An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Noro Psikiyatr Ars

- v.50(3); 2013 Sep

Language: English | Turkish

The Effectiveness of an Interpersonal Cognitive Problem-Solving Strategy on Behavior and Emotional Problems in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity

Kişilerarası sorun Çözme eğitiminin dikkat eksikliği ve hiperaktivite bozukluğu olan Çocukların davranışsal ve emosyonel sorunları Üzerindeki etkisi, celale tangül Özcan.

1 Gulhane Military Medical Academy, School of Nursing, Ankara, Turkey

Fahriye Oflaz

Tümer türkbay.

2 GGulhane Military Medical Academy, Department of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Ankara, Turkey

Sharon M. FREEMAN CLEVENGER

3 Gülhane Indiana/Purdue University Center for Brief Therapy, Fort Wayne, Indiana, USA

Introduction

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the “I Can Problem Solve” (ICPS) program on behavioral and emotional problems in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The subjects were 33 children with ADHD aged between 6 to 11 years. The study used a pre- and post-test quasi-experimental design with one group. The researchers taught 33 children with ADHD how to apply ICPS over a period of 14 weeks. The Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (Teacher Report Form) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) Based Disruptive Behavior Disorders Screening and Rating Scale (parents’ and teacher’s forms) were used to evaluate the efficacy of the program. The scales were applied to parents and teachers of the children before and after the ICPS program.

The findings indicated that the measured pre-training scores for behavioral and emotional problems (attention difficulties, problems, anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, oppositional defiant problems, rule breaking behaviors, and aggressive behaviors) were significantly decreased in all children post-training. In addition, children’s total competence scores increased (working, behaving, learning and happy) after the ICPS program.

According to the results, it is likely that, ICPS would be a useful program to decrease certain behavioral and emotional problems associated with ADHD and to increase the competence level in children with ADHD. An additional benefit of the program might be to empower children to deal with problems associated with ADHD such as attention difficulties, hyperactivity-impulsivity, and oppositional defiant problems.

ÖZET

Giriş.

Bu araştırma dikkat eksikliği hiperaktivite bozukluğu (DEHB) tanısı konulan çocuklara uygulanan bir kişilerarası sorun çözme eğitim programı olan “Ben Sorun Çözebilirim (BSÇ)” eğitiminin etkilerini incelemek amacıyla yapılmıştır.

Yöntemler

Araştırma örneklemini DEHB tanısı konulan 6–11 yaş arası 33 çocuk oluşturmuş, tek gruplu ön-son test deseninde, yarı deneysel olarak planlanmıştır. DEHB tanısı olan bu çocuklara 14 hafta boyunca bilişsel yaklaşıma dayalı BSÇ eğitimi uygulanmıştır. Programın etkinliğini değerlendirmek için “Dikkat Eksikliği ve Yıkıcı Davranış Bozuklukları için DSM-IV’e Dayalı Tarama ve Değerlendirme Ölçeği” (anne-baba ve öğretmen formu) ve “6–18 Yaş Grubu Çocuk ve Gençler için Davranış Değerlendirme Ölçeği (öğretmen formu-TRF/6–18)” kullanılmıştır. BSÇ eğitimi öncesi ve sonrasında anne-baba ve öğretmenlerden bu ölçekleri doldurmaları istenmiştir.

BSÇ eğitimi sonrasında karşı gelme, dikkatsizlik, hiperaktivite/dürtüsellik, anksiyete/depresyon, sosyal içe dönüklük, suça yönelik davranışlar ve saldırgan davranışların azaldığı saptanmıştır. TRF/6–18′nin yeterlilik alanına ilişkin “sıkı çalışma, uyum, öğrenme ve mutlu olma” alt testlerin toplamından oluşan “toplam yeterlilik” alt testinde BSÇ eğitim sonrasında yeterlilik düzeyinin önemli oranda arttığı görülmüştür.

Sonuç

Bu çalışmanın sonuçlarına göre, BSÇ eğitim programı DEHB olan çocukların duygusal ve davranışsal sorunların azaltılmasında ve çocukların yeterlilik düzeylerinin artırılmasında faydalı olabilir. Bu programın bir diğer yararı ise bu çocukların DEHB ile ilişkili sorunlar (dikkat eksikliği, hiperaktivite/dürtüsellik ve karşı gelme sorunları) ile baş etmelerini güçlendirebilir.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is one of the most prevalent childhood psychiatric disorders, is a neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of activity, distractibility, and impulsivity ( 1 , 2 ).

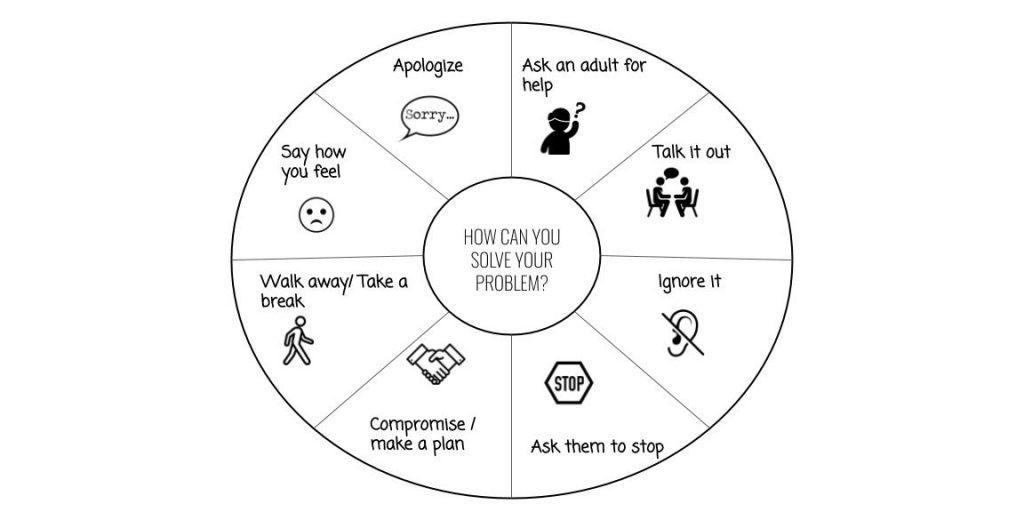

Behavioral problems in children with ADHD include acting without adequate forethought as to the consequences of their actions and inability to postpone gratification with impulsive decisions and behaviors. ADHD negatively influences social interactions with peers, interpersonal relationships with parents, teachers and peers as well as academic success and social functions ( 2 , 3 ). Children with ADHD face problems such as increased incidence of defiant and aggressive behaviors, and are at higher risk of comorbid disorders (such as oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder) compared to typically developing children ( 4 , 5 ). Behavioral problems commonly seen in children with ADHD affect the overall quality of children’s lives ( 2 , 6 , 7 ), and reduce the quality of life of their family members. Specifically, the family experiences overall increased levels of stress, decreased feelings of belonging and competence and disruption of routines and structure ( 2 ). Additional problems include: conflicts and exclusion among peers, inability to manage or prevent anger efficiently, communication/social skill difficulties, inadequate problem solving, and difficulties in relationships ( 2 , 5 , 8 ).

Multifocal treatment programs for children with ADHD may improve outcomes in a more robust manner than medication alone or behavior/cognitive management programs alone. Social skills training programs encourage problem-solving ability and support cognitive and behavioral skills ( 2 , 9 , 10 ). Some cognitive-behavioral approaches consisting of psychosocial treatments result in improved impulse control, increased assessment capability before reaction and enhance considered and tempered actions ( 11 ).

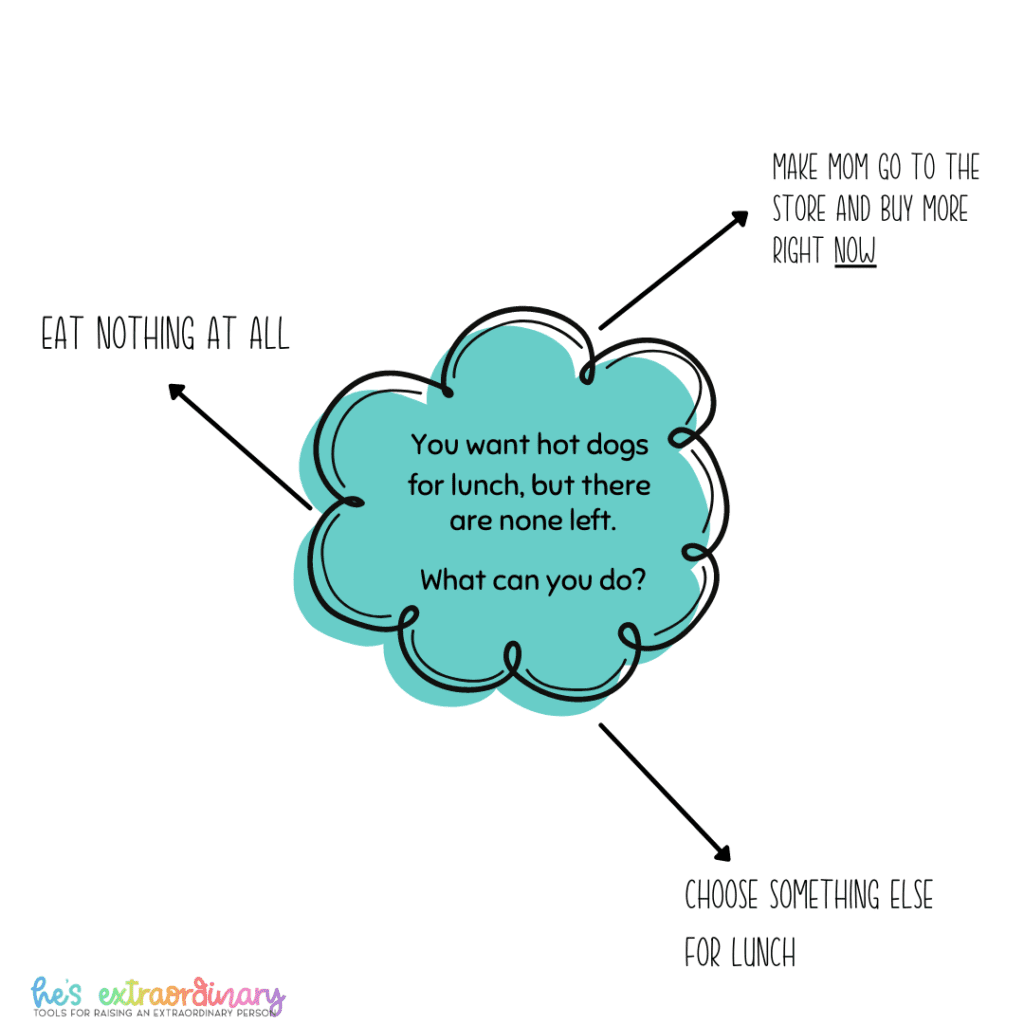

The “I Can Problem Solve” (ICPS) program is based on Interpersonal Cognitive Problem-Solving methods. The basic objectives of this program are developed mainly to deal with the social problems of children ( 12 ). The ICPS is a problem solving approach to prevention of high risk behaviors in children and provide children with assessment abilities to help them solve their problems ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). By strengthening the capacity of children with ADHD to solve problems that lead to socially undesirable behaviors such as physical and verbal aggression, impulsivity, inability to wait, inability to take turns, inability to delay gratification, over emotionality in the face of frustration, inability to maintain friendships, high risk behaviors may be reduced ( 12 ). It should be noted that, children with ADHD need extra support and structured training although other children easily can learn problem-solving skills through these programs and adapt them to real life as well ( 15 ). However, there is limited data relating the ICPS training program for children suffering from ADHD ( 10 , 12 ).

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the ICPS program on children with ADHD. It was hypothesized that ICPS program would be useful to decrease behavioral and emotional problems (oppositional defiant problems, attention problems, hyperactivity problems, anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, rule breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior), and would increase the total competence scores (working, behaving, learning and happy) in children with ADHD.

Study Design and Sampling

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the improvements between pre- and post-ICPS training in measured behavioral and emotional problems in children with ADHD and their competence in term of the effectiveness of the ICPS program. This study was designed as a pre-post-test quasi-experimental design with a single group. The study group consisted of children diagnosed with ADHD in two elementary schools in Ankara/Turkey, between ages of 6 and 11, diagnosed with ADHD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria ( 1 ). The mean age of the participants was 9.1±1.1 years. All of the children were Caucasian. The socio-demographic characteristics of the children such as gender, grade, mother’s and father’s education years, father’s/mother’s profession as well as medication use for ADHD are outlined in Table 1 .

The Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (n=33)

| Gender | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Boy | 30 | 90.9 |

| Girl | 3 | 9.1 |

| Medication | ||

| Medication | 7 | 21.2 |

| No medication | 26 | 78.8 |

| Grade | ||

| First | 3 | 9.1 |

| Second | 7 | 21.2 |

| Third | 8 | 24.2 |

| Fourth | 13 | 39.4 |

| Fifth | 2 | 6.1 |

| Mother’s Education year | ||

| 1–8 year | 25 | 75.8 |

| 9–12 year | 8 | 24.2 |

| 13 year and up | - | - |

| Father’s Education years | ||

| 1–8 year | 19 | 57.5 |

| 9–12 year | 12 | 36.4 |

| 13 year and up | 2 | 6.1 |

| Mother’s Profession | ||

| Housewife | 28 | 84.8 |

| Employed | 5 | 15.2 |

| Father’s Profession | ||

| White Collar | 4 | 12.2 |

| Laborer | 8 | 24.2 |

| Own Job | 21 | 63.6 |

Inclusion criteria were: the diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria, 6 to 12 years of age, and child/parents volunteered for the research. Exclusion criteria were: the history of head trauma or neurological illness, developmental delay or any other axis I psychiatric disorder except for oppositional defiant disorder, making a change in her/his medications during the study if the child has been taking any medication for ADHD, and failure to attend the training.

Instruments

Data collection and assessment tools used in the research were as follows:

The DSM-IV-TR Based Disruptive Behavior Disorders Screening and Rating Scale

This is a screening and assessment instrument, which was developed based on DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria, consists of 9 items inquiring attention problems; 6 items inquiring hyperactivity; 3 items inquiring impulsivity; 8 items inquiring oppositional defiant disorder and 15 items inquiring conduct disorder. The adaptation of this scale to Turkish society, and the validation and reliability analyses were completed in the year 2001. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88 for the sub-scale attention problems and 0.92 for the sub-scale disruptive behavior disorder in the reliability analysis ( 16 ).

The Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (Teacher Report Form-TRF/6–18)

This form was developed to evaluate 6–18 age group students’ adaptation to school and their faulty behavior through information obtained from teachers in a standardized way. TRF includes 118 items related to behavioral and emotional problems. 93 of these items correspond to the items on the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18. The scale provides information regarding adaptation as well as basic functions such as school- and student-related information. In the second part of the scale, behavior problems are inquired under the categories “internalizing” and “externalizing”. Within the “internalizing” category, there are withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints and anxious/depressed subtests, while within the “externalizing” category, there are disobedience to rules and aggressive behaviors sub-tests. There are also sub-tests such as social problems, thought problems, attention problems and other problems that do not belong to either of the two categories ( 17 ). TRF was first developed by Achenbach in 1991, and verification and validation studies in our country were conducted by Erol at al. ( 18 ). The Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the TRF was 0.82 for Internalizing; 0.81 for Externalizing and Cronbach alpha=0.87 for total problem.

The 49 children from two elementary schools were interviewed and examined by a psychiatric practitioner trained in child psychiatry. To exclude other psychiatric disorders, the Children Depression Inventory, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Learning Disorders Checklist were applied. 37 of the 49 children met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD. The study was introduced to 37 children and their parents in an introductory meeting. Permission and written informed consent were obtained from them (n=37). Parent reports were obtained with the DSM-IV-TR based Disruptive Behavior Disorders screening and assessment scale; teacher reports were obtained with both the DSM-IV-TR Based Disruptive Behavior Disorders Screening and Assessment Scale, and “Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (Teacher Report Form)(TRF/6–18).

Due to various reasons, such as being diagnosed with another psychiatric disorder besides ADHD and the failure to attend the training etc., four students were excluded from the study. Finally, the remaining 33 children were taken for evaluation.

The lessons of ICPS were taught to the children in small groups. The children fell into the groups based upon their school and whether they attended morning or afternoon classes resulting in 7–9 children per group. The training program was 14 weeks in length and included 83 structured lessons. Each lesson was completed in approximately 30 minutes twice per week which could be prolonged considering children’s motivation.

The ICPS training program is based on “Interpersonal Cognitive Problem-Solving Strategy”. The ICPS program was developed by Myrna B. Shure (1992) ( 19 ) for purposes of social skills training in children and adolescents. The adaptation of this training to Turkish has been made by Öğülmüş ( 14 ). The training was provided by a primary researcher who had previously been trained exclusively by Öğülmüş. The ICPS program teaches children how to think and how to evaluate their own thoughts. Behaviors are modified by focusing on the thinking processes. The ICPS program encourages children to think about finding as many alternative solutions as possible when they deal with a problem. It teaches children to learn how to think of solutions to a problem and of potential consequences to an act. The ICPS encourages children to do their own thinking instead of offering solutions and consequences ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). ICPS with enhanced critical thinking, creativity, and reasoning skills are concerned more with how a person thinks rather than what a person thinks. ICPS attempt to enhance interpersonal cognitive skills, and thus, lead to successful alterations in overt social behavior ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). The guideline book of ICPS program included 83 structured lessons using pictures, toys, puppets, games, stories, drama, role-plays, and dialogues based on real life conversations. There is a defined goal of each structured lesson in the ICPS program book ( 19 ). The examples of goals of the ICPS lessons are as follows:

To Think About their own Feelings

To learn to identify people’s feelings and to become sensitive to them (other’s feelings) or (to gain the ability to put themselves in other’s shoes)

To increase their awareness that other’s point of view might differ from their own

To recognize that there is more than one way to solve a problem

To learn being assertive without physical and verbal aggression

To learn that different people can feel different ways about the same issue

To think of both alternative solutions and means-ends plans (weighing pros and cons)

To be aware of what might happen next and to learn how to think of solutions to a problem and consequences to an act

To decide for themselves whether their idea was or was not good in the light of their own and others’ feelings and of the possible consequences.

To learn that sensitivity to the preferences of others is also important in deciding what to do in situations which situation?

To increase understanding that thinking about what is happening may, in the long run, be more beneficial than immediate action to stop the behavior

To control impulse, including to delay gratification and to cope with frustrations

Examples of ICPS Dialoguing (Problem-solving process) ( 12 ).

“What happened, what’s the problem, what’s the matter?”

“How do you think she/he feels when.. ?” (e.g., “When you hit him/her?”)

“What happened (might happen) next when you did (do) that?”

“How did that make you feel?”

“Can you think of a different way to solve the problem (tell him/her/me how you feel)?”

“Do you think that is or is not a good idea? Why (why not)?”

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the local ethics committee of Gülhane Military Medical Academy and School of Medicine, and Ankara Provincial Education Directorate. For ethical considerations, the purposes and methods of the study were explained to the children and their parents. After receiving their consent, the study was started.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS Ver. 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. All descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median and number/percentage universal tests, then normal distribution fit tests (Shapiro-Wilk test) were employed for the data used. Pre- and post-test measurement data were evaluated as dependent variables scores were compared by using the Paired-Samples T-Test or the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (when variances are unequal). The significance level was assumed p<0.05.

The differences between pre-and post-training scores were statistically significant for all subscales of the DSM-IV-TR Based Disruptive Behavior Disorders Screening and Rating Scale ( Table 2 ).

Comparison of the Subscales Scores of the DSM-IV-TR Based Disruptive Behavior Disorders Screening and Rating Scale before and after the ICPS Training

| Subscales | Before ICPS Training (n=33) | After ICPS Training (n=33) | Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Z/t | p | |

| Mother’s Rating | ||||||||

| Attention problems | 18.36 | 5.27 | 19.00 | 12.15 | 6.85 | 10.00 | Z=3.99 | <0.001 |

| Hyperactivity-impulsivity | 19.27 | 5.77 | 20.00 | 13.24 | 7.55 | 12.00 | Z=3.96 | <0.001 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 12.70 | 5.87 | 12.00 | 9.03 | 5.30 | 8.00 | Z=3.11 | 0.002 |

| Father’s Rating | ||||||||

| Attention problems | 17.24 | 5.17 | 19.00 | 12.06 | 6.13 | 13.00 | t=4.63 | <0.001 |

| Hyperactivity-impulsivity | 18.79 | 6.34 | 21.00 | 11.60 | 7.43 | 11.00 | Z=4.41 | <0.001 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 12.36 | 4.77 | 11.00 | 8.03 | 4.09 | 7.00 | t=5.50 | <0.001 |

| Teacher’s Rating | ||||||||

| Attention problems | 20.82 | 5.43 | 22.00 | 13.33 | 7.74 | 14.00 | Z=4.39 | <0.001 |

| Hyperactivity-impulsivity | 19.76 | 5.17 | 20.00 | 12.03 | 9.01 | 12.00 | Z=4.14 | <0.001 |

| Oppositional defiant problems | 14.21 | 6.41 | 15.00 | 8.75 | 7.57 | 9.00 | Z=4.16 | <0.001 |

t: Paired-Samples T Test, z: Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test (when variances were unequal),

According to the TRF/6–18 test scores for both pre-and post-training, the all internalizing problem behaviors including “anxious/depressed”, “withdrawn/depressed” and “somatic complaints”, and the all externalizing problem behaviors including “rule-breaking behavior” and “aggressive behaviors” were found to be significantly reduced after the ICPS training ( Table 3 ). The sum of the scores for four adaptive characteristics (“working”, “behaving”, “learning” and “happy”) displays an “adaptive functioning profile” on the TRF/6–18. The difference between competence levels of these sub-tests were found to be statistically significant based on the comparison of these levels for pre- and post-ICPS training (p=0.03). The higher total competence scores indicate the better competence ( Table 3 ).

Comparison of Problematic Behaviors Scores Identified by TRF/6–18 for Pre- and Post-ICPS Training

| TRF/6–18 Problematic Behaviors | Before ICPS Training (n=33) | After ICPS Training (n=33) | Comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Mean | SD | Median | Z/t | p | |

| Internalizing | ||||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 9.09 | 6.75 | 8.00 | 6.63 | 5.02 | 6.00 | Z=2.02 | 0.044* |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 5.36 | 3.84 | 4.00 | 4.15 | 3.34 | 4.00 | Z=2.23 | 0.026* |

| Somatic complaints | 2.15 | 2.30 | 2.00 | 1.03 | 1.59 | 0.00 | Z=2.70 | 0.007* |

| Externalizing | ||||||||

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | 5.58 | 3.72 | 5.00 | 4.30 | 4.17 | 3.00 | Z=2.23 | 0.026* |

| Aggressive Behaviors | 17.27 | 10.03 | 17.00 | 12.75 | 10.62 | 11.00 | Z=3.80 | <0.001 |

| Internalizing (total) | 16.33 | 11.4 | 13.00 | 12.09 | 9.45 | 11.00 | Z=2.29 | 0.022* |

| Externalizing (total) | 22.84 | 13.20 | 24.00 | 17.06 | 14.30 | 15.00 | Z=3.73 | <0.001 |

| Others | ||||||||

| Social problems | 7.85 | 4.33 | 8.00 | 5.27 | 4.39 | 6.00 | Z=4.04 | <0.001 |

| Thought problems | 4.52 | 3.66 | 4.00 | 2.27 | 3.29 | 1.00 | Z=3.17 | 0.002 |

| Attention problems | 30.78 | 10.15 | 33.00 | 24.48 | 13.29 | 25.00 | t=4.02 | <0.001 |

| Other problems | 2.18 | 1.75 | 2.00 | 1.42 | 1.54 | 1.00 | Z=2.19 | 0.029* |

| TRF/6–18 Total | 84.51 | 35.42 | 96.00 | 62.61 | 39.30 | 65.00 | t=4.78 | <0.001 |

| Total Competence | 12.93 | 3.33 | 15.40 | 13.88 | 3.22 | 16.20 | t=2.25 | 0.031* |

t: Paired-Samples T Test, z: Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test (when variances were unequal),

The effectiveness of ICPS training for children with ADHD resulted in significant improvement in ADHD symptoms as well as in such problem areas like internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. These results suggest that ICPS training might reduce problematic behaviors and improve problem-solving skills and behavior among children with ADHD.

Pharmacotherapy tends to be a first-line therapy targeting biological implications for children with ADHD. Approved pharmacological agents for the treatment of ADHD include psychostimulants and atomoxetine. Psychostimulant medication has positive effects on children with ADHD in their ability to focus and pay attention in school settings, thereby, resulting in improvement in the overall learning environment. The therapeutic effects of pharmacological agents may be temporary, as symptom reduction occurs only when medication is active in the system. The lack of long-term efficacy has been issue of concern ( 2 , 20 ). Although the effectiveness of psychostimulants for reducing ADHD symptoms have demonstrated efficacy ( 21 , 22 ), there are potential unwanted side effects of pharmacological agents ( 23 , 24 ). Because of worrying about potential and known/unknown negative effects of pharmacotherapy, some children with ADHD may be reluctant to use any medication for ADHD, and may possibly discontinue medication treatments without their prescribers’ knowledge. Furthermore, follow-up studies have demonstrated that ADHD frequently persists into adolescence and adulthood ( 2 , 25 , 26 ). In addition, adults and those in whom ADHD was diagnosed in childhood often continue to suffer ongoing significant behavior problems ( 2 , 9 , 27 ). Accordingly, if these people with ADHD use a medication as the first and only treatment for ADHD, they will have to use the medication throughout life. As a result, non-pharmacological treatment seeking, and the use of complementary are on the rise ( 26 ). In addition, children with ADHD have not only core ADHD symptoms, but have also comorbid disorders that increase complexity of treatment such as anxiety, disobedience to rules, aggressive behaviors, oppositional defiant behaviors and other social problems ( 2 , 4 ). These comorbid conditions and associated features not only add to ADHD’s clinical complexity, but also have significant implications for treatment ( 28 ). Therefore, alternative options, including psychosocial treatment approaches, may have utility for amelioration of ADHD symptoms, and have significance in reversing the risks and long-term outcomes associated with ADHD, especially if combined with medication ( 3 , 9 , 28 , 29 ). However, some studies indicated that treatment with a combination of medicine and psychosocial treatment has little or no better result compared to medicine only treatment ( 20 , 30 , 31 ). The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) compared four treatment options in a 4-group parallel design. Combination treatment and medication management were both significantly superior to behavioral treatment and community care in reducing the symptoms. In certain conditions (such as oppositional-defiant/aggressive symptoms, internalizing symptoms, teacher rated social skills, parent-child relations, and reading achievement), combined treatment was superior to behavioral treatment and/or community care ( 21 ).

On the contrary, other studies have demonstrated incremental results for adding behavior therapy to psychostimulant medication in terms of reductions of ADHD symptoms ( 32 , 33 ). Similarly, psychosocial interventions such as ICPS have been found to be effective for children with ADHD ( 34 ). In support of this, some studies have reported that, psychosocial therapies provided along with medication had positive effects on comorbid internalizing and externalizing behaviors ( 35 , 36 ). Diller and Goldstein ( 37 ) have emphasized: “more than one hundred studies demonstrate that parent and teacher training programs improve child compliance, reduce disruptive behaviors, and improve parent/teacher-child interactions and a number of short-term studies have scientifically demonstrated the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for ADHD”.

Problem-solving strategies that is one of psychosocial treatments engages both the cognitive and social skills that arise from daily life experiences. Problem-solving skills are considered an important aspect that effects how one reacts and deals with these problems ( 38 ). ICPS program might be useful for both children with and without medication and may contribute to reductions in problematic behaviors. These strategies may also reduce the severity of comorbid disruptive disorders and emotional problems. ICPS training improve problematic behaviors by engaging children in thinking about their actions, the impact of their behavior on themselves and others, the possible consequences of their actions, and other options they have. However, previous studies evaluating the effectiveness of ICPS program in normal children ( 12 , 39 ) concluded that that non-ADHD children with naturally developed problem-solving thinking skills and behavior strategies benefit from ICPS as well as children with ADHD ( 12 , 38 ). There are limited studies related to children with ADHD in the literature to evaluate the effectiveness of ICPS program which we used in our research ( 12 ). In one of the initial studies with single subject design, Shure (1999) has cited that, Aberson (1996) taught ICPS to parents of 3 children with ADHD (12. ??, problem-solving skills and behavior may be improved through the use of ICPS strategies. It is important to recognize that children with ADHD trained in ICPS might learn how to find alternative ways to express their anger, handle anger, and to recognize consequences of their behavior. However, the above mentioned improvement in social and emotional adjustment lasted 4 years after training ended ( 40 ). In another study ( 10 ), also with single subject design, ICPS was conducted to teach 8 children with ADHD who already had been maintaining treatment with psychostimulant drug. While the researcher was teaching ICPS to 8 children with ADHD at an observation class, their mothers observed the ICPS lessons. The mothers applied the learned strategies to their children and used the ICPS dialogs during problem-solving process at home in real-life situations. It was suggested that ICPS program may make an additional contribution into the children treated with a psychostimulant medication to deal with their problems. In parallel with the emphasized idea of the studies ( 12 , 40 ), our data have shown that both ADHD related symptoms and non-ADHD related symptoms were observed to decrease through the use of ICPS strategies.

It was proposed that children with ADHD would need help in learning those skills and the training should be provided in a controlled setting, although normal children might easily learn problem solving skills ( 15 ). Aberson et al. ( 40 ) emphasized that, such initiatives, if applied under special circumstances, could have significant effects on problematic behaviors in children with ADHD. These special conditions were meant for parents to teach their children the skills, and to implement ICPS childrearing techniques altogether; the child learns to internalize the newly acquired skills, and to adapt them to real life. Children with ADHD may need help to generalize and internalize these skills because they could have difficulty to adaptation these skills for a changing environment and generalizing to conditions in real life. In addition, because, rehearsals through games could complement these techniques, during our study, drama and envisaging techniques were used in order to enhance and generalize the acquired skills.

The limitations of this study include: small sample size and the absence of a control group. Other significant limitations of the study could be regarded as not making a comparison with other treatment modalities and, the grading scales used were based on declaration rather than being objective. The present study was planned in a pre-posttest quasi-experimental design with one group. Further research comparing ICPS with other treatment modalities and different factors are needed.

Conclusions

ICPS training based on Interpersonal Problem Solving skills may reduce the level of problems in behaviors of children with ADHD and increase the quality of interpersonal communications. Although American Pediatrics Academy ( 41 ) stated that, psychosocial interventions were found to be effective in treating mild and moderate symptoms of such cases as in the ADHD treatment guidebook published, there is not sufficient evidence for this treatment to be applied alone. Hence, integrated and multimodal treatment approaches may be more convenient hypotheses. ICPS training is relatively easy to learn and to utilize in school settings, and may be conveniently used by most disciplines working with children. Consequently, it is thought that, the ICPS is beneficial training for children with ADHD in order to modify problematic behaviors that interfere with quality of learning, socialization and overall quality of life.

Process of the study

Conflict of interest: The authors reported no conflict of interest related to this article.

Çıkar çatışması: Yazarlar bu makale ile ilgili olarak herhangi bir çıkar çatışması bildirmemişlerdir.

What Is Collaborative Problem Solving and Why Use the Approach?

- First Online: 07 June 2019

Cite this chapter

- J. Stuart Ablon 5

Part of the book series: Current Clinical Psychiatry ((CCPSY))

1618 Accesses

4 Citations

This chapter orients or reorients the reader to the fundamental philosophy and practice of Collaborative Problem Solving. It presents basic information about effectiveness of the approach across different settings and provides a rationale for this volume as a resource for individuals looking to implement CPS organization-wide.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Collaborative Problem Solving Tasks

A discussion of the cognitive load in collaborative problem-solving.

Identifying collaborative problem-solver profiles based on collaborative processing time, actions and skills on a computer-based task

Abel MH, Sewell J. Stress and burnout in rural and urban secondary school teachers. J Educ Res. 1999;92(5):287–93.

Article Google Scholar

Fixsen D, Naoom S, Blase K, Friedman R, Wallace F. Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. Tamps: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network; 2005.

Google Scholar

Greene RW. The explosive child: a new approach for understanding and parenting easily frustrated, chronically inflexible children. New York: Harper Collins; 1998.

Greene RW, Ablon JS. Treating explosive kids: the collaborative problem solving approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2005.

Greene RW, Ablon JS, Goring JC, Raezer-Blakely L, Markey J, Monuteaux MC, Rabbitt S. Effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in affectively dysregulated children with oppositional-defiant disorder: initial findings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1157.

Greene RW, Ablon JS, Martin A. Use of collaborative problem solving to reduce seclusion and restraint in child and adolescent inpatient units. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(5):610–2.

Hone M, Tatartcheff-Quesnel N. System-wide implementation of collaborative problem solving: practical considerations for success. Paper presented at the 30th Annual Child, Adolescent & Young Adult Behavioral Health Research and Policy Conference, March, Tampa; 2017.

Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(12):1468–84.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Martin A, Krieg H, Esposito F, Stubbe D, Cardona L. Reduction of restraint and seclusion through collaborative problem solving: a five-year prospective inpatient study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(12):1406–12.

Perry BD. The neurosequential model of therapeutics: applying principles of neuroscience to clinical work with traumatized and maltreated children. In: Working with traumatized youth in child welfare. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. p. 27–52.

Pollastri AR, Epstein LD, Heath GH, Ablon JS. The collaborative problem solving approach: outcomes across settings. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):188–99.

PubMed Google Scholar

Pollastri AR, Lieberman RE, Boldt SL, Ablon JS. Minimizing seclusion and restraint in youth residential and day treatment through site-wide implementation of collaborative problem solving. Resid Treat Child Youth. 2016;33(3–4):186–205.

Schaubman A, Stetson E, Plog A. Reducing teacher stress by implementing collaborative problem solving in a school setting. Sch Soc Work J. 2011;35(2):72–93.

Stetson EA, Plog AE. Collaborative problem solving in schools: results of a year-long consultation project. Sch Soc Work J. 2016;40(2):17–36.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Think:Kids Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

J. Stuart Ablon

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to J. Stuart Ablon .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Alisha R. Pollastri

Crossroads Children’s Mental Health Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Michael J.G. Hone

Electronic Supplementary Material

Watch as Dr. J. Stuart Ablon, Director of Think:Kids, introduces the overarching philosophy behind Collaborative Problem Solving, which forms the foundation for the entire approach (MP4 509324 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ablon, J.S. (2019). What Is Collaborative Problem Solving and Why Use the Approach?. In: Pollastri, A., Ablon, J., Hone, M. (eds) Collaborative Problem Solving. Current Clinical Psychiatry. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12630-8_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12630-8_1

Published : 07 June 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-12629-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-12630-8

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2023

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: A meta-analysis based on empirical literature

- Enwei Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6424-8169 1 ,

- Wei Wang 1 &

- Qingxia Wang 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 16 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

21 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely embraced in the classroom instruction of critical thinking, which is regarded as the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education as well as a key competence for learners in the 21st century. However, the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking remains uncertain. This current research presents the major findings of a meta-analysis of 36 pieces of the literature revealed in worldwide educational periodicals during the 21st century to identify the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and to determine, based on evidence, whether and to what extent collaborative problem solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students’ critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]); (2) in respect to the dimensions of critical thinking, collaborative problem solving can significantly and successfully enhance students’ attitudinal tendencies (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.87, 1.47]); nevertheless, it falls short in terms of improving students’ cognitive skills, having only an upper-middle impact (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI[0.58, 0.82]); and (3) the teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), and learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01) all have an impact on critical thinking, and they can be viewed as important moderating factors that affect how critical thinking develops. On the basis of these results, recommendations are made for further study and instruction to better support students’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Similar content being viewed by others

A meta-analysis of the effects of design thinking on student learning

Fostering twenty-first century skills among primary school students through math project-based learning

A meta-analysis to gauge the impact of pedagogies employed in mixed-ability high school biology classrooms

Introduction.

Although critical thinking has a long history in research, the concept of critical thinking, which is regarded as an essential competence for learners in the 21st century, has recently attracted more attention from researchers and teaching practitioners (National Research Council, 2012 ). Critical thinking should be the core of curriculum reform based on key competencies in the field of education (Peng and Deng, 2017 ) because students with critical thinking can not only understand the meaning of knowledge but also effectively solve practical problems in real life even after knowledge is forgotten (Kek and Huijser, 2011 ). The definition of critical thinking is not universal (Ennis, 1989 ; Castle, 2009 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). In general, the definition of critical thinking is a self-aware and self-regulated thought process (Facione, 1990 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). It refers to the cognitive skills needed to interpret, analyze, synthesize, reason, and evaluate information as well as the attitudinal tendency to apply these abilities (Halpern, 2001 ). The view that critical thinking can be taught and learned through curriculum teaching has been widely supported by many researchers (e.g., Kuncel, 2011 ; Leng and Lu, 2020 ), leading to educators’ efforts to foster it among students. In the field of teaching practice, there are three types of courses for teaching critical thinking (Ennis, 1989 ). The first is an independent curriculum in which critical thinking is taught and cultivated without involving the knowledge of specific disciplines; the second is an integrated curriculum in which critical thinking is integrated into the teaching of other disciplines as a clear teaching goal; and the third is a mixed curriculum in which critical thinking is taught in parallel to the teaching of other disciplines for mixed teaching training. Furthermore, numerous measuring tools have been developed by researchers and educators to measure critical thinking in the context of teaching practice. These include standardized measurement tools, such as WGCTA, CCTST, CCTT, and CCTDI, which have been verified by repeated experiments and are considered effective and reliable by international scholars (Facione and Facione, 1992 ). In short, descriptions of critical thinking, including its two dimensions of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, different types of teaching courses, and standardized measurement tools provide a complex normative framework for understanding, teaching, and evaluating critical thinking.

Cultivating critical thinking in curriculum teaching can start with a problem, and one of the most popular critical thinking instructional approaches is problem-based learning (Liu et al., 2020 ). Duch et al. ( 2001 ) noted that problem-based learning in group collaboration is progressive active learning, which can improve students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Collaborative problem-solving is the organic integration of collaborative learning and problem-based learning, which takes learners as the center of the learning process and uses problems with poor structure in real-world situations as the starting point for the learning process (Liang et al., 2017 ). Students learn the knowledge needed to solve problems in a collaborative group, reach a consensus on problems in the field, and form solutions through social cooperation methods, such as dialogue, interpretation, questioning, debate, negotiation, and reflection, thus promoting the development of learners’ domain knowledge and critical thinking (Cindy, 2004 ; Liang et al., 2017 ).

Collaborative problem-solving has been widely used in the teaching practice of critical thinking, and several studies have attempted to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature on critical thinking from various perspectives. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of collaborative problem-solving on critical thinking. Therefore, the best approach for developing and enhancing critical thinking throughout collaborative problem-solving is to examine how to implement critical thinking instruction; however, this issue is still unexplored, which means that many teachers are incapable of better instructing critical thinking (Leng and Lu, 2020 ; Niu et al., 2013 ). For example, Huber ( 2016 ) provided the meta-analysis findings of 71 publications on gaining critical thinking over various time frames in college with the aim of determining whether critical thinking was truly teachable. These authors found that learners significantly improve their critical thinking while in college and that critical thinking differs with factors such as teaching strategies, intervention duration, subject area, and teaching type. The usefulness of collaborative problem-solving in fostering students’ critical thinking, however, was not determined by this study, nor did it reveal whether there existed significant variations among the different elements. A meta-analysis of 31 pieces of educational literature was conducted by Liu et al. ( 2020 ) to assess the impact of problem-solving on college students’ critical thinking. These authors found that problem-solving could promote the development of critical thinking among college students and proposed establishing a reasonable group structure for problem-solving in a follow-up study to improve students’ critical thinking. Additionally, previous empirical studies have reached inconclusive and even contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent collaborative problem-solving increases or decreases critical thinking levels. As an illustration, Yang et al. ( 2008 ) carried out an experiment on the integrated curriculum teaching of college students based on a web bulletin board with the goal of fostering participants’ critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These authors’ research revealed that through sharing, debating, examining, and reflecting on various experiences and ideas, collaborative problem-solving can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking in real-life problem situations. In contrast, collaborative problem-solving had a positive impact on learners’ interaction and could improve learning interest and motivation but could not significantly improve students’ critical thinking when compared to traditional classroom teaching, according to research by Naber and Wyatt ( 2014 ) and Sendag and Odabasi ( 2009 ) on undergraduate and high school students, respectively.

The above studies show that there is inconsistency regarding the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough and trustworthy review to detect and decide whether and to what degree collaborative problem-solving can result in a rise or decrease in critical thinking. Meta-analysis is a quantitative analysis approach that is utilized to examine quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. This approach characterizes the effectiveness of its impact by averaging the effect sizes of numerous qualitative studies in an effort to reduce the uncertainty brought on by independent research and produce more conclusive findings (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ).

This paper used a meta-analytic approach and carried out a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking in order to make a contribution to both research and practice. The following research questions were addressed by this meta-analysis:

What is the overall effect size of collaborative problem-solving in promoting students’ critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills)?

How are the disparities between the study conclusions impacted by various moderating variables if the impacts of various experimental designs in the included studies are heterogeneous?

This research followed the strict procedures (e.g., database searching, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s ( 2010 ) proposed meta-analysis approach for examining quantitative data from various separate studies that are all focused on the same research topic. The relevant empirical research that appeared in worldwide educational periodicals within the 21st century was subjected to this meta-analysis using Rev-Man 5.4. The consistency of the data extracted separately by two researchers was tested using Cohen’s kappa coefficient, and a publication bias test and a heterogeneity test were run on the sample data to ascertain the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

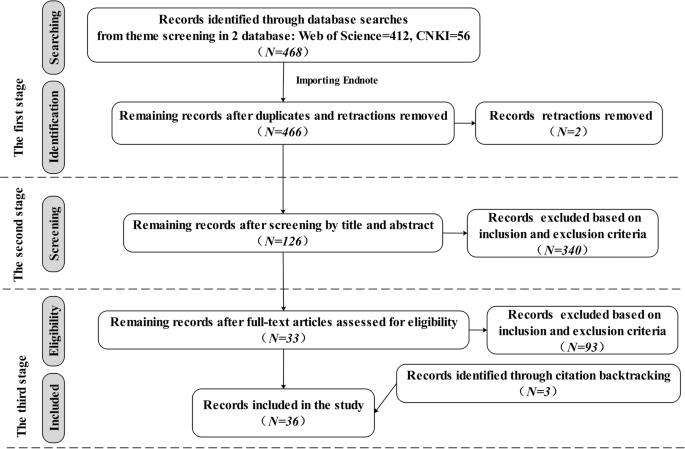

There were three stages to the data collection process for this meta-analysis, as shown in Fig. 1 , which shows the number of articles included and eliminated during the selection process based on the statement and study eligibility criteria.

This flowchart shows the number of records identified, included and excluded in the article.

First, the databases used to systematically search for relevant articles were the journal papers of the Web of Science Core Collection and the Chinese Core source journal, as well as the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI. These databases were selected because they are credible platforms that are sources of scholarly and peer-reviewed information with advanced search tools and contain literature relevant to the subject of our topic from reliable researchers and experts. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the Web of Science was “TS = (((“critical thinking” or “ct” and “pretest” or “posttest”) or (“critical thinking” or “ct” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”)) and (“collaboration” or “collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“problem solving” or “problem-based learning” or “PBL”))”. The research area was “Education Educational Research”, and the search period was “January 1, 2000, to December 30, 2021”. A total of 412 papers were obtained. The search string with the Boolean operator used in the CNKI was “SU = (‘critical thinking’*‘collaboration’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘collaborative learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘CSCL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem solving’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem-based learning’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘PBL’ + ‘critical thinking’*‘problem oriented’) AND FT = (‘experiment’ + ‘quasi experiment’ + ‘pretest’ + ‘posttest’ + ‘empirical study’)” (translated into Chinese when searching). A total of 56 studies were found throughout the search period of “January 2000 to December 2021”. From the databases, all duplicates and retractions were eliminated before exporting the references into Endnote, a program for managing bibliographic references. In all, 466 studies were found.

Second, the studies that matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were chosen by two researchers after they had reviewed the abstracts and titles of the gathered articles, yielding a total of 126 studies.

Third, two researchers thoroughly reviewed each included article’s whole text in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Meanwhile, a snowball search was performed using the references and citations of the included articles to ensure complete coverage of the articles. Ultimately, 36 articles were kept.

Two researchers worked together to carry out this entire process, and a consensus rate of almost 94.7% was reached after discussion and negotiation to clarify any emerging differences.

Eligibility criteria

Since not all the retrieved studies matched the criteria for this meta-analysis, eligibility criteria for both inclusion and exclusion were developed as follows:

The publication language of the included studies was limited to English and Chinese, and the full text could be obtained. Articles that did not meet the publication language and articles not published between 2000 and 2021 were excluded.

The research design of the included studies must be empirical and quantitative studies that can assess the effect of collaborative problem-solving on the development of critical thinking. Articles that could not identify the causal mechanisms by which collaborative problem-solving affects critical thinking, such as review articles and theoretical articles, were excluded.

The research method of the included studies must feature a randomized control experiment or a quasi-experiment, or a natural experiment, which have a higher degree of internal validity with strong experimental designs and can all plausibly provide evidence that critical thinking and collaborative problem-solving are causally related. Articles with non-experimental research methods, such as purely correlational or observational studies, were excluded.

The participants of the included studies were only students in school, including K-12 students and college students. Articles in which the participants were non-school students, such as social workers or adult learners, were excluded.

The research results of the included studies must mention definite signs that may be utilized to gauge critical thinking’s impact (e.g., sample size, mean value, or standard deviation). Articles that lacked specific measurement indicators for critical thinking and could not calculate the effect size were excluded.

Data coding design

In order to perform a meta-analysis, it is necessary to collect the most important information from the articles, codify that information’s properties, and convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Therefore, this study designed a data coding template (see Table 1 ). Ultimately, 16 coding fields were retained.

The designed data-coding template consisted of three pieces of information. Basic information about the papers was included in the descriptive information: the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper.

The variable information for the experimental design had three variables: the independent variable (instruction method), the dependent variable (critical thinking), and the moderating variable (learning stage, teaching type, intervention duration, learning scaffold, group size, measuring tool, and subject area). Depending on the topic of this study, the intervention strategy, as the independent variable, was coded into collaborative and non-collaborative problem-solving. The dependent variable, critical thinking, was coded as a cognitive skill and an attitudinal tendency. And seven moderating variables were created by grouping and combining the experimental design variables discovered within the 36 studies (see Table 1 ), where learning stages were encoded as higher education, high school, middle school, and primary school or lower; teaching types were encoded as mixed courses, integrated courses, and independent courses; intervention durations were encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; group sizes were encoded as 2–3 persons, 4–6 persons, 7–10 persons, and more than 10 persons; learning scaffolds were encoded as teacher-supported learning scaffold, technique-supported learning scaffold, and resource-supported learning scaffold; measuring tools were encoded as standardized measurement tools (e.g., WGCTA, CCTT, CCTST, and CCTDI) and self-adapting measurement tools (e.g., modified or made by researchers); and subject areas were encoded according to the specific subjects used in the 36 included studies.

The data information contained three metrics for measuring critical thinking: sample size, average value, and standard deviation. It is vital to remember that studies with various experimental designs frequently adopt various formulas to determine the effect size. And this paper used Morris’ proposed standardized mean difference (SMD) calculation formula ( 2008 , p. 369; see Supplementary Table S3 ).

Procedure for extracting and coding data

According to the data coding template (see Table 1 ), the 36 papers’ information was retrieved by two researchers, who then entered them into Excel (see Supplementary Table S1 ). The results of each study were extracted separately in the data extraction procedure if an article contained numerous studies on critical thinking, or if a study assessed different critical thinking dimensions. For instance, Tiwari et al. ( 2010 ) used four time points, which were viewed as numerous different studies, to examine the outcomes of critical thinking, and Chen ( 2013 ) included the two outcome variables of attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills, which were regarded as two studies. After discussion and negotiation during data extraction, the two researchers’ consistency test coefficients were roughly 93.27%. Supplementary Table S2 details the key characteristics of the 36 included articles with 79 effect quantities, including descriptive information (e.g., the publishing year, author, serial number, and title of the paper), variable information (e.g., independent variables, dependent variables, and moderating variables), and data information (e.g., mean values, standard deviations, and sample size). Following that, testing for publication bias and heterogeneity was done on the sample data using the Rev-Man 5.4 software, and then the test results were used to conduct a meta-analysis.

Publication bias test

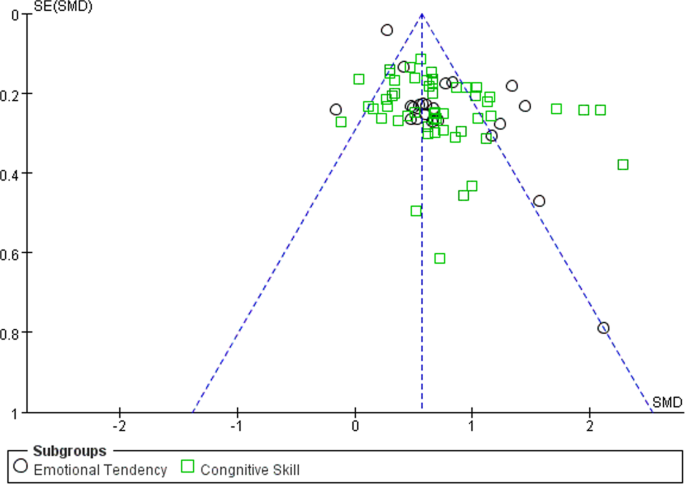

When the sample of studies included in a meta-analysis does not accurately reflect the general status of research on the relevant subject, publication bias is said to be exhibited in this research. The reliability and accuracy of the meta-analysis may be impacted by publication bias. Due to this, the meta-analysis needs to check the sample data for publication bias (Stewart et al., 2006 ). A popular method to check for publication bias is the funnel plot; and it is unlikely that there will be publishing bias when the data are equally dispersed on either side of the average effect size and targeted within the higher region. The data are equally dispersed within the higher portion of the efficient zone, consistent with the funnel plot connected with this analysis (see Fig. 2 ), indicating that publication bias is unlikely in this situation.

This funnel plot shows the result of publication bias of 79 effect quantities across 36 studies.

Heterogeneity test

To select the appropriate effect models for the meta-analysis, one might use the results of a heterogeneity test on the data effect sizes. In a meta-analysis, it is common practice to gauge the degree of data heterogeneity using the I 2 value, and I 2 ≥ 50% is typically understood to denote medium-high heterogeneity, which calls for the adoption of a random effect model; if not, a fixed effect model ought to be applied (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001 ). The findings of the heterogeneity test in this paper (see Table 2 ) revealed that I 2 was 86% and displayed significant heterogeneity ( P < 0.01). To ensure accuracy and reliability, the overall effect size ought to be calculated utilizing the random effect model.

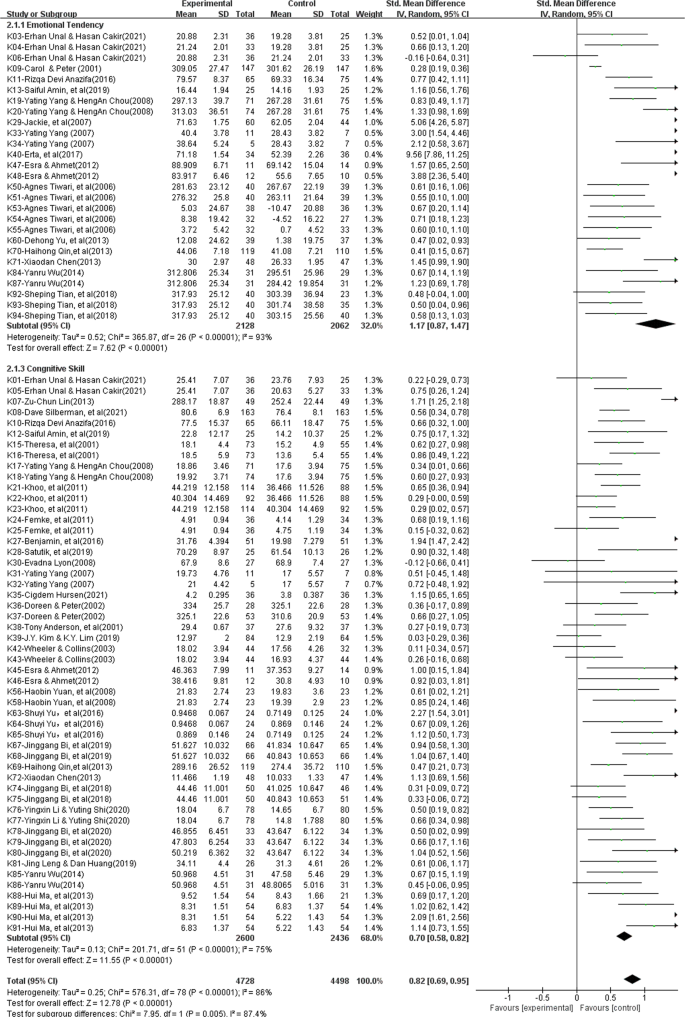

The analysis of the overall effect size

This meta-analysis utilized a random effect model to examine 79 effect quantities from 36 studies after eliminating heterogeneity. In accordance with Cohen’s criterion (Cohen, 1992 ), it is abundantly clear from the analysis results, which are shown in the forest plot of the overall effect (see Fig. 3 ), that the cumulative impact size of cooperative problem-solving is 0.82, which is statistically significant ( z = 12.78, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]), and can encourage learners to practice critical thinking.

This forest plot shows the analysis result of the overall effect size across 36 studies.

In addition, this study examined two distinct dimensions of critical thinking to better understand the precise contributions that collaborative problem-solving makes to the growth of critical thinking. The findings (see Table 3 ) indicate that collaborative problem-solving improves cognitive skills (ES = 0.70) and attitudinal tendency (ES = 1.17), with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.95, P < 0.01). Although collaborative problem-solving improves both dimensions of critical thinking, it is essential to point out that the improvements in students’ attitudinal tendency are much more pronounced and have a significant comprehensive effect (ES = 1.17, z = 7.62, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.87, 1.47]), whereas gains in learners’ cognitive skill are slightly improved and are just above average. (ES = 0.70, z = 11.55, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]).

The analysis of moderator effect size

The whole forest plot’s 79 effect quantities underwent a two-tailed test, which revealed significant heterogeneity ( I 2 = 86%, z = 12.78, P < 0.01), indicating differences between various effect sizes that may have been influenced by moderating factors other than sampling error. Therefore, exploring possible moderating factors that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis, such as the learning stage, learning scaffold, teaching type, group size, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, in order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking. The findings (see Table 4 ) indicate that various moderating factors have advantageous effects on critical thinking. In this situation, the subject area (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05), group size (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05), intervention duration (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01), learning scaffold (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01), and teaching type (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05) are all significant moderators that can be applied to support the cultivation of critical thinking. However, since the learning stage and the measuring tools did not significantly differ among intergroup (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05, and chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05), we are unable to explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving. These are the precise outcomes, as follows:

Various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively, without significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 3.15, P = 0.21 > 0.05). High school was first on the list of effect sizes (ES = 1.36, P < 0.01), then higher education (ES = 0.78, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.73, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the learning stage’s beneficial influence on cultivating learners’ critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is essential for cultivating critical thinking in the context of collaborative problem-solving.

Different teaching types had varying degrees of positive impact on critical thinking, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 7.20, P < 0.05). The effect size was ranked as follows: mixed courses (ES = 1.34, P < 0.01), integrated courses (ES = 0.81, P < 0.01), and independent courses (ES = 0.27, P < 0.01). These results indicate that the most effective approach to cultivate critical thinking utilizing collaborative problem solving is through the teaching type of mixed courses.

Various intervention durations significantly improved critical thinking, and there were significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 12.18, P < 0.01). The effect sizes related to this variable showed a tendency to increase with longer intervention durations. The improvement in critical thinking reached a significant level (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) after more than 12 weeks of training. These findings indicate that the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated, with a longer intervention duration having a greater effect.

Different learning scaffolds influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 9.03, P < 0.01). The resource-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.69, P < 0.01) acquired a medium-to-higher level of impact, the technique-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.63, P < 0.01) also attained a medium-to-higher level of impact, and the teacher-supported learning scaffold (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01) displayed a high level of significant impact. These results show that the learning scaffold with teacher support has the greatest impact on cultivating critical thinking.

Various group sizes influenced critical thinking positively, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 8.77, P < 0.05). Critical thinking showed a general declining trend with increasing group size. The overall effect size of 2–3 people in this situation was the biggest (ES = 0.99, P < 0.01), and when the group size was greater than 7 people, the improvement in critical thinking was at the lower-middle level (ES < 0.5, P < 0.01). These results show that the impact on critical thinking is positively connected with group size, and as group size grows, so does the overall impact.

Various measuring tools influenced critical thinking positively, with significant intergroup differences (chi 2 = 0.08, P = 0.78 > 0.05). In this situation, the self-adapting measurement tools obtained an upper-medium level of effect (ES = 0.78), whereas the complete effect size of the standardized measurement tools was the largest, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.84, P < 0.01). These results show that, despite the beneficial influence of the measuring tool on cultivating critical thinking, we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

Different subject areas had a greater impact on critical thinking, and the intergroup differences were statistically significant (chi 2 = 13.36, P < 0.05). Mathematics had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 1.68, P < 0.01), followed by science (ES = 1.25, P < 0.01) and medical science (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Programming technology was the least effective (ES = 0.39, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to education (ES = 0.72, P < 0.01) and other fields (such as language, art, and social sciences) (ES = 0.58, P < 0.01). These results suggest that scientific fields (e.g., mathematics, science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

According to this meta-analysis, using collaborative problem-solving as an intervention strategy in critical thinking teaching has a considerable amount of impact on cultivating learners’ critical thinking as a whole and has a favorable promotional effect on the two dimensions of critical thinking. According to certain studies, collaborative problem solving, the most frequently used critical thinking teaching strategy in curriculum instruction can considerably enhance students’ critical thinking (e.g., Liang et al., 2017 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Cindy, 2004 ). This meta-analysis provides convergent data support for the above research views. Thus, the findings of this meta-analysis not only effectively address the first research query regarding the overall effect of cultivating critical thinking and its impact on the two dimensions of critical thinking (i.e., attitudinal tendency and cognitive skills) utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving, but also enhance our confidence in cultivating critical thinking by using collaborative problem-solving intervention approach in the context of classroom teaching.

Furthermore, the associated improvements in attitudinal tendency are much stronger, but the corresponding improvements in cognitive skill are only marginally better. According to certain studies, cognitive skill differs from the attitudinal tendency in classroom instruction; the cultivation and development of the former as a key ability is a process of gradual accumulation, while the latter as an attitude is affected by the context of the teaching situation (e.g., a novel and exciting teaching approach, challenging and rewarding tasks) (Halpern, 2001 ; Wei and Hong, 2022 ). Collaborative problem-solving as a teaching approach is exciting and interesting, as well as rewarding and challenging; because it takes the learners as the focus and examines problems with poor structure in real situations, and it can inspire students to fully realize their potential for problem-solving, which will significantly improve their attitudinal tendency toward solving problems (Liu et al., 2020 ). Similar to how collaborative problem-solving influences attitudinal tendency, attitudinal tendency impacts cognitive skill when attempting to solve a problem (Liu et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ), and stronger attitudinal tendencies are associated with improved learning achievement and cognitive ability in students (Sison, 2008 ; Zhang et al., 2022 ). It can be seen that the two specific dimensions of critical thinking as well as critical thinking as a whole are affected by collaborative problem-solving, and this study illuminates the nuanced links between cognitive skills and attitudinal tendencies with regard to these two dimensions of critical thinking. To fully develop students’ capacity for critical thinking, future empirical research should pay closer attention to cognitive skills.

The moderating effects of collaborative problem solving with regard to teaching critical thinking

In order to further explore the key factors that influence critical thinking, exploring possible moderating effects that might produce considerable heterogeneity was done using subgroup analysis. The findings show that the moderating factors, such as the teaching type, learning stage, group size, learning scaffold, duration of the intervention, measuring tool, and the subject area included in the 36 experimental designs, could all support the cultivation of collaborative problem-solving in critical thinking. Among them, the effect size differences between the learning stage and measuring tool are not significant, which does not explain why these two factors are crucial in supporting the cultivation of critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of the learning stage, various learning stages influenced critical thinking positively without significant intergroup differences, indicating that we are unable to explain why it is crucial in fostering the growth of critical thinking.

Although high education accounts for 70.89% of all empirical studies performed by researchers, high school may be the appropriate learning stage to foster students’ critical thinking by utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving since it has the largest overall effect size. This phenomenon may be related to student’s cognitive development, which needs to be further studied in follow-up research.

With regard to teaching type, mixed course teaching may be the best teaching method to cultivate students’ critical thinking. Relevant studies have shown that in the actual teaching process if students are trained in thinking methods alone, the methods they learn are isolated and divorced from subject knowledge, which is not conducive to their transfer of thinking methods; therefore, if students’ thinking is trained only in subject teaching without systematic method training, it is challenging to apply to real-world circumstances (Ruggiero, 2012 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Teaching critical thinking as mixed course teaching in parallel to other subject teachings can achieve the best effect on learners’ critical thinking, and explicit critical thinking instruction is more effective than less explicit critical thinking instruction (Bensley and Spero, 2014 ).

In terms of the intervention duration, with longer intervention times, the overall effect size shows an upward tendency. Thus, the intervention duration and critical thinking’s impact are positively correlated. Critical thinking, as a key competency for students in the 21st century, is difficult to get a meaningful improvement in a brief intervention duration. Instead, it could be developed over a lengthy period of time through consistent teaching and the progressive accumulation of knowledge (Halpern, 2001 ; Hu and Liu, 2015 ). Therefore, future empirical studies ought to take these restrictions into account throughout a longer period of critical thinking instruction.

With regard to group size, a group size of 2–3 persons has the highest effect size, and the comprehensive effect size decreases with increasing group size in general. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a group composed of two to four members is most appropriate for collaborative learning (Schellens and Valcke, 2006 ). However, the meta-analysis results also indicate that once the group size exceeds 7 people, small groups cannot produce better interaction and performance than large groups. This may be because the learning scaffolds of technique support, resource support, and teacher support improve the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members, and a collaborative group with more members may increase the diversity of views, which is helpful to cultivate critical thinking utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

With regard to the learning scaffold, the three different kinds of learning scaffolds can all enhance critical thinking. Among them, the teacher-supported learning scaffold has the largest overall effect size, demonstrating the interdependence of effective learning scaffolds and collaborative problem-solving. This outcome is in line with some research findings; as an example, a successful strategy is to encourage learners to collaborate, come up with solutions, and develop critical thinking skills by using learning scaffolds (Reiser, 2004 ; Xu et al., 2022 ); learning scaffolds can lower task complexity and unpleasant feelings while also enticing students to engage in learning activities (Wood et al., 2006 ); learning scaffolds are designed to assist students in using learning approaches more successfully to adapt the collaborative problem-solving process, and the teacher-supported learning scaffolds have the greatest influence on critical thinking in this process because they are more targeted, informative, and timely (Xu et al., 2022 ).

With respect to the measuring tool, despite the fact that standardized measurement tools (such as the WGCTA, CCTT, and CCTST) have been acknowledged as trustworthy and effective by worldwide experts, only 54.43% of the research included in this meta-analysis adopted them for assessment, and the results indicated no intergroup differences. These results suggest that not all teaching circumstances are appropriate for measuring critical thinking using standardized measurement tools. “The measuring tools for measuring thinking ability have limits in assessing learners in educational situations and should be adapted appropriately to accurately assess the changes in learners’ critical thinking.”, according to Simpson and Courtney ( 2002 , p. 91). As a result, in order to more fully and precisely gauge how learners’ critical thinking has evolved, we must properly modify standardized measuring tools based on collaborative problem-solving learning contexts.

With regard to the subject area, the comprehensive effect size of science departments (e.g., mathematics, science, medical science) is larger than that of language arts and social sciences. Some recent international education reforms have noted that critical thinking is a basic part of scientific literacy. Students with scientific literacy can prove the rationality of their judgment according to accurate evidence and reasonable standards when they face challenges or poorly structured problems (Kyndt et al., 2013 ), which makes critical thinking crucial for developing scientific understanding and applying this understanding to practical problem solving for problems related to science, technology, and society (Yore et al., 2007 ).

Suggestions for critical thinking teaching

Other than those stated in the discussion above, the following suggestions are offered for critical thinking instruction utilizing the approach of collaborative problem-solving.

First, teachers should put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, to design real problems based on collaborative situations. This meta-analysis provides evidence to support the view that collaborative problem-solving has a strong synergistic effect on promoting students’ critical thinking. Asking questions about real situations and allowing learners to take part in critical discussions on real problems during class instruction are key ways to teach critical thinking rather than simply reading speculative articles without practice (Mulnix, 2012 ). Furthermore, the improvement of students’ critical thinking is realized through cognitive conflict with other learners in the problem situation (Yang et al., 2008 ). Consequently, it is essential for teachers to put a special emphasis on the two core elements, which are collaboration and problem-solving, and design real problems and encourage students to discuss, negotiate, and argue based on collaborative problem-solving situations.