Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a literary analysis essay | A step-by-step guide

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on January 30, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 14, 2023.

Literary analysis means closely studying a text, interpreting its meanings, and exploring why the author made certain choices. It can be applied to novels, short stories, plays, poems, or any other form of literary writing.

A literary analysis essay is not a rhetorical analysis , nor is it just a summary of the plot or a book review. Instead, it is a type of argumentative essay where you need to analyze elements such as the language, perspective, and structure of the text, and explain how the author uses literary devices to create effects and convey ideas.

Before beginning a literary analysis essay, it’s essential to carefully read the text and c ome up with a thesis statement to keep your essay focused. As you write, follow the standard structure of an academic essay :

- An introduction that tells the reader what your essay will focus on.

- A main body, divided into paragraphs , that builds an argument using evidence from the text.

- A conclusion that clearly states the main point that you have shown with your analysis.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: reading the text and identifying literary devices, step 2: coming up with a thesis, step 3: writing a title and introduction, step 4: writing the body of the essay, step 5: writing a conclusion, other interesting articles.

The first step is to carefully read the text(s) and take initial notes. As you read, pay attention to the things that are most intriguing, surprising, or even confusing in the writing—these are things you can dig into in your analysis.

Your goal in literary analysis is not simply to explain the events described in the text, but to analyze the writing itself and discuss how the text works on a deeper level. Primarily, you’re looking out for literary devices —textual elements that writers use to convey meaning and create effects. If you’re comparing and contrasting multiple texts, you can also look for connections between different texts.

To get started with your analysis, there are several key areas that you can focus on. As you analyze each aspect of the text, try to think about how they all relate to each other. You can use highlights or notes to keep track of important passages and quotes.

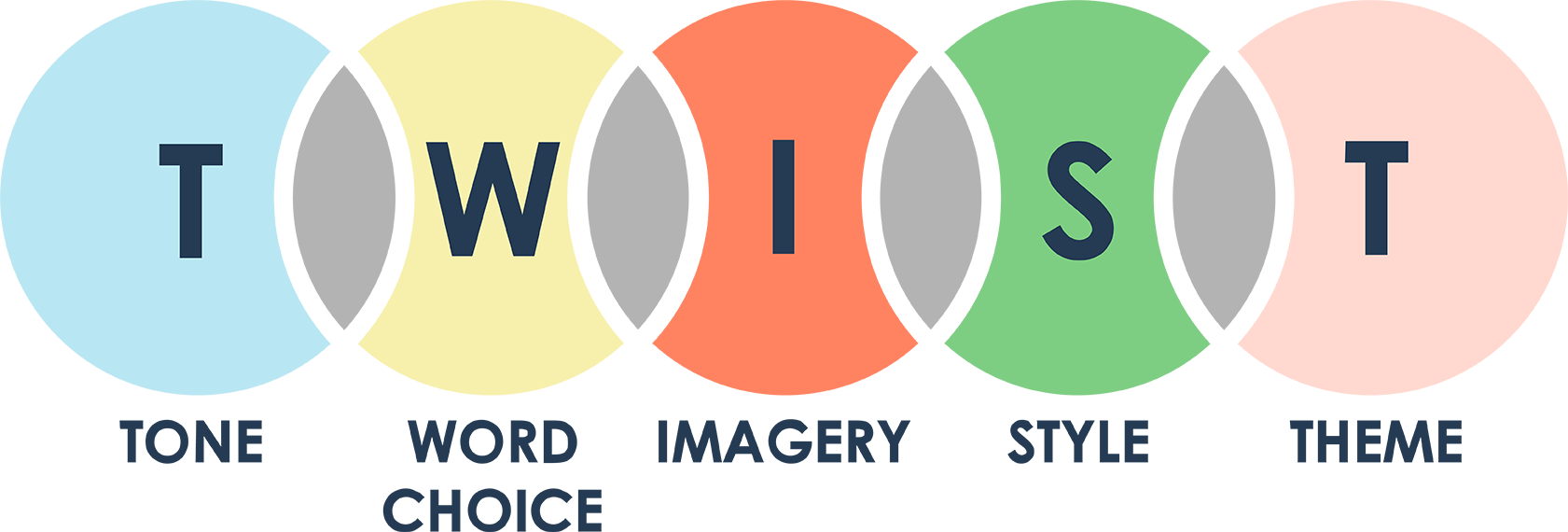

Language choices

Consider what style of language the author uses. Are the sentences short and simple or more complex and poetic?

What word choices stand out as interesting or unusual? Are words used figuratively to mean something other than their literal definition? Figurative language includes things like metaphor (e.g. “her eyes were oceans”) and simile (e.g. “her eyes were like oceans”).

Also keep an eye out for imagery in the text—recurring images that create a certain atmosphere or symbolize something important. Remember that language is used in literary texts to say more than it means on the surface.

Narrative voice

Ask yourself:

- Who is telling the story?

- How are they telling it?

Is it a first-person narrator (“I”) who is personally involved in the story, or a third-person narrator who tells us about the characters from a distance?

Consider the narrator’s perspective . Is the narrator omniscient (where they know everything about all the characters and events), or do they only have partial knowledge? Are they an unreliable narrator who we are not supposed to take at face value? Authors often hint that their narrator might be giving us a distorted or dishonest version of events.

The tone of the text is also worth considering. Is the story intended to be comic, tragic, or something else? Are usually serious topics treated as funny, or vice versa ? Is the story realistic or fantastical (or somewhere in between)?

Consider how the text is structured, and how the structure relates to the story being told.

- Novels are often divided into chapters and parts.

- Poems are divided into lines, stanzas, and sometime cantos.

- Plays are divided into scenes and acts.

Think about why the author chose to divide the different parts of the text in the way they did.

There are also less formal structural elements to take into account. Does the story unfold in chronological order, or does it jump back and forth in time? Does it begin in medias res —in the middle of the action? Does the plot advance towards a clearly defined climax?

With poetry, consider how the rhyme and meter shape your understanding of the text and your impression of the tone. Try reading the poem aloud to get a sense of this.

In a play, you might consider how relationships between characters are built up through different scenes, and how the setting relates to the action. Watch out for dramatic irony , where the audience knows some detail that the characters don’t, creating a double meaning in their words, thoughts, or actions.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Your thesis in a literary analysis essay is the point you want to make about the text. It’s the core argument that gives your essay direction and prevents it from just being a collection of random observations about a text.

If you’re given a prompt for your essay, your thesis must answer or relate to the prompt. For example:

Essay question example

Is Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” a religious parable?

Your thesis statement should be an answer to this question—not a simple yes or no, but a statement of why this is or isn’t the case:

Thesis statement example

Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law” is not a religious parable, but a story about bureaucratic alienation.

Sometimes you’ll be given freedom to choose your own topic; in this case, you’ll have to come up with an original thesis. Consider what stood out to you in the text; ask yourself questions about the elements that interested you, and consider how you might answer them.

Your thesis should be something arguable—that is, something that you think is true about the text, but which is not a simple matter of fact. It must be complex enough to develop through evidence and arguments across the course of your essay.

Say you’re analyzing the novel Frankenstein . You could start by asking yourself:

Your initial answer might be a surface-level description:

The character Frankenstein is portrayed negatively in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

However, this statement is too simple to be an interesting thesis. After reading the text and analyzing its narrative voice and structure, you can develop the answer into a more nuanced and arguable thesis statement:

Mary Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as.

Remember that you can revise your thesis statement throughout the writing process , so it doesn’t need to be perfectly formulated at this stage. The aim is to keep you focused as you analyze the text.

Finding textual evidence

To support your thesis statement, your essay will build an argument using textual evidence —specific parts of the text that demonstrate your point. This evidence is quoted and analyzed throughout your essay to explain your argument to the reader.

It can be useful to comb through the text in search of relevant quotations before you start writing. You might not end up using everything you find, and you may have to return to the text for more evidence as you write, but collecting textual evidence from the beginning will help you to structure your arguments and assess whether they’re convincing.

To start your literary analysis paper, you’ll need two things: a good title, and an introduction.

Your title should clearly indicate what your analysis will focus on. It usually contains the name of the author and text(s) you’re analyzing. Keep it as concise and engaging as possible.

A common approach to the title is to use a relevant quote from the text, followed by a colon and then the rest of your title.

If you struggle to come up with a good title at first, don’t worry—this will be easier once you’ve begun writing the essay and have a better sense of your arguments.

“Fearful symmetry” : The violence of creation in William Blake’s “The Tyger”

The introduction

The essay introduction provides a quick overview of where your argument is going. It should include your thesis statement and a summary of the essay’s structure.

A typical structure for an introduction is to begin with a general statement about the text and author, using this to lead into your thesis statement. You might refer to a commonly held idea about the text and show how your thesis will contradict it, or zoom in on a particular device you intend to focus on.

Then you can end with a brief indication of what’s coming up in the main body of the essay. This is called signposting. It will be more elaborate in longer essays, but in a short five-paragraph essay structure, it shouldn’t be more than one sentence.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is often read as a crude cautionary tale about the dangers of scientific advancement unrestrained by ethical considerations. In this reading, protagonist Victor Frankenstein is a stable representation of the callous ambition of modern science throughout the novel. This essay, however, argues that far from providing a stable image of the character, Shelley uses shifting narrative perspectives to portray Frankenstein in an increasingly negative light as the novel goes on. While he initially appears to be a naive but sympathetic idealist, after the creature’s narrative Frankenstein begins to resemble—even in his own telling—the thoughtlessly cruel figure the creature represents him as. This essay begins by exploring the positive portrayal of Frankenstein in the first volume, then moves on to the creature’s perception of him, and finally discusses the third volume’s narrative shift toward viewing Frankenstein as the creature views him.

Some students prefer to write the introduction later in the process, and it’s not a bad idea. After all, you’ll have a clearer idea of the overall shape of your arguments once you’ve begun writing them!

If you do write the introduction first, you should still return to it later to make sure it lines up with what you ended up writing, and edit as necessary.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them.

Paragraph structure

A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs : the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Each paragraph in the main body should focus on one topic. In the five-paragraph model, try to divide your argument into three main areas of analysis, all linked to your thesis. Don’t try to include everything you can think of to say about the text—only analysis that drives your argument.

In longer essays, the same principle applies on a broader scale. For example, you might have two or three sections in your main body, each with multiple paragraphs. Within these sections, you still want to begin new paragraphs at logical moments—a turn in the argument or the introduction of a new idea.

Robert’s first encounter with Gil-Martin suggests something of his sinister power. Robert feels “a sort of invisible power that drew me towards him.” He identifies the moment of their meeting as “the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it” (p. 89). Gil-Martin’s “invisible power” seems to be at work even at this distance from the moment described; before continuing the story, Robert feels compelled to anticipate at length what readers will make of his narrative after his approaching death. With this interjection, Hogg emphasizes the fatal influence Gil-Martin exercises from his first appearance.

Topic sentences

To keep your points focused, it’s important to use a topic sentence at the beginning of each paragraph.

A good topic sentence allows a reader to see at a glance what the paragraph is about. It can introduce a new line of argument and connect or contrast it with the previous paragraph. Transition words like “however” or “moreover” are useful for creating smooth transitions:

… The story’s focus, therefore, is not upon the divine revelation that may be waiting beyond the door, but upon the mundane process of aging undergone by the man as he waits.

Nevertheless, the “radiance” that appears to stream from the door is typically treated as religious symbolism.

This topic sentence signals that the paragraph will address the question of religious symbolism, while the linking word “nevertheless” points out a contrast with the previous paragraph’s conclusion.

Using textual evidence

A key part of literary analysis is backing up your arguments with relevant evidence from the text. This involves introducing quotes from the text and explaining their significance to your point.

It’s important to contextualize quotes and explain why you’re using them; they should be properly introduced and analyzed, not treated as self-explanatory:

It isn’t always necessary to use a quote. Quoting is useful when you’re discussing the author’s language, but sometimes you’ll have to refer to plot points or structural elements that can’t be captured in a short quote.

In these cases, it’s more appropriate to paraphrase or summarize parts of the text—that is, to describe the relevant part in your own words:

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The conclusion of your analysis shouldn’t introduce any new quotations or arguments. Instead, it’s about wrapping up the essay. Here, you summarize your key points and try to emphasize their significance to the reader.

A good way to approach this is to briefly summarize your key arguments, and then stress the conclusion they’ve led you to, highlighting the new perspective your thesis provides on the text as a whole:

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, August 14). How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/literary-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write a narrative essay | example & tips, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

How to Write a Novel Study: A Complete Guide for Students & Teachers

What Is a Novel Study?

A novel study is essentially the process of reading and studying a novel closely. There are three formats the novel study can follow, namely:

- The whole-class format

- The small group format

- The individual format

Each of these formats comes with its own advantages and disadvantages. Which you will use in your classroom will depend on several variables, including the novel study’s purpose, class demographics, time constraints, etc.

This article will look at activities you can use with your students in a novel study. Though the focus will primarily be on the whole-class format, the activities outlined below can easily be adapted for small-group and individual novel studies.

But first, let’s take a look at some of the many considerable benefits of the novel study.

What Are the Benefits of a Novel Study?

The benefits of this type of learning are many and varied. Essentially, the novel itself serves as a jumping-off point for a diverse range of learning experiences that can benefit students’ learning in many ways.

Here are just three of these benefits.

1. Encourages a Love of Reading

As teachers, we are well aware of how much literature can enrich our lives. However, for many of our students, reading is a chore in and of itself and is to be avoided whenever possible.

The novel study sets aside time in class to focus on reading in an engaging manner that not only encourages students to enjoy reading but helps them develop the tools and strategies required to get the most out of the books they read.

2. Builds a Wider Knowledge Base

Sharing books in this manner creates opportunities for students to become exposed to experiences far beyond those of their daily lives. Not only will they enter new and unfamiliar worlds through the portal of fiction, but they’ll also be exposed to the experiences and opinions of other students in the class. These experiences and opinions may differ markedly from their own.

It will also widen the student’s knowledge and understanding of text structure, vocabulary, punctuation, and grammar . Novel studies are an extremely effective way to practice comprehension skills and improve critical thinking.

3. Boosts Class Cohesion

Whole class novel studies help your students to flex their muscles of cooperation as they work their way through a text together. They also help students to understand each other, take on board the opinions of others, and learn to defend their own thoughts and opinions.

While reading is often viewed as a solitary activity, reading in this manner can become a social experience that helps students to bond as a class.

What Should I Do in a Novel Study?

There are many different ways to undertake a novel study in your classroom.

For example, some teachers like to read the entire novel to their students first before going back through it as a class, focusing then on student interactions with the text.

Other teachers like to weave guided reading activities into their novel study sessions. However, this often works better with smaller groups where students can be grouped according to ability and assigned texts accordingly.

What shape a novel study takes in your classroom will depend on your student demographics and learning objectives. However, we can helpfully divide the various activities into pre-reading, during-reading, and post-reading. You can select those that suit your situation best.

Now, let’s look at some of these.

How to Start a Novel Study

Your novel study begins even before the first page is read. The activities below will help students tune in to the book they are about to read.

This is a crucial stage of the novel study, especially if the book is of historical significance or deals with historical events and where some background knowledge may be essential for understanding the novel.

Prereading Activities

- Examine the Covers

Before opening the book, have students examine the covers closely, both front and back. What can they tell about the book before opening it based on:

- The cover illustration?

- The author’s name?

- The blurb on the back?

It’s useful to do this as a whole-class discussion to allow for sharing ideas. Ask questions to encourage reflection and get students to make predictions about the novel based on their answers and observations. For example:

- What information does the cover provide?

- Does the cover illustration intrigue you? Why?

- Does this novel remind you of any other books you’ve read? Why?

- Do you recognize the author’s name? What else have they written?

It can be pretty surprising just how much information you can glean from a novel’s covers.

- Generate a List of Questions

Once students have had a good chance to examine the novel’s covers in small groups, get them to generate questions they have about the book and its contents.

These questions may be based on their expectations in the first activity, but they may also be general questions related to common elements in all novels. For example:

- Where is the story set?

- When is it set?

- Who is the main character/protagonist in the novel?

- Who is the antagonist?

- What is the nature of the central conflict?

- What happens in the climax? Resolution? Etc.

While most of these questions will not be answered entirely until the students have read the novel, asking these questions will get the students thinking about the novel’s structure from the outset. This will be extremely useful for later activities.

- Take a Peek Inside

Now, it’s time to open the book to look closer. Task students to go ‘finger-walking’ through the book and, without reading the novel, explore the book’s pages for more surface information. For example:

- When was the book published? Why is this significant?

- Are there any illustrations inside? What impression do they make?

- Does the book have chapters? What do the chapter titles tell us about the story?

- Open a random page and read it. What language register does the writer use? What point of view is employed?

Encouraging students to work in small groups can be helpful here. You can also ask prompting questions to help students maintain focus during this activity.

During Reading Activities

The whole-class format is perhaps the most widely used in the classroom context. In this format, each student will usually have a copy of the text and follow along while the teacher or another student reads.

The reading will pause at intervals to allow the students to engage in discussion, ask questions, or complete various activities supporting learning goals related to the text they have been reading.

In general, novel study activities will focus on:

- Building vocabulary

- Improving comprehension

- Making text-to-text connections

- Making text-to-self connections

- Making text-to-world connections

In the following section, we’ll look at each of these in turn.

Reading is a fantastic way to build vocabulary; when your students encounter new vocabulary while reading, encourage them to employ several strategies to decipher the word before resorting to their dictionaries.

Firstly, what clues to the word’s meaning can the students find in the word itself? Do students recognize the word’s root or affixes? Does it resemble any other words they already know the meaning of?

Secondly, students should look at the context in which the word is used, not just in the sentence itself but also in the preceding and following paragraphs. What clues can the students find to the word’s meaning?

After analyzing the parts of the word and exhausting context clues, students can look up the word in dictionaries. However, they will still need to do some legwork to make the new word stick. Some valuable ways of committing a new word to memory include:

- Sketching a visual interpretation of the word

- Making a list of synonyms of the word using a thesaurus to assist

- Apply the target words in personal contexts (in conversation/writing sentences)

- Reading Comprehension

Vocabulary is only one aspect of comprehension. Novel studies afford students a valuable opportunity to develop their deep comprehension abilities.

Beyond just understanding the meaning of the words in a novel, students will work on their understanding of skills such as:

- Identifying the central idea/themes

- Examining character/plot development

- Distinguishing between fact and opinion

- Summarizing

- Inferencing

- Comparing and contrasting

While activities for teaching some of the more basic comprehension skills may be more self-evident, activities for teaching higher-level skills, such as inferencing, may require a bit more thought and planning.

We can define inference as the process of deriving a conclusion based on the available evidence in the text combined with the student’s background knowledge and experience.

Put simply, inference involves reading between the lines.

Inference = What is in the text + What I already know

To encourage students to use inference while completing a novel study, ask questions building on prompts such as:

- Why do you think…

- What do you think would happen if…

- What can you conclude about x based on what you’ve read?

- How does the writer feel about…

- How do you think x feels?

If you want to learn more about teaching inference in the classroom, check out our thorough article on the topic here .

- Making Connections

While vocabulary building and developing reading comprehension skills are a big part of what novel studies are all about, this type of reading lends itself to a deeper exploration of the power of the written word.

Too often, our students read prescribed texts without ever making any personal or profound connections to the material they read. Students can better understand what they are reading by exploring ways of connecting to a novel. There are three main types of connections we can explore:

- Text-to-self connections

- Text-to-text connections

- Text-to-world connections

Let’s look at how students can make each type of connection in a novel study.

Text-to-Self

This is all about the student making a personal connection and responding to the text as an individual. Essentially, this type of connection is about encouraging the students to share their thoughts and feelings on various aspects of the novel. This sharing can take the form of oral contributions to class discussions and debates or in the form of a written response.

Either way, question prompts are a great way to kick things off. Here are some examples to get the ball rolling.

- What does this incident remind you of in your own life?

- Which character do you identify with the most?

- Have you ever been in a similar situation? What happened?

- What would you do in this situation?

Text-to-Text

These connections are all about the student linking the novel they are studying to other texts they have read or seen. This could include other novels, comics, nonfiction books, websites, and poems.

Here are some useful prompts to encourage your students to make text-to-text connections.

- Have you ever read anything like this before?

- How is this text similar to/different from other texts you’ve looked at?

- What other fictional character does the hero of this novel remind you of?

Text-to-World

Making a text-to-world connection requires students to think about the novel in terms of the wider world. Here, students forge links with the broader culture and current affairs. Text-to-world connections will frequently require students to tie the novel into other areas of learning, such as social studies and the sciences.

Here are a few helpful text-to-world prompts.

- How do the events described in the novel relate to real-world events?

- What issues explored in the novel are pertinent in today’s world?

- How does the world described in the novel relate to the world we live in now?

Post-Reading Activities

The number of possible activities you can do to complete a novel is almost endless. Which activities you choose will depend on what aspect of the novel and/or objectives you are trying to teach. Here are just a few popular tasks students regularly complete after they finish reading a novel.

- Create a timeline of events.

- Graph the plot .

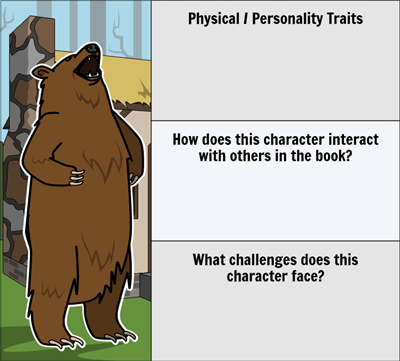

- Write a character profile.

- Design an alternative book cover/blurb.

- Write a summary of the novel.

- Write an alternative ending.

- Have a formal debate based on themes or issues explored in the novel.

- Write a book review.

Well, that’s enough to start a novel study in your classroom. However, if you’d like to read more on reading comprehension strategies you can employ in your novel studies, check out our depth article on the topic here .

The flexibility of the novel study format lends itself well to almost any age group; just be sure to choose a text that matches the general reading ability of your class. For older kids, you may even want to involve them in deciding what text to study.

However you decide to choose your novel, just be sure to read the text thoroughly in advance to stay one step ahead of your students – and don’t forget to have fun with it!

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Members Newsfeed

A Complete Guide to Writing a Novel Study for Students and Teachers

Introduction

Writing a novel study is a significant part of a student’s academic journey, and it tests their comprehension, analytical skills, and ability to communicate. Teachers also come across challenges when planning and reviewing the novel studies to ensure the students get the most out of their learning experience. This guide aims to provide both students and teachers with useful tips and insights into writing an effective novel study.

I. For Students – How to Write a Novel Study

1. Choose your book thoughtfully: Select a book that you’re genuinely interested in or curious about. It helps if the author has created multifaceted characters, compelling plotlines, and engaging themes.

2. Read thoroughly: Prioritize understanding the plot, setting, characters, themes, style, and symbolic motifs of the book.

3. Take notes while reading: Jot down quotes or scenes that capture your attention and might be useful to reference when discussing themes or character development.

4. Analyze the story: As you read, think critically about how elements of the story work together to produce meaning. Analyze the characters, relationships between them, key events in the plot, and various symbols used by the author.

5. Develop an argument or central theme: Craft a thesis statement or central idea that aligns with your observations of the novel. This will act as a foundation for your essay.

6. Create an outline: Map out your essay’s structure by organizing related ideas into a clear hierarchy of main points and supporting examples.

7. Draft your work: Write your essay based on your outline.

8. Revise and edit: Proofread your paper after taking a break from it to look for mistakes in content or style. Consider asking someone else to review it as well for additional feedback.

II. For Teachers – Guiding Your Students in Writing Novel Studies

1. Help students choose their books: Encourage students to go beyond their comfort zones and read books that challenge them. Provide several suggestions covering a wide range of styles, themes, and genres.

2. Establish clear objectives: Determine your expectations for the novel study. Specify requirements about the format, length, and whether the essay should focus on a specific aspect like theme, characters, or plot.

3. Encourage active reading: Teach students the importance of annotating texts, noticing patterns, and asking questions about the story.

4. Facilitate discussions: Debate ideas as a class or in small groups to help students refine their arguments and reinforce their understanding of critical literary concepts.

5. Provide templates or guidelines: Offer examples of novel studies or essay outlines to help students understand how to effectively structure their work.

6. Offer writing workshops: Guide your students in refining research techniques, brainstorming ideas, developing thesis statements, and improving writing skills through regular workshops.

7. Give constructive feedback: Review drafts and provide detailed feedback on content, organization, grammar, clarity, and style.

8.Encourage peer review: Develop a learning environment in which your students can help each other by providing feedback on their novel studies before submission.

A successful novel study requires diligent reading combined with thoughtful critical analysis. By following these practical tips and guidelines for both students and teachers, mastering the art of writing insightful novel studies can become a reality for every student pursuing literary excellence.

Related Articles

The art of informative writing is a fundamental component of educational curriculum…

As parents, educators, and mentors, it’s essential to introduce children to the…

Editing can often be the less glamorous side of writing for students,…

Pedagogue is a social media network where educators can learn and grow. It's a safe space where they can share advice, strategies, tools, hacks, resources, etc., and work together to improve their teaching skills and the academic performance of the students in their charge.

If you want to collaborate with educators from around the globe, facilitate remote learning, etc., sign up for a free account today and start making connections.

Pedagogue is Free Now, and Free Forever!

- New? Start Here

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Registration

Don't you have an account? Register Now! it's really simple and you can start enjoying all the benefits!

We just sent you an Email. Please Open it up to activate your account.

I allow this website to collect and store submitted data.

Supercharge your reading experience

Lifetime Readers

Customer Satisfaction

Study Guides

Plot Summaries

What’s inside a SuperSummary Study Guide?

Our Study Guides are packed with all the information you need to get the most out of the titles you read.

Refresh your memory of key events and big ideas.

Unlock underlying meaning through expert insights.

Follow character arcs from tragedy to triumph.

Connect the dots among recurring ideas.

Appreciate the meaning behind the words.

Discover writing prompts and conversation starters.

Experience the SuperSummary difference

Download a sample Study Guide.

Jonathan Franzen

Oscar Wilde

Anna Quindlen

Kate Chopin

Analyzing literature can be hard—but SuperSummary makes it easy to unpack even the toughest titles.

Get better results

Readers turn to SuperSummary to boost their grades, create lessons more quickly, spark stronger book discussions, and more. Discover how we’re helping readers succeed .

Save hours of time

Whether you’re preparing for an assignment, a lesson plan, or a book club meeting, SuperSummary saves you hours of time preparing and sorting through inferior free products to find the content you need.

Learn from experts

SuperSummary guides are written by teachers, professors, and literature specialists with multiple years of experience. Meet our writers .

Explore with confidence

We’re so sure you’ll love our learning resources that we offer a 7-day Money-Back Guarantee .

Meet some of our talented writers and editors.

SuperSummary recruits experienced teachers and literary experts with advanced degrees to develop, write, and edit our Study Guides and Teaching Guides.

Jenn Brisendine

20-year teaching career across middle and high school English

Bachelor’s in secondary education (English & dramatic arts) and a master’s in fiction writing

Specializes in writing and editing middle-grade, young adult, and high school-level materials

Elyse Myers

10 years of experience teaching university-level literature courses and 6 years of experience as a fiction reference librarian

Doctor of Philosophy in English literature

Specializes in classic and contemporary fiction , particularly nineteenth- and twentieth-century American and British literature

Lily Beaumont

7 years of experience in curriculum and Study Guide development

Joint master’s degree in English and women’s & gender Studies

Specializes in Victorian literature and feminist theory

Trending titles

A Long Petal of the Sea

American Dirt

Conversations with Friends

Firefly Lane

George Washington Gomez

Girl, Woman, Other

Harlem Shuffle

It Ends with Us

Klara and the Sun

Project Hail Mary

State of Terror

The Christie Affair

The City We Became

The Lincoln Highway

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois

The Night Watchman

The Other Black Girl

Where the Crawdads Sing

Can’t find what you’re looking for? Suggest a title.

Real results from real customers

SuperSummary stood out.

The subscription is inexpensive and the guides provide a wealth of information.

SuperSummary has more in-depth analyses.

SuperSummary helps me a lot more than free websites.

Study Guide Collections

Get inspired and find your next read with our carefully curated Collections of titles based on common themes, topics, or audiences.

Women's Studies

Fiction with Strong Female Protagonists

Oprah's Book Club Picks

Audio Study Guides

BookTok Books

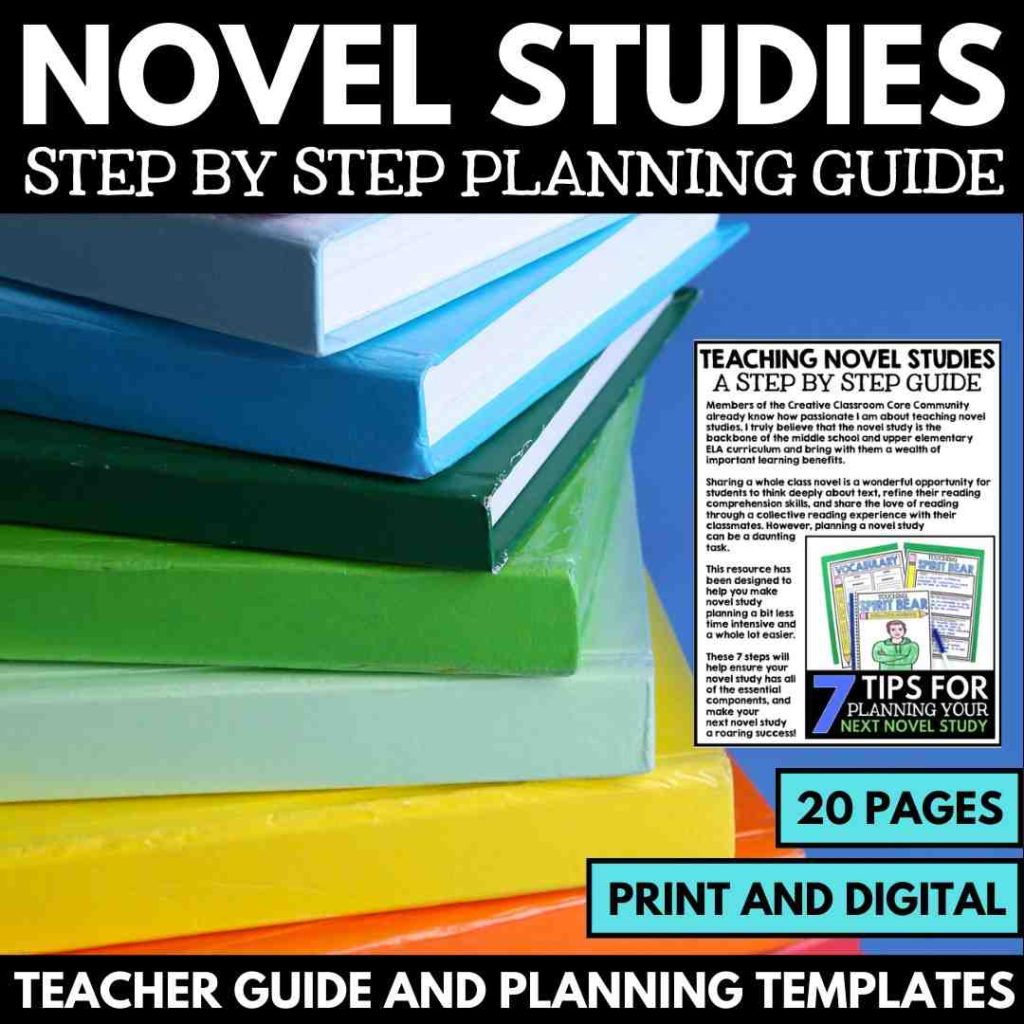

Planning a Novel Study (Without Stress)

A Step-By-Step Guide

Planning a novel study can seem like an overwhelming task. And when you’re just throwing things together (we’ve all been there), it totally can be. However, a novel study is a cornerstone in an ELA classroom. You might feel immense pressure to design a unit where students can finally let their foundational reading skills shine and even take them to the next level. Therefore, it’s imperative to create a novel study with intent and purpose. After reading this, you’ll be able to create one with a lot less stress too.

When planning a novel study for your classroom, you want to avoid planning as you go. (That’s my number one piece of advice.) Now, I’m not saying you can’t make adjustments along the way. You’ll likely find that it’s hard to make it through an entire novel without making a tweak here or there. However, having a plan will not only ease your stress but will ensure a meaningful and purpose-driven novel study for your students as well.

So, whether this is your first time planning a novel study for your students or you’re looking to clean up your process and planning, follow this step-by-step approach. Trust me; It’ll benefit both you and your students.

WHAT EXACTLY IS A NOVEL STUDY?

Let me start by clarifying what a novel study is not . A novel study does not mean simply studying a plot, and it’s more than quizzing students on what happened on a specific page of a particular book. It’s not just about who did what when. Planning and facilitating a novel study isn’t synonymous with teaching a book. Why? Teaching a novel study goes beyond the book. Instead, a novel study goes beyond the basics of reading words on a page. Now that your students have a strong foundation of phonics, fluency, and vocabulary, a novel study helps them dive into the next phase of their learning journey.

It’s teaching students how to engage with a book. It goes beyond the words on the page and helps students understand to read between the lines. A novel study helps students develop essential reading comprehension and critical thinking skills that they will continue to build upon throughout their educational journey and beyond.

A novel study is also an opportunity for students to be highly active participants in their learning experience. When done well, a novel study finds the balance between guidance and student-led analysis to develop, practice, and refine their reading comprehension and analysis skills. And perhaps one of the best potential outcomes of a novel study is creating a safe space where students can build a love and appreciation for reading. (What kind of English teacher wouldn’t want that?)

UNDERSTANDING THE BENEFITS.

Before you dive into planning your novel study, you might be wondering if it’s worth the hype. Afterall, if you’re going to take the time and effort to plan it out, you want to be sure your students will benefit. (Hint: They will.)

The purpose and benefits are going to vary from class to class, student to student. You may choose certain novels to hone in on specific skills, standards, and learning goals. The novel study might be part of a larger unit or may stand on its own. Regardless, there are many benefits to introducing a novel study to your classroom.

Teacher Benefits.

A novel study is a great way to check many boxes with one cohesive unit. For starters, novel studies provide plenty of room to address multiple learning goals and state standards within a single unit. I’ve found it’s much more enjoyable for myself and my students when learning goals flow seamlessly from one to another. Additionally, novel studies provide the perfect setting for bringing together reading and writing skills (an ELA teacher’s dream). Student Benefits.

Perhaps one of the most significant student benefits of novel study is exposure. Novels provide students a portal to different experiences and perspectives. Our experiences often shape our lives, yet student experiences can be rather limited. So, whether you’re hoping to expose them to different cultures, historical periods, or circumstances and experiences outside their own, a well-planned and executed novel study can open the door to understanding and even lay the foundation for empathy.

Similarly, students gain skills beyond the book. Students might need to collaborate on activities or practice listening to the opinions of others, helping them develop essential interpersonal skills. So, they’ll gain a sense of perspective from reading and discussing the novel. Students will have many opportunities to understand that not everyone thinks and works in the same way.

Lastly, a novel study is a great opportunity to contextualize new vocabulary. While students might be used to spelling bees and weekly vocab lists, a novel study gives them a context for learning new words. Instead of learning new words for the sake of learning new words, vocabulary is contextualized for a more meaningful and authentic understanding. To this day, I cannot hear the word disillusionment without thinking of the great tragedy of The Great Gatsby and the American experience in the 1920s.

Now that you understand what a novel study is (and isn’t) and some of its greatest benefits, let’s get to planning!

Step 1: Know Your Purpose.

It all starts with a purpose. So, you want to begin planning your novel study with an idea of where you’re going and, ultimately, taking the students. Consider asking yourself the following questions to get you thinking about the bigger picture:

- How does this novel study fit into your curriculum? Is it your approach to your next unit or a supplement to a larger unit?

- What do you want your students to gain from this novel study? Be sure to think beyond the novel, considering both transferable skills and broader knowledge.

Perhaps this novel study is meant to introduce students to a particular genre or literary element. Or maybe you’re honing in on a particular experience or culture. In other cases, especially in middle school, you may be looking to provide a deeper context into a historical event or period students are learning in social studies.

Regardless, novel studies are a great way to provide context and build a rich understanding. However, you must know what that purpose is so you can effectively fulfill it.

WHAT TO CONSIDER WHEN DEFINING YOUR PURPOSE FOR YOUR NOVEL STUDY.

- Essential question. As you define your purpose, consider any essential questions you are looking for your students to answer by the end of the novel study. These questions are usually big abstract questions attached to curriculum units. A question might be as abstract as, “What role does tradition play in society?” Or, it might be more literature-focused, such as, “How does character development help move a story forward?” or “How does setting impact a story?”

- Universal theme. Similar to an essential question, you might be planning your novel study around a universal theme such as “The American Dream,” “Identity,” or “Overcoming adversity.” Whatever the theme, it’s essential to understand its role in your purpose. It’s imperative to have this understanding before moving on to the next step.

- Standards. Remember, one of the benefits of facilitating a novel study is hitting multiple standards in a cohesive way. So, when planning your novel study, be sure to identify the target standards your study will cover. (This is especially important if you work in a district where you must submit unit plans that identify key targets.) Even if that doesn’t apply to you, it can help anchor your planning as you move forward. Stick to no more than three standards so you can be sure to touch upon each standard at least twice throughout the novel study. Any more than three standards and it will likely be hard to get beyond the surface level of the standards.

- Learning needs and goals. As you consider your purpose, look toward the specific needs of your class. Needs, and therefore goals, will differ from class to class. So, even if you’re revamping an existing novel study, be sure to revisit this component and adjust to your particular group of students.

Step 2: Choose Your Framework.

Once you have clarity around your purpose, the next step is to choose the framework for your novel study. There are three frameworks to consider:

- Whole-class novel study

- Small-group novel study

- Independent novel study

In a whole-class novel study , the whole group reads the same book. This approach creates a shared experience among the students as they engage in a particular text, supplemental materials, and assessments. Despite being a whole-class approach, you can implement various activities and reading techniques, including whole-class, partner, and independent reading.

In a small-group novel study , each group has a different text. You may decide to give students a say in which book they read, but ultimately, it’s imperative you match the students with the books that suit their abilities best. Depending on the needs of your classroom, the different groups may be working on similar or different skills and tasks. However, I recommend finding a unifying theme, essential question, or experience across all books if possible. That way, students can come together to engage in whole-class discussions.

Just as the name indicated, an independent novel study consists of each student reading their own text. This is a highly independent approach where you might offer mini-lessons throughout the unit, but students work on reading and responding to assignments independently. While some students thrive with this level of autonomy, I do not recommend this framework for struggling or reluctant readers. With that said, you might consider putting together an independent study for highly advanced readers despite a whole-class or small-group approach.

NOT SURE WHICH FRAMEWORK TO CHOOSE?

For this grade level, I recommend embarking on a whole-class or small-group novel study. However, if this is the first time the majority of your students are engaging in a novel study or if they require more direct instruction and guidance to achieve your desired goals, I suggest a whole class novel study. Typically speaking, this framework allows more room for redirection and adjustments on the fly. If your classroom includes a wide range of needs and abilities, a small-group novel study might just be the best way to target particular groups of students. If you are overwhelmed by the idea, I suggest using a similar approach for each group, adjusting the specifics of the supplemental material as needed. For example, perhaps you expect one group to fill out a graphic organizer as a response. However, you may provide the organizer to another group while asking them to turn in a fully developed written response. Alternatively, you can begin the year with a whole-class novel study to lay the foundation, introducing students to the components and expectations of this type of unit. Then, follow up with a small-group novel study later in the year to accommodate varying needs or simply give students more autonomy.

Step 3: Choose Your Book

When you choose the book(s) for your novel study, you’ll want to consider what resources you have available to you. If you’re planning this unit far enough in advance and have a hefty book budget, you might have more choice than a teacher working from a pre-approved reading list or library resources.

Regardless, this is why this step comes after clarifying your purpose. Be sure to select a book that aligns with your purpose. For example, will the book help students gain perspective around a historical event or period? Will students be able to apply the book when answering an essential question? Does it fit within the scope of the unit theme? The good news is novel studies have a lot of wiggle room. Unlike being confined to the content in a (potentially outdated) textbook, you have the freedom to select a novel that fits your goals and classroom needs. So, take advantage of the opportunity if you are able to.

HERE ARE A FEW THINGS TO CONSIDER WHEN CHOOSING YOUR NOVEL STUDY TEXT:

- Difficulty. This is your Goldilocks moment. You don’t want to select a book that is too difficult or too easy and risk losing student engagement. Instead, seek out that book that is juuuust right. (Remember, if that seems like an impossible task due to a diverse group, consider setting up a small-group novel study.

- Appropriateness. You want to consider what is appropriate for your student’s age. Just because a protagonist is 15 doesn’t mean you need to disregard it as an option. However, you might want to steer clear of books with vulgar language or references to sex, violence, and drugs. When considering appropriateness, be sure to consider parent and district expectations as well to avoid any potential backlash.

- Interest. Your students will be spending anywhere from a couple of weeks to a couple of months working with this text. So, while it might feel impossible to select a text that will pique everyone’s interests, consider the group as a whole. Will they find the story relatable or intriguing? Does it address a relatable theme or question? Even if you’re choosing (or required) to read a classic text, how can it be made relevant to modern society or students’ lives?

- Why? Again, be sure the text aligns with your purpose. This one is so important that, yes, I mentioned it twice.

Now, if you’ve chosen a book you haven’t yet read, your next step is to read the novel. Trust me; you don’t want to be surprised by inappropriate language or controversial topics. However, if you are crunched for time, I understand you may not have time to read an entire novel. At the very least, I suggest you read the synopsis and a handful of reviews to grasp the general storyline and identify any potential red flags in content. I also recommend doing a “finger walk” through the text to get a feel for the writing, including vocabulary and structure. Not everyone is looking to read a book written in diary format or verse. Alternatively, that might be exactly what you want!

WHILE YOU READ/REREAD

Let’s face it. Even as teachers, we might need a refresh and review on a novel we’ve read before. (Yes, even if we’ve taught it eight times.) So, as you read, consider paying attention to the following as you prepare to plan an entire novel study around the text:

- What from the text is relevant to the students’ lives? Modern society? Other areas they may be studying in other subjects?

- What themes and patterns are you finding? How do they fit into the overall goal of the novel study or overarching unit?

- What are you picking up on that you want your students to notice too?

- What literary elements do you want to teach or (at a minimum) point out in the story? (Things like parallel plot structure, character foils, monologue, extended metaphor, motif, static vs. dynamic characters, foreshadowing, etc.)

- What words might students need to know to build their vocabulary and/or enhance their understanding of the novel?

- How does the story unfold? How could it be broken up into manageable reading assignments for students?

- What parts of the story have a lot to unpack? Where do you feel students would benefit most from your input vs. independent reading?

From there, you can use your annotations to guide your focus when planning daily lessons, discussions, and assessments.

Step 4: Set Your Timeline.

When planning your novel study, you need to know how much time you plan to allot to this unit. In cases where you have limited time, you might need to flip-flop this step and the one prior.

Some novel studies move quicker than others. In some cases, you may only need four weeks, and in others, you may need an entire quarter. Your timeline will also depend on your daily schedule. Does your school operate on block scheduling? How long is each class period? Regardless, when deciding which timeline is right for you and your students, consider how much work you’d like done in class vs. at home. How much whole class reading do you plan on doing? That always takes longer than independent reading. Are you sharing this unit with supplemental minilessons to provide historical context or teach writing strategies? These are all things you want to keep in mind as you determine your timeline.

PLAN AHEAD.

As you’re setting up your timeline, you need to think beyond your novel study as well. I suggest marking off important dates to be mindful of as you plan your daily lessons. You don’t want to forget about half days or holidays– those could really throw off your plan if you’re not prepared. Additionally, it’s worth noting any days you know you will be out of the classroom for workshops, appointments, etc. I always recommend using those as independent workdays or “light” days. Mapping those out ahead of time can save you from stressfully shuffling things around for last minute adjustments.

Lastly, plan a buffer week. This extra week prepares you for the unexpected that is bound to come up. Maybe there was an unexpected school closure or an activity that took longer than expected. Whatever the interruption to your ideal timeline, it’s best to be prepared. Tacking on a buffer week to the end of your timeline will give you the wiggle room you need just in case. That way you don’t have to stress if you need to slow down or run into an unexpected obstacle.

In the rare event you end ahead of schedule (AKA on time)? Enjoy it. You can give the students an extra day or two on a final project, add in a fun activity that didn’t quite make the cut the first time around, or simply move on. (We all know that extra week will come in handy at some point down the line.)

I’m telling you, this buffer week is a teacher’s best-kept secret when it comes to planning a novel study.

ESTABLISH READING ASSIGNMENTS.

Once you establish your timeline, you have a foundation for determining your reading assignments. Use your timeline to help you determine how to best chunk out the novel. Account for both in-class and at-home reading, if applicable.

If you’re not sure how to chunk it out, divide the total number of pages in the book by the number of weeks you plan on dedicating to reading. (Remember, the first and last week might not involve reading, so be sure to double-check your plan.) Then divide that number by the number of days you plan on reading each week, in class or at home. You’ll likely have to adjust the number to match up with reasonable breaks in the text, like chapters, but it’s a dependable place to start. Once you know how many pages will be covered each day, in class or at home, be sure to denote which days will be specific for in-class reading. Feel free to mark down which type of in-class reading you’d like to do, such as whole class or independent reading. While this might seem oddly specific, it will help you when it comes to filling in the accompanying lessons and activities.

Additionally, planning both in-class and at-home reading helps you stay on track. Worst case, students have less homework or have to tack on a few extra pages. But trust me. Having a general idea will come in handy when planning out the details.

Step 5: Choose Your Final Assessment.

Start at the end. No, I’m not speaking in riddles. I am , however, talking about Backward Design. So, before filling your schedule with mini-lessons, formative assessments, and fun activities, determine how you will summatively assess your students at the end of the novel study.

Remember, the purpose of a novel study is to go beyond the basics and get students interacting with a text to build a deeper understanding. It’s about comprehension and critical thinking, not regurgitation. Steer clear of static multiple-choice questions and short answer prompts with limiting right and wrong answers. While these can make for quick exit tickets and reading checks, the final assessment should move beyond basic comprehension.

To do this, you’ll need to revisit your purpose. What are the learning goals and standards you are trying to assess by the end of this unit? Then, you need to determine how you are going to assess student learning. Is it going to be through a formal writing assignment? A reflection? A multi-faceted project? A formal discussion or presentation? Will students have a choice?

Once you have the final assessment squared away, be sure to add it to your calendar, marking the final due date. Then, you can work backward to fill in imperative dates to prepare students for the final assessment as needed. For example, certain assessments might need time for workshop days, peer revisions, or presentations. However, plan all of these dates (including the final due date) before the buffer week.

And don’t worry yet if you don’t have the exact assessment or rubrics finalized. For now, stay focused on the plan.

Step 6: Work Backward to Fill in the Rest!

Now that you have your essential framework laid out, it’s time to fill in the blanks! Using your reading schedule and final assessment, work backward to fill out the remaining blocks. You’ll want to incorporate activities before, during, and after reading to round out your novel study.

INTRODUCE THE NOVEL.

Start by planning out how you are going to introduce the novel. Do students need any background information before they dive in? Would it be useful to learn about the novel’s author, setting, or historical context? You can add other pre-reading activities like analyzing the book’s cover or discussing a relevant issue that appears in the book. Have students complete an anticipation guide or play four corners to begin exploring themes and conflicts in the novel.

CHECKING FOR READING COMPREHENSION.

Reading comprehension is an essential component of any novel study. Therefore, incorporate lessons and activities that address areas of comprehension such as identifying themes, examining character development and plot structure, summarizing, and making inferences and connections. You can accomplish these comprehension checks through group discussions, independently written responses, and group activities.

When planning for reading comprehension activities, be sure to incorporate a variety of activities. Not all students will shine through writing, but that doesn’t mean they don’t understand the novel and its essential elements. Adding a variety to your unit study will ensure each student has the opportunity to shine and showcase their comprehension in one way or another.

You’ll also want to leave room for any minilessons you plan on teaching to aid student comprehension. Do you need to plan a 20-minute lesson reviewing the elements of plot? Do you need to teach a lesson about literary devices or explain how to effectively annotate a text? Leave room for teaching such lessons and completing activities throughout the novel study.

BEFORE THE FINAL ASSESSMENT.

If time permits, consider incorporating a post-reading assignment that serves more as a fun review before jumping into the final assessment. This is a great opportunity for student choice and group mini-projects. Students can put together collages, redesign the cover, create a timeline of events, write a book review, or make a character scrapbook to review the essential elements of the story. Give them as many or as few guidelines as you feel necessary.

However, keep these activities to one or two classes. You don’t want them to take away from prepping for the final assessment. However, it’s an excellent way for students to interact with the whole text, providing a refresher before embarking on a summative assessment.

A FINAL WORD.

A piece of advice? Be realistic when planning. If you know your students aren’t going to be able to read 20 pages, watch a video clip, participate in a discussion, and write a response, don’t set that expectation for a single class period. It only creates stress and interrupts your plan. Instead, feel free to have a bank of optional extension activities you can pull from if needed. Character diary entries, connection prompts, and comic strips are some student favorites.

You’re Ready to Go!

The best part? Once you have a well-mapped-out novel study, you can rinse and repeat with different novels or groups of students from year to year. That way, you won’t have to start from scratch each time. I’m willing to bet there’s already a lot on your plate, so I’d hate for you to reinvent the wheel when you don’t have to.

But, for now, happy planning! Psst… Feel free to save this post to return to as needed throughout your planning process.

If you’re pressed for time or still feel overwhelmed don’t fear. I’ve premade some novel study resources I know you’ll find useful. Check them out!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Tutorials, Study Guides & More

How to study a novel

September 16, 2009 by Roy Johnson

reading novels and effective study skills

Why study a novel? There’s nothing wrong with reading a novel just to pass the time, or as an alternative to watching TV. But if you want to get more out of your reading experience, if you want to start appreciating the finer points of literature, or if you want to make a serious study of the books you read – then you need to go in at a deeper level. For this you may need new reading techniques.

The tips and skills listed here are not in any order of priority, and some may be more appropriate for the book you are reading than others. Use them in any combination possible, and I guarantee you’ll start seeing things in novels you never saw before.

Method There isn’t one single formula or a secret recipe for the successful study of a novel. But to do it seriously you should be a careful and attentive reader. This means reading, then re-reading. It means making an active engagement with the book, and it probably means reading more slowly than usual. And it means making notes.

Approach You can read the novel quickly first, just to get an idea of the story-line. Then you will need to read it again more slowly, making notes. If you don’t have time, then one careful slower reading should combine understanding and note-taking. For instance you could read a novella such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness quite quickly, then re-read it more carefully, making detailed notes. But in the case of a long novel such as Charles Dickens’s Bleak House it’s unlikely that you would have enough time to read it more than once. You would need to make the notes at the same time as a single reading.

Make notes There are two possible types of notes – some written in the pages of the book itself, and others on separate sheets of paper. Those in the book are for highlighting small details as you go along. Those on separate pages are for summaries of evidence, collections of your own observations, and page references for study topics or quotations.

Notes written in the book are absolutely vital if you are going to write about the book – say for a term paper or a coursework essay. They will save you hours of searching through the pages to locate a passage you wish to quote.

Notes in the book Use a soft pencil – not a pen. Ink is too distracting on the page. Don’t underline whole paragraphs. If something strikes you as interesting, write a brief note saying why or how it is so. If you read on the bus or in the bath, use the inside covers and any blank pages for making notes. Do not of course write in library books – only your own copy. To do so is both insulting to other readers, and very stupid – because you lose the notes when the book is returned.

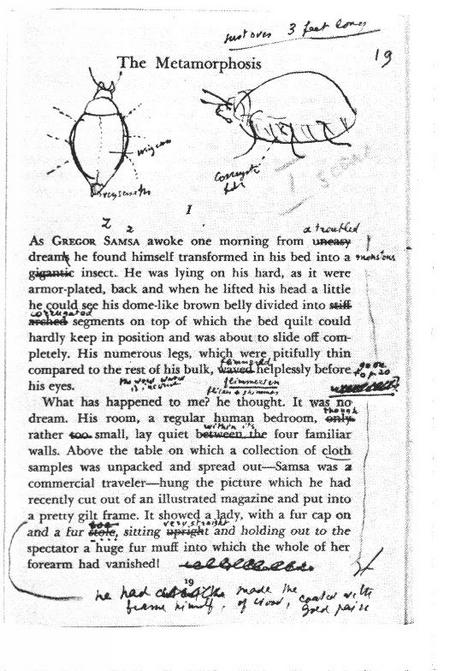

Vladimir Nabokov’s notes on Kafka’s Metamorphosis

What to note? You can nmake a note of anything that strikes you as interesting, but here are some suggestions:

- the appearance of characters

- recurring themes or motifs

- features of the author’s style

- plot twists or crucial scenes

- important details of the story

Some do’s and don’ts Underline up to a couple of lines of the text if necessary – but also put a word or two in the margin that gives it a title . In other words, give a name to what you think is important. Don’t underline whole paragraphs: that creates an ugly page, and it’s a waste of time. Instead, write a note in the top or bottom margin, saying what you think is important. Or put a circle round a name or a special couple of words.

Separate notes You will definitely remember the characters, events, and features of a novel more easily if you make notes whilst reading. Use separate pages for different topics. You might make a record of

- chronology of events

- major themes

- stylistic features

- narrative strategies

Characters Make a note of the name, age, appearance, and their relationship to other characters in the novel. Writers usually give most background information about characters when they are first introduced into the story. Make a note of the page(s) on which this occurs. Note any special features of main characters, what other characters (or the author) thinks of them.

Chronology of events A summary of each chapter will help you reconstruct the whole story long after you have read it. The summary prompts the traces of reading experience which lie dormant in your memory. If the book is divided into chapters, make a short summary of each one as you finish reading it.

A chronology of events might also help you to unravel a complex story. It might help separate plots from sub-plots, and even help you to see any underlying structure in the story – what might be called the ‘architecture of events’.

Major themes These are the important underlying issues with which the novel is concerned. They are usually summarised as abstract concepts such as – marriage, education, justice, freedom, and redemption. These might only emerge slowly as the novel progresses on first reading – though they might seem much more obvious on subsequent readings.

Seeing the main underlying themes will help you to appreciate the relative importance of events. It will also help you to spot cross-references and appreciate some of the subtle effects orchestrated by the author.

Stylistic features These are the decorative and literary hallmarks of the writer’s style – which usually make an important contribution to the way the story is told. The style might be created by any number of features:

- choice of vocabulary

- imagery and metaphors

- shifts in tone and register

- use of irony and humour

Quotations If you are writing an essay about the novel, you will need quotations from it to support your arguments. You must make a careful note of the pages on which they occur. Do this immediately whilst reading – otherwise tracking them down later will waste lots of time.

Record page number and a brief description of the subject. Write out the quotation itself if it is short enough. Don’t bother writing out long quotations.

Bibliography If you are reading literary criticism or background materials related to the novel – make a full bibliographic record of every source. In the case of books, you should record – Author, Book Title, Publisher, Place of publication, Date, Page number.

If you borrow the book from a library, make a full note of its number in the library’s classification system. This will save you time if you need to take it out again at a later date.

In the case of Internet and other digital sources (CDs, websites, videos) you need to look at our guidance notes on referencing digital sources .

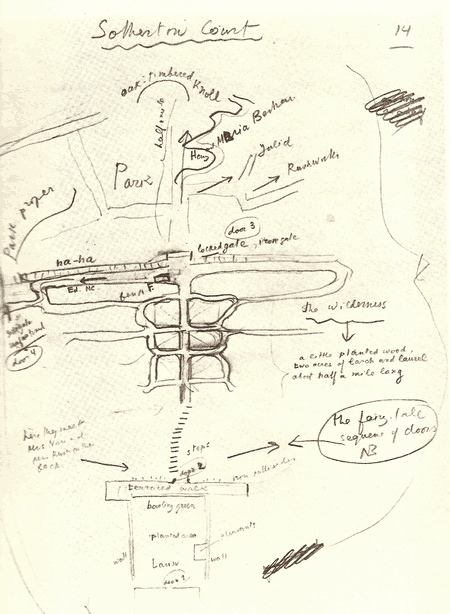

Maps and diagrams Some people have good visual memories. A diagram or map may help you to remember or conceptualise the ‘geography’ of events. Here’s Vladimir Nabokov’s diagram of the geography of Southerton in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park .

Chapter summaries Many novels are structured in chapters. After reading each chapter, make a one sentence summary of what it’s about. This can help you remember the events at a later date. The summary might be what ‘happens’ in an obvious sense [Mr X travels to London] but it might be something internal or psychological [Susan realises she is ‘alone’].

Deciding what is most important will help you to digest and remember the content of the novel. The process of deciding will also help you to separate the more important from the less important content.

Making links Events or characters or details of plot may have significant links between them, even though these are revealed to the reader many pages apart. Always make a note as soon as you see them – because they will be very hard to find later.

Use a dictionary Some novelists like to use unusual, obscure, or even foreign words. Take the trouble to look these up in a good dictionary. It will help you to understand the story and the author, and it will help to extend the range of your own vocabulary. If you need help choosing a good dictionary for studying, have a look at our guidance notes on the subject.

What is close reading? When you have become accustomed to looking at a novel in greater depth, you might be interested to know that there are four possible stages in the process of understanding what it has to offer and what can be said about it. These are the four, in increasing degree of complexity.

1. Linguistic You pay especially close attention to the surface linguistic elements of the text – that is, to aspects of vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. You might also note such things as figures of speech or any other features which contribute to the writer’s individual style. This level of reading is largely descriptive .

2. Semantic You take account at a deeper level of what the words mean – that is, what information they yield up, what meanings they denote and connote. This level of reading is cognitive . That is, we need to understand what the words are telling us – both at a surface and maybe at an implicit level.

3. Structural You note the possible relationships between words within the text – and this might include items from either the linguistic or semantic types of reading. This level of reading is analytic . You assess, examine, sift, and judge a large number of items from within the text in their relationships to each other.

4. Cultural You note the relationship of any elements of the text to things outside it. These might be other pieces of writing by the same author, or other writings of the same type by different writers. They might be items of social or cultural history, or even other academic disciplines which might seem relevant, such as philosophy or psychology. This level of reading is interpretive . We offer judgements on the work in its general relationship to a large body of cultural material outside it.

Next steps If you want a sample of these four levels of reading illustrated with brief extracts from a short story and a long novel, here are –

- Katherine Mansfield’s ‘The Voyage’

- Charles Dickens’s Bleak House

© Roy Johnson 2004

Literary studies links

Get in touch.

- Advertising

- T & C’s

- Testimonials

Oh Hey, ELA!

by Lindsay Flood

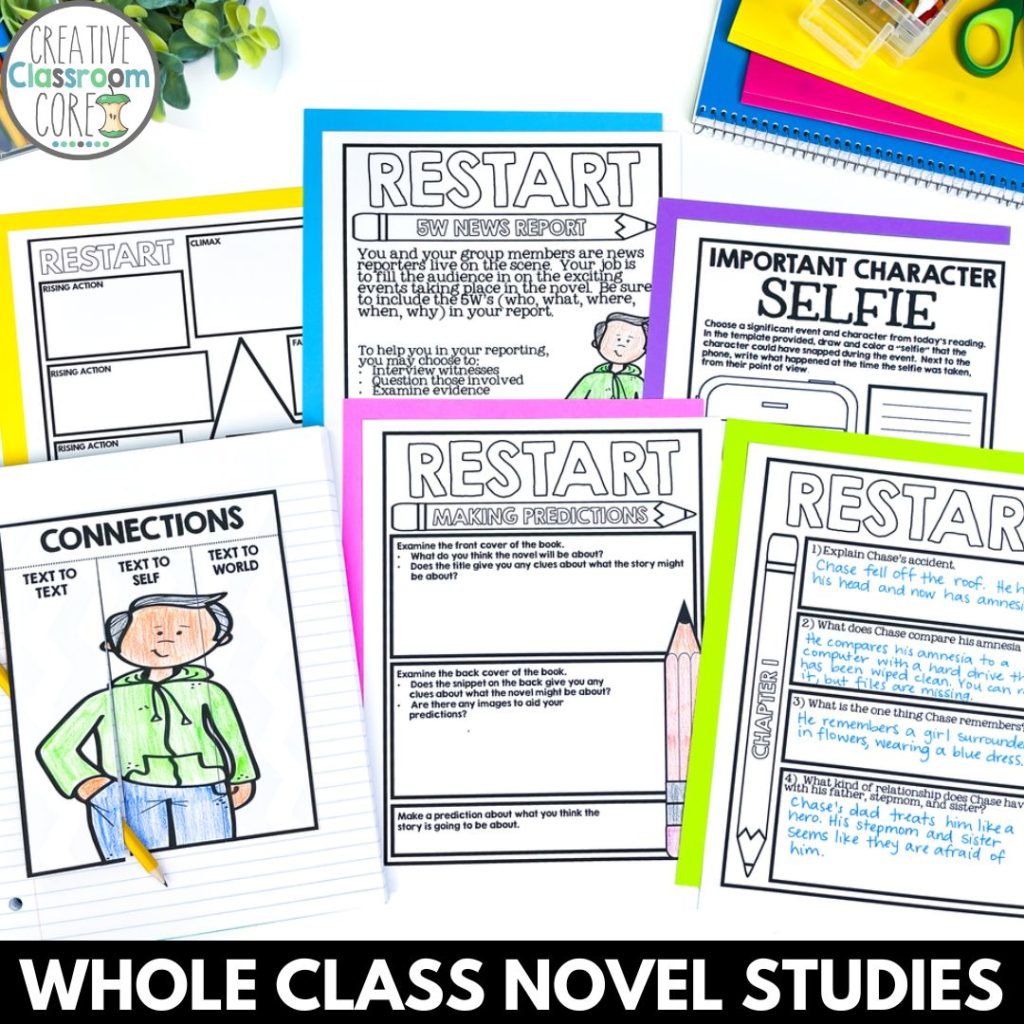

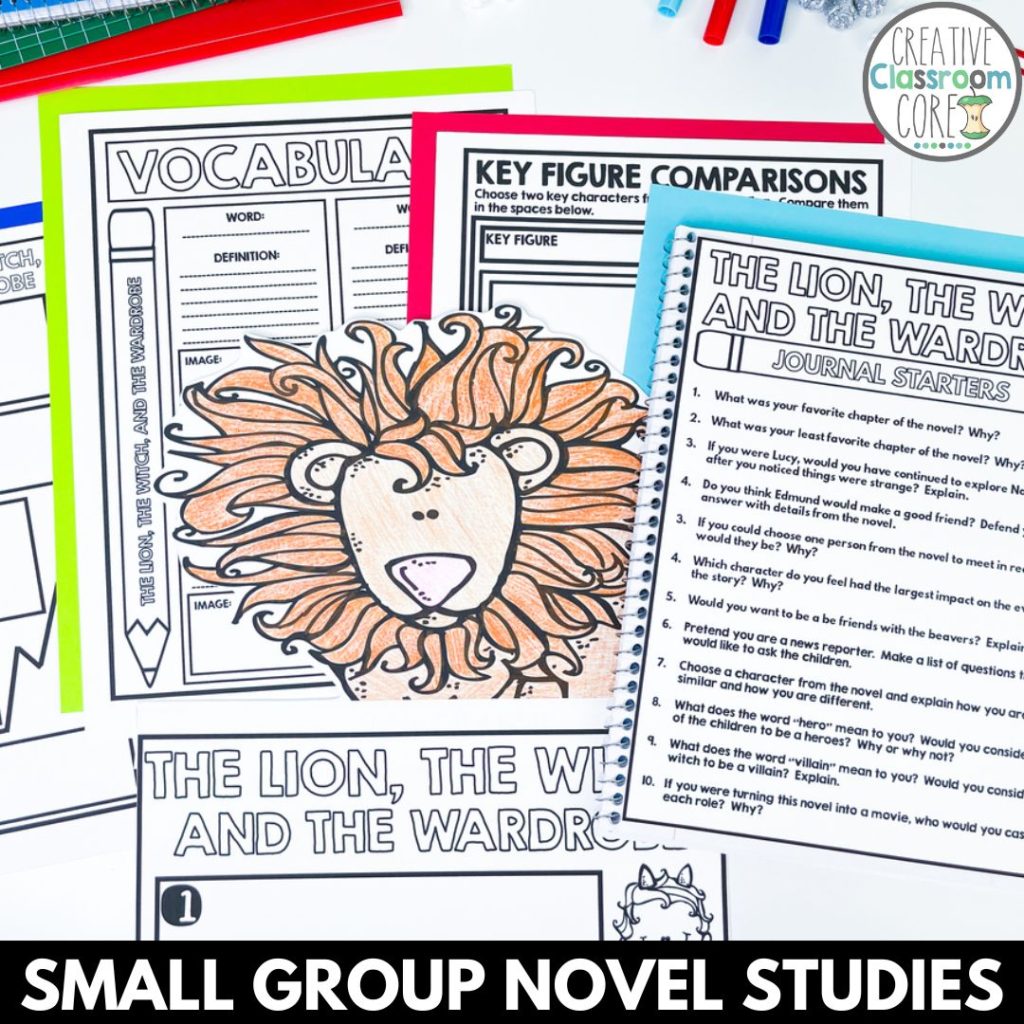

Novel Study for Any Novel

Teachers love novel studies. Students LOVE novel studies. However, novel studies can be a struggle for several reasons.

As a teacher, I want to talk about EVERY. SINGLE. THING. That’s obviously not always the best option. Because, well, the novel study would take 2ish years.

Still, I wanted my students to dig into the richness of a novel. The character development, plot line, inferences to be made. The flashbacks, the foreshadowing, the connections. OH my! Too good!

So, I figured out a way for my students to close read and analyze key points of a novel, and not just any novel , but for all novels.

What’s hard for students to recognize is how the events in the plot line connect with one another. The best way to watch these events unfold is in a novel.

So many elements of the exposition relate to the conflict, the character development, the reactions and motivations the characters demonstrate, as well as to the theme and the resolution. It’s easy to miss these connections in most novel studies.

The design of this particular novel study makes it easy for students to see the progression of that “Plot Roller Coaster” or “Plot Mountain” they’ve been drawing since 1 st grade. The tabs in the novel visually connect to the unfolding of the plot line. One of my students LITERALLY shouted, “THAT is so cool!” They love the tabs and to see the plot unfolding and connecting just by looking at the tabs makes they feel like they are truly analyzing and close reading.

With this novel study , my students were able to make deep, meaningful connections to critical parts of the novel that changed the direction of the plot line, or that opened the eyes of the reader’s understanding of a particular character’s perspective or lesson learned.

There are two things that I LOVE about this novel study : you can use it with any novel, and you can use in a variety of different ways with your students. Here are some ways that my students used the novel study in my classroom with the books A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park and Wonder by RJ Palacio.

Whole Group:

This novel study’s flexibility allows for an interactive and rigorous whole group graphic organizer. Because the students were focused on a particular set of paragraphs in the text, as a class, we were able to dig deeper into a paragraph (or two or three) and really study a character, the setting, mood and tone of the section, and the perspectives of the character. The graphic organizers were perfect for launching student discussion, making deep connections, and understanding how perspectives are formed based on the experiences of the characters prior to this section.

Small Group:

The collaborative aspect of meaningful, deep conversations that are guided by the graphic organizers in a small group are amazing . It’s based on the student’s analysis of a particular section of the text, but also leads the students to foreshadow, flashback, and make connections throughout the text that are focused on rigorous ELA standards and skills. Also, the students are able to learn from each other, by sharing their thinking and their perspectives in the small group setting. It’s amazing to see their “brains on the paper” as they work together and share their own thoughts and opinions and conclusions.

Homework: