Join our Newsletter

Get helpful tips and the latest information

CBT for Depression: How It Works, Examples, & Effectiveness

Author: Renee Skedel, LPC

Renee Skedel LPCC

Renee Skedel, LPCC, has extensive experience in crisis resolution, suicide risk assessment, and severe mental illness, utilizing CBT and DBT approaches. She’s worked in diverse settings, including hospitals and jails.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression effectively targets negative thought patterns. It’s a short-term therapy for clinical depression that reduces symptoms by helping people recognize unhelpful thoughts and behaviors and replace them with healthier thinking and reacting.

How Does CBT Help Depression?

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a type of psychotherapy that uses a combination of cognitive and behavioral approaches to reduce depression . 1 CBT therapy for depression focuses on changing a person’s feelings to help improve their thoughts and behaviors. CBT therapists may challenge depressive thinking patterns that lead to inaction or self-harming behaviors.

Cognitive Methods to Change Depressive Thinking Patterns

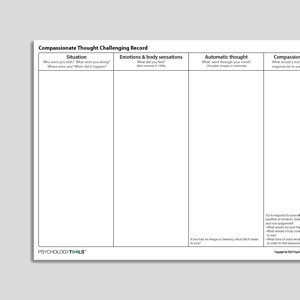

Cognitive methods teach you to challenge negative or irrational thoughts, eventually reducing their power over you. Techniques like cognitive restructuring can help you understand your thought patterns, the emotion behind them, and the actual reality of the situation. A therapist can help present a more realistic perspective to help reduce cognitive distortions . You can also use the free CBT for depression worksheet below to practice cognitive restructuring.

A common cognitive distortion among those with depression is “mind reading,” where you believe you know what others are thinking. By challenging this and other depressive thoughts, you can build a healthier pattern of thinking and self-talk. 1, 2

Cognitive Restructuring for Depression Worksheet

You can recognize unhealthy thought patterns that are making your depression symptoms worse by practicing cognitive restructuring with this worksheet.

Find a Supportive Therapist Who Specializes in CBT.

BetterHelp has over 30,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $65 per week. Take a free online assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you.

Types of CBT for Depression

Cognitive behavioral therapy is not only a treatment type, but it is also the main branch for a number of different therapy styles. There are three common types of CBT used for depression symptoms and episodes.

Along with standard CBT, here are three other common types of CBT used for depression:

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT engages a number of techniques to increase someone’s mental flexibility. ACT for depression can help with reducing the difficulties of negative thoughts and self-talk, anxiety, and judgment, and increase the individual’s ability to focus.

ACT techniques include strategies for each of these pillars: 9

- Acceptance : allowing a thought or feeling to exist without judging it or pushing it away

- Mindfulness: encouraging the individual to be able to focus on the present

- Commitment to behavioral change: if something is not in line with the meaning or values the individual holds, then change this behavior to meet that value

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT)

Similar to ACT, DBT helps people learn how to accept difficult feelings and thoughts. In addition, DBT for depression teaches how to balance between the ability to accept and address irrational thoughts and behaviors to be able to make healthy and maintainable changes in their ability to cope with life’s stressors. 9

DBT is most frequently used to treat those with borderline personality disorder (BPD). However, it was initially developed to treat people who had frequent suicidal thoughts . In addition, those with BPD or bipolar disorder engage in significant amounts of self-harm—regardless of suicidal intent—that can be seen in depressive episodes across disorders.

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT)

In treating depression, rational emotive behavioral therapy (REBT) uses the approach of utilizing the desire to feel happy or fulfilled to reduce depressive symptoms. The REBT approach uses many CBT techniques for depression to help people change their thought processes, helping to create healthier behavior patterns, and eventually helping someone move out of their depressive thoughts and behaviors. 10

REBT was created with the idea that individuals make choices in their lives to meet needs that allow them to survive and feel fulfilled. In turn, REBT teaches individuals how to address irrational and unhealthy behaviors and thoughts so that they can change them for a more functional and fulfilling life.

Behavioral Methods

Behavioral methods are highly effective in treating depression. They typically involve rewarding yourself for small behavioral changes. For example, depression can cause a lack of motivation or low energy. By rewarding yourself for engaging in a task like putting away a dish or two, you change the chemical outputs in your brain. Adding a reward makes you more likely to repeat the behavior in the future. 1

CBT employs several methods to reduce the power of not engaging in behaviors as well, like reducing self-harming or self-sabotaging behaviors that often accompany depression.

What Types of Depression Can CBT Treat?

Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression can be an effective treatment for various depressive disorders and episodes that may be impacting your life, especially in the mild to moderate range of symptoms. 3

CBT can be effective in treating these types of depression: 3

- Major depressive disorder (clinical depression)

- Persistent depressive disorder (PDD)

- Seasonal affective disorder

- Postpartum depression

- The depressive episodes of bipolar disorder

- Situational depression

- Schizoaffective disorder, depressive type

9 Common CBT Techniques for Depression

Common CBT techniques used for depression include cognitive restructuring, thought journaling, and mindful meditation. Many of these techniques are used together to show the connections between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

Here are nine common CBT techniques for depression: 2

1. Cognitive Restructuring

In challenging your thought patterns, tone, and self-talk, you learn about potential cognitive distortions and unhealthy thought patterns that could be increasing depressive emotions or suicidal thoughts. Cognitive restructuring , sometimes called reframing, forms healthier thought patterns, reduces cognitive errors, and helps you practice ways to rationalize distortions and untrue beliefs.

Here’s how to try the five steps to cognitive restructuring:

- Set up your list: draw a line down the middle of a piece of paper. Title the left-hand column “Unproductive Thoughts” and title the right-hand column “Replacement Thoughts.”

- Write down your unproductive thoughts: on the left-hand side of your paper, list your negative and self-critical thoughts, or any automatic thoughts you have regularly that make you unhappy, something like “I can’t do anything right.”

- Identify your replacement thoughts: for each of your unproductive thoughts, create a replacement thought and write it down on the right side of your paper, such as “Here’s a project I did well.”

- Review your list regularly: so you begin to memorize the unproductive thoughts and their replacement thoughts.

- Notice your thoughts in real time: pay attention to your thoughts throughout each day. When you think of one of your unproductive thoughts, stop yourself and remind yourself of the replacement thought. With practice, you’ll begin to challenge your unproductive thoughts and naturally start to replace them with rational ones.

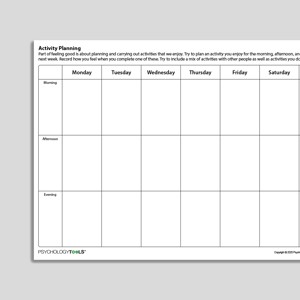

2. Activity Scheduling

Activity scheduling involves rewarding yourself for scheduling activities that encourage positive experiences and self-care. By scheduling these activities and rewards, you learn to motivate yourself to complete necessary tasks even when you are feeling low. It also increases the chances of continuing to complete these tasks after you end your formal therapy sessions.

3. Thought Journaling

By journaling for mental health , exploring things like your emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, you create a space to process and identify any potential triggers, as well as how your thoughts have been influencing your behavior. This can increase self-awareness and help you learn coping techniques to use in the future. 4 You can also use specific journal prompts for depression to understand more where your beliefs and moods have been coming from.

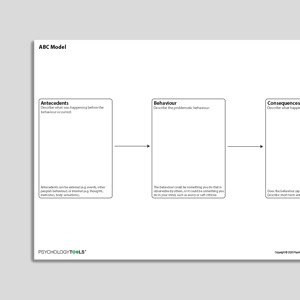

4. ABC Analysis

Similar to journaling, the ABC model is solely focused on breaking down the behaviors that are related to depression, like snapping at people or sleeping all day. In analyzing your triggers and consequences, you can explore the “consequential” behaviors and look to find common causes in your depressive triggers.

The ABC model works by using the following structure:

- The “Activating” event

- Your “Beliefs” about that event

- The “Consequences” of the event, including your feelings and behaviors surrounding the event

5. Fact-checking

Fact-checking encourages you to review your thoughts and understand that, while you may be stuck in a depressive or harmful thought pattern, these thoughts are not facts but opinions based on your emotions (e.g., “I am a failure”). Fact-checking can also help you identify what behaviors you engage in due to your opinions or emotions instead of the actual facts.

6. Successive Approximation or “Breaking It Down”

Breaking down large tasks into smaller goals will help you feel less overwhelmed. By practicing successive approximation, you will be more likely to complete your goals and be better able to cope with large tasks in the future, even during times when your depression is heightened.

7. Mindful Meditation

By engaging in meditation for depression , you will learn to reduce focus on negative thoughts and increase your ability to remain in the present. Meditation can help you recognize and learn to accept your negative thought patterns and detach from them instead of letting them take over.

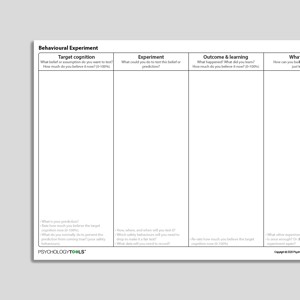

8. Behavioral Experiments

Therapists use behavioral experiments as a tool for challenging irrational thought patterns that may be contributing to your depression. You’ll learn how to replace these thoughts with healthier thoughts. By engaging in these experiments, you can spot and learn to stop catastrophic thinking and develop a more realistic view of the world.

9. Role Play

Your therapist may have you role play a specific situation you find challenging. You will act out the situation alongside the therapist, while learning to practice healthier responses and depression coping mechanisms . Role playing helps you gain a better understanding of your emotional responses and how to manage your reactions in a real-life situation.

Talkspace - Online Therapy and Medication Management

Your therapist can help you process thoughts and feelings, understand motivations, and develop coping skills. Covered by most major insurance plans. Try Talkspace

Examples of CBT for Depression

CBT uses cognitive and behavioral techniques to improve depression symptoms , but the exact CBT treatment plan for depression might depend on the type of depression someone is experiencing.

CBT For Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Example

Jody, a 35-year-old female, has recently started to feel tired all the time. This began about two and a half weeks ago. Along with “sleeping all the time,” she reports these other symptoms that all started around the same time.

Those symptoms include:

- Experiencing negative thoughts

- Constantly worrying about different aspects of her life

- Finding it difficult to stay still

- Does not have an appetite

- Has generally been feeling sad, hopeless, irritable, and numb

She reports that she had also felt this way in her teens and mid-20’s; and she also experienced brief suicidal thoughts in her 20’s.

Jody began meeting with her therapist and the therapist diagnosed major depressive disorder after they finished their assessment. During sessions, her therapist began asking her to think about what thoughts are making her feel sad and to change her thought process. She also recommended journaling every day.

Part of the journaling homework includes documenting something that she chose to do to make her feel happy or productive daily, a CBT technique called behavioral activation. When Jody started reporting an increase in her worry and rumination , the therapist encouraged her to add meditation to her daily work, to help reduce the incessant worrying and increase calm in Jody’s mind. 1, 5

CBT For Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) Example

Matt, a 28-year-old male, has been experiencing a low and depressed mood, difficulty sleeping, low self-esteem , and difficulty with concentration for the last two and a half years. He works a difficult job and felt it was related, but was informed by family that they noticed this low-grade depression even when he was in less stressful positions.

Matt reached out to a therapist, who diagnosed him with persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) . 1, 5, 6, 7 His therapist began working with him on journaling about his day on a regular basis, especially if something made him happy. The therapist encouraged him to write down and challenge his negative and irrational thoughts.

Matt and his therapist also worked on noting triggers for aggressive thoughts towards himself to increase his awareness. Matt’s therapist began encouraging him to engage in problem-solving tasks to help him function and build resilience when his depressive symptoms flared up. 1

CBT For Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) & Situational Depression Example

Jamie, a 37-year-old male, began experiencing depressive moods, difficulty concentrating, increased fatigue, lowered energy, feeling tense, and negative thoughts in his early 20’s. He reports that he never reached out for help because even if the symptoms tended to start in October to November almost every year, they always stopped around March.

This year, Jamie’s symptoms began around the same time, although he noticed that his negative thoughts were worse than normal and that his sleep schedule was off. As a result, he reached out to a local therapist, who diagnosed Jamie with “unspecified depressive disorder with seasonal pattern,” which is more commonly known as seasonal affective disorder (SAD) . 7

Jamie’s therapist began working with him to reduce the impact of his symptoms by having him engage in regular meditation to reduce his anxiety and challenge his thoughts outside of session to reduce the negative thought patterns impacting his perspective.

They also worked together to create a daily schedule of activities to help increase self-fulfillment and self-care , and journaling to increase acknowledgement of positive things during the difficult season, as well as to track Jamie’s mood. 1, 5, 7

CBT For Postpartum Depression Example

Julia, a 32-year-old female, had her baby about three weeks ago. About two weeks ago, Julia began experiencing significant levels of anxiety, panic attacks, low mood, feelings of depression and worthlessness, and loneliness . This was Julia’s first child and she had never experienced these feelings before, nor had anyone else in her family. 1, 7

Julia sought out a therapist to figure out her feelings and was diagnosed with “unspecified depressive disorder with peripartum onset,” more commonly known as postpartum depression . Her therapist knew that research indicated that CBT had improved long- and short-term symptoms of depression and had some impact on anxiety in postnatal depression. 8

Julia’s therapist encouraged her to journal her feelings each day to increase awareness as well as acknowledge the positive things she was doing.

She also had her engage in a daily short meditation and breathing regulation technique to lower anxiety and panic attacks, engage in gratitude practices with her journaling to increase her mood and lower depressive symptoms, and to discuss her emotional concerns with her support system and partner to allow herself time to meet her own needs.

Julia was encouraged to explore her thought patterns influencing the anxious thoughts, especially leading up to panic attacks, to help reduce anxiety and become more aware of her triggers to be able to feel comfortable with her baby. 4, 9

How Effective Is CBT for Depression?

Cognitive therapy can be as effective as depression medication in initially treating moderate to severe depression, although its success often relies on the therapist’s level of experience. Studies show that when CBT is delivered by skilled therapists, it can lead to substantial improvements in depressive symptoms. 11

Other research studies have proven the effectiveness of CBT for depression:

- Studies show that the behavioral activation techniques used in CBT are useful in the treatment of those with severe depression. 5

- When compared to antidepressant medication, CBT alone may be effective in continued recovery for depression. 5

- Cognitive therapy shares efficacy with medication in treating moderate to severe major depressive disorder, although this can be impacted by the level of the therapist’s experience with CT/CBT. 11

- CBT was found to be an effective intervention in lowering depressive symptoms and depression relapse rates, especially in comparison with a control group. 12

- A study on bipolar disorder, including depressive episodes and symptoms, found that the group with CBT treatment had fewer bipolar episodes, shorter bipolar episodes, and less hospitalization admissions. In addition, this group’s depressed mood and mania symptoms were noted to be significantly lower. 13

Would You Like to Try CBT Therapy?

What to Expect During CBT Treatment

Those seeking CBT for depression will typically attend 12-20 weekly sessions, although many will experience improvements after just a few sessions. CBT treatments can be done in-person or with a CBT therapist online. 14 Most insurance companies cover CBT to help reduce the cost, but if paying out of pocket, you can expect to pay between $100 and $200 per session.

While CBT may involve some rigor and homework, CBT treatment was intended to be short-term to allow people to thrive with the help of their therapist, but then on their own. Each CBT session will generally last about 50 to 55 minutes, and happen once a week. The format of each session is usually quite structured.

Each CBT session consists of: 13

- Setting a goal or a problem to process for that day

- Working on the problem reported (this might include processing barriers in the problem as well as the person’s thoughts on these)

- Creating an action plan to address the problem in and out of session

- Measuring the person’s movement on the problem (like discussing homework, a reported issue, communication, etc.)

While this may not always be the case in a CBT treatment plan or the model of every single session, this is the expectation for treatment. Your therapist may take some different approaches, but CBT treatment tends to be short-term and active in attempting to reduce the impact of your mental health symptoms on your life.

How to Find a CBT Therapist

If you’re wondering how to choose a therapist , ask your primary care provider or a trusted loved one for a list of recommendations. You can also search a local therapist directory to find a licensed CBT provider in your state who specializes in CBT for depression. Many therapists now offer video-based therapy that has enabled many people to get CBT online .

If you’re ready to begin online CBT, Online-Therapy.com is an excellent choice for those without insurance. There are also several online therapy options that take insurance .

At-Home Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Exercises For Depression

While you should always seek help from a professional if you think you may have depression, there are CBT exercises you can try on your own or through the use of CBT apps to help relieve mild symptoms, like journaling, scheduling out activities you enjoy, and starting a gratitude practice. A therapist can also help you develop these techniques so you’ll be prepared when depressive symptoms arise.

Here are some at-home CBT exercises for depression: 3

Even if you aren’t seeing a therapist, keeping a journal of your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors can be helpful. Through writing in a notebook or through a journaling app like the Sensa app , you may begin to learn more about yourself and identify difficulties that regularly impact you. This way, you can prepare for them in the future. 4

Schedule Enjoyable Activities

Have events scheduled that improve your mood, like concerts, lunch dates with friends, or road trips. Even on a smaller scale like making a general to-do list, scheduling can inspire you to keep moving forward.

Try Meditation

Meditation can be helpful in managing your emotions, decompressing, and even falling asleep. It has been proven to help with addiction, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and more. If you’re not sure where to start, using meditation apps and free videos available online can help you clear your mind and connect to the present.

Practice Challenging Your Thoughts

You might want to start this practice in a journal, but it is also helpful to challenge or reframe your thinking in the moment. By reframing thoughts or saying affirmations in your head, you may be able to learn to stop negative thoughts in their tracks.

Start a Gratitude Practice

It might feel difficult at times, but it’s helpful to identify the positives in your life. One study showed that the use of gratitude helped to significantly reduce continuous negative thought processes (and reduced the risk of negative thoughts in individuals experiencing anxiety and depression ). 14 It can help to try writing three things you’re grateful for every day.

In My Experience

“In my experience, CBT can help with depression symptoms in many ways. In accessing CBT services, whether through a therapist or by practicing at-home skills, you can start feeling a bit better and getting back to the things that are most important to you.”

Choosing Therapy strives to provide our readers with mental health content that is accurate and actionable. We have high standards for what can be cited within our articles. Acceptable sources include government agencies, universities and colleges, scholarly journals, industry and professional associations, and other high-integrity sources of mental health journalism. Learn more by reviewing our full editorial policy .

Cognitive behavioral therapy EXERCISES Los ANGELES: CBT INTERVENTIONS. (2020). Retrieved from https://cogbtherapy.com/cognitive-behavioral-therapy-exercises

Fenn, K., & Byrne, M. (2013). The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. InnovAiT, 6(9), 579–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755738012471029

Gautam, M., Tripathi, A., Deshmukh, D., & Gaur, M. (2020). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(8), 223. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_772_19

Utley, A., & Garza, Y. (2011). The therapeutic use of journaling with adolescents. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 6(1), 29-41.

Chand, S. P., & Maerov, P. J. (2019, March 28). Using CBT effectively for treating depression and anxiety. Retrieved from https://www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/82695/anxiety-disorders/using-cbt-effectively-treating-depression-and-anxiety/page/0/2

Publishing, H. (2014, March). Dysthymia. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/dysthymia

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Huang, L., Zhao, Y., Qiang, C., & Fan, B. (2018). Is cognitive behavioral therapy a better choice for women with postnatal depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 13(10), e0205243. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205243

Mike, D. (2016, February 8). Know the 3 Major Types of Therapy – CBT, ACT, DBT. Boca Raton Psychiatrist | Florida Psychologists. Retrieved November 13, 2021, from https://drmikemd.com/understanding-the-3-major-types-of-therapy-cbt-act-dbt

Ellis, A., & Joffe Ellis, D. (2019). Introduction. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (2nd Ed.)., 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000134-001

DeRubeis, R. J., Hollon, S. D., Amsterdam, J. D., Shelton, R. C., Young, P. R., Salomon, R. M., O’Reardon, J. P., Lovett, M. L., Gladis, M. M., Brown, L. L., & Gallop, R. (2005). Cognitive Therapy vs Medications in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4), 409. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409

Li, J. M., Zhang, Y., Su, W. J., Liu, L. L., Gong, H., Peng, W., & Jiang, C. L. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 268, 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.020

Lam, D. H., Watkins, E. R., Hayward, P., Bright, J., Wright, K., Kerr, N., Parr-Davis, G., & Sham, P. (2003). A Randomized Controlled Study of Cognitive Therapy for Relapse Prevention for Bipolar Affective Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.145

What is a CBT Session Like? (2021, August 3). Beck Institute Cares. Retrieved November 16, 2021, from https://cares.beckinstitute.org/about-cbt/what-are-sessions-like/

We regularly update the articles on ChoosingTherapy.com to ensure we continue to reflect scientific consensus on the topics we cover, to incorporate new research into our articles, and to better answer our audience’s questions. When our content undergoes a significant revision, we summarize the changes that were made and the date on which they occurred. We also record the authors and medical reviewers who contributed to previous versions of the article. Read more about our editorial policies here .

Your Voice Matters

Can't find what you're looking for.

Request an article! Tell ChoosingTherapy.com’s editorial team what questions you have about mental health, emotional wellness, relationships, and parenting. The therapists who write for us love answering your questions!

Leave your feedback for our editors.

Share your feedback on this article with our editors. If there’s something we missed or something we could improve on, we’d love to hear it.

Our writers and editors love compliments, too. :)

Frequently Asked Questions

How much does cbt cost.

CBT sessions generally cost about $100 to $200 out of pocket. Your insurance may cover it depending on their coverage for mental health treatments. If covered, insurance can reduce CBT sessions to around $25 to $75 each. If you’re considering CBT group therapy , the cost can be significantly lower. Group sessions tend to range from $25 to $50 per person, depending on the provider.

Additional Resources

To help our readers take the next step in their mental health journey, Choosing Therapy has partnered with leaders in mental health and wellness. Choosing Therapy is compensated for marketing by the companies included below.

Talk Therapy

Online-Therapy.com – Get support and guidance from a licensed therapist. Online-Therapy.com provides 45 minute weekly video sessions and unlimited text messaging with your therapist for only $64/week. Get Started

Online Psychiatry

Hims / Hers If you’re living with anxiety or depression, finding the right medication match may make all the difference. Connect with a licensed healthcare provider in just 12 – 48 hours. Explore FDA-approved treatment options and get free shipping, if prescribed. No insurance required. Get Started

Depression Newsletter

A free newsletter from Choosing Therapy for those impacted by depression. Get helpful tips and the latest information. Sign Up

Learn Anti-Stress & Relaxation Techniques

Mindfulness.com – Change your life by practicing mindfulness. In a few minutes a day, you can start developing mindfulness and meditation skills. Free Trial

Choosing Therapy Directory

You can search for therapists by specialty, experience, insurance, or price, and location. Find a therapist today.

Online Depression Test

A few questions from Talkiatry can help you understand your symptoms and give you a recommendation for what to do next.

Best Online Psychiatry Services

Online psychiatry, sometimes called telepsychiatry, platforms offer medication management by phone, video, or secure messaging for a variety of mental health conditions. In some cases, online psychiatry may be more affordable than seeing an in-person provider. Mental health treatment has expanded to include many online psychiatry and therapy services. With so many choices, it can feel overwhelming to find the one that is right for you.

CBT for Depression Infographics

Find a therapist in your state

Get the help you need from a therapist near you

California Connecticut Colorado Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kentucky Maryland Massachusetts Michigan New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Pennsylvania Texas Virginia

Are you a Therapist? Get Listed Today

A free newsletter for those impacted by depression. Get helpful tips and the latest information.

FOR IMMEDIATE HELP CALL:

Medical Emergency: 911

Suicide Hotline: 988

© 2024 Choosing Therapy, Inc. All rights reserved.

| published: | 2 Sep 2022 |

|---|---|

| updated: | 8 Jun 2024 |

- Psychology & Counseling Tools

9 CBT Worksheets and Tools for Anxiety and Depression

CBT is one of the most effective psychological treatments when it comes to managing anxiety and depression, and can be a highly useful approach to apply in online therapy.

If you help clients tackle cognitive distortions and unhelpful thinking styles, we’ve compiled a list of essential worksheets that should be part of your therapy toolbox.

How To Use CBT Worksheets in Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is based on the idea that thoughts, feelings, physical sensations and behaviors are interlinked, and that changing negative thought patterns can enhance the way we act and feel.

It encompasses a variety of techniques and interventions that have been proven effective in the treatment of many mental disorders.

Besides anxiety and depression, a few examples include: [1]

- Panic disorder

- Bipolar disorder

- Borderline personality disorder, and

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

With the advent of online therapy, guided online CBT has become an increasingly popular way for mental health professionals to help clients manage behavioral health conditions without the need to meet in person as often.

CBT worksheets, exercises, and activities play a large role in these treatments to encourage further progress between sessions, in the same way that face-to-face CBT involves between-session practice. [2]

The Importance of Tailoring CBT Worksheets to Individual Needs

While CBT worksheets are effective tools, it is crucial to tailor these resources to the unique needs of each client.

Every individual’s experience with anxiety and depression is different, and a one-size-fits-all approach may not be as effective. Personalization involves understanding the specific triggers, thought patterns, and behaviors of a client.

For instance, a client struggling with social anxiety may benefit more from worksheets focusing on exposure and social skills training, while someone with generalized anxiety disorder might need tools aimed at managing worry and improving relaxation techniques.

Customizing worksheets also means considering the client’s cultural background, personal preferences, and level of cognitive functioning.

This tailored approach not only enhances the therapeutic alliance but also ensures that the interventions are more impactful, leading to better outcomes.

Therapists should regularly review and adjust the worksheets to keep them relevant and aligned with the client’s progress and evolving needs.

5 Example Tools For Treating Anxiety

So what types of online CBT worksheets can be used to help clients cope better with symptoms of anxiety ?

There is a wide spectrum of therapeutic approaches that range from self-help activities to guided interventions, and all of them focus on identifying and changing unhelpful thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Here are a few of the best-known techniques that can be applied with the right tools.

Identifying cognitive distortions

Recognizing and identifying maladaptive automatic thoughts is a main goal of CBT.

Recognizing and identifying maladaptive automatic thoughts is a main goal of CBT. Cognitive distortions describe inaccurate or exaggerated perceptions, beliefs, and thoughts that can contribute to or increase anxiety, so increasing a client’s awareness of these is the first step to unraveling them and feeling better.

Quenza’s Unhelpful Thinking Styles – “Shoulding” and “Musting” worksheet, shown below, is an example exercise that can help clients recognize the damaging impacts of using “should” and “must” statements to place unreasonable demands or unnecessary pressure on themselves.

Cognitive restructuring

Cognitive restructuring involves disputing the distortions that underpin a client’s challenges. Various techniques that can be helpful here include Socratic questioning, decatastrophizing, and disputing troublesome thoughts with facts.

One example CBT exercise is the Cognitive Restructuring Expansion shown below, which can help clients identify automatic thoughts and substitute them with more fair, rational ways of thinking.

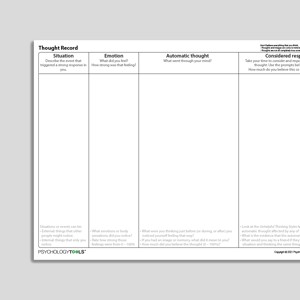

Journaling and thought records

Journaling is a form of self-monitoring that helps clients identify their thought patterns and emotional tendencies, as shown by the Stress Diary Expansion below.

Journals can involve logging negative thoughts or feelings as homework, with the aim of positioning clients to manage them successfully.

Stress Reduction Techniques

Stress reduction exercises such as deep breathing, meditation, and progressive muscle relaxation can all be effective CBT tools for managing anxiety.

The example below is Quenza’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation exercise, which clients can practice to increase their sense of control and calm when stressed or anxious.

Breathing Exercises

Diaphragmatic breathing is another useful relaxation exercise often used in CBT for anxiety.

With this mindfulness practice, clients learn to regulate their breath and activate their body’s relaxation response, as shown in Quenza’s audio Diaphragmatic Breathing exercise below.

CBT Worksheets for Depression (PDF)

CBT worksheets are useful resources for therapists helping clients manage depression, because they can be used to encourage your clients’ progress between sessions.

If you are a mental health professional, the following worksheets can be shared as homework. Each is available as a customizable Quenza Expansion for easy sharing with clients with a $1, 30-day Quenza trial .

The ABC Model of Helpful Behavior

ABC is an acronym for Antecedents, Behavior, and Consequences, and the ABC model proposes that behavior can be learned and unlearned based on association, reward, and punishment.

This CBT worksheet allows clients to reflect on adaptive behavior, thus building their awareness of the triggers for and consequences of this behavior.

After introducing the ABC Model of Behavior and the ABC Model of Helpful Behavior, the exercise asks clients to try it out themselves by:

- Describing a recent personal problem

- Recalling a helpful behavior that they carried out that contributed to the problem in a positive way.

- Recalling the Antecedents of the helpful Behavior – where they were, who they were with, and what they were doing, thinking, and feeling

- Considering the short- and long-term Consequences of that behavior – how they felt, what happened, and what others said or did.

Unhelpful Thinking Styles – Emotional Reasoning

This worksheet invites clients to identify and decrease the negative impact of a specific cognitive bias known as “Emotional Reasoning,” which can be common in clients with depression.

As an introduction, clients learn about the negative impacts of regarding emotions as evidence of the truth, or basing one’s view of situations, yourself, or others on how they feel at a certain moment.

They are then invited to reflect on a time when they used emotional reasoning and describe the situation as well as their thoughts and emotions at the time.

Through self-reflection, this therapy exercise aims to help the user separate their feelings from their thoughts so that they can reduce the negative effect of emotional reasoning on their wellbeing.

De-Catastrophizing

As we’ve seen, patients with symptoms of depression often experience negative thoughts that result from faulty thinking rather than accurate experiences of reality.

Catastrophizing is amplifying the importance of adverse events and situations while minimizing their positive aspects or outcomes. The Decatastrophizing Expansion can be an impactful cognitive restructuring technique to help with this cognitive distortion when it is practiced over time.

Clients are asked to describe the situation that they are currently catastrophizing about before answering a series of questions to challenge their thinking:

- What is the worst that can happen?

- What three events would have to take place for the worst to happen?

- How likely is it that all three of these events will take place?

- What is a more likely outcome, given what you know about the situation?

Here’s an example of the PDF copy that you or your clients can download of these exercises: Decatastrophizing CBT worksheet

To customize these CBT worksheets for depression and browse more, take a look at the $1, 30-day Quenza trial .

Can CBT Help Build Self Esteem?

Studies have shown CBT to be useful in developing a client’s self-esteem so that they start to perceive themselves as more worthy and deserving. [3]

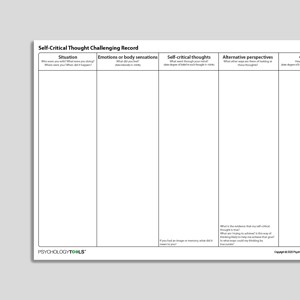

Cognitive restructuring is particularly can equip them with the skills to challenge or refute negative self-talk. This involves:

- Helping clients explore repetitive negative self-talk can be damaging to their sense of self-worth

- Challenging harmful cognitive distortions

- Supporting in the development of a more balanced, positive self-perspective.

Quenza’s Challenging Unhelpful Thoughts , pictured above, is an example CBT worksheet for self-esteem with the following prompts and questions:

- Describe a negative thought that keeps coming back.

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how strongly do you believe this thought to be true?

- What evidence supports this thought?

- What evidence do you have against the thought?

- What would you tell a friend (to help them) who would have the same thought?

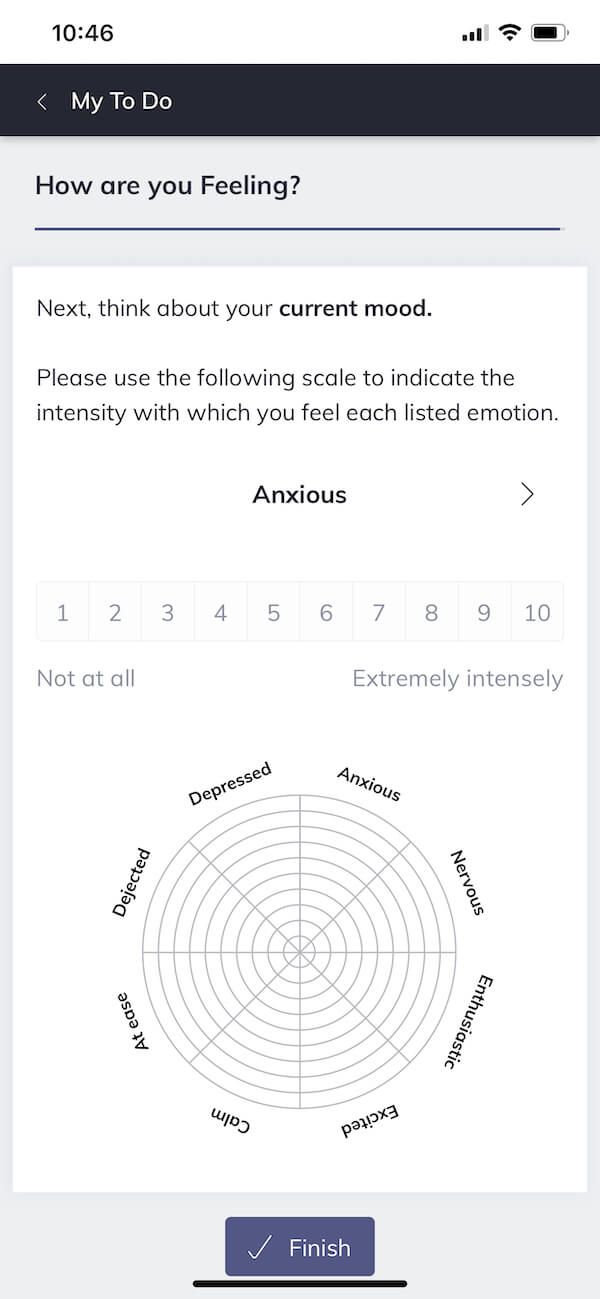

Integrating Technology with CBT Worksheets for Enhanced Engagement

The advent of technology has significantly transformed the landscape of psychological treatments, including CBT.

Digital tools and applications can greatly enhance the engagement and effectiveness of CBT worksheets.

Interactive platforms allow clients to complete worksheets on their devices, providing instant feedback and progress tracking.

Additionally, gamification elements, such as rewards for completing tasks or interactive scenarios, can make the therapy process more engaging and motivating for clients.

Teletherapy platforms can integrate these digital worksheets, allowing therapists to monitor their clients’ progress in real time and make adjustments as needed.

Moreover, digital tools often include additional resources like videos, guided meditations, and forums for peer support, which can complement the worksheets and provide a more holistic approach to treatment.

By leveraging technology, therapists can ensure that CBT remains a dynamic and accessible option for clients, regardless of their location or schedule.

CBT Toolbox for Online Therapists

Once you’ve found the most useful tools for your programs and are ready to start treating clients, it’s time to organize them for easy, convenient delivery.

Without a centralized library of digital materials – and the ability to quickly personalize and share them – it’s easy to spend more time than is necessary on the admin side of helping others.

With the right CBT app , you should have an entire toolbox of CBT worksheets plus the tools you need to deliver them:

- Activity design tools: for efficiently creating online CBT interventions

- Customizable templates: e.g., Quenza Expansions that include personalizable science-based exercises and activities

- Documentation tools: e.g., Quenza Notes – A secure, convenient way to create and store session notes and collaborate with clients

- Pathway builder tools: which help you assemble separate worksheets and tools into programs and mental health treatment plans

- Real-time results tracking: to securely collect and store client responses and results

- A free client app: so that clients can easily receive, complete, and return your CBT resources and assemble a library of their finished activities.

Whether you’re new to the world of online therapy or coaching or simply looking to increase your impact, our free 30-page guide is a great place to start.

This PDF will give you an easy-to-understand introduction to the essentials of digital practice: how to create and share your own CBT interventions, keep clients engaged in their treatment, and improve your clients’ results while growing and scaling your business.

Click here to download your copy of Coach, This Changes Everything .

Final Thoughts

Practicing CBT online for the first time may take some adapting, but the ability to help more clients with less work is always worth the payoff.

Hopefully, these worksheets and resources give you a solid starting point for building your CBT toolkit. Let your fellow practitioners know how you use them – leave a comment and join in the conversation below!

- ^ NHS. (2022). Overview - Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Retrieved from https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/talking-therapies-medicine-treatments/talking-therapies-and-counselling/cognitive-behavioural-therapy-cbt/overview/

- ^ Harvard Health Publishing. (2015). Online cognitive-behavioral therapy: The latest trend in mental health care. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/online-cognitive-behavioral-therapy-the-latest-trend-in-mental-health-care-201511048551

- ^ McKay, M., & Fanning, P. (2016). Self-esteem. New Harbinger.

Leave a reply Cancel

Your email address will not be published.

Download free guide (PDF)

Discover how to engage your clients on autopilot while radically scaling your coaching practice.

Coach, This Changes Everything (Free PDF)

.st0{fill:none;stroke:#000;stroke-width:2;stroke-linecap:round;stroke-linejoin:round;stroke-miterlimit:10} Filter

Resource type

Therapy tool.

Cognitive Distortions – Unhelpful Thinking Styles (Extended)

Information handouts

Cognitive Distortions – Unhelpful Thinking Styles (Common)

Assertive Communication

Therapy Blueprint (Universal)

Subjugation

Thought Record (Evidence For And Against)

Embracing Uncertainty

Choosing Your Values

Intolerance Of Uncertainty

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Developing Self-Compassion

Insufficient Self-Control

Assertive Responses

Unhelpful Thinking Styles (Archived)

Activity Menu

Valued Domains

Using Behavioral Activation To Overcome Depression

Emotions Motivate Actions

Behavioral Activation Activity Diary

Behavioral Experiment (Portrait Format)

Mistrust/Abuse

Values: Connecting To What Matters

Punitiveness

Abandonment

Evaluating Unhelpful Automatic Thoughts

Compassionate Thought Challenging Record

What Keeps Depression Going?

Behavioral Experiment

Exploring Valued Domains

What Is Rumination?

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Mindfulness

CBT Appraisal Model

Failure To Achieve

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Client Workbook

Treatments That Work™

Emotional Deprivation

Changing Avoidance (Behavioral Activation)

Understanding Depression

Negative Thoughts - Self-Monitoring Record

Behavioral Activation Activity Planning Diary

Core Belief Magnet Metaphor

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Emotional Inhibition

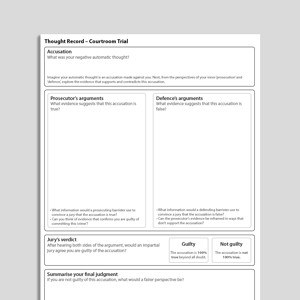

Thought Record – Courtroom Trial

Thought-Action Fusion

Thought Record (Considered Response)

Social Comparison

Defectiveness

Activity Planning

Emotional Reasoning

Activity Diary (Hourly Time Intervals)

"Should" Statements

Thoughts And Depression

Self Critical Thought Challenging Record

Approval-/Admiration-Seeking

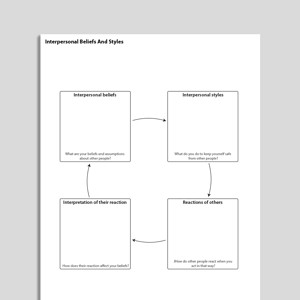

Interpersonal Beliefs And Styles

All-Or-Nothing Thinking

Self-Monitoring Record (Universal)

Boundaries - Self-Monitoring Record

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Intolerance Of Uncertainty And Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms (Hebert, Dugas, 2019)

Dependence / Incompetence

Overcoming Depression (Second Edition): Workbook

Entitlement

Uncertainty Beliefs – Experiment Record

Developing Psychological Flexibility

Catching Your Thoughts (CYP)

Demanding Standards – Living Well With Your Personal Rules

Discounting In Perfectionism – The Ratchet Effect

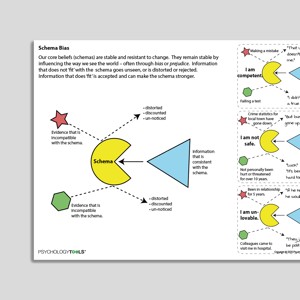

Schema Bias

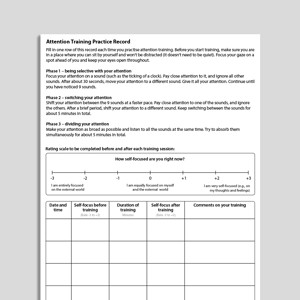

Attention Training Practice Record

A Guide To Emotions (Psychology Tools For Living Well)

Books & Chapters

Disqualifying The Positive

Intrusive Memory Record

What Is Imagery Rescripting?

Overcoming Depression (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Depression - Self-Monitoring Record

Rumination - Self-Monitoring Record

Being With Difficulty (Audio)

Hindsight Bias

What Is Burnout?

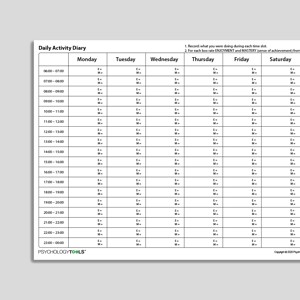

CBT Daily Activity Diary With Enjoyment And Mastery Ratings

Functional Analysis With Intervention Planning

Body Scan (Audio)

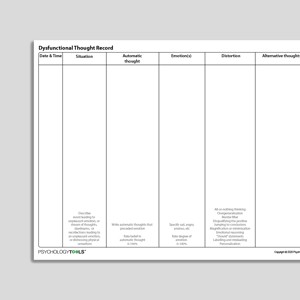

Dysfunctional Thought Record

Mind Reading

Mindfulness Of Breath (Short Version) (Audio)

Externalizing

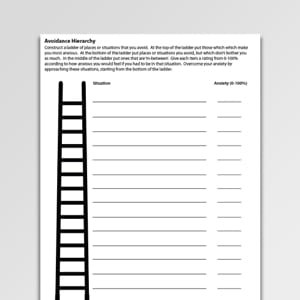

Avoidance Hierarchy (Archived)

Court Trial Thought Challenging Record (Archived)

What Do People Think About Themselves (CYP)?

Challenging Your Negative Thinking (Archived)

Mastery And Pleasure Activity Diary

Mental Filter

Fortune Telling

Magnification And Minimization

Personalizing

Exercise For Mental Health

Disqualifying Others

Links to external resources.

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

- Valued Living Questionnaire (Version 2) | Wilson, Groom | 2002 Download Archived Link

- Scale Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Scale Download Archived Link

- Zimmerman, M., Chelminski, I., McGlinchey, J. B., & Posternak, M. A. (2008). A clinically useful depression outcome scale. Comprehensive psychiatry, 49(2), 131-140.

- Reference Zung, W. W. (1965). A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 63-70.

- Scale – Adult Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Scale – Child Age 11-17 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Scale phqscreeners.com Download Primary Link

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric annals, 32(9), 509-515.

- MADRS Score Card Download Archived Link

- Montgomery, S.A., Asberg, M. (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. British Journal of Psychiatry, 134 (4): 382–89.

- Hamilton M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 23, 56–62.

- Scale Download Primary Link

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782-786.

Case Conceptualization / Case Formulation

- Developing and using a case formulation to guide cognitive behaviour therapy | Persons | 2015 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Cognitive conceptualisation (excerpt from Basics and Beyond) | J. Beck Download Archived Link

Guides and workbooks

- Mood And Substance Use | NDARC: Mills, Marel, Baker, Teesson, Dore, Kay-Lambkin, Manns, Trimingham | 2011 Download Primary Link

Information Handouts

- What Is Depression? Download Primary Link Archived Link

- What Causes Depression? Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Psychotherapy for Depression Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Vicious Cycle of Depression Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Behavioural Activation: Fun and Achievement Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Fun Activities Catalogue Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Improving How You Feel Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Thinking and Feeling Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Analysing Your Thinking Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Changing Your Negative Thinking Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Unhelpful Thinking Styles Download Primary Link Archived Link

- What Are Core Beliefs? Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Problem Solving Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Staying Healthy Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Grief and Bereavement Download Primary Link Archived Link

Information (Professional)

- Get out of the TRAP and back on TRAC (for rumination and worry) | GoodMedicine Download Primary Link Archived Link

Self-Help Programmes

- Introduction to BA for depression Download Archived Link

- Monitoring Activity And Mood Download Archived Link

- Roadmap: The Activation Plan Download Archived Link

- Finding Direction: Values, Flow, And Strengths Download Archived Link

- Avoidance And Depression TRAPs Download Archived Link

- Thinking Habits Download Archived Link

- Next Steps Download Archived Link

- Module 1: Overview of Depression Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 2: Behavioural Strategies for Managing Depression Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 3: The Thinking-Feeling Connection Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 4: The ABC Analysis Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 5: Unhelpful Thinking Styles Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 6: Detective Work and Disputation Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 7: The End Result Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 8: Core Beliefs Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 9: Self-Management Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 1: Overview Of Depression Download Primary Link

- Module 2: Behavioral Strategies For Managing Depression Download Primary Link

- Module 3: The Thinking-Feeling Connection Download Primary Link

- Module 4: The ABC Analysis Download Primary Link

- Module 5: Unhelpful Thinking Styles Download Primary Link

- Module 6: Detective Work And Disputation Download Primary Link

- Module 7: The End Result Download Primary Link

- Module 8: Core Beliefs Download Primary Link

- Module 9: Self Management Download Primary Link

Treatment Guide

- Depression In Adults: Treatment And Management (NICE Guideline) | NICE | 2022 Download Primary Link

- Behavioural activation treatment for depression (BATD) manual | Lejuez, Hopko & Hopko | 2001 Download Archived Link

- Suicide and self injury: a practitioners guide | Forensic Psychology Practice Ltd | 1999 Download Archived Link

- Behavioural activation treatment for depression – revised (BATD-R) manual | Lejuez, Hopko, Acierno, Daughters, Pagoto | 2011 Download Archived Link

- Metacognitive Training For Depression (D-MCT) Manual | Jelinek, Schneider, Hauschild, Moritz | 2023 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 1: Thinking and reasoning 1 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 2: Memory Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 3: Thinking and reasoning 2 Download Archived Link

- Module 4: Self-worth Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 5: Thinking and reasoning 3 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 6: Behaviors and strategies Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 7: Thinking and reasoning 4 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Module 8: Perception of feelings Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in young people: a modular treatment manual | Orygen | 2015 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Group therapy manual for cognitive behavioral treatment of depression | Muñoz, Miranda | 1993 Download Archived Link

- CBT For Depression In Veterans And Military Service Members – Therapist Manual | Wenzel, Brown, Carlin | 2011 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in young people: manual for therapists | Improving Mood with Psychoanalytic and Cognitive Therapies (IMPACT) Study CBT Sub-Group | 2010 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) Group Program For Depression | Milner, Tischler, DeSena, Rimer Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Manual for group cognitive-behavioral therapy of major depression: a reality management approach (Instructor’s manual) | Muñoz, Ippen, Rao, Le, Dwyer | 2000 Download Primary Link

- Individual therapy manual for cognitive-behavioural treatment of depression | Ricardo Muñoz, Jeanne Miranda | 1996 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Depression In Adults: Recognition And Management | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines | 2009 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Symptoms of Depression Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Behavioural Activation Download Primary Link Archived Link

- My Behavioural Antidepressants Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Weekly Activity Schedule Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Weekly Goals Record Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Making the Connection (Between Thoughts and Feelings) Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Thought Diary 1 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Thought Diary 2 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Thought Diary 3 Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Thought Diary (Tri-fold) Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Core Beliefs Worksheet Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Healthy Me Download Primary Link Archived Link

- Goal Setting (End of Therapy) Download Primary Link Archived Link

Recommended Reading

- Behavioural activation treatment for depression: returning to contextual roots | Jacobson, Martell, Dimidjian | 2001 Download Primary Link Archived Link

What Is Depression?

Signs and symptoms of depression.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder an individual must have experienced five of the following symptoms for at least two weeks:

- a depressed mood that is present most of the day, nearly every day

- diminished interest in activities which were previously experienced as pleasurable

- fatigue or a loss of energy

- sleep disturbance (insomnia or hypersomnia)

- feelings of worthlessness, self-reproach, or excessive guilt

- a diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, or suicidal behavior

- changes in appetite marked by a corresponding weight change

- psychomotor agitation or retardation to a degree which is observable by others

Psychological Models and Theory of Depression

Beck’s cognitive theory of depression (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) forms the basis for cognitive behavioral approaches for the treatment of depression. Beck’s theory proposes that there are different levels of cognition that can be dysfunctional in depression: core beliefs, rules and assumptions, and negative automatic thoughts. CBT aims to balance negatively biased cognition with more rational and accurate thoughts, beliefs, and assumptions. CBT also systematically aims to increase levels of rewarding activity.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) proposes that distress, including symptoms of depression, are the result of psychological inflexibility (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). Indicators of psychological inflexibility include:

- ‘buying in’ to negative thoughts and narratives;

- engaging in worry or rumination that takes us away from the present moment;

- losing contact with our values—what is important to us.

Evidence-Based Psychological Approaches for Working with Depression

Many psychological therapies have an evidence base for working with depression:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- Behavioral activation (BA)

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)

- Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for preventing relapse

- Interpersonal therapy (IPT)

Resources for Working with Depression

Psychology Tools resources available for working therapeutically with depression may include:

- psychological models of depression

- information handouts for depression

- exercises for depression

- CBT worksheets for depression

- self-help programs for depression

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression . New York: Guilford Press.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 44 (1), 1–25.

- For clinicians

- For students

- Resources at your fingertips

- Designed for effectiveness

- Resources by problem

- Translation Project

- Help center

- Try us for free

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychiatry

- v.62(Suppl 2); 2020 Jan

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression

Manaswi gautam.

Consultant Psychiatrist Gautam Hospital and Research Center, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Adarsh Tripathi

1 Department of Psychiatry, King George's Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

Deepanjali Deshmukh

2 MGM Medical College, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India

Manisha Gaur

3 Consultant Psychologist, Gaur Mental Health Clinic, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India

INTRODUCTION

Depressive disorders are one of the most common psychiatric disorders that occur in people of all ages across all world regions. Although it may present at any age however adolescence to early adults is the most common age of onset, and females are affected two times more in comparison to the males. Depressive disorders can occur as heterogeneous conditions in clinical scenario ranging from transient minor symptoms to severe and debilitating clinical conditions, causing severe social and occupational impairments. Usually, it presents with constellations of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, physiological, interpersonal, social, and occupational symptoms. The illness can be of various severities, and a significant proportion of the patients can have recurrent illness. Depression is also highly comorbid with several psychiatric and medical illnesses such as anxiety disorders, substance use, obsessive–compulsive disorder, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular illnesses.

Major depressive disorders accounted for around 8.2% global years lived with disability (YLD) in 2010, and it was the second leading cause of the YLDs. In addition, they also contribute to the burden of several other disorders indirectly such as suicide and ischemic heart disease.[ 1 ]

EVIDENCE BASE FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY IN DEPRESSION

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most evidence-based psychological interventions for the treatment of several psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorder, and substance use disorder. The uses are recently extended to psychotic disorders, behavioral medicine, marital discord, stressful life situations, and many other clinical conditions.

A sufficient number of researches have been conducted and shown the efficacy of CBT in depressive disorders. A meta-analysis of 115 studies has shown that CBT is an effective treatment strategy for depression and combined treatment with pharmacotherapy is significantly more effective than pharmacotherapy alone.[ 2 ] Evidence also suggests that relapse rate of patient treated with CBT is lower in comparison to the patients treated with pharmacotherapy alone.[ 3 ]

Treatment guidelines for the depression suggest that psychological interventions are effective and acceptable strategy for treatment. The psychological interventions are most commonly used for mild-to-moderate depressive episodes. As per the prevailing situations of India with regards to significant lesser availability of trained therapist in most of the places and patients preferences, the pharmacological interventions are offered as the first-line treatment modalities for treatment of depression.

Indication for Cognitive behavior therapy as enlisted in table 1 .

Indications for cognitive behavioral therapy (situations that can call for preferred use of the psychological interventions) are

| 1. Client’s preference |

| 2. Availability and accessibility of the trained therapist |

| 3. Special situations like children and adolescents, pregnancy, lactation, female in fertile age group planning for pregnancy, medical comorbidities, etc. |

| 4. Inability to tolerate psychopharmacological treatments |

| 5. The presence of significant psychosocial factors, intrapsychic conflicts, and interpersonal difficulties |

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

There is no absolute contraindication to CBT; however, it is often reported that clients with comorbid severe personality disorders such as antisocial personality disorders and subnormal intelligence are difficult to manage through CBT. Special training and expertise may be needed for the treatment of these clients.

Patient with severe depression with psychosis and/or suicidality might be difficult to manage with CBT alone and need medications and other treatment before considering CBT. Organicity should be ruled out using clinical evaluation and relevant investigations, as and when required.

There are many advantages of CBT in depression as given in table 2

Advantages of cognitive behavioral therapy in depression

| 1. It is used to reduce symptoms of depression as an independent treatment or in combination with medications |

| 2. It is used to modify the underlying schemas or beliefs that maintain the depression |

| 3. It can be used to address various psychosocial problems, for example, marital discord, job stress which can contribute to the symptoms |

| 4. Reduce the chances of recurrence |

| 5. Increase the adherence to recommended medical treatment |

CHOICE OF TREATMENT SETTINGS

CBT can be done on an Out Patient Department (OPD) basis with regular planned sessions. Each session lasts for about 45 min–1 h depending on the suitability for both patients and therapists. In specific situations, the CBT can be delivered in inpatient settings along with treatment as usual such as adjuvant treatment in severe depression, high risk for self-harm or suicidal patients, patients with multiple medical or psychiatric comorbidities and in patients hospitalized due to social reasons.

ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION FOR THE THERAPY

A detail diagnostic assessment is needed for the assessment of psychopathology, premorbid personality, diagnosis, severity, presence of suicidal ideations, and comorbidities. Baseline assessment of severity using a brief scale will be helpful in mutual understanding of severity before starting therapy and also to track the progress. Clients during depressive illness often fail to recognize early improvement and undermine any positive change. Objective rating scale hence helps in pointing out the progress and can also help in determining agenda during therapy process. Beck Depression Inventory (A. T. Beck, Steer, and Brown, 1996), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995), Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression are useful rating scales for this purpose. The assessment for CBT in depression is, however, different from diagnostic assessment.

THE USE OF COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY ACCORDING TO SEVERITY OF DEPRESSION

Various trials have shown the benefit of combined treatment for severe depression.

Combined therapy though costlier than monotherapy it provides cost-effectiveness in the form of relapse prevention.

Number of sessions depends on patient responsiveness.

Booster sessions might be required at the intervals of the 1–12 th month as per the clinical need.

A model for reference is given in table 3

The use of cognitive behavioral therapy according to the severity of depression

| Type of depression | First line | Adjunctive | Number of sessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | CBT or medication | CBT or medication | 8–12 |

| Moderate | CBT or medication | CBT or medication | 8–16 |

| Severe | Medication or/and Somatic treatment | CBT | 16 or more |

| Chronic depression and recurrent depression | CBT or medication | CBT or medication | 16 or more and booster sessions up to 1–2 years |

The general outline of CBT for depression has been discussed in table 4

Overview of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression

| 1. Mutually agreed on problem definition by therapist and client |

| 2. Goal settings |

| 3. Explaining and familiarizing client with five area model of CBT |

| 4. Improving awareness and understanding on one’s cognitive activity and behavior |

| 5. Modification of thoughts and behavior - using principles of Socratic dialogue, guided discovery, and behavioral experiments/exposure exercise |

| 6. Application and consolidation of new skills and strategies in therapy sessions and homework sessions to generalize it across situations |

| 7. Relapse prevention |

| 8. End of the therapy |

CBT – Cognitive behavioral therapy

COGNITIVE MODEL FOR DEPRESSION

Cognitive theory conceptualizes that people are not influenced by the events rather the view they take of the events. It essentially means that individual differences in the maladaptive thinking process and negative appraisal of the life events lead to the development of dysfunctional cognitive reactions. This cognitive dysfunction is in turn is responsible for the rest of the symptoms in affective and behavioral domains.

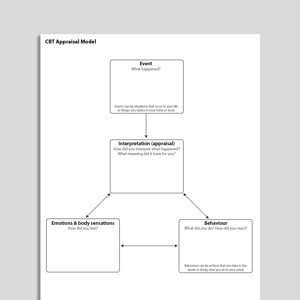

Aaron beck proposed a cognitive model of depression, and it is detailed in Figure 1 . Cognitive dysfunctions are of the following categories.

Cognitive behavioral therapy model of depression

- Schema - stable internal structure of information usually formed during early life, also include core belief about self

- information processing and intermediate belief are usually interpreted as rules of living and usually expressed in terms of “if and then” sentences

- Automatic thoughts - proximally related to everyday events and in depression, often reflects cognitive triad, i.e., negative view of oneself, world, and future.

Negative cognitive triad of depression as given beck is as following:

- I am helpless (helplessness)

- The future is bleak (hopelessness)

- I am worthless (worthlessness).

CHOICE OF THE PATIENT

Patient-related factors that facilitated response are.

- Psychological mindedness of patients: Patients who are able to understand and label their feelings and emotions generally respond better to CBT. Although some patients in the course of treatment learn those skills during treatment

- Intellectual level of the patient might also affect the overall effectiveness of the treatment

- Willingness and motivation on the part of patients: Although it is not prerequisite, patients who are motivated to analyze their feelings and ready to undergo various homework show a better response to treatment

- Patient preference is single most important factor: After initial assessment of the patient those who prefer psychological treatment can be offered CBT alone or in combination depending on type of depression

- Those with mild to moderate depression CBT can be recommended as a first line of treatment

- Patients with severe depression might need combination of both CBT and medications (and or other treatments)

- Special situations such as children and adolescents, pregnancy, lactation, female in fertile age group planning for pregnancy, medical comorbidities

- Inability to tolerate psychopharmacological treatment

- The presence of significant psychosocial factors, intrapsychic conflicts, and interpersonal difficulties.

Therapist related factors

- Availability of cognitive behavioral therapist/psychiatrist

- The ability of therapist to form therapeutic alliance with the patient.

CLINICAL INTERVIEW FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Symptoms and associated cognitions.

Negative automatic thoughts both trigger and enhance depression. It might be helpful to identify unhealthy automatic thoughts associated with symptoms of depression.

Some common symptoms and associated automatic thoughts are given in table 5 .

Symptoms of depression and associated cognitions

| Serial number | Symptoms | Automatic thoughts |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Behavioral: lower activity levels | I cants do it. It is too much for me |

| 2 | Guilt | I am letting everybody down |

| 3 | Shame | What everyone must be thinking about me |

Impact on functioning

it is important to know the extent and effect of depression on the overall functioning and interpersonal relationships.

Coping strategies

Sometimes patients with depression might have adapted a coping strategies which make them feel good for short duration (e.g., alcohol consumption) but might be unhealthy in long term.

Onset of current symptoms

Patient's perception about the situation at the onset of symptoms might provide useful information about underlying cognitive distortions.

Background information

Detailed history of patient is necessary, including patients premorbid personality.

The therapist should be able to do the cognitive case conceptualization for the patient as given in Figure 2 .

Case conceptualization for the cognitive model of depression

MANAGING TREATMENT

An outline of the breakup of typical session of CBT is given in table 6 .

Session structure of cognitive behavioral therapy

| Serial number | Component | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beginning of the session | |

| Mood check | 5–10 | |

| Agenda setting | ||

| Reviewing homework | ||

| 2 | Discussion of agenda items/problems | 35–40 |

| Description of occurrence of specific problem | ||

| Elicitation and confirmation of elements of the cognitive model | ||

| Collaborative discussion regarding how to approach a problem | ||

| Rationale for the introduction of intervention | ||

| Assessment of the efficacy of intervention | ||

| Summary by patient | ||

| Collaborative action plan in writing | ||

| Planning and discussing a homework and how to approach it | ||

| 3 | Feedback to the therapist | 1–2 |

Starting treatment

First treatment interview has mainly four objectives:

- To establish a warm collaborative therapeutic alliance

- To list specific problem set and associated goals

- To psycho-educate patient regarding the cognitive model and vicious cycle that maintains the depression

- Give the patient idea about further treatment procedures.

CBT can be explained in the following headings

- Behavioral interventions

Working with negative automatic thoughts

- Ending session.

The first treatment interview has four main objectives:

- To establish a warm, collaborative therapeutic alliance

- To list specific problems and associated goals, and select a first problem to tackle

- To educate the patient about the cognitive model, especially the vicious circle that maintains depression

- To give the patient first-hand experience of the focused, workman-like, empirical style of CBT.

These convey two important messages: (1) It is possible to make sense of depression; (2) there is something the patient can do about it. These messages directly address hopelessness and helplessness.

- Identifying problems and goals:-The various problems faced by patients should be included in a list which can include symptoms of depression or social problems (e.g., family conflict). Developing this list at the end of the first session helps in planning treatment goals

- Introducing cognitive model of depression:- In the first session at least a basic idea about how our cognitions affect our emotions and behavior is taught to the patient. The data provided by patient can be used to give insight into behaviors

- Where to start:-Common treatment goal is agreed upon by patient and therapist, therapeutic alliance is of key importance in CBT. Appropriate homework assignment should be given to patient according to predecided goal.

Behavioural interventions

Reducing ruminations.

It has been seen that depressed patients spend a significant amount of time and attention focusing on their shortcomings. Making patient aware of those negative ruminations and consciously diverting attention toward certain positive aspects can be taught to patients.

Monitoring activities

Loss of interest in day to day activities is central to the depression. It has been seen that early behavioral intervention has been increased sense of autonomy in the patients.

Patients are taught to record each and every activity hour by hour on the activity schedule. Each activity is rated 0–10 for Pleasure (P) and Mastery (M). P ratings indicate how enjoyable the activity was, and M ratings how much of an achievement it was. Mostly depressed patients feel low on achievement all the time. Hence, M should be explained as “achievement how you felt at the time of doing.” Patients are instructed to rate activities immediately and not retrospectively.

Example of activity schedule is

Activity Chart Write in each box, activity performed and depression rating from 0-100% (0-minimal, 100-maximum)

| 6-7 AM | |||||||

| 7-8 AM | |||||||

| 8-9 AM* | Breakfast, talk with wife, 40% | Breakfast alone, 60% | Walk, 30% | Breakfast with son, 50% | Talk with friend on phone, 20% | Breakfast alone, 60% | Breakfast with everyone in family, 20% |

| 10-11 PM | Hourly rating from waking up till time to sleep | What everyone must be thinking about me |

Planning activities

Once the patient learns to self-monitor activities each day is planned in advance.

This helps patients by:

- This provides a structure and helps with setting priorities

- This avoids the need to keep making decisions about what to do next

- This changes perception from chaos to manageable tasks

- This increases the chances that activities will be carried out

- This enhances patients’ sense of control.

A plan for activities is made in such a way that both pleasure and mastery are balanced (e.g., ironing cloths followed by listening to music). The tasks which are generally avoided by patient can be divided into graded tasks.

The patient is taught to evaluate each and every day in detail also encouraged to keep the record of unhelpful negative thoughts regarding tasks.

Other important behavioral activities are:-

- Mindfulness meditation: Helps people stay grounded in the present by keeping away from ruminations

- Successive approximation: Breaking larger tasks into smaller tasks which are easy to accomplish

- Visualizing the best part of the day

- Pleasant activity scheduling.

Scheduling an activity in near future which one can look on with mastery and with sense of achievement.

The main tool for this negative automatic thought record.

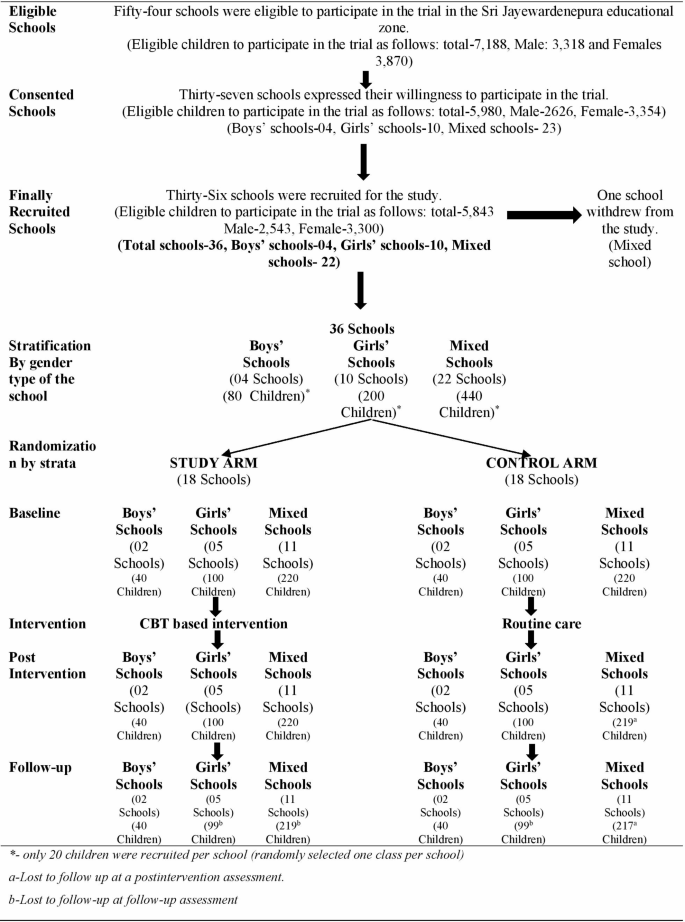

Thought Record -1