Short Fiction Forms: Novella, Novelette, Short Story, and Flash Fiction Defined

When it comes to fiction, a short narrative can be found in many forms, from a slim book to just a few sentences. Short fiction forms can generally be broken down based on word count. The guidelines in this article can help you understand how short fiction is commonly defined. There are, however, no exact universal rules that everyone agrees upon, especially when it comes to flash fiction. When submitting your work for publication or contest entry, you should follow the specifications or submission guidelines. With that in mind, here's a list of short fiction forms and their definitions.

A work of fiction between 20,000 and 49,999 words is considered a novella. Once a book hits the 50,000 word mark, it is generally considered a novel. (However, a standard novel is around 80,000 words, so books between 50,000 to 79,999 words may be called short novels.) A novella is the longest of the short fiction forms, granting writers freedom for an expanded story, descriptions, and cast of characters, but still keeping the condensed intensity of a short story. Modern trends generally seem to be moving away from publishing novellas. Novellas are more commonly published as eBooks in specific genres, especially romance, sci-fi, and fantasy.

A novelette falls in the range of 7,500 to 19,999 words. The term once implied a book that had a romantic or sentimental theme, but today a novelette can be any genre. While some writers still use the term novelette, others might prefer to simply call it a short novella or long short story. Like the novella, a novelette may be difficult to pitch to an agent, but might work better as an eBook in niche genres.

Short story

Short stories fall in the range of about 1,000 to 7,499 words. Due to its brevity, the narrative in a short story is condensed, usually only focusing on a single incident and a few characters at most. A short story is self-contained and is not part of a series. When a number of stories are written as a series it's called a story sequence. Short stories are commonly published in magazines and anthologies, or as collections by an individual author.

Flash fiction

Flash fiction is generally used as an umbrella term that refers to super short fiction of 1,000 words or less, but still provides a compelling story with a plot (beginning, middle, and end), character development, and usually a twist or surprise ending. The exact length of flash fiction isn't set, but is determined by the publisher.

Types of flash fiction

There are many new terms that further define flash fiction. For example, terms like short shorts and sudden fiction are used to describe longer forms of flash fiction that are more than 500 words, while microfiction refers to the shortest forms of flash fiction, at 300 to 400 words or less. Here are some of the types of flash fiction:

Sudden fiction/Short short stories

The terms sudden fiction and short short stories refer to longer pieces of flash fiction, around 750 to 1,000 words. However, the definition varies and may include pieces up to 2,000 words, such as in the series that helped popularize the form, Sudden Fiction and New Sudden Fiction .

Postcard fiction

Postcard fiction is just what it sounds like—a story that could fit on a postcard. It's typically around 250 words, but could be as much as 500 or as few as 25. An image often accompanies the text to create the feeling of looking at a postcard, with the reader turning it over to read the inscription on the back.

Microfiction/Nanofiction

Microfiction and nanofiction describe the shortest forms of flash fiction, including stories that are 300 words or less. Microfiction includes forms such as drabble, dribble, and six-word stories.

Drabble is a story of exactly 100 words (not including the title). Just because the form is short doesn't mean you can skimp on the basics of a good story. It should have a beginning, middle, and end, and include conflict and resolution. You can read examples of drabbles at 100WordStory.org .

Dribble/Mini-saga

When writing a drabble isn't challenging enough, you can try your hand at writing a dribble, which is a story told in exactly 50 words.

Six-word stories

Ready to boil down a story and squeeze out its essence? Try writing a six-word story. It's not easy, but it's possible to write a complete story with conflict and resolution in six words, according to flash fiction enthusiasts. The most well-know example of a six-word story, often misattributed to Ernest Hemingway , is, "For sale: baby shoes, never worn." The story evokes deep emotion, causing the reader to ponder the circumstances that brought the character to post the advertisement. You can read more examples of six-word stories on Narrative Magazine's website (with a free account), which are more carefully selected, or you can browse user-submitted stories on Reddit . Some authors also write flash nonfiction, composing six-word memoirs .

Short Fiction Challenge

Now that you are more familiar with some of the forms of short fiction, why not give it a try? Flash fiction can provide a helpful change of pace and help fine tune your writing skills. The limited word count forces you to consider the weight of every action, every character, and every word. Writing good short fiction takes time and practice. Sometimes it's the shortest pieces that can take the longest to write.

- Literary Fiction

© Copyright 2018 Author Learning Center. All Rights Reserved

Definition of Prose

What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it.

Common Examples of First Prose Lines in Well-Known Novels

The first prose line of a novel is significant for the writer and reader. This opening allows the writer to grab the attention of the reader, set the tone and style of the work, and establish elements of setting , character, point of view , and/or plot . For the reader, the first prose line of a novel can be memorable and inspire them to continue reading. Here are some common examples of first prose lines in well-known novels:

Examples of Famous Lines of Prose

Prose is a powerful literary device in that certain lines in literary works can have a great effect on readers in revealing human truths or resonating as art through language. Well-crafted, memorable prose evokes thought and feeling in readers. Here are some examples of famous lines of prose:

Types of Prose

Difference between prose and poetry.

Many people consider prose and poetry to be opposites as literary devices . While that’s not quite the case, there are significant differences between them. Prose typically features natural patterns of speech and communication with grammatical structure in the form of sentences and paragraphs that continue across the lines of a page rather than breaking. In most instances, prose features everyday language.

Writing a Prose Poem

Prose edda vs. poetic edda, examples of prose in literature, example 1: the grapes of wrath by john steinbeck.

A large drop of sun lingered on the horizon and then dripped over and was gone, and the sky was brilliant over the spot where it had gone, and a torn cloud, like a bloody rag, hung over the spot of its going. And dusk crept over the sky from the eastern horizon, and darkness crept over the land from the east.

Example 2: This Is Just to Say by William Carlos Williams

I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold

Example 3: Harrison Bergeron by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

The year was 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

Synonyms of Prose

Post navigation.

What Is Prose In Literature? 7 Top Prose Examples

What is prose in literature ? Discover our expert guide with helpful prose examples and learn about the most impactful prose you can find in the literary world today.

Prose is any writing in an ordinary language without a rhyme scheme or formal metrical structure . Prose can take many forms, including short stories, poetry, and essays. When completing a prose piece, the organization of the words is essential to create a path the reader can follow. Still, there’s no need for lines to be of equal length or consider alliteration or other literary devices.

Prose follows the standard format of using sentences to build paragraphs. There’s a good chance your favorite novel, poem, or speech was written in prose format, as prose is the most common form of writing. When editing for grammar, we also recommend taking the time to improve the readability score of a piece of writing before publishing or submitting it. You might also be wondering, what is an iambic pentameter ?

Different Types Of Prose

Short stories, prose poetry, heroic prose, prose fiction and nonfictional prose, newspaper articles, key elements of prose literature, 1. great expectations by charles dickens, 2. the catcher in the rye by j.d. salinger, 3. the masque of the red death by edgar allan poe, 4. the hunger games by suzanne collins, 5. a tree grows in brooklyn by betty smith, 6. as you like it by william shakespeare, 7. the war of the worlds by h.g. wells.

While prose is common and easy to find in literature, there are several categories into which prose can fall. Read our guide with writing advice from authors to build your writing confidence.

Many authors write in prose for short stories, allowing their characters to explain the story to the reader in ordinary language. Writing in prose can make it easier for readers to understand literary work. The familiar, everyday speech that prose-style short stories take on allows the author to focus on telling the story from their character’s point of view, helping readers understand their story’s world.

It can be challenging for poets to convey their ideas when they’re working to stick to a particular rhyme scheme, worrying about line breaks, or struggling to fit their work into a certain number of stanzas. Writing prose, free verse, and poetry allows poets to share their ideas in a way that makes sense to them and their readers rather than following a format set up by someone else.

This type of prose poem is meant to be passed down through oral tradition. Heroic prose tells the story of a key figure in a culture’s present or history and helps to ensure that a culture’s values are passed from one generation to the next.

The difference between prose fiction and nonfictional prose is simple: fiction tells stories created in the author’s imagination, while nonfiction prose tells stories of events in real life. Both types of prose can follow the natural flow of speech, making it easy for the reader to follow the storyline.

Newspaper articles are often written in prose, with the reporter telling the story as it unfolded in real life, using language that follows how people usually speak.

Check out our canonical literature explainer.

When writing prose, it’s essential to consider the key elements that will help bring your narrative to life for your reader. Whether you’re writing an article, a short story, a novel, a poem, or other types of writing, paying attention to the key elements of prose will allow your reader to imagine the world you’re creating with your writing entirely. Key elements of prose include:

- Character : Character development helps readers understand who plays a role in your story. While main character development is vital, you’ll also want to flesh out the other characters in your prose to help your readers understand how they interact. Be sure to help your reader see how your character grows and changes over time. There’s no need for your characters to stay stagnant–growth is a normal part of life, and working to show your readers how their experiences affect their personality and outlook on life can help them seem more real.

- Setting: Your reader needs to fully be able to picture the world you’re creating in your writing. Pay attention to what you see when you imagine your character’s world, and take plenty of time to describe their environment to your reader. Whether you’re describing a place that currently exists or a world that only exists in your imagination, developing the setting of your story can help your readers feel like they’re there, going through each experience you describe for your characters.

- Plot: Your plot is your storyline, and you’ll want to work carefully to be sure that your plot follows a clear path. When developing your plot, keep an eye out for plot holes, such as a character struggling with money suddenly being able to go on vacation. The more realistic your plot, the better your reader can identify with your story.

- Point of View: Decide whether you want to tell your story from a first-person, second-person, or third-person point of view. Many prose writers use the first-person point of view, allowing the characters to speak directly to the reader.

- Mood: What feeling do you want your readers to have as they enjoy your story? Perhaps you want them to feel inspired, or you want them to feel conflicted as they consider the hard truths that your character has to face as they grow and learn. The setting, character development, vocabulary choices, and writing style can all help your reader feel the mood you’re creating with your writing.

Examples Of Prose In Literature

In this passage, Dickens expertly conveys one of the many difficulties of growing up–the fear of becoming someone you do not want to be. Many growing adults cling to the safety of youth, only to be overcome by the difficulties of adulthood that lead them to participate in the same behaviors they despise. Dickens’ prose writing style makes this passage relatable to readers, as they can feel the main character, Pip, baring his soul.

“Suffering has been stronger than all other teaching, and has taught me to understand what your heart used to be. I have been bent and broken, but – I hope – into a better shape.” – Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

One of the many reasons Catcher is renowned as a classic is Salinger’s ability to convey protagonist Holden Caulfield’s thoughts to the reader clearly (but not concisely). Caulfield shares his story like many people find their inner voice working–taking tangents and roundabouts, exploring new ideas, and returning to old ideas. As a result, many readers feel they know Caulfield by the end of the novel, even though he’s a fictional character created by Salinger’s imagination.

“The mark of the immature man is that he wants to die nobly for a cause, while the mark of the mature man is that he wants to live humbly for one.” J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

Known for creating macabre worlds that infuse readers’ nightmares, Poe’s ability to use everyday language to paint a clear picture continues to be envied by writers. In Masque, Poe helps the reader to understand the extravagance of the party he attends. The author’s detailed description leaves the reader with no questions about the party, allowing them to picture precisely how the scene appeared as partygoers met their brutal final fate.

“There are chords in the hearts of the most reckless which cannot be touched without emotion, even by the utterly lost, to whom life and death are equally jests, there are matters of which no jest can be made.” Edgar Allan Poe , The Masque of the Red Death

Moviegoers and book lovers alike are familiar with the plight of Katniss, the heroine of The Hunger Games series. In this passage, near the beginning of the series, readers get to know their protagonist and relate to her, similar to getting to know a real-life friend.

Katniss describes struggles in school, family issues, and trying to hide her true feelings, all shared by many. Collins’ use of prose makes it simple for readers to put themselves in the shoes of Katniss.

“And then he gives me a smile that just seems so genuinely sweet with just the right touch of shyness that unexpected warmth rushes through me.” Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games

The coming-of-age tale of a young New York girl is a testament to the strength of the human spirit. Smith expertly makes the reader feel as if the tree is a character in the story and returns to this metaphor several times throughout the novel.

The book’s protagonist, Francie Nolan, shares characteristics with the trees that survive in the harsh Brooklyn environment. In this novel, the protagonist does not speak directly to the reader. However, Smith writes so readers feel like they’re listening to a friend describe their life and hardships.

“Look at everything always as though you were seeing it either for the first or last time: Thus is your time on earth filled with glory.” Betty Smith, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

![short stories novels and essays are all forms of prose A Tree Grows in Brooklyn [75th Anniversary Ed] (Perennial Classics)](https://becomeawritertoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/41HH0qsYzBL._SL500_.webp)

Shakespeare is one of the most prominent writers of all time, so he has many great examples of prose in literature . Skillfully using language to underscore social distinctions in his plays, he strategically uses prose and verse to show social status in As You Like It .

Characters from lower social classes typically communicate using prose, which is used to portray their unpretentious and straightforward mannerisms. In contrast, the upper class uses rhythmic verse with poetic form and descriptive language. The deliberate use of prose and verse creates a stark contrast between the characters, allowing the reader to understand the social status and characteristics portrayed.

“Time travels at different speeds for different people. I can tell you who time strolls for, who it trots for, who it gallops for, and who it stops cold for.” William Shakespeare , As You Like It

H.G. Wells is often called the “father of science fiction” due to his immense success as an author. His works span various genres, but he is best known for his speculative novels with compelling narrative and vivid characters.

In War of the World, Wells employs meticulously detailed prose to show the terrifying invasion by Martians. The captivating story is shown through descriptive prose that blends fiction and reality into one mesmerizing tale. To learn more, check out our guide on stream of consciousness poetry!

“Few people realize the immensity of vacancy in which the dust of the material universe swims.” H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds

Understanding Prose in Literature: A Comprehensive Guide

Defining prose, types of prose, prose vs. verse, prose styles, narrative style, descriptive style, expository style, argumentative style, literary devices in prose, foreshadowing, analyzing prose, close reading, theme and message, notable authors and their prose, jane austen, ernest hemingway, toni morrison, prose in different cultures, greek prose, indian prose, japanese prose.

Prose in literature is a fascinating topic that has captured the attention of readers and writers for centuries. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the different aspects of prose and how it shapes the world of literature. By understanding prose, you will be able to appreciate the beauty of written language and enhance your own writing skills. So, let's dive into the captivating world of prose in literature!

Prose is a form of written language that follows a natural, everyday speech pattern. It is the way we communicate in writing without adhering to the strict rules of poetry or verse. In literature, prose encompasses a wide range of written works, from novels and short stories to essays and articles. To better understand prose in literature, let's look at the different types of prose and how it compares to verse.

There are several types of prose in literature, each serving a unique purpose and offering a different reading experience:

- Fiction: Imaginative works, such as novels and short stories, that tell a story.

- Non-fiction: Informative works, such as essays, articles, and biographies, that present facts and real-life experiences.

- Drama: Plays and scripts written in prose form, often featuring dialogue and stage directions.

- Prose poetry: A hybrid form that combines elements of prose and poetry, creating a more fluid and expressive style.

By exploring these types of prose, you can better appreciate the versatility and depth of prose in literature.

Prose and verse are two distinct forms of written language, each with its own characteristics and purposes. Here's a quick comparison:

- Prose: Written in a natural, conversational style, prose uses sentences and paragraphs to convey meaning. It is the most common form of writing and can be found in novels, essays, articles, and other forms of literature.

- Verse: Written in a structured, rhythmic pattern, verse often uses stanzas, rhyme, and meter to create a more musical quality. It is most commonly found in poetry and song lyrics.

Understanding the differences between prose and verse can help you appreciate the unique qualities of each form and how they contribute to the richness of literature.

Just as there are different types of prose, there are also various prose styles that authors use to convey their ideas and stories. These styles can be categorized into four main groups:

The narrative style tells a story by presenting events in a sequence, typically involving characters and a plot. This style is commonly used in novels, short stories, and biographies. Some key features of the narrative style include:

- Chronological or non-chronological structure

- Use of dialogue and description

- Focus on characters, their actions, and motivations

- Development of a plot, consisting of a beginning, middle, and end

By using the narrative style, authors can create engaging stories that draw readers in and make them feel a part of the experience.

The descriptive style focuses on painting a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. This style is used to provide detailed information and create a strong sensory experience for the reader. Some key features of the descriptive style include:

- Use of sensory language, such as sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch

- Adjectives and adverbs to enhance descriptions

- Figurative language, such as similes and metaphors, to create vivid imagery

- Attention to detail and setting

By mastering the descriptive style, authors can transport readers to new worlds and enrich their understanding of the subject matter.

The expository style is used to explain, inform, or describe a topic. This style is commonly found in textbooks, essays, and articles. Some key features of the expository style include:

- Clear, concise language

- Logical organization of information

- Use of examples, facts, and statistics to support the main idea

- An objective, unbiased tone

By employing the expository style, authors can effectively convey information and help readers gain a deeper understanding of a subject.

The argumentative style is used to persuade or convince the reader of a certain viewpoint. This style is often found in opinion pieces, essays, and debates. Some key features of the argumentative style include:

- A clear, well-defined thesis statement

- Logical organization of arguments and evidence

- Use of facts, statistics, and examples to support the thesis

- Addressing and refuting opposing viewpoints

- A persuasive, confident tone

By mastering the argumentative style, authors can effectively present their opinions and persuade readers to consider their perspective.

Understanding these different prose styles can help you appreciate the diverse ways authors use language to convey their ideas and enhance your own writing abilities.

Authors use various literary devices to enrich their prose and make it more engaging for the reader. These devices help create an emotional connection, build suspense, or bring out deeper meanings in the text. Let's explore some of the most commonly used literary devices in prose:

Imagery is the use of vivid and descriptive language to create a picture in the reader's mind. This technique appeals to the five senses and can make a piece of writing more immersive and memorable. Some examples of imagery include:

- Visual imagery: describing the appearance of a character or setting

- Auditory imagery: describing sounds, such as the rustling of leaves or the roar of a crowd

- Olfactory imagery: describing smells, such as the scent of fresh-baked cookies or the aroma of a garden

- Gustatory imagery: describing tastes, such as the sweetness of a ripe fruit or the bitterness of a cup of coffee

- Tactile imagery: describing textures and physical sensations, such as the softness of a blanket or the warmth of the sun

By using imagery, authors can create a richer, more engaging experience for the reader.

Foreshadowing is a technique used to hint at events that will occur later in the story. This can create suspense, build anticipation, and keep the reader engaged. Foreshadowing can be subtle or more direct and can take various forms, such as:

- Character dialogue or thoughts

- Symbolism or motifs

- Setting or atmosphere

- Actions or events that mirror or prefigure future events

By incorporating foreshadowing, authors can create a sense of mystery and intrigue that keeps readers turning the pages.

Allusion is a reference to a well-known person, event, or work of art, literature, or music. This technique allows authors to make connections and add depth to their writing without explicitly stating the reference. Allusions can serve various purposes, such as:

- Creating a shared understanding between the author and the reader

- Establishing a cultural, historical, or literary context

- Adding layers of meaning or symbolism

- Providing a subtle commentary or critique

By using allusion, authors can enhance their prose and engage readers with shared knowledge and cultural references.

These are just a few examples of the many literary devices that authors use to enrich their prose in literature. By understanding and recognizing these techniques, you can deepen your appreciation of the written word and perhaps even add some of these tools to your own writing repertoire.

Analyzing prose in literature involves closely examining the text to gain a deeper understanding of the author's intentions, themes, and techniques. This process can help you appreciate the nuances of the writing and uncover new insights. Let's explore some approaches to analyzing prose:

Close reading is a method of carefully examining the text to identify its structure, themes, and literary devices. This approach involves paying attention to details such as:

- Word choice and diction

- Sentence structure and syntax

- Imagery and figurative language

- Characterization and dialogue

- Setting and atmosphere

By closely examining these elements, you can gain a deeper understanding of the author's intentions and the text's overall meaning.

Identifying the theme or central message of a piece of prose is another important aspect of analysis. A theme is a recurring idea, topic, or subject that runs through the text. Some common themes in literature include:

- Love and relationships

- Identity and self-discovery

- Power and authority

- Conflict and resolution

- Nature and the environment

To identify the theme of a piece of prose, consider the overall message or lesson that the author is trying to convey. Look for patterns, motifs, and symbols that support this message. Understanding the theme can help you better appreciate the author's intentions and the text's significance.

By employing these approaches to analyzing prose in literature, you can deepen your understanding of the text and enhance your appreciation of the author's craft. Whether you're studying a classic novel or a contemporary short story, these skills will help you unlock the richness and complexity of the written word.

Throughout history, numerous authors have made significant contributions to the world of prose in literature. Their unique writing styles and innovative approaches to storytelling have left an indelible mark on the literary landscape. Let's take a closer look at some notable authors and their distinctive prose:

Jane Austen, an English author from the early 19th century, is well-known for her witty and satirical prose. Her novels often center on themes of love, marriage, and social class in the Georgian era. Examples of her work include Pride and Prejudice , Sense and Sensibility , and Emma . Austen's prose is characterized by:

- Sharp wit and humor

- Observant descriptions of characters and their social interactions

- Realistic dialogue that reveals the personalities and motivations of her characters

- Insightful commentary on societal norms and expectations of her time

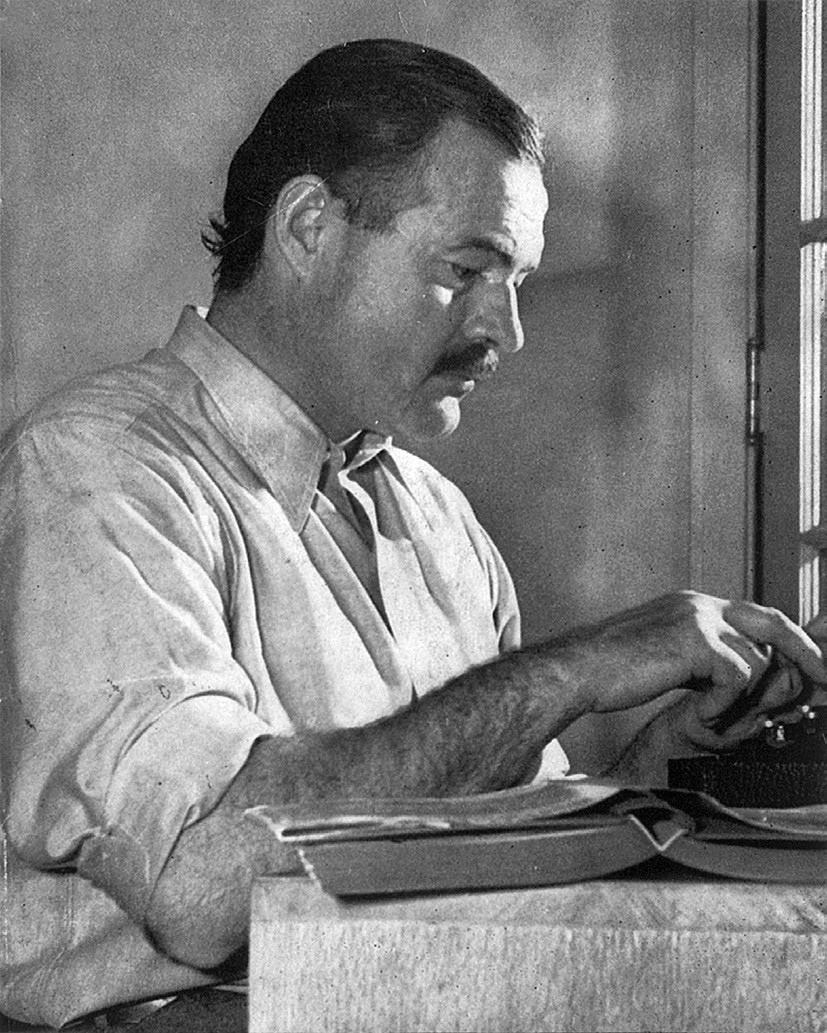

Ernest Hemingway, an American author from the 20th century, is celebrated for his distinctive writing style that has had a lasting impact on prose in literature. His works often explore themes of war, love, and the human condition, such as in A Farewell to Arms , The Old Man and the Sea , and For Whom the Bell Tolls . Hemingway's prose is characterized by:

- Simple, direct language and short sentences

- An emphasis on action and external events

- Understated emotions and a focus on the physical world

- A "less is more" approach that leaves room for reader interpretation

Toni Morrison, an American author and Nobel laureate, is renowned for her powerful, evocative prose that delves into the complexities of human relationships and the African American experience. Notable works include Beloved , Song of Solomon , and The Bluest Eye . Morrison's prose is characterized by:

- Rich, lyrical language and vivid imagery

- Complex characters and multi-layered narratives

- Explorations of race, gender, and identity

- A strong sense of voice and emotional intensity

These authors, among many others, have each left their unique imprint on the realm of prose in literature. By studying their works and understanding their techniques, we can better appreciate the diverse ways in which writers can use prose to convey their stories and ideas.

Prose in literature is a global phenomenon, with each culture bringing its own distinctive style, themes, and literary traditions to the table. Let's explore how prose has developed and evolved in some cultures around the world:

Ancient Greek prose has had a profound influence on Western literature. Spanning various genres such as philosophy, history, and drama, Greek prose is known for its intellectual depth and stylistic sophistication. Key features of Greek prose include:

- Rhetorical devices like repetition, parallelism, and antithesis

- Emphasis on logic, reason, and argumentation

- Rich vocabulary and complex sentence structures

- Notable authors like Plato, Aristotle, and Herodotus

Indian prose in literature spans thousands of years and numerous languages, with each region and time period contributing its own flavor to the mix. Indian prose is often characterized by:

- Epic tales and religious texts, such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana

- Folk tales, fables, and parables that convey moral lessons

- Ornate and poetic language, with a focus on imagery and symbolism

- Notable authors like Rabindranath Tagore, R. K. Narayan, and Arundhati Roy

Japanese prose in literature is known for its elegance, subtlety, and attention to detail. Spanning various genres such as poetry, drama, and fiction, Japanese prose often explores themes of nature, human emotion, and the passage of time. Key features of Japanese prose include:

- Haiku and other poetic forms that emphasize simplicity and precision

- Descriptions of the natural world and the changing seasons

- Understated emotions and a focus on the inner lives of characters

- Notable authors like Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, and Haruki Murakami

By examining the diverse range of prose in literature from various cultures, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the many ways in which authors use language to tell stories, express ideas, and convey the human experience.

If you found this blog post intriguing and want to delve deeper into writing from your memories, be sure to check out Charlie Brogan's workshop, ' Writing From Memory - Part 1 .' This workshop will guide you through the process of tapping into your memories and transforming them into captivating stories. Don't miss this opportunity to enhance your writing skills and unleash your creativity!

Live classes every day

Learn from industry-leading creators

Get useful feedback from experts and peers

Best deal of the year

* billed annually after the trial ends.

*Billed monthly after the trial ends.

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Prose

I. What is a Prose?

Prose is just non-verse writing. Pretty much anything other than poetry counts as prose: this article, that textbook in your backpack, the U.S. Constitution, Harry Potter – it’s all prose. The basic defining feature of prose is its lack of line breaks:

In verse, the line ends

when the writer wants it to, but in prose

you just write until you run out of room and then start a new line.

Unlike most other literary devices , prose has a negative definition : in other words, it’s defined by what it isn’t rather than by what it is . (It isn’t verse.) As a result, we have to look pretty closely at verse in order to understand what prose is.

II. Types of Prose

Prose usually appears in one of these three forms.

You’re probably familiar with essays . An essay makes some kind of argument about a specific question or topic. Essays are written in prose because it’s what modern readers are accustomed to.

b. Novels/short stories

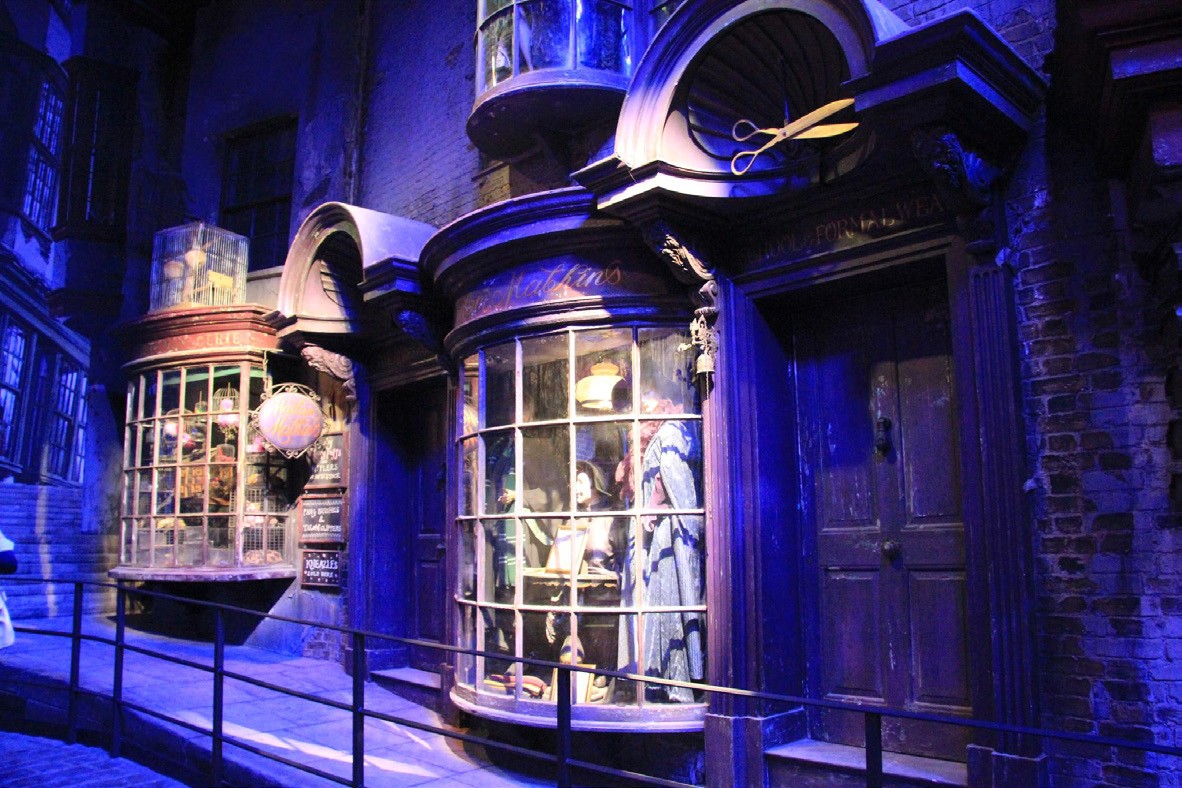

When you set out to tell a story in prose, it’s called a novel or short story (depending on length). Stories can also be told through verse, but it’s less common nowadays. Books like Harry Potter and the Fault in Our Stars are written in prose.

c. Nonfiction books

If it’s true, it’s nonfiction. Essays are a kind of nonfiction, but not the only kind. Sometimes, a nonfiction book is just written for entertainment (e.g. David Sedaris’s nonfiction comedy books), or to inform (e.g. a textbook), but not to argue. Again, there’s plenty of nonfiction verse, too, but most nonfiction is written in prose.

III. Examples of Prose

The Bible is usually printed in prose form, unlike the Islamic Qur’an, which is printed in verse. This difference suggests one of the differences between the two ancient cultures that produced these texts: the classical Arabs who first wrote down the Qur’an were a community of poets, and their literature was much more focused on verse than on stories. The ancient Hebrews, by contrast, were more a community of storytellers than poets, so their holy book was written in a more narrative prose form.

Although poetry is almost always written in verse, there is such a thing as “prose poetry.” Prose poetry lacks line breaks, but still has the rhythms of verse poetry and focuses on the sound of the words as well as their meaning. It’s the same as other kinds of poetry except for its lack of line breaks.

IV. The Importance of Prose

Prose is ever-present in our lives, and we pretty much always take it for granted. It seems like the most obvious, natural way to write. But if you stop and think, it’s not totally obvious. After all, people often speak in short phrases with pauses in between – more like lines of poetry than the long, unbroken lines of prose. It’s also easier to read verse, since it’s easier for the eye to follow a short line than a long, unbroken one.

For all of these reasons, it might seem like verse is actually a more natural way of writing! And indeed, we know from archaeological digs that early cultures usually wrote in verse rather than prose. The dominance of prose is a relatively modern trend.

So why do we moderns prefer prose? The answer is probably just that it’s more efficient! Without line breaks, you can fill the entire page with words, meaning it takes less paper to write the same number of words. Before the industrial revolution, paper was very expensive, and early writers may have given up on poetry because it was cheaper to write prose.

V. Examples of Prose in Literature

Although Shakespeare was a poet, his plays are primarily written in prose. He loved to play around with the difference between prose and verse, and if you look closely you can see the purpose behind it: the “regular people” in his plays usually speak in prose – their words are “prosaic” and therefore don’t need to be elevated. Heroic and noble characters , by contrast, speak in verse to highlight the beauty and importance of what they have to say.

Flip open Moby-Dick to a random page, and you’ll probably find a lot of prose. But there are a few exceptions: short sections written in verse. There are many theories as to why Herman Melville chose to write his book this way, but it probably was due in large part to Shakespeare. Melville was very interested in Shakespeare and other classic authors who used verse more extensively, and he may have decided to imitate them by including a few verse sections in his prose novel.

VI. Examples of Prose in Pop Culture

Philosophy has been written in prose since the time of Plato and Aristotle. If you look at a standard philosophy book, you’ll find that it has a regular paragraph structure, but no creative line breaks like you’d see in poetry. No one is exactly sure why this should be true – after all, couldn’t you write a philosophical argument with line breaks in it? Some philosophers, like Nietzsche, have actually experimented with this. But it hasn’t really caught on, and the vast majority of philosophy is still written in prose form.

In the Internet age, we’re very familiar with prose – nearly all blogs and emails are written in prose form. In fact, it would look pretty strange if this were not the case!

Imagine if you had a professor

who wrote class emails

in verse form, with odd

line breaks in the middle

of the email.

VII. Related Terms

Verse is the opposite of prose: it’s the style of writing

that has line breaks.

Most commonly used in poetry, it tends to have rhythm and rhyme but doesn’t necessarily have these features. Anything with artistic line breaks counts as verse.

18 th -century authors saw poetry as a more elevated form of writing – it was a way of reaching for the mysterious and the heavenly. In contrast, prose was for writing about ordinary, everyday topics. As a result, the adjective “prosaic” (meaning prose-like) came to mean “ordinary, unremarkable.”

Prosody is the pleasing sound of words when they come together. Verse and prose can both benefit from having better prosody, since this makes the writing more enjoyable to a reader.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Prose: A Literary Genre

As a literary genre, prose refers to the use of ordinary language and sentence structure in written or spoken form without metrical patterns.

Etymology of Prose

Table of Contents

The word “prose” derives from the Latin term “prosa oratio,” which means “straightforward speech” or “direct discourse.”

It originated in the late Middle English period around the 14th century. It was intended to describe things or places in written or spoken language, lacking the metrical and rhythmic structure found in poetry. Characterized by its natural flow and organization, it becomes suitable for narrative, essays, and everyday communication.

Meanings of Prose

- Definition: It is a form of written or spoken language not structured into regular meter or rhyme.

- Natural Flow: It has a natural flow of language, lacking the formal structure found in poetry.

- Everyday Speech: It relies on the use of everyday speech and conversational tone.

- Literary Genres: It includes a wide range of literary genres, including novels, short stories, essays, and journalism.

- Versatility: It is the most common form of written language and is used in various contexts, including fiction, nonfiction, and academic writing.

- Contrast with Poetry: Contrasted with poetry, it lacks the use of meter, rhyme, and formal elements.

- Emphasis: While poetry often emphasizes sound and rhythm, prose prioritizes meaning and clarity.

Prose in Grammar

Grammatically, “prose” is a singular noun, and it takes a singular verb. However, when referring to multiple pieces, the plural form is not commonly used. Instead, the plural is indicated by using a plural verb, as in “The essays are written in prose.”

Definition of Prose

As a literary genre , it refers to the use of ordinary language and sentence structure in written or spoken form, without the incorporation of metrical or rhythmic patterns typically found in poetry. It serves as a means to convey information, ideas, and stories in a straightforward and clear way, emphasizing clarity and natural expression.

Types of Prose

Here are some common types as follows.

| It is found in novels, novellas, short stories, etc. It tells stories with characters, settings, and plots. | by Harper Lee | |

| It is found in biographies, essays, etc. Explores topics, often with research and analysis. | by Rebecca Skloot | |

| It is used in poetry to convey ideas without rhyme or meter. May have line breaks and poetic language but lacks formal structure. | Prose poems by Charles Baudelaire | |

| It is used in technical writing (manuals, reports) with a focus on clarity and precision. | User manual for a smartphone | |

| It is used in academic writing (research papers, dissertations) with research and analysis, written formally and objectively. | A scholarly article in a scientific journal | |

| It is used in journalism (news articles, features) focusing on clarity and engagement, often informing readers. | A news article reporting on a current event such as by Robert Fisk | |

| It is used in creative writing (personal essays, memoirs) with elements of fiction or poetry but lacking their formal structure. | by Stephen King | |

| It is used in letters and written correspondence, often with a conversational tone and personal anecdotes. | Example: Letters exchanged between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera | |

| It is found in autobiographies and memoirs, focusing on the author’s own life experiences. | by Anne Frank | |

| It is used in screenplays for film and TV, including dialogue, stage directions, and scene descriptions. | : A screenplay for a popular movie |

Literary Examples of Prose

However, it must be kept in mind that the literary type of prose is different. It is mostly in narrative or descriptive shape, emphasizing the type of writing it is used in. Here are some examples of narrative form.

| Literary Prose | is a literary example, with the story being told in prose through the eyes of the protagonist, Scout Finch. It focuses on issues of racial injustice and social inequality in the American South during the 1930s. | |

| Literary Prose | explores the decadence and excess of the Jazz Age in America, characterized by Fitzgerald’s lyrical and evocative style. His language brings to life the glamour and disillusionment of the era, making it another example of in literature. | |

| Literary Prose | This classic novel shows a distinctive style that reflects the voice and perspective of its teenage narrator, Holden Caulfield. Salinger’s prose is marked by its colloquial and informal tone, capturing the slang and idiom of the youth culture of the 1950s. | |

| Literary Prose | uses prose to explore the trauma of slavery and its aftermath in the lives of African Americans. Morrison’s style is characterized by its lyricism and poetic quality, giving voice to the experiences of the characters in a powerful and evocative way, making it a significant example of literary prose. | |

| Minimalist Prose | is a post-apocalyptic novel written in a spare and minimalist style, reflecting the stark and desolate landscape of the story. McCarthy’s style features short, declarative sentences and an absence of punctuation, creating a sense of urgency and immediacy in the narrative, demonstrating the use of minimalist prose. |

In each of these examples, the prose style of the author is an essential part of the literary experience. The language used by the author serves to convey the themes and ideas of the work in a way that is both evocative and engaging for the reader.

Suggested Readings

- Strunk, William, and E.B. White. The Elements of Style. Fourth Edition, Longman, 1999.

- Zinsser, William. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction. HarperCollins, 2006.

- Tufte, Virginia A. Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style. Graphics Press, 2006.

- Williams, Joseph M. Style: Lessons in Clarity and Grace. Twelfth Edition, Pearson, 2017.

- Pinker, Steven. The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. Viking, 2014.

- King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Pocket Books, 2000.

- Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers . Vintage, 1991.

- Brooks, Cleanth, and Robert Penn Warren. Understanding Fiction. Third Edition, Prentice Hall, 1959.

- Lamott, Anne. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life . Anchor Books, 1995.

Related posts:

- Onomatopoeia: A Literary Device

One thought on “Prose: A Literary Genre”

- Pingback: Personification: Using and Critiquing - English Studies

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, definition of prose, common examples of prose, significance of prose in literature, examples of prose in literature.

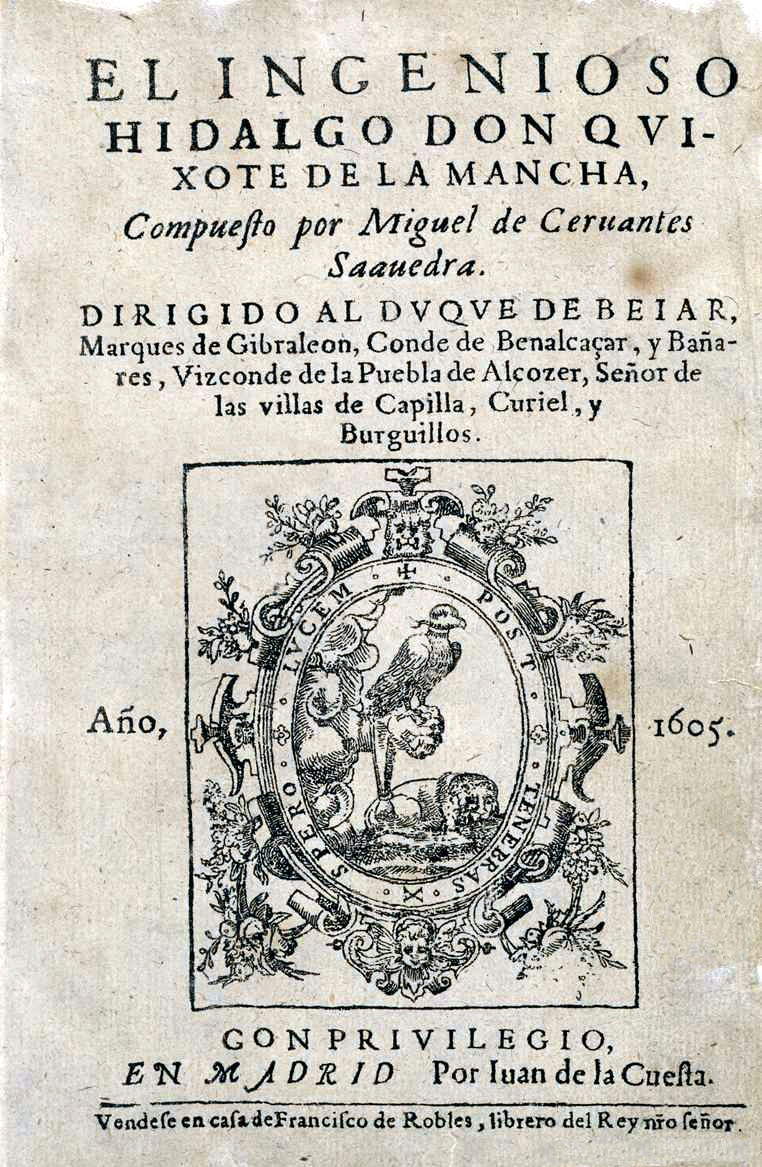

I shall never be fool enough to turn knight-errant. For I see quite well that it’s not the fashion now to do as they did in the olden days when they say those famous knights roamed the world.

( Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes)

The ledge, where I placed my candle, had a few mildewed books piled up in one corner; and it was covered with writing scratched on the paint. This writing, however, was nothing but a name repeated in all kinds of characters, large and small—Catherine Earnshaw, here and there varied to Catherine Heathcliff, and then again to Catherine Linton. In vapid listlessness I leant my head against the window, and continued spelling over Catherine Earnshaw—Heathcliff—Linton, till my eyes closed; but they had not rested five minutes when a glare of white letters started from the dark, as vivid as spectres—the air swarmed with Catherines; and rousing myself to dispel the obtrusive name, I discovered my candle wick reclining on one of the antique volumes, and perfuming the place with an odour of roasted calf-skin.

( Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë)

“I never know you was so brave, Jim,” she went on comfortingly. “You is just like big mans; you wait for him lift his head and then you go for him. Ain’t you feel scared a bit? Now we take that snake home and show everybody. Nobody ain’t seen in this kawn-tree so big snake like you kill.”

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing, in fact he disliked it, but he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton.

( The Sun also Rises by Ernest Hemingway)

Ernest Hemingway wrote his prose in a very direct and straightforward manner. This excerpt from The Sun Also Rises demonstrates the directness in which he wrote–there is no subtlety to the narrator’s remark “Do not think I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title.”

The Lighthouse was then a silvery, misty-looking tower with a yellow eye, that opened suddenly, and softly in the evening. Now— James looked at the Lighthouse. He could see the white-washed rocks; the tower, stark and straight; he could see that it was barred with black and white; he could see windows in it; he could even see washing spread on the rocks to dry. So that was the Lighthouse, was it? No, the other was also the Lighthouse. For nothing was simply one thing. The other Lighthouse was true too.

And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking. . .ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: “It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish.”

Test Your Knowledge of Prose

1. Choose the best prose definition from the following statements: A. A form of communicating that uses ordinary grammar and flow. B. A piece of literature with a rhythmic structure. C. A synonym for verse. [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #1″] Answer: A is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove

A. It has a rhythmic structure. B. It contains rhymes. C. It does not use ordinary grammar. D. All of the above. [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #2″] Answer: D is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

You’re sad because you’re sad. It’s psychic. It’s the age. It’s chemical. Go see a shrink or take a pill, or hug your sadness like an eyeless doll you need to sleep.

“A Sad Child” B.

I would like to believe this is a story I’m telling. I need to believe it. I must believe it. Those who can believe that such stories are only stories have a better chance. If it’s a story I’m telling, then I have control over the ending. Then there will be an ending, to the story, and real life will come after it. I can pick up where I left off.

The Handmaid’s Tale C.

No, they whisper. You own nothing. You were a visitor, time after time climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming. We never belonged to you. You never found us. It was always the other way round.

“The Moment” [spoiler title=”Answer to Question #3″] Answer: B is the correct answer.[/spoiler]

Prose Fiction: An Introduction to the Semiotics of Narrative

(6 reviews)

Ignasi Ribó

Copyright Year: 2020

Publisher: Open Book Publishers

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by William Pendergast, Adjunct Professor/Coordinator, Bunker Hill Community College on 1/31/21

The book is a through account of the structure of narrative stories. It outlines all the elements that make a narrative successful in a critical writing sense. It defines the subject and breaks down the classic sense of drama throughout the ages... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The book is a through account of the structure of narrative stories. It outlines all the elements that make a narrative successful in a critical writing sense. It defines the subject and breaks down the classic sense of drama throughout the ages of writing. It shows the narrative in a historical context and outlines the techincal construction process. It does an excellent job looking at the science of the writing process as it pertains to the narrative. It looks at beginnings, endings, genre's, literary devices and dialogue just to name a few. The difference between Prose vs. verse, Narrative vs. drama ;Novel, novella, or short story ;Adventure, fantasy, romance, humor, science-fiction, crime, etc.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

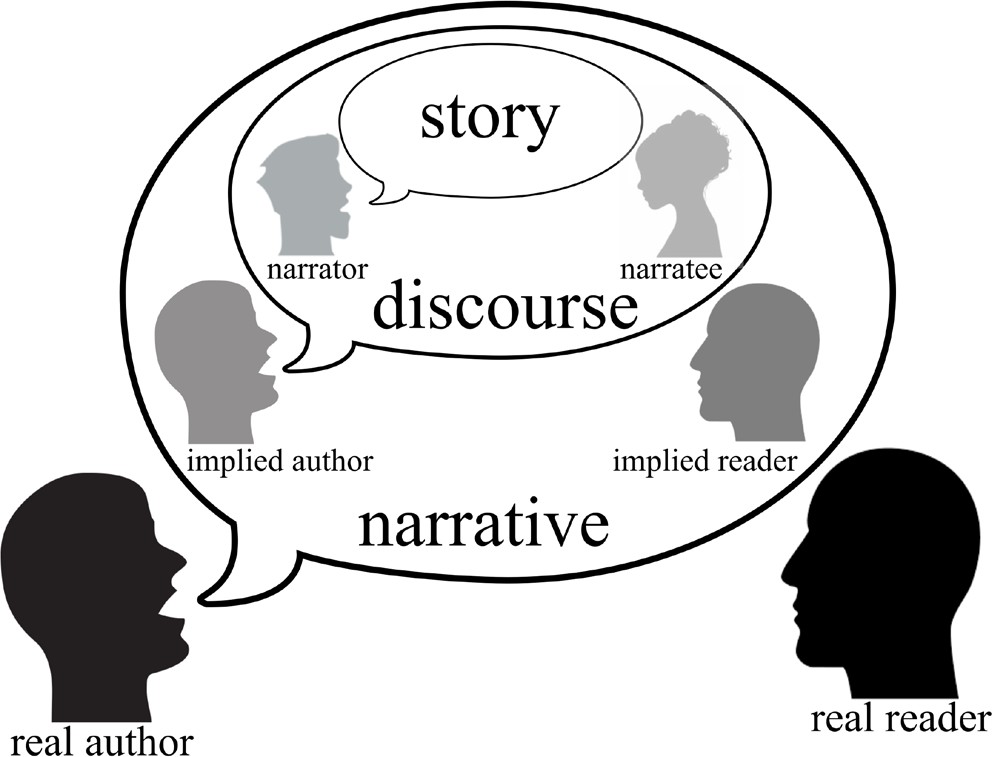

I found the books principles to be quite sound and presented in a very palatable manner. It starts with a useful definition of terms then goes into great depths to explain them. "For the purpose of this book, we will define narrative as the semiotic representation of a sequence of events, meaningfully connected by time and cause." This type of definition is a very dry and advanced level of learning as is much of the text.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

This text would be ideal for MFA creative writing program. Its explanation of the narrative is done in a way that would be more helpful to students who are becoming writers as opposed to readers. It is somewhat pedantic and really designed for an advanced student with excellent critical thinking skills. This text is not for a community college level student or even to be used with a college writing course in a typical university. This is a much more advanced text looking at the mechanics of the narrative as opposed to being a collection of stories.

Clarity rating: 4

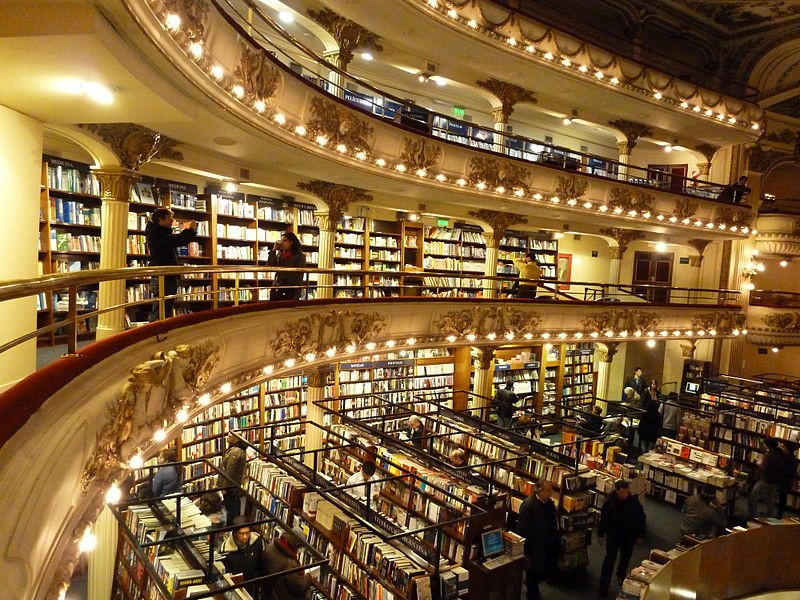

I found the text to be very clear about the manner in which it presents its material. I feel that some students would have a difficult time with some of the concepts because they would be so unfamiliar with many of the terms used. I enjoyed all the graphs and flow charts showing dramatic arcs and structure. I also enjoyed the pictures that illustrations at marked the different moments in the history of the narrative.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is absolutely consistent in the manner in which it builds the formulation of the narrative. It starts defining it, then explaining the structure, and giving different examples of narratives in various genres. Then looking at significant works throughout history then looking at all the other literary devices that make a great piece of writing to a particular genre.

Modularity rating: 3

The text works in a commutative way. You could break up some of the later chapters if you were doing a workshop on things like dialogue, symbolism, foreshadowing and building characters.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

As a text for a student studying creative writing this is organized in a wonderful manner. It builds from a technical foundation about structure and drama then looks at more of the difference between the craft of writing and the art of it. It starts with Intro which is the definition and explanation of the narrative then plot, setting, characterization, and Language, et.

Interface rating: 5

I didn't find any interface issues. I thought the text reads nicely with the right amount of graphs and charts and pictures, that I thought enhanced the lessons in the text. Many of them were graphs I will use in class today to help students understand the dramatic arc in stories. The pictures showing historical moments help give context and break up the text from reading very dry.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

I didn't notice very many errors. Some American students might be put off by the use of British English in a lot of the spelling in the text.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

The text has reference to many of the classics that will be unfamiliar to community college students and no current references really. Students who have studied writing will be familiar with the greek tragedies to the more "modern" classic examples in the text.

This is a fantastic text for a Creative Writing Student or an advanced student that is interested in becoming a writer. For the community college level student or comp student only certain chapters would be helpful to students. This is a text that an instructor could purchase and reframe the material and present to a class that isn't as advanced. I would absolutely buy this text and incorporate it into various levels of my instruction. I would take lessons and repurpose them for my developmental class and present the material as is for my creative writing students.

Reviewed by Luke Brown, Lecturer, Howard University on 1/21/21

The text approaches the question and possibilities of narrative from seven entry points (e.g., setting, language), including a general overview of major threshold concepts, terms, and approaches to narrative in the first chapter. read more

The text approaches the question and possibilities of narrative from seven entry points (e.g., setting, language), including a general overview of major threshold concepts, terms, and approaches to narrative in the first chapter.

I noticed no major issues with the quality of analysis.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

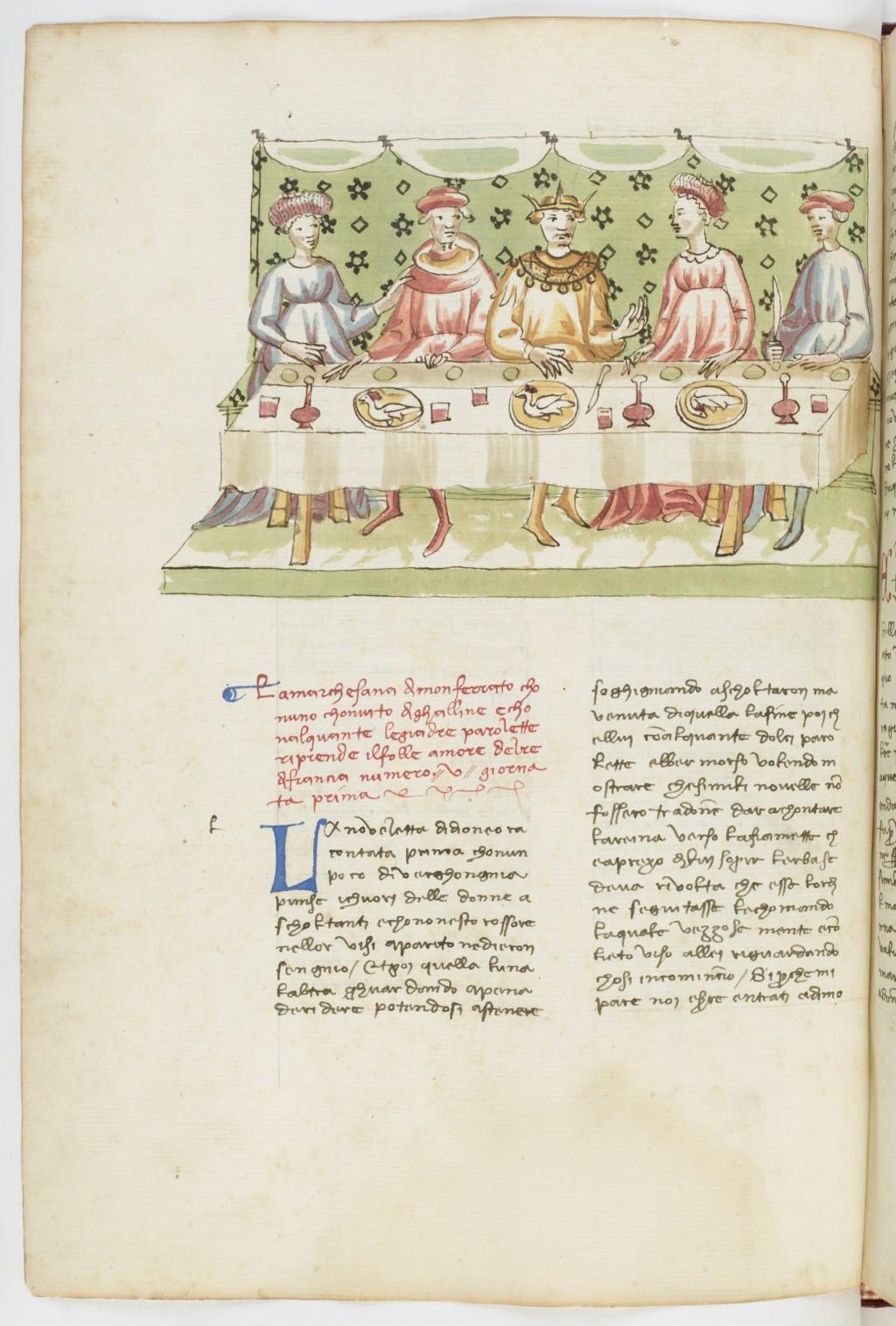

The insights of the text will likely remain viable as long as we continue to have narratives; however, it does tend towards older, Euro-centric examples (e.g., Decameron, Oedipus Rex) and would benefit from more contemporary, multicultural exemplars.

Clarity rating: 3

The text does tend towards theoretical argot in its elaborations of core ideas (e.g., real vs. implied vs. ideal reader). While still legible, students may have difficulty following the nuances of the argument without corresponding classroom discussions of the material.

Consistency rating: 4

The text offers a wide range of possible theoretical entry points and frameworks. While none are mutually exclusive, there are more than a single course could likely apply.

Modularity rating: 5

The text approaches the question and possibilities of narrative from seven entry points (e.g., setting, language), including a general overview of major threshold concepts, terms, and approaches to narrative in the first chapter. The thoughtful arrangement of the chapters and subchapters allow instructors to select small excerpts for class instruction which can be taken out of context without an overall loss in meaning.

The overall organization of the text is a clear strength. It both builds on itself over the course of its seven major divisions and each of these divisions could be engaged with independently of the others.

I had no interface issues with this text.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I noticed no major grammatical oversights.

This text could be improved by moving away from centuries-old, Eurocentric examples and incorporating a wider range of classical and contemporary texts by writers of color and other marginalized groups.

I would recommend this book as a useful supplement to introductory courses focused on creative writing or literary analysis.

Reviewed by Kathryn Evans, Professor, Bridgewater State University on 6/30/20

The book is comprehensive in that it is broad, covering the bases of narrative; however, chapters tend to be brief (students will likely appreciate this, although we might wish for more examples in the form of actual quotations). The glossary... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The book is comprehensive in that it is broad, covering the bases of narrative; however, chapters tend to be brief (students will likely appreciate this, although we might wish for more examples in the form of actual quotations). The glossary definitions are underdeveloped and do not necessarily illuminate the purposes of literary techniques discussed.

Content Accuracy rating: 2

Much of the book is accurate, although there are glaring omissions (e.g., Janet Burroway's co-authors are not listed, nor is the edition of the book noted; direct and indirect characterization are inaccurately described, as mentioned by other reviewers; the concept of genre is oversimplified; and interior monologue is not synonymous with stream of consciousness).

Many students will appreciate the references to Harry Potter throughout (a nice complement to the more historical and canonical works used to illustrate concepts and terms).

I found the book to be clearly written in general; sentences tend to be short, which many students may appreciate.

More examples in the form of quotations are used in later chapters compared to earlier chapters; it would be good to make this consistent throughout.

Most chapters, in my opinion, could be assigned out of sequence.

The book is well organized into chapters and clearly indicated sections.

The interface is impressively smooth; I found it easy to navigate. In addition, the author used a variety of images that were clear and useful (and clearly labelled).

The editing for grammar was excellent.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The examples used in the book do not represent a broad diversity of cultures / genders, but the author acknowledges that this lack of representation can be seen as an artifact of historical marginalization.

I would personally consider assigning some chapters; the author has clearly put significant time and thought into developing this book, and it is an impressive accomplishment. (On a more minor note, I would recommend that the author omit the section of the book that quotes Wikipedia, as that source is not generally regarded as being credible.)

Reviewed by Adam Mooney, Associate Lecturer, University of Massachusetts Boston on 6/30/20

The text offers tools for students to read and engage in critical discussion through a comprehensive discussion of narrative theory and narrative elements, including plot, characterization, language, theme, setting, and narration. The introduction... read more

The text offers tools for students to read and engage in critical discussion through a comprehensive discussion of narrative theory and narrative elements, including plot, characterization, language, theme, setting, and narration. The introduction serves as a succinct but expansive introduction to narrative theory, and the text is appropriate in terms of its scope. The text is admirable for its attention to concepts that get overlooked in narrative theory textbooks, including language and theme, and for its accessible and introductory-level approach, which is particularly suitable for early-level college students who may be unfamiliar with rhetorical concepts and terms for literary analysis. The text concludes with a comprehensive and effective glossary that is easy to use. Although the text lacks an index, which could have been helpful, the glossary alone was helpful as a reference tool.

The text relies well on seminal thinkers within narratology and narrative theory, and it provides accurate and objective terms for literary analysis. The text contains no notable errors.

In general, the text is relevant and up-to-date. It makes good use and offers a nice blend of seminal texts in narratology and literary theory (like Barthes and Abbott) and more recent publications on narratology and prose fiction. The text also uses 21st-century references to film and television (like Harry Potter and Game of Thrones), making it relevant and appropriate for young readers but risking potentially quick obsoletion. Indeed, the text relies almost exhaustively on Harry Potter as its "contemporary" example, despite that Harry Potter at this point is no longer relevant for many young students.

Clarity rating: 5

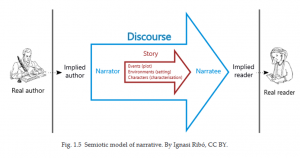

The text has a complex framework but approaches that framework with clarity and accessibility in mind as its primary goals. It explains complicated concepts in a clear and accessible manner. The text is especially successful in its essentialization—without risking the loss of integrity / depth of knowledge—of concepts like semiotic models of narratives. Indeed, one key benefit of the text, as an introduction for early-level college students, is its (self-admitted) avoidance of "overtly technical debates" within literary theory. Instead, the text prefers to streamline different key elements of narratological theory into a clear and simple framework.

The text aims to offer a "bare-bones presentation of narrative theory," and it is consistently successful in its goal to provide an easy-to-follow introduction for students without burdening them with excessive historical or theoretical details.

Modularity rating: 4

The text is designed to supplement a course but not dictate a course. It allows teachers the freedom to choose texts that they feel best reflect each chapter's main topic. Though the lack of examples for direct instruction can be seen as one drawback, the chapters are perfect for breaking into smaller sections in a course. The short length of chapters could also make for productive collaborative reading among students, where groups of students are assigned chapters and co-compose summaries or co-teach lessons based on the chapters.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The text is well-devised in its scope and structure. After a comprehensive introduction, the text moves to think about six different elements of narrative theory: plot, setting, characterization, narration, language, and theme. The first four or five chapters are meant to be the most accessible, and the final two are meant to respond to a gap in textbooks on narrative, which tend not to cover language and theme. Overall, the organization of the text is clear and helpful, and the development of chapters is logical. Within chapters, though, the progression between section--and especially the relationship between sections--is sometimes underexplained. In the introduction, for instance, the sections progress logically from “What Is Narrative?” to “Genres,” but the text fails to explain why the sections progress in this way, leaving the section on “Genres” to be under-contextualized for student readers.

Interface rating: 4

In terms of quality and clarity, the interface of this text is solid. Ribó’s own diagrams and charts are excellent—they are very helpful in explaining intricate and complex concepts, like the semiotic model of narrative. The external images used in the text are clear and attractive on the page, though the use of images and figures is somewhat disconnected from the text itself in that the images only offer superfluous perspectives that go unaddressed and underexplained in the prose. The least effective diagrams are the word clouds that begin each chapter. While these offer a succinct visualization of key terms, it is unclear where the word clouds come from, so words end up being more confusing than helpful, and they tend to capture unnecessary terms. For instance, the word "Fig" (presumably referring to "Figure") appears in the word cloud that accompanies the introduction. Elsewhere, there seems to be a mismatch between the word cloud and the chapter it accompanies. For instance, prior to Chapter 7, on theme, the word “narrative” appears at the center of the word cloud.

There are no glaring grammatical issues in the text. There may be minor grammatical errors, specifically in the use of commas, but my attention to this issue may be highlighted by my closer familiarity with grammar in U.S.-American English.

According to Ribó, this text is designed specifically for Asian students who don't have high familiarity with Western literature and literary theories in their high school education. In this sense, Ribó acknowledges in the preface the book's European focus and influence. He writes, "I have tried my best to expand the cultural range of examples in order to reflect the rich diversity of world literature. However, I am not entirely sure if I have succeeded in this effort, and most likely my explanations and examples are too heavily determined by the European tradition, which is, after all, my own." While this blind spot is acknowledged in the text, it is glaring when the text relies so heavily on a white Western canon, and it verges on cultural insensitivity in its reference to ethnicity as a “theme” in modern narrative, especially when it is only given one or two paragraphs’ worth of attention. Moreover, the text’s only substantial discussion of gender, sexuality, and ethnicity in literary theory is reduced to a few paragraphs at the end of the final chapter. Indeed, the text accounts mostly for a normative perspective; its list of "Examples of Short Stories and Novels" contains almost exclusively works by Western, and usually white, authors. Despite this book's many benefits, its lack of cultural, ethnic, racial, gender, and sexuality diversity is a glaring issue.

The text’s dedication to being a “bare-bones presentation of narrative theory”—that is, to not imposing on instructors’ choice of accompanying texts—at times makes for missed opportunities in terms of giving students accessible examples. For example, in Chapter 2, Ribó describes seven kinds of plots found often in novels and short stories. While Ribó offers specific examples—for instance, Hansel and Gretel as an example of the “overcoming the monster” plot—he misses a good opportunity to offer a modern example of the plot type as well, which would enable students to see narrative plot in older, traditional texts as aligned with plot devices that they may be more interested in or familiar with. Nonetheless, Prose Fiction is noteworthy and successful for its brief, accessible overview of important elements of narrative theory. I can very, very easily imagine this being adapted in literature classrooms smoothly and productively.

Reviewed by Thea Prieto, Adjunct Professor, Portland Community College on 6/24/20

Ribó sets out to create “a conceptual skeleton” of fiction writing, one that allows teachers to decide what readings to use in their classrooms. For a creative writing class, this means the textbook discusses various theories and craft elements of... read more

Ribó sets out to create “a conceptual skeleton” of fiction writing, one that allows teachers to decide what readings to use in their classrooms. For a creative writing class, this means the textbook discusses various theories and craft elements of fiction, as well as provides brief overviews of literary history. The textbook purposefully leaves out specific text samples, while at the same time referencing canonized or mainstream texts, so this textbook would work best as a teaching supplement. I believe introductory students would engage with the chapters regarding plot, setting, and characterization, and intermediate students would engage with the chapters regarding narration, language, and theme, as well as the glossary. Some of the terminology, concepts, and theories may be better discussed in advanced courses.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

The text is informed by an impressive number of craft anthologies and essays, though a majority of the works are by white, male writers (which Ribó acknowledges in the preface). Also, the definitions of story and discourse (Chapter 1), and the definitions of direct and indirect characterization (Chapter 4) differ from my understanding of the craft elements. This may be confusing to students, and students should be made aware of alternate definitions and/or applications.

Ribó references many canonized books, essays, and works of fiction, as well as a number of modern texts. The Harry Potter references will be hard to update, since they permeate the textbook, but the other modern references could be easily swapped out for more timely references, as well as with works by more diverse writers.

Most of the more complex concepts or terms were clearly defined in the text or in the glossary. However, there was some niche language that might ostracize beginning writers.

Consistency rating: 3

Ribó shares in the preface that he purposefully left out specific text samples and readings so the book would be a framework for teachers. The author is consistent in this way, though there are plenty of text references that still contextualize the framework.

Each chapter is broken into sections, and each section is short enough that they can be discussed in class. If the teacher is prepared to contextualize the textbook content, then the sections can be presented out of order.

Each chapter begins with theoretical knowledge, then shifts to practical applications or specific examples or topics, and concludes with a helpful summary and references page.

The eBook version was easy to navigate, and I appreciated the clickable table of contents. I would have liked specific terms to be linked to the glossary entries, and the exampled short stories/novels could be linked to their brief descriptions.

I did not notice any typos or errors.

In the preface, Ribó summarizes the dominance of white, male voices in the Western literary cannon, and he goes more in depth regarding postcolonialism and feminism in Chapter 7, particularly in terms of identity, ideology, morality, and art and politics. Early on he also explains that his examples are heavily determined by the European tradition, but considering the text’s overview of literary history and the importance of perspective in fiction writing, I would have liked to see more writers of color and writers from the LGBTQIA communities represented in the references.

The glossary of terms would be a useful Week 1 resource in my intermediate fiction courses.

Reviewed by Justina Salassi, Coordinator of General and Developmental Education/English Faculty, Central Louisiana Technical Community College on 4/29/20

The text covers its topic very well, giving relevant and easy to understand examples appropriate to second year students. As writing about literature is generally required in literature courses, it would have been helpful to provide some guidance... read more

The text covers its topic very well, giving relevant and easy to understand examples appropriate to second year students. As writing about literature is generally required in literature courses, it would have been helpful to provide some guidance on how students can apply the information provided in the text to writing topics, and how they are to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate literature through these lenses. Additionally, some of the terms and concepts (Classical poet, sign/signifier, etc.) I would not expect second year students to be familiar with were not immediately defined and are not included in the glossary.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The text is informed by seminal studies in narrative theory and related theories, as shown by the cited works. I found no inconsistencies in theory. However, the text presents direct and indirect characterization in the reverse of what is commonly taught. (In this book, indirect characterization is the explicit attribution of characteristics as told by the narrator and direct characterization is when characteristics are revealed through speech, thoughts, and actions of the character.) If this is a common misconception (of which I am not aware), the author should alert the reader of the misconception to fend off confusion between what is presented and what they might have been taught in the past.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The text uses both current and seminal sources and relevant, up to date examples.

In terms of clarity, the diction and style is accessible by students and most jargon is defined, with the exception of a few concepts and words that I feel could be more clearly defined in the text, or be included in the glossary (sign, signifier, alterity, etc.).

The framework is the theory of narratology, which is consistent throughout the text.

The text is divided logically into smaller sections, which are easily digestible. However, it would be difficult to present the chapters in a different order to students, as the chapters build on information found in previous chapters.

The organization is logical and presents concepts that build on each other. The end of chapter summaries are very useful. It would have been useful to indicate words that can be found in the glossary, or even provide links between the word and it's entry in the glossary since it is an ebook.

There were no interface issues that I noticed.

I noticed no grammatical issues. The text is very well written.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5