Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Tips for Students > What Is Intercultural Communication: Learning New Styles

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

What Is Intercultural Communication: Learning New Styles

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: April 30, 2020

Intercultural communication is a necessary part of today’s world, whether in business, school, or everyday life. It is essential in being a part of the growing global community and knowing how to communicate cross-culturally is a skill you must have to succeed. But just what is intercultural communication? Let’s dive into what is intercultural communication, and how you can increase your intercultural communication skills to succeed in whatever you set your mind to.

Cultures Meet Communication

Everyone communicates, and everyone has a culture, whether it is highly defined or not. This means that inherently, we all must communicate with people of other cultures. That is what intercultural communication is all about.

Photo by fauxels from Pexels

Defining culture.

Culture isn’t only about the language you speak, the foods you eat, and the way you dress. There are much more nuanced aspects of our everyday life that can be attributed to culture. Our lifestyle, including ways of personal life, family life, and social life are all part of our culture .

Introducing Intercultural Communication

If you are just beginning your journey of intercultural competence, it can be confusing where to start. One of the best ways to introduce yourself is to start with the concept of intercultural communication, discussed below.

What Is Intercultural Communication?

Intercultural communication is much more than just your typical types of communication such as verbal and nonverbal. It is about the broader exchange of ideas, beliefs, values, and views.

Cultural values impact how people speak, write, and act — all essential aspects of communication. Culture also has a lot to do with how people think about and judge other people. Being aware of our own cultural biases, and others’ biases goes a long way in being able to effectively communicate with anyone.

Other Intergroup Relations Terms

Other relevant terms when discussing intercultural communication are multicultural, diversity, and cross-cultural. While these all might seem to be the same, there are small differences that make each unique.

Multicultural means a group or organization that has multiple cultures within it, or is made up of several cultures. Cross-cultural means between multiple groups of different cultures, whereas intercultural means between members of those cultures.

To further clarify, a company might be multicultural, where it fosters many cross-cultural interactions, which means everyone has to be involved in intercultural communication.

Importance Of Intercultural Communication

Intercultural communication is an important part of intercultural competence — or the ability to effectively function across cultures , and with those from other cultures. As our world gets smaller and globalization gets stronger, intercultural competence and great intercultural communication become a necessity to be successful.

Photo by nappy from Pexels

Applying and managing intercultural communication.

Intercultural communication skills must be applied when you are in an intercultural exchange. Use these 7 tips when managing intercultural communication:

1. Common Traps And Problems

Every culture has their own gestures and ways of speaking. If you know in advance that you will be speaking to a person or group of another culture, it’s important to educate yourself on some common faux-pas of that culture.

For example, a handshake may not be the appropriate way of greeting in every culture. Similarly, Spanish speakers find that specific words can have either neutral or negative meanings depending on the country you are in.

2. Learn Phrases In Their Language

Learning a few common phrases in another language is an important part of intercultural communication. It shows that you recognize the cultural difference, respect their culture, and are willing to learn about it. Start with learning hello and thank you if you are meeting with someone you know speaks another language.

3. Adapt Your Behavior

When you enter in an intercultural communication exchange, there may be an expectation on both sides for the other party to adapt to the others’ cultures. If you stop expecting that, and start adapting your own behavior, you will find more willingness on both sides to understand one another.

4. Check Your Understanding

Listen carefully and check your own understanding regularly throughout the conversation. If you find you aren’t able to articulate back what the other person is saying, don’t be afraid to ask for clarification. It’s better to ask than to walk away with misunderstandings.

5. Apologize

If you realize you have offended someone, apologize promptly — don’t let it fester or become awkward. It’s better to apologize without needing to than leave someone feeling bad after your conversation.

6. Use Television

Watching series of other cultures can really aid you in intercultural understanding if you have no other way to access that culture. It will help you see cultural norms and how another culture lives, all which will help you effectively communicate with that culture.

7. Reflect On Experience

Try to take a few moments to reflect on previous intercultural exchanges — ones of your own or ones you have simply observed. What made them effective, or what made them not work out the way it was intended? Take note and adjust your future communication accordingly.

Communicating With People Of Different Cultures

Communication across cultures can be a challenge, especially if you’re not accustomed to working with people from other cultures.

Photo by Magda Ehlers from Pexels

An understanding of difference.

First, in order to effectively communicate with people of other cultures, there is a fundamental aspect you must be aware of which is understanding differences. Different cultures have different standards, expectations, and norms, and you must realize that those differences shape individuals in some ways but they are not bound by those ways.

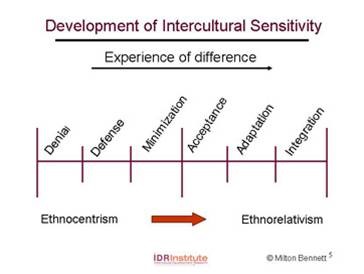

Developing Intercultural Sensitivity And Competence

By default, we automatically feel something different when we interact with someone from an unfamiliar culture, or one that is starkly different than our own. If you want to increase your intercultural communication abilities, it is up to you to work on your intercultural sensitivity.

It starts with the idea that as you begin to recognize and understand cultural differences and the more you interact with people of other cultures, the more competent you become and the more complex your ideas of culture become as well. Therefore, the more sensitive you will be each time you communicate interculturally.

Intercultural Communication At University Of The People

University of the People is an American accredited university that prides itself on its globality and accepting applicants from all countries, backgrounds, and cultures. It is a high priority of ours to maintain excellent intercultural communication, and to instill these skills into our students. No matter what degree program you choose, you can count on being able to use it in conversation across a range of cultures.

The Bottom Line

So, what is intercultural communication, and why should you improve your intercultural skills? Our world is only getting smaller, and the ability to competently communicate with other cultures is vital for success in all areas of life. Adapt your behavior, check your understanding, reflect on your experiences and follow our tips to foster excellent intercultural communication.

In this article

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Intercultural Communication

Learning objectives.

- Define intercultural communication.

- List and summarize the six dialectics of intercultural communication.

- Discuss how intercultural communication affects interpersonal relationships.

It is through intercultural communication that we come to create, understand, and transform culture and identity. Intercultural communication is communication between people with differing cultural identities. One reason we should study intercultural communication is to foster greater self-awareness (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). Our thought process regarding culture is often “other focused,” meaning that the culture of the other person or group is what stands out in our perception. However, the old adage “know thyself” is appropriate, as we become more aware of our own culture by better understanding other cultures and perspectives. Intercultural communication can allow us to step outside of our comfortable, usual frame of reference and see our culture through a different lens. Additionally, as we become more self-aware, we may also become more ethical communicators as we challenge our ethnocentrism , or our tendency to view our own culture as superior to other cultures.

As was noted earlier, difference matters, and studying intercultural communication can help us better negotiate our changing world. Changing economies and technologies intersect with culture in meaningful ways (Martin & Nakayama). As was noted earlier, technology has created for some a global village where vast distances are now much shorter due to new technology that make travel and communication more accessible and convenient (McLuhan, 1967). However, as the following “Getting Plugged In” box indicates, there is also a digital divide , which refers to the unequal access to technology and related skills that exists in much of the world. People in most fields will be more successful if they are prepared to work in a globalized world. Obviously, the global market sets up the need to have intercultural competence for employees who travel between locations of a multinational corporation. Perhaps less obvious may be the need for teachers to work with students who do not speak English as their first language and for police officers, lawyers, managers, and medical personnel to be able to work with people who have various cultural identities.

“Getting Plugged In”

The Digital Divide

Many people who are now college age struggle to imagine a time without cell phones and the Internet. As “digital natives” it is probably also surprising to realize the number of people who do not have access to certain technologies. The digital divide was a term that initially referred to gaps in access to computers. The term expanded to include access to the Internet since it exploded onto the technology scene and is now connected to virtually all computing (van Deursen & van Dijk, 2010). Approximately two billion people around the world now access the Internet regularly, and those who don’t face several disadvantages (Smith, 2011). Discussions of the digital divide are now turning more specifically to high-speed Internet access, and the discussion is moving beyond the physical access divide to include the skills divide, the economic opportunity divide, and the democratic divide. This divide doesn’t just exist in developing countries; it has become an increasing concern in the United States. This is relevant to cultural identities because there are already inequalities in terms of access to technology based on age, race, and class (Sylvester & McGlynn, 2010). Scholars argue that these continued gaps will only serve to exacerbate existing cultural and social inequalities. From an international perspective, the United States is falling behind other countries in terms of access to high-speed Internet. South Korea, Japan, Sweden, and Germany now all have faster average connection speeds than the United States (Smith, 2011). And Finland in 2010 became the first country in the world to declare that all its citizens have a legal right to broadband Internet access (ben-Aaron, 2010). People in rural areas in the United States are especially disconnected from broadband service, with about 11 million rural Americans unable to get the service at home. As so much of our daily lives go online, it puts those who aren’t connected at a disadvantage. From paying bills online, to interacting with government services, to applying for jobs, to taking online college classes, to researching and participating in political and social causes, the Internet connects to education, money, and politics.

- What do you think of Finland’s inclusion of broadband access as a legal right? Is this something that should be done in other countries? Why or why not?

- How does the digital divide affect the notion of the global village?

- How might limited access to technology negatively affect various nondominant groups?

Intercultural Communication: A Dialectical Approach

Intercultural communication is complicated, messy, and at times contradictory. Therefore it is not always easy to conceptualize or study. Taking a dialectical approach allows us to capture the dynamism of intercultural communication. A dialectic is a relationship between two opposing concepts that constantly push and pull one another (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). To put it another way, thinking dialectically helps us realize that our experiences often occur in between two different phenomena. This perspective is especially useful for interpersonal and intercultural communication, because when we think dialectically, we think relationally. This means we look at the relationship between aspects of intercultural communication rather than viewing them in isolation. Intercultural communication occurs as a dynamic in-betweenness that, while connected to the individuals in an encounter, goes beyond the individuals, creating something unique. Holding a dialectical perspective may be challenging for some Westerners, as it asks us to hold two contradictory ideas simultaneously, which goes against much of what we are taught in our formal education. Thinking dialectically helps us see the complexity in culture and identity because it doesn’t allow for dichotomies. Dichotomies are dualistic ways of thinking that highlight opposites, reducing the ability to see gradations that exist in between concepts. Dichotomies such as good/evil, wrong/right, objective/subjective, male/female, in-group/out-group, black/white, and so on form the basis of much of our thoughts on ethics, culture, and general philosophy, but this isn’t the only way of thinking (Marin & Nakayama, 1999). Many Eastern cultures acknowledge that the world isn’t dualistic. Rather, they accept as part of their reality that things that seem opposite are actually interdependent and complement each other. I argue that a dialectical approach is useful in studying intercultural communication because it gets us out of our comfortable and familiar ways of thinking. Since so much of understanding culture and identity is understanding ourselves, having an unfamiliar lens through which to view culture can offer us insights that our familiar lenses will not. Specifically, we can better understand intercultural communication by examining six dialectics (see Figure 8.1 “Dialectics of Intercultural Communication” ) (Martin & Nakayama, 1999).

Figure 8.1 Dialectics of Intercultural Communication

Source: Adapted from Judith N. Martin and Thomas K. Nakayama, “Thinking Dialectically about Culture and Communication,” Communication Theory 9, no. 1 (1999): 1–25.

The cultural-individual dialectic captures the interplay between patterned behaviors learned from a cultural group and individual behaviors that may be variations on or counter to those of the larger culture. This dialectic is useful because it helps us account for exceptions to cultural norms. For example, earlier we learned that the United States is said to be a low-context culture, which means that we value verbal communication as our primary, meaning-rich form of communication. Conversely, Japan is said to be a high-context culture, which means they often look for nonverbal clues like tone, silence, or what is not said for meaning. However, you can find people in the United States who intentionally put much meaning into how they say things, perhaps because they are not as comfortable speaking directly what’s on their mind. We often do this in situations where we may hurt someone’s feelings or damage a relationship. Does that mean we come from a high-context culture? Does the Japanese man who speaks more than is socially acceptable come from a low-context culture? The answer to both questions is no. Neither the behaviors of a small percentage of individuals nor occasional situational choices constitute a cultural pattern.

The personal-contextual dialectic highlights the connection between our personal patterns of and preferences for communicating and how various contexts influence the personal. In some cases, our communication patterns and preferences will stay the same across many contexts. In other cases, a context shift may lead us to alter our communication and adapt. For example, an American businesswoman may prefer to communicate with her employees in an informal and laid-back manner. When she is promoted to manage a department in her company’s office in Malaysia, she may again prefer to communicate with her new Malaysian employees the same way she did with those in the United States. In the United States, we know that there are some accepted norms that communication in work contexts is more formal than in personal contexts. However, we also know that individual managers often adapt these expectations to suit their own personal tastes. This type of managerial discretion would likely not go over as well in Malaysia where there is a greater emphasis put on power distance (Hofstede, 1991). So while the American manager may not know to adapt to the new context unless she has a high degree of intercultural communication competence, Malaysian managers would realize that this is an instance where the context likely influences communication more than personal preferences.

The differences-similarities dialectic allows us to examine how we are simultaneously similar to and different from others. As was noted earlier, it’s easy to fall into a view of intercultural communication as “other oriented” and set up dichotomies between “us” and “them.” When we overfocus on differences, we can end up polarizing groups that actually have things in common. When we overfocus on similarities, we essentialize , or reduce/overlook important variations within a group. This tendency is evident in most of the popular, and some of the academic, conversations regarding “gender differences.” The book Men Are from Mars and Women Are from Venus makes it seem like men and women aren’t even species that hail from the same planet. The media is quick to include a blurb from a research study indicating again how men and women are “wired” to communicate differently. However, the overwhelming majority of current research on gender and communication finds that while there are differences between how men and women communicate, there are far more similarities (Allen, 2011). Even the language we use to describe the genders sets up dichotomies. That’s why I suggest that my students use the term other gender instead of the commonly used opposite sex . I have a mom, a sister, and plenty of female friends, and I don’t feel like any of them are the opposite of me. Perhaps a better title for a book would be Women and Men Are Both from Earth .

The static-dynamic dialectic suggests that culture and communication change over time yet often appear to be and are experienced as stable. Although it is true that our cultural beliefs and practices are rooted in the past, we have already discussed how cultural categories that most of us assume to be stable, like race and gender, have changed dramatically in just the past fifty years. Some cultural values remain relatively consistent over time, which allows us to make some generalizations about a culture. For example, cultures have different orientations to time. The Chinese have a longer-term orientation to time than do Europeans (Lustig & Koester, 2006). This is evidenced in something that dates back as far as astrology. The Chinese zodiac is done annually (The Year of the Monkey, etc.), while European astrology was organized by month (Taurus, etc.). While this cultural orientation to time has been around for generations, as China becomes more Westernized in terms of technology, business, and commerce, it could also adopt some views on time that are more short term.

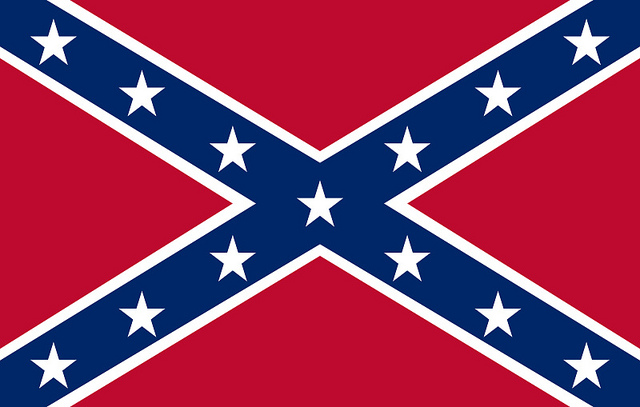

The history/past-present/future dialectic reminds us to understand that while current cultural conditions are important and that our actions now will inevitably affect our future, those conditions are not without a history. We always view history through the lens of the present. Perhaps no example is more entrenched in our past and avoided in our present as the history of slavery in the United States. Where I grew up in the Southern United States, race was something that came up frequently. The high school I attended was 30 percent minorities (mostly African American) and also had a noticeable number of white teens (mostly male) who proudly displayed Confederate flags on their clothing or vehicles.

There has been controversy over whether the Confederate flag is a symbol of hatred or a historical symbol that acknowledges the time of the Civil War.

Jim Surkamp – Confederate Rebel Flag – CC BY-NC 2.0.

I remember an instance in a history class where we were discussing slavery and the subject of repatriation, or compensation for descendants of slaves, came up. A white male student in the class proclaimed, “I’ve never owned slaves. Why should I have to care about this now?” While his statement about not owning slaves is valid, it doesn’t acknowledge that effects of slavery still linger today and that the repercussions of such a long and unjust period of our history don’t disappear over the course of a few generations.

The privileges-disadvantages dialectic captures the complex interrelation of unearned, systemic advantages and disadvantages that operate among our various identities. As was discussed earlier, our society consists of dominant and nondominant groups. Our cultures and identities have certain privileges and/or disadvantages. To understand this dialectic, we must view culture and identity through a lens of intersectionality , which asks us to acknowledge that we each have multiple cultures and identities that intersect with each other. Because our identities are complex, no one is completely privileged and no one is completely disadvantaged. For example, while we may think of a white, heterosexual male as being very privileged, he may also have a disability that leaves him without the able-bodied privilege that a Latina woman has. This is often a difficult dialectic for my students to understand, because they are quick to point out exceptions that they think challenge this notion. For example, many people like to point out Oprah Winfrey as a powerful African American woman. While she is definitely now quite privileged despite her disadvantaged identities, her trajectory isn’t the norm. When we view privilege and disadvantage at the cultural level, we cannot let individual exceptions distract from the systemic and institutionalized ways in which some people in our society are disadvantaged while others are privileged.

As these dialectics reiterate, culture and communication are complex systems that intersect with and diverge from many contexts. A better understanding of all these dialectics helps us be more critical thinkers and competent communicators in a changing world.

“Getting Critical”

Immigration, Laws, and Religion

France, like the United States, has a constitutional separation between church and state. As many countries in Europe, including France, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden, have experienced influxes of immigrants, many of them Muslim, there have been growing tensions among immigration, laws, and religion. In 2011, France passed a law banning the wearing of a niqab (pronounced knee-cobb ), which is an Islamic facial covering worn by some women that only exposes the eyes. This law was aimed at “assimilating its Muslim population” of more than five million people and “defending French values and women’s rights” (De La Baume & Goodman, 2011). Women found wearing the veil can now be cited and fined $150 euros. Although the law went into effect in April of 2011, the first fines were issued in late September of 2011. Hind Ahmas, a woman who was fined, says she welcomes the punishment because she wants to challenge the law in the European Court of Human Rights. She also stated that she respects French laws but cannot abide by this one. Her choice to wear the veil has been met with more than a fine. She recounts how she has been denied access to banks and other public buildings and was verbally harassed by a woman on the street and then punched in the face by the woman’s husband. Another Muslim woman named Kenza Drider, who can be seen in Video Clip 8.2, announced that she will run for the presidency of France in order to challenge the law. The bill that contained the law was broadly supported by politicians and the public in France, and similar laws are already in place in Belgium and are being proposed in Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, and Switzerland (Fraser, 2011).

- Some people who support the law argue that part of integrating into Western society is showing your face. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- Part of the argument for the law is to aid in the assimilation of Muslim immigrants into French society. What are some positives and negatives of this type of assimilation?

- Identify which of the previously discussed dialectics can be seen in this case. How do these dialectics capture the tensions involved?

Video Clip 8.2

Veiled Woman Eyes French Presidency

(click to see video)

Intercultural Communication and Relationships

Intercultural relationships are formed between people with different cultural identities and include friends, romantic partners, family, and coworkers. Intercultural relationships have benefits and drawbacks. Some of the benefits include increasing cultural knowledge, challenging previously held stereotypes, and learning new skills (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). For example, I learned about the Vietnamese New Year celebration Tet from a friend I made in graduate school. This same friend also taught me how to make some delicious Vietnamese foods that I continue to cook today. I likely would not have gained this cultural knowledge or skill without the benefits of my intercultural friendship. Intercultural relationships also present challenges, however.

The dialectics discussed earlier affect our intercultural relationships. The similarities-differences dialectic in particular may present challenges to relationship formation (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). While differences between people’s cultural identities may be obvious, it takes some effort to uncover commonalities that can form the basis of a relationship. Perceived differences in general also create anxiety and uncertainty that is not as present in intracultural relationships. Once some similarities are found, the tension within the dialectic begins to balance out and uncertainty and anxiety lessen. Negative stereotypes may also hinder progress toward relational development, especially if the individuals are not open to adjusting their preexisting beliefs. Intercultural relationships may also take more work to nurture and maintain. The benefit of increased cultural awareness is often achieved, because the relational partners explain their cultures to each other. This type of explaining requires time, effort, and patience and may be an extra burden that some are not willing to carry. Last, engaging in intercultural relationships can lead to questioning or even backlash from one’s own group. I experienced this type of backlash from my white classmates in middle school who teased me for hanging out with the African American kids on my bus. While these challenges range from mild inconveniences to more serious repercussions, they are important to be aware of. As noted earlier, intercultural relationships can take many forms. The focus of this section is on friendships and romantic relationships, but much of the following discussion can be extended to other relationship types.

Intercultural Friendships

Even within the United States, views of friendship vary based on cultural identities. Research on friendship has shown that Latinos/as value relational support and positive feedback, Asian Americans emphasize exchanges of ideas like offering feedback or asking for guidance, African Americans value respect and mutual acceptance, and European Americans value recognition of each other as individuals (Coller, 1996). Despite the differences in emphasis, research also shows that the overall definition of a close friend is similar across cultures. A close friend is thought of as someone who is helpful and nonjudgmental, who you enjoy spending time with but can also be independent, and who shares similar interests and personality traits (Lee, 2006).

Intercultural friendship formation may face challenges that other friendships do not. Prior intercultural experience and overcoming language barriers increase the likelihood of intercultural friendship formation (Sias et al., 2008). In some cases, previous intercultural experience, like studying abroad in college or living in a diverse place, may motivate someone to pursue intercultural friendships once they are no longer in that context. When friendships cross nationality, it may be necessary to invest more time in common understanding, due to language barriers. With sufficient motivation and language skills, communication exchanges through self-disclosure can then further relational formation. Research has shown that individuals from different countries in intercultural friendships differ in terms of the topics and depth of self-disclosure, but that as the friendship progresses, self-disclosure increases in depth and breadth (Chen & Nakazawa, 2009). Further, as people overcome initial challenges to initiating an intercultural friendship and move toward mutual self-disclosure, the relationship becomes more intimate, which helps friends work through and move beyond their cultural differences to focus on maintaining their relationship. In this sense, intercultural friendships can be just as strong and enduring as other friendships (Lee, 2006).

The potential for broadening one’s perspective and learning more about cultural identities is not always balanced, however. In some instances, members of a dominant culture may be more interested in sharing their culture with their intercultural friend than they are in learning about their friend’s culture, which illustrates how context and power influence friendships (Lee, 2006). A research study found a similar power dynamic, as European Americans in intercultural friendships stated they were open to exploring everyone’s culture but also communicated that culture wasn’t a big part of their intercultural friendships, as they just saw their friends as people. As the researcher states, “These types of responses may demonstrate that it is easiest for the group with the most socioeconomic and socio-cultural power to ignore the rules, assume they have the power as individuals to change the rules, or assume that no rules exist, since others are adapting to them rather than vice versa” (Collier, 1996). Again, intercultural friendships illustrate the complexity of culture and the importance of remaining mindful of your communication and the contexts in which it occurs.

Culture and Romantic Relationships

Romantic relationships are influenced by society and culture, and still today some people face discrimination based on who they love. Specifically, sexual orientation and race affect societal views of romantic relationships. Although the United States, as a whole, is becoming more accepting of gay and lesbian relationships, there is still a climate of prejudice and discrimination that individuals in same-gender romantic relationships must face. Despite some physical and virtual meeting places for gay and lesbian people, there are challenges for meeting and starting romantic relationships that are not experienced for most heterosexual people (Peplau & Spalding, 2000).

As we’ve already discussed, romantic relationships are likely to begin due to merely being exposed to another person at work, through a friend, and so on. But some gay and lesbian people may feel pressured into or just feel more comfortable not disclosing or displaying their sexual orientation at work or perhaps even to some family and friends, which closes off important social networks through which most romantic relationships begin. This pressure to refrain from disclosing one’s gay or lesbian sexual orientation in the workplace is not unfounded, as it is still legal in twenty-nine states (as of November 2012) to fire someone for being gay or lesbian (Human Rights Campaign, 2012). There are also some challenges faced by gay and lesbian partners regarding relationship termination. Gay and lesbian couples do not have the same legal and societal resources to manage their relationships as heterosexual couples; for example, gay and lesbian relationships are not legally recognized in most states, it is more difficult for a gay or lesbian couple to jointly own property or share custody of children than heterosexual couples, and there is little public funding for relationship counseling or couples therapy for gay and lesbian couples.

While this lack of barriers may make it easier for gay and lesbian partners to break out of an unhappy or unhealthy relationship, it could also lead couples to termination who may have been helped by the sociolegal support systems available to heterosexuals (Peplau & Spalding, 2000).

Despite these challenges, relationships between gay and lesbian people are similar in other ways to those between heterosexuals. Gay, lesbian, and heterosexual people seek similar qualities in a potential mate, and once relationships are established, all these groups experience similar degrees of relational satisfaction (Peplau & Spalding, 2000). Despite the myth that one person plays the man and one plays the woman in a relationship, gay and lesbian partners do not have set preferences in terms of gender role. In fact, research shows that while women in heterosexual relationships tend to do more of the housework, gay and lesbian couples were more likely to divide tasks so that each person has an equal share of responsibility (Peplau & Spalding, 2000). A gay or lesbian couple doesn’t necessarily constitute an intercultural relationship, but as we have already discussed, sexuality is an important part of an individual’s identity and connects to larger social and cultural systems. Keeping in mind that identity and culture are complex, we can see that gay and lesbian relationships can also be intercultural if the partners are of different racial or ethnic backgrounds.

While interracial relationships have occurred throughout history, there have been more historical taboos in the United States regarding relationships between African Americans and white people than other racial groups. Antimiscegenation laws were common in states and made it illegal for people of different racial/ethnic groups to marry. It wasn’t until 1967 that the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Loving versus Virginia , declaring these laws to be unconstitutional (Pratt, 1995). It wasn’t until 1998 and 2000, however, that South Carolina and Alabama removed such language from their state constitutions (Lovingday.org, 2011). The organization and website lovingday.org commemorates the landmark case and works to end racial prejudice through education.

Even after these changes, there were more Asian-white and Latino/a-white relationships than there were African American–white relationships (Gaines Jr. & Brennan, 2011). Having already discussed the importance of similarity in attraction to mates, it’s important to note that partners in an interracial relationship, although culturally different, tend to be similar in occupation and income. This can likely be explained by the situational influences on our relationship formation we discussed earlier—namely, that work tends to be a starting ground for many of our relationships, and we usually work with people who have similar backgrounds to us.

There has been much research on interracial couples that counters the popular notion that partners may be less satisfied in their relationships due to cultural differences. In fact, relational satisfaction isn’t significantly different for interracial partners, although the challenges they may face in finding acceptance from other people could lead to stressors that are not as strong for intracultural partners (Gaines Jr. & Brennan, 2011). Although partners in interracial relationships certainly face challenges, there are positives. For example, some mention that they’ve experienced personal growth by learning about their partner’s cultural background, which helps them gain alternative perspectives. Specifically, white people in interracial relationships have cited an awareness of and empathy for racism that still exists, which they may not have been aware of before (Gaines Jr. & Liu, 2000).

The Supreme Court ruled in the 1967 Loving v. Virginia case that states could not enforce laws banning interracial marriages.

Bahai.us – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Key Takeaways

- Studying intercultural communication, communication between people with differing cultural identities, can help us gain more self-awareness and be better able to communicate in a world with changing demographics and technologies.

- A dialectical approach to studying intercultural communication is useful because it allows us to think about culture and identity in complex ways, avoiding dichotomies and acknowledging the tensions that must be negotiated.

- Intercultural relationships face some challenges in negotiating the dialectic between similarities and differences but can also produce rewards in terms of fostering self- and other awareness.

- Why is the phrase “Know thyself” relevant to the study of intercultural communication?

- Apply at least one of the six dialectics to a recent intercultural interaction that you had. How does this dialectic help you understand or analyze the situation?

- Do some research on your state’s laws by answering the following questions: Did your state have antimiscegenation laws? If so, when were they repealed? Does your state legally recognize gay and lesbian relationships? If so, how?

Allen, B. J., Difference Matters: Communicating Social Identity , 2nd ed. (Long Grove, IL: Waveland, 2011), 55.

ben-Aaron, D., “Bringing Broadband to Finland’s Bookdocks,” Bloomberg Businessweek , July 19, 2010, 42.

Chen, Y. and Masato Nakazawa, “Influences of Culture on Self-Disclosure as Relationally Situated in Intercultural and Interracial Friendships from a Social Penetration Perspective,” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 38, no. 2 (2009): 94. doi:10.1080/17475750903395408.

Coller, M. J., “Communication Competence Problematics in Ethnic Friendships,” Communication Monographs 63, no. 4 (1996): 324–25.

De La Baume, M. and J. David Goodman, “First Fines over Wearing Veils in France,” The New York Times ( The Lede: Blogging the News ), September 22, 2011, accessed October 10, 2011, http://thelede.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/22/first-fines-over -wearing-full-veils-in-france .

Fraser, C., “The Women Defying France’s Fall-Face Veil Ban,” BBC News , September 22, 2011, accessed October 10, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-15023308 .

Gaines Jr. S. O., and Kelly A. Brennan, “Establishing and Maintaining Satisfaction in Multicultural Relationships,” in Close Romantic Relationships: Maintenance and Enhancement , eds. John Harvey and Amy Wenzel (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2011), 239.

Stanley O. Gaines Jr., S. O., and James H. Liu, “Multicultural/Multiracial Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook , eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 105.

Hofstede, G., Cultures and Organizations: Softwares of the Mind (London: McGraw-Hill, 1991), 26.

Human Rights Campaign, “Pass ENDA NOW”, accessed November 5, 2012, http://www.hrc.org/campaigns/employment-non-discrimination-act .

Lee, P., “Bridging Cultures: Understanding the Construction of Relational Identity in Intercultural Friendships,” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 35, no. 1 (2006): 11. doi:10.1080/17475740600739156.

Loving Day, “The Last Laws to Go,” Lovingday.org , accessed October 11, 2011, http://lovingday.org/last-laws-to-go .

Lustig, M. W., and Jolene Koester, Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures , 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2006), 128–29.

Martin, J. N., and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts , 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 4.

Martin, J. N., and Thomas K. Nakayama, “Thinking Dialectically about Culture and Communication,” Communication Theory 9, no. 1 (1999): 14.

McLuhan, M., The Medium Is the Message (New York: Bantam Books, 1967).

Peplau, L. A. and Leah R. Spalding, “The Close Relationships of Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook , eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 113.

Pratt, R. A., “Crossing the Color Line: A Historical Assessment and Personal Narrative of Loving v. Virginia ,” Howard Law Journal 41, no. 2 (1995): 229–36.

Sias, P. M., Jolanta A. Drzewiecka, Mary Meares, Rhiannon Bent, Yoko Konomi, Maria Ortega, and Colene White, “Intercultural Friendship Development,” Communication Reports 21, no. 1 (2008): 9. doi:10.1080/08934210701643750.

Smith, P., “The Digital Divide,” New York Times Upfront , May 9, 2011, 6.

Sylvester, D. E., and Adam J. McGlynn, “The Digital Divide, Political Participation, and Place,” Social Science Computer Review 28, no. 1 (2010): 64–65. doi:10.1177/0894439309335148.

van Deursen, A. and Jan van Dijk, “Internet Skills and the Digital Divide,” New Media and Society 13, no. 6 (2010): 893. doi:10.1177/1461444810386774.

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Update 10/09/2024: Due to technical disruption, we are experiencing some delays to publication. We are working to restore services and apologise for the inconvenience. For further updates please visit our website

The Cambridge Introduction to Intercultural Communication

- Library eCollections

Description

Uniquely interdisciplinary and accessible, The Cambridge Introduction to Intercultural Communication is the ideal text for undergraduate introductory courses in Intercultural Communication, International Communication and Cross-cultural Communication. Suitable for students and practitioners alike, it encompasses the breadth of intercultural communication as an academic field and a day-to-day experience in work and private life, including international business, public services, schools and universities. This textbook touches on a range of themes in intercultural communication, such as evolutionary and positive psychology, key concepts from…

- Add to bookmarks

- Download flyer

- Add bookmark

- Cambridge Spiral eReader

Key features

- Truly interdisciplinary and easy-to-read, it puts the concept of Critical Intercultural Communication at the centre of the field

- Demonstrates how theories relate to real-life applications through a wide variety of application tasks, connecting theory with practice in an engaging way

- Explores the link between intercultural communication and global business, health, psychology and military services, making concepts accessible to students without humanities backgrounds

- Draws on recent high-profile research from the Cambridge Handbook of Intercultural Communication (ed. by Rings & Rasinger 2020), which won the Choice Outstanding Academic Title award in 2021

About the book

- DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108904025

- Subjects Anthropology, Applied Linguistics, Language and Linguistics, Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Publication date: 08 December 2022

- ISBN: 9781108842716

- Dimensions (mm): 254 x 178 mm

- Weight: 0.66kg

- Page extent: 262 pages

- Availability: In stock

- ISBN: 9781108822541

- Weight: 0.51kg

- Publication date: 08 February 2023

- ISBN: 9781108904025

Access options

Review the options below to login to check your access.

Personal login

Log in with your Cambridge Higher Education account to check access.

Purchase options

There are no purchase options available for this title.

Have an access code?

To redeem an access code, please log in with your personal login.

If you believe you should have access to this content, please contact your institutional librarian or consult our FAQ page for further information about accessing our content.

Guido Rings is Emeritus Professor of Postcolonial Studies, co-director of the Anglia Ruskin Research Centre for Intercultural and Multilingual Studies (ARRCIMS), and co-founder of iMex and German as a Foreign Language, the first internet journals in Europe for their respective fields. Professor Rings has widely published within different areas of critical intercultural and postcolonial studies. This includes, as editor, the acclaimed Cambridge Handbook of Intercultural Communication (with S. M. Rasinger, Cambridge University Press, 2020) and, as author, the world-leading scoring The Other in Contemporary Migrant Cinema (Routledge, 2016) and the celebrated La Conquista desbaratada (The Conquest upside down, Iberoamericana, 2010), next to more than fifty distinguished refereed articles.

Sebastian M. Rasinger is Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics at Anglia Ruskin University. His research focuses on language and identity, with a particular focus on multilingual and migration contexts. He has extensive experience in teaching courses in these areas at all levels. His textbook Quantitative Research in Linguistics: An Introduction, published in two editions (Bloomsbury 2008 and 2013), has sold several thousand copies and has been published in its Spanish translation by Ediciones Akal. Sebastian has a strong interest in equality and diversity in higher education, and is currently the vice chair of the QAA Advisory Group for linguistics, overseeing the review of the linguistics subject benchmarks in UK HE.

Curated content

With Case Studies in Journalism, PR, and Community Communication

Online publication date: 18 February 2023

Hardback publication date:

Paperback publication date:

An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology

Online publication date: 25 August 2023

Online publication date: 18 February 2020

Related content

AI generated results by Discovery for publishers [opens in a new window]

Online publication date: 10 March 2022

- Dan Landis ,

- Dharm P. S. Bhawuk

Online publication date: 18 September 2020

- Heather Bowe ,

- Kylie Martin ,

- Howard Manns

Online publication date: 12 August 2019

Paperback publication date: 23 October 2014

Intercultural Communicative Competence

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 08 August 2024

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Yoko Munezane 2

Cross-cultural competence ; Cultural intelligence ; Global competence ; Intercultural communication competence ; Intercultural competence ; Intercultural effectiveness ; Intercultural sensitivity ; Transcultural competence

Intercultural (communicative) competence (ICC) generally refers to the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately with people from diverse cultural backgrounds. It is the ability to navigate differences in a complex society, characterized by increasing diversity of cultures, peoples, philosophies, and lifestyles (UNESCO, 2013 ). Various definitions of ICC have been proposed by scholars over the past decades. For example, Byram ( 1997 : 2021) defines intercultural communicative competence as “a person’s ability to relate to and communicate with people who speak a different language and live in a different cultural context” (p. 1). Chen and Starosta ( 1998 ) view ICC as “the ability to effectively and appropriately execute communication behaviors...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Arasaratnam, L. (2006). Further testing of a new model of intercultural communication competence. Communication Research Reports, 23 , 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090600668923

Article Google Scholar

Arasaratnam, L., & Banerjee, S. (2011). Sensation seeking and intercultural communication competence: A model test. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 , 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.07.003

Bachman, L. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing . Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Banegas, D. L. (2021). Epilogue. In M. D. López-Jiménez & J. Sánchez-Torres (Eds.), Intercultural competence past, present and future: Respecting the past, problems in the present and forging the future (pp. 275–279). Springer.

Bennett, J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10 , 179–196.

Bennett, J. (2009). Cultivating intercultural competence: A process perspective. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 121–140). Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bradford, L., Allen, M., & Beisser, K. R. (2000). An evaluation and meta-analysis of intercultural communication competence research. World Communication, 29 (1), 28–51.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence . Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. (2003). Intercultural competence . Council of Europe Publishing. http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/autobiography/source/aie_en/aie_context_concepts_and_theories_en.pdf

Byram, M. (2008). From foreign language education to education for intercultural citizenship: Essays and reflections . Multilingual Matters.

Book Google Scholar

Byram, M. (2021). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence: Revisited . Multilingual Matters.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1 , 1–47.

Chen, G.-M., & An, R. (2009). A Chinese model of intercultural leadership competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 196–207). Sage.

Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (1998). A review of the concept of intercultural sensitivity. Human Communication, 1 , 1–16.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment . Cambridge University Press.

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of the emotions in man and animals. John Murray. https://doi.org/10.1037/10001-000

Deardorff. (2004). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States . Unpublished dissertation, North Carolina State University, Raleigh.

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10 (3), 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287002

Deardorff, D. K. (2009). Synthesizing conceptualizations of intercultural competence: A summary and emerging themes. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 264–269). Sage.

Dervin, F. (2012). Cultural identity, representation and othering. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (1st ed., pp. 181–194). Routledge.

Dervin, F., & Yuan, M. (2022). Revitalizing interculturality in education: Chinese Minzu as a companion . Routledge.

Dooly, M., & Ron Darvin, R. (2022). Intercultural communicative competence in the digital age: Critical digital literacy and inquiry-based pedagogy. Language & Intercultural Communication, 22 (3), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2022.2063304

Fantini, A. E. (1995). Language, culture, and worldview: Exploring the nexus. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 19 , 143–153.

Fantini, A. E. (2009). Assessing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 456–476). Sage.

Fantini, A. E. (2019). Intercultural communicative competence in educational exchange: A multinational perspective . Routledge.

Fantini, A. E. (2020). Reconceptualizing intercultural communicative competence: A multinational perspective. Research in Comparative and International Education, 15 (1), 52–61.

Fantini, A., & Tirmizi, A. (2006). Exploring and assessing intercultural competence . World Learning Publications.

Gudykunst, W. D. (1995). Anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory: Current status. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8–58). Sage Publications, Inc.

Gustavsoon, B. (1998). Dannelse i vor tid: om dannelsens vilkår og muligheter in det modern samfund [Bildung in our time: The conditions and possibilities for bildung in modern society]. Klim.

Hammar, M. R., Gukykunst, B. G., & Wiseman, R. L. (1978). Dimensions of intercultural effectiveness: An exploratory study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2 (4), 382–393.

Headland, T. N., Pike, K. L., & Harris, M. (1990). Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate . Sage.

Herder J. G. (2002). Philosophical writings (Translated and edited by Forster, M. N.). Cambridge University Press.

Hoff, H. E. (2014). A critical discussion of Byram’s model of intercultural communicative competence in the light of bildung theories. Intercultural Education, 25 (6), 508–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2014.992112

Holliday, A. (2020). Culture, communication, context, and power. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (2nd ed., pp. 39–54). Routledge.

Howard-Hamilton, M. F., Richardson, B. J., & Shuford, B. C. (1998). Promoting multicultural education: A holistic approach. The College Student Affairs Journal, 18 , 5–17.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. Pride, & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics (pp. 269–285). Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Jenks, C., Bhatia, A., & Lou, J. (2013). The discourse of culture and identity in national and transnational contexts. Language & Intercultural Communication, 13 , 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2013.770862

Kim, Y. Y. (1988). Communication and cross-cultural adaptation: An integrative theory. Multilingual matters . Clevedon.

Kim, Y. Y. (2009). The identity factor in intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 53–65). Sage.

King, P. M., & Baxter Magolda, M. B. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity. Journal of College Student Development, 46 , 571. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0060

Kramsch, C. J. (2001). Intercultural communication. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages (pp. 201–206). Cambridge University Press.

Landis, D., & Bhawuk, D. (Eds.). (2020). The Cambridge handbook of intercultural training (4th ed., Cambridge handbooks in psychology ). Cambridge Univesity Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108854184

Leeds-Hurwitz, W. (1990). Notes in the history of intercultural communication: The foreign service institute and the mandate for intercultural training. The Quarterly Journal of Speech, 76 (3), 262–281.

MacIntyre, P. D., Dörnyei, Z., Clément, R., & Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. The Modern Language Journal, 82 , 545–562.

Martin, J. (2015). Revisiting intercultural communication competence: Where to go from here. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 48 , 6–8.

Martin, J. N., Nakayama, T. K., & Carbaugh, D. (2020). The history and development of the study of intercultural communication and applied linguistics. In The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (pp. 17–36). Routledge.

Medina-Lopez-Portillo, A., & Sinnigen, J. H. (2009). Interculturality versus intercultural competencies in Latin America. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 249–263). Sage.

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1 (1), 58–63.

Munezane, Y. (2021). A new model of intercultural communicative competence: Bridging language classrooms and intercultural communicative contexts. Studies in Higher Education, 46 (8), 1664–1681. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1698537

Navas, M., García, M. C., Sánchez, J., Rojas, A. J., Pumares, P., & Fernández, J. S. (2005). Relative acculturation extended model (RAEM): New contributions with regard to the study of acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29 (1), 21–37.

Nwosu, P. O. (2009). Understanding Africans’ conceptualizations of intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 158–178). Sage.

Osler, A., & Starkey, H. (2010). Teachers and human rights education . Trentham Books.

Porto, M., Houghton, S. A., & Byram, M. (2018). Intercultural citizenship in the (foreign) language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 22 (5), 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817718580

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2–52). Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S., & Kurogi, A. (1998). Facework competence in intercultural conflict: An updated face-negotiation theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 22 (2), 187–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(98)00004-2

UNESCO. (2013). Intercultural competencies: Conceptual and operational framework. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000219768

Zaharna, R. S. (2009). An associative approach to intercultural communication competence in the Arab world. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 179–195). Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Rikkyo University, Tokyo, Japan

Yoko Munezane

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yoko Munezane .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Munezane, Y. (2024). Intercultural Communicative Competence. In: Encyclopedia of Diversity. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95454-3_593-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95454-3_593-1

Received : 31 December 2022

Accepted : 11 October 2023

Published : 08 August 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-95454-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-95454-3

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Religion and Philosophy Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Intercultural Communication

After completing this section, students should be able to:

- describe what it means to be a provisional communicator.

- define culture and co-culture.

- explain how culture may impact communication choices.

- apply Hofstede’s dimensions of culture to oneself and a group.

- show how Hall’s cultural variations apply to oneself and a group.

- identify barriers to intercultural competence.

Humans are naturally egocentric . Since we can exist only within our own heads, it is perfectly natural for us to assume everyone else thinks, perceives, and communicates as we do. The only world we can experience is the world as we see it, and it can be very challenging to understand that varied perceptions, values, and beliefs exist which are equally valid.

Being a provisional communicator can be challenging. Provisionalism is the ability to accept the diversity of perceptions and beliefs, and to operate in a manner sensitive to that diversity . Being provisional does not mean we abandon our own beliefs and values, nor does it mean we have to accept all beliefs and values as correct. Instead, provisionalism leads us to seek to understand variations in human behaviors, and to understand the field of experience See Module I, Section 2 for a discussion of field of experience. out of which the other person operates. This adds an extra step to the interpretation process:

- We interpret the world within our own life experiences, but then

- We stop and consider, “How was the message intended?” or “What other factors may be motivating this behavior?”

In addition to cultural differences, we also experience variations in communication behaviors between men and women. For example, Keith’s wife and her sister can talk for hours about all sorts of relational issues with co-workers, with family members, and with friends while he finds such extensive conversations exhausting. Since female communication is far more focused on relationship development and maintenance, such conversations are consistent with the feminine communication style. The masculine style is far more focused on action and the bare details of events, who did what to whom, and not as focused on the nuances of relational dynamics. As someone who uses the masculine style, once Keith gets the basic details, he thinks he is informed and does not feel a need to dissect the smaller details of the event. Note that the masculine and feminine communication styles are not based on biology; men can use a feminine style and women can use a masculine style. In Module III, Section 2 See Module III, Section 2 , you will learn more about these styles and how we move between them depending on the situation.

Culture and gender impact communication. As with all human behavior, when we address such variations, we always speak of tendencies, not absolutes: men tend to communicate one way, and women tend to communicate somewhat differently. Imagine if a visitor from another culture was to ask you, “What are Americans like?” Chances are you could identify a few characteristics but would also qualify your statements with, “But not everyone….”

Culture and Communication

Within each of the social groups, communication is influenced. Consider:

- The use of specific gestures, colors, and styles of dress in inner city gangs;

- The classic Southern Accent;

- The use of regional sayings, such as “you betcha,” or “whatever” in rural Minnesota;

- The more quiet nature of Native Americans who may prefer to listen and observe.

These cultural groups and social identities operate within the larger culture while maintaining the traits that make these smaller groups unique. These variations in lifestyle, communication behaviors, values, beliefs, art, food, and such provide a rich quilt of human experience, and for the provisional communicator, one who can accept and appreciate these difference, it can be an invigorating experience to move among them.

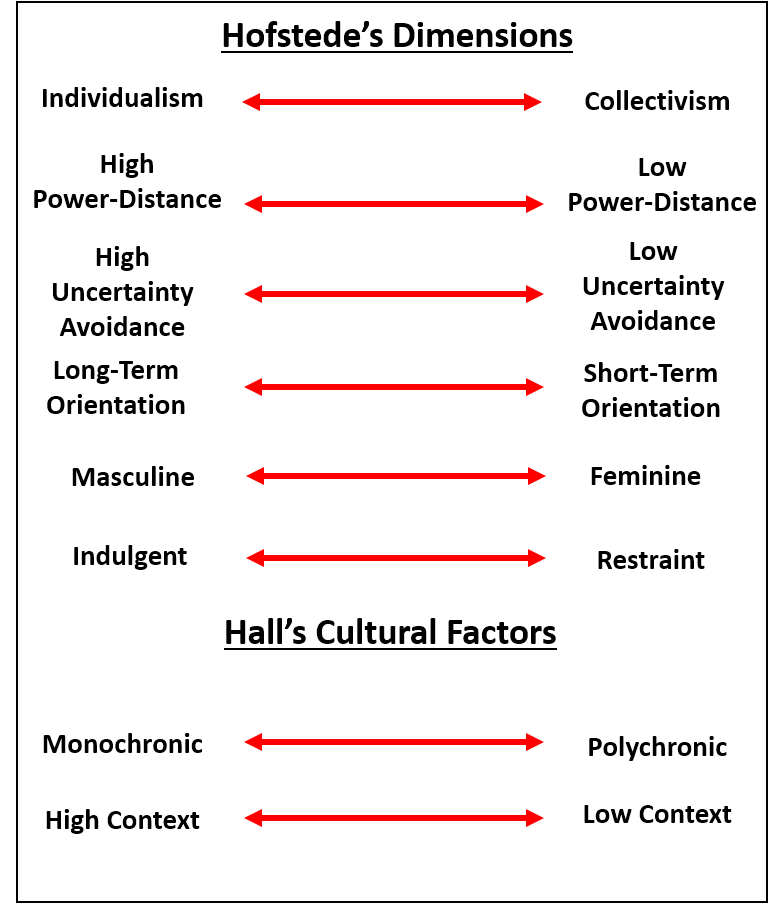

Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture

- Individualism and Collectivism

The left side of this dimension, called Individualism , can be defined as a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to take care of themselves and their immediate families only . Its opposite, Collectivism , represents a preference for a tightly-knit framework in society in which individuals can expect their relatives or members of a particular in-group to look after them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty . A society’s position on this dimension is reflected in whether people’s self-image is defined in terms of “I” or “we” (Hofstede, 2012a).

In a highly individualistic culture, members are able to make choices based on personal preference with little regard for others, except for close family or significant relationships. They can pursue their own wants and needs free from concerns about meeting social expectations. The United States is a highly individualistic culture. While we value the role of certain aspects of collectivism such as government, social organizations, or other forms of collective action, at our core we strongly believe it is up to each person to find and follow their path in life.

In a highly collectivistic culture, just the opposite is true. It is the role of individuals to fulfill their place in the overall social order. Personal wants and needs are secondary to the needs of the society at large. There is immense pressure to adhere to social norms, and those who fail to conform risk social isolation, disconnection from family, and perhaps some form of banishment. China is typically considered a highly collectivistic culture. In China, multigenerational homes are common, and tradition calls for the oldest son to care for his parents as they age.

The power distance dimension of culture expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept and expect power to be distributed unequally. The fundamental issue is how a society handles inequalities among people. People in societies exhibiting a large degree of power distance accept a hierarchical order in which everybody has a place and which needs no further justification . In societies with low power distance, people strive to equalize the distribution of power and demand justification for inequalities of power (Hofstede, 2012a).

In high power-distance cultures, the members accept some having more power and some having less power, and that this power distribution is natural and normal. Those with power are assumed to deserve it, and likewise those without power are assumed to be in their proper place. In such a culture, there will be a rigid adherence to the use of titles, “Sir,” “Ma’am,” “Officer,” “Reverend,” and so on. The directives of those with higher power are to be obeyed, with little question.

In low power-distance cultures, the distribution of power is considered far more arbitrary and viewed as a result of luck, money, heritage, or other external variables. For a person to be seen as having power, something must justify their power. A wealthy person is typically seen as more powerful in western cultures. Elected officials, like United States Senators, will be seen as powerful since they had to win their office by receiving majority support. In these cultures, individuals who attempt to assert power are often faced with those who stand up to them, question them, ignore them, or otherwise refuse to acknowledge their power. While some titles may be used, they will be used far less than in a high power-distance culture. For example, in colleges and universities in the U.S., it is far more common for students to address their instructors on a first-name basis, and engage in casual conversation on personal topics. In contrast, in a high power-distance culture like Japan, the students rise and bow as the teacher enters the room, address them formally at all times, and rarely engage in any personal conversation.

The uncertainty avoidance dimension expresses the degree to which the members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. The fundamental issue here is how a society deals with the fact the future can never be known: should we try to control the future or just let it happen? Countries exhibiting strong [uncertainty avoidance] maintain rigid codes of belief and behavior and are intolerant of unorthodox behavior and ideas . Weak [uncertainty avoidance] societies maintain a more relaxed attitude in which practice counts more than principles (Hofstede, 2012a).

Consider how one avoids uncertainty: by limiting change, adhering to tradition, and sticking to past practice. High uncertainty avoidance cultures place a very high value on history, doing things as they have been done in the past, and honoring stable cultural norms. Even though the U.S. is generally low in uncertainty avoidance, we can see some evidence of a degree of higher uncertainty avoidance related to certain social issues. As society changes, there are many who will decry the changes as they are “forgetting the past,” “dishonoring our forebears,” or “abandoning sacred traditions.” In the controversy over same-sex marriage, the phrase “traditional marriage” is used to refer to a two person, heterosexual marriage, suggesting same-sex marriage is a violation of tradition. Changing social norms creates uncertainty, and for many change is very unsettling.

In a low uncertainty avoidance culture, change is seen as inevitable, normal, and even preferable to stasis. In such a culture innovation in all areas is valued, whether it be in technology, business, social norms, or human relationship. Businesses in the U.S. that can change rapidly, innovate quickly, and respond immediately to market and social pressures are seen as far more successful. While Microsoft™ has long dominated the world market in computer operating systems, they are regularly criticized for being slow to change and to respond to changing consumer demands, which suggests a high uncertainty avoidance culture within that business. Apple™, on the other hand, has been praised for its innovation and ability to respond more quickly to market demands, suggesting a low uncertainty avoidance culture.

The long-term orientation dimension can be interpreted as dealing with society’s search for virtue . Societies with a short-term orientation generally have a strong concern with establishing the absolute Truth . They are normative in their thinking. They exhibit great respect for traditions, a relatively small propensity to save for the future, and a focus on achieving quick results. In societies with a long-term orientation, people believe that truth depends very much on situation, context and time. They show an ability to adapt traditions to changed conditions, a strong propensity to save and invest, thriftiness, and perseverance in achieving results (Hofstede, 2012a).

In a long-term culture, significant emphasis is placed on planning for the future. For example, the savings rates in France and Germany are 2-4 times greater than in the U.S., suggesting cultures with more of a “plan ahead” mentality (Pasquali & Aridas, 2012). These long-term cultures see change and social evolution are normal, integral parts of the human condition. In a short-term culture, emphasis is placed far more on the “here and now.” Immediate needs and desires are paramount, with longer-term issues left for another day. The U.S. falls more into this type. Legislation tends to be passed to handle immediate problems, and it can be challenging for lawmakers to convince voters of the need to look at issues from a long-term perspective. With the fairly easy access to credit, consumers are encouraged to buy now versus waiting. We see evidence of the need to establish “absolute Truth” in our political arena on issues such as same-sex marriage, abortion, and gun control. Our culture does not tend to favor middle grounds in which truth is not clear-cut.

The masculinity side of this dimension represents a preference in society for achievement, heroism, assertiveness and material reward for success. Society at large is more competitive. Its opposite, femininity, stands for a preference for cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life. Society at large is more consensus-oriented.

In a masculine culture, such as the U.S., winning is highly valued. We respect and honor those who demonstrate power and high degrees of competence. Consider the role of competitive sports such as football, basketball, or baseball, and how the rituals of identifying the best are significant events. The 2017 Super Bowl had 111 million viewers, (Huddleston, 2017) and the World Series regularly receives high ratings, with the final game in 2016 ending at the highest rating in ten years (Perez, 2016).

More feminine societies, such as those in the Scandinavian countries, will certainly have their sporting moments. However, the culture is far more structured to provide aid and support to citizens, focusing their energies on providing a reasonable quality of life for all (Hofstede, 2012b).

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun . Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms (Hofstede, 2012a).

Indulgent cultures are comfortable with individuals acting on their more basic human drives. Sexual mores are less restrictive, and one can act more spontaneously than in cultures of restraint. Those in indulgent cultures will tend to communicate fewer messages of judgment and evaluation. Every spring thousands of U.S. college students flock to places like Cancun, Mexico, to engage in a week of fairly indulgent behavior. Feeling free from the social expectations of home, many will engage in some intense partying, sexual activity, and fairly limitless behaviors.

Cultures of restraint, such as many Islamic countries, have rigid social expectations of behavior that can be quite narrow. Guidelines on dress, food, drink, and behaviors are rigid and may even be formalized in law. In the U.S., a generally indulgent culture, there are sub-cultures that are more restraint focused. The Amish are highly restrained by social norms, but so too can be inner-city gangs. Areas of the country, like Utah with its large Mormon culture, or the Deep South with its large evangelical Christian culture, are more restrained than areas such as San Francisco or New York City. Rural areas often have more rigid social norms than do urban areas. Those in more restraint-oriented cultures will identify those not adhering to these norms, placing pressure on them, either openly or subtly, to conform to social expectations.

Hall’s Cultural Variations

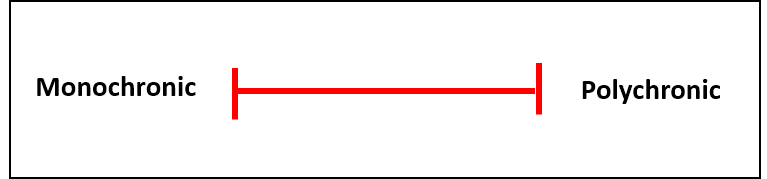

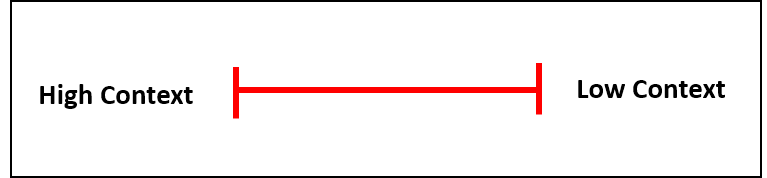

In addition to these 6 dimensions from Hofstede, anthropologist Edward T. Hall identified two more significant cultural variations (Raimo, 2008).

In a monochronic culture , like the U.S., time is viewed as linear, as a sequential set of finite time units . These units are a commodity, much like money, to be managed and used wisely; once the time is gone, it is gone and cannot be retrieved. Consider the language we use to refer to time: spending time; saving time; budgeting time; making time. These are the same terms and concepts we apply to money; time is a resource to be managed thoughtfully. Since we value time so highly, that means:

- Punctuality is valued. Since “time is money,” if a person runs late, they are wasting the resource.

- Scheduling is valued. Since time is finite, only so much is available, we need to plan how to allocate the resource. Monochronic cultures tend to let the schedule drive activity, much like money dictates what we can and cannot afford to do,

- Handling one task at a time is valued. Since time is finite and seen as a resource, monochronic cultures value fulfilling the time budget by doing what was scheduled. Compare this to a financial budget: funds are allocated for different needs, and we assume those funds should be spent on the item budgeted. In a monochronic culture, since time and money are virtually equivalent, adhering to the “time budget” is valued.

- Being busy is valued. Since time is a resource, we tend to view those who are busy as “making the most of their time;” they are seen as using their resources wisely.

In a polychronic culture , like Spain, time is far, far more fluid . Schedules are more like rough outlines to be followed, altered, or ignored as events warrant. Relationship development is more important, and schedules do not drive activity. Multi-tasking is far more acceptable, as one can move between various tasks as demands change. In polychronic cultures, people make appointments, but there is more latitude for when they are expected to arrive. David’s appointment may be at 10:15, but as long as he arrives sometime within the 10 o’clock hour, he is on time.

Consider a monochronic person attempting to do business in a polychronic culture. The monochronic person may expect meetings to start promptly on time, stay focused, and for work to be completed in a regimented manner to meet an established deadline. Yet those in a polychronic culture will not bring those same expectations to the encounter, sowing the seeds for some significant intercultural conflict.