- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2021

Food safety knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices of street-cooked food handlers in North Dayi District, Ghana

- Lawrence Sena Tuglo 1 ,

- Percival Delali Agordoh 2 ,

- David Tekpor 3 ,

- Zhongqin Pan 1 ,

- Gabriel Agbanyo 3 &

- Minjie Chu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7533-9119 1

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine volume 26 , Article number: 54 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

55k Accesses

45 Citations

Metrics details

Food safety and hygiene are currently a global health apprehension especially in unindustrialized countries as a result of increasing food-borne diseases (FBDs) and accompanying deaths. This study aimed at assessing knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices (KAP) of food safety among street-cooked food handlers (SCFHs) in North Dayi District, Ghana.

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted on 407 SCFHs in North Dayi District, Ghana. The World Health Organization’s Five Keys to Safer Food for food handlers and a pretested structured questionnaire were adapted for data collection among stationary SCFHs along principal streets. Significant parameters such as educational status, average monthly income, registered SCFHs, and food safety training course were used in bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models to calculate the power of the relationships observed.

The majority 84.3% of SCFHs were female and 56.0% had not attended a food safety training course. This study showed that 67.3%, 58.2%, and 62.9% of SCFHs had good levels of KAP of food safety, respectively. About 87.2% showed a good attitude of separating uncooked and prepared meal before storage. Good knowledge of food safety was 2 times higher among registered SCFHs compared to unregistered [cOR=1.64, p =0.032]. SCFHs with secondary education were 4 times good at hygiene practices of food safety likened to no education [aOR=4.06, p =0.003]. Above GHc1500 average monthly income earners were 5 times good at hygiene practices of food safety compared to below GHc500 [aOR=4.89, p =0.006]. Registered SCFHs were 8 times good at hygiene practice of food safety compared to unregistered [aOR=7.50, p <0.001]. The odd for good hygiene practice of food safety was 6 times found among SCFHs who had training on food safety courses likened to those who had not [aOR=5.97, p <0.001].

Conclusions

Over half of the SCFHs had good levels of KAP of food safety. Registering as SCFH was significantly associated with good knowledge and hygiene practices of food safety. Therefore, our results may present an imperative foundation for design to increase food safety and hygiene practice in the district, region, and beyond.

Introduction

A report by the World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) showed that about two million incurable cases of food poisoning materialize annually in unindustrialized nations. The WHO further estimates that 600 million food-borne diseases (FBDs) each year were related to poor food safety and hygiene practice with 420,000 deaths [ 1 ], the majority attributed to meat-related vulnerabilities [ 2 ]. About, 76 million FBDs caused 325,000 hospitalizations in the USA which led to 5000 deaths [ 3 ]. The source was associated with the consumption of turkey contaminated by Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg , responsible for salmonellosis in the USA [ 4 ]. Almost, 1.3 million FBDs resulted in 21,000 hospital stays reported in England which led to 500 deaths. The contamination was due to sprouts by Escherichia coli O104 [ 3 ]. Around 53% of the food-borne problems and 31% of its associated illness were attributed to meat consumption in the Netherlands [ 2 ]. The rate of FBDs in Malaysia was 47.8% out of 100,000 people who patronized street-cooked foods [ 5 ]. In Ghana, about 65,000 persons including 5000 kids below 5 years died yearly due to FBDs [ 6 ].

The risk factors such as inappropriate time interval, unsuitable temperature, weather condition, unhygienic activities, unacceptable handling of foods, foodstuff from insecure origins, impoverished self-cleanliness, improper cleaning of cooking materials, using untreated water, and improper food storages were attributed to the causes of FBDs [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Also, neglect of hygienic measures by food handlers has been implicated as enablers for the spread of pathogenic microorganisms [ 10 ] and the cause of infections among consumers [ 11 ].

Studies recount that 12 to 18% of food-borne illnesses are attributable to contaminations [ 12 , 13 ], poor food safety, and inappropriate hygiene practices which were accredited to street-cooked food handlers (SCFHs) [ 14 , 15 ]. These SCFHs are people who are wholly or partly engaged in the food preparation, processing, and production value chain and who have a direct touch on food and cooking utensils [ 9 , 16 ]. Foods prepared by food handlers under unhygienic conditions become a public health concern both in industrialized and low-income countries [ 17 ]. Food safety and hygienic practices of SCFHs are essential to ensure that food is free from any forms of contamination through preparation and processing for consumption and to prevent the spread of FBDs [ 18 , 19 ].

Food safety knowledge (FSK) is the understanding of food learned from skills or schooling, food safety attitude (FSA) refers to sensation or belief about food safety, and food safety practice refers (FSP) to the act or use of food safety [ 20 ]. Food safety knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) are important because inadequate knowledge, poor attitude, and poor sanitation practices by SCFHs have a severe danger to food safety applications in food companies [ 21 ]; hence, KAP of food safety contributes significantly to the occurrence of food poisoning and FBDs among consumers [ 22 ].

A study conducted in Brazil among food truck food handlers revealed poor hygiene, poor clean observes, poor environments, and higher contaminated meals [ 23 ]. The problem of FBDs was higher in Southeast Asian and African counties [ 24 ]. Ma et al. [ 25 ] study in China, among street food vendors, revealed poor behaviour practices and knowledge of food safety among the respondents. Tabit and Teffo [ 26 ] in South Africa found over 60% of the respondents keep good knowledge and acceptable hygiene performance of food safety. Lema et al. [ 27 ] in Ethiopia reported that below half of the respondents obtained good food cleanliness applications. The effects of food-related illness expenditures in hospital treatments are about US$ 110 billion annually in developing countries, which resulted in decreasing production [ 28 ].

The recurrent happenings of food-related illnesses brought in its wake concerns about the food safety knowledge and hygiene among SCFHs [ 29 ]. Maintaining food safety involves establishing global laws conferring to an agreement between institutions that actualized this agenda [ 30 , 31 ]. The Government of Ghana affirmed food safety regulations in collaboration with the Food and Drug Authority (FDA) [ 30 ]. Yet, its application is undermined due to ineffective supervision by appropriate agencies [ 32 ]. The problem was due to the broad governmental assembly in cities and communities under the local administration [ 31 ]. Some local studies conducted in the four regions of Ghana such as Greater Accra, Northern, Western, and Central have reported adequate knowledge, good attitude, and positive behavioural practices of food safety and handling practices [ 11 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Studies have shown that SCFHs were not knowledgeable about the WHO’s Five Keys to Safer Food for food handlers [ 33 , 36 ] which include keeping clean, separating raw and cooked food, cooking thoroughly, keeping food at safe temperatures, and using safe water and raw materials [ 37 ].

Hence, the acceptance and the use of the KAP instrument as a problem-solving approach in this study are validated from previous researches [ 23 , 38 , 39 ]. This would adequately support the policymaking development and the change of embattled intervention policies for the prevention and control of FBDs. The KAP’s tool assessment defined in this study is considered appropriate to other frameworks if the statements in the KAP’s sections are validated. To our knowledge, no research has yet been done on KAP of food safety among SCFHs selling commonly consumable foods on the street in Volta Region, Ghana. Hitherto, the high cases of FBDs such as diarrhoea, cholera, and typhoid fever outbreak occurrences in the district are presumed to be influenced by SCFHs. The KAP of SCFHs on food safety and hygiene precautions ruins uncertainty in the district, and a swift policy to mend some causes central to the occurrence of FBDs is obligatory. This would help the District Health Directorate’s regulatory agency to plan the prevention methods. Therefore, this study assessed knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices of food safety on SCFHs in North Dayi District, Ghana.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting.

This study was a descriptive cross-sectional carried out between August and November 2020 and used a validated, pretested, and structured questionnaire to collect data from stationary SCFHs along the principal streets within North Dayi District. North Dayi District is one of the 18 administrative districts in the Volta Region, Ghana [ 40 ]. It shares boundaries with Kpando Municipal to the north, South Dayi District to the south, and Afadzato South District to the east. The entire residents of the North Dayi District are 39,913 covering 46.7% men and 53.3% women [ 40 ]. The people of the District constitute 1.9% of the total population of the Volta Region [ 40 ]. Farming is the foremost financial activity, making it one of the main sources of income in the district [ 40 ]. We carried out this study because of the recent cases of food-borne illness reported among the residents such as diarrhoea, cholera, and typhoid fever in the district [ 41 ].

Eligibility criteria

Stationary SCFHs who directly served already cooked food to customers and those who owned their outlets were included in the study. SCFHs who dissented to partake in the research were excepted including all assistants and helpers. The assistants and helpers were excluded because not all vendors had assistants or helpers and they tend to be more in numbers than the vendor-owners themselves. So for as not to allow bias in the results, we chose to sample only the vendor-owners. Moreover, vendor-owners tend to have direct responsibility for monitoring the food safety environment of their vending sites; hence, we chose to sample them as the focus of this study.

Sample size and sampling

Cochran’s formula Z 2 p (1 − p )/ e 2 [ 42 ] for unknown study populations was used. Since a similar study in the Volta Region of Ghana among the population subgroup is unavailable, 50% was used for response distribution, with 95% confidence level, and a margin of error of 5% for the populace, plus 10% non-response rate which gave us a sample size of 423.

Data collection tools

A structured questionnaire was designed based on different studies conducted globally [ 16 , 20 , 38 , 39 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Similar versions of the questionnaires were used in studies conducted in Ghana [ 47 , 48 , 49 ]. The instrument was distributed into 4 parts: socio-demographics, knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices. The statements on KAP were adapted from the WHO’s Five Keys to Safer Food guidebook for food handlers [ 37 ]. The questionnaire was firstly designed in English, then converted to local dialects, and translated back to English to ensure reliability and simplicity of the question. Four professionals in the field of the study assessed the face and the content validity of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was pretested on 12 stationary SCFHs in Tanyigbe located 7 km from the study area. The pretesting findings were not added to the main study but were used to modify some questions to improve their clarity. The most pertinent modifications done on the study instrument were a cooked meal should stay hot more than 60°C before serving, putting uncooked and prepared meal separating prevent cross-contamination, and checking and dispose of meal that past their expiry date. The data were collected through trained research assistant-led interviews which lasted for about 25 min per respondent. The interviewer-administered questionnaire was given to the SCFHs who could read and write to answer by themselves while those SCFHs who could not read and write have been aided by the research assistants in answering the questionnaire.

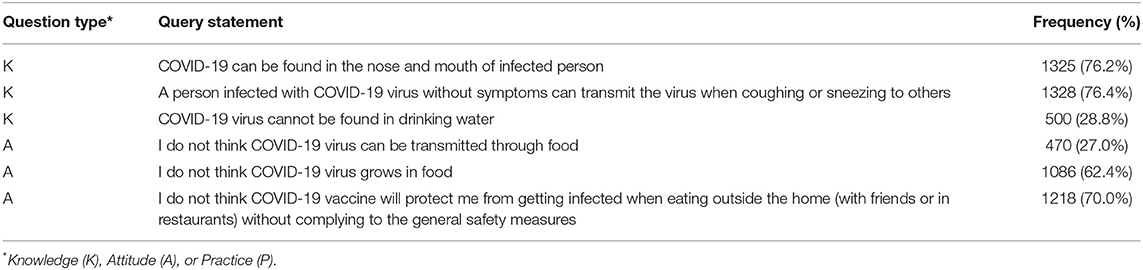

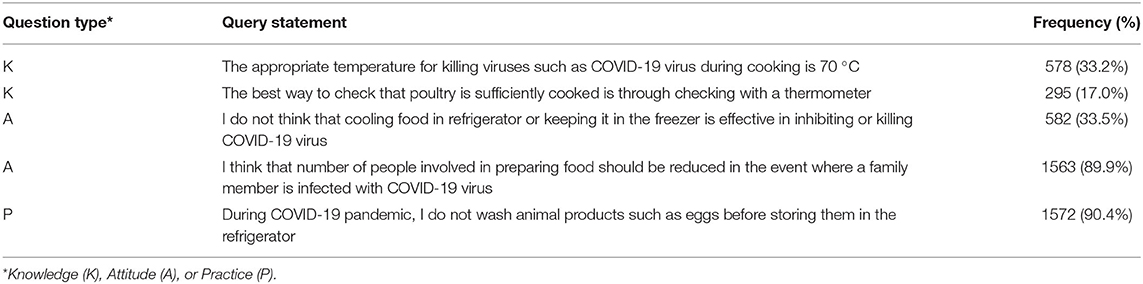

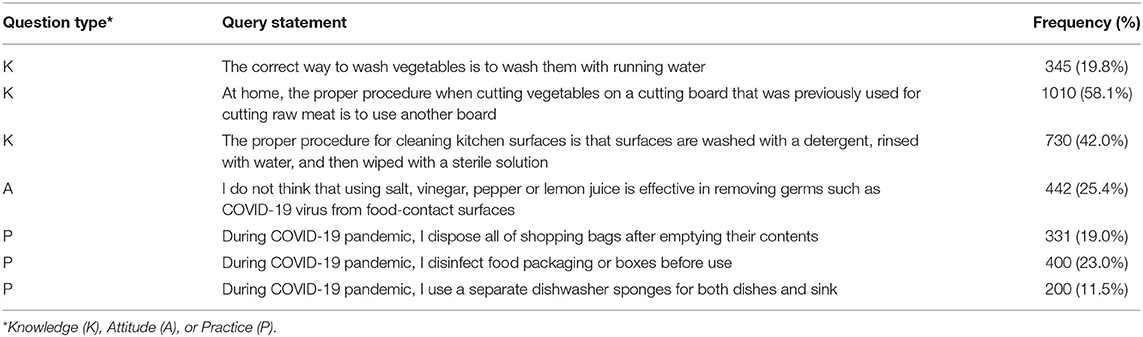

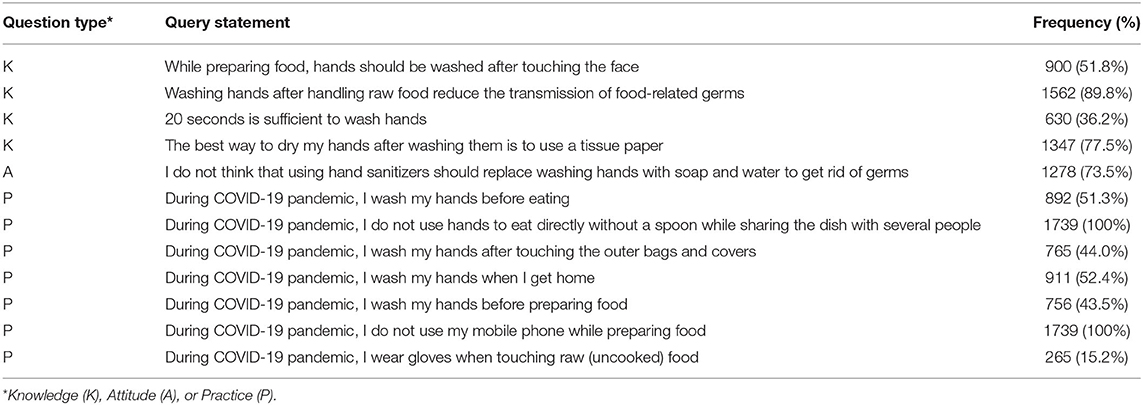

Determination of knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices on food safety

Section 2 of the questionnaire contained 10 structured questions on knowledge of food safety with 3 likely responses; “true”, “false”, and “do not know”. The questions precisely covered the respondents’ knowledge of individual cleanliness, food-borne illnesses, microbes, infection control, and sanitary practices. Each correct knowledge item reported was awarded a score of 1 point. Incorrect knowledge was awarded a 0 score (including “do not know”). In this study, if “true” is the correct answer, then “true” is score 1 point while “false” is score 0 point or otherwise reverse.

Queries relating to attitudes in the third segment of the questionnaire were designed to assess the knowledge of SCFHs on food wellbeing and hygiene. This part of the section assessed psychological state concerning views, opinion, morals, and characters to act in particular [ 21 , 48 ]. It contains 10 structured queries with 3 likely answers: “agree”, “disagree”, and “not sure”. Each correct attitude reported was awarded a score of 1 point while the other incorrect attitude option was rated a 0 score (including “not sure”). In this study, if “agree” is the correct answer, then “agree” is score 1 point while “disagree” is score 0 point or otherwise reverse.

- Hygiene practice

Section 4 of the questionnaire measured food hygiene and sanitation practices of SCFHs. It contained 10 structured queries with 2 likely answers: “yes” and “no”. Each correct hygiene practice reported was awarded a score of 1 point while incorrect hygiene practices reported were awarded a score of 0. This method of assessment was used in previous studies [ 28 ]. In this study, if “yes” is the correct answer, then “yes” is score 1 point while “no” is score 0 point or otherwise reverse.

The grouping method is appropriate and suitable for studies allied to the assessment “of food handlers” KAP of food safety and hygiene [ 27 , 28 , 34 , 46 , 47 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. The knowledge and attitude questions with “do not know” or “not sure”, thus the third option, had been presented to enable simplicity of responding by SCFHs for fascinating for thoughts considered by an undecided or doubtfulness [ 28 ]. This third option “do not know” or “not sure” always scores a 0 point due to the cumulative percentage approach adapted which considers only the acceptable response or the correct answer [ 53 ]. The cumulative percentage scoring method of assessment considers only the acceptable answer and the total cumulative score is converted to 100% [ 53 ]. The cumulative scores below 70% of the acceptable responses on WHO’s Five Keys to Safer Food-related knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices were considered as “poor”, and cumulative scores 70% and higher were considered as “good” [ 27 , 34 , 39 , 46 , 48 ].

Data analysis

Questionnaires were checked manually before entering into Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet. Coding and analysis were done in IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA; https://www.spss.com ) version 24.0. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. The disparity between categorical variable groups was verified using the Fisher exact or chi-square test where appropriate. Significant parameters were used in bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models to calculate the power of the relationships observed. A p -value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical consideration

Approval was sought from Ghana Health Service, North Dayi District Health Directorate, with the identity (NDDHD/GR/002/20) 15/07/2020. The research assistants introduced themselves and written informed permission was sought from the respondents. The research method was plainly explained to the respondents in their native dialects (English, Ewe, or Twi). Participants were identified by study numbers. The study numbers of the participants were kept in both locked files and secured computer files and accessible only to key investigators. All data were anonymized and unlinked to the respondents’ identities during the data analysis.

Demographic data

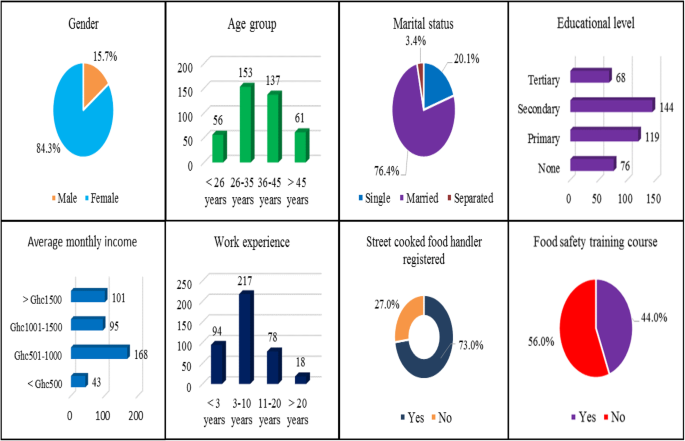

A total complete of 423 questionnaires were conveniently distributed for data collection based on the availability of SCFHs at their dedicated vending sites. Questionnaires of 407 were fully answered and collected from the respondents with a 96.2% (407/423) success rate. n = Z 2 p (1 − p )/ e 2 = 1.96 2 0.5 (1 − 0.5)/0.05 2 =384.16+38.416 =422.576. The majority ( n =343; 84.3%) of SCFHs were female, were between the age range of 26 and 35 years ( n =153; 37.6%), and were married ( n =311; 76.4%). Over one-third ( n =144; 35.4%) of SCFHs had attained secondary education. Most ( n =168; 41.3%) of SCFHs earned an average monthly income between GHc501 and GHc1000. Over half ( n =217; 53.3%) of SCFHs had 3–10 years of working experience. Regarding SCFH registered, n =297 (73.0%) reported that they have registered. More than half ( n =228; 56.0%) of SCFHs had not attended a food safety training course (Fig. 1 ).

Demographic data of respondents

Food safety knowledge

Almost all ( n = 381; 93.6%) of SCFHs knew about the washing of hands for 1 min using water and soap before touching food. The majority ( n =313; 76.9%) of SCFHs knew that similar chopping board should not be used for uncooked and prepared foods if it appears wash; n = 336 (82.6%) knew that cooked meal should stay hot before serving (more than 60°C); and n = 275 (67.6%) knew that excess meal should be kept at zone temperature and eat for the following mealtime. Most ( n =239; 58.7%) of SCFHs knew that uncooked meal should be kept individually from a prepared meal; n = 363 (89.2%) knew that treated water should be used for cooking; n = 363 (89.2%) knew that cockroach and house flies should not be allowed into the kitchen; and n = 274 (67.3%) knew that wiping cloths can spread microorganisms and cause disease. However, the majority ( n =235; 57.7%) of SCFHs did not know that food cooking utensils should not be cleaned using tap water only. Also, n = 202 (49.6%) of SCFHs did not know that fresh meat should not be stowed anyplace in the fridge once it is cool (Table 1 ).

Food safety attitude

The majority ( n =277; 68.1%) of SCFHs disagreed that regular hand cleaning throughout meal processing is needless; n = 323 (79.4%) agreed that cleaning kitchen shells lessen the danger of infection, and n = 355 (87.2%) agreed that putting uncooked and prepared meal separating stop infection. Below half ( n =181; 44.5%) of SCFHs agreed that they should be able to differentiate healthy diets and rotten food through eyeing; n =262 (64.4%) disagreed that using different knives and chopping materials for a fresh and prepared meal require more time; n = 366 (89.9%) agreed that they cough or sneeze inside the elbow if towel or paper not available; n = 291 (71.5%) agreed that checking meal for cleanliness and healthiness is important; and n =377 (92.6%) agreed that it is vital to dispose of meals that have gotten to expiring date. Nevertheless, n = 332 (81.6%) of SCFHs agreed that it is acceptable to use the same cloth for dusting and drying and n =217 (53.3%) disagreed that is unhealthy to allow prepared meal stay outside of the fridge for over 2 h (Table 2 ).

Food safety hygiene practice

The majority ( n =343; 84.3%) of SCFHs cleaned their fingers throughout meal cooking; n = 267 (65.6%) washed their cooking utensils used to cook a meal before using for a different meal; n =234 (57.5%) used different cooking bowls and chopping material if cooking a fresh and prepared meal; and n =359 (88.2%) dispersed uncooked and prepared meal before preservation. Also, n =278 (68.3%) keep prepared food at room temperature for 2 h when finished cooking; n =269 (66.1%) checked and disposed of meal past its expiry date; n =372 (91.4%) cleaned fresh food that needs no cooking before consumption; n =320 (78.6%) inspected if a meal is cooked by eyeing; and n =359 (88.2%) examined if a meal is grilled by touching it. Moreover, n =253 (62.2%) used similar kitchen cloth to clean shells and hands (Table 3 ).

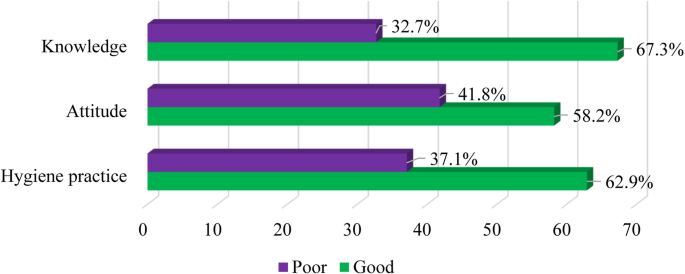

SCFH knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practice on food safety classification

A high proportion ( n =274, 67.3%; n =237, 58.2%; and n =256, 62.9%) of SCFHs had good levels in knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices on food safety (Fig. 2 ).

Levels of respondents’ knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practice on food safety

Association between knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practice and demographic data

Statistical significance was observed in the knowledge section among registered SCFHs ( p =0.031). None of the respondent’s socio-demographic data was statistically significant in the attitude section of food safety p < 0.05. The study found significant differences ( p <0.05) in the hygiene practice scores section with the educational status, average monthly income, registered SCFHs, and SCFHs completing food safety training course of food safety among SCFHs (Table 4 ). The odds ratio showed registered SCFHs were 1.6 times good at food safety knowledge likened to unregistered SCFHs [cOR=1.64 (95% CI 1.04–2.59), p =0.032]. The logistic regression analysis revealed that respondents who had secondary education were 4.1 times good at hygiene practice of food safety [aOR=4.06 (95% CI 1.63–10.11), p =0.003] compared to informal education. The respondents with average monthly income greater than GHc1500 were 4.9 times more likely to have good food safety and hygiene practices compared to those who earned less than Ghc500 average monthly income [aOR=4.89 (95% CI 1.56–15.34), p =0.006]. Meanwhile, registered SCFHs were 7.5 times more likely to have good food safety and hygiene practices compared to unregistered SCFHs [aOR=7.50 (95% CI 4.27–13.19), p <0.001]. The SCFHs who had completed a food safety training course were 6 times more likely to have good food safety and hygiene practices compared to those who had no such training [aOR=5.97 (95% CI 3.50–10.18), p <0.001] (Table 5 ).

Pearson correlation between knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practice toward food safety

The study revealed a positive correlation in the knowledge with the attitude outcomes sections (FSA) of food safety ( r =0.153, p =0.002) (Table 6 ).

The present study investigated knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices of food safety on SCFHs in North Dayi District of Volta Region, Ghana. This study showed that the majority of SCFHs had good knowledge of food safety. This would help decrease the threat to contamination of foods, food poisoning, and FBDs to the consumers. Studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, and Ghana have identified the importance of knowledge of food safety to SCFHs and have recommended training programmes on food safety to cultivate the knowledge into hygiene practices [ 14 , 27 , 34 ]. Our finding is inconsistent with previous studies done in Ethiopia and Jordan [ 38 , 45 ], however consistent with studies conducted in Ghana and Malaysia [ 47 , 54 ]. The possible reasons could be the type of food training courses received, the sample size, the scoring rubric applied, and understandings acquired on the subjects. This supported claims, creating an optimistic culture of food safety, inhibit food contamination if incorporated periodically [ 44 , 46 ]. This scenario affirms that the food safety training courses may remarkably enhance the knowledge of food handlers, especially concerning FBDs.

This study found that most of SCFHs knew about the washing of hands for 1 min using liquid and cleanser before touching food, which coincides with the study done in Iran [ 39 ]. The washing of hands with soap and water could reduce contamination of hands, cooking utensils, and cooking preparation surfaces leading to a substantive reduction of the risk of FBDs. Our finding does not corroborate with finding from a study done in Malaysia where a vast majority of SCFHs were knowledgeable of the 4th WHO Five Keys to Safer Food to keep the meal at healthy temperatures [ 20 ]. In our study, the SCFHs wrongly answered that fresh meat should be bestowed at any place in the fridge once it is cool. This misapplication of temperature could result in contamination and possibly proliferating of microbes in food. The reason is that appropriate temperatures can significantly lessen the risk at which foods will deteriorate, thereby preventing FBDs; hence for safety, foods must be held at an appropriate temperature sufficient to slow down the growth of microorganisms or kill microbes.

Attitude is one of the key elements that influence food safety and the practice and lessen the recurrence of food-related illnesses [ 51 ]. This study showed that most of SCFHs had a good attitude toward food safety. It means they understood their roles in food safety which was transmitted into attitude because they possibly serve as a vector for infectious pathogens which lead to food contamination. This agrees with studies conducted in Ghana and Haiti [ 48 , 55 ], but differs from a study done in Malaysia [ 36 ], where the majority of SCFHs had a poor attitude toward food safety. Possibly these could be due to the variances in socio-demographic characteristics, study population, and the study settings. These attitudinal variations could also be due to public reputation preference. Our study showed that visual checking was one of the key ways of differentiating healthy food from rotten ones, which concurs with a study conducted in Iran [ 39 ]. This finding is disturbing because the process of identifying food contamination cannot be performed by visual checking, since pathogens or toxins might be present in those foods without necessarily affecting SCFHs’ sensory aspects (smell, colour, or taste); therefore, food handlers who rely on visual checking for the identification of food contamination might expose consumers to an increased risk of contracting FBDs [ 39 , 56 ]. Therefore, the regulatory authorities must ensure that all SCFHs are trained professionally and certified.

The present study revealed a vast majority of SCFHs agreed that putting uncooked and prepared meal separating prevent cross-contamination, which corresponds to a study done in Haiti [ 55 ]. This act of putting fresh foods separating from cooked food could help prevent cross-contamination, which in turn may prevent infections from happening and halt FBDs. This is one of the highly endorsed public health measures to prevent cross-contamination [ 57 ]. This study found that almost all of SCFHs agreed that they coughed or sneezed into their elbows if a towel or paper is not available. Coughing and sneezing into the elbow or covering coughs and sneezes, and immediately washing the hands, could help to avert the spread of severe respiratory infections such as influenza and whooping cough. Our finding contradicts with other studies conducted in Malaysia and America; they reported that almost all respondents sneezed right away into their hands and never clean it [ 20 , 58 ]. This unpleasant attitude is harmful to the public since sneezing and coughing let out droplets of watery and perhaps transmittable microorganisms which can contaminate foods leading to FBDs.

Preservation of good sanitary behaviours is one of the goals for any food establishment, thereby its observance is vital to ensure safe meals for consumers [ 28 , 59 ]. The proportion of SCFHs in this current study with good hygiene practices of food safety corroborates with previous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia and Ghana [ 21 , 34 ]. This is an indication that SCFHs can be relied upon to act as the first-line responder to prevent several FBDs when they practice what they know. This would help reduce accidental contamination of foodstuffs due to improper management of cooking utensils and surroundings. Contradictory, in the present study, the scores obtained on the practices section were higher than hygiene practices of food safety reported in studies done in China and Nigeria [ 25 , 60 ]. The likely explanations of the difference reported could be as a result of the research population, the study cut-off used, the disparity in food safety courses, and differences in the law enforcement regimes. Our study revealed that the level of hygiene practices score was greater than the level of the attitude score attained by the SCFHs which corresponds to a study conducted in Malaysia [ 15 ]. The probable justification could be the SCFHs tend to provide responses they trust will create a good picture of their hygiene practices which account for the greater level score. The current study revealed that a vast majority of SCFHs washed their cooking utensils used to cook meals before using them for different meals, which is in line with a study done in Iran [ 39 ]. This act is acceptable because food handlers have been mostly identified as a significant vector for food contamination and responsible for FBDs [ 14 , 15 ]. Our study found that SCFHs practised wrongly by using similar kitchen cloth to clean shells and hands at the time which concurs with a study done in Malaysia [ 20 ]. The possible justification could be due to the non-compliance of the respondents to food safety training received. It could also be that they lack understandings of food safety education received. Hence, this displeasing practice may eventually result in contamination of hands and transfers of microorganisms to the consumers. This study showed that a vast majority of SCFHs cleaned fresh food that needs no cooking before consumption, which is in line with a study conducted in Malaysia [ 20 ]. This good hygiene practice is necessary to the elementary control of the spread of possibly FBDs.

Our study revealed a positive relationship between knowledge and the attitude of food safety which corresponds to earlier studies conducted in Malaysia, Iran, and Ghana [ 15 , 39 , 47 ]. Nevertheless, the strength of the correlation identified in the knowledge with the attitude scores of food safety was not strong, which implies that it is vital for the respective agency to monitor SCFH activities and enforce safety standards. Previous studies conducted in Malaysia and Iran found no significant relationship in the knowledge with the hygiene practices of food safety [ 20 , 39 ], which corresponds to our finding but contradicts with studies done in Malaysia and Ghana [ 15 , 47 ]. This result confirms the assertion that good knowledge does not affect the hygiene performance of food safety [ 61 ]. Hence, food handlers should be encouraged by food safety regulatory agencies to at least practise good hygiene irrespective of their levels of knowledge of food safety. In our study, no statistical association was found in the attitudes with the hygiene practice scores of food safety, which opposes earlier studies conducted in Malaysia, Iran, and Ghana [ 39 , 47 , 54 ]. These disparities could be due to their levels of knowledge of food safety and also possibly as a result of the kind of food safety training courses received. This present study found that registered SCFHs were more likely to have good food safety knowledge likened to unregistered SCFHs which is in line with earlier research in Lebanon [ 51 ] but differs in the study done in Malaysia [ 62 ]. The potential explanation is that maybe before SCFHs have been given their certification of registration, they probably have been taken through food safety training courses which provide them with adequate knowledge of food safety and offer them a good understanding of food poisoning, contamination, and hygiene. This shows the importance of registering food handlers who have successfully been through food safety training courses to acquire knowledge on food safety.

This study showed that the odds of good hygiene practices were higher among SCFHs who had secondary education likened to those with no formal education which is in line with a study conducted in Ethiopia [ 12 ]. In contrast to our findings, other studies conducted in Ethiopia and Ghana found SCFHs with primary education as more likely to have good hygiene practices of food safety likened to secondary education [ 27 , 34 ]. The possible reasons are because most food preparation skills, personal hygiene, and cleanliness are learned from friends, relatives, parents, and media but not necessarily from formal education. However, a lower level of education reduces awareness but the higher one gets educated the better the knowledge which affects their attitude and eventually may reflect into hygiene practices. It implies that food handlers should be encouraged to attain at least basic education before engaging into the cooking business, although it serves as the first sources of income for most uneducated people in the societies. Nevertheless, a study conducted in Ghana showed that regardless of educational background, the food safety actions of SCFHs remain an issue in many nations [ 48 ].

The present study showed that SCFHs who earned average monthly income above GHc1500 were more likely to have good hygiene practices compared to respondents who earned less than Ghc500. Our finding confirms a study conducted in Ethiopia and Jordan that found good hygiene practice among food handlers with higher monthly income than those with lower higher monthly income [ 27 , 63 ]. The possible justification is that SCFHs with high monthly income can afford to purchase items needed to establish themselves in hygienic environments and afford more employees to help in cleaning and waste treatment which could result in a reduction in food poisoning and cross-contamination. This means the high monthly income of food handlers determine their ways of hygiene practices, purchasing more cooking utensils for preparing different meals and managing their leftovers foods to prevent contamination.

The present study showed that registered SCFHs were in favour of good hygiene practices of food safety than the unregistered. The likely description is because of the food safety training courses they received before being registered as food handlers which provides them with an in-depth and comprehensive understanding of hygiene practices such as proper handling of food, personal cleanliness, and sanitation while preparing food. However, there is no research found relating registration of food handlers with hygiene practice scores; hence, the lack of the associated literature offers difficulties to compare our finding to collective results reasonably with concrete answered questions. Nonetheless, our finding shows the importance of registering food handlers after they have been through food safety training courses to encourage them to practise good hygiene.

This study found that SCFHs who have completed training courses on food safety were in favour of good hygiene practices of food safety likened to respondents who had not. Our finding asserts with previous studies done in Ethiopia, Malaysia, and Ghana [ 36 , 38 , 47 ]. The probable justification is that SCFHs who have completed food safety training courses had gained the talents and awareness necessary to handle food safely and sustain great ethics of self-cleanness and hygiene practices. Our finding affirms the assertion that training upsurges understanding of food safety which might reflect into hygiene practices [ 48 ]. Hence, a lack of or inadequate training of SCFHs on food safety may inadvertently result in poor hygiene practices, thereby encouraging food contamination [ 26 , 36 ]. This implies providing food safety training to food handles is important to keep consumers from food poisoning and other wellbeing dangers that could arise from eating unsafe food.

In this present study, it is significant to highpoint SCFHs’ knowledge, attitudes, and hygiene practices are unpredictable from the study conceded, though most of SCFHs properly responded by answering appropriately to related questions of WHO’s Five Keys to Safe Foods guidelines for food handlers. This theoretic-based assessment of the KAP method applied to assessed food handlers’ food safety KAP has some limitations. Firstly, the postulation that the received knowledge on food safety is translated into attitude is not entirely true. The existence of a social desirability bias could similarly have added to the discrepancy amid interview-responded KAP of SCFHs. Social desirability bias is the propensity of SCFHs to provide publically anticipated answers which will be regarded approvingly by people [ 64 ]. This proclivity has been shown by their descriptions and overrating socially anticipated KAP questions on food safety. Secondly, as we beforehand mentioned, the research assistants revealed their identities and the purpose of the study to the SCFHs; therefore, the SCFHs were mindful of the hygiene practices and the significance of observing them, but they remained keen to acknowledge their nonconformity and these could likely affect the self-reported hygiene practices. Thirdly, the unavailability of sufficient data from related studies in the district impedes an evaluative comparison of our findings to determine an improvement of food safety KAP among SCFHs; therefore, our findings ought to be interpreted with caution. However, due to the representative nature of the sample assessed, the findings of this study can be generalized to other SCFHs in the district. After all, it makes a substantial impact concerning food safety KAP in North Dayi District because it is the first study conducted in the district that presents an imperative foundation for design to increase food safety and hygiene practice in the district, region, and beyond.

Over half of the respondents had good levels of KAP of food safety. This study found a significant relationship in the knowledge and hygiene practice scores of food safety with SCFH registration. This shows the importance of strict enforcement of registration and certification of SCFHs by regulatory agencies as a means of protecting the consuming public. Therefore, the government agency through FDA should intensify the vitality of undertaking food safety training on WHO’s Five Keys to Safer Food by food handlers before being registered. Furthermore, the District Health Directorate should properly and effectively supervise food handlers engaging in cooking businesses to ensure they transmit the link between knowledge with the attitude of food safety into hygiene practice. Further studies should assess the kind of food safety training modules received and their impacts on the KAP of WHO’s Five Keys to Safer Foods as well as evaluating their hygiene practices with observational checklists.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical consideration but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

World Health Organization WHO. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007-2015: World Health Organization; 2015.

Brandwagt D, van den Wijngaard C, Tulen AD, Mulder AC, Hofhuis A, Jacobs R, et al. Outbreak of Salmonella Bovismorbificans associated with the consumption of uncooked ham products, the Netherlands, 2016 to 2017. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23:317–35.

Google Scholar

Navarro-Garcia F. Escherichia coli O104: H4 pathogenesis: an enteroaggregative E. coli/Shiga toxin-producing E. coli explosive cocktail of high virulence. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli Other Shiga Toxin-Producing E coli. 2015;1:503–29.

Etter AJ, West AM, Burnett JL, Wu ST, Veenhuizen DR, Ogas RA, et al. Salmonella Heidelberg food isolates associated with a Salmonellosis outbreak have enhanced stress tolerance capabilities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85:1–22.

WPSE, Netty D, Sangaran G. Paper review of factors, surveillance and burden of food borne disease outbreak in Malaysia. Malaysian J public Heal Med. 2013;13:98–105.

Monney I, Agyei D, Owusu W. Hygienic practices among food vendors in educational institutions in Ghana: the case of Konongo. Foods. 2013;2(3):282–94. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods2030282 .

Fan YX, Liu XM, Bao YD. Analysis of main risk factors causing foodborne diseases in food catering business. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;45:543–6.

Cheng Y, Zhang Y, Ma J, Zhan S. Food safety knowledge, attitude and self-reported practice of secondary school students in Beijing, China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–13.

Saad M, See TP, Adil MAM. Hygiene practices of food handlers at Malaysian government institutions training centers. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2013;85:118–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.344 .

Abdalla MA, Suliman SE, Bakhiet AO. Food safety knowledge and practices of street foodvendors in Atbara City (Naher Elneel State Sudan). African J Biotechnol. 2009;8:6967–71.

Ayeh-Kumi PF, Quarcoo S, Kwakye-Nuako G, Kretchy JP, Osafo-Kantanka A, Mortu S. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among food vendors in Accra, Ghana. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2009;32:1–8.

Dagne H, Raju RP, Andualem Z, Hagos T, Addis K. Food safety practice and its associated factors among mothers in Debarq Town, Northwest Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;1:1–9.

Kuchenmüller T, Hird S, Stein C, Kramarz P, Nanda A, Havelaar AH. Estimating the global burden of foodborne diseases-a collaborative effort. Eurosurveillance. 2009;14:1–13.

Ayaz WO, Priyadarshini A, Jaiswal AK. Food safety knowledge and practices among Saudi mothers. Foods. 2018;7(12):193–208. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7120193 .

Sani NA, Siow ON. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers on food safety in food service operations at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Food Control. 2014;37:210–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.036 .

Oridota SE, Ochulo NF, Akanmu ON, Olajide TO, Soriyan OO. Food hygiene and safety practices of food handlers and its determinants in Lagos State. J Med Res Pract. 2014;3:37–41.

Chukuezi CO. Food safety and hyienic practices of street food vendors in Owerri, Nigeria. Stud Sociol Sci. 2010;1:50–7.

Dun-Dery EJ, Addo HO. Food hygiene awareness, processing and practice among street food vendors in Ghana. Food Public Heal. 2016;6:65–74.

Tefera T, Mebrie G. Prevalence and predictors of intestinal parasites among food handlers in Yebu town, southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–13.

Soon JM, Wahab IRA, Hamdan RH, Jamaludin MH. Structural equation modelling of food safety knowledge, attitude and practices among consumers in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2020;15:1–12.

Sharif L, Al-Malki T. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Taif University students on food poisoning. Food Control. 2010;21(1):55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.03.015 .

Kim J, Cho Y. Convergence evaluating food safety knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding food handler. J Korea Converg Soc. 2019;10:73–8.

Isoni Auad L, Cortez Ginani V, Stedefeldt E, Yoshio Nakano E, Costa Santos Nunes A, Puppin Zandonadi R. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Brazilian food truck food handlers. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1784–803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081784 .

Zhao Y, Yu X, Xiao Y, Cai Z, Luo X, Zhang F. Netizens’ food safety knowledge, attitude, behaviors, and demand for science popularization by WeMedia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):730–40. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030730 .

Ma L, Chen H, Yan H, Wu L, Zhang W. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of street food vendors and consumers in Handan, a third tier city in China. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1128–39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7475-9 .

Tabit FT, Teffo LA. An assessment of the food safety knowledge and attitudes of food handlers in hospitals. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:311–22.

Lema K, Abuhay N, Kindie W, Dagne H, Guadu T. Food hygiene practice and its determinants among food handlers at University of Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:1129–37. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S262767 .

Yenealem DG, Yallew WW, Abdulmajid S. Food safety practice and associated factors among meat handlers in Gondar town: a cross-sectional study. J Environ Public Health. 2020;1:1–7.

Adane M, Teka B, Gismu Y, Halefom G, Ademe M. Food hygiene and safety measures among food handlers in street food shops and food establishments of Dessie town, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–13.

Ababio PF, Lovatt P. A review on food safety and food hygiene studies in Ghana. Food Control. 2015;47:92–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.06.041 .

Yeleliere E, Cobbina SJ, Abubakari ZI. Review of microbial food contamination and food hygiene in selected capital cities of Ghana. Cogent Food Agric. 2017;3:1–12.

Ghana Standard Authority GSA. Personal communication with standard documentation department. 2013.

Sarkodie NA, Bempong EK, Tetteh ON, Saaka AC, Moses GK. Assessing the level of hygienic practices among street food vendors in Sunyani township. Pakistan J Nutr. 2014;13(10):610–5. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2014.610.615 .

Odonkor ST, Kurantin N, Sallar AM. Food safety practices among postnatal mothers in Western Ghana. Int J Food Sci. 2020;1:1–10.

Monney I, Agyei D, Ewoenam BS, Priscilla C, Nyaw S. Food hygiene and safety practices among street food vendors: an assessment of compliance, institutional and legislative framework in Ghana. Food public Heal. 2014;4:306–15.

Rahman M, Arif MT, Bakar K, bt Tambi Z. Food safety knowledge, attitude and hygiene practices among the street food vendors in Northern Kuching city, Sarawak. Borneo Sci. 2012;31:95–103.

World Health Organization WHO. Five Keys to Safer Food Manual; Department of Food Safety, Zoonoses and Foodborne Disease. 2006; www.who.int/entity/foodsafety/ .

Azanaw J, Gebrehiwot M, Dagne H. Factors associated with food safety practices among food handlers: facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):683–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4702-5 .

Fariba R, Gholamreza JK, Saharnaz N, Ehsan H, Masoud Y. Knowledge, attitude, and practice among food handlers of semi-industrial catering: a cross sectional study at one of the governmental organization in Tehran. J Environ Heal Sci Eng. 2018;16(2):249–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40201-018-0312-8 .

Ghana Statistical Service GSS. Population and housing census 2010 district and analytical report. 2010.

GHS GHS. Annual report, Ghana Health Service: GHS; 2020.

Cochran WG. Sampling technique. Third edit. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1977.

Byrd-Bredbenner C, Berning J, Martin-Biggers J, Quick V. Food safety in home kitchens: a synthesis of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):4060–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10094060 .

Hashanuzzaman M, Bhowmik S, Rahman MS, Zakaria MUMA, Voumik LC, Mamun A-A. Assessment of food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of fish farmers and restaurants food handlers in Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2020;6:1–8.

Osaili TM, Jamous DOA, Obeidat BA, Bawadi HA, Tayyem RF, Subih HS. Food safety knowledge among food workers in restaurants in Jordan. Food Control. 2013;31(1):145–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.09.037 .

Soares LS, Almeida RCC, Cerqueira ES, Carvalho JS, Nunes IL. Knowledge, attitudes and practices in food safety and the presence of coagulase-positive staphylococci on hands of food handlers in the schools of Camaçari, Brazil. Food Control. 2012;27(1):206–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.03.016 .

Amegah KE, Addo HO, Ashinyo ME, Fiagbe L, Akpanya S, Akoriyea SK, et al. Determinants of hand hygiene practice at critical times among food handlers in educational institutions of the Sagnarigu municipality of Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health Insights. 2020;14:1–10.

Akabanda F, Hlortsi EH, Owusu-Kwarteng J. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of institutional food-handlers in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):40–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3986-9 .

Apanga S, Addah J, Sey DR. Food safety knowledge and practice of street food vendors in rural Northern Ghana. Food Public Heal. 2014;4:99–103.

Adesokan HK, Akinseye VO, Adesokan GA. Food safety training is associated with improved knowledge and behaviours among foodservice establishments’ workers. Int J Food Sci. 2015;1:1–8.

Bou-Mitri C, Mahmoud D, El Gerges N, Jaoude MA. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in Lebanese hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Food Control. 2018;94:78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.06.032 .

Derso T, Tariku A, Ambaw F, Alemenhew M, Biks GA, Nega A. Socio-demographic factors and availability of piped fountains affect food hygiene practice of food handlers in Bahir Dar Town, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):628–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2965-2 .

Al RA. On the contribution of student experience survey regarding quality management in higher education: an institutional study in Saudi Arabia. J Serv Sci Manag. 2010;3:464–9.

Siau AMF, Son R, Mohhiddin O, Toh PS, Chai LC. Food court hygiene assessment and food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in Putrajaya. Int Food Res J. 2015;22:1843–54.

Samapundo S, Climat R, Xhaferi R, Devlieghere F. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Food Control. 2015;50:457–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.09.010 .

Murray R, Glass-Kaastra S, Gardhouse C, Marshall B, Ciampa N, Franklin K, et al. Canadian consumer food safety practices and knowledge: foodbook study. J Food Prot. 2017;80(10):1711–8. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-17-108 .

Zhang H, Lu L, Liang J, Huang Q. Knowledge, attitude and practices of food safety amongst food handlers in the coastal resort of Guangdong, China. Food Control. 2015;47:457–61.

Berry TD, Fournier AK. Examining university students’ sneezing and coughing etiquette. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(12):1317–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2014.09.003 .

Khanal G, Poudel S. Factors associated with meat safety knowledge and practices among butchers of Ratnanagar municipality, Chitwan, Nepal: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pacific J Public Heal. 2017;29(8):683–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539517743850 .

Faremi FA, Olatubi MI, Nnabuife GC. Food safety and hygiene practices among food vendors in a Tertiary Educational Institution in South Western Nigeria. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2018;8(2):59–70. https://doi.org/10.9734/EJNFS/2018/39368 .

Fadaei A. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices of food workers about food hygiene in Shahrekord restaurants, Iran. World Appl Sci J. 2015;33:1113–7.

Radu S, Othman M, Toh PS, Chai LC. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practices concerning food safety among restaurant workers in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Food Sci Qual Manag. 2014;32:20–7.

Osaili TM, Al-Nabulsi AA, Krasneh HDA. Food safety knowledge among foodservice staff at the universities in Jordan. Food Control. 2018;89:167–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.02.011 .

Jespersen L, MacLaurin T, Vlerick P. Development and validation of a scale to capture social desirability in food safety culture. Food Control. 2017;82:42–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.06.010 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Nantong University, 9 Seyuan Road, Nantong, Jiangsu, China

Lawrence Sena Tuglo, Zhongqin Pan & Minjie Chu

Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana

Percival Delali Agordoh

North Dayi District Health Directorate, Volta Region, Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana

David Tekpor & Gabriel Agbanyo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MC and PDA conceived and designed the study. LST drafted the manuscript. DT and GA coordinated the data collection. ZP participated in the data collection and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Minjie Chu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Approval was sought from Ghana Health Service, North Dayi District Health Directorate, with the identity (NDDHD/GR/002/20) 15/07/2020. Written informed permission was sought, and the research method was plainly explained to the respondents in their native dialects (English, Ewe, or Twi).

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tuglo, L.S., Agordoh, P.D., Tekpor, D. et al. Food safety knowledge, attitude, and hygiene practices of street-cooked food handlers in North Dayi District, Ghana. Environ Health Prev Med 26 , 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00975-9

Download citation

Received : 22 February 2021

Accepted : 19 April 2021

Published : 03 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-021-00975-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Food safety

- Street-cooked food handlers

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine

ISSN: 1347-4715

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research note

- Open access

- Published: 22 October 2019

Factors associated with food safety practices among food handlers: facility-based cross-sectional study

- Jember Azanaw 1 ,

- Mulat Gebrehiwot 1 &

- Henok Dagne 1

BMC Research Notes volume 12 , Article number: 683 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

78k Accesses

51 Citations

Metrics details

The primary objective of this study was to assess factors associated with food safety practices among food handlers in Gondar city food and drinking establishments. The facility-based cross-sectional study was undertaken from March 3 to May 28, 2018, in Gondar city. Simple random sampling method was used to select both establishments and the food handlers. The data were collected through face-to-face interview using pre-tested Amharic version of the questionnaire. Data were entered and coded into Epi info version 7.0.0 and exported to SPSS version 22 for analysis.

One hundred and eighty-eight (49.0%) had good food handling practice out of three hundred and eighty-four food handlers. Marital status (AOR: 0.36, 95% CI 0.05, 0.85), safety training (AOR: 4.01, 95% CI 2.71, 9.77), supervision by health professionals (AOR: 4.10, 95% CI 1.71, 9.77), routine medical checkup (AOR: 8.80, 95% CI 5.04, 15.36), and mean knowledge (AOR: 2.92, 95% CI 1.38, 4.12) were the factors significantly associated with food handling practices. The owners, managers and local health professionals should work on food safety practices improvement.

Introduction

Food safety continues as a critical problem in developed and developing nations for people, food companies and food control officials [ 1 , 2 ]. Food-borne diseases (FBD) are associated with outbreaks and threatens global public health security and has got an international concern [ 3 ]. Food safety is a growing public health issue [ 4 ]. FBD is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality rates [ 5 ]. The worldwide incidence and financial expenses of food-borne diseases are hard to determine [ 6 ]. However, reports estimate that 2.1 million individuals died each year as a result of foodborne disease [ 5 ].

According to the WHO, FBDs in developing nations are serious because of bad hygienic food handling methods, bad understanding and absence of infrastructure [ 7 ]. This is due to the prevailing poor food handling and sanitation practices, inadequate food safety laws, weak regulatory systems, lack of financial resources, etc. [ 6 , 8 ]. Evidence revealed that around 70% of diarrhoea cases were attributed to food-borne routes in developing countries [ 6 ]. Like other developing countries, the burden of food-borne diseases is growing in Ethiopia [ 18 ].

Approximately 10 to 20% of FBD outbreaks are because of contamination due to poor food handling practice of the food handlers [ 9 ]. In the absence of well-maintained and proper food handling practices in mass catering establishments have the potential to impart a disastrous effect on human health [ 6 , 11 ].

Good personal hygiene and food handling practices are important for preventing the transmission of pathogens from food handlers to the consumers [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Close to 75% of food-borne illness outbreaks are attributed to lack of safe food handling practices by food handlers in food service establishments [ 5 ]. Food handlers play a key role in ensuring strict adherence to food safety principles throughout the whole process [ 15 ].

There is a high expansion of food establishments observed in the country including Gondar city. But ensuring safe food service has been one of the major challenges and concerns for producers, consumers and public health officials. Studies revealed that lack of basic sanitary facilities/infrastructures, poor knowledge and practice of hygiene and sanitation among food handlers in food service establishments, and negligence in safe food handling are major reasons of poor food safety practice in food establishments [ 16 , 17 ]. Therefore, it is very essential to identify factors affecting safe food handling practices, especially during preparation and serving. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate factors associated with food safety practice among food handlers in Gondar city food establishments.

This facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted from March 3 to May 28, 2018 at Gondar city. Gondar city is one of the highly populated cities in northwest Ethiopia. There were a total of 326 food establishments and 4232 food handlers in Gondar city according to tourism office data. The city is found at 738 km away from Addis Ababa the capital city of Ethiopia. Ninety-eight food establishments were included using the rule of thumb by taking 30% of the total food establishments. n = N × 30% = 326 × 30/100 = 97.8 ≈ 98 none star food establishments.

The sample size was computed using a single population proportion formula with 95% CI, 5% marginal error (d) and p = 52% proportion of food handlers having good food handling practice from the previous study [ 19 ]. Based on these assumptions, 384 food handlers were included in the study.

To select food establishments and food handlers, a simple random sampling technique was used. In each institution, four food handlers were interviewed. After adaptation from similar literature [ 12 , 19 , 20 , 21 ], the questionnaire was first prepared in English and translated to local language Amharic version. The pre-test was performed on 5% food handlers out of the study area before actual data collection. Then, correction and modification were undertaken based on the gaps identified during the pre-test. Reliability of the questionnaire was also evaluated. The information was gathered via a face-to-face interview using the questionnaire’s Amharic version. Four Environmental Health Officers have been engaged as data collectors and the principal investigator was involved as a supervisor. Food safety practice was the dependent variable in this research. Socio-demographic variables and behavioural factors were the independent variables. Food handling practice: food handlers were asked seventeen questions and those who scored less than or equal to the mean value were considered as having poor practice and those who scored greater than the mean value were considered as having good practice [ 19 , 21 ]. Knowledge: Respondents were asked ten questions and those who scored less than or equal to the mean value were considered as having a poor knowledge [ 12 , 22 ].

Consistency and completeness of data were verified during collection, entry and analysis. Data were entered and coded into version 7.0.0 of Epi Info and exported for evaluation to version 22 of SPSS. The data were analysed using descriptive (frequency and proportion), bivariate, and multivariable regression analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.25 during bivariate analysis were included in multivariable regression to assess the independent effect after controlling other variables [ 23 ].

We did Hosmer and Lemeshow test to check the model fitness. SPSS Cronbach’s Alpha test result for practice questionnaire was 0.83. Finally, 95% confidence level, AOR and p-value less than 0.05 were considered for determining statistically significant variables.

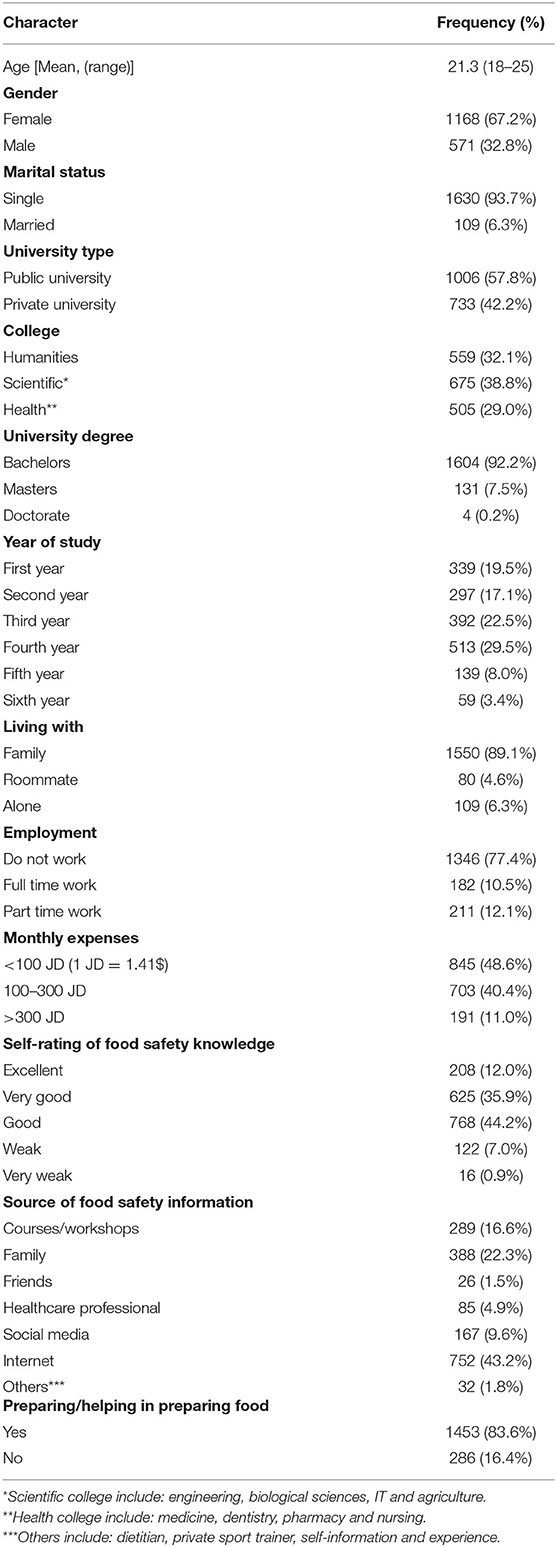

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

Of the three hundred eighty-four food handlers, 338 (88%) were females, 300 (78.1%) were unmarried; and 318 (82.8%) had an income of 500–1000 Ethiopian birr (28 ETB = 1 USD) (Table 1 ).

Knowledge of food handlers regarding the cause of food-borne disease, mode of transmission and way of food contamination

Three hundred sixteen (82.29%) of food handlers stated that food-borne diseases are caused by germs. More than half 199 (51.8%) of food handlers found this information from health center about food safety practices (Table 2 ).

Food handling practice of food handlers in food and drinking establishments

More than half of (51.5%) food handlers use hair net during food preparation. One hundred ninety (49.5%) of food handlers did not attend routine medical checkups. About 37% of the respondents were not wearing a uniform during handling and preparation of food (Table 3 ).

Factors associated with food safety practices

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that marital status, food safety training, routine medical checkup, supervision by health professionals and knowledge were statistically associated variables with food safety practices.

Single food handlers were 64.0% less likely to practice food safety than the single food handlers (AOR: 0.36, 95% CI 0.05, 0.85). Food handlers supervised by health professionals were 4.10 times more likely to practice good food safety than non-supervised (AOR: 4.10, 95% CI 1.71, 5.27). Knowledgeable food handlers were 2.92 times more likely to practices good food safety than non-knowledgeable (AOR: 2.92, 95% CI 1.38, 4.12). Trained food handers were 4.01 times more likely to have good food handling practice than non-trained food handlers (AOR: 4.01, 95% CI 2.71, 9.77). Food handers followed routine medical checkup had 8.80 times more likely to have good food handling practice than not- followed food handlers (AOR: 8.80, 95% CI 5.04, 15.36) (Table 3 ).

One hundred eighty-eight (49.0%) food handlers had good food safety practice. This finding is lower than the findings of studies in Bahir Dar (67.6%) [ 24 ], Arba Minch (67.4%) [ 21 ] and in Dubai (81.74%) [ 17 ]. While the finding was close with studies in Dangila town (52.5%), Addis Ababa (52.3%), Imo State, Nigeria (50%) and Turkey (48.4%) [ 6 , 19 , 25 , 26 ], respectively. However, it is higher than the studies done in Gondar town (22.1%) [ 5 ], South-Western Nigeria (19.0%) [ 27 ], Ogun, Nigeria (31.5%) [ 19 ]. These variations might be due to the difference in the study design, variation in training, and the provision of food hygiene and safety inputs. About 109 (28.4%) of the food handlers were certified in food safety training. This result is higher as compared with findings from Bahir Dar (21.8%) and Mekelle (15.7%) [ 12 , 28 ]. Food handler training is seen as one strategy whereby food safety practice can be increased, offering long-term benefits to the food establishments [ 29 ]. This finding is supported with studies conducted India [ 10 ], Nigeria [ 30 ], Ghana [ 31 ] and Dubai [ 32 ]. The number of food handlers who recieved food safety training in the current study is higher than with findings from Bahir Dar (21.8%), and Mekelle (5.4%) [ 12 , 28 ]. Food handlers who received training would have a better understanding of safe food handling practice as they might get professional advice during training. Training could enhance food handlers overall performance in safe food handling practice [ 21 ]. In this study, food handlers who got safety training had higher odds of good food safety practice. This might be due to trained food handlers gain good awareness through training. This supported with other similar study done in Sarawak [ 33 ]. Training programs are important for improving the knowledge of food handlers [ 34 ]. Food safety practice was also positively associated with the level of knowledge. The probability of having a good food safety practice among participants with good level of knowledge was 2.39 times higher with compared to those with a poor level knowledge (AOR = 2.39, 95% CI 1.38, 4.12). Food handlers are expected to have substantial knowledge and skills for handling foods hygienically [ 12 ]. This might be due to those food handlers who had a good level knowledge might have a higher chance of good food handling practice. This finding was supported studies conducted in Gondar town, and Malaysia [ 5 , 15 ]. Marital status was another significantly associated factor with food safety practices. Single food handlers had lower probability of good food safety practices compared with divorced handlers. This is supported with the study done in Gondar town and Dangila town [ 19 ].

Food safety practice was significantly associated with supervision by health professionals. The probability of having good food safety practice was higher among food handlers supervised by health professionals as compared with non-supervised. This finding was supported by the study conducted in Arba Minch [ 21 ]. This might be due to supervisors give advice for food handlers, the owners and to the managers. A routine medical checkup was also another factor significantly associated with good food handling practice. The probability of having good food safety practice among food handlers engaged with routine medical checkup was higher than food handlers not engaged in routine medical checkup. This could be the health care workers gave advice for food handlers during examination. This finding is in line with studies conducted in Arba Minch and Dessie towns [ 20 , 21 ]. This study revealed that there was poor food handling practice among food handlers. Marital status, food safety training, supervision by health professionals, routine medical checkup, and level of knowledge of food handlers were significantly associated with good food handling practice. Owners, managers and local health professionals should enhance the level of knowledge of food handlers, provide food hygiene, safety training, undertake periodic supervision, and routine medical checkup.

Limitations

This study was not without limitations. Some of the limitations include inherent weakness of cross-sectional study to establish a cause–effect relationship, social desirability bias and recall bias.

Availability of data and materials

We will make data available upon request the primary author.

Abbreviations

World Health Organization

adjusted odds ratio

confidence interval

crude odds ratio

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Ethiopian Birr

Institutional Review Board

Osaili TM, Al-Nabulsi AA, Krasneh HDA. Food safety knowledge among food service staff at the universities in Jordan. Food Control. 2018;89:167–76.

Article Google Scholar

Smigic N, Djekic I, Martins ML, Rocha A, Sidiropoulou N, Kalogianni EP. The level of food safety knowledge in food establishments in three European countries. Food Control. 2016;63:187–94.

Adesokan HK, Akinseye VO, Adesokan GA. Food safety training is associated with improved knowledge and behaviours among foodservice establishments’ workers. Int J Food Sci. 2015;2015:328761.

Osimani A, Aquilanti L, Tavoletti S, Clementi F. Evaluation of the HACCP system in a university canteen: microbiological monitoring and internal auditing as verification tools. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(4):1572–85.

Gizaw Z, Gebrehiwot M, Teka Z. Food safety practice and associated factors of food handlers working in substandard food establishments in Gondar Town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2013/14. Int J Food Sci Nutr Diet. 2014;3(7):138–46.

Google Scholar

Meleko A, Henok A, Tefera W, Lamaro T. Assessment of the sanitary conditions of catering establishments and food safety knowledge and practices of food handlers in Addis Ababa University Students’ Cafeteria. Science. 2015;3(5):733–43.

Fasanmi O, Makinde G, Popoola M, Fasina O, Matere J, Ogundare S. Potential risk factors associated with carcass contamination in slaughterhouse operations and hygiene in Oyo state, Nigeria. Int J Livestock Prod. 2018;9(8):211–20.

World Health Organization. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference grou. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. p. 2007–15.

Girma G. Prevalence, Antibiogram and Growth Potential of Salmonella and Shigella in Ethiopia: implications for Public Health: a Review. Res J Microbiol. 2015;10(7):288.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ali AI, Immanuel G. Assessment of hygienic practices and microbiological quality of food in an institutional food service establishment. J Food Process Technol. 2017;8:8.

Manes MR, Liu LC, Dworkin MS. Baseline knowledge survey of restaurant food handlers in suburban Chicago: do restaurant food handlers know what they need to know to keep consumers safe? J Environ Health. 2013;76(1):18–27.

PubMed Google Scholar

Kibret M, Abera B. The sanitary conditions of food service establishments and food safety knowledge and practices of food handlers in Bahir Dar town. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22(1):27–35.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Al-Shabib NA, Mosilhey SH, Husain FM. Cross-sectional study on food safety knowledge, attitude and practices of male food handlers employed in restaurants of King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. Food Control. 2016;59:212–7.

Wambui J, Karuri E, Lamuka P, Matofari J. Good hygiene practices among meat handlers in small and medium enterprise slaughterhouses in Kenya. Food Control. 2017;81:34–9.

Asmawi UMM, Norehan AA, Salikin K, Rosdi NAS, Munir NATA, Basri NBM. An assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices in food safety among food handlers engaged in food courts. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2018;6(2):346–53.

Okonko I, Adejoye O, Ogun A, Ogunjobi A, Nkang A, Adebayo-Tayo B. Hazards analysis critical control points (HACCP) and microbiology qualities of sea-foods as affected by handler’s hygience in Ibadan and Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Food Sci (ACFS). 2009;3(2):35–50.

Kumie A, Mezene A, Amsalu A, Tizazu A, Bikila B. The sanitary condition of food and drink establishment in Awash-Sebat Kilo town, Afar Region, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Develop. 2006;20:3.

Mendedo EK, Berhane Y, Haile BT. Factors associated with sanitary conditions of food and drinking establishments in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28(1):237.

Tessema AG, Gelaye KA, Chercos DH. Factors affecting food handling Practices among food handlers of Dangila town food and drink establishments, North West Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):571.

Adane M, Teka B, Gismu Y, Halefom G, Ademe M. Food hygiene and safety measures among food handlers in street food shops and food establishments of Dessie town, Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0196919.

Legesse D, Tilahun M, Agedew E, Haftu D. Food handling practices and associated factors among food handlers in arba minch town public food establishments in Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale). 2017;7(302):2161–5.

Nee SO, Sani NA. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) among food handlers at residential colleges and canteen regarding food safety. Sains Malaysiana. 2011;40(4):403–10.

Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–37.

Derso T, Tariku A, Ambaw F, Alemenhew M, Biks GA, Nega A. Socio-demographic factors and availability of piped fountains affect food hygiene practice of food handlers in Bahir Dar Town, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):628.

Iwu AC, Uwakwe KA, Duru CB, Diwe KC, Chineke HN, Merenu IA, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices of food hygiene among food vendors in Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;5:11–25.

Baş M, Ersun AŞ, Kıvanç G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers’ in food businesses in Turkey. Food Control. 2006;17(4):317–22.

Faremi FA, Olatubi MI, Nnabuife GC. Food safety and hygiene practices among food vendors in a Tertiary Educational Institution in South Western Nigeria. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2018;8:59–70.

Lalit I, Brkti G, Dejen Y. Magnitude of hygienic practices and its associated factors of food handlers working in selected food and drinking establishments in Mekelle town, northern Ethiopia. Int Food Res J. 2015;22(6):914.

Gaungoo Y, Jeewon R. Effectiveness of training among food handlers: a review on the Mauritian Framework. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2013;1(1):01–9.

Afolaranmi TO, Hassan ZI, Misari Z, Dan EE, Judith O, Kubiat NN, et al. Food safety and hygiene practices among food Vendorsin Tertiary Hospitals Inplateau State Nigeria. World J Res Rev. 2013;25:1.

Annor GA, Baiden EA. Evaluation of food hygiene knowledge attitudes and practices of food handlers in food businesses in Accra, Ghana. Food Nutr Sci. 2011;2(08):830.

Al Suwaidi A, Hussein H, Al Faisal W, El Sawaf E, Wasfy A. Hygienic practices among food handlers in Dubai. Int J Prevent Med Res. 2012;1(3):101–8.

Rahman MM, Arif MT, Bakar K, Talib Z. Food safety knowledge, attitude and hygiene practices among the street food vendors in Northern Kuching City, Sarawak. Borneo Sci. 2016;31:94–103.

Seaman P, Eves A. Perceptions of hygiene training amongst food handlers, managers and training providers—a qualitative study. Food Control. 2010;21(7):1037–41.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all study participants, data collectors, food establishment owners and the University of Gondar for their willingness and support to the success of this study.

The authors of this study have received no funds from anywhere but the University of Gondar has covered questionnaire duplication fees.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Jember Azanaw, Mulat Gebrehiwot & Henok Dagne

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JA took part in the research development proposal, data collection tools, entered data into Epi-info, analyse and interpret the data, and write various parts of the research report. MG and HD advised from the starting to the end. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jember Azanaw .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

We got ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB/47/2010) of the Institution of Public Health, University of Gondar. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participants. The consent of the city administrator, the manager of the food and drinking establishments, and the respondents took part willingly. We kept the confidentiality of the respondents and for the food and drinking establishments by asking the participants not to write their names on the questionnaires and codes to conceal the identity of the food and drinking establishments. We used the collected data for this research purpose only. We forwarded health educations to the study participants by data collectors and the principal investigator at the end of the data collection.

Consent to publication

This manuscript does not contain an individual person and institutional data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.