Academic tenure: What it is and why it matters

Professor of English, Arizona State University

Disclosure statement

George Justice is Principal of Dever Justice LLC, a higher education consulting firm.

Arizona State University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

How would you like a job that was guaranteed and allowed you to do your work as you see fit and speak your mind with no repercussions? Most people would, and that’s the idea behind academic tenure. In the following Q&A, George Justice, an English professor and author of “ How to Be a Dean ,” explains the origin of tenure and the waning protections that it affords professors who have it.

What is academic tenure?

Of all the things a university professor can achieve in their career, few are as desirable as academic tenure. Academic tenure is a system of strong job protections that virtually guarantees a university professor will never be fired or let go except in the most extreme of circumstances. A key idea is to allow faculty to speak freely – whether on campus or in public – without fear of reprisal.

Achieving tenure is not easy or quick. First, aspiring professors must secure a “tenure track” position after excelling in a Ph.D. program, followed in many cases by one or more postdoctoral fellowships. Then, in a probationary period that can last from 5 to 10 years, but which typically takes 7 years , faculty must demonstrate academic excellence in teaching, research and service to the community.

The probationary period is then followed by a year-long process during which a professor’s work is evaluated by peer faculty – both inside and outside of the university where they teach – as well as administrators at their institution.

If they succeed in getting tenure, they can be promoted to the rank of “associate professor with tenure.” But if they are denied tenure, usually it means they have one more year to build up their credentials and find employment at another college or university – or leave academia altogether to find work in a different industry.

A little less than half of all full-time faculty at colleges and universities in the U.S. – 45.1% , or 375,286 according to 2019 data – have tenure.

When did tenure first appear?

The tenure system was created in the early 20th century as a partnership between the faculty and the institutions that employ them. Faculty came to be represented nationally by the American Association of University Professors, which was founded in 1915 by two of the era’s most famous intellectuals: John Dewey and Arthur O. Lovejoy . The association wasn’t a union, although now it does help faculty unionize.

In 1940, the association teamed up with the Association of American Colleges – now the Association of American Colleges and Universities – to define tenure as a system providing “ an indefinite appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances such as financial exigency and program discontinuation.”

The real origins of the concept, though, lie in the practice of 19th-century German universities. Faculty in these universities created wide autonomy for their work on the basis of their pursuit of knowledge for its own sake . The greatest freedom and power went to those professors at the top of a rigid hierarchy.

In its 1915 “ Declaration of Principles ,” the association viewed faculty tenure as a property right and academic freedom as “essential to civilization.” “Academic freedom” includes rights both within and outside a professor’s daily work: “freedom of inquiry and research; freedom of teaching within the university or college; and freedom of extra-mural utterance and action.” The last of these means that faculty can speak up on matters of public concern outside of their specialized expertise without fear of losing their job.

Whom does it benefit?

As a job protection, tenure directly benefits college teachers. Indirectly, tenure benefits a society that thrives through the education and research that colleges and universities create .

The job protections are significant. Except in extreme circumstances, faculty who have achieved tenure can expect to be paid for teaching and research for as long as they hold their jobs. There is no retirement age. And colleges only very rarely go out of business.

Tenure’s benefits have weakened in recent years. Financially battered by the past year of COVID-19, institutions have let tenured faculty go merely with general assertions of financial stress rather than the deep crisis of “financial exigency.”

And termination “with cause” has evolved in recent years. For instance, federal law, including Title IX of the Federal Education Act , has pushed institutions to fire or force the resignation of faculty members who violate core principles of equal treatment, especially through sexual harassment of students.

Why is tenure controversial?

There are economic, political, ideological and social reasons why tenure has come under fire over the past 50 years .

From an economic perspective, higher education is big business with a big impact on the U.S. economy. State universities are among the biggest businesses. And some legislators believe universities should be treated simply like businesses. Professors would have no more job security than any other employees and could be fired without a rigorous process led by their faculty peers.

“What happens in our private sector should be applied to our universities as well,” argued Iowa State Senator Bradley Zaun , who introduced legislation that would eliminate tenure in his state’s public universities. The measure failed .

And in socially conservative parts of the country, legislators allege that professors have hypocritically violated students’ freedom of speech , including by interfering with their participation in conservative student political groups.

It’s not just from social conservatives. Colleges have suspended faculty members for using racial slurs that offend students. And faculty have sued the University of Arkansas over a revised tenure policy that would weaken protections when faculty challenge social norms.

What is its future?

Tenure continues to exist in American higher education, and surveyed provosts – the chief academic officers on their campuses – maintain support for retaining the tenure system on their campuses .

But those same academic leaders have hired increasing numbers of less expensive faculty without tenure over the past few decades.

In recent years, the percentage of tenured college teachers has fallen to 45.1% from nearly 65% in 1980 . Recent analysis suggests that if part-time faculty are included, a mere quarter of college teachers have tenure.

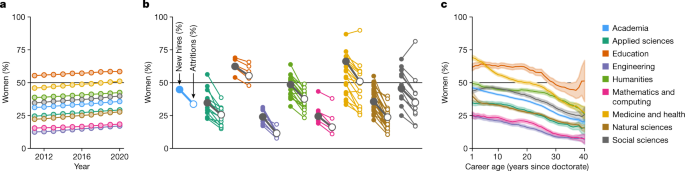

While research shows diverse faculty and peer viewpoints lead to a richer education for students , the tenured faculty are whiter and more male than the whole body of college teachers, let alone the U.S. population. Indeed, the tenured faculty has become demographically inconsistent with the students in their classrooms : 75% of college professors are white, whereas 51.1% of the population under 24 years old was non-Hispanic white in 2019.

Is the practice of academic freedom “essential to civilization”? Does it require tenure for faculty? Or is tenure a destructive job perk that limits innovation in an important service industry by entrenching faculty who may be mediocre and old-fashioned in their teaching and research? The one thing guaranteed in the future of tenure is that as long as it exists, it will continue to be controversial.

- US higher education

- College education

- Adjunct faculty

- tenure-track

Chief People & Culture Officer

Lecturer / senior lecturer in construction and project management.

Lecturer in Strategy Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Education Focused) (Identified)

Research Fellow in Dynamic Energy and Mass Budget Modelling

Communications Director

- Career Advice

Ph.D. Oversupply: The System Is the Problem

By Jonathan Malloy , Lisa Young and Loleen Berdahl

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Erhui1979/digitalvision vectors/getty images

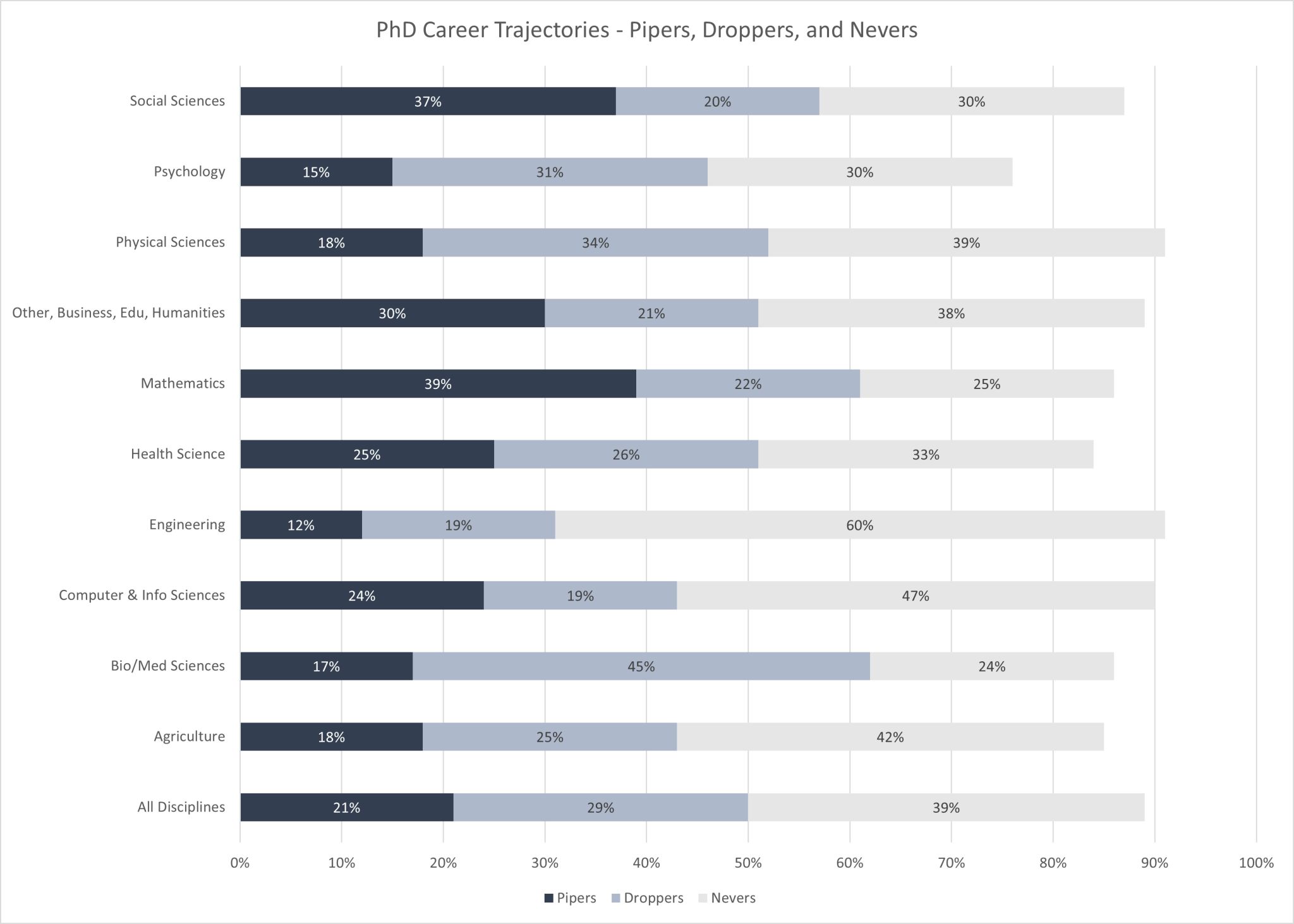

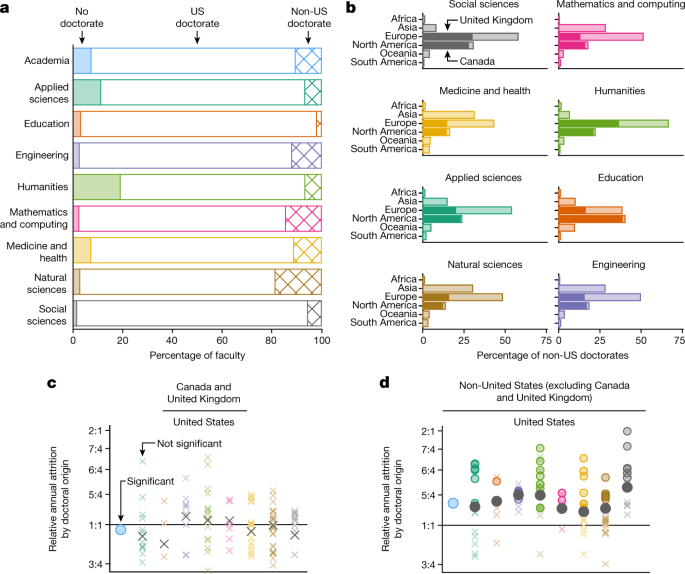

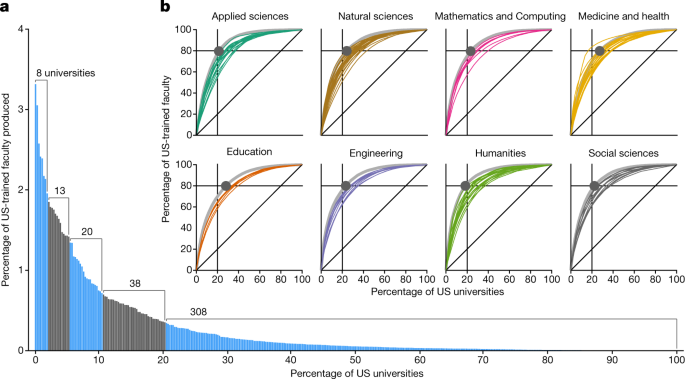

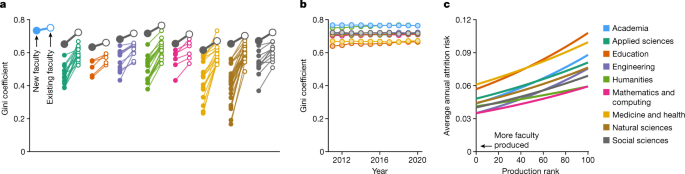

Every year, in almost every discipline, newly minted Ph.D.s outnumber tenure-track job postings by a substantial margin. While that trend has gone on for decades, most Ph.D. programs continue to maintain or even increase student enrollments and remain structured as a form of academic career training. Thus, growing numbers of Ph.D. graduates are trained for, and often expect, an academic career that’s not available to them.

North American graduate schools have made some progress to better prepare students for nonacademic careers. They have led significant innovations in professional development training, and some faculty members in both the United States and Canada have joined the discussion over Ph.D. career futures. Yet for all the talk and innovation, we hear little discussion of the underlying structural forces that maintain and perpetuate this decades-long overproduction of Ph.D.s.

Some people argue that the overproduction of Ph.D.s can be blamed on clueless faculty members unaware of “how bad it is out there.” But the available data do not support that conclusion. Our research on Canadian political science (to our knowledge, the only published study of its kind) found the vast majority of faculty were aware of the tight academic job market and were open to seeing the Ph.D. as preparation for academic and nonacademic careers. Only 15 percent felt less motivated to supervise students not planning to pursue an academic career.

In other words, the problem is not out-of-touch faculty. The problem is the system itself.

Why Ph.D. Admissions Remain High

If we graduate too many Ph.D.s, the obvious response is to admit fewer doctoral students. But which university or program will move first? Several programs froze their 2021 enrollments in the wake of COVID-19, but that is a short-term solution unlikely to signal a broader trend.

Rather, we face a classic collective action problem: we might all be better off if overall doctoral enrollments decline, but each institution, department and even faculty member benefits from maintaining or increasing their own doctoral student enrollments. The reasons are numerous, but to put it most simply, the modern university system requires Ph.D. students to keep everything else going.

In addition, the rising importance of international rankings for establishing institutional reputations and attracting students prompts research universities to try to maximize how high they rate according to various component measures. Those measures often include the number of doctoral students as a proportion of all students or the number of doctoral graduates relative to faculty members. That also creates a clear incentive to grow doctoral numbers.

And doctoral students are not just beans to be counted for international rankings. The grants that fuel the research enterprise at these institutions are structured to fund trainees (graduate students and postdoctoral scholars). Without evidence of employing and training doctoral students in past grants, a faculty member is at a disadvantage in future grant competitions.

The teaching enterprise of the modern research university is similarly fueled by armies of graduate teaching assistants grading papers, conducting labs and interacting with undergraduate students. Without them, faculty members would struggle to find time for research.

In some cases, Ph.D. students represent increased institutional revenue, as well. For public universities, that may be built into government enrollment funding formulas that reward institutions for taking in more students -- with Ph.D.s typically bringing in the most per head. Departments and programs also face incentives to sustain or grow the numbers of Ph.D.s in their discipline relative to others in order to increase the status of the unit within the institution and sometimes to maintain revenue, depending on the budget model.

Beyond those imperatives, any conversations about reducing doctoral numbers run into very real concerns about diversity and inclusion. More restrictive admissions policies can further empower graduate admissions committees to restrict the composition of the discipline in the future. As Julie Posselt demonstrated in her groundbreaking Inside Graduate Admissions , this gatekeeper function favors applicants who more closely resemble the current discipline. Reducing doctoral numbers is likely to limit efforts to achieve diversity within disciplines.

Why Program Change Is Slow

What about the other solution: Adapting programs to better align Ph.D. professional training with the realities of Ph.D. career outcomes? Ph.D. programs are increasingly tinkering to add more nonacademic professional development. Graduate faculties have led the way with more full-time professional development staff, programs for nonacademic careers and innovative ideas like the public scholars’ programs that many universities have started.

But most of those changes are Band-Aid solutions rather than effective interventions -- small ideas bolted onto programs and delivered by outside specialists rather than fundamental overhauls of those programs. The number of players also presents coordination problems. Our study of department chairs found widespread support for nonacademic professional programming but also frustration about the duplications and gaps that often result from having many different people on the campus involved.

Ideally, nonacademic employers’ needs would inform program changes. But, in fairness, it’s not clear who these nonacademic employers are: while most Ph.D.s are finding jobs eventually, little evidence suggests that employers are actively seeking Ph.D.s except in certain applied fields. For most Ph.D.s, the search for nonacademic jobs will always involve fighting against the current rather than riding with it.

How to Move Forward

The challenge of the "Ph.D. jobs crisis" is deeply structural and built into the systems of modern research universities with no simple solutions or clear consensus going forward. To push past this logjam, universities must improve communication, information and incentivization.

First, institutions need to improve internal communication about and coordination of Ph.D. career programming and placement. Graduate career development is a haphazard and disjointed affair at many universities. Graduate faculties, units and individual supervisors often operate in silos, leaving it up to students to filter and manage different messages and options.

Second, universities need to collect more information about Ph.D. job outcomes outside academe and, crucially, graduates’ satisfaction with those outcomes, and then share those data with programs and students. Programs would benefit from nuanced, discipline-specific information from employers about where and when Ph.D.-level expertise is valued and how programs can adjust and adapt. Students, especially prospective applicants, need clarity about the realities of the Ph.D. job market. Ideally, Ph.D. outcome data would be standardized and collected across institutions, allowing for consistency, comparison and transparency -- rather than letting each institution construct its own methodology and spin the data to present itself in a favorable light.

That brings us to the third response: incentivization. Universities need to establish stronger rewards for everyone to invest further in the coordination and information that we’ve described. Admittedly, much of that incentivization will come at a real cost to already cash-strapped institutions -- someone has to pay. But the university sector must recognize the reputational costs of this ongoing problem. The Ph.D. jobs crisis is not going away. And as it becomes more visible and acute, it is attracting the attention of those who would seek to slash entire programs and areas of higher education.

Those of us who work at universities and in governments, funding agencies and other organizations must all recognize and acknowledge that we are the problem . We must confront the corrosive effect of the systems we have established that depend on ever-larger intakes of Ph.D.s and make tough choices about where to draw the line or how to change programs if those graduates do not find satisfying careers when they leave. The responses required are not about simply changing attitudes. They demand we change the entire way we operate.

UT Dallas Student Newspaper Strikes After Editor Is Fired

The Mercury ’s adviser called a vote to fire the editor in chief, claiming he violated three student media by

Share This Article

More from career advice.

Academia Broke Me

Becoming an academic editor gave me my life back, writes Paulina S.

A Career Option Humanities Ph.D.s Should Consider

Jobs in career advising for grad students call on the natural skills of such Ph.D.s and are both fulfilling and in de

How to Give Up Tenure—Twice—and Thrive

Regardless of our fears and challenges, Heather Braun writes, we all can take actions, however small, that will over

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

From PhD to Professor: Advice for Landing Your First Academic Position

I am living the dream.

At least, my professional dream, that is. I have the perfect job for me. And I’m going to share with you how I got it.

First, a little about me. This August, I started my second year of being a tenure-track assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the School of Social Policy & Practice, a program that is consistently ranked in the Top 15 in the country by U.S. News & World Report and one of only two Ivy League social work programs.

As new junior faculty member, I only teach one course each semester so that I have the time to launch my independent program of research. No dumping major course loads on the new assistant professors here! And as with all faculty at my school, I will only ever be required to teach two courses per semester at most, with the option of “buying out” of teaching when I have grant funding.

Additionally, as a new assistant professor, I am given priority selection for the courses I teach, having the school try its best to accommodate my expertise and interest. As soon as I started last year, my dean set up “meet and greets” with key players in my research area in Philadelphia and supported the development and submission of my application for a small, internal grant from the Provost’s Office for the first study in my research portfolio.

I could actually keeping going with why my job is so awesome, but that’s not the point of this article! Instead, I’m going to share what I learned getting to this point—my advice for other PhDs and aspiring professors out there on how to play the academic job search game and win big. Here are five strategies that really boosted my application and helped me land my dream position.

Related: Go to Grad School Guide: PhD Programs

1. Prioritize Publishing

The same publishing rule that echoes through the halls of academia for professors holds true for emerging scholars and newly minted PhDs: “Publish or perish.” A recent article published in The Conversation confirms what I found as true with my own experience: The best predictor of long-term publication success is your early publication record, or the number of papers you’ve published by the time you receive your PhD. And long-term publication success is at the top of the list for what chairs and deans hope their new assistant professors achieve, as this is what ultimately leads to tenure at places like Penn.

In other words, it’s crucial to prioritize publishing now, long before you graduate. I entered my PhD program in 2005, my first two papers came out in 2007, and I published at least two papers per year through my graduation in 2009. When I visited Penn to interview, I had another four papers on my CV , and I know that this early publication success was critical throughout the steps of my candidacy, from the invitation for the conference interview to the campus interview to the job offer.

Of course, a lot of your early publishing success as a PhD student will depend on your research advisor and mentor. I was very fortunate to have a mentor who took great joy in mentoring doctoral students and prioritized getting them involved in paper-writing early on. If you find yourself with someone who is not prioritizing your publication record, however, I recommend having a serious conversation with him or her about your needs and the importance of publishing early—or finding a new mentor. As you probably already know, you have limited time to publish while pursuing your PhD, and the publication process is notorious for taking a very long time to unfold. Prioritize it now.

2. Have a Mission Statement—and Show it Off

My professional mission is to improve the lives for youth who age out of foster care, and I intend to achieve this mission by working to reform the child welfare system so that no youth leaves foster care without a lifetime connection to a caring adult.

Having this mission—and having it spelled out—is what I believe sold my dean during my conference interview. In fact, I provided him and the other two faculty interviewers with a handout of the image below, a visual depiction of the principles and values that guide my mission and a plan for how I intend to achieve it. I think my colleagues were impressed by the fact that I had a visual plan that I could easily explain for how I imagined achieving my professional mission, and also by my creativity. Although a bulleted list could have accomplished the same thing, I believe the packaging made a difference.

Think about how you can explain your own vision and your tactical goals in a compelling way, and be specific about how you’ll make a difference as an assistant professor. For those of us at research-intensive institutions, this will generally take the form of ideas about how you will fund your research mission with grants. If you’re pursuing teaching-oriented places, you can develop a similar vision and mission statement, but make it oriented toward educating, mentoring, and inspiring students.

3. Know the Game

And a game it is. Up until this moment, my experience, probably like many of you, had been that if you work hard, do the right things, and make good choices, you are rewarded—a meritocracy. However, that’s not how the faculty game works (and no one really tells you this)!

Rather, academic hiring decisions are based on “fit,” and if you’re not the right fit, for whatever reason, you won’t receive the offer no matter how impressive your CV is. “Fit” can mean everything from your area of research to what you teach to what a given school may need with respect to faculty demographics and diversity to such mercurial things as faculty personality. Although job postings do tend to detail the research or teaching areas a given school may be looking for, these are often broad, and there can be more than one in a given announcement.

You might think the answer here is to try to be what any particular program wants you to be in order to “fit” in, but I think the real lesson is to take the game for what it is: It’s about them—not about you. Although demonstrating how you see yourself fitting in to a particular program—for example, by showing how your research would complement or add value to a department—is very important to do, in the end, you can’t make a square peg fit a round hole. All you can do is to apply, give it your best shot, and realize that in the end, it’s about them.

4. Have a Plan B

The first time I went on the job market, despite several conference interviews with an array of schools and a successful campus visit and job talk at Michigan, I received no offers. My colleague and fellow new assistant professor Antonio Garcia identified with my experience: “I, too, completed several successful interviews, but to no avail. I did not receive any offers for a tenure track position during my last year of dissertation work.”

So what happened? We both fell back on Plan B: post-doc positions. Although I didn’t want to do a post-doc, it bought me some time and allowed me to further build my CV and professional identity. I went on the market a second time following the first year of my two-year post-doc and was then in an even stronger position than the first time. Professor Garcia also landed his tenure track position following the first year of his post-doc. “Although my first choice was not to delay the tenure clock, it has since worked to my advantage,” he explains. “I benefitted from having time to a meticulously develop my research agenda, publish manuscripts, and develop and maintain long-lasting inter-disciplinary relationships. I strongly believe the two-year post-doc will ultimately provide me with better odds of receiving tenure.”

Fact is, you may not land the assistant professor job of your dreams—or even an assistant professor job—the first time you try. So, it’s incredibly important to have a Plan B, whether that’s a post-doc or a job with a private research firm that still allows you to build your publication record and gain other worthwhile experience that can translate to academia, like presenting your work at professional conferences.

Related: 3 Steps to Turn Any Setback Into a Success

5. Swallow Your Pride

I actually applied to Penn twice—the first time I went on the market I was unsuccessful, but after the first year of my post-doc, I saw another job posting and as best I could tell, I was a good “fit.” I had a bit of a pride issue about knocking on Penn’s door again, but I also realized that if I didn’t, only one thing was certain: I would never work there. So I swallowed my pride, I knocked again, and I landed the job of my dreams. In fact, as I was leaving the hotel suite where I had my conference interview, one of the faculty interviewers said, “I’m so glad you decided to apply again.”

Finding your first professorship isn’t an easy road, but it’s important to persevere and to stay focused on your long-term goals. Penn psychology professor and recently named MacArthur “genius” Fellow Angela Duckworth defines this philosophy as “grit.”

I liken it to surfing. In fact, during my job talk at Penn, while sharing my vision with the hiring committee, I also shared this: “When considering a research-oriented career, a particular quote comes to mind, ‘You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.’ If we think of a research career as the surface of a lake or ocean, there are always waves, sometimes big, sometimes small. Nothing we do can stop the waves, but we can learn to surf.”

There are no guarantees that, even if you do all these things, you will land your dream faculty job. But I hope these tips will help you feel perhaps a little more in control while the waves splash over. Try to have fun with this process, at least as much as you can, and may you, too, soon find yourself living the dream.

The Postdoc’s Guide to Tenure-Track Positions

With tenure track positions being few and far between and thousands of applicants to each position that opens, successfully getting a permanent position as a professor requires more than just becoming the best scientist you can. Follow this guide to increase your chances of getting tenure after postdoc.

When you first begin your Ph.D. program, you probably envisioned a career path where you would graduate, complete a postdoc (or maybe two) and obtain a tenure position at a respectable research institution. A few years down the road, you dreams haven’t changed. You’re still working long hours in the lab in an effort to produce quality publications and hopefully get an edge on your competition so you can finally become an independent researcher. The only problem is that there are significantly more postdocs applying to very few tenure track positions, and this is true across the nation.

There are more postdocs than there have ever been. Scientists are spending more time in a postdoc position than they had previously done. They’re also completing more postdoc fellowships than life scientists before them completed to get into their permanent position. This guide—combined with some good luck—will help you maximize your chances of getting a tenure track position at the completion of your postdoc.

Network, Network, Network

While this is true for any field, networking is extremely important when it comes to advancing your academic career in the life sciences. With few tenure-track positions available, having contacts in your field and at institutions you’re interested in can make a huge difference when you are trying to get your foot in the door. As a postdoc or nontenured faculty, reach out to those who have tenure positions at not only your university, but others in your area as well. Attend conferences and network with people there; get their contact information and be sure to write down any details you remember about their position and research. Another way to network is to reach out to people who have published papers that strike your interest and ask them about their work. Simply getting your name out there before it’s time to apply for a tenure-track position can help your application stand out.

| | ||

Avoid the Perpetual Postdoc

I’m sure you’ve heard it before—timing is everything. You don’t want to apply for tenure-track positions before you’re qualified and armed with a competitive application, but it would worse to wait too long to apply. With postdoctoral fellowships lasting longer and longer, many life scientists are getting caught in the trap of never leaving their postdoc position once complete and starting another postdoc cycle.

So when is the best time to apply? First of all, you should be nearing completion of at least one postdoc before you start applying for tenure-track positions. It is not uncommon to have completed two postdoc positions before receiving a position, however, according to Science , completing more than two may actually hurt your chances of getting a professorship. Avoid becoming the perpetual postdoc by preparing early—publish as much as you can in high - quality journals, broaden your area of expertise and showcase your skills on your application.

ProTip: If you become first-author of important research in your field that is published in an impressive journal, do not delay applying for tenure-track positions. Having recently published, relevant work can be a great way to get your application noticed and get an interview.

Ace the Application

Often times the application is not only the first impression the hiring department will get of you, but it can also be the only impression if it does not impress enough to receive an interview. Because the application is so important, you have to ace it. Let’s talk about how.

- Cover letter: The cover letter will determine how much time the reviewer or committee spends looking at your application, if any time at all. You should have a fresh cover letter for every single job you are applying for. Using a generic letter will not convey the reasons you are a great fit for that particular position and institution so take the time to cater your letter specifically to the job you are applying for. Tell the reader why you want the position for which you are applying and why you are a great fit. Also include information on where you did your training and describe your most interesting current research projects. It is also great to include what your future research plans are and how you will accomplish them in this position. Convey excitement and passion for your field and the position throughout the letter.

- Application: Follow any and all instructions provided to you by the institution. Be sure that all of your answers to application questions are catered to the specific position you are applying for and even to the school you are apply to work for. Include an updated copy of your CV, which highlights the specific experiences you have that pertain to the job you seek.

- Mailing the application: If there is an online application, use it to apply and attach your CV. If there is only a paper application, you can scan and email it, send it via FedEx or another mailing service, or simply send it via standard USPS. Pay attention to any deadlines you may be approaching and take any necessary steps to make sure the application arrives on time.

Be Flexible

With few highly-sought after tenure-track positions available, one of the best ways to optimize your chances of being offered a position is to be flexible. There are only so many universities in each state and even fewer in a single city. If you are not tied down to a specific location for family or other reasons, applying for positions all over the country can greatly increase your odds of getting a position. Universities will usually pay for your travel expenses for interviews so it is an advantage to seek out these opportunities if you would be willing to make the move for a tenure-track position.

Make a Plan B

Whether you’re going to use your plan B or not, it’s always nice to have one in case plan A doesn’t work out. There are many postdocs who continue to apply for tenure-track positions and don’t succeed. It can be easy to stay in the postdoc world and hope that next time you apply things will be different, but you should also consider careers outside of academia. After crowdsourcing information from a variety of sources, I have found that most life scientists agree that after completing two postdocs and applying for tenure-track positions during and after them, a back-up plan should be considered. You can read about alternative careers for life scientists in my previous article. Of course, I’m not saying you should give up on academia if it is your dream, but you should be aware of the other paths and options that exist because they can be very rewarding, too.

Following these guidelines will give you the best chances of getting the tenure-track position you are working so hard for, but my best advice to you is to not let the stress of looking for a job get you down. Finding the perfect university and position to fit your skills and personality can take some time, and many current tenure-holders were denied positions before they made it to where they are today. Stay positive and be open to all opportunities that come your way—academic or otherwise.

| |

Category Code: 79107, 79108

Leave Feedback

Related articles.

With tenure track positions being few and far between and thousands of applicants to each position...

10 Questions to Ask Yourself When Deciding if a Postdoc is Right for You

When you’re nearing the end of your Ph.D. program, it is easy to assume working as a postdoc is th...

10 Alternatives to Completing a Postdoctoral Fellowship and Entering Academia after Graduation

If you find yourself asking the question, “is a postdoc really my only option after receiving my P...

Adjunct or Tenure: The Journey of a Life Science Professor

The path to becoming a college professor is long and arduous. To begin, it takes a huge commitment t...

Join our list to receive promos and articles.

- Competent Cells

- Lab Startup

- Z')" data-type="collection" title="Products A->Z" target="_self" href="/collection/products-a-to-z">Products A->Z

- GoldBio Resources

- GoldBio Sales Team

- GoldBio Distributors

- Duchefa Direct

- Sign up for Promos

- Terms & Conditions

- ISO Certification

- Agarose Resins

- Antibiotics & Selection

- Biochemical Reagents

- Bioluminescence

- Buffers & Reagents

- Cell Culture

- Cloning & Induction

- Competent Cells and Transformation

- Detergents & Membrane Agents

- DNA Amplification

- Enzymes, Inhibitors & Substrates

- Growth Factors and Cytokines

- Lab Tools & Accessories

- Plant Research and Reagents

- Protein Research & Analysis

- Protein Expression & Purification

- Reducing Agents

- GoldBio Merch & Collectibles

Volume 15 Supplement 2

Accomplishing Career Transitions 2019: Professional Development for Postdocs and Tenure-track Junior Faculty in the Biomedical Sciences

- Open access

- Published: 22 June 2021

Preparing for tenure at a research-intensive university

- Michael Boyce 1 &

- Renato J. Aguilera 2

BMC Proceedings volume 15 , Article number: 14 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7690 Accesses

5 Citations

Metrics details

At research-intensive universities in the United States, eligible faculty must generally excel in research, teaching and service in order to receive tenure. To meet these high standards, junior faculty should begin planning for a strong tenure case from their first day on the job. Here, we provide practical information, commentary and advice on how biomedical faculty at research-intensive institutions can prepare strategically for a successful tenure review.

Introduction

New tenure-track faculty members at research-intensive (R1 or R2) institutions [ 1 ] emerge from a competitive, months-long job search process, eager to begin their independent careers. At this early stage, the tenure process may seem far away – about 6 years at most institutions – but tenure-planning should begin as soon as possible. Of course, being a new faculty member comes with a steep learning curve. Nobel Laureate and former Howard Hughes Medical Institute President Tom Cech has likened this to getting a driver’s license: “All of a sudden you have all of this freedom to turn when you want to turn or to go straight when you want to go straight. On the other hand, you have to pay for the gas, and you’ve got some responsibility” (quoted in [ 2 ]). How to balance the day-to-day tasks of a brand-new faculty member with the long-term career-planning you need for your future? This special issue of BMC Proceedings contains other valuable articles on managing the specific and immediate challenges of your new job, such as how to set up a research lab [ 3 ]. Here, we focus on the longer-term strategic planning that you need to position yourself as a shoo-in tenure case.

Know the rules of the game

The crucial first step in preparing for tenure is to understand the processes and expectations at your institution, for your position. Tenure requirements at American R1/R2 institutions change over time. Generally speaking, faculty in the 1980s were expected to demonstrate excellence in research, teaching or service, but 20 years later, all three came to be essential, with research as the top priority in most cases [ 4 ]. Promotion and tenure criteria also vary by institution and can sometimes be frustratingly vague [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Ambiguous or general criteria can be good, insofar as they allow for flexible and holistic assessment of each candidate, but they can also be bewildering for new junior faculty, who crave clear expectations. First, get the official tenure and promotion guidance in writing from your institution. Often this is publicly available in a faculty handbook or similar document from the Provost or equivalent chief academic officer. Read the guidelines carefully and then discuss them with your network – your department chair, senior colleagues both inside and outside your department, recently tenured faculty and (ideally) colleagues who have served recently on appointment, promotion and tenure (APT) committees. Ask questions about anything that’s unclear and solicit advice about any “unwritten rules” that you should know, such as the relative weight placed on research, teaching and service at your institution. Many universities have Faculty Advancement or equivalent offices that offer workshops on tenure preparation for junior faculty – attend every year, to track any changes in expectations and to keep the goal on your radar. In short, know the rules. All of the advice that follows in this article is based on common themes among research-intensive US universities and our own experiences, but we stress that all tenure processes are local , and you must do your due diligence to learn the ropes and expectations at your own institution.

Know the process

To get tenure, you’ll need to know what goes into a successful tenure dossier and how it is evaluated [ 8 ]. You can expect that your research, teaching and service accomplishments will be comprehensively assessed. For research, peer-reviewed publications (especially primary research, but also reviews and commentary) and grant funding are key. For teaching and mentoring, teaching philosophy, syllabi, course evaluations and other documentation are typically required, and lists of trainees in your lab and service on thesis committees are the norm. Service is generally given the least weight, but notable accomplishments in the outreach, science communication, public policy, mentoring, and diversity/equity/inclusion (DEI) realms are valued, provided they accompany strong research and teaching. We discuss each of these three areas in more detail below.

Learn the nuts and bolts of the tenure preparation process, including the timeline. For example, you may undergo a pre-tenure review after your third year or so. At this stage, you typically prepare the same documents as you would for tenure (but without external evaluation letters; see below) and members of the departmental or APT committee review this package. You’ll receive feedback, focusing on areas of weakness and offering advice for improvement. The committee may even recommend an early tenure process, in strong cases. Typically, a complete dossier will then be due to a department chair by the end of a faculty member’s fifth or sixth year on the job. It often gets a first-pass read by the chair and an ad hoc departmental committee, to generate a list of external reviewers whom the chair will invite to provide letters reviewing your tenure and promotion credentials. Once letters arrive, the departmental committee evaluates the case thoroughly and presents a recommendation to the department (usually tenured members only) for a discussion and vote. After that, the chair usually shepherds the case through next steps, including review by a school or college APT committee, a dean, a University-wide APT committee, the Provost and the President or Board of Trustees or Governors. Get clarity from your department chair about when your dossier documents will be due, how long the process takes after submission (typically 6–12 months), and whether you can provide updates along the way, such as late-breaking grants or accepted manuscripts.

In your first months on the job, learn what future milestones you’ll pass en route to preparing your tenure dossier. Will you have annual evaluations or reappointments by your chair, a committee or someone else? Will an official mentor or mentoring committee of senior faculty be appointed for you (or will you need to request one from your department head or organize it yourself)? Is there a mid-tenure review after 3 years or so? These examples illustrate structured ways to receive feedback on your progress even in early years, so seek out these opportunities if they’re not provided automatically. If your institution requires your CV in a particular format for the tenure dossier (which is common), ask for a template in your first month on the job and begin adding to it right away. To start, list everything, even seemingly small accomplishments or honors, such as invited talks at your own institution, 1 hour of service on a panel discussion or a blurb highlighting your recent publication in a different journal. Down the road, you can always trim some items from the CV if you like, but you can’t add what you can’t remember, so don’t rely on memory and keep the document updated in real-time. Another strategy is to keep a tenure folder in your desk drawer, containing information to be added to your dossier at a later date, such as seminar fliers of your talks, thank-you letters for services provided, invitations for paper and grant reviews, service on committees, etc. You may be surprised how much you’ve done after five or 6 years and how many things you would have forgotten if you didn’t keep this information in one place.

Mentoring and training undergraduate and graduate students are important not only for your research (see below), but also for your tenure evaluation at most institutions. As you prepare your tenure dossier, consider adding a mentorship statement that describes your training record [ 9 ]. For example, do you offer hands-on training in your lab yourself? Do you teach or participate in workshops, such as NIH Responsible Conduct in Research or Rigor and Reproducibility trainings? Do you teach manuscript- and grant-writing to mentees and others? Do you perform outreach to recruit students from historically excluded groups to your university? Be sure to mention if you’ve received formal mentorship training by your institution or a professional organization, such as the National Research Mentoring Network. Within your academic lifespan, you’ll train a significant number of students and it is therefore important to keep a record of these trainees and their whereabouts and accomplishments (publications, fellowships, invited talks/presentations, etc.). You can also track former trainees by asking them to create a LinkedIn or ResearchGate account while they are under your supervision. At one of our institutions (UTEP), we expect all undergraduates in our NIGMS-funded training programs to create LinkedIn accounts so that we can stay current on their achievements and facilitate our own grant progress reports, renewals and new submissions. If your trainees move on to great places to pursue their post-graduate careers, you should list that information in your CV or mentorship statement. This information will also be valuable for NIH training grant applications, which require you to list your mentorship accomplishment in your biosketch and trainee tables. Importantly, some institutions request letters from current or former trainees as part of the tenure review process, providing another good reason to be the best mentor you can.

When it’s time to write your tenure dossier documents, keep your multiple audiences in mind. Usually, a single research statement will be evaluated by a wide range of groups, including the colleagues in your department, experts in your specific field (i.e., the external letter-writers) and non-scientists, such as German or law or divinity faculty on a university-wide APT committee. Writing a document that’s accessible and exciting to all of these audiences is a challenge, and it pays to get lots of feedback on drafts from friends or colleagues in each of the above categories. In planning your document, it can help to begin with a broad and non-technical overview of your research and its significance in the field, to help orient non-scientist readers, and then work down to specifics and expert knowledge when showcasing your science for others in your specialty.

External letter-writers can be the most mystifying (or terrifying) audience for your dossier. They must typically be “arms-length” from you, meaning you’ve never trained or collaborated with them, yet also expert enough to evaluate your work, and senior or distinguished enough for their letters to carry weight at your institution. Although you may never learn who the letter-writers are, a department chair or senior colleague might ask you (often off the record) to suggest a few names of prospective referees. If you have this opportunity, name scientists who know and appreciate your work, whose letters will be credible and respected, and whom your department might not think of themselves. If your field has one prominent scientist who is a clear leader, your chair or committee is likely to know that and will invite her or him as a letter-writer themselves, so don’t waste a limited number of suggestions on obvious picks. If you choose to suggest referees from outside the US (e.g., to attest to your international research reputation), be sure that they are familiar with the standards and norms of American tenure letters. If necessary, consider requesting to block one or two scientists as letter-writers, if there are people in your field who are known bad actors or with whom you’ve had a professional conflict. But use this option sparingly and with ample justification, so as not to give the impression that you aren’t well-liked in your field. Whoever your external referees are, you want them to sing your praises and say that you would get tenure at their own institutions, a question they are usually asked to answer.

Finally, a word about changing the process: Institutions usually provide the opportunity to “stop the tenure clock” for specific reasons, such as family care obligations, temporary medical problems or other circumstances (including COVID-19). Choosing this option pushes back the date by which you will need to submit your dossier for tenure review, to account for reduced productivity during a defined period of time. To determine whether stopping the clock could be right for you, find and understand the applicable written policies from your institution and discuss them thoroughly with your chair, senior colleagues and other trusted advisors. It’s important to ask their thoughts on how clock stoppages are viewed at your institution and whether it would be a good tactic for your specific situation. Ultimately, of course, it’s your prerogative to decide.

As noted above, research is nearly always the primary tenure consideration for faculty at R1/R2 institutions [ 4 , 10 , 11 ]. A strong tenure case is built on a strong research program, with a track-record of exciting science, peer-reviewed publications and extramural grant support. Your research must be independent, meaning you should make it clearly distinct from that of your doctoral and postdoctoral advisors. Building on your prior experience and knowledge is good, of course, but you also have to demonstrate your identity as an innovative and independent investigator by moving in new research directions and making impactful contributions to your field. Another way to think about this is as building your own unique brand – become known as “the person who” (e.g., “She’s the leader in transcriptional control of NK cell development,” “He’s the guy who discovered the role of phase separation in subnuclear compartments”). Similarly, collaborating with other groups can be an excellent way to advance your science, but you should do it judiciously. For any collaborative project or publication, your individual and substantive contribution should be clear (e.g., to external letter-writers evaluating your research output), and you should never let an excessive number of collaborations result in scattershot science, such that your lab lacks its own cohesive research focus. For this reason, it might be necessary to include a detailed description of your contributions and those of your students and staff within the tenure dossier CV for each collaborative paper that you published during the tenure period. And when establishing new collaborations, it’s helpful to discuss goals, division of labor and even authorship on future publications up front, to align expectations and ensure the relationship goes smoothly.

When launching your lab, it’s usually wise to start more than one project, or at least pursue multiple independent approaches to one overarching theme, so that not all your eggs are in one basket. At the same time, of course, you must also avoid stretching yourself too thin in the process. It’s often prudent to have a mix of high-risk/high-reward and safer, meat-and-potatoes projects, to ensure that the lab will be productive while also aiming for impactful discoveries. You should be choosy in admitting graduate students, postdocs and staff to your group to work on these projects. Many new PIs are impatient to fill their empty labs with warm bodies and get the science started, but it pays in the long run to wait for the right rotation student or postdoc candidate, and not accept someone mediocre just for the sake of having personnel. The adage “You are your own best postdoc” frequently applies for the first few years of a new lab, when the PI often works at the bench. If your lab budget allows, consider spending money to save time. For example, if you’re hiring a technician, you may want to bring on a more expensive but very experienced candidate, who can work independently and perform managerial tasks in lab, freeing you up for your other responsibilities. This approach may be especially beneficial for brand new faculty, who must usually establish a good research training environment in order to attract top graduate students and postdocs. Similarly, pricey experiments (e.g., CRISPR screens or proteomics projects) can sometimes be a good early investment, as a way to generate preliminary data for future grants and to lay the groundwork for new projects later.

Assuming you’ve chosen a good team of graduate students, postdocs and technicians, you might also take on a few undergraduates to assist them. Many universities have training programs that select some of the best undergraduate students to work in research laboratories and generally provide student stipends and modest research funds. One avenue to recruit graduate students into your laboratory early in your career is to train a cadre of highly motivated undergraduates. In fact, one us (RJA) ran his laboratory with an excellent team of undergraduates, with two of them later joining the lab as Ph.D. students. These early training experiences can lead to the development of undergraduate research training grants that, once funded, allow many more students to participate in research. Participating in undergraduate training can be a rewarding experience, is often highly valued by colleagues and opens the door to research for students undecided about their career paths [ 12 ]. Experienced faculty find ways of linking up undergraduates with graduate and postdoctoral fellows to form highly functional research teams that can be an asset to any laboratory. The graduate and post-graduate mentors not only benefit from having an extra pair of hands to assist them in their projects, but also attain mentoring skills that will be valuable throughout their careers. Of course, it’s important to make sure that undergraduate training activities are viewed positively at your institution and department, and to be careful to accept only a manageable number of students who are committed to doing high-quality research, and not just looking to burnish their resumes.

Peer-reviewed publications are the coin of the realm and the primary metric used to judge research output during tenure evaluation and beyond. Be sure to know what your institution values most in publications. Do you need a certain number? Does the journal name matter? There’s a growing awareness that impact factors are a poor – and often harmful – way of judging research quality [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Nevertheless, citation-based metrics, like impact factor, are mentioned in the APT guidelines of many institutions [ 16 , 17 ]. If your university assesses publications using this kind of quantitative metric, it behooves you to understand those rules and make decisions about manuscript submissions accordingly, perhaps in consultation with your chair or other trusted senior colleagues. In any event, target journals where peers and prospective letter-writers in your field will see your work, and always avoid predatory journals [ 18 ]. Submitting manuscripts as pre-prints (e.g., to bioRχiv) can help advertise your work, garner additional citations and even generate constructive criticism from the community [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Primary publications are the cornerstone of your research portfolio and should be your main focus, but influential or highly cited review or commentary articles in your field are also valuable scholarly contributions. Keep in mind that many journals accept unsolicited proposals or even complete manuscript submissions for review articles – if you have a great idea for a review that will fill a gap in the literature or reshape the way your field views a problem, you don’t need to wait to be invited by an editor before you write it.

Funding is a crucial complement to research. Science costs money, and you’ll probably need grant revenue to bankroll your work beyond the start-up phase. In addition, extramural grant support for your lab shows that funding agencies and their peer review panels value your research, so their seal of approval will be viewed favorably from both scientific and financial perspectives by the people evaluating your tenure case. As a brand-new faculty member, it might be wise to apply for career awards from private foundations or similar sources. Your top priority must be to get your lab up and running, but career award applications are often short and straightforward, and can allow you to cash in again on the strong record of postdoctoral research that got you your faculty job in the first place. In the longer term, project-based grants from NIH, NSF, DoD, large foundations or other agencies are the standard way to keep a lab solvent. As always, know the tenure expectations at your institution – if you need a certain dollar amount in support, a certain percentage of your own salary paid from grants or a particular kind of award (e.g., NIH R01) for a strong tenure case, find that out early, so you can prepare far ahead of time for grant submissions, re-submissions and renewals.

To maximize your chances of funding success, take a strategic and multi-pronged approach. Grant-writing can be laborious and challenging, but try to embrace it as a way to crystalize your ideas and align your research questions and plans with your scientific goals. Gathering examples of successful grants from colleagues is a great way to begin. You can also seek out formal grant-writing training, such as from your institution’s faculty advancement office, professional societies [ 23 ] or popular commercial options like the Grant Writers’ Seminars and Workshops [ 24 ]. Ask well-funded colleagues who have served on review panels and take an interest in your success to read drafts of your proposals and provide candid feedback. Begin far, far in advance, so you have time to receive multiple rounds of feedback if necessary and to work with the staff and administrators at your institution on the budget and approval process, which can be lengthy. Success rates with funding agencies are never as high as we’d like, so prepare to take many shots on goal. Some applications may run up against bad luck (e.g., a low payline or a hostile reviewer), so submitting a number of applications to different agencies can be a good way to hedge your bets. Consider being flexible in how you approach your science, taking different angles on different grant applications to appeal to different sponsors, and follow up on the directions that get funded [ 25 ]. In all cases, of course, a grant application needs a solid hypothesis supported by compelling literature and/or preliminary data in order to have a chance at funding, so be sure your proposal will have those components before you commit the time to preparing it.

Teaching may be emphasized less than research in R1/R2 tenure cases [ 4 , 10 , 11 ], but a solid record of quality instruction is nevertheless essential. As always, learn the expectations for how much teaching you must do for a strong tenure dossier, and what evaluation metrics will be used. Many new biomedical faculty at research-intensive institutions are fresh off a postdoc where they had little or no teaching opportunities. Therefore, be proactive in seeking out instruction and mentoring to improve your teaching. You can sit in on senior colleagues’ classes and have them evaluate your own, to provide constructive criticism. Many universities have a Center for Teaching and Learning or equivalent. Taking advantage of the resources, workshops and expert advice from those groups can be invaluable for new faculty, and will demonstrate your proactive effort to capitalize on institutional support for strong teaching. Keep in mind that excellent teaching takes a lot of time, with several-fold more hours of preparation than actual classroom contact hours, especially for new faculty and/or new courses. Evolutionary biologist Joel McGlothlin has nicely captured this point, saying “I found that teaching your first class takes precisely all the time available” [ 26 ]. Be sure to schedule plenty of prep time. If possible, it’s also valuable to make your teaching synergize with your research or other interests – perhaps volunteering to teach a course that forces you to brush up on a field relevant to your own science, or helps you ground your own work in a big-picture context when you write a grant. McGlothlin writes that an “NSF program officer once told me that to write a good grant, I should try to imagine how my research could serve as an example in a textbook. This was so much easier to do after a couple of years teaching evolution to undergraduates” [ 26 ]. Teaching a course in your area of expertise is also a great way to convey your enthusiasm to your students and share personal anecdotes of learning about new discoveries at a conference or how breakthroughs in the field were made. Students appreciate hearing about this human side of science.

Looking ahead to the teaching section of your tenure dossier, find out early what kind of materials you’ll need to include. Teaching philosophy statements, sample syllabi and course evaluations are standard examples. Some universities have well-crafted and universally applied course evaluation systems, and others do not. To ensure proper documentation of your excellent teaching, ask your course directors about evaluations before you begin as an instructor in any class (even for a single guest lecture), and create an evaluation instrument – preferably in cooperation with experts at your Center for Teaching and Learning – if one wouldn’t otherwise be provided. Many tenure reviews also require peer evaluations of your teaching and will look for steady improvements over time, so teaching a new course every semester or quarter is not a good idea. Finally, it’s important to note that teaching evaluations frequently reflect bias against certain categories of instructors, such as women and/or p ersons e xcluded because of their e thnicity or r ace (PEER scientists [ 27 , 28 ]). If you belong to these groups (or even if you don’t!), ask your chair or dean what steps are taken in your university’s APT process to mitigate these well-documented biases. In any event, always look past petty or egregious comments and focus on improvements based on constructive criticism.

Junior faculty can make important service contributions in many realms, such as DEI, public policy, science communication, outreach, curriculum development and academic administration. Service should always complement (and not detract from) strong research and teaching and would rarely be sufficient for tenure alone. However, a track-record of impactful service shows colleagues how you contribute meaningfully to the community of scholars in your institution and can be a valuable component of a complete dossier. Service opportunities exist at the department, school, university, national and international levels, so you’ll want to think strategically about which activities appeal to you the most, will help advance your tenure case and represent a manageable time commitment. Notably, scientific or professional societies can be both a tremendous support for junior faculty and a source of significant service and leadership opportunities beyond your own university [ 29 ].

As a junior faculty member, you’ll want to select your service obligations carefully, such that they align with your values, help your own career and don’t overburden you. Consider saying yes to (or even volunteering for) service opportunities that allow you to contribute to your community while benefitting yourself. One example may be serving on a graduate admissions committee or teaching first-year students, to boost the odds of recruiting excellent people to your lab. Similarly, serving on a seminar-planning committee might allow you to invite prominent scientists in your field who could become reviewers on your grants, papers or tenure dossier, and reviewing a manageable number of grants or manuscripts for funding agencies or journals might be useful experience for preparing your own submissions later. Regardless of your interests, be sure to say no – politely but firmly – to service invitations that would seriously detract from your research, teaching or work-life integration. Junior faculty are usually somewhat shielded from unreasonable service requests, but don’t hesitate to ask for help from your department chair or other mentors if too many demands are made on your time. In particular, women and PEER scientists are disproportionately burdened with service commitments [ 4 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. These requests can arise from good intentions, such as a desire to broaden representation on a committee or a review panel. Nevertheless, women and PEER faculty especially should be mindful of their time and say no to service obligations that would threaten their other work responsibilities. Find out from your chair, mentors or peers what a typical service obligation looks like for junior faculty at your institution, and don’t feel the need to exceed that, if doing so would overtax you.

Organization and time management

Now that you know what you need for a tenure dossier, how can you plan to build a great one? An essential first step is to be organized – when it comes to planning for tenure, “[b] esides productivity, organization is your best friend” [ 8 ]. As suggested earlier, keep your university-formatted CV up to date, starting in your first few weeks on the job, so you’re sure to have complete records of your achievements. Save documentation of your work, too. When you’re finalizing your dossier, course evaluations from a seminar you taught 5 years prior might be impossible to recover, so collect complete and well-organized records as you go.

Time management is also key, in several senses. First, you want to make strategic decisions about how much time to apportion to research, teaching, service and other activities, based on your own preferences and your institution’s priorities. Balancing these interests is a challenge for many faculty [ 4 , 35 , 36 , 37 ], so seek help from your chair, mentoring committees, junior faculty peers, Faculty Advancement offices or scientific societies when you need it. Time management is also critical for accomplishing specific tasks. A postdoc is typically expected only to perform experiments and related work (e.g., writing manuscripts), whereas a junior faculty member faces a huge range of tasks, posing new organizational challenges. Keep a calendar, preferably an electronic one that synchs across all the Internet devices you use. Plan far ahead for major tasks, like preparing a grant or submitting a manuscript. Most junior faculty find that these take far longer than anticipated, from working through multiple layers of budget preparation and institutional approval on a grant application, to wrestling with a journal’s web interface to upload manuscript documents and information in the right order. Try to stay ahead of the game by starting tasks early. Before agreeing to any new commitment (a collaboration, a manuscript review, a new committee membership), be sure to understand the expected time demand and be realistic with yourself about whether it fits well with your availability and priorities. Learning to say no gracefully is both a common challenge and an essential skill.

Some additional advice for fellow procrastinators: It’s helpful to make yourself write at least 1 day a week, even if it’s just for a few hours. Block time on your calendar and write a few paragraphs for a paper, the Specific Aims of a grant, a conference abstract draft, etc. Many PIs prefer to work at the bench versus in the office, but regular and dedicated writing time can help you get the tasks done.

Finally, be kind and reasonable with yourself as you learn the ropes and accept that some things may not get done, or not done quite the way you would ideally want. McGlothlin acknowledges that juggling too many work tasks can often trigger guilt for junior faculty, but it’s possible to come to terms with this:

It becomes hard to focus on getting any one thing done because of the weight of the to-do-list albatross around your neck. I wish I could say that I found some magical time management solution to balance tasks and get caught up, but I never did. What I did realize is that it’s possible to let go of the guilt. You can forgive yourself for not getting things done on time or done as well as you would like, or for prioritizing one task (sometimes the wrong one!) over another. Yes, I still apologize to others when I’m late or otherwise let them down, but I try to forgive myself, cut the albatross loose, and move on [ 26 ].

Professional skills development

New tenure-track faculty at R1/R2 universities often have little formal training for many of their responsibilities, such as grant-writing, budgeting, hiring, managing, motivating and (perhaps) firing employees or students, teaching in a variety of formats, overseeing several research projects at once, complying with safety and ethics requirements on behalf of a group, and a wide range of academic service. Preparing a strong tenure case requires mastering most or all of these professional skills – a daunting task. One strategy is to seek out formal training for junior faculty, such as workshops offered through your institution’s Human Resources, Institutional Equity or Faculty Advancement offices. Some outside groups also offer well-regarded lab leadership courses, such as the American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) and other professional societies, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and the European Molecular Biology Organization (some US training sites are available) [ 38 , 39 , 40 ]. There are also focused programs for new investigators to learn specific skills. For example, several scientific societies offer structured grant-writing programs to new PIs [ 41 , 42 ]. The NIH Early Career Reviewer (ECR) program is another attractive option, allowing junior faculty to serve on NIH review panels with a reduced workload [ 43 ]. Junior faculty in the ECR program provide valuable service to the scientific community while also learning about grantsmanship and the inner workings of the review process, and networking with other panelists in the same field. Sometimes, gaining experience as a grant reviewer can be as simple as e-mailing the scientific review officer in charge of a relevant panel at NIH, NSF or another agency to volunteer your expertise on an ad hoc basis. Of course, learning grantsmanship or another professional skill by performing service is a valuable but time-consuming activity, and you’ll want to be sure that the cost-benefit analysis is in your favor before you agree. Beyond these approaches, junior faculty can also improve their skills through advice and mentoring by senior colleagues, through formal mentoring committees or individual conversations to discuss professional challenges and strategies. During the tenure preparation marathon, it pays to explore all of these avenues to hone your skills.

Scientific recognition and networking

For a successful tenure review, your accomplishments must be appreciated by colleagues at your home institutions and beyond. We might all hope that “the research can speak for itself,” but the reality is that tenure (and all science) depends on doing high-quality work and ensuring that others know about it. Within your department, be sure that your colleagues understand and appreciate your research. If it’s highly interdisciplinary, in a brand-new field, or somehow different from most of the science in your unit, you may need to take extra care to educate your coworkers about its significance and value. Internal work-in-progress seminars on your campus and posters at department retreats (presented by you and/or your trainees) are a simple and collegial way to spread the word about your exciting projects. Outside your institution, seminars at other universities and talks at conferences are key ways of introducing yourself and your science to the community. It can be shrewd to pick one or two important conferences in your research area and attend them every year, presenting your work as often as possible, to raise awareness of your research and become a fixture in the professional network of the field. It’s also a good idea to build an attractive and informative lab web site, with your publications and research interests clearly listed. Many faculty also use social media, such as Twitter, as a tool to gather information (e.g., from journals, funding agencies and other scientists) and to advertise the accomplishments of themselves and their trainees, such as new pre-prints and papers, awards and grants. Consider applying for awards to recognize your achievements in research, teaching or service, or ask senior colleagues to nominate you when needed. A long list of awards is not typically a prerequisite for tenure, but some recognition beyond your institution doesn’t hurt.

Networking can be a tremendous help to junior faculty, by recruiting trainees, finding collaborators, meeting future grant or promotion evaluators, seeking help, raising awareness about your own accomplishments, and more. Networking may not come naturally to all scientists (or to everyone in any field), but it’s wise to learn to do it in a way that’s proactive and intentional, while remaining authentic to your own personality and style. You can begin at home, in your own department. Simple things like lingering for pizza after a seminar or joining a department happy hour or retreat to chat with colleagues and students can build collegiality and spark interesting scientific discussions. (To be clear, drinking is optional in all cases – networking at happy hour works just fine over a cup of coffee or glass of water!) Similar opportunities exist at conferences, when you visit other campuses for seminars, or when outside speakers visit you. As noted, it can be helpful to invite seminar speakers to your home institution who are likely to review your future manuscripts or grants, or write external letters for your tenure dossier (e.g., members of the NIH study section where your application will go). This strategy promotes your networking, by helping you establish good relationships with more senior scientists, and also aligns well with your research interests, because someone serving on a panel that would review your grants is likely to have similar scientific interests to your own, making them a natural choice for an interesting seminar speaker.

Conclusions

Last but certainly not least, be sure to practice self-care and remain healthy and happy as you work towards tenure. To be sure, this can be a challenge. As McGlothlin notes about new faculty positions:

For most people, this will … be their first experience leading a team. It will be the first time that there is no adviser to consult when there is a tough decision to make, which can be daunting at first. Unless you’re lucky enough to find students or postdocs right away, when you start you will be leading a team of one. This can be a huge adjustment for people used to being part of a large lab, as I had been as a grad student and a postdoc. The first year, when you’re working solo in your office or in an empty lab, can be incredibly isolating [ 26 ].