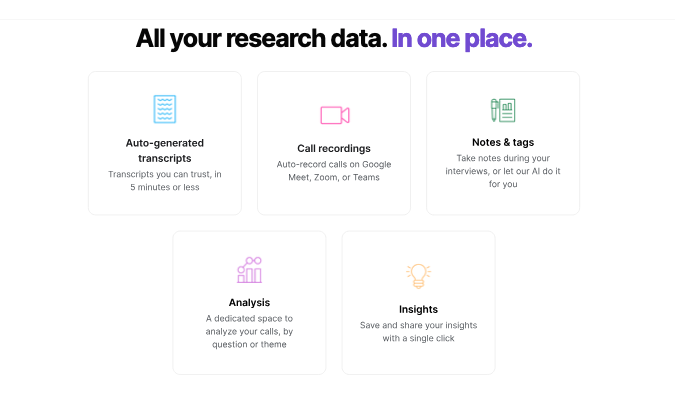

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

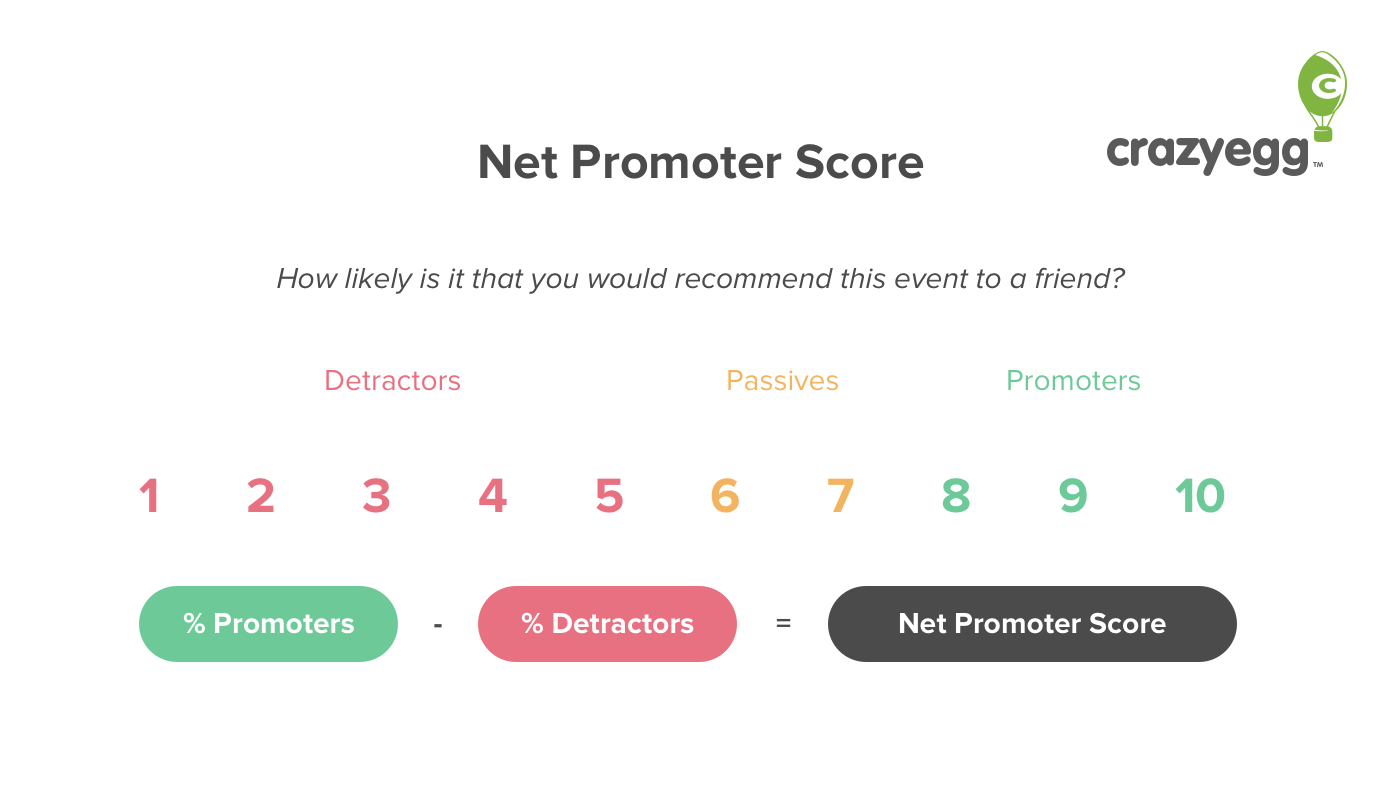

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Qualitative Research Questions

Try Qualtrics for free

How to write qualitative research questions.

11 min read Here’s how to write effective qualitative research questions for your projects, and why getting it right matters so much.

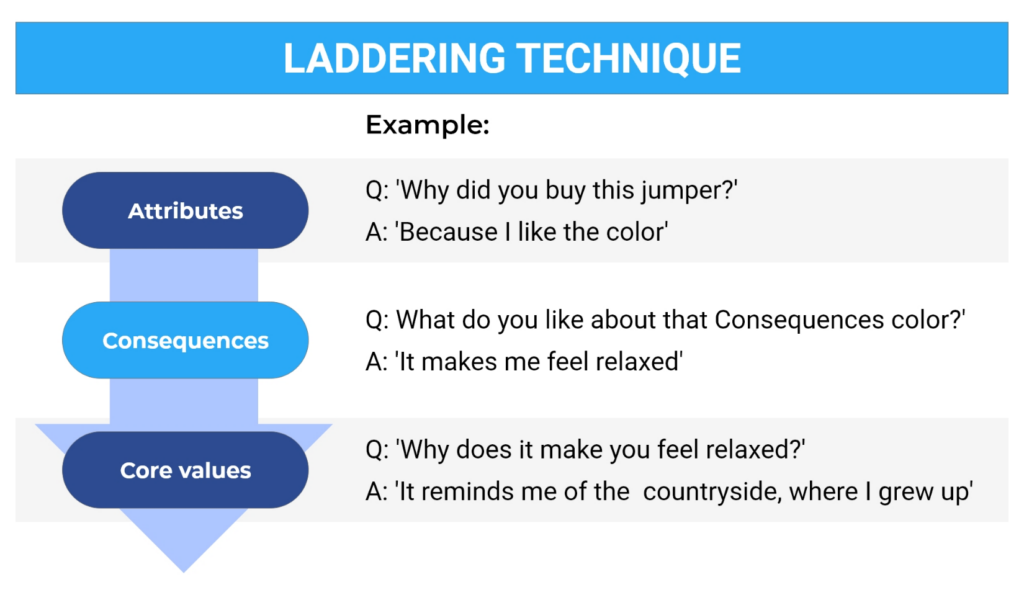

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a blanket term covering a wide range of research methods and theoretical framing approaches. The unifying factor in all these types of qualitative study is that they deal with data that cannot be counted. Typically this means things like people’s stories, feelings, opinions and emotions , and the meanings they ascribe to their experiences.

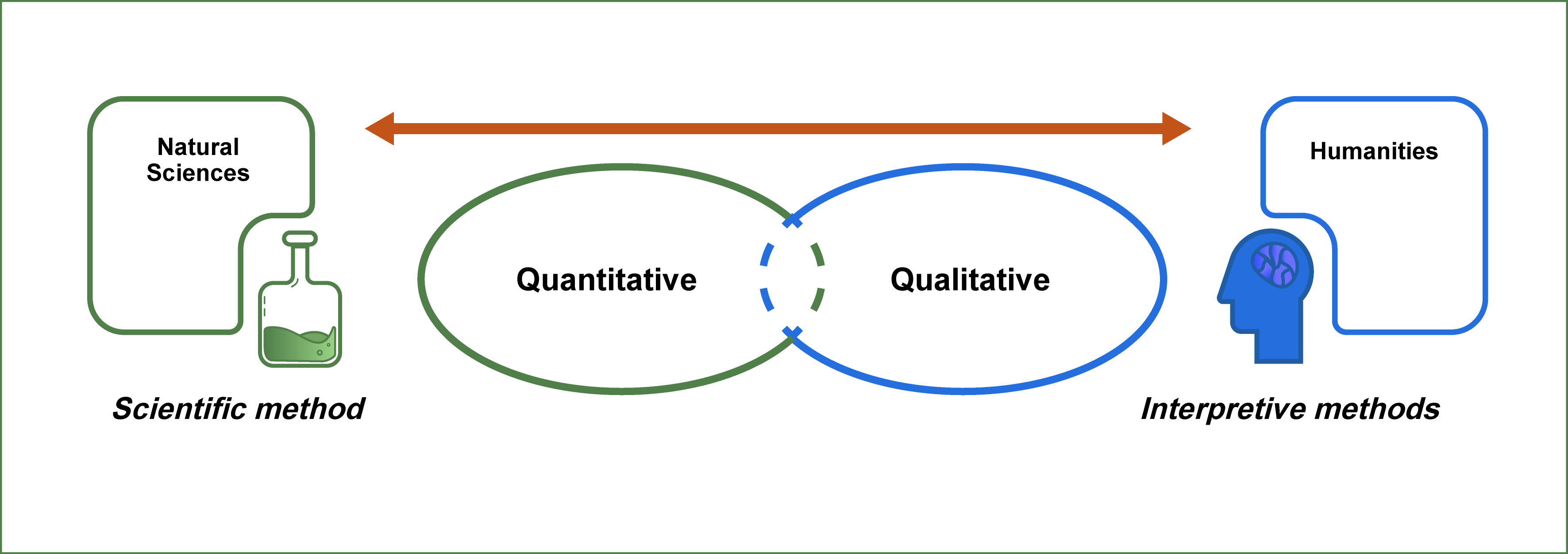

Qualitative study is one of two main categories of research, the other being quantitative research. Quantitative research deals with numerical data – that which can be counted and quantified, and which is mostly concerned with trends and patterns in large-scale datasets.

What are research questions?

Research questions are questions you are trying to answer with your research. To put it another way, your research question is the reason for your study, and the beginning point for your research design. There is normally only one research question per study, although if your project is very complex, you may have multiple research questions that are closely linked to one central question.

A good qualitative research question sums up your research objective. It’s a way of expressing the central question of your research, identifying your particular topic and the central issue you are examining.

Research questions are quite different from survey questions, questions used in focus groups or interview questions. A long list of questions is used in these types of study, as opposed to one central question. Additionally, interview or survey questions are asked of participants, whereas research questions are only for the researcher to maintain a clear understanding of the research design.

Research questions are used in both qualitative and quantitative research , although what makes a good research question might vary between the two.

In fact, the type of research questions you are asking can help you decide whether you need to take a quantitative or qualitative approach to your research project.

Discover the fundamentals of qualitative research

Quantitative vs. qualitative research questions

Writing research questions is very important in both qualitative and quantitative research, but the research questions that perform best in the two types of studies are quite different.

Quantitative research questions

Quantitative research questions usually relate to quantities, similarities and differences.

It might reflect the researchers’ interest in determining whether relationships between variables exist, and if so whether they are statistically significant. Or it may focus on establishing differences between things through comparison, and using statistical analysis to determine whether those differences are meaningful or due to chance.

- How much? This kind of research question is one of the simplest. It focuses on quantifying something. For example:

How many Yoruba speakers are there in the state of Maine?

- What is the connection?

This type of quantitative research question examines how one variable affects another.

For example:

How does a low level of sunlight affect the mood scores (1-10) of Antarctic explorers during winter?

- What is the difference? Quantitative research questions in this category identify two categories and measure the difference between them using numerical data.

Do white cats stay cooler than tabby cats in hot weather?

If your research question fits into one of the above categories, you’re probably going to be doing a quantitative study.

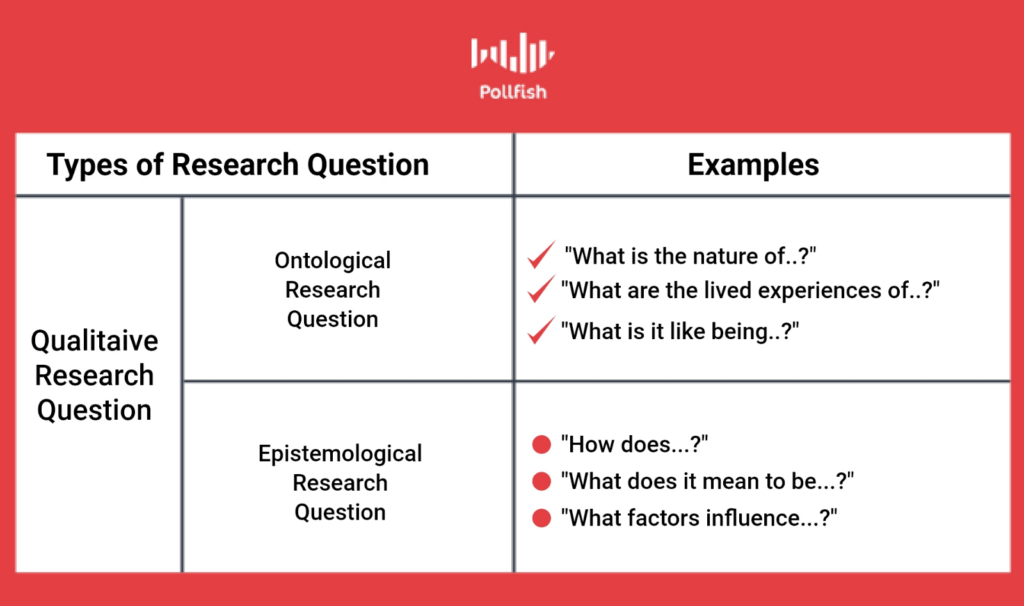

Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions focus on exploring phenomena, meanings and experiences.

Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research isn’t about finding causal relationships between variables. So although qualitative research questions might touch on topics that involve one variable influencing another, or looking at the difference between things, finding and quantifying those relationships isn’t the primary objective.

In fact, you as a qualitative researcher might end up studying a very similar topic to your colleague who is doing a quantitative study, but your areas of focus will be quite different. Your research methods will also be different – they might include focus groups, ethnography studies, and other kinds of qualitative study.

A few example qualitative research questions:

- What is it like being an Antarctic explorer during winter?

- What are the experiences of Yoruba speakers in the USA?

- How do white cat owners describe their pets?

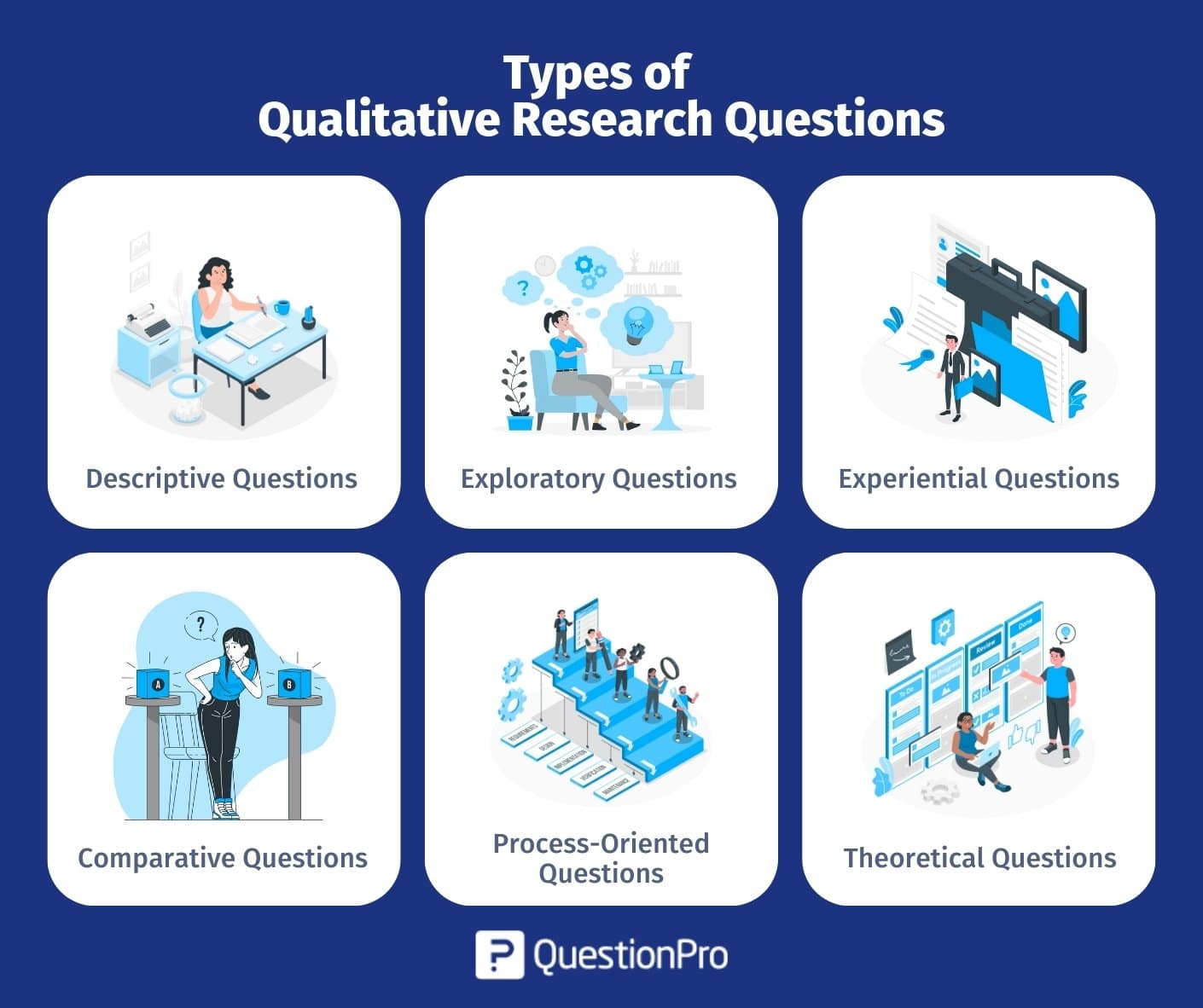

Qualitative research question types

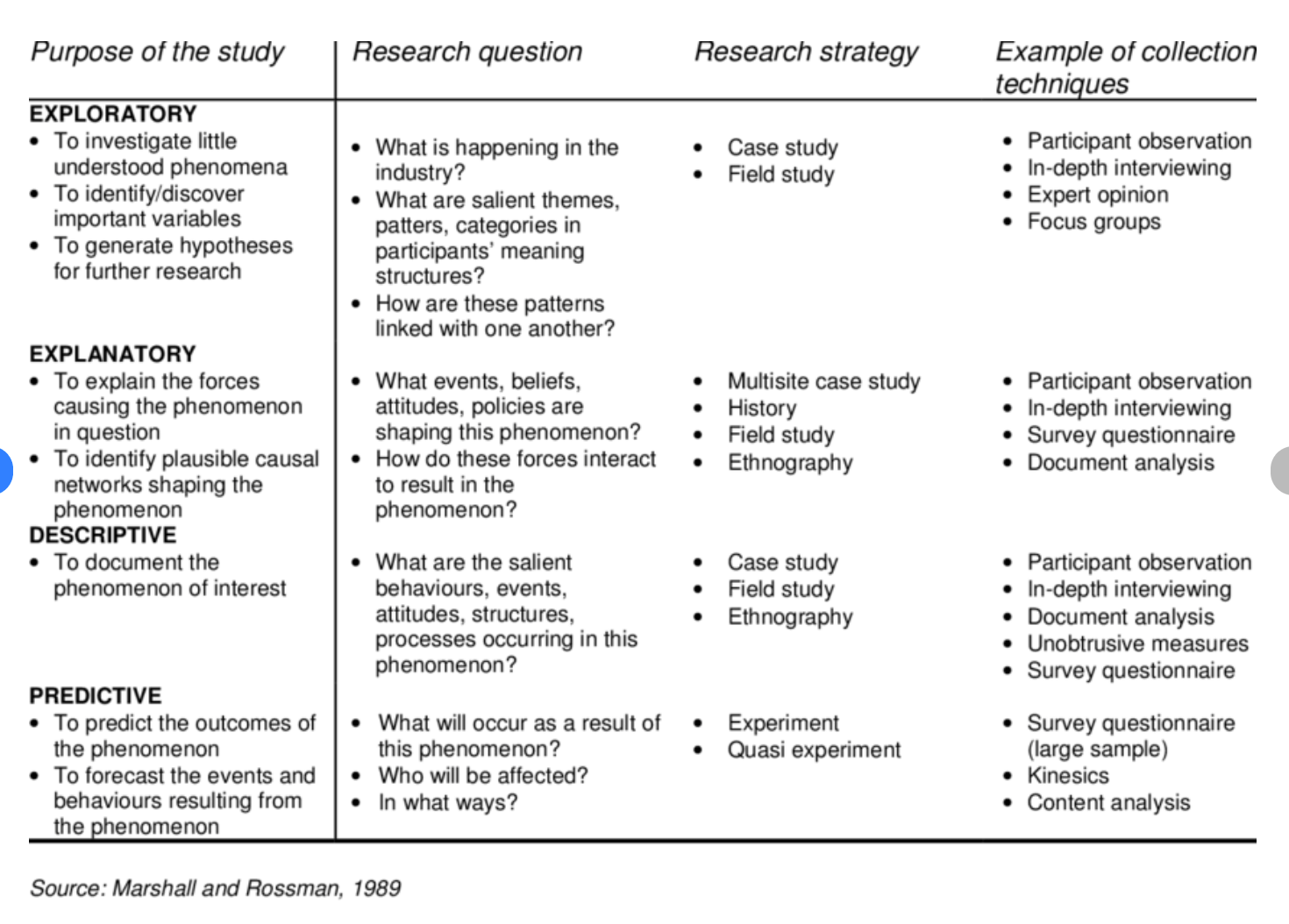

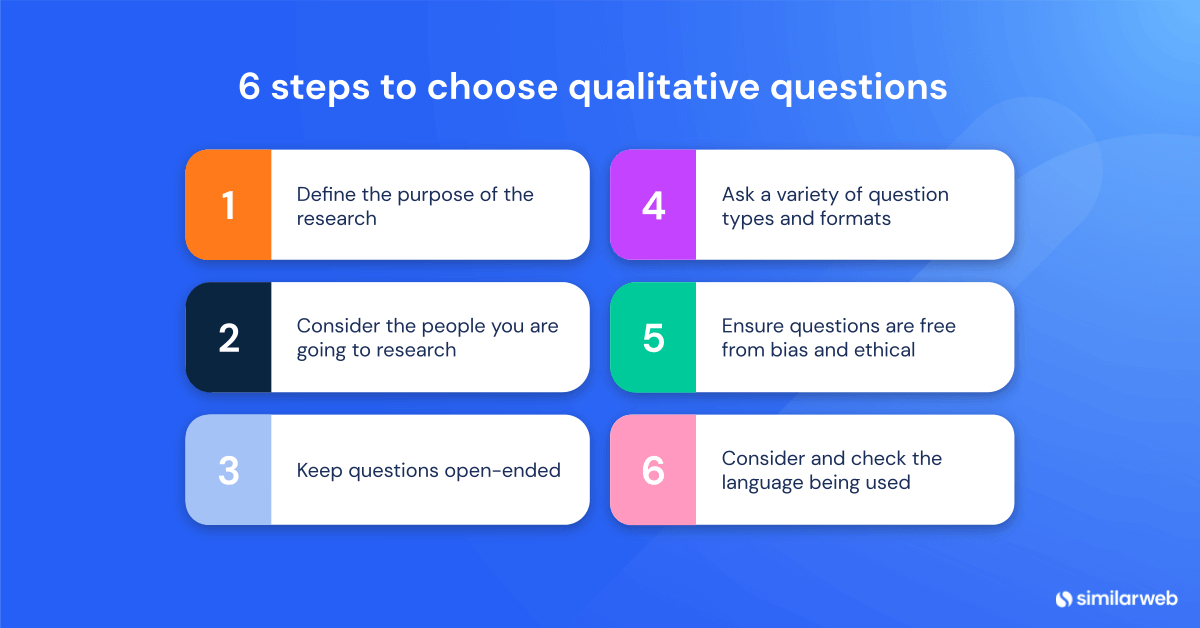

Marshall and Rossman (1989) identified 4 qualitative research question types, each with its own typical research strategy and methods.

- Exploratory questions

Exploratory questions are used when relatively little is known about the research topic. The process researchers follow when pursuing exploratory questions might involve interviewing participants, holding focus groups, or diving deep with a case study.

- Explanatory questions

With explanatory questions, the research topic is approached with a view to understanding the causes that lie behind phenomena. However, unlike a quantitative project, the focus of explanatory questions is on qualitative analysis of multiple interconnected factors that have influenced a particular group or area, rather than a provable causal link between dependent and independent variables.

- Descriptive questions

As the name suggests, descriptive questions aim to document and record what is happening. In answering descriptive questions , researchers might interact directly with participants with surveys or interviews, as well as using observational studies and ethnography studies that collect data on how participants interact with their wider environment.

- Predictive questions

Predictive questions start from the phenomena of interest and investigate what ramifications it might have in the future. Answering predictive questions may involve looking back as well as forward, with content analysis, questionnaires and studies of non-verbal communication (kinesics).

Why are good qualitative research questions important?

We know research questions are very important. But what makes them so essential? (And is that question a qualitative or quantitative one?)

Getting your qualitative research questions right has a number of benefits.

- It defines your qualitative research project Qualitative research questions definitively nail down the research population, the thing you’re examining, and what the nature of your answer will be.This means you can explain your research project to other people both inside and outside your business or organization. That could be critical when it comes to securing funding for your project, recruiting participants and members of your research team, and ultimately for publishing your results. It can also help you assess right the ethical considerations for your population of study.

- It maintains focus Good qualitative research questions help researchers to stick to the area of focus as they carry out their research. Keeping the research question in mind will help them steer away from tangents during their research or while they are carrying out qualitative research interviews. This holds true whatever the qualitative methods are, whether it’s a focus group, survey, thematic analysis or other type of inquiry.That doesn’t mean the research project can’t morph and change during its execution – sometimes this is acceptable and even welcome – but having a research question helps demarcate the starting point for the research. It can be referred back to if the scope and focus of the project does change.

- It helps make sure your outcomes are achievable

Because qualitative research questions help determine the kind of results you’re going to get, it helps make sure those results are achievable. By formulating good qualitative research questions in advance, you can make sure the things you want to know and the way you’re going to investigate them are grounded in practical reality. Otherwise, you may be at risk of taking on a research project that can’t be satisfactorily completed.

Developing good qualitative research questions

All researchers use research questions to define their parameters, keep their study on track and maintain focus on the research topic. This is especially important with qualitative questions, where there may be exploratory or inductive methods in use that introduce researchers to new and interesting areas of inquiry. Here are some tips for writing good qualitative research questions.

1. Keep it specific

Broader research questions are difficult to act on. They may also be open to interpretation, or leave some parameters undefined.

Strong example: How do Baby Boomers in the USA feel about their gender identity?

Weak example: Do people feel different about gender now?

2. Be original

Look for research questions that haven’t been widely addressed by others already.

Strong example: What are the effects of video calling on women’s experiences of work?

Weak example: Are women given less respect than men at work?

3. Make it research-worthy

Don’t ask a question that can be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’, or with a quick Google search.

Strong example: What do people like and dislike about living in a highly multi-lingual country?

Weak example: What languages are spoken in India?

4. Focus your question

Don’t roll multiple topics or questions into one. Qualitative data may involve multiple topics, but your qualitative questions should be focused.

Strong example: What is the experience of disabled children and their families when using social services?

Weak example: How can we improve social services for children affected by poverty and disability?

4. Focus on your own discipline, not someone else’s

Avoid asking questions that are for the politicians, police or others to address.

Strong example: What does it feel like to be the victim of a hate crime?

Weak example: How can hate crimes be prevented?

5. Ask something researchable

Big questions, questions about hypothetical events or questions that would require vastly more resources than you have access to are not useful starting points for qualitative studies. Qualitative words or subjective ideas that lack definition are also not helpful.

Strong example: How do perceptions of physical beauty vary between today’s youth and their parents’ generation?

Weak example: Which country has the most beautiful people in it?

Related resources

Qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, business research methods 12 min read, qualitative research interviews 11 min read, market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Seminal Authors

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Locating Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks This link opens in a new window

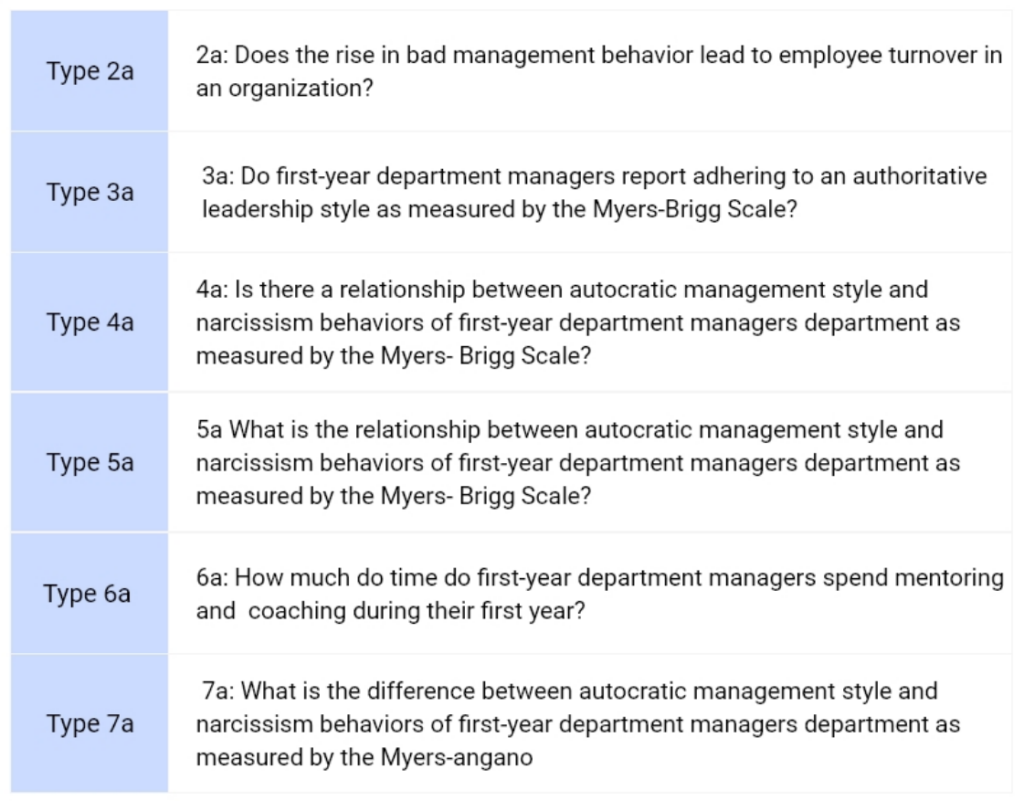

- Quantitative Research Questions

Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

What’s in a Qualitative Research Question?

Qualitative research questions are driven by the need for the study. Ideally, research questions are formulated as a result of the problem and purpose, which leads to the identification of the methodology. When a qualitative methodology is chosen, research questions should be exploratory and focused on the actual phenomenon under study.

From the Dissertation Center, Chapter 1: Research Question Overview , there are several considerations when forming a qualitative research question. Qualitative research questions should

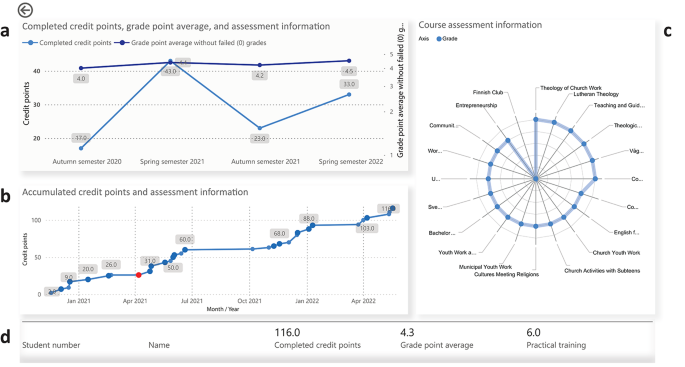

Below is an example of a qualitative phenomenological design. Note the use of the term “lived experience” in the central research question. This aligns with phenomenological design.

RQ1: “ What are the lived experiences of followers of mid-level managers in the financial services sector regarding their well-being on the job?”

If the researcher wants to focus on aspects of the theory used to support the study or dive deeper into aspects of the central RQ, sub-questions might be used. The following sub-questions could be formulated to seek further insight:

RQ1a. “How do followers perceive the quality and adequacy of the leader-follower exchanges between themselves and their novice leaders?”

RQ1b. “Under what conditions do leader-member exchanges affect a follower’s own level of well-being?”

Qualitative research questions also display the desire to explore or describe phenomena. Qualitative research seeks the lived experience, the personal experiences, the understandings, the meanings, and the stories associated with the concepts present in our studies.

We want to ensure our research questions are answerable and that we are not making assumptions about our sample. View the questions below:

How do healthcare providers perceive income inequality when providing care to poor patients?

In Example A, we see that there is no specificity of location or geographic areas. This could lead to findings that are varied, and the researcher may not find a clear pattern. Additionally, the question implies the focus is on “income inequality” when the actual focus is on the provision of care. The term “poor patients” can also be offensive, and most providers will not want to seem insensitive and may perceive income inequality as a challenge (of course!).

How do primary care nurses in outreach clinics describe providing quality care to residents of low-income urban neighborhoods?

In Example B, we see that there is greater specificity in the type of care provider. There is also a shift in language so that the focus is on how the individuals describe what they think about, experience, and navigate providing quality care.

Other Qualitative Research Question Examples

Vague : What are the strategies used by healthcare personnel to assist injured patients?

Try this : What is the experience of emergency room personnel in treating patients with a self-inflicted household injury?

The first question is general and vague. While in the same topic area, the second question is more precise and gives the reader a specific target population and a focus on the phenomenon they would have experienced. This question could be in line with a phenomenological study as we are seeking their experience or a case study as the ER personnel are a bounded entity.

Unclear : How do students experience progressing to college?

Try this : How do first-generation community members describe the aspects of their culture that promote aspiration to postsecondary education?

The first question does not have a focus on what progress is or what students are the focus. The second question provides a specific target population and provides the description to be provided by the participants. This question could be in line with a descriptive study.

- << Previous: Quantitative Research Questions

- Next: Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data >>

- Last Updated: Sep 7, 2024 9:42 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchtools

Chapter 4. Finding a Research Question and Approaches to Qualitative Research

We’ve discussed the research design process in general and ways of knowing favored by qualitative researchers. In chapter 2, I asked you to think about what interests you in terms of a focus of study, including your motivations and research purpose. It might be helpful to start this chapter with those short paragraphs you wrote about motivations and purpose in front of you. We are now going to try to develop those interests into actual research questions (first part of this chapter) and then choose among various “traditions of inquiry” that will be best suited to answering those questions. You’ve already been introduced to some of this (in chapter 1), but we will go further here.

Developing a Research Question

Research questions are different from general questions people have about the social world. They are narrowly tailored to fit a very specific issue, complete with context and time boundaries. Because we are engaged in empirical science and thus use “data” to answer our questions, the questions we ask must be answerable by data. A question is not the same as stating a problem. The point of the entire research project is to answer a particular question or set of questions. The question(s) should be interesting, relevant, practical, and ethical. Let’s say I am generally interested in the problem of student loan debt. That’s a good place to start, but we can’t simply ask,

General question: Is student loan debt really a problem today?

How could we possibly answer that question? What data could we use? Isn’t this really an axiological (values-based) question? There are no clues in the question as to what data would be appropriate here to help us get started. Students often begin with these large unanswerable questions. They are not research questions. Instead, we could ask,

Poor research question: How many people have debt?

This is still not a very good research question. Why not? It is answerable, although we would probably want to clarify the context. We could add some context to improve it so that the question now reads,

Mediocre research question: How many people in the US have debt today? And does this amount vary by age and location?

Now we have added some context, so we have a better idea of where to look and who to look at. But this is still a pretty poor or mediocre research question. Why is that? Let’s say we did answer it. What would we really know? Maybe we would find out that student loan debt has increased over time and that young people today have more of it. We probably already know this. We don’t really want to go through a lot of trouble answering a question whose answer we already have. In fact, part of the reason we are even asking this question is that we know (or think) it is a problem. Instead of asking what you already know, ask a question to which you really do not know the answer. I can’t stress this enough, so I will say it again: Ask a question to which you do not already know the answer . The point of research is not to prove or make a point but to find out something unknown. What about student loan debt is still a mystery to you? Reviewing the literature could help (see chapter 9). By reviewing the literature, you can get a good sense of what is still mysterious or unknown about student loan debt, and you won’t be reinventing the wheel when you conduct your research. Let’s say you review the literature, and you are struck by the fact that we still don’t understand the true impact of debt on how people are living their lives. A possible research question might be,

Fair research question: What impact does student debt have on the lives of debtors?

Good start, but we still need some context to help guide the project. It is not nearly specific enough.

Better research question: What impact does student debt have on young adults (ages twenty-five to thirty-five) living in the US today?

Now we’ve added context, but we can still do a little bit better in narrowing our research question so that it is both clear and doable; in other words, we want to frame it in a way that provides a very clear research program:

Optimal research question: How do young adults (ages twenty-five to thirty-five) living in the US today who have taken on $30,000 or more in student debt describe the impact of their debt on their lives in terms of finding/choosing a job, buying a house, getting married, and other major life events?

Now you have a research question that can be answered and a clear plan of how to answer it. You will talk to young adults living in the US today who have high debt loads and ask them to describe the impacts of debt on their lives. That is all now in the research question. Note how different this very specific question is from where we started with the “problem” of student debt.

Take some time practicing turning the following general questions into research questions:

- What can be done about the excessive use of force by police officers?

- Why haven’t societies taken firmer steps to address climate change?

- How do communities react to / deal with the opioid epidemic?

- Who has been the most adversely affected by COVID?

- When did political polarization get so bad?

Hint: Step back from each of the questions and try to articulate a possible underlying motivation, then formulate a research question that is specific and answerable.

It is important to take the time to come up with a research question, even if this research question changes a bit as you conduct your research (yes, research questions can change!). If you don’t have a clear question to start your research, you are likely to get very confused when designing your study because you will not be able to make coherent decisions about things like samples, sites, methods of data collection, and so on. Your research question is your anchor: “If we don’t have a question, we risk the possibility of going out into the field thinking we know what we’ll find and looking only for proof of what we expect to be there. That’s not empirical research (it’s not systematic)” ( Rubin 2021:37 ).

Researcher Note

How do you come up with ideas for what to study?

I study what surprises me. Usually, I come across a statistic that suggests something is common that I thought was rare. I tend to think it’s rare because the theories I read suggest it should be, and there’s not a lot of work in that area that helps me understand how the statistic came to be. So, for example, I learned that it’s common for Americans to marry partners who grew up in a different class than them and that about half of White kids born into the upper-middle class are downwardly mobile. I was so shocked by these facts that they naturally led to research questions. How do people come to marry someone who grew up in a different class? How do White kids born near the top of the class structure fall?

—Jessi Streib, author of The Power of the Past and Privilege Lost

What if you have literally no idea what the research question should be? How do you find a research question? Even if you have an interest in a topic before you get started, you see the problem now: topics and issues are not research questions! A research question doesn’t easily emerge; it takes a lot of time to hone one, as the practice above should demonstrate. In some research designs, the research question doesn’t even get clearly articulated until the end of data collection . More on that later. But you must start somewhere, of course. Start with your chosen discipline. This might seem obvious, but it is often overlooked. There is a reason it is called a discipline. We tend to think of “sociology,” “public health,” and “physics” as so many clusters of courses that are linked together by subject matter, but they are also disciplines in the sense that the study of each focuses the mind in a particular way and for particular ends. For example, in my own field, sociology, there is a loosely shared commitment to social justice and a general “sociological imagination” that enables its practitioners to connect personal experiences to society at large and to historical forces. It is helpful to think of issues and questions that are germane to your discipline. Within that overall field, there may be a particular course or unit of study you found most interesting. Within that course or unit of study, there may be an issue that intrigued you. And finally, within that issue, there may be an aspect or topic that you want to know more about.

When I was pursuing my dissertation research, I was asked often, “Why did you choose to study intimate partner violence among Native American women?” This question is necessary, and each time I answered, it helped shape me into a better researcher. I was interested in intimate partner violence because I am a survivor. I didn’t have intentions to work with a particular population or demographic—that came from my own deep introspection on my role as a researcher. I always questioned my positionality: What privileges do I hold as an academic? How has public health extracted information from institutionally marginalized populations? How can I build bridges between communities using my position, knowledge, and power? Public health as a field would not exist without the contributions of Indigenous people. So I started hanging out with them at community events, making friends, and engaging in self-education. Through these organic relationships built with Native women in the community, I saw that intimate partner violence was a huge issue. This led me to partner with Indigenous organizations to pursue a better understanding of how Native survivors of intimate partner violence seek support.

—Susanna Y. Park, PhD, mixed-methods researcher in public health and author of “How Native Women Seek Support as Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study”

One of the most exciting and satisfying things about doing academic research is that whatever you end up researching can become part of the body of knowledge that we have collectively created. Don’t make the mistake of thinking that you are doing this all on your own from scratch. Without even being aware of it, no matter if you are a first-year undergraduate student or a fourth-year graduate student, you have been trained to think certain questions are interesting. The very fact that you are majoring in a particular field or have signed up for years of graduate study in a program testifies to some level of commitment to a discipline. What we are looking for, ideally, is that your research builds on in some way (as extension, as critique, as lateral move) previous research and so adds to what we, collectively, understand about the social world. It is helpful to keep this in mind, as it may inspire you and also help guide you through the process. The point is, you are not meant to be doing something no one has ever thought of before, even if you are trying to find something that does not exactly duplicate previous research: “You may be trying to be too clever—aiming to come up with a topic unique in the history of the universe, something that will have people swooning with admiration at your originality and intellectual precociousness. Don’t do it. It’s safer…to settle on an ordinary, middle-of-the-road topic that will lend itself to a nicely organized process of project management. That’s the clever way of proceeding.… You can always let your cleverness shine through during the stages of design, analysis, and write-up. Don’t make things more difficult for yourself than you need to do” ( Davies 2007:20 ).

Rubin ( 2021 ) suggests four possible ways to develop a research question (there are many more, of course, but this can get you started). One way is to start with a theory that interests you and then select a topic where you can apply that theory. For example, you took a class on gender and society and learned about the “glass ceiling.” You could develop a study that tests that theory in a setting that has not yet been explored—maybe leadership at the Oregon Country Fair. The second way is to start with a topic that interests you and then go back to the books to find a theory that might explain it. This is arguably more difficult but often much more satisfying. Ask your professors for help—they might have ideas of theories or concepts that could be relevant or at least give you an idea of what books to read. The third way is to be very clever and select a question that already combines the topic and the theory. Rubin gives as one example sentencing disparities in criminology—this is both a topic and a theory or set of theories. You then just have to figure out particulars like setting and sample. I don’t know if I find this third way terribly helpful, but it might help you think through the possibilities. The fourth way involves identifying a puzzle or a problem, which can be either theoretical (something in the literature just doesn’t seem to make sense and you want to tackle addressing it) or empirical (something happened or is happening, and no one really understands why—think, for example, of mass school shootings).

Once you think you have an issue or topic that is worth exploring, you will need to (eventually) turn that into a good research question. A good research question is specific, clear, and feasible .

Specific . How specific a research question needs to be is somewhat related to the disciplinary conventions and whether the study is conceived inductively or deductively. In deductive research, one begins with a specific research question developed from the literature. You then collect data to test the theory or hypotheses accompanying your research question. In inductive research, however, one begins with data collection and analysis and builds theory from there. So naturally, the research question is a bit vaguer. In general, the more closely aligned to the natural sciences (and thus the deductive approach), the more a very tight and specific research question (along with specific, focused hypotheses) is required. This includes disciplines like psychology, geography, public health, environmental science, and marine resources management. The more one moves toward the humanities pole (and the inductive approach), the more looseness is permitted, as there is a general belief that we go into the field to find what is there, not necessarily what we imagine we are looking for (see figure 4.2). Disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, and gender and sexuality studies and some subdisciplines of public policy/public administration are closer to the humanities pole in this sense.

Regardless of discipline and approach, however, it is a good idea for beginning researchers to create a research question as specific as possible, as this will serve as your guide throughout the process. You can tweak it later if needed, but start with something specific enough that you know what it is you are doing and why. It is more difficult to deal with ambiguity when you are starting out than later in your career, when you have a better handle on what you are doing. Being under a time constraint means the more specific the question, the better. Questions should always specify contexts, geographical locations, and time frames. Go back to your practice research questions and make sure that these are included.

Clear . A clear research question doesn’t only need to be intelligible to any reader (which, of course, it should); it needs to clarify any meanings of particular words or concepts (e.g., What is excessive force?). Check all your concepts to see if there are ways you can clarify them further—for example, note that we shifted from impact of debt to impact of high debt load and specified this as beginning at $30,000. Ideally, we would use the literature to help us clarify what a high debt load is or how to define “excessive” force.

Feasible . In order to know if your question is feasible, you are going to have to think a little bit about your entire research design. For example, a question that asks about the real-time impact of COVID restrictions on learning outcomes would require a time machine. You could tweak the question to ask instead about the long-term impacts of COVID restrictions, as measured two years after their end. Or let’s say you are interested in assessing the damage of opioid abuse on small-town communities across the United States. Is it feasible to cover the entire US? You might need a team of researchers to do this if you are planning on on-the-ground observations. Perhaps a case study of one particular community might be best. Then your research question needs to be changed accordingly.

Here are some things to consider in terms of feasibility:

- Is the question too general for what you actually intend to do or examine? (Are you specifying the world when you only have time to explore a sliver of that world?)

- Is the question suitable for the time you have available? (You will need different research questions for a study that can be completed in a term than one where you have one to two years, as in a master’s program, or even three to eight years, as in a doctoral program.)

- Is the focus specific enough that you know where and how to begin?

- What are the costs involved in doing this study, including time? Will you need to travel somewhere, and if so, how will you pay for it?

- Will there be problems with “access”? (More on this in later chapters, but for now, consider how you might actually find people to interview or places to observe and whether gatekeepers exist who might keep you out.)

- Will you need to submit an application proposal for your university’s IRB (institutional review board)? If you are doing any research with live human subjects, you probably need to factor in the time and potential hassle of an IRB review (see chapter 8). If you are under severe time constraints, you might need to consider developing a research question that can be addressed with secondary sources, online content, or historical archives (see chapters 16 and 17).

In addition to these practicalities, you will also want to consider the research question in terms of what is best for you now. Are you engaged in research because you are required to be—jumping a hurdle for a course or for your degree? If so, you really do want to think about your project as training and develop a question that will allow you to practice whatever data collection and analysis techniques you want to develop. For example, if you are a grad student in a public health program who is interested in eventually doing work that requires conducting interviews with patients, develop a research question and research design that is interview based. Focus on the practicality (and practice) of the study more than the theoretical impact or academic contribution, in other words. On the other hand, if you are a PhD candidate who is seeking an academic position in the future, your research question should be pitched in a way to build theoretical knowledge as well (the phrasing is typically “original contribution to scholarship”).

The more time you have to devote to the study and the larger the project, the more important it is to reflect on your own motivations and goals when crafting a research question (remember chapter 2?). By “your own motivations and goals,” I mean what interests you about the social world and what impact you want your research to have, both academically and practically speaking. Many students have secret (or not-so-secret) plans to make the world a better place by helping address climate change, pointing out pressure points to fight inequities, or bringing awareness to an overlooked area of concern. My own work in graduate school was motivated by the last of these three—the not-so-secret goal of my research was to raise awareness about obstacles to success for first-generation and working-class college students. This underlying goal motivated me to complete my dissertation in a timely manner and then to further continue work in this area and see my research get published. I cared enough about the topic that I was not ready to put it away. I am still not ready to put it away. I encourage you to find topics that you can’t put away, ever. That will keep you going whenever things get difficult in the research process, as they inevitably will.

On the other hand, if you are an undergraduate and you really have very little time, some of the best advice I have heard is to find a study you really like and adapt it to a new context. Perhaps you read a study about how students select majors and how this differs by class ( Hurst 2019 ). You can try to replicate the study on a small scale among your classmates. Use the same research question, but revise for your context. You can probably even find the exact questions I used and ask them in the new sample. Then when you get to the analysis and write-up, you have a comparison study to guide you, and you can say interesting things about the new context and whether the original findings were confirmed (similar) or not. You can even propose reasons why you might have found differences between one and the other.

Another way of thinking about research questions is to explicitly tie them to the type of purpose of your study. Of course, this means being very clear about what your ultimate purpose is! Marshall and Rossman ( 2016 ) break down the purpose of a study into four categories: exploratory, explanatory, descriptive, and emancipatory ( 78 ). Exploratory purpose types include wanting to investigate little-understood phenomena, or identifying or discovering important new categories of meaning, or generating hypotheses for further research. For these, research questions might be fairly loose: What is going on here? How are people interacting on this site? What do people talk about when you ask them about the state of the world? You are almost (but never entirely) starting from scratch. Be careful though—just because a topic is new to you does not mean it is really new. Someone else (or many other someones) may already have done this exploratory research. Part of your job is to find this out (more on this in “What Is a ‘Literature Review’?” in chapter 9). Descriptive purposes (documenting and describing a phenomenon) are similar to exploratory purposes but with a much clearer goal (description). A good research question for a descriptive study would specify the actions, events, beliefs, attitudes, structures, and/or processes that will be described.

Most researchers find that their topic has already been explored and described, so they move to trying to explain a relationship or phenomenon. For these, you will want research questions that capture the relationships of interest. For example, how does gender influence one’s understanding of police brutality (because we already know from the literature that it does, so now we are interested in understanding how and why)? Or what is the relationship between education and climate change denialism? If you find that prior research has already provided a lot of evidence about those relationships as well as explanations for how they work, and you want to move the needle past explanation into action, you might find yourself trying to conduct an emancipatory study. You want to be even more clear in acknowledging past research if you find yourself here. Then create a research question that will allow you to “create opportunities and the will to engage in social action” ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:78 ). Research questions might ask, “How do participants problematize their circumstances and take positive social action?” If we know that some students have come together to fight against student debt, how are they doing this, and with what success? Your purpose would be to help evaluate possibilities for social change and to use your research to make recommendations for more successful emancipatory actions.

Recap: Be specific. Be clear. Be practical. And do what you love.

Choosing an Approach or Tradition

Qualitative researchers may be defined as those who are working with data that is not in numerical form, but there are actually multiple traditions or approaches that fall under this broad category. I find it useful to know a little bit about the history and development of qualitative research to better understand the differences in these approaches. The following chart provides an overview of the six phases of development identified by Denzin and Lincoln ( 2005 ):

Table 4.1. Six Phases of Development

| Year/Period | Phase | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1945 | Traditional | Influence of positivism; anthropologists and ethnographers strive for objectivity when reporting observations in the field |

| 1945-1970 | Modernist | Emphasis of methodological rigor and procedural formalism as a way of gaining acceptance |

| 1970-1986 | Blurred genres | Large number of alternative approaches emerge, all competing with and contesting positivist and formalist approaches; e.g., structuralism, symbolic interactionism, ethnomethodology, constructionism |

| 1980s-1990s | Crisis of representation | Attention turns to issues of power and privilege and the necessity of reflexivity around race, class, gender positions and identities; traditional notions of validity and neutrality were undermined |

| 1990s-2000 | Triple crisis | Moving beyond issues of representation, questions raised about evaluation of qualitative research and the writing/presentation of it as well; more political and participatory forms emerge; qualitative research to advance social justice advocated |

| 2000s... | Postexperimental | Boundaries expanded to include creative nonfiction, autobiographical ethnography, poetic representation, and other creative approaches |

There are other ways one could present the history as well. Feminist theory and methodologies came to the fore in the 1970s and 1980s and had a lot to do with the internal critique of more positivist approaches. Feminists were quite aware that standpoint matters—that the identity of the researcher plays a role in the research, and they were ardent supporters of dismantling unjust power systems and using qualitative methods to help advance this mission. You might note, too, that many of the internal disputes were basically epistemological disputes about how we know what we know and whether one’s social location/position delimits that knowledge. Today, we are in a bountiful world of qualitative research, one that embraces multiple forms of knowing and knowledge. This is good, but it means that you, the student, have more choice when it comes to situating your study and framing your research question, and some will expect you to signal the choices you have made in any research protocols you write or publications and presentations.

Creswell’s ( 1998 ) definition of qualitative research includes the notion of distinct traditions of inquiry: “Qualitative research is an inquiry process of understanding based on distinct methodological traditions of inquiry that explore a social or human problem. The research builds complex, holistic pictures, analyzes words, reports detailed views of informants , and conducted the study in a natural setting” (15; emphases added). I usually caution my students against taking shelter under one of these approaches, as, practically speaking, there is a lot of mixing of traditions among researchers. And yet it is useful to know something about the various histories and approaches, particularly as you are first starting out. Each tradition tends to favor a particular epistemological perspective (see chapter 3), a way of reasoning (see “ Advanced: Inductive versus Deductive Reasoning ”), and a data-collection technique.

There are anywhere from ten to twenty “traditions of inquiry,” depending on how one draws the boundaries. In my accounting, there are twelve, but three approaches tend to dominate the field.

Ethnography

Ethnography was developed from the discipline of anthropology, as the study of (other) culture(s). From a relatively positivist/objective approach to writing down the “truth” of what is observed during the colonial era (where this “truth” was then often used to help colonial administrators maintain order and exploit people and extract resources more effectively), ethnography was adopted by all kinds of social science researchers to get a better understanding of how groups of people (various subcultures and cultures) live their lives. Today, ethnographers are more likely to be seeking to dismantle power relations than to support them. They often study groups of people that are overlooked and marginalized, and sometimes they do the obverse by demonstrating how truly strange the familiar practices of the dominant group are. Ethnography is also central to organizational studies (e.g., How does this institution actually work?) and studies of education (e.g., What is it like to be a student during the COVID era?).

Ethnographers use methods of participant observation and intensive fieldwork in their studies, often living or working among the group under study for months at a time (and, in some cases, years). I’ve called this “deep ethnography,” and it is the subject of chapter 14. The data ethnographers analyze are copious “field notes” written while in the field, often supplemented by in-depth interviews and many more casual conversations. The final product of ethnographers is a “thick” description of the culture. This makes reading ethnographies enjoyable, as the goal is to write in such a way that the reader feels immersed in the culture.

There are variations on the ethnography, such as the autoethnography , where the researcher uses a systematic and rigorous study of themselves to better understand the culture in which they find themselves. Autoethnography is a relatively new approach, even though it is derived from one of the oldest approaches. One can say that it takes to heart the feminist directive to “make the personal political,” to underscore the connections between personal experiences and larger social and political structures. Introspection becomes the primary data source.

Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory holds a special place in qualitative research for a few reasons, not least of which is that nonqualitative researchers often mistakenly believe that Grounded Theory is the only qualitative research methodology . Sometimes, it is easier for students to explain what they are doing as “Grounded Theory” because it sounds “more scientific” than the alternative descriptions of qualitative research. This is definitely part of its appeal. Grounded Theory is the name given to the systematic inductive approach first developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Too few people actually read Glaser and Strauss’s book. It is both groundbreaking and fairly unremarkable at the same time. As a historical intervention into research methods generally, it is both a sharp critique of positivist methods in the social sciences (theory testing) and a rejection of purely descriptive accounts-building qualitative research. Glaser and Strauss argued for an approach whose goal was to construct (middle-level) theories from recursive data analysis of nonnumerical data (interviews and observations). They advocated a “constant comparative method” in which coding and analysis take place simultaneously and recursively. The demands are fairly strenuous. If done correctly, the result is the development of a new theory about the social world.

So why do I call this “fairly unremarkable”? To some extent, all qualitative research already does what Glaser and Strauss ( 1967 ) recommend, albeit without denoting the processes quite so specifically. As will be seen throughout the rest of this textbook, all qualitative research employs some “constant comparisons” through recursive data analyses. Where Grounded Theory sets itself apart from a significant number of qualitative research projects, however, is in its dedication to inductively building theory. Personally, I think it is important to understand that Glaser and Strauss were rejecting deductive theory testing in sociology when they first wrote their book. They were part of a rising cohort who rejected the positivist mathematical approaches that were taking over sociology journals in the 1950s and 1960s. Here are some of the comments and points they make against this kind of work:

Accurate description and verification are not so crucial when one’s purpose is to generate theory. ( 28 ; further arguing that sampling strategies are different when one is not trying to test a theory or generalize results)

Illuminating perspectives are too often suppressed when the main emphasis is verifying theory. ( 40 )

Testing for statistical significance can obscure from theoretical relevance. ( 201 )

Instead, they argued, sociologists should be building theories about the social world. They are not physicists who spend time testing and refining theories. And they are not journalists who report descriptions. What makes sociologists better than journalists and other professionals is that they develop theory from their work “In their driving efforts to get the facts [research sociologists] tend to forget that the distinctive offering of sociology to our society is sociological theory, not research description” ( 30–31 ).

Grounded Theory’s inductive approach can be off-putting to students who have a general research question in mind and a working hypothesis. The true Grounded Theory approach is often used in exploratory studies where there are no extant theories. After all, the promise of this approach is theory generation, not theory testing. Flying totally free at the start can be terrifying. It can also be a little disingenuous, as there are very few things under the sun that have not been considered before. Barbour ( 2008:197 ) laments that this approach is sometimes used because the researcher is too lazy to read the relevant literature.

To summarize, Glaser and Strauss justified the qualitative research project in a way that gave it standing among the social sciences, especially vis-à-vis quantitative researchers. By distinguishing the constant comparative method from journalism, Glaser and Strauss enabled qualitative research to gain legitimacy.

So what is it exactly, and how does one do it? The following stages provide a succinct and basic overview, differentiating the portions that are similar to/in accordance with qualitative research methods generally and those that are distinct from the Grounded Theory approach:

Step 1. Select a case, sample, and setting (similar—unless you begin with a theory to test!).

Step 2. Begin data collection (similar).

Step 3. Engage data analysis (similar in general but specificity of details somewhat unique to Grounded Theory): (1) emergent coding (initial followed by focused), (2) axial (a priori) coding , (3) theoretical coding , (4) creation of theoretical categories; analysis ends when “theoretical saturation ” has been achieved.

Grounded Theory’s prescriptive (i.e., it has a set of rules) framework can appeal to beginning students, but it is unnecessary to adopt the entire approach in order to make use of some of its suggestions. And if one does not exactly follow the Grounded Theory rulebook, it can mislead others if you tend to call what you are doing Grounded Theory when you are not:

Grounded theory continues to be a misunderstood method, although many researchers purport to use it. Qualitative researchers often claim to conduct grounded theory studies without fully understanding or adopting its distinctive guidelines. They may employ one or two of the strategies or mistake qualitative analysis for grounded theory. Conversely, other researchers employ grounded theory methods in reductionist, mechanistic ways. Neither approach embodies the flexible yet systematic mode of inquiry, directed but open-ended analysis, and imaginative theorizing from empirical data that grounded theory methods can foster. Subsequently, the potential of grounded theory methods for generating middle-range theory has not been fully realized ( Charmaz 2014 ).

Phenomenology

Where Grounded Theory sets itself apart for its inductive systematic approach to data analysis, phenomenologies are distinct for their focus on what is studied—in this case, the meanings of “lived experiences” of a group of persons sharing a particular event or circumstance. There are phenomenologies of being working class ( Charlesworth 2000 ), of the tourist experience ( Cohen 1979 ), of Whiteness ( Ahmed 2007 ). The phenomenon of interest may also be an emotion or circumstance. One can study the phenomenon of “White rage,” for example, or the phenomenon of arranged marriage.

The roots of phenomenology lie in philosophy (Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Sartre) but have been adapted by sociologists in particular. Phenomenologists explore “how human beings make sense of experience and transform experience into consciousness, both individually and as shared meaning” ( Patton 2002:104 ).

One of the most important aspects of conducting a good phenomenological study is getting the sample exactly right so that each person can speak to the phenomenon in question. Because the researcher is interested in the meanings of an experience, in-depth interviews are the preferred method of data collection. Observations are not nearly as helpful here because people may do a great number of things without meaning to or without being conscious of their implications. This is important to note because phenomenologists are studying not “the reality” of what happens at all but an articulated understanding of a lived experience. When reading a phenomenological study, it is important to keep this straight—too often I have heard students critique a study because the interviewer didn’t actually see how people’s behavior might conflict with what they say (which is, at heart, an epistemological issue!).

In addition to the “big three,” there are many other approaches; some are variations, and some are distinct approaches in their own right. Case studies focus explicitly on context and dynamic interactions over time and can be accomplished with quantitative or qualitative methods or a mixture of both (for this reason, I am not considering it as one of the big three qualitative methods, even though it is a very common approach). Whatever methods are used, a contextualized deep understanding of the case (or cases) is central.

Critical inquiry is a loose collection of techniques held together by a core argument that understanding issues of power should be the focus of much social science research or, to put this another way, that it is impossible to understand society (its people and institutions) without paying attention to the ways that power relations and power dynamics inform and deform those people and institutions. This attention to power dynamics includes how research is conducted too. All research fundamentally involves issues of power. For this reason, many critical inquiry traditions include a place for collaboration between researcher and researched. Examples include (1) critical narrative analysis, which seeks to describe the meaning of experience for marginalized or oppressed persons or groups through storytelling; (2) participatory action research, which requires collaboration between the researcher and the research subjects or community of interest; and (3) critical race analysis, a methodological application of Critical Race Theory (CRT), which posits that racial oppression is endemic (if not always throughout time and place, at least now and here).

Do you follow a particular tradition of inquiry? Why?

Shawn Wilson’s book, Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods , is my holy grail. It really flipped my understanding of research and relationships. Rather than thinking linearly and approaching research in a more canonical sense, Wilson shook my world view by drawing me into a pattern of inquiry that emphasized transparency and relational accountability. The Indigenous research paradigm is applicable in all research settings, and I follow it because it pushes me to constantly evaluate my position as a knowledge seeker and knowledge sharer.

Autoethnography takes the researcher as the subject. This is one approach that is difficult to explain to more quantitatively minded researchers, as it seems to violate many of the norms of “scientific research” as understood by them. First, the sample size is quite small—the n is 1, the researcher. Two, the researcher is not a neutral observer—indeed, the subjectivity of the researcher is the main strength of this approach. Autoethnographies can be extremely powerful for their depth of understanding and reflexivity, but they need to be conducted in their own version of rigor to stand up to scrutiny by skeptics. If you are skeptical, read one of the excellent published examples out there—I bet you will be impressed with what you take away. As they say, the proof is in the pudding on this approach.

Advanced: Inductive versus Deductive Reasoning

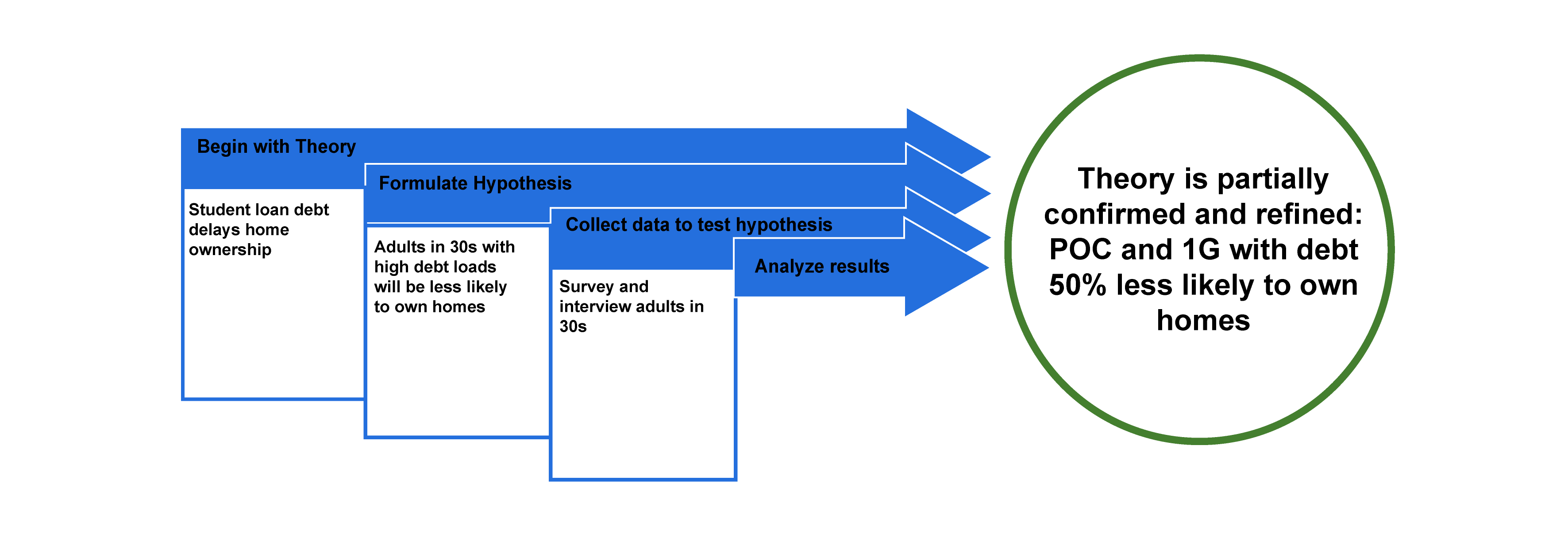

There has been a great deal of ink shed in the discussion of inductive versus deductive approaches, not all of it very instructive. Although there is a huge conceptual difference between them, in practical terms, most researchers cycle between the two, even within the same research project. The simplest way to explain the difference between the two is that we are using deductive reasoning when we test an existing theory (move from general to particular), and we are using inductive reasoning when we are generating theory (move from particular to general). Figure 4.2 provides a schematic of the deductive approach. From the literature, we select a theory about the impact of student loan debt: student loan debt will delay homeownership among young adults. We then formulate a hypothesis based on this theory: adults in their thirties with high debt loads will be less likely to own homes than their peers who do not have high debt loads. We then collect data to test the hypothesis and analyze the results. We find that homeownership is substantially lower among persons of color and those who were the first in their families to graduate from college. Notably, high debt loads did not affect homeownership among White adults whose parents held college degrees. We thus refine the theory to match the new findings: student debt loads delay homeownership among some young adults, thereby increasing inequalities in this generation. We have now contributed new knowledge to our collective corpus.

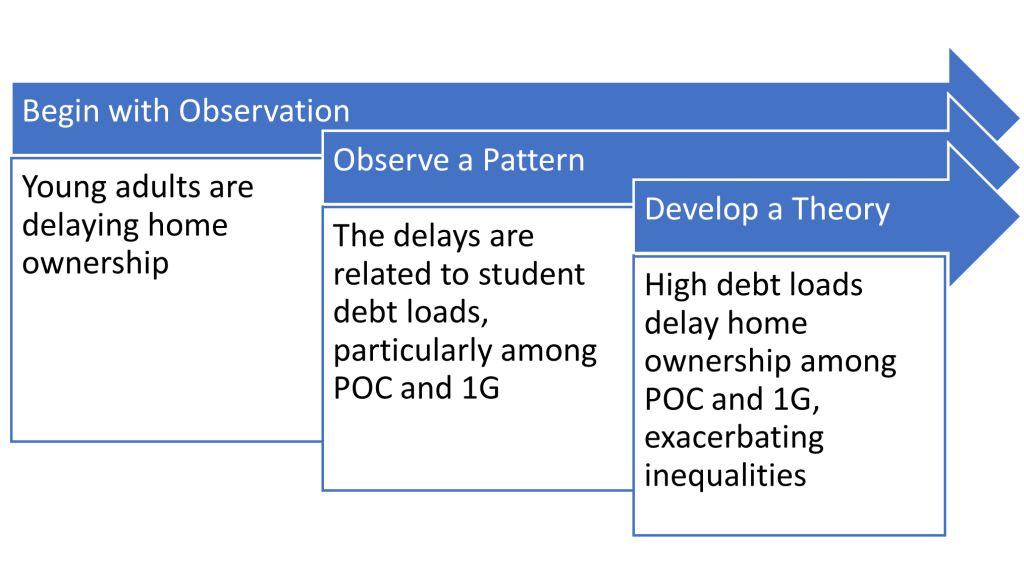

The inductive approach is contrasted in figure 4.3. Here, we did not begin with a preexisting theory or previous literature but instead began with an observation. Perhaps we were conducting interviews with young adults who held high amounts of debt and stumbled across this observation, struck by how many were renting apartments or small houses. We then noted a pattern—not all the young adults we were talking to were renting; race and class seemed to play a role here. We would then probably expand our study in a way to be able to further test this developing theory, ensuring that we were not seeing anomalous patterns. Once we were confident about our observations and analyses, we would then develop a theory, coming to the same place as our deductive approach, but in reverse.

A third form of reasoning, abductive (sometimes referred to as probabilistic reasoning) was developed in the late nineteenth century by American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. I have included some articles for further reading for those interested.

Among social scientists, the deductive approach is often relaxed so that a research question is set based on the existing literature rather than creating a hypothesis or set of hypotheses to test. Some journals still require researchers to articulate hypotheses, however. If you have in mind a publication, it is probably a good idea to take a look at how most articles are organized and whether specific hypotheses statements are included.

Table 4.2. Twelve Approaches. Adapted from Patton 2002:132-133.

| Approach | Home discipline | /Data Collection Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnography | Anthropology | Fieldwork/Observations + supplemental interviews |

| Grounded theory | Sociology | Fieldwork/Observations + Interviews |

| Phenomenology | Philosophy | In-depth interviews |

| Constructivism | Sociology | Focus Groups; Interviews |

| Heuristic inquiry | Psychology | Self-reflections and fieldnotes + interviews |

| Ethnomethodology | Sociology | In-depth interviews + Fieldwork, including social experiments |

| Symbolic interaction | Social psychology | Focus Groups + Interviews |

| Semiotics | Linguistics | Textual analyses + interviews/focus groups |

| Hermeneutics | Theology | Textual analyses |

| Narrative analysis | Literary criticism | Interviews, Oral Histories, Textual Analyses, Historical Artefacts, Content Analyses |

| Ecological psychology | Ecology | Observation |

| Orientational/Standpoint approaches (critical theory, feminist theory) | Law; Sociology | PAR, Interviews, Focus Groups |

Further Readings

The following readings have been examples of various approaches or traditions of inquiry:

Ahmed, Sara. 2007. “A Phenomenology of Whiteness.” Feminist Theory 8(2):149–168.

Charlesworth, Simon. 2000. A Phenomenology of Working-Class Experience . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.*

Clandinin, D. Jean, and F. Michael Connelly. 2000. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cohen, E. 1979. “A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences.” Sociology 13(2):179–201.

Cooke, Bill, and Uma Kothari, eds. 2001. Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books. A critique of participatory action.

Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Crabtree, B. F., and W. L. Miller, eds. 1999. Doing Qualitative Research: Multiple Strategies . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Creswell, John W. 1997. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . New York: Aldine.

Gobo, Giampetro, and Andrea Molle. 2008. Doing Ethnography . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Hancock, Dawson B., and Bob Algozzine. 2016. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Research . 3rd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Harding, Sandra. 1987. Feminism and Methodology . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Husserl, Edmund. (1913) 2017. Ideas: Introduction to Pure Phenomenology . Eastford, CT: Martino Fine Books.

Rose, Gillian. 2012. Visual Methodologies . 3rd ed. London: SAGE.

Van der Riet, M. 2009. “Participatory Research and the Philosophy of Social Science: Beyond the Moral Imperative.” Qualitative Inquiry 14(4):546–565.

Van Manen, Max. 1990. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy . Albany: State University of New York.

Wortham, Stanton. 2001. Narratives in Action: A Strategy for Research and Analysis . New York: Teachers College Press.

Inductive, Deductive, and Abductive Reasoning and Nomothetic Science in General

Aliseda, Atocha. 2003. “Mathematical Reasoning vs. Abductive Reasoning: A Structural Approach.” Synthese 134(1/2):25–44.

Bonk, Thomas. 1997. “Newtonian Gravity, Quantum Discontinuity and the Determination of Theory by Evidence.” Synthese 112(1):53–73. A (natural) scientific discussion of inductive reasoning.

Bonnell, Victoria E. 1980. “The Uses of Theory, Concepts and Comparison in Historical Sociology.” C omparative Studies in Society and History 22(2):156–173.

Crane, Mark, and Michael C. Newman. 1996. “Scientific Method in Environmental Toxicology.” Environmental Reviews 4(2):112–122.

Huang, Philip C. C., and Yuan Gao. 2015. “Should Social Science and Jurisprudence Imitate Natural Science?” Modern China 41(2):131–167.

Mingers, J. 2012. “Abduction: The Missing Link between Deduction and Induction. A Comment on Ormerod’s ‘Rational Inference: Deductive, Inductive and Probabilistic Thinking.’” Journal of the Operational Research Society 63(6):860–861.

Ormerod, Richard J. 2010. “Rational Inference: Deductive, Inductive and Probabilistic Thinking.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 61(8):1207–1223.

Perry, Charner P. 1927. “Inductive vs. Deductive Method in Social Science Research.” Southwestern Political and Social Science Quarterly 8(1):66–74.

Plutynski, Anya. 2011. “Four Problems of Abduction: A Brief History.” HOPOS: The Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science 1(2):227–248.

Thompson, Bruce, and Gloria M. Borrello. 1992. “Different Views of Love: Deductive and Inductive Lines of Inquiry.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 1(5):154–156.

Tracy, Sarah J. 2012. “The Toxic and Mythical Combination of a Deductive Writing Logic for Inductive Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Communication Research 1(1):109–141.

A place or collection containing records, documents, or other materials of historical interest; most universities have an archive of material related to the university’s history, as well as other “special collections” that may be of interest to members of the community.

A person who introduces the researcher to a field site’s culture and population. Also referred to as guides. Used in ethnography .

A form of research and a methodological tradition of inquiry in which the researcher uses self-reflection and writing to explore personal experiences and connect this autobiographical story to wider cultural, political, and social meanings and understandings. “Autoethnography is a research method that uses a researcher's personal experience to describe and critique cultural beliefs, practices, and experiences” ( Adams, Jones, and Ellis 2015 ).

The philosophical framework in which research is conducted; the approach to “research” (what practices this entails, etc.). Inevitably, one’s epistemological perspective will also guide one’s methodological choices, as in the case of a constructivist who employs a Grounded Theory approach to observations and interviews, or an objectivist who surveys key figures in an organization to find out how that organization is run. One of the key methodological distinctions in social science research is that between quantitative and qualitative research.

The process of labeling and organizing qualitative data to identify different themes and the relationships between them; a way of simplifying data to allow better management and retrieval of key themes and illustrative passages. See coding frame and codebook.

A later stage coding process used in Grounded Theory in which data is reassembled around a category, or axis.

A later stage-coding process used in Grounded Theory in which key words or key phrases capture the emergent theory.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

A methodological tradition of inquiry that focuses on the meanings held by individuals and/or groups about a particular phenomenon (e.g., a “phenomenology of whiteness” or a “phenomenology of first-generation college students”). Sometimes this is referred to as understanding “the lived experience” of a particular group or culture. Interviews form the primary tool of data collection for phenomenological studies. Derived from the German philosophy of phenomenology (Husserl 1913; 2017).

The number of individuals (or units) included in your sample

A form of reasoning which employs a “top-down” approach to drawing conclusions: it begins with a premise or hypothesis and seeks to verify it (or disconfirm it) with newly collected data. Inferences are made based on widely accepted facts or premises. Deduction is idea-first, followed by observations and a conclusion. This form of reasoning is often used in quantitative research and less often in qualitative research. Compare to inductive reasoning . See also abductive reasoning .

A form of reasoning that employs a “bottom-up” approach to drawing conclusions: it begins with the collection of data relevant to a particular question and then seeks to build an argument or theory based on an analysis of that data. Induction is observation first, followed by an idea that could explain what has been observed. This form of reasoning is often used in qualitative research and seldom used in qualitative research. Compare to deductive reasoning . See also abductive reasoning .

An “interpretivist” form of reasoning in which “most likely” conclusions are drawn, based on inference. This approach is often used by qualitative researchers who stress the recursive nature of qualitative data analysis. Compare with deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning .

A form of social science research that generally follows the scientific method as established in the natural sciences. In contrast to idiographic research , the nomothetic researcher looks for general patterns and “laws” of human behavior and social relationships. Once discovered, these patterns and laws will be expected to be widely applicable. Quantitative social science research is nomothetic because it seeks to generalize findings from samples to larger populations. Most qualitative social science research is also nomothetic, although generalizability is here understood to be theoretical in nature rather than statistical . Some qualitative researchers, however, espouse the idiographic research paradigm instead.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|