Jotted Lines

A Collection Of Essays

Singin’ in the Rain: Summary & Analysis

Summary: .

Singin’ in the Rain opens at the 1927 premiere of The Royal Rascal, a costume drama starring above-the-credit silent film stars Don Lockwood and Lina Lamont. On the red carpet, Don tells the adoring crowds about his training in the arts of high culture, framed by the motto, ‘Always dignity’. A montage shows us the real story: pool hall dancer; beer hall fiddle player; performer in low-rent vaudeville houses; a film career that began when Don replaced a stunt-man injured on the job. We also learn why Don despises his co-star, Lina Lamont. After the premiere, Don meets and falls for Kathy Selden, a nightclub performer and aspiring actress. Stunned by the monumental success of The Jazz Singer, Monumental Pictures bets that Lockwood and Lamont can make the transition to sound. When their first effort, The Duelling Cavalier, flops, Don, Kathy, and Don’s sidekick Cosmo Brown decide to remake The Duelling Cavalier as a musical, with Kathy acting as a vocal double for Lina Lamont. Singin’ in the Rain closes at the opening of The Dancing Cavalier. A coda reveals a billboard advertising Monumental Pictures’ next blockbuster, a Lockwood/Selden musical called Singin’ in the Rain.

Singin’ in the Rain holds a privileged place in the canon of American movies, comparable to the places held in the rock and roll canon by Elvis Presley and the Beatles. Among the various top-10, -25, -100 lists on which this 1952 nostalgia fest has appeared the most emblematic (and most frequently cited) may be Sight & Sound’s 1982 poll of critics for the 10 best movies of all time: Singin’ came in fourth; no other musicals made the list. Indeed, while musicals were among the most popular forms of Hollywood entertainment during the 1930s, 40s and 50s, and the genre remains beloved among devoted cinephiles, musicals tend to be marginal in film surveys. Dramas, melodramas, and comedies dominate this and most comparable lists, along with representative thrillers and Westerns and the occasional science fiction or horror film. Musicals are often cloying; their plots challenge even the most devoted viewer’s capacity to suspend disbelief; the music doesn’t always age well. What makes Singin’ in the Rain different?

To address this question, it’s worth asking another question: what is a musical? A few American films offer points of comparison. Casablanca (1942), many people’s favourite movie, includes a good deal of diegetic music; five different songs are performed in their entirety within the imaginary world of the film. ‘As Time Goes By’ and ‘La Marseillaise’ provide crucial thematic structure. But most people would not call Casablanca a musical.

One cannot define musicals as movies in which characters sing and/or dance without any plot motivation. The question of the relationship between musical numbers and the surrounding plot (if there is any) is often complex. In ‘integrated’ musicals songs advance plot or develop a character in various degrees, while revues hardly have a plot. But distinctions are often not that clear. Backstage musicals, such as Gold Diggers of 1933, deal with the problem of characters spontaneously breaking into song or dance by locating their plot in the entertainment world. Nor can we limit the definition to movies, like West Side Story, which feature original music (original, in this case, to the stage show on which the film is based). Of the 12 songs performed in Singin’ in the Rain, 9 appeared in earlier MGM musicals. Only two – ‘Moses Supposes’ and ‘Make ‘em Laugh’ – were written for Singin’. (Even this is a stretch. ‘Make ‘em Laugh’ has virtually the same musical structure as Cole Porter’s ‘Be a Clown’, the finale of The Pirate (Vincente Minnelli, 1948).)

Singin’ is the last, and best, of a post-Second World War sequence of what are now called juke-box musicals. Warner Brothers started the trend with Night and Day (1946), a sanitised and fictionalised version of the life of Cole Porter. An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain, both produced by the Arthur Freed unit, both starring Gene Kelly, represent the most successful examples of the MGM jukebox musical. American is built around a catalogue of songs composed by George Gershwin with lyrics by Ira Gershwin. Singin’ is built around songs composed by Herb Nacio Brown, with lyrics by Arthur Freed. While neither is a biopic of the Night and Day genre, Singin’ glorifies producer Freed – who began his MGM career as a lyricist – and Kelly – whose name appears in the credits three times: as above-the-credits star, as choreographer (with Stanley Donen), and as co-director (also with Donen).

Of course, this movie does more than glorify its creative team. Singin’ in the Rain is about movie magic. Set in the historical moment when sound film threatened the supremacy of silent film, this movie mythologises the development of the movie musical, and presents movie magic as evidence of film’s superiority to the cinema’s new, terrifying, and never-mentioned competitor: television.

Singin’ in the Rain’s intertextual relationship to Babes in Arms (1939), the first musical produced by Freed, is particularly noteworthy. Babes is the prototypical ‘let’s put on a show in the barn’ movie. Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland play children of vaudeville performers whose livelihood disappeared when sound film killed vaudeville. In Babes the vaudevillians’ children put on a musical show to forestall their parents’ insolvency.

In Singin’, three characters hatch a plan to put on a musical movie and save a studio. The film dramatises the transition from vaudeville to the movies twice: in the opening sequence, when Don Lockwood moves from vaudevillian to stuntman to star, and again in the ‘Broadway Ballet’ sequence, which dramatises the ascent of a Lockwood-like character from no-name to Broadway star. Although this number glorifies The Great White Way, everything about it reinforces its cinematic qualities. The number demonstrates that the movies can encompass all other performing arts – song, music, dance – and offer them all up in a glossy package.

As a film, Singin’ is structured by musical spectacle, nostalgia and creative anachronism. Musical spectacle dominates the diegesis from the film’s opening moments to its closing. The credits feature a very wet performance of the film’s title song by the film’s three stars: Kelly, Donald O’Connor and Debbie Reynolds. The film’s closing moments feature a duet of Kelly and Reynolds singing ‘You are my Lucky Star’, a number finished by an invisible choir as Kelly/Don Lockwood and Reynolds/ Kathy Selden are transformed into billboard images advertising a film called Singin’ in the Rain. While this film qualifies as a backstage (or backlot) musical, and the plot motivates the performance of some musical numbers as entertainment or as components of a film within the film, other numbers, which express character moods, exist mostly as spectacle.

After the opening credits, the film locates us firmly in a nostalgia-inflected past. A billboard at the centre of the frame advertises the premiere of ‘The Biggest Picture of 1927’ at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. We settle in for the pleasures of a nostalgia film: we’ll appreciate the retro costumes and antique cars, and smirk at the characters’ inability to foresee a future that is already past. Viewers with any knowledge of film history will immediately note the significance of 1927, the year The Jazz Singer was released, which along with other films signalled the beginning of the end of the silent film era. When studio chief R. F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell) shows a talking picture at the post-premiere party, his guests pronounce it: ‘a toy’, ‘a scream’ and ‘vulgar’. A director intones, ‘It’ll never amount to a thing’. Cosmo Brown (Donald O’Connor) appears to be the only one with any foresight when he says, ‘That’s what they said about the horseless carriage’.

In the next scene, on the front lot at fictional studio Monumental Pictures, Cosmo reads a headline from Variety about The Jazz Singer’s smashing success in its first week. An extra looks up from his coffee to opine that it will be flop in the second. This kind of dramatic irony is frequently used by Hollywood to offer viewers a position of superior knowledge: in films made about the 1920s, characters fail to anticipate the stock market crash. In films set in 1941, characters don’t know Pearl Harbor is about to be attacked. In fact, experiments with sychronised sound go back virtually as far as experiments with film technology. Sound shorts were far from unknown before the release of The Jazz Singer. However, Warner Brothers was willing to bet the studio on a film starring Al Jolson, the most popular performing celebrity of the day, and were able to convince enough theatre owners to rewire their houses for sound. A successful earlier short featuring Jolson convinced the Warners to build their gamble around him. Nonetheless, the transition to sound film did not happen overnight. It took three years for sound film to fully replace silents as the dominant product of the Hollywood system.

Some of the pleasures of Singin’ come from the film’s willingness to both grant us positions of superior knowledge and give us backlot passes. We see silent film production, and then see the new technologies of sound film on display. We are granted the illusion that we are seeing how movies are really made. Just as we are privy to the artifice through which movies are created, we are privy to the artifice through which stars are created. As Kelly/Lockwood narrates the publicity department version of his career, we see images of the ‘real’ history: the education of a third-rate vaudevillian who started his movie career as an on-set musician and got a break as a stuntman. Of course, the ‘real’ story is as staged as anything else in the movie. Since we know we are watching a fictional film, we are in on the joke. The interplay between artifice and ‘reality’ continues throughout the film, from the invented romance between Don Lockwood and Lina Lamont through the dubbing which substitutes Kathy’s voice for Lina’s in the musical version of The Dancing Cavalier.

As with any film, artifice made visible to the audience masks other kinds of artifice. In Singin’ the most mind-boggling joke played on us concerns vocal dubbing. While Reynolds sings for herself in ‘All I do is Dream of You’ and ‘Good Mornin’’, other voices are dubbed over Reynolds’ when Reynolds/Kathy is shown dubbing in her voice for Lina Lamont’s. Betty Noyes actually sings the song recorded for The Dancing Cavalier, while Jean Hagen, the actress who plays Lina, speaks the dubbed dialogue attributed to Selden.

The film creates a similar illusion about film history, compressing years of history into weeks or minutes. Even as we swallow the fictionalised version of film history we are struck by a raft of anachronisms, many apparent even to casual moviegoers. The most significant anachronism is the use of dubbing technology to dub Kathy’s voice over Lina’s. Even if casual viewers were not aware that this technology was not available to the filmmakers of 1927, when synchronised sound was a technology in progress, they might notice the discrepancy between the ‘Beautiful Girls’ number and the later love scene from The Dueling Cavalier. When filming The Dueling Cavalier, the camera is placed inside a soundproof booth (an actual booth used in early sound pictures). The Monumental Pictures crew goes to great lengths to ensure that Lockwood and Lamont’s voices get recorded without extraneous noise such as a thrown cane or the beating of Lina’s heart.

Showing this rocky transition to sound, the film represents some real bumps on the road to sound film. However, when filming ‘Beautiful Girls’, not only is the camera freed from its booth, while sound is recorded through an overhead microphone, but R. F. Simpson manages to carry on a conversation with the director without interfering with the filming. The number concludes with an overhead camera shot of dancers forming kaleidoscopic patterns, a technique of choreographing and filming dance numbers pioneered by Busby Berkeley in the early 1930s, years after Singin’ takes place. In the earliest film musicals the camera films headon while simultaneously recording the sound. The sound quality was often poor and the camera was mostly immobile.

More than most (or perhaps any) musicals from the period, Singin’ in the Rain never feels wholly dated. The pace, the production values, and the quality of the performances are crucial. The interplay between artifice and greater artifice flatters viewers. The film can acknowledge the artifice of movie magic and still use movie magic to seduce its audience, which is fine with us – we would not be watching if we did not want to be seduced. Steven Cohan makes this point succinctly in his argument about and Singin’s status as ‘the first camp picture’. He writes: ‘Singin’ in the Rain stands out as “the ultimate MGM musical” because it can simultaneously be appreciated as one of the best films ever made and as feel-good escapism from a bygone era that still works its movie magic’ (2005: 202–3).

Produced when Hollywood was panicked about a new competitor – television – this glorification of movie magic, and of the all-encompassing capacity of the musical, reminds viewers to remember the silver screen. That tiny black and white TV set might help you keep up on old movies, but nothing can match the glorious feeling you get from the big screen, technicolor, star-studded, MGM musical.

Elliot Shapiro

Cast and Crew:

[Country: USA. Production Company: MetroGoldwyn-Mayer. Directors: Stanley Donen, Gene Kelly. Producer: Arthur Freed. Cinematographer: Harold Rosson. Editor: Adrienne Fazan. Art Directors: Randall Duell, Cedric Gibbons. Set Decoration: Jacques Mapes, Edwin B. Willis. Costume Design: Walter Plunkett. Cast: Gene Kelly (Don Lockwood), Donald O’Connor (Cosmo Brown), Debbie Reynolds (Kathy Selden), Jean Hagen (Lina Lamont).]

Further Reading

Rick Altman, The American Film Musical, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1989. Steven Cohan, Incongruous Entertainment: Camp, Cultural Value, and the MGM Musical, Durham, Duke University Press, 2005. Scoto Eyman, The Speed of Sound: Hollywood and the Talking Revolution, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1997. Jane Feuer, The Hollywood Musical, 2nd ed., Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1993.

Source Credits:

The Routledge Encyclopedia of Films, Edited by Sarah Barrow, Sabine Haenni and John White, first published in 2015.

Related Posts:

- Why do people make Experimental Films?

- Modern Times - Summary & Analysis

- My Antonia: Film Review

- Groucho Marx and the progression from vaudeville to movies, to radio and to television in…

- Gimme Shelter (Movie): Summary & Analysis

- How Netflix’ Bird Box turned into an online sensation:

Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Film Analysis — Singing in the Rain: A Timeless Cinematic Triumph

Singing in The Rain: a Timeless Cinematic Triumph

- Categories: Film Analysis Movie Review

About this sample

Words: 2072 |

11 min read

Published: Aug 31, 2023

Words: 2072 | Pages: 5 | 11 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the role of satire in singing in the rain, singing in the rain: musical masterpiece, timeless and enduring movie, works cited.

- Ebert, R. 'Singin' in the Rain.' RogerEbert.com, January 18, 2004.

- Basinger, J. 'The Movie Musical!' Alfred A. Knopf, 2019.

- Kelly, G., & Donen, S. 'Singin' in the Rain' [Film]. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952.

- Schwartz, L. 'Singing in the Dark: 500 Songs for Film and Television.' University of Michigan Press, 2010.

- Shwartz, L. 'Singin' in the Rain: Hollywood’s Sudden Transition from Silent Films to Sound.' The Berkshire Eagle, December 9, 2001.

- Ewing, J. 'Celebrities: Donald O'Connor.' Scotsman.com, September 28, 2003.

- Johnson, R. 'Films That Last: A List to Stand the Test of Time.' Los Angeles Times, December 19, 2019.

- Giannetti, L., & Goodykoontz, B. 'Understanding Movies.' Pearson, 2017.

- Hunter, S. 'Singing in the Rain.' The Washington Post, January 1, 1970.

- Renolds, D. 'Singin' in the Rain.' Debby Renolds' Official Website, debbiereynolds.com.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1612 words

2 pages / 843 words

1 pages / 1270 words

2 pages / 982 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Film Analysis

Crafton, D. (1999). The talkies: American cinema's transition to sound, 1926-1931. University of California Press.Koszarski, R. (2009). An evening's entertainment: The age of the silent feature picture, 1915-1928. University of [...]

Watching a good movie is one of my favorite pastimes. After a long day of school or work there is on other sensations such as curling up on the couch and watching a great movie. Epic stories throughout our history our best [...]

Silver Linings Playbook is a 2012 American romantic-comedy-drama film written and directed by David O.Russell. The film was based on Matthew Quick’s 2008 novel The Silver Linings Playbook. It stars Bradley Cooper and Jennifer [...]

Inside out is a film that revolves around Riley and takes us on an emotional journey she experiences throughout the entire film. There are three main psychological principles that are very evident to me in the reading as well as [...]

In China, the name Hua Mulan (???) has been connected with the term ‘heroine’ for hundreds of years. Hua Mulan has become a symbol of heroic behavior. Her character has inspired many Chinese women to defy traditional gender [...]

The belief that “men and women should have equal rights and opportunities is pure feminist. This movement is based on the desire to become a better version, is more as a fight for freedom and to belong somewhere. A [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

Singin’ in the Rain

Essay by brian eggert december 3, 2017.

Classic Hollywood productions rarely had two directors, and if they did, the result was a studio creation and not shaped by the vision of a single auteur. The exception is Singin’ in the Rain , the 1952 release from co-directors Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, which remains distinguished from the frivolous Classical Hollywood musicals of the era. Though it was developed as a standard production within the studio system, the film contains a rare harmony between its narrative and musical elements, demonstrating how they could be merged, and therein enhanced, through their integration on film. Decades after its debut, many film scholars and critics consider it the greatest of all Hollywood musicals, attributing its authorship to Kelly. But how exactly does Singin’ in the Rain differ from the typical musical, and why has it earned such an esteemed reputation? How did Kelly and Donen, overseeing hundreds of talented players and technicians, somehow make a film that seems to come from a distinct creative voice, even working within the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer musical factory? What was Kelly and Donen’s working relationship like, and how was a singular vision achieved? These answers can only be found by exploring the story behind the film; the careers of Kelly and Donen, and how they worked together; their implementation of song and dance into the narrative; and specific sequences in the film. This historical and critical analysis will show the film’s production and directorial collaboration to have been guided predominantly by Kelly’s vision to at once elevate and popularize the art of dance in cinema, yet render it in a joyous and accessible way.

To understand why Singin’ in the Rain stands apart, the Classic Hollywood musical itself requires characterization. In musicals of the period, dreams came true and love conquered all, making them the most entertaining and escapist features available to audiences. But in terms of story, they were the most lighthearted genre. They showcased popular melodies, a variety of dancing styles, and romantic comedy more than narrative or character. Traditional Hollywood musicals, especially efforts from the 1920s and 1930s, used a loose framework and treated their songs like interludes within the story. Although Broadway provided the source material for many musicals of the era, most musicals contained thin plotting and characters within a romantic comedy structure, the films serving an indulgence of music and dance first, the story second. Their considerable budgetary requirements meant most musicals were “A” pictures, and the most inventively shot, with the latest technical advances in sound and camera supporting their productions. Among the major Hollywood studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was the premier musical factory in the 1940s, especially after Vincente Minnelli’s 1944 breakthrough Meet Me in St. Louis , an elaborate spectacle filmed in three-strip Technicolor—most of the studio’s musicals were shot in the expensive three-strip process after its success. MGM also housed the greatest group of musical talents in Hollywood history (including Judy Garland, Fred Astaire, Frank Sinatra, and Minnelli), releasing many of the era’s most iconic musicals, such as The Wizard of Oz in 1939 and Charles Walters’ 1948 Easter Parade .

More even than Kelly or Donen, Singin’ in the Rain would not have been possible without Arthur Freed. The Freed-Brown team wrote the titular song for the Hollywood Music Box Revue of 1927, an elaborate stage show of comedians, dancers, showgirls, and singers. Around this time, Warner Brothers’ The Jazz Singer in 1927, a largely silent picture with some moments of synchronized singing and dialogue recorded on disc, became a massive hit. Following its success, other studios began to integrate musical soundtracks and, in time, dialogue into their productions. Freed and Brown had been working as pianists to set the mood on silent film sets. When MGM production head Irving Thalberg heard about the talent of the Freed-Brown team, he hired them as musicians and songwriters, enlisting them to produce a number of “Broadway Melody” pictures for MGM that showcased popular stage hits on the screen.

As Freed and Brown’s success grew with their catalog of popular tunes, Freed established himself as a Hollywood producer. Their song “Singin’ in the Rain” was first used on film in The Hollywood Revue of 1929 , a cinematic version of the earlier stage show. MGM would continue to use the song in several pictures over the years, with covers sung by Cliff Edwards, Jimmy Durante, and Judy Garland. Freed soon established his own production division at MGM, called the Freed Unit, to develop and oversee musicals based on Broadway hits or the Freed-Brown catalog. The Freed Unit was responsible for most major MGM musicals of Hollywood’s Golden Age, earning the studio vast profits from postwar audiences desperate to escape into a musical, especially one starring contract players like Kelly or Fred Astaire. Singin’ in the Rain was just one of many Freed productions. And by the time of its release, the song’s popularity was such that, upon seeing the film’s title, audiences would recognize its apostrophic slang and easily recall its melody.

Unlike Kelly, Donen’s interests in cinema preceded his involvement in dance and the stage. Born in 1924, Donen was raised in Columbia, South Carolina, in a town that did not welcome people of his Jewish heritage; and so, as a boy, he escaped through radio plays, music, and the cinema, particularly the films of Fred Astaire. He received an 8mm camera from his father as a gift, and he experimented with making home movies, implanting his desire to become a filmmaker early in life. Still, following his interest in Astaire and dancing, Donen studied dance locally. His mother, who had taken him to New York to see several stage shows, soon encouraged her son to move and pursue Broadway, which he did, even though his true calling was filmmaking. Donen met Kelly during the hugely popular 1940 stage production of Pal Joey on Broadway, and Kelly eventually asked Donen, then just in his mid-teens, to join him in Hollywood as his assistant. Donen worked almost exclusively on MGM musicals for more than a decade. As the years passed, Donen became progressively more interested in the technical aspects of filmmaking, and he explored other genres in the latter part of his career: the blithe Hitchcockian thriller in Charade (1963) and Arabesque (1966); the romantic drama with Indiscreet (1958) and Two for the Road (1967); and even, much later, the Lionel Richie music video “Dancing on the Ceiling” (1986).

As early as 1949, Freed began developing a project intended to use several famous Freed-Brown songs, including “Singin’ in the Rain.” Freed proposed a screen story based on the silent film Excess Baggage (1928), about a romance between a dancer and an acrobat. The treatments drawing from Excess Baggage proved uninspired, and so Freed resolved to leave the screen story to more experienced writers. In May of 1950, Freed hired Broadway-turned-Hollywood writers Betty Comden and Adolph Green to write a screenplay, which he intended Donen to direct. After considering other ideas such as a Western story or a remake of a different preexisting film, Comden and Green found themselves inspired by the career of silent film actor John Gilbert, whose celebrity was ruined when his nasally, underwhelming voice in talkies did not match his debonair good looks. Comden and Green conceived a story to match the optimism of the central song, settling on the idea of a silent film star who at first struggles with the advent of sound in motion pictures, but rather than give up, he becomes a star of talkies.

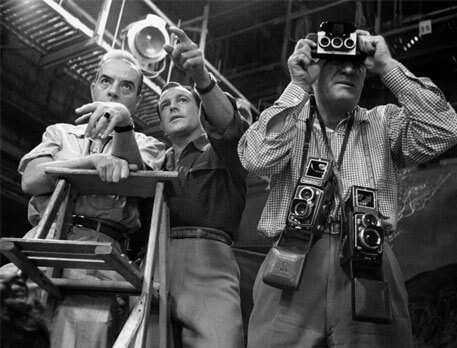

Kelly and Donen would once again work together as co-directors, just as they had during On the Town . The directorial partnership between them placed Kelly in front of the camera, choreographing and concentrating on performance, while Donen remained behind the camera. Together, they prepared for each sequence, reviewed the dailies, and supervised the editing process, with Kelly’s aesthetic choices guiding many of the decisions. Filming began in June 1951, and by that time the sound recording of the songs was already complete, leaving Kelly and Donen to synchronize the dancing. In his years as a Hollywood performer observing his directors, Kelly learned that movement onscreen depends on the movement of the camera, and viewers of a stage performance saw something different than a film’s audience. On the stage, dancers appeared smaller and had to occupy the entire stage along with their costars, so large movements became more important than acting; on film, the camera could move along with the dancer, and the viewer could better appreciate specific movements onscreen, in particular, the actor’s ability (or inability) to remain in character during the dance. Film allowed Kelly to explore his desire to improve the relationship between the dancing, the characters, and the audience. Donen understood his co-director’s ambitions and became immersed in the visual side of capturing Kelly’s performance on camera, though his choices were often dictated by Kelly.

The dynamics of the Kelly-Donen collaboration remain somewhat mysterious, as the two never discussed their working relationship in detail; although, their remarks about one another provide some insight. Kelly described Donen with words like “assistant” and “aide,” while saying he could never direct alone because “You need somebody that you can trust and that can help you.” Kelly’s description of their partnership seems more appreciative of the collaboration than Donen’s memories. Donen remembered that he lost many of their arguments and disagreements: “Substitute the word ‘fight’ for codirect, then you have it,” he later remarked. Donen also criticized his co-director’s more artful choices in the film, claiming the ballet sequences were “pretentious” and “too long.” From their discussions, Kelly seems to be the visionary and Donen was the “third eye behind the camera,” implementing technical solutions to achieve what Kelly wanted to see onscreen. Whatever their off-screen quarrels, their collaboration, along with the efforts of the entire Freed Unit, produced the idea of “cine-dance,” wherein dancing and filmmaking achieve a rare balance. As Kelly admitted, Donen’s technical expertise was invaluable in capturing dance on film and bringing Kelly’s vision to life.

Of course, Singin’ in the Rain is not only about dance and its aesthetic integration with narrative; the story also presents a film-about-film—specifically, about an era that ostensibly ended 24 years earlier. Kelly, having a knowledge of silent film as equally enthusiastic as Comden and Green, worked closely with the writing team and contributed to the film’s references throughout. Kelly later admitted, “Almost everything in Singin’ in the Rain springs from the truth. It’s a conglomeration of bits of movie lore.” For instance, Roscoe Dexter (Douglas Fowley)—the director of Singin’ in the Rain ’s film-within-the-film—was based on Busby Berkeley; Freed inspired the film’s studio head R.F. Simpson (Millard Mitchell); and Donald O’Connor’s on-set pianist character, Cosmo Brown, came from Freed’s days as a silent film piano accompanist. To ensure the scenes of 1920s-era filmmaking looked accurate, the production required research, more than any other musical by MGM at the time. Kelly insisted on authenticity and requested that production designer Randall Duell and set director Jacque Mapes study archival behind-the-scenes footage around MGM to recreate the look of a 1920s studio lot. The technical crew took the need for authenticity one step further and used actual equipment still lingering around the studio from the silent era as props. From the film’s props to the script, and the implementation of cine-dance, Kelly shaped the production of Singin’ in the Rain to his vision. Production wrapped in November 1951, and preview screenings were already arranged for the following month.

The story has been called a “Fairy-Tale Musical” and compared to Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid , but set on the fictional Hollywood soundstage of Monumental Pictures upon the advent of sound. Early on, one character reads a headline on the cover of Variety , calling The Jazz Singer “an all-time hit in the first week,” but another character chimes in, “all-time flop in the second.” Industry fads were common at this time, appearing and disappearing; the film industry itself was considered a fad, bound to disappear. Singin’ in the Rain follows two silent film stars, Don Lockwood (Kelly) and Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen), as they adjust to talkies, which threaten to render their careers obsolete. Don has the looks of Douglas Fairbanks and trained in singing and dancing as a vaudeville star. Lina has not been so fortunate; she has star appeal, but neither the voice nor diction—nor raw talent or smarts—to make it in talkies. (When the studio voices its concerns, Lina replies, “What do they think I am, dumb or something? Why, I make more money than Calvin Coolidge put together!”) As the studio experiments with turning their latest Lockwood-Lamont production, a French costume romance called The Duelling Cavalier , into a talkie, they realize Lina’s harsh, jarring voice will surely irritate audiences. What is more, their technicians are not prepared for audio. A wireless microphone placed on Lina picks up her heartbeat, and her grating voice comes through intermittently when they place the mic in a nearby plant. The adjustment is tiresome, as Lina shouts, “I can’t make love to a bush!”

Although Singin’ in the Rain would later be called the finest musical ever made, no such claims were made upon its release in late March of 1952. The film cost more than $2.5 million to make and, during its initial release, it earned over $7.6 million in box-office receipts. Many critics of the era, such as Bosley Crowther of the New York Times and Irene Thirer of the New York Post , praised the film’s cheerfulness but felt its audience was limited due to its placement in the 1920s; other critics concentrated on the entertainment value of the film, such as Arthur Knight, who called the film “everything you could ask of a musical.” The majority of reviews highlighted the film’s musical qualities, suggesting it was a particularly great studio effort. But few critics discussed its commentary on the film industry, took substantive note of the film’s cine-dance, or declared it one of the best of its kind. Surprisingly, the film was nominated for just two Academy Awards at the 1953 ceremony, including Best Supporting Actress for Hagen and Best Music. Donen, Comden, and Green told the press they felt “ignored” by the Academy. Instead, at the time of its release in theaters, Academy voters at the March 1952 Academy Awards ceremony remembered Kelly’s film from the previous year, An American in Paris , and garnered it with six Oscars, including Best Picture. Also in 1952, Kelly was awarded an honorary statue for his “versatility as an actor, singer, director and dancer, and specifically for his brilliant achievements in the art of choreography on film.”

Even though Singin’ in the Rain performed well at the box office and received positive reviews, for Kelly, its release was bittersweet. Shortly after production wrapped in November 1951, the actor left Hollywood and the country for a year and a half, claiming he wanted to take advantage of a new tax law that exempted U.S. citizens from paying income tax if they lived abroad for eighteen months. However, since arriving in Hollywood, Kelly had become politically active with the left, and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had been carrying out anti-leftist probes of Hollywood, which led to the blacklists and a number of celebrity informants. Kelly, his wife Betsy Blair, Comden and Green, along with others from the production of Singin’ in the Rain had socialist interests, or at least sympathies. Kelly resolved to avoid the HUAC hearings altogether and lived in France for six months, followed by a year in London. When he returned, he did so only because he had convinced Roy Brewer, a right-wing union boss in Hollywood, that he was not a communist. After making two underwhelming films overseas, he resumed his streak of winning musicals with Brigadoon (1954). But Kelly’s later work would not contain the same narrative integrity between the story and dance sequences as Singin’ in the Rain .

Amid the fifteen songs featured in the film, most of them contain dance sequences, each mixing with the narrative through cine-dance, as Kelly envisioned, and none more so than the “Singin’ in the Rain” number. Representative of the film’s integration of lyrics, music, and dance as having a place in the story, the sequence is deceptively simple. But upon examination, it proves quite complex, as it appropriates, integrates, and literalizes a well-known song from previous decades into the narrative. At first look, Kelly’s dance in the rain appears like nothing more than a soundstage piece, a standard “putting on a show” number that exists primarily for its entertainment value. But the sequence must come at the precise moment in the story in which the happiness of Kelly’s character overrides all else, and singing in the rain is an appropriate action not forced into the narrative. Don, Kathy, and Cosmo have just thought to make The Duelling Cavalier into a musical, and after walking Kathy home in the rain, Don realizes his career and romantic troubles seem to be over. It resembles a sequence in Cover Girl , in which Kelly, Rita Hayworth, and Phil Silvers dance out of a restaurant and into the street, singing, dancing on the sidewalk, and annoying a policeman in the process. Similarly, Kelly leaves Kathy and begins to sing and dance in the rain. He feels the downpour on his face, catches it in his mouth, and squirts it back out; he twirls his open umbrella; he dances up and down stoops and porches; he swings from light posts; and, finally, he splashes about like a child in a puddle, much to the suspicion of a disapproving policeman. The scene would have seemed nonsensical anywhere else in the story, but instead, it feels like an expression of joy at the only appropriate moment in the film.

Although Kelly wanted to unify narrative with song and dance in Singin’ in the Rain , he also wanted the film to be a “Broadway Melody” of sorts, presenting a showcase for a wide range of dancing and musical styles, including the French Cancan, burlesque performance, vaudeville, Ziegfeld Follies, and ballroom dancing. The Freed-Brown duo had written most of the songs back in the 1920s and 1930s, but they were adapted into 1950s styles, in part to sound pleasant to contemporary ears, in part to facilitate particular dances. For example, Kelly dug into the Freed-Brown catalogue of songs to find “Make ‘em Laugh,” knowing O’Connor’s background in vaudeville. Starting with the song, Kelly and O’Connor developed the sequence where Cosmo delivers a small compilation of physical gags and slapstick in unison with song and dance. The scene, shot mostly in long takes, shows O’Connor dancing with a dummy, bouncing his head on a plank of wood, leaping through drywall, and performing backflips. Only one song was written for the film, the “Moses Supposes” number that allows Kelly and O’Connor to engage in wordsmithing and dance in a hilariously irreverent, absurdist performance that also provides a commentary on Hollywood’s diction coaches.

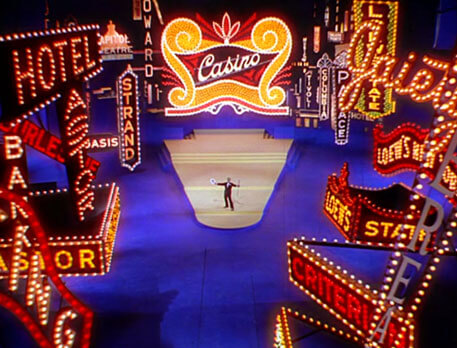

Just as Kelly wanted Singin’ in the Rain to be a “Broadway Melody” showcase of dancing styles, Kelly insisted that his character be a reflection of himself, and so Don has the same ambitions for The Dancing Cavalier . This meant the dance numbers in Singin’ in the Rain exist in the film’s reality, whereas many Classic Hollywood musicals used dream sequences to explain away spectacles such as the “Singin’ in the Rain” sequence. Even the film’s most expressive dance, the lengthy Broadway Ballet, exists in a practical context. Running more than eight minutes long, the Broadway Ballet sequence transitions through several types of dance, ballet most prominently, in a series of stagey nightclub and casino sets. Ballet had become popular on Broadway following the stage hit On Your Toes in 1936, and most stage musicals in the next decade or more would feature at least one ballet number, many of them based on surreal dream sequences. Surrealism was prevalent in 1940s Hollywood with the popularization of Freudian psychoanalytic dream analysis, demonstrated in the Salvador Dali-designed dream sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Spellbound (1945) or the twisted ballet in the Astaire romance Yolanda and the Thief (1945). And while Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s films The Red Shoes (1949) and The Tales of Hoffman (1951) had already demonstrated how artful—and commercially successful—the amalgamation of surreal ballet and cinema could be, Kelly’s painterly ballet sequence in An American in Paris proved much the same. Without these earlier examples of ballet in film, it is doubtful Kelly would have been allowed to indulge in the film’s extended sequence.

Singin’ in the Rain ’s story fades into the Broadway Ballet sequence not as a dream sequence or hallucinatory aside, but as the visualization of a dance number for The Dancing Cavalier that Don proposes to Simpson. Don explains to Simpson that the sequence begins as the hero of The Dancing Cavalier , a Broadway performer, reads backstage until being struck in the head with a sandbag. The character, played by Don, wakes during the French Revolution and dances his way through several historical modes, leading to his presence in a modern club for gangsters, where he pursues a mobster’s beautiful inamorata, played by Charisse. They eventually meet in a wistful, dreamlike scarf ballet, moving among the coils of a fifty-foot piece of Chinese silk. The dance is not surreal within the context of the narrative; rather, it is a visualized description of the dream-within-the-film-within-the-film, and therefore a practical matter. Its placement enhances the narrative rather than disrupt it or provide an interlude. More than any other dance number in the film, the Broadway Ballet sequence seems to epitomize Kelly as the dancer-performer and further legitimize ballet as a commercially appealing artform, as he has so carefully integrated it with the film’s narrative through cine-dance.

The dreamy, if grounded dance sequences in Singin’ in the Rain underscore its prevalent theme that considers the difference between Hollywood artifice and reality. When integrating sound into The Duelling Cavalier , Dexter hilariously struggles to show Lina how to deliver her lines into the microphones. After tense reshoots to include sound, preview crowds boo the first cut, as Don’s larger-than-life acting style, Lina’s chirping voice, and the production’s booming use of sound altogether change the function of their silent film script. The dialogue written for their silent film’s intertitles sounds awkward when spoken, so it must be rewritten. Moreover, their voice performances must be calibrated for film to avoid sounding mannerist. To solve the problem, they rely on looping, the practice of dubbing over dialogue in post-production. As looping puts new sounds to the original images, Singin’ in the Rain demonstrates the ways in which films represent illusions, and that what the viewer sees is not always real.

After making their audience aware of the artifice at work in a Hollywood production, Kelly and Donen ensure that any cognizance of Hollywood’s cinematic apparatus does not diminish their own film’s effectiveness. By hiding their film’s artifice through cine-dance, the filmmakers can engage their audience on an emotional level and still provide a commentary on Hollywood filmmaking. Their approach is best reflected by comparing the “You Were Meant For Me” sequence to its counterpart, the scarf dance that occurs later in the film at the end of the Broadway Ballet. Consider how, earlier in the film, Don exposes Kathy to the magic of a film’s soundstage as he sings “You Were Meant For Me.” On an empty Monumental Pictures soundstage, Don switches on romantic lighting, turns on a fan for a slight breeze, stands before a matte painting of a sunset, and sings to Kathy, openly acknowledging the artificiality of the ambiance around them. The “You Were Meant For Me” sequence is mirrored by similar soundstage atmospherics to create a romantic mood in the scarf dance between Kelly and Charisse, although the visible apparatuses have been hidden. Note how the spotlights in the “You Were Meant For Me” sequence remain stationary, suggesting the unattended production equipment, whereas, during the latter scarf dance, the lights follow Kelly and Charisse about their dreamstage. And yet, the audience is no less taken by either performance, even though the film, earlier, made the viewer aware of the cinematic apparatus creating this mood.

Indeed, the disparity between sound and image, and their correct attribution to their respective performers, presents a thematic anxiety in both the narrative and the filmmaking in Singin’ in the Rain . Lina’s appearance in The Dancing Cavalier and her false voice credit present a disparity between the visual and aural, and Don yearns to secure Kathy her due credit. Only after sound and image perform in harmony again, during the climactic scene where Kathy is revealed to the premiere crowd to be Lina’s voice, does order feel restored. Of course, Kelly insisted on long takes and minimal reliance on montage to assemble the film’s dance numbers, ensuring there would be no question of unity between sound and image in relation to his dancing. Kelly’s ambitions for the film seem to align with Don’s for The Dancing Cavalier , as both talents hope to create a film that, due to their technical seamlessness, the audience will watch on an emotional level and forget about the filmmaking. Likewise, Singin’ in the Rain ’s illusion is so complete that the viewer never questions or suspects the authenticity behind Kelly, Reynolds, or O’Connor’s voice talents in conjunction with their image (although, like most musicals of the time, the audio track for the songs was recorded before shooting and added in post-production).

Singin’ in the Rain establishes a theme that juxtaposes the real and unreal, reality and cinematic fantasy, and the illusory unity of sound and image through the film’s dominant metaphor: unwavering happiness and optimism, regardless of the rain. The film’s representation of Hollywood’s illusions offers a self-aware commentary filled with humor and clever wit about the film industry, its technical practices, and the uglier side of celebrity. While the imitation and parodying of the sound era comes from Comden and Green, who were film enthusiasts and had often written comic sketches parodying the film industry, they, like Kelly, had a genuine affection and passion for cinema. But even as the film exposes the artifice of cinema and how its magic depends on the illusions created by technicians, it embraces the end product, celebrating films and filmmakers regardless of their manipulations. That audiences can watch, laugh, fall in love, and escape for two hours without being distracted by what they know (or learned from the film) about the filmmaking process, represents a rare accomplishment. But the dramatic and technical themes in Singin’ in the Rain echo Kelly’s insistence on the narrative’s unity with song and dance, and his desire to improve how filmmaking realizes that unity.

Long before his arrival in Hollywood, Kelly aspired to blend dance with narrative and, with the technical assistance of Donen to realize his vision, he finally achieved his goal with Singin’ in the Rain . But the collaboration and shared credit between co-directors, along with its status as a product of the Classic Hollywood era, have long challenged film scholars to identify whether Singin’ in the Rain has an author, despite its legacy. However, the film remains too distinct from other musicals to be described as a typical MGM programmer. Singin’ in the Rain represents a unique synthesis of narrative and dance based on Kelly’s desire to unify them into an original storytelling expression. As we have seen, the film adopts the formal precision of a Golden Age musical, but Donen’s technical efforts were shaped and tested by Kelly’s ambition to integrate dance and narrative into cine-dance, thus extending the production beyond the requirements of an average MGM release. Indeed, Kelly’s influence over the production informs nearly every element of the film, the themes, narrative structure, and Donen’s technical choices above all. Using Classic Hollywood’s collaborative studio system to meet his needs as a dancer, storyteller, and filmmaker, Kelly succeeded in achieving his singular vision.

Bibliography:

Behlmer, Rudy. America’s Favorite Movies: Behind the Scenes . London: Samuel French, 1990.

Brideson, Cynthia and Sara Brideson. He’s Got Rhythm: The Life and Career of Gene Kelly . Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2017.

Cohan, Steven. “Case Study: Interpreting Singinʼ in the Rain .” Reinventing Film Studies . Ed. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams. New York: Oxford UP, 2001, pp. 53–75.

Ewing, Marilyn M. “Dance! Structure, Corruption, and Syphilis in Singin’ in the Rain .” Journal of Popular Film & Television , vol. 34, no. 1, Spring2006, pp. 12-23.

Hess, Earl J. and Pratibha A. Dabholkar. Singin’ in the Rain: The Making of an American Masterpiece . Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Juddery, Mark. “Breaking the Sound Barrier.” History Today , vol. 60, no. 3, Mar. 2010, pp. 37-43.

Silverman, Stephen M. Dancing on the Ceiling: Stanley Donen and His Movies . New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Wollen, Peter. Singin’ in the Rain . BFI Film Classics. London: Palgrave MacMillian, 2012.

Yudkoff, Alvin. Gene Kelly: A Life of Dance and Dreams . New York: Back Stage/Watson-Guptill, 1999.

Related Titles

- In Theaters

Recent Reviews

- Good One 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Strange Darling 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Blink Twice 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Alien: Romulus 2.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Skincare 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Sing Sing 3.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Borderlands 1.5 Stars ☆ ☆

- Dìdi 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Cuckoo 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- The Instigators 2 Stars ☆ ☆

- Trap 2.5 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Patreon Exclusive: House of Pleasures 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Patreon Exclusive: La chimera 4 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

- Deadpool & Wolverine 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

- Starve Acre 3 Stars ☆ ☆ ☆

Recent Articles

- Interview: Jeff Vande Zande, Author of The Dance of Rotten Sticks

- The Definitives: Nocturama

- Guest Appearance: KARE 11 - Hidden Gems of Summer

- The Labyrinth of Memory in Chris Marker’s La Jetée

- Reader's Choice: Thanksgiving

- Reader's Choice: Perfect Days

- The Definitives: Kagemusha

- The Scrappy Independents of Mumblegore

- Reader's Choice: Creep 2

- Reader's Choice: The Innkeepers

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, chaz's journal, great movies, contributors, singin' in the rain.

Now streaming on:

There is no movie musical more fun than "Singin' in the Rain,” and few that remain as fresh over the years. Its originality is all the more startling if you reflect that only one of its songs was written new for the film, that the producers plundered MGM's storage vaults for sets and props, and that the movie was originally ranked below " An American in Paris ,” which won a best picture Oscar. The verdict of the years knows better than Oscar: "Singin' in the Rain” is a transcendent experience, and no one who loves movies can afford to miss it.

The film is above all lighthearted and happy. The three stars-- Gene Kelly , Donald O'Connor and 19-year-old Debbie Reynolds--must have rehearsed endlessly for their dance numbers, which involve alarming acrobatics, but in performance they're giddy with joy. Kelly's soaking-wet "Singin' in the Rain” dance number is "the single most memorable dance number on film,” Peter Wollen wrote in a British Film Institute monograph. I'd call it a tie with Donald O'Connor's breathtaking "Make 'em Laugh” number, in which he manhandles himself like a cartoon character.

Kelly and O'Connor were established stars when the film was made in 1952. Debbie Reynolds was a newcomer with five previous smaller roles, and this was her big break. She has to keep up with two veteran hoofers, and does; note the determination on her pert little face as she takes giant strides when they all march toward a couch in the "Good Morning” number.

"Singin' in the Rain” pulses with life; in a movie about making movies, you can sense the joy they had making this one. It was co-directed by Stanley Donen , then only 28, and Kelly, who supervised the choreography. Donen got an honorary Oscar in 1998, and stole the show by singing "Cheek to Cheek” while dancing with his statuette. He started in movies at 17, in 1941, as an assistant to Kelly, and they collaborated on "On the Town” (1949) when he was only 25. His other credits include "Funny Face” and "Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.”

One of this movie's pleasures is that it's really about something. Of course it's about romance, as most musicals are, but it's also about the film industry in a period of dangerous transition. The movie simplifies the changeover from silents to talkies, but doesn't falsify it. Yes, cameras were housed in soundproof booths, and microphones were hidden almost in plain view. And, yes, preview audiences did laugh when they first heard the voices of some famous stars; Garbo Talks!” the ads promised, but her co-star, John Gilbert, would have been better off keeping his mouth shut. The movie opens and closes at sneak previews, has sequences on sound stages and in dubbing studios, and kids the way the studios manufactured romances between their stars.

When producer Arthur Freed and writers Betty Comdon and Adolph Green were assigned to the project at MGM, their instructions were to recycle a group of songs the studio already owned, most of them written by Freed himself, with Nacio Herb Brown. Comdon and Green noted that the songs came from the period when silent films were giving way to sound, and they decided to make a musical about the birth of the talkies. That led to the character of Lina Lamont ( Jean Hagen ), the blond bombshell with the voice like fingernails on a blackboard.

Hagen in fact had a perfectly acceptable voice, which everyone in Hollywood knew; maybe that helped her win an Oscar nomination for best supporting actress. ("Singin' “ was also nominated for its score, but won neither Oscar--a slow start for a film that placed 10th on the American Film Institute list of 100 great films, and was voted the fourth greatest film of all time in the Sight & Sound poll.) She plays a caricatured dumb blond, who believes she's in love with her leading man, Don Lockwood (Kelly), because she read it in a fan magazine. She gets some of the funniest lines ("What do they think I am? Dumb or something? Why, I make more money than Calvin Coolidge put together!”).

Kelly and O'Connor had dancing styles that were more robust and acrobatic than the grandmaster, Fred Astaire . O'Connor's "Make 'em Laugh” number remains one of the most amazing dance sequences ever filmed -- a lot of it in longer takes. He wrestles with a dummy, runs up walls and does backflips, tosses his body around like a rag doll, turns cartwheels on the floor, runs into a brick wall and a lumber plank, and crashes through a backdrop.

Kelly was the mastermind behind the final form of the "Singin' in the Rain” number, according to Wollen's study. The original screenplay placed it later in the film and assigned it to all three stars (who can be seen singing it together under the opening titles). Kelly snagged it for a solo and moved it up to the point right after he and young Kathy Selden (Reynolds) realize they're falling in love. That explains the dance: He doesn't mind getting wet, because he's besotted with romance. Kelly liked to design dances that grew out of the props and locations at hand. He dances with the umbrella, swings from a lamppost, has one foot on the curb and the other in the gutter, and in the scene's high point, simply jumps up and down in a rain puddle.

Other dance numbers also use real props. Kelly and O'Connor, taking elocution lessons from a voice teacher, do "Moses Supposes” while balancing on tabletops and chairs (it was the only song written specifically for the movie). "Good Morning” uses the kitchen and living areas of Lockwood's house (ironically, a set built for a John Gilbert movie). Early in the film, Kelly climbs a trolley and leaps into Kathy's convertible. Outtakes of the leap show Kelly missing the car on one attempt and landing in the street.

The story line is suspended at the two-thirds mark for the movie's set piece, "Broadway Ballet,” an elaborate fantasy dance number starring Kelly and Cyd Charisse . It's explained as a number Kelly is pitching to the studio, about a gawky kid who arrives on Broadway with a big dream ("Gotta Dance!”), and clashes with a gangster's leggy girlfriend. MGM musicals liked to stop the show for big production numbers, but it's possible to enjoy "Broadway Ballet” and still wonder if it's really needed; it stops the headlong energy dead in its tracks for something more formal and considered.

The climax ingeniously uses strategies that the movie has already planted, to shoot down the dim Lina and celebrate fresh-faced Kathy. After a preview audience cheers Lina's new film (her voice dubbed by Kathy), she's trapped into singing onstage. Kathy reluctantly agrees to sing into a backstage mike while Lina mouths the words, and then her two friends join the studio boss in raising the curtain so the audience sees the trick. Kathy flees down the aisle--but then, in one of the great romantic moments in the movies, she's held in foreground closeup while Lockwood, onstage, cries out, "Ladies and gentlemen, stop that girl! That girl running up the aisle! That's the girl whose voice you heard and loved tonight! She's the real star of the picture--Kathy Selden!” It's corny, but it's perfect.

The magic of "Singin' in the Rain” lives on, but the Hollywood musical didn't learn from its example. Instead of original, made-for-the-movies musicals like this one (and "An American in Paris,” and " The Band Wagon ”), Hollywood started recycling pre-sold Broadway hits. That didn't work, because Broadway was aiming for an older audience (many of its hits were showcases for ageless female legends). Most of the good modern musicals have drawn directly from new music, as " A Hard Day's Night ,” " Saturday Night Fever ” and "Pink Floyd the Wall” did. Meanwhile, "Singin' in the Rain” remains one of the few movies to live up to its advertising. "What a glorious feeling!” the posters said. It was the simple truth.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

My Spy The Eternal City

Christy lemire.

Hundreds of Beavers

Matt zoller seitz.

Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam

Brian tallerico.

Strange Darling

Film Credits

Singin' in the Rain (1952)

103 minutes

Gene Kelly as Don Lockwood

Donald O'Connor as Cosmo Brown

Debbie Reynolds as Kathy Seldon

Jean Hagen as Lina Lamont

Millard Mitchell as R.F. Simpson

Rita Moreno as Zelda Zanders

Douglas Fowley as Roscoe Dexter

Cyd Charisse as Dancer

Directed by

- Stanley Donen

Produced by

- Arthur Freed

Screenplay by

- Adolph Green

- Betty Comden

Photographed by

- Harold Rosson

- Adrienne Fazan

Latest blog posts

13 Films Illuminate Locarno Film Festival's Columbia Pictures Retrospective

Apple TV+'s Pachinko Expands Its Narrative Palate For An Emotional Season Two

Tina Mabry and Edward Kelsey Moore on the Joy and Uplift of The Supremes at Earl's All-You-Can-Eat

The Adams Family Gets Goopy in Hell Hole

Singin' in the Rain Themes

Lies and deceit, respect and reputation, language and communication, tired of ads, cite this source, logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

Singing in the Rain

Fiction | Picture Book | Early Reader Picture Book | Published in 2013

Plot Summary

Continue your reading experience

Subscribe to access our Study Guide library, which offers chapter-by-chapter summaries and comprehensive analysis on 8,000+ literary works ranging from novels to nonfiction to poetry

The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The mise-en-scene, cinematography.

The scene from the movie Singin’ in the Rain , where Don Lockwood confesses Katie’s feelings with a song, is iconic. The importance of this scene is conveyed, among other things, with the help of formal film elements, such as the construction of the mise-en-scene, cinematography and sound.

The set design represents a misty space, among which two lovers are the central figures, and emphasizes their importance. Among the props, a staircase that seems to lead to the sky requires special attention, which is a symbol of the extraterrestrial origin of the feelings of the heroes. Lighting is muted and has a reddish tint associated with the beginnings of feelings and making the outlines of the characters softer and more delicate. The costumes of the heroes a simple cut and white color, symbolize the simplicity, openness and innocence of the heroes’ love.

The selected camera angle first shows the characters in full growth and then their faces in close–up, replaying how close they have become during their joint history ( Singin’ in the Rain 30:35). Camera movement is circular; this solution is traditional for filming love scenes and conveys that the feelings of Don and Katie are felt by them as a flight.

Diegetic sound is confident, emphasizing Don’s certainty in the power of falling in love. Non-diegetic sounds are absent in this scene, allowing the reader to feel how, at the moment of recognition, the surrounding world ceases to exist for Don and Katie, and they only see each other.

Thus, the features of the construction of the frame of Don singing scene allow for conveying the beauty of the emerging feelings through thoughtful details such as props, costumes, sounds, lighting and camera movement.

Singin’ in the Rain . Directed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, performances by Donald O’Connor and Debbie Reynolds, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952.

- Cinematography of the "Thelma and Louise" Film

- The Restaurant Scene in the “Ladri di Biciclette” Film

- “Boyz n the Hood”: Movie Analysis

- Analysis of “Raise the Red Lanterns”: The Value of Mise-En-Scene

- Mise-En-Scene, Shots and Sound: Hitchcock’s Spare Use of Cinematic Repertoire in Sabotage’s Murder Sequence

- Finding Oneself in "Thelma and Louise" Film

- Ambiguity of "The Lost Highway" Film

- Ryan Coogler's Black Panther: Afrofuturism

- The Past's Influence on the "Vertigo" Film

- Spike Lee's Movie Do the Right Thing Review

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 11). The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-singin-in-the-rain-movie-a-scene-analysis/

"The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis." IvyPanda , 11 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-singin-in-the-rain-movie-a-scene-analysis/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis'. 11 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis." January 11, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-singin-in-the-rain-movie-a-scene-analysis/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis." January 11, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-singin-in-the-rain-movie-a-scene-analysis/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Singin’ in the Rain Movie: A Scene Analysis." January 11, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-singin-in-the-rain-movie-a-scene-analysis/.

Singin' in the Rain

By gene kelly , gene kelly, singin' in the rain literary elements.

Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen

Leading Actors/Actresses

Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor, Debbie Reynolds

Supporting Actors/Actresses

Jean Hagen, Millard Mitchell

Comedy, Musical, Romance

Nominated for 2 Oscars: Best Music-Scoring of a Musical Picture, Best Actress in a Supporting Role-Jean Hagen

Date of Release

Arthur Freed

Setting and Context

1927 Hollywood transition from silent era into talkies

Narrator and Point of View

There is no narrator, but we follow Don Lockwood's perspective throughout.

Tone and Mood

Comedic, Dramatic, Romantic, Silly, Fun, Feel-Good

Protagonist and Antagonist

Protagonists are Don, Cosmo and Kathy. Antagonist is Lina.

Major Conflict

The first conflict is the question of whether Lockwood and Lina will be able to successfully transition into careers in "talkies." The second is Lina's desire to control and limit Kathy's career. After Kathy is used as the voice for Lina in her first talkie Lina demands that she continue to be her voice and give up her own career.

Lina, in search of attention from the crowd, is asked to sing. Cosmo, Simpson, and Lockwood raise the curtain to reveal to the adoring audience that it was not Lina's voice in the film, but Kathy's. Don announces that Kathy is the true voice behind the film and the audience cheers for her.

Foreshadowing

The introduction of the "talking picture" and the party guests' shrugging it off foreshadows the studio's inability to move with the times and make a successful talkie at first.

Understatement

Cosmo's contribution to Don's fame is understated. Cosmo is, indeed, the brains behind the operation.

Innovations in Filming or Lighting or Camera Techniques

The film itself is an allusion to the silent film era. Allusions are made to silent films, to King Lear, Ethel Barrymore.

Lina is one of the biggest stars on the planet, but her voice is so off-putting that if it was revealed to the public she would fall from grace.

Parallelism

Kathy and Lina are placed in parallel. They are opposites of sorts. Where Kathy is wholesome, Lina is jaded. Where Kathy is talented, Lina is not.

Singin’ in the Rain Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Singin’ in the Rain is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Study Guide for Singin’ in the Rain

Singin' in the Rain study guide contains a biography of Gene Kelly, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Singin' in the Rain

- Singin' in the Rain Summary

- Character List

- Director's Influence

Essays for Singin’ in the Rain

Singin' in the Rain essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Singin' in the Rain by Gene Kelly.

- Moses Supposes in Style: A Close Reading of an Iconic Scene in Singin' in the Rain

Wikipedia Entries for Singin’ in the Rain

- Introduction

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Singin' in the Rain Summary. Don Lockwood is a very popular silent movie star who started out as a singer and dancer on the vaudeville circuit, then a stuntman, and then transitioned into becoming a star. The movie studio has created a fake romance between Don and his leading lady, Lina Lamont, to generate public interest about their films.

Summary: Singin' in the Rain opens at the 1927 premiere of The Royal Rascal, a costume drama starring above-the-credit silent film stars Don Lockwood and Lina Lamont. On the red carpet, Don tells the adoring crowds about his training in the arts of high culture, framed by the motto, 'Always dignity'. A montage shows us.

Singin' in the Rain Summary and Analysis of Part 1: Hollywood. Summary. The film opens on the three stars of the film with their backs to the camera, holding umbrellas. As the music swells to a climax, each spins around and begins walking in place and singing the title song. The credits roll. As the credits end, we see the exterior of a movie ...

Co-directed by Stanley Donen and star Gene Kelly, Singin' in the Rain tells the story of the transition from silent film to talking pictures in the 1920s, and the birth of the American movie musical, with beloved stars Debbie Reynolds, Gene Kelly, Jean Hagen, and Donald O'Connor all contributing star-making performances.

Lights, camera, action! Singin' in the Rain starts off at the 1927 premiere of the new Monumental Pictures film The Royal Rascal. It stars Don Lockwood and Lina Lamont, two of the brightest silent film stars in Hollywood. Don tells the crowd all about his cultured, utterly refined upbringing, while flashbacks reveal that he's lying his pants off.

Get all the details on Singin' in the Rain: Analysis. Description, analysis, and more, so you can understand the ins and outs of Singin' in the Rain.

Conclusion. Incredibly colorful and beyond the time, even timeless. Singin' in the Rain is a sweet musical film that makes the viewer not able to understand how time passed while watching, makes us admire the dances of the actors, arouses the desire to play in musicals, presents us some of the curious elements of the period, the songs legend, colors and costumes.

The Role of Satire in Singing in the Rain. When it comes to comedy, one of the easiest ways to make people laugh is by criticizing and exaggerating modern-day mishaps, or in more simplistic terms, through the use of satire.

Rated. Unrated. Runtime. 103 min. Release Date. 03/27/1952. Classic Hollywood productions rarely had two directors, and if they did, the result was a studio creation and not shaped by the vision of a single auteur. The exception is Singin' in the Rain, the 1952 release from co-directors Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, which remains ...

The film is above all lighthearted and happy. The three stars-- Gene Kelly, Donald O'Connor and 19-year-old Debbie Reynolds--must have rehearsed endlessly for their dance numbers, which involve alarming acrobatics, but in performance they're giddy with joy. Kelly's soaking-wet "Singin' in the Rain" dance number is "the single most memorable ...

Singin' in the Rain is a 1952 American musical romantic comedy film directed and choreographed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, starring Kelly, Donald O'Connor and Debbie Reynolds, and featuring Jean Hagen, Millard Mitchell, Rita Moreno and Cyd Charisse in supporting roles. It offers a lighthearted depiction of Hollywood in the late 1920s, with the three stars portraying performers caught up ...

I think that it would be pretty accurate because it gives a lot of information on early film production and many scenes filmed for singing in the rain portray early motion picture. 4. In the scene where Don is going to the party (starting at time code 14:51), we see a street scene as he first rides with Cosmo and then with Kathy.

Respect and Reputation. Blame Hollywood. Almost everybody in Singin' in the Rain is obsessed with his or her reputation. Don wants to be respected as a "real" actor—not some guy in knickers that pantomimes and pulls sil...

Singing in the Rain is an American comedy musical film starring Gene Kelly, Debbie Reynolds, Donald O'Connor and Jean Hagen, and directed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen. It offers a comic depiction of Hollywood, and its transition from silent films to talking films. Throughout the movie, people could see many different elements that make the ...

Cinema. Clearly, a major theme of Singin' in the Rain is the movie business, as Lockwood is a major film star and much of the film is set on a Hollywood soundstage. Throughout, we see the ins and outs of the movie business, a perspective which at once elevates and demystifies the world of film. On the one hand, we see how illusory so much of ...

Plot Summary. Singing in the Rain is a children's picture book written using Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown's lyrics from their song of the same title. Tim Hopgood illustrated the colorful book, and Oxford University Press published it in 2018. The artwork is mixed media, and the book is 32 pages long. As the story begins, a little girl in ...

The scene from the movie Singin' in the Rain, where Don Lockwood confesses Katie's feelings with a song, is iconic. The importance of this scene is conveyed, among other things, with the help of formal film elements, such as the construction of the mise-en-scene, cinematography and sound. Get a custom essay on The Singin' in the Rain ...

Download. Singin' In the Rain Music Analysis Singin' In The Rain (Kelly/Donan, 1952) is known to be one of best musicals ever made and one of the funniest movies of its time. This statistic can be attributed to the musical numbers that it incorporates. Singin' in the Rain uses popular music of its time that people may already be familiar ...

Essays for Singin' in the Rain. Singin' in the Rain essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Singin' in the Rain by Gene Kelly. Moses Supposes in Style: A Close Reading of an Iconic Scene in Singin' in the Rain

https://letterboxd.com/92nathan/https://twitter.com/92nathanhttps://www.instagram.com/nathan_sawczakHollywood has experienced a lot of changes throughout the...

In 1952, Gene Kelly tap-danced his way into cinemas with the beautiful and joyous musical, Singin' in the Rain. Nearly seventy years later, the movie still c...

Singin' in the Rain is considered by many to be the greatest Hollywood musical of all time. When asked to cite the single most archetypal Hollywood movie musical of the last 100 years, most would cite Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen's lavish film. Contemporary films like La La Land cite it as inspiration and seek to revive its wholesome charms for modern audiences.

Study Guide for Singin' in the Rain. Singin' in the Rain study guide contains a biography of Gene Kelly, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis. About Singin' in the Rain; Singin' in the Rain Summary; Character List; Cast List; Director's Influence; Read the Study Guide for Singin' in ...