Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

The Writing Process

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

In this section

Subsections.

- Enroll & Pay

- Jayhawk GPS

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

The Writing Process

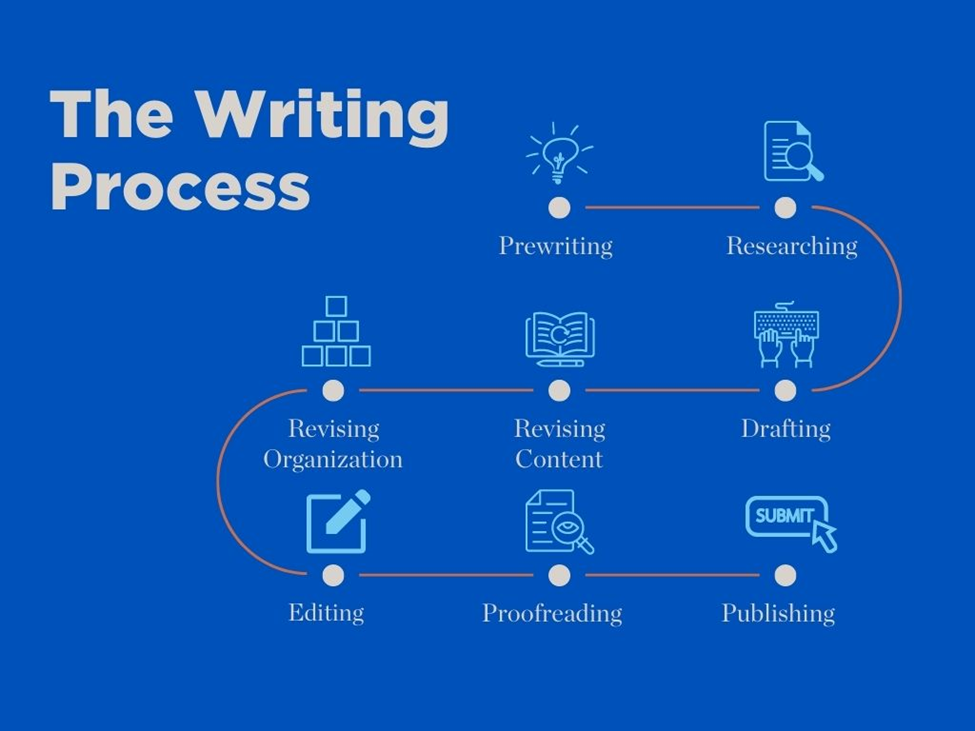

The writing process is something that no two people do the same way. There is no "right way" or "wrong way" to write. It can be a very messy and fluid process, and the following is only a representation of commonly used steps. Remember you can come to the Writing Center for assistance at any stage in this process.

Steps of the Writing Process

Step 1: Prewriting

Think and Decide

- Make sure you understand your assignment. See Research Papers or Essays

- Decide on a topic to write about. See Prewriting Strategies and Narrow your Topic

- Consider who will read your work. See Audience and Voice

- Brainstorm ideas about the subject and how those ideas can be organized. Make an outline. See Outlines

Step 2: Research (if needed)

- List places where you can find information.

- Do your research. See the many KU Libraries resources and helpful guides

- Evaluate your sources. See Evaluating Sources and Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Make an outline to help organize your research. See Outlines

Step 3: Drafting

- Write sentences and paragraphs even if they are not perfect.

- Create a thesis statement with your main idea. See Thesis Statements

- Put the information you researched into your essay accurately without plagiarizing. Remember to include both in-text citations and a bibliographic page. See Incorporating References and Paraphrase and Summary

- Read what you have written and judge if it says what you mean. Write some more.

- Read it again.

- Write some more.

- Write until you have said everything you want to say about the topic.

Step 4: Revising

Make it Better

- Read what you have written again. See Revising Content and Revising Organization

- Rearrange words, sentences, or paragraphs into a clear and logical order.

- Take out or add parts.

- Do more research if you think you should.

- Replace overused or unclear words.

- Read your writing aloud to be sure it flows smoothly. Add transitions.

Step 5: Editing and Proofreading

Make it Correct

- Be sure all sentences are complete. See Editing and Proofreading

- Correct spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

- Change words that are not used correctly or are unclear.

- APA Formatting

- Chicago Style Formatting

- MLA Formatting

- Have someone else check your work.

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 2003 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 42,322 quotes across 2003 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Is MasterClass right for me?

Take this quiz to find out.

A Complete Guide to the Writing Process: 6 Stages of Writing

Written by MasterClass

Last updated: Aug 23, 2021 • 10 min read

Every writer works in a different way. Some writers work straight through from beginning to end. Others work in pieces they arrange later, while others work from sentence to sentence. Understanding how and why you write the way you do allows you to treat your writing like the job it is, while allowing your creativity to run wild.

- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

The writing process.

- Academic writing

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Criticality in academic writing

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Dissertations

- Reflective writing

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Approaching the stages in effective academic writing: before, during and after.

Stages in assignment writing

Writing is a process, not the end product!

There's a lot more to a successful assignment than writing out the words. Reading, thinking, planning, and editing are also vital parts of the process.

These steps take you through the whole writing process: before, during and after:

1. Read the assignment instructions thoroughly. What exactly do you need to do?

2. Read, make notes, think critically , repeat. This is a crucial step!

3. Make a general plan with the main points.

4. Make a detailed plan, focusing on creating a clear structure.

5. Check the plan. Is the task addressed fully? Are you being critical?

6. Write the first draft. Read and think more as needed.

7. Edit and redraft as needed.

8. Proofread carefully. Focus on referencing, spelling and grammar.

9. Submit the assignment. Give yourself time before the deadline in case of problems.

10. Read feedback carefully to help improve your next assignments.

11. Start the process again for your next assignment!

This process is applicable to various writing projects, including essays, reports, and dissertations. Modifications can be made to suit specific requirements of those assignments.

View in a new window: The writing process [Google Doc]

Planning tips

Doing any project takes time, and academic writing projects are no exception. Planning takes time, and there's lots to consider before starting the planning process.

Here are ten tips on just that...

| • • • • • • • • • • • |

Have you read the assessment guidelines / criteria for the task?

These may be issued with the assessment and are usually found on the VLE or department web pages or printed in a hard copy from the department. If available, these will provide clearer instructions for approaching the assignment. Assessment criteria outline the knowledge, skills and understanding you will need to demonstrate to pass the assessment. Be sure that you understand what's being asked of you. Take a look at our tips on understanding assessment criteria .

| • • • • • • • • • • • |

What are the guidelines on the presentation of your work?

Is a font style and font size specified? Is line spacing and margin width specified? Does your assignment need to follow a particular structure? Is a cover sheet required?

If you want to set your document up properly, look at our guidance on using text processing software .

What kind of writing is specified in the task?

Is it an essay, report, case study, reflection...? The type or genre of writing will determine the style, organisation and conventions you should use. Take a look at examples of that type of work to gain an understanding of form.

Does your assessment specify a specific audience?

Is it for an academic or specialist audience; a professional or business audience; a lay audience? You will need to adapt your style and language to suit your target audience.

What are the expectations in terms of the inclusion of information?

What range of evidence, sources, data, etc., is required? Is there a specific context identified in the assignment title? Where will you source this information (e.g. lecture notes, seminar/tutorial notes, prior reading, information on the VLE)? What additional reading will you need to do?

Take a look at our guidance on choosing the right information sources .

Which referencing style is required?

Have you checked the referencing guidelines for your department? Have you completed the online integrity tutorial ? Do you intend to use reference management software ?

Have you checked the module learning outcomes and grade descriptors?

Module learning outcomes outline the knowledge, skills and understanding you will gain by completing the module. Grade descriptors identify what you must do to achieve a specific grade (1st, 2:1, 2:2 etc.). Taking note of these will help you determine the level you need to write at. Take a look at our tips on understanding module learning outcomes .

What is the word limit?

What is included in the word limit? What are the penalties if you are over or under word count? If there are separate tasks, is there a word count for each one?

What is the deadline for the assessment?

Is there a specified time by which you have to submit your assignment on the deadline date? What are the penalties if you go over this deadline? Do you know what the regulations are if you are unable to submit (e.g. because of exceptional circumstances)?

How will you submit?

Where do you need to submit to? If this is an office, what are the office hours? Are you required to submit more than one copy? If you're submitting electronically, do you know where to upload the work? Do you know how to upload it?

Ensure you allow enough time in case you have problems with printers or electronic submissions.

| • • • • • • • • • • • |

Before you start: understanding task requirements

Meeting task requirements.

To get a good mark, you must complete the set assignment! This means answering all parts of the task, staying relevant throughout and using an appropriate structure and style.

For example, if the task is to write an essay critiquing the cultural influence of Star Wars, but instead, you write a reflective piece on your own opinion of Star Trek, you won't get a very good grade as you've not completed the set assignment.

To make sure your work meets the task requirements:

- Read the assessment brief carefully! If you have any questions, ask your tutor to clarify.

- Break down the title/question - see the advice below.

- Plan your points before you start writing. Have you covered everything? Are all the points relevant?

- Use the style and structure expected for that type of writing.

- Identify where you need to be descriptive and where you need to be critical:

Breaking down your title

You've been given an assignment title, but what is it actually asking? This activity takes you through the stages of analysing a question, breaking down an assignment title to clearly identify the task.

Choose an assignment title:

Analysing the question - Arts & Humanities

Below is an example question from the Faculty of Arts and Humanities to show you how to analyse a question to ensure that all elements of the task are addressed:

Describe how the presentation of gender in children's literature from the 1950s to the present has changed and critically evaluate how the development of feminist criticism has contributed to this change. Illustrate your answer with examples from the module material and wider reading .

In the above text, select the words or phrases that identify the two broad topics

That's not the right answer

You still need to identify the topics.

Have another go or reveal the answer .

Yes, that's the right answer!

The broad topics of this question are gender in children's literature in literature, and feminist criticism .

| • • • • • |

In the essay question, click on the specific context you will need to look at.

The specific context you need to look at is children's literature , specifically, children's literature from the 1950s to the present .

| • • • • • |

Now click on the instructional words or phrases that indicate the tasks which need to be completed - there are three to identify.

You still need to identify some of the instructions. Have another go or reveal the answers .

You're being instructed to describe , critically evaluate , and illustrate .

Describe how the presentation of gender in children's literature from the 1950s to the present has changed and critically evaluate how the development of feminist criticism has contributed to this change . Illustrate your answer with examples from the module material and wider reading .

Click on the part of the question which will get you the most marks and therefore should get the most attention .

The part of the question that will get you the most marks and therefore should get the most attention is critically evaluate how feminist criticism has contributed to this change .

You got correct.

Hopefully you got some ideas from those exercises about how to analyse and break down your questions. Now take a look at some of the other advice on these pages.

| • • • • • |

Analysing the question - Sciences

Below is an example question from the Faculty of Sciences to show you how to analyse a question to ensure that all elements of the task are addressed:

To what extent have approaches to environmental management contributed to our current position on energy production and use ? Evaluate the ways in which these approaches may help to shape our energy strategy for the future .

In the essay question, click on the words or phrases that identify the broad topic you will need to discuss in your answer

The broad topic of this question is environmental management .

In the essay question, click on the two words which specify the contexts you will need to look at.

You still need to identify the contexts.

The words that specify the specific contexts you will need to look at are current and future .

Now click on the phrases or instructional words that indicate the tasks which need to be completed - there are two to identify.

You're being instructed to consider to what extent and to evaluate .

Click on the part of the question which will get you the most marks and therefore should get the most attention

The part of the question that will get you the most marks and therefore should get the most attention is evaluate the ways in which these approaches may help to shape our energy strategy for the future .

Analysing the question - Social Sciences

Below is an example question from the Faculty of Social Sciences to show you how to analyse a question to ensure that all elements of the task are addressed:

Outline the ways in which young people criminally offend in society and how restorative justice seeks to modify such behaviour . Critically evaluate the effectiveness of restorative justice in terms of rehabilitating young offenders and also protecting the public .

In the essay question, click on the words or phrases that identify the broad topics you will need to discuss in your answer

The broad topics of this question are people criminally offend and restorative justice .

In the essay question, click on the phrase which specifies the context you will need to look at.

The specific context you need to look at is young people .

Now select the phrases or instructional words that indicate the tasks which need to be completed - there are two to identify

You're being instructed to outline and critically evaluate .

The part of the question that will get you the most marks and therefore should get the most attention is critically evaluate the effectiveness of restorative justice in terms of rehabilitating young offenders and also protecting the public .

Planning assignment structure

Once you've understood the task requirements, done some reading and come up with some ideas for what to include, you can start mapping out your assignment structure.

A good plan is key for a well-structured assignment - don't just launch into writing with no idea of where you're going!

This planning stage can also be a useful opportunity to think more deeply about the assignment and consider how the different ideas fit together, so it can help you develop your argument.

It's ok to make changes to your plan later - you might come up with more ideas, or another line of argumentation while writing. Make sure that you check the structure is still logical though!

Find out more about planning the general structure of an assignment:

Proofreading & checking

Everyone makes small mistakes and typos when they write; things like spelling mistakes, grammar or punctuation errors, incorrect referencing format or using the wrong word.

When you've spent a long time working on an assignment, you may not notice these small errors, so make sure to proofread (or check ) your work carefully before you submit it. You don't want these mistakes to make it into your final assignment, as they can make it harder for the reader to understand your points and could affect your grade.

Our top proofreading tips:

- use a spellchecker - but remember this won't pick up everything!

- put your assignment away for a little while, then come back later and read through it carefully. Focus on spelling, grammar and punctuation.

- it can be easier to notice mistakes if you read your assignment out loud or use a tool like Read&Write to read it to you.

- check that each of your citations and references is correctly formatted

Here are some specific things you can look out for in proofreading:

close all accordion sections

Language & formatting checks

Spelling and grammar.

- Check for spelling errors using a spellchecker and reading through the work.

- Check for double spaces and repeated words.

- Check for homophones - words that sound the same but look different (eg, to/too/two, right/write)

- Check that verbs and nouns match (eg, These results suggest.., NOT These results suggests...)

- Have any personal or informal words/phrases been used?

Punctuation

- General guide to correct punctuation use [Web]

- Full stops (.) and commas (,) come immediately after the word and need a space after them.

- Brackets () go inside a sentence (ie, before the full stop).

- Have you followed your department's formatting guidelines?

- Is the same font and text size used for all body text?

- Have you double spaced the writing? Is this required?

- Have you used the correct method of linking to appendices?

Referencing style checks

It's very important that your citations and references are correct - this is something that markers will definitely be looking for!

Before you submit, check your referencing is correct:

- Are author names correct? Especially pay attention to which name is the surname.

- Have all authors been included? Check your referencing style's format for dealing with multiple authors.

- Do references include all of the required information?

- Is the correct punctuation and text formatting used, especially full stops, commas, ampersand (&) and italics ?

- Are in-text citations inside the sentence (ie., before the full stop)?

- Are all sources cited in the text included in the reference list (or vice versa)?

- Do you have to include a reference list (which includes only sources directly cited in the text), or a bibliography (which includes all sources used to produce the writing and not all have to be cited in the text).

More detailed advice:

Submitting assignments on Yorkshare VLE

Most assignments will be submitted through the Yorkshare VLE (Blackboard). You'll receive information on how to do this from your department.

For advice on using the submission points, see our dedicated guide:

Use feedback to improve your next assignments

Feedback on your work can show what you're doing well and identify areas that you need to work on. For example, if you receive feedback that your work isn't clearly organised, you could focus on planning carefully and using a logical structure in your next assignments.

Find out how to use your feedback to improve and advice in dealing with common issues in our assessment and feedback guide:

- << Previous: General writing skills

- Next: Academic writing style >>

- Last Updated: Sep 16, 2024 3:31 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/academic-writing

- Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Writers: The Writing Process

Writing is a process that involves at least four distinct steps: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. It is known as a recursive process. While you are revising, you might have to return to the prewriting step to develop and expand your ideas.

- Prewriting is anything you do before you write a draft of your document. It includes thinking, taking notes, talking to others, brainstorming, outlining, and gathering information (e.g., interviewing people, researching in the library, assessing data).

- Although prewriting is the first activity you engage in, generating ideas is an activity that occurs throughout the writing process.

- Drafting occurs when you put your ideas into sentences and paragraphs. Here you concentrate upon explaining and supporting your ideas fully. Here you also begin to connect your ideas. Regardless of how much thinking and planning you do, the process of putting your ideas in words changes them; often the very words you select evoke additional ideas or implications.

- Don’t pay attention to such things as spelling at this stage.

- This draft tends to be writer-centered: it is you telling yourself what you know and think about the topic.

- Revision is the key to effective documents. Here you think more deeply about your readers’ needs and expectations. The document becomes reader-centered. How much support will each idea need to convince your readers? Which terms should be defined for these particular readers? Is your organization effective? Do readers need to know X before they can understand Y?

- At this stage you also refine your prose, making each sentence as concise and accurate as possible. Make connections between ideas explicit and clear.

- Check for such things as grammar, mechanics, and spelling. The last thing you should do before printing your document is to spell check it.

- Don’t edit your writing until the other steps in the writing process are complete.

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

Encyclopedia for Writers

Writing with ai, the ultimate blueprint: a research-driven deep dive into the 13 steps of the writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - Founder, Writing Commons

This article provides a comprehensive, research-based introduction to the major steps , or strategies , that writers work through as they endeavor to communicate with audiences . Since the 1960s, the writing process has been defined to be a series of steps , stages, or strategies. Most simply, the writing process is conceptualized as four major steps: prewriting , drafting , revising , editing . That model works really well for many occasions. Yet sometimes you'll face really challenging writing tasks that will force you to engage in additional steps, including, prewriting , inventing , drafting , collaborating , researching , planning , organizing , designing , rereading , revising , editing , proofreading , sharing or publishing . Expand your composing repertoire -- your ability to respond with authority , clarity , and persuasiveness -- by learning about the dispositions and strategies of successful, professional writers.

Table of Contents

Like water cascading to the sea, flow feels inevitable, natural, purposeful. Yet achieving flow is a state of mind that can be difficult to achieve. It requires full commitment to the believing gam e (as opposed to the doubting game ).

What are the Steps of the Writing Process?

Since the 1960s, it has been popular to describe the writing process as a series of steps or stages . For simple projects, the writing process is typically defined as four major steps:

- drafting

This simplified approach to writing is quite appropriate for many exigencies–many calls to write . Often, e.g., we might read an email quickly, write a response, and then send it: write, revise, send.

However, in the real world, for more demanding projects — especially in high-stakes workplace writing or academic writing at the high school and college level — the writing process involve additional steps, or strategies , such as

- collaboration

- researching

- proofreading

- sharing or publishing.

Related Concepts: Mindset ; Self Regulation

Summary – Writing Process Steps

The summary below outlines the major steps writers work through as they endeavor to develop an idea for an audience .

1. Prewriting

Prewriting refers to all the work a writer does on a writing project before they actually begin writing .

Acts of prewriting include

- Prior to writing a first draft, analyze the context for the work. For instance, in school settings students may analyze how much of their grade will be determined by a particular assignment. They may question how many and what sources are required and what the grading criteria will be used for critiquing the work.

- To further their understanding of the assignment, writers will question who the audience is for their work, what their purpose is for writing, what style of writing their audience expects them to employ, and what rhetorical stance is appropriate for them to develop given the rhetorical situation they are addressing. (See the document planner heuristic for more on this)

- consider employing rhetorical appeals ( ethos , pathos , and logos ), rhetorical devices , and rhetorical modes they want to develop once they begin writing

- reflect on the voice , tone , and persona they want to develop

- Following rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning , writers decide on the persona ; point of view ; tone , voice and style of writing they hope to develop, such as an academic writing prose style or a professional writing prose style

- making a plan, an outline, for what to do next.

2. Invention

Invention is traditionally defined as an initial stage of the writing process when writers are more focused on discovery and creative play. During the early stages of a project, writers brainstorm; they explore various topics and perspectives before committing to a specific direction for their discourse .

In practice, invention can be an ongoing concern throughout the writing process. People who are focused on solving problems and developing original ideas, arguments , artifacts, products, services, applications, and texts are open to acts of invention at any time during the writing process.

Writers have many different ways to engage in acts of invention, including

- What is the exigency, the call to write ?

- What are the ongoing scholarly debates in the peer-review literature?

- What is the problem ?

- What do they read? watch? say? What do they know about the topic? Why do they believe what they do? What are their beliefs, values, and expectations ?

- What rhetorical appeals — ethos (credibility) , pathos (emotion) , and logos (logic) — should I explore to develop the best response to this exigency , this call to write?

- What does peer-reviewed research say about the subject?

- What are the current debates about the subject?

- Embrace multiple viewpoints and consider various approaches to encourage the generation of original ideas.

- How can I experiment with different media , genres , writing styles , personas , voices , tone

- Experiment with new research methods

- Write whatever ideas occur to you. Focus on generating ideas as opposed to writing grammatically correct sentences. Get your thoughts down as fully and quickly as you can without critiquing them.

- Use heuristics to inspire discovery and creative thinking: Burke’s Pentad ; Document Planner , Journalistic Questions , The Business Model Canvas

- Embrace the uncertainty that comes with creative exploration.

- Listen to your intuition — your felt sense — when composing

- Experiment with different writing styles , genres , writing tools, and rhetorical stances

- Play the believing game early in the writing process

3. Researching

Research refers to systematic investigations that investigators carry out to discover new knowledge , test knowledge claims , solve problems , or develop new texts , products, apps, and services.

During the research stage of the writing process, writers may engage in

- Engage in customer discovery interviews and survey research in order to better understand the problem space . Use surveys , interviews, focus groups, etc., to understand the stakeholder’s s (e.g., clients, suppliers, partners) problems and needs

- What can you recall from your memory about the subject?

- What can you learn from informal observation?

- What can you learn from strategic searching of the archive on the topic that interests you?

- Who are the thought leaders?

- What were the major turns to the conversation ?

- What are the current debates on the topic ?

- Mixed research methods , qualitative research methods , quantitative research methods , usability and user experience research ?

- What citation style is required by the audience and discourse community you’re addressing? APA | MLA .

4. Collaboration

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others to exchange ideas, solve problems, investigate subjects , coauthor texts , and develop products and services.

Collaboration can play a major role in the writing process, especially when authors coauthor documents with peers and teams , or critique the works of others .

Acts of collaboration include

- Paying close attention to what others are saying, acknowledging their input, and asking clarifying questions to ensure understanding.

- Expressing ideas, thoughts, and opinions in a concise and understandable manner, both verbally and in writing.

- Being receptive to new ideas and perspectives, and considering alternative approaches to problem-solving.

- Adapting to changes in project goals, timelines, or team dynamics, and being willing to modify plans when needed.

- Distributing tasks and responsibilities fairly among team members, and holding oneself accountable for assigned work.

- valuing and appreciating the unique backgrounds, skills, and perspectives of all team members, and leveraging this diversity to enhance collaboration.

- Addressing disagreements or conflicts constructively and diplomatically, working towards mutually beneficial solutions.

- Providing constructive feedback to help others improve their work, and being open to receiving feedback to refine one’s own ideas and contributions.

- Understanding and responding to the emotions, needs, and concerns of team members, and fostering a supportive and inclusive environment .

- Acknowledging and appreciating the achievements of the team and individual members, and using successes as a foundation for continued collaboration and growth.

5. Planning

Planning refers to

- the process of planning how to organize a document

- the process of managing your writing processes

6. Organizing

Following rhetorical analysis , following prewriting , writers question how they should organize their texts. For instance, should they adopt the organizational strategies of academic discourse or workplace-writing discourse ?

Writing-Process Plans

- What is your Purpose? – Aims of Discourse

- What steps, or strategies, need to be completed next?

- set a schedule to complete goals

Planning Exercises

- Document Planner

- Team Charter

7. Designing

Designing refers to efforts on the part of the writer

- to leverage the power of visual language to convey meaning

- to create a visually appealing text

During the designing stage of the writing process, writers explore how they can use the elements of design and visual language to signify , clarify , and simplify the message.

Examples of the designing step of the writing process:

- Establishing a clear hierarchy of visual elements, such as headings, subheadings, and bullet points, to guide the reader’s attention and facilitate understanding.

- Selecting appropriate fonts, sizes, and styles to ensure readability and convey the intended tone and emphasis.

- Organizing text and visual elements on the page or screen in a manner that is visually appealing, easy to navigate, and supports the intended message.

- Using color schemes and contrasts effectively to create a visually engaging experience, while also ensuring readability and accessibility for all readers.

- Incorporating images, illustrations, charts, graphs, and videos to support and enrich the written content, and to convey complex ideas in a more accessible format.

- Designing content that is easily accessible to a wide range of readers, including those with visual impairments, by adhering to accessibility guidelines and best practices.

- Maintaining a consistent style and design throughout the text, which includes the use of visuals, formatting, and typography, to create a cohesive and professional appearance.

- Integrating interactive elements, such as hyperlinks, buttons, and multimedia, to encourage reader engagement and foster deeper understanding of the content.

8. Drafting

Drafting refers to the act of writing a preliminary version of a document — a sloppy first draft. Writers engage in exploratory writing early in the writing process. During drafting, writers focus on freewriting: they write in short bursts of writing without stopping and without concern for grammatical correctness or stylistic matters.

When composing, writers move back and forth between drafting new material, revising drafts, and other steps in the writing process.

9. Rereading

Rereading refers to the process of carefully reviewing a written text. When writers reread texts, they look in between each word, phrase, sentence, paragraph. They look for gaps in content, reasoning, organization, design, diction, style–and more.

When engaged in the physical act of writing — during moments of composing — writers will often pause from drafting to reread what they wrote or to reread some other text they are referencing.

10. Revising

Revision — the process of revisiting, rethinking, and refining written work to improve its content , clarity and overall effectiveness — is such an important part of the writing process that experienced writers often say “writing is revision” or “all writing is revision.”

For many writers, revision processes are deeply intertwined with writing, invention, and reasoning strategies:

- “Writing and rewriting are a constant search for what one is saying.” — John Updike

- “How do I know what I think until I see what I say.” — E.M. Forster

Acts of revision include

- Pivoting: trashing earlier work and moving in a new direction

- Identifying Rhetorical Problems

- Identifying Structural Problems

- Identifying Language Problems

- Identifying Critical & Analytical Thinking Problems

11. Editing

Editing refers to the act of critically reviewing a text with the goal of identifying and rectifying sentence and word-level problems.

When editing , writers tend to focus on local concerns as opposed to global concerns . For instance, they may look for

- problems weaving sources into your argument or analysis

- problems establishing the authority of sources

- problems using the required citation style

- mechanical errors ( capitalization , punctuation , spelling )

- sentence errors , sentence structure errors

- problems with diction , brevity , clarity , flow , inclusivity , register, and simplicity

12. Proofreading

Proofreading refers to last time you’ll look at a document before sharing or publishing the work with its intended audience(s). At this point in the writing process, it’s too late to add in some new evidence you’ve found to support your position. Now you don’t want to add any new content. Instead, your goal during proofreading is to do a final check on word-level errors, problems with diction , punctuation , or syntax.

13. Sharing or Publishing

Sharing refers to the last step in the writing process: the moment when the writer delivers the message — the text — to the target audience .

Writers may think it makes sense to wait to share their work later in the process, after the project is fairly complete. However, that’s not always the case. Sometimes you can save yourself a lot of trouble by bringing in collaborators and critics earlier in the writing process.

Doherty, M. (2016, September 4). 10 things you need to know about banyan trees. Under the Banyan. https://underthebanyan.blog/2016/09/04/10-things-you-need-to-know-about-banyan-trees/

Emig, J. (1967). On teaching composition: Some hypotheses as definitions. Research in The Teaching of English, 1(2), 127-135. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED022783.pdf

Emig, J. (1971). The composing processes of twelfth graders (Research Report No. 13). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Emig, J. (1983). The web of meaning: Essays on writing, teaching, learning and thinking. Upper Montclair, NJ: Boynton/Cook Publishers, Inc.

Ghiselin, B. (Ed.). (1985). The Creative Process: Reflections on the Invention in the Arts and Sciences . University of California Press.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. (1980). Identifying the Organization of Writing Processes. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive Processes in Writing: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R. (2012). Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication, 29(3), 369-388. https://doi: 10.1177/0741088312451260

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1106-1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1106

Leijten, Van Waes, L., Schriver, K., & Hayes, J. R. (2014). Writing in the workplace: Constructing documents using multiple digital sources. Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 285–337. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.05.03.3

Lundstrom, K., Babcock, R. D., & McAlister, K. (2023). Collaboration in writing: Examining the role of experience in successful team writing projects. Journal of Writing Research, 15(1), 89-115. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2023.15.01.05

National Research Council. (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.https://doi.org/10.17226/13398.

North, S. M. (1987). The making of knowledge in composition: Portrait of an emerging field. Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Murray, Donald M. (1980). Writing as process: How writing finds its own meaning. In Timothy R. Donovan & Ben McClelland (Eds.), Eight approaches to teaching composition (pp. 3–20). National Council of Teachers of English.

Murray, Donald M. (1972). “Teach Writing as a Process Not Product.” The Leaflet, 11-14

Perry, S. K. (1996). When time stops: How creative writers experience entry into the flow state (Order No. 9805789). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304288035). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/when-time-stops-how-creative-writers-experience/docview/304288035/se-2

Rohman, D.G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1964). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Rohman, D. G., & Wlecke, A. O. (1975). Pre-writing: The construction and application of models for concept formation in writing (Cooperative Research Project No. 2174). U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Sommers, N. (1980). Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers. College Composition and Communication, 31(4), 378-388. doi: 10.2307/356600

The Elements of Style

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Recommended

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority & Credibility – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - How to Differentiate Quality Information from Misinformation & Rhetrickery

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. You need to be strategic about how you consume and use information in order to thrive,...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Do You Know The 7 Steps Of The Writing Process?

How much do you know about the different stages of the writing process? Even if you’ve been writing for years, your understanding of the processes of writing may be limited to writing, editing, and publishing.

It’s not your fault. Much of the writing instruction in school and online focus most heavily on those three critical steps.

Important as they are, though, there’s more to creating a successful book than those three. And as a writer, you need to know.

The 7 Steps of the Writing Process

Read on to familiarize yourself with the seven writing process steps most writers go through — at least to some extent. The more you know each step and its importance, the more you can do it justice before moving on to the next.

1. Planning or Prewriting

This is probably the most fun part of the writing process. Here’s where an idea leads to a brainstorm, which leads to an outline (or something like it).

Whether you’re a plotter, a pantser, or something in between, every writer has some idea of what they want to accomplish with their writing. This is the goal you want the final draft to meet.

With both fiction and nonfiction , every author needs to identify two things for each writing project:

- Intended audience = “For whom am I writing this?”

- Chosen purpose = “What do I want this piece of writing to accomplish?”

In other words, you start with the endpoint in mind. You look at your writing project the way your audience would. And you keep its purpose foremost at every step.

From planning, we move to the next fun stage.

2. Drafting (or Writing the First Draft)

There’s a reason we don’t just call this the “rough draft,” anymore. Every first draft is rough. And you’ll probably have more than one rough draft before you’re ready to publish.

For your first draft, you’ll be freewriting your way from beginning to end, drawing from your outline, or a list of main plot points, depending on your particular process.

To get to the finish line for this first draft, it helps to set word count goals for each day or each week and to set a deadline based on those word counts and an approximate idea of how long this writing project should be.

Seeing that deadline on your calendar can help keep you motivated to meet your daily and weekly targets. It also helps to reserve a specific time of day for writing.

Another useful tool is a Pomodoro timer, which you can set for 20-25 minute bursts with short breaks between them — until you reach your word count for the day.

3. Sharing Your First Draft

Once you’ve finished your first draft, it’s time to take a break from it. The next time you sit down to read through it, you’ll be more objective than you would be right after typing “The End” or logging the final word count.

It’s also time to let others see your baby, so they can provide feedback on what they like and what isn’t working for them.

You can find willing readers in a variety of places:

- Social media groups for writers

- Social media groups for readers of a particular genre

- Your email list (if you have one)

- Local and online writing groups and forums

This is where you’ll get a sense of whether your first draft is fulfilling its original purpose and whether it’s likely to appeal to its intended audience.

You’ll also get some feedback on whether you use certain words too often, as well as whether your writing is clear and enjoyable to read.

4. Evaluating Your Draft

Here’s where you do a full evaluation of your first draft, taking into account the feedback you’ve received, as well as what you’re noticing as you read through it. You’ll mark any mistakes with grammar or mechanics.