- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

It's More Than Racism: Isabel Wilkerson Explains America's 'Caste' System

Terry Gross

In her new book, Caste, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson examines the laws and practices that created what she describes as a bipolar, Black and white caste system in the United States. Above, a sign in Jackson, Miss., in May 1961. William Lovelace/Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

In her new book, Caste, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson examines the laws and practices that created what she describes as a bipolar, Black and white caste system in the United States. Above, a sign in Jackson, Miss., in May 1961.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Isabel Wilkerson says racism is an insufficient term for the systemic oppression of Black people in America. Instead, she prefers to refer to America as having a "caste" system.

Wilkerson describes caste an artificial hierarchy that helps determine standing and respect, assumptions of beauty and competence, and even who gets benefit of the doubt and access to resources.

"Caste focuses in on the infrastructure of our divisions and the rankings, whereas race is the metric that's used to determine one's place in that," she says.

Wilkerson notes that the concept of caste has been around for thousands of years: "[Caste] predates the idea of race, which is ... only 400 or 500 years old, dating back to the transatlantic slave trade."

Caste, she adds, "is the term that is more precise [than race]; it is more comprehensive, and it gets at the underlying infrastructure that often we cannot see, but that is there undergirding much of the inequality and injustices and disparities that we live with in this country."

Author Interviews

Great migration: the african-american exodus north.

Wilkerson's 2010 book, The Warmth of Other Suns , focused on the great migration of African Americans from the South to the North during the 20th century. In her new book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, Wilkerson says that acknowledging America's caste system deepens our understanding of what Black people are up against in the United States.

Interview Highlights

On hearing a Nigerian-born playwright say that there are no Black people in Africa

It's so shocking to our ears, because, of course, we say that there is an entire subcontinent of people who we would view as Black, but what she was saying was that until you come to the United States, they themselves do not see themselves as Black, they are Igbo ... or they are Yoruba or whatever it is that they are in terms of their ethnicity and identity.

It is only when they enter into a multilayered caste structure ... a hierarchy such as this, do they then have to think of themselves as Black. But back where they are from, they do not have to think of themselves as Black, because Black is not the primary metric of determining one's identity.

On how being "white" is an American innovation

It's an innovation that is only several hundred years old, dating back to the time of the transatlantic slave trade. And that is because before that time, there were humans on the land wherever they happened to be on this planet, and because of the way people were living on the land, they were merely who they were.

They were Irish or they were German or they were Polish or Hungarian, and only [thought of themselves as white] after the transatlantic slave trade, only after people who had been spread out all over the world converged in this one space — the New World — to create a new country, a new culture where all of these people were then interacting and having to figure out how they were going to relate to one another.

That is when you have a caste system that emerges, a caste system that emerges that instantly relegates those who were brought in to be enslaved ... to the very bottom of the caste system, and then elevated those who looked like those who had who created the caste system — meaning those who were British and Western Europeans — at the very top of the caste system. And anyone who entered that caste system had to then navigate and figure out how were they [were] going to manage, how are they [were] going to survive and succeed in this system. And also upon arrival, discovering that they were assigned to a particular category, whether they [wished] to be in it or not.

That means that until arriving here, people who were Irish, people who were Hungarian, people who were Polish would not have identified themselves back in the 19th century as being white, but only in connection to the gradations and ranking that occurred and was created in the United States — that is where the designation of white, the designation of Black and those in between came to have meaning.

On where people of color who are not Black fit into the caste system

There was a tremendous churning at the beginning of the 20th century of people who were arriving in these undetermined or middle groups that did not fit neatly into the bipolar structure that America had created. And at the beginning of the 20th century, there were petitions to the Supreme Court, petitions to the government, for clarity about where they would fit in. And they were often petitioning to be admitted to the dominant caste.

One of the examples, a Japanese immigrant petitioned to qualify for being Caucasian because he said, "My skin is actually whiter than many people that I identified as white in America. I should qualify to be considered Caucasian." And his petition was rejected by the Supreme Court. But these are all examples of the long-standing uncertainties about who fits where when you have a caste system that is bipolar [Black and white], such as the one that was created here.

On the surprising origin of the term "Caucasian"

Wilkerson won the National Book Critics Circle Award for her book about the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns. Joe Henson/Penguin Random House hide caption

Wilkerson won the National Book Critics Circle Award for her book about the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns.

There was a physician, a German physician in the 18th century who had this obsession with skulls, and he collected these skulls from all over the world and his effort to determine who was supreme in humanity. So he had skulls from all over the world, and he identified the most beautiful skulls as having come from the area around the Caucasus Mountains. And as a result of that, because they were, in his view, so beautiful, he decided to identify this skull as Caucasian clearly, and to name the group to which he belonged as Caucasians.

In other words, this was the group that was the most beautiful and perfect of all groups of humanity. This was a group that he presumed himself to belong to — though he was German. And this was the group that he described as European, and thus the word "Caucasian" actually refers to people who come from the Caucasus Mountains.

Now, what's fascinating about that as well is that the very people who were from that region of the world actually are among those who had the most difficult time gaining entry to the United States as citizens as white in the early 20th century, because they did not qualify based upon the preferences for those who were from Northern European ancestry.

On how the U.S. used immigration as a legal way to maintain the caste system

Code Switch

With trump at the border, a look back at u.s. immigration policy.

Curating the population means deciding who gets to be a part of it and where they fit in upon entry, and so there is a tremendous effort at the end of the 19th century, the beginning of the 20th century, with the rise of eugenics and this growing belief in the gradations of humankind that they wanted to keep the population closer to what it had been at the founding of the country. And so there was an effort to restrict who could come into the country if they were not of Western European descent.

Tremendous back and forth, tremendous efforts on the part of eugenicists who then held sway in the popular imagination, tremendous effort to keep out people who we now would view as part of the dominant group. It was a form of curating who could become a part of the United States and where they would fit in, and they used immigration laws to determine who would be able to get access to that dominant group.

On why the Nazis studied American Jim Crow laws

Eugenics, Anti-Immigration Laws Of The Past Still Resonate Today, Journalist Says

I have to say that my focus was not initially on the Nazis themselves, but rather on how Germany has worked in the decades after the war to reconcile its history. But the deeper that I got, and the more that I looked into this, the deeper I searched, I discovered these connections that I would never have imagined.

It turned out that German eugenicists were in continuing dialogue with American eugenicists. Books by American eugenicists were big sellers in Germany in the years leading up to the Third Reich. And then, of course, the Nazis needed no one to teach them how to hate. But what they did was they sent researchers to study America's Jim Crow laws. They actually sent researchers to America to study how Americans had subjugated African Americans, what would be considered the subordinated caste. And they actually debated and consulted American law as they were devising the Nuremberg Laws and as they were looking at those laws in the United States.

They couldn't understand why, from their perspective, the group that they had identified as the subordinated caste was not recognized in the United States in the same way. So that was the unusual interconnectedness that I never would have imagined.

On the Nazi reaction to America's "one drop rule," which maintained that a person with any amount of Black blood would be considered Black

That idea of the one drop rule, that was viewed as too extreme to [the Nazis]. It was stunning to hear that. ... The Nazis, in trying to create their own caste system, what could be considered a caste system, went to great lengths to really think hard about who should qualify as Aryan, because they felt that they wanted to include as many people as they possibly could, ironically enough, and as they looked at the United States, it did not make sense to them that a single drop of Black blood would make someone Black, that they could not and did not accept. And in defining and creating their own hierarchy, they ended up coming up with a different configuration that actually encompassed more people into the Aryan side than would have been considered than the equivalent would have been in the United States.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz and Molly Seavy-Nesper adapted it for the Web.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Why Is Caste Inequality Still Legal in America?

By Paula Chakravartty and Ajantha Subramanian

Dr. Chakravartty is a professor of media and communication at New York University who has written extensively about race, migration and labor in the United States and India. Dr. Subramanian is a professor of anthropology and South Asian studies at Harvard University and has written extensively about caste and democracy in India.

Caste is not well understood in the United States, even though it plays a significant role in the lives of Americans of South Asian descent. Two recent lawsuits make caste among the South Asian diaspora much more visible. They show that oppressed castes in the United States are doubly disadvantaged — by caste and race. Making caste a protected category under federal law will allow for the recognition of this double disadvantage.

Caste is a descent-based structure of inequality. In South Asia, caste privilege has worked through the control of land, labor, education, media, white-collar professions and political institutions. While power and status are more fluid in the intermediate rungs of the caste hierarchy, Dalits, the group once known as “untouchables” who occupy its lowest rung, have experienced far less social and economic mobility. To this day, they are stigmatized as inferior and polluting, and typically segregated into hazardous, low-status forms of labor.

The Indian government has many laws to combat caste prejudice and inequality. But attempts to provide oppressed castes with protection and redress — through affirmative action, for example — are met with fierce opposition from privileged castes. The past 20 years have also witnessed the rise of Dalit political movements and the emergence of a nascent middle class that has benefited from affirmative action. However, oppressed castes’ claims to dignity, well-being and rights are still routinely met with social ostracism, economic boycotts or physical violence.

Caste continues to operate in America, among the South Asian diaspora, but in a very different legal and economic context. Immigrants from India and other South Asian countries began arriving in large numbers after restrictive immigration policies based on rigid racial hierarchies were changed starting in the second half of the 20th century. These reforms provided opportunities mostly for privileged castes, like our own families, who have used their historical advantages to become an affluent and professionally successful racial minority in the United States.

Oppressed castes are a minority within this minority, and they continue to be subject to forms of caste discrimination and exploitation, as the two lawsuits make clear. Together, these cases show how caste operates within America’s racially stratified work force to create largely hidden, yet pernicious patterns of discrimination and exploitation. In both, the litigants are members of the oppressed caste Dalits.

One case is a discrimination suit filed in June 2020 against the technology conglomerate Cisco Systems Inc. and two supervisors by the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing on behalf of a Dalit engineer. According to the lawsuit, Cisco failed to adequately address caste discrimination by two privileged-caste supervisors. The Dalit engineer alleges that one of the supervisors “outed” him as a beneficiary of Indian affirmative action. The lawsuit says that when he complained to the human resources department, both supervisors retaliated by denying him opportunities for advancement.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation

4. attitudes about caste, table of contents.

- The dimensions of Hindu nationalism in India

- India’s Muslims express pride in being Indian while identifying communal tensions, desiring segregation

- Muslims, Hindus diverge over legacy of Partition

- Religious conversion in India

- Religion very important across India’s religious groups

- Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived

- Across India’s religious groups, widespread sharing of beliefs, practices, values

- Religious identity in India: Hindus divided on whether belief in God is required to be a Hindu, but most say eating beef is disqualifying

- Sikhs are proud to be Punjabi and Indian

- Most Indians say they and others are very free to practice their religion

- Most people do not see evidence of widespread religious discrimination in India

- Most Indians report no recent discrimination based on their religion

- In Northeast India, people perceive more religious discrimination

- Most Indians see communal violence as a very big problem in the country

- Indians divided on the legacy of Partition for Hindu-Muslim relations

- More Indians say religious diversity benefits their country than say it is harmful

- Indians are highly knowledgeable about their own religion, less so about other religions

- Substantial shares of Buddhists, Sikhs say they have worshipped at religious venues other than their own

- One-in-five Muslims in India participate in celebrations of Diwali

- Members of both large and small religious groups mostly keep friendships within religious lines

- Most Indians are willing to accept members of other religious communities as neighbors, but many express reservations

- Indians generally marry within same religion

- Most Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains strongly support stopping interreligious marriage

- India’s religious groups vary in their caste composition

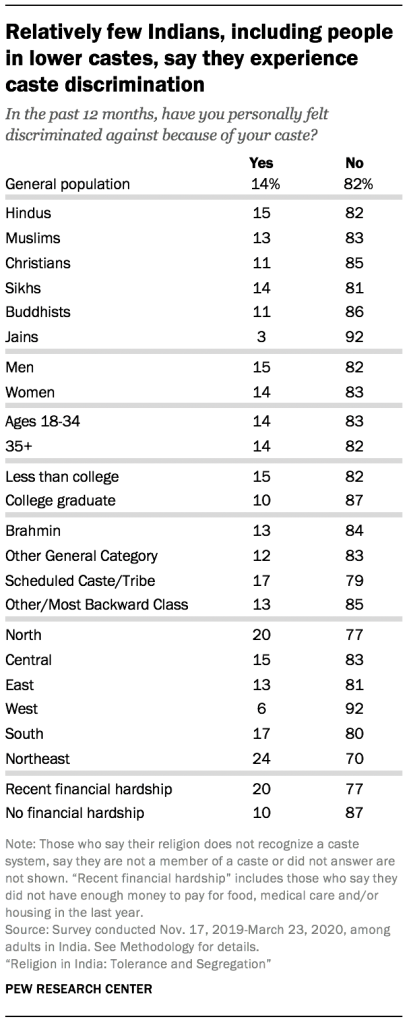

- Indians in lower castes largely do not perceive widespread discrimination against their groups

- Most Indians do not have recent experience with caste discrimination

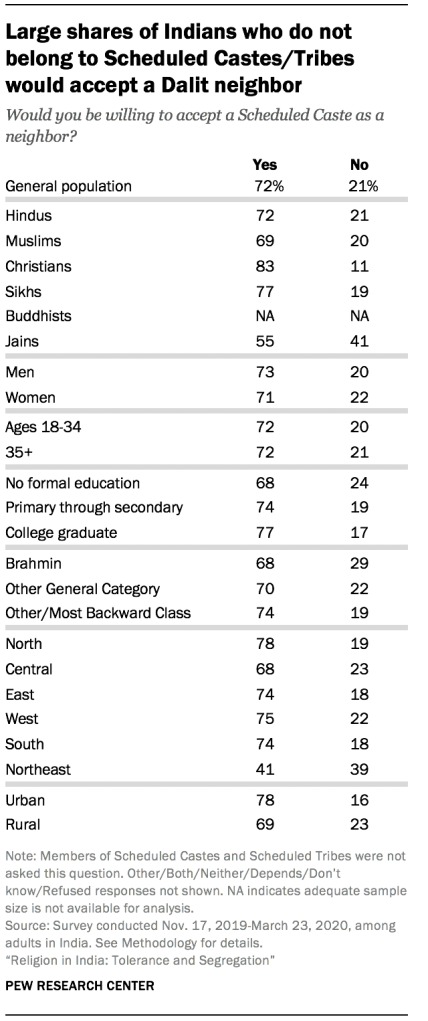

- Most Indians OK with Scheduled Caste neighbors

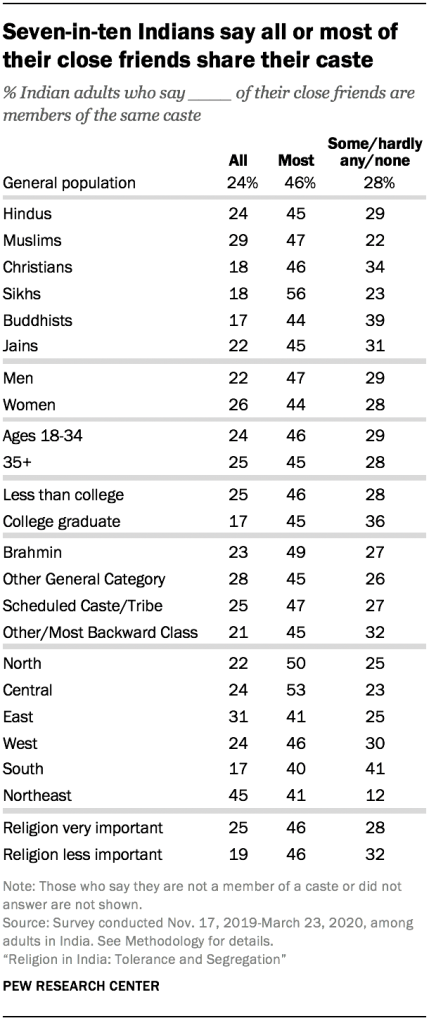

- Indians generally do not have many close friends in different castes

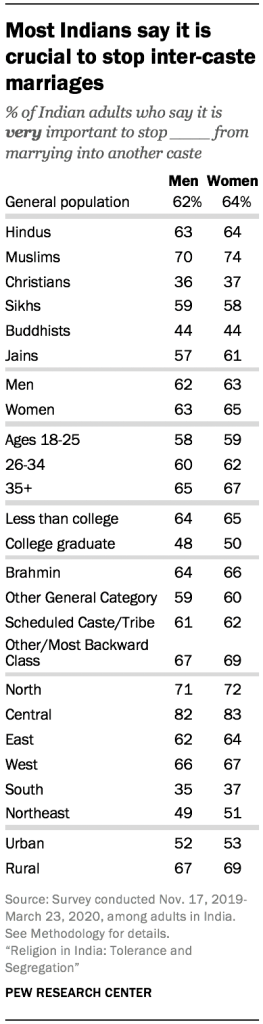

- Large shares of Indians say men, women should be stopped from marrying outside of their caste

- Most Indians say being a member of their religious group is not only about religion

- Common ground across major religious groups on what is essential to religious identity

- India’s religious groups vary on what disqualifies someone from their religion

- Hindus say eating beef, disrespecting India, celebrating Eid incompatible with being Hindu

- Muslims place stronger emphasis than Hindus on religious practices for identity

- Many Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists do not identify with a sect

- Sufism has at least some followers in every major Indian religious group

- Large majorities say Indian culture is superior to others

- What constitutes ‘true’ Indian identity?

- Large gaps between religious groups in 2019 election voting patterns

- No consensus on whether democracy or strong leader best suited to lead India

- Majorities support politicians being involved in religious matters

- Indian Muslims favor their own religious courts; other religious groups less supportive

- Most Indians do not support allowing triple talaq for Muslims

- Southern Indians least likely to say religion is very important in their life

- Most Indians give to charitable causes

- Majorities of Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Jains in India pray daily

- More Indians practice puja at home than at temple

- Most Hindus do not read or listen to religious books frequently

- Most Indians have an altar or shrine in their home for worship

- Religious pilgrimages common across most religious groups in India

- Most Hindus say they have received purification from a holy body of water

- Roughly half of Indian adults meditate at least weekly

- Only about a third of Indians ever practice yoga

- Nearly three-quarters of Christians sing devotionally

- Most Muslims and few Jains say they have participated in or witnessed animal sacrifice for religious purposes

- Most Indians schedule key life events based on auspicious dates

- About half of Indians watch religious programs weekly

- For Hindus, nationalism associated with greater religious observance

- Indians value marking lifecycle events with religious rituals

- Most Indian parents say they are raising their children in a religion

- Fewer than half of Indian parents say their children receive religious instruction outside the home

- Vast majority of Sikhs say it is very important that their children keep their hair long

- Half or more of Hindus, Muslims and Christians wear religious pendants

- Most Hindu, Muslim and Sikh women cover their heads outside the home

- Slim majority of Hindu men say they wear a tilak, fewer wear a janeu

- Eight-in-ten Muslim men in India wear a skullcap

- Majority of Sikh men wear a turban

- Muslim and Sikh men generally keep beards

- Most Indians are not vegetarians, but majorities do follow at least some restrictions on meat in their diet

- One-in-five Hindus abstain from eating root vegetables

- Fewer than half of vegetarian Hindus willing to eat in non-vegetarian settings

- Indians evenly split about willingness to eat meals with hosts who have different religious rules about food

- Majority of Indians say they fast

- More Hindus say there are multiple ways to interpret Hinduism than say there is only one true way

- Most Indians across different religious groups believe in karma

- Most Hindus, Jains believe in Ganges’ power to purify

- Belief in reincarnation is not widespread in India

- More Hindus and Jains than Sikhs believe in moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth)

- Most Hindus, Muslims, Christians believe in heaven

- Nearly half of Indian Christians believe in miracles

- Most Muslims in India believe in Judgment Day

- Most Indians believe in fate, fewer believe in astrology

- Many Hindus and Muslims say magic, witchcraft or sorcery can influence people’s lives

- Roughly half of Indians trust religious ritual to treat health problems

- Lower-caste Christians much more likely than General Category Christians to hold both Christian and non-Christian beliefs

- Nearly all Indians believe in God

- Few Indians believe ‘there are many gods’

- Many Hindus feel close to Shiva

- Many Indians believe God can be manifested in other people

- Indians almost universally ask God for good health, prosperity, forgiveness

- Acknowledgments

- Questionnaire design

- Sample design and weighting

- Precision of estimates

- Response rates

- Significant events during fieldwork

- Appendix B: Index of religious segregation

The caste system has existed in some form in India for at least 3,000 years . It is a social hierarchy passed down through families, and it can dictate the professions a person can work in as well as aspects of their social lives, including whom they can marry. While the caste system originally was for Hindus, nearly all Indians today identify with a caste, regardless of their religion.

The survey finds that three-in-ten Indians (30%) identify themselves as members of General Category castes, a broad grouping at the top of India’s caste system that includes numerous hierarchies and sub-hierarchies. The highest caste within the General Category is Brahmin, historically the priests and other religious leaders who also served as educators. Just 4% of Indians today identify as Brahmin.

Most Indians say they are outside this General Category group, describing themselves as members of Scheduled Castes (often known as Dalits, or historically by the pejorative term “untouchables”), Scheduled Tribes or Other Backward Classes (including a small percentage who say they are part of Most Backward Classes).

Hindus mirror the general public in their caste composition. Meanwhile, an overwhelming majority of Buddhists say they are Dalits, while about three-quarters of Jains identify as members of General Category castes. Muslims and Sikhs – like Jains – are more likely than Hindus to belong to General Category castes. And about a quarter of Christians belong to Scheduled Tribes, a far larger share than among any other religious community.

Caste segregation remains prevalent in India. For example, a substantial share of Brahmins say they would not be willing to accept a person who belongs to a Scheduled Caste as a neighbor. But most Indians do not feel there is a lot of caste discrimination in the country, and two-thirds of those who identify with Scheduled Castes or Tribes say there is not widespread discrimination against their respective groups. This feeling may reflect personal experience: 82% of Indians say they have not personally faced discrimination based on their caste in the year prior to taking the survey.

Still, Indians conduct their social lives largely within caste hierarchies. A majority of Indians say that their close friends are mostly members of their own caste, including roughly one-quarter (24%) who say all their close friends are from their caste. And most people say it is very important to stop both men and women in their community from marrying into other castes, although this view varies widely by region. For example, roughly eight-in-ten Indians in the Central region (82%) say it is very important to stop inter-caste marriages for men, compared with just 35% in the South who feel strongly about stopping such marriages.

Most Indians (68%) identify themselves as members of lower castes, including 34% who are members of either Scheduled Castes (SCs) or Scheduled Tribes (STs) and 35% who are members of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) or Most Backward Classes. Three-in-ten Indians identify themselves as belonging to General Category castes, including 4% who say they are Brahmin, traditionally the priestly caste. 12

Hindu caste distribution roughly mirrors that of the population overall, but other religions differ considerably. For example, a majority of Jains (76%) are members of General Category castes, while nearly nine-in-ten Buddhists (89%) are Dalits. Muslims disproportionately identify with non-Brahmin General Castes (46%) or Other/Most Backward Classes (43%).

Caste classification is in part based on economic hierarchy, which continues today to some extent. Highly educated Indians are more likely than those with less education to be in the General Category, while those with no education are most likely to identify as OBC.

But financial hardship isn’t strongly correlated with caste identification. Respondents who say they were unable to afford food, housing or medical care at some point in the last year are only slightly more likely than others to say they are Scheduled Caste/Tribe (37% vs. 31%), and slightly less likely to say they are from General Category castes (27% vs. 33%).

The Central region of India stands out from other regions for having significantly more Indians who are members of Other Backward Classes or Most Backward Classes (51%) and the fewest from the General Category (17%). Within the Central region, a majority of the population in the state of Uttar Pradesh (57%) identifies as belonging to Other or Most Backward Classes.

When asked if there is or is not “a lot of discrimination” against Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes in India, most people say there isn’t a lot of caste discrimination. Fewer than one-quarter of Indians say they see evidence of widespread discrimination against Scheduled Castes (20%), Scheduled Tribes (19%) or Other Backward Classes (16%).

Generally, people belonging to lower castes share the perception that there isn’t widespread caste discrimination in India. For instance, just 13% of those who identify with OBCs say there is a lot of discrimination against Backward Classes. Members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes are slightly more likely than members of other castes to say there is a lot of caste discrimination against their groups – but, still, only about a quarter take this position.

Christians are more likely than other religious groups to say there is a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in India: About three-in-ten Christians say each group faces widespread discrimination, compared with about one-in-five or fewer among Hindus and other groups.

At least three-in-ten Indians in the Northeast and the South say there is a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes, although similar shares in the Northeast decline to answer these questions. Just 13% in the Central region say Scheduled Castes face widespread discrimination, and 7% say the same about OBCs.

Highly religious Indians – that is, those who say religion is very important in their lives – tend to see less evidence of discrimination against Scheduled Castes and Tribes. Meanwhile, those who have experienced recent financial hardship are more inclined to see widespread caste discrimination.

Not only do most Indians say that lower castes do not experience a lot of discrimination, but a strong majority (82%) say they have not personally felt caste discrimination in the past 12 months. While members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes are slightly more likely than members of other castes to say they have personally faced caste-based discrimination, fewer than one-in-five (17%) say they have experienced this in the last 12 months.

But caste-based discrimination is more commonly reported in some parts of the country. In the Northeast, for example, 38% of respondents who belong to Scheduled Castes say they have experienced discrimination because of their caste in the last 12 months, compared with 14% among members of Scheduled Castes in Eastern India.

Jains, the vast majority of whom are members of General Category castes, are less likely than other religious groups to say they have personally faced caste discrimination (3%). Meanwhile, Indians who indicate they have faced recent financial hardship are more likely than those who have not faced such hardship to report caste discrimination in the last year (20% vs. 10%).

The vast majority of Indian adults say they would be willing to accept members of Scheduled Castes as neighbors. (This question was asked only of people who did not identify as members of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes.)

Among those who received the question, large majorities of Christians (83%) and Sikhs (77%) say they would accept Dalit neighbors. But a substantial portion of Jains, most of whom identify as belonging to General Category castes, feel differently; about four-in-ten Jains (41%) say that they would not be willing to accept Dalits as neighbors. (Because more than nine-in-ten Buddhists say they are members of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes, not enough Buddhists were asked this question to allow for separate analysis of their answers.)

About three-in-ten Brahmins (29%) say they would not be willing to accept members of Scheduled Castes as neighbors.

In most regions, at least two-thirds of people express willingness to accept Scheduled Caste neighbors. The Northeast, however, stands out, with roughly equal shares saying they would (41%) or would not (39%) be willing to accept Dalits as neighbors, although this region also has the highest share of respondents – 20% – who gave an unclear answer or declined to answer the question.

Indians who live in urban areas (78%) are more likely than rural Indians (69%) to say they would be willing to accept Scheduled Caste neighbors. And Indians with more education also are more likely to accept Dalit neighbors. Fully 77% of those with a college degree say they would be fine with neighbors from Scheduled Castes, while 68% of Indians with no formal education say the same.

Politically, those who have a favorable opinion of the BJP are somewhat less likely than those who have an unfavorable opinion of India’s ruling party to say they would accept Dalits as neighbors, although there is widespread acceptance across both groups (71% vs. 77%).

Indians may be comfortable living in the same neighborhoods as people of different castes, but they tend to make close friends within their own caste. About one-quarter (24%) of Indians say all their close friends belong to their caste, and 46% say most of their friends are from their caste.

About three-quarters of Muslims and Sikhs say that all or most of their friends share their caste (76% and 74%, respectively). Christians and Buddhists – who disproportionately belong to lower castes – tend to have somewhat more mixed friend circles. Nearly four-in-ten Buddhists (39%) and a third of Christians (34%) say “some,” “hardly any” or “none” of their close friends share their caste background.

Members of OBCs are also somewhat more likely than other castes to have a mixed friend circle. About one-third of OBCs (32%) say no more than “some” of their friends are members of their caste, compared with roughly one-quarter of all other castes who say this.

Women, Indian adults without a college education and those who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to say that all their close friends are of the same caste as them. And, regionally, 45% of Indians in the Northeast say all their friends are part of their caste, while in the South, fewer than one-in-five (17%) say the same.

As another measure of caste segregation, the survey asked respondents whether it is very important, somewhat important, not too important or not at all important to stop men and women in their community from marrying into another caste. Generally, Indians feel it is equally important to stop both men and women from marrying outside of their caste. Strong majorities of Indians say it is at least “somewhat” important to stop men (79%) and women (80%) from marrying into another caste, including at least six-in-ten who say it is “very” important to stop this from happening regardless of gender (62% for men and 64% for women).

Majorities of all the major caste groups say it is very important to prevent inter-caste marriages. Differences by religion are starker. While majorities of Hindus (64%) and Muslims (74%) say it is very important to prevent women from marrying across caste lines, fewer than half of Christians and Buddhists take that position.

Among Indians overall, those who say religion is very important in their lives are significantly more likely to feel it is necessary to stop members of their community from marrying into different castes. Two-thirds of Indian adults who say religion is very important to them (68%) also say it is very important to stop women from marrying into another caste; by contrast, among those who say religion is less important in their lives, 39% express the same view.

Regionally, in the Central part of the country, at least eight-in-ten adults say it is very important to stop both men and women from marrying members of different castes. By contrast, fewer people in the South (just over one-third) say stopping inter-caste marriage is a high priority. And those who live in rural areas of India are significantly more likely than urban dwellers to say it is very important to stop these marriages.

Older Indians and those without a college degree are more likely to oppose inter-caste marriage. And respondents with a favorable view of the BJP also are much more likely than others to oppose such marriages. For example, among Hindus, 69% of those who have a favorable view of BJP say it is very important to stop women in their community from marrying across caste lines, compared with 54% among those who have an unfavorable view of the party.

CORRECTION (August 2021): A previous version of this chapter contained an incorrect figure. The share of Indians who identify themselves as members of lower castes is 68%, not 69%.

- All survey respondents, regardless of religion, were asked, “Are you from a General Category, Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Class?” By contrast, in the 2011 census of India, only Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists could be enumerated as members of Scheduled Castes, while Scheduled Tribes could include followers of all religions. General Category and Other Backward Classes were not measured in the census. A detailed analysis of differences between 2011 census data on caste and survey data can be found here . ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- Christianity

- International Political Values

- International Religious Freedom & Restrictions

- Interreligious Relations

- Other Religions

- Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

- Religious Characteristics of Demographic Groups

- Religious Identity & Affiliation

- Religiously Unaffiliated

- Size & Demographic Characteristics of Religious Groups

Where is the most religious place in the world?

Rituals honoring deceased ancestors vary widely in east and southeast asia, 6 facts about religion and spirituality in east asian societies, religion and spirituality in east asian societies, 8 facts about atheists, most popular, report materials.

- Questionnaire

- இந்தியாவில் மதம்: சகிப்புத்தன்மையும், தனிமைப்படுத்துதலும்

- भारत में धर्म: सहिष्णुता और अलगाव

- ভারতে ধর্ম: সহনশীলতা এবং পৃথকীকরণ

- भारतातील धर्म : सहिष्णुता आणि विलग्नता

- Related: Religious Composition of India

- How Pew Research Center Conducted Its India Survey

- Questionnaire: Show Cards

- India Survey Dataset

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Caste Discrimination Exists in the U.S., Too—But a Movement to Outlaw It Is Growing

I n late January, California State University added caste to its non-discrimination policy. With more than 437,000 students and 44,000 employees statewide, it is the largest academic institution to do so. But it is not alone. Brandeis University was the first to take this step in 2019. University of California, Davis, Colby College, Colorado College, the Claremont colleges, and Carleton University followed suit. In August 2021, the California Democratic Party added caste as a protected category to their Party Code of Conduct. And in December 2021, the Harvard Graduate Student Union ratified its collective bargaining agreement, which included caste as a protected category for its members.

What is caste? How is caste discrimination expressed? And why are protections against caste discrimination an urgent issue in the U.S.?

Caste is a descent-based structure of inequality in which privilege works through the control of land, labor, education, media, white-collar professions and political institutions. Some seventy years after independence from colonial rule, the specter of casteism continues to haunt South Asia. The unequal inheritances of caste shape every aspect of social life, from education to marriage, housing, and employment. Caste discrimination still plagues all South Asian societies, including India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. To this day, oppressed castes are subject to stigma on the basis of perceived social and intellectual inferiority, and often consigned to the most exploitative segments of the labor market. This is especially true of Dalits, which is the broad term for the community that occupies the bottom rung of the caste ladder and suffers the unique stigma of untouchability. Dalits continue to face pervasive violence, humiliation, and exclusion. The coronavirus pandemic has only amplified the practice of ‘untouchability’ through the segregating and shunning of stigmatized groups.

The ugly realities of caste inequality and discrimination also shape the lives of South Asian communities in the diaspora. In the U.S., two recent lawsuits have exposed the pervasiveness of caste dynamics far beyond the borders of South Asia.

The first lawsuit was filed in June 2020 against the software company Cisco Systems. Brought by the California Department for Fair Employment and Housing, it alleges that the company failed to address caste discrimination against an employee from the Dalit caste by two supervisors from more privileged caste backgrounds.

The second was filed in May 2021 against the Hindu trust BAPS (Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha), a nonprofit that since 2009 has had the status of a 501 (c)(3) organization. It was brought by lawyers representing a group of Dalits who claim that they were brought to the United States under the R1 visa for religious workers and forced into underpaid, exploitative construction work on a Hindu temple in New Jersey. Both lawsuits reveal practices of caste discrimination and exploitation within America’s racially stratified workforce.

These lawsuits reflect long-standing trends within U.S. immigration. The 1965 Hart-Cellar Act legalized a preference for professional class migrants, such as doctors and engineers, from all over the world, even as it sought to undo the racial prejudices of the immigration laws that it replaced. The shift in immigration policy ensured that South Asians from dominant castes—the ones with privileged access to education and white-collar professions—were overrepresented in the United States in comparison to the South Asian population at large. The caste inequities of Indian education have allowed these groups to use their privilege to immigrate and succeed professionally.

The highly selective character of the professional South Asian American population has therefore created the conditions for caste bias and discrimination in hiring and promotion. This is especially the case in the U.S. technology sector, which has significant privileged caste representation. Although the first to be made public, the experience of the Dalit employee in the Cisco case is not uncommon. Following the filing of the case, Dalit tech workers employed in some of the biggest companies have come forward to attest to rampant caste bias. Most feel compelled to conceal their caste identities and pass as non-Dalits in workplaces that they share with members of more privileged castes. They experience these workplaces as minefields where colleagues from privileged castes might probe their backgrounds to find out their origins and where a misstep can lead to exposure and stigma. These workers indicate a clear preference for non-South Asian supervisors whose ignorance of caste ensures fairer treatment. While such testimonies provide an important starting point for understanding the employment experiences of oppressed castes in the U.S., more data on caste demographics is needed to reveal the scale of the problem.

These lawsuits underscore the need for adding caste to the existing set of categories that are protected against discrimination under federal law. The legal recognition of caste as a protected category will destigmatize caste identification and ensure that vulnerable caste groups do not feel threatened when revealing their identities. Most importantly, making caste a protected category would recognize a form of discrimination that deeply affects marginalized South Asian caste groups—highlighting prejudices that have been invisible for too long.

However, there are some South Asian Americans who argue that the legal recognition of caste discrimination would be harmful to South Asians in the U.S. One of the most prominent groups that has come out against adding caste to U.S. anti-discrimination law is the Hindu American Foundation (HAF). HAF contends that doing so will “single out and target Indian Americans for scrutiny and discrimination.” In her testimony at an April 29 public hearing on a proposal to recognize caste discrimination in Santa Clara, California, HAF Executive Director, Suhag Shukla, characterized caste as “a stereotype.” She asserted that if caste were added as a protected category, it would be used to “uniquely target South Asians, Indians, and Hindus for ethno-religious profiling, monitoring, and policing.” HAF also opposes the legal recognition of caste on the grounds that doing so will “target” the Hindu religion.

But caste is not a mere stereotype about South Asian societies. It is a lived reality that promotes unequal access to life, livelihood, and the capacity for human flourishing. Furthermore, caste must not be conflated with a nationality, ethnicity, or religion. Scholars have long shown, and human rights reports document , that caste exists across all South Asian nationalities, ethnicities, and religions. Testimonies at the Santa Clara hearing also confirmed this reality by attesting to casteism among South Asian Christians, Muslims, and Hindus alike. Spurious arguments about “Hinduphobia” should thus not be used to shield caste from scrutiny.

HAF’s arguments assume that dignity and rights are a zero-sum game. Extending protections to oppressed castes will not scapegoat Hindus, Indians, and South Asians any more than extending protections to women scapegoats men. To the contrary, acknowledging the realities of caste discrimination and any actions for accountability and justice that follow upon it would only expand the commitment to equal rights, inclusion, and dignity.

Opponents of making caste a protected category also argue that it would force South Asian Americans and their children to think of themselves in terms of caste identity. At the Santa Clara public hearing, for instance, several individuals speaking against the proposal testified that, as Americans, they no longer identify as members of castes. Privileged castes in the United States may well insist that they do not see or believe in caste. They may well believe that caste classification would impose an identity that they do not claim. But just as race-blindness does not erase racial privilege or disadvantage, caste-blindness does not erase caste privilege or disadvantage. Indeed, the claim to being caste-blind is itself an expression of privilege. As is clear from Dalit testimonies, oppressed castes do not have the luxury of caste blindness.

Caste and race cannot and should not be conflated. Yet, a broad parallel may be drawn between the experiences of racial minorities and oppressed caste groups in the U.S. While members of South Asian American communities rightly draw attention to the long history of racial exclusion and discrimination they have experienced in the U.S., those of privileged caste backgrounds simultaneously resist acknowledging the abiding ugliness of caste discrimination within their communities.

Unfortunately, it is this very history of racial discrimination that is now being wielded against protections for oppressed castes. HAF even contends that making caste a protected category would perpetuate colonial violence. In his testimony in Santa Clara, HAF Managing Director, Samir Kalra, stated that caste is a “British created legal category” and an identity “that was forced on South Asians.” He and other HAF members insist that caste is a colonial invention that was and could again be used as a weapon of white supremacy. But caste is a power difference that existed well before colonialism and did not end with it. As noted in a recent scholarly article, caste has long been “ a total social fact ” in South Asian societies. The Indian Constitution recognizes the deep history of caste inequality and has enacted various laws to combat and correct it. The Cisco and BAPS lawsuits demonstrate that caste inequality and discrimination have been carried by South Asians to the United States. Should different rules apply here simply because South Asians are a racial minority?

The same South Asian American groups that equate caste protections in the US with “Hinduphobia” also oppose any criticism of Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, the political movement that has captured state power in India. For instance, HAF’s founder, Mihir Meghani, is the author of “Hindutva – the Great Nationalist Ideology,” an essay that was published on the website of India’s ruling party, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. After the election of Narendra Modi in 2014, HAF has also lobbied U.S. lawmakers to adopt pro-Indian Government positions on the abrogation of the special status of the State of Jammu and Kashmir and on the Citizenship Amendment Act, a discriminatory law targeting Muslims.

But just as caste protections are not anti-Hindu, neither is criticism of Hindutva. Hindutva is an authoritarian political ideology aimed at transforming India from a secular democracy to a Hindu majoritarian country where Muslims, Christians, and other religious minorities are relegated to second-class citizenship. Under the current Hindu nationalist government in India, there has been a precipitous rise in religious and caste violence targeting Muslims, Christians, and Dalits and widespread crackdowns on dissenters who are languishing in prison without due process. South Asian American groups like HAF are thus engaged in a form of double-speak: they weaponize religious and racial minority protections in the U.S. while defending majoritarianism in India.

By twisting anti-discrimination protections for oppressed castes into racial and religious discrimination, those who oppose making caste a protected category distract attention from the pressing problem of caste in America. This defense of minority rights might appear progressive but we must recognize it for what it is: a defense of caste privilege by diasporic South Asians who are its beneficiaries. As a minority within a minority in the U.S., oppressed castes must get the recognition and protection they deserve.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Introducing TIME's 2024 Latino Leaders

- How to Make an Argument That’s Actually Persuasive

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- The Ordained Rabbi Who Bought a Porn Company

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

The Constitutionality of Prohibiting Caste Discrimination

Guha Krishnamurthi is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law. He thanks Kevin Brown, Charanya Krishnaswami, Chan Tov McNamarah, Alex Platt, Peter Salib, Joe Thai, attendees of the University of Maryland Carey School of Law Comparative Constitutional Democracy Colloquium for helpful comments, and the editors of the Law Review Online.

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Constitutionality of Prohibiting Caste Discrimination on Facebook

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Constitutionality of Prohibiting Caste Discrimination on Twitter

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Constitutionality of Prohibiting Caste Discrimination on Email

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Constitutionality of Prohibiting Caste Discrimination on LinkedIn

The problem of caste discrimination has come into sharp focus in the United States. In the last few years, there have been several high-profile allegations and cases of caste discrimination in employment and educational settings. As a result, organizations—including governmental entities—are taking action, including by updating their rules and regulations to explicitly prohibit discrimination based on caste and initiating enforcement actions against alleged caste discrimination. Most prominently, the City of Seattle became the first U.S. city to amend its local antidiscrimination ordinance to add caste as a protected category.

In response to such government action, questions have arisen about the constitutionality of prohibiting caste discrimination. Opponents principally argue that recognizing caste discrimination violates the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment because governmental entities demean religions, like Hinduism, in doing so. In this Essay, I explain that governments can recognize and remedy caste discrimination consistent with the First Amendment. Remedying caste discrimination does not require disparaging any religion. Insofar as it is necessary to contextualize and remedy instances of discrimination, governmental entities may reference religion, but as a constitutional matter they should refrain from unnecessarily disparaging religion. As with other forms of discrimination, our Constitution empowers the government to protect individuals from the effects of caste discrimination.

Introduction

Over the last three years, the issue of caste discrimination has come into sharp focus in the United States. In the summer of 2020, there was a high-profile case of alleged caste discrimination arising out of Silicon Valley. An employee of Cisco Systems, Inc., hailing from a Dalit background, alleged that he had been paid less, deprived of opportunities, and denigrated due to his caste status. Dalits were once referred to as “untouchables” under the South Asian caste system ; they were and are subject to grievous caste-based oppression in India and elsewhere in the subcontinent. The California Civil Rights Department (CRD), formerly the California Department of Fair Education and Housing, brought a case on behalf of the employee and the issue is still being litigated . Subsequently, numerous individuals have shared their stories of being subject to caste discrimination in employment, educational settings , social settings , and beyond . As a result, scholars have written about the ability of current law to address claims of caste discrimination. And we are seeing more cases of alleged caste discrimination coming to the courts.

Several organizations have taken steps to recognize caste discrimination and to pave pathways for remedies. Universities, including Brandeis University , Brown University , the University of California at Davis , and the California State University system , have added caste as a protected category to their antidiscrimination codes. The Santa Clara Human Rights Commission held public hearings to consider adding caste as a protected category. The City of Seattle became the first U.S. city to add caste as a protected category to its local antidiscrimination ordinance. And, most recently, the California State Legislature is considering proposed legislation S.B. 403 that would ban caste discrimination statewide.

By and large, the public response to these systemic changes has been positive. There is overwhelming consensus that caste discrimination is morally wrongful and socially harmful, and that recognizing and remedying instances of caste discrimination is appropriate. And, as noted, many institutions have pursued this through explicit changes to their antidiscrimination policies and rules.

That said, with respect to governmental action, some objectors have expressed concern that explicitly recognizing caste as a protected category may cause constitutional problems . 1 Specifically, objectors argue that recognizing caste discrimination violates the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause.

In this Essay, I address these putative constitutional violations. I begin by observing that caste is a distinct category and so there is good reason to recognize it separately from religion. With that in mind, I examine how legislation and other government action prohibiting caste discrimination may be pursued in accord with the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause.

I. Caste Discrimination: Reasons for Special Recognition

Caste is a structure of social stratification that is characterized by hereditary transmission of a set of practices, often including occupation, ritual practice, and social interaction. There are various social systems around the world that have been described as “caste” systems, of which the South Asian caste system is most prominent. Across these systems, including in South Asia, caste is often related to concepts of ritual purity and pollution, and serves as the basis for discrimination, and indeed severe oppression.

Charanya Krishnaswami and I , as well as other scholars, have argued that caste discrimination may be cognizable under Title VII under race, national origin, and—in the appropriate factual case—religion. But those arguments are still untested in the courts, and the comparatively unique nature of the category of caste does suggest that there is value in recognizing caste with particularity, since it may otherwise escape recognition under our current legal frameworks.

Notwithstanding arguments that caste may be covered under existing legal frameworks, there are good reasons to recognize caste discrimination with particularity. The nature of caste as a category is distinctive: it does not squarely fit within race, spans various religions, and is not generally considered an ethnicity. Thus, caste discrimination might not be based on the commonly understood categories of race, color, national origin, or ethnicity. Furthermore, caste status may cross religious lines, and instances of caste discrimination might be unrelated to one’s religion. However, caste is a complex that does involve, inter alia, ancestral and endogamous relations, historic occupation, religious background, and native language. These facts may obfuscate its fit within recognized categories of antidiscrimination law.

Moreover, recognizing caste with particularity would obviate putative arguments reducing caste to socioeconomic status. The implication of such arguments is that because socioeconomic status generally does not receive protection under antidiscrimination law, neither should caste. Setting aside the question of whether socioeconomic status should be protected, caste is simply not reducible to socioeconomic status. Even if one can change his or her socioeconomic status, that will often not impact his or her caste status—which is notoriously rigid. Caste is an immutable characteristic, just like those traditionally protected by antidiscrimination law.

II. Recognizing Caste Discrimination Does Not Offend the Establishment Clause

Some of those who object to explicitly recognizing caste discrimination contend that this recognition reaches a constitutional dimension, raising concerns that sound in the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause. In my review, I have not yet found these concerns fully articulated. 2 Thus, I describe these concerns in the most charitable, developed way that I can, noting where there are gaps.

With respect to the Establishment Clause, the objectors’ argument appears to be that, in the course of recognizing caste discrimination, the government makes statements—whether in a statute or in the course of enforcement actions—that Hinduism involves caste at some core or innate level. These statements, the objectors claim, are false and denigrating of Hinduism, and consequently are an Establishment Clause violation .

A. The Supreme Court’s Establishment Clause Jurisprudence

The Establishment Clause forbids “government speech endorsing religion.” This means that “when the government speaks for itself it must carefully avoid expressing favoritism for a particular religious viewpoint.” However, “[t]he Establishment Clause does not wholly preclude the government from referencing religion.” Indeed, in Stone v. Graham (1980), the Supreme Court observed that “the Bible may constitutionally be used in an appropriate study of history, civilization, ethics, comparative religion, or the like” in public schools. A prohibition on all reference to religion by governmental entities would “raise substantial difficulties as to what might be left to talk about . . . [and] it would require that we ignore much of our own history and that of the world in general.” Instead, the Establishment Clause requires that the government espouse neutrality between different religions.

We find ourselves at a moment of flux in the Supreme Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence. Under the longstanding test from Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), “a government act is consistent with the Establishment Clause if it: (1) has a secular purpose; (2) has a principal or primary effect that neither advances nor disapproves of religion; and (3) does not foster excessive governmental entanglement with religion.” In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), the Supreme Court abandoned the Lemon test in favor of a test that looks to “historical practices and understandings.” It is not yet clear what that test means, but the opinion may suggest that the Court is generally less inclined to find that government action violates the Establishment Clause.

Relevant here as well is the Court’s decision in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018). That case concerned a baker who refused to provide a wedding cake to a gay couple. The Colorado Civil Rights Commission determined that the baker violated Colorado’s antidiscrimination law and gave the baker specific orders on how to comply. On review as to whether this violated the baker’s Free Exercise rights, the Supreme Court ruled against the Commission on the basis that the Commission’s statements expressed a hostility toward religion. Indeed, the Court noted that it may have ruled for the Commission had it expressed neutrality toward religion. Here too, the full import of the Supreme Court’s holding is difficult to discern, but it appears that the Court signaled a sensitivity to and vigilance for government hostility to religion. 3

One way of resolving the latent tension in the Court’s recent cases, where the Court is seemingly both expanding and contracting the capacity for government action to engage with religion, is to understand the Court as willing to give the government more breadth in its conduct touching on religion so long as the government does not engage in hostility toward religion (or particular religions). Admittedly, this is speculation, hoping for consistency.

Government actions, such as legislation or enforcement actions, that prohibit caste discrimination as part of civil rights laws will likely stand under the Court’s current jurisprudence. Though the exact contours of the Kennedy test remain to be decided, it appears that the Court has expanded governments’ abilities to engage with religion, beyond the strictures of the Lemon test. Ultimately, it seems likely that when government entities act to prohibit discrimination, including caste discrimination, they may reference religion where necessary, but comments that disparage religion might run afoul of the Establishment Clause. Consequently, the more that government entities make statements about religious beliefs, such as about Hinduism, the more they incur constitutional risks.

B. Caste and Religion

As an initial matter, we should observe that prohibiting and remedying caste discrimination, in employment and places of public accommodation, for example, does not require the government to make denigrating statements about any religion, including Hinduism. (And, though not religions, the government need not make any denigrating claims about Indian culture or South Asian culture, either.) The government need not determine the genesis of the concept of caste in order to recognize that there are, in particular societies and communities, extant social orderings of caste. Indeed, caste discrimination occurs in various religious communities in South Asia, not just Hinduism. Thus, it is not true that recognizing caste discrimination per se denigrates Hinduism in particular.

Now, government entities considering prohibiting caste discrimination have in fact made statements that the caste system has relationships with Hinduism. Most prominently, the California CRD referred to caste as a “strict Hindu social and religious hierarchy” and the City of Seattle recited that caste was a “religiously sanctioned social structure of Hinduism.” Objectors contend that these statements convey that caste is an inextricable or foundational part of Hinduism. These statements, they contend, are both false and unconstitutionally derogatory of Hinduism. This appears to be the strongest basis for the Establishment Clause challenge, for the government does violate the Establishment Clause if it disparages any religion, including Hinduism. 4

As a factual matter, historically the institution of caste has had relationships with Hindu religious tradition and practice. Whether such relationships are fundamental to, or a perversion of, Hinduism are separate questions. As noted, governmental entities need not take a position on them. There are plausible readings of the statements by the California CRD and City of Seattle that suggest they have not done so—rather their claims may simply convey that, as a historical matter, there have been relationships between the institution of caste and the Hindu religion, the predominant religion of South Asia. But objectors disagree: they maintain that these statements wrongly imply that caste is fundamental to Hinduism, and as a result they unconstitutionally tread on religion.

Thus, the question remains whether the government action of making such statements about Hinduism in the course of legally recognizing caste discrimination is constitutional. In the absence of further guidance from the Court, we can first consider how such government action would have fared under the Lemon test. That is, because the Court in Kennedy arguably expanded the ability for government action to engage with religion, if this government conduct passes muster under the Lemon test, it a fortiori should stand under the Kennedy test.

C. Applying the Lemon Factors

On the first Lemon factor, the government action has a secular purpose—to ensure that individuals are not discriminated against on bases that relate to core features of their identity. It is the same secular purpose that animates government action against discrimination on the basis of race, religion, and sex.

On the second factor, such action does not have a principal or primary purpose of disapproving of religion—as said before, it is to eradicate a form of invidious discrimination. To be clear, on certain sets of facts, it might be that some governmental entity is primarily intending to disparage a particular religion, and if so, then that action may fail the Lemon test. But the mere fact of prohibiting caste discrimination does not evince such intent.

This brings us to the third factor, whether there is an excessive entanglement with religion. Both the California CRD and the City of Seattle have made putative statements of historical fact about the relationship between the caste system and Hinduism—that caste is a “ strict Hindu social and religious hierarchy ” and a “ religiously sanctioned social structure .” We needn’t seek to resolve the factual accuracy of the statements—which will inevitably be contentious. Importantly, however, the fact that some individuals disagree with or take offense at the government’s statements cannot be enough to render the government speech an Establishment Clause violation. Given that matters of religion are contentious, that would render any government reference to religion unconstitutional. But as the Court held in Stone v. Graham (1980) that is not the case—the Court there held that religious matters may be constitutionally referenced in appropriate settings by government actors. Thus, there is a strong argument that government entities can reference what they understand to be the relationship between discrimination and religion. And since the Kennedy test is arguably broader than Lemon in permitting government action, there is a strong argument that government action here is a fortiori permitted.

At the same time, the references to Hinduism here are not without constitutional risk. As noted, the Supreme Court held in Masterpiece Cakeshop that in enforcing antidiscrimination laws that may conflict with religious beliefs, government enforcement authorities must express neutrality toward religion. Here, it is possible that a court might rule that these statements do express hostility toward religion. Indeed, the fact that these statements do not appear to be necessary to effectuate prohibitions on caste discrimination may bolster such a determination. That said, insofar as government reference to religion is necessary to explain caste discrimination, either in general or in a particular instance, a court is unlikely to hold such government action unconstitutional, because the government does have a compelling interest in preventing invidious discrimination , and thus the government action will meet strict scrutiny.

D. Applying “Historical Practices and Understandings”

Finally, we can ask how the Court’s appeal to “historical practices and understandings” in Kennedy may bear on these questions. With respect to the argument that prohibiting caste discrimination is per se an excessive entanglement with religion, “historical practices and understandings” suggest that governmental action prohibiting discrimination is appropriate. The Reconstruction Amendments ( Thirteenth , Fourteenth , and Fifteenth ) allow government regulation prohibiting discrimination under race and lineage. Moreover, in Bob Jones University v. United States (1983), the Court rejected the argument that antidiscrimination regulation—there against racial discrimination—violates the Establishment Clause if it disfavors religions with beliefs against “racial intermixing.” Thus, government action prohibiting caste discrimination should not run afoul of the Establishment Clause. With respect to government statements about religion in antidiscrimination laws, we simply do not have much data. On my review, no case citing Kennedy has addressed this question. Ultimately, the question is likely to be governed by the aforementioned principles—that the government may reference religion, but not with hostility. And on that front, government actors would be wise to avoid any unnecessary references to religion.

To be clear, this may not be without cost. That is, by avoiding references to religion, a government entity may fail to fully contextualize and historically ground the nature of the discrimination. Consequently, among other things, this may hinder the government’s ability to educate and to recognize dignitary harms. That is a trade-off, between avoiding constitutional risk and pursuing educational and dignitary goals, for government actors to weigh. 5

III. Recognizing Caste Discrimination Does Not Impair Free Exercise

Next, the objectors argue that by legally prohibiting caste discrimination, the government is prohibiting individuals from practicing their religion freely. This claim is not usually made to complain specifically about the prohibition on caste discrimination—there is broad consensus that caste discrimination is wrongful. Rather, complainants are claiming that caste discrimination is rare , that regulating caste discrimination as if it were common is a misrepresentation of Hindu culture, and that such regulation may have unintended effects that bring improper scrutiny of Hindus and potentially infringe on religious practice.

The problem is that it is unclear what legitimate religious practices might be infringed upon. As noted, most objectors are not asserting that they have, or should have, a legal right to engage in caste discrimination. But it is not at all apparent how prohibiting caste discrimination infringes on any religious beliefs if the religious adherents are not aiming to discriminate on the basis of caste. The onus is on the objectors to articulate how prohibitions on caste discrimination would specially infringe on their rights to religious practice. Indeed, the consensus view among Hindu adherents is that caste discrimination is not legitimately part of Hindu practice. But then why would banning caste discrimination impose on Hindu practice?

It is worth noting that prohibitions on discrimination are generally limited in their scope—confined to the areas of hiring, employment, housing, and places of public accommodation. Such legislation does not prevent private citizens from associating as they wish in their private lives.

Moreover, there are generally exceptions in civil rights legislation, like the ministerial exception and the bona fide occupational qualification exception, for religious entities to discriminate on otherwise prohibited bases in religious matters. For example, one concern might be about how prohibiting caste discrimination impacts hiring clergy. That is, certain castes are associated with religious ritual practice, and priests and clergy are often hired based on their familiarity with that ritual practice. In hiring clergy, religious institutions may hire, by intention or by practice, only from particular castes. This is true in certain Hindu sects, as well as in other religious sects across the subcontinent. The prototypical example is that a Hindu temple may hire a priest, who traditionally will be from a set of castes. That said, current law expressly contemplates this scenario and immunizes the religious entities from liability. And without such exemptions for religious entities, any such legislation will likely be unconstitutional , at least insofar as it applies to religious entities. Further still, most recently, the Supreme Court, in 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (2023), has set forth a First Amendment limitation on public accommodation laws, holding that the government may not compel an individual to engage in expressive conduct with which he or she disagrees. Thus, while public accommodation laws remain generally constitutional, they cannot force individuals to provide services involving expressive conduct they find disagreeable.

Insofar as claimants are arguing that civil rights laws regulating behavior in the scope of hiring, employment, housing, places of public accommodation, and the like infringes on religious freedom, these claims are legally incorrect and will fail. Consider the analogy to, say, race discrimination: a claimant who asserts that civil rights laws prohibiting race discrimination in employment prevent the claimant’s free exercise of their religion because that religion requires or endorses race discrimination. This claim would lose, as it has before . Indeed, a contrary result—holding that recognizing caste discrimination in the scope of civic and public behavior infringes free exercise rights—would threaten all civil rights protections, and that is an absurdity.

To this point, the Supreme Court’s words in Bob Jones University are instructive: the government’s “fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education” outweighs the interests of religious exercise that perpetuate such discrimination. Thus, with exceptions that allow for religious exercise and free speech, the Supreme Court held in 303 Creative , that public accommodation and antidiscrimination laws are constitutionally valid and indeed “vital . . . in realizing the civil rights of all [those protected by the Constitution].”

In light of current precedent and barring a sea change in antidiscrimination law, complaints that legislation and other government action to eliminate caste discrimination burden free exercise will fail as a matter of constitutional law. Laws against caste discrimination—like laws against discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, and national origin—do not offend free exercise, and the overriding interest in eliminating discrimination outweighs any contrary claim of religious exercise. 6

After several high profile accounts of caste discrimination in the United States, governmental entities are taking action, including by bringing cases alleging, and passing legislation prohibiting, caste discrimination. This Essay has detailed how governmental entities can act against caste discrimination without violating the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause. Caste discrimination, like all forms of invidious discrimination, is a scourge. And as with other forms of discrimination, our Constitution empowers the government to protect individuals against the effects of caste discrimination .

Guha Krishnamurthi is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law. He thanks Kevin Brown, Charanya Krishnaswami, Chan Tov McNamarah, Alex Platt, Peter Salib, Joe Thai, attendees of the University of Maryland Carey School of Law Comparative Constitutional Democracy Colloquium for helpful comments, and the editors of the Law Review Online .

- 1 These objectors also raise concerns that calling out caste specifically has the potential to denigrate Hinduism, (East) Indians, and South Asians more broadly, at a time when there is rampant anti-Hindu bigotry and anti-Asian racism. I think these are serious concerns, but they are possible to address. In general, I believe it is possible to recognize and remedy caste discrimination without perpetrating other forms of bigotry and discrimination. Here I focus on the constitutional arguments.

- 2 The most fulsome articulation is in the Hindu American Foundation (HAF) complaint.

- 3 The Supreme Court recently decided 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis (2023), where it considered the same antidiscrimination law at issue in Masterpiece Cakeshop . 303 Creative concerned whether Colorado, through its public accommodation law, could compel a website designer to design wedding websites for gay couples. While affirming the general constitutionality of public accommodation laws, the Court held that such laws are limited by the First Amendment. Specifically, the government cannot, pursuant to such public accommodation laws, compel individuals to engage in expressive conduct with which the putative speaker would disagree.

- 4 It is not clear that these statements about the relationships between caste and Hinduism are necessary for legally recognizing caste discrimination. If they are unnecessary, then the Establishment Clause challenge could be obviated by simply removing these statements. That said, these statements—or ones like them—may be necessary to contextualize caste discrimination, either generally or in specific instances. In that case, we still must resolve the legal question.