Your browser is ancient! Upgrade to a different browser or install Google Chrome Frame to experience this site.

Master of Advanced Studies in INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

Case Studies in Intercultural Communication

Welcome to the MIC Case Studies page.

Here you will find more than fifty different case studies, developed by our former participants from the Master of Advanced Studies in Intercultural Communication. The richness of this material is that it contains real-life experiences in intercultural communication problems in various settings, such as war, family, negotiations, inter-religious conflicts, business, workplace, and others.

Cases also include renowned organizations and global institutions, such as the United Nations, Multinationals companies, Non-Governmental Organisations, Worldwide Events, European, African, Asian and North and South America Governments and others.

Intercultural situations are characterized by encounters, mutual respect and the valorization of diversity by individuals or groups of individuals identifying with different cultures. By making the most of the cultural differences, we can improve intercultural communication in civil society, in public institutions and the business world.

How can these Case Studies help you?

These case studies were made during the classes at the Master of Advanced Studies in Intercultural Communication. Therefore, they used the most updated skills, tools, theories and best practices available. They were created by participants working in the field of public administration; international organizations; non-governmental organizations; development and cooperation organizations; the business world (production, trade, tourism, etc.); the media; educational institutions; and religious institutions. Through these case studies, you will be able to learn through real-life stories, how practitioners apply intercultural communication skills in multicultural situations.

Why are we opening our "Treasure Chest" for you?

We believe that Intercultural Communication has a growing role in the lives of organizations, companies and governments relationship with the public, between and within organizations. There are many advanced tools available to access, analyze and practice intercultural communication at a professional level. Moreover, professionals are demanded to have an advanced cross-cultural background or experience to deal efficiently with their environment. International organizations are requiring workers who are competent, flexible, and able to adjust and apply their skills with the tact and sensitivity that will enhance business success internationally. Intercultural communication means the sharing of information across diverse cultures and social groups, comprising individuals with distinct religious, social, ethnic, and educational backgrounds. It attempts to understand the differences in how people from a diversity of cultures act, communicate and perceive the world around them. For this reason, we are sharing our knowledge chest with you, to improve and enlarge intercultural communication practice, awareness, and education.

We promise you that our case studies, which are now also yours, will delight, entertain, teach, and amaze you. It will reinforce or change the way you see intercultural communication practice, and how it can be part of your life today. Take your time to read them; you don't need to read all at once, they are rather small and very easy to read. The cases will always be here waiting for you. Therefore, we wish you an insightful and pleasant reading.

These cases represent the raw material developed by the students as part of their certification project. MIC master students are coming from all over the world and often had to write the case in a non-native language. No material can be reproduced without permission. © Master of Advanced Studies in Intercultural Communication , Università della Svizzera italiana, Switzerland.

| : Catholic, Convert, Ethnocentrism, Family, Judaism, Marriage, Mediation, Mexico, Religion, Stereotypes, Stigmatisation, Values | |

| : Cultural Dimensions, Cultural Values, Culture Shock, Erasmus, Finland, France, Integration, Proximity, Studying Abroad, Time Orientation | |

| : Cultural Dimensions, Cultural Values, Finland, International Collaboration, Italy, Miscommunication, Task Vs Social Orientation, Time Orientation | |

| : Economics, Intercultural Negotiations, Iran, Media, Politics, Public Relations, Switzerland | |

| : Africa, Critical Incident, Gender, Generation, High Context/Low Context, Individualism/Collectivism, Nigeria, Public Position, Religion, Time Orientation | |

| : Business, China, Directness, East-West, Individualism/Collectivism, Intercultural Collaboration, Miscommunication, Temporality | |

| : Cultural Prejudice, Generalisation, National Identity, National Past, Offence, Stereotypes, Swiss Banks, Switzerland, WWII | |

| : Christianity, Christmas, Education, Foreign Influence, Islam, Mediation, Parents, Religious Freedom, Schools, Switzerland, Tolerance | |

| : Airport, Awkward Feeling, Burka, Clothing, Critical Incident, International Setting, Local Customs, Neutral Setting, Stereotypes, Travel | |

| : Collaboration, Company, Employees, Face Loss, Gender, Intercultural Collaboration, Mediation, Turkey | |

| : Africa, Competence, In-Country Diversity, Nigeria, Religious Conflicts, Representations, Social Capital, Stereotypes | |

| : Collaboration, Culture Shock, Ethnocentrism, Integration, International Organizations, Management Styles, Mexico, Working Relationship, Working Styles | |

| : China, Cultural Adaptation, Culture Shock, Developmental Model, Going Abroad, Living Conditions, Stages Of Culture Shock, Studying Abroad, Unhappiness | |

| : Bureaucracy, Collaboration, Critical Incident, Cultural Etiquette, Netherlands, Rules And Procedure, Saudi Arabia, Status And Hierarchy, Western Vs Oriental | |

| : (Reverse) Culture Shock, Attire, Clothing, Cultural Configuration, Dress Code, Formality, Job Interviews, Non-Verbal Communication, Work Setting, Working Culture | |

| : Bosnia-Herzegovina, Collaboration, Cultural Perception, Employees, Hierarchy, Individualism/Collectivism, Power Distance, Time Perception | |

| : Arbitration, Cultural Presupposition, Discrimination, Ethnocentrism, Mediation, Rumania, Torture, Trauma, Xenophobia | |

| : Ramadan, Religion, Workplace, Conflict, Mediation Strategies, Inter-Religious Dialogue, Professional Environment | |

| : Christianity, Church, Equality, Finland, Gender, Gender Equality, Media, Religion, Religious Beliefs | |

| : Afghanistan, Critical Incident, Cultural Assumptions, Gender Relations, Hierarchy, Islam, Religion, Work Abroad | |

| : Agnostic, Atheist, Baptism, Christianity, Cultural Norm, Education, Mediation, Parents, Personal Choice, Switzerland, Upbringing | |

| : Geert Wilders, Immigration, Immigration Policy, Islam, Netherlands, Politics, Religion, Religious Stereotypes, Terrorism | |

| : Britain, Culture Of Origin, Expat, Going Abroad, Language, Multiple Identities, Stranger, Switzerland, Two Cultures, Values | |

| : Culture Of Origin, Identity, Identity Shock, Immigration, Language, Stranger, Switzerland | |

| : Collaboration, Cultural Dimensions, Egypt, Employees, Intercultural Competence, Management Styles, Working Abroad | |

| : Adaptation, Culture Shock, Exchange Year, Expectations, Host Family High School, Stereotypes, Study, Teenager, USA, Way Of Life | |

| : African Immigrant, Culture Shock, Immigration, Monoculturality Vs Multiculturality, Multicultural Environment, Multiple Identities, Saudi Arabia, Studying Abroad | |

| : Business Culture, Collaboration, Communication, Compensation, Complaint, Individualism/Collectivism, Local Market Knowledge, Translation, Turkey | |

| : Discrimination, Islamophobia, Mediation, Minarets, Religion, Right-Wing Politics, Stereotypes, Switzerland | |

| : Africa, Ethnic Communities, Genocide, Intercultural Competence, Mediation, Peace Building, Rwanda, Stakeholders | |

| : Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cultural Values, Ex-Yugoslavia, Mediation, Peace Building, Perception, Religion, Religious Belief | |

| : Choice Of Register, Common Ground, Development Cooperation, Ecuador, Indigenous People, Intercultural Negotiations, Negotiation, Non-Verbal Communication, United Nations | |

| : Collaboration, Cultural Dimensions, Intercultural Awareness, Intercultural Competence, Portugal, Stereotypes, United Kingdom, Working Styles | |

| : Communication, Cultural Dimensions, Germany, Immigration, Language, Linguistic Register, Politeness, Switzerland | |

| : Forum, Gender, Homosexuality, International Setting, Islam, Mediation, Politics, Polygamy, Values, Western Vs Oriental, Youth | |

| : Collaboration, Language, Mediation, Neat, Röstigraben, Stereotype, Switzerland, Tunnel | |

| : Archeology, Cultural History, Isreal, Mediation, Middle-East Conflict, Palestine, Religion, Religious Symbols | |

| : Acculturation, China, Cultural Pressure, Family Expectations, Generation, Italy, Marriage, Overseas-Chinese, Parents, Traditions, Two Cultures | |

| : Awkward Feeling, Critical Incident, Cultural Values, Discrimination, Gender, Immigration, Individualism/Collectivism, Intercultural Competence, Money, Politeness, Social Reflex, Stereotypes | |

| : Apartheid, Colonialism, Cultural History, Intra-National Diversity, Minorities, Names, South Africa, Symbols | |

| : Islam, Mediation, Offence, Religion, Religious Belief, Stereotypes, Vatican, Violence, Western Vs Oriental | |

| : Assumptions, Business Meeting, Critical Incident, Etiquette, Gender Relations, Islam, Pakistan, Public Event | |

| : Inter-Religious Dialogue, Islam, Media, Mediation, Minarets, Muslim Communities, Norms, Public Opinion, Religion, Switzerland, Symbol, Values, Vote | |

| : Collaboration, Critical Incident, Eating Habits, Hierarchy, India, Mediation, Non-Verbal Communication, Outsourcing | |

| : Islam, Mediation, Minarets, Religion, Religious Symbols, Religious Values And Identity, Switzerland, Symbol, Vote | |

| : Critical Incident, Dancing, Intercultural Relationship, Meeting The Parents, National Symbol, Non-Verbal Communication, Stereotypes, Turkey, Western Vs Oriental | |

| : Asylum, Conflict Resolution, Denmark, Education, Immigration, Islam, Mediation, Parents, Religion, Stereotypes, Veil | |

| : Collaboration, Critical Incident, Going Abroad, International Setting, Linguistic Meaning, Management, Miscommunication, Philippines, Stress, Time Orientation, Working Style | |

| : Australia, Being Different, Discrimination, Generalisation, Hostility, Immigration, South-East Asian Immigrants, Stereotypes, Two Cultures |

Subscribe Us

If you want to receive our last updated case studies or news about the program, leave us your email, and you will know in first-hand about intercultural communication education and cutting-edge research in the intercultural field.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1. WHAT IS TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION?

1.4 Case Study: The Cost of Poor Communication

No one knows exactly how much poor communication costs business, industry and government each year, but estimates suggest billions. In fact, a recent estimate claims that the cost in the U.S. alone are close to $4 billion annually! [1] Poorly-worded or inefficient emails, careless reading or listening to instructions, documents that go unread due to poor design, hastily presenting inaccurate information, sloppy proofreading — all of these examples result in inevitable costs. The problem is that these costs aren’t usually included on the corporate balance sheet at the end of each year; if they are not properly or clearly defined, the problems remain unsolved.

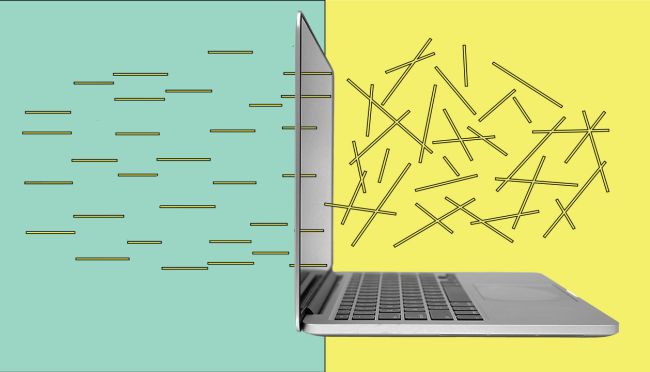

You may have seen the Project Management Tree Cartoon before ( Figure 1.4.1 ); it has been used and adapted widely to illustrate the perils of poor communication during a project.

The waste caused by imprecisely worded regulations or instructions, confusing emails, long-winded memos, ambiguously written contracts, and other examples of poor communication is not as easily identified as the losses caused by a bridge collapse or a flood. But the losses are just as real—in reduced productivity, inefficiency, and lost business. In more personal terms, the losses are measured in wasted time, work, money, and ultimately, professional recognition. In extreme cases, losses can be measured in property damage, injuries, and even deaths.

The following “case studies” show how poor communications can have real world costs and consequences. For example, consider the “ Comma Quirk ” in the Rogers Contract that cost $2 million. [3] A small error in spelling a company name cost £8.8 million. [4] Examine Edward Tufte’s discussion of the failed PowerPoint presentation that attempted to prevent the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster. [5] The failure of project managers and engineers to communicate effectively resulted in the deadly Hyatt Regency walkway collapse. [6] The case studies below offer a few more examples that might be less extreme, but much more common.

In small groups, examine each “case” and determine the following:

- Define the rhetorical situation : Who is communicating to whom about what, how, and why? What was the goal of the communication in each case?

- Identify the communication error (poor task or audience analysis? Use of inappropriate language or style? Poor organization or formatting of information? Other?)

- Explain what costs/losses were incurred by this problem.

- Identify possible solution s or strategies that would have prevented the problem, and what benefits would be derived from implementing solutions or preventing the problem.

Present your findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

Exercises adapted from T.M Georges’ Analytical Writing for Science and Technology. [7]

CASE 1: The promising chemist who buried his results

Bruce, a research chemist for a major petro-chemical company, wrote a dense report about some new compounds he had synthesized in the laboratory from oil-refining by-products. The bulk of the report consisted of tables listing their chemical and physical properties, diagrams of their molecular structure, chemical formulas and data from toxicity tests. Buried at the end of the report was a casual speculation that one of the compounds might be a particularly safe and effective insecticide.

Seven years later, the same oil company launched a major research program to find more effective but environmentally safe insecticides. After six months of research, someone uncovered Bruce’s report and his toxicity tests. A few hours of further testing confirmed that one of Bruce’s compounds was the safe, economical insecticide they had been looking for.

Bruce had since left the company, because he felt that the importance of his research was not being appreciated.

CASE 2: The rejected current regulator proposal

The Acme Electric Company worked day and night to develop a new current regulator designed to cut the electric power consumption in aluminum plants by 35%. They knew that, although the competition was fierce, their regulator could be produced more affordably, was more reliable, and worked more efficiently than the competitors’ products.

The owner, eager to capture the market, personally but somewhat hastily put together a 120-page proposal to the three major aluminum manufacturers, recommending that the new Acme regulators be installed at all company plants.

She devoted the first 87 pages of the proposal to the mathematical theory and engineering design behind his new regulator, and the next 32 to descriptions of the new assembly line she planned to set up to produce regulators quickly. Buried in an appendix were the test results that compared her regulator’s performance with present models, and a poorly drawn graph showed the potential cost savings over 3 years.

The proposals did not receive any response. Acme Electric didn’t get the contracts, despite having the best product. Six months later, the company filed for bankruptcy.

CASE 3: The instruction manual the scared customers away

As one of the first to enter the field of office automation, Sagatec Software, Inc. had built a reputation for designing high-quality and user-friendly database and accounting programs for business and industry. When they decided to enter the word-processing market, their engineers designed an effective, versatile, and powerful program that Sagatec felt sure would outperform any competitor.

To be sure that their new word-processing program was accurately documented, Sagatec asked the senior program designer to supervise writing the instruction manual. The result was a thorough, accurate and precise description of every detail of the program’s operation.

When Sagatec began marketing its new word processor, cries for help flooded in from office workers who were so confused by the massive manual that they couldn’t even find out how to get started. Then several business journals reviewed the program and judged it “too complicated” and “difficult to learn.” After an impressive start, sales of the new word processing program plummeted.

Sagatec eventually put out a new, clearly written training guide that led new users step by step through introductory exercises and told them how to find commands quickly. But the rewrite cost Sagatec $350,000, a year’s lead in the market, and its reputation for producing easy-to-use business software.

CASE 4: One garbled memo – 26 baffled phone calls

Joanne supervised 36 professionals in 6 city libraries. To cut the costs of unnecessary overtime, she issued this one-sentence memo to her staff:

After the 36 copies were sent out, Joanne’s office received 26 phone calls asking what the memo meant. What the 10 people who didn’t call about the memo thought is uncertain. It took a week to clarify the new policy.

CASE 5: Big science — Little rhetoric

The following excerpt is from Carl Sagan’s book, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, [8] itself both a plea for and an excellent example of clear scientific communication:

The Superconducting Supercollider (SSC) would have been the preeminent instrument on the planet for probing the fine structure of matter and the nature of the early Universe. Its price tag was $10 to $15 billion. It was cancelled by Congress in 1993 after about $2 billion had been spent — a worst of both worlds outcome. But this debate was not, I think, mainly about declining interest in the support of science. Few in Congress understood what modern high-energy accelerators are for. They are not for weapons. They have no practical applications. They are for something that is, worrisomely from the point of view of many, called “the theory of everything.” Explanations that involve entities called quarks, charm, flavor, color, etc., sound as if physicists are being cute. The whole thing has an aura, in the view of at least some Congresspeople I’ve talked to, of “nerds gone wild” — which I suppose is an uncharitable way of describing curiosity-based science. No one asked to pay for this had the foggiest idea of what a Higgs boson is. I’ve read some of the material intended to justify the SSC. At the very end, some of it wasn’t too bad, but there was nothing that really addressed what the project was about on a level accessible to bright but skeptical non-physicists. If physicists are asking for 10 or 15 billion dollars to build a machine that has no practical value, at the very least they should make an extremely serious effort, with dazzling graphics, metaphors, and capable use of the English language, to justify their proposal. More than financial mismanagement, budgetary constraints, and political incompetence, I think this is the key to the failure of the SSC.

CASE 6: The co-op student who mixed up genres

Chris was simultaneously enrolled in a university writing course and working as a co-op student at the Widget Manufacturing plant. As part of his co-op work experience, Chris shadowed his supervisor/mentor on a safety inspection of the plant, and was asked to write up the results of the inspection in a compliance memo . In the same week, Chris’s writing instructor assigned the class to write a narrative essay based on some personal experience. Chris, trying to be efficient, thought that the plant visit experience could provide the basis for his essay assignment as well.

He wrote the essay first, because he was used to writing essays and was pretty good at it. He had never even seen a compliance memo, much less written one, so was not as confident about that task. He began the essay like this:

On June 1, 2018, I conducted a safety audit of the Widget Manufacturing plant in New City. The purpose of the audit was to ensure that all processes and activities in the plant adhere to safety and handling rules and policies outlined in the Workplace Safety Handbook and relevant government regulations. I was escorted on a 3-hour tour of the facility by…

Chris finished the essay and submitted it to his writing instructor. He then revised the essay slightly, keeping the introduction the same, and submitted it to his co-op supervisor. He “aced” the essay, getting an A grade, but his supervisor told him that the report was unacceptable and would have to be rewritten – especially the beginning, which should have clearly indicated whether or not the plant was in compliance with safety regulations. Chris was aghast! He had never heard of putting the “conclusion” at the beginning . He missed the company softball game that Saturday so he could rewrite the report to the satisfaction of his supervisor.

- J. Bernoff, "Bad writing costs business billions," Daily Beast , Oct. 16, 2016 [Online]. Available: https://www.thedailybeast.com/bad-writing-costs-businesses-billions?ref=scroll ↵

- J. Reiter, "The 'Project Cartoon' root cause," Medium, 2 July 2019. Available: https://medium.com/@thx2001r/the-project-cartoon-root-cause-5e82e404ec8a ↵

- G. Robertson, “Comma quirk irks Rogers,” Globe and Mail , Aug. 6, 2006 [Online]. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/comma-quirk-irks-rogers/article1101686/ ↵

- “The £8.8m typo: How one mistake killed a family business,” (28 Jan. 2015). The Guardian [online]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/law/shortcuts/2015/jan/28/typo-how-one-mistake-killed-a-family-business-taylor-and-sons ↵

- E. Tufte, The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint , 2001 [Online]. Available: https://www.inf.ed.ac.uk/teaching/courses/pi/2016_2017/phil/tufte-powerpoint.pdf ↵

- C. McFadden, "Understanding the tragic Hyatt Regency walkway collapse," Interesting Engineering , July 4, 2017 [Online]: https://interestingengineering.com/understanding-hyatt-regency-walkway-collapse ↵

- T.M. Goerges (1996), Analytical Writing for Science and Technology [Online], Available: https://www.scribd.com/document/96822930/Analytical-Writing ↵

- C. Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, New York, NY: Random House, 1995. ↵

Technical Writing Essentials Copyright © 2019 by Suzan Last is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Verbal communication styles and culture.

- Meina Liu Meina Liu Department of Organizational Sciences and Communication, George Washington University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.162

- Published online: 22 November 2016

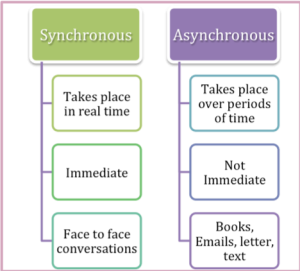

A communication style is the way people communicate with others, verbally and nonverbally. It combines both language and nonverbal cues and is the meta-message that dictates how listeners receive and interpret verbal messages. Of the theoretical perspectives proposed to understand cultural variations in communication styles, the most widely cited one is the differentiation between high-context and low-context communication by Edward Hall, in 1976. Low-context communication is used predominantly in individualistic cultures and reflects an analytical thinking style, where most of the attention is given to specific, focal objects independent of the surrounding environment; high-context communication is used predominantly in collectivistic cultures and reflects a holistic thinking style, where the larger context is taken into consideration when evaluating an action or event. In low-context communication, most of the meaning is conveyed in the explicit verbal code, whereas in high-context communication, most of the information is either in the physical context or internalized in the person, with very little information given in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message. The difference can be further explicated through differences between communication styles that are direct and indirect (whether messages reveal or camouflage the speaker’s true intentions), self-enhancing and self-effacing (whether messages promote or deemphasize positive aspects of the self), and elaborate and understated (whether rich expressions or extensive use of silence, pauses, and understatements characterize the communication). These stylistic differences can be attributed to the different language structures and compositional styles in different cultures, as many studies supporting the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis have shown. These stylistic differences can become, in turn, a major source of misunderstanding, distrust, and conflict in intercultural communication. A case in point is how the interethnic clash between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs can be exacerbated by the two diametrically opposite communication patterns they each have, dugri (straight talk) and musayra (to accommodate or “to go along with”). Understanding differences in communication styles and where these differences come from allows us to revise the interpretive frameworks we tend to use to evaluate culturally different others and is a crucial step toward gaining a greater understanding of ourselves and others.

- communication styles

- cultural values

- thinking styles

- high-context

- low-context

- communication accommodation

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Communication. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 16 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

Character limit 500 /500

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 Chapter 5 – Verbal Communication

Verbal communication.

“Sticks and stones might break my bones, but words will never hurt me!” ~childhood rhyme, am I the only one hurt?

Chapter Overview

A better understanding of how verbal symbols create meaning helps us move from the first unit of this course (“Who am I?”) to explore further the second unit’s focus on “Who are you?” When exploring cultures, many students wrote about how they fear they might offend others as they ask questions, seek new experiences or even try new phrases in a new language. However, no magic word or combination of terms (of one’s own or those of another culture) exists to reduce uncertainty and create commonly shared meaning. If even possible, this process itself is too complex. This chapter and the next show how verbal and nonverbal symbols provide that necessary interpersonal connection crucial to reaching intercultural communication competence. Conversely, they show how misunderstandings among those who genuinely attempt to communicate may pose a potentially insurmountable barrier or wall preventing conversation between cultures.

Those of an American or Western European culture express an open and direct communication style (e.g., speaking one’s mind). Thus, not considering another culture’s or co-cultures “outdated slang” or “offensive language” creates a barrier that causes some individuals to retreat and stay with what is known, familiar, and characteristic within their culture. However, withdrawing into their culture from an unsavory affront or fear of how to communicate appropriately also prevents them from learning new information and learning about other cultures. We encourage reading this chapter through the lens of asking, “how can this content help me become a better communicator?” When communicating, we risk “saying the wrong thing” and offending those who communicate differently. Yet, sharing talk time and thinking about how our language use can open doors or deny access is an essential consideration. We hope you will consider not just the theory of verbal communication and how sending and receiving verbal messages work but also how they often fail to work. Slowing down and considering what we say and when can help others feel safe, comforted, and a part of the communication situation.

The content of this chapter borrows from the Copywrite free, University of Minnesota’s Communication for the Real World. It contributes to what we will learn about the relationship between language and meaning, how we understand the content and rules of verbal communication within language functions, using words well, and the relationship between language and culture (2016). Additionally, the Cultural Atlas will provide examples of cultural differences and similarities in verbal (and nonverbal) communication. The authors of the Cultural Atlas include community experts and consultants from the communities and cultures described. One may or may not have the same perception of the “do’s and don’ts” of intercultural communication related to the Cultural Atlas, yet understanding its advice allows for constructive conversation and consideration.

Considering Words Spoken and the Silence of Others

Another area we hope to consider in this chapter is how one’s communication style, influenced by cultural norms and the learning of the language, positions one “at the conversing table?” For example, how might an American whose language and communication norms intentionally or unintentionally affect the conversations of those of different cultures? Americans are generally not so aware or sensitive to the “other,” and their worldview and communication style. People from low-context cultures value verbal communication. Additionally, Americans are generally more individualistic and more inclined to share their opinions straightforwardly up front, have much confidence in concrete physical or eyewitness evidence, and desire to quickly get to the point of the conversation. Indeed, the American style may be considered uncivil or rude by cultures that value long, thoughtful silence and consideration before contributing, are circular in using collective experience and context, prefer the cultural value of consensus and saving face, and thus are very sensitive to the straightforward American or Western style of an individualistic, often abrasive and self-serving communicative style. Later, in the last unit of this book, we’ll return to the topic of language when we discuss racism much more directly.

At the same time, in her TED Talk showcased in Chapter 4, America Verrea asserts that dominant and co-culture verbal interactions may be a basis to open, well-founded and genuine conversation. Think:

- “How can you make room for others to share their stories and lived experiences?”

- “Who speaks?”

- “Who does the conversation purposefully or unintentionally silence?”

Chapter Five Learning Outcomes

- Define Verbal Communication

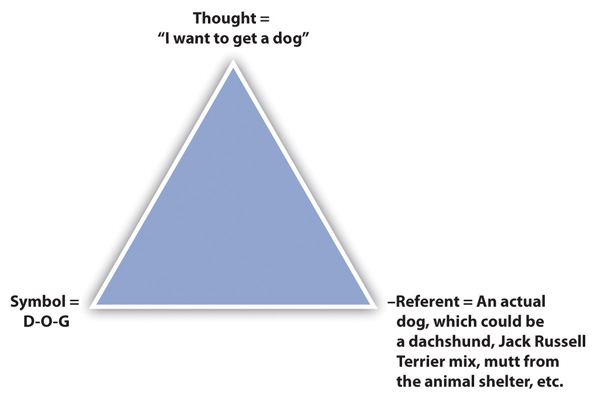

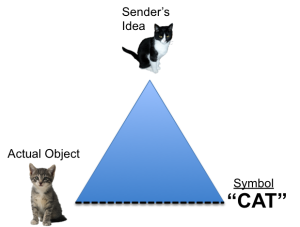

- Explain how the triangle of meaning describes the symbolic nature of language

- Distinguish between denotation and connotation

- Discuss the function of the rules of language

- Discuss how language can serve as a barrier and a bridge

- Distinguish between interpretation and translation

- Explore tips for becoming more effective in language use

- Define key terms related to allyship

Creating Meaning

Communication in the Real World (2016) outlines and explains language, focusing upon how meaning is created:

The relationship between language and meaning is not a straightforward one. One reason for this complicated relationship is the limitlessness of modern language systems like English (Crystal, 2005). Language is productive in the sense that there are an infinite number of utterances we can make by connecting existing words in new ways. In addition, there is no limit to a language’s vocabulary, as new words are coined daily. Of course, words aren’t the only things we need to communicate, and although verbal and nonverbal communication are closely related in terms of how we make meaning, nonverbal communication is not productive and limitless. Although we can only make a few hundred physical signs, we have about a million words in the English language. So with all this possibility, how does communication generate meaning? You’ll recall that “generating meaning” was a central part of the definition of communication we learned earlier. We arrive at meaning through the interaction between our nervous and sensory systems and some stimulus outside of them. It is here, between what the communication models we discussed earlier labeled as encoding and decoding, that meaning is generated as sensory information is interpreted. The indirect and sometimes complicated relationship between language and meaning can lead to confusion, frustration, or even humor. We may even experience a little of all three, when we stop to think about how there are some twenty-five definitions available to tell us the meaning of word meaning (Crystal, 2005)! Since language and symbols are the primary vehicle for our communication, it is important that we not take the components of our verbal communication for granted.

Verbal Communication Defined

Central to the definition of language is that a community shares words or symbols to communicate meaning within various contexts. On a deeper level, language is symbolic. Samovar, et. al defines language as “a shared set of symbols or signs that a cooperative group has mutually agreed to use to help create meaning.”

Symbols stand in for or are representative of something else. Verbal communication uses words that arise within a cultural (or intercultural) context. Again, words are symbolic of the thing or idea it represents. As Communication in the Real World puts it:

Symbols can be communicated verbally (speaking the word “Hello”), in writing (putting the letters H-E-L-L-O together to make an understood communicative whole), or nonverbally (waving your hand back and forth). In any case, we use symbols, verbally and nonverbally, to stand in for something else, like a physical object or an idea; symbols do not actually correspond to the thing being referenced in any direct way, i.e., the word “stone” is symbolic and not the thing in actuality (2016).

As noted above, verbal communication is our language use. In intercultural communication, there may exist either an entirely different language use, a person using a second language, or even both individuals communicating in a common second language.

Speaking in a different language gives one another way of thinking – a new outlook or worldview different from that which one has been acculturated . Jordan, a Rochester Community and Technical College Alum, pursued his master’s degree in Denmark. Because of the number of international students attending, the college used English as the common currency of language. However, as one of his college majors was Spanish, he soon found himself drawn to speaking Spanish with his classmates from Spanish-speaking countries. Doing so, i.e., becoming fluent in a second language, gave him access to another worldview leading to a commonality or shared understanding of norms, behaviors, and practices that allowed him to make special bonds that would otherwise be closed.

The symbols we use combine to form language systems or codes . Codes are culturally agreed on and ever-changing systems of symbols that help us organize, understand and generate meaning (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1993). There are about 6,000 language codes used in the world, and around 40 percent of those (2,400) are only spoken and do not have a written version (Crystal, 2005). Remember that for most of human history the spoken word and nonverbal communication were the primary means of communication. Even languages with a written component didn’t see widespread literacy, or the ability to read and write, until a little over one hundred years ago.

Symbolic Nature of Language

Communication in the Real World (2016) examines the symbolic nature of language:

The symbolic nature of our communication is a quality unique to humans. Since the words we use do not have to correspond directly to a ‘thing” in our “reality’ we can communicate in abstractions. This property of language is called displacement and specifically refers to our ability to talk about events that are removed in space or time from a speaker and situation (Crystal, 2005). …The earliest human verbal communication was not very symbolic or abstract, as it likely mimicked sounds of animals and nature. Such a simple form of communication persisted for thousands of years, but as later humans turned to settled agriculture and populations grew, things needed to be more distinguishable. More terms (symbols) were needed to accommodate the increasing number of things like tools and ideas like crop rotation that emerged as a result of new knowledge about and experience with farming and animal domestication. There weren’t written symbols during this time, but objects were often used to represent other objects; for example, a farmer might have kept a pebble in a box to represent each chicken he owned. As further advancements made keeping track of objects-representing-objects more difficult, more abstract symbols and later written words were able to stand in for an idea or object. Despite the fact that these transitions occurred many thousands of years ago, we can trace some words that we still use today back to their much more direct and much less abstract origins ( Communication in the Real World , 2016).

Naming: Case Study of Language’s ability to Define

In many cultures, knowing and publicly pronouncing one’s name (the symbolic representation of one’s cultural and personal identity ) is essential. Through language and communication, naming, at root, shapes who one understands themselves to be, hence helping to create/construct both the individual self and one’s group or cultural identity. Language itself “…is intrinsically related to culture [and] performs the social function of communication of the group’s [culture’s] values, beliefs, and customs and fosters group identity” (Bakhtin, 1981). In other words, language is the medium through which groups or cultures preserve their firmly held beliefs and keep their traditions alive in the hearts and minds of their members. Language and names are vital.

Regarding names, perhaps a short nickname can help others when a name is hard to pronounce and can help one remember a person. Still, if the nickname is not preferred or given with love, its sound to its’ possessor can be as annoying as hearing nails scraping across a chalkboard.

Being called “Jimmy” by one’s grandmother when friends and work associates call him “James” could be endearing but most likely embarrassing if James is called Jimmy at work. Having one’s mother come to her son’s place of work asking loudly, “Is my Baby J in the office?” might be another example. The point is that names are personal and defining. They are also verbal symbols. Symbols stand for something else and allow us to communicate due to the meaning attached to the symbol. All symbolic use is dynamic, meaning fluid, and often powerful. Think about when a bully purposefully calls someone a name. Calling another “fattie” or “blubber butt” takes a toll on the bully’s victim. Whether renaming is out of spite, like the bully example, or perhaps misplaced affection, like being called Baby J, if it is not one’s desired name, one might feel that one is not being “acknowledged” or “affirmed,”–a feeling of disconfirmation arises. This feeling can impact the relationship itself.

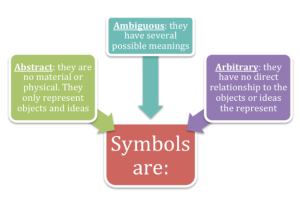

Symbols are Arbitrary, Ambiguous, and Abstract

- Ambiguous – symbols–or words– have several possible meanings, which often change over time.

- Abstract – words are not material, physical, or have any innate connection to reality. Language is symbolic and uses words to represent objects and ideas .

- Arbitrary – symbols have no direct relationship to the objects or ideas they represent. (Indiana State Department of COMM, 2016)

Example of the Importance of Understanding how Language Works

Interpersonal Communication examines how communication creates confirming or disconfirming communication climates. We experience “Confirming Climates when we receive messages that demonstrate our value and worth from those with whom we have a relationship,” [and], “[c]onversely, we experience Disconfirming Climates when we receive messages that suggest we are devalued and unimportant” (Rice, 2019, pp. 124-125). Disconfirmation leads to feeling objectified or regarded as the “other,” apart from and foreign to one’s own culture and personal experience. Therefore, calling someone as they would like helps create a supportive climate where respectful and impactful intercultural communication can occur. If we generalize and move toward this same treatment to a culture, that too might help create more a supportive environment for intercultural communication. If we see a person or group of people as the Other–apart from us and unknown to us–it may lead to dehumanization. Dehumanization includes “The denial of full humanness to others, and the cruelty and suffering that accompany it” ( Haslam, 2006 ). An example of dehumanization (also highlighted below in the topics section) is the not-so-distant practice of sending Native American children to boarding schools. In the Indian Civilization Act Fund of March 3, 1819, and the Peace Policy of 1869, the United States (along with many Christian churches) allowed for the removal of Native American children from their homes and families so they could be appropriately educated and stripped of their own culture in boarding (or residential) schools (“ U.S. Indian boarding school history,” n.d. ). “Between 1869 and the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were removed from their homes and families and placed in boarding schools operated by the federal government and participating churches. It is unknown exactly how many children in total lived in such schools, but by 1900 there were 20,000 children in Indian boarding schools, and by 1925 that number had more than tripled” (“ U.S. Indian boarding school history,” n.d. ).

Becky Little (2017) remarked that this federal effort toward assimilation mandated that “… boarding schools forbid Native American children from using their languages and names, as well as from practicing their religion and culture. They were given new Anglo-American names, clothes, and haircuts and told they must abandon their way of life because it was inferior to white people’s.” Though the schools “….left a devastating legacy, they failed to eradicate Native American cultures as they’d hoped.” Later, the Navajo Code Talk ers who helped the U.S. win World War II would reflect on this forced assimilation’s strange irony in their lives ( 2017 ).

What terms to use?

In his teaching resource, Why Treaties Matter: Terminology Primer (n.d.), Dr. Anton Treuer addresses the confusion surrounding which term to use — “Native American,” “Native,” “Indigenous,” or “American Indian.” There is no one correct answer or term to use, as seen below. Confusion arises due to the notion of language ambiguity. Ambiguity refers to the idea that symbols have several different meanings. The reverse is true too. We have many different symbols to refer to the same referent; e.g., soda, pop, soda pop, and coke can all refer to the same beverage one might be drinking, even if it is “7-up!” The beverage itself is the “referent” or thing being referred to; the symbol is the word used to refer to it. Recall that the nature of language is ambiguous, arbitrary, and abstract . It is not surprising that the language used to name such a large group of individuals from 574 different nations registered in the United States would be hard to determine. Dr. Treuer (n.d.) explains, “This is an area of confusion for many people. Christopher Columbus thought for a long time that he landed in Asia when he first arrived here—China, Japan, India. And from there the term Indian was applied to the peoples of the Americas. It is a misnomer, even if it wasn’t intended to offend. Some native people object to the word because it was applied in error. But some really do prefer the term, including some official organizations like the National Congress of American Indians and the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council. Native American is broadly considered a little more politically correct, even if it isn’t universally embraced. But it can cause confusion in certain circumstances. Is a St. Paul native a Native American from St. Paul or just someone ‘born and bred,’ so to speak? Indigenous is increasingly taking the place of Native American, and some scholars really like the way it draws connections to other groups, but again there is an issue of ambiguity. There are people indigenous to every continent except Antarctica and they are all different. It gets a little long to always say ‘indigenous people of North America.’ Aboriginal was preferred for a while in Canada, although it got confused with Australian aborigine. I tend to use all of these terms fairly interchangeably, aware of their shortcomings… If you know the story behind the words, all you really need is respect in your heart and an open mind” (p. 1).

Suggestions on how to use language respectfully are highlighted in the shared curricular materials from the “Quick Links” resource from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (n.d.):

- “American Indian, Indian, Native American, or Native are acceptable and often used interchangeably in the United States; however, Native Peoples often have individual preferences on how they would like to be addressed. To find out which term is best, ask the person or group which term they prefer.”

- “When talking about Native groups or people, use the terminology the members of the community use to describe themselves collectively.”

- “There are also several terms used to refer to Native Peoples in other regions of the Western Hemisphere. The Inuit, Yup’ik, and Aleut Peoples in the Arctic see themselves as culturally separate from Indians. In Canada, people refer to themselves as First Nations, First Peoples, or Aboriginal. In Mexico, Central America, and South America, the direct translation for Indian can have negative connotations. As a result, they prefer the Spanish word indígena (Indigenous), communidad (community), and pueblo (people).”

In defining privilege, the University Libraries at Rider University (2022) share,

“Privilege” refers to certain social advantages, benefits, or degrees of prestige and respect that an individual has by virtue of belonging to certain social identity groups. Within American and other Western societies, these privileged social identities—of people who have historically occupied positions of dominance over others—include whites, males, heterosexuals, Christians, and the wealthy, among others. García, Justin D. 2018. “Privilege (Social Inequality).” Salem Press Encyclopedia .

Nccj.org (2022) shares:

Privilege: Unearned access to resources (social power) that are only readily available to some people because of their social group membership; an advantage, or immunity granted to or enjoyed by one societal group above and beyond the common advantage of all other groups. Privilege is often invisible to those who have it.

We will expand upon Native American cultures later in this textbook.

*Photo credit: Native American (Chiricahua Apache) boys and girls at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, after they arrived from Fort Marion, Florida, in November 1886. Photo by J. N. Choate/Creative Commons

Consider the Boarding School Experience

Reflection Questions:

- If your language was forbidden, how would that change your worldview?

- How does the nonverbal action of cutting the students’ hair dehumanize the students?

- In this instance, communication rules are created. Children are allowed limited access to communication with their family members. How does the lack of communication, verbal and nonverbal, impact the children’s cultural identity formation?

- What is your reaction to this video? Do words matter?

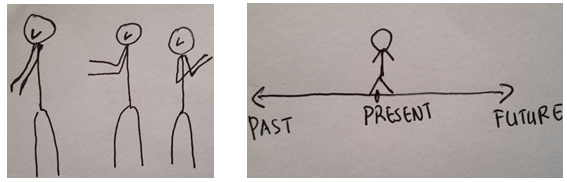

The Triangle of Meaning

Communication in the Real World (2016) explains the triangle of meaning:

The triangle of meaing is a model of communication that indicates the relationship among a thought, symbol, and referent and highlights the indirect relationship between the symbol and referent (Richards & Ogden, 1923). As you can see in Figure 3.1 “Triangle of Meaning,” the thought is the concept or idea a person references. The symbol is the word that represents the thought, and the referent is the object or idea to which the symbol refers. This model is useful for us as communicators because when we are aware of the indirect relationship between symbols and referents, we are aware of how common misunderstandings occur, as the following example illustrates: Jasper and Abby have been thinking about getting a new dog. So each of them is having a similar thought. They are each using the same symbol, the word dog , to communicate about their thought. Their referents, however, are different. Jasper is thinking about a small dog like a dachshund, and Abby is thinking about an Australian shepherd. Since the word dog doesn’t refer to one specific object in our reality, it is possible for them to have the same thought, and use the same symbol, but end up in an awkward moment when they get to the shelter and fall in love with their respective referents only to find out the other person didn’t have the same thing in mind.

Source: Adapted from Ivor A. Richards and Charles K. Ogden, The Meaning of Meaning (London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Tubner, 1923). Being aware of this indirect relationship between symbol and referent , we can try to compensate for it by getting clarification. Some of what we learned in the last chapter about perception checking, can be useful here. Abby might ask Jasper, “What kind of dog do you have in mind?” This question would allow Jasper to describe his referent, which would allow for more shared understanding. If Jasper responds, “Well, I like short-haired dogs. And we need a dog that will work well in an apartment,” then there’s still quite a range of referents. Abby could ask questions for clarification, like “Sounds like you’re saying that a smaller dog might be better. Is that right?” Getting to a place of shared understanding can be difficult, even when we define our symbols and describe our referents.

Just when you think you know a word, you find that there are other phrases or words to replace it. Once we learned how to make what we called, “eggplant sauce,” we realized that a much more “sophisticated” version of “sauce” is called, “Baba Ganoush.” Recently, Lori asked our son to pass the “humus” only to be told, no, it’s eggplant, so it is called, “Baba Ganoush.” However, whatever it is called, humus, eggplant sauce, eggplant-ish-humus dish, or “Baba Ganoush,” the referent is still the same. This reminds us of the phrase from Shakespeare, “ a rose by any other name ….”

Definitions

Words can be defined in different manners. Communication in the Real Word (2016) explains:

Definitions help us narrow the meaning of particular symbols, which also narrows a symbol’s possible referents. They also provide more words (symbols) for which we must determine a referent. If a concept is abstract and the words used to define it are also abstract, then a definition may be useless. Have you ever been caught in a verbal maze as you look up an unfamiliar word, only to find that the definition contains more unfamiliar words? Although this can be frustrating, definitions do serve a purpose. Words have denotative and connotative meanings. Denotation refers to definitions that are accepted by the language group as a whole, or the dictionary definition of a word. For example, the denotation of the word cowboy is a man who takes care of cattle. Another denotation is a reckless and/or independent person. A more abstract word, like change , would be more difficult to understand due to the multiple denotations. Since both cowboy and change have multiple meanings, they are considered polysemic words. Monosemic words have only one use in a language, which makes their denotation more straightforward. Specialized academic or scientific words, like monosemic , are often monosemic, but there are fewer commonly used monosemic words, for example, handkerchief . As you might guess based on our discussion of the complexity of language so far, monosemic words are far outnumbered by polysemic words. Connotation refers to definitions that are based on emotion- or experience-based associations people have with a word. To go back to our previous words, change can have positive or negative connotations depending on a person’s experiences. A person who just ended a long-term relationship may think of change as good or bad depending on what he or she thought about his or her former partner. Even monosemic words like handkerchief that only have one denotation can have multiple connotations. A handkerchief can conjure up thoughts of dainty Southern belles or disgusting snot-rags. A polysemic word like cowboy has many connotations, and philosophers of language have explored how connotations extend beyond one or two experiential or emotional meanings of a word to constitute cultural myths (Barthes, 1972). Cowboy , for example, connects to the frontier and the western history of the United States, which has mythologies associated with it that help shape the narrative of the nation. The Marlboro Man is an enduring advertising icon that draws on connotations of the cowboy to attract customers. While people who grew up with cattle or have family that ranch may have a very specific connotation of the word cowboy based on personal experience, other people’s connotations may be more influenced by popular cultural symbolism like that seen in westerns. [Lori and Mark: the example above is from the textbook Communication in the Real World (2016). How might this example be offensive or worrisome to individuals who are Indiginous?]

Think about it, Apply it: How have you used words used in the examples above? Think about “cowboy” and how that connotation above has changed as we think about “playing cowboys and Indians.” Does this term take on a type of “good ole’ boy” now compared to the 1970’s game Mark and Lori played? When searching for a video to embed, so many home videos of men shooting each other with paint guns/air guns were evident. Related Reading Here

Connotative and Denotative Meaning: Case Study

The following brief news report shares the importance of thinking about the words we use. Many common phrases, euphemisms, cliches, and individual words may come across as simple but carry serious racial impacts for people of color” (YouTube Description).

Language Is Learned

Communication in the Real Word (2016) examines how language is learned and explains the rules of language as quoted below:

As we just learned, the relationship between the symbols that make up our language and their referents is arbitrary, which means they have no meaning until we assign it to them. In order to effectively use a language system, we have to learn, over time, which symbols go with which referents, since we can’t just tell by looking at the symbol. Like me, you probably learned what the word apple meant by looking at the letters A-P-P-L-E and a picture of an apple and having a teacher or caregiver help you sound out the letters until you said the whole word. Over time, we associated that combination of letters with the picture of the red delicious apple and no longer had to sound each letter out. This is a deliberate process that may seem slow in the moment, but as we will see next, our ability to acquire language is actually quite astounding. We didn’t just learn individual words and their meanings, though; we also learned rules of grammar that help us put those words into meaningful sentences (2016).

The Rules of Language

Any language system has to have rules to make it learnable and usable. Grammar refers to the rules that govern how words are used to make phrases and sentences. Someone would likely know what you mean by the question “Where’s the remote control?” But “The control remote where’s?” is likely to be unintelligible or at least confusing (Crystal, 2005). Knowing the rules of grammar is important in order to be able to write and speak to be understood, but knowing these rules isn’t enough to make you an effective communicator. As we will learn later, creativity and play also have a role in effective verbal communication. Even though teachers have long enforced the idea that there are right and wrong ways to write and say words, there really isn’t anything inherently right or wrong about the individual choices we make in our language use. Rather, it is our collective agreement that gives power to the rules that govern language. Some linguists have viewed the rules of language as fairly rigid and limiting in terms of the possible meanings that we can derive from words and sentences created from within that system (de Saussure, 1974). Others have viewed these rules as more open and flexible, allowing a person to make choices to determine meaning (Eco, 1976). Still others have claimed that there is no real meaning and that possibilities for meaning are limitless (Derrida, 1978). For our purposes in this chapter, we will take the middle perspective, which allows for the possibility of individual choice but still acknowledges that there is a system of rules and logic that guides our decision making. Looking back to our discussion of connotation, we can see how individuals play a role in how meaning and language are related, since we each bring our own emotional and experiential associations with a word that are often more meaningful than a dictionary definition. In addition, we have quite a bit of room for creativity, play, and resistance with the symbols we use. Have you ever had a secret code with a friend that only you knew? This can allow you to use a code word in a public place to get meaning across to the other person who is “in the know” without anyone else understanding the message. The fact that you can take a word, give it another meaning, have someone else agree on that meaning, and then use the word in your own fashion clearly shows that meaning is in people rather than words. As we will learn later, many slang words developed because people wanted a covert way to talk about certain topics like drugs or sex without outsiders catching on.

Think about it – Apply It

Take the link here to the Cultural Atlas . Find 3 rules for 3 different culture’s in the Do’s and Don’t section of the country’s profile. How do the rules vary? How are they similar? Look at the rules for “American Culture.” What is interesting is this website is from Australia. Like Australia, the United States is a large country geographically. Like Australia, individuals immigrated to the US to seek a better life. Similarly, others came with a forced choice through slavery or indentured servitude. Do the “Do’s and Don’ts” for the United States represent the culturally diverse country in which we live? Is the list most representative of the dominant culture? What might you change, add, or delete from this list? In our weekly discussion, we’ll address the same questions and even send feedback to this site’s editors and content authors.

Language Defines

The defining ability of language relates to intercultural communication and barriers, such as stigma, that language can impose. Goffman along with Galinsky, A. D., Hugenberg, K., Groom, C., & Bodenhausen, G. (2003), explains the power of stigma:

creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com Stigma, according to Goffman, an attribute that discredits and reduces the person ‘from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one’ (Goffman, 1963, p. 3). Social stigma links a negatively valued attribute to a social identity or group membership. Stigma is said to exist when individuals ‘possess (or are believed to possess) some attribute, Stigma or characteristic, that conveys a social identity that is devalued in a particular social context’ (Crocker, Major & Steele, 1998, p.505). Given these criteria, there are myriad groups in our own culture that tend to be the reappropriation of stigmatizing labels considered stigmatized. Marginalized groups, such as African Americans or Native Americans, persons with physical or mental disabilities, LGBTQ indentifying individuals, and the obese can all be considered stigmatized groups. To be stigmatized often means to be economically disadvantaged, to be the target of negative stereotypes, and to be rejected interpersonally (Crocker, Voelkl, Testa & Major, 1998). Name calling (Smythe & Seidman, 1957) may be a favorite strategy for calling forth these harmful sequelae of stigma (pp. 224-225).

While stigmatizing language generally comes from persons in positions of “privilege” to define others in some way (remember social capital can equal privilege too), systematic policy, language structure, and attitudes can also create damaging language. Think of individuals with disabilities being called “crippled” or how often one hears, “Oh, that is handicapped parking.” Remember the person first – the “person with a disability” is not a “disabled person” simply. The order of the words can demonstrate an emphasis upon the person. Another example is the stigma surrounding how individuals with a mental health diagnosis are called: crazy, insane, mentally ill, nuts, loco, etc. Moving past the stigmatized “other” and into a healthy image means re-evaluating the language used to name, define, detain, diagnose, and otherwise label others. We live in an era where the listing of pronouns or other inclusive language choices are often quickly dismissed as politically correct and careless. Moreover, “Can’t you take a joke?” statements come from our own leaders after making racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic or otherly offensive phases. Making a personal choice to avoid words that cause offense or poorly define others is one way to practice compassion and intercultural communication competence.

Galinsky, A. D., Hugenberg, K., Groom, C., & Bodenhausen, G. (2003) further examine how labels can be “reappropriated” to change the meaning of the word, if only for the person themselves:

creative commons photo from burst.shopify.com Given that to appropriate means “to take possession of or make use of exclusively for oneself,” we consider reappropriate to mean to take possession for oneself that which was once possessed by another, and we use it to refer to the phenomenon whereby a stigmatized group revalues an externally imposed negative label by selfconsciously referring to itself in terms of that label. Instead of passively accepting the negative connotative meanings of the label, …[one can reject] those damaging meanings and through reappropriation imbued the label with positive connotations. By reappropriating this negative label, …[one can seek] to renegotiate the meaning of the word, changing it from something hurtful to something empowering…[Such] actions imply two assumptions that are critical to reappropriation. First, names are powerful, and second, the meanings of names are subject to change and can be negotiated and renegotiated (p. 222).

Reappropriation of language is often confusing and nebulous. As one mindfully decides (or not) to use terms in new ways, remember, many times others outside a peer group, co-culture or culture may not understand. For example, the true meaning of a female calling another female friend a “bitch” to reappropriate the term and give it a “hip” or “warrior-goddess” sound might be lost on the average passerby who might, then, believe it is acceptable for him or her to likewise use such language.

Case Study: What is Privilege?

Language Is Dynamic

The authors of Communication in the Real World (2016) help us understand how reappropriation occurs as a function of language being “dynamic.” They explain the nature of neologisms and slang as shared below:

As we already learned, language is essentially limitless. We may create a one-of-a-kind sentence combining words in new ways and never know it. Aside from the endless structural possibilities, words change meaning, and new words are created daily. In this section, we’ll learn more about the dynamic nature of language by focusing on neologisms and slang.

Neologisms Neologisms are newly coined or used words. Newly coined words are those that were just brought into linguistic existence. Newly used words make their way into languages in several ways, including borrowing and changing structure. Taking is actually a more fitting descriptor than borrowing , since we take words but don’t really give them back. In any case, borrowing is the primary means through which languages expand. English is a good case in point, as most of its vocabulary is borrowed and doesn’t reflect the language’s Germanic origins. English has been called the “vacuum cleaner of languages” (Crystal, 2005). Weekend is a popular English word based on the number of languages that have borrowed it. We have borrowed many words, like chic from French, karaoke from Japanese, and caravan from Arabic. Structural changes also lead to new words. Compound words are neologisms that are created by joining two already known words. Keyboard , newspaper , and giftcard are all compound words that were formed when new things were created or conceived. We also create new words by adding something, subtracting something, or blending them together. For example, we can add affixes, meaning a prefix or a suffix, to a word. Affixing usually alters the original meaning but doesn’t completely change it. Ex-husband and kitchenette are relatively recent examples of such changes (Crystal, 2005). New words are also formed when clipping a word like examination , which creates a new word, exam , that retains the same meaning. And last, we can form new words by blending old ones together. Words like breakfast and lunch blend letters and meaning to form a new word— brunch . Existing words also change in their use and meaning. The digital age has given rise to some interesting changes in word usage. Before Facebook, the word friend had many meanings, but it was mostly used as a noun referring to a companion. The sentence, I’ll friend you , wouldn’t have made sense to many people just a few years ago because friend wasn’t used as a verb. Google went from being a proper noun referring to the company to a more general verb that refers to searching for something on the Internet (perhaps not even using the Google search engine). Meanings can expand or contract without changing from a noun to a verb. Gay , an adjective for feeling happy, expanded to include gay as an adjective describing a person’s sexual orientation. Perhaps because of the confusion that this caused, the meaning of gay has contracted again, as the earlier meaning is now considered archaic, meaning it is no longer in common usage. The American Dialect Society names an overall “Word of the Year” each year and selects winners in several more specific categories. The winning words are usually new words or words that recently took on new meaning. [2] In 2011, the overall winner was occupy as a result of the Occupy Wall Street movement. The word named the “most likely to succeed” was cloud as a result of Apple unveiling its new online space for file storage and retrieval. Although languages are dying out at an alarming rate, many languages are growing in terms of new words and expanded meanings, thanks largely to advances in technology, as can be seen in the example of cloud .

Slang Slang is a great example of the dynamic nature of language. Slang refers to new or adapted words that are specific to a group, context, and/or time period; regarded as less formal; and representative of people’s creative play with language. Research has shown that only about 10 percent of the slang terms that emerge over a fifteen-year period survive. Many more take their place though, as new slang words are created using inversion, reduction, or old-fashioned creativity (Allan & Burridge, 2006). Inversion is a form of word play that produces slang words like sick , wicked , and bad that refer to the opposite of their typical meaning. Reduction creates slang words such as pic , sec , and later from picture , second , and see you later . New slang words often represent what is edgy, current, or simply relevant to the daily lives of a group of people. Many creative examples of slang refer to illegal or socially taboo topics like sex, drinking, and drugs. It makes sense that developing an alternative way to identify drugs or talk about taboo topics could make life easier for the people who partake in such activities. Slang allows people who are in “in the know” to break the code and presents a linguistic barrier for unwanted outsiders. Taking a moment to think about the amount of slang that refers to being intoxicated on drugs or alcohol or engaging in sexual activity should generate a lengthy list. When I first started teaching this course in the early 2000s, Cal Poly Pomona had been compiling a list of the top twenty college slang words of the year for a few years. The top slang word for 1997 was da bomb , which means “great, awesome, or extremely cool,” and the top word for 2001 and 2002 was tight , which is used as a generic positive meaning “attractive, nice, or cool.” Unfortunately, the project didn’t continue, but I still enjoy seeing how the top slang words change and sometimes recycle and come back. I always end up learning some new words from my students. When I asked a class what the top college slang word should be for 2011, they suggested deuces , which is used when leaving as an alternative to good-bye and stems from another verbal/nonverbal leaving symbol—holding up two fingers for “peace” as if to say, “peace out.” It’s difficult for my students to identify the slang they use at any given moment because it is worked into our everyday language patterns and becomes very natural. Just as we learned here, new words can create a lot of buzz and become a part of common usage very quickly. The same can happen with new slang terms. Most slang words also disappear quickly, and their alternative meaning fades into obscurity. For example, you don’t hear anyone using the word macaroni to refer to something cool or fashionable. But that’s exactly what the common slang meaning of the word was at the time the song “Yankee Doodle” was written. Yankee Doodle isn’t saying the feather he sticks in his cap is a small, curved pasta shell; he is saying it’s cool or stylish.

Language Is Relational

Communication in the Real Word (2016) shares:

We use verbal communication to initiate, maintain, and terminate our interpersonal relationships. The first few exchanges with a potential romantic partner or friend help us size the other person up and figure out if we want to pursue a relationship or not. We then use verbal communication to remind others how we feel about them and to check in with them—engaging in relationship maintenance through language use. When negative feelings arrive and persist, or for many other reasons, we often use verbal communication to end a relationship.

Language Can Bring Us Together

Communication in the Real Word (2016) examines the ability of language that unites. As you look to the Cultural Atlas , consider whether the culture’s norms promote these concepts:

Interpersonally, verbal communication is key to bringing people together and maintaining relationships. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, our use of words like I , you , we , our , and us affect our relationships. “We language” includes the words we , our , and us and can be used to promote a feeling of inclusiveness. “I language” can be useful when expressing thoughts, needs, and feelings because it leads us to “own” our expressions and avoid the tendency to mistakenly attribute the cause of our thoughts, needs, and feelings to others. Communicating emotions using “I language” may also facilitate emotion sharing by not making our conversational partner feel at fault or defensive. For example, instead of saying, “You’re making me crazy!” you could say, “I’m starting to feel really anxious because we can’t make a decision about this.” Conversely, “you language” can lead people to become defensive and feel attacked, which could be divisive and result in feelings of interpersonal separation.