ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY

Voice for the army - support for the soldier, the russo-ukrainian war: a strategic assessment two years into the conflict.

by LTC Amos C. Fox, USA Land Warfare Paper 158, February 2024

In Brief Examining the strategic balance in the Russo-Ukrainian War leads to the conclusion that Russia has the upper hand. In 2024, Ukraine has limited prospects for overturning Russian territorial annexations and troop reinforcements of stolen territory. Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against Russian offensive action decreases as U.S. financial and materiel support decreases. Ukraine needs a significant increase in land forces to evict the occupying Russian land forces.

Introduction

The Russo-Ukrainian War is passing into its third year. In the period leading up to this point in the conflict, the defense and security studies community has been awash with arguments stating that the war is a stalemate. Perhaps the most compelling argument comes from General Valery Zaluzhny, former commander-in-chief of Ukraine’s armed forces, who stated as much in an interview with the Economist in November 2023. 1 Meanwhile, there are others, including noted analyst Jack Watling, who emphatically state the opposite. 2

Nonetheless, two years in, it is useful to objectively examine the conflict’s strategic balance. Some basic questions guide the examination, such as: is Ukraine winning, or is Russia winning? What does Ukraine need to defeat Russia, and conversely, what does Russia need to win in Ukraine? Moreover, aside from identifying who is winning or losing the conflict, it is important to identify salient trends that are germane not just within the context of the Russo-Ukrainian War, but that are applicable throughout the defense and security studies communities.

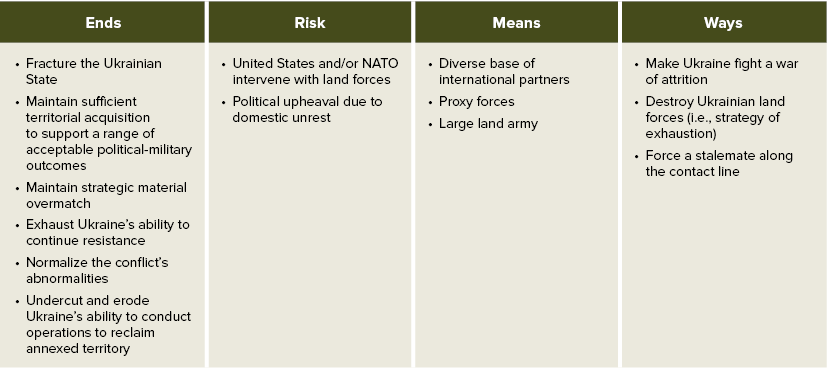

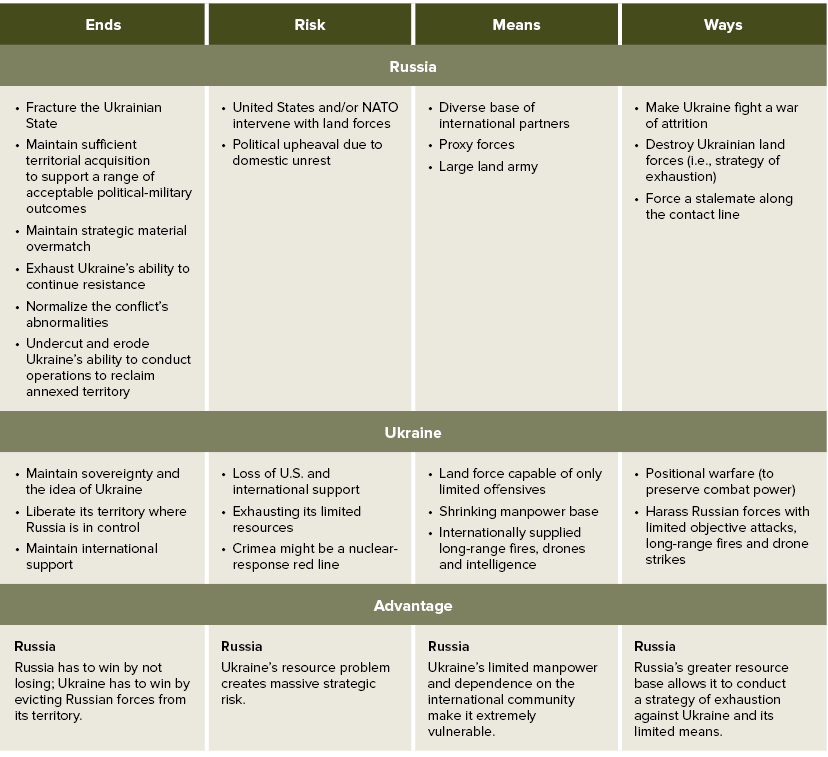

This article addresses these questions through the use of the ends-ways-means-risk heuristic. In doing so, it examines Russia and Ukraine’s current strategic dispositions, and not what they were in February 2022, nor what we might want them to be. Viewing the conflict through the lens of preference and aspiration causes any analyst to misread the strategic situation. The goal of this article, however, is to take a sobering look at the realities of the conflict, offer an assessment of the situation, and posit where the conflict is likely to go in 2024.

The overall conclusion is that Russia is winning the conflict. Russia is winning because it possesses its minimally acceptable outcome: the possession of the Donbas, of the land bridge to Crimea, and of Crimea itself. This victory condition, however, is dependent upon Ukraine’s inability to generate a force sufficient to a) defeat Russia’s forces in each of those discrete pieces of territory; b) retake control of that territory; and c) hold that territory against subsequent Russian counterattacks. No amount of precision strike, long-range fires or drone attacks can compensate for the lack of land forces Ukraine needs to defeat Russia’s army and then take and hold all that terrain. Thus, without an influx of resources for the Ukrainian armed forces—to include a significant increase in land forces—Russia will likely prevail in the conflict. If U.S. support to Ukraine remains frozen, as it is at the time of this writing, then Russian victory in 2024 is a real possibility.

Laying the Groundwork: Situational Implications

Moreover, several other important implications emerge for the defense and security studies community. First, land wars fought for control of territory possess inherently different military end states than irregular wars, counterinsurgencies and civil wars. Therefore, militaries must have the right army for the conflict in which they are engaged. A counterinsurgency army or constabulary force, for instance, will not win a war for territory against an industrialized army built to fight and win wars of attrition. This is something policymakers, senior military leaders and force designers must appreciate and carefully consider as they look to build the armies of the future.

Second, land wars fought for control of territory require military strategies properly aligned to those ends. Therefore, militaries must have the right strategy for the conflict, or phase of the conflict, in which they are engaged. A strategy built on the centrality of precision strike but lacking sufficient land forces to exploit the success of precision strike, for instance, will not win a war for territory—especially against an industrialized army built to fight and win wars of attrition. Policymakers and senior military leaders must periodically refresh and reframe their political ends and military strategies according to their means; otherwise, they risk a wasteful strategy that fritters away limited resources in the pursuit of unrealistic goals.

Third, despite statements to the contrary, physical mass—in this case, more manpower—is more important than precision strike and long-range fires where the physical possession of territory is a critical component of political and military victory for both states. Physical mass allows an army to hold and defend territory. The more physical mass an army possesses, the more resilient it is to attacks of any type and the more difficult and costly it is to defeat—whether that be in munitions expended, number of attacks conducted or lives lost.

Fourth, a prepared, layered and protected defense, like that of Russia’s along the contact line with Ukraine’s armed forces, is challenging to overcome. This challenge grows exponentially if the attacker lacks sufficiently resilient and resourced land forces that are capable of a three-fold mission: (1) defeating the occupying army; (2) moving into the liberated territory; and (3) controlling that land. Armies that are designed to deliver a punch but lack the depth of force structure to continue advancing into vacated or liberated territory after a successful attack, and subsequently are unable to stave off counterattacks, are of little use beyond defensive duty. This finding is at odds with conventional wisdom regarding future force structure that posits that future forces should be small and light and should fight dispersed.

Fifth, Carl von Clausewitz warns that, “So long as I have not overthrown my opponent, I am bound to fear he may overthrow me. Thus, I am not in control: he dictates to me as much as I dictate to him.” 3 The Russo-Ukrainian War has reiterated Clausewitz’s caution: as neither army is able to outright defeat the other, Russia and Ukraine are locked in a long war of attrition, which is fueling the stalemate to which Zaluzhny refers and Watling rejects. The writing between the lines thus suggests that, when confronted with war, a state must unleash a military force that is capable of both defeating its adversary’s army and simultaneously accomplishing its supplemental conditions of end state, to include taking and holding large swaths of physical terrain. Without defeating an adversary’s army—regardless of its composition—one must then always contend with the possibility that tactical military gains are fleeting. Moreover, by first defeating an adversary’s army, one might turn what would otherwise be a long war of attrition into a short war of attrition.

Russian Strategic Assessment

Russia’s strategic ends can be summarized as:

- fracture the Ukrainian state—politically, territorially and culturally;

- maintain sufficient territorial acquisitions to support a range of acceptable political-military outcomes;

- maintain strategic materiel overmatch;

- exhaust Ukraine’s ability to continue fighting—both materially and as regards Ukrainian support from the international community;

- normalize the conflict’s abnormalities; and

- undercut and erode Ukraine’s ability to conduct offensive operations to reclaim annexed territory.

When viewing all of these ends collectively, it is clear that denationalization of the Ukrainian state is Russia’s strategic end in this conflict. Raphael Lemkin defines denationalization as a state’s deliberate and systematic process of eroding or destroying another state’s national character and national patterns (i.e., culture, self-identity, language, customs, etc.). 4 Russia’s policy and military objectives have evolved ever so slightly since February 2022, but Ukraine’s denationalization remains at the heart of the Kremlin’s strategic ends. The Kremlin’s objectives in 2022 included unseating President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, ending Ukrainian self-rule and replacing it with a Russian partisan political leadership, and annexing a significant portion of Ukraine’s territory. To that end, Russian President Vladimir Putin spoke at the time of “denazifying” and “demilitarizing” Ukraine, while also forcing Kyiv to remain politically and militarily neutral within the international community’s network of political and military alliances. 5 Putin reaffirmed these policy aims during a December 2023 press conference in Moscow. 6 Nonetheless, Russia’s military activities—which have not made advances toward Kyiv since Moscow’s initial assault on the capital failed in April 2022—do not indicate any renewed effort to remove Zelenskyy or Ukraine’s government from power. There is, though, a real possibility of this occurring in 2024, especially if U.S. support to Ukraine remains frozen for the foreseeable future.

It does appear, however, that the Kremlin is attempting to elongate the conflict in time and cost such that Moscow outlasts both Kyiv’s financial and military support from the international community and Ukraine’s material means to continue attempting offensive military activities to reclaim its territory. In doing so, the Kremlin likely intends to accelerate Ukraine to strategic exhaustion and subsequently force Kyiv to broker a peace deal.

As noted recently, Russia’s territorial ambitions of Ukraine likely operate along a spectrum of acceptable outcomes. 7 Presumably, as noted above, Russia’s minimally acceptable outcome—or the minimal territorial holdings that the Kremlin is satisfied to end the war possessing—include retention of the Donbas, the land bridge to Crimea and Crimea (see Figure 1). For clarity’s sake, the land bridge to Crimea includes the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts—the two oblasts that provide a unified ground link between the Donbas and Crimea. The land bridge is important because it provides Russia a ground-based connection from Russian territory between the occupied Donbas and occupied Crimea, thus simplifying the governance, defense and retention of Crimea.

2024 will be a pivotal year for Ukraine. If the United States elects a Ukraine-friendly president, then Kyiv can likely expect continued financial and military support from the United States in 2025. On the other hand, if it does not elect a Ukraine-friendly president, then Kyiv can anticipate a range of decreasing financial and military support in the defense of their state against Russian denationalization efforts.

At the same time, the appearance of Chinese, North Korean and Iranian weapons and munitions on the Ukrainian battlefield indicate that Russia is facing its own challenges keeping up with the conflict’s attritional character. 8 Though the degree to which external support is helping keep its war-machine going in Ukraine is challenging to discern through open-source information, we do know that external support allows the Russian military to overcome some of its defense industry’s production and distribution shortfalls. In turn, Chinese, North Korean and Iranian support allows the Kremlin to continue elongating the conflict in time, space and resources with the goal of exhausting Ukraine’s military and Kyiv’s capacity to sustain its resistance to Russia.

Russia has already weathered much of the risk associated with invading Ukraine. Economic sanctions hit hard early on, but Russian industry and its economy have absorbed those early hardships and found ways to offset many of those challenges—including through Chinese, North Korean and Iranian support. 9 Further, the West’s gradual escalation of weapon support to Ukraine allowed Russia to develop an equally gradual learning curve to those weapons, and, in most cases, nullify any “game-changing” effects that they might have generated if introduced early in the conflict and with sufficient density to create front-wide effects. 10 Instead, the slow drip of Western support allowed Russian forces to observe, learn and adapt to those weapon systems and develop effective ways to counter Western technology and firepower. 11 The Russian military’s learning process has allowed it to recover from its embarrassing performance early in the conflict and draw into question the U.S. and other Western states’ strategy of third-party support to Ukraine. 12

The primary risks that the Russo-Ukrainian War poses to Russia today are: (1) The United States and/or NATO might intervene with their land forces on behalf of Ukraine; and (2) political upheaval might occur as a result of domestic unrest. The risk of U.S. and NATO intervention with land forces is low, and will likely remain that way, because of the fear of Russian escalation with tactical or strategic nuclear weapons. 13 Although the likelihood of Russian nuclear strikes in Ukraine is also low, Russian political leaders regularly unsheathe nuclear threats to oppose and deter unwanted activities. 14 Dmitry Medvedev, Deputy Chairman of Russia’s Security Council, recently threated Ukraine with a nuclear response if Ukraine attacked Russian missile launch sites within Russia with Western-supplied, long-range missiles. 15 This follows Russia’s repositioning of some of its nuclear arsenal to Belarus in the summer of 2023. 16 Nonetheless, short of the commitment of U.S. or NATO land forces, or the potential loss of the Crimean peninsula, Russia’s likelihood to actually use nuclear weapons remains low.

To the second risk—that of domestic unrest creating political instability—Putin and his coterie of supporters continue to use old Russian methods to offset this problem. Arrests, assassinations, disappearances and suppression are the primary methods employed against this challenge and to deter domestic opposition to his policies vis-à-vis Ukraine. 17 The assassination of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner Group, in August 2023, is perhaps the most high-profile example of this technique. 18 Further, the periodic disappearances and imprisonments of Alexei Navalny is another example of the Putin regime attempting to keep political opposition quiet. 19 Longtime Kremlin henchman, Igor Girkin, who was extremely critical of Putin and of the Kremlin’s handling of the war in Ukraine during 2023, was sentenced to four years in prison in January 2024. 20 Moreover, the suppression of journalists within Russia is spiking as Putin seeks to silence opposition and punish dissent in the wake of the strong economic and domestic upheavals caused by his war. 21

In addition, former U.S. Army Europe commander, Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, USA, Ret., states that Russia mobilizes citizens from its peripheral and more rural areas for its war in Ukraine. 22 Many of these individuals are ethnic minorities and therefore of lesser importance in Putin’s (and many Russians’) social hierarchy. 23 According to Hodges, by pulling heavily from the areas outside of Russia’s major population centers, to include Moscow and St. Petersburg, Putin is able to offset a significant potential domestic unrest by thrusting the weight of combat losses into the state’s far-flung reaches, to be borne by those with less social status. 24 Doing so buys Putin more time to continue the conflict and attempt to bankrupt both Ukrainian and Western resolve.

Means are the military equipment and other materiel that a military force requires to create feasible ways. Moreover, means operate as the strategic glue that binds a military force’s ends with their ways. As mentioned in the Ends section, Russian industry appears to be challenged by the Russian armed forces’ demand for military equipment and armaments. The Russian armed forces’ ways—or approach to operating on the battlefield against Ukraine—is resource-intensive. Early Russian combat losses—the result of stalwart Ukrainian fighting coupled with inept Russian tactics—generated massive logistics challenges for Russia. Further, Russia has continued to fight according to long-standing Russian military practice: lead with fires, and move forward incrementally as the fires allow. The incremental advances, however, have also come at extreme costs in men and materiel. Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, for instance, refer to Russian fighting at the battles of Mariupol and Bakhmut as relying on “meatgrinder tactics” in which human-wave attacks are used to advance Russian military interests. 25 As of 20 February 2024, Russia has lost 404,950 troops, 6,503 tanks, 338 aircraft and 25 ships, among many other combat losses; the losses that they have afflicted on Ukrainian forces remains largely unknown. 26

As noted by Kyrylo Budanov, Ukraine’s chief intelligence officer, Russia’s use of proxy forces is the primary way in which they have sought to offset land force requirements and to relieve some of the stress on their own army. 27 The contractual proxy, the Wagner Group, and the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Armies (DPA and LPA, respectively)—both cultural proxies—were the primary proxies used between the renewed hostilities of February 2022 through the summer of 2023. The Wagner Group’s attempted coup in June 2023 naturally cooled the Kremlin’s reliance on it. At the same time, Russia’s military operations have become less offensive and more defensive, seeking to retain land already annexed, as opposed to confiscating more Ukrainian territory. Consequently, Moscow’s demand for more land forces and disposable infantry has somewhat diminished.

Nonetheless, fighting a defensive war along the contact line across the Donbas and the land bridge to Crimea has increased Russia’s need for drones and strike capability. As noted previously, Russia has maintained good diplomatic relationships with China, North Korea and Iran; this has allowed the Russian armed forces access to important weaponry from those states for use on the battlefield in Ukraine. Thus, despite the potential for economic sanctions to cripple Russia’s ability to wage war, the Kremlin has diversified its bases of economic and military power to ensure that it has the means it requires to continue the conflict with Ukraine. Moreover, this has allowed Russia to overcome many of the advantages that Ukraine obtained through the introduction of U.S. and other Western-supplied military aide and so to return theater-level stasis to the battlefield. Put another way, Russia’s ability to diversify its means has allowed it to generate a stalemate—which works in Moscow’s favor—and to keep the conflict going, with the goal of outlasting the international community’s military support and exhausting Ukraine’s ability to continue fighting.

Considering Russia’s diverse bases of power, it is likely that battlefield stasis—or stalemate—will continue through 2024. In fact, this is probably Russia’s preferred course of action. It is likely that Russia is seeking to elongate the conflict through the upcoming U.S. presidential election, in hopes that the United States will elect a president who is not as friendly toward Kyiv and the Ukrainian fight for sovereignty—namely, one that will eliminate U.S. support to Ukraine’s war effort altogether.

Ways are the specific methods an actor seeks to obtain their ends, with deference to their means. Ways consist of many supporting lines of operation or lines of effort. Moreover, many complimentary campaigns and operations can exist simultaneously within a strategy’s ways. Further, from a taxonomical position, the dominant approach or line of operation (or effort) within a strategy’s ways often becomes shorthand for a combatant’s general strategy. To that end, Russia’s strategy can be considered a strategy of exhaustion.

Russia’s strategy of exhaustion can be broken into five lines of effort:

- incrementally increase territorial gains to support negotiations later down the line;

- fortify territorial gains to prevent Ukrainian efforts to retake that land;

- destroy Ukraine’s offensive capability to prevent future attempts to retake annexed territory;

- temporally elongate the conflict to outlast U.S. and Western military support; and

- temporally and spatially elongate the conflict to exceed Ukraine’s manpower reserves.

Early in the conflict, Russia’s strategy focused on the conquest of Ukrainian territory. The scale is up for debate, but Russian military operations indicated that they intended to take Kyiv, the oblasts that paralleled both sides of the Dnieper River, and all the oblasts east of the Dnieper to the Ukraine-Russia international boundary. This operation floundered, but Russia was able to extend their holdings in the Donbas, retain Crimea and obtain the land bridge to Crimea—which had been a goal of their 2014–2015 campaign, one that they came up short on at that time. 28

As noted in the Means section above, Russia attempted limited territorial gains through 2023. 29 The attainment of any further Ukrainian territory is likely only for negotiation purposes. With that, if and when Russia and Ukraine reach the point in which they must negotiate an end to the conflict, Russia can offer to “give back” some of Ukraine’s territory as a bargaining chip so that it can hold onto what it truly desires: retention of the Donbas, the land bridge to Crimea and Crimea. This is a trend that will likely continue through 2024; we can expect to see Russia attempting to extend their territorial holdings along the contact line, arguably for the purpose of improving their bargaining position if and when negotiations between the two states come to fruition.

Further, Russia seeks to cause Ukraine’s war effort to culminate by depleting Ukrainian materiel and manpower—both on hand and reserves. Putin states that Russia currently has 617,000 soldiers participating in the conflict. The number of combat forces within Ukraine is unknown. 30 Nonetheless, significant battles, such as Mariupol, Bakhmut, Avdiivka and others, while tough on Russia, are of serious concern for Ukraine. Russia’s population advantage in relation to Ukraine means, quite simply, that the Kremlin has a much deeper well from which to generate an army than does Kyiv. Therefore, Russia continues to leverage its population advantages over Ukraine in bloody battles of attrition to exhaust Ukraine’s ability to field forces. The Kremlin’s attempt to cause the Ukrainian armed forces to culminate shows signs of success. In December 2023, for instance, Zelenskyy stated that his military commanders were asking for an additional 500,000 troops. 31 Zelenskyy called this number “very serious” because of the impact it would have on Ukrainian civil society. 32 Budanov more recently echoed Zelenskyy, stating that Ukraine’s position was precarious without further mobilizations of manpower. 33

Russia’s strategy of exhaustion, therefore, appears to be working. Russian mass has generally frozen the conflict along the lines of Russia’s minimally acceptable outcome noted previously, i.e., the retention of the Donbas, the land bridge to Crimea and Crimea. This reality flies in the face of General Chris Cavoli, commander of U.S. Army European Command and Supreme Allied Commander Europe, who emphatically stated: “Precision can beat Mass. The Ukrainians have showed that this past autumn. But it takes time for it to work, and that time is usually bought with space. And so, to use this method, we need space to trade for time. Not all of us have that. We have to compensate for this in our thinking [and] our planning.” 34

While U.S. and Western-provided precision strike might have helped Ukraine in some early instances within the conflict, Russian mass, coupled with Russian’s intention on retaining territory, is disproving Cavoli’s hypothesis. Further, the sacrifice of territory for time that Cavoli refers to actually plays to the favor of Russian rather than Ukrainian political-military objectives. The land that Ukrainian forces have involuntarily ceded to Russian land forces is not likely to be retaken by precision strike. Ukraine will require a significant amount of land forces, supported by joint fires and precision strike, to dislodge Russian land forces, to control the retaken territory, and to hold it against subsequent Russian counterattacks.

Russian Strategic Assessment: Summary

If winning in war is defined by one state’s attainment of their political-military objectives at the cost of their adversary’s political-military objectives, then Russia appears to possess the upper-hand through two years of conflict (see Table 1). Russia’s strategy of exhaustion and territorial annexation appears to be working, albeit at high costs to the Russian economy and the Russian people. Russia has had to diversify its bases of power to maintain the war stocks required to execute its strategy of exhaustion, and it has had to exact a heavy toll on the Russian people to conduct the bite-and-hold tactics needed to make its territorial gains. Considering that Russia is largely on the defensive now, holding its position along the time of contact, the toll on the Russian people will likely decrease in the coming year. Moreover, considering its heavily fortified defensive position, it will likely maintain the upper hand on the battlefield through 2024.

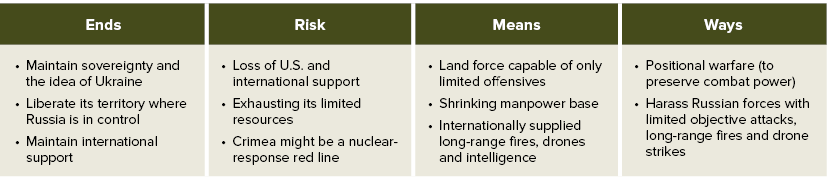

Ukrainian Strategic Assessment

Ukraine’s focus remains to liberate its territory from Russian occupation and restore its 1991 borders with Russia, which includes restoring its sovereignty over the Donbas and Crimea. 35 Beyond that, Ukraine continues to work to strengthen its bonds with the West. From security assistance partnerships to working on joining the European Union (EU), Zelenskyy and his government continue to press the diplomatic channels to maintain and gain political, military and economic support from the international community. 36

Kyiv’s efforts to join the EU and continue to maintain support from the international community are arguably much more realistic than its objective to remove Russian military forces—to include Russian proxies—from Ukraine’s territory. The classic board game Risk provides an excellent analogy for what Ukraine must do. In Risk, to claim or reclaim a piece of territory on the map, a player must attack and defeat the army occupying a territory. If (and when) the attacker defeats the defender, the attacker must then do two things—not just one. The attacker must not only move armies into the conquered territory, but he must also leave at least one army in the territory from which he initiated his attack. In effect, any successful attack diffuses combat power, and this is on top of any losses suffered during the attack. And yet, the attacker must identify the appropriate balance of armies between the newly acquired territory and the territory from which he attacked. An imbalance in either territory creates an enticing target for counterattack by the vanquished occupier.

Ukraine finds itself in just such a position; however, instead of just attacking to retake one small portion of its territory, Ukraine must work to reclaim nearly 20 percent of its territory. 37 Compounding this problem is the size of Russia’s occupation force. As noted previously, Putin indicated that Russia has 670,000 soldiers committed to the conflict—this is more than a 200 percent increase from Moscow’s initial 190,000-strong invasion force. 38 It is challenging to verify Putin’s numbers, or to identify how those numbers are split between combat and support troops, and troops operating in Ukraine vice support troops committed to the conflict but operating in Russia. Nonetheless, for the sake of argument, let’s assume all 670,000 Russian troops are in Ukraine. Using the traditional attacker-to-defender heuristic, which states that a successful attack requires three units of measure to every one defensive unit of measure (3:1), and using individual troops as the unit of measure, we find that a successful Ukrainian attack would require more than two million troops to execute the sequence outlined above.

Are two million troops really what’s required to evict Russian land forces from Ukraine and hold it against a likely counterattack? Some analysts—both old and current—suggest that the 3:1 ratio is flawed, not relevant, or both. 39 Or does modern technology obviate the need for some of those land forces, as Cavoli suggested?

The fact of the matter remains: Long-range precision strike, drones of all types and excellent targeting information have done what complimentary arms and intelligence have always done—they have supported the advance or defensive posture of competing land forces, but they have not supplanted it. Moreover, technology must be viewed in the context of both the operations that it is supporting, but also the adversarial operations that it seeks to overcome. If it is correct that Russian strategy is primarily concerned with retaining its territorial acquisitions at this point, and thus Russian military forces are focused on conducting defensive operations, and that Ukrainian land forces do not have the numbers to conduct the attack-defeat-occupy-defend sequence in conjunction with those other components of combined arms operations, then the precision strike, drones and targeting information might be the window dressing for a futile strategic position. Seen in this light, Kyiv’s strategy is out of balance; that is, Kyiv’s ends exceed the limits of its means. The effect of this situation has contributed to the conflict being characterized as a war of attrition.

The greatest risk to Ukraine’s strategy for winning the war against Russia is the loss of U.S. political, financial and military support. The loss of support from other European partners closely follows in order of importance. A great deal has been written about this in other publications, and as a result, this section will examine other strategic risks.

One of Kyiv’s biggest strategic risks is exhausting or diffusing its military force so much so that Russian land forces might attack and confiscate additional Ukrainian land through increasingly vulnerable positions. For instance, Ukraine’s counteroffensive in the summer of 2023 could have very well created so-called soft spots in Ukraine’s lines through which a localized counterattack might create an operational breakthrough. That did not happen, but this situation is something that strategic military planners must consider if Zelenskyy and his government truly intend to liberate all of Ukraine’s territory from Russia.

In addition, the reclamation of Crimea is something that is potentially a game-changing situation. Putin has stated the Crimea is Russia’s red line, indicating that a nuclear retort could likely coincide with any legitimate Ukrainian attempt to retake the peninsula. 40 Therefore, Putin’s red line is something policymakers and strategists in Kyiv would have to consider before enacting any attempt to seize and hold Crimea. Might Putin’s red line be a bluff? Perhaps. But the threat of nuclear strike, coupled with Putin’s move of nuclear weapons into Belarus and his repositioning of nuclear strike weapons close to Ukraine earlier in the conflict, demonstrate some credibility to the threat.

As noted extensively in the section on Ukraine’s strategic ends, manpower is the biggest resource inhibiting Ukraine from attaining its political-military objectives. 41 As Zaluzhnyi notes in a recent essay, Ukraine’s recruiting and retention problems, coupled with a fixed population, no coalition to share the manpower load and two years of killed in action and other casualties, have put Ukraine in this position. 42 It is not a position that they are likely to overcome, even if Kyiv initiates a conscription system. Considering the 3:1 math outlined above, Kyiv theoretically needs to generate a trained army of more than two million troops if it hopes to remove Russian land forces from Ukraine. Moreover, if technology enthusiasts are correct and precision strike weapons, drones and advanced intelligence could shift the 3:1 ratio to perhaps 2:1 or even 1.5:1 in open combat, that advantage would shift back toward the defenders in urban areas. This is because of considerations of International Humanitarian Law and the challenges of targeting in more respective operating environments—a useful segue to discuss combat in urban areas.

The math gets even more challenging when this context is applied. Trevor Dupuy writes that, “The 3:1 force ratio requirement for the attacker cannot be of useful value without some knowledge of the behavioral and other combat variable factors involved.” 43 As such, factors such as the operating environment, the type of opponent and the method in which they have historically fought must also be applied to the situation. Theory and military doctrine both suggest that the ratio for attacker to defender in urban operating environments increases from 3:1 to 6:1. 44

Considering the large number of cities in Ukraine’s occupied areas, as well as their breadth and the depth of the front that Kyiv’s forces would have to work through, this poses a significant challenge. Hypothetically, Russian forces might strong-point places like Donetsk City, Mariupol, Melitopol, Simferopol and Sevastopol, creating a network of interlocked spikes in required strength—from 3:1 to 6:1—and thus increasing the overall combat power required by Ukraine to remove Russian military forces from the country.

Moreover, if Ukraine is able to remove Russian land forces from Ukraine, the question of insurgency must also come into the equation. Retaking physical territory is one thing; securing the loyalty of the people in that territory is quite another. Vast portions of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, as well as the entirety of Crimea, have been occupied by Russia for a decade. The political loyalties, cultural affiliation and domestic politics of the population in those areas are far from certain at this point. Thus, the chance for an insurgency in the Donbas and Crimea must also be considered when calculating the means—in this case, human capital—required to conduct operations to reclaim and hold lost territory.

Already running short of needed ammunition, to include artillery, missiles and air defense missiles, Ukraine’s ammunition crunch is likely to accelerate through 2024. This is yet another concern raised by Zaluzhnyi in his recent essay on what Ukraine needs to survive and win against Russia. 45 At the time of this writing, Congress has failed to approve the Department of Defense’s latest funding requests for Ukraine. Whether they move forward on that remains to be seen. Nonetheless, for the purpose of continuing the discussion, let’s assume that Congress approves the funding in March 2024. But by that time, that lapse in funding will have created a lapse in support to Ukraine, exacerbating an already tenuous ammunition situation and potentially creating something far more critical. As it currently stands, Ukrainian units are approaching the point at which they are able to do little more than defend their positions and maintain the front lines. 46 Moving forward in time, Ukrainian units will not be able to conduct robust offensive operations—which would require methodically penetrating Russian defensive belts and destroying Russian land forces in stride—because they will not have enough ammunition.

A lag will also develop between the time in which Congress authorizes funds for Ukraine, the time that the military can deliver the equipment associated with those funds to Ukraine’s armed forces and the time that the Ukrainian armed forces can put that equipment to use on the battlefield. In the interim period between Congressional approval and the Ukrainian forces putting the equipment to use in the field, the risk of Russian tactical and operational military offensive operations increases, while Ukraine’s risk of successful defensive operations decreases. Therefore, one might expect to see Russian land forces attempting to penetrate Ukrainian lines in the coming months in an effort to exploit Ukraine’s ammunition crisis and, as noted earlier, to take additional territory to strengthen its bargaining position later down the road.

Having examined Ukraine’s strategic ends and the challenges presented to those ends by both Ukraine’s risks and means, the ways is a fairly simple discussion. Ukraine’s limited manpower and ammunition base already limits what Ukraine can do offensively. If Russian forces in Ukraine do actually approach 670,000, and the 3:1 ratio (or 6:1 ratio) are accurate planning considerations, Kyiv would have to generate, at a minimum, the men, materiel and ammunition for a two million-soldier army to retake the Donbas, the land bridge to Crimea and Crimea. Moreover, this does not account for any counterattacks that might follow Ukrainian success or for potential insurgencies in any of those newly liberated areas.

In recent conversations on the subject, Michael Kofman and Franz-Stefan Gady made mention of this and suggested that, for the foreseeable future, Ukrainian forces are limited to defensive operations along the contact line and to small, limited objective offensives with operations rarely exceeding platoon size. 47 Hardly a way to win a war. Although Gady’s assessment of Ukraine’s position was more optimistic than Kofman’s, both analysts suggest a very challenging 2024 for Kyiv’s armed forces. Considering the strategic balance, Gady and Kofman are correct—Ukraine will be quite challenged in 2024 to do much more than defend the contact line with sufficient force to prevent Russian breakthroughs. Avdiivka is a case in point.

Avdiivka—located along the contact line in Donetsk oblast—is the conflict’s current hot spot. Russian land forces continue to use “meat assaults” to attrite Ukrainian men, materiel and equipment in the city in hopes of extending their territorial annexation and exhausting Ukraine’s ability to continue fighting. 48 After months of fighting, Russia appears to be on the cusp of claiming the city. 49 Accurate casualty numbers are challenging to identify at this point, but reports indicate that thousands of troops on both sides have died as the struggle for the city churns through men and resources. Holding the line against robust Russian attacks, like that at Avdiivka, is likely to be the maximum extent of Ukrainian operations through 2024.

Ukrainian Strategic Assessment: Summary

The most basic finding is that Ukraine has culminated and is not capable of offensive operations at the scale and duration required to retake the Donbas, the land bridge to Crimea or Crimea. What’s more, the Ukrainian armed forces will require a significant augmentation of land power to remove Russia from Ukraine’s territory. Precision strikes and air power will help in this endeavor, but Ukrainian infantry and armored forces must still move into the terrain, clear the terrain of Russian land forces, hold the terrain and then prevail against any Russian counterattacks. Therefore, onlookers should not expect any grand Ukrainian offensive through 2024. Ukraine might attempt one or two smaller scale offensives to nibble away Russian held territory, but anything larger exceeds Ukraine’s means.

If U.S. support to Ukraine remains frozen for an extended period of time, Ukraine’s ability to just hold the contact line with Russia will deteriorate further. U.S. weapons, ammunition and military equipment are vital to Ukraine’s ability to defend itself. Each day without that support adds more fragility to Ukraine’s supply network, its artillery forces and its land forces. It means increasing weaknesses proliferating through the Ukrainian armed forces and Kyiv’s inability to develop useful military strategy. In short, 2024 looks bleak for Ukraine and for its ability to meet its political-military objectives.

If, however, U.S. support to Ukraine is unlocked relatively soon, Ukraine’s ability to defend itself will still see a slight dip in capability, but it will likely rebound quickly. Nonetheless, Ukraine’s manpower challenges will still prevent it from any large-scale offensives during 2024. The influx of long-range precision strikes, air power and intelligence from the United States—and other Western nations—will help mitigate some of the personnel challenges, but certainly not completely obviate that concern. Therefore, the attritional grind of forces aligned on opposing trench networks is likely to characterize the conflict throughout 2024.

The Russo-Ukrainian War is currently in stasis. This stalemate is the result of competing strategies, one of which is focused on the retention of annexed territory—and the other on the vanquishment of a hostile force from its territory without the means to accomplish that objective. Considering the balance in relation to each state’s ends, Russia is currently winning the war (see Table 3). Russia controls significant portions of Ukrainian territory, and they are not likely to be evicted from that territory by any other means than brutal land warfare, which Ukraine cannot currently afford. What’s more, it is debatable if Ukraine will be able to generate the forces needed to liberate and hold the Donbas, the land bridge to Crimea and Crimea. It would likely take an international coalition to generate the number of troops, combat forces and strike capabilities needed to accomplish the liberation of Ukraine’s occupied territory. This international coalition materializing is extremely unlikely to happen.

As stated in the Introduction, land wars fought for territory possess different military end goals than irregular wars, counterinsurgencies and civil wars. Moreover, a strategy’s ends must be supported first by its means, and secondarily, by resource-bound ways to accomplish those ends. Thus, precision strike strategies and light-footprint approaches do not provide sufficient forces to defeat industrialized armies built to fight wars based on the physical destruction of opposing armies and occupying their territory. Robust land forces, capable of delivering overwhelming firepower and flooding into territory held by an aggressor army, are the future of war, not relics of 20th century armed conflict. This is not a feature of conflict specific to Europe, but, as John McManus notes, something that has also been proven in east Asia during U.S. operations in the Pacific theater during World War II. For instance, McManus notes that the U.S. Army employed more divisions during the invasion of The Philippines than it did during the invasion of Normandy. 50 Given the considerations that policymakers face regarding a China-Taiwan conflict scenario, it is useful to take into account McManus’ findings, as well as the realities of war laid bare in Ukraine. If China were to invade Taiwan, with the intention of annexation, then similar factors to that of the Russo-Ukrainian War are worth weighing. Large, robust land forces would be required to enter, clear and hold Taiwan.

Moreover, Russia’s operations in Ukraine illustrate that mass beats precision, and not the other way around. Precision might provide a tactical victory at a single point on the battlefield, but those victories of a finite point are not likely to deliver strategic victory. Further, denigrating Russia’s mass strategy as “stupid” misses the point. If Russia delivers strategic victory, it cannot be that illogical, regardless of how dubious the methods. Ultimately, Russia’s operations in Ukraine show that mass, especially in wars of territorial annexation, are how a state truly consolidates its gains and hedges those military victories against counterattacks.

Finally, the Russo-Ukrainian War illustrates how important it is to eliminate an enemy army to insulate one’s state from see-saw transitions between tactical victories. Clausewitz asserts that an undestroyed army always presents the possibility of returning to the battlefield and undercutting its adversary’s aims. Ukraine’s inability to eliminate Russia’s army and remove it from the battlefield in Ukraine means that Kyiv will have to continually wrestle with the Kremlin aggressively pursuing its aims in Ukraine. Ukraine’s inability to generate the size of force, coupled with the destructive warfighting capabilities needed to destroy Russia’s army in Ukraine and to occupy and hold the liberated territory, means that this war of attrition will likely grind on until either Ukraine can generate the force needed to evict Putin’s army from Ukraine, Ukraine becomes strategically exhausted and has to quit the conflict, or both parties decide to end the conflict. Regardless of the outcome, 2024 will likely continue to see Russia attempting to strategically exhaust Ukraine; meanwhile, Kyiv will do its best to maintain its position along the contact line as it tries to recruit and train the army needed to destroy Russia’s army and to liberate its territory.

Amos Fox is a PhD candidate at the University of Reading and a freelance writer and conflict scholar writing for the Association of the United States Army. His research and writing focus on the theory of war and warfare, proxy war, future armed conflict, urban warfare, armored warfare and the Russo-Ukrainian War. Amos has published in RUSI Journal and Small Wars and Insurgencies among many other publications, and he has been a guest on numerous podcasts, including RUSI’s Western Way of War , This Means War , the Dead Prussian Podcast and the Voices of War .

- “The Commander-in-Chief of Ukraine’s Armed Forces on How to Win the War,” Economist , 1 November 2023.

- Jack Watling, “The War in Ukraine is Not a Stalemate,” Foreign Affairs , 3 January 2023.

- Carl von Clausewitz, On War , trans. and eds. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 77.

- Raphael Lemkin, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress (Concord, NH: Rumford Press, 1944), 80–82.

- Guy Faulconbridge and Vladimir Soldatkin, “Putin Vows to Fight on In Ukraine Until Russia Achieves its Goals,” Reuters , 14 December 2023.

- Harriet Morris, “An Emboldened, Confident Putin Says There Will Be No Peace in Ukraine Until Russia’s Goals are Met,” Associated Press , 14 December 2023.

- Amos Fox, “Myths and Principles in the Challenges of Future War,” Association of the United States Army , Landpower Essay 23-7, 4 December 2023.

- “China’s Position on Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” US-China Economic and Security Review Commission , 31 December 2023; Robbie Gramer, “Iran Doubles Down on Arms for Russia,” Foreign Policy , 3 March 2023; Kim Tong-Hyung, “North Korea Stresses Alignment with Russia Against US and Says Putin Could Visit at an Early Date,” ABC News , 20 January 2024.

- Tong-Hyung, “North Korea Stresses Alignment with Russia”; “China’s Position on Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”; Darlene Superville, “The White House is Concerned Iran May Provide Ballistic Missiles to Russia for Use Against Ukraine,” Associated Press , 21 November 2023.

- Matthew Luxmoore and Michael Gordon, “Russia’s Army Learns from Its Mistakes in Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal , 24 September 2023.

- Margarita Konaev and Owen Daniels, “The Russians Are Getting Better,” Foreign Affairs , 6 September 2023.

- Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, Stormbreak: Fighting Through Russian Defences in Ukraine’s 2023 Offensive (London: Royal United Services Institute, 2023), 15–19.

- Bryan Frederick et. al., Escalation in the War in Ukraine: Lessons Learned and Risks for the Future (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2023), 77.

- “Bluffing or Not, Putin’s Declared Deployment of Nuclear Weapons to Belarus Raises Tensions,” Associated Press , 27 July 2023.

- “Russia’s Medvedev Warns of Nuclear Response if Ukraine Hits Missile Launch Sites,” Reuters , 11 January 2024.

- “Ukraine War: Putin Confirms First Nuclear Weapons Moved to Belarus,” BBC News , 17 June 2023.

- Steve Gutterman, “The Week in Russia: Carnage and Clampdown,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty , 19 January 2024.

- Samantha de Bendern et al., “Prigozhin May Be Dead, but Putin’s Position Remains Uncertain,” Chatham House , 24 August 2024.

- Gutterman, “The Week in Russia: Carnage and Clampdown.”

- Robert Picheta et al., “Pro-War Putin Critic Igor Girkin Sentenced to Four Years in Prison on Extremist Charges,” CNN , 25 January 2024.

- Robert Coalson, “How the Russian State Ramped Up the Suppression of Dissent in 2023: ‘It Worked in the Soviet Union, and It Works Now,’” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty , 31 December 2023.

- Ben Hodges, “Ukraine Update with Lieutenant General (Retired) Ben Hodges,” Revolution in Military Affairs [podcast], 1 January 2024.

- Sven Gunnar Simonsen, “Putin’s Leadership Style: Ethnocentric Patriotism,” Security Dialogue 31, no. 3 (2000): 377–380.

- Hodges, “The Ukraine Update.”

- Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, Meatgrinder: Russian Tactics in the Second Year of Its Invasion of Ukraine (London: Royal United Services Institute, 2023), 3–8.

- The Kyiv Post keeps a running tally of these figures and other Russian losses in a ticker across the top of their homepage: https://www.kyivpost.com .

- Christopher Miller, “Kyrylo Budanov: The Ukrainian Military Spy Chief Who ‘Likes the Darkness,’” Financial Times , 20 January 2024.

- “Ukraine in Maps: Tracking the War with Russia,” BBC News , 20 December 2023.

- Constant Meheut, “Russia Makes Small Battlefield Gains, Increasing Pressure on Ukraine,” New York Times , 22 December 2023.

- Jaroslav Lukiv, “Ukraine Seeks Extra Soldiers – President Zelenskyy,” BBC News , 19 December 2023.

- Lukiv, “Ukraine Seeks Extra Soldiers.”

- Lukiv, “Ukraine Seeks Extra Soldiers.”

- Miller, “Kyrylo Budanov: The Ukrainian Military Spy Chief Who ‘Likes the Darkness.’”

- Christopher Cavoli, “SACEUR Cavoli – Remarks at Rikskonferensen, Salen, Sweden,” NATO Transcripts , 8 February 2023.

- Olivia Olander, “Ukraine Intends to Push Russia Entirely Out, Zelenskyy Says as Counteroffensive Continues,” Politico , 11 September 2022; Guy Davies, “Zelenskyy to ABC: How Russia-Ukraine War Could End, Thoughts on US Politics and Putin’s Weakness,” ABC News , 9 July 2023.

- Angela Charlton, “Ukraine’s a Step Closer to Joining the EU. Here’s What It Means, and Why It Matters,” Associated Press , 14 December 2023.

- Visual Journalism Team, “Ukraine in Maps: Tracking the War with Russia,” BBC News , 20 December 2023.

- “Russia-Ukraine Tensions: Putin Orders Troops to Separatist Regions and Recognizes Their Independence,” New York Times , 21 February 2022.

- John Mearsheimer, “Assessing the Conventional Balance: The 3:1 Rule and Its Critics,” International Security 13, no. 4 (1989): 65–70; Michael Kofman, “Firepower Truly Matters with Michael Kofman,” Revolution in Military Affairs [podcast], 3 December 2023.

- Vladimir Isachenkov, “Putin Warns West: Moscow Has ‘Red Line’ About Ukraine, NATO,” Associated Press , 30 November 2021.

- Maria Kostenko et al., “As the War Grinds On, Ukraine Needs More Troops. Not Everyone Is Ready to Enlist,” CNN , 19 November 2023.

- Valerii Zaluzhnyi, “Modern Positional Warfare and How to Win It,” Economist , accessed 24 January 2024.

- Trevor Dupuy, Numbers, Predictions, and War: Using History to Evaluate Combat Factors and Predict the Outcome of Battles (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1979), 12.

- Army Training Publication 3-06, Urban Operations (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2022), 5-23.

- Zaluzhnyi, “Modern Positional Warfare and How to Win It.”

- Olena Harmash and Tom Balmforth, “Ukrainian Troops Face Artillery Shortages, Scale Back Some Operations – Commander,” Reuters , 18 December 2023.

- Kofman, “Firepower Truly Matters”; Franz-Stefan Gady, “A Russo-Ukrainian War Update with Franz-Stefan Gady,” Revolution in Military Affairs [podcast], 30 November 2023.

- Joseph Ataman, Frederick Pleitgen and Dara Tarasova-Markina, “Russia’s Relentless ‘Meat Assaults’ Are Wearing Down Outmanned and Outgunned Ukrainian Forces,” CNN , 23 January 2024.

- David Brennan, “Avdiivka on Edge as Russians Proclaim ‘Breakthrough,’” Newsweek , 24 January 2024.

- “Ep 106: John McManus on the U.S. Army’s Pacific War,” School of War [podcast], 16 January 2024.

The views and opinions of our authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Association of the United States Army. An article selected for publication represents research by the author(s) which, in the opinion of the Association, will contribute to the discussion of a particular defense or national security issue. These articles should not be taken to represent the views of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, the United States government, the Association of the United States Army or its members.

MIT Center for International Studies

Search form

Qualtrics block.

- Faculty + Scholars

- Affiliates + Visiting Scholars

- Research Affiliate

- Middle East and North Africa

- Global Diversity Lab

- International Education (MISTI)

- Policy Lab at the Center for International Studies

- Program on Emerging Technologies (PoET)

- Security Studies Program

- Seminar XXI

- Fellowships + Grants

- Archive of Programs + Initiatives

- Analysis + Opinion

- Research Activities

- Starr Forum

- SSP Wed Seminar

- Focus on Eurasia

- Bustani Middle East Seminar

- South Asian Politics Seminar

- MISTI Events

- MIT X TAU Webinar Series

- International Migration

- News Releases

- In the News

- Expert Guide

- War in Ukraine

You are here

Publications.

- » Analysis + Opinion

- Hypotheses on the implications of the Ukraine-Russia War

Barry Posen provides his perspective on the implications of the war in Ukraine. His analysis is available here and was published in Defense Priorities .

How will the war in Ukraine shape international politics? In principle there are two ways to address this question. The first is simply to extrapolate into the future any actions or reactions that we can observe today. The second, which is explored below, is to organize our thinking theoretically, to ask what may turn out to be the long-term effects of the major causes set in motion by the war. I organize the discussion in terms of a theory of international politics—realism, mainly structural realism. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine serves as another reminder that war remains an ever-present danger in an international system that is anarchic—ie, devoid of any central authority with the wherewithal to protect states from aggression. States must therefore prepare to defend themselves. In the heady aftermath of the liberal West’s victory over the Soviet empire, and the apparent triumph of the US-led, liberal world order, many instead believed that interstate war would become a thing of the past. States now face strong incentives to reembrace tried and tested tools of self-preservation developed in earlier times.

Full story by Barry Posen is available here: https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/hypotheses-on-the-implications-of-the-ukraine-russia-war

- A few members of the Russian Parliament speak out against the war.

- A major Ukrainian internet provider reports a cyberattack.

- After Abe, Japan tries to balance ties to the US and China

- Aid organizations say they are seeing signs of trafficking of people fleeing Ukraine.

- As Brazil’s election day approaches, fear of violence grows

- Attacking Russia in Ukraine means war

- Bolsonaro and Lula are heading to second round in Brazil election

- Boots on the ground, eyes in the sky

- CIS mourns the loss of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

- Can Russia and the West survive a nuclear crisis in Ukraine?

- Causing crisis works

- China and India need to reimagine what is possible on the border

- China's COVID protests are powerful, but they cannot challenge Xi Jinping's regime

- Do armed drones reduce terrorism? Here’s the data.

- Enhancing strategic stability in Southern Asia

- Five books that illuminate the agony and uncertainty of civilians caught in wars

- For this border crisis, Poles extend a warm welcome, unlike last time.

- Four EU countries expel dozens of Russian diplomats suspected of espionage.

- From 1994: Posen's "A Defense Concept for Ukraine"

- Here’s what Western leaders need to remember about Zelensky’s emotional appeals

- History as it happens: Invisible carnage

- How the killing of Iran’s top general squandered US leverage in Iraq today

- How the war complicates Biden's Iran diplomacy

- How the war in Ukraine could get much worse

- How to avoid a war over Taiwan

- In Poland, protesters demand a ban on road cargo traffic between the EU and Russia and Belarus.

- Kishida Becomes First Japanese PM to Attend NPT Review Conference

- Letting go of Afghanistan: Presidents Biden and Trump were right

- Let’s not grant Saudi Arabia a blank check for American support

- Major flip in Iraqi government this week: could crisis be over?

- Moqtada al-Sadr, called on his bluff, retreats for now

- More than 80,000 people have been evacuated from areas near Kyiv and the city of Sumy.

- NATO’s military presence in Eastern Europe has been building rapidly.

- NPT conference collapse, military drills further strain Japan-Russia relations

- Pentagon says Poland’s fighter jet offer is not ‘tenable.’

- Poland will propose a NATO peacekeeping mission for Ukraine at the alliance’s meeting this week.

- Putin’s misleading hairsplitting about who can join NATO

- Republicans will quit any nuclear deal with Iran, scholar predicts

- Reviving war-game scholarship at MIT

- Russia, Ukraine, and European security

- Russian forces abducted four Ukrainian journalists, a union says.

- Sanctions won't end Russia's war in Ukraine

- Science must overcome its racist legacy: Nature’s guest editors speak

- Should the United States pledge to defend Taiwan?

- The American conspiracy against Pakistan that never existed

- The Falklands War at 40: A lesson for our time

- The Russian sanctions regime and the risk of catastrophic success

- The Russo-Ukrainian war’s dangerous slide into total societal conflict

- The UN has documented at least 3,924 Ukrainian civilian deaths in the war.

- The clashing narratives that keep the US and Iran at odds

- The dawn of drone diplomacy

- The ghosts of history haunt the Russia-Ukraine crisis

- The latest round of sanctions on Russia

- The new Iraqi PM is a status quo leader, but for how long?

- The real fallout from the Mar-a-Lago search

- The rewards of rivalry: US-Chinese competition can spur climate progress

- The risk of Russian chemical weapons use

- There is no NATO open-door policy

- These disunited states

- Think COVID has stunted growth? Try 30 years of conflict.

- To prevent war and secure Ukraine, make Ukraine neutral

- US public prefers diplomacy over war on Ukraine

- Ukraine needs solutions, not endless war

- Ukraine war

- Ukraine war revives anxiety about nuclear conflict

- Ukraine: Three divergent stands, three scenarios

- Ukraine: Unleashing the rhetorical dogs of war

- Ukraine’s celebrities are dying in the war, adding an extra dimension to the nation’s shock.

- Ukraine’s implausible theories of victory

- Uncovering the strategic aspects of Sino-India ties

- Watching war in real time, one TikTok at a time

- We call on Biden to reject reckless demands for a no-fly zone

- We need to think the unthinkable about our country

- What Putin’s nuclear threats mean for the US

- What ever happened to our fear of Armageddon?

- What is America's interest in the Ukraine war?

- What to expect from Biden’s big Middle East trip

- When migrants become weapons

- Why Putin went straight for the nuclear threat

- Why the US wants a ban on ASAT missile testing

- Xi broke the social contract that helped China prosper

Publication Audits

- Starr Forum Report

Connect with CIS

Receive e-mail updates about CIS events and news.

MIT CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Building E40-400, 1 Amherst Street, Cambridge, MA 02142 Massachusetts Institute of Technology contact site credits accessibility login logout

Research Guide on the Conflict in Ukraine

Related Guides

- European Studies

- Russian & Slavic Studies

- News Sources A guide to finding newspapers, magazines, broadcasts, and other news sources at the UMN Libraries.

- Ukrainian Culture, History, Literature, & more

About this Guide

A guide to improve access to information and increase understanding of the conflict in Ukraine starting in 2014 as well as the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Links to books, article databases, and other resources are provided for more in-depth research. Note: access for many of these resources is limited to current UMN faculty, students, and staff. See this page for resources accessible by the general public (non-UMN affiiates) .

Source: Nations Online Project

Scholarly websites and webcasts

- "Russia's War on Ukraine" from Harvard University's Ukrainian Research Institute

- Posts from scholars at the University College London's Dept. of Political Science's about the 2022 war

- "Panel Discussion - Crisis in Ukraine," from Indiana University's Russian and East European Institute

- " Princeton experts discuss the Russian invasion of Ukraine," from Princeton University

News Sources for Keeping Up-to-date

- "Crisis in Ukraine" from EuroNews

- EuroTopics -- Provides information on around 600 print and online media published in 32 countries.

- BBC News on Europe -- includes coverage on Ukraine

- Russia’s war in Ukraine: complete guide in maps, video and pictures (The Guardian (UK)) -- ongoing coverage since late February 2022.

- Kyiv Post : Ukraine's oldest English-language newspaper since 1995.

- Kyiv Independent : an English-language Ukrainian news site that contains a newsfeed of events as they unfold.

- Euromaidan Press : an online English-language independent newspaper, it focuses on events concerning Ukraine and provides translations of Ukrainian news, expert analyses, and independent research.

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

- Moscow Times (Web version) -- independent news in English from Russia

Article Databases

Not sure what search terms to use? See this list of possible terms

- Academic Search Premier A great place to start your research on any topic, search multidisciplinary, scholarly research articles. This database provides access to scholarly and peer reviewed journals, popular magazines and other resources. View this tutorial to learn how to go from a general idea to a very precise set of results of journal articles and scholarly materials.

- ABSEEES Online (American Bibliography of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies) Search for journal articles and book reviews on East-Central Europe, Russia, Soviet Union and the former Soviet republics, with a vast collection of indexed sources published in the United States, Canada and some European countries.

- Historical Abstracts Find journal articles covering world history from 1450 to the present. Limited to 6 simultaneous users.

- Worldwide Political Science Abstracts The database provides citations, abstracts, and indexing of the international serials literature in political science and its complementary fields, including international relations, law, and public administration & public policy from1975 to the present.

DATABASES COVERING THE UKRAINE CONFLICT WITH REGARDS TO POLICY & FINANCE

- EMIS Professional Find company and industry information, reports, statistics, proprietary mergers and acquisitions, credit analytics, benchmark indicators and trend comparisons to help understand emerging markets.

- FitchConnect (formerly BMI Research) This link opens in a new window UMN affiliates: Please email [email protected] to request an account. Detailed reports on global industrial and municipal markets, companies and nonprofits, emphasizing emerging markets. Include extensive country risk and credit ratings, macroeconomic and financial analysis, and ESG scores. Find intra-daily alerts on economic, industrial, and political developments, business deals, multinational joint ventures, and regulatory changes.

- OECD iLibrary This link opens in a new window OECD iLibrary is the online publications portal of the 38-country Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ( https://www.oecd.org/about/members-and-partners/ ). OECD iLibrary contains thousands of e-books, chapters, tables and graphs, papers, articles, summaries, indicators, databases, and podcasts. All content will be Open Access beginning in July 2024. Content is also indexed via Policy Commons . Coverage: OECD Books, Papers and Statistics, International Energy Agency (IEA) Statistical Databases, & International Trade by Commodity Statistics

- PAIS Index (Political Science and Public Policy) PAIS (Public Affairs Information Service) searches journals and other sources on issues of political science and public policy. This includes government, politics, international relations, human rights and more.

- Policy Commons Search millions of documents on thousands of topics from the world’s leading policy experts, nonpartisan think tanks, IGOs and NGOs as well as from North American cities. Featured topics include Black Lives Matter, COVID-19, Climate Change, Gender Equity, and reports from the 500 largest cities in North America. UMN access includes both the Global Think Tanks and North American City Reports modules.

Detailed instructions on how to create a personal account are available at: https://libguides.umn.edu/capiqpro Note: Full Tunnel VPN is required to use this resource.

- Next: Background Information >>

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Ukraine invasion — explained

The roots of Russia's invasion of Ukraine go back decades and run deep. The current conflict is more than one country fighting to take over another; it is — in the words of one U.S. official — a shift in "the world order." Here are some helpful stories to make sense of it all.

How the Ukraine-Russia war is playing out differently on 3 separate fronts

A damaged statue of Soviet Union founder Vladimir Lenin in a central square in Sudzha, in the Kursk region of western Russia, on Aug. 16. Ukrainian troops say they've taken control of Sudzha, one of more than 80 towns and villages they've captured since a cross-border invasion of Russia on Aug. 6. -/AP hide caption

KYIV, Ukraine — The front line in the Russia-Ukraine war stretches for more than 600 miles. Yet roughly speaking, it breaks down into three separate fronts — in Ukraine's north, east and south — which are all playing out differently.

The latest front is just across Ukraine's northern border, where Ukrainian troops carried out a surprise invasion into Russian territory on Aug. 6, and are solidifying their positions two weeks after that breakthrough.

In eastern Ukraine, Russian forces are making steady advances and are closing in on a town that's crucial for Ukraine's military supply lines.

And in the south, in the Black Sea, Ukraine has delivered an ongoing series of powerful blows to the Russian navy and carved out a channel that allows it to export its wheat and other agricultural products.

Ukrainian forces attack a second border region in western Russia

Here's a closer look at all three.

In the north, a "buffer zone"

Ukraine said over the weekend it knocked out two bridges that cross the Seym River in western Russia, rendering them useless.

This cuts off key transportation routes that Russia could have used to send reinforcements into the Kursk region, with the intent of driving out the Ukrainian forces that have been taking and holding ground for the past two weeks.

However, it also suggests Ukraine is adopting a defensive position and is not looking to advance deeper into Russia, at least in this area.

In video remarks Sunday night, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Ukraine was trying to keep Russia away from the border region it has used to stage attacks against Ukraine.

"The creation of a buffer zone on the aggressor's territory is our operation in the Kursk region," Zelenskyy said.

In May, the Russians attempted to advance on the city Kharkiv, just 20 miles inside Ukraine. Ukraine halted the Russian ground offensive, though the city and surrounding areas still come under frequent Russian airstrikes with glide bombs that are difficult to defend against.

Ukraine's Kharkiv has withstood Russia's relentless strikes. Locals fear what's next

After lightning advances in the first few days of its incursion, Ukraine's forces inside Russia have been making only limited gains in the past week. Ukraine is still providing limited details of the operation, but Zelenskyy, military analysts and a range of media reports indicate Ukrainian forces are solidifying their positions.

Ukraine's military says it has taken more than 80 villages and towns and now controls more than 400 square miles in the Kursk region. Those figures cannot be independently confirmed.

The Ukrainians have captured, at minimum, several hundred Russian troops. Ukraine's military allowed journalists to see more than 300 Russian prisoners of war who have been moved across the border and placed in a Ukrainian prison.

Meanwhile, Russia has not yet mounted a significant counterattack. Russian officials says additional troops are on the way, and Russian television has shown columns of troops and equipment heading to Kursk.

But so far, the fighting appears limited to mostly small-scale clashes. The Russians appear to be drawing their forces from other parts of Russia — and not from front-line troops already fighting inside Ukraine.

One of Ukraine's goals with the incursion into Russia is to draw Russian forces away from the front line in eastern Ukraine, but there's no evidence this has happened on any significant scale so far.

In Russia, President Vladimir Putin has not commented on the Ukrainian invasion for the past week, and made a visit Monday to Azerbaijan .

Smoke billows above a bridge on the Seym River in Russia's western region of Kursk. Ukraine's military released the footage on Sunday, saying this was the second bridge on the river it has destroyed in recent days. The bridge could have been a route for Russia to send in reinforcements to the area, where Ukrainian troops invaded Russia on Aug. 6. Ukrainian Armed Forces/via AP hide caption

In the east, Russian troops close in on a key town

Eastern Ukraine is still the main battlefront. The Russians claimed the capture of another small town Monday and are now less than 10 miles from the town of Pokrovsk.

Pokrovsk is a transportation hub that Ukraine uses to send troops and supplies to its front-line positions in the east. If the Russians take the town, Ukraine will have a tougher time supporting forces that are already outnumbered and outgunned.

For the past several days, Ukrainian officials have been urging civilians in Pokrovsk to evacuate to safer areas.

"With every passing day there is less and less time to collect personal belongings and leave for safer regions," local officials in Pokrovsk said in a recent statement.

Throughout the war, Ukraine has had a shortage of troops in the east. By sending thousands of its troops into Russia, Ukraine could be even more vulnerable in areas where it's struggling to stop Russian advances.

Weapons packages from the U.S. and European states are arriving, but not fast enough, according to Zelenskyy.

"We need to speed up the supply from our partners," Zelenskyy said in his Sunday night remarks. "There are no holidays in war. We need solutions, we need timely logistics of announced [weapons] packages. I am especially appealing now to the United States, Great Britain, and France."

In the Black Sea, Ukraine creates an export channel

One of Ukraine's biggest successes over the past year has been driving back the Russian navy in the Black Sea and establishing a shipping channel so it can again export grain and other agricultural products to world markets.

Russia dominated the Black Sea and blocked Ukrainian exports after its full-scale invasion in 2022. A subsequent deal that allowed limited Ukrainian exports fell apart last summer.

But Ukraine has found its own solution. Ukraine has fired missiles from land, hitting Russian ships that ventured too near the coast, and Ukraine also has developed its own sea drones to attack Russian vessels.

Retired U.S. Adm. James Foggo , who worked alongside the Ukrainian Navy in the Black Sea a decade ago, said the sea drones point to Ukraine's naval ingenuity.

"They're jet skis with explosives packed on them," said Foggo, who now heads the Center for Maritime Strategy in Arlington, Va. "They have some kind of remote control from some kind of command center. I don't know what kind of radio control they have on these things, but they're pretty darn good."

The Ukrainian missile and sea drone attacks have forced Russian ships to retreat from the western half of the Black Sea, opening the channel along the western coast for Ukrainian exports.

Ukraine announced last week that it's been one year since this option became available, and 2,300 cargo ships have used the route, an average of more than six a day. Ukraine also says it's approaching its prewar exports of wheat and other farm products at around 5 million tons a month.

Foggo called this a remarkable achievement.

"The Ukrainians, without a floating navy, have been able to destroy about one-third of the [Russian] Black Sea fleet," or about 25 ships and submarines. "That's absolutely amazing," he said.

- Ukraine military

- Russia-Ukraine

- Russia-Ukraine war

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

International Relations Theory and the Ukrainian War

Drawing on my qualitative and quantitative research I show that the motives for war have changed in the course of the last four centuries, and that the causes of war and the responses of others to the use of force are shaped by society. Leaders who start wars rarely behave with the substantive and instrumental rationality assumed by realist and rationalist approaches. For this reason, historically they lose more than half wars than they start. After 1945, the frequency of failure rises to over 80 percent. Rationalists allow for miscalculation but attribute it to lack of information. In most wars, information was available beforehand that indicated, or certainly suggested, that the venture would not succeed militarily or fail to achieve its political goals. The war in Ukraine is a case in point.

Modernity is a social construct, but a very useful one. Today’s social world is very different in important ways for that of earlier centuries. Among the most important theorized differences are the deepening of the inner self; a nearly universal quest for identity and self-expression; the emergence of equality as the most valued principle of justice; the breakdown of class barriers, and with it, the greater freedom of individuals from social constraints; a greater emphasis on wealth, and the claiming of status by its display ( Seigel 2005 ; Lebow 2012 ). International relations theories are to varying degrees anchored in this new social reality. The liberal, Marxist, and constructivist paradigms are rooted in modernity, but in different understandings of it. Realism, by contrast, relies on pre-modern and modern understandings of social relations, and makes little to no effort to distinguish between them. Modern framings of realism generally posit security as the goal of states, treat actors for the most part as substantively and instrumentally rational, and at the same time deny the possibility of progress. As did the ancients, they see order and decline as a repetitive cycle from which there is no escape. I argue that such an approach tells us next to nothing about the institution of war or about the causes of individual wars.

Wars between or among multiple great powers.