Res Ipsa Loquitur

Definition of res ipsa loquitur, use of res ipsa loquitur, elements of res ipsa loquitur, meeting the first element of res ipsa loquitur, meeting the second element of res ipsa loquitur, meeting the third element of res ipsa loquitur, meeting the fourth element of res ipsa loquitur, res ipsa loquitur vs. prima facie, res ipsa loquitur in practice, the stray barrel of flour, related legal terms and issues.

Res Ipsa Loquitur: Legal Definition, Conditions and Liability

What is res ipsa loquitur.

Res Ipsa Loquitur is a legal doctrine that allows the presumption of negligence in a case where the nature of an accident or injury implies it was likely caused by someone’s negligence, even without direct evidence of the defendant’s actions.

Understanding Res Ipsa Loquitur

In the realm of legal theory and practice, few principles are as intriguing yet often misunderstood as Res Ipsa Loquitur.

This Latin phrase, translating to “the thing speaks for itself,” is a fundamental concept in tort law , particularly in cases of negligence.

Res Ipsa Loquitur is a legal doctrine used to infer negligence from the very nature of an accident or injury , in the absence of direct evidence of the defendant’s action or inaction.

Historical Context of Res Ipsa Loquitur

The doctrine originated from the English case Byrne v Boadle in 1863 , where a barrel of flour fell from a window, hitting a passerby.

The court held that the facts of the case implied negligence because such accidents do not happen without someone’s negligence.

Application of Res Ipsa Loquitur

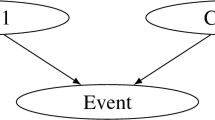

Res Ipsa Loquitur allows a presumption of negligence when:

- The Event is Unusual : The accident is not the type that ordinarily occurs without negligence.

- The Defendant Had Control : The instrumentality or situation causing harm was under the defendant’s control.

- The Plaintiff Was Not at Fault : The plaintiff did not contribute to the cause of the incident.

The Res Ipsa Loquitur Doctrine’s Role

This principle shifts the burden of proof from the plaintiff to the defendant. Once invoked successfully, the defendant must provide an explanation to counter the presumption of negligence.

Case Examples and Judicial Interpretations

Landmark cases.

- Scott v. London and St. Katherine Docks Co . (1865) : Solidified the doctrine, highlighting its necessity in situations where the defendant has exclusive knowledge of the circumstances leading to the incident.

Conditions for Application

For Res Ipsa Loquitur to apply, certain conditions must be met:

- Absence of Direct Evidence : The doctrine is used when there is no direct evidence of how the defendant behaved.

- Control and Management : The defendant must have had exclusive control over the situation or instrumentality that caused the damage.

- Elimination of Alternative Explanations : It must be shown that the injury was not caused by the plaintiff or any third party.

In What Types Of Accidents Is Res Ipsa Loquitur Most Frequently Invoked?

Res Ipsa Loquitur is most frequently invoked in accidents where the cause of injury is not directly observable, but the nature of the accident implies negligence.

This includes scenarios like surgical instruments left inside a patient after surgery, objects falling from buildings, elevator and escalator malfunctions, and incidents where objects under the exclusive control of the defendant cause harm.

Essentially, it is applied in cases where the accident itself indicates a breach of duty that would not ordinarily occur without someone’s negligence.

Implications in Negligence Cases

Shifting the burden of proof.

Res Ipsa Loquitur eases the plaintiff’s burden of proving negligence by creating a legal inference, which the defendant must then refute.

Defence Strategies

Defendants may counter the presumption by demonstrating that other plausible causes could have led to the injury or that they exercised due care.

The Role in Medical Malpractice

In medical malpractice, the doctrine is particularly relevant in situations where the exact cause of harm is unclear, yet the injury typically suggests negligence, such as surgical instruments left inside a patient’s body.

The same general conditions apply, but the control aspect is closely scrutinised, considering the complexities of medical procedures and the involvement of multiple parties.

Res Ipsa Loquitur in Product Liability

In product liability cases , the doctrine of Res Ipsa Loquitur is sometimes applied when a product malfunctions in a way that implies inherent defects, suggesting manufacturer negligence.

How Does Res Ipsa Loquitur Apply To Incidents Involving Multiple Potential Causes Of Harm?

Courts must assess whether the defendant’s control was sufficiently direct and whether other factors could reasonably be excluded as the cause. If exclusive control cannot be established, Res Ipsa Loquitur may not be applicable, necessitating more direct evidence of negligence.

In incidents with multiple potential causes of harm, applying Res Ipsa Loquitur becomes complex. The doctrine typically requires that the instrument causing harm was under the defendant’s exclusive control.

When multiple factors could have contributed to the accident, establishing this exclusive control is challenging.

Criticisms and Limitations

There is a risk that the doctrine may be applied too broadly, leading to unfair presumptions of negligence.

Courts often approach Res Ipsa Loquitur with caution, ensuring that its application is justified and does not replace actual proof of negligence.

The principle continues to evolve, adapting to contemporary legal challenges and the complexities of modern life.

Res Ipsa Loquitur remains a vital tool in negligence litigation, providing a pathway to justice in cases where direct evidence of fault is scarce.

Its careful application underscores the balance between inferring negligence and upholding the burden of proof in the legal system.

- Gopen, G.D., 1987. The state of legal writing: Res ipsa loquitur . Michigan Law Review , 86 (2), pp.333-380.

- Grady, M.F., 1993. Res Ipsa Loquitor and Compliance Error . U. Pa. L. Rev. , 142 , p.887.

- Wansbrough, J.E., 2003. Res ipsa loquitur: History and Mimesis . In Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins (pp. 3-19). Brill.

- Burden of Proof: Legal Definition

- Damages: Legal Definition

- Liability: Legal Definition, Types of Liability

- Personal Injury: Legal Definition, Types, Claim Process

- Private Law: Legal Definition, Branches of Private Law

- Wrongful Death Claims: Legal Definition

Related Articles

Substantive law vs procedural law: definition, legal sources and methods.

What is Substantive Law and Procedural Law? Substantive law defines the rights and obligations of individuals and organisations, while procedural law outlines the process for…

Legal Analytics: Meaning, Litigation Strategy, Practice Management and Future of Legal Analytics

What is Legal Analytics? Legal analytics is the interdisciplinary application of data science, machine learning algorithms, and statistical methods to vast repositories of legal data,…

Common Law vs Civil Law: Definition, Legal Systems and Procedures and Judicial Precedent

What is Common Law and Civil Law? Common Law is a legal system where court judgments and case precedents play a crucial role in legal…

Contract of Service vs Contract for Service: Legal Definition, Status, Benefits and Termination

A Contract of Service is an agreement between an employer and an employee that dictates the terms of employment, while a Contract for Service is…

Arbitration vs Litigation: Conflict Resolution Mechanisms

What is Arbitration and Litigation? Arbitration is a private, flexible dispute resolution process where an appointed arbitrator makes a binding decision. Litigation is a public,…

Legal System: Definition, Legal Framework and Rule of Law

What is a Legal System? A legal system is an organised set of laws and regulations, including the processes and institutions necessary to enforce them,…

CIF vs FOB Contracts: Legal Definition, Transfer of Responsibility, Risks and Marine Insurance

What are CIF and FOB Contracts? CIF (Cost, Insurance, and Freight) contracts require the seller to arrange and pay for the transportation and insurance of…

Juristopedia is a Law Encyclopedia and Legal Educational Guide in Concise English.

Registered Address : 71-75 Shelton St, London WC2H 9JQ, United Kingdom

WEBSITE Information

- Privacy and Cookie Policy

- Terms and Conditions

WEBSITE CONTENT

- Legal Dictionary

Join Thousands of Subscribers Who Read Our Legal Opinions And Case Analysis.

res ipsa loquitur

Primary tabs.

Res ipsa loquitur is Latin for "the thing speaks for itself."

Res ipsa loquitur is a principle in tort law that allows plaintiffs to meet their burden of proof with what is, in effect, circumstantial evidence . The plaintiff can create a rebuttable presumption of negligence by proving that the harm would not ordinarily have occurred without the negligence of the defendant, that the object that caused the harm was under the defendant’s control, and that there are no other plausible explanations.

Prima Facie Case Test:

To prove res ipsa loquitur negligence, the plaintiff must prove 3 things:

- The incident was of a type that does not generally happen without negligence

- It was caused by an instrumentality solely in defendant’s control

- The plaintiff did not contribute to the cause

Limitations on Res Ipsa Loquitur

An injury which would not occur without some fault of the plaintiff (i.e. certain types of slip-and-fall accidents) would necessarily fail the prima facie test, specifically the third element.

Further Reading

For more on res ipsa loquitur, see this Yale Law Review note and this St. John's Law Review note .

For an example of a court applying res ipsa loquitur, see Byrne v Boadle .

[Last updated in May of 2024 by the Wex Definitions Team ]

- LIFE EVENTS

- accidents & injuries (tort law)

- standards of tort liability

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- courts and procedure

- wex definitions

- burden of persuasion

- burden of production

| You might be using an unsupported or outdated browser. To get the best possible experience please use the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Microsoft Edge to view this website. |

What Is Res Ipsa Loquitur? (2024 Guide)

Updated: Feb 3, 2023, 10:06am

Table of Contents

What is res ipsa loquitur, how can you prove res ipsa loquitur, examples of res ipsa loquitur, defending against res ipsa loquitur, frequently asked questions (faqs).

If you are suing someone for negligence, it is important to understand what res ipsa loquitur means. This legal doctrine could affect what you must prove in order to prevail in your legal claim and recover compensation for losses.

This guide to res ipsa loquitur explains how the doctrine works and what it means for you if someone has harmed you.

Res ipsa loquitur is Latin and literally means the thing speaks for itself.

In the context of a legal claim based on negligence, res ipsa loquitur essentially means that the circumstances surrounding the case make it obvious that negligence occurred.

Normally, when a plaintiff pursues an injury claim to recover compensation, the plaintiff must show the defendant breached a legal duty by acting more carelessly than a reasonable person (or reasonable professional) would have. The plaintiff must also show the defendant’s negligence was the direct cause of harm.

In some cases, however, common sense dictates a particular accident would not have happened unless someone was negligent. In these types of situations, the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur applies. The doctrine creates the presumption of negligence simply by a showing of circumstantial evidence, rather than the plaintiff having to provide more solid evidence negligence happened.

In general, there are certain things plaintiffs must show in order for the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur to apply and to create a presumption of negligence. Specifically, the plaintiff must prove the following:

- Common sense dictates the incident wouldn’t have occurred without negligence and that there are no plausible explanations for the incident that don’t suggest negligence

- The defendant was in sole control of whatever caused the incident to occur

- The plaintiff did not contribute to causing their own injuries

It can be much easier to satisfy the burden of proof when a plaintiff can show res ipsa loquitur applies than if the plaintiff must provide more in-depth evidence of negligence.

Examples of res ipsa loquitur can be found in many different kinds of personal injury claims. Some common examples include:

- A person is handed a soda bottle that explodes upon contact. Obviously, absent some type of negligence or wrongdoing, soda bottles are not supposed to explode when someone touches them.

- A doctor operates on the wrong patient or the wrong body part. There is no situation in which any reasonably competent doctor would make this type of mistake without negligence being involved somewhere in the process.

- A vehicle airbag explodes upon impact, sending shrapnel flying through the vehicle and causing injuries. Airbags obviously are not supposed to explode and shoot shrapnel at passengers.

In each of these examples, the incident that caused harm to the victim speaks for itself. There is no need to look more in depth into whether a reasonably competent defendant would have made the same errors in the same way.

Res ipsa loquitur creates a rebuttable presumption of negligence. This means once a plaintiff proves this legal doctrine applies and that they were harmed by an obviously careless action, the defendant can be held liable for any resulting losses unless the defendant can raise a viable defense.

A reputable presumption of negligence can be rebutted with competing evidence from a defendant. For example, a defendant could argue against liability by raising the following defenses.

- The plaintiff contributed to or assumed the risk of injuries

- An intervening act of God or other event was the actual cause of harm, not the defendant’s actions

Determining the viability of a defense can be complicated. For example, in most states, plaintiffs can still pursue a claim for compensation even if they were partly to blame for their injuries. They would just receive reduced compensation, based on the percentage of fault attributed to them versus the defendant.

Because proving res ipsa loquitur can be complicated and because of the possibility a defendant will successfully raise defenses that a plaintiff can counter, it is a good idea to have an experienced legal professional representing you.

A dedicated injury lawyer can help you to understand if the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur applies to your case and, if so, how you can gather the necessary circumstantial evidence to prove the elements of your case and get the compensation that you deserve.

You should call an experienced attorney as soon as possible–especially since res ipsa loquitur cases usually involve obvious negligence for which you should be appropriately compensated.

What does res ipsa loquitur mean?

Res ipsa loquitur is Latin for “the thing speaks for itself.” It is a legal doctrine that applies in tort claims. When an incident obviously would not have occurred absent negligence, a plaintiff can use circumstantial evidence to create a rebuttable presumption the defendant was negligent and thus should be held liable for losses.

What is an example of res ipsa loquitur?

There are many different examples of res ipsa loquitur. A doctor operating on the wrong body part is an example of a situation where this legal doctrine would likely apply. Other examples include a soda bottle that explodes when someone touches it or a flower pot falling from a high distance onto passerby below.

What is the difference between res ipsa loquitur and negligence per se?

Both res ipsa loquitur and negligence per se allow a plaintiff to create a presumption a defendant was negligent and thus should be liable for losses.

When res ipsa loquitur applies, it is because common sense dictates the incident leading to injury wouldn’t have happened absent negligence. When negligence per se applies, negligence can be inferred from the fact the defendant broke a law.

For example, drunk driving that leads to a car crash is an example of negligence per se because it is obviously negligent to break the laws prohibiting drunk driving. But a doctor leaving a sponge inside of a patient is an example of res ipsa loquitur because this wasn’t a violation of any particular law but negligence can still be inferred from the circumstances.

- Los Angeles Personal Injury Lawyers

- San Francisco Personal Injury Lawyers

- San Diego Personal Injury Lawyers

- San Jose Personal Injury Lawyers

- Sacramento Personal Injury Lawyers

- Anaheim Personal Injury Lawyers

- Bakersfield Personal Injury Lawyers

- Santa Ana Personal Injury Lawyers

- Dallas Personal Injury Lawyers

- Houston Personal Injury Lawyers

- Austin Personal Injury Lawyers

- San Antonio Personal Injury Lawyers

- Fort Worth Personal Injury Lawyers

- El Paso Personal Injury Lawyers

- Arlington Personal Injury Lawyers

- Corpus Christi Personal Injury Lawyers

- NYC Personal Injury Lawyers

- Chicago Personal Injury Lawyers

- Atlanta Personal Injury Lawyers

- Philadelphia Personal Injury Lawyers

- Las Vegas Personal Injury Lawyers

- Phoenix Personal Injury Lawyers

- Seattle Personal Injury Lawyers

- Boston Personal Injury Lawyers

- Indianapolis Personal Injury Lawyers

- Baltimore Personal Injury Lawyers

- How To Sue Someone

- Personal Injury Lawsuit

- Wrongful Death Lawsuit

- Slip and Fall Lawsuit

- Personal Injury Settlement Amounts

- Injury Compensation

- How To Start A Class Action Lawsuit

- Suing for Emotional Distress

- Punitive Damages

- Florida Statute of Limitations

- California Statute of Limitations

- What Is A Structured Settlement?

- Dog Bite Lawsuit Guide

- Slander Lawsuit Guide

- What Is A Catastrophic Injury?

- What Is Negligence?

- Contributory Negligence

- Reasonable Person Standard

- Strict Liability

- Vicarious Liability

- Breach of Duty

- What Is Comparative Negligence?

- Assumption Of Risk In Personal Injury Claims

- What Are Intentional Torts?

- What Is Recklessness?

- What Is Property Damage?

- What Is Tort Reform?

- What Is Premises Liability?

- Tort Liability Definition & Examples

Exotic Animal Laws By State 2024 Guide

Best Personal Injury Lawyers Laredo, TX Of 2024

Best Personal Injury Lawyers Gilbert, AZ Of 2024

Best Personal Injury Lawyers Winston-Salem, NC Of 2024

Best Personal Injury Lawyers Toledo, OH Of 2024

Best Personal Injury Lawyers St. Petersburg, FL Of 2024

Christy Bieber has a JD from UCLA School of Law and began her career as a college instructor and textbook author. She has been writing full time for over a decade with a focus on making financial and legal topics understandable and fun. Her work has appeared on Forbes, CNN Underscored Money, Investopedia, Credit Karma, The Balance, USA Today, and Yahoo Finance, among others.

- Results/Verdicts

- Come To You

- Lawyer Referrals

- Legal Dictionary

- CAR ACCIDENTS

- MOTORCYCLE ACCIDENTS

- WRONGFUL DEATH LAW

- TRUCK ACCIDENTS

- PEDESTRIAN ACCIDENTS

- DOG BITE LAWYER

- SPINAL CORD INJURY

- INSURANCE LAWYER

- Testimonials

- Los Angeles

- Orange County

- San Bernardino

- CHP Reports

- Santa Monica

- LAPD Reports

- Personal Injury FAQs

Res Ipsa Cases, Examples and Explanations

Res Ipsa Loquitur is a phrase that has entered the legal lexicon for cases falling under the tort law doctrine of civil negligence . Ordinary negligence is a slightly different situation than Res Ipsa . Here are the history and fascinating modern approach to discussing this legal subject.

Res Ipsa Loquitur and Legal Implications

When learning about the American common law legal tradition, res ipsa loquitur is one of the most common and essential legal theories of monetary recovery . The Latin term means “the thing that speaks for itself.” When dealing with this concept in personal injury law, this concept acts as an evidentiary rule that allows the plaintiff to organize circumstantial evidence into a claim of negligence against the defendant without proving the defendant directly caused the injuries.

The typical law school example includes the exploding glass coke bottle case causing blindness or a flowerpot dropping off a building’s ledge near a window. Whether the occupant or owner was present, a bottle under pressure exploding, or a falling pot from above could maim, injure or kill. Anyone with common sense would know this to be true.

So the law infers defendants’ negligence was afoot because insecure ceramic pots falling, exploding shards of glass shattering, and flying bottle caps from pressure explosions are things that speak for themselves.

Why would someone place unsecured plant containers at locations like ledges or overhangs, making them potentially fall on someone’s head? Do you understand so far?

Negligence Presumed

Because a presumption of negligence exists under res ipsa , the prospective plaintiff may proceed with a cause of action for res ipsa . However, the lines are not as bright as to fault in many other cases. Fortunately for the plaintiff, this is only one of many theories available for a money damages recovery under negligence law. And a series of environmental factors must be considered to show negligent behavior. In such a case, the concept of res ipsa allows the judge or jury to assume actions taken by the defendant would have led to the same result.

Are There Commonalities of Res Ipsa Across Jurisdictions?

This common factor is the so-called ‘common sense provision in civil cases. Most states follow this principle in determining whether the defendant caused the accident.

Most statutes follow the concept that:

- Such an accident could only have occurred due to a person’s negligence.

- The plaintiff or third party could not have caused this event.

- The event occurred due to a breach of the defendant’s duty to the plaintiff.

In these cases, the defendant must be the only person responsible for this injury. Res Ipsa allows the plaintiff to array a preponderance of evidence to prove this is the case. Factors involved include whether or not the defendant had sole control of the object or area that caused the injury. And this could be the case if the defendant allowed a walkway in their apartment building to be unsafe.

In these cases, there is a specific expectation of the defendant’s action relative to the plaintiff. A landlord’s responsibility could include a duty of care, preventing the plaintiff’s harm. If no obligation close to the event exists, res ipsa won’t apply. Imagine a burglar breaking into a home, slipping on a wet floor, and suffering head injuries. However, a landlord’s duty to their tenant to warn against slipping and falling on wet feet remains well settled.

Defending Against Res Ipsa

Plaintiff’s burden proving liability becomes presumed as a matter of law, leaving the plaintiff arguing over amounts of damages owed alone. On the civil claim’s other side, a defendant may defend using several means. Since res ipsa loquitur theory infers negligence, the defendant could potentially shift the burden back to the plaintiff. One burden-shifting method is to argue another person or act of God caused everything.

Defendants can argue plaintiff’s actions caused/contributed to their injuries. Also, the defendant can say intentional misconduct led to the plaintiff’s injury. In that case, Res Ipsa no longer remains viable as a cause of action because no duty of care or outside commitment existed.

- Other Examples:

Examples of res ipsa can include an exploding vehicle tire or airbag while a car travels down the freeway. In a case like this, with possible causes including tread separation, aftermath such as vehicle rollover speaks for itself. In cases like exploding soda and beer bottles, the bottling company would be the at-fault party– as it speaks for itself.

There can be many potential defendants in res ipsa cases, and a skilled attorney can determine who or what they are. Which corporations did not take the proper procedures that led to injury or accident? Top attorneys can identify, most of all, any potentially liable defendants. So there will be those with the experience and background knowledge to make such a distinction. Of particular concern, these experts can discover who breached their duty of reasonable care.

For More Information About Res Ipsa Law

For more information, please get in touch with the legal experts at Ehline Law today. Our team of attorneys has effectively aided clients on both sides of the courtroom in res ipsa and other suits. We can help guide you through the process, offer a free consultation, and discuss your options. We work on a contingency fee basis, so we don’t ask you for any money unless we recover for you. Learn about your potential case today by calling (213) 596-9642.

- A to Z Personal Injury Podcast

- American Motorcycle Law Blog

- Bicycle Accident Blog

- Bus Accident Blog

- Limo Accident Blog

- Pedestrian Accident

- Truck Accident Blog

- Uber and Lyft Ride Sharing Blog Accidents

- Brain Injury Blog

- Burn Injury Blog

- Civil Rights Blog

- Death Law Blog

- Dog Bite Blog

- Elder Nursing Abuse Blog

- Government Tort Blog

- Workers Compensation Blog

- Helicopter Accident Blog

- Construction Accident

- Slip & Fall Blog

- Products Defect Blog

- Recreation-Sports Accident Blog

- Cruise Accident Blog

- Service Related Cancer Blog

- Child Abuse Blog

- Spinal Cord Injury Blog

- Torts, Examples, Explanations

- Train Accidents Blog

- TV, Media & Firm News

- Uncategorized

Firm Archive

- How Does Insurance Decide Auto Accident Fault?

- Updated: Los Angeles Uber and Lyft Collision Statistics

- Fact Check – Hells Angels Arrive in Colorado: Lawyer Reacts to Confronting Venezuelan Gangs

Main Los Angeles Location

Michael Ehline

Michael Ehline is an inactive U.S. Marine and world-famous legal historian. Michael helped draft the Cruise Ship Safety Act and has won some of U.S. history’s largest motorcycle accident settlements. Together with his legal team, Michael and the Ehline Law Firm collect damages on behalf of clients. We pride ourselves on being available to answer your most pressing and difficult questions 24/7. We are proud sponsors of the Paul Ehline Memorial Motorcycle Ride and a Service Disabled Veteran Operated Business. (SDVOB.) We are ready to fight.

Go here for More Verdicts and Settlements.

Please enable JavaScript to use the contact form.

RES IPSA LOQUITUR WITH CASE LAWS

The term “Negligence” is derived from the Latin word “Negligentia” which denotes carelessness, heedlessness, or neglect. Negligence refers to the breach of a legal duty that the defendant owes to the plaintiff caused by an omission to do something that a reasonable or prudent person would

INTRODUCTION

The term “Negligence” is derived from the Latin word “Negligentia” which denotes carelessness, heedlessness, or neglect. Negligence refers to the breach of a legal duty that the defendant owes to the plaintiff caused by an omission to do something that a reasonable or prudent person would ordinarily do. In other words, Negligence refers to an omission to withstand a standard of behavior established to protect society from unreasonable risks. The term “Negligence” is used to hold liability under civil law as well criminal law.

To fix the liability of the defendant under the tort of Negligence to claim compensation for the damages suffered, the plaintiff needs to manifest the following essentials in the court of law :

- There must be a duty of care owed to the plaintiff

- The aforementioned duty owed must be breached

- Due to the breach of the aforementioned duty owed plaintiff must have sustained some sort of damage.

As per general rule, the onus to prove that the defendant is negligent entirely lies on the plaintiff meaning that the initial burden of proving the negligence of the defendant lies on the plaintiff. But if this onus is discharged, then the defendant has to prove in front of the court of law that the incident wasa result of an inevitable accident or contributory negligence on part of the plaintiff. This particular situation employs the use of the doctrine “Res Ipsa Loquitur.”

RES IPSA LOQUITUR

The maxim “Res Ipsa Loquitur” means “the thing speaks for itself.” “It is a maxim of evidentiary potency and consequence, and serves to imply or raise a presumption of negligence as a fact when from the physical facts or situations attending the accident or injury, there is a reasonable probability that it would not have happened if the party having control, management, or supervision, or with whom rests the responsibility for the sound and safe condition of the thing, property, or appliance which is a proximate cause of the accident or injury, had done something differently .” The first evident use of this maxim in common law was in the case of Byrne v. Boadle . To apply the doctrine of “Res Ipsa Loquitur”, the plaintiff has the obligation of proving prerequisite three conditions. The accident or injury must of a kind that ordinarily cannot occur in absence of someone’s negligence, there must bea reasonable intervention that the defendant is blameworthy for negligence which ultimately leads to injuries, and there should be no voluntary conduct or action on the part of the plaintiff”. The maxim “Res Ipsa Loquitur” is applied where there is only one inference from the present facts that the accident could not have occurred but for defendant’s negligence. The “Res Ipsa Loquitur” rule simply shifts the burden of proof so that the defendant is now required to refute the negligence claim made against him rather than the plaintiff showing the defendant’s negligence. The defendant can avoid culpability if he is successful in demonstrating in court that what initially appears to be negligence was caused by the occurrence of some other variables that were out of his control.

CASE LAWS CONCERNING RES IPSA LOQUITUR

STATE OF PUNJAB v. MODERN CULTIVATORS, LADWA

- Case Summary

The plaintiff, who operated the firm Modern Cultivators, sued the State of Punjab as the defendant to claim costs for crops that were damaged by floods in the plaintiff’s field as a consequence of a canal breakdown caused by the State. The plaintiff alleged that there was a breakdown in the western bank of the canal caused by the defendant’s negligence, which eventually resulted in canal water leaking into the plaintiff’s field and creating flooding. According to the Government of Punjab’s reasoning, the rupture occurred at first hand but was quickly repaired, and the plaintiff’s fields were flooded not by canal water but by a severe downpour.

The trial Judge passed an order against the Government of Punjab with compensation, but it was lessened by the High Court. The High Court noted that the engulfment of the fields was due to the water of the canal not by Nallahs. Both parties filed cross-appeals by special leave in the Supreme Court of India.Mr. Sarkar held that the rule of “Res Ipsa Loquitur” can be duly applied here as there would not have been any breach in the banks of the canal if there was reasonable care as well as management was undertaken. Therefore, the breach will be considered prima facie proof of negligence.

- Interpretations

The Bench comprised of Mr. Sarkar and Mr. A.K.(A) Mr. Sarkar and Mr. Hidayatullah’s arguments were on the same lines they both contended that the contention of The State of Punjab regarding not proving of defendant’s negligence by the plaintiff is completely void as it seems that the documents called by the trial court were not produced deliberately. Moreover, taking the case of “ Murugesan Pillai v. Manickavasaka Pandara ” as a precedence, where it was asserted before the court that the required documents that needed to be produced have been destroyed. It was inferred by interpreting the statement of canal officers called before the High Court that the documents were not produced by the defendant intentionally and therefore the fact the defendant was negligent could be established.

Mr. Sarkar further ruled taking the case of “ Scott v. London Dock Co. ” as a precedence, that the rule of “Res Ipsa Loquitur” could explicitly apply to this case as the canal was admittedly in the management of the defendant and no breach of canal banks would have occurred if proper care and management was undertaken.

NIRMALA THIRUNAVAKKARASU v. TAMIL NADU ELECTRICITY BOARD

Three plaintiffs, in this case, are the widow and two sons of the late Thirunavakkarasu. The deceased, who owned a farm and a farmhouse in Sernmedu Village in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, passed away on October 20, 1978. The farm was covered in high-tension cables that were about 440 watts in size. On October 20, 1978, at around 7.45 p.m., the deceased was in the farmhouse and heard a weird cry emerging from the bulls pulling the bullock cart. He quickly left his farmhouse after hearing this to inspect. Unfortunately, as he was moving closer, he stepped on a high-tension wire that had fallen over the fields and was instantly electrocuted to death.There were two defendants: the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board and Pykara Electricity System. They claimed that the high-tension wire snapped because of a torrential downpour, thunder, and strong winds. They argued that it qualified as an Act of God or a Force Majeure, thus they weren’t at fault.

The court contended that overhead high-tension wires are highly minacious and can cause far-reaching consequences if any animal or human being comes in contact with it. The electricity board should take the necessary care and precautions when installing them to prevent them from breaking and falling.If such an incident occurs, then a direct inference can be drawn that there has been heedlessness, carelessness, or negligence on the part of the Electricity Board. The Electricity Board has an obligation of rendering the live wire running over a street, or public place powerless in case it snaps and fall downs under Rule 91 of the Indian Electricity Rules, 1956. The fact that the overhead high-tension wire that snapped and fell on the fields of the deceased continued to be alive ultimately reflects negligence on the part of the Electricity Board as they did not undertake necessary precautionary step needed in these circumstances.

Additionally, the Electricity Board did not take the simple precaution of periodically inspecting lines. In the opinion of the court, the “Res Ipsa Loquitur” rule applies in the aforementioned case given the circumstantial as well as relevant facts.

“Res Ipsa Loquitur” is a maxim that stands for “Thing speaks for itself.”It shifts the onus or responsibility from the plaintiff to the defendant on proving that the defendant was not negligent, if he fails to satisfy the court regarding the same then the defendant is held liable for negligence and is made to compensate or reimburse the plaintiff for the damages or injuries caused owing to misconductfrom the side of the defendant. The rule of “Res Ipsa Loquitur” applies where the defendant is solely responsible for the conditions which eventually were the cause of the accident. Before the application of this rule, it must be inspected whether the defendant had sole control over the conditions that were responsible for the accident. It must also be confirmed that the plaintiff himself did not contribute to the cause directly responsible for the accident. Further, it needs to be established that the incident was of the type which generally would not have happened without negligence.

Author(s) Name: Aditya Bashambu (National Law University Odisha)

Abductive Inference in Legal Reasoning: Resolving the Question of Res Ipsa Loquitur’s Procedural Effect

- First Online: 17 December 2021

Cite this chapter

- Douglas Lind 32

Part of the book series: Logic, Argumentation & Reasoning ((LARI,volume 23))

460 Accesses

This chapter examines the relevance of C.S. Peirce’s notion of abductive inference for law and the formation of legal concepts. The importance of this examination comes from the fact that several doctrinal practices in diverse areas of law rely on logical inferences that defy neat explanation under standard forms of deductive or inductive logic. I argue that abduction resolves some of these logical infirmities, providing the logic underlying certain doctrines or conceptual practices common in modern law. My analysis concentrates on the common law tort maxim res ipsa loquitur (‘the thing speaks for itself’). This is for two reasons. First, as much as any legal concept, res ipsa loquitur manifests the form and conditions of abductive inference. Second, though it entered English common law over 150 years ago and remains today a form of inferential reasoning used in negligence cases throughout most of the common law world, res ipsa loquitur is still highly controversial. Several issues affecting its force and effect split courts and prevent it from receiving uniform application across jurisdictions. The most consequential issue is whether it authorizes a burden-shifting presumption of negligence or only a permissible evidentiary inference left to the discretion of the fact-finder. This is the central issue of res ipsa loquitur’s procedural effect. It continues to confound, I argue, in part because of the maxim’s little understood logical foundation in abduction. This chapter aims to unfold that foundation. In doing so, it establishes three propositions: (1) abduction is a suitable form of logic for legal reasoning; (2) abduction is the form of logic used by the English Court of the Exchequer in Byrne v. Boadle and Scott v. London and St. Katherine Docks Co. , the birth-cases to the tort maxim res ipsa loquitur ; and (3) recognizing abduction as the logic underlying res ipsa loquitur resolves the perennial issue of its procedural effect in favor of the permissible inference theory.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Defeasibility, Law, and Argumentation: A Critical View from an Interpretative Standpoint

Legal Facts and Reasons for Action: Between Deflationary and Robust Conceptions of Law’s Reason-Giving Capacity

The reasonable doubt standard as inference to the best explanation

This issue of res ipsa loquitur’s procedural effect has ensnared courts and commentators for many years. E.g. , Hanna Katz, The New Interpretation of Res Ipsa Loquitur , 17 S t . J ohn ’ s L. R ev . 117, 118 (1943) (“As to the procedural effect of the doctrine, the courts have … nowhere up to this date given an adequate definition.”); William L. Prosser, The Procedural Effect of Res Ipsa Loquitur , 20 M inn . L. R ev . 241, 242 (1936) (arguing there is “no uniform procedural effect of res ipsa loquitur,”); Stanley Schiff, A Res Ipsa Loquitur Nutshell , U. T oronto L.J. 451, 451 (1976) (claiming the main confusion with res ipsa loquitur is whether it “permits the trier of fact to infer, or compels the trier to determine” that the defendant acted negligently); Bernard W. Weitzman, The Procedural Effect of Res Ipsa Loquitur in Missouri , 1953 W ash . U. L. Q. 464, 464 (maintaining the maxim’s “mass of perplexing and baffling decisions” are due largely to “conflicting views concerning the procedural consequences of the application of the doctrine.”); Note, Are We Allowing the Thing to Speak for Itself – Linnear v. CenterPoint Energy and Res Ipsa Loquitur in Louisiana , 71 L a . L. R ev . 1091, 1105 (2011) (arguing that having “ res ipsa loquitur amount to a rebuttable presumption, as opposed to a permissive inference, is a more equitable procedural effect.”); Note, Res Ipsa Loquitur and Expert Opinion Evidence in Medical Malpractice Cases: Strange Bedfellows , 82 V a . L. R ev . 325 (1996) (noting how jury instructions complicate “the already complex debate over the procedural effect of res ipsa loquitur.”).

See Charles Sanders Peirce, Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis , 13 P opular S ci . M onthly 470 (1878), reprinted in 2 C ollected P apers of C harles S anders P eirce 619 (Charles Hartshorne & Paul Weiss eds., Harvard UP 1935), and reprinted in 3 W ritings of C harles S. P eirce 323 (Christian J. W. Kloesel ed., Indiana UP 1986). I follow the standard convention of providing, as appropriate, primary and parallel citations to Peirce’s writings that appear in either or both of the multi-volume C ollected P apers or W ritings of C harles S. P eirce . Hereinafter, these works will be cited in conventional form as, respectively, CP vol.paragraph (e.g., CP 6.619), and W vol.page (e.g., W 3.323).

See K.T. F ann , P eirce ’ s T heory of A bduction 5 (Martinus Nijhoff 1970) (noting that Peirce developed his theory of abduction in “fragmentary” fashion across several writings representing “several different views” of the subject).

See C harles S anders P eirce , P ragmatism as a P rinciple and M ethod of R ight T hinking : T he 1903 H arvard L ectures on P ragmatism (Patricia Ann Turrisi ed., SUNY Press 1997) [hereinafter T he 1903 H arvard L ectures ], CP 5.14.

See id . at 218, 248, CP 5.146, 5.195 (acknowledging that his writings on abduction have been inconsistent and are easily misunderstood).

See e.g. , Harry G. Frankfurt, Peirce’s Notion of Abduction , 55 J. P hil . 593, 593 (1958) (maintaining that Peirce never gave a coherent systematic account of abduction); Jaakko Hintikka, What is Abduction? The Fundamental Problem of Contemporary Epistemology , 34 T ransactions C.S. P eirce S oc ’ y 503 (1998) (identifying and attempting to solve the problems that Peirce’s idea of abduction created for contemporary epistemology).

See P eter L ipton , I nference to the B est E xplanation (2d ed., Routledge 2004); R. A. Fumerton, Induction and Reasoning to the Best Explanation , 47 P hil . S ci . 589 (1980); Gilbert Harman, The Inference to the Best Explanation , 74 P hil . R ev . 88 (1965).

E.g. , P eter G odfrey -S mith , T heory and R eality : A n I ntroduction to the P hilosophy of S cience 43 (Univ. of Chicago Press 2003).

Norwood Russell Hanson, Is There a Logic of Scientific Discovery? 38 A ustralasian J. P hil . 91 (1960). See generally Sami Paavola, Hansonian and Harmanian Abduction as Models of Discovery , 20 I nt ’ l S tud . P hil . S cience 93 (2006).

See, e.g. , Peirce, Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis , supra note 2 at 471–72, CP 2.623–24, W 3.325–26.

E.g. , CP 5.578–81; C harles S anders P eirce , R easoning and the L ogic of T hings : T he C ambridge C onferences L ectures of 1898 at 141–42 (Kenneth Laine Ketner ed., Harvard UP 1992).

See P hilosophical W ritings of P eirce 151 (Justus Buchler ed., Dover Pub. 1955), CP 6.525.

Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis , supra note 2 at 472, CP 2.624, W 3.326.

T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 218, CP 5.145. See Chihab El Khachab, The Logical Goodness of Abduction in C.S. Peirce’s Thought , 49 T ransactions C.S. P eirce S oc ’ y 157, 162 (2013) (describing the purpose of abduction as “to provide hypotheses which, when subjected to experimental verification, will provide true explanations.”).

See T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 217–18, 225–31, CP 5.144–45, 5.161–74; Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis , supra note 2 at 471–72, at CP 2.623–24, W 3.324–26; Methods for Attaining Truth , CP 5.574, 5.590.

See, e.g. , Fumerton, supra note 7 at 592–99 (arguing that abduction can be reduced to ordinary statistical inductive inference); Harman, supra note 7 at 91–95 (treating induction as a special type of abduction); Hintikka, supra note 6 at 524 (observing that many philosophers incorrectly “bracket abductive inference with inductive inference.”).

T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 230, CP 5.172.

See J ohn S tuart M ill , A S ystem of L ogic , R atiocinative and I nductive , in 7 C ollected W orks of J ohn S tuart M ill 292–93 (Univ. of Toronto Press 1973). See also Malcom Forster, The Debate Between Whewell and Mill on the Nature of Scientific Induction , in H andbook of the H istory of L ogic , V ol . 10: I nductive L ogic , 93–115 (Dov M. Gabbay et al. eds., Elsevier 2011) (detailed, critical account of Mill’s claim that Kepler offered only a description of observed data).

P hilosophical W ritings of P eirce , supra note 12 at 154, CP 1.71.

See id . at 154–56, CP 1.72–74; Charles S. Peirce, The Fixation of Belief , 12 P opular S ci . M onthly 1, 2, CP 5.358, 5.362, W 3.242, 3.243.

P hilosophical W ritings of P eirce , supra note 12 at 156, CP 1.74. See N orwood R ussell H anson , P atterns of D iscovery : A n I nquiry into the C onceptual F oundations of S cience 72–89 (Cambridge UP 1958) (agreeing with Peirce that Kepler models the logic of scientific discovery, and providing a detailed account of how Kepler reasoned through and rejected several hypotheses until ultimately positing the elliptical orbit hypothesis).

B ertrand R ussell , T he P roblems of P hilosophy 67 (Oxford UP 1912).

P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 245, CP 5.189.

Id. at 250, CP 5.197.

Id. at 246, CP 5.189.

See CP 5.60, 6.528, 6.532. See also F ann , supra note 3 at 24, 47–51.

See H anson , supra note 21 at 84.

Methods for Attaining Truth , supra note 15 at CP 5.590.

H enrik I bsen , A n E nemy of the P eople 28, 30 (Nicholas Rudall trans., Ivan R. Dee, Inc. 2007).

P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 230, CP 5.171.

Id. at 249, CP 5.195. Accord id . at 218, CP 5.145 (“Induction is the experimental testing of a theory.”).

E.g. , K arl R. P opper , T he L ogic of S cientific D iscovery 32–33 (Hutchinson Educ. 1959).

See P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 230, 249, CP 5.171, 5.195. See also F ann , supra note 3 at 30, 42.

P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 230, CP 5.171. See also F ann , supra note 3 at 42–43.

I bsen , supra note 31 at 29.

Id . at 48.

P hilosophical W ritings of P eirce , supra note 12 at 151, CP 6.525.

See, e.g. , P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 249, 250, CP 5.196, 5.197. See also F ann , supra note 3 at 48–51.

See F ann , supra note 3 at 51–54 (discussing Peirce’s failure to offer a justification for abduction). But cf. Khachab, supra note 14 at 171–72 (offering a justificatory interpretation of Peirce’s theory of abduction).

See P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 230, 249, CP 5.171, 5.196.

See id . at 247, 249, CP 5.192, 5.196.

Bas C. van Fraassen, The Pragmatic Theory of Explanation , in T heories of E xplanation 136, 153 (Joseph C. Pitt ed., Oxford UP 1988).

See Gerhard Schurz, Patterns of Abduction , 164 S ynthese 201, 207, 209 (2008). See also James J. Heckman and Burton Singer, Abducting Economics , 107 A mer . E con . R ev .: P apers & P roc . 298, 299 (2017) (“Abduction is a context-dependent art form in both practice and exposition.”).

See P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 250–51, 283–84, CP 5.197–200.

See P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 249, CP 5.196; Charles Sanders Peirce, How to Make Our Ideas Clear , 12 P opular S ci . M onthly 286 (1878), CP 5.388, 5.402, 5.406, W 3.257, 3.266, 3.271–72.

See, e.g. , C ornelis de W aal , P eirce : A G uide for the P erplexed 63–66 (Bloomsbury 2013); Tjerk Gauderis & Frederik van de Putte, Abduction of Generalizations , 27 T heoria 345 (2012); Michael H.G. Hoffmann, “Theoretic Transformations” and a New Classification of Abductive Inferences , 46 T ransactions C.S. P eirce S oc ’ y 570 (2010); Michael Hoffmann, Problems with Peirce’s Concept of Abduction , 4 F oundations S ci . 271 (1999); Anya Plutynski, Four Problems of Abduction: A Brief History , 1 HOPOS: J. I nt ’ l S oc ’ y H ist . P hil . S ci . 227 (2011).

See D avid A. S chum , T he E vidential F oundations of P robabilistic reasoning (2001); David A. Schum, Species of Abductive Reasoning in Fact Investigation in Law , in T he D ynamics of J udicial P roof : C omputation , L ogic , and C ommon S ense 307 (Marilyn MacCrimmon & Peter Tillers eds., Physica-Verlag 2002); David A. Schum, Marshalling Thoughts and Evidence during Fact Investigation , 40 S. T ex . L. R ev . 401 (1999); David A. Schum & Peter Tillers, A Theory of Preliminary Fact Investigation , 24 U.C. D avis L. R ev . 931 (1991); David A. Schum, Probability and the Processes of Discovery, Proof, and Choice 66 B.U. L. Rev. 825 (1986).

See Daubert v. Merrell-Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

See Carl F. Cranor, Justice, Inference to the Best Explanation, and the Judicial Evaluation of Scientific Evidence , in L aw and S ocial J ustice 67 (Joseph Keim Campbell, Michael O’Rourke, & David Shier eds., MIT Press 2005).

See Scott Brewer, Scientific Expert Testimony and Intellectual Due Process , 107 Y ale L.J. 1540, 1658–71 (1998).

See Scott Brewer, Exemplary Reasoning: Semantics, Pragmatics, and the Rational Force of Legal Argument by Analogy , 109 H arv . L. R ev . 923, 945–49, 978–82, 1021–26 (1996)

See A malia A maya , T he T apestry of R eason : A n I nquiry into the N ature of C oherence and its R ole in L egal A rgument 196–207, 503–12 (Hart Pub. 2015).

2 H&C 722, 159 Eng.Rep. 299 (Ex.Ch. 1863).

Id . at 725, 728, 159 Eng.Rep. at 300, 301.

3 H&C 596, 159 Eng.Rep. 665 (Ex.Ch. 1865).

Id . at 601–02, 159 Eng.Rep. at 667.

Moore v R Fox & Sons [1956] 1 QB 596, 611 (Evershed MR).

See, e.g. , Schellenberg v Tunnel Holdings Pty Ltd. (2000) 200 CLR 121, [2000] HCA 18 (Australia); Richards v. Swansea NHS Trust [2007] EWHC 487 (QB), (2007) 96 BMLR 180 (England); Ng Chun Pui v. Lee Chuen Tat [1988] RTR 298 (PC) (Hong Kong); In Matter of Estate of Njau [2013] eKLR (Civ.App. 2077 of 1999) (HC at Nairobi) (Kenya); Avis Rent a Car Ltd. v Mainzeal Group Ltd. [1995] 3 NZLR 357 (HC) (New Zealand); Francis Trindade and Keng Feng Tan, “Res Ipsa Loquitur: Some Recent Cases in Singapore and Its Future,” 2000 S ing . J. L egal S tud . 186 (2000) (Singapore); J ames H enderson , J r . & R ichard N. P earson , T he T orts P rocess , 364 (1975) (“Res ipsa loquitur is as close to being a universal doctrine of tort law in [the United States] as any could be.”) (United States). Among common law countries, only Canada does not recognize res ipsa loquitur . See Fontaine v. British Columbia (Official Administrator) [1998] 1 S.C.R. 424.

See, e.g. , Mullen v. St. John, 57 N.Y. 567 (1874) (injury caused when part of building fell); Cincinnati Traction Co. v. Holzenkamp, 74 Ohio St. 379, 78 N.E. 529 (1906) (trolley pole fell on embarking passenger); Kaples v. Orth, 61 Wis. 531, 21 N.W. 633 (1884) (while sitting in a stairway, plaintiff struck by block of ice that fell from shoulder of defendant’s agent); Kearney v. London, B. & S. C. Ry. Co., 1870 LR [5 QB] 411 [1870] (injury caused by brick falling off bridge wall).

E.g. , Drewick v. Interstate Terminals, Inc., 42 Ill.2d 345, 247 N.E.2d 877 (1969) (plaintiff struck on head and shoulders when steel ventilator-window sash fell from building); Anderson v. Service Merchandise Co., Inc., 240 Neb. 873, 885, 485 N.W.2d 170, 178 (1992) (light fixture fell on patron in defendant’s business establishment).

See, e.g. , Lowrey v. Montgomery Kone, Inc., 202 Ariz. 190, 42 P.3d 621 (Ariz. App. 2002) (passenger elevator); Cobb v. Marshall Field & Co., 22 Ill.App.2d 143, 159 N.E.2d 520 (1959) (freight elevator); D’Ardenne v. Strawbridge & Clothier, Inc., 712 A.2d 318 (Pa.Super. 1998) (escalator).

E.g. , Phillips v. Delaware Power & Light Co., 57 Del. 466, 202 A.2d 131 (1964) (utility company held responsible under res ipsa loquitur for natural gas explosion after road paving contractor punctured gas transmission line); Foster v. City of Keyser, 202 W.Va. 1, 501 S.E.2d 165 (1997) ( res ipsa loquitur applicable where natural gas leaked from underground transmission line, flowed through sewer line into house, there igniting and exploding).

See Blankenship v. Wagner, 261 Md. 37, 273 A.2d 412 (1971) (delivery worker injured when dilapidated stair collapsed beneath his feet); Gow v. Multnomah Hotel, Inc., 191 Or. 45, 224 P.2d 552 (1950) (coffee shop patron injured when counter stool broke).

See, e.g. , Roddiscraft, Inc. v. Skelton Logging Co., 212 Cal.App.2d 784, 805–06, 28 Cal.Rptr. 277, 289–90 (1963) (forest fire caused by tractor operated without a spark arrester); Clinkscales v. Nelson Sec., Inc., 697 N.W.2d 836, 847 (Iowa 2005) (grease fire at bar grill).

E.g. , Smith v. Kennedy, 43 Ala.App. 554, 195 So.2d 820 (1966) (chemical hair treatment).

E.g. , Ballard & Ballard Co. v. Jones, 246 Ala. 478, 21 So.2d 327 (1945) (poison in bag of flour); LaMack v. Fontainebleau Hotel Corp., 186 So.2d 31, 32 (Fla.App. 1966) (glass or crockery in food); Duval v. Coca-Cola Bottling Co., 329 Ill.App. 290, 293, 68 N.E.2d 479, 481 (1946) (dead mouse in soda bottle); Brumberg v. Cipriani USA, Inc., 973 N.Y.S.2d 401, 403–04, 110 A.D.3d 1198 (2013) (shard of wood in hors d’oeuvres). See also George S. Goodspeed, Jr., Application of the Doctrine of Res Ipsa Loquitur to Food Cases , 3 U. M iami L. R ev . 613 (1949).

See, e.g. , Atlanta Coca-Cola Bottling Co. v. Burke, 109 Ga.App. 53, 134 S.E.2d 909 (1964); Stolle v. Anheuser-Busch, Inc., 307 Mo. 520, 271 S.W. 497, 499–500 (1925).

See, e.g. , Smith v. Hollander, 85 Cal.App. 535, 259 P. 958 (1927) (stating that “[w]hen an automobile leaves its accustomed place of travel in the street, runs upon the sidewalk, and there strikes a pedestrian, the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur has been generally held to apply”); Kendrick v. Pippin, 252 P.3d 1052, 1061 (Colo. 2011) (observing that the most common res ipsa loquitur auto accident cases are rear end collisions and driving on the wrong side of road); Apuzzio v. J. Fede Trucking, Inc., 355 N.J.Super. 122, 809 A.2d 812 (App.Div. 2002) (noting that “wheels coming off moving vehicles are a classic occasion for application of the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur .”).

E.g. , Waite v. Pacific Gas & Elec. Co., 56 Cal.App.2d 191, 132 P.2d 311 (1942) (passenger injured from fall when streetcar suddenly jerked); Misner v. Hawthorne, 168 Kan. 279, 212 P.2d 336 (1949) (passenger injured when bus struck side of bridge); Hedges v. Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pac. R.R. Co., 61 Wash.2d 418, 379 P.2d 199 (1963) (passenger injured when axle broke, causing train to jerk violently).

See Johnson v. United States, 333 U.S. 46 (1949).

See, e.g. , Sides v. St. Anthony’s Med. Ctr., 258 S.W.3d 811 (Mo. 2008) (applying maxim where plaintiff was infected by E. coli during surgery); Maciag v. Strato Med. Corp., 247 N.J.Super. 447, 460, 644 A.2d 647 (App.Div. 1994) (giving “collective application” of maxim to physicians, hospital, and manufacturer, after catheter fragmented inside plaintiff’s decedent); Fessenden v. Robert Packer Hosp., 2014 Pa.Super. 154, 97 A.3d 1225, 1233 (2014) (noting, in case involving surgical sponge left in patient, that “our courts long have cited the proverbial ‘sponge left behind’ case as a prototypical application of res ipsa loquitur.”); Pacheco v. Ames, 149 Wash.2d 431, 69 P.3d 324 (2003) (oral surgery on wrong side of plaintiff’s mouth).

William L. Prosser, Res Ipsa Loquitur in California , 37 C al . L. R ev . 183, 186 (1949).

Id. at 183.

See Potomac Edison Co. v. Johnson, 160 Md. 33, 152 A. 633, 636 (1930) (Bond, C.J., dissenting) (urging that res ipsa loquitur be abandoned in Maryland since it “adds nothing to the law, has no meaning which is not more clearly expressed for us in English, and brings confusion to our legal discussions.”); William H. McBratney, Res Ipsa Loquitur , 1952 W ash . U.L.Q. 542, 542 (1952) (stating the maxim “is worse than a doctrine incapable of definition; it is a source of ill-considered rules of law.”); Prosser, The Procedural Effect of Res Ipsa Loquitur , supra note 1 at 241, 270 (arguing that res ipsa loquitur is a “source of endless confusion” that does “little to clarify and much to confuse the issues of a case.”).

E.g. , H enry J. S teiner , M oral A rgument and S ocial V ision in the C ourts 24 (Univ. of Wisconsin Press 1987); G. E dward W hite , T ort L aw in A merica : A n I ntellectual H istory 198–202 (Oxford UP 1985); Fleming James, Jr., Proof of the Breach in Negligence Cases (Including Res Ipsa Loquitur) , 37 V a . L. R ev . 179, 198–99 (1951); Ezra Ripley Thayer, Liability Without Fault , 29 H arv . L. R ev . 801, 807 (1916).

E.g. , Ratcliffe v. Plymouth & Torbay Health Auth. [1998] PIQR 170 (Hobhouse LJ).

See, e.g. , Zukowsky v. Brown, 79 Wash.2d 586, 592, 488 P.2d 269 (1971) (noting that over the generations since res ipsa loquitur was “born into the law of torts in 1863,… the phrase has developed an almost impenetrable crust.”); Prosser, Res Ipsa Loquitur in California , supra note 75 at 183 (suggesting that res ipsa loquitur has been “dignified and magnified by the cloak of the learned tongue”).

Ballard v North British Railway Co [1923] SC 43 (HL) at 56.

J ohn G. F leming , A n I ntroduction to the L aw of T orts 149 (2d ed., Clarendon Press 1985).

See J ohn F rederic C lerk & W illiam H arry B arber L indsell , C lerk and L indsell on T orts ¶967 (13th ed., Sweet & Maxwell 1969); J ohn G. F leming , T he L aw of T orts 289 (sixth ed., Law Book Co. 1983); A mer . L aw I nst ., R estatement (T hird ) of T orts : L iability for P hysical H arm §17 (2009); A mer . L aw I nst ., R estatement (S econd ) of T orts §328D (1965); 4 W igmore , E vidence §2509 (first ed. 1905).

4 W igmore , supra note 83 at §2509.

W illiam L. P rosser , H andbook of the L aw of T orts §39 at 214 (fourth ed. 1971). This statement appeared initially in the second edition of Prosser’s L aw of T orts (§42 at 201 (2d ed. 1941)), and again in the third edition (§39 at 218 (3d ed. 1964)). Accord Prosser, The Procedural Effect of Res Ipsa Loquitur , supra note 1 at 242 (describing Wigmore’s formula as “more or less accepted.”).

See Prosser, Res Ipsa Loquitur in California , supra note 75 at 187–88.

See R estatement (S econd ) of T orts , supra note 83 at §328D.

See id . at §328D Comment g , which states in part, “[E]xclusive control is merely … one fact which establishes the responsibility of the defendant; and if it can be established otherwise, exclusive control is not essential to a res ipsa loquitur case.”

Id . at §328D(1)(b).

See id. at §328D(2)–(3).

See 4 W igmore , supra note 83 at §2509. While Wigmore characterized res ipsa loquitur as authorizing a presumption, he acknowledged that the case law on its procedural effect was unsettled. He wrote: “Whether the rule (res ipsa) creates a full presumption, or merely satisfies the plaintiff’s duty of producing evidence sufficient to go to the jury, is not always made clear in the ruling.” 4 W igmore , E vidence §2509 (3d ed. 1940).

R estatement (S econd ) of T orts , supra note 83 at §328D Comment b.

See, e.g. , P rosser , H andbook of the L aw of T orts , supra note 85 at §39, 221 (claiming that “much confusion would be avoided, if the idea of ‘control’ were disregarded altogether, and we were to say merely that the apparent cause of the accident must be such that the defendant would be responsible for any negligence connected with it.”); Prosser, The Procedural Effect of Res Ipsa Loquitur , supra note 1 at 262 (arguing that there is “no uniform procedural effect of res ipsa loquitur,” as it permits either a permissible inference or a presumption, depending upon a case’s factual circumstances); id . at 257–59, 262, 270–71 (contending that the maxim is just a form of circumstantial evidence).

R estatement (T hird ) of T orts , supra note 83 at §17.

See id . at §17 Comment b .

Id . at §17 Comment h .

C lerk and L indsell , supra note 83.

F leming , T he L aw of T orts , supra note 83.

C lerk and L indsell , supra note 83 at ¶967(2).

Id . at ¶967(1).

Id . at ¶967(3).

F leming , T he L aw of T orts , supra note 83 at 289.

See id . at 291–93.

See id . at 288–89, 296–97.

See id . at 296–99.

See id. at 296–97.

See, e.g. , Widmyer v. Southeast Skyways, Inc., 584 P.2d 1, 11 (Alaska 1978); Otis Elev. Co. v. Tuerr, 616 A.2d 1254, 1258 (D.C. 1992); Spidle v. Steward, 79 Ill.2d 1, 5, 37 Ill.Dec. 326, 328, 402 N.E.2d 216, 218 (1980); Bias v. Montgomery Elev. Co., 216 Kan. 341, 342, 532 P.2d 1053, 1055 (1975); Dermatossian v. New York City Trans. Auth., 67 N.Y.2d 219, 226 (1986); Victory Park Apts, Inc. v. Axelson, 367 N.W.2d 155, 159 (N.D. 1985); Gow v. Multnomah Hotel, 191 Or. 45, 52, 224 P.2d 552, 554–55 (1950); Zukowsky v. Brown, 79 Wash.2d 586, 593, 488 P.2d 269, 274 (1971); Royal Furniture Co. v. City of Morgantown, 164 W.Va. 400, 405, 263 S.E.2d 878, 882 (1980); Ryan v. Zweck-Wollenberg Co., 266 Wis. 630, 639, 64 N.W.2d 226, 231 (1954).

E.g. , Chapman v. Harner, 339 P.3d 519, 521 (Colo. 2014); Gilbert v. Korvette’s Inc., 457 Pa. 602, 609–15, 827 A.2d 94 (1974).

Brown v. Poway Unified Sch. Dist., 4 Cal.4th 820, 825–26, 15 Cal.Rptr. 679, 682, 843 P.2d 624, 627 (1993).

See e.g. , Barretta v. Otis Elev. Co., 242 Conn. 169, 173–74, 698 A.2d 810, 812 (1997); Shull v. B.F. Goodrich Co., 477 N.E.2d 924, 927 (Ind.App. 1985); Weyerhaeuser Co. v. Thermogas Co., 620 N.W.2d 819, 831 (Iowa 2000); Haddock v. Arnspiger, 793 S.W.2d 948, 950 (Tex. 1990). Cf . Woosley v. State Farm Ins. Co., 117 Nev. 182, 18 P.3d 317, 321–22 (2001) (retaining Wigmore’s first two elements, but dropping the third to bring the maxim in line with the state’s comparative negligence statute).

Sides v. St. Anthony’s Med. Ctr., 258 S.W.3d 811, 814 (Mo. 2008).

McLaughlin Freight Lines, Inc. v. Gentrup, 281 Neb. 725, 728, 798 N.W.2d 386, 389 (2011).

See C lerk and L indsell , supra note 83 at ¶967(3).

Barker v. Clark, 343 Ark. 8, 33 S.W.3d 476 (2000).

See, e.g. , PacifiCorp v. Northwest Pipeline GP, 879 F.Supp.2d 1171, 1184 n.2 (D.Or. 2012) (“ Res ipsa loquitur is merely a theory by which negligence is proven, not an independent negligence claim.”); Gicking v. Kimberlin, 170 Cal.App.3d 73, 78, 215 Cal.Rptr. 834, 837 (1985) ( res ipsa loquitur “is not an independent ground of liability.”); Cruz v. DaimlerChrysler Motors Corp., 66 A.3d 446, 449 n.3 (R.I. 2013) ( res ipsa loquitur “is not an independent cause of action, but rather a doctrine under which a plaintiff may establish a prima facie case of negligence.”); Haddock v. Arnspiger, 793 S.W.2d 948, 950 (Tex. 1990) ( res ipsa loquitur is “not a separate cause of action from negligence.”).

Nearly all jurisdictions treat res ipsa loquitur as strictly a procedural or evidentiary rule. See, e.g. , Stewart v. Ford Motor Co., 553 F.2d 130, 137 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (“res ipsa loquitur, being a rule of evidence, is procedural”); Carlos v. MTL, Inc., 77 Hawai’i 269, 277, 883 P.2d 691, 699 (App. 1994) (describing res ipsa loquitur as “purely a procedural or evidentiary rule, rather than a substantive rule.”); Weyerhaeuser Co. v. Thermogas Co., 620 N.W.2d 819, 831 (Iowa 2000) (maxim is “only a rule of evidence … not a rule of substantive law”); Roberts v. Weber & Sons, Co., 248 Neb. 243, 533 N.W.2d 664, 667 (1995) (maxim is “not a matter of substantive law, but … a procedural matter”); Myrlak v. Port Auth., 157 N.J. 84, 723 A.2d 45, 51 (1999) (noting that res ipsa loquitur is “not a theory of liability; rather, it is an evidentiary rule”); Jennings Buick, Inc. v. City of Cincinnati, 63 Ohio St.2d 167, 169, 406 N.E.2d 1385 (1980) (“The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur is not a substantive rule of law furnishing an independent ground for recovery; rather, it is an evidentiary rule”); Schellenberg v. Tunnel Holdings Pty Ltd. (2000) 200 CLR 121, 140, [2000] HCA 18 (“ res ipsa loquitur is merely a mode of inferential reasoning and is not a rule of law.”).

See San Juan Light & Transit Co. v. Requena, 224 U.S. 89, 97 (1912) (remarking that res ipsa loquitur “is of restricted scope”); Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Hughes Supply, Inc., 358 So.2d 1339, 1341 (Fla. 1978) (describing res ipsa loquitur as “a doctrine of extremely limited applicability.”); Plumb v. Richmond Light & R.R. Co., 233 N.Y. 285, 135 N.E. 504, 505 (1922) (calling res ipsa loquitur “a loose but much-used phrase of limited application”).

J ames F itzjames S tephen , A H istory of the C riminal L aw of E ngland II 94 n.1 (MacMillan & Co. 1883).

See Hall v. Chastain, 273 S.W.2d 12, 14 (Ga. 1980) (“The [ res ipsa loquitur ] rule is one of necessity in cases where there is no evidence of consequence showing negligence on the part of the defendant.”); Heffter v. Northern States Power Co., 173 Minn. 215, 218, 217 N.W. 102, 103 (Minn. 1927) (“Necessity seems the best support for the rule…. [It] has no application where all the facts and circumstances appear in evidence. Nothing is then left to inference. The necessity therefor does not exist.”); Estate of Hall v. Akron Gen. Med. Center, 125 Ohio St. 300, 927 N.E.2d 1112, 1115 (2010) ( res ipsa loquitur “originated by necessity”).

Government Ins. Office of New South Wales v. Fredrichberg, 42 A.L.J.R. 198, 202, 118 C.L.R. 403, 413 (1969).

Atlanta Coca-Cola Bottling Co. v. Burke, 109 Ga.App. 53, 66, 134 S.E.2d 909, 918 (1964) (Felton, C.J., concurring specially).

See, e.g. , Sweeney v. Erving, 228 U.S. 233, 240 (1913) (stating that, “In our opinion, res ipsa loquitur means that the facts of the occurrence warrant the inference of negligence, not that they compel such an inference”); Dover Elev. Co. v. Swann, 334 Md. 231, 236, 638 A.2d 762, 765 (1993) ( res ipsa loquitur “is applied in negligence actions as a permissible inference … [and] the burden of proving the defendant’s negligence remains upon the plaintiff.”); Dermatossian v. New York City Trans. Auth., 67 N.Y.2d 219, 226, 501 N.Y.S.2d 784, 788 (1986) (“Res ipsa loquitur … does not create a presumption in favor of the plaintiff but merely … has the effect of creating a prima facie case of negligence sufficient for submission to the jury, and the jury may – but is not required to – draw the permissible inference.”); Quinby v. Plumsteadville Family Practice, 589 Pa. 183, 907 A.2d 1061, 1076 (2006) (“ res ipsa loquitur involves a permissible inference of negligence, not a legal presumption”); Cyr v. Green Mtn. Power Corp., 145 Vt. 231, 235, 485 A.2d 1265, 1268 (1984) ( res ipsa loquitur “is not a magic doctrine that shifts the burden to the defendant. It … allows the jury a permissive inference of negligence.”). See also F leming , T he L aw of T orts , supra note 83 at 296 (noting “the predominant view” is that the maxim gives rise to a permissive inference).

E.g. , Baker v. Clark, 348 Ark. 8, 33 S.W.3d 476 (2000) (affirming that when res ipsa loquitur applies, “justice require[s] that the defendant be compelled to offer an explanation of the event or be burdened with a presumption of negligence.”); Brown v. Poway Unified Sch. Dist., 4 Cal.4th 820, 15 Cal.Rptr. 679, 682, 843 P.2d 624, 627 (1993) (“In California, the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur … [creates] a presumption affecting the burden of producing evidence.”); Kendrick v. Pippin, 252 P.3d 1052, 1061 (Colo. 2011) (stating that res ipsa loquitur “is a rule of evidence that establishes a rebuttable presumption that the defendant was negligent.”); Vernon v. Gentry, 334 S.W.2d 266, 268 (Ky. 1960) (“If the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur is to be invoked, then it must follow that the presumption of negligence immediately and inevitably arises.”); Riggsby v. Tritton, 143 Va. 903, 912, 129 S.E. 493, 496 (1925) (describing res ipsa loquitur as a rule of evidence that “amounts to a prima facie presumption of fact”).

34 Or. 282, 55 Pac. 961 (1899).

Id . at 302.

E.g. , Richardson v. Portland Trackless Car Co., 113 Or. 544, 233 P. 540 (1925); Boyd v. Portland Electric Co., 41 Or. 336, 68 P. 810 (1902).

See, e.g. , Suko v. Northwestern Ice and Cold Storage Co., 166 Or. 557, 113 P.2d 209 (1941) (holding that res ipsa loquitur raises an inference of negligence, not a presumption); Eldred v. United Amusement Co., 137 Or. 452, 2 P.2d 1114 (1931) (same). Cf . Gillilan v. Portland Crematorium Ass’n, 120 Or. 286, 292–93, 249 P. 627 (1927) (quoting with approval Sweeney v. Erving, 228 U.S. 233 (1913), which endorsed the inference theory, while also citing Coblentz v. Jaloff, 115 Or. 656, 239 P. 825 (1925), where the maxim was held to raise a presumption of negligence, and referring to “the inference or presumption of negligence”).

Ritchie v. Thomas, 190 Or. 95, 106, 224 P.2d 543 (1950).

Id . at 112, citing O.C.L.A. §2–402.

Ritchie v. Thomas , 190 Or. at 112. Accord Gow v. Multnomah Hotel, 191 Or. 45, 52, 224 P.2d 552, 555 (1950) (“The rule, when applicable, gives rise to an inference of negligence permissible but not mandatory”).

See Brown v. Poway Unified Sch. Dist., 4 Cal.4th 820, 15 Cal.Rptr. 679, 682, 843 P.2d 624, 627 (1993) (“In California, the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur is defined by statute as ‘a presumption affecting the burden of producing evidence.’ (Evid. Code, §646, subd. (b).)”).

57 N.Y. 567, 570 (1874).

Id . at 569–70.

Morejon v. Rais Constr. Co., 7 N.Y.3d 203, 851 N.E.2d 1143, 1146 (2006). See also F leming , T he L aw of T orts , supra note 83 at 295–96 (describing how conceptual confusion over the terms ‘presumption’, ‘burden of proof’, etc. has contributed significantly to their ambiguous use by courts and commentators).

233 N.Y. 285, 135 N.E. 504 (1922).

287 N.Y. 108, 38 N.E.2d 455, 462–63, 464 (1941).

Id . at 463–64.

Morejon , 851 N.E.2d at 1146–47.

In addition to Montana, Louisiana case law remains equivocal on the question of res ipsa loquitur’s procedural effect. Compare Spott v. Otis Elev. Co., 601 So.2d 1355, 1362 (La. 1992) (applying res ipsa loquitur as creating a presumption), with Linnear v. CenterPoint Energy Entrex/Reliant Energy, 945 So.2d 1, 8–9 (La.App. 2006) (holding that the “jury … decides whether to infer negligence”).

E.g. , Callahan v. Chicago, B. & Q. R.R. Co., 47 Mont. 401, 133 P. 687 (1913); Dempster v. Oregon Short Line R.R. Co., 37 Mont. 335, 96 P. 717 (1911); Ryan v. Gilmer, 2 Mont. 517, 25 Am.Rep. 744 (1877).

See, e.g. , Hickman v. First Nat’l Bank, 112 Mont. 398, 117 P.2d 275 (1941); Vonault v. O’Rourke, 97 Mont. 92, 107, 33 P.2d 535, 541 (1934).

125 Mont. 528, 531, 242 P.2d 257, 258 (1952).

Id ., 242 P.2d at 259.

Id . at 533, 242 P.2d at 259.

Id . at 536, 242 P.2d at 261.

126 Mont. 70, 244 P.2d 111 (1952).

Id . at 98, 244 P.2d at 126.

See Clark v. Norris, 226 Mont. 43, 48, 734 P.2d 182, 185 (1987) (observing that the continued “use of the terms “inference” and “presumption” interchangeably results in confusion as to their legal significance.”). Cf . Helmke v. Goff, 182 Mont. 494, 597 P.2d 1131 (1979) (noting that the Whitney Court declined to decide the question of res ipsa loquitur’s procedural effect, and concluding it too would avoid trying “to classify this jurisdiction as one following the ‘permissible inference’ theory, or the ‘rebuttable presumption’ theory”).

Compare, e.g. , Indendi v. Workman, 272 Mont. 64, 70, 899 P.2d 1085, 1089 (1995) (stating res ipsa loquitur creates “a presumption of negligence”); Rudeck v. Wright, 218 Mont. 41, 49, 709 P.2d 621, 626 (1985) (“Once the presumption of negligence arises under the res ipsa rule, the burden of rebutting the presumption shifts to the defendant.”); Jackson v. William Dingwall Co., 145 Mont. 127, 136, 399 P.2d 236, 241 (1965) (“Res ipsa loquitur is a presumption.”), with Howard v. St. James Comm. Hosp., 331 Mont. 60, 129 P.3d 126, 132 (2006) (ruling that res ipsa loquitur “permits an inference of negligence”); Romans v. Lusin, 299 Mont. 182, 997 P.2d 114, 119–20 (2000) (“The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur permits an inference of negligence…. [and] does not relieve a plaintiff of the burden of making a prima facie case that the defendant breached a duty of care.”); Dalton v. Kalispell Reg’l Hosp., 256 Mont. 243, 248, 846 P.2d 960, 963 (1993) (ruling the maxim “does not permit a presumption of negligence”).

See F leming , T he L aw of T orts , supra note 83 at 296–99 (acknowledging that courts are split on the issue, but arguing that the permissive inference standard is the better-reasoned approach).

See C lerk and L indsell , supra note 83 at ¶967; P rosser , H andbook of T he L aw of T orts , supra note 85 at §39, 228–31; Prosser, Res Ipsa Loquitur in California , supra note 75 at 217–22, 225; Prosser, The Procedural Effect of Res Ipsa Loquitur , supra note 1 at 259–62; R estatement (T hird ) of T orts , supra note 83 at §17 Comment j ; R estatement (S econd ) of T orts , supra note 83 at §328D(2) & (3).

See, e.g. , A shiq H ussain , G eneral P rinciples and C ommercial L aw of K enya 87 (East African Educ. Pub. Ltd. 1978) (stating that when the rule applies, “the burden lies on the defendant to rebut the presumption of negligence…. Where the defendant succeeds in proving that he has not been negligent…, the burden of proof reverts to the plaintiff”); M ark S hain , R es I psa L oquitur : P resumptions and B urden of P roof 62 (1945) (arguing that Scott created a “ pure presumption of negligence”); 4 W igmore , supra note 83 at §2509.

Gilbert v. Korvette’s, Inc., 457 Pa. 602, 608, 327 A.2d 94 (1974).

Byrne , 2 H&C at 728, 159 Eng.Rep. at 301.

A ristotle , R hetoric 1357b.

S teven J. B urton , A n I ntroduction to L aw and L egal reasoning 25 (Little, Brown & Co. 1985).

E dward H. L evi , A n I ntroduction to L egal R easoning 1 (Univ. of Chicago Press 1949).

See Scott , 3 H&C at 602, 159 Eng.Rep. at 668.

See R ussell , supra note 22 at 67–69.

Scott , 3 H&C at 602, 159 Eng.Rep. at 667.

P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 250, CP 5.197.

Many courts have emphasized that res ipsa loquitur calls for judgments grounded in common sense and common experience. E.g. , Maroules v. Jumbo, Inc., 452 F.3d 639, 644 (seventh Cir. 2006) (calling res ipsa loquitur “a doctrine of common sense”); Barretta v. Otis Elev. Co., 242 Conn. 169, 173, 698 A.2d 810, 812 (1997) (“rule of common sense”); Gillilan v. Portland Crematorium Ass’n, 120 Or. 286, 291, 249 P. 627 (1927) (“common experience”); Commissioner v. Corben (1938) 39 SR (NSW) 55, 63 (Jordon, CJ) (“rule of common-sense.”).

Charles Sanders Peirce, What Pragmatism Is , 15 M onist 161 (1905), CP 5.411, 5.425.

B enjamin C ardozo , T he N ature of the J udicial P rocess 23 (Yale UP 1921).

Id . at 103.

Id . at 23; B enjamin C ardozo , T he G rowth of the L aw , reprinted in S elected W ritings of B enjamin N athan C ardozo 218 (Margaret E. Hall ed., Fallon Pub. 1947) (1924).

C ardozo , T he N ature of the J udicial P rocess , supra note 172 at 23.

See id . at 66–67, 73.

See id . at 23.

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803).

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

P eirce , T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 245–46, CP 5.187–91.

Id . at 230, 245, CP 5.171, 5.189.

Id. at 230, 244–46, 247, CP 5.171, 5.186–90, 5.192.

Id . at 230, 231, CP 5.172, 5.173. Accord CP 6.530 (describing how the process of hypothesis selection depends on “intelligent guessing”); Charles S. Peirce, The Architecture of Theories , 1 M onist 161, 163–64 (1891), CP 6.7, 6.10–11 (detailing how major discoveries of science have rested on “common sense” and natural influences from which scientists could “readily guess at what the laws are,” but where such guesses were anything but “haphazard”). See also de W aal , supra note 49 at 64–65 (describing Peirce’s method of abduction as a “procedure of educated guessing”); F ann , supra note 3 at 35 (noting how Peirce sometimes “speaks of abduction as essentially a kind of guessing instinct.”).

T he 1903 H arvard L ectures , supra note 4 at 242, CP 5.181.

Id . Accord id . at 231, 5.173.

Id . at 231, 245, 247, CP 5.173–74, 5.188, 5.192.

Id . at 230, CP 5.171 (emphasis added). Accord id . at 218, CP 5.145 (“All the ideas of science come to it by the way of Abduction.”); 239 (“abduction is the only process by which a new element can be introduced into thought”).

Id . at 230, CP 5.171.

See text accompanying note 22 supra .