungsrahmen für den Lernbereich Globale Entwicklung [rientation Framework for the Learning Area Global Development , p. 468.

J.-R. Schreiber, and H. Siege (2015). in Curriculum Framework: Education for Sustainable Development . Engagement Global gGmbH . 2nd edn.

Sotelino-Losada, A., Arbués-Radigales, E., García-Docampo, L., and González-Geraldo, J. L. (2021). Service-Learning in Europe. Dimensions and Understanding From Academic Publication. Front. Educ. 6. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.604825

Stoecker, R. (2016). Liberating service learning and the rest of higher education civic engagement . Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press .

Vasilescu, R., Barna, C., Epure, M., and Baicu, C. (2010). Developing university social responsibility: A model for the challenges of the new civil society. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2 (2), 4177–4182. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.660

Keywords: service-learning, design-based research, research methods, teacher education, engagement

Citation: Froehlich DE, Hobusch U and Moeslinger K (2021) Research Methods in Teacher Education: Meaningful Engagement Through Service-Learning. Front. Educ. 6:680404. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.680404

Received: 14 March 2021; Accepted: 05 May 2021; Published: 18 May 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Froehlich, Hobusch and Moeslinger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dominik E. Froehlich, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

A Practical Guide to Teaching Research Methods in Education

DOI link for A Practical Guide to Teaching Research Methods in Education

Get Citation

A Practical Guide to Teaching Research Methods in Education brings together more than 60 faculty experts. The contributors share detailed lesson plans about selected research concepts or skills in education and related disciplines, as well as discussions of the intellectual preparation needed to effectively teach the lesson.

Grounded in the wisdom of practice from exemplary and award-winning faculty from diverse institution types, career stages, and demographic backgrounds, this book draws on both the practical and cognitive elements of teaching educational (and related) research to students in higher education today. The book is divided into eight sections, covering the following key elements within education (and related) research: problems and research questions, literature reviews and theoretical frameworks, research design, quantitative methods, qualitative methods, mixed methods, findings and discussions, and special topics, such as student identity development, community and policy engaged research, and research dissemination. Within each section, individual chapters specifically focus on skills and perspectives needed to navigate the complexities of educational research. The concluding chapter reflects on how teachers of research also need to be learners of research, as faculty continuously strive for mastery, identity, and creativity in how they guide our next generation of knowledge producers through the research process.

Undergraduate and graduate professors of education (and related) research courses, dissertation chairs/committee members, faculty development staff members, and graduate students would all benefit from the lessons and expert commentary contained in this book.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter | 5 pages, introduction, part section i | 27 pages, topics, problems, and research questions, chapter 1 | 2 pages, introduction to section i, chapter 2 | 8 pages, from personal passion to hot topics, chapter 3 | 8 pages, articulating a research problem and its rationale, chapter 4 | 7 pages, part section ii | 27 pages, literature review and theoretical/conceptual framework, chapter 5 | 2 pages, introduction to section ii, chapter 6 | 7 pages, connecting pieces to the puzzle, chapter 7 | 6 pages, the candy sort, chapter 8 | 10 pages, theoretical and conceptual frameworks, part section iii | 38 pages, research design, chapter 9 | 3 pages, introduction to section iii, chapter 10 | 9 pages, visualize your research design, chapter 11 | 9 pages, let's road trip, chapter 12 | 8 pages, the self and research, chapter 13 | 7 pages, trustworthiness and ethics in research, part section iv | 39 pages, quantitative methods, chapter 14 | 3 pages, introduction to section iv, chapter 15 | 7 pages, making sense of multivariate analysis, chapter 16 | 7 pages, linear regression, chapter 17 | 11 pages, hands-on application of exploratory factor analysis in educational research, chapter 18 | 9 pages, trending topic, part section v | 47 pages, qualitative methods, chapter 19 | 3 pages, introduction to section v, chapter 20 | 8 pages, listening deeply, chapter 21 | 9 pages, write what you see, not what you know, chapter 22 | 8 pages, on the recovery of black life, chapter 23 | 8 pages, emerging approaches, chapter 24 | 9 pages, exploring how epistemologies guide the process of coding data and developing themes, part section vi | 31 pages, mixed methods, chapter 25 | 3 pages, introduction to section vi, chapter 26 | 8 pages, low hanging fruit, ripe for inquiry, chapter 27 | 8 pages, creating your masterpiece, chapter 28 | 10 pages, presenting and visualizing a mixed methods study, part section vii | 43 pages, findings and discussion, chapter 29 | 2 pages, introduction to section vii, chapter 30 | 9 pages, an introduction to regression using critical quantitative thinking, chapter 31 | 7 pages, show the story, chapter 32 | 8 pages, block by block, chapter 33 | 7 pages, making the theoretical practical, chapter 34 | 8 pages, the donut memo, part section viii | 48 pages, special topics, chapter 35 | 3 pages, introduction to section viii, chapter 36 | 7 pages, scholarly identity development of undergraduate researchers, chapter 37 | 8 pages, developing students' cultural competence through video interviews, chapter 38 | 8 pages, preparing students for community-engaged scholarship, chapter 39 | 7 pages, teaching policy implications, chapter 40 | 7 pages, introducing scholars to public writing, chapter | 6 pages, closing words.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

- Teaching Research Methods: How to Make It Meaningful to Students

view recording

How do you capture your students' attention in your Research Methods course? What works, and what doesn't? What are some of the challenges you face, and how do you overcome them?

SAGE authors Gregg Van Ryzin and Dahlia Remler share their vast experience and approach to teaching Research Methods to students with diverse interests and different degrees of prior training. In this new webinar, you will learn how they convey to students that research matters in their fields. They'll cover often-challenging topics, such as:

- Incorporating real-world examples of research into your teaching

- Encouraging students to distinguish causation from correlation

- Using intuitive path models to think about multivariate relationships

- Additional engaging approaches

ppt pRESENTATION

Research Methods in Practice

- Teaching Campaign Planning: Three Tips that Drive Action

- Teaching Public Policy: Tips on engaging your students and inspiring active participation

- Speaking Out: Voicing Movements in the Face of Censorship

- Improving Journalistic Writing: How students can use clearer thinking to tell better stories

- Evaluation Failures: Case Studies for Teaching and Learning

- A Practical Approach to doing Applied Conversation Analysis

- Teaching Data Science: Core Learning Outcomes and Topics for an Introductory Course

- Data Visualization: A Game of Decisions

- Three Ideas for Innovative Teaching of Psychology

- A Social Science Perspective on Data Science

- Text Mining for Social Scientists

- Teaching Ethics in Research Methods

- Teaching Research Methods in Criminology & Criminal Justice: Challenges & Tips

- Advancing Methodologies: A Conversation with John Creswell

- Presenting Data Effectively

- The Power of Stories: Engaging your American Government Students

- Why Do They Do It? Tips for Teaching Intro to Criminology

- 5 Ways to Take Your Entrepreneurship Teaching to the Next Level

- 5 Tips for Teaching Introduction to Mass Communication: Engaging Students Living in a Media World

- Teaching Statistics to People Who (Think They) Hate Statistics: Tips for Overcoming Statistics Anxiety

- The Challenges of Teaching Research Methods

- Finding Common Ground: Bringing Methods and Analysis into Context

- Successful Qualitative Research: Don't Get Too Comfortable!

- Why Use Mixed Methods?

- Top Ten Developments in Qualitative Evaluation Over the Last Decade

- Empowerment Evaluation

- Can We Really Know Anything in an Era of Fake News?

- Teaching Data Analytics in HRM Courses: Why It's Important and How to Do It

- 5 Ways to Modernize Your Introduction to Business Course

- Accessibility for Every Brain: Tips for Facilitating a Neurodiverse Classroom

- Bridging Leadership Skills to Organizational Culture Design

- Classroom Conversations on DEI in a Global Context: 5 Common Questions Students Ask about DEI And How to Engage Students in Productive Conversations

- Deconstructing Barbie

- Having Conversations About Race in the Classroom

- How to Design and Deliver an Authentic Course in Multicultural Education

- How to Improve Your Teaching Evaluations By Using the Socratic Method and Essay Exams

- Introduction to R with Dr. Maja Založnik

- R You Ready? Transitioning Your Intro Stats Course to R

- Sustainability Strategies in Supply Chains

- Teaching About Race, Ethnicity, and Crime

- The Top 10 Skills Needed by Today’s PR Students to Become Tomorrow’s PR Professionals

- Transforming Sociology Education

- Unpacking Issues of Second-Generation Gender Bias

- Webcast Recording Request: Demystifying Comparative Politics

- Webinar Recording Request: Decoding the Learning Code of Generation Z

- What Do Business Students Want in Today’s College Classroom? Perspectives from Both Small and Large Classroom Instructors

- What’s Congress Really Like?

How to Read and Interpret Research to Benefit Your Teaching Practice

Teachers can find helpful ideas in research articles and take a strategic approach to get the most out of what they’re reading.

Your content has been saved!

Have you read any education blogs, attended a conference session this summer, or gone to a back-to-school meeting so far where information on PowerPoint slides was supported with research like this: “Holland et al., 2023”? Perhaps, like me, you’ve wondered what to do with these citations or how to find and read the work cited. We want to improve our teaching practice and keep learning amid our busy schedules and responsibilities. When we find a sliver of time to look for the research article(s) being cited, how are we supposed to read, interpret, implement, and reflect on it in our practice?

There has been much research over the past decade building on research-practice partnerships . Teachers and researchers should work collaboratively to improve student learning. Though researchers in higher education typically conduct formal research and publish their work in journal articles, it’s important for teachers to also see themselves as researchers. They engage in qualitative analysis while circulating the room to examine and interpret student work and demonstrate quantitative analysis when making predictions around student achievement data.

There are different sources of knowledge and timely questions to consider that education researchers can learn and take from teachers. So, what if teachers were better equipped to translate research findings from a journal article into improved practice relevant to their classroom’s immediate needs? I’ll offer some suggestions on how to answer this question.

Removing Barriers to New Information

For starters, research is crucial for education. It helps us learn and create new knowledge. Teachers learning how to translate research into practice can help contribute toward continuous improvement in schools. However, not all research is beneficial or easily applicable. While personal interests may lead researchers in a different direction, your classroom experience holds valuable expertise. Researchers should be viewed as allies, not sole authorities.

Additionally, paywalls prevent teachers from accessing valuable research articles that are often referenced in professional development. However, some sites, like Sage and JSTOR , offer open access journals where you can find research relevant to your classroom needs. Google Scholar is another helpful resource where you can plug in keywords like elementary math , achievement , small-group instruction , or diverse learners to find articles freely available as PDFs. Alternatively, you can use Elicit and get answers to specific questions. It can provide a list of relevant articles and summaries of their findings.

Approach research articles differently than other types of writing, as they aren’t intended for our specific audience but rather for academic researchers. Keep this in mind when selecting articles that align with your teaching vision, student demographic, and school environment.

Using behavioral and brain science research, I implemented the spacing effect . I used this strategy to include spaced fluency, partner practices, and spiral reviews (e.g., “do nows”) with an intentional selection of questions and tasks based on student work samples and formative/summative assessment data. It improved my students’ memory, long-term retention, and proficiency, so I didn’t take it too personally when some of them forgot procedures or symbols.

What You’ll Find in a Research Article