A Simple Way to Introduce Yourself

by Andrea Wojnicki

Summary .

Many of us dread the self-introduction, be it in an online meeting or at the boardroom table. Here is a practical framework you can leverage to introduce yourself with confidence in any context, online or in-person: Present, past, and future. You can customize this framework both for yourself as an individual and for the specific context. Perhaps most importantly, when you use this framework, you will be able to focus on others’ introductions, instead of stewing about what you should say about yourself.

You know the scenario. It could be in an online meeting, or perhaps you are seated around a boardroom table. The meeting leader asks everyone to briefly introduce themselves. Suddenly, your brain goes into hyperdrive. What should I say about myself?

Partner Center

- Personality

Self-Presentation in the Digital World

Do traditional personality theories predict digital behaviour.

Posted August 31, 2021 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- What Is Personality?

- Take our Agreeableness Test

- Find a therapist near me

- Personality theories can help explain real-world differences in self-presentation behaviours but they may not apply to online behaviours.

- In the real world, women have higher levels of behavioural inhibition tendencies than men and are more likely to avoid displeasing others.

- Based on this assumption, one would expect women to present themselves less on social media, but women tend to use social media more than men.

Digital technology allows people to construct and vary their self-identity more easily than they can in the real world. This novel digital- personality construction may, or may not, be helpful to that person in the long run, but it is certainly more possible than it is in the real world. Yet how this relates to "personality," as described by traditional personality theories, is not really known. Who will tend to manipulate their personality online, and would traditional personality theories predict these effects? A look at what we do know about gender differences in the real and digital worlds suggests that many aspects of digital behaviour may not conform to the expectations of personality theories developed for the real world.

Half a century ago, Goffman suggested that individuals establish social identities by employing self-presentation tactics and impression management . Self-presentational tactics are techniques for constructing or manipulating others’ impressions of the individual and ultimately help to develop that person’s identity in the eyes of the world. The ways other people react are altered by choosing how to present oneself – that is, self-presentation strategies are used for impression management . Others then uphold, shape, or alter that self-image , depending on how they react to the tactics employed. This implies that self-presentation is a form of social communication, by which people establish, maintain, and alter their social identity.

These self-presentational strategies can be " assertive " or "defensive." 1 Assertive strategies are associated with active control of the person’s self-image; and defensive strategies are associated with protecting a desired identity that is under threat. In the real world, the use of self-presentational tactics has been widely studied and has been found to relate to many behaviours and personalities 2 . Yet, despite the enormous amounts of time spent on social media , the types of self-presentational tactics employed on these platforms have not received a huge amount of study. In fact, social media appears to provide an ideal opportunity for the use of self-presentational tactics, especially assertive strategies aimed at creating an identity in the eyes of others.

Seeking to Experience Different Types of Reward

Social media allows individuals to present themselves in ways that are entirely reliant on their own behaviours – and not on factors largely beyond their ability to instantly control, such as their appearance, gender, etc. That is, the impression that the viewer of the social media post receives is dependent, almost entirely, on how or what another person posts 3,4 . Thus, the digital medium does not present the difficulties for individuals who wish to divorce the newly-presented self from the established self. New personalities or "images" may be difficult to establish in real-world interactions, as others may have known the person beforehand, and their established patterns of interaction. Alternatively, others may not let people get away with "out of character" behaviours, or they may react to their stereotype of the person in front of them, not to their actual behaviours. All of which makes real-life identity construction harder.

Engaging in such impression management may stem from motivations to experience different types of reward 5 . In terms of one personality theory, individuals displaying behavioural approach tendencies (the Behavioural Activation System; BAS) and behavioural inhibition tendencies (the Behavioural Inhibition System; BIS) will differ in terms of self-presentation behaviours. Those with strong BAS seek opportunities to receive or experience reward (approach motivation ); whereas, those with strong BIS attempt to avoid punishment (avoidance motivation). People who need to receive a lot of external praise may actively seek out social interactions and develop a lot of social goals in their lives. Those who are more concerned about not incurring other people’s displeasure may seek to defend against this possibility and tend to withdraw from people. Although this is a well-established view of personality in the real world, it has not received strong attention in terms of digital behaviours.

Real-World Personality Theories May Not Apply Online

One test bed for the application of this theory in the digital domain is predicted gender differences in social media behaviour in relation to self-presentation. Both self-presentation 1 , and BAS and BIS 6 , have been noted to show gender differences. In the real world, women have shown higher levels of BIS than men (at least, to this point in time), although levels of BAS are less clearly differentiated between genders. This view would suggest that, in order to avoid disapproval, women will present themselves less often on social media; and, where they do have a presence, adopt defensive self-presentational strategies.

The first of these hypotheses is demonstrably false – where there are any differences in usage (and there are not that many), women tend to use social media more often than men. What we don’t really know, with any certainty, is how women use social media for self-presentation, and whether this differs from men’s usage. In contrast to the BAS/BIS view of personality, developed for the real world, several studies have suggested that selfie posting can be an assertive, or even aggressive, behaviour for females – used in forming a new personality 3 . In contrast, sometimes selfie posting by males is related to less aggressive, and more defensive, aspects of personality 7 . It may be that women take the opportunity to present very different images of themselves online from their real-world personalities. All of this suggests that theories developed for personality in the real world may not apply online – certainly not in terms of putative gender-related behaviours.

We know that social media allows a new personality to be presented easily, which is not usually seen in real-world interactions, and it may be that real-world gender differences are not repeated in digital contexts. Alternatively, it may suggest that these personality theories are now simply hopelessly anachronistic – based on assumptions that no longer apply. If that were the case, it would certainly rule out any suggestion that such personalities are genetically determined – as we know that structure hasn’t changed dramatically in the last 20 years.

1. Lee, S.J., Quigley, B.M., Nesler, M.S., Corbett, A.B., & Tedeschi, J.T. (1999). Development of a self-presentation tactics scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 26(4), 701-722.

2. Laghi, F., Pallini, S., & Baiocco, R. (2015). Autopresentazione efficace, tattiche difensive e assertive e caratteristiche di personalità in Adolescenza. Rassegna di Psicologia, 32(3), 65-82.

3. Chua, T.H.H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190-197.

4. Fox, J., & Rooney, M.C. (2015). The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161-165.

5. Hermann, A.D., Teutemacher, A.M., & Lehtman, M.J. (2015). Revisiting the unmitigated approach model of narcissism: Replication and extension. Journal of Research in Personality, 55, 41-45.

6. Carver, C.S., & White, T.L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319.

7. Sorokowski, P., Sorokowska, A., Frackowiak, T., Karwowski, M., Rusicka, I., & Oleszkiewicz, A. (2016). Sex differences in online selfie posting behaviors predict histrionic personality scores among men but not women. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 368-373.

Phil Reed, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Swansea University.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

50 Inspiring Examples: Effective Self-Introductions

By Status.net Editorial Team on September 22, 2023 — 19 minutes to read

- Structure of a Good Self-introduction Part 1

- Examples of Self Introductions in a Job Interview Part 2

- Examples of Self Introductions in a Meeting Part 3

- Examples of Casual Self-Introductions in Group Settings Part 4

- Examples of Self-Introductions on the First Day of Work Part 5

- Examples of Good Self Introductions in a Social Setting Part 6

- Examples of Good Self Introductions on Social Media Part 7

- Self-Introductions in a Public Speaking Scenario Part 8

- Name-Role-Achievements Method Template and Examples Part 9

- Past-Present-Future Method Template and Examples Part 10

- Job Application Self-Introduction Email Example Part 11

- Networking Event Self-Introduction Email Example Part 12

- Conference Self-Introduction Email Example Part 13

- Freelance Work Self-Introduction Email Example Part 14

- New Job or Position Self-Introduction Email Example Part 15

Part 1 Structure of a Good Self-introduction

- 1. Greeting and introduction: Start by greeting the person you’re speaking to and introducing yourself. For example, “Hi, my name is Jane. Nice to meet you!”

- 2. Brief personal background: Give a brief overview of your personal background, such as where you’re from or what you do. For example, “I’m originally from California, but I moved to New York a few years ago. I work in marketing for a tech company.” Related: 10 Smart Answers: “Tell Me About Yourself”

- 3. Professional experience: Highlight your relevant professional experience, including your current or previous job titles and any notable achievements. For example, “I’ve been working in marketing for about 5 years now, and I’m currently a Senior Marketing Manager at my company. Last year, I led a successful campaign that resulted in a 20% increase in sales.” Related: How to Describe Yourself (Best Examples for Job Interviews)

- 4. Skills and strengths: Mention any skills or strengths that are relevant to the conversation or the situation you’re in. For example, “I’m really passionate about data analysis and using insights to inform marketing strategy. I’m also a strong communicator and enjoy collaborating with cross-functional teams.” Related: 195 Positive Words to Describe Yourself [with Examples] 35 Smart Answers to “What Are Your Strengths?” What Are Your Strengths And Weaknesses? (Answers & Strategies)

- 5. Personal interests: Wrap up your self-introduction by mentioning a few personal interests or hobbies, which can help to humanize you and make you more relatable. For example, “In my free time, I love hiking and exploring new trails. I’m also a big fan of trying out new restaurants and cooking at home.”

- Related: Core Values List: 150+ Awesome Examples of Personal Values Best Examples of “Fun Facts About Me” What Are Your Values? How to Discover Your Values

Part 2 Examples of Good Self Introductions in a Job Interview

Try to cover these aspects:

- Current or most recent position/job

- A relevant accomplishment or strength

- Why you are excited about the company or role

Templates and Scripts

“Hello, my name is [Your Name], and I recently worked as a [Your Most Recent Position] at [Company/Organization]. I successfully managed a team of [Number] members, achieving a [Relevant Accomplishment or Growth]. I’m excited about the opportunity at [Interviewer’s Company] because [Reason Why You’re Interested].”

“Hi, I’m [Your Name], a [Current Job Title or Major Accomplishment]. I’m passionate about [Relevant Industry or Skillset] and have a proven track record of [Specific Result or Achievement]. I believe my skills and experience make me well-suited for this role at [Company], and I’m excited to explore how I can contribute to [Company Goal or Project].”

“Hi, my name is Jane Doe, and I’m the Assistant Marketing Manager at ABC Corp. I recently implemented a successful social media campaign, which increased engagement by 30%. I’m thrilled about the possibility of working with XYZ Inc. because of your innovative marketing strategies.”

“Hello, I’m John Smith, a financial analyst with five years of experience in the banking industry. I’ve consistently exceeded sales targets and helped my team win an award for excellent customer service. I’m excited to join DEF Ltd. because of your focus on sustainable and responsible investing.”

Try to tailor your introduction to the specific interview situation and always show enthusiasm for the position and company. This will show the interviewer that you are the right fit.

Related: How to Describe Yourself (Best Examples for Job Interviews)

Part 3 Examples of Good Self Introductions in a Meeting

General tips.

- Start with a greeting: Begin with a simple “hello” or “good morning.”

- State your name clearly: Don’t assume everyone knows you already.

- Mention your role in the company: Help others understand your position.

- Share relevant experience or accomplishments: Give context to your expertise.

- Be brief: Save detailed explanations for later conversations.

- Show enthusiasm: Display interest in the meeting and its objectives.

- Welcome others: Encourage a sense of connection and camaraderie.

- Basic introduction : Hi, I’m [Name], and I work as a [Your Role] in the [Department]. It’s great to meet you all.

- Involvement-focused : Good morning, everyone. I’m [Name], [Your Role]. I handle [Responsibility] in our team, and I’m looking forward to working with you on [Project].

- Experience-based : Hello! My name is [Name] and I’m the [Your Role] here. I’ve [Number of Years] of experience in [Skills or Industry], so I hope to contribute to our discussions during the meeting.

- New team member : Hi, I’m [Name]. I just joined the [Department] team as the new [Your Role]. I have a background in [Relevant Experience] and am excited to start working with you on our projects!

- External consultant : Hello everyone, my name is [Name], and I’m here in my capacity as a [Your Role] with [Your Company]. I specialize in [Skill or Industry], and I’m looking forward to partnering with your team to achieve our goals.

- Guest speaker : Good morning, I’m [Name], a [Your Position] at [Organization]. I have expertise in [Subject], and I’m honored to be here today to share my insights with you.

Related: 10 Smart Answers: “Tell Me About Yourself”

Part 4 Examples of Casual Self-Introductions in Group Settings

Template 1:.

“Hi, I’m [your name], and I’m a [profession or role]. I love [personal hobby or interest].”

“Hi, I’m Emily, and I’m a pediatric nurse. I love gardening and spending my weekends tending to my colorful flower beds.”

“Hello, I’m Mark, and I work as a data analyst. I love reading science fiction novels and discussing the intricacies of the stories with fellow book enthusiasts.”

“Hey there, I’m Jessica, and I’m a chef. I have a passion for traveling and trying new cuisines from around the world, which complements my profession perfectly.”

Template 2:

“Hey everyone, my name is [your name]. I work as a [profession or role], and when I’m not doing that, I enjoy [activity].”

“Hey everyone, my name is Alex. I work as a marketing manager, and when I’m not doing that, I enjoy hiking in the wilderness and capturing the beauty of nature with my camera.”

“Hello, I’m Michael. I work as a software developer, and when I’m not coding, I enjoy playing chess competitively and participating in local tournaments.”

“Hi there, I’m Sarah. I work as a veterinarian, and when I’m not taking care of animals, I enjoy painting landscapes and creating art inspired by my love for wildlife.”

“Hi there! I’m [your name]. I’m currently working as a [profession or role], and I have a passion for [hobby or interest].”

“Hi there! I’m Rachel. I’m currently working as a social worker, and I have a passion for advocating for mental health awareness and supporting individuals on their journeys to recovery.”

“Hello, I’m David. I’m currently working as a financial analyst, and I have a passion for volunteering at local animal shelters and helping rescue animals find their forever homes.”

“Hey, I’m Lisa. I’m currently working as a marine biologist, and I have a passion for scuba diving and exploring the vibrant underwater ecosystems that our oceans hold.”

Related: 195 Positive Words to Describe Yourself [with Examples]

Part 5 Examples of Good Self-Introductions on the First Day of Work

- Simple Introduction : “Hi, my name is [Your name], and I’m the new [Your position] here. I recently graduated from [Your university or institution] and am excited to join the team. I’m looking forward to working with you all.”

- Professional Background : “Hello everyone, I’m [Your name]. I’ve joined as the new [Your position]. With my background in [Your skills or experience], I’m eager to contribute to our projects and learn from all of you. Don’t hesitate to reach out if you have any questions.”

- Personal Touch : “Hey there! I’m [Your name], and I’ve recently joined as the new [Your position]. On the personal side, I enjoy [Your hobbies] during my free time. I’m looking forward to getting to know all of you and working together.”

Feel free to tweak these scripts as needed to fit your personality and work environment!

Here are some specific examples of self-introductions on the first day of work:

- “Hi, my name is Alex, and I’m excited to be the new Marketing Manager here. I’ve been in the marketing industry for five years and have worked on various campaigns. Outside of work, I love exploring new hiking trails and photography. I can’t wait to collaborate with you all.”

- “Hello, I’m Priya, your new Software Engineer. I graduated from XYZ University with a degree in computer science and have experience in Python, Java, and web development. In my free time, I enjoy playing the guitar and attending live concerts. I’m eager to contribute to our team’s success and learn from all of you.”

Related: Core Values List: 150+ Awesome Examples of Personal Values

Part 6 Examples of Good Self Introductions in a Social Setting

Casual gatherings: “Hi, I’m [Name]. Nice to meet you! I’m a huge fan of [hobby]. How about you, what do you enjoy doing in your free time?”

Networking events: “Hello, I’m [Name] and I work as a [profession] at [company]. I’m excited to learn more about what everyone here does. What brings you here today?”

Parties at a friend’s house: “Hi there, my name is [Name]. I’m a friend of [host’s name] from [work/school/etc]. How do you know [host’s name]?”

- Casual gathering: “Hey, my name is Jane. Great to meet you! I love exploring new coffee shops around the city. What’s your favorite thing to do on weekends?”

- Networking event: “Hi, I’m John, a website developer at XY Technologies. I’m eager to connect with people in the industry. What’s your field of expertise?”

- Party at a friend’s house: “Hello, I’m Laura. I met our host, Emily, in our college photography club. How did you and Emily become friends?”

Related: Best Examples of “Fun Facts About Me”

Part 7 Examples of Good Self Introductions on Social Media

- Keep it brief: Social media is fast-paced, so stick to the essentials and keep your audience engaged.

- Show your personality: Let your audience know who you are beyond your job title or education.

- Include a call-to-action: Encourage your followers to engage with you by asking a question or directing them to your website or other social media profiles.

Template 1: Brief and professional

Hi, I’m [Your Name]. I’m a [Job Title/Field] with a passion for [Interests or Hobbies]. Connect with me to chat about [Subject Matter] or find more of my work at [Website or Social Media Handle].

Template 2: Casual and personal

Hey there! I’m [Your Name] and I love all things [Interest or Hobby]. In my day job, I work as a [Job Title/Field]. Let’s connect and talk about [Shared Interest] or find me on [Other Social Media Platforms]!

Template 3: Skill-focused

Hi, I’m [Your Name], a [Job Title/Field] specializing in [Skills or Expertise]. Excited to network and share insights on [Subject Matter]. Reach out if you need help with [Skill or Topic] or want to discuss [Related Interest]!

Example 1: Brief and professional

Hi, I’m Jane Doe. I’m a Marketing Manager with a passion for photography and blogging. Connect with me to chat about the latest digital marketing trends or find more of my work at jdoephotography.com.

Example 2: Casual and personal

Hey there! I’m John Smith and I love all things coffee and travel. In my day job, I work as a software developer. Let’s connect and talk about adventures or find me on Instagram at @johnsmithontour!

Example 3: Skill-focused

Hi, I’m Lisa Brown, a Graphic Designer specializing in branding and typography. Excited to network and share insights on design. Reach out if you need help with creating visually appealing brand identities or want to discuss minimalistic art!

Part 8 Self-Introductions in a Public Speaking Scenario

- Professional introduction: “Hello, my name is [Your Name], and I have [number of years] of experience working in [your field]. Throughout my career, I have [briefly mention one or two significant accomplishments]. Today, I am excited to share [the main point of your presentation].”

- Casual introduction: “Hey everyone, I’m [Your Name], and I [briefly describe yourself, e.g., your hobbies or interests]. I’m really thrilled to talk to you about [the main point of your presentation]. Let’s dive right into it!”

- Creative introduction: “Imagine [paint a visual with a relevant story]. That’s where my passion began for [the main point of your presentation]. My name is [Your Name], and [mention relevant background/information].”

- Professional introduction: “Hello, my name is Jane Smith, and I have 15 years of experience working in marketing and advertisement. Throughout my career, I have helped companies increase their revenue by up to 50% using creative marketing strategies. Today, I am excited to share my insights in implementing effective social media campaigns.”

- Casual introduction: “Hey everyone, I’m John Doe, and I love hiking and playing the guitar in my free time. I’m really thrilled to talk to you about the impact of music on mental well-being, a topic close to my heart. Let’s dive right into it!”

- Creative introduction: “Imagine standing at the edge of a cliff, looking down at the breathtaking view of nature. That’s where my passion began for landscape photography. My name is Alex Brown, and I’ve been fortunate enough to turn my hobby into a successful career. Today, I’ll share my expertise on capturing stunning images with just a few simple techniques.”

Effective Templates for Self-Introductions

Part 9 name-role-achievements method template and examples.

When introducing yourself, consider using the NAME-ROLE-ACHIEVEMENTS template. Start with your name, then mention the role you’re in, and highlight key achievements or experiences you’d like to share.

“Hello, I’m [Your Name]. I’m currently working as a [Your Current Role/Position] with [Your Current Company/Organization]. Some of my key achievements or experiences include [Highlight 2-3 Achievements or Experiences].”

“Hello, I’m Sarah Johnson. I’m a Senior Software Engineer with over 10 years of experience in the tech industry. Some of my key achievements include leading a cross-functional team to develop a groundbreaking mobile app that garnered over 5 million downloads and receiving the ‘Tech Innovator of the Year’ award in 2020.”

“Hi there, my name is [Your Name]. I serve as a [Your Current Role] at [Your Current Workplace]. In my role, I’ve had the opportunity to [Describe What You Do]. One of my proudest achievements is [Highlight a Significant Achievement].”

“Hi there, my name is David Martinez. I currently serve as the Director of Marketing at XYZ Company. In my role, I’ve successfully executed several high-impact marketing campaigns, resulting in a 30% increase in brand visibility and a 15% boost in revenue last year.”

Template 3:

“Greetings, I’m [Your Name]. I hold the position of [Your Current Role] at [Your Current Company]. With [Number of Years] years of experience in [Your Industry], I’ve had the privilege of [Mention a Notable Experience].”

“Greetings, I’m Emily Anderson. I hold the position of Senior Marketing Manager at BrightStar Solutions. With over 8 years of experience in the technology and marketing industry, I’ve had the privilege of spearheading the launch of our flagship product, which led to a 40% increase in market share within just six months.”

Part 10 Past-Present-Future Method Template and Examples

Another template is the PAST-PRESENT-FUTURE method, where you talk about your past experiences, your current situation, and your future goals in a concise and engaging manner.

“In the past, I worked as a [Your Previous Role] where I [Briefly Describe Your Previous Role]. Currently, I am [Your Current Role] at [Your Current Workplace], where I [Briefly Describe Your Current Responsibilities]. Looking to the future, my goal is to [Your Future Aspirations].”

“In the past, I worked as a project manager at ABC Corporation, where I oversaw the successful delivery of multiple complex projects, each on time and within budget. Currently, I’m pursuing an MBA degree to enhance my business acumen and leadership skills. Looking to the future, my goal is to leverage my project management experience and MBA education to take on more strategic roles in the company and contribute to its long-term growth.”

“In my earlier career, I [Describe Your Past Career Experience]. Today, I’m [Your Current Role] at [Your Current Company], where I [Discuss Your Current Contributions]. As I look ahead, I’m excited to [Outline Your Future Plans and Aspirations].”

“In my previous role as a software developer, I had the opportunity to work on cutting-edge technologies, including AI and machine learning. Today, I’m a data scientist at XYZ Labs, where I analyze large datasets to extract valuable insights. In the future, I aspire to lead a team of data scientists and contribute to groundbreaking research in the field of artificial intelligence.”

“During my previous role as a [Your Previous Role], I [Discuss a Relevant Past Achievement or Experience]. Now, I am in the position of [Your Current Role] at [Your Current Company], focusing on [Describe Your Current Focus]. My vision for the future is to [Share Your Future Goals].”

“During my previous role as a Sales Associate at Maplewood Retail, I consistently exceeded monthly sales targets by fostering strong customer relationships and providing exceptional service. Now, I am in the position of Assistant Store Manager at Hillside Emporium, where I focus on optimizing store operations and training the sales team to deliver outstanding customer experiences. My vision for the future is to continue growing in the retail industry and eventually take on a leadership role in multi-store management.”

Examples of Self-introduction Emails

Part 11 job application self-introduction email example.

Subject: Introduction from [Your Name] – [Job Title] Application

Dear [Hiring Manager’s Name],

I am writing to introduce myself and express my interest in the [Job Title] position at [Company Name]. My name is [Your Name], and I am a [Your Profession] with [Number of Years] of experience in the field.

I am impressed with [Company Name]’s reputation for [Company’s Achievements or Mission]. I am confident that my skills and experience align with the requirements of the job, and I am excited about the opportunity to contribute to the company’s success.

Please find my resume attached for your review. I would appreciate the opportunity to discuss my qualifications further and learn more about the position. Thank you for considering my application.

Sincerely, [Your Name]

Related: Get More Interviews: Follow Up on Job Applications (Templates)

Part 12 Networking Event Self-Introduction Email Example

Subject: Introduction from [Your Name]

Dear [Recipient’s Name],

I hope this email finds you well. My name is [Your Name], and I am excited to introduce myself to you. I am currently working as a [Your Profession] and have been in the field for [Number of Years]. I am attending the [Networking Event Name] event next week and I am hoping to meet new people and expand my network.

I am interested in learning more about your work and experience in the industry. Would it be possible to schedule a quick call or meeting during the event to chat further?

Thank you for your time, and I look forward to hearing back from you.

Best regards, [Your Name]

Part 13 Conference Self-Introduction Email Example

Subject: Introduction from [Your Name] – [Conference or Event Name]

I am excited to introduce myself to you as a fellow attendee of [Conference or Event Name]. My name is [Your Name], and I am a [Your Profession or Industry].

I am looking forward to the conference and the opportunity to network with industry experts like yourself. I am particularly interested in [Conference or Event Topics], and I would love to discuss these topics further with you.

If you have some free time during the conference, would you be interested in meeting up for coffee or lunch? I would love to learn more about your experience and insights in the industry.

Part 14 Freelance Work Self-Introduction Email Example

Subject: Introduction from [Your Name] – Freelance Writer

Dear [Client’s Name],

My name is [Your Name], and I am a freelance writer with [Number of Years] of experience in the industry. I came across your website and was impressed by the quality of your content and the unique perspective you offer.

I am writing to introduce myself and express my interest in working with you on future projects. I specialize in [Your Writing Niche], and I believe my skills and experience would be a great fit for your content needs.

Please find my portfolio attached for your review. I would love to discuss your content needs further and explore how we can work together to achieve your goals. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Part 15 New Job or Position Self-Introduction Email Example

Subject: Introduction from [Your Name] – New [Job Title or Position]

Dear [Team or Department Name],

I am excited to introduce myself as the new [Job Title or Position] at [Company Name]. My name is [Your Name], and I am looking forward to working with all of you.

I have [Number of Years] of experience in the industry and have worked on [Your Achievements or Projects]. I am excited to bring my skills and experience to the team and contribute to the company’s success.

I would love to schedule some time to meet with each of you and learn more about your role in the company and how we can work together. Thank you for your time, and I look forward to meeting all of you soon.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can you create a powerful self-introduction script for job interviews.

To make a strong impression in job interviews, prepare a script that includes:

- Your name and current role or profession.

- Relevant past experiences and accomplishments.

- Personal skills or attributes relevant to the job.

- A brief mention of your motivation for applying.

- An engaging statement that connects your aspirations with the role or company.

How can students present a captivating self-introduction in class?

For an engaging self-introduction in class, consider mentioning:

- Your name and major.

- Where you’re from or something unique about your upbringing.

- Hobbies, interests, or extracurricular activities.

- An interesting fact or anecdote about yourself.

- Your academic or career goals and how they connect to the class.

What are tips for introducing yourself to a new team at work?

When introducing yourself to a new team at work, consider the following tips:

- Be friendly, respectful, and approachable.

- Start with your name and role, then briefly describe your responsibilities.

- Mention your background, skills, and relevant experiences.

- Share a personal interest or fun fact to add a personal touch.

- Express how excited you are to be part of the team and your desire to collaborate effectively.

How do you structure a self-introduction in English for various scenarios?

Regardless of the scenario, a well-structured self-introduction includes:

- Greeting and stating your name.

- Mentioning your role, profession, or status.

- Providing brief background information or relevant experiences.

- Sharing a personal touch or unique attribute.

- Concluding with an engaging statement, relevant to the context, that shows your enthusiasm or interest.

- Self Evaluation Examples [Complete Guide]

- 42 Adaptability Self Evaluation Comments Examples

- 40 Competency Self-Evaluation Comments Examples

- 45 Productivity Self Evaluation Comments Examples

- How to Live By Your Values

- 20+ Core Values Examples for Travel & Accommodation

Daring Leadership Institute: a groundbreaking partnership that amplifies Brené Brown's empirically based, courage-building curriculum with BetterUp’s human transformation platform.

What is Coaching?

Types of Coaching

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Find your coach

-1.png)

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

Impression management: Developing your self-presentation skills

Jump to section

What is impression management?

Examples of impression management, the theory behind impression management, impression management in the workplace, 7 impression management techniques, noticing the practice of impression management.

How much is a first impression worth?

We all know the value of a strong first impression, but not many of us know how to strategically go about creating one . Instead, we tend to cultivate two different personas. There’s our relaxed self, when we don’t feel like we have to impress. And then there are the times when we’re “on,” and we become deliberate about every word we say and move we make.

Social media has made us even more aware of the power of our personas. And that doesn’t mean that we have to be inauthentic. Understanding impression management can help us emphasize the qualities that we want to shine through and how to be more at ease with others.

Canadian social psychologist, sociologist, and writer Erving Goffman first presented the idea of impression management in the 1950s. In his book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life , Goffman uses the idea of theatre as a metaphor for human social interactions.

His theory became known as Goffman's dramaturgical analysis. It provides an interesting contextual framework for understanding human behavior.

Impression management is the sum total of actions we take — both consciously and unconsciously — to influence how others perceive us. We often attempt to manage how people see us to make us more likely to achieve our goals.

People use impression management to align how we’re seen with what we want. In general, we want other people to think of us as confident, likeable, intelligent, capable, interesting, and any number of other positive traits.

We then “adjust” our behavior to exhibit these characteristics to meet a desired goal. This is closely related to the self-presentation theory — and in fact, the two ideas are often used interchangeably.

If you’ve ever seen the musical Chicago, you’re familiar with the idea of impression management.

Our client, Roxie Hart, was an ambitious adulterer — a persona that wouldn’t have made her too sympathetic to the jury during her murder trial. Instead, she and her lawyer carefully curated a set of behaviors, actions, and even a backstory that made her seem more likeable and naive.

This impression management strategy culminated in the song, “ They Both Reached for the Gun .” Her lawyer, Billy Flynn, stepped in to manage every part of her presentation to the court, emphasizing that Roxie would only have fired a gun in self-defense.

Outside of the Cook County jail, people use impression management strategies in all kinds of ways. Here are some examples you might have experienced in the workplace:

- A person is walking into a meeting. They’ve had a rough morning and an even rougher commute. But they smile broadly and wave at each person as they walk in, hiding their bad mood and exhaustion. To all watching, they’re happy to be here.

- You’ve been working in your pajamas all day amongst a pile of paperwork and cookie crumbs. Before joining the afternoon Zoom call, you brush your hair, throw on a clean shirt, and dust the crumbs off the sofa.

- A candidate arrives for their job interview several minutes late. “So sorry,” they say breathlessly. “I was here early, but I got sent to the wrong office.”

What’s the point of this duplicity?

Well, it might not be all that inauthentic . Despite a rough morning, the first person might genuinely be thrilled to be at work — or might be trying to salvage the day. You might be extremely punctual and just ended up in the wrong place. And it’s totally possible you have no idea how those cookies got there.

On both conscious and unconscious levels, we’re aware that in different situations, we need to emphasize different aspects of our personality and behavior. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t true, just that they’re hidden (under a layer of cookie dust). We tend to engage in a constant, quiet self-monitoring that makes us aware of behaviors that don’t align with how we want to be seen.

Awareness of these internal contradictions is known as cognitive dissonance . It’s the sense of psychological discomfort that we feel when we’re doing something that contradicts our beliefs or values. We typically resolve cognitive dissonance by taking an action that’s better aligned with our beliefs, or by changing our beliefs to justify our behavior.

So in the above examples, we smile, clean up, or apologize because we want to emphasize our good nature, professionalism, and punctuality. We curate these behaviors to try to control the impressions others have of us.

Over time, the behaviors (and feedback we get based on those behaviors) inform our self-concepts. We begin to believe that we are the face that we’re putting out to the world, and to a large extent we are.

After all, a tree makes a sound if it falls in the forest, even if no one is around to hear it. But it’s hard to understand the impact of the sound — or put it into context — without an audience.

Goffman explained impression management theory using theatre as a metaphor. Our behavior in a given setting is based on three components: motives , self-presentation , and social context .

We adapt our behaviors as a means to an end. We might want to seem more likeable, competent, or attractive. The qualities we decide to emphasize are the ones that we believe are in line with the outcome we want.

If you pay attention to people’s behavior across different settings, you can often guess what they want to accomplish. The behaviors and qualities they “play up” will clue you into the goal.

Self-presentation

Self-presentation falls into two main categories: actions that are aligned with your self-image, and actions that align with the expectations of the “audience.” When people respond positively to the projected self, it has a positive impact on our self-esteem.

This effect is multiplied when the desired image feels congruent with the audience’s expectations. In other words, when people feel like they can bring their whole selves to the “performance,” and that self is welcomed and rewarded, they feel great about themselves. In the workplace, these individuals have higher job satisfaction, a sense of belonging , and increased retention.

Social context

Our public image is also closely tied to how we conduct ourselves in social situations. We inform our understanding of acceptable and unacceptable (and by extension, desirable and undesirable) behavior according to context and social norms.

When we’re successful in making the desired impressions on a group, we feel good about our social standing.

Impression management is a very important skill to have in the workplace. It affects your social influence at work, or — in other words — how others perceive you and your company.

How organizations use impression management

Organizations use it for both internal and external purposes. Internally, companies want to be seen by the industry as a good place to work. They want to appear organized, capable, supportive, and financially stable. Impression management is closely related to company culture.

Organizations also use impression management for external purposes. This might include communications with clients, partners, or investors. Managing the positive and negative impression a company has on the general public is usually called public relations or marketing.

Impression management in interviews

The classic scenario of impression management in the workplace is the job interview. Candidates and interviewers alike feel compelled to try to look “perfect.” This means coming across as “authentically perfect” — that is, pleasant, competent, and yet not so perfect as to seem disingenuous.

Interviews also involve quite a bit of self-promotion. Although self-promotion gets a bit of a bad rep, it’s often the best way for a company to find out about a candidate's skills and experience. This kind of self-promotion can help a candidate leave a positive impression on a prospective employer or client.

Note that this is only true when self-promotion is based in honesty. Lying about your skills or competencies doesn’t earn you any ingratiation points.

Interpersonal impression management

Another common use of impression management at work is building relationships with your colleagues. People usually have a work “persona,” which encompasses a range of behaviors, wardrobe choices, and even topics of conversation.

While we all shift our behavior to suit different contexts, many feel the shift that happens at work acutely. This is because of the pressure and high value placed on social capital at work, which often compounds other issues of belonging. This kind of impression management is called code-switching .

Impression management techniques can be used in a variety of situations, from job interviews to networking events. Even if it happens unconsciously, we tend to match our behavior and techniques to the situation. According to Goffman, there are 7 different types of impression management tactics we use to control how others perceive us: conformity , excuses , acclaim , flattery , self-promotion , favors , and association .

1. Conformity

Conformity means being accepted by a larger group. In order to conform, you have to (implicitly or explicitly) uphold the social norms and expectations of the group.

Group norms are the behaviors that are considered appropriate for a situation or in a particular set of people. For example, if your job may have a business-casual dress code, so cut-off jeans would feel out-of-place.

Excuses are explanations for a negative event given in order to avoid (or lessen) punishment and judgment. There are countless examples of excuses being made — in and out of the workplace. For example, you might hear people blame traffic when they’re late to meetings.

Generally speaking, you can only count on but so much social favor with excuses and apologies. Once you make an excuse, you’ve given up a little bit of authority in the situations. Do this too often, and you’ll be seen as unreliable or as a perpetual victim .

That being said, traffic, setbacks, and emergencies really do happen. Communicating these changes proactively can go a long way towards building rapport — especially if you show you’re willing to work through it.

Public recognition of someone’s accomplishments often goes a long way towards building rapport. When you acclaim someone in this way, you applaud them for their skills and success. If your team is recognition-driven, this sentiment will likely inspire others to work hard as well. It can help incentivize specific behaviors.

4. Flattery

Flattery is a technique often used to improve your relationship with someone through compliments. It’s meant to make you seem agreeable, perceptive, and pleasant. After all, who wouldn’t want to spend time with someone who always has something positive to say about them?

As with the other techniques — if not even more so — flattery can easily come across as insincere. Anchor flattering comments in specific praise, and try not to go overboard. It can be helpful to develop self-awareness and ask yourself why you’re piling it on. Are you truly impressed, or are you feeling a little insecure?

5. Self-promotion

Self-promotion is about highlighting your strengths and drawing attention to your achievements. This phenomenon is especially common in business settings, but it’s frequently seen in personal relationships, too. Because it’s self-directed, some worry that “bragging” on themselves will make them less likeable.

You can eliminate a little of this pressure by looking for spaces where talking about yourself isn’t just welcomed, but expected. Social media, job interviews, and professional networking events are great platforms for practicing self-promotion. Curate at least one space where you can own your full range of accomplishments.

Doing a favor for someone, whether in business or in everyday life, shifts the power dynamic of a relationship. It establishes the person doing the favor as “useful,” and may result in the recipient feeling like they owe something to the other party.

When favors only come with strings attached, people feel manipulated and resentful. When they’re done freely and out of a desire to be helpful, they can build mutual affinity in a relationship.

7. Association

Association means ensuring that any information shared about you, your company, and your partners is truthful and relevant. This is especially important, as being associated with someone means that everyone’s impressions reflect on each other's values and image.

Sometimes, we consciously associate with certain people to promote our self-image. Some people will network with you (and you with others) in hopes of being introduced to a larger network of contacts.

Impression management is the act of managing how other people perceive you. It is a social strategy that we employ in order to make a good impression on others and to control what they think about us.

The practice of impression management is a common one in modern society. It’s one of the main ways that people try to maintain their social status and establish themselves as a worthy individual. We may not be aware that we’re doing it, but — at any given time — we’re making dozens of decisions that are influenced by what others might think of us.

You can learn how to better manage your own persona, thrive in social situations, and understand the behavior of others by working with a coach. Coaches can help you understand what you need to project more (or less) of to get what you want, and how to align it with your authentic self.

Ready to learn how to improve your influence, both in and out of the workplace? Schedule a demo with a BetterUp coach today.

Understand Yourself Better:

Big 5 Personality Test

Allaya Cooks-Campbell

With over 15 years of content experience, Allaya Cooks Campbell has written for outlets such as ScaryMommy, HRzone, and HuffPost. She holds a B.A. in Psychology and is a certified yoga instructor as well as a certified Integrative Wellness & Life Coach. Allaya is passionate about whole-person wellness, yoga, and mental health.

Professional development is for everyone (We’re looking at you)

Goal-setting theory: why it’s important, and how to use it at work, 10 organizational skills that will put you a step ahead, 10+ interpersonal skills at work and ways to develop them, why an internship is step #1 to figuring out what to with your career, your work performance will sky-rocket with these 13 tips, how to set short-term professional goals, be cool: how to manage your emotions and avoid rage quitting, 10 essential negotiation skills to help you get what you want, the self presentation theory and how to present your best self, bringing your whole self to work — should you, how to not be nervous for a presentation — 13 tips that work (really), 25 unique email sign-offs to make a good impression, developing individual contributors: your secret weapon for growth, what are hard skills & examples for your resume, how to stop self-sabotaging: 5 steps to change your behavior, self-management skills for a messy world, make a good first impression: expert tips for showing up at your best, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case studies

- ROI of BetterUp

- What is coaching?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Personal Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Briefing

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

The HOUSTON OCTOBER 7-8 PUBLIC SPEAKING CLASS IS ALMOST FULL! RESERVE YOUR SPOT NOW

- Public Speaking Classes

- Corporate Presentation Training

- Online Public Speaking Course

- Northeast Region

- Midwest Region

- Southeast Region

- Central Region

- Western Region

- Presentation Skills

- 101 Public Speaking Tips

- Fear of Public Speaking

How to Introduce Yourself in a Presentation [with Examples]

In this post, we are going to cover the best way, a very simple three-step process that will help you introduce yourself in a presentation. A summary of the steps is below.

- Start with your name and company (or organization or school).

- Tell your audience what problem you can solve for them.

- Share some type of proof (social proof works best) that you can solve this problem.

I will break down each step into a simple-to-follow process. But first… a little background.

Want to beat stage fright, articulate with poise, and land your dream job? Take the 2-minute public speaking assessment and get the Fearless Presenter’s Playbook for FREE!

First, Identify What Your Audience Wants from Your Presentation

So, before you design your introduction, think about what your audience wants from your presentation. Why do they want to spend their valuable time listening to you? Are going to waste their time? Or, are you going to provide them with something valuable?

For instance, I have expertise in a number of different areas. I’m a public speaking coach, a keynote speaker, a best-selling author, a search engine optimization specialist, and a popular podcaster. However, if I delivered that sentence to any audience, the most likely reaction would be, “So what?” That sentence doesn’t answer any of the above questions. The statement is also really “me-focused” not “audience-focused.”

So, when I start to design my self-introduction, I want to focus just on the area of expertise related to my topic. I’m then going to answer the questions above about that particular topic. Once you have these answers, set them aside for a second. They will be important later.

How to Introduce Yourself in a Presentation in Class.

Instead, you probably want to add in a fun way to start a speech . For example, instead of introducing yourself in your class speech and starting in an awkward way, start with a startling statistic. Or start with a summary of your conclusion. Or, you could start the presentation with an inspirational quote.

Each of these presentation starters will help you lower your nervousness and decrease your awkwardness.

If you are delivering a speech in a speech competition or to an audience who doesn’t know you try this technique. Just introduce yourself by saying your name , the school you represent , and your topic . Make it easy. This way you get to your content more quickly and lower your nervousness.

Typically, after you get the first few sentences out of the way, your nervousness will drop dramatically. Since your name, school, and topic should be very easy to remember, this takes the pressure off you during the most nervous moments.

Obviously, follow the guidelines that your teacher or coach gives you. (The competition may have specific ways they want you to introduce yourself.)

How to Introduce Yourself in a Business Presentation — A Step-by-Step Guide.

In a professional setting, when new people walk into a meeting and don’t know what to expect, they will feel uncomfortable. The easiest way to ease some of that tension is to chat with your audience as they come into the room.

By the way, if you are looking for a template for an Elevator Speech , make sure to click this link.

Step #1: Start with your name and company name (or organization).

This one is easy. Just tell your audience your name and the organization that you are representing. If your organization is not a well-known brand name, you might add a short clarifying description. For instance, most people outside of the training industry have never heard of The Leader’s Institute ®. So, my step #1 might sound something like…

Hi, I’m Doug Staneart with The Leader’s Institute ®, an international leadership development company…

Still short and sweet, but a little more clear to someone who has never heard of my company.

Should you give your job title? Well… Maybe and sometimes. Add your title into the introduction only if your title adds to your credibility.

For example, if you are delivering a financial presentation and you are the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) of your company, you might mention that. Your title adds to your credibility. However, if the CFO is delivering a presentation about the value of joining a trade association, the CFO title adds little credibility. So, there is very little value in adding the title.

Step #2: Tell your audience what problem you can solve for them.

For instance, if my topic is how to deliver presentations, I have to determine why the audience would care. What problem will they have that I can help them with? For my audiences, the problem that I most often help people with is how to eliminate public speaking fear. Once I have the problem, I add that to my introduction by using the words, “I help people…”

Hi, I’m Doug Staneart with The Leader’s Institute ®, an international leadership development company, and I help people eliminate public speaking fear.

However, if my topic is How to Close a Higher Percentage of Sales Presentations , I’d likely want to alter my introduction a little. I might say something like…

Hi, I’m Doug Staneart with The Leader’s Institute ®, an international leadership development company, and I help people design more persuasive sales presentations.

I have expertise in both areas. However, I focus my introduction on just the expertise that is applicable to this audience. If I gave the first introduction to the second audience, they will likely respond by thinking, well, I don’t really get nervous speaking, so I guess I can tune out of this speech .

So, create a problem statement starting with, “I help people…” Make the statement apply to what your audience really wants.

Step #3: Share some type of proof (social proof works best) that you can solve this problem.

By the way, if you just do steps #1 and #2, your introduction will be better than most that you will hear. However, if you add Step #3, you will gain more respect (and attention) from your audience. Without adding some type of proof that you can solve this problem, you are just giving your opinion that you are an expert. However, if you can prove it, you are also proving that you are an expert.

This is the tricky part. For some reason, most people who get to this part feel like they haven’t accomplished great things, so they diminish the great accomplishments that they do have.

For instance, an easy way to offer proof is with a personal story of how you have solved that problem in the past.

A Few Examples of How to Introduce Yourself Before a Presentation.

For instance, one of my early clients was a young accountant. When I was working with him, he came up with the following introduction, “I’m Gary Gorman with Gorman and Associates CPA’s, and I help small businesses avoid IRS audits.” It was a great, audience-focused attention-getter. (No one wants to get audited.) However, as an accountant, it wasn’t like his company was getting a lot of five-star reviews on Yelp! So, he was kind of struggling with his social proof. So, I asked him a series of questions.

Me, “How many clients do you have?”

Gary, “Over 300.”

Me, “How many small business tax returns have you processed?”

Gary, “Well, at least a couple hundred a year for 15 years.”

Me, “So, at least 3000?” He nodded. “How many of your 300 clients have been audited since you have been representing them?”

He looked at me and said, “Well, none.”

So, we just added that piece of proof to his talk of introduction.

I’m Gary Gorman with Gorman and Associates CPA’s, and I help small businesses avoid IRS audits. In fact, in my career, I’ve helped clients complete over 3000 tax returns, and not a single one has ever been audited.

Here Is How I Adjust My Introduction Based on What I Want the Audience to Do.

For my proof, I have a number of options. Just like Gary, I have had a lot of clients who have had great successes. In addition, I have published two best-selling books about public speaking. I also have hundreds of thousands of people who listen to my podcast each week. So, I can pick my evidence based on what I want my audience to do.

For instance, if I’m speaking at a convention, and I want the audience to come by my booth to purchase my books, my introduction might sound like this.

Hi, I’m Doug Staneart with The Leader’s Institute ®, an international leadership development company, and I help people eliminate public speaking fear. One of the things that I’m most know for is being the author of two best-selling books, Fearless Presentations and Mastering Presentations.

However, if I’m leading a webinar, I may want the audience to purchase a seat in one of my classes. In that case, my introduction might sound like this.

Hi, I’m Doug Staneart with The Leader’s Institute ®, an international leadership development company, and I help people eliminate public speaking fear. For instance, for the last 20 years, I’ve taught public speaking classes to over 20,000 people, and I haven’t had a single person fail to reduce their nervousness significantly in just two days.

If my goal is to get the audience to subscribe to my podcast, my intro might sound like…

Hi, I’m Doug Staneart with The Leader’s Institute ®, an international leadership development company, and I help people eliminate public speaking fear. One of the ways that I do this is with my weekly podcast called, Fearless Presentations, which has over one million downloads, so far.

Use the Form Below to Organize How to Introduce Yourself in a Presentation.

The point is that you want to design your introduction in a way that makes people pause and think, “Really? That sounds pretty good.” You want to avoid introductions that make your audience think, “So what?”

If you have a speech coming up and need a good introduction, complete the form below. We will send you your answers via email!

Can You Replace Your Introduction with a PowerPoint Slide?

Is it okay to make your first slide (or second slide) in your presentation slides an introduction? Sure. A good public speaker will often add an introduction slide with a biography, portrait, and maybe even contact information. I sometimes do this myself.

However, I NEVER read the slide to my audience. I often just have it showing while I deliver the short introduction using the guide above. This is a great way to share more of your work experience without sounding like you are bragging.

For tips about how many powerpoint slides to use in a presentation , click here.

Remember that There Is a Big Difference Between Your Introduction in a Presentation and Your Presentation Starter.

When you introduce yourself in a presentation, you will often just use a single sentence to tell the audience who you are. You only use this intro if the audience doesn’t know who you are. Your presentation starter, though, is quite different. Your presentation starter should be a brief introduction with relevant details about what you will cover in your presentation.

For details, see Great Ways to Start a Presentation . In that post, we show ways to get the attention of the audience. We also give examples of how to use an interesting hook, personal stories, and how to use humor to start a presentation.

Podcasts , presentation skills

View More Posts By Category: Free Public Speaking Tips | leadership tips | Online Courses | Past Fearless Presentations ® Classes | Podcasts | presentation skills | Uncategorized

Looking to end your stage fright once and for all?

This 5-day email course gives you everything you need to beat stage fright , deliver presentations people love , and land career and business opportunities… for free!

Newly Launched - AI Presentation Maker

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

AI PPT Maker

Powerpoint Templates

PPT Bundles

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 10 Templates to Design an Introduction Slide About Yourself (Samples and Examples Included)

Siranjeev Santhanam

Introducing oneself in the workplace is one of the more under-valued and under-emphasized moments in the average professional’s career. Making a good first impression can make a big difference, whether it be dealing with managers, clients, stakeholders, or during interviews with potential employers. It can help you strengthen your professional credibility, broadcast your strengths and gain traction.

Dive deeper into this issue by checking out other blog on must have cover letter templates to use for introductions. Click here and read it now.

In the modern workplace, there are many methods and formats that professionals weaponize to create a good first impression.

Crafting a cogent and compelling PPT Presentation can be one empowering way to present oneself and get people to place their faith in you. Whether it be during interview sessions, business meetings or during engagements with clients, having a presentation can be a great way to command attention, to assert your own presence and to establish your identity during meetings.

In this blog, we’re going to be taking a look at ten templates that you can use to create an authentic introduction slide, one that you can accommodate within distinct settings, be it in interviews or in personal business conventions. These slides are 100% editable and customizable, giving you the flexibility to work with them and to redesign them exactly the way you see fit. Let’s begin.

Are you seeking similar content-rich templates on employee introduction as well? Click here and read our other blog on this subject now.

Explore our blogs on Presentation About Myself Templates and Self-Introduction Templates for an extensive collection of PowerPoint designs by SlideTeam, offering a solid framework to introduce yourself in formal settings. Craft engaging and informative presentations effortlessly with 100% editable slides, saving you time and energy.

Template 1 - Ten Minutes Presentation About Myself PowerPoint Bundle

This PPT Set helps showcase your professional journey in a concise manner. This versatile set covers essential aspects, including your work experience, personal profile, education, hobbies, and contact information. With a focus on your career map, SWOT analysis, professional qualifications, achievements, and training, the presentation highlights your unique skill set and experience. The sleek design ensures a dynamic and compelling delivery of your professional story within the allotted time, making it an ideal tool for self-introduction in professional settings. Download now!

Download this template

Template 2 - Introduce Yourself PPT Presentation Slides

Leverage the use of this well-designed PPT Bundle to create and implement an introductory presentation that leaves a lasting impression. Packed with 65 slides, the presentation is complete with a wide range of intricate tools and resources to enhance your professional profile. Legitimize your career in the eyes of the audience with the personal qualifications section and elevate your own corporate credentials with the achievements section. Establish a more personal account of yourself with the about me section. Also present are slides dedicated to your professional experience, your language skills, your hobbies, and more.

Download now

Template 3 - Be able to introduce yourself PPT presentation slides

This template can be a defining feature of your corporate success story, if used properly. It comprises 57 slides, complete with tables, graphs, charts, and a range of slides that can help master the office world. With the aid of the slides in this deck, you’re given the chance to elaborate on your career objectives, establish your own personal set of ethos and your ‘mission’, detail your work experience, education details, achievements, and map out a career path. Get it now and win over more people.

Template 4 – Self-Introduction in Interview for Job PPT Presentation Slides

Strengthen your corporate profile, control your appearance in the office and boost your chances in interviews, all with the aid of this ready-to-use PPT Deck in 39 slides. It is complete with powerful aesthetics, content-rich slides and a host of well-researched information pockets that you can harness to introduce yourself. Some key segments included within in package are about me, career, SWOT analysis, professional qualifications, achievements, training, and more. Get it now and ace your next job interview with ease!

Template 5 - How to introduce yourself PowerPoint Presentation slides

Elevate your own standing in the office and make more people notice you using this PPT Template. The 34-slide deck and is rich with content, allowing you to tailor it your needs and the stakeholder who is to view it. Some highlights incorporated into the slide include a SWOT analysis, sections dedicated to your job experience, sections dedicated to the path to career, and more. Download this template and sharpen your own appeal in the workplace, creating a more engaging corporate personal in the process.

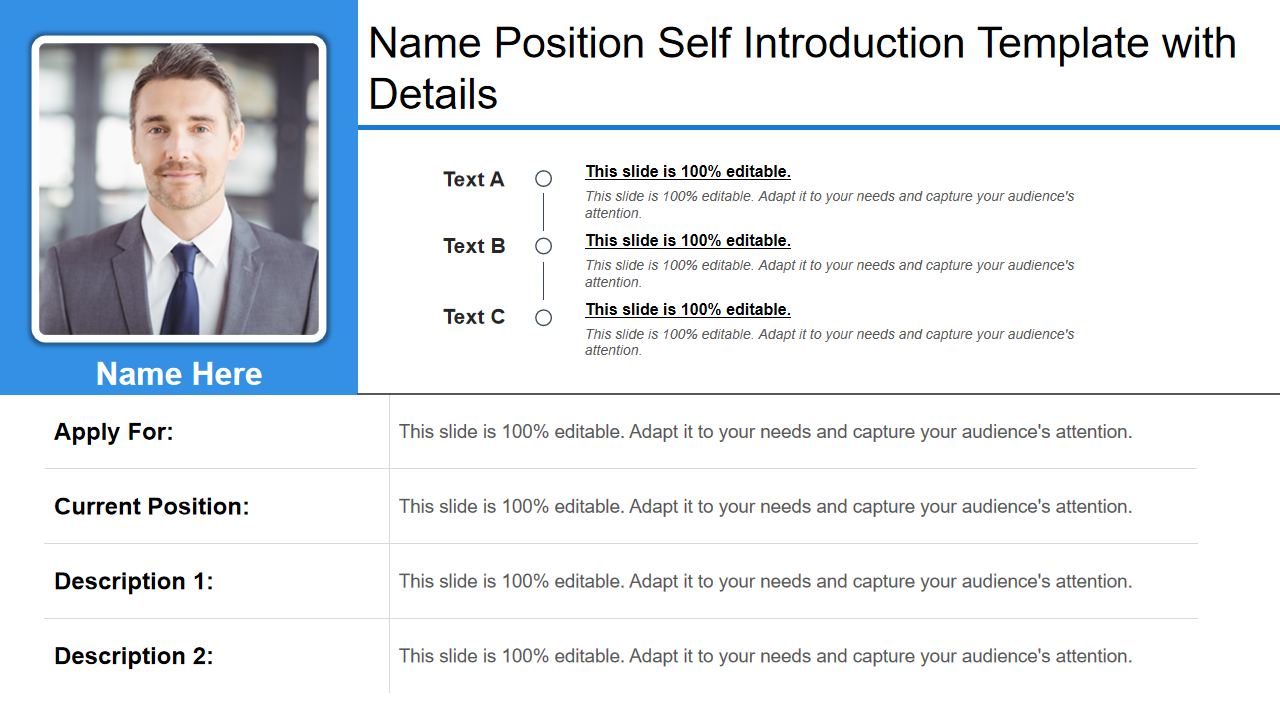

Template 6 - Name position self-introduction template with details

This one-page PPT Template can be your means to creating a more professional and polished self-introduction session. It has been segregated into smaller sections that cover aspects within the corporate experience, each of which can be customized to fit your individual needs. Space for a photograph is also present at the top left corner of the slide, along with space to accommodate other crucial information such as your job description and application requirements.

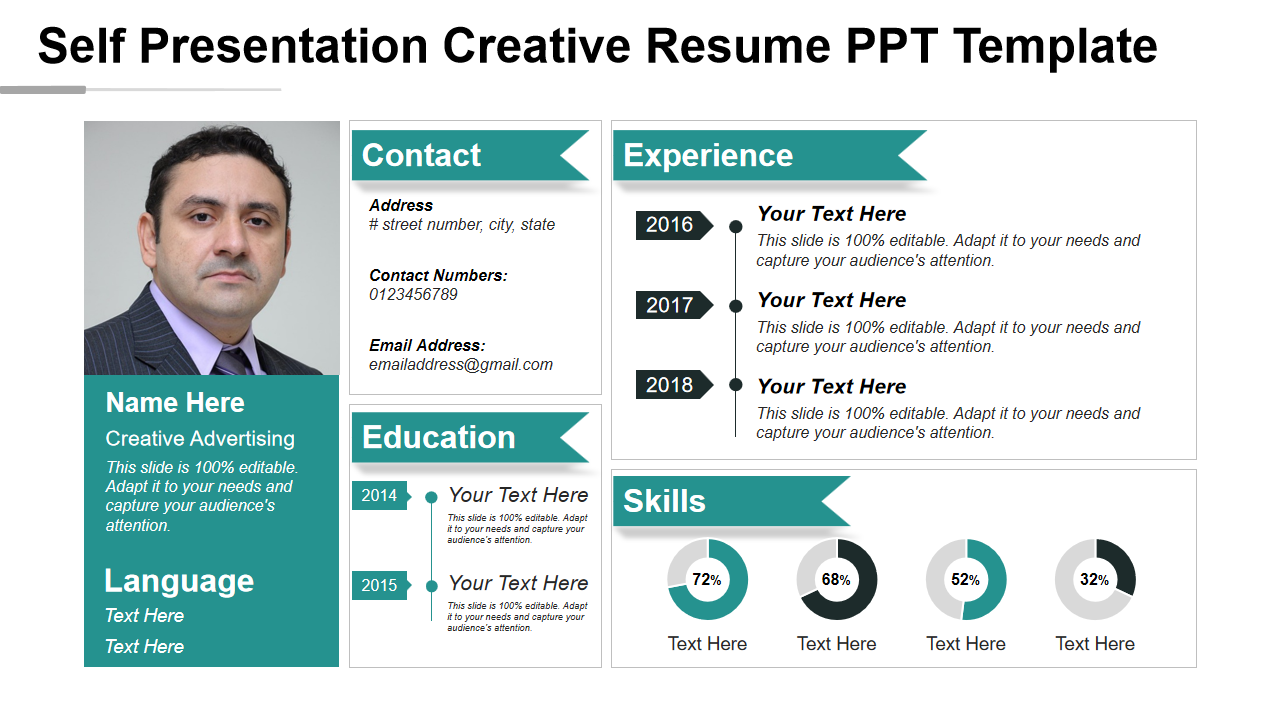

Template 7 – Self-presentation creative resume template

This PowePoint Theme can be a valuable resource for professionals seeking to make a positive first-impression in the work place, and specifically in job interviews. The high-resolution slide allows you to craft your own personalized resume theme, allowing you to stand out from the crowd and attract more attention. Some key subheadings include education, skills, contact, experience, and more. Get this template and make people notice you in the office.

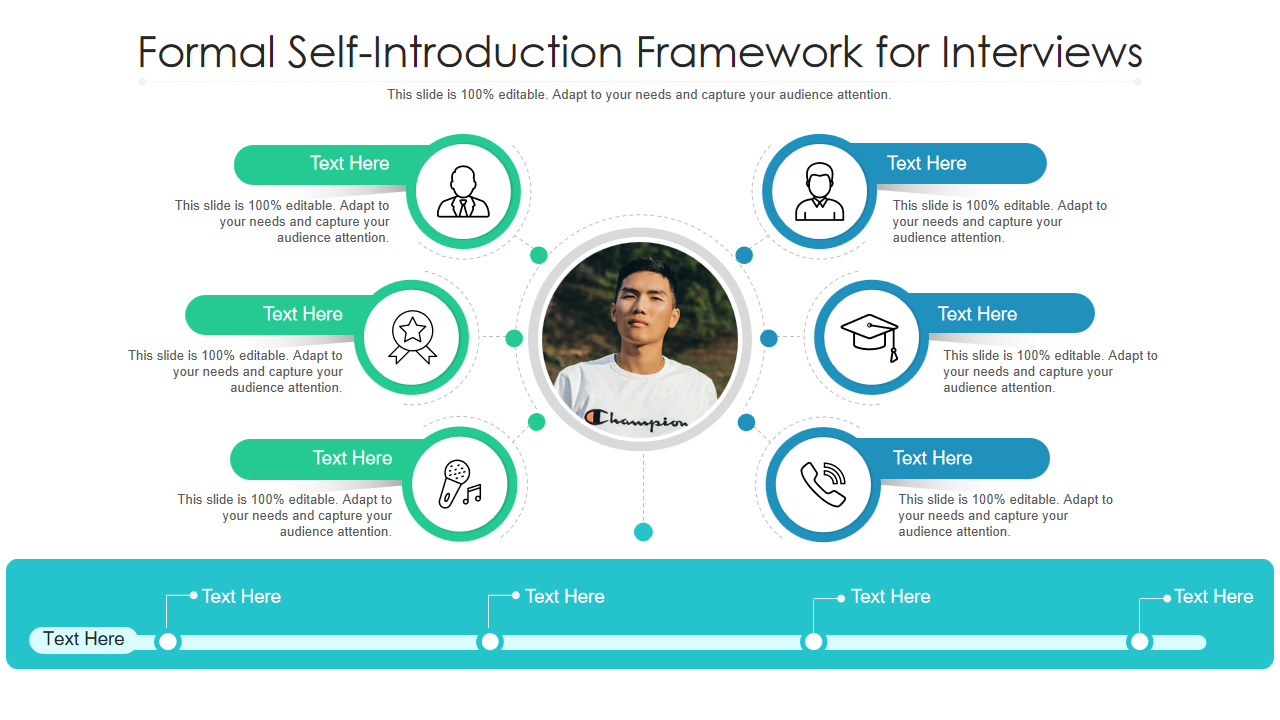

Template 8 - Formal self-introduction framework for interviews infographic template

Are you searching for a way to present yourself in curated and professional manner during interviews? Then this one-page PPT Layout is the answer. It allows you to illustrate your professional strengths and distinctive qualities in an elegant and concise manner. You can use it to draw attention to your own internal guiding ethos and to underscore your professional strengths, creativity, and personality.

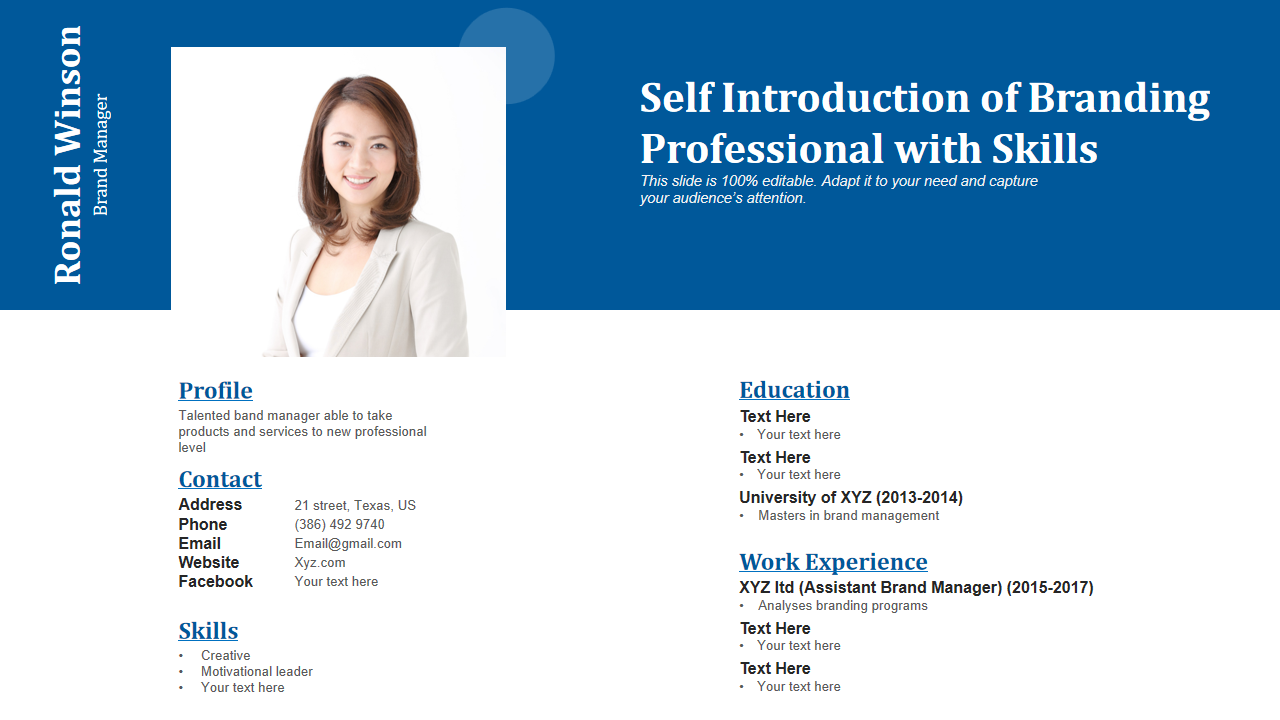

Template 9 - Self-introduction of branding professional with skills

This template offers you a creative and wholesome means of promoting yourself, giving you the tools to facilitate better connections in the workplace and impress people with your profile. The template can be re-tailored to suit the needs of a resume, or be used by its own self within the office, making it adaptable and valuable within the corporate framework. It has been endowed with some pertinent subheadings such as profile, contact, education, skills, work experience, and some space for a personalized image as well.

Template 10 - Detailed self-introduction for managing director profile interview infographic template

Are you struggling to unleash your full potential as you wade through the corporate world? Make a firmer impact on your peers and get more people to invest in you, all with the aid of this vibrant one-page template. It has been designed with the structure of a typical resume template, with the aid of some basic features such as skillset, name, hobbies, etc. It has the added advantage of a more rousing appearance with the use of contrasting white and green colour grading and prominent black font.

Template 11 - Case study self-introduction PPT inspiration

This dashboard could be your solution to getting your dues in the workplace. It is a case study template, designed to be able to add value to any presentation centred around your own professional experience. It has been divided into three major segments, challenge, solution and results, allowing you to outline your own personal challenges and results in a clear and compelling manner.

BE BOLD IS THE BEST INTRO

Introducing oneself in the right manner, with the right etiquette and professionalism, can go a long way in the workplace. The templates featured in this blog make for simple, yet effective instruments of communication, giving you the tools needed to cultivate a distinct appeal for yourself when using them. Download our self introduction ppt templates and deploy them in whichever business settings you deem necessary, adding some boldness to your own presence in the workplace.

Don’t turn away just yet! We’ve got more for you on this subject. Click here now and read our other blog on ten self-introduction templates.

FAQs on Introduction Slides

How do you introduce yourself in a slide.

Here are some steps to follow when seeking to introduce yourself in a slide within a professional setting:

Step 1 – Establish the relevant information, such as the name and title

Step 2 – Outline a brief summation of your professional history and the work experience.

Step 3 – Engage with the audience by including some basic personal information such as hobbies, etc.

Step 4 – Employ strong visuals and incorporate graphs, tables, etc. to add colour to the experience.

How can you do a five-minute presentation about yourself?

To be able to deliver a five-minute presentation on oneself, one would have to be brief, focused and concise. Here are some general tips to follow:

1 – Plan your content and determine what information needs to be included and what needs to be left out.

2 – Practice the presentation, making sure to enact rehearsals if needed to attain a degree of comfort.

3 – Design the slides and structure them in accordance with the presentation plan.

What is the best self-introduction?

There is no definitive answer to this question. However, general guidelines to improve upon and strengthen one’s self-introduction within the professional environment are:

1 – Be brief, concise and make relevant points.

2 – Underscore your strengths, accomplishments and professional accomplishments.

3 – Be confident and charismatic when presenting yourself.

4 – Be authentic; no overselling please.

Related posts:

- Top 10 Self-Introduction Templates with Samples and Examples

- Top 10 Personal Presentation Templates with Examples and Samples

- Proven Best Practices and Templates to Deliver My Presentation (Samples and Examples Inside)

- Top 10 Personal Introduction Slide Templates to Make Yourself Unforgettable

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Must-have Power BI Templates with Samples and Examples

Top 7 Communication Flow Chart Templates With Samples and Examples

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

How To Introduce Yourself Professionally [Examples + Templates]

Are you tired of the same old, boring self-introductions? It’s time to step into the spotlight and make a memorable entrance. Whether you’re facing a panel of interviewers or a room full of expectant attendees. To help you deal with this problem, this blog is going to teach you the best tips on how to introduce yourself during an interview and presentation in a professional way! So, what’s the wait? Let’s dive in!

A Framework On How To Introduce Yourself Professionally

Introducing yourself properly and sensibly can be a confusing journey, especially when you try to gather your thoughts! When trying to introduce yourself, nervousness can manifest in various ways, like brain fog, long and frequent pauses, overuse of filler words like “um,” “so,” and more! Now, to tackle this problem, you must follow this basic 3-step framework, and you are bound to give a great self-introduction in any situation with ease.

1. First Phase (The Present)