From John W. Creswell \(2016\). 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher \ . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Chapter 1: Home

- Narrowing Your Topic

- Problem Statement

Purpose Statement Overview

Best practices for writing your purpose statement, writing your purpose statement, sample purpose statements.

- Student Experience Feedback Buttons

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Quantitative Research Questions This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative Research Questions This link opens in a new window

- Qualitative & Quantitative Research Support with the ASC This link opens in a new window

- Library Research Consultations This link opens in a new window

Jump to DSE Guide

The purpose statement succinctly explains (on no more than 1 page) the objectives of the research study. These objectives must directly address the problem and help close the stated gap. Expressed as a formula:

Good purpose statements:

- Flow from the problem statement and actually address the proposed problem

- Are concise and clear

- Answer the question ‘Why are you doing this research?’

- Match the methodology (similar to research questions)

- Have a ‘hook’ to get the reader’s attention

- Set the stage by clearly stating, “The purpose of this (qualitative or quantitative) study is to ...

In PhD studies, the purpose usually involves applying a theory to solve the problem. In other words, the purpose tells the reader what the goal of the study is, and what your study will accomplish, through which theoretical lens. The purpose statement also includes brief information about direction, scope, and where the data will come from.

A problem and gap in combination can lead to different research objectives, and hence, different purpose statements. In the example from above where the problem was severe underrepresentation of female CEOs in Fortune 500 companies and the identified gap related to lack of research of male-dominated boards; one purpose might be to explore implicit biases in male-dominated boards through the lens of feminist theory. Another purpose may be to determine how board members rated female and male candidates on scales of competency, professionalism, and experience to predict which candidate will be selected for the CEO position. The first purpose may involve a qualitative ethnographic study in which the researcher observes board meetings and hiring interviews; the second may involve a quantitative regression analysis. The outcomes will be very different, so it’s important that you find out exactly how you want to address a problem and help close a gap!

The purpose of the study must not only align with the problem and address a gap; it must also align with the chosen research method. In fact, the DP/DM template requires you to name the research method at the very beginning of the purpose statement. The research verb must match the chosen method. In general, quantitative studies involve “closed-ended” research verbs such as determine , measure , correlate , explain , compare , validate , identify , or examine ; whereas qualitative studies involve “open-ended” research verbs such as explore , understand , narrate , articulate [meanings], discover , or develop .

A qualitative purpose statement following the color-coded problem statement (assumed here to be low well-being among financial sector employees) + gap (lack of research on followers of mid-level managers), might start like this:

In response to declining levels of employee well-being, the purpose of the qualitative phenomenology was to explore and understand the lived experiences related to the well-being of the followers of novice mid-level managers in the financial services industry. The levels of follower well-being have been shown to correlate to employee morale, turnover intention, and customer orientation (Eren et al., 2013). A combined framework of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory and the employee well-being concept informed the research questions and supported the inquiry, analysis, and interpretation of the experiences of followers of novice managers in the financial services industry.

A quantitative purpose statement for the same problem and gap might start like this:

In response to declining levels of employee well-being, the purpose of the quantitative correlational study was to determine which leadership factors predict employee well-being of the followers of novice mid-level managers in the financial services industry. Leadership factors were measured by the Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) assessment framework by Mantlekow (2015), and employee well-being was conceptualized as a compound variable consisting of self-reported turnover-intent and psychological test scores from the Mental Health Survey (MHS) developed by Johns Hopkins University researchers.

Both of these purpose statements reflect viable research strategies and both align with the problem and gap so it’s up to the researcher to design a study in a manner that reflects personal preferences and desired study outcomes. Note that the quantitative research purpose incorporates operationalized concepts or variables ; that reflect the way the researcher intends to measure the key concepts under study; whereas the qualitative purpose statement isn’t about translating the concepts under study as variables but instead aim to explore and understand the core research phenomenon.

Always keep in mind that the dissertation process is iterative, and your writing, over time, will be refined as clarity is gradually achieved. Most of the time, greater clarity for the purpose statement and other components of the Dissertation is the result of a growing understanding of the literature in the field. As you increasingly master the literature you will also increasingly clarify the purpose of your study.

The purpose statement should flow directly from the problem statement. There should be clear and obvious alignment between the two and that alignment will get tighter and more pronounced as your work progresses.

The purpose statement should specifically address the reason for conducting the study, with emphasis on the word specifically. There should not be any doubt in your readers’ minds as to the purpose of your study. To achieve this level of clarity you will need to also insure there is no doubt in your mind as to the purpose of your study.

Many researchers benefit from stopping your work during the research process when insight strikes you and write about it while it is still fresh in your mind. This can help you clarify all aspects of a dissertation, including clarifying its purpose.

Your Chair and your committee members can help you to clarify your study’s purpose so carefully attend to any feedback they offer.

The purpose statement should reflect the research questions and vice versa. The chain of alignment that began with the research problem description and continues on to the research purpose, research questions, and methodology must be respected at all times during dissertation development. You are to succinctly describe the overarching goal of the study that reflects the research questions. Each research question narrows and focuses the purpose statement. Conversely, the purpose statement encompasses all of the research questions.

Identify in the purpose statement the research method as quantitative, qualitative or mixed (i.e., “The purpose of this [qualitative/quantitative/mixed] study is to ...)

Avoid the use of the phrase “research study” since the two words together are redundant.

Follow the initial declaration of purpose with a brief overview of how, with what instruments/data, with whom and where (as applicable) the study will be conducted. Identify variables/constructs and/or phenomenon/concept/idea. Since this section is to be a concise paragraph, emphasis must be placed on the word brief. However, adding these details will give your readers a very clear picture of the purpose of your research.

Developing the purpose section of your dissertation is usually not achieved in a single flash of insight. The process involves a great deal of reading to find out what other scholars have done to address the research topic and problem you have identified. The purpose section of your dissertation could well be the most important paragraph you write during your academic career, and every word should be carefully selected. Think of it as the DNA of your dissertation. Everything else you write should emerge directly and clearly from your purpose statement. In turn, your purpose statement should emerge directly and clearly from your research problem description. It is good practice to print out your problem statement and purpose statement and keep them in front of you as you work on each part of your dissertation in order to insure alignment.

It is helpful to collect several dissertations similar to the one you envision creating. Extract the problem descriptions and purpose statements of other dissertation authors and compare them in order to sharpen your thinking about your own work. Comparing how other dissertation authors have handled the many challenges you are facing can be an invaluable exercise. Keep in mind that individual universities use their own tailored protocols for presenting key components of the dissertation so your review of these purpose statements should focus on content rather than form.

Once your purpose statement is set it must be consistently presented throughout the dissertation. This may require some recursive editing because the way you articulate your purpose may evolve as you work on various aspects of your dissertation. Whenever you make an adjustment to your purpose statement you should carefully follow up on the editing and conceptual ramifications throughout the entire document.

In establishing your purpose you should NOT advocate for a particular outcome. Research should be done to answer questions not prove a point. As a researcher, you are to inquire with an open mind, and even when you come to the work with clear assumptions, your job is to prove the validity of the conclusions reached. For example, you would not say the purpose of your research project is to demonstrate that there is a relationship between two variables. Such a statement presupposes you know the answer before your research is conducted and promotes or supports (advocates on behalf of) a particular outcome. A more appropriate purpose statement would be to examine or explore the relationship between two variables.

Your purpose statement should not imply that you are going to prove something. You may be surprised to learn that we cannot prove anything in scholarly research for two reasons. First, in quantitative analyses, statistical tests calculate the probability that something is true rather than establishing it as true. Second, in qualitative research, the study can only purport to describe what is occurring from the perspective of the participants. Whether or not the phenomenon they are describing is true in a larger context is not knowable. We cannot observe the phenomenon in all settings and in all circumstances.

It is important to distinguish in your mind the differences between the Problem Statement and Purpose Statement.

The Problem Statement is why I am doing the research

The Purpose Statement is what type of research I am doing to fit or address the problem

The Purpose Statement includes:

- Method of Study

- Specific Population

Remember, as you are contemplating what to include in your purpose statement and then when you are writing it, the purpose statement is a concise paragraph that describes the intent of the study, and it should flow directly from the problem statement. It should specifically address the reason for conducting the study, and reflect the research questions. Further, it should identify the research method as qualitative, quantitative, or mixed. Then provide a brief overview of how the study will be conducted, with what instruments/data collection methods, and with whom (subjects) and where (as applicable). Finally, you should identify variables/constructs and/or phenomenon/concept/idea.

Qualitative Purpose Statement

Creswell (2002) suggested for writing purpose statements in qualitative research include using deliberate phrasing to alert the reader to the purpose statement. Verbs that indicate what will take place in the research and the use of non-directional language that do not suggest an outcome are key. A purpose statement should focus on a single idea or concept, with a broad definition of the idea or concept. How the concept was investigated should also be included, as well as participants in the study and locations for the research to give the reader a sense of with whom and where the study took place.

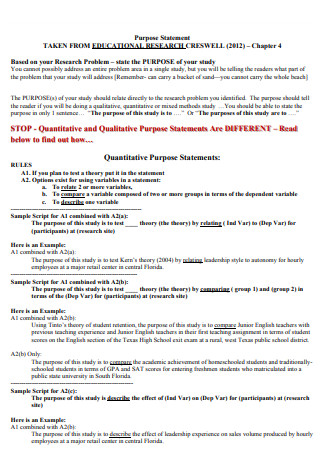

Creswell (2003) advised the following script for purpose statements in qualitative research:

“The purpose of this qualitative_________________ (strategy of inquiry, such as ethnography, case study, or other type) study is (was? will be?) to ________________ (understand? describe? develop? discover?) the _________________(central phenomenon being studied) for ______________ (the participants, such as the individual, groups, organization) at __________(research site). At this stage in the research, the __________ (central phenomenon being studied) will be generally defined as ___________________ (provide a general definition)” (pg. 90).

Quantitative Purpose Statement

Creswell (2003) offers vast differences between the purpose statements written for qualitative research and those written for quantitative research, particularly with respect to language and the inclusion of variables. The comparison of variables is often a focus of quantitative research, with the variables distinguishable by either the temporal order or how they are measured. As with qualitative research purpose statements, Creswell (2003) recommends the use of deliberate language to alert the reader to the purpose of the study, but quantitative purpose statements also include the theory or conceptual framework guiding the study and the variables that are being studied and how they are related.

Creswell (2003) suggests the following script for drafting purpose statements in quantitative research:

“The purpose of this _____________________ (experiment? survey?) study is (was? will be?) to test the theory of _________________that _________________ (compares? relates?) the ___________(independent variable) to _________________________(dependent variable), controlling for _______________________ (control variables) for ___________________ (participants) at _________________________ (the research site). The independent variable(s) _____________________ will be generally defined as _______________________ (provide a general definition). The dependent variable(s) will be generally defined as _____________________ (provide a general definition), and the control and intervening variables(s), _________________ (identify the control and intervening variables) will be statistically controlled in this study” (pg. 97).

- The purpose of this qualitative study was to determine how participation in service-learning in an alternative school impacted students academically, civically, and personally. There is ample evidence demonstrating the failure of schools for students at-risk; however, there is still a need to demonstrate why these students are successful in non-traditional educational programs like the service-learning model used at TDS. This study was unique in that it examined one alternative school’s approach to service-learning in a setting where students not only serve, but faculty serve as volunteer teachers. The use of a constructivist approach in service-learning in an alternative school setting was examined in an effort to determine whether service-learning participation contributes positively to academic, personal, and civic gain for students, and to examine student and teacher views regarding the overall outcomes of service-learning. This study was completed using an ethnographic approach that included observations, content analysis, and interviews with teachers at The David School.

- The purpose of this quantitative non-experimental cross-sectional linear multiple regression design was to investigate the relationship among early childhood teachers’ self-reported assessment of multicultural awareness as measured by responses from the Teacher Multicultural Attitude Survey (TMAS) and supervisors’ observed assessment of teachers’ multicultural competency skills as measured by the Multicultural Teaching Competency Scale (MTCS) survey. Demographic data such as number of multicultural training hours, years teaching in Dubai, curriculum program at current school, and age were also examined and their relationship to multicultural teaching competency. The study took place in the emirate of Dubai where there were 14,333 expatriate teachers employed in private schools (KHDA, 2013b).

- The purpose of this quantitative, non-experimental study is to examine the degree to which stages of change, gender, acculturation level and trauma types predicts the reluctance of Arab refugees, aged 18 and over, in the Dearborn, MI area, to seek professional help for their mental health needs. This study will utilize four instruments to measure these variables: University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA: DiClemente & Hughes, 1990); Cumulative Trauma Scale (Kira, 2012); Acculturation Rating Scale for Arabic Americans-II Arabic and English (ARSAA-IIA, ARSAA-IIE: Jadalla & Lee, 2013), and a demographic survey. This study will examine 1) the relationship between stages of change, gender, acculturation levels, and trauma types and Arab refugees’ help-seeking behavior, 2) the degree to which any of these variables can predict Arab refugee help-seeking behavior. Additionally, the outcome of this study could provide researchers and clinicians with a stage-based model, TTM, for measuring Arab refugees’ help-seeking behavior and lay a foundation for how TTM can help target the clinical needs of Arab refugees. Lastly, this attempt to apply the TTM model to Arab refugees’ condition could lay the foundation for future research to investigate the application of TTM to clinical work among refugee populations.

- The purpose of this qualitative, phenomenological study is to describe the lived experiences of LLM for 10 EFL learners in rural Guatemala and to utilize that data to determine how it conforms to, or possibly challenges, current theoretical conceptions of LLM. In accordance with Morse’s (1994) suggestion that a phenomenological study should utilize at least six participants, this study utilized semi-structured interviews with 10 EFL learners to explore why and how they have experienced the motivation to learn English throughout their lives. The methodology of horizontalization was used to break the interview protocols into individual units of meaning before analyzing these units to extract the overarching themes (Moustakas, 1994). These themes were then interpreted into a detailed description of LLM as experienced by EFL students in this context. Finally, the resulting description was analyzed to discover how these learners’ lived experiences with LLM conformed with and/or diverged from current theories of LLM.

- The purpose of this qualitative, embedded, multiple case study was to examine how both parent-child attachment relationships are impacted by the quality of the paternal and maternal caregiver-child interactions that occur throughout a maternal deployment, within the context of dual-military couples. In order to examine this phenomenon, an embedded, multiple case study was conducted, utilizing an attachment systems metatheory perspective. The study included four dual-military couples who experienced a maternal deployment to Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) or Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) when they had at least one child between 8 weeks-old to 5 years-old. Each member of the couple participated in an individual, semi-structured interview with the researcher and completed the Parenting Relationship Questionnaire (PRQ). “The PRQ is designed to capture a parent’s perspective on the parent-child relationship” (Pearson, 2012, para. 1) and was used within the proposed study for this purpose. The PRQ was utilized to triangulate the data (Bekhet & Zauszniewski, 2012) as well as to provide some additional information on the parents’ perspective of the quality of the parent-child attachment relationship in regards to communication, discipline, parenting confidence, relationship satisfaction, and time spent together (Pearson, 2012). The researcher utilized the semi-structured interview to collect information regarding the parents' perspectives of the quality of their parental caregiver behaviors during the deployment cycle, the mother's parent-child interactions while deployed, the behavior of the child or children at time of reunification, and the strategies or behaviors the parents believe may have contributed to their child's behavior at the time of reunification. The results of this study may be utilized by the military, and by civilian providers, to develop proactive and preventive measures that both providers and parents can implement, to address any potential adverse effects on the parent-child attachment relationship, identified through the proposed study. The results of this study may also be utilized to further refine and understand the integration of attachment theory and systems theory, in both clinical and research settings, within the field of marriage and family therapy.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Problem Statement

- Next: Alignment >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 2:48 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1006886

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

9 Examples: How to Write a Purpose Statement

- Key Elements of a Purpose Statement Part 1

- How to Write a Purpose Statement Step-by-Step Part 2

- Identifying Your Goals Part 3

- Defining Your Audience Part 4

- Outlining Your Methods Part 5

- Stating the Expected Outcomes Part 6

- Purpose Statement Example for a Research Paper Part 7

- Purpose Statement Example For Personal Goals Part 8

- Purpose Statement Example For Business Objectives Part 9

- Purpose Statement Example For an Essay Part 10

- Purpose Statement Example For a Proposal Part 11

- Purpose Statement Example For a Report Part 12

- Purpose Statement Example For a Project Part 13

- Purpose Statement Templates Part 14

A purpose statement is a vital component of any project, as it sets the tone for the entire piece of work. It tells the reader what the project is about, why it’s important, and what the writer hopes to achieve.

Part 1 Key Elements of a Purpose Statement

When writing a purpose statement, there are several key elements that you should keep in mind. These elements will help you to create a clear, concise, and effective statement that accurately reflects your goals and objectives.

1. The Problem or Opportunity

The first element of a purpose statement is the problem or opportunity that you are addressing. This should be a clear and specific description of the issue that you are trying to solve or the opportunity that you are pursuing.

2. The Target Audience

The second element is the target audience for your purpose statement. This should be a clear and specific description of the group of people who will benefit from your work.

3. The Solution

The third element is the solution that you are proposing. This should be a clear and specific description of the action that you will take to address the problem or pursue the opportunity.

4. The Benefits

The fourth element is the benefits that your solution will provide. This should be a clear and specific description of the positive outcomes that your work will achieve.

5. The Action Plan

The fifth element is the action plan that you will follow to implement your solution. This should be a clear and specific description of the steps that you will take to achieve your goals.

Part 2 How to Write a Purpose Statement Step-by-Step

Writing a purpose statement is an essential part of any research project. It helps to clarify the purpose of your study and provides direction for your research. Here are some steps to follow when writing a purpose statement:

- Start with a clear research question: The first step in writing a purpose statement is to have a clear research question. This question should be specific and focused on the topic you want to research.

- Identify the scope of your study: Once you have a clear research question, you need to identify the scope of your study. This involves determining what you will and will not include in your research.

- Define your research objectives: Your research objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound. They should also be aligned with your research question and the scope of your study.

- Determine your research design: Your research design will depend on the nature of your research question and the scope of your study. You may choose to use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods approach.

- Write your purpose statement: Your purpose statement should be a clear and concise statement that summarizes the purpose of your study. It should include your research question, the scope of your study, your research objectives, and your research design.

Research question: What are the effects of social media on teenage mental health?

Scope of study: This study will focus on teenagers aged 13-18 in the United States.

Research objectives: To determine the prevalence of social media use among teenagers, to identify the types of social media used by teenagers, to explore the relationship between social media use and mental health, and to provide recommendations for parents, educators, and mental health professionals.

Research design: This study will use a mixed-methods approach, including a survey and interviews with teenagers and mental health professionals.

Purpose statement: The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of social media on teenage mental health among teenagers aged 13-18 in the United States. The study will use a mixed-methods approach, including a survey and interviews with teenagers and mental health professionals. The research objectives are to determine the prevalence of social media use among teenagers, to identify the types of social media used by teenagers, to explore the relationship between social media use and mental health, and to provide recommendations for parents, educators, and mental health professionals.

Part 3 Section 1: Identifying Your Goals

Before you start writing your purpose statement, it’s important to identify your goals. To do this, ask yourself the following questions:

- What do I want to achieve?

- What problem do I want to solve?

- What impact do I want to make?

Once you have a clear idea of your goals, you can start crafting your purpose statement. Your purpose statement should be a clear and concise statement that outlines the purpose of your work.

For example, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a business, your statement might look something like this:

“Our purpose is to provide high-quality products and services that improve the lives of our customers and contribute to the growth and success of our company.”

If you’re writing a purpose statement for a non-profit organization, your statement might look something like this:

“Our purpose is to improve the lives of underserved communities by providing access to education, healthcare, and other essential services.”

Remember, your purpose statement should be specific, measurable, and achievable. It should also be aligned with your values and goals, and it should inspire and motivate you to take action.

Part 4 Section 2: Defining Your Audience

Once you have established the purpose of your statement, it’s important to consider who your audience is. The audience for your purpose statement will depend on the context in which it will be used. For example, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a research paper, your audience will likely be your professor or academic peers. If you’re writing a purpose statement for a business proposal, your audience may be potential investors or clients.

Defining your audience is important because it will help you tailor your purpose statement to the specific needs and interests of your readers. You want to make sure that your statement is clear, concise, and relevant to your audience.

To define your audience, consider the following questions:

- Who will be reading your purpose statement?

- What is their level of knowledge or expertise on the topic?

- What are their needs and interests?

- What do they hope to gain from reading your purpose statement?

Once you have a clear understanding of your audience, you can begin to craft your purpose statement with their needs and interests in mind. This will help ensure that your statement is effective in communicating your goals and objectives to your readers.

For example, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a research paper on the effects of climate change on agriculture, your audience may be fellow researchers in the field of environmental science. In this case, you would want to make sure that your purpose statement is written in a way that is clear and concise, using technical language that is familiar to your audience.

Or, if you’re writing a purpose statement for a business proposal to potential investors, your audience may be less familiar with the technical aspects of your project. In this case, you would want to make sure that your purpose statement is written in a way that is easy to understand, using clear and concise language that highlights the benefits of your proposal.

The key to defining your audience is to put yourself in their shoes and consider what they need and want from your purpose statement.

Part 5 Section 3: Outlining Your Methods

After you have identified the purpose of your statement, it is time to outline your methods. This section should describe how you plan to achieve your goal and the steps you will take to get there. Here are a few tips to help you outline your methods effectively:

- Start with a general overview: Begin by providing a brief overview of the methods you plan to use. This will give your readers a sense of what to expect in the following paragraphs.

- Break down your methods: Break your methods down into smaller, more manageable steps. This will make it easier for you to stay organized and for your readers to follow along.

- Use bullet points: Bullet points can help you organize your ideas and make your methods easier to read. Use them to list the steps you will take to achieve your goal.

- Be specific: Make sure you are specific about the methods you plan to use. This will help your readers understand exactly what you are doing and why.

- Provide examples: Use examples to illustrate your methods. This will make it easier for your readers to understand what you are trying to accomplish.

Part 6 Section 4: Stating the Expected Outcomes

After defining the problem and the purpose of your research, it’s time to state the expected outcomes. This is where you describe what you hope to achieve by conducting your research. The expected outcomes should be specific and measurable, so you can determine if you have achieved your goals.

It’s important to be realistic when stating your expected outcomes. Don’t make exaggerated or false claims, and don’t promise something that you can’t deliver. Your expected outcomes should be based on your research question and the purpose of your study.

Here are some examples of expected outcomes:

- To identify the factors that contribute to employee turnover in the company.

- To develop a new marketing strategy that will increase sales by 20% within the next year.

- To evaluate the effectiveness of a new training program for improving customer service.

- To determine the impact of social media on consumer behavior.

When stating your expected outcomes, make sure they align with your research question and purpose statement. This will help you stay focused on your goals and ensure that your research is relevant and meaningful.

In addition to stating your expected outcomes, you should also describe how you will measure them. This could involve collecting data through surveys, interviews, or experiments, or analyzing existing data from sources such as government reports or industry publications.

Part 7 Purpose Statement Example for a Research Paper

If you are writing a research paper, your purpose statement should clearly state the objective of your study. Here is an example of a purpose statement for a research paper:

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of social media on the mental health of teenagers in the United States.

This purpose statement clearly states the objective of the study and provides a specific focus for the research.

Part 8 Purpose Statement Example For Personal Goals

When writing a purpose statement for your personal goals, it’s important to clearly define what you want to achieve and why. Here’s a template that can help you get started:

“I want to [goal] so that [reason]. I will achieve this by [action].”

Example: “I want to lose 10 pounds so that I can feel more confident in my body. I will achieve this by going to the gym three times a week and cutting out sugary snacks.”

Remember to be specific and realistic when setting your goals and actions, and to regularly review and adjust your purpose statement as needed.

Part 9 Purpose Statement Example For Business Objectives

If you’re writing a purpose statement for a business objective, this template can help you get started:

[Objective] [Action verb] [Target audience] [Outcome or benefit]

Here’s an example using this template:

Increase online sales by creating a more user-friendly website for millennial shoppers.

This purpose statement is clear and concise. It identifies the objective (increase online sales), the action verb (creating), the target audience (millennial shoppers), and the outcome or benefit (a more user-friendly website).

Part 10 Purpose Statement Example For an Essay

“The purpose of this essay is to examine the causes and consequences of climate change, with a focus on the role of human activities, and to propose solutions that can mitigate its impact on the environment and future generations.”

This purpose statement clearly states the subject of the essay (climate change), what aspects will be explored (causes, consequences, human activities), and the intended outcome (proposing solutions). It provides a clear roadmap for the reader and sets the direction for the essay.

Part 11 Purpose Statement Example For a Proposal

“The purpose of this proposal is to secure funding and support for the establishment of a community garden in [Location], aimed at promoting sustainable urban agriculture, fostering community engagement, and improving local access to fresh, healthy produce.”

Why this purpose statement is effective:

- The subject of the proposal is clear: the establishment of a community garden.

- The specific goals of the project are outlined: promoting sustainable urban agriculture, fostering community engagement, and improving local access to fresh produce.

- The overall objective of the proposal is evident: securing funding and support.

Part 12 Purpose Statement Example For a Report

“The purpose of this report is to analyze current market trends in the electric vehicle (EV) industry, assess consumer preferences and buying behaviors, and provide strategic recommendations to guide [Company Name] in entering this growing market segment.”

- The subject of the report is provided: market trends in the electric vehicle industry.

- The specific goals of the report are analysis of market trends, assessment of consumer preferences, and strategic recommendations.

- The overall objective of the report is clear: providing guidance for the company’s entry into the EV market.

Part 13 Purpose Statement Example For a Project

“The purpose of this project is to design and implement a new employee wellness program that promotes physical and mental wellbeing in the workplace.”

This purpose statement clearly outlines the objective of the project, which is to create a new employee wellness program. The program is designed to promote physical and mental wellbeing in the workplace, which is a key concern for many employers. By implementing this program, the company aims to improve employee health, reduce absenteeism, and increase productivity. The purpose statement is concise and specific, providing a clear direction for the project team to follow. It highlights the importance of the project and its potential benefits for the company and its employees.

Part 14 Purpose Statement Templates

When writing a purpose statement, it can be helpful to use a template to ensure that you cover all the necessary components:

Template 1: To [action] [target audience] in order to [outcome]

This template is a straightforward way to outline your purpose statement. Simply fill in the blanks with the appropriate information:

- The purpose of […] is

- To [action]: What action do you want to take?

- [Target audience]: Who is your target audience?

- In order to [outcome]: What outcome do you hope to achieve?

For example:

- The purpose of our marketing campaign is to increase brand awareness among young adults in urban areas, in order to drive sales and revenue growth.

- The purpose of our employee training program is to improve customer service skills among our frontline staff, in order to enhance customer satisfaction and loyalty.

- The purpose of our new product launch is to expand our market share in the healthcare industry, by offering a unique solution to the needs of elderly patients with chronic conditions.

Template 2: This [project/product] is designed to [action] [target audience] by [method] in order to [outcome].

This template is useful for purpose statements that involve a specific project or product. Fill in the blanks with the appropriate information:

- This [project/product]: What is your project or product?

- Is designed to [action]: What action do you want to take?

- By [method]: What method will you use to achieve your goal?

- This app is designed to provide personalized nutrition advice to athletes by analyzing their training data in order to optimize performance.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key elements of a purpose statement.

A purpose statement should clearly communicate the main goal or objective of your writing. It should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your work. The key elements of a purpose statement include the topic or subject matter, the intended audience, and the overall goal or objective of your writing.

How can a purpose statement benefit your writing?

A purpose statement can help you stay focused and on track when writing. It can also help you to avoid going off-topic or getting bogged down in unnecessary details. By clearly identifying the main goal or objective of your writing, a purpose statement can help you to stay organized and ensure that your writing is effective and impactful.

What are some common mistakes to avoid when writing a purpose statement?

One common mistake is being too vague or general in your purpose statement. Another mistake is making your purpose statement too long or complex, which can make it difficult to understand. Additionally, it’s important to avoid including unnecessary information or details that are not directly relevant to your main goal or objective.

How can you tailor your purpose statement to your audience?

When writing a purpose statement, it’s important to consider your audience and their needs. You should tailor your purpose statement to your audience by using language and terminology that they will understand. You should also consider their level of knowledge or expertise on the subject matter and adjust your purpose statement accordingly.

What are some effective templates for writing a purpose statement?

There are many effective templates for writing a purpose statement, but one common approach is to use the following structure: “The purpose of this writing is to [insert goal or objective] for [insert audience] regarding [insert topic or subject matter].”

Can you provide examples of successful purpose statements?

- “The purpose of this report is to provide an analysis of the current market trends and make recommendations for future growth strategies for our company.”

- “The purpose of this essay is to explore the impact of social media on modern communication and its implications for society.”

- “The purpose of this proposal is to secure funding for a new community center that will provide educational and recreational opportunities for local residents.”

- 20 Inspiring Examples: How to Write a Personal Mission Statement

- 5 Examples: How to Write a Letter of Employment

- 6 Example Emails: How to Ask for a Letter of Recommendation

- 2 Templates and Examples: Individual Development Plan

- 5 Effective Examples: How to Write a Two-Week Notice

- 3 Examples: Job Application Email (with Tips)

How to Write a Qualitative Purpose Statement

Yashekia king.

A qualitative purpose statement in a research plan is an important step when you completing your master’s degree thesis or doctoral degree dissertation. The purpose statement allows you to clearly and concisely describe the intent of your qualitative study so that your reader can anticipate the information he will receive in your research report. Qualitative research involves capturing the complexity of behavior that occurs in natural settings, while the opposite goal of quantitative research is to collect data in the form of numbers. Write a qualitative purpose statement in about 100 words or less.

Describe the type of testing or method of inquiry you will use to do your qualitative research. State if you plan to perform an experiment or do a correlational analysis, the process of using statistical data to evaluate the extent of relations between variables. Explain if you will perform ethnographic research, a social science research method that depends on personal experience and participation rather than just observation.

Explain the purpose of the qualitative study you will perform. For instance, identify the variables you are testing and analyzing or the observable occurrences or phenomena you are striving to discover. Use words such as “discover,” “explore,” “develop” or “describe” regarding your research objective and indicate what is likely necessary to conduct the study. Foreshadow the hypotheses you will test or the questions your research will raise. Describe the significance of your study and how it will contribute to past research and existing knowledge on your research topic.

Name the setting and population of your qualitative study. For example, state that your research concerns employees working in a national restaurant chain or people with disabilities and their families. Describe how the researcher and participants will interact with one another in your study - if will they be observed, interviewed or asked to fill out a questionnaire, for example.

Expand on your primary qualitative study purpose by explaining additional purposes of your research. Describe extra variables related to these additional purposes as well as additional qualitative phenomena you want to discover. Reiterate the central concepts and ideas being studied.

- Read over your qualitative purpose statement, making sure the statement is written in future tense so that you indicate what the purpose and variables "will be." Check for errors in spelling, grammar, usage and punctuation.

- 1 WordNet: Correlational Analysis

- 2 American University: Notes on Qualitative Research; Julie Mertus

- 3 Emory University: The Elements of a Proposal; Frank Pajares; 2007

About the Author

YaShekia King, of Indianapolis, began writing professionally in 2003. Her work has appeared in several publications including the "South Bend Tribune" and "Clouds Across the Stars," an international book. She also is a licensed Realtor and clinical certified dental assistant. King holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Ball State University.

Related Articles

How to Write a Problem and Purpose Statement in Nursing...

How to Write a Rationale for Your Dissertation

How to Format a Quantitative Research Design

How to Develop a Problem Statement

How to Form a Theoretical Study of a Dissertation

How to Develop a Research Proposal

How to Write a Research Paper Proposal

How to Measure Qualitative Research

How to Write a Sample Topic Proposal

How to Write a Research Methodology

Independent vs. Dependent Variables in Sociology

How to Write a Research Proposal for College

How to Write an Ethnographic Case Study

How to Write Research Objectives

What Is a Preliminary Research Design?

How to Write a Ph.D. Concept Paper

How to Design and Conduct Mixed Method Research

List of Topics for Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Definition of Data Interpretation

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

21 Research Objectives Examples (Copy and Paste)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

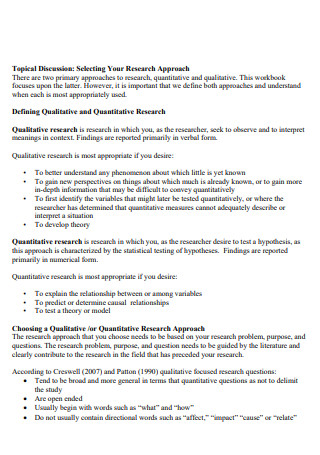

Research objectives refer to the definitive statements made by researchers at the beginning of a research project detailing exactly what a research project aims to achieve.

These objectives are explicit goals clearly and concisely projected by the researcher to present a clear intention or course of action for his or her qualitative or quantitative study.

Research objectives are typically nested under one overarching research aim. The objectives are the steps you’ll need to take in order to achieve the aim (see the examples below, for example, which demonstrate an aim followed by 3 objectives, which is what I recommend to my research students).

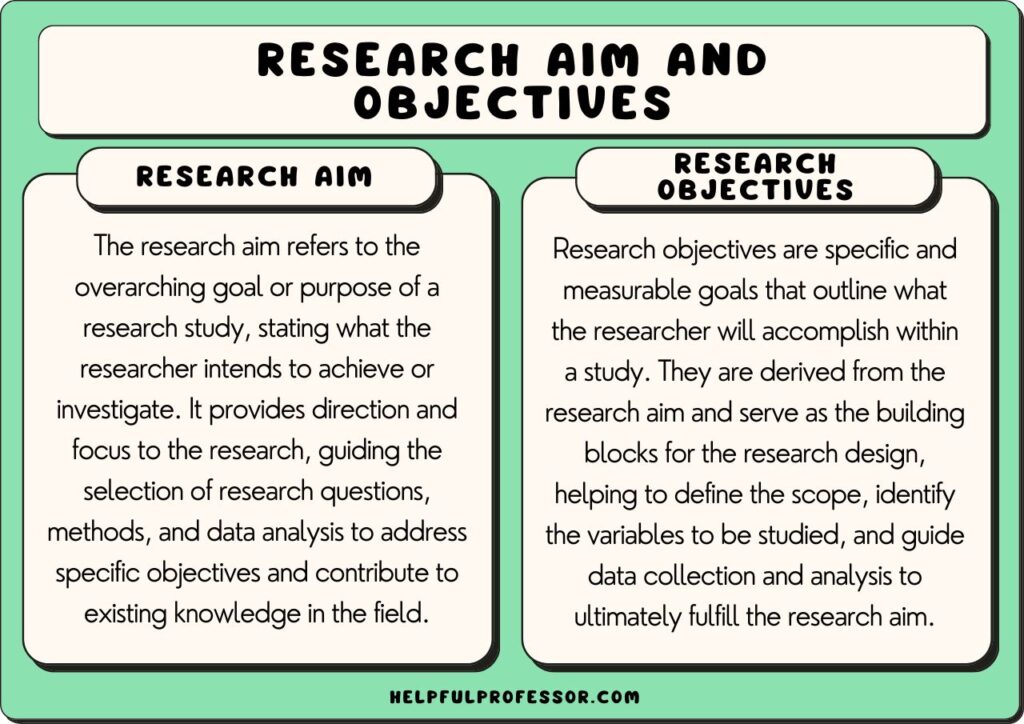

Research Objectives vs Research Aims

Research aim and research objectives are fundamental constituents of any study, fitting together like two pieces of the same puzzle.

The ‘research aim’ describes the overarching goal or purpose of the study (Kumar, 2019). This is usually a broad, high-level purpose statement, summing up the central question that the research intends to answer.

Example of an Overarching Research Aim:

“The aim of this study is to explore the impact of climate change on crop productivity.”

Comparatively, ‘research objectives’ are concrete goals that underpin the research aim, providing stepwise actions to achieve the aim.

Objectives break the primary aim into manageable, focused pieces, and are usually characterized as being more specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Examples of Specific Research Objectives:

1. “To examine the effects of rising temperatures on the yield of rice crops during the upcoming growth season.” 2. “To assess changes in rainfall patterns in major agricultural regions over the first decade of the twenty-first century (2000-2010).” 3. “To analyze the impact of changing weather patterns on crop diseases within the same timeframe.”

The distinction between these two terms, though subtle, is significant for successfully conducting a study. The research aim provides the study with direction, while the research objectives set the path to achieving this aim, thereby ensuring the study’s efficiency and effectiveness.

How to Write Research Objectives

I usually recommend to my students that they use the SMART framework to create their research objectives.

SMART is an acronym standing for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. It provides a clear method of defining solid research objectives and helps students know where to start in writing their objectives (Locke & Latham, 2013).

Each element of this acronym adds a distinct dimension to the framework, aiding in the creation of comprehensive, well-delineated objectives.

Here is each step:

- Specific : We need to avoid ambiguity in our objectives. They need to be clear and precise (Doran, 1981). For instance, rather than stating the objective as “to study the effects of social media,” a more focused detail would be “to examine the effects of social media use (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) on the academic performance of college students.”

- Measurable: The measurable attribute provides a clear criterion to determine if the objective has been met (Locke & Latham, 2013). A quantifiable element, such as a percentage or a number, adds a measurable quality. For example, “to increase response rate to the annual customer survey by 10%,” makes it easier to ascertain achievement.

- Achievable: The achievable aspect encourages researchers to craft realistic objectives, resembling a self-check mechanism to ensure the objectives align with the scope and resources at disposal (Doran, 1981). For example, “to interview 25 participants selected randomly from a population of 100” is an attainable objective as long as the researcher has access to these participants.

- Relevance : Relevance, the fourth element, compels the researcher to tailor the objectives in alignment with overarching goals of the study (Locke & Latham, 2013). This is extremely important – each objective must help you meet your overall one-sentence ‘aim’ in your study.

- Time-Bound: Lastly, the time-bound element fosters a sense of urgency and prioritization, preventing procrastination and enhancing productivity (Doran, 1981). “To analyze the effect of laptop use in lectures on student engagement over the course of two semesters this year” expresses a clear deadline, thus serving as a motivator for timely completion.

You’re not expected to fit every single element of the SMART framework in one objective, but across your objectives, try to touch on each of the five components.

Research Objectives Examples

1. Field: Psychology

Aim: To explore the impact of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in college students.

- Objective 1: To compare cognitive test scores of students with less than six hours of sleep and those with 8 or more hours of sleep.

- Objective 2: To investigate the relationship between class grades and reported sleep duration.

- Objective 3: To survey student perceptions and experiences on how sleep deprivation affects their cognitive capabilities.

2. Field: Environmental Science

Aim: To understand the effects of urban green spaces on human well-being in a metropolitan city.

- Objective 1: To assess the physical and mental health benefits of regular exposure to urban green spaces.

- Objective 2: To evaluate the social impacts of urban green spaces on community interactions.

- Objective 3: To examine patterns of use for different types of urban green spaces.

3. Field: Technology

Aim: To investigate the influence of using social media on productivity in the workplace.

- Objective 1: To measure the amount of time spent on social media during work hours.

- Objective 2: To evaluate the perceived impact of social media use on task completion and work efficiency.

- Objective 3: To explore whether company policies on social media usage correlate with different patterns of productivity.

4. Field: Education

Aim: To examine the effectiveness of online vs traditional face-to-face learning on student engagement and achievement.

- Objective 1: To compare student grades between the groups exposed to online and traditional face-to-face learning.

- Objective 2: To assess student engagement levels in both learning environments.

- Objective 3: To collate student perceptions and preferences regarding both learning methods.

5. Field: Health

Aim: To determine the impact of a Mediterranean diet on cardiac health among adults over 50.

- Objective 1: To assess changes in cardiovascular health metrics after following a Mediterranean diet for six months.

- Objective 2: To compare these health metrics with a similar group who follow their regular diet.

- Objective 3: To document participants’ experiences and adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

6. Field: Environmental Science

Aim: To analyze the impact of urban farming on community sustainability.

- Objective 1: To document the types and quantity of food produced through urban farming initiatives.

- Objective 2: To assess the effect of urban farming on local communities’ access to fresh produce.

- Objective 3: To examine the social dynamics and cooperative relationships in the creating and maintaining of urban farms.

7. Field: Sociology

Aim: To investigate the influence of home offices on work-life balance during remote work.

- Objective 1: To survey remote workers on their perceptions of work-life balance since setting up home offices.

- Objective 2: To conduct an observational study of daily work routines and family interactions in a home office setting.

- Objective 3: To assess the correlation, if any, between physical boundaries of workspaces and mental boundaries for work in the home setting.

8. Field: Economics

Aim: To evaluate the effects of minimum wage increases on small businesses.

- Objective 1: To analyze cost structures, pricing changes, and profitability of small businesses before and after minimum wage increases.

- Objective 2: To survey small business owners on the strategies they employ to navigate minimum wage increases.

- Objective 3: To examine employment trends in small businesses in response to wage increase legislation.

9. Field: Education

Aim: To explore the role of extracurricular activities in promoting soft skills among high school students.

- Objective 1: To assess the variety of soft skills developed through different types of extracurricular activities.

- Objective 2: To compare self-reported soft skills between students who participate in extracurricular activities and those who do not.

- Objective 3: To investigate the teachers’ perspectives on the contribution of extracurricular activities to students’ skill development.

10. Field: Technology

Aim: To assess the impact of virtual reality (VR) technology on the tourism industry.

- Objective 1: To document the types and popularity of VR experiences available in the tourism market.

- Objective 2: To survey tourists on their interest levels and satisfaction rates with VR tourism experiences.

- Objective 3: To determine whether VR tourism experiences correlate with increased interest in real-life travel to the simulated destinations.

11. Field: Biochemistry

Aim: To examine the role of antioxidants in preventing cellular damage.

- Objective 1: To identify the types and quantities of antioxidants in common fruits and vegetables.

- Objective 2: To determine the effects of various antioxidants on free radical neutralization in controlled lab tests.

- Objective 3: To investigate potential beneficial impacts of antioxidant-rich diets on long-term cellular health.

12. Field: Linguistics

Aim: To determine the influence of early exposure to multiple languages on cognitive development in children.

- Objective 1: To assess cognitive development milestones in monolingual and multilingual children.

- Objective 2: To document the number and intensity of language exposures for each group in the study.

- Objective 3: To investigate the specific cognitive advantages, if any, enjoyed by multilingual children.

13. Field: Art History

Aim: To explore the impact of the Renaissance period on modern-day art trends.

- Objective 1: To identify key characteristics and styles of Renaissance art.

- Objective 2: To analyze modern art pieces for the influence of the Renaissance style.

- Objective 3: To survey modern-day artists for their inspirations and the influence of historical art movements on their work.

14. Field: Cybersecurity

Aim: To assess the effectiveness of two-factor authentication (2FA) in preventing unauthorized system access.

- Objective 1: To measure the frequency of unauthorized access attempts before and after the introduction of 2FA.

- Objective 2: To survey users about their experiences and challenges with 2FA implementation.

- Objective 3: To evaluate the efficacy of different types of 2FA (SMS-based, authenticator apps, biometrics, etc.).

15. Field: Cultural Studies

Aim: To analyze the role of music in cultural identity formation among ethnic minorities.

- Objective 1: To document the types and frequency of traditional music practices within selected ethnic minority communities.

- Objective 2: To survey community members on the role of music in their personal and communal identity.

- Objective 3: To explore the resilience and transmission of traditional music practices in contemporary society.

16. Field: Astronomy

Aim: To explore the impact of solar activity on satellite communication.

- Objective 1: To categorize different types of solar activities and their frequencies of occurrence.

- Objective 2: To ascertain how variations in solar activity may influence satellite communication.

- Objective 3: To investigate preventative and damage-control measures currently in place during periods of high solar activity.

17. Field: Literature

Aim: To examine narrative techniques in contemporary graphic novels.

- Objective 1: To identify a range of narrative techniques employed in this genre.

- Objective 2: To analyze the ways in which these narrative techniques engage readers and affect story interpretation.

- Objective 3: To compare narrative techniques in graphic novels to those found in traditional printed novels.

18. Field: Renewable Energy

Aim: To investigate the feasibility of solar energy as a primary renewable resource within urban areas.

- Objective 1: To quantify the average sunlight hours across urban areas in different climatic zones.

- Objective 2: To calculate the potential solar energy that could be harnessed within these areas.

- Objective 3: To identify barriers or challenges to widespread solar energy implementation in urban settings and potential solutions.

19. Field: Sports Science

Aim: To evaluate the role of pre-game rituals in athlete performance.

- Objective 1: To identify the variety and frequency of pre-game rituals among professional athletes in several sports.

- Objective 2: To measure the impact of pre-game rituals on individual athletes’ performance metrics.

- Objective 3: To examine the psychological mechanisms that might explain the effects (if any) of pre-game ritual on performance.

20. Field: Ecology

Aim: To investigate the effects of urban noise pollution on bird populations.

- Objective 1: To record and quantify urban noise levels in various bird habitats.

- Objective 2: To measure bird population densities in relation to noise levels.

- Objective 3: To determine any changes in bird behavior or vocalization linked to noise levels.

21. Field: Food Science

Aim: To examine the influence of cooking methods on the nutritional value of vegetables.

- Objective 1: To identify the nutrient content of various vegetables both raw and after different cooking processes.

- Objective 2: To compare the effect of various cooking methods on the nutrient retention of these vegetables.

- Objective 3: To propose cooking strategies that optimize nutrient retention.

The Importance of Research Objectives

The importance of research objectives cannot be overstated. In essence, these guideposts articulate what the researcher aims to discover, understand, or examine (Kothari, 2014).

When drafting research objectives, it’s essential to make them simple and comprehensible, specific to the point of being quantifiable where possible, achievable in a practical sense, relevant to the chosen research question, and time-constrained to ensure efficient progress (Kumar, 2019).

Remember that a good research objective is integral to the success of your project, offering a clear path forward for setting out a research design , and serving as the bedrock of your study plan. Each objective must distinctly address a different dimension of your research question or problem (Kothari, 2014). Always bear in mind that the ultimate purpose of your research objectives is to succinctly encapsulate your aims in the clearest way possible, facilitating a coherent, comprehensive and rational approach to your planned study, and furnishing a scientific roadmap for your journey into the depths of knowledge and research (Kumar, 2019).

Kothari, C.R (2014). Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques . New Delhi: New Age International.

Kumar, R. (2019). Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners .New York: SAGE Publications.

Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management review, 70 (11), 35-36.

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance . New York: Routledge.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Free Research Purpose Statement Generator for Students

What is a good research purpose statement? Below, you’ll find its definition, writing tips, and some excellent examples. Keep reading!

- ️✅ How to Use the Tool

- ️🔬 Research Purpose Statement Basics

- ️🖊️ How to Write It

- ️💪 Tips on Writing a Strong Statement

- ️🤩 Free Examples

- ️🔗 References

✅ Research Purpose Statement Generator: How to Use

A research purpose statement is an essential part of any research. It helps you stay focused on the problem you’re investigating and also catches your reader’s attention.

However, it might take some time and energy to develop a solid purpose statement. Our goal is to make your studies more enjoyable with the help of our tool!

Here’s how our research purpose statement generator works:

- Choose the type of your research.

- Choose a verb that best describes your study’s purpose.

- Type in your research group, the object of your study , and what is impacted by it.

- Provide the information on the place and time of the research.

- Describe the research group 2 if necessary.

🔬 Research Purpose Statement: the Basics

Research purpose definition.

A research purpose statement describes your research’s reason, goal, and process. It explains what the research explores, how it does it, and where it takes place. A research purpose is simple and concise. It is usually placed at the end of the introduction.

The Importance of Research Purpose Statement

A research purpose statement helps your reader understand what the research will be about and explains the significance of your study . It also helps you avoid distractions and focus on the relevant information needed for the research.

Research Purpose Statement vs. Thesis Statement

The purpose of both types of statements is to let readers know what to expect from your work. But here’s a difference:

- A thesis statement "> A thesis statement makes a claim and predicts how the essay will unfold.

- A purpose statement explains what the research will be about, how it will be conducted, and where it will take place.

🖊️ How to Write a Research Purpose Statement

Need to write your research purpose statement but don’t know where to start? We’ve got your back! Here, we explain step by step how to make a solid purpose statement for your research.

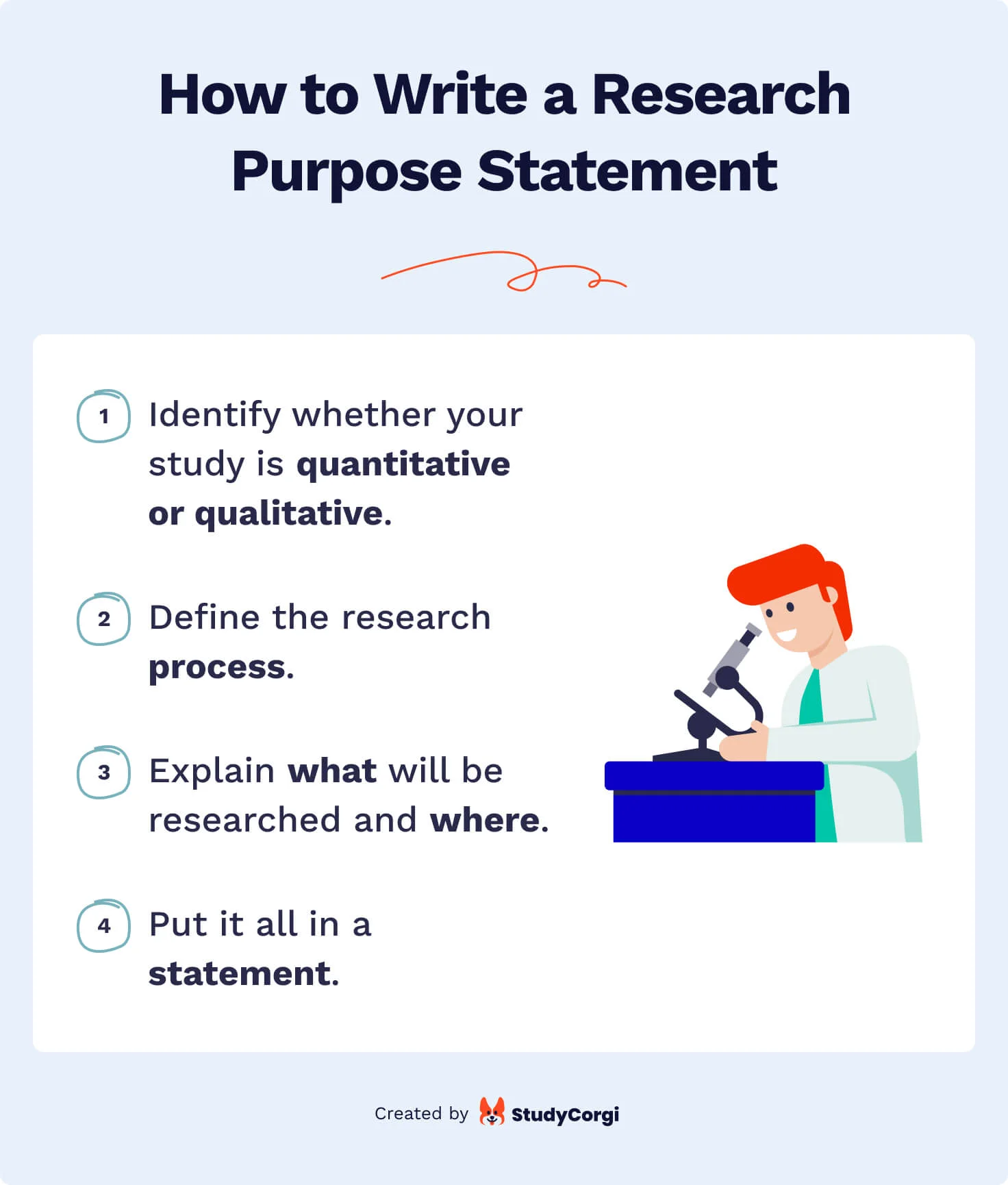

Step 1 – Identify Whether Your Study Is Quantitative or Qualitative

Research purpose statements vary depending on the type of research. One in a quantitative paper should focus on specific numbers. A qualitative research purpose statement focuses on precise intent. You can start your statement with, “The purpose of this qualitative/quantitative research is…”

Step 2 – Define the Research Process

Explain the methods you are going to use in your research. What data or instruments are you going to use? By explaining your research process , you will make it easier for the reader to understand what to expect from your work.

Step 3 – Explain What Will Be Researched and Where It Will Take Place

Try to provide enough background information for your reader. Where is the research going to take place? Does the reader need to know about the population of that location?

Step 4 – Make a Statement

Now, put everything together and create your statement.

💪 Tips on Making a Great Research Purpose Statement

- Write your research purpose statement together with the problem statement . This will ensure that the purpose is connected to the problem.

- Write only one purpose statement. Your purpose should cover the entire research, so there’s no need to divide it into smaller parts.

- Avoid including too many details. The purpose statement should be easy to understand. Otherwise, your reader might get lost.

- Use simple words. Don’t go overboard with creativity because it might distract you from the problem.

🤩 Research Purpose Statement Examples

Want some inspiration for your research purpose statement? Here are some of the best examples to help you out!

Quantitative research:

This quantitative research aims to compare the academic results of the students attending online classes and those attending traditional classes regarding exam scores and GPA.

The purpose above is short and clear. It lets the reader know what the research is going to be about.

Qualitative research:

The purpose of this qualitative research is to understand how mental health education impacts the academic achievements of high school students.

This purpose is also short and precise. It doesn’t have too many details but is straight to the point.

We hope this article was helpful. Remember that you can always use our research purpose statement generator for free. Make sure to check our APA title page generator and research question maker too!

❓ Research Purpose Statement FAQ

❓ what is purpose statement in research.

A purpose statement explains to your reader what your research will be about. It should describe the goal, methods, and place of your study. It is usually at the end of the introduction part.

❓ How to write a purpose statement for a research paper?

To write a purpose statement for a research paper, you should follow these steps:

- Identify the type of your research

- Explain the process of the research

- Describe who or what you are going to research and where it takes place

- Finally, put it all together

❓ What is a purpose statement in research example?

“The purpose of this quantitative research is to compare the academic results of the students attending online classes and those attending traditional classes regarding exam scores and GPA.” This quantitative research purpose statement is short and clear. It only provides a little information but lets the reader know what to expect from the research.

❓ Where does the purpose statement go in a research paper?

A purpose statement is usually at the end of the introductory part of your research. Since its function is to tell your reader what to expect from your paper, you should place it before your study’s main body.

Updated: Aug 23rd, 2024

🔗 References

- Research Paper Purpose Statement Examples: Your Dictionary

- Thesis and Purpose Statements: University of Wisconsin

- Writing Effective Purpose Statements: University of Washington

- Importance of a Purpose Statement in Research: The Classroom

Stating the Obvious: Writing Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

During the process of writing your thesis or dissertation, you might suddenly realize that your research has inherent flaws. Don’t worry! Virtually all projects contain restrictions to your research. However, being able to recognize and accurately describe these problems is the difference between a true researcher and a grade-school kid with a science-fair project. Concerns with truthful responding, access to participants, and survey instruments are just a few of examples of restrictions on your research. In the following sections, the differences among delimitations, limitations, and assumptions of a dissertation will be clarified.

Delimitations

Delimitations are the definitions you set as the boundaries of your own thesis or dissertation, so delimitations are in your control. Delimitations are set so that your goals do not become impossibly large to complete. Examples of delimitations include objectives, research questions, variables, theoretical objectives that you have adopted, and populations chosen as targets to study. When you are stating your delimitations, clearly inform readers why you chose this course of study. The answer might simply be that you were curious about the topic and/or wanted to improve standards of a professional field by revealing certain findings. In any case, you should clearly list the other options available and the reasons why you did not choose these options immediately after you list your delimitations. You might have avoided these options for reasons of practicality, interest, or relativity to the study at hand. For example, you might have only studied Hispanic mothers because they have the highest rate of obese babies. Delimitations are often strongly related to your theory and research questions. If you were researching whether there are different parenting styles between unmarried Asian, Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic women, then a delimitation of your study would be the inclusion of only participants with those demographics and the exclusion of participants from other demographics such as men, married women, and all other ethnicities of single women (inclusion and exclusion criteria). A further delimitation might be that you only included closed-ended Likert scale responses in the survey, rather than including additional open-ended responses, which might make some people more willing to take and complete your survey. Remember that delimitations are not good or bad. They are simply a detailed description of the scope of interest for your study as it relates to the research design. Don’t forget to describe the philosophical framework you used throughout your study, which also delimits your study.

Limitations

Limitations of a dissertation are potential weaknesses in your study that are mostly out of your control, given limited funding, choice of research design, statistical model constraints, or other factors. In addition, a limitation is a restriction on your study that cannot be reasonably dismissed and can affect your design and results. Do not worry about limitations because limitations affect virtually all research projects, as well as most things in life. Even when you are going to your favorite restaurant, you are limited by the menu choices. If you went to a restaurant that had a menu that you were craving, you might not receive the service, price, or location that makes you enjoy your favorite restaurant. If you studied participants’ responses to a survey, you might be limited in your abilities to gain the exact type or geographic scope of participants you wanted. The people whom you managed to get to take your survey may not truly be a random sample, which is also a limitation. If you used a common test for data findings, your results are limited by the reliability of the test. If your study was limited to a certain amount of time, your results are affected by the operations of society during that time period (e.g., economy, social trends). It is important for you to remember that limitations of a dissertation are often not something that can be solved by the researcher. Also, remember that whatever limits you also limits other researchers, whether they are the largest medical research companies or consumer habits corporations. Certain kinds of limitations are often associated with the analytical approach you take in your research, too. For example, some qualitative methods like heuristics or phenomenology do not lend themselves well to replicability. Also, most of the commonly used quantitative statistical models can only determine correlation, but not causation.

Assumptions

Assumptions are things that are accepted as true, or at least plausible, by researchers and peers who will read your dissertation or thesis. In other words, any scholar reading your paper will assume that certain aspects of your study is true given your population, statistical test, research design, or other delimitations. For example, if you tell your friend that your favorite restaurant is an Italian place, your friend will assume that you don’t go there for the sushi. It’s assumed that you go there to eat Italian food. Because most assumptions are not discussed in-text, assumptions that are discussed in-text are discussed in the context of the limitations of your study, which is typically in the discussion section. This is important, because both assumptions and limitations affect the inferences you can draw from your study. One of the more common assumptions made in survey research is the assumption of honesty and truthful responses. However, for certain sensitive questions this assumption may be more difficult to accept, in which case it would be described as a limitation of the study. For example, asking people to report their criminal behavior in a survey may not be as reliable as asking people to report their eating habits. It is important to remember that your limitations and assumptions should not contradict one another. For instance, if you state that generalizability is a limitation of your study given that your sample was limited to one city in the United States, then you should not claim generalizability to the United States population as an assumption of your study. Statistical models in quantitative research designs are accompanied with assumptions as well, some more strict than others. These assumptions generally refer to the characteristics of the data, such as distributions, correlational trends, and variable type, just to name a few. Violating these assumptions can lead to drastically invalid results, though this often depends on sample size and other considerations.

Click here to cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Copyright © 2024 PhDStudent.com. All rights reserved. Designed by Divergent Web Solutions, LLC .

3+ SAMPLE Qualitative Research Statement in PDF

Qualitative research statement, 3+ sample qualitative research statement, what is a qualitative research statement, types of qualitative research statement, steps in writing a qualitative research statement, how to write a qualitative research proposal, what are the 5 qualitative research types, how do quantitative and qualitative methods differ, what are mixed methods research, what’s the difference between validity and reliability, what is the purpose of hypothesis testing.

Qualitative Descriptive Study Research Statement

Qualitative Research Purpose Statement

Qualitative Project Research Statement

Sample Qualitative Research Statement

1. include the problem to be solved, 2. framework for theoretical considerations, 3. methods of investigation, 4. appendices and references are included, share this post on your network, you may also like these articles, bank statement.

A Bank Statement is a crucial document that provides a summary of your banking activity over a specific period. It includes deposits, withdrawals, transfers, and the current balance. Understanding…

Research Problem Statement

Creating a clear and compelling Research Problem Statement is essential for any successful research project. This guide provides a step-by-step approach to formulating an effective problem statement, including key…

browse by categories

- Questionnaire

- Description

- Reconciliation

- Certificate

- Spreadsheet

Information

- privacy policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Business Templates

- Sample Statements

FREE 3+ Qualitative Research Statement Samples [ Purpose, Problem, Positionality ]