Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

73 Community Engagement and Collaboration | Case Studies

Below we have curated a number of case studies of community engagement within the KMb and research context for you to review. Each case study has associated thought questions for you to work through in order to increase your learning in relation to these real-world examples.

Knowledge Management and Communication Copyright © by Trent University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Child Adolesc Trauma

- v.12(2); 2019 Jun

Meeting Complex Needs Through Community Collaboration: a Case Study

Stephanie m. robinson.

Hotel Dieu Grace Healthcare, Windsor, Canada

Michelle M. Gallagher

This case study focuses on complex trauma in a refugee family. It explores the barriers faced while supporting a family presenting with complex and multifaceted needs. It reviews the roles, processes and participation of practitioners from Service Coordination (case management) and Treatment (therapeutic intervention) perspectives. This case study also examines the gaps in existing services for new immigrant and refugee populations within a community and provides recommendations for closing these gaps.

Introduction

Canada is a multi-cultural society. Canadians are a diverse mosaic of different languages, religions and races. According to Statistics Canada ( 2013 ), there are over 6 million foreign-born individuals living in Canada, totaling over 20% of the population. While not all foreign-born individuals have come to Canada under refugee status, recently the Government of Canada has welcomed 25,000 immigrants from Syria due to conflict in that country which contributed to a refugee crisis. Further, it is reported that approximately half of all refugees are youth under the age of 18 (Ellis et al. 2008 ).

The purpose of this case study is to discuss an Integrated Intervention used with a complex refugee family that experienced violence and trauma in their home country before seeking asylum in Canada. This paper will review the ways in which a Children’s Mental Health Agency (forthwith known as “the Centre”) worked to overcome known barriers to mental health service provision for refugees. It will also discuss clinical dilemmas, identified learnings, successes, and proposed changes to assist future clients who need support from the community.

Intervention

Service coordination – first author’s perspective.

In January 2015, the first author was assigned to be the Service Coordinator for a unique and challenging case. As a Service Coordinator at the Centre, her role involves assessment, referral and case management until discharge from the Centre. The formalized family meeting (known as the Service Coordination Assessment), encompasses an orientation to the Centre, discussion of the family’s concerns and review of the available treatment options. By the end of this biopsychosocial assessment, the Service Coordinator and the family agree to the treatment referrals that seem to fit their needs best. While the service coordinator typically has limited contact with the family after the Service Coordination Assessment is completed, the first author remained heavily involved throughout the course of this family’s interaction with the Centre.

Prior to the meeting, the service coordinator reviewed the intake packages which indicated that the family was new to Canada and had experienced horrific trauma in their home country. These traumas involved murder, sexual assault and discrimination. The father had tragically been murdered, leaving a single mother to care for the children whose ages ranged from 6 to 16. The intake packages also described symptoms being experienced by all of the children, including: depressed mood, physical complaints, sleeping and eating difficulties, enuresis, and school issues (including, academic, social and coping difficulties). In addition to the complex trauma and mental health concerns, the family members did not speak English. Some members of the family spoke French, but their first language was Swahili, and therefore, an interpreter would be required.

The first author researched the available services in the community for newcomers. There were several settlement agencies that support new Canadians. She attempted to locate a professional Swahili and English-speaking interpreter for the family meeting, but was unsuccessful, and therefore, planned to use a step-sibling with limited English skills for interpretation purposes. This was less than ideal but no other option was available at the time.

The children and their mother attended the Centre for the initial appointment, but the English-speaking step-sibling was not present. Instead, the family brought their Settlement Worker who spoke Swahili and English. The first author learned that this Settlement Worker had made the family aware of the Centre. The family members presented as confused and scared. The family was brought down to the first author’s office where the children huddled together and chose to share seats. The mother’s affect was notably flat, as evidenced by her discussion of traumatic events while showing little to no emotion in her voice and expressions.

The Settlement Worker explained that she became aware of the family and their story a few months prior, and realized quickly that they needed mental health support. She explained that her agency provided education to newcomers, but it did not provide mental health support. The Settlement Worker provided further details about the family and helped the mother and children to answer the service coordinator’s questions. While explaining some of the tragedy that had occurred in their home country, the mother shared some violent pictures she had taken when her husband was murdered. No one in the family reacted negatively to the pictures being taken out of the mother’s purse, appearing desensitized.

Once the family had shared their story and answered the first author’s questions, treatment recommendations were made. The service coordinator recommended that the children be referred for trauma-focused Individual and Family Counselling- High Risk. The high risk designation was intended to reduce the length of wait before services. The first author also suggested that another agency that specializes in treatment for survivors of sexual assault be involved. The family explained that they did not have transportation to get to and from the Centre for appointments. They had arrived today with the Settlement Worker, but she was not able to assist with transportation on an ongoing basis. The Settlement Worker also advised that she could not commit to ongoing interpretation for counselling sessions, as she is not a trained interpreter.

The first author recognized that this was a family who desperately needed help. The mother’s flat affect and the family’s apparent desensitization were concerns, somewhat predictable given all the family had been through. Despite being in Canada for a few years, they also seemed not well connected in the community and had few supports. The parent shared that she did not have money for food, clothing or transportation. The parent was asked to sign releases of information so that the first author could follow up with other community resources on her behalf. She expressed concern about signing the releases, but once it was explained that they would assist the Centre in helping her, she signed.

After the Service Coordination Assessment, an email was sent to Centre staff explaining that a recently referred family was in desperate need of help with basic needs, including clothing and food. A collection for the family was organized. Over the next few weeks, the first author’s office was filled with donations of new and used children’s clothing, outerwear, purses, shoes, pull-ups and gift cards. The family appeared appreciative when these items were delivered.

In the following months, there were several meetings with the Centre’s management team and the service coordinator to develop an innovative strategy to support this complex family and overcome barriers. The first author had connected with a therapist from a local Sexual Assault Treatment Agency. Given the overwhelming nature of this family’s needs and the risk for vicarious traumatization, the Centre’s management team arranged for the treatment team (once assigned) and the service coordinator to consult and receive clinical supervision with a well-known trauma expert in the province.

The first author searched the community for a Swahili-speaking social worker, who, if available, could perhaps provide counselling services to the mother while the Centre supported the children. The first author found one Swahili-speaking social worker in the community, who graciously offered to help, but then realized her Swahili Language skills were lacking. The service coordinator contacted a local agency that helped facilitate language services, but they only employed Swahili language aids, not interpreters. They explained that language aids are not professionally trained, and therefore are not recommended to be used for therapeutic treatment. It was discovered that the Centre had access to a Language Line, but it was thought that involving a third person and passing a phone receiver back and forth would also not be conducive for ongoing therapeutic treatment. It seemed that the community had a gap in terms of Swahili language services. Another person from the community came forward to help. She was a secretary at a settlement agency, who spoke English and Swahili. She offered to assist with translation for the family’s counselling sessions. Again, this informal interpreter was less than ideal, but there seemed to be no other choices.

In further consultation with the Centre’s management team, a preliminary treatment plan was developed in June 2015. It was determined that the youngest child was most appropriate to receive counselling from the Sexual Assault Treatment Agency, and therefore, her file would be closed to the Centre. The other children would receive counselling with Centre staff that had trauma training and/or French-language skills, and that the informal Swahili interpreter would participate in those sessions. One of the French-speaking staff is the second author who will elaborate on the treatment plan and therapeutic intervention below. A plan was developed for the youngest child to be provided counselling sessions at the Centre, even though her sessions would be facilitated by the sexual assault therapist. It was hoped that if the family only had to attend one agency, this would be easier and less confusing for them.

The first author learned of a community agency that supported Francophone families and was able to locate an individual through the agency who could assist with the family’s transportation needs. This individual was fluent in French and English. Her role was initially to provide transportation to and from counselling sessions at the Centre. This individual’s role later included French language interpretation for some. The first author learned that another community agency was offering a summer lunch program for low income families. Through this program, the treatment team obtained healthy lunches for the family every day that they attended the Centre for sessions throughout the summer.

A case conference occurred in July 2015, involving the mother, Centre staff and all involved community partners. The preliminary treatment plan was discussed, with which all parties were in agreement. The first treatment sessions were booked in the coming weeks on a weekly basis. In discussions with management and the treatment team, it was arranged for the family to use an available group room as their personalized waiting room when they attended the Centre for appointments. This would allow the family to eat their lunches without interruption and would provide a central meeting location while they transitioned to and from the treatment providers’ offices. The Sexual Assault Therapist was provided a treatment room at the Centre for her sessions. The treatment team was given the opportunity to continue the phone consultation sessions with the trauma expert on a weekly basis.

Through the course of treatment, the Centre accessed several other community agencies to support this family including financial, housing, medical and legal services. The Centre purchased groceries for this family and delivered the food to their home on several occasions, when they could not afford food. The family was connected with a Swahili-speaking child protection worker, who offered further advocacy and support to the family. As well, the team consulted with the children’s schools to ensure that there were no concerns for them in that environment. For the treatment team, knowing that these efforts were being made to meet the family’s basic needs allowed for increased comfort in delving into the mental and emotionally-laden work of exploring and processing their trauma experiences.

Treatment – Second Authors’ Perspective

The introduction of any case traditionally stays with the practitioner throughout the length of treatment. The details provided about this case were vague initially, but the impression of the significant trauma experienced by the family was impactful right from this initial introduction. While the Centre deals with some of the most intensive and high-needs children and families within the community, this felt different from the start.

As mentioned, the clinicians slated to be involved with the case were invited to a case conference to be provided further detail about the family’s experiences prior to gaining refugee status and immigrating to Canada. The information from other community agencies suggested that while the family was not thriving they were indeed surviving, though in need of mental health supports.

The initial introduction to a member of the family was meeting the family’s matriarch. She attended the conference in July 2015, along with members from a variety of community agencies that were already involved. At this meeting the importance of clear introductions given the number of individuals involved was evident. Given the nature of the work that would be done there was an identified need to have clearly defined boundaries and roles for the multiple agencies involved. This conference ended with scheduling several treatment appointments with the children and staff providing examples of what the mother could tell her children regarding the purpose of their attending the Centre. The goal was to decrease feelings of anxiety about their engagement in services.

The family (mother and all children receiving treatment) arrived for their first treatment appointment and appeared excited and apprehensive. All appointments for the children were blocked together given the limited access to interpretation and transportation. Attempts were made to predict and proactively plan for issues such as comfort, hunger and boredom for those who were waiting for their respective therapist and the sole translator. The family had access to snacks and activities such as puzzles, colouring and fidget toys each week.

The Centre was committed to supporting this family and the practitioners who worked with them. For example, decisions regarding some aspects of service provision were left to the individual practitioners. In consideration of language skills and of strengths with the adolescent population, a decision was made to work with a dual-therapist model. As well, per consultation with the trauma expert, each of the children were provided with small gifts geared toward their interests (a doll for the youngest daughter, stuffed animals for the middle children, and a fuzzy blanket for the oldest child) during initial appointments. These were meant to be items of comfort that could aid in the transition from home to an unfamiliar agency such as the Centre from 1 week to the next. These would be termed transition objects, though they were used intermittently by the children as such.

The initial appointment with the adolescent client evoked a sense of surprise and confusion in comparison to the case presentation on paper. Staff had conducted brief research on the country of origin in an attempt to avoid any significant cultural missteps. However, the adolescent presented in a very Westernized manner in terms of clothing and demeanor. She often used French ‘slang’ that was more common to Canada during conversations. She was, above all else, open and clear about the reasons she believed she was attending the Centre. Therapy sessions were conducted in French (a second language to the co-therapists and client alike) and as such patience was needed as topics were translated that could present complexities in expression even in ones’ native tongue.

While the limited access to interpretation services created a lengthier visit for the family as a whole, this also allowed for observation of the interactions between family members between their appointments. This allowed the team to tailor the approach based on clearly observable behaviours and expressed needs. Specifically, observing the experiences of each family member as an individual within the family system aided in selection of family session activities and general approach by the group. This case continually reaffirmed the idea that each person and family system responds to experiences very differently as a whole and as individuals within the family system, and that any approach must be tailored specifically to their presented needs.

Clinical Approach

Over the course of approximately one year, the treatment team met with the family on a near-weekly basis. The appointments were a mix of individual or family sessions dependent on client and clinician availability. If one child’s therapist was unavailable, the group would often engage in a family session to decrease the expressed and exhibited disappointment of being ‘left out’. The involvement of multiple therapists facilitated this approach and allowed for greater continuity of sessions for the family. Given the myriad of people that had come into and out of this family’s life over the course of their experienced traumas, immigration to Canada and subsequent period of settling, it was seen as important that the family experience as much continuity and consistency as possible with the Centre.

The case as a whole was approached with a trauma-informed lens, specific to the presenting needs of the client(s). A multi-modal approach was utilized including: attachment-focused, solution-focused, play therapy, narrative therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Each child was considered both individually and as part of the family system. This was important as the family experienced several of their traumas together, but their reported responses have varied widely since the initial incident. A key component to the use of multiple therapists was the debriefing period. This occurred on two levels: peer-to-peer and clinical supervision with the trauma expert.

The peer-to-peer debriefing was a significant aid in developing a more rounded understanding of the family’s experiences. This allowed the treatment team to put together a more complete timeline of the family’s initial and subsequent traumas. This form of debriefing also helped in normalizing some of the experiences of each clinician.

The clinical supervision was paramount in expanding the treatment team’s understandings of the family’s experiences and responses. The supervision included a review of each session and discussion regarding possible linkages within the case and plans for next steps. The supervisor also provided multiple opportunities for self-reflection that allowed for clinician growth. The use of effective clinical supervision and support was vital in ensuring that the practitioners themselves did not experience secondary trauma or compassion fatigue given the profound violence of the family’s trauma experience.

Individual sessions emphasized the development of rapport and comfort for a lengthy period of time. As well, the children and family themselves were consulted and their lead was followed in terms of readiness for the initiation of a trauma assessment and subsequent treatment. This progression was particularly challenging and was a point of difficulty for several of the clinicians. It was not unusual for the group to have a consensus that the children were ‘ready’ for trauma-related work but there continued to be considerable concern for parent/caregiver readiness. Ongoing impact of the family’s trauma was being reported by the family’s matriarch.

Despite the Centre’s best efforts to facilitate treatment and minimize the impact of these challenges, the language barrier, cultural difference and other unknown factors may still have contributed to this not being feasible. The clinical team felt that for the children’s progress to continue there was significant need for consistent parent support and readiness. Efforts were made to engage the mother, but challenges relating to her need for tangible items like money, in combination with the previously identified barriers, made these efforts even more difficult. This consequently impeded the trauma-specific work with the younger siblings. With consistent attention to the client’s level of comfort and emotional regulation, discussions regarding the experienced trauma were broached with the adolescent. This was done because it was determined that parental readiness was not as significant a concern given the adultified role this youth played within the home. As such, a trauma assessment and a narrative were started with the adolescent.

Yet again, translation proved to be complex. Typically this activity with an adolescent would also include delving further into the experience of each symptom in terms of frequency, duration, intensity and triggers. However, due to limitations in session length the language-barriers the activity was simplified slightly. The adolescent/adult list of symptoms was used with the child approach of stickers and simplified questions related to frequency and views regarding perceived size of concern. Once the identification of symptoms was complete, the next step was a rating of severity for the adolescent whereby she was tasked with placing her identified triggers in order. Interestingly, the symptoms which were identified as the most distressing were not necessarily those previously identified as having the greatest level of severity of occurrence.

It is important to note that these symptom identification and rating tasks were done in separate appointments. They were also accompanied with a wrap-up activity geared toward emotion re-regulation. Cues were taken from the adolescent, who was quite open with how she felt, what she thought would be helpful and the impact of the discussions on her mood. Work on the trauma narrative began following the symptom assessment and examination of the client’s willingness to engage with the therapists.

When treatment was nearing the 1 year mark there was a case conference to discuss further ways to support the family with community partners present. At this meeting, Centre staff were notified of the mother’s expressed intent to terminate her involvement with counselling services for her children. As such, a termination session was planned. Due to the abrupt termination of services the trauma narrative was not completed with the adolescent. Discussion occurred with the eldest child about the availability of services and supports from other agencies (due to aging out) in the future should she wish. The termination session was designed to be a celebration of the work done with the family. Practitioners provided small gifts for the family and each clinician wrote a small note to their client to wish them well.

Discussion and Recommendations

Clinical dilemmas.

Throughout the course of this family’s involvement at the Centre, the team encountered various clinical dilemmas, particularly related to the barriers of communication and transportation. From the point of intake, it was difficult to obtain a consistent Swahili interpreter. Members of the team were able to communicate effectively with the children in French, but it remained quite difficult to communicate with the mother, since her French- and English-language skills were limited. This contributed to the children progressing in treatment while little or no emotional support or treatment was being provided to the mother. This was in direct contradiction to the general practice at the Centre. In this case, meeting the mother’s mental health needs was highly challenging.

Another clinical dilemma was the occasional utilization of the oldest child for translation purposes. There was an interesting dynamic, because the oldest child reported not wanting to interpret consistently, but then was also resistant at times to someone outside the family providing translation services when it was available. Using a family member for interpretation is discouraged in the literature. The oldest child was at the Centre to access her own mental health treatment, not to translate for others. Also, via translation she was privy to sensitive adult information.

An additional clinical dilemma related to communication was the practice of signing consents and releases. When involved staff discussed consent forms, releases of information and the risks/benefits of treatment with the mother, someone translated the information in Swahili. The first few times, the mother stated that she understood and signed. As time passed, the mother seemed to grow concerned about the number of forms she was signing. Towards the end of treatment, the mother was quite uncomfortable signing any forms, even if staff went to great lengths to assure her why that information needed to be requested. As a result, once the initial releases expired, staff were no longer able to consult with other involved community agencies.

There were also many sessions that the mother did not attend. If it was a week that the therapists had prepared a family activity, she was unable to participate. Although staff had arranged a consistent transportation provider, the mother was not always at the pick up site. Staff speculated that this could be due to the mother not being actively engaged in her children’s treatment (due limited understanding or frustration over perceived lack of progress), or the mother’s potential disinterest in participating in family sessions. As a result, staff were put into a situation where they needed to go against the Centre’s policy of having the guardian in the Centre at all times in case of emergency. Many sessions occurred with just the children and their driver who became somewhat of a surrogate caregiver throughout the course of treatment.

This case emphasized the importance of recognizing all the successes that have occurred. First, the ability and willingness of the service coordinator to advocate for the family, to remain involved for a longer period of time, to meet the family’s basic needs and to develop a creative approach that enabled the family to remain engaged for a full year.

Second, the team found that the ongoing flexibility within the Centre was an area of significant contribution to success. This case demonstrated the importance and ability to place emphasis on the needs of the client and to facilitate services around those needs. While this sounds simple, it can be challenging given the pressure on many agencies to decrease wait lists, increase measurable outcomes and decrease length of treatment. Specifically for this case, flexibility included the use of a personalized waiting room, engagement of a specialized therapist from another community agency, facilitation of that therapist’s services being provided at the Centre, and the use of a multi-therapist model.

The ability to meet the family’s basic needs in session (organization of transportation, provision of snacks/meals) and out of session (donations, provision of groceries, gifts of winter wear) was understandably important. Based on comments from the family, it would seem that the Centre’s ability to provide these tangible items played a role in developing the rapport and engagement of the family’s matriarch. This was crucial to the children’s attendance and participation.

Finally, significant portions of the sense of success for this case can be connected to the regular access to peer and clinical supervision. The risks of compassion fatigue and secondary trauma are well identified within the literature. With this in mind, and given the extensive traumas experienced by this family as a whole and individually, the level of support for the clinicians internally (within the treatment team) and externally (access to a trauma expert and regular access to the management team as needed) was paramount. These supports allowed each practitioner to provide more to the clients: more support, more engagement and more energy.

Proposed Changes: Agency and Community

While success was experienced with this family, the impact of this case has simultaneously demonstrated that there is room for change. In some ways it felt as though the team encountered a gap in available supports and services at each turn. A common commentary from team members emphasized experienced confusion, frustration and disappointment as well as a recognition of how much more challenging this would be for individuals who do not fully understand the systems, the culture, the language or the expectations being placed on them. With this in mind, several areas of change within the Centre and the community have been identified.

Within the Centre, identified needs included the development of a toolkit and system for handling complex new immigrant families. The needs of new refugee and immigrant families are becoming bigger, and the world is seemingly becoming smaller. There is a responsibility as practitioners, and as an agency as a whole, to be prepared to meet the needs of the families presenting for services. Further, easy access to up-to-date information about language services, settlement agencies, transportation supports and ways to meet families’ basic needs for food, shelter and financial support will be imperative. Additionally, as was noticed with this family, the provision of tangible items can be of extreme importance in laying the foundation for trust and therapeutic rapport in preparation for the work related to mental and emotional health. It will be important that these families experience decreased wait times.

As well, further education for staff about working with complex new immigrant and refugee families is important. Ideally this education would occur for any staff member with whom the family could have contact. Education is also crucial in relation to the warning signs and potential impacts of vicarious trauma. As an agency, the Centre is seeing an increase in new immigrant and refugee referrals with tremendous experiences of trauma. Professionals will hear these stories repeatedly. A clinician’s ability to support themselves and their colleagues and to be supported by management will, in many cases, influence their ability to truly support their clients.

Within the community, identified needs included increased cohesion between community agencies. As mentioned previously, the difficulty experienced by the practitioners in navigating the settlement, legal, financial and mental health systems serves to clearly identify the multitude of potential barriers for families. Additionally, when the individuals and families that are navigating these systems have experienced a significant trauma (including the overall experience of immigration; L. Kirmayer, personal communication, April 29, 2016) there will be another layer that adds to the complexity of engaging in the system for these families. As such, it will be imperative that community agencies develop methods to ensure consistent, proactive and responsive communication and collaborative work to meet the needs of these families as part of their circle of care. This could also include community-wide engagement with a variety of agencies in a proactive way such as developing a committee that meets regularly to anticipate potential areas of increased need and to be responsive as patterns become apparent. As well, based on the team’s experience there would be significant benefit to the inclusion of consultation related to cultural competency prior to a family beginning services and throughout their engagement.

Finally, the team’s experiences identified a significant gap in availability of translation and interpretation services. Engaging as a community to identify areas of language need and to invest in the necessary training or recruitment within these areas would be vital. As well, emphasis would need to be placed on developing methods to ensure that the translators are not experiencing any vicarious symptoms as a result of their roles given the amount of triggering information they would be likely to hear.

- Basic needs come first . It is essential for an individual or family to feel their basic needs are met before they will be able to dedicate significant mental and emotional energy to resolving or processing any experiences of trauma or other impacts of their experiences. As such, helping a low income client/family with accessing basic needs may be necessary before clinical intervention can occur.

- Language matters . Finding a well-trained professional interpreter is crucial. While family members/informal interpreters may be the only option, these individuals should only be used in an emergency or as a last resort.

- Staff well-being must be considered . Mitigating compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization and burnout is critical for workplaces where employees support trauma survivors (immigrants, refugees or other). The ability of a staff to support these clients will inevitably be impacted by their own mental state. The risk for secondary trauma, compassion fatigue and burnout will be high for staff carrying larger case loads comprised of highly traumatized individuals/families. Further, staff who are trained and feel confident in their skillset will be better able to support these populations long-term.

- Children do not exist in silos . A child exists within their environments (home, school, community). As such, family work is extremely important when supporting traumatized children. The implications of the experienced trauma on members of the family will influence the environment in which the child lives.

- This process is about the client, not the practitioner or their policies . Assessment and treatment with traumatized newcomers can be time consuming and progress may occur very slowly. Innovative interventions must be tailored specifically to clients depending on their needs. While the emphasis is increasingly being placed on outcomes and decreased wait times, it is important that individuals and families be met where they are at instead of rigidly insisting they conform to agency expectations. This will contribute to better outcomes.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

- Ellis, B. H., MacDonald, H. Z., Lincoln, A. K., & Cabral, H. J. (2008). Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: the role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . [ PubMed ]

- Statistics Canada (2013). Immigrations and ethnocultural diversity in Canada . Retrieved from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.pdf .

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Case Study of a Collaborative Approach to Improving Community-Based Services for People with Low Income: Community Caring Collaborative

Download Report

- File Size: 1,128.76 KB

- Published: 2021

Introduction

This case study describes the Community Caring Collaborative (CCC), the backbone organization of a network of community organizations and individuals focused on improving the lives of people and families with low incomes in Washington County, Maine. The CCC supports 45 nonprofit and state government organizations in a variety of ways and brings them together to solve emerging issues facing Washington County.

This case study is part of the State TANF Case Studies project, which is designed to expand the knowledge base on innovative approaches to help people with low incomes, including TANF recipients, prepare for and engage in work and increase their overall stability. Mathematica and its subcontractor, MEF Associates, were contracted by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) to develop descriptive case studies of nine innovative state and local programs. The programs were chosen through a scan of the field and discussions with stakeholders. TANF practitioners and staff of other programs can learn about innovative practices through the case studies. The studies also can expand policymakers’ and researchers’ understanding of programs that support people’s success in work and highlight innovative practices to explore in future research.

The purpose of this case study is to describe the CCC in detail and highlight its key features: where it operates and its context; whom it serves; what services the CCC provides; how it is organized and funded; how it assesses its performance; and promising practices and remaining challenges. The case study concludes with a spotlight section on Family Futures Downeast, a two-generation program designed by the CCC and its partners.

Key Findings and Highlights

- The CCC’s main approach to serving people with low incomes is to build collaborative community initiatives to address emerging needs.

- The CCC’s primary services are convening groups of community service providers or members to build trusting relationships, collaborate, and share information; incubating programs to address emerging community needs; providing training and technical assistance to partner staff on various topics, including how to implement CCC-incubated programs with fidelity; and operating core programs that support multiple partners; for example, programs that remove financial barriers for partners’ participants or cross-sector initiatives.

- Promising practices include building collaboration across diverse organizations, designing and implementing participant-centered programs, building the capacity of partner organizations, and providing flexible funding for activities designed to remove barriers.

To select programs for case studies, the study team, in collaboration with ACF, first identified approaches that showed promise in providing employment-related services to individuals and linking them to wraparound supports, such as child care and transportation. The next step was to hold initial discussions with program leaders to learn more about their programs and gauge their interest in being featured in one of the case studies. Once the list of programs was narrowed, the project team, in collaboration with ACF, selected the final set of case study programs to reflect diversity in geography and focus population.

Two members of the research team visited the CCC office in Machias and an FFD program location in Calais. The two-and-a-half day visit took place in February 2020. The team conducted semi-structured interviews with five staff members from the CCC, four staff members from FFD, and nine staff members from the partner organizations. Team members also conducted in-depth interviews with two participants of the FFD program, reviewed anonymized case files for two other FFD participants, and observed two convenings at the CCC office. The team held a follow-up telephone call with a program leader in July 2020 to learn how the CCC responded to the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Eddins, K., and K. Joyce (2021). “Case study of a collaborative approach to improving community-based services for people with low income: Community Caring Collaborative .” OPRE Report #2021-71, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Publications

- Full Library

- Communities of Practice

- Collective Impact

- Community Engagement

- Collaborative Leadership

- Community Innovation

- Evaluating Impact

- Ending Poverty

- Building Belonging

- Building Youth Futures

- Climate Transitions

- Contact Team

- How We Work

- Join our Team

Resource Library

CASE STUDY | Effective Collaboratives

Collective Impact , Case Studies

By Sylvia Cheuy

Sylvia is a Consulting Director of the Tamarack Institute’s Collective Impact Idea Area and also supports Tamarack’s Community Engagement Idea Area. She is passionate about community change and what becomes possible when residents and various sector leaders share an aspirational vision for their future. Sylvia believes that when the assets of residents and community are recognized and connected they become powerful drivers of community change. Sylvia is an internationally recognized community-builder and trainer. Over the past five years, much of Sylvia’s work has focused on building awareness and capacity in the areas of Collective Impact and Community Engagement throughout North America.

Related Posts

WEBINAR | Talking to your Community about Collective Impact - Making it Real

WEBINAR | Talking to your Community about Collective Impact - Overview

CASE STUDY | Transforming the Coasts of New Brunswick through Community Engagement

Foundations of Collective Impact

Join Tamarack's Sylvia Cheuy, Director of Collective Impact, in this online course designed to establish a foundational understanding of the Collective Impact Framework. Learners will have the opportunity to join Sylvia for monthly small group coaching to get more personalized feedback and insight.

Foundations of Community Engagement

Take our new self-directed online course and build your Community Engagement toolkit at your own pace. Hosted by Lisa Attygalle, Director of Community Engagement, the course will guide you through pre-recorded video lessons, case studies, and practical tools and resources.

Community Building Webinars

Equip yourself for Community Change by joining us for weekly community building webinars and live podcasts

Designing For What's Next

The Designing for What's Next webinar and workshop series is aimed at practitioners looking to understand how to best design their organizations, their strategies, and shape their communities for what is to come as we encounter the changes that emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Equip yourself for Community Change by joining us for weekly community-building webinars and live podcasts

Ending Poverty Pathways Course

Join Vibrant Communities' Natasha Pei, Manager of Cities, in this new five-module course. Topics include Ending Working Poverty, Governments and Communities Ending Poverty, and Big Ideas for Ending Poverty.

Through this course, you'll be guided through reflective questions and exercises that will help you make the most of the course materials and content. This course is designed to help you learn at your own pace as you advocate for and advance high-impact ending poverty pathways in your community.

Asset-Based Community Development 101 Building Your Community Table

Join Heather Keam for our first ABCD 101 virtual workshop designed to shift your thinking so that your community is able to build their own table, and your role becomes the legs which support the table and the community-centred activities that come from it.

Participatory Evaluation: Community-Based Assessment and Strategic Learning Practices

The success of participatory evaluation acknowledges relationship dynamics as central to the process. Join Jean-Marie Chapeau & explore the different types of participatory evaluation, and what it means at the level of community-based work.

Subscribe. Be in the know.

Get the latest updates about community change and building vibrant communities.

- Climate Change & SDGs

- Community Development

Content Types

- Case Studies

- Webinars & Videos

In the spirit of respect, reciprocity, and truth we honour and acknowledge that our work occurs across Turtle Island (North America), which has been home since time immemorial to the ancestors of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples.

Be in the know. Get the latest updates, events and resources about community change.

- Log In

- Join CLN

- RSS Feed

Please log in below to comment and contribute to the Collaborative Leaders Network.

Not a Member? Join CLN .

Join the Collaborative Leaders Network

Members of the Collaborative Leaders Network (CLN) come from all walks of life. We are leaders of businesses and organizations, we are practitioners, and we are community members. What connects us is our belief that collaborative leadership and practices are necessary for solving the complex problems we face in Hawaii. There is no cost to joining CLN, nor any obligation to participate. Membership entitles you to contribute your own ideas and experiences to the site, receive updates, and engage with other collaborative leaders who are finding ways to shape Hawaii for the better.

Already a Member? Log in Now .

Forgot Your Password?

Simply enter your email address below, and a new password will be generated and emailed to you.

- All Categories

- Thoughts on the Collaborative Process

- Ripe for Collaboration

- Help Wanted

- Convener’s Corner

Six Case Studies About Collaboration by the National Park Service

Click here to access a PDF publication, Leading in a Collaborative Environment: Six Case Studies Involving Collaboration and Civic Engagement , published in 2010 by the National Park Service.

Learn about common collaborative themes that emerged from six case studies related to historic and protected lands, including a sacred burial ground, a recreational park, and a national preserve and park. The publication offers suggests strategies on what to do before convening, what it takes to be an effective leader through a collaborative process, and how to build team capacity and relationships.

Publication credit: Jacquelyn L. Tuxill and Nora J. Mitchell, eds. Leading in a Collaborative Environment: Six Case Studies Involving Collaboration and Civic Engagement. Woodstock, VT: Conservation Study Institute, 2010. (For more information: www.nps.gov/csi ).

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

About Idea Bank

This section is a place where facilitators and conveners can discuss ideas and share resources related to collaboration. New postings are always welcome.

Submit an Idea

You are not currently logged in, please log in.

Recent Ideas

A 21st century ahupua'a, regional food security for hawaii nei, politics, science and collaboration, video: robbie alms speaks at the state executive leadership program series, popular ideas, facilitators' credo, collective impact, kuumeaaloha gomes talks about aelike -- a process for individual voice, visibility and validation in groups.

Menu Search site

Homepage > Resources > Case Studies

- Case Studies

The Managing by Network Case Study Program has been part of Managing by Network since 2009.

Federal employees have the opportunity to speak to a success, failure, challenge, opportunity, work-in-progress or vision relative to their work in partnerships and community collaboration.

Our Case Study Catalog showcases the work of federal agencies with more than 500 partner organizations: nonprofits; cooperating associations; local, state and other federal agencies; businesses; universities; museums; local schools; international organizations; and professional alliances.

More than 220 presentations provide models of informal and formal partnerships; of community collaboration with a range of stakeholders; of site-based conservation efforts and landscape-scale alliances.

Case Studies by Year

Kayla Blades, BLM, Grants Management Specialist, Idaho State Office, ID. What is the FASS-ination? An Appreciative Inquiry Approach .

Linda Naoi Goetz, BLM, Archaeologist, Interior Region 7, Upper Colorado Basin, WY. Kemmerer Historic Preservation Commission: Creating a Legacy for the Future .

Chris Otahal, BLM, Wildlife Biologist, Barstow Field Office, CA. Amargosa Vole Recovery Team Partnership .

- Jesse Engebretson, EPA, Social Science Researcher, Office of Research and Development, Great Lakes Toxicology and Ecology Division, MN. Unsheltered Homelessness in Parks and Protected Are as in Northern California

- Liz Smith-Incer, NPS, RTCA Field Office Director for Mississippi and Puerto Rico, MS. Africatown Connections Blueway: Healing Begins by Reclaiming Our Heritage & Happiness

- Andrea Carson, USACE, Small Programs Planner, Regional Environmental Justice Coordinator, CPCX Division Liaison and Regional Silver Jackets Coordinator, Great Lakes & Ohio Division, PA. Making the Connections: Aligning Internally to Partner Externally .

USDA Forest Service

- Danielle Bauman-Epstein, USDA FS, Program Specialist - Grants and Agreements, Six Rivers National Forest, CA. Youth Workforce Development: Two Tribal Partnerships

- Shanna Klein smith, USDA FS, Writer-Editor, National Forest System, Policy Office, ID. Mature and Old-Growth Forests: Partnerships for Success.

- Dessa Dale, USDA FS, Public Engagement Specialist, Mountain Planning Services Group, Regions 1 - 4, MT. Developing a Framework of Support around Partnerships and Relationships for Land Management Planning .

- John Langdon, USDA FS, Partnership Coordinator, Uwharrie & Croatan National Forests, NC. Croatan Fireshed Partnership

- Lacey Hill Kastern, USFWS, Western Lake Superior Coastal Program Biologist, Region 3 Ecological Services, WI. Lake Superior Collaborative: Enhancing a Partnership in the Wisconsin Lake Superior Basin .

- Lauren Miller, USFWS, Social Scientist, R8 Science Applications, NV. Establishing a Climate Network .

John Langdon, USDA FS, Partnership Coordinator, Uwharrie & Croatan National Forests, NC. Croatan Fireshed Partnership.

Matthew Fockler, Socioeconomic Specialist, Great Basin Zone (NV, ID, UT), Reno, NV. Two Mississippi: A Case Study in Private / Public Collaboration

Heather Coleman, Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program Manager, Office of Habitat Conservation, NOAA Fisheries, Silver Spring, MD. EXPRESS: EXpanding Pacific Research and Exploration of Submerged Systems (PDF). Resources: EXPRESS website

Laura Rear McLaughlin, Chief, Stakeholder Services Branch, NOAA/Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, Silver Spring, MD. An Evolution of Water Level Partnerships at NOAA Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS)

Leslie Wolf, NOAA (MbN Class of 2016), Hydrologist, California Coastal Office, West Coast Region, CA; Mary Burke, North Coast Regional Manager, CalTrout. Strong Collaborative Process - A Case Study: The Redwood Creek Estuary Collaborative

Teresa Tucker, Planning & Compliance Lead (Environmental Protection Specialist), Mount Rainier National Park, Ashford, WA. Engaging the Public in Planning : Fryingpan Creek Bridge Replacement Project; Mount Rainier National Park: Nisqually to Paradise Draft Corridor Management Plan (ArcGIS Storymaps)

Connie Chan-Le, Park Ranger, USACE-Los Angeles District, South El Monte, CA and Henry Csaposs, Park Ranger, Los Angeles District, South El Monte, CA. A Second Chance in the Desert: Building partnerships and solutions at Mojave River Dam

Daniel Meden, Biologist, St Paul District (Regional Planning and Environmental Division North), USACE Bettendorf, IA. Iowa River Sustainable Rivers Program

- Philomena West, Assistant Deputy Area Budget Coordinator, Washington Office Research and Development, Fort Washington, MD. A View from the WO: Forest Service Cross Deputy Area Projects (CDAPs) and What It’s Like Working for a National Office

Jo Anna Lutmerding, Biologist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, Migratory Bird Program, Falls Church, VA. Artificial Lighting at Night: What it means for bird conservation and navigating a path forward

Margaret Rheude, Wildlife Biologist, Midwest Regional Office - Migratory Birds, Bloomington, MN. Urban Chimney Swift Conservation: Non-randomizing our acts of conservation

Wayne Nelson-Stastny, Missouri River Recovery Project Leader, Missouri River Coordination Office, Yankton, SD. The Missouri River: A River of Connections, A River of Change .

- Marina Tomer, Research Coordinator, South Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, Norman, OK. Leveraging Partnerships to Close the Science-Usability Gap .

- Nina Hemphill, Aquatic Habitat Management Program Lead, California State Office. Water Quality and Fisheries - Working with Tribes.

Judith Downing, Emergency Management Specialist, Public Information Officer, National Headquarters, Fire and Aviation Management, National Incident Management Organization, CA. Community Wildfire Liaison Programs: What Makes Them Successful.

Max Forgensi, Lands and Minerals Program Manager, Pike-San Isabel National Forests & Cimarron and Comanche National Grasslands, CO. Long-term sustainable management for high-use recreation areas.

Reid Armstrong, Public Affairs Specialist, Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forest and Pawnee National Grassland, CO. Sparking a R/Evolution in Information Delivery

- Tracy Schwartz, Historian, Portland District, OR. Willamette Falls Locks Transfer and Section 106 Consultation

Sarah Gray, Program Assistant, Portland-Vancouver Urban Refuge Program, OR. Nurturing Diversity and Increasing Trust through Youth Employment

Sergio Pierluissi, Regional Partners for Fish and Wildlife Coordinator, Midwest Regional Office, MN. Path to the Uplands Partnership

Sean Vogt, Lahontan Cutthroat Trout Recovery Coordinator, Ecological Services Office, NV. Modernizing Recovery Efforts of Lahontan Cutthroat Trout

Charles Cuvelier, Superintendent, George Washington Memorial Parkway, VA. Evolution of a Partnership

- Jennifer Moore, Coral Recovery Coordinator, NMFS Southeast Regional Office, FL. Mission: Iconic Reefs

Krystyna Bednarczyk, Environmental Policy Advisor, Office of Environment & Energy, Environmental Policy Division

- Karen Nelson, Office of Science Quality and Integrity (OSQI); Youth and Education in Science (YES) office. WI. Growing our Practice: Inward and Outward Journeys

- Marcia deChadenedes, BLM, Collaborative Action & Dispute Resolution (CADR) Program Lead, HQ-210: Division of Decision Support, Planning, and NEPA, CO. San Juan Islands Terrestrial Managers Group

Gorge Refuge Stewards

- Jared Strawderman, Gorge Refuge Stewards, Stewardship & Community Engagement Coordinator, Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge Complex Stevenson, WA & Sarah Williams Brown, USFWS, Community Engagement Specialist, Portland-Vancouver National Wildlife Refuges, Ridgefield, WA. Urban Wildlife Conservation Program: Conserving the future with communities and partners in the Portland-Vancouver Metro area

- Ali Weber-Stover, NOAA WCR, Natural Resources Management Specialist, California Coastal Office, Santa Rosa, CA. Bay Restoration Regulatory Integration Team (BRRIT): Facilitating multi-benefit restoration projects in the San Francisco Bay through enhanced collaboration. With Valary Bloom, USFWS Senior Fish and Wildlife Biologist, San Francisco Bay Delta Fish and Wildlife Office, Sacramento, CA

- Brian Rast, USACE, Lead Silver Jackets Coordinator, Project Manager, Kansas City District, Planning Branch, Kansas City, MO. Partnerships and the Infinite Game of Flood Risk Management.

- Katie Noland, USACE, Social Scientist, Levee Safety Center Risk Communication Team, Washington, DC. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Partnership Pains and Gains Developing the Levee Safety Program Guidance

- Betsy Koncerak, USDA FS, Grants Management Specialist, Pacific Northwest Region, Malheur National Forest, John Day, OR. A Peek Into the Life of a Grants Management Specialist.

- Donna Mattson, USDA FS, Partnerships Team Supervisor, Washington Office, Enterprise Program, Elgin, OR. Dynamic Approach to Sustainable Recreation Strategy Development .

- Kelsey McNicholas, USDA FS, Partnerships and Community Development Coordinator, Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest, Gainesville, GA. Restoring Ourselves Restoring Our Lands: Empowering Educators to Examine Our Role in Equitable Access to Public Lands

- Leslie Hay, USDA FS, Southwestern Region Wildlife Program Leader, Southwestern Region, Regional Office, Albuquerque, NM. J aguar Conservation and Partnerships: One Goal, Many Roads .

- Valary Bloom, USFWS Senior Fish and Wildlife Biologist, San Francisco Bay Delta Fish and Wildlife Office, Sacramento, CA. Facilitating multi-benefit restoration projects in the San Francisco Bay through enhanced collaboration. With Ali Weber-Stover, NOAA WCR, Natural Resources Management Specialist, California Coastal Office, Santa Rosa, CA.

- Jess Collier, USFWS, Fish Biologist, Green Bay Fish & Wildlife Conservation Office, New Franken, WI. Great Lakes Basin Road-Stream Crossing Inventory .

Vermont Agency for Natural Resources

- Kathryn Wrigley, VT ANR, Forest Recreation Specialist, Forestry Division, State Lands Program, Essex Junction, VT. Leveraging Partnerships to Help Manage Backcountry Site Hazard Trees.

- Tye Morgan, BLM, Planner and Environmental Specialist, Medford Field Office-Ashland Resource Area, Medford, OR. Virtual Public Meetings: A Prequel Case Study

- Jennifer Day, Regional Coordinator, Great Lakes Regional Collaboration Team, Ann Arbor, MI. Government Collaboration: Building Collaboration for One NOAA Internally to Facilitate One NOAA Externally

- Evan Sawyer, Drought Coordinator (Natural Resource Management Specialist) NOAA Fisheries, West Coast Region, California Central Valley Office, Sacramento, CA. Sacramento River Science Partnership: Partnering to develop a shared understanding

- Alicia King, Public Affairs and Partnership Staff Officer, Chugach National Forest, Anchorage, AK. Partnership Engagement in Inclusion & Diversity Festival Planning

- Ricardo Lopez, Forest Engineer, Angeles National Forest, Arcadia, CA. Angeles National Forest Collaborative Transit to Trails

- Elizabeth (Liz) Munding, NEPA Planner, Coconino National Forest, Red Rock Ranger District, Sedona, AZ. Oak Creek Watershed Restoration Project: Pullouts, Protection and the Public .

- Lisa Shores, Management Analyst, Office of Regulatory and Management Services; Directives and Regulations, Washington, DC. Embracing Obligation & Increasing Opportunity

- Kevin Kalasz, Fish and Wildlife Biologist/Coastal Program Coordinator, South Florida/Everglades, South Florida Ecological Services Field Office, Big Pine Key, FL. Pine Rockland Conservation Business Plan: It Takes a Community .

Mary (MJ) Byrne, Special Assistant to State Director for RAC, Partnerships, Ed. & Interp., Youth, Volunteering, Idaho State Office, ID. Turning Relationships into Partnerships (including Every Kid Outdoors and Hands on the Land / Teachers on the Land)

Katy Kuhnel, BLM, Outdoor Recreation Planner, Challis Field Office, Idaho State BLM, ID

Rebecca Wong, BLM, Monument Manager, Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument, CA

Katy Kuhnel, Outdoor Recreation Planner, Challis Field Office, Idaho State BLM, ID. Making Community Connections

- Ally Lane, Fish Biologist, West Coast Region, CA, Bridging Data Gaps Through Interagency Coordination

Karl Honkonen, Watershed Forester, Northeast Area/State & Private Forestry, NH. Saco Watershed Collaborative

Rachel Neuenfeldt, Partnership and Community Engagement Specialist, Wayne National Forest, OH, Forest Plan Revision Through Partnerships

Jeanne Stevens, Tribal Relations Specialist, Coconino National Forest, AZ, Springs Monitoring & Restoration Initiative

- Leigh Goldberg , Scholar-in-Residence, One Tam Case Studies

- Caroline Kilbane, Outdoor Recreation Planner, AZ, Lake Havasu Shoreline Sites

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

- Sarah Barrett, Biological Scientist IV and Brie Ochoa, Species Conservation Planning Biologist III, FL, Management Plan Development in the Sunshine

Marin County Parks

- Kevin Wright, Government and External Affairs Coordinator, CA, Yard Smart Marin: Think Before You Spray

- Rebecca Ingram, Social Research Associate, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, HI, Building a Network of Partnerships to Support NOAA’s Integrated Ecosystem Assessment

- Mary Biggs, Resource Assistants Program Liaison, WO, DC, Strengthening Partnerships. Creating Opportunities. The USDA Forest Service Resource Assistants Program

- Debra-Ann Brabazon, USFS, Forest Fire Prevention Education Officer/Fire Information, MI, Engaging Youth: Lessons Learned Along the Path of Growing Relationships

- Coeli Hoover, Research Ecologist, NH, Cat Herding: A Tale of Two Documents

- Dawn McCarthy, Recreation Team Leader, OH, The Baileys Mountain Bike Trail System: Improving Communities Through a Collaborative Vision

- Brooke Burrows, Wildlife Refuge Specialist, MN, Minnesota Valley Trust and the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge & Wetland Management

- Laurie Fairchild, Private Lands Biologist, MN, What to Do When You're Stuck: One Approach to Reimagine and Reconnect Resource Accomplishments with Realities on the Ground

- Todd Jones-Farrand, Science Coordinator, LCC, MO, The Rise and Fall of a Landscape Conservation Cooperative: Lesson for Large-Scale Collaborative Efforts

- Lisa Van Alstyne, Chief, WSFR Policy Branch (F&W Administrator), VA, When a Good Idea Goes Bad: Taking a Risk on an Alternative Approach in WSFR

- Edd (Sherman) Franz, Outdoor Recreation Planner, CO, Community Collaboration: Bureau of Land Management Recreation Program

- Anne Mullan, Endangered Species Biologist, OR, Gravel Mining and ESA Salmonid Recovery: Collaboration in the Willamette River

NPS/Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee

- David Diamond, Executive Coordinator, Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee, MT, Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee (GYCC): A Case Study of More Than 50 Years of Federal Partnership

Partnership and Community Collaboration Academy

- Mary Reece, Manager, Program Development Division, AZ, New Mexico Unit of the Central Arizona Project: An Arranged Marriage

- Dave Cunningham, Partnership Specialist, MT, Friends of the Little Belts

- Danny McBride, USFS, Regional Partnership Coordinator, Intermountain Region 4, UT, Utilizing Partners to Build Partnerships & Capacity

- Erick Stemmerman, Administrative Staff Officer, Olympic National Forest, WA, Storrie Fire Settlement

- Cindy Corsair, Fish and Wildlife Biologist, RI, A Tale of Two Cities: Urban Wildlife Refuge Partnerships in New Haven, CT and Providence, RI

- Heidi Keuler, Fish Habitat Biologist, WI, Fishers and Farmers: Watershed Leaders Network

- Susi von Oettingen, Endangered Species Biologist, NH, Tracking Migrating Roseate Terns: UsingPartners to Find a Needle in a Haystack

Case Study Catalog

2nd nature: a partnership with the national park service and latin america youth center, laura harvey.

Laura Harvey NPS Education Specialist National Capital Region Washington, DC 2nd Nature: A Partnership with the National Park Service and Latin America Youth Center

A Delicate Balance Between Multiple Uses: Sheep vs. Sheep, Andrea Jones

Andrea Jones USFS District Ranger Rio Grande National Forest La Jara, Colorado A Delicate Balance Between Multiple Uses: Sheep vs. Sheep

A Peek Into the Life of a Grants Management Specialist, Betsy Koncerak

Betsy Koncerak USDA FS Grants Management Specialist, Pacific Northwest Region (R6) Malheur National Forest Oregon A peek into the life of a Grants Management Specialist.

A Second Chance in the Desert: Building partnerships and solutions at Mojave River Dam, Connie Chan-Le and Henry Csaposs

Connie Chan-Le and Henry Csaposs, USACE, Park Rangers, Los Angeles District, CA. A Second Chance in the Desert: Building partnerships and solutions at Mojave River Dam. (PDF) Connie Chan-Le and Henry Csaposs USACE Park Rangers Los Angeles District California A Second Chance in the Desert:...

A Tale of Two Cities: Urban Wildlife Refuge Partnerships in New Haven, CT and Providence, RI, Cindy Corsair

Cindy Corsair FWS Fish and Wildlife Biologist Southern New England-New York Bight Coastal Program Rhode Island A Tale of Two Cities: Urban Wildlife Refuge Partnerships in New Haven, CT and Providence, RI

A Tale of Two Projects: What I Learned About Collaboration, Matt McCoy

Matt McCoy BLM Assistant Field Manager Four Rivers Field Office, Boise District Boise, Idaho A Tale of Tw o Projects

A View from the WO: Forest Service Cross Deputy Area Projects (CDAPs) and What It’s Like Working for a National Office, Philomena West

Philomena West USDA Forest Service Assistant Deputy Area Budget Coordinator Washington Office Research and Development Maryland A View from the WO: Forest Service Cross Deputy Area Projects (CDAPs) and What It’s Like Working for a National Office

Adapting Project Design to Local Conditions, Mike Johnson

Mike Johnson BLM Zone Social Scientist New Mexico and Arizona State Offices Adapting Project Design to Local Conditions: Learning on the Fly in an Interagency Collaborative Effort

Adventures in FACA: How USFWS Developed Its Voluntary Guidelines for Wind Energy Development, Rachel London

Rachel London USFWS Fish and Wildlife Biologist Ecological Services Arlington, Virginia Adventures in FACA: How USFWS Developed Its Voluntary Guidelines for Wind Energy Development Additional Resources: USFWS Land Based Wind Energy Guidelines

Africatown Connections Blueway: Healing Begins by Reclaiming Our Heritage & Happiness, Liz Smith-Incer

Liz Smith-Incer NPS RTCA Field Office Director for Mississippi and Puerto Rico Mississippi Africatown Connections Blueway: Healing Begins by Reclaiming Our Heritage & Happiness

Looking for something?

Use the search box above to find a specific case study. You can search by title or presenter's name.

Use the tags to browse by agency, topic, or year the case study was presented.

If you would like to learn more about a case study, please contact the presenter(s).

- MBN Course Schedule

- MBN 2024 Course Notebook

- MBN Requirements and FAQ

- MBN Information for Supervisors

- MBN Tuition

- Managing by Network

- C2P2 2023 Course Notebook

- Workshops, Training and Facilitation Services

- Competencies

Instructional Videos

- Recommended Training

- MBN 2023 Course Notebook

- Hybrid Workplace and Collaboration

- Strategic Partners

Privacy Policy

- Public Domain and Copyright Policy

- Refund Policy

- Subscribe here

Instructors

© 2024 All rights reserved.

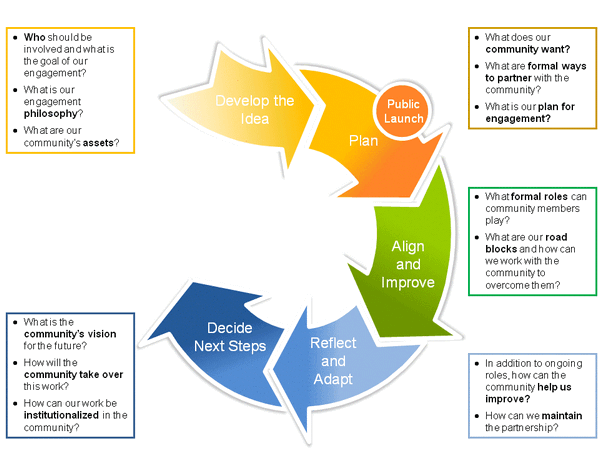

Community Collaborative Life Stages

Related content.

Guide: Capacity and Structure

Guide: The Next Generation of Community Participation

Needle-Moving Community Collaboratives full report

12 Case Studies of Community Collaboratives

Collaboration has long been a part of the social sector. But many have also experienced collaboratives that do not live up to their potential in one way or another—nothing happens between meetings, the group never reaches real agreement, the group loses steam as participants transition in and out, or the collaborative falls apart as participants jockey to claim whatever successes emerge.

There is an exciting groundswell right now in a new kind of collaborative that may hold the key to addressing some of these problems. The overarching difference we have experienced in these collaboratives is seriousness about having real, concrete impact on a community-wide goal. Unsatisfied with small gains for a smaller segment of the population, the leaders of these new collaboratives have put forth ambitious goals and backed them up with long-term investments of resources and effort.

This guide to collaborative life stages can assist community collaboratives to succeed at any stage in their life cycle—from planning and development, through roll-out and course-correcting, and on to deciding their next steps. We have organized it along a five-part timeline based on our extensive research into best practices. The first two sections will help guide new collaboratives in selecting goals and starting out on the right foot. The last three sections will help existing collaboratives stay on track to create the kind of outcomes that are inherently community-changing. Indeed, a hallmark of every successful collaborative is a high aspiration to make a meaningful difference.

With that ambition in mind, this guide to collaborative life stages is for collaboratives that say "yes" to the following questions:

- Do we aim to effect "needle-moving" change (i.e., 10 percent or more) on a community-wide metric?

- Do we believe that a long-term investment (i.e., three to five-plus years) by stakeholders is necessary to achieve success?

- Do we believe that cross-sector engagement is essential for community-wide change?

- Are we committed to using measurable data to set the agenda and improve over time?

- Are we committed to having community members as partners and producers of impact?

Many community efforts do not meet these criteria. Those focused on a single school or small neighborhood project, for instance, are eminently worthwhile. But we have designed this document for cross-sector collaboratives that are taking on social challenges on a community-wide scale.

What's in this guide to collaborative life stages?

- Life stage roadmap: This road map lays out the key stages of a collaborative's development.

- Life stage descriptions: Each life stage section is described and illustrated with the lessons and best-practices learned from our research. The first two stages address how to pull together a collaborative and plan for impact. The last three sections are valuable for collaboratives that are changing goals or wish to incorporate best practices gleaned from successful collaboratives.

Within each life stage section is a core set of resources:

- Introduction: This gives an overview of what happens at each stage.

- Key discussion questions: These are the essential questions a collaborative must grapple with and resolve to move to the next stage.

- Checklists of tasks to complete: These are the building-block activities that collaboratives must master within each stage.

- Potential roadblocks: These are the all-too-common setbacks that collaboratives can encounter, along with suggestions for how to address them and a list of useful resources for assistance.

Additionally, we have included a full list of valuable Web resources, which share proven solutions and highlight organizations that support collaboratives.

Life Stage Map

Collaboratives typically go through a common series of life stages. These are described below, along with a rough indication of their duration.

Develop the Idea (3-6 months)

Community collaboratives evolve out of pressing social needs and some initial thoughts about how to address them. The realization that collaboration is necessary to attack the problem at scale may be recent. Or, it may have come about when a prior set of partnerships has failed to yield significant results.

But whatever its origins, a collaborative needs to learn how to pull together. Therefore, when successfully completed, the "Develop the Idea" stage is characterized by an energized, cohesive core group of partners. This nucleus also develops a clear sense of the issue they want to address and a short list of additional players who should be involved. Typically, the lead convener, i.e., organization or individual(s) that will coordinate the collaborative process, is identified during this stage.

Spearheaded by this lead convener, new or refocused collaboratives often have to immediately address challenges. Not least of these is raising sufficient funds to start to build the staff necessary to support the collaborative process. When raising funds, collaboratives may find funders hesitant because their work is functionally more like overhead than program work. Its impact is indirect and the lines of accountability are less clear. Nonetheless, collaboratives need to identify local stakeholders in the short term who are interested in sustaining the collaborative throughout the "plan" phase.

When done well, this stage begins the formal process of developing a roadmap, which is a detailed action plan for the future, and begins to attract additional players to the collaborative.

Key discussion questions for this stage

- Is my community's history with collaboration positive or negative? How can we use either situation to our advantage?

- What pressing issue or opportunity has brought us together? Will this idea galvanize leaders across sectors in my community?

- Is this issue capable of attracting resources both for direct-service providers and dedicated collaborative capacity?

- What do we know about this issue? What data is out there to help us better understand the issue?

- How does the issue identified by the collaborative fit into the broader context of our community? Are other efforts under way? Are there opportunities for partnership with existing collaboratives? In what ways is our work needed and additive to existing work?

- What core group of people simply has to be at the table to make needle-moving change occur on this issue?

- Is there a trusted, neutral, influential leader - usually an organization - that is coordinating and facilitating the collaborative? Note: This may be your organization.

- How can we foster genuine community partnerships to help us understand the issue and create the necessary support for the interventions needed?

Checklist of key tasks to complete

Bring a core group of stakeholders to the table. (i.e., those interested in and able to drive the early planning and whose engagement is fundamental to the success of the collaborative)

- Include decision makers and funders relevant to the issue in the community: Participants should be either chief executives of organizations or trusted deputies who can take responsibility for the issue and can influence chief executives.

- Start to discuss which key participants need to be at the table: Consider reaching out to the local United Way, mayors or senior city officials, school superintendents, child welfare agencies, relevant nonprofit service providers, area Chambers of Commerce, community foundations, advocates, researchers and the like.

- Ensure that this early planning group includes the core decision makers within the community, without becoming unwieldy.

- Understand that the collaborative will evolve and gain more members during later stages.

Conduct landscape research as needed to understand how to build the collaborative to be effective within the community context.

- Use or undertake research to understand what else is happening in the community, such as the cultural and political landscape and other initiatives or collaboratives focused on similar or related topics.

- Determine if a new collaborative is actually needed; sometimes the right path is to reinvigorate an existing collaborative.

- Engage in conversations with relevant community leaders, residents (including youth, if applicable), business leaders and owners, and funders.

- Aim, ultimately, to understand how the collaborative fits in the broader community context.

Frame the challenge and the problem(s) you will address.

- Based on the results of the landscape review, complete a visioning process with the broader group to further define the core focus of your collaborative.

- Consider creating a high-quality research report, one that can clarify the problem in local terms, gather baseline data for your community, and create a focal point for the public launch.

Identify funding sources for dedicated capacity of the collaborative

- Identify a committed source(s) of funding to sustain the collaborative throughout the Plan phase, during which time there will be no success stories to attract resources.

- Understand current funding condition of collaborative members to determine if some of their current resources can be repurposed to support the collaborative. Please refer to " Capacity and Structure - Funding Examples " for examples of how other collaboratives have raised funds.

Work to secure the right leadership and operational support for the collaborative.

- Select a lead convener organization that will provide significant administrative capacity and resources for the collaborative.