- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Lilly Music

- Webster Veterinary

- Hirsh Health Sciences Library

Finding and Creating Surveys/Questionnaires

- Published Questionnaires

- Finding Info about Tests

Look for a Test

- PsycTESTS Provides access to abstracts and some full-text of psychological tests, measures, scales, surveys, and other assessments as well as descriptive information about the test and its development and administration. Most records include the actual instrument.

Searching for Surveys/Questionnaires

Some questionnaires or surveys are published within an article. To find them, conduct an article search in a bibliographic database on the topic of interest and add in the Keywords: survey* or questionnaire*

In some cases the actual questionnaire or survey is not published with the article, but referred to within the text. In this case look at the bibliography and find the reference to the questionnaire/survey itself, or to the original article where the instrument was published. From that information track down the instrument.

Some instruments are not free. They can be purchased from the developer.

Tips for searching for an already established survey or questionnaire. Be sure to read the definition if there is one and also look to see if there is a broader or narrower concept that might be more specific to your needs.

- In Ovid MEDLINE or PubMed using MeSH terminology

- Use the subheading for Statistics and Numerical Data (sn) with your topic

- In conjunction with your topic use the term AND to combine the topic with any of the terms below.

- There is a broader term Data Collection or a narrower term Self Report , if those are more appropriate.

- There are more discipline specific subject headings or MeSH, such as the ones below. Be sure to read the definitions of these terms to make sure they are correct for what you want to find.

- Health Surveys

- Dental Health Surveys

- Health Status Indicators

- Nutrition Surveys

- Diet Surveys

- Health Care Surveys

- Nutrition Assessment

- Questionnaires

- In PsycInfo, these terms might be helpful:

- Attitude Measures

- Opinion Survey

- General Health Questionnaires

- Mail Surveys

- Consumer Surveys

- Telephone Surveys

- Test Construction

- In Sociological Abstracts

- Attitudes

- In ERIC (education research)

- Evaluation Methods

- << Previous: Surveys

- Next: Finding Info about Tests >>

Desk Hours: M-F 7:45am-5pm

- Last Updated: Nov 22, 2023 10:58 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/surveys

- Privacy Policy

Home » Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Table of Contents

Questionnaire

Definition:

A Questionnaire is a research tool or survey instrument that consists of a set of questions or prompts designed to gather information from individuals or groups of people.

It is a standardized way of collecting data from a large number of people by asking them a series of questions related to a specific topic or research objective. The questions may be open-ended or closed-ended, and the responses can be quantitative or qualitative. Questionnaires are widely used in research, marketing, social sciences, healthcare, and many other fields to collect data and insights from a target population.

History of Questionnaire

The history of questionnaires can be traced back to the ancient Greeks, who used questionnaires as a means of assessing public opinion. However, the modern history of questionnaires began in the late 19th century with the rise of social surveys.

The first social survey was conducted in the United States in 1874 by Francis A. Walker, who used a questionnaire to collect data on labor conditions. In the early 20th century, questionnaires became a popular tool for conducting social research, particularly in the fields of sociology and psychology.

One of the most influential figures in the development of the questionnaire was the psychologist Raymond Cattell, who in the 1940s and 1950s developed the personality questionnaire, a standardized instrument for measuring personality traits. Cattell’s work helped establish the questionnaire as a key tool in personality research.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the use of questionnaires expanded into other fields, including market research, public opinion polling, and health surveys. With the rise of computer technology, questionnaires became easier and more cost-effective to administer, leading to their widespread use in research and business settings.

Today, questionnaires are used in a wide range of settings, including academic research, business, healthcare, and government. They continue to evolve as a research tool, with advances in computer technology and data analysis techniques making it easier to collect and analyze data from large numbers of participants.

Types of Questionnaire

Types of Questionnaires are as follows:

Structured Questionnaire

This type of questionnaire has a fixed format with predetermined questions that the respondent must answer. The questions are usually closed-ended, which means that the respondent must select a response from a list of options.

Unstructured Questionnaire

An unstructured questionnaire does not have a fixed format or predetermined questions. Instead, the interviewer or researcher can ask open-ended questions to the respondent and let them provide their own answers.

Open-ended Questionnaire

An open-ended questionnaire allows the respondent to answer the question in their own words, without any pre-determined response options. The questions usually start with phrases like “how,” “why,” or “what,” and encourage the respondent to provide more detailed and personalized answers.

Close-ended Questionnaire

In a closed-ended questionnaire, the respondent is given a set of predetermined response options to choose from. This type of questionnaire is easier to analyze and summarize, but may not provide as much insight into the respondent’s opinions or attitudes.

Mixed Questionnaire

A mixed questionnaire is a combination of open-ended and closed-ended questions. This type of questionnaire allows for more flexibility in terms of the questions that can be asked, and can provide both quantitative and qualitative data.

Pictorial Questionnaire:

In a pictorial questionnaire, instead of using words to ask questions, the questions are presented in the form of pictures, diagrams or images. This can be particularly useful for respondents who have low literacy skills, or for situations where language barriers exist. Pictorial questionnaires can also be useful in cross-cultural research where respondents may come from different language backgrounds.

Types of Questions in Questionnaire

The types of Questions in Questionnaire are as follows:

Multiple Choice Questions

These questions have several options for participants to choose from. They are useful for getting quantitative data and can be used to collect demographic information.

- a. Red b . Blue c. Green d . Yellow

Rating Scale Questions

These questions ask participants to rate something on a scale (e.g. from 1 to 10). They are useful for measuring attitudes and opinions.

- On a scale of 1 to 10, how likely are you to recommend this product to a friend?

Open-Ended Questions

These questions allow participants to answer in their own words and provide more in-depth and detailed responses. They are useful for getting qualitative data.

- What do you think are the biggest challenges facing your community?

Likert Scale Questions

These questions ask participants to rate how much they agree or disagree with a statement. They are useful for measuring attitudes and opinions.

How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statement:

“I enjoy exercising regularly.”

- a . Strongly Agree

- c . Neither Agree nor Disagree

- d . Disagree

- e . Strongly Disagree

Demographic Questions

These questions ask about the participant’s personal information such as age, gender, ethnicity, education level, etc. They are useful for segmenting the data and analyzing results by demographic groups.

- What is your age?

Yes/No Questions

These questions only have two options: Yes or No. They are useful for getting simple, straightforward answers to a specific question.

Have you ever traveled outside of your home country?

Ranking Questions

These questions ask participants to rank several items in order of preference or importance. They are useful for measuring priorities or preferences.

Please rank the following factors in order of importance when choosing a restaurant:

- a. Quality of Food

- c. Ambiance

- d. Location

Matrix Questions

These questions present a matrix or grid of options that participants can choose from. They are useful for getting data on multiple variables at once.

| The product is easy to use | ||||

| The product meets my needs | ||||

| The product is affordable |

Dichotomous Questions

These questions present two options that are opposite or contradictory. They are useful for measuring binary or polarized attitudes.

Do you support the death penalty?

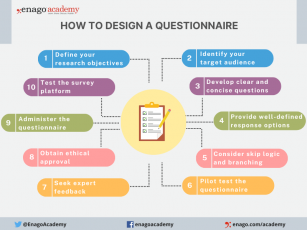

How to Make a Questionnaire

Step-by-Step Guide for Making a Questionnaire:

- Define your research objectives: Before you start creating questions, you need to define the purpose of your questionnaire and what you hope to achieve from the data you collect.

- Choose the appropriate question types: Based on your research objectives, choose the appropriate question types to collect the data you need. Refer to the types of questions mentioned earlier for guidance.

- Develop questions: Develop clear and concise questions that are easy for participants to understand. Avoid leading or biased questions that might influence the responses.

- Organize questions: Organize questions in a logical and coherent order, starting with demographic questions followed by general questions, and ending with specific or sensitive questions.

- Pilot the questionnaire : Test your questionnaire on a small group of participants to identify any flaws or issues with the questions or the format.

- Refine the questionnaire : Based on feedback from the pilot, refine and revise the questionnaire as necessary to ensure that it is valid and reliable.

- Distribute the questionnaire: Distribute the questionnaire to your target audience using a method that is appropriate for your research objectives, such as online surveys, email, or paper surveys.

- Collect and analyze data: Collect the completed questionnaires and analyze the data using appropriate statistical methods. Draw conclusions from the data and use them to inform decision-making or further research.

- Report findings: Present your findings in a clear and concise report, including a summary of the research objectives, methodology, key findings, and recommendations.

Questionnaire Administration Modes

There are several modes of questionnaire administration. The choice of mode depends on the research objectives, sample size, and available resources. Some common modes of administration include:

- Self-administered paper questionnaires: Participants complete the questionnaire on paper, either in person or by mail. This mode is relatively low cost and easy to administer, but it may result in lower response rates and greater potential for errors in data entry.

- Online questionnaires: Participants complete the questionnaire on a website or through email. This mode is convenient for both researchers and participants, as it allows for fast and easy data collection. However, it may be subject to issues such as low response rates, lack of internet access, and potential for fraudulent responses.

- Telephone surveys: Trained interviewers administer the questionnaire over the phone. This mode allows for a large sample size and can result in higher response rates, but it is also more expensive and time-consuming than other modes.

- Face-to-face interviews : Trained interviewers administer the questionnaire in person. This mode allows for a high degree of control over the survey environment and can result in higher response rates, but it is also more expensive and time-consuming than other modes.

- Mixed-mode surveys: Researchers use a combination of two or more modes to administer the questionnaire, such as using online questionnaires for initial screening and following up with telephone interviews for more detailed information. This mode can help overcome some of the limitations of individual modes, but it requires careful planning and coordination.

Example of Questionnaire

Title of the Survey: Customer Satisfaction Survey

Introduction:

We appreciate your business and would like to ensure that we are meeting your needs. Please take a few minutes to complete this survey so that we can better understand your experience with our products and services. Your feedback is important to us and will help us improve our offerings.

Instructions:

Please read each question carefully and select the response that best reflects your experience. If you have any additional comments or suggestions, please feel free to include them in the space provided at the end of the survey.

1. How satisfied are you with our product quality?

- Very satisfied

- Somewhat satisfied

- Somewhat dissatisfied

- Very dissatisfied

2. How satisfied are you with our customer service?

3. How satisfied are you with the price of our products?

4. How likely are you to recommend our products to others?

- Very likely

- Somewhat likely

- Somewhat unlikely

- Very unlikely

5. How easy was it to find the information you were looking for on our website?

- Somewhat easy

- Somewhat difficult

- Very difficult

6. How satisfied are you with the overall experience of using our products and services?

7. Is there anything that you would like to see us improve upon or change in the future?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Conclusion:

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. Your feedback is valuable to us and will help us improve our products and services. If you have any further comments or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Applications of Questionnaire

Some common applications of questionnaires include:

- Research : Questionnaires are commonly used in research to gather information from participants about their attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and experiences. This information can then be analyzed and used to draw conclusions and make inferences.

- Healthcare : In healthcare, questionnaires can be used to gather information about patients’ medical history, symptoms, and lifestyle habits. This information can help healthcare professionals diagnose and treat medical conditions more effectively.

- Marketing : Questionnaires are commonly used in marketing to gather information about consumers’ preferences, buying habits, and opinions on products and services. This information can help businesses develop and market products more effectively.

- Human Resources: Questionnaires are used in human resources to gather information from job applicants, employees, and managers about job satisfaction, performance, and workplace culture. This information can help organizations improve their hiring practices, employee retention, and organizational culture.

- Education : Questionnaires are used in education to gather information from students, teachers, and parents about their perceptions of the educational experience. This information can help educators identify areas for improvement and develop more effective teaching strategies.

Purpose of Questionnaire

Some common purposes of questionnaires include:

- To collect information on attitudes, opinions, and beliefs: Questionnaires can be used to gather information on people’s attitudes, opinions, and beliefs on a particular topic. For example, a questionnaire can be used to gather information on people’s opinions about a particular political issue.

- To collect demographic information: Questionnaires can be used to collect demographic information such as age, gender, income, education level, and occupation. This information can be used to analyze trends and patterns in the data.

- To measure behaviors or experiences: Questionnaires can be used to gather information on behaviors or experiences such as health-related behaviors or experiences, job satisfaction, or customer satisfaction.

- To evaluate programs or interventions: Questionnaires can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions by gathering information on participants’ experiences, opinions, and behaviors.

- To gather information for research: Questionnaires can be used to gather data for research purposes on a variety of topics.

When to use Questionnaire

Here are some situations when questionnaires might be used:

- When you want to collect data from a large number of people: Questionnaires are useful when you want to collect data from a large number of people. They can be distributed to a wide audience and can be completed at the respondent’s convenience.

- When you want to collect data on specific topics: Questionnaires are useful when you want to collect data on specific topics or research questions. They can be designed to ask specific questions and can be used to gather quantitative data that can be analyzed statistically.

- When you want to compare responses across groups: Questionnaires are useful when you want to compare responses across different groups of people. For example, you might want to compare responses from men and women, or from people of different ages or educational backgrounds.

- When you want to collect data anonymously: Questionnaires can be useful when you want to collect data anonymously. Respondents can complete the questionnaire without fear of judgment or repercussions, which can lead to more honest and accurate responses.

- When you want to save time and resources: Questionnaires can be more efficient and cost-effective than other methods of data collection such as interviews or focus groups. They can be completed quickly and easily, and can be analyzed using software to save time and resources.

Characteristics of Questionnaire

Here are some of the characteristics of questionnaires:

- Standardization : Questionnaires are standardized tools that ask the same questions in the same order to all respondents. This ensures that all respondents are answering the same questions and that the responses can be compared and analyzed.

- Objectivity : Questionnaires are designed to be objective, meaning that they do not contain leading questions or bias that could influence the respondent’s answers.

- Predefined responses: Questionnaires typically provide predefined response options for the respondents to choose from, which helps to standardize the responses and make them easier to analyze.

- Quantitative data: Questionnaires are designed to collect quantitative data, meaning that they provide numerical or categorical data that can be analyzed using statistical methods.

- Convenience : Questionnaires are convenient for both the researcher and the respondents. They can be distributed and completed at the respondent’s convenience and can be easily administered to a large number of people.

- Anonymity : Questionnaires can be anonymous, which can encourage respondents to answer more honestly and provide more accurate data.

- Reliability : Questionnaires are designed to be reliable, meaning that they produce consistent results when administered multiple times to the same group of people.

- Validity : Questionnaires are designed to be valid, meaning that they measure what they are intended to measure and are not influenced by other factors.

Advantage of Questionnaire

Some Advantage of Questionnaire are as follows:

- Standardization: Questionnaires allow researchers to ask the same questions to all participants in a standardized manner. This helps ensure consistency in the data collected and eliminates potential bias that might arise if questions were asked differently to different participants.

- Efficiency: Questionnaires can be administered to a large number of people at once, making them an efficient way to collect data from a large sample.

- Anonymity: Participants can remain anonymous when completing a questionnaire, which may make them more likely to answer honestly and openly.

- Cost-effective: Questionnaires can be relatively inexpensive to administer compared to other research methods, such as interviews or focus groups.

- Objectivity: Because questionnaires are typically designed to collect quantitative data, they can be analyzed objectively without the influence of the researcher’s subjective interpretation.

- Flexibility: Questionnaires can be adapted to a wide range of research questions and can be used in various settings, including online surveys, mail surveys, or in-person interviews.

Limitations of Questionnaire

Limitations of Questionnaire are as follows:

- Limited depth: Questionnaires are typically designed to collect quantitative data, which may not provide a complete understanding of the topic being studied. Questionnaires may miss important details and nuances that could be captured through other research methods, such as interviews or observations.

- R esponse bias: Participants may not always answer questions truthfully or accurately, either because they do not remember or because they want to present themselves in a particular way. This can lead to response bias, which can affect the validity and reliability of the data collected.

- Limited flexibility: While questionnaires can be adapted to a wide range of research questions, they may not be suitable for all types of research. For example, they may not be appropriate for studying complex phenomena or for exploring participants’ experiences and perceptions in-depth.

- Limited context: Questionnaires typically do not provide a rich contextual understanding of the topic being studied. They may not capture the broader social, cultural, or historical factors that may influence participants’ responses.

- Limited control : Researchers may not have control over how participants complete the questionnaire, which can lead to variations in response quality or consistency.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Questionnaire Method In Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A questionnaire is a research instrument consisting of a series of questions for the purpose of gathering information from respondents. Questionnaires can be thought of as a kind of written interview . They can be carried out face to face, by telephone, computer, or post.

Questionnaires provide a relatively cheap, quick, and efficient way of obtaining large amounts of information from a large sample of people.

Data can be collected relatively quickly because the researcher would not need to be present when completing the questionnaires. This is useful for large populations when interviews would be impractical.

However, a problem with questionnaires is that respondents may lie due to social desirability. Most people want to present a positive image of themselves, and may lie or bend the truth to look good, e.g., pupils exaggerate revision duration.

Questionnaires can effectively measure relatively large subjects’ behavior, attitudes, preferences, opinions, and intentions more cheaply and quickly than other methods.

Often, a questionnaire uses both open and closed questions to collect data. This is beneficial as it means both quantitative and qualitative data can be obtained.

Closed Questions

A closed-ended question requires a specific, limited response, often “yes” or “no” or a choice that fit into pre-decided categories.

Data that can be placed into a category is called nominal data. The category can be restricted to as few as two options, i.e., dichotomous (e.g., “yes” or “no,” “male” or “female”), or include quite complex lists of alternatives from which the respondent can choose (e.g., polytomous).

Closed questions can also provide ordinal data (which can be ranked). This often involves using a continuous rating scale to measure the strength of attitudes or emotions.

For example, strongly agree / agree / neutral / disagree / strongly disagree / unable to answer.

Closed questions have been used to research type A personality (e.g., Friedman & Rosenman, 1974) and also to assess life events that may cause stress (Holmes & Rahe, 1967) and attachment (Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000).

- They can be economical. This means they can provide large amounts of research data for relatively low costs. Therefore, a large sample size can be obtained, which should represent the population from which a researcher can then generalize.

- The respondent provides information that can be easily converted into quantitative data (e.g., count the number of “yes” or “no” answers), allowing statistical analysis of the responses.

- The questions are standardized. All respondents are asked exactly the same questions in the same order. This means a questionnaire can be replicated easily to check for reliability . Therefore, a second researcher can use the questionnaire to confirm consistent results.

Limitations

- They lack detail. Because the responses are fixed, there is less scope for respondents to supply answers that reflect their true feelings on a topic.

Open Questions

Open questions allow for expansive, varied answers without preset options or limitations.

Open questions allow people to express what they think in their own words. Open-ended questions enable the respondent to answer in as much detail as they like in their own words. For example: “can you tell me how happy you feel right now?”

Open questions will work better if you want to gather more in-depth answers from your respondents. These give no pre-set answer options and instead, allow the respondents to put down exactly what they like in their own words.

Open questions are often used for complex questions that cannot be answered in a few simple categories but require more detail and discussion.

Lawrence Kohlberg presented his participants with moral dilemmas. One of the most famous concerns a character called Heinz, who is faced with the choice between watching his wife die of cancer or stealing the only drug that could help her.

Participants were asked whether Heinz should steal the drug or not and, more importantly, for their reasons why upholding or breaking the law is right.

- Rich qualitative data is obtained as open questions allow respondents to elaborate on their answers. This means the research can determine why a person holds a certain attitude .

- Time-consuming to collect the data. It takes longer for the respondent to complete open questions. This is a problem as a smaller sample size may be obtained.

- Time-consuming to analyze the data. It takes longer for the researcher to analyze qualitative data as they have to read the answers and try to put them into categories by coding, which is often subjective and difficult. However, Smith (1992) has devoted an entire book to the issues of thematic content analysis that includes 14 different scoring systems for open-ended questions.

- Not suitable for less educated respondents as open questions require superior writing skills and a better ability to express one’s feelings verbally.

Questionnaire Design

With some questionnaires suffering from a response rate as low as 5%, a questionnaire must be well designed.

There are several important factors in questionnaire design.

Pilot Study

Question order.

Questions should progress logically from the least sensitive to the most sensitive, from the factual and behavioral to the cognitive, and from the more general to the more specific.

The researcher should ensure that previous questions do not influence the answer to a question.

Question order effects

- Question order effects occur when responses to an earlier question affect responses to a later question in a survey. They can arise at different stages of the survey response process – interpretation, information retrieval, judgment/estimation, and reporting.

- Types of question order effects include: unconditional (subsequent answers affected by prior question topic), conditional (subsequent answers depend on the response to the prior question), and associational (correlation between two questions changes based on order).

- Question order effects have been found across different survey topics like social and political attitudes, health and safety studies, vignette research, etc. Effects may be moderated by respondent factors like age, education level, knowledge and attitudes about the topic.

- To minimize question order effects, recommendations include avoiding judgmental dependencies between questions, separating potentially reactive questions, randomizing questions, following good survey design principles, considering respondent characteristics, and intentionally examining question context and order.

Terminology

- There should be a minimum of technical jargon. Questions should be simple, to the point, and easy to understand. The language of a questionnaire should be appropriate to the vocabulary of the group of people being studied.

- Use statements that are interpreted in the same way by members of different subpopulations of the population of interest.

- For example, the researcher must change the language of questions to match the social background of the respondent’s age / educational level / social class/ethnicity, etc.

Presentation

Ethical issues.

- The researcher must ensure that the information provided by the respondent is kept confidential, e.g., name, address, etc.

- This means questionnaires are good for researching sensitive topics as respondents will be more honest when they cannot be identified.

- Keeping the questionnaire confidential should also reduce the likelihood of psychological harm, such as embarrassment.

- Participants must provide informed consent before completing the questionnaire and must be aware that they have the right to withdraw their information at any time during the survey/ study.

Problems with Postal Questionnaires

At first sight, the postal questionnaire seems to offer the opportunity to get around the problem of interview bias by reducing the personal involvement of the researcher. Its other practical advantages are that it is cheaper than face-to-face interviews and can quickly contact many respondents scattered over a wide area.

However, these advantages must be weighed against the practical problems of conducting research by post. A lack of involvement by the researcher means there is little control over the information-gathering process.

The data might not be valid (i.e., truthful) as we can never be sure that the questionnaire was completed by the person to whom it was addressed.

That, of course, assumes there is a reply in the first place, and one of the most intractable problems of mailed questionnaires is a low response rate. This diminishes the reliability of the data

Also, postal questionnaires may not represent the population they are studying. This may be because:

- Some questionnaires may be lost in the post, reducing the sample size.

- The questionnaire may be completed by someone not a member of the research population.

- Those with strong views on the questionnaire’s subject are more likely to complete it than those without interest.

Benefits of a Pilot Study

A pilot study is a practice / small-scale study conducted before the main study.

It allows the researcher to try out the study with a few participants so that adjustments can be made before the main study, saving time and money.

It is important to conduct a questionnaire pilot study for the following reasons:

- Check that respondents understand the terminology used in the questionnaire.

- Check that emotive questions are not used, as they make people defensive and could invalidate their answers.

- Check that leading questions have not been used as they could bias the respondent’s answer.

- Ensure the questionnaire can be completed in an appropriate time frame (i.e., it’s not too long).

Frequently Asked Questions

How do psychological researchers analyze the data collected from questionnaires.

Psychological researchers analyze questionnaire data by looking for patterns and trends in people’s responses. They use numbers and charts to summarize the information.

They calculate things like averages and percentages to see what most people think or feel. They also compare different groups to see if there are any differences between them.

By doing these analyses, researchers can understand how people think, feel, and behave. This helps them make conclusions and learn more about how our minds work.

Are questionnaires effective in gathering accurate data?

Yes, questionnaires can be effective in gathering accurate data. When designed well, with clear and understandable questions, they allow individuals to express their thoughts, opinions, and experiences.

However, the accuracy of the data depends on factors such as the honesty and accuracy of respondents’ answers, their understanding of the questions, and their willingness to provide accurate information. Researchers strive to create reliable and valid questionnaires to minimize biases and errors.

It’s important to remember that while questionnaires can provide valuable insights, they are just one tool among many used in psychological research.

Can questionnaires be used with diverse populations and cultural contexts?

Yes, questionnaires can be used with diverse populations and cultural contexts. Researchers take special care to ensure that questionnaires are culturally sensitive and appropriate for different groups.

This means adapting the language, examples, and concepts to match the cultural context. By doing so, questionnaires can capture the unique perspectives and experiences of individuals from various backgrounds.

This helps researchers gain a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior and ensures that everyone’s voice is heard and represented in psychological research.

Are questionnaires the only method used in psychological research?

No, questionnaires are not the only method used in psychological research. Psychologists use a variety of research methods, including interviews, observations , experiments , and psychological tests.

Each method has its strengths and limitations, and researchers choose the most appropriate method based on their research question and goals.

Questionnaires are valuable for gathering self-report data, but other methods allow researchers to directly observe behavior, study interactions, or manipulate variables to test hypotheses.

By using multiple methods, psychologists can gain a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

What is a semantic differential scale?

The semantic differential scale is a questionnaire format used to gather data on individuals’ attitudes or perceptions. It’s commonly incorporated into larger surveys or questionnaires to assess subjective qualities or feelings about a specific topic, product, or concept by quantifying them on a scale between two bipolar adjectives.

It presents respondents with a pair of opposite adjectives (e.g., “happy” vs. “sad”) and asks them to mark their position on a scale between them, capturing the intensity of their feelings about a particular subject.

It quantifies subjective qualities, turning them into data that can be statistically analyzed.

Ayidiya, S. A., & McClendon, M. J. (1990). Response effects in mail surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 54 (2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1086/269200

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350-365.

Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R. H. (1974). Type A behavior and your heart . New York: Knopf.

Gold, R. S., & Barclay, A. (2006). Order of question presentation and correlation between judgments of comparative and own risk. Psychological Reports, 99 (3), 794–798. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.99.3.794-798

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of psychosomatic research, 11(2) , 213-218.

Schwarz, N., & Hippler, H.-J. (1995). Subsequent questions may influence answers to preceding questions in mail surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 59 (1), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1086/269460

Smith, C. P. (Ed.). (1992). Motivation and personality: Handbook of thematic content analysis . Cambridge University Press.

Further Information

- Questionnaire design and scale development

- Questionnaire Appraisal Form

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.328(7451); 2004 May 29

Hands-on guide to questionnaire research

Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire, petra m boynton.

1 Department of Primary Care and Population Sciences, University College London, Archway Campus, London N19 5LW

Trisha Greenhalgh

Associated data, short abstract.

Anybody can write down a list of questions and photocopy it, but producing worthwhile and generalisable data from questionnaires needs careful planning and imaginative design

The great popularity with questionnaires is they provide a “quick fix” for research methodology. No single method has been so abused. 1

Questionnaires offer an objective means of collecting information about people's knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviour. 2 , 3 Do our patients like our opening hours? What do teenagers think of a local antidrugs campaign and has it changed their attitudes? Why don't doctors use computers to their maximum potential? Questionnaires can be used as the sole research instrument (such as in a cross sectional survey) or within clinical trials or epidemiological studies.

Randomised trials are subject to strict reporting criteria, 4 but there is no comparable framework for questionnaire research. Hence, despite a wealth of detailed guidance in the specialist literature, 1 - 3 , 5 w1-w8 elementary methodological errors are common. 1 Inappropriate instruments and lack of rigour inevitably lead to poor quality data, misleading conclusions, and woolly recommendations. w8 In this series we aim to present a practical guide that will enable research teams to do questionnaire research that is well designed, well managed, and non-discriminatory and which contributes to a generalisable evidence base. We start with selecting and designing the questionnaire. questionnaire.

What information are you trying to collect?

You and your co-researchers may have different assumptions about precisely what information you would like your study to generate. A formal scoping exercise will ensure that you clarify goals and if necessary reach an agreed compromise. It will also flag up potential practical problems—for example, how long the questionnaire will be and how it might be administered.

As a rule of thumb, if you are not familiar enough with the research area or with a particular population subgroup to predict the range of possible responses, and especially if such details are not available in the literature, you should first use a qualitative approach (such as focus groups) to explore the territory and map key areas for further study. 6

Is a questionnaire appropriate?

People often decide to use a questionnaire for research questions that need a different method. Sometimes, a questionnaire will be appropriate only if used within a mixed methodology study—for example, to extend and quantify the findings of an initial exploratory phase. Table A on bmj.com gives some real examples where questionnaires were used inappropriately. 1

Box 1: Pitfalls of designing your own questionnaire

Natasha, a practice nurse, learns that staff at a local police station have a high incidence of health problems, which she believes are related to stress at work. She wants to test the relation between stress and health in these staff to inform the design of advice services. Natasha designs her own questionnaire. Had she completed a thorough literature search for validated measures, she would have found several high quality questionnaires that measure stress in public sector workers. 8 Natasha's hard work produces only a second rate study that she is unable to get published.

Research participants must be able to give meaningful answers (with help from a professional interviewer if necessary). Particular physical, mental, social, and linguistic needs are covered in the third article of this series. 7

Could you use an existing instrument?

Using a previously validated and published questionnaire will save you time and resources; you will be able to compare your own findings with those from other studies, you need only give outline details of the instrument when you write up your work, and you may find it easier to get published (box 1).

Increasingly, health services research uses standard questionnaires designed for producing data that can be compared across studies. For example, clinical trials routinely include measures of patients' knowledge about a disease, 9 satisfaction with services, 10 or health related quality of life. 11 - 13 w3 w9 The validity (see below) of this approach depends on whether the type and range of closed responses reflects the full range of perceptions and feelings that people in all the different potential sampling frames might hold. Importantly, health status and quality of life instruments lose their validity when used beyond the context in which they were developed. 12 , 14 , 15 w3 w10-12

If there is no “off the peg” questionnaire available, you will have to construct your own. Using one or more standard instruments alongside a short bespoke questionnaire could save you the need to develop and validate a long list of new items.

Is the questionnaire valid and reliable?

A valid questionnaire measures what it claims to measure. In reality, many fail to do this. For example, a self completion questionnaire that seeks to measure people's food intake may be invalid because it measures what they say they have eaten, not what they have actually eaten. 16 Similarly, responses on questionnaires that ask general practitioners how they manage particular clinical conditions differ significantly from actual clinical practice. w13 An instrument developed in a different time, country, or cultural context may not be a valid measure in the group you are studying. For example, the item “I often attend gay parties” may have been a valid measure of a person's sociability level in the 1950s, but the wording has a very different connotation today.

Reliable questionnaires yield consistent results from repeated samples and different researchers over time. Differences in results come from differences between participants, not from inconsistencies in how the items are understood or how different observers interpret the responses. A standardised questionnaire is one that is written and administered so all participants are asked the precisely the same questions in an identical format and responses recorded in a uniform manner. Standardising a measure increases its reliability.

Just because a questionnaire has been piloted on a few of your colleagues, used in previous studies, or published in a peer reviewed journal does not mean it is either valid or reliable. The detailed techniques for achieving validity, reliability, and standardisation are beyond the scope of this series. If you plan to develop or modify a questionnaire yourself, you must consult a specialist text on these issues. 2 , 3

How should you present your questions?

Questionnaire items may be open or closed ended and be presented in various formats ( figure ). Table B on bmj.com examines the pros and cons of the two approaches. Two words that are often used inappropriately in closed question stems are frequently and regularly. A poorly designed item might read, “I frequently engage in exercise,” and offer a Likert scale giving responses from “strongly agree” through to “strongly disagree.” But “frequently” implies frequency, so a frequency based rating scale (with options such as at least once a day, twice a week, and so on) would be more appropriate. “Regularly,” on the other hand, implies a pattern. One person can regularly engage in exercise once a month whereas another person can regularly do so four times a week. Other weasel words to avoid in question stems include commonly, usually, many, some, and hardly ever. 17 w14

Examples of formats for presenting questionnaire items

Box 2: A closed ended design that produced misleading information

Customer: I'd like to discontinue my mobile phone rental please.

Company employee: That's fine, sir, but I need to complete a form for our records on why you've made that decision. Is it (a) you have moved to another network; (b) you've upgraded within our network; or (c) you can't afford the payments?

Customer: It isn't any of those. I've just decided I don't want to own a mobile phone any more. It's more hassle than it's worth.

Company employee: [after a pause] In that case, sir, I'll have to put you down as “can't afford the payments.”

Closed ended designs enable researchers to produce aggregated data quickly, but the range of possible answers is set by the researchers not respondents, and the richness of potential responses is lower. Closed ended items often cause frustration, usually because researchers have not considered all potential responses (box 2). 18

Ticking a particular box, or even saying yes, no, or maybe can make respondents want to explain their answer, and such free text annotations may add richly to the quantitative data. You should consider inserting a free text box at the end of the questionnaire (or even after particular items or sections). Note that participants need instructions (perhaps with examples) on how to complete free text items in the same way as they do for closed questions.

If you plan to use open ended questions or invite free text comments, you must plan in advance how you will analyse these data (drawing on the skills of a qualitative researcher if necessary). 19 You must also build into the study design adequate time, skills, and resources for this analysis; otherwise you will waste participants' and researchers' time. If you do not have the time or expertise to analyse free text responses, do not invite any.

Some respondents (known as yea sayers) tend to agree with statements rather than disagree. For this reason, do not present your items so that strongly agree always links to the same broad attitude. For example, on a patient satisfaction scale, if one question is “my GP generally tries to help me out,” another question should be phrased in the negative, such as “the receptionists are usually impolite.”

Apart from questions, what else should you include?

A common error by people designing questionnaires for the first time is simply to hand out a list of the questions they want answered. Table C on bmj.com gives a checklist of other things to consider. It is particularly important to provide an introductory letter or information sheet for participants to take away after completing the questionnaire.

What should the questionnaire look like?

Researchers rarely spend sufficient time on the physical layout of their questionnaire, believing that the science lies in the content of the questions and not in such details as the font size or colour. Yet empirical studies have repeatedly shown that low response rates are often due to participants being unable to read or follow the questionnaire (box 3). 3 w6 In general, questions should be short and to the point (around 12 words or less), but for issues of a sensitive and personal nature, short questions can be perceived as abrupt and threatening, and longer sentences are preferred. w6

How should you select your sample?

Different sampling techniques will affect the questions you ask and how you administer your questionnaire (see table D on bmj.com ). For more detailed advice on sampling, see Bowling 20 and Sapsford. 3

If you are collecting quantitative data with a view to testing a hypothesis or assessing the prevalence of a disease or problem (for example, about intergroup differences in particular attitudes or health status), seek statistical advice on the minimum sample size. 3

What approvals do you need before you start?

Unlike other methods, questionnaires require relatively little specialist equipment or materials, which means that inexperienced and unsupported researchers sometimes embark on questionnaire surveys without completing the necessary formalities. In the United Kingdom, a research study on NHS patients or staff must be:

- Formally approved by the relevant person in an organisation that is registered with the Department of Health as a research sponsor (typically, a research trust, university or college) 21 ;

- Consistent with data protection law and logged on the organisation's data protection files (see next article in series) 19

- Accordant with research governance frameworks 21

- Approved by the appropriate research ethics committee (see below).

Box 3: Don't let layout let you down

Meena, a general practice tutor, wanted to study her fellow general practitioners' attitudes to a new training scheme in her primary care trust. She constructed a series of questions, but when they were written down, they covered 10 pages, which Meena thought looked off putting. She reduced the font and spacing of her questionnaire, and printed it double sided, until it was only four sides in length. But many of her colleagues refused to complete it, telling her they found it too hard to read and work through. She returned the questionnaire to its original 10 page format, which made it easier and quicker to complete, and her response rate increased greatly.

Summary points

Questionnaire studies often fail to produce high quality generalisable data

When possible, use previously validated questionnaires

Questions must be phrased appropriately for the target audience and information required

Good explanations and design will improve response rates

In addition, if your questionnaire study is part of a formal academic course (for example, a dissertation), you must follow any additional regulations such as gaining written approval from your supervisor.

A study is unethical if it is scientifically unsound, causes undue offence or trauma, breaches confidentiality, or wastes people's time or money. Written approval from a local or multicentre NHS research ethics committee (more information at www.corec.org.uk ) is essential but does not in itself make a study ethical. Those working in non-NHS institutions or undertaking research outside the NHS may need to submit an additional (non-NHS) ethical committee application to their own institution or research sponsor.

The committee will require details of the study design, copies of your questionnaire, and any accompanying information or covering letters. If the questionnaire is likely to cause distress, you should include a clear plan for providing support to both participants and researchers. Remember that just because you do not find a question offensive or distressing does not mean it will not upset others. 6

As we have shown above, designing a questionnaire study that produces usable data is not as easy as it might seem. Awareness of the pitfalls is essential both when planning research and appraising published studies. Table E on bmj.com gives a critical appraisal checklist for evaluating questionnaire studies. In the following two articles we will discuss how to select a sample, pilot and administer a questionnaire, and analyse data and approaches for groups that are hard to research.

Supplementary Material

This is the first in a series of three articles on questionnaire research

Susan Catt supplied additional references and feedback. We also thank Alicia O'Cathain, Jill Russell, Geoff Wong, Marcia Rigby, Sara Shaw, Fraser MacFarlane, and Will Callaghan for feedback on earlier versions. Numerous research students and conference delegates provided methodological questions and case examples of real life questionnaire research, which provided the inspiration and raw material for this series. We also thank the hundreds of research participants who over the years have contributed data and given feedback to our students and ourselves about the design, layout, and accessibility of instruments.

Contributors and sources: PMB and TG have taught research methods in a primary care setting for the past 13 years, specialising in practical approaches and using the experiences and concerns of researchers and participants as the basis of learning. This series of papers arose directly from questions asked about real questionnaire studies. To address these questions we explored a wide range of sources from the psychological and health services research literature.

Competing interests: None declared.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

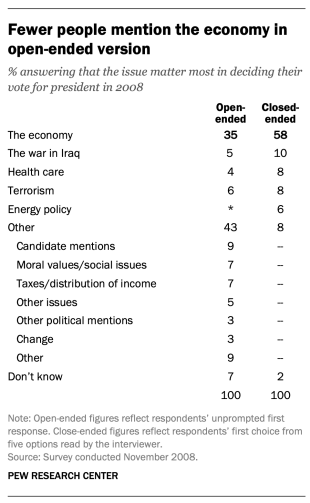

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

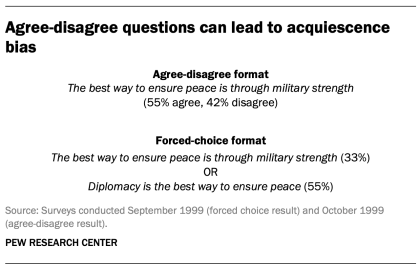

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

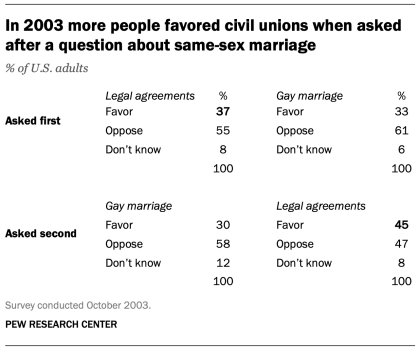

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

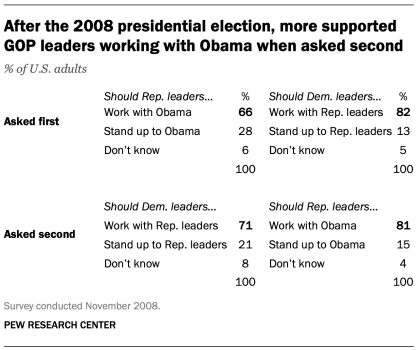

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).