Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Mechanical bridge to recovery in pheochromocytoma myocarditis

Professor Stephen Westaby and colleagues describe the case of a patient who presented with cardiogenic shock that swiftly deteriorated to severe heart failure. CT revealed a large adrenal tumor that was subsequently indentified as pheochromocytoma. After the tumor was removed, the patient underwent left ventricular assist device implantation as a bridge to left ventricular recovery.

- Stephen Westaby

- Ashwin Shahir

- Oliver Ormerod

Cardiac sympathetic activity in stress-induced (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy

Prasad and colleagues report on the novel technique of 11 C hydroxyephedrine PET imaging for the measurement of myocardial sympathetic neuronal activity in a patient with stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy.

- Abhiram Prasad

- Malini Madhavan

- Panithaya Chareonthaitawee

Ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm presenting as ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Lindsay et al . present an interesting case of a patient with a ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm. The authors recommend the early use of imaging modalities for prompt diagnosis, as anticoagulation therapy might have detrimental effects on patient outcome. Reparative surgery is safe and successful in almost all noninfective cases.

- Alistair C. Lindsay

- Balakrishnan Mahesh

- Miles C. D. Dalby

First case of stenting of a vulnerable plaque in the SECRITT I trial—the dawn of a new era?

Ramcharitar et al . describe the first case treated in the SECRITT I trial. The 63-year-old man presented with class II anginal symptoms and was diagnosed as having a culprit lesion in the left circumflex artery and a vulnerable plaque in the left anterior descending artery. The vulnerable plaque was treated with a self-expanding stent tailored to shield this type of plaque.

- Steve Ramcharitar

- Nieves Gonzalo

- Patrick W. Serruys

Provokable left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in a patient without hypertrophy

Dr Pasquale and colleagues demonstrate that dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction was the cause of exertional chest pain and dyspnea in a patient with no evidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or ischemic heart disease.

- Ferdinando Pasquale

- Maria Teresa Tomé-Esteban

- Perry Elliott

Emergency surgical treatment of advanced endomyocardial fibrosis in Mozambique

- Ana Olga Mocumbi

- Carla Carrilho

- Magdi H Yacoub

Antiphospholipid antibodies from a patient with primary antiphospholipid syndrome enhance experimental atherosclerosis

In this month's Case Study, George and colleagues present a case of antiphospholipid syndrome. The IgG anti-β 2 GPI antibodies isolated from this patient enhanced experimental atherosclerosis and attenuated plaque stability in apolipoprotein-E-knockout mice.

- Arnon Adler

- Jacob George

A case of coronary artery fistula visualized by 64-slice multidetector CT

In this month's Case Study, Versaci and colleagues present a case of congenital coronary artery fistula originating from the left anterior coronary artery and draining into right ventricle, in conjunction with an aneurysm of the left anterior descending artery. The high risk of rupture lead the authors to close the fistula surgically using normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass.

- Francesco Versaci

- Costantino Del Giudice

- Luigi Chiariello

Tunneled left anterior descending artery in a child with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

The authors highlight the benefits of using a beating-heart technique during surgical correction of myocardial bridging in this 10-year-old patient with nonobstructive hypertrophic.cardiomyopathy.

- Iacopo Olivotto

- Franco Cecchi

Cardiac amyloidosis, a monoclonal gammopathy and a potentially misleading mutation

Treatment of patients with amyloidosis is centered on reducing the supply of the respective amyloid fibril precursor protein. This Case Study describes a patient with cardiac acquired monoclonal immunoglobulin-light-chain amyloidosis, who also has an incidental amyloidogenic transthyretin Val122Ile mutation, and illustrates the crucial need to characterize the presence, extent and—most importantly—fibril type of amyloid deposits in patients with amyloidosis.

- Ashutosh D Wechalekar

- Helen J Lachmann

Acute hemodynamic changes in percutaneous transluminal septal coil embolization for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

Ramcharitar and colleagues present an interesting case of a patient with drug-refractory hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and NYHA class II–III heart failure who was treated with septal coil embolization. This article demonstrates, for the first time, the acute changes in hemodynamics that occur following septal coil embolization, and shows that this treatment is a viable alternative to percutaneous coronary intervention.

- Emanuele Meliga

- Patrick W Serruys

A case of cardiogenic shock caused by capecitabine treatment

Several chemotherapeutic agents, including newer drugs, can have toxic cardiac effects. In this month's Case Study, To and colleagues present their patient who had capecitabine-induced cardiogenic shock. They examine the best course of action for this serious complication of chemotherapy.

- Andrew CY To

- Khang Li Looi

- Harvey D White

A case of permanent pacemaker lead infection

Device infection is devastating in individuals with permanent pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. In this month's Case Study, Simon and colleagues present a patient who had a duel pacemaker lead infection and tricuspid valve endocarditis. They examine the best course of action for this serious complication.

- Caterina Simon

- Fabio Capuano

- Riccardo Sinatra

Dilated cardiomyopathy: an unusual complication of clozapine therapy

Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug which has been linked to the development of cardiovascular side-effects. Here, Azzam et al . describe a 42-year-old male with refractory schizophrenia who presented with severe dilated cardiomyopathy, which was thought to have been caused by clozapine therapy.

- Badira Makhoul

- Irit Hochberg

- Zaher S Azzam

Coarctation of the aorta presenting as systemic hypertension in a young adult

Congenital heart defects can remain undiagnosed until adulthood. In this Case Study, Alegria et al . describe a 20-year-old male presenting with systemic hypertension who was found to have coarctation of the aorta, a bicuspid aortic valve, an ascending aortic aneurysm and an atrial septal defect. He was successfully treated in a single surgical procedure.

- Jorge R Alegria

- Harold M Burkhart

- Heidi M Connolly

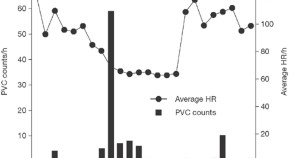

Cardiomyopathy induced by pulmonary vein tachycardia cured by catheter ablation

In this month's Case Study, Cha and colleagues present a 51-year-old male patient referred for consideration for heart transplantation because of recently diagnosed congestive heart failure refractory to medical therapy. He was diagnosed with cardiomyopathy resulting from pulmonary vein tachycardia, which was treated with catheter-based radiofrequency ablation of pulmonary vein tachycardia focus.

- Xiao-Ke Liu

- Bernard J Gersh

- Yong-Mei Cha

Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve and coronary artery disease visualized by 64-slice CT

In this month's Case Study, De Visser and colleagues present a 75-year-old male patient with a recent history of transient ischemic attack who underwent routine cardiological evaluation before a cystectomy. He was found to have coronary artery disease and an aortic valve papillary fibroelastoma—a rare, benign cardiac tumor. Multislice CT was successfully used to visualize the tumor and coronary arteries, before the patient underwent surgical excision of the tumor and an end-to-side anastomosis of the left internal mammary artery and the left anterior descending coronary artery.

- Randall N de Visser

- Carlos van Mieghem

- Tjebbe W Galema

Catheter ablation of premature ventricular contraction-induced cardiomyopathy

Premature ventricular complexes are a common form of arrhythmia and are typically considered to be benign. In this month's Case Study, however, Ezzat and colleagues present a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy which was postulated to be caused by premature ventricular complexes arising from the right ventricular outflow tract. She was successfully treated by electrophysiological mapping and cryoablation of the ectopic focus.

- Vivienne A Ezzat

- Reginald Liew

- David E Ward

Cardiac sarcoidosis concealed by arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy

A definitive diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis relies on the results of endomyocardial biopsy. In this Case Study Greif et al . describe a patient whose biopsy was negative for sarcoidosis—leading to a diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. Sarcoidosis was only revealed after the patient had progressed to end-stage heart failure and undergone cardiac transplantation several years later.

- Martin Greif

- Paraskevi Petrakopoulou

- Gerhard Steinbeck

A case of vagally mediated idiopathic ventricular fibrillation

In this month's Case Study, Kataoka and colleagues report a patient who experienced three episodes of syncope over the course of 2 years. Electrocardiography and 24h Holter monitoring revealed occasional premature ventricular complexes arising from the right ventricular outflow tract which, on a subsequent occasion, triggered an arrhythmic episode that degenerated into ventricular fibrillation. She was treated with radiofrequency catheter ablation and was fitted with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

- Masaharu Kataoka

- Seiji Takatsuki

- Hideo Mitamura

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Arq Bras Cardiol

- v.105(4); 2015 Oct

Case 4 – A 79-Year-Old Man with Congestive Heart Failure Due to Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Sumaia mustafa.

1 Instituto do Coração (InCor) HC-FMUSP, São Paulo, SP – Brasil

Alice Tatsuko Yamada

Fabio mitsuo lima.

2 Grupo Fleury Medicina e Saúde, São Paulo, SP – Brasil

Valdemir Melechco Carvalho

Vera demarchi aiello, jussara bianchi castelli.

JAP, a 79-year-old male and retired metalworker, born in Várzea Alegre (Ceará, Brazil) and residing in São Paulo was admitted to the hospital in October 2013 due to decompensated heart failure.

The patient was referred 1 year before to InCor with a history of progressive dyspnea triggered by less than ordinary activities, lower-extremity edema, and abdominal enlargement. He sought medical care due to the abdominal enlargement, which was diagnosed as an ascites. He denied chest pain, hospitalization due to myocardial infarction or stroke, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes.

The patient was a previous smoker and had stopped smoking at the age of 37 years. He was also an alcoholic and reported drinking alcohol for the last time 1 year before.

He was referred to InCor for treatment of heart failure.

An echocardiogram revealed an increased thickness in the septum (17 mm) and free left ventricular wall (15 mm), and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 26%.

The patient reported daily use of enalapril 10 mg, spironolactone 25 mg, furosemide 80 mg, omeprazole 40 mg, and ferrous sulfate (40 mg Fe) three tablets.

On March 12, 2013, his physical examination showed a weight of 55 kg, height of 1.75 m, body mass index (BMI) of 18 kg/m 2 , heart rate of 60 bpm, blood pressure of 90 X 50 mm Hg, and the presence of a hepatojugular reflux. There were no signs of jugular venous hypertension, and the pulmonary and cardiac auscultations were normal. He had ascites, and his liver was palpable 5 cm below the right costal margin. Peripheral pulses were palpable, and a ++/4+ edema was observed.

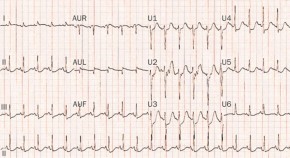

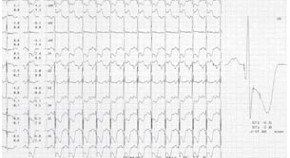

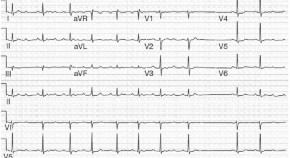

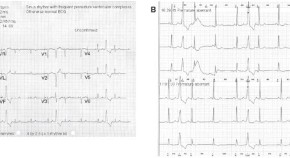

An ECG (February 23, 2012) had shown a sinus rhythm, heart rate of 52 bpm, PR interval of 192 ms, QRS duration of 106 ms, indirect signs of right atrial overload (wide variability in QRS amplitude between V1 and V2), and left atrial overload (prolonged and notched P waves), low QRS voltage in the frontal plane with an indeterminate axis, an electrically inactive area in the anteroseptal region and secondary changes in ventricular repolarization ( Figure 1 ).

ECG: sinus bradycardia, low-voltage QRS complexes in the frontal plane, indirect signs of right atrial overload (small QRS complexes in V1 and wide QRS complexes in V2), left atrial overload, electrically inactive area in the anteroseptal region.

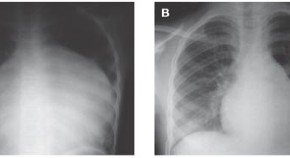

A chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly.

Laboratory tests performed on April 20, 2012, had shown the following results: hemoglobin 13.1 g/dL, hematocrit 40%, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 87 fL, leukocytes 9,230/mm 3 (banded neutrophils 1%, segmented neutrophils 35%, eosinophils 20%, basophils 1%, lymphocytes 33%, and monocytes 10%), platelets 222,000 /mm 3 , cholesterol 207 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol 54 mg/dL, LDL-cholesterol 138 mg/dL, triglycerides 77 mg/dL, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) 77 U/L, blood glucose 88 mg/dL, urea 80 mg/dL, creatinine 1.2 mg/dL (glomerular filtration rate ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m 2 ), sodium 131 mEq/L, potassium 6.3 mEq/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 22 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 34 U/L, uric acid 6.3 mg/dL, TSH 1.24 µUI/mL, free T4 1.36 ng/dL, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) 1.24 ng/mL. On urinalysis, urine specific gravity was 1.007, pH 5.5, the sediment was normal, and there were no abnormal elements.

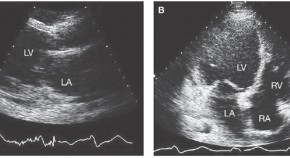

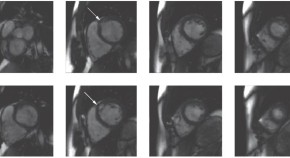

A new echocardiographic assessment on April 20, 2012, had shown an aortic diameter of 32 mm, left atrium of 52 mm, septal and posterior left ventricular wall thickness of 15 mm, diastolic/systolic left ventricular diameters of 46/40 mm, and left ventricular ejection fraction of 28%. Both ventricles had diffuse and marked hypokinesia. The valves were normal and the pulmonary artery systolic pressure was estimated at 32 mmHg ( Figure 2 ).

Echocardiogram - a) Four-chamber view: marked enlargement of the left and right atria; b) parasternal long-axis view: enlarged left atrium, left ventricular wall thickening, normal cavity.

A 24-hour electrocardiographic (Holter) monitoring on April 19, 2012, showed a baseline sinus rhythm with a lowest rate of 46 bpm and greatest rate of 97 bpm; 48 isolated, polymorphic, and paired ventricular extrasystoles; 137 atrial extrasystoles; and an episode of atrial tachycardia over three beats with a frequency of 98 bpm. There were no atrioventricular or intraventricular blocks interfering with the conduction of the stimulus.

The patient was transferred from the pacemaker clinic to the general cardiopathy clinic.

During a clinic appointment on January 22, 2013, the patient was asymptomatic and reported the use of enalapril 10 mg, spironolactone 25 mg, furosemide 60 mg, and carvedilol 12.5 mg. His physical examination was normal.

The main diagnostic hypotheses were hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy.

A testicular ultrasound (September 09, 2013) was normal, except for cystic formations in the right inguinal canal. An abdominal ultrasonography (September 10, 2013) showed substantial ascites and hepatic cysts with internal septations, and no signs of portal hypertension.

After presenting an increase in dyspnea with the development of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, worsening ascites and lower-extremity edema, and paresthesia on hands and feet, the patient was admitted to the hospital.

On physical examination (October 19, 2013) he was oriented and eupneic, with a heart rate of 69 bpm, blood pressure of 80 X 60 mmHg, a normal pulmonary auscultation, cardiac auscultation with arrhythmia and no murmurs, substantial ascites, and edema and hyperemia of the lower extremities.

A chest x-ray (October 21, 2013) showed cardiomegaly and interstitial lung infiltrates; the lateral incidence showed the right ventricle markedly enlarged ( Figures 3 and and4 4 ).

Chest x-ray (October 21, 2013), posteroanterior (PA) view: pulmonary interstitial infiltrates and cardiomegaly.

Chest x-ray (October 21, 2013) in lateral view: right ventricle markedly enlarged.

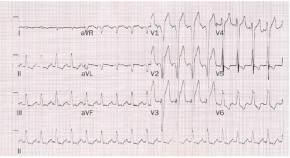

On ECG, the patient presented atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block, indirect signs of right atrial overload (Peñaloza-Tranchesi sign), heart rate of 61 bpm, low QRS voltage in the frontal plane, intraventricular conduction impairment, left ventricular overload, and secondary changes in ventricular repolarization ( Figure 5 ).

ECG: Atrial flutter, impaired intraventricular conduction, left ventricular overload.

Laboratory tests on October 19, 2013, showed the following results: hemoglobin 13.5 g/dL, hematocrit 42%, leukocytes 7,230/mm 3 (neutrophils 66%, eosinophils 12%, lymphocytes 13%, monocytes 9%), platelets 232,000 /mm 3 , urea 193 mg/dL, creatinine 2.03 m/dL (glomerular filtration rate of 34 mL/min/1,73 m 2 ), sodium 133 mEq/L, potassium 3.9 mEq/L, C-reactive protein (CRP) 18.1 mg/L, vitamin B12 360 pg/mL, folic acid 8.35 ng/mL, total bilirubin 0.75 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.37 mg/dL, AST 24 U/L, ALT 16 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (gamma GT) 241 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 166 U/L, iron 71 µg/dL, ferritin 62.9 ng/mL, prothrombin time (PT, INR) 0.95, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT, rel) 0.95, ionic calcium 1.09 mmol/L, chloride 89 mEq/L, and arterial lactate 15 mg/dL. Urinalysis showed urine specific gravity of 1.020, pH 5.5, proteinuria 0.25 g/L, epithelial cells 4,000/mL, leukocytes 2,000/mL, erythrocytes 3,000/mL, and hyaline casts 27,250/mL.

Another echocardiogram performed on October 21, 2013, showed a left atrial diameter of 56 mm, septal thickness of 18 mm, posterior wall thickness of 13 mm, left ventricle (diastole/systole) with 46/40 mm, left ventricular ejection fraction of 28%, pulmonary artery systolic pressure estimated at 45 mmHg, marked left ventricular and moderate right ventricular dysfunction, and moderate tricuspid insufficiency.

An ultrasound of the kidneys and urinary tract (October 24, 2013) showed that the left kidney measured 9.6 cm, and the right kidney measured 9 cm and had simple cortical cysts.

Serum protein electrophoresis was normal, and a urinary electrophoresis did not detect proteins. Measurement of serum beta 2-microglobulin was 7 mg/mL (limit for individuals above the age of 60 years = 2.6 mg/mL).

A biopsy of the cheek mucosa (October 23, 2013) showed deposits of amyloid substance in the deep chorion and in the adjacent adipose tissue.

Stool microscopy (October 25, 2013) was positive for Blastocystis hominis and Entamoeba coli .

A paracentesis drained 3,500 mL of a yellowish fluid with normal cellularity.

During hospitalization, the patient received daily intravenous furosemide 60 mg, carvedilol 25 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 100 mg, hydralazine 75 mg, isosorbide 80 mg, aspirin 100 mg, spironolactone 25 mg, and enoxaparin 40 mg. The patient also received oxacillin 2 g/day for 7 days initially, and later vancomycin, meropenem and teicoplanin, and piperacillin/tazobactam.

A new chest x-ray (November 08, 2013) showed cardiomegaly and an interstitial pulmonary infiltrate suggestive of pulmonary congestion ( Figure 6 ).

Chest x-ray (November 08, 2013): pulmonary interstitial infiltrates suggestive of pulmonary congestion and cardiomegaly.

During a new paracentesis (November 11, 2013), the aspirated fluid was bloody, and the patient presented hypotension and decreased consciousness, progressing to cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity, which was reverted. This was followed by ventricular tachycardia, cardioverted with 200 J.

New tests (November 11, 2013 - morning) showed the following results: hemoglobin 11.9 g/dL, hematocrit 36%, leukocytes 7,780/mm 3 (neutrophils 83%, eosinophils 2%, lymphocytes 9%, and monocytes 6%), platelets 188,000 /mm 3 , urea 301 mg/dL, creatinine 4.14 mg/dL, sodium 125 mEq/L, potassium 4.4 mEq/L, CRP 97.06 mg/L. On venous blood gas analysis, pH was 7.33, bicarbonate 19.9 mmol/L, and base excess (-) 5.4 mmol/L. Additional tests performed on the same day (November 11, 2013 – 5:44 pm) showed hemoglobin of 6.3 g/dL, sodium of 123 mEq/L, potassium of 5.4 mEq/L, venous lactate of 93 mg/dL, PT (INR) of 3.2 and aPTT (rel) of 1.98.

Later during the day, the patient progressed with shock refractory to high doses of dobutamine (20 µg/kg/min ) and norepinephrine (1.2 µg/kg/min), followed by cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity that recovered but was followed by a new irreversible cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity during intra-aortic balloon placement (November 11, 2013 – 6:30 pm).

Clinical Aspects

The patient JAB, a 79-year-old previous smoker and alcoholic man residing in São Paulo, attended an outpatient clinic at InCor due to heart failure which worsened progressively since 2012, requiring hospitalization for treatment.

Heart failure is a systemic and complex clinical syndrome, defined as a cardiac dysfunction that causes the blood supply to be insufficient to meet tissular metabolic demands, in the presence of a normal venous return, or which only meets the demands with high filling pressure 1 .

Prevalence studies estimate that 23 million individuals worldwide have heart failure and that 2 million new cases are diagnosed annually. According to DATASUS information, Brazil has about 2 million individuals with heart failure and 240,000 new cases diagnosed annually 2 .

The main causes of heart failure are hypertension, coronary artery disease, Chagas disease, cardiomyopathies, endocrinopathies, toxins, and drugs, among others 1 . The cardinal manifestations of heart failure are dyspnea and fatigue, and may include exercise intolerance, fluid retention, and pulmonary and systemic congestion 3 . The patient in this case presented with progressive dyspnea triggered by less than ordinary activities, lower-extremity edema, and ascites, which characterized him as class III according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.

On complementary tests, the echocardiogram showed marked left ventricular hypertrophy with some degree of asymmetry, and reduced ejection fraction. Cardiac hypertrophy is often associated with hypertension or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but both present with normal or increased ECG voltage. Therefore, the findings of ventricular hypertrophy associated with decreased ECG voltage in the absence of pericardial effusion are exclusive of infiltrative cardiomyopathies, a group of cardiac disorders within the restrictive cardiomyopathies 4 .

Restrictive cardiomyopathy may occur with a wide variety of systemic diseases. Some restrictive cardiomyopathies are rare in clinical practice and may present initially with heart failure. This type of cardiomyopathy is characterized by filling restriction, with reduced diastolic volume in one or both ventricles, normal or close to normal systolic function, and ventricular wall thickening. It may be idiopathic or associated with other diseases, such as amyloidosis, endomyocardial disease with or without eosinophilia, sarcoidosis, and hemochromatosis, among others 5 . In this case, the presence of amyloid deposits in the cheek mucosa biopsy indicated a diagnosis of amyloidosis, and the increase in serum beta-2 microglobulin reflected a worse prognosis 5 .

Amyloidosis is characterized by deposits of amyloid protein in different organs and tissues. These deposits may be responsible for different types of clinical presentation, with a spectrum that ranges from lack of symptoms to sequential organic dysfunction culminating with death 6 .

Cardiac amyloidosis is caused by amyloid deposits around cardiac fibers, and can be identified by a left ventricular wall thickening exceeding 12 mm in the absence of hypertension with at least one of the following characteristics: conduction disorder and low voltage complexes on the ECG, restrictive cardiomyopathy, low cardiac output, isolate atrial involvement (as commonly seen in elderly individuals) or diffuse involvement affecting the ventricles. In the latter situation, it can cause heart failure with a poor prognosis 4 , 7 .

Our patient, who was not hypertensive, presented low voltage complexes on the ECG, which were more prominent in the frontal plane, an electrically inactive area in the anteroseptal region, and diffuse changes in ventricular repolarization. This pattern can be found in some diseases in addition to infiltrative cardiomyopathies, such as decompensated hypothyroidism, pericardial effusion, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and obesity. Other electrocardiographic information, such as the pattern of infarction, can be found with or without obstructive coronary atherosclerotic disease by deposition of substances in the microcirculation and small intramyocardial arteries 8 .

Amyloidosis may be classified as primary, secondary, or hereditary. Primary amyloidosis, in which AL is the primarily involved protein, may be further subdivided into idiopathic (localized forms) or associated with multiple myeloma or other plasma cell dyscrasias (systemic forms) 9 .

Multiple myeloma is a neoplastic disorder of plasma cells that affects individuals with an average age of 70 years at diagnosis. Some characteristics of the patient in this case could suggest multiple myeloma: age, male gender, renal failure, and cylindruria. However, other important clinical parameters were absent, such as hypercalcemia, anemia, and bone disease. Also, the Bence-Jones protein, which is present in up to 75% of the cases, was not detected on urinary electrophoresis 10 .

The secondary type of amyloidosis results from deposits of AA protein and frequently arises as a complication of infectious or inflammatory processes, such as rheumatoid arthritis (the most common cause), tuberculosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, syphilis, or even neoplastic diseases. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are present in these disorders, stimulate the hepatic production of serum A amyloid 11 .

Finally, the hereditary type of the disease has an autosomal dominant transmission and may involve several types of amyloid proteins, such as the AA protein in some groups of patients with familial Mediterranean fever, and the ATTR protein (derived from the transthyretin or prealbumin) in familial amyloid polyneuropathy 12 .

As for the treatment, measures to control symptoms related to diastolic heart failure, such as volume control, should be implemented. Diuretics and vasodilators should be administered with caution since the cardiac output in these patients is greatly dependent on increased venous pressures. Specific treatment should be directed to the etiology of the amyloidosis 13 .

After an evaluation in the clinic on January, 2013, the patient received medications that are proven to modify the rates of hospitalization and mortality in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aldosterone antagonist), and symptom-relieving agents (diuretics) 14 . The patient was receiving enalapril 10 mg, spironolactone 25 mg, furosemide 60 mg, and carvedilol 12.5 mg.

After 8 months, due to the decompensated heart failure and hypotension, the patient returned to the emergency room and required hospitalization. The use of conventional therapy for heart failure often worsens the progression of amyloidosis. Therefore, cardiac amyloidosis should be suspected when the patient’s clinical condition worsens in response to conventional treatment, particularly in individuals older than 50 years. The therapy is exclusively symptomatic and should not include digitalis, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or calcium channel antagonists, since some studies have shown an increased sensitivity to these drugs which can lead to hypotension and intensification of conduction disorders 15 .

Therefore, the decompensation of the patient’s heart failure with deterioration of the ascites culminated in two paracenteses, with the last paracentesis probably accompanied by a puncture accident due to the appearance of bloody fluid, decrease in red blood count, and hypovolemic shock associated with cardiogenic shock, culminating in a mixed refractory shock and cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity (Dr. Sumaia Mustafa, Dr. Alice Tatsuko Yamada).

Diagnostic hypotheses:

- Heart failure due to restrictive cardiomyopathy (probably cardiac amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma);

- Decompensated heart failure;

- Cause of death: mixed shock (hypovolemic + cardiogenic) with cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity (Dr. Sumaia Mustafa, Dr. Alice Tatsuko Yamada) .

The heart weighed 680 g and was increased in volume due to moderate cavity dilation and wall thickening in all four chambers ( Figure 7 ). The myocardium had an increased consistency. The endocardium of the atria, in particular, was finely granular and brown-yellowish in appearance. There were no significant changes in the valves, and the coronary arteries were armed without significant obstruction of their lumen.

Gross Section of the heart base showing biatrial enlargement and thickening of the cardiac walls. Note the granular aspect of the right atrial endocardium (area demarcated with an ellipse).

Histological examination of the myocardium showed extracellular deposits of amorphous and eosinophilic material promoting atrophy of the contractile cells. These deposits stained positive with Congo red when observed under polarized light ( Figures 8 and and9). 9 ). This same material was present in the interstitium of the cheek mucosa evaluated by biopsy ( Figure 10 ) according to data from the clinical history. Deposits were also observed in the tunica media of muscular arteries in both lungs ( Figure 11 ) and in the renal hilum.

Photomicrography of the ventricular myocardium showing atrophic cardiomyocytes due to deposits of amorphous eosinophilic material in the interstitium. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (20x objective magnification).

Photomicrography of myocardial tissue obtained under polarized light. Note the greenish material that corresponds to amyloid substance stained by Congo red (5x objective magnification).

Biopsy of the cheek mucosa performed approximately 1 month before death. Note that the mucosal chorion reacts positively to Congo red (photomicrography obtained under conventional microscopy with a 10x objective magnification).

Photomicrography of a peripheral muscular pulmonary artery showing areas of positivity for deposits of amyloid in the arterial wall (Congo red staining photographed under conventional microscopy, 5x objective magnification).

Bone marrow histological examination showed hypercellularity of moderate degree for the patient's age, and no signs of monoclonal proliferation. Immunohistochemical reactions for immunoglobulin kappa and lambda light chains were inconclusive, and CD138 labeling showed no proliferation of plasma cells.

Autopsy findings included a 4-cm hepatic cyst in the right lobe lined with flat cells without atypia, and retention cysts in the right kidney. The right adrenal weighed 44 g and was increased in volume and completely calcified. The histological examination showed only calcification and was inconclusive for the possibility of prior malignancy.

There was a voluminous serosanguinous ascites and a serous pericardial effusion. We found no visceral or abdominal vessel injury resulting from the paracentesis and the amount of bloody material in the ascitic fluid was small.

Histologically, there were signs of congestive heart failure in the lungs and liver (Dr. Vera Demarchi Aiello) .

Diagnoses: Cardiovascular amyloidosis;

Congestive heart failure;

Calcified nodule in the right adrenal gland (Dr. Vera Demarchi Aiello).

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry gathers all qualities to establish an unequivocal diagnosis of amyloidosis since it has a high sensitivity and ability to identify the proteins through sequencing 16 . Therefore, we adopted an approach based on shotgun proteomics to identify the amyloid deposits in the sample.

Sections of heart tissue containing amyloid deposits (confirmed by staining with Congo red) fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin were dissected and the proteins were then extracted with Liquid Tissue® MS Protein Prep Kit (Expression Pathology) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After digestion with trypsin, the resulting peptides were analyzed by high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry using the mass spectrometer Q-Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The acquisitions of spectral data were carried out using the DDA (date dependent analysis) mode with a selection of the 10 most abundant ions for sequencing by HCD (Higher-energy collisional dissociation). The data were processed with the software MaxQuant. The proteomic analysis was performed in triplicate.

The processed data generated lists of proteins representing the protein content of the sample. In total, 25 possible amyloid proteins were investigated in these lists in order to determine the identity of the deposited substance. There were 15 peptides belonging to transthyretin that together covered 76.2% of the full sequence of the protein.

To confirm the result, we also evaluated the abundance of different peptides present in the sample. Among the 25 most abundant peptides, three belonged to transthyretin (ALGISPFHEHAEVVFTANDSGPR, TSESGELHGLTTEEEFVEGIYK, and GSPAINVAVHVFR). The others were assigned to actin, myosin, desmin, and myoglobin, confirming the identity of the amyloid protein (Dr. Fabio Mitsuo Lima and Dr. Valdemir Melechco Carvalho- Fleury Group).

Cardiovascular amyloidosis due to deposition of transthyretin (Dr. Vera Demarchi Aiello, Dr. Jussara Bianchi Castelli, Dr. Fabio Mitsuo Lima and Dr. Valdemir Melechco Carvalho) .

This case demonstrates how important it is in amyloidosis to investigate the deposited substance. Amyloidosis is a generic name to describe a group of diseases characterized by extracellular deposits of different substances in different organs. These substances are fibrillar proteins that become insoluble with changes in their spatial conformation. More than 20 types of proteins have been described in these deposits 16 . From an anatomopathological perspective, the deposits can be characterized by immunohistochemical reactions, but with some restrictions as described below. The cardiovascular system is most often affected by the AL protein (deposits of light-chain immunoglobulin), senile, and familial forms 17 , 18 .

The pathologist may identify neoplastic proliferation of plasmocytes producing the deposited immunoglobulins by bone marrow examination labeled for these cells. In tissue preparations, the pathologist may demonstrate by immunohistochemistry if the deposited substance is one of these immunoglobulins. Some authors recommend a biopsy of other organs before the endomyocardial biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and identify the type of amyloid 19 . In this case, immunohistochemical labeling was not helpful in establishing the diagnosis, because it was inconclusive to the type of protein deposited.

Although there are reports in the literature of identification of transthyretin in tissues by immunohistochemical reactions, this was not possible in this case. However, with mass spectrometry analysis, we identified that the deposited protein was transthyretin, which is usually present in senile and familial forms of amyloidosis. In this patient, the familial form was less likely due to the exclusive involvement of heart and blood vessels. However, only a genetic research and evaluation of other members of the family could exclude it completely.

Another point that deserves discussion in this case is the laboratory report of high levels of immunoglobulin E. We could assume that this referred to the deposited protein, but the diagnostic methods performed to complement the autopsy revealed that this was not the case.

Dr. Vera Demarchi Aiello and Dr. Jussara Bianchi Castelli (Pathology Laboratory, InCor, FMUSP).

Heart Failure; Cardiomyopathy, Restrictive; Ascites; Cardiomegaly; Heart Arrest.

Editor da Seção: Alfredo José Mansur ( rb.psu.rocni@rusnamja )

Editores Associados: Desidério Favarato ( rb.psu.rocni@otaravaflcd )

Vera Demarchi Aiello ( rb.psu.rocni@arevpna )

- Associations

- Working Groups

- Escardio.org

- ESC eLearning

Show navigation Hide navigation

- European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Journal Family

- EHJ - Case Reports

European Heart Journal – Case Reports is recruiting new members for their editor and reviewer teams.

EHJ – Case Reports

Fully open-access journal of international case reports - only online.

The ESC's European Heart Journal – Case Reports (EHJ-Case Reports) publishes high quality, valuable, educational case reports, images, and quality improvement projects in all aspects of cardiology and cardiovascular medicine. The cases will be of interest to senior medical students and doctors during the early stages of their medical careers.

The primary aim is to promote learning among junior cardiologists as regards both the published content as well as the review-and-editorial process. The journal operates a mentorship plan to develop junior reviewers and editors under the close guidance of experienced senior reviewers and editors.

- Editor-in-Chief: Philipp Sommer

- Current volume: 8 (year 2024)

- Issues per subscription: 12

- Impact Factor 2023: 0.8

Editor-in-Chief history

| Name | Start Date | End Date |

| Professor John Camm | 01/07/2016 | 31/12/2022 |

| Professor Philipp Sommer | 01/01/2023 |

Publisher Information

Connect with us on x, frequently-asked questions.

Updates on latest articles

Receive the table of contents in your mailbox.

Track topics and authors important to you and receive articles in your mailbox.

For Authors

Before being published, all manuscripts go through double-blind, peer review by experienced international experts.

Submit a Manuscript

Instructions for authors.

- ESC Board and Committees

- ESC Policies

- Statutes & Reports

- ESC Press Office

- Press Releases

- ESC Congress

- ESC Cardio Talk

- Our Offices

- Conference Facilities

- Jobs in Cardiology

- Terms & Conditions

- Update your cookie settings

Need help?

Help centre Contact us

© 2024 European Society of Cardiology. All rights reserved.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author videos

- ESC Content Collections

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About European Heart Journal Supplements

- About the European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, case presentation.

- < Previous

Clinical case: heart failure and ischaemic heart disease

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Giuseppe M C Rosano, Clinical case: heart failure and ischaemic heart disease, European Heart Journal Supplements , Volume 21, Issue Supplement_C, April 2019, Pages C42–C44, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/suz046

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patients with ischaemic heart disease that develop heart failure should be treated as per appropriate European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines.

Glucose control in diabetic patients with heart failure should be more lenient that in patients without cardiovascular disease.

Optimization of cardiac metabolism and control of heart rate should be a priority for the treatment of angina in patients with heart failure of ischaemic origin.

This clinical case refers to an 83-year-old man with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and shows that implementation of appropriate medical therapy according to the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association (ESC/HFA) guidelines improves symptoms and quality of life. 1 The case also illustrates that optimization of glucose metabolism with a more lenient glucose control was most probably important in improving the overall clinical status and functional capacity.

The patient has family history of coronary artery disease as his brother had suffered an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at the age of 64 and his sister had received coronary artery by-pass. He also has a 14-year diagnosis of arterial hypertension, and he is diabetic on oral glucose-lowering agents since 12 years. He smokes 30 cigarettes per day since childhood.

In February 2009, after 2 weeks of angina for moderate efforts, he suffered an acute anterior myocardial infarction. He presented late (after 14 h since symptom onset) at the hospital where he had been treated conservatively and had been discharged on medical therapy: Atenolol 50 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg tds, Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50, and Fluticasone 500 mg oral inhalers.

Four weeks after discharge, he underwent a planned electrocardiogram (ECG) stress test that documented silent effort-induced ST-segment depression (1.5 mm in V4–V6) at 50 W.

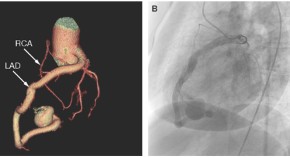

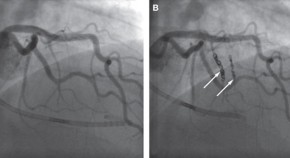

He underwent a coronary angiography (June 2009) and left ventriculography that showed a not dilated left ventricle with apical dyskinesia, normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, 52%); occlusion of proximal LAD, 60% stenosis of circumflex (CX), and 60% stenosis of distal right coronary artery (RCA). An attempt to cross the occluded left anterior descending (LAD) was unsuccessful.

He was therefore discharged on medical therapy with: Atenolol 50 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Perindopril 4 mg o.d., oral isosorbide mono-nitrate (ISMN) 60 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., metformin 850 mg tds, Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg, and Fluticasone 500 mcg b.i.d. oral inhalers.

He had been well for a few months but in March 2010 he started to complain of retrosternal constriction associated to dyspnoea for moderate efforts (New York Heart Association (NYHA) II–III, Canadian Class II).

For this reason, he was prescribed a second coronary angiography that showed progression of atherosclerosis with 80% stenosis on the circumflex (after the I obtuse marginal branch) and distal RCA. The LAD was still occluded.

After consultation with the heart team, CABG was avoided because surgical the risk was deemed too high and the patient underwent palliative percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of CX and RCA. It was again attempted to cross the occlusion on the LAD. But this attempt was, again, unsuccessful. Collateral circulation from posterior interventricular artery (PDL) to the LAD was found. The pre-PCI echocardiogram documented moderate left ventricular dysfunction (EF 38%), the pre-discharge echocardiogram documented a LVEF of 34%. Because of the reduced LVEF, atenolol was changed for Bisoprolol (5 mg o.d.).

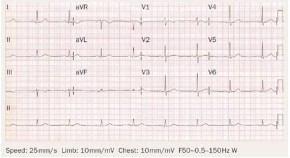

At follow-up visit in December 2012, the clinical status and the haemodynamic conditions had deteriorated. He complained of worsening effort-induced dyspnoea/angina that now occurred for less than a flight of stairs (NYHA III). On clinical examination clear signs of worsening heart failure were detected ( Table 1 ). His medical therapy was modified to: Bisoprolol 5 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 20 mg o.d., Amlodipine 2.5 mg o.d., Perindopil 5 mg o.d., ISMN 60 mg o.d., Aspirin 100 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg tds, Furosemide 50 mg o.d., Gliclazide 30 mg o.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg oral inhaler, and Fluticasone 500 mcg oral inhaler. A stress perfusion cardiac scintigraphy was requested and revealed dilated ventricles with LVEF 19%, fixed apical perfusion defect and reversible perfusion defect of the antero-septal wall (ischaemic burden <10%, Figure 1 ). He was admitted, and an ICD was implanted.

Clinical parameters during follow-up visits

| . | December 2012 . | March 2013 . | September 2013 . | January 2014 . | January 2015 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 72 | 71 | 74 | 70 | 68 |

| Height (cm) | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| BMI | 24.9 | 24.9 | 25.1 | 24.9 | 24.8 |

| JVP | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | Normal | Normal |

| Oedema | Bilateral oedema up to mid shins | Bilateral pretibial oedema (2+) | Bilateral pretibial oedema (3+) | No pedal oedema | No pedal oedema |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 115/80 | 115/75 | 110/60 | 110/70 | 112/68 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 88 | 86 | 92 | 68 | 56 |

| Auscultation | |||||

| Heart | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex |

| Lungs | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar and mid lung crackles | Clear | Clear |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| FPG (mg/dL) | 100 | 98 | 96 | 106 | 112 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 7 | 7.3 |

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Triglycerides | 118 mg/dL | NA | NA | 107 mg/dL | 114 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 146 mg/dL | NA | NA | 142 mg/dL | 148 mg/dL |

| LDL-C | 68 mg/dL | NA | NA | 64 mg/dL | 68 mg/dL |

| HDL-C | 51 mg/dL | NA | NA | 48 mg/dL | 54 mg/dL |

| BNP | NA | 862 | 1670 | 276 | 244 |

| LVEF | 19 | 20 | 32 | 32 | |

| . | December 2012 . | March 2013 . | September 2013 . | January 2014 . | January 2015 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 72 | 71 | 74 | 70 | 68 |

| Height (cm) | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| BMI | 24.9 | 24.9 | 25.1 | 24.9 | 24.8 |

| JVP | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | +2 cm H O | Normal | Normal |

| Oedema | Bilateral oedema up to mid shins | Bilateral pretibial oedema (2+) | Bilateral pretibial oedema (3+) | No pedal oedema | No pedal oedema |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 115/80 | 115/75 | 110/60 | 110/70 | 112/68 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 88 | 86 | 92 | 68 | 56 |

| Auscultation | |||||

| Heart | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex, III sound | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex | Systolic murmur 4/6 at apex |

| Lungs | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar crackles | Bilateral fine basilar and mid lung crackles | Clear | Clear |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| FPG (mg/dL) | 100 | 98 | 96 | 106 | 112 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 7 | 7.3 |

| Plasma creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Triglycerides | 118 mg/dL | NA | NA | 107 mg/dL | 114 mg/dL |

| Total cholesterol | 146 mg/dL | NA | NA | 142 mg/dL | 148 mg/dL |

| LDL-C | 68 mg/dL | NA | NA | 64 mg/dL | 68 mg/dL |

| HDL-C | 51 mg/dL | NA | NA | 48 mg/dL | 54 mg/dL |

| BNP | NA | 862 | 1670 | 276 | 244 |

| LVEF | 19 | 20 | 32 | 32 | |

Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy and left ventriculography showing dilated left ventricle with left ventricular ejection fraction 19%. Reversible perfusion defects on the antero-septal wall and fixed apical perfusion defect.

In March 2013, he felt slightly better but still complained of effort-induced dyspnoea/angina (NYHA III, Table 1 ). Medical therapy was updated with bisoprolol changed with Nebivolol 5 mg o.d. and perindopril changed to Enalapril 10 mg b.i.d. The switch from bisoprolol to nebivolol was undertaken because of the better tolerability and outcome data with nebivolol in elderly patients with heart failure. Perindopril was switched to enalapril because the first one has no indication for the treatment of heart failure.

In September 2013, the clinical conditions were unchanged, he still complained of effort-induced dyspnoea/angina (NYHA III) and did not notice any change in his exercise capacity. His BNP was 1670. He was referred for a 3-month cycle of cardiac rehabilitation during which his medical therapy was changed to: Nebivolol 5 mg o.d., Ivabradine 5 mg b.i.d., uptitrated in October to 7.5 b.i.d., Trimetazidine 20 mg tds, Furosemide 50 mg, Metolazone 5 mg o.d., K-canrenoate 50 mg, Enalapril 10 mg b.i.d., Clopidogrel 75 mg o.d., Atorvastatin 40 mg o.d., Metformin 500 mg b.i.d., Salmeterol 50 mcg oral inhaler, and Fluticasone 500 mcg oral inhaler.

At the follow-up visit in January 2014, he felt much better and had symptomatically, he no longer complained of angina, nor dyspnoea (NYHA Class II, Table 1 ). Trimetazidine was added because of its benefits in heart failure patients of ischaemic origin and because of its effect on functional capacity. Ivabradine was added to reduce heart rate since it was felt that increasing nebivolol, that was already titrated to an effective dose, would have had led to hypotension.

He missed his follow-up visits in June and October 2014 because he was feeling well and he had decided to spend some time at his house in the south of Italy. In January and June 2015, he was well, asymptomatic (NYHA I–II) and able to attend his daily activities. He did not complain of angina nor dyspnoea and reported no limitations in his daily activities. Unfortunately, in November 2015 he was hit by a moped while on the zebra crossing in Rome and he later died in hospital as a consequence of the trauma.

This case highlights the need of optimizing both the heart failure and the anti-anginal medications in patients with heart failure of ischaemic origin. This patient has improved dramatically after the up-titration of diuretics, the control of heart rate with nebivolol and ivabradine and the additional use of trimetazidine. 1–3 All these drugs have contributed to improve the clinical status together with a more lenient control of glucose metabolism. 4 This is another crucial point to take into account in diabetic patients, especially if elderly, with heart failure in whom aggressive glucose control is detrimental for their functional capacity and long-term prognosis. 5

IRCCS San Raffaele - Ricerca corrente Ministero della Salute 2018.

Conflict of interest : none declared. The authors didn’t receive any financial support in terms of honorarium by Servier for the supplement articles.

Ponikowski P , Voors AA , Anker SD , Bueno H , Cleland JG , Coats AJ , Falk V , González-Juanatey JR , Harjola VP , Jankowska EA , Jessup M , Linde C , Nihoyannopoulos P , Parissis JT , Pieske B , Riley JP , Rosano GM , Ruilope LM , Ruschitzka F , Rutten FH , van der Meer P ; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the Special Contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC . Eur J Heart Fail 2016 ; 18 : 891 – 975 .

Google Scholar

Rosano GM , Vitale C. Metabolic modulation of cardiac metabolism in heart failure . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 99 – 103 .

Vitale C , Ilaria S , Rosano GM. Pharmacological interventions effective in improving exercise capacity in heart failure . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 1 – 27 .

Seferović PM , Petrie MC , Filippatos GS , Anker SD , Rosano G , Bauersachs J , Paulus WJ , Komajda M , Cosentino F , de Boer RA , Farmakis D , Doehner W , Lambrinou E , Lopatin Y , Piepoli MF , Theodorakis MJ , Wiggers H , Lekakis J , Mebazaa A , Mamas MA , Tschöpe C , Hoes AW , Seferović JP , Logue J , McDonagh T , Riley JP , Milinković I , Polovina M , van Veldhuisen DJ , Lainscak M , Maggioni AP , Ruschitzka F , McMurray JJV. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology . Eur J Heart Fail 2018 ; 20 : 853 – 872 .

Vitale C , Spoletini I , Rosano GM. Frailty in heart failure: implications for management . Card Fail Rev 2018 ; 4 : 104 – 106 .

- myocardial ischemia

- cardiac rehabilitation

- heart failure

- older adult

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| April 2019 | 719 |

| May 2019 | 146 |

| June 2019 | 86 |

| July 2019 | 98 |

| August 2019 | 112 |

| September 2019 | 144 |

| October 2019 | 281 |

| November 2019 | 263 |

| December 2019 | 229 |

| January 2020 | 254 |

| February 2020 | 303 |

| March 2020 | 271 |

| April 2020 | 380 |

| May 2020 | 372 |

| June 2020 | 427 |

| July 2020 | 320 |

| August 2020 | 307 |

| September 2020 | 376 |

| October 2020 | 553 |

| November 2020 | 459 |

| December 2020 | 473 |

| January 2021 | 305 |

| February 2021 | 424 |

| March 2021 | 479 |

| April 2021 | 445 |

| May 2021 | 251 |

| June 2021 | 307 |

| July 2021 | 228 |

| August 2021 | 248 |

| September 2021 | 383 |

| October 2021 | 414 |

| November 2021 | 442 |

| December 2021 | 367 |

| January 2022 | 276 |

| February 2022 | 354 |

| March 2022 | 537 |

| April 2022 | 373 |

| May 2022 | 451 |

| June 2022 | 253 |

| July 2022 | 161 |

| August 2022 | 208 |

| September 2022 | 281 |

| October 2022 | 424 |

| November 2022 | 568 |

| December 2022 | 442 |

| January 2023 | 305 |

| February 2023 | 357 |

| March 2023 | 533 |

| April 2023 | 474 |

| May 2023 | 403 |

| June 2023 | 235 |

| July 2023 | 242 |

| August 2023 | 230 |

| September 2023 | 339 |

| October 2023 | 456 |

| November 2023 | 477 |

| December 2023 | 262 |

| January 2024 | 226 |

| February 2024 | 283 |

| March 2024 | 282 |

| April 2024 | 400 |

| May 2024 | 298 |

| June 2024 | 103 |

| July 2024 | 119 |

| August 2024 | 125 |

| September 2024 | 109 |

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1554-2815

- Print ISSN 1520-765X

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland

Respiratory viruses continue to circulate in Maryland, so masking remains strongly recommended when you visit Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. To protect your loved one, please do not visit if you are sick or have a COVID-19 positive test result. Get more resources on masking and COVID-19 precautions .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Center for Bloodless Medicine and Surgery

Case study: cardiac surgery, case study 1:, radial artery approach for cardiac catheterization followed by an "off-pump" coronary artery bypass surgery.

A 66-year old male Jehovah’s Witness patient was brought to the hospital with chest pain, and referred for a cardiac catheterization. He had a positive nuclear stress test that showed reduced blood flow to the left ventricle with a high suspicion for coronary artery disease.

Dr. John Resar, the director of the cardiac catheterization lab at Johns Hopkins performed the procedure. In order to reduce blood loss from the cardiac catheterization, the approach was planned through the radial artery (in the arm) rather than the femoral artery (in the groin). This approach is associated with reduced bleeding during and after the procedure. The total blood loss during the cardiac catheterization procedure was 50 mls (1% of total blood volume). As expected, the procedure revealed high-grade triple vessel disease (narrowing) that was not treatable with coronary stents. Coronary artery bypass surgery was recommended.

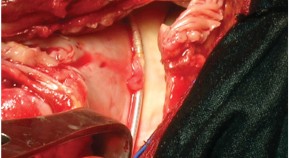

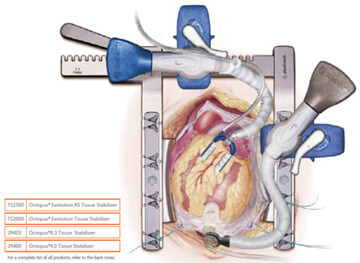

Dr. John Conte performed the coronary bypass surgery. Of interest is the fact that in 1999, Dr. Conte published a case report of the first ever successful bloodless lung transplant in a Jehovah’s Witness patient. In this case presented here, he decided the patient would be best served by performing an "off-pump" cardiac surgery where the heart lung bypass machine is not used. This technique reduces the blood loss that is commonly associated with the bypass machine, since with traditional bypass a substantial amount of the patient’s blood is left behind in the circuit of the machine and is unrecoverable.

The 4-hour surgery went very well. The saphenous vein from his right leg was harvested using an endoscopic approach. Compared to the traditional technique, this method uses a smaller incision to harvest the vein. The internal mammary artery and the saphenous vein were both used to provide blood flow to the narrowed coronary arteries. A special “octopus retractor” was used to stabilize the heart because during off-pump surgery the heart continues to beat (thus the term “beating heart surgery”), unlike the traditional on-pump method where the heart is arrested and completely still. The hemoglobin level was 13.8 before surgery and 13.0 three days later when the patient was discharged from the hospital. Two weeks after the surgery, the patient attended the open house for our Bloodless Medicine and Surgery Program and looked and felt "as good as ever".

Case Study 2:

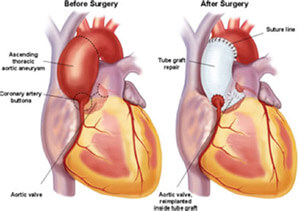

Aortic valve and aortic root replacement without blood transfusion.

A 46-year old female Jehovah’s Witness patient had severe aortic valve regurgitation along with an ascending aortic aneurysm. She had been seen at two other major academic centers in hopes of having a valve replacement along with repair of her “aortic root” (the section of aorta that joins the heart above the aortic valve), but was unable to find a team of physicians that would perform the surgery without blood transfusion.

Dr. Duke Cameron, the former Chief of Cardiac Surgery saw her along with Dr. Steven Frank, Director of the Johns Hopkins Bloodless Medicine and Surgery Program. With the patient and her family present, they reviewed the echocardiogram and cardiac catheterization report from another hospital. At the time, a discussion took place about the various methods of blood conservation and the various alternatives to transfusion. The patient and her family agreed that blood salvage (Cell Saver) and intraoperative autologous normovolemic hemodilution (IANH) were acceptable options. The patient was sent to the lab for routine blood tests and her hemoglobin level was suboptimal (13.0 g/dL) for this type of surgery. One complicating factor was the patient’s body weight of 95 lbs, which means that her total blood volume and red cell mass was about ½ that of a normal sized adult.

The patient was scheduled for a 3-week course of erythropoietin and intravenous iron at the infusion clinic at Johns Hopkins. The patient responded nicely to the treatments and her hemoglobin level increased to 15.1 g/dL, at which time the surgery was scheduled.

After the patient was under general anesthesia, 2 units of her own blood were removed as part of the IANH technique. These 2 units would be given back to her near the end of the surgery. During surgery, the Perfusionist, who operates the heart lung machine, was able to use a method called retrograde autologous prime (RAP), whereby the patient’s own blood is used to prime the circuit in an effort to conserve the patient’s blood volume.

After the surgical procedure, the patient was noted to have some cardiac ischemia (deficient blood flow to the left coronary artery). She was taken to the cardiac cath lab where a coronary stent was placed by an interventional cardiologist into her left main coronary artery. The next day she was weaned of the ventilator and she recovered nicely. Our Bloodless team Hematology consultant, Dr. Linda Resar guided her postoperative therapy which included IV iron and erythropoietin. She was discharged from the hospital with a hemoglobin of 8.0 g/dL, and she and her family had a Baltimore crab dinner before returning home to Roanoke, VA.

Cardiology Cases & Quizzes

- A 29-Year-Old With Raised Lesions and Unintended Weight Loss The patient has experienced weight loss of 10 kg in the past 3 months, accompanied by polyphagia, polydipsia, and polyuria. Medscape , June 13, 2024

- Constant Headache and Too Tired to Party A 27-year-old woman who has had constant headaches since she was a teenager presents after falling asleep at work. Her friends say she's always 'too tired to party.' Do you know what's wrong? Medscape , May 31, 2024

- Fast Five Quiz: Electrolyte Imbalances Are you familiar with signs of electrolyte imbalances and best practices for workup and treating patients with common electrolyte disturbances? Find out with this short quiz. Medscape , May 30, 2024

- ECG Challenge: Hyperlipidemia and Irregular Pulse A 48-year-old man with a history of hyperlipidemia has an irregular pulse during a routine check-up. What does the ECG show? Medscape Cardiology , May 22, 2024

- Patient Seeking Nondrug Therapy for Hypertension She has made some dietary changes and wants to know whether they have been effective. Medscape , May 14, 2024

- Rapid Rx Quiz: Tailored Antihypertensive Medications Are you prepared to speak with patients who might be reluctant to take antihypertensive drugs? Find out with this short quiz. Medscape , May 14, 2024

- Severe Ulcerations in Extremities A 50-year-old woman treated for recurrent UTIs has necrotic ulceration of her bilateral upper and lower extremities. A week prior, she developed right wrist drop and left-sided foot drop. What's wrong? Medscape , May 14, 2024

- Fast Five Quiz: Presentation and Treatment of Systemic Amyloidosis Are you up-to-date on the presentation, diagnosis, comorbidities, and treatment associated with the various types of systemic amyloidosis? Find out with this short quiz. Medscape , May 12, 2024

- Fast Five Quiz: Navigating the Complexities of Infective Endocarditis Are you prepared to identify and treat infective endocarditis in patients? Take this short quiz to find out. Medscape , May 06, 2024

- Rapid Review Quiz: Decoding Heart Failure Are you prepared to recognize risk factors and help prevent and manage heart failure in your patients? Test your knowledge with this short quiz. Medscape , May 06, 2024

- Occasional Lightheadedness and Concerning ECG Episodic lightheadedness and an abnormal ECG prompt this 75-year-old woman to be admitted to the hospital. What's going on? Medscape Cardiology , May 03, 2024

- Hematologic Complications After Femoral Fracture Surgery During the course of her postoperative hospital stay, a gradual decline in her platelet count is noted. Medscape , April 19, 2024

- Skill Checkup: A Woman With Severe Heterozygous FH A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman with treated severe heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia presents with uncontrolled cholesterol. How would you manage this patient? Medscape , April 08, 2024

- This Baby Can Hardly Breathe A 10-month-old fussy male infant who is current on his vaccinations is brought to the emergency department in significant respiratory distress. Do you know what's wrong? Medscape , April 12, 2024

- Discolored Toes and Nonhealing Ulcers A 54-year-old woman presents with a 3-year history of red and purple discoloration on her feet and a 2-year history of painful nonhealing ulcers on her toes. Can you make the diagnosis? Medscape , April 09, 2024

- Fact or Fiction: Hereditary Amyloidosis Are you up-to-date on the latest information on hereditary amyloidosis? Test yourself with this quick quiz. Medscape , April 05, 2024

- Chest Pain in a Cancer Patient A 50-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and GERD presents to the ED with chest pain that radiates to his jaw and arm. He started chemotherapy a few days ago. What's causing his symptoms? Medscape , April 05, 2024

- Rapid Review Quiz: Systemic Amyloidosis Are you familiar with the latest information on systemic amyloidosis? Test your knowledge with this quick quiz. Medscape , April 05, 2024

- Why We Need to Know About Our Patients' History of Trauma Adverse childhood experiences can reach all the way into adulthood, resulting in chronic disease. Medscape Family Medicine , April 03, 2024

- Patient Simulation: A 49-Year-Old Man With HIV and CVD Risk A 49-year-old man would like to discuss his medications and manage his comorbidities. How would you advise this patient? Medscape , March 27, 2024

Create Free Account or

- Acute Coronary Syndromes

- Anticoagulation Management

- Arrhythmias and Clinical EP

- Cardiac Surgery

- Cardio-Oncology

- Cardiovascular Care Team

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- COVID-19 Hub

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Dyslipidemia

- Geriatric Cardiology

- Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Noninvasive Imaging

- Pericardial Disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

- Sports and Exercise Cardiology

- Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

- Valvular Heart Disease

- Vascular Medicine

- Clinical Updates & Discoveries

- Advocacy & Policy

- Perspectives & Analysis

- Meeting Coverage

- ACC Member Publications

- ACC Podcasts

- View All Cardiology Updates

- Earn Credit

- View the Education Catalog

- ACC Anywhere: The Cardiology Video Library

- CardioSource Plus for Institutions and Practices

- ECG Drill and Practice

- Heart Songs

- Nuclear Cardiology

- Online Courses

- Collaborative Maintenance Pathway (CMP)

- Understanding MOC

- Image and Slide Gallery

- Annual Scientific Session and Related Events

- Chapter Meetings

- Live Meetings

- Live Meetings - International

- Webinars - Live

- Webinars - OnDemand

- Certificates and Certifications

- ACC Accreditation Services

- ACC Quality Improvement for Institutions Program

- CardioSmart

- National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)

- Advocacy at the ACC

- Cardiology as a Career Path

- Cardiology Careers

- Cardiovascular Buyers Guide

- Clinical Solutions

- Clinician Well-Being Portal

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Innovation Program

- Mobile and Web Apps

Certified Case Series

The Certified E-learning Editorial Board has created several Case Series covering a wide range of topics. These certified cases offer dual CME/MOC credit.

Cardio-oncology Series

Imaging case series, professionalism case series, restrictive cardiomyopathies series, jacc journals on acc.org.

- JACC: Advances

- JACC: Basic to Translational Science

- JACC: CardioOncology

- JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging

- JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions

- JACC: Case Reports

- JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology

- JACC: Heart Failure

- Current Members

- Campaign for the Future

- Become a Member

- Renew Your Membership

- Member Benefits and Resources

- Member Sections

- ACC Member Directory

- ACC Innovation Program

- Our Strategic Direction

- Our History

- Our Bylaws and Code of Ethics

- Leadership and Governance

- Annual Report

- Industry Relations

- Support the ACC

- Jobs at the ACC

- Press Releases

- Social Media

- Book Our Conference Center

Clinical Topics

- Chronic Angina

- Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology

- Diabetes and Cardiometabolic Disease

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Invasive Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Venous Thromboembolism

Latest in Cardiology

Education and meetings.

- Online Learning Catalog

- Products and Resources

- Annual Scientific Session

Tools and Practice Support

- Quality Improvement for Institutions

- Accreditation Services

- Practice Solutions

Heart House

- 2400 N St. NW

- Washington , DC 20037

- Contact Member Care

- Phone: 1-202-375-6000

- Toll Free: 1-800-253-4636

- Fax: 1-202-375-6842

- Media Center

- Advertising & Sponsorship Policy

- Clinical Content Disclaimer

- Editorial Board

- Privacy Policy

- Registered User Agreement

- Terms of Service

- Cookie Policy

© 2024 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 17 September 2024

Brugada syndrome precipitated by uncomplicated malaria treated with dihydroartemisinin piperaquine: a case report

- Muzakkir Amir 1 , 2 ,

- Irmayanti Mukhtar 1 , 2 ,

- Pendrik Tandean 3 &

- Muhammad Zaki Rahmani 1 , 2

Malaria Journal volume 23 , Article number: 283 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Cardiovascular events following anti-malarial treatment are reported infrequently; only a few studies have reported adverse outcomes. This case presentation emphasizes cardiological assessment of Brugada syndrome, presenting as life-threatening arrhythmia during anti-malarial treatment. Without screening and untreated, this disease may lead to sudden cardiac death.

Case presentation

This is a case of 23-year-old male who initially presented with palpitations followed by syncope and shortness of breath with a history of malaria. He had switched treatment from quinine to dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DHP). Further investigations revealed the ST elevation electrocardiogram pattern typical of Brugada syndrome, confirmed with flecainide challenge test . Subsequently, anti-malarial treatment was stopped and an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) was inserted.

Conclusions

Another possible cause of arrhythmic events happened following anti-malarial consumption. This case highlights the possibility of proarrhytmogenic mechanism of malaria infection and anti-malarial drug resulting in typical manifestations of Brugada syndrome.

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is a major cause of cardiac arrest and sudden death in young people with normal heart structure. Arrhythmic manifestations and cardiac arrest in BrS tend to occur in men and populations in Southeast Asian countries [ 1 , 2 ]. Clinical manifestations of BrS can vary from mild discomfort in the form of syncope to sudden death. It is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by ST elevation and negative T waves in right heart electrocardiography (ECG) leads without structural cardiac abnormalities, which occur because of mutations in the cardiac sodium gene SCN5A resulting in loss of cardiac sodium channel function, decreased sodium influx, and depolarization phase shortening of the action potential, which is also associated with sudden cardiac death [ 3 ]. BrS is extremely rare in Southeast Asian and East Asian countries, this may be due to poor reporting or diagnosis resulting from facility limitations, meanwhile Indonesia is endemic for malaria [ 2 , 4 ]. Studies have highlighted the cardiotoxic effects of anti-malarial drugs, particularly piperaquine that has been linked to QT prolongation and sudden cardiac death, emphasizing the need to review their cardiovascular safety profiles [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Very few studies have evaluated the association between anti-malarials and cardiovascular adverse events.

A 23-year-old male came to the emergency unit of Dr. Wahidin General Hospital complaining of palpitations. He described episodes that had occurred approximately 4–5 times in the last 4 months. There was a history of fainting, which was previously preceded by palpitations.

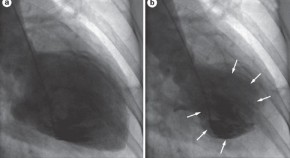

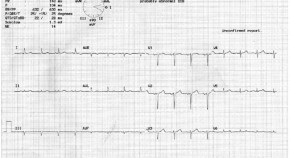

He described atypical chest pain, like being stabbed during the palpitations. There was also a history of fever accompanied by chills. The patient had no family history of the same complaint. The patient had contracted malaria while on duty in Papua 1 year previously and was given quinine therapy. However, the patient subsequently experienced palpitations and tinnitus, so the treatment was stopped, and the patient was switched to DHP (dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine) for 3 days and primaquine for 14 days. The patient was hospitalized again for malaria 8 months later. Since then, the patient is self-medicating with DHP whenever he has fever because it did not resolve after taking fever-reducing medication (Figs. 1 and 2 ).

Baseline ECG shows Type 2 Brugada Pattern in V2 lead

Flecainide Test Result shows Brugada Type 1 Pattern

During the examination, the patient’s heart rate was 64 beats/mins, his respiratory rate was 18 breaths/minute, and his temperature was 36.5 C. Blood pressure was 114/63 mmHg. The patient was neither anaemic nor icteric, JVP R+ 2 cmH2O. Auscultation sounds, including vesicular sounds, rhonchi and wheezing, were absent. Regular heart sounds with no murmur and no oedema were observed. ECG revealed sinus rhythm, a heart rate of 64 beats/minute, normoaxis, a P wave of 0.08 s, a PR interval of 0.16 s, a QRS complex of 0.08 s, a soft curved ST elevation in V1 < 1 mm, saddleback ST elevation in V2 ≥ 2.0 mm, T reversal in V1, a QT interval of 360 ms, and Brugada type 2 pattern in V2. An oral flecainid challenge test (300 mg) performed to confirm the diagnosis of the disease. The test result showed a positive result at the 60th mins, and an image of Brugada pattern type 1 was observed (coved type) in V2 with an ST elevation > 2 mm. The images of the coved type in V1 and V2 were clearer in the right precordial lead position.

Malaria was confirmed with Standareagen rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Complete blood count and electrolytes laboratory shows slight changes (Tables 1 and 2 ), meanwhile echocardiography and chest X-ray results were normal.

The drug treatment was initially stopped and the patient consented to perform ICD implantation. Following ICD implantation, the patient experienced improvement, with no more palpitations felt, and further ECG findings were normal. The patient was discharged from the hospital with no post-ICD events. The malaria treatment then restarted to complete the course.

Brugada syndrome can develop and be triggered by various conditions, such as infection or drugs [ 4 ]. The European Heart Association classified BrS into three subtypes, but only two were prevalent in Asia with type 1 coved subtype being more common than type 2 and mixed type 3, occurring more often in men aged < 40 years [ 8 ]. In this case, the patient was a 23-year old man working in Papua, a region endemic for malaria. According to Fadilah et al. Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax coexist in Papua, and the annual parasite index (API) is greater for men than for women [ 9 ].

ECG features of BrS were diagnosed when a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern of ST segment elevation occurred ≥ 2 mm in at least one right ventricular lead (V1 or V2) spontaneously or after intravenous administration of a sodium ion channel blocker. ECG morphology type 1 is the only pattern that is diagnostically significant for BrS [ 10 ]. In this case, a type 2 Brugada type was obtained in baseline ECG. To confirm this hypothesis, a standard flecanaide provocation test was carried out, an effective alternative when ajmaline was unavailable. After the provocation test, the ECG showed a Brugada type 1 pattern, where the coved ST segment elevation in lead V2 was > 2 mm, followed by a T inversion both in standard ECG lead placement and in the right high lead after one hour [ 11 , 12 ].