- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Qualitative Methods

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The word qualitative implies an emphasis on the qualities of entities and on processes and meanings that are not experimentally examined or measured [if measured at all] in terms of quantity, amount, intensity, or frequency. Qualitative researchers stress the socially constructed nature of reality, the intimate relationship between the researcher and what is studied, and the situational constraints that shape inquiry. Such researchers emphasize the value-laden nature of inquiry. They seek answers to questions that stress how social experience is created and given meaning. In contrast, quantitative studies emphasize the measurement and analysis of causal relationships between variables, not processes. Qualitative forms of inquiry are considered by many social and behavioral scientists to be as much a perspective on how to approach investigating a research problem as it is a method.

Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman. K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, eds. 3 rd edition. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005), p. 10.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Below are the three key elements that define a qualitative research study and the applied forms each take in the investigation of a research problem.

- Naturalistic -- refers to studying real-world situations as they unfold naturally; non-manipulative and non-controlling; the researcher is open to whatever emerges [i.e., there is a lack of predetermined constraints on findings].

- Emergent -- acceptance of adapting inquiry as understanding deepens and/or situations change; the researcher avoids rigid designs that eliminate responding to opportunities to pursue new paths of discovery as they emerge.

- Purposeful -- cases for study [e.g., people, organizations, communities, cultures, events, critical incidences] are selected because they are “information rich” and illuminative. That is, they offer useful manifestations of the phenomenon of interest; sampling is aimed at insight about the phenomenon, not empirical generalization derived from a sample and applied to a population.

The Collection of Data

- Data -- observations yield a detailed, "thick description" [in-depth understanding]; interviews capture direct quotations about people’s personal perspectives and lived experiences; often derived from carefully conducted case studies and review of material culture.

- Personal experience and engagement -- researcher has direct contact with and gets close to the people, situation, and phenomenon under investigation; the researcher’s personal experiences and insights are an important part of the inquiry and critical to understanding the phenomenon.

- Empathic neutrality -- an empathic stance in working with study respondents seeks vicarious understanding without judgment [neutrality] by showing openness, sensitivity, respect, awareness, and responsiveness; in observation, it means being fully present [mindfulness].

- Dynamic systems -- there is attention to process; assumes change is ongoing, whether the focus is on an individual, an organization, a community, or an entire culture, therefore, the researcher is mindful of and attentive to system and situational dynamics.

The Analysis

- Unique case orientation -- assumes that each case is special and unique; the first level of analysis is being true to, respecting, and capturing the details of the individual cases being studied; cross-case analysis follows from and depends upon the quality of individual case studies.

- Inductive analysis -- immersion in the details and specifics of the data to discover important patterns, themes, and inter-relationships; begins by exploring, then confirming findings, guided by analytical principles rather than rules.

- Holistic perspective -- the whole phenomenon under study is understood as a complex system that is more than the sum of its parts; the focus is on complex interdependencies and system dynamics that cannot be reduced in any meaningful way to linear, cause and effect relationships and/or a few discrete variables.

- Context sensitive -- places findings in a social, historical, and temporal context; researcher is careful about [even dubious of] the possibility or meaningfulness of generalizations across time and space; emphasizes careful comparative case study analysis and extrapolating patterns for possible transferability and adaptation in new settings.

- Voice, perspective, and reflexivity -- the qualitative methodologist owns and is reflective about her or his own voice and perspective; a credible voice conveys authenticity and trustworthiness; complete objectivity being impossible and pure subjectivity undermining credibility, the researcher's focus reflects a balance between understanding and depicting the world authentically in all its complexity and of being self-analytical, politically aware, and reflexive in consciousness.

Berg, Bruce Lawrence. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . 8th edition. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2012; Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000; Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman. Designing Qualitative Research . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Basic Research Design for Qualitative Studies

Unlike positivist or experimental research that utilizes a linear and one-directional sequence of design steps, there is considerable variation in how a qualitative research study is organized. In general, qualitative researchers attempt to describe and interpret human behavior based primarily on the words of selected individuals [a.k.a., “informants” or “respondents”] and/or through the interpretation of their material culture or occupied space. There is a reflexive process underpinning every stage of a qualitative study to ensure that researcher biases, presuppositions, and interpretations are clearly evident, thus ensuring that the reader is better able to interpret the overall validity of the research. According to Maxwell (2009), there are five, not necessarily ordered or sequential, components in qualitative research designs. How they are presented depends upon the research philosophy and theoretical framework of the study, the methods chosen, and the general assumptions underpinning the study. Goals Describe the central research problem being addressed but avoid describing any anticipated outcomes. Questions to ask yourself are: Why is your study worth doing? What issues do you want to clarify, and what practices and policies do you want it to influence? Why do you want to conduct this study, and why should the reader care about the results? Conceptual Framework Questions to ask yourself are: What do you think is going on with the issues, settings, or people you plan to study? What theories, beliefs, and prior research findings will guide or inform your research, and what literature, preliminary studies, and personal experiences will you draw upon for understanding the people or issues you are studying? Note to not only report the results of other studies in your review of the literature, but note the methods used as well. If appropriate, describe why earlier studies using quantitative methods were inadequate in addressing the research problem. Research Questions Usually there is a research problem that frames your qualitative study and that influences your decision about what methods to use, but qualitative designs generally lack an accompanying hypothesis or set of assumptions because the findings are emergent and unpredictable. In this context, more specific research questions are generally the result of an interactive design process rather than the starting point for that process. Questions to ask yourself are: What do you specifically want to learn or understand by conducting this study? What do you not know about the things you are studying that you want to learn? What questions will your research attempt to answer, and how are these questions related to one another? Methods Structured approaches to applying a method or methods to your study help to ensure that there is comparability of data across sources and researchers and, thus, they can be useful in answering questions that deal with differences between phenomena and the explanation for these differences [variance questions]. An unstructured approach allows the researcher to focus on the particular phenomena studied. This facilitates an understanding of the processes that led to specific outcomes, trading generalizability and comparability for internal validity and contextual and evaluative understanding. Questions to ask yourself are: What will you actually do in conducting this study? What approaches and techniques will you use to collect and analyze your data, and how do these constitute an integrated strategy? Validity In contrast to quantitative studies where the goal is to design, in advance, “controls” such as formal comparisons, sampling strategies, or statistical manipulations to address anticipated and unanticipated threats to validity, qualitative researchers must attempt to rule out most threats to validity after the research has begun by relying on evidence collected during the research process itself in order to effectively argue that any alternative explanations for a phenomenon are implausible. Questions to ask yourself are: How might your results and conclusions be wrong? What are the plausible alternative interpretations and validity threats to these, and how will you deal with these? How can the data that you have, or that you could potentially collect, support or challenge your ideas about what’s going on? Why should we believe your results? Conclusion Although Maxwell does not mention a conclusion as one of the components of a qualitative research design, you should formally conclude your study. Briefly reiterate the goals of your study and the ways in which your research addressed them. Discuss the benefits of your study and how stakeholders can use your results. Also, note the limitations of your study and, if appropriate, place them in the context of areas in need of further research.

Chenail, Ronald J. Introduction to Qualitative Research Design. Nova Southeastern University; Heath, A. W. The Proposal in Qualitative Research. The Qualitative Report 3 (March 1997); Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman. Designing Qualitative Research . 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999; Maxwell, Joseph A. "Designing a Qualitative Study." In The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods . Leonard Bickman and Debra J. Rog, eds. 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2009), p. 214-253; Qualitative Research Methods. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Yin, Robert K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish . 2nd edition. New York: Guilford, 2015.

Strengths of Using Qualitative Methods

The advantage of using qualitative methods is that they generate rich, detailed data that leave the participants' perspectives intact and provide multiple contexts for understanding the phenomenon under study. In this way, qualitative research can be used to vividly demonstrate phenomena or to conduct cross-case comparisons and analysis of individuals or groups.

Among the specific strengths of using qualitative methods to study social science research problems is the ability to:

- Obtain a more realistic view of the lived world that cannot be understood or experienced in numerical data and statistical analysis;

- Provide the researcher with the perspective of the participants of the study through immersion in a culture or situation and as a result of direct interaction with them;

- Allow the researcher to describe existing phenomena and current situations;

- Develop flexible ways to perform data collection, subsequent analysis, and interpretation of collected information;

- Yield results that can be helpful in pioneering new ways of understanding;

- Respond to changes that occur while conducting the study ]e.g., extended fieldwork or observation] and offer the flexibility to shift the focus of the research as a result;

- Provide a holistic view of the phenomena under investigation;

- Respond to local situations, conditions, and needs of participants;

- Interact with the research subjects in their own language and on their own terms; and,

- Create a descriptive capability based on primary and unstructured data.

Anderson, Claire. “Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 74 (2010): 1-7; Denzin, Norman. K. and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Handbook of Qualitative Research . 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Limitations of Using Qualitative Methods

It is very much true that most of the limitations you find in using qualitative research techniques also reflect their inherent strengths . For example, small sample sizes help you investigate research problems in a comprehensive and in-depth manner. However, small sample sizes undermine opportunities to draw useful generalizations from, or to make broad policy recommendations based upon, the findings. Additionally, as the primary instrument of investigation, qualitative researchers are often embedded in the cultures and experiences of others. However, cultural embeddedness increases the opportunity for bias generated from conscious or unconscious assumptions about the study setting to enter into how data is gathered, interpreted, and reported.

Some specific limitations associated with using qualitative methods to study research problems in the social sciences include the following:

- Drifting away from the original objectives of the study in response to the changing nature of the context under which the research is conducted;

- Arriving at different conclusions based on the same information depending on the personal characteristics of the researcher;

- Replication of a study is very difficult;

- Research using human subjects increases the chance of ethical dilemmas that undermine the overall validity of the study;

- An inability to investigate causality between different research phenomena;

- Difficulty in explaining differences in the quality and quantity of information obtained from different respondents and arriving at different, non-consistent conclusions;

- Data gathering and analysis is often time consuming and/or expensive;

- Requires a high level of experience from the researcher to obtain the targeted information from the respondent;

- May lack consistency and reliability because the researcher can employ different probing techniques and the respondent can choose to tell some particular stories and ignore others; and,

- Generation of a significant amount of data that cannot be randomized into manageable parts for analysis.

Research Tip

Human Subject Research and Institutional Review Board Approval

Almost every socio-behavioral study requires you to submit your proposed research plan to an Institutional Review Board. The role of the Board is to evaluate your research proposal and determine whether it will be conducted ethically and under the regulations, institutional polices, and Code of Ethics set forth by the university. The purpose of the review is to protect the rights and welfare of individuals participating in your study. The review is intended to ensure equitable selection of respondents, that you have met the requirements for obtaining informed consent , that there is clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university [read: no lawsuits!], and that privacy and confidentiality are maintained throughout the research process and beyond. Go to the USC IRB website for detailed information and templates of forms you need to submit before you can proceed. If you are unsure whether your study is subject to IRB review, consult with your professor or academic advisor.

Chenail, Ronald J. Introduction to Qualitative Research Design. Nova Southeastern University; Labaree, Robert V. "Working Successfully with Your Institutional Review Board: Practical Advice for Academic Librarians." College and Research Libraries News 71 (April 2010): 190-193.

Another Research Tip

Finding Examples of How to Apply Different Types of Research Methods

SAGE publications is a major publisher of studies about how to design and conduct research in the social and behavioral sciences. Their SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases database includes contents from books, articles, encyclopedias, handbooks, and videos covering social science research design and methods including the complete Little Green Book Series of Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences and the Little Blue Book Series of Qualitative Research techniques. The database also includes case studies outlining the research methods used in real research projects. This is an excellent source for finding definitions of key terms and descriptions of research design and practice, techniques of data gathering, analysis, and reporting, and information about theories of research [e.g., grounded theory]. The database covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods as well as mixed methods approaches to conducting research.

SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases

NOTE : For a list of online communities, research centers, indispensable learning resources, and personal websites of leading qualitative researchers, GO HERE .

For a list of scholarly journals devoted to the study and application of qualitative research methods, GO HERE .

- << Previous: 6. The Methodology

- Next: Quantitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Sep 17, 2024 10:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

- Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

a method of research that produces descriptive (non-numerical) data, such as observations of behavior or personal accounts of experiences. The goal of gathering this qualitative data is to examine how individuals can perceive the world from different vantage points. A variety of techniques are subsumed under qualitative research, including content analyses of narratives, in-depth interviews, focus groups, participant observation, and case studies, often conducted in naturalistic settings.

SAGE Research Methods Videos

What questions does qualitative research ask.

A variety of academics discuss the meaning of qualitative research and content analysis. Both hypothetical and actual research projects are used to illustrate concepts.

What makes a good qualitative researcher?

Professor John Creswell analyzes the characteristics of qualitative research and the qualitative researcher. He explains that good qualitative researchers tend to look at the big picture, notice details, and write a lot. He discusses how these characteristics tie into qualitative research.

This is just one segment in a series about qualitative research. You can find the rest of the series in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

- << Previous: Quantitative Research Methods

- Next: Mixed Methods Study >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:51 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Qualitative Research? Methods, Types, Approaches and Examples

Qualitative research is a type of method that researchers use depending on their study requirements. Research can be conducted using several methods, but before starting the process, researchers should understand the different methods available to decide the best one for their study type. The type of research method needed depends on a few important criteria, such as the research question, study type, time, costs, data availability, and availability of respondents. The two main types of methods are qualitative research and quantitative research. Sometimes, researchers may find it difficult to decide which type of method is most suitable for their study. Keeping in mind a simple rule of thumb could help you make the correct decision. Quantitative research should be used to validate or test a theory or hypothesis and qualitative research should be used to understand a subject or event or identify reasons for observed patterns.

Qualitative research methods are based on principles of social sciences from several disciplines like psychology, sociology, and anthropology. In this method, researchers try to understand the feelings and motivation of their respondents, which would have prompted them to select or give a particular response to a question. Here are two qualitative research examples :

- Two brands (A & B) of the same medicine are available at a pharmacy. However, Brand A is more popular and has higher sales. In qualitative research , the interviewers would ideally visit a few stores in different areas and ask customers their reason for selecting either brand. Respondents may have different reasons that motivate them to select one brand over the other, such as brand loyalty, cost, feedback from friends, doctor’s suggestion, etc. Once the reasons are known, companies could then address challenges in that specific area to increase their product’s sales.

- A company organizes a focus group meeting with a random sample of its product’s consumers to understand their opinion on a new product being launched.

Table of Contents

What is qualitative research? 1

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data. The findings of qualitative research are expressed in words and help in understanding individuals’ subjective perceptions about an event, condition, or subject. This type of research is exploratory and is used to generate hypotheses or theories from data. Qualitative data are usually in the form of text, videos, photographs, and audio recordings. There are multiple qualitative research types , which will be discussed later.

Qualitative research methods 2

Researchers can choose from several qualitative research methods depending on the study type, research question, the researcher’s role, data to be collected, etc.

The following table lists the common qualitative research approaches with their purpose and examples, although there may be an overlap between some.

| Narrative | Explore the experiences of individuals and tell a story to give insight into human lives and behaviors. Narratives can be obtained from journals, letters, conversations, autobiographies, interviews, etc. | A researcher collecting information to create a biography using old documents, interviews, etc. |

| Phenomenology | Explain life experiences or phenomena, focusing on people’s subjective experiences and interpretations of the world. | Researchers exploring the experiences of family members of an individual undergoing a major surgery. |

| Grounded theory | Investigate process, actions, and interactions, and based on this grounded or empirical data a theory is developed. Unlike experimental research, this method doesn’t require a hypothesis theory to begin with. | A company with a high attrition rate and no prior data may use this method to understand the reasons for which employees leave. |

| Ethnography | Describe an ethnic, cultural, or social group by observation in their naturally occurring environment. | A researcher studying medical personnel in the immediate care division of a hospital to understand the culture and staff behaviors during high capacity. |

| Case study | In-depth analysis of complex issues in real-life settings, mostly used in business, law, and policymaking. Learnings from case studies can be implemented in other similar contexts. | A case study about how a particular company turned around its product sales and the marketing strategies they used could help implement similar methods in other companies. |

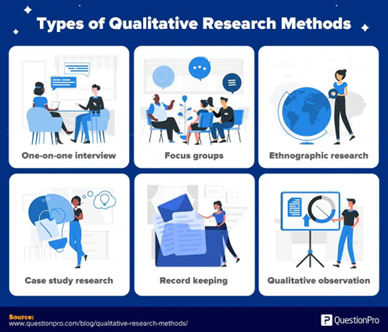

Types of qualitative research 3,4

The data collection methods in qualitative research are designed to assess and understand the perceptions, motivations, and feelings of the respondents about the subject being studied. The different qualitative research types include the following:

- In-depth or one-on-one interviews : This is one of the most common qualitative research methods and helps the interviewers understand a respondent’s subjective opinion and experience pertaining to a specific topic or event. These interviews are usually conversational and encourage the respondents to express their opinions freely. Semi-structured interviews, which have open-ended questions (where the respondents can answer more than just “yes” or “no”), are commonly used. Such interviews can be either face-to-face or telephonic, and the duration can vary depending on the subject or the interviewer. Asking the right questions is essential in this method so that the interview can be led in the suitable direction. Face-to-face interviews also help interviewers observe the respondents’ body language, which could help in confirming whether the responses match.

- Document study/Literature review/Record keeping : Researchers’ review of already existing written materials such as archives, annual reports, research articles, guidelines, policy documents, etc.

- Focus groups : Usually include a small sample of about 6-10 people and a moderator, to understand the participants’ opinion on a given topic. Focus groups ensure constructive discussions to understand the why, what, and, how about the topic. These group meetings need not always be in-person. In recent times, online meetings are also encouraged, and online surveys could also be administered with the option to “write” subjective answers as well. However, this method is expensive and is mostly used for new products and ideas.

- Qualitative observation : In this method, researchers collect data using their five senses—sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing. This method doesn’t include any measurements but only the subjective observation. For example, “The dessert served at the bakery was creamy with sweet buttercream frosting”; this observation is based on the taste perception.

Qualitative research : Data collection and analysis

- Qualitative data collection is the process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research.

- The data collected are usually non-numeric and subjective and could be recorded in various methods, for instance, in case of one-to-one interviews, the responses may be recorded using handwritten notes, and audio and video recordings, depending on the interviewer and the setting or duration.

- Once the data are collected, they should be transcribed into meaningful or useful interpretations. An experienced researcher could take about 8-10 hours to transcribe an interview’s recordings. All such notes and recordings should be maintained properly for later reference.

- Some interviewers make use of “field notes.” These are not exactly the respondents’ answers but rather some observations the interviewer may have made while asking questions and may include non-verbal cues or any information about the setting or the environment. These notes are usually informal and help verify respondents’ answers.

2. Qualitative data analysis

- This process involves analyzing all the data obtained from the qualitative research methods in the form of text (notes), audio-video recordings, and pictures.

- Text analysis is a common form of qualitative data analysis in which researchers examine the social lives of the participants and analyze their words, actions, etc. in specific contexts. Social media platforms are now playing an important role in this method with researchers analyzing all information shared online.

There are usually five steps in the qualitative data analysis process: 5

- Prepare and organize the data

- Transcribe interviews

- Collect and document field notes and other material

- Review and explore the data

- Examine the data for patterns or important observations

- Develop a data coding system

- Create codes to categorize and connect the data

- Assign these codes to the data or responses

- Review the codes

- Identify recurring themes, opinions, patterns, etc.

- Present the findings

- Use the best possible method to present your observations

The following table 6 lists some common qualitative data analysis methods used by companies to make important decisions, with examples and when to use each. The methods may be similar and can overlap.

| Content analysis | To identify patterns in text, by grouping content into words, concepts, and themes; that is, determine presence of certain words or themes in some text | Researchers examining the language used in a journal article to search for bias |

| Narrative analysis | To understand people’s perspectives on specific issues. Focuses on people’s stories and the language used to tell these stories | A researcher conducting one or several in-depth interviews with an individual over a long period |

| Discourse analysis | To understand political, cultural, and power dynamics in specific contexts; that is, how people express themselves in different social contexts | A researcher studying a politician’s speeches across multiple contexts, such as audience, region, political history, etc. |

| Thematic analysis | To interpret the meaning behind the words used by people. This is done by identifying repetitive patterns or themes by reading through a dataset | Researcher analyzing raw data to explore the impact of high-stakes examinations on students and parents |

Characteristics of qualitative research methods 4

- Unstructured raw data : Qualitative research methods use unstructured, non-numerical data , which are analyzed to generate subjective conclusions about specific subjects, usually presented descriptively, instead of using statistical data.

- Site-specific data collection : In qualitative research methods , data are collected at specific areas where the respondents or researchers are either facing a challenge or have a need to explore. The process is conducted in a real-world setting and participants do not need to leave their original geographical setting to be able to participate.

- Researchers’ importance : Researchers play an instrumental role because, in qualitative research , communication with respondents is an essential part of data collection and analysis. In addition, researchers need to rely on their own observation and listening skills during an interaction and use and interpret that data appropriately.

- Multiple methods : Researchers collect data through various methods, as listed earlier, instead of relying on a single source. Although there may be some overlap between the qualitative research methods , each method has its own significance.

- Solving complex issues : These methods help in breaking down complex problems into more useful and interpretable inferences, which can be easily understood by everyone.

- Unbiased responses : Qualitative research methods rely on open communication where the participants are allowed to freely express their views. In such cases, the participants trust the interviewer, resulting in unbiased and truthful responses.

- Flexible : The qualitative research method can be changed at any stage of the research. The data analysis is not confined to being done at the end of the research but can be done in tandem with data collection. Consequently, based on preliminary analysis and new ideas, researchers have the liberty to change the method to suit their objective.

When to use qualitative research 4

The following points will give you an idea about when to use qualitative research .

- When the objective of a research study is to understand behaviors and patterns of respondents, then qualitative research is the most suitable method because it gives a clear insight into the reasons for the occurrence of an event.

- A few use cases for qualitative research methods include:

- New product development or idea generation

- Strengthening a product’s marketing strategy

- Conducting a SWOT analysis of product or services portfolios to help take important strategic decisions

- Understanding purchasing behavior of consumers

- Understanding reactions of target market to ad campaigns

- Understanding market demographics and conducting competitor analysis

- Understanding the effectiveness of a new treatment method in a particular section of society

A qualitative research method case study to understand when to use qualitative research 7

Context : A high school in the US underwent a turnaround or conservatorship process and consequently experienced a below average teacher retention rate. Researchers conducted qualitative research to understand teachers’ experiences and perceptions of how the turnaround may have influenced the teachers’ morale and how this, in turn, would have affected teachers’ retention.

Method : Purposive sampling was used to select eight teachers who were employed with the school before the conservatorship process and who were subsequently retained. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with these teachers. The questions addressed teachers’ perspectives of morale and their views on the conservatorship process.

Results : The study generated six factors that may have been influencing teachers’ perspectives: powerlessness, excessive visitations, loss of confidence, ineffective instructional practices, stress and burnout, and ineffective professional development opportunities. Based on these factors, four recommendations were made to increase teacher retention by boosting their morale.

Advantages of qualitative research 1

- Reflects real-world settings , and therefore allows for ambiguities in data, as well as the flexibility to change the method based on new developments.

- Helps in understanding the feelings or beliefs of the respondents rather than relying only on quantitative data.

- Uses a descriptive and narrative style of presentation, which may be easier to understand for people from all backgrounds.

- Some topics involving sensitive or controversial content could be difficult to quantify and so qualitative research helps in analyzing such content.

- The availability of multiple data sources and research methods helps give a holistic picture.

- There’s more involvement of participants, which gives them an assurance that their opinion matters, possibly leading to unbiased responses.

Disadvantages of qualitative research 1

- Large-scale data sets cannot be included because of time and cost constraints.

- Ensuring validity and reliability may be a challenge because of the subjective nature of the data, so drawing definite conclusions could be difficult.

- Replication by other researchers may be difficult for the same contexts or situations.

- Generalization to a wider context or to other populations or settings is not possible.

- Data collection and analysis may be time consuming.

- Researcher’s interpretation may alter the results causing an unintended bias.

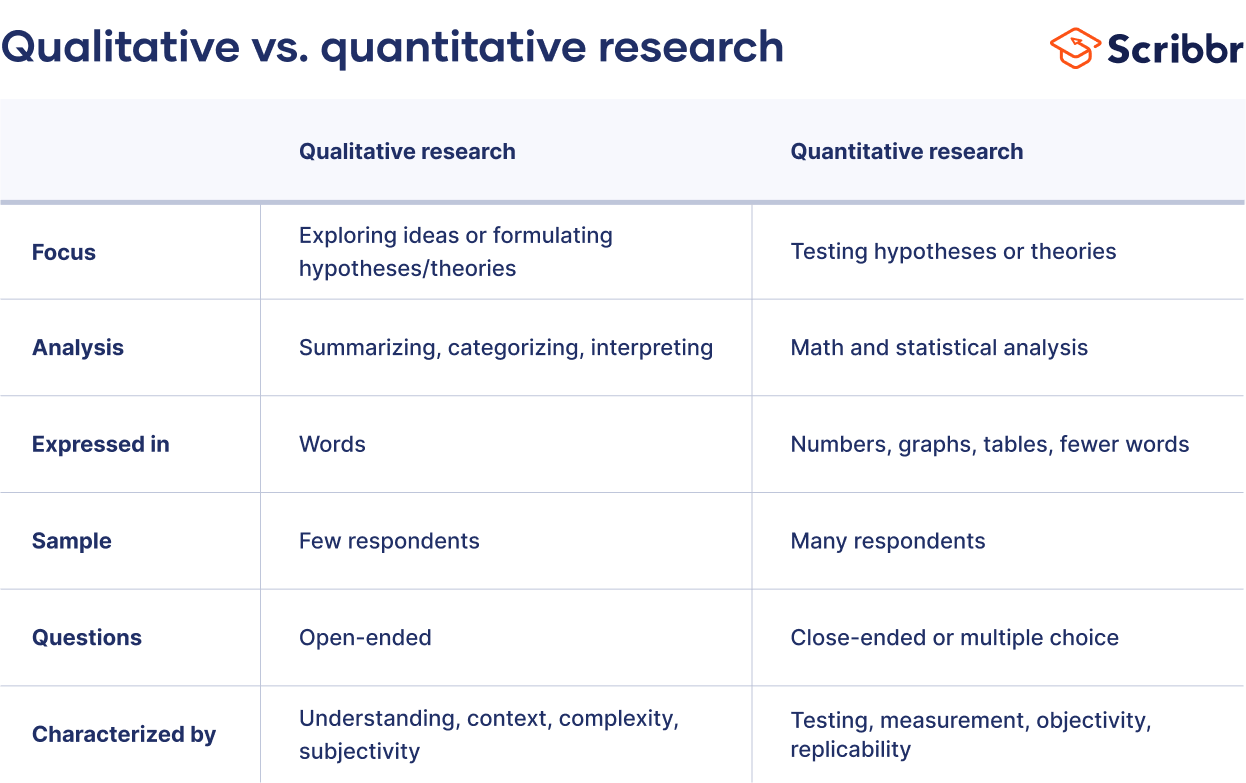

Differences between qualitative research and quantitative research 1

| Purpose and design | Explore ideas, formulate hypotheses; more subjective | Test theories and hypotheses, discover causal relationships; measurable and more structured |

| Data collection method | Semi-structured interviews/surveys with open-ended questions, document study/literature reviews, focus groups, case study research, ethnography | Experiments, controlled observations, questionnaires and surveys with a rating scale or closed-ended questions. The methods can be experimental, quasi-experimental, descriptive, or correlational. |

| Data analysis | Content analysis (determine presence of certain words/concepts in texts), grounded theory (hypothesis creation by data collection and analysis), thematic analysis (identify important themes/patterns in data and use these to address an issue) | Statistical analysis using applications such as Excel, SPSS, R |

| Sample size | Small | Large |

| Example | A company organizing focus groups or one-to-one interviews to understand customers’ (subjective) opinions about a specific product, based on which the company can modify their marketing strategy | Customer satisfaction surveys sent out by companies. Customers are asked to rate their experience on a rating scale of 1 to 5 |

Frequently asked questions on qualitative research

Q: how do i know if qualitative research is appropriate for my study .

A: Here’s a simple checklist you could use:

- Not much is known about the subject being studied.

- There is a need to understand or simplify a complex problem or situation.

- Participants’ experiences/beliefs/feelings are required for analysis.

- There’s no existing hypothesis to begin with, rather a theory would need to be created after analysis.

- You need to gather in-depth understanding of an event or subject, which may not need to be supported by numeric data.

Q: How do I ensure the reliability and validity of my qualitative research findings?

A: To ensure the validity of your qualitative research findings you should explicitly state your objective and describe clearly why you have interpreted the data in a particular way. Another method could be to connect your data in different ways or from different perspectives to see if you reach a similar, unbiased conclusion.

To ensure reliability, always create an audit trail of your qualitative research by describing your steps and reasons for every interpretation, so that if required, another researcher could trace your steps to corroborate your (or their own) findings. In addition, always look for patterns or consistencies in the data collected through different methods.

Q: Are there any sampling strategies or techniques for qualitative research ?

A: Yes, the following are few common sampling strategies used in qualitative research :

1. Convenience sampling

Selects participants who are most easily accessible to researchers due to geographical proximity, availability at a particular time, etc.

2. Purposive sampling

Participants are grouped according to predefined criteria based on a specific research question. Sample sizes are often determined based on theoretical saturation (when new data no longer provide additional insights).

3. Snowball sampling

Already selected participants use their social networks to refer the researcher to other potential participants.

4. Quota sampling

While designing the study, the researchers decide how many people with which characteristics to include as participants. The characteristics help in choosing people most likely to provide insights into the subject.

Q: What ethical standards need to be followed with qualitative research ?

A: The following ethical standards should be considered in qualitative research:

- Anonymity : The participants should never be identified in the study and researchers should ensure that no identifying information is mentioned even indirectly.

- Confidentiality : To protect participants’ confidentiality, ensure that all related documents, transcripts, notes are stored safely.

- Informed consent : Researchers should clearly communicate the objective of the study and how the participants’ responses will be used prior to engaging with the participants.

Q: How do I address bias in my qualitative research ?

A: You could use the following points to ensure an unbiased approach to your qualitative research :

- Check your interpretations of the findings with others’ interpretations to identify consistencies.

- If possible, you could ask your participants if your interpretations convey their beliefs to a significant extent.

- Data triangulation is a way of using multiple data sources to see if all methods consistently support your interpretations.

- Contemplate other possible explanations for your findings or interpretations and try ruling them out if possible.

- Conduct a peer review of your findings to identify any gaps that may not have been visible to you.

- Frame context-appropriate questions to ensure there is no researcher or participant bias.

We hope this article has given you answers to the question “ what is qualitative research ” and given you an in-depth understanding of the various aspects of qualitative research , including the definition, types, and approaches, when to use this method, and advantages and disadvantages, so that the next time you undertake a study you would know which type of research design to adopt.

References:

- McLeod, S. A. Qualitative vs. quantitative research. Simply Psychology [Accessed January 17, 2023]. www.simplypsychology.org/qualitative-quantitative.html

- Omniconvert website [Accessed January 18, 2023]. https://www.omniconvert.com/blog/qualitative-research-definition-methodology-limitation-examples/

- Busetto L., Wick W., Gumbinger C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice [Accessed January 19, 2023] https://neurolrespract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42466-020-00059

- QuestionPro website. Qualitative research methods: Types & examples [Accessed January 16, 2023]. https://www.questionpro.com/blog/qualitative-research-methods/

- Campuslabs website. How to analyze qualitative data [Accessed January 18, 2023]. https://baselinesupport.campuslabs.com/hc/en-us/articles/204305675-How-to-analyze-qualitative-data

- Thematic website. Qualitative data analysis: Step-by-guide [Accessed January 20, 2023]. https://getthematic.com/insights/qualitative-data-analysis/

- Lane L. J., Jones D., Penny G. R. Qualitative case study of teachers’ morale in a turnaround school. Research in Higher Education Journal . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1233111.pdf

- Meetingsnet website. 7 FAQs about qualitative research and CME [Accessed January 21, 2023]. https://www.meetingsnet.com/cme-design/7-faqs-about-qualitative-research-and-cme

- Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Khoury College of Computer Sciences. Northeastern University. https://course.ccs.neu.edu/is4800sp12/resources/qualmethods.pdf

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Editage Plus: Tools and Pricing

Editage Review: Editage Services, Pricing, Editage Plus, and Editage Insights

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 30 January 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analysing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, and history.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organisation?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography, action research, phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasise different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organisations to understand their cultures. | |

| Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. | |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves ‘instruments’ in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analysing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organise your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorise your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analysing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasise different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorise common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analysing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analysing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalisability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalisable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labour-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organisation to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, January 30). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/introduction-to-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Qualitative study.

Steven Tenny ; Janelle M. Brannan ; Grace D. Brannan .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. [1] Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." [2] Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. [2] One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. [3] Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. [4] While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design originates in social and cultural anthropology and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. [2] Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. [2] That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc, through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded theory

Grounded Theory is the "generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior." [5] Unlike quantitative research, which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and, therefore, lends itself to research aimed at social interactions or experiences. [3] [2] In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the "study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular.” [5] At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are pretty similar, but the differences can be seen upon careful examination. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the individual's perspective. [2] Phenomenology is essentially looking into the "lived experiences" of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way from their perspective. Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources. In contrast, Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomenon from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called a "thick" or "rich" description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of "thick" description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, hoping to create a cohesive story or narrative. [2] While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be "opportunities for innovation." [2]

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards underpinning different research approaches. Essentially, research paradigms are the "worldviews" that inform research. [4] It is valuable for qualitative and quantitative researchers to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontologies and epistemologies. Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality,” whereas epistemology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of knowledge" that inform researchers' work. [2] It is essential to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a complete understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, researchers must understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist versus postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we must discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social and natural sciences. [4] Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in their research. It stems from positivist ontology, that there is an objective reality that exists that is wholly independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained, but could be approximated. [4] Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world,” and therefore, postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. [4] An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are also constructivist, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but instead that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. "Constructivism contends that individuals' views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality.” [6] constructivist thought focuses on how "reality" is not a fixed certainty and how experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike positivist views, that there is not necessarily an "objective"reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and our world are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.” [4]

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have. It can even change the role of the researchers. [2] For example, is the researcher an "objective" observer, such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the study undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research and reflect on their positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection: [7]

- Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale for being the most informative.

- Criterion sampling selection based on pre-identified factors.

- Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

- Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

- Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

- Typical case sampling selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative research uses several techniques, including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic, and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one-on-one and appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be participant-observers to share the experiences of the subject or non-participants or detached observers.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or the participants' environment, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed, which may then be coded manually or using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo. [8] [9] [10]

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. [11] Results could also be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

The healthcare team can use two reporting standards to standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. [12] The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a more comprehensive range of qualitative research. [13]

Applications

Many times, a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis, which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data to better understand what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative techniques can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research, researchers can explore poorly studied subjects with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual actions, and social science research.

An excellent qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected that will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because, often, the information sought is not well categorized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of why teens start to smoke and factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered "cool," and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current nonsmokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the survey results to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the primary factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the primary factor that contributed to teens starting smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on keeping teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly in the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure to smoke. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and sees that the smokers tend to hang out in a shady, overgrown area of the park. The researcher notes that smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park, where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk populations their perceptions of the changes and what factors are still at play, and quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community and the incidence of new teen smokers, among others. [14] [15]

Qualitative research functions as a standalone research design or combined with quantitative research to enhance our understanding of the world. Qualitative research uses techniques including structured and unstructured interviews, focus groups, and participant observation not only to help generate hypotheses that can be more rigorously tested with quantitative research but also to help researchers delve deeper into the quantitative research numbers, understand what they mean, and understand what the implications are. Qualitative research allows researchers to understand what is going on, especially when things are not easily categorized. [16]

- Issues of Concern

As discussed in the sections above, quantitative and qualitative work differ in many ways, including the evaluation criteria. There are four well-established criteria for evaluating quantitative data: internal validity, external validity, reliability, and objectivity. Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability are the correlating concepts in qualitative research. [4] [11] The corresponding quantitative and qualitative concepts can be seen below, with the quantitative concept on the left and the qualitative concept on the right:

- Internal validity: Credibility

- External validity: Transferability

- Reliability: Dependability

- Objectivity: Confirmability

In conducting qualitative research, ensuring these concepts are satisfied and well thought out can mitigate potential issues from arising. For example, just as a researcher will ensure that their quantitative study is internally valid, qualitative researchers should ensure that their work has credibility.

Indicators such as triangulation and peer examination can help evaluate the credibility of qualitative work.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple data collection methods to increase the likelihood of getting a reliable and accurate result. In our above magic example, the result would be more reliable if we interviewed the magician, backstage hand, and the person who "vanished." In qualitative research, triangulation can include telephone surveys, in-person surveys, focus groups, and interviews and surveying an adequate cross-section of the target demographic.

- Peer examination: A peer can review results to ensure the data is consistent with the findings.

A "thick" or "rich" description can be used to evaluate the transferability of qualitative research, whereas an indicator such as an audit trail might help evaluate the dependability and confirmability.

- Thick or rich description: This is a detailed and thorough description of details, the setting, and quotes from participants in the research. [5] Thick descriptions will include a detailed explanation of how the study was conducted. Thick descriptions are detailed enough to allow readers to draw conclusions and interpret the data, which can help with transferability and replicability.

- Audit trail: An audit trail provides a documented set of steps of how the participants were selected and the data was collected. The original information records should also be kept (eg, surveys, notes, recordings).

One issue of concern that qualitative researchers should consider is observation bias. Here are a few examples:

- Hawthorne effect: The effect is the change in participant behavior when they know they are being observed. Suppose a researcher wanted to identify factors that contribute to employee theft and tell the employees they will watch them to see what factors affect employee theft. In that case, one would suspect employee behavior would change when they know they are being protected.

- Observer-expectancy effect: Some participants change their behavior or responses to satisfy the researcher's desired effect. This happens unconsciously for the participant, so it is essential to eliminate or limit the transmission of the researcher's views.

- Artificial scenario effect: Some qualitative research occurs in contrived scenarios with preset goals. In such situations, the information may not be accurate because of the artificial nature of the scenario. The preset goals may limit the qualitative information obtained.

- Clinical Significance