Center for Teaching

Student assessment in teaching and learning.

Much scholarship has focused on the importance of student assessment in teaching and learning in higher education. Student assessment is a critical aspect of the teaching and learning process. Whether teaching at the undergraduate or graduate level, it is important for instructors to strategically evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching by measuring the extent to which students in the classroom are learning the course material.

This teaching guide addresses the following: 1) defines student assessment and why it is important, 2) identifies the forms and purposes of student assessment in the teaching and learning process, 3) discusses methods in student assessment, and 4) makes an important distinction between assessment and grading., what is student assessment and why is it important.

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning.” (Stassen et al., 2001, pg. 5) This definition captures the essential task of student assessment in the teaching and learning process. Student assessment enables instructors to measure the effectiveness of their teaching by linking student performance to specific learning objectives. As a result, teachers are able to institutionalize effective teaching choices and revise ineffective ones in their pedagogy.

The measurement of student learning through assessment is important because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting course learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction—what they call “Backward Design”—that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggens and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course learning objectives. They argue that assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred in the classroom. Assessment is so vital in their pedagogical design that their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings.” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, pg. 18)

For more on Wiggins and McTighe’s “Backward Design” model, see our Understanding by Design teaching guide.

Student assessment also buttresses critical reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, contends that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students. Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the development of rationale for teaching practices. According to Brookfield, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment.” (Brookfield, 1995, pg. 17) Student assessment, then, not only enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching, but is also useful in developing the rationale for pedagogical choices in the classroom.

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

There are generally two forms of student assessment that are most frequently discussed in the scholarship of teaching and learning. The first, summative assessment , is assessment that is implemented at the end of the course of study. Its primary purpose is to produce a measure that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful to provide information about patterns of student achievement, it does so without providing the opportunity for students to reflect on and demonstrate growth in identified areas for improvement and does not provide an avenue for the instructor to modify teaching strategy during the teaching and learning process. (Maki, 2002) Examples of summative assessment include comprehensive final exams or papers.

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning over the course of time. Its fundamental purpose is to estimate students’ level of achievement in order to enhance student learning during the learning process. By interpreting students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies.” (Maki, 2002, pg. 11) Pat Hutchings refers to this form of assessment as assessment behind outcomes. She states, “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, pg. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes course work—where students receive feedback that identifies strengths, weaknesses, and other things to keep in mind for future assignments—discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves. (Brown and Knight, 1994)

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed in the next section) can either be summative or formative in orientation depending on how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in their book, Assessing Learners in Higher Education, caution against a conflation of the purposes of assessment its method. “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback.” (Brown and Knight, 1994, pg. 17) If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, he or she may fall into the trap of using the method without taking the requisite time to review the implications of the feedback with students. In such cases, the method in question effectively functions as a form of summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions. (Brown and Knight, 1994) Indeed, feedback and discussion is the critical factor that distinguishes between formative and summative assessment.

Methods in Student Assessment

Below are a few common methods of assessment identified by Brown and Knight that can be implemented in the classroom. [1] It should be noted that these methods work best when learning objectives have been identified, shared, and clearly articulated to students.

Self-Assessment

The goal of implementing self-assessment in a course is to enable students to develop their own judgement. In self-assessment students are expected to assess both process and product of their learning. While the assessment of the product is often the task of the instructor, implementing student assessment in the classroom encourages students to evaluate their own work as well as the process that led them to the final outcome. Moreover, self-assessment facilitates a sense of ownership of one’s learning and can lead to greater investment by the student. It enables students to develop transferable skills in other areas of learning that involve group projects and teamwork, critical thinking and problem-solving, as well as leadership roles in the teaching and learning process.

Things to Keep in Mind about Self-Assessment

- Self-assessment is different from self-grading. According to Brown and Knight, “Self-assessment involves the use of evaluative processes in which judgement is involved, where self-grading is the marking of one’s own work against a set of criteria and potential outcomes provided by a third person, usually the [instructor].” (Pg. 52)

- Students may initially resist attempts to involve them in the assessment process. This is usually due to insecurities or lack of confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate their own work. Brown and Knight note, however, that when students are asked to evaluate their work, frequently student-determined outcomes are very similar to those of instructors, particularly when the criteria and expectations have been made explicit in advance.

- Methods of self-assessment vary widely and can be as eclectic as the instructor. Common forms of self-assessment include the portfolio, reflection logs, instructor-student interviews, learner diaries and dialog journals, and the like.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is a type of collaborative learning technique where students evaluate the work of their peers and have their own evaluated by peers. This dimension of assessment is significantly grounded in theoretical approaches to active learning and adult learning . Like self-assessment, peer assessment gives learners ownership of learning and focuses on the process of learning as students are able to “share with one another the experiences that they have undertaken.” (Brown and Knight, 1994, pg. 52)

Things to Keep in Mind about Peer Assessment

- Students can use peer assessment as a tactic of antagonism or conflict with other students by giving unmerited low evaluations. Conversely, students can also provide overly favorable evaluations of their friends.

- Students can occasionally apply unsophisticated judgements to their peers. For example, students who are boisterous and loquacious may receive higher grades than those who are quieter, reserved, and shy.

- Instructors should implement systems of evaluation in order to ensure valid peer assessment is based on evidence and identifiable criteria .

According to Euan S. Henderson, essays make two important contributions to learning and assessment: the development of skills and the cultivation of a learning style. (Henderson, 1980) Essays are a common form of writing assignment in courses and can be either a summative or formative form of assessment depending on how the instructor utilizes them in the classroom.

Things to Keep in Mind about Essays

- A common challenge of the essay is that students can use them simply to regurgitate rather than analyze and synthesize information to make arguments.

- Instructors commonly assume that students know how to write essays and can encounter disappointment or frustration when they discover that this is not the case for some students. For this reason, it is important for instructors to make their expectations clear and be prepared to assist or expose students to resources that will enhance their writing skills.

Exams and time-constrained, individual assessment

Examinations have traditionally been viewed as a gold standard of assessment in education, particularly in university settings. Like essays they can be summative or formative forms of assessment.

Things to Keep in Mind about Exams

- Exams can make significant demands on students’ factual knowledge and can have the side-effect of encouraging cramming and surface learning. On the other hand, they can also facilitate student demonstration of deep learning if essay questions or topics are appropriately selected. Different formats include in-class tests, open-book, take-home exams and the like.

- In the process of designing an exam, instructors should consider the following questions. What are the learning objectives that the exam seeks to evaluate? Have students been adequately prepared to meet exam expectations? What are the skills and abilities that students need to do well? How will this exam be utilized to enhance the student learning process?

As Brown and Knight assert, utilizing multiple methods of assessment, including more than one assessor, improves the reliability of data. However, a primary challenge to the multiple methods approach is how to weigh the scores produced by multiple methods of assessment. When particular methods produce higher range of marks than others, instructors can potentially misinterpret their assessment of overall student performance. When multiple methods produce different messages about the same student, instructors should be mindful that the methods are likely assessing different forms of achievement. (Brown and Knight, 1994).

For additional methods of assessment not listed here, see “Assessment on the Page” and “Assessment Off the Page” in Assessing Learners in Higher Education .

In addition to the various methods of assessment listed above, classroom assessment techniques also provide a useful way to evaluate student understanding of course material in the teaching and learning process. For more on these, see our Classroom Assessment Techniques teaching guide.

Assessment is More than Grading

Instructors often conflate assessment with grading. This is a mistake. It must be understood that student assessment is more than just grading. Remember that assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to instructors and students about student achievement. Traditional grading on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. does not provide the level of detailed and specific information essential to link student performance with improvement. “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest.” (Stassen et al., 2001, pg. 6) Instructors, therefore, must always remember that grading is an aspect of student assessment but does not constitute its totality.

Teaching Guides Related to Student Assessment

Below is a list of other CFT teaching guides that supplement this one. They include:

- Active Learning

- An Introduction to Lecturing

- Beyond the Essay: Making Student Thinking Visible in the Humanities

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- How People Learn

- Syllabus Construction

References and Additional Resources

This teaching guide draws upon a number of resources listed below. These sources should prove useful for instructors seeking to enhance their pedagogy and effectiveness as teachers.

Angelo, Thomas A., and K. Patricia Cross. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers . 2 nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. Print.

Brookfield, Stephen D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. Print.

Brown, Sally, and Peter Knight. Assessing Learners in Higher Education . 1 edition. London ; Philadelphia: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Cameron, Jeanne et al. “Assessment as Critical Praxis: A Community College Experience.” Teaching Sociology 30.4 (2002): 414–429. JSTOR . Web.

Gibbs, Graham and Claire Simpson. “Conditions under which Assessment Supports Student Learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (2004): 3-31.

Henderson, Euan S. “The Essay in Continuous Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 5.2 (1980): 197–203. Taylor and Francis+NEJM . Web.

Maki, Peggy L. “Developing an Assessment Plan to Learn about Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 28.1 (2002): 8–13. ScienceDirect . Web. The Journal of Academic Librarianship.

Sharkey, Stephen, and William S. Johnson. Assessing Undergraduate Learning in Sociology . ASA Teaching Resource Center, 1992. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding By Design . 2nd Expanded edition. Alexandria, VA: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2005. Print.

[1] Brown and Night discuss the first two in their chapter entitled “Dimensions of Assessment.” However, because this chapter begins the second part of the book that outlines assessment methods, I have collapsed the two under the category of methods for the purposes of continuity.

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

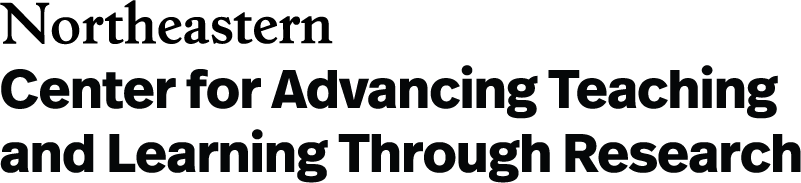

Course Assessment

Course-level assessment is a process of systematically examining and refining the fit between the course activities and what students should know at the end of the course.

Conducting a course-level assessment involves considering whether all aspects of the course align with each other and whether they guide students to achieve the desired learning outcomes.

“Assessment” refers to a variety of processes for gathering, analyzing, and using information about student learning to support instructional decision-making, with the goal of improving student learning. Most instructors already engage in assessment processes all the time, ranging from informal (“hmm, there are many confused faces right now- I should stop for questions”) to formal (“nearly half the class got this quiz question wrong- I should revisit this concept”).

When approached in a formalized way, course-level assessment is a process of systematically examining and refining the fit between the course activities and what students should know at the end of the course. Conducting a course-level assessment involves considering whether all aspects of the course align with each other and whether they guide students to achieve the desired learning outcomes . Course-level assessment can be a practical process embedded within course design and teaching, that provides substantial benefits to instructors and students.

Over time, as the process is followed iteratively over several semesters, it can help instructors find a variety of pathways to designing more equitable courses in which more learners develop greater expertise in the skills and knowledge of greatest importance to the discipline or topic of the course.

Differentiating Grading from Assessment

“Assessment” is sometimes used colloquially to mean “grading,” but there are distinctions between the two. Grading is a process of evaluating individual student learning for the purposes of characterizing that student’s level of success at a particular task (or the entire course). The grade of an assignment may provide feedback to students on which concepts or skills they have mastered, which can guide them to revise their study approach, but may not be used by the instructor to decide how subsequent class sessions will be spent. Similarly, a student’s grade in a course might convey to other instructors in the curriculum or prospective employers the level of mastery that the student has demonstrated during that semester, but need not suggest changes to the design of the course as a whole for future iterations.

In contrast to grading, assessment practices focus on determining how many students achieved which learning course outcomes, and to what level of mastery, for the purpose of helping the instructor revise subsequent lessons or the course as a whole for subsequent terms. Since final course grades may include participation points, and aggregate student mastery of all course learning objectives into a single measure, they rarely give clarity on what elements of the course have been most or least successful in achieving the instructor’s goals. Differentiating assessment from grading allows instructors to plot a clear course forward toward making the changes that will have the greatest impact in the areas they define as being most important, based on the results of the assessment.

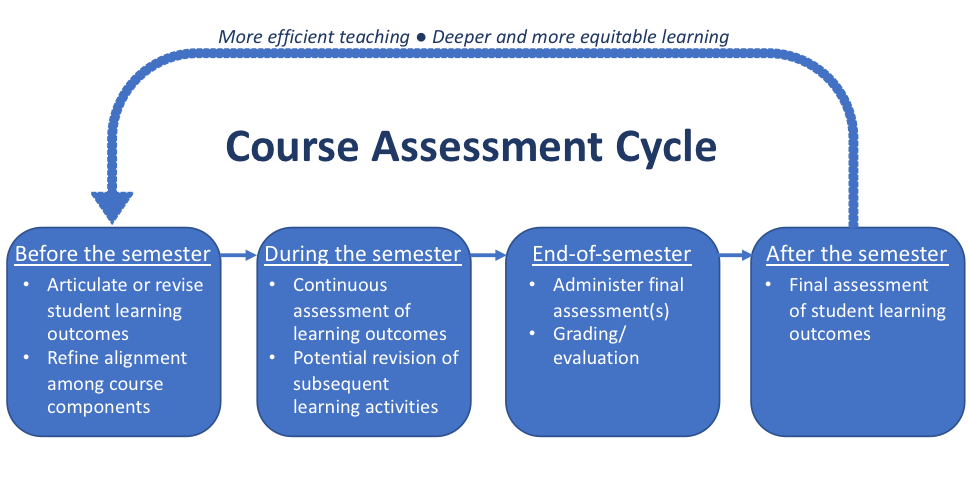

Course learning outcomes are measurable statements that describe what students should be able to do by the end of a course . Let’s parse this statement into its three component parts: student-centered, measurable, and course-level.

Student-Centered

First, learning outcomes should focus on what students will be able to do, not what the course will do. For example:

- “Introduces the fundamental ideas of computing and the principles of programming” says what a course is intended to accomplish. This is perfectly appropriate for a course description but is not a learning outcome.

- A related student learning outcome might read, “ Explain the fundamental ideas of computing and identify the principles of programming.”

Second, learning outcomes are measurable , which means that you can observe the student performing the skill or task and determine the degree to which they have done so. This does not need to be measured in quantitative terms—student learning can be observed in the characteristics of presentations, essays, projects, and many other student products created in a course (discussed more in the section on rubrics below).

To be measurable, learning outcomes should not include words like understand , learn , and appreciate , because these qualities occur within the student’s mind and are not observable. Rather, ask yourself, “What would a student be doing if they understand, have learned, or appreciate?” For example:

- “Learners should understand US political ideologies regarding social and environmental issues,” is not observable.

- “Learners should be able to compare and contrast U.S. political ideologies regarding social and environmental issues,” is observable.

Course-Level

Finally, learning outcomes for course-level assessment focus on the knowledge and skills that learners will take away from a course as a whole. Though the final project, essay, or other assessment that will be used to measure student learning may match the outcome well, the learning outcome should articulate the overarching takeaway from the course, rather than describing the assignment. For example:

- “Identify learning principles and theories in real-world situations” is a learning outcome that describes skills learners will use beyond the course.

- “Develop a case study in which you document a learner in a real-world setting” describes a course assignment aligned with that outcome but is not a learning outcome itself.

Identify and Prioritize Your Higher-Order End Goals

Course-level learning outcomes articulate the big-picture takeaways of the course, providing context and purpose for day-to-day learning. To keep the workload of course assessment manageable, focus on no more than 5-10 learning outcomes per course (McCourt, 2007). This limit is helpful because each of these course-level learning objectives will be carefully assessed at the end of the term and used to guide iterative revision of the course in future semesters.

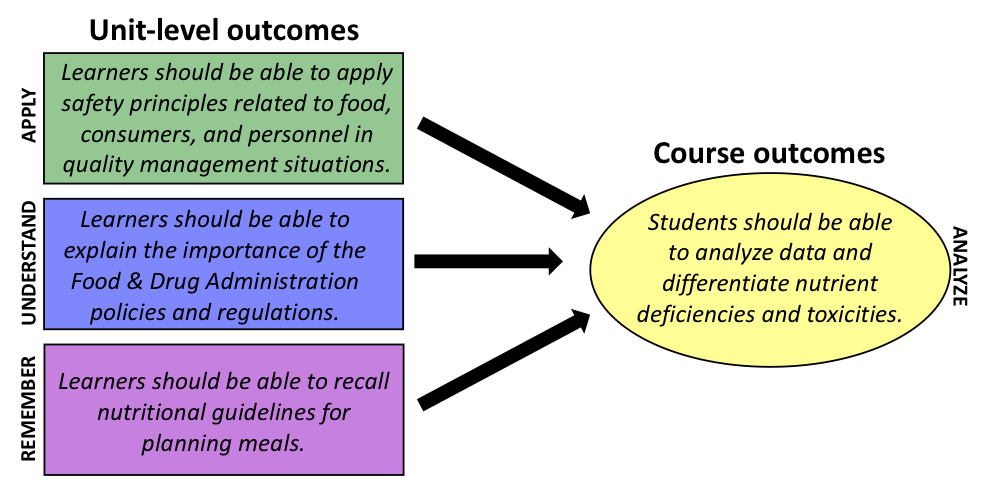

This is not meant to suggest that students will only learn 5-10 skills or concepts during the term. Multiple shorter-term and lower-level learning objectives are very helpful to guide student learning at the unit, week, or even class session scale (Felder & Brent, 2016). These shorter-term objectives build toward or serve as components of the course-level objectives.

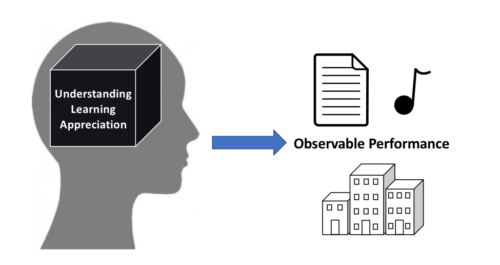

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) is a helpful tool for deciding which of your objectives are course-level, which may be unit-to class-level objectives, and how they fit together. This taxonomy organizes action verbs by complexity of thinking, resulting in the following categories:

Download a list of sample learning outcomes from a variety of disciplines .

Typically, objectives at the higher end of the spectrum (“analyzing,” “evaluating,” or “creating”) are ideal course-level learning outcomes, while those at the lower end of the spectrum (“remembering,” “understanding,” or “applying”) are component parts and day, week, or unit-level outcomes. Lower-level outcomes that do not contribute substantially to students’ ability to achieve the higher-level objectives may fit better in a different course in the curriculum.

Consider Involving Your Learners

Depending on the course and the flexibility of the course structure and/or progression, some educators spend the first day of the course working with learners to craft or edit learning outcomes together. This practice of giving learners an informed voice may lead to increased motivation and ownership of learning.

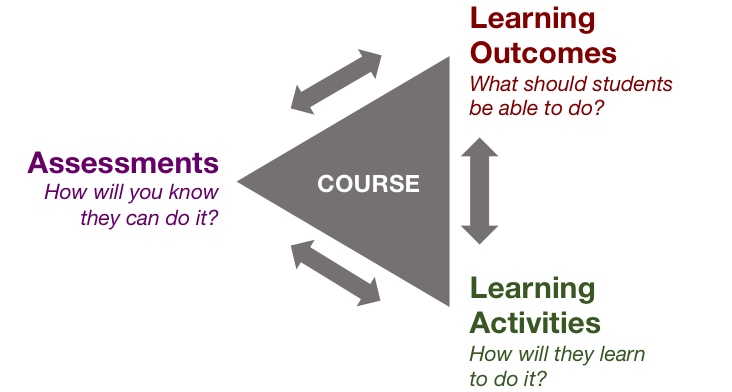

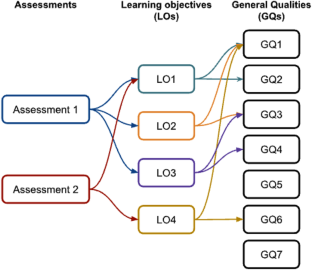

Alignment, where all components work together to bolster specific student learning outcomes, occurs at multiple levels. At the course level, assignments or activities within the course are aligned with the daily or unit-level learning outcomes, which in turn are aligned with the course-level objectives. At the next level, the learning outcomes of each course in a curriculum contribute directly and strategically to programmatic learning outcomes.

Alignment Within the Course

Since learning outcomes are statements about key learning takeaways, they can be used to focus the assignments, activities, and content of the course (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Biggs & Tang (2011) note that, “In a constructively aligned system, all components… support each other, so the learner is enveloped within a supportive learning system.”

For example, for the learning outcome, “learners should be able to collaborate effectively on a team to create a marketing campaign for a product,” the course should: (1) intentionally teach learners effective ways to collaborate on a team and how to create a marketing campaign; (2) include activities that allow learners to practice and progress in their skillsets for collaboration and creation of marketing campaigns; and (3) have assessments that provide feedback to the learners on the extent that they are meeting these learning outcomes.

Alignment With Program

When developing your course learning outcomes, consider how the course contributes to your program’s mission/goals (especially if such decisions have not already been made at the programmatic level). If course learning outcomes are set at the programmatic level, familiarize yourself with possible program sequences to understand the knowledge and skills learners are bringing into your course and the level and type of mastery they may need for future courses and experiences. Explicitly sharing your understanding of this alignment with learners may help motivate them and provide more context, significance, and/or impact for their learning (Cuevas, Matveevm, & Miller, 2010).

If relevant, you will also want to ensure that a course with NUpath attributes addresses the associated outcomes . Similarly, for undergraduate or graduate courses that meet requirements set by external evaluators specific to the discipline or field, reviewing and assessing these outcomes is often a requirement for continuing accreditation.

See our program-level assessment guide for more information.

Transparency

Sharing course learning outcomes with learners makes the benchmarks for learning explicit and helps learners make connections across different elements within the course (Cuevas & Mativeev, 2010). Consider including course learning outcomes in your syllabus , so learners know what is expected of them by the end of a course and can refer to the outcomes as the term progresses. When educators refer to learning outcomes during the course before introducing new concepts or assignments, learners receive the message that the outcomes are important and are more likely to see the connections between the outcomes and course activities.

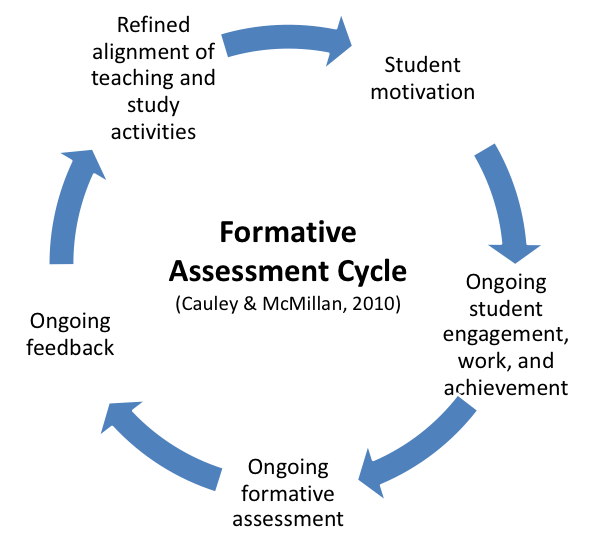

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment practices are brief, often low-stakes (minimal grade value) assignments administered during the semester to give the instructor insight into student progress toward one or more course-level learning objectives (or the day-to unit-level objectives that stair-step toward the course objectives). Common formative assessment techniques include classroom discussions , just-in-time quizzes or polls , concept maps , and informal writing techniques like minute papers or “muddiest points,” among many others (Angelo & Cross, 1993).

Refining Alignment During the Semester

While it requires a bit of flexibility built into the syllabus, student-centered courses often use the results of formative assessments in real time to revise upcoming learning activities. If students are struggling with a particular outcome, extra time might be devoted to related practice. Alternatively, if students demonstrate accomplishment of a particular outcome early in the related unit, the instructor might choose to skip activities planned to teach that outcome and jump ahead to activities related to an outcome that builds upon the first one.

Supporting Student Motivation and Engagement

Formative assessment and subsequent refinements to alignment that support student learning can be transformative for student motivation and engagement in the course, with the greatest benefits likely for novices and students worried about their ability to successfully accomplish the course outcomes, such as those impacted by stereotype threat (Steele, 2010). Take the example below, in which an instructor who sees that students are struggling decides to dedicate more time and learning activities to that outcome. If that instructor were to instead move on to instruction and activities that built upon the prior learning objective, students who did not reach the prior objective would become increasingly lost, likely recognize that their efforts at learning the new content or skill were not helping them succeed, and potentially disengage from the course as a whole.

Artifacts for Summative Assessment

To determine the degree to which students have accomplished the course learning outcomes, instructors often assign some form of project , essay, presentation, portfolio, renewable assignment , or other cumulative final. The final product of these activities could serve as the “artifact” that is assessed. In this context, alignment is particularly critical—if this assignment does not adequately guide students to demonstrate their achievement of the learning outcomes, the instructor will not have concrete information to guide course design for future semesters. To keep assessment manageable, aim to design a single final assignment that create the space for students to demonstrate their performance on multiple (if not all) course learning outcomes.

Since not all courses are designed with a final assignment that allows students to demonstrate their highest level of achievement of all course learning outcomes, the assessment processes could use the course assignment that represents the highest level of achievement that students had an opportunity to demonstrate during the term. However, some learning objectives that do not come into play during the final may be better categorized as unit-level, rather than course-level, objectives.

Direct vs. Indirect Measures of Student Learning

Some instructors also use surveys, interviews, or other methods that ask learners whether and how they believe they have achieved the learning outcomes. This type of “indirect evidence” can provide valuable information about how learners understand their progress but does not directly measure students’ learning. In fact, novices commonly have difficulty accurately evaluating their own learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). For this reason, indirect evidence of student learning (on its own) is not considered sufficient for summative assessment.

Together, direct and indirect evidence of student learning can help an instructor determine whether to bolster student practice in certain areas or whether to simply focus on increasing transparency about when students are working toward which learning outcome.

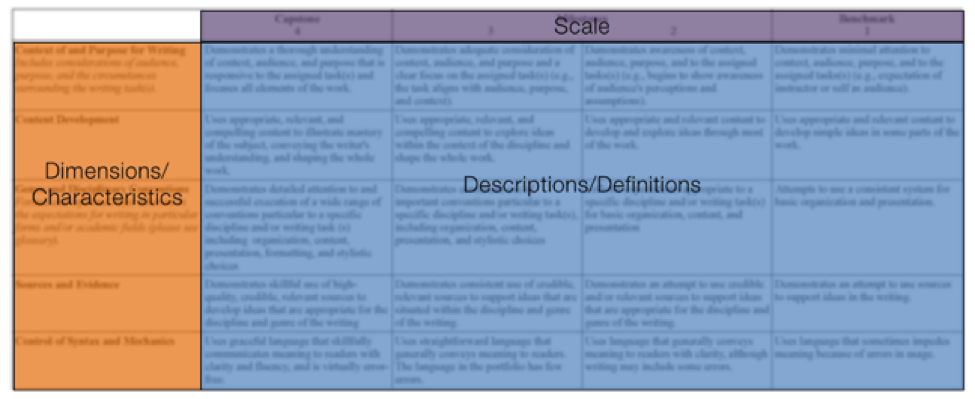

Creating and Assessing Student Work with Analytic Rubrics

One tool for assessing student work is analytic rubrics (shown below) which are matrices of characteristics and descriptions of what it might look like for student products to demonstrate these characteristics at different levels of mastery. Analytic rubrics are commonly recommended for assessment purposes, since they provide more detailed feedback to guide course design in more meaningful ways than holistic rubrics. Pre-existing analytic rubrics such as the AAC&U VALUE Rubrics can be tailored to fit your course or program, or you can develop an outcome-specific rubric yourself (Moskal, 2000 is a useful reference, or contact CATLR for a one-on-one consultation). The process of refining a rubric often involves multiple iterations of applying the rubric to student work and identifying the ways in which it captures or does not capture the characteristics representing the outcome.

Summative assessment results can inform changes to any of the course components for subsequent terms. If students have underperformed on a particular course learning objective, the instructor might choose to revise the related assignments or provide additional practice opportunities related to that objective, and formative assessments might be revised or implemented to test whether those new learning activities are producing better results. If the final assessment does not provide sufficient information about student performance on a certain outcome, the instructor might revise the assessment guidelines or even implement a different assessment that is more aligned to the outcome. Finally, if an instructor notices during the assessment process that an important outcome has not been articulated, or would be more clearly stated a different way, that instructor might revise the objectives themselves.

For assistance at any stage of the course assessment cycle, contact CATLR for a one-on-one or group consultation.

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching . San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives . New York, NY: Longman.

Bembenutty, H. (2011). Self-regulation of learning in postsecondary education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning , 126 , 3-8. doi: 10.1002/tl.439

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University . Maidenhead, England: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Cauley, K. M., & McMillan, J. H. (2010). Formative assessment techniques to support student motivation and achievement. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas , 83 (1), 1-6. doi: 10.1080/00098650903267784

Cuevas, N. M., Matveev, A. G., & Miller, K. O. (2010). Mapping general education outcomes in the major: Intentionality and transparency. Peer Review , 12 (1), 10-15.

Felder, R. M., & Brent, R. (2016). Teaching and learning STEM: A practical guide . San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice , 41 (4), 212-218. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

McCourt, Millis, B. J., (2007). Writing and Assessing Course-Level Student Learning Outcomes . Office of Planning and Assessment at the Texas Tech University.

Moskal, B. M. (2000). Scoring rubrics: What, when and how? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 7 (3).

Setting Learning Outcomes . (2012). Center for Teaching Excellence at Cornell University. Retrieved from https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/designing-your-course/setting-learning-outcomes .

Steele, C. M. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do . New York, NY: WW Norton & Company, Inc.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (Expanded) . Alexandria, US: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

- Office of Curriculum, Assessment and Teaching Transformation >

- Teaching at UB >

- Course Development >

- Design Your Course >

Designing Assessments

Determining how and when students have reached course learning outcomes.

On this page:

The importance of assessment.

Assessments in education measure student achievement. These may take the form traditional assessments such as exams, or quizzes, but may also be part of learning activities such as group projects or presentations.

While assessments may take many forms, they also are used for a variety of purposes. They may

- Guide instruction

- Determine if reteaching, remediating or enriching is needed

- Identify strengths and weaknesses

- Determine gaps in content knowledge or understanding

- Confirm students’ understanding of content

- Promote self-regulating strategies

- Determine if learning outcomes have been achieved

- Collect data to record and analyze

- Evaluate course and teaching effectiveness

While all aspects of course design are important, your choice of assessment Influences what your students will primarily focus on.

For example, if you assign students to watch videos but do not assess understanding or knowledge of the videos, students may be more likely to skip the task. If your exams only focus on memorizing content and not thinking critically, you will find that students are only memorizing material instead of spending time contemplating the meaning of the subject matter, regardless of whether you attempt to motivate them to think about the subject.

Overall, your choice of assessment will tell students what you value in your course. Assessment focuses students on what they need to achieve to succeed in the class, and if you want students to achieve the learning outcomes you have created, then your assessments need to align with them.

The Assessment Cycle

Assessment does not occur only at the end of units or courses. To adjust teaching and learning, assessment should occur regularly throughout the course. The following diagram is an example of how assessment might occur at several levels.

The assessment cycle

This cycle might occur:

- During a single lesson when students tell an instructor that they are having difficulty with a topic.

- At the unit level where a quiz or exam might inform whether additional material needs to be included in the next unit.

- At the course level where a final exam might indicate which units will need more instructional time the next time the course is taught.

In many of the above instances learning outcomes may not change, but assessment results will instead directly influence further instruction. For example, during a lecture a quick formative assessment such as a poll may make it clear that instruction was unclear, and further examples are needed.

Assessment Considerations

There are several types of assessment to consider in your course which fit within the assessment cycle. The two main assessments used during a course are formative and summative assessment. It is easier to understand each by comparing them.

| Formative | Summative | |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment for Learning | Assessment of Learning | |

| Purpose | Improve learning | Measure attainment |

| When | While learning is in progress | End of learning |

| Focused on | Learning process and learning progress | Products of learning |

| Who | Collaborative | Instructor-directed |

| Use | Provide feedback and adjust lesson | Final evaluation |

An often-used quote that helps illustrate the difference between these purposes is:

“When the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative. When the guests taste the soup, that’s summative.” Robert E. Stake

It is important to note, however, that assessments may often serve both purposes. For example, a low-stakes quiz may be used to inform students of their current progress, and an instructor may alter instruction to spend more time on a topic if student scores warrant it. Additionally, activities like research papers or presentations graded on a rubric contain both the learning activity as well as the assessment. If students complete sections or drafts of the paper and receive grades or feedback along the way, this activity also serves as a formative assessment for learning while serving as a summative assessment upon completion.

Used to determine student understanding and misconceptions before your course or unit begin to determine background knowledge on upcoming topics.

Used to determine whether students understood course content, as well as what instruction or active learning worked well. It can also determine misconceptions and questions students may still have. Formative assessments are used to inform further instruction.

Used to determine student learning at the end of the learning process. These forms of assessments usually result in a weighted grade.

A set of criteria used to evaluate student work that improves efficiency, accuracy and objectivity while simultaneously providing feedback.

Best Practices

Considerations.

For assessments to accurately measure outcomes and to provide optimal feedback to students, the following should influence assessment choice and design:

Learning outcomes

- Cognitive complexity

- Options for expression

- Course and Class

Assessment and grading

- Weight of assessment

- Time for grading and feedback

- Delivery modes

Course level

- Prerequisites and post learning

- Time and length of course

- Practice opportunities

- Accessibility and accommodations

Provide Ongoing and Varied Methods

Because learning outcomes are unique, the types of knowledge and skills that demonstrate achievement of these outcomes will differ. Therefore, assessments will need to vary to capture this achievement. Consider using:

- Evaluation of participation and engagement

- Opportunities for feedback

- Demonstrable learner progress

- Opportunities to test and apply their knowledge

- Different types of evidence: The following resource summarizes the different types of evidence to determine progress and how this evidence can be collected.

Question Types

There are several types of questions that you can use to assess student achievement. The following links explain question types and how to design high-quality multiple-choice questions.

Overview of the different types of questions you can use for assessments.

Overview of how to access, add and use all the question types available in Brightspace to design an assessment.

Overview of how to construct high-quality multiple-choice test questions.

At the beginning of choosing assessments for your course, you should start by reviewing the learning outcomes and then matching assessments to them. Assessments should align to the cognitive complexity (see Bloom’s Taxonomy ) or type of learning (see Fink’s Taxonomy ) of course learning outcomes.

For example, if your course outcomes expect students to be able to memorize or understand course content, exams with multiple choice questions may accurately assess these outcomes. If your outcome expects students to be able to create an original product, then a multiple choice question would not measure an innovative creation.

Instead, a project, graded with a rubric, may best assess this.

If an assessment does not map onto an outcome, you should ask whether you are missing a course learning outcome you care about and, if not, whether your assessment is necessary. Further, you may need to adapt the assessment itself or even your choice in assessment to align with the learning outcome.

The accompanying chart is helpful in choosing and reviewing your assessments as you create them. You may find as you go that a course outcome might change as you determine how you will be able to assess it or if the scope of the learning outcome is too large for the time needed for the assessment.

If you find most outcomes are assessed using quizzes and exams, consider alternative methods of assessment.

A colorized wheel illustrating how various assessments (60+) map onto the levels of learning outlined by Bloom.

Guide to developing formative assessment questions in alignment with Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Applying Assessments to Your Course

- On your course design template , fill in the assessment column.

- Consider a variety of assessments (e.g., formative and summative assessments).

- Ensure assessments align to your course’s learning outcomes.

Now that you have chosen assessments to measure learning outcomes the next step is to consider methods of teaching.

If you would like to begin building some of your assessments, see:

Additional resources

The first step is deciding what you want your students to be able to do by the end of your course.

Examples for aligning assessments to the cognitive complexity of learning outcomes.

How does the assessment(s) align with your learning outcomes?

Rethinking educational assessments: the matrimony of exams and coursework

Standardised tests have been cemented in education systems across the globe, but whether or not they are a better assessment of students’ ability compared to coursework still divides opinions.

Proponents of exam assessments argue that despite being stressful, exams are beneficial for many reasons, such as:

- Provides motivation to study;

- Results are a good measure of the student’s work and understanding (and not anyone else’s); and

- They are a fair way of assessing students’ knowledge of a topic and encourage thinking in answering questions that everyone else is also taking.

But the latter may not be entirely true. A Stanford study says question format can impact how boys and girls score on standardised tests. Researchers found that girls perform better on standardised tests that have more open-ended questions, while boys score higher when the tests include more multiple-choice questions.

Meanwhile, The Hechinger Report notes that assessments, when designed properly, can support, not just measure, student learning, building their skills and granting them the feedback they need.

“Assessments create feedback for teachers and students alike, and the high value of feedback – particularly timely feedback – is well-documented by learning scientists. It’s useful to know you’re doing something wrong right after you do it,” it said.

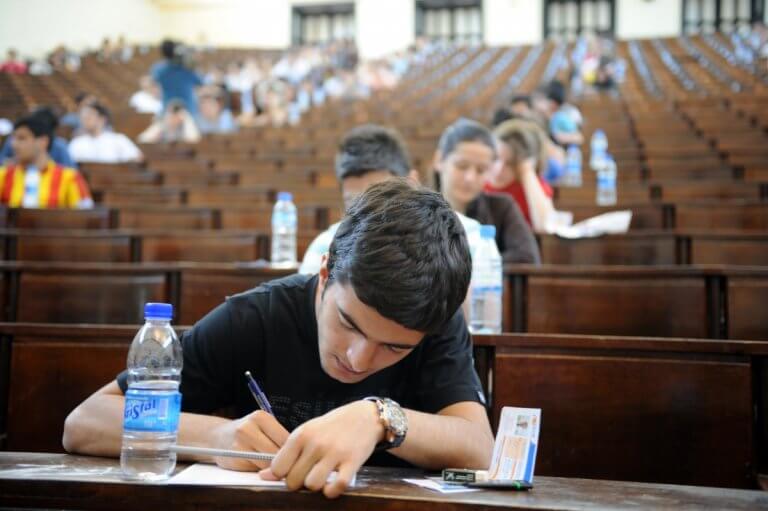

Exams are important for students, but they must be designed properly to ensure they support student learning. Source: Shutterstock

Conversely, critics of exams say the obsession with test scores comes at the expense of learning – students memorise facts, while some syllabi lack emphasis of knowledge application and does little to develop students’ critical thinking skills.

Meanwhile, teachers have argued that report card grades aren’t the best way to measure a student’s academic achievement , adding that they measure effort more than achievement.

Coursework, on the other hand, assesses a wider range of skills – it can consist of a range of activities such as quizzes, class participation, assignments and presentations. These steady assessments over an academic year suggests there is fair representation of students’ educational attainment while also catering for different learning styles.

Quizzes can be useful as they keep students on their toes and encourages them to study consistently, while giving educators a yardstick as to how well students are faring. Group work, however, can open up a can of worms when lazy students latch on to hard-working peers to pull up their grades, or when work is unevenly distributed among teammates.

It becomes clear that exams and coursework clearly test students’ different ‘muscles’, but do they supplement and support students’ learning outcomes and develop students as a whole?

The shifting tides

Coursework can develop skills such as collaboration and critical thinking among students, which exams cannot. Source: Shutterstock

News reports suggest that some countries are gradually moving away from an exam-oriented education system; these include selected schools in the US and Asian countries.

Last year, Malaysia’s Education Minister, Dr Maszlee Malik, said students from Year One to Three will no longer sit for exams come 2019, enabling the ministry to implement the Classroom-Based Assessment (PBD), in which they can focus on a pupil’s learning development.

Meanwhile, Singapore is cutting down on the number of exams for selected primary and secondary school levels, while Georgia’s school graduate exams will be abolished from 2020. Finland is a country known for not having standardised tests, with the exception of one exam at the end of students’ secondary school year.

Drawing from my experience, I found that a less exam-oriented system greatly benefitted me.

Going through 11 years of the Malaysian national education system was a testament that I did not perform well in an exam-oriented environment. I was often ‘first from the bottom’ in class, which did little to boost my confidence in school.

For university, I set out to select a programme that was less exam-oriented and eventually chose the American Degree Programme (ADP), while many of my schoolmates went with the popular A-Levels before progressing to their degree.

With the ADP, the bulk of student assessments (about 70 percent, depending on your institution) came from assignments, quizzes, class participation, presentations and the like, while the remaining 30 percent was via exams. Under this system, I found myself flourishing for the first time in an academic setting – my grades improved, I was more motivated to attend my classes and learned that I wasn’t as stupid as I was often made out to be during my school days.

This system of continuous assessments worked more in my favour than the stress of sitting for one major exam. In the former, my success or failure in an educational setting was not entirely dependent on how well I could pass standardised tests that required me to regurgitate facts through essays and open-ended or multiple choice questions.

Instead, I had more time to grasp new and alien concepts, and through activities that promoted continuous development, was able to digest and understand better.

Mixed assessments in schools and universities can be beneficial for developing well-rounded individuals. Source: Shutterstock

Additionally, shy students such as myself are forced between a rock and a hard place – to contribute to class discussions or get a zero for class participation, and to engage in group and solo presentations or risk getting zero for oral presentations.

One benefit to this system is that it gives you the chance to play to your strengths and work hard towards securing top marks in areas you care about. If you preferred the examination or assignments portion, for example, you could knock it out of the park in those areas to pull up your grades.

Some students may be all-rounders who perform well in both exam-oriented and coursework assessments, but not all students say the same. However, the availability of mixed assessments in schools and universities can be beneficial for developing well-rounded individuals.

Under this system, students who perform poorly in exams will still have to go through them anyway, while students who excel in exam-oriented conditions are also forced to undergo other forms of assessments and develop their skill sets, including creativity, collaboration, oral and critical thinking skills.

Students who argue that their grades will fall under mixed-assessments should rethink the purpose of their education – in most instances, degrees aim to prepare people for employment.

But can exams really prepare students for employment where they’ll be working with people with different skills, requiring them to apply critical thinking and communication skills over a period of time to ensure work is completed within stipulated deadlines, despite hiccups that can happen between the start and finishing line of a project?

It’ll help if parents, educators and policymakers are on the bandwagon, too, instead of merely chasing for children and students to obtain a string of As.

Grades hold so much power over students’ futures – from the ability to get an academic scholarship to gaining entry to prestigious institutions – and this means it can be difficult to get students who prefer one mode of assessment to convert to one that may potentially negatively affect their grades.

Ideally, education shouldn’t be about pitting one student against the other; it should be based on attaining knowledge and developing skills that will help students in their future careers and make positive contributions to the world.

Exams are still a crucial part of education as some careers depend on a student’s academic attainment (i.e. doctors, etc.). But rather than having one form of assessment over the other, matrimony between the two may help develop holistic students and better prepare them for the world they’ll soon be walking into.

Liked this? Then you’ll love…

Smartphones in schools: Yes, no or maybe?

How do universities maintain a cohesive class culture?

Popular stories

Money isn’t everything. for this tasmania-trained architect, improving society is his #1 goal..

The prestigious education of Japan’s royal family

6 cheapest universities in Europe to study medicine

6 most affordable universities in Finland for international students

- My Account |

- StudentHome |

- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility hub Accessibility hub

Postgraduate

- International

- News & media

- Business & apprenticeships

Open Research Online - ORO

Coursework versus examinations in end-of-module assessment: a literature review.

Copy the page URI to the clipboard

Richardson, John T. E. (2015). Coursework versus examinations in end-of-module assessment: a literature review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , 40(3) pp. 439–455.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.919628

In the UK and other countries, the use of end-of-module assessment by coursework in higher education has increased over the last 40 years. This has been justified by various pedagogical arguments. In addition, students themselves prefer to be assessed either by coursework alone or by a mixture of coursework and examinations than by examinations alone. Assessment by coursework alone or by a mixture of coursework and examinations tends to yield higher marks than assessment by examinations alone. The increased adoption of assessment by coursework has contributed to an increase over time in the marks on individual modules and in the proportion of good degrees across entire programmes. Assessment by coursework appears to attenuate the negative effect of class size on student attainment. The difference between coursework marks and examination marks tends to be greater in some disciplines than others, but it appears to be similar in men and women and in students from different ethnic groups. Collusion, plagiarism and personation (especially ‘contract cheating’ through the use of bespoke essays) are potential problems with coursework assessment. Nevertheless, the increased use of assessment by coursework has generally been seen as uncontentious, with only isolated voices expressing concerns regarding possible risks to academic standards.

Viewing alternatives

Public attention, number of citations, item actions.

This item URI

The Open University

- Study with us

- Work with us

- Supported distance learning

- Funding your studies

- International students

- Global reputation

- Sustainability

- Apprenticeships

- Develop your workforce

- Contact the OU

Undergraduate

- Arts and Humanities

- Art History

- Business and Management

- Combined Studies

- Computing and IT

- Counselling

- Creative Writing

- Criminology

- Early Years

- Electronic Engineering

- Engineering

- Environment

- Film and Media

- Health and Social Care

- Health and Wellbeing

- Health Sciences

- International Studies

- Mathematics

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Healthcare

- Religious Studies

- Social Sciences

- Social Work

- Software Engineering

- Sport and Fitness

- Postgraduate study

- Research degrees

- Masters in Social Work (MA)

- Masters in Economics (MSc)

- Masters in Creative Writing (MA)

- Masters degree in Education (MA/MEd)

- Masters in Engineering (MSc)

- Masters in English Literature (MA)

- Masters in History (MA)

- Masters in International Relations (MA)

- Masters in Finance (MSc)

- Masters in Cyber Security (MSc)

- Masters in Psychology (MSc)

- A to Z of Masters degrees

- OU Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Modern slavery act (pdf 149kb)

Follow us on Social media

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

- Contact the OU Contact the OU

- Modern Slavery Act (pdf 149kb)

Design and Grade Course Work

This resource provides a brief introduction to designing your course assessment strategy based on your course learning objectives and introduces best practices in assessment design. It also addresses important issues in grading, including strategies to curb cheating and grading methods that reduce implicit bias and provide actionable feedback for students.

In this document, assessments refer to all the ways students’ learning can be measured. This includes summative assessments such as tests and papers, but also formative assessments such as a survey to gauge understanding of course concepts.

Table of Contents:

Crafting effective assessments

Encouraging academic integrity.

- Grading fairly

Resources & further reading

Tie assessments to the course learning objectives. To determine what kinds of assessments to use in your course, consider what you want the students to learn to do and how that can be measured. When designing an overall plan, it is important to begin with the end in mind.

Consider what type of assessments best fit your learning objectives. For example, a case study is appropriate for measuring students’ ability to apply skills to a new situation, while a multiple choice exam is better for testing their understanding of concepts. This table of assessment choices from Carnegie Mellon University can help you think about the alignment of learning objectives and types of assessments.

Rethink traditional assessment to enhance the learning experience. At the end of a learning unit or module, summative assessments are frequently employed to measure students’ learning. These assessments are usually graded, cumulative in design and take the form of a midterm exam, research paper or final project. Consider replacing a traditional assessment with an authentic assessment situated in a meaningful, real-world context or modifying existing assessments to “do” the subject instead of recalling information. Here are some high-level questions for to get you started:

- Does this assessment replicate or simulate the contexts in which adults are “tested” in the workplace, civic life or personal life?

- Does this assessment challenge students to use what they’ve learned in solving or analyzing new problems?

- Does this assessment provide direct evidence of learning?

- Is this assessment realistic? Have students been able to practice along the way?

- Does this assessment truly demonstrate success and mastery of a skill students should have at the end of your course?

Further considerations for authentic assessment design are available in this guide from University of Illinois.

In practice, authentic assessments look different by discipline and level of the course. A good starting point is to research common examples of alternative assessments , but consider researching approaches in your discipline. There are also ways to improve traditional assessments such as quizzes to be a measure of true learning instead of memorization.

Our page on Alternative Strategies for Assessment and Grading outlines some options for creating assessment activities and policies which are learning-focused, while also being equitable and compassionate. The suggestions are loosely grouped by expected faculty time commitment.

Tailor learning by assessing previous knowledge. At the beginning of a learning unit or module, use a diagnostic assessment to gain insight into students’ existing understanding and skills prior to beginning a new concept. Examples of diagnostic assessments include: discussion, informal quiz, survey or a quick write paper ( see this list for more ideas ).

Use frequent informal assessments to monitor progress. Formative assessments are any assessments implemented to evaluate progress during the learning experience. When possible, provide several low-stakes opportunities for students to demonstrate progress throughout the course. Formative assessments provide five major benefits: (1)

- Students can identify their strengths and weaknesses with a particular concept and request additional support during the learning unit.

- Instructors can target areas where students are struggling that should be addressed either individually or in whole class activities before a more high-stakes assessment.

- Formative assessments can be reviewed and evaluated by peers which provides additional opportunities to learn, both for the reviewer and the student being reviewed.

- Informal, low-stakes assessments reduce student anxiety.

- A more frequent, immediate feedback loop can make some assessments (like graded quizzes) less necessary.

Examples include quick assessments like polls which can make large classes feel smaller or more informal, or end-of-class reflection questions on the day’s content. This longer list of low-stakes, formative assessments can help you find methods that work with your content and goals.

Use rubrics when possible. Students are likely to perform better on assessments when the grading criteria are clear. Research suggests that assessments designed with a corresponding rubric lead to an increased attention to detail and fewer misunderstandings in submitted work. (2) If you are interested in creating rubrics, Arizona State University has a detailed guide to get started .

| Improve student performance by clearly showing the student how their work will be evaluated and what is expected. | Encourage the instructor to clarify their criteria in specific terms. |

| Help students become better judges of the quality of their own work. | Provide objectivity and consistency in grading student work. |

| Provide students with more informative feedback about their strengths and areas that need improvement. | Provide useful feedback to the instructor regarding the effectiveness of instruction. |

Break up larger assessments into smaller parts. Scaffolding major or long-term work into smaller assignments with different deadlines gives students natural structure, helps with time and project management skills and provides multiple opportunities for students to receive constructive feedback. Students also benefit from scaffolding when:

- Rubrics are provided to assess discrete skills and evaluate student practice via smaller pre-assignments.

- The stakes are lowered for preliminary work.

- Opportunities are offered for rewrite or rework based on feedback.

Use practices that promote inclusive assessment design . Take inventory of the explicit and implicit norms and biases of your course assessments. For example, are your assessment questions phrased in a way that all students (including non-native English speakers) can be successful? Do your course assessments meet basic accessibility standards, including being appropriate for students with visual or hearing needs?

The Duke Community Standard embraces the principle that “intellectual and academic honesty are at the heart of the academic life of any university. It is the responsibility of all students to understand and abide by Duke’s expectations regarding academic work.” (3) Learning the rules of legitimacy in academic work is part of college education, so the topic of cheating and plagiarism should be embraced as part of ongoing discussion among students, and faculty instructors should remind students of this obligation throughout their courses.

Include a statement about cheating and plagiarism in your syllabus. Remind students that they must uphold the standards of student conduct as an obligation of participating in our learning community. This can be reinforced before important assessments as well. Studies have shown that when students have to manually agree to the Honor Pledge prior to submitting an assignment (either online or in person), they are less likely to cheat. (4)

Specify where training is available. Because of their cultural or academic experiences, some students may not be familiar with what constitutes plagiarism in your course. Students can use library resources to learn more about plagiarism and take the university’s plagiarism tutorial .

Include specific guidelines for collaboration, citation and the use of electronic sources for every assessment. For example, it may be necessary to define what kinds of online sources are considered cheating for your discipline (for example, online translators in language courses) or help students understand how to cite correctly .

Provide ongoing feedback to reduce the temptation to cheat. Students are more likely to seek short cuts when they don’t know how to approach a task. Requiring students to turn in smaller parts of a paper or project for feedback and a grade before the final deadline can lessen the risk of cheating. Having multiple milestones on larger assessments reduces the stress of finishing a paper at the last minute or cramming for a final exam.

Ask questions that have no single right answer. The most direct approach to reduce cheating is to design open-ended assessment items. When writing test or quiz questions ask yourself: could this answer be easily discovered online? If so, rewrite your question to elicit more critical thinking from your students.

Open-ended assessments can take the form of case studies, projects, essays, podcasts, interviews or “explain your work” problem sets. Students can provide examples of course concepts in a novel way. They can record themselves explaining the idea to someone else or make a mind map of related events or ideas. They can present their solutions to real-world scenarios as a poster or a podcast. If you choose to conduct an exam, designing questions that ask students to decide which concepts or equations to apply in a scenario, rather than testing recall, may make the most sense for many courses. You could include an oral exam component where students explain their work for a particular problem.

Minimize opportunities for cheating in tests and quizzes online. If you offer quizzes or tests through Sakai, there are several steps that you can take to reduce cheating, plagiarism or other violations:

- Sakai tests include a pledge not to violate the Duke Community Standard. You could also have this printed at the top of a physical test.

- Limit time. Set a time limit that gives students enough time to properly progress through the activity but not so much that unprepared students can research every question.

- Randomize question or answer order. When you randomize (or shuffle) your test or quiz questions, all students will still receive the same questions but not necessarily in the same order. This strategy is particularly useful when you have a large question pool and choose to show a few questions at a time. When you randomize the answers to a question, all students will still receive the same answers but not necessarily in the same order.

- Use large question pools. Pools allow you to use the same question across multiple assessments or create a large number of questions from which to pull a random subset. For example, you could develop (or repurpose) 30 questions in a pool and have Sakai randomly choose 15 of those questions for each student’s assessment.

- Hide correct answers and scores until the test or quiz is closed. This can prevent students from sharing questions and answers with peers during the assessment period.

- Require an explanation of the student’s answer. Require a rationale for their answer either as a short text question or perhaps a voice recording.

Duke has chosen not to implement a proctoring technology. When thinking about proctoring, keep in mind how implementing such policies and technologies might affect our ability to create equitable student-centered learning experiences. Several issues of student well-being and technological constraints you might want to keep in mind include:

- Student privacy : In an online setting, proctoring services essentially bring strangers into students’ homes or dorm rooms — places students may not be comfortable exposing. Additionally, often these services record and store actions of students on non-Duke servers and infrastructure. This makes proctoring services problematic for the in-class setting as well. These violations of privacy perpetuate inequity through the use of surveillance technologies.

- Technology access : If testing is online all students may not have the same access to technology (e.g., external webcams) for proctoring.

- Accessibility : Proctoring software can create more barriers for students who need accommodations.

- Unease: Proctoring reinforces a surveillance aspect to learning, which impacts student performance .

Grading Fairly

Start with clear instructions, a direct assignment prompt and transparent grading criteria. Explicit instructions reduce confusion and the number of emails that you may receive from your students requesting clarification on an assignment. Your assignment instructions should detail:

- Length requirements

- Formatting requirements

- Expectations of style, voice and tone

- Acceptable structure for reference citations

- Due date(s)

- Technology requirements needed for the assignment

- Description of the measures used to evaluate success

Offer meaningful feedback and a timely response when grading. There are many ways to provide feedback to students on submitted work. Regardless of the grading strategy and tool that you choose, there are a few best practices to consider when providing student feedback:

- Feedback should be prompt . Send feedback as soon as possible after the assignment to give students an adequate amount of time to reflect before moving on to the next assignment.

- Feedback should be equitable . Rubrics can help ensure that students are receiving consistent feedback for similar work.

- Feedback should be formative . Meaningful feedback focuses on students’ strengths and shares constructive areas to further develop their skills. It is not necessary to correct all errors if patterns can be pointed out.

We recommend avoiding curves for both individual assignments and final course grades. There are several downsides to curves that will negatively impact your pedagogy:

- Curves lower motivation to learn and incentivize cheating

- Curves create barriers to an inclusive learning environment

- Curves also “often result in grades unrelated to content mastery” ( Jeffrey Schinske and Kimberly Tanner )

Rather than using curves, you can introduce feedback strategies that allow students to improve their performance on future assessments by revising submitted work or reflecting on study habits.

Create customized rubrics to grade assignments consistently. Rubrics can reduce the grading burden over the long-term for instructors and increase the quality of the work students create. A well-designed rubric:

- Provides clear criteria for success that help students produce better work and instructors to be consistent with grading.

- Points out specific areas for students to address in future assignments.

- Allows for consistency in grading and more meaningful feedback.

Grade students anonymously. Blind grading removes any potential positive or negative bias when reviewing an individual’s work. The main assessment tools at Duke, Sakai and Gradescope, have easy controls for implementing anonymous grading.

Use a grade book that is visible to students. Students should have online access to their grades throughout the semester. It is not necessary to post their cumulative course grade at all times, but seeing the individual items is important. Knowing how they are doing reduces student stress before big assessments. An open and up-to-date grade book provides opportunities for students and instructors to address issues in a timely manner. It allows students to correct any omissions by the instructor and instructors have an immediate sense of which students are struggling as well.

Assessments

Best Practices for Inclusive Assessment (Duke University)

What are inclusive assessment practices? (Tufts University)

Sequencing and Scaffolding Assignments (University of Michigan)

Blind Grading (Yale University)

Using Rubrics (Cornell University)

How to Give Your Students Better Feedback with Technology (Chronicle of Higher Education)

- The Many Faces of Formative Assessment (International Journal of Teaching and Higher Education)

- A Review of Rubric Use in Higher Education (Reddy, Y, et al, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education)

- Duke Community Standard

- The Impact of Honor Codes and Perceptions of Cheating on Academic Cheating Behaviors, Especially for MBA Bound Undergraduates (O’Neill H., Pfeiffer C.)

Coursework vs Exams: What’s Easier? (Pros and Cons)

In A-Level , GCSE , General by Think Student Editor September 12, 2023 Leave a Comment

Coursework and exams are two different techniques used to assess students on certain subjects. Both of these methods can seem like a drag when trying to get a good grade, as they both take so many hours of work! However, is it true that one of these assessment techniques is easier than the other? Some students pick subjects specifically because they are only assessed via coursework or only assessed via exams, depending on what they find easiest. However, could there be a definite answer to what is the easiest?

If you want to discover whether coursework or exams are easier and the pros and cons of these methods, check out the rest of this article!

Disclaimer: This article is solely based on one student’s opinion. Every student has different perspectives on whether coursework or exams are easier. Therefore, the views expressed in this article may not align with your own.

Table of Contents

Coursework vs exams: what’s easier?

The truth is that whether you find coursework or exams easier depends on you and how you like to work. Different students learn best in different ways and as a result, will have differing views on these two assessment methods.

Coursework requires students to complete assignments and essays throughout the year which are carefully graded and moderated. This work makes up a student’s coursework and contributes to their final grade.

In comparison, exams often only take place at the end of the year. Therefore, students are only assessed at one point in the year instead of throughout. All of a student’s work then leads up to them answering a number of exams which make up their grade.

There are pros and cons for both of these methods, depending on how you learn and are assessed best. Therefore, whether you find coursework or exams easier or not depends on each individual.

Is coursework easier than exams?

Some students believe that coursework is easier than exams. This is because it requires students to work on it all throughout the year, whilst having plenty of resources available to them.

As a result, there is less pressure on students at the end of the year, as they have gradually been able to work hard on their coursework, which then determines their grade. If you do coursework at GCSE or A-Level, you will generally have to complete an extended essay or project.

Some students find this easier than exams because they have lots of time to research and edit their essays, allowing the highest quality of work to be produced. You can discover more about coursework and tips for how to make it stand out if you check out this article from Oxford Royale.

However, some students actually find coursework harder because of the amount of time it takes and all of the research involved. Consequently, whether you prefer coursework or not depends on how you enjoy learning.

What are the cons of coursework?

As already hinted at, the main con of coursework is the amount of time it takes. In my experience, coursework was always such a drag because it took up so much of my time!

When you hear that you have to do a long essay, roughly 2000-3000 words, it sounds easily achievable. However, the amount of research you have to do is immense, and then editing and reviewing your work takes even more time.

Coursework should not be over and done within a week. It requires constant revisits and rephrasing, as you make it as professional sounding and high quality as possible. Teachers are also unable to give lots of help to students doing coursework. This is because it is supposed to be an independent project.

Teachers are able to give some advice, however not too much support. This can be difficult for students who are used to being given lots of help.

You also have to be very careful with what you actually write. If you plagiarise anything that you have written, your coursework could be disqualified. Therefore, it is very important that you pay attention to everything you write and make sure that you don’t copy explicitly from other websites. This can make coursework a risky assessment method.