Find a Surgeon

Search by U.S. State, Procedure and Insurance Search by Country and Procedure Browse the Global Surgeon Maps

Gender Surgeons in Germany

Dr. juergen schaff.

Dr. Schaff offers gender reassignment surgery in Germany, both MTF and FTM procedures, including the fibula flap phalloplasty.

Dr. Laszlo Szalay

Dr. Klaus Exner

Dr. michael sohn, dr. tobias s. pottek, dr. ute ebert, dr. hendrik schöll, dr. susanne morath, dr. jens christian wallmichrath.

Dr. Robert Kampmann

Dr. markus krankenhaus, dr. cornelius klein, dr. wolf j. holtje, dr. wolfgang muhlbauer, dr. hans-georg luhr, dr. hans-peter howaldt, dr. cvetan taskov, dr. michael krueger, dr. jutta krocker, dr. andree faridi, dr. marcus küntscher, dr. jens diedrichson.

Dr. Wolfgang Funk

Dr. kay arne klemenz.

- Abdominal Surgery

- Dermatology and Venereology

- Endocrine Surgery

- Foot and Ankle Surgery

- Gastroenterology

- General and Internal Medicine

- Gynaecology

- Hand Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedic / Trauma Surgery

- Otorhinolaryngology

- Paediatrics

- Paediatric Surgery

- Plastic / Cosmetic Surgery

- ReconstructiveSurgery

- Rheumatology

- Spinal Diseases

- Sports Medicine

- Transgender Surgery

- Vascular Surgery, Venous Disorders

- MEOCHECK Superior Programme

- MEOCHECK Premium Programme

- MEOCHECK Basis Programme

- International patients

Private practice Transgender Surgery Meoclinic Berlin

Transgender Surgery at the MEOCLINIC in Berlin-Mitte

Our medical expert team in berlin-mitte is available for short-notice appointments..

A sex reassignment surgery is a big step for you as a patient. We will be happy to assist you in this process and help you fulfill your wish.

A sex reassignment procedure is always preceded by a detailed indication consultation at the MEOCLINIC private practices where you can clarify all medical and personal questions. Your doctor will inform you in detail about individual surgical steps and techniques and provide explanations on possible risks and complications.

Appointment

Our experts.

Dr. med. Paul Jean Daverio

Facharzt für Plastische- und Wiederherstellungs-Chirurgie, Mikrochirurgie

Schwerpunkt geschlechtsangleichende Operationen

Mehr erfahren

Our treatment scope.

- Sex Reassignment Female to Male (FtM)

- Sex Reassignment Male to Female (MtF)

- Erectile Prosthetics and Scrotoplasty

- Secondary Surgery in case of complications

Our goal is to provide the best possible result for you as a patient. Sex reassignment surgery aims for natural aesthetics as well as optimal function and sensitivity.

We will gladly discuss all further details with you in a personal consultation session. We look forward to you contacting us.

If you wish to learn more about the treatment in advance, please find detailed information (in German) here .

Spezialsprechstunden

Endokrine Chirurgie

Eine Störung im Ablauf der Hormonproduktion führt zu einer Über- oder Unterfunktion der endokrinen Organe, infolge dessen es zu Bluthochdruck, Herzrhythmusstörungen aber auch der Ausbildung von Tumoren kommen kann.

Endocrine surgery

Bei uns sind sie in guten händen.

Kurzfristige Terminvergabe

Parken im Haus

Wohlfühlatmosphäre

Professionelle Ärzte

The Forgotten History of the World's First Trans Clinic

The Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin would be a century old if it hadn’t fallen victim to Nazi ideology

By Brandy Schillace

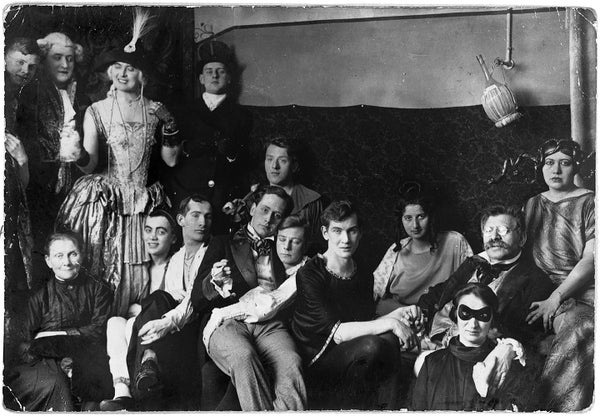

Costume party at the Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin, date and photographer unknown. Magnus Hirschfeld ( in glasses ) holds hands with his partner, Karl Giese ( center ).

Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin

Late one night on the cusp of the 20th century, Magnus Hirschfeld, a young doctor, found a soldier on the doorstep of his practice in Germany. Distraught and agitated, the man had come to confess himself an Urning —a word used to refer to homosexual men. It explained the cover of darkness; to speak of such things was dangerous business. The infamous “Paragraph 175” in the German criminal code made homosexuality illegal; a man so accused could be stripped of his ranks and titles and thrown in jail.

Hirschfeld understood the soldier’s plight—he was himself both homosexual and Jewish—and did his best to comfort his patient. But the soldier had already made up his mind. It was the eve of his wedding, an event he could not face . Shortly after, he shot himself.

The soldier bequeathed his private papers to Hirschfeld, along with a letter: “The thought that you could contribute to [a future] when the German fatherland will think of us in more just terms,” he wrote, “sweetens the hour of death.” Hirschfeld would be forever haunted by this needless loss; the soldier had called himself a “curse,” fit only to die, because the expectations of heterosexual norms, reinforced by marriage and law, made no room for his kind. These heartbreaking stories, Hirschfeld wrote in The Sexual History of the World War , “bring before us the whole tragedy [in Germany]; what fatherland did they have, and for what freedom were they fighting?” In the aftermath of this lonely death, Hirschfeld left his medical practice and began a crusade for justice that would alter the course of queer history.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hirschfeld sought to specialize in sexual health, an area of growing interest. Many of his predecessors and colleagues believed that homosexuality was pathological, using new theories from psychology to suggest it was a sign of mental ill health. Hirschfeld, in contrast, argued that a person may be born with characteristics that did not fit into heterosexual or binary categories and supported the idea that a “third sex” (or Geschlecht ) existed naturally. Hirschfeld proposed the term “sexual intermediaries” for nonconforming individuals. Included under this umbrella were what he considered “situational” and “constitutional” homosexuals—a recognition that there is often a spectrum of bisexual practice—as well as what he termed “transvestites.” This group included those who wished to wear the clothes of the opposite sex and those who “from the point of view of their character” should be considered as the opposite sex. One soldier with whom Hirschfeld had worked described wearing women’s clothing as the chance “to be a human being at least for a moment.” He likewise recognized that these people could be either homosexual or heterosexual, something that is frequently misunderstood about transgender people today.

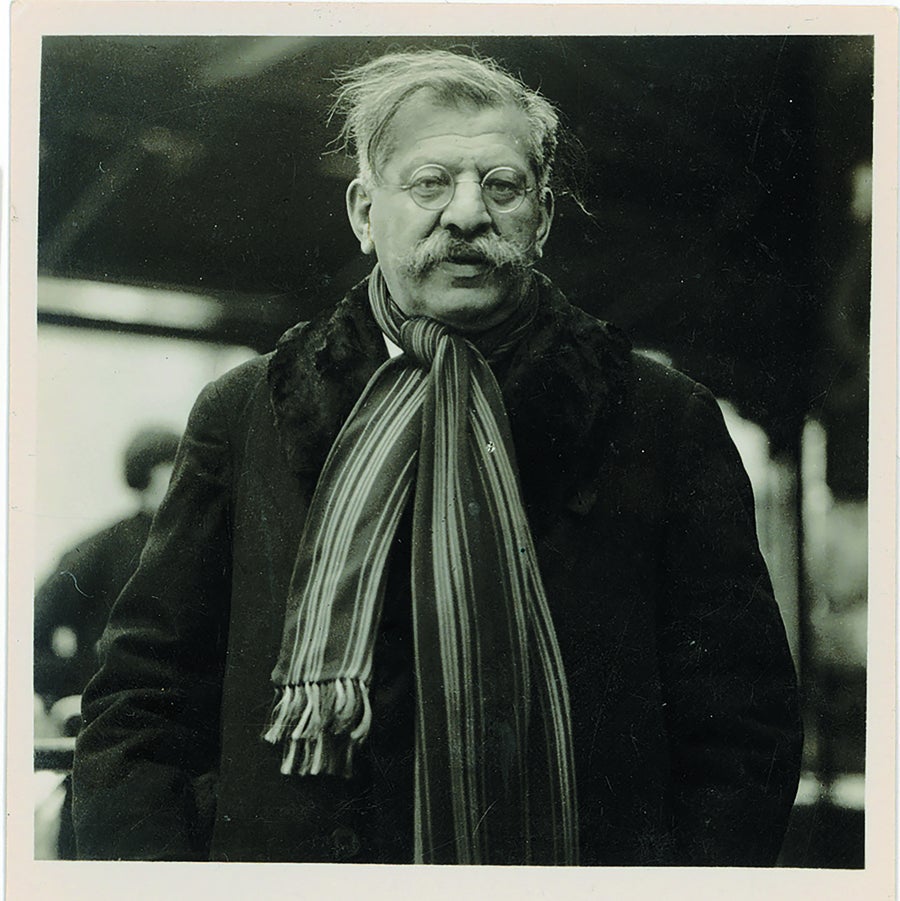

Magnus Hirschfeld, director of the Institute for Sexual Research, in an undated portrait. Credit: Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin

Perhaps even more surprising was Hirschfeld’s inclusion of those with no fixed gender, akin to today’s concept of gender-fluid or nonbinary identity (he counted French novelist George Sand among them). Most important for Hirschfeld, these people were acting “in accordance with their nature,” not against it.

If this seems like extremely forward thinking for the time, it was. It was possibly even more forward than our own thinking, 100 years later. Current anti-trans sentiments center on the idea that being transgender is both new and unnatural. In the wake of a U.K. court decision in 2020 limiting trans rights, an editorial in the Economist argued that other countries should follow suit , and an editorial in the Observer praised the court for resisting a “disturbing trend” of children receiving gender-affirming health care as part of a transition.

Related: The Disturbing History of Research into Transgender Identity

But history bears witness to the plurality of gender and sexuality. Hirschfeld considered Socrates, Michelangelo and Shakespeare to be sexual intermediaries; he considered himself and his partner Karl Giese to be the same. Hirschfeld’s own predecessor in sexology, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, had claimed in the 19th century that homosexuality was natural sexual variation and congenital.

Hirschfeld’s study of sexual intermediaries was no trend or fad; instead it was a recognition that people may be born with a nature contrary to their assigned gender. And in cases where the desire to live as the opposite sex was strong, he thought science ought to provide a means of transition. He purchased a Berlin villa in early 1919 and opened the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (the Institute for Sexual Research) on July 6. By 1930 it would perform the first modern gender-affirmation surgeries in the world.

A Place of Safety

A corner building with wings to either side, the institute was an architectural gem that blurred the line between professional and intimate living spaces. A journalist reported it could not be a scientific institute, because it was furnished, plush and “full of life everywhere.” Its stated purpose was to be a place of “research, teaching, healing, and refuge” that could “free the individual from physical ailments, psychological afflictions, and social deprivation.” Hirschfeld’s institute would also be a place of education. While in medical school, he had experienced the trauma of watching as a gay man was paraded naked before the class, to be verbally abused as a degenerate.

Hirschfeld would instead provide sex education and health clinics, advice on contraception, and research on gender and sexuality, both anthropological and psychological. He worked tirelessly to try to overturn Paragraph 175. Unable to do so, he got legally accepted “transvestite” identity cards for his patients, intended to prevent them from being arrested for openly dressing and living as the opposite sex. The grounds also included room for offices given over to feminist activists, as well as a printing house for sex reform journals meant to dispel myths about sexuality. “Love,” Hirschfeld said, “is as varied as people are.”

The institute would ultimately house an immense library on sexuality, gathered over many years and including rare books and diagrams and protocols for male-to-female (MTF) surgical transition. In addition to psychiatrists for therapy, he had hired Ludwig Levy-Lenz, a gynecologist. Together, with surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt, they performed male-to-female surgery called Genitalumwandlung —literally, “transformation of genitals.” This occurred in stages: castration, penectomy and vaginoplasty. (The institute treated only trans women at this time; female-to-male phalloplasty would not be practiced until the late 1940s.) Patients would also be prescribed hormone therapy, allowing them to grow natural breasts and softer features.

Their groundbreaking studies, meticulously documented, drew international attention. Legal rights and recognition did not immediately follow, however. After surgery, some trans women had difficulty getting work to support themselves, and as a result, five were employed at the institute itself. In this way, Hirschfeld sought to provide a safe space for those whose altered bodies differed from the gender they were assigned at birth—including, at times, protection from the law.

1926 portrait of Lili Elbe, one of Hirschfeld's patients. Elbe's story inspired the 2015 film The Danish Girl . Credit: https://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0031864.html (CC BY 4.0)

Lives Worth Living

That such an institute existed as early as 1919, recognizing the plurality of gender identity and offering support, comes as a surprise to many. It should have been the bedrock on which to build a bolder future. But as the institute celebrated its first decade, the Nazi party was already on the rise. By 1932 it was the largest political party in Germany, growing its numbers through a nationalism that targeted the immigrant, the disabled and the “genetically unfit.” Weakened by economic crisis and without a majority, the Weimar Republic collapsed.

Adolf Hitler was named chancellor on January 30, 1933, and enacted policies to rid Germany of Lebensunwertes Leben , or “lives unworthy of living.” What began as a sterilization program ultimately led to the extermination of millions of Jews, Roma, Soviet and Polish citizens—and homosexuals and transgender people.

When the Nazis came for the institute on May 6, 1933, Hirschfeld was out of the country. Giese fled with what little he could. Troops swarmed the building, carrying off a bronze bust of Hirschfeld and all his precious books, which they piled in the street. Soon a towerlike bonfire engulfed more than 20,000 books, some of them rare copies that had helped provide a historiography for nonconforming people.

The carnage flickered over German newsreels. It was among the first and largest of the Nazi book burnings. Nazi youth, students and soldiers participated in the destruction, while voiceovers of the footage declared that the German state had committed “the intellectual garbage of the past” to the flames. The collection was irreplaceable.

Levy-Lenz, who like Hirschfeld was Jewish, fled Germany. But in a dark twist, his collaborator Gohrbandt, with whom he had performed supportive operations, joined the Luftwaffe as chief medical adviser and later contributed to grim experiments in the Dachau concentration camp. Hirschfeld’s likeness would be reproduced on Nazi propaganda as the worst kind of offender (both Jewish and homosexual) to the perfect heteronormative Aryan race.

In the immediate aftermath of the Nazi raid, Giese joined Hirschfeld and his protégé Li Shiu Tong, a medical student, in Paris. The three would continue living together as partners and colleagues with hopes of rebuilding the institute, until the growing threat of Nazi occupation in Paris required them to flee to Nice. Hirschfeld died of a sudden stroke in 1935 while still on the run. Giese died by suicide in 1938. Tong abandoned his hopes of opening an institute in Hong Kong for a life of obscurity abroad.

Over time their stories have resurfaced in popular culture. In 2015, for instance, the institute was a major plot point in the second season of the television show Transparent , and one of Hirschfeld’s patients, Lili Elbe, was the protagonist of the film The Danish Girl . Notably, the doctor’s name never appears in the novel that inspired the movie, and despite these few exceptions the history of Hirschfeld’s clinic has been effectively erased. So effectively, in fact, that although the Nazi newsreels still exist, and the pictures of the burning library are often reproduced, few know they feature the world’s first trans clinic. Even that iconic image has been decontextualized, a nameless tragedy.

The Nazi ideal had been based on white, cishet (that is, cisgender and heterosexual) masculinity masquerading as genetic superiority. Any who strayed were considered as depraved, immoral, and worthy of total eradication. What began as a project of “protecting” German youth and raising healthy families had become, under Hitler, a mechanism for genocide.

One of the first and largest Nazi book burnings destroyed the library at the Institute for Sexual Research. Credit: Ullstein Bild and Getty Images

A Note for the Future

The future doesn’t always guarantee progress, even as time moves forward, and the story of the Institute for Sexual Research sounds a warning for our present moment. Current legislation and indeed calls even to separate trans children from supportive parents bear a striking resemblance to those terrible campaigns against so-labeled aberrant lives.

Studies have shown that supportive hormone therapy, accessed at an early age, lowers rates of suicide among trans youth. But there are those who reject the evidence that trans identity is something you can be “born with.” Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins was recently stripped of his “humanist of the year” award for comments comparing trans people to Rachel Dolezal , a civil rights activist who posed as a Black woman, as though gender transition were a kind of duplicity. His comments come on the heels of legislation in Florida aiming to ban trans athletes from participating in sports and an Arkansas bill denying trans children and teens supportive care.

Looking back on the story of Hirschfeld’s institute—his protocols not only for surgery but for a trans-supportive community of care, for mental and physical healing, and for social change—it’s hard not to imagine a history that might have been. What future might have been built from a platform where “sexual intermediaries” were indeed thought of in “more just terms”? Still, these pioneers and their heroic sacrifices help to deepen a sense of pride—and of legacy—for LGBTQ+ communities worldwide. As we confront oppressive legislation today, may we find hope in the history of the institute and a cautionary tale in the Nazis who were bent on erasing it.

Brandy Schillace is editor in chief of BMJ's Medical Humanities journal and author of the recently released book Mr. Humble and Doctor Butcher , a biography of Robert White, who aimed to transplant the human soul.

Transsexuality

Male is male and female is female! This is true for the vast majority of us – despite all individual differences. That is why hardly anyone can imagine what it means when this is not the case. In fact, according to estimates, at least 0.005% of all people are born in the “wrong body”. The reasons that lead to transsexuality (transidentity) are not yet finally researched, but much speaks for genetic (hereditary) causes.

Life as a transsexual person For those affected, transsexuality often means severe psychological suffering, exclusion from society, as well as a long and painful path to the long-awaited surgical gender reassignment.

Transgender surgery at Klinik Sanssouci Surgical gender reassignment procedures have been performed at Klinik Sanssouci for over 20 years.

While many clinics perform these gender reassignments in several individual surgeries, we prefer that the respective steps required for gender reassignment are combined in a single surgery (“All in One”). This reduces the duration of the entire gender reassignment and healing process.

This requires not only careful organization before, during and after surgery, but also the coordination of multiple surgical teams, as the individual surgical steps must be perfectly coordinated.

Due to the large number of gender reassignment surgeries that have already been performed at our clinic, Klinik Sanssouci can look back on a considerable amount of experience in this area – from preventive care to aftercare:

The pre-operative discussions, the preliminary examinations as well as the inpatient and also outpatient aftercare also take place in our clinic. In addition, our patients find support with many other questions on the subject of gender reassignment.

Our surgeons are renowned experts in their respective fields. After Dr. Paul Daverio, who has led the transgender surgery department from the beginning, moved to a new place of work at the age of 74 after his successful work with us, the medical leadership of the team has been in the hands of Dr. Olivier Bauquis from Lausanne, Switzerland, since 2018. Dr. Bauquis has been performing transgender surgeries for many years and accordingly has a great expertise and reputation.

In addition, we were able to gain Dr. Jürgen Schaff, another internationally renowned surgeon, for our clinic in 2020. Dr. Jürgen Schaff had previously performed man-to-woman operations in Munich at Klinikum Rechts der Isar with great dedication and success. In doing so, he has continuously refined the classical and well-known surgical methods and developed them into his so-called combined method.

We are very pleased to be able to offer our patients an even broader range of services in the field of TS surgery with two experienced specialists in transgender surgery.

Female-to-Male

Female-to-male surgery: phalloplasty Phalloplasty, penoid reconstruction as part of female-to-male (ftm) gender reassignment surgery, is arguably the most challenging and complex operation in the field of transsexual surgery.

The technique developed by Dr. Paul Daverio, in which the penoid (“artificial penis”) is formed in a microsurgical operation from skin and subcutaneous tissue including nerves and blood vessels of the forearm (so-called forearm flap), is nowadays considered the standard procedure for gender reassignment worldwide. It leads to the best optical and functional results and has been practiced at Klinik Sanssouci for over 20 years.

Surgical technique: The steps of surgical gender reassignment. Female-to-male surgical gender reassignment is performed under general anesthesia. This procedure takes about seven to nine hours and includes:

- the removal of the breasts (mastectomy)

- removal of the uterus (hysterectomy)

- removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes (ovarectomy, adnectomy)

- removal of the vagina (colpectomy)

- the shaping of the penoid including the new urethra (neo-urethra)

- the plastic reconstruction of a glans (glansplasty)

- the lengthening of the female urethra with the labia minora

- the relocation of the penoid from the left forearm to the pubic area. The arteries (arteries) and veins (veins) of the penoid are connected to the corresponding blood vessels of the thigh. At the same time, the inguinal nerves are connected to the penoid nerves, as well as the lengthened urethra to the newly formed urethra.

- covering the tissue defect on the forearm with skin obtained either from the groin or from the excess skin of the breast.

- the preparation of the labia majora, where the artificial testicles will be implanted later.

Important: The clitoris (clit) remains at the base of the penoid and is not removed, only its covering epidermis. Thus, the ability to orgasm is preserved.

After the surgery

- After the surgery, intensive supervision with monitoring takes place. There will be several daily visits as well as regular dressing changes and wound inspections by our doctors.

- You may get up for the first time on the 6th day after the surgery.

- The bladder catheter is removed on the 12th day. From this moment on you can urinate standing up.

- Usually, you can leave the clinic on the 14th to 16th day.

- Further treatment after female-to-male gender reassignment can be performed by your doctors at your place of residence.

- Depending on your professional situation, you can expect to be unable to work for about 6 weeks.

Complications Female-to-male gender reassignment surgery, especially penoid reconstruction (phalloplasty), is a complex procedure and therefore prone to complications. At Klinik Sanssouci, complications occur with about 5% of our patients.

Possible complications of phalloplasty include:

Stenosis This is a constriction at the connection between the urethra and the newly formed urethra (neo-urethra). This complication can usually be corrected by simple bougienage (widening) by the urologist. Only in 1 to 2% of cases is a minor second surgery required, often under local anesthesia, to widen this constriction.

Fistula This is a connection between the urethra and the skin surface through which urine can leak out. Fistulas usually close spontaneously after two to three months. If this does not occur, the fistula can be closed in a minor procedure under local anesthesia. Serious complications such as complete penoid loss (flap loss) are very rare.

Erectile prosthesis / testicular replacement A second procedure is necessary if an erectile prosthesis is to be installed. This surgery is possible if there is feeling in the penoid, which is usually about eight to ten months after the phalloplasty surgery.

As erectile prosthesis we use a so-called hydraulic implant from American Medical Systems (AMS) with a pump (AMS 700), which is placed in the newly formed scrotum (neoscrotum). A reservoir is surgically placed under the abdominal wall muscles. We place two inflatable silicone rods into the penoid. An erection is then possible by means of this pumping system. We also implant silicone testicles in the scrotum.

Male-to-female

Surgical technique The surgical male-to-female sex adjustment is performed under general anesthesia and takes about 4-5 hours. If desired, we can perform augmentation at the same time (insertion of a silicone implant for breast augmentation or augmentation with autologous fat). At the same time, a thyroid cartilage reduction is also possible.

For sex adjustment, we offer two different methods (Classic penile inversion and combined method), both of which provide excellent results, but differ in several ways.

Classic penile inversion involves the following surgical steps:

Removal of the testicles (orchidectomy)

- plastic construction of a neovagina with an island flap plasty

- plastic construction of a sensitive neoclitoris

- plastic construction of labia from scrotum

- shortening of the urethra

- cavernous body removal

- plastic construction of pubic mound

- breast reconstruction if necessary

- if necessary, reduction of the thyroid cartilage

In the combined method, additional skin grafts and the original urethra are used to build up a neovagina. Due to the special incision in this method, a more natural vulvoplasty (plastic reconstruction of the labia) is possible.

The following surgical steps are performed:

- removal of the testicles (orchidectomy)

- plastic construction of a neovagina with a combined island flap plasty, free skin graft from the skin of the scrotum as well as pedicled urethral skin

- plastic construction of labia and clitoral hood from parts of penile shaft skin

Due to the special incision, a second surgery is mandatory for the combined method. This involves some fine plastic work that cannot technically be implemented in the first surgery. Usually, the desired breast augmentation and other optional plastic procedures are also performed during this second surgery.

In direct comparison, each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, which we will be happy to discuss with you in a personal consultation in order to select the optimal treatment strategy for you.

After surgery

- after the surgery, intensive supervision with monitoring takes place. There are several daily rounds as well as regular dressing changes and wound checks by our doctors

- you can already get up on the 1st day and also go to the toilet

- the urinary catheter is removed on day 6 to 8

- Usually you can leave the clinic on the 8th to 12th day

- further treatment after male-to-female gender reassignment surgery can be performed by your doctors at your place of residence

- depending on the professional situation, an inability to work of approx. 4 weeks is to be expected

- in the combined method, bougienage (dilatation) of the neovagina must be performed – written instructions for bougienage after discharge can be found here (PDF, 39k).

Complications Complications occur in less than 5% of our patients.

- postoperative bleeding approx. 1 %

- narrowing (stenosis) of the urethral opening 1-2 %

- narrowing (stenosis) of the neovagina approx. 1 %

- we were not able to record any serious complications

- in about 30% of our patients, we perform corrective surgery after about 3-6 months, when the vaginal entrance is constricted by a small fold formed during invagination (invagination) of the original penile skin.

Requirements

For female-to-male or male-to-female gender reassignment, the following medical as well as legal requirements are necessary at Klinik Sanssouci:

- You should have undergone opposite-sex hormone treatment for at least six to eight months.

- We also need two expert opinions from you that confirm your transsexuality (transidentity). These can be, for example, the expert opinions that you obtained as part of your change of first name and civil status.

Of course, we will be happy to advise you in a personal preliminary consultation about the exact procedure of the operation and answer your questions. You can make an appointment with us, please use our contact form.

Costs / Cost coverage

In general, a transsexual patient has the right to a gender reassignment surgery. Usually, this is not declined by the health insurances. However, there is no obligation for the statutory health insurance companies to cover the costs of treatment in a private clinic.

The vast majority of our transsexual patients have statutory or private health insurance and have been granted reimbursement for an operation in our clinic on a case-by-case basis. Private health insurances usually reimburse partial amounts. We will be happy to assist you with the application process. In particular, you will need a cost estimate from us, which you will receive from us during your consultation appointment.

International patients who have to pay their costs in advance as self-payers should also obtain a cost estimate.

Please feel free to contact us with any questions you may have regarding the details of reimbursement and billing.

Frequently asked questions

Female-to-male

What methods of phalloplasty do you use and what are the functional results? We perform phalloplasty with a so-called free forearm flap. The patient can urinate standing up after the operation on the 12th day. Sexual sensitivity is preserved because the clitoris (clit) is not removed in our method. All surgical steps are performed in one session.

Why do you perform all surgical steps in one session? This procedure, the all-in-one surgery, significantly reduces the duration of the entire inpatient stay, and of course also the number of surgeries. An essential consideration is also the rapid restoration of full working capacity. It is always claimed that the risks increase due to multiple surgery, but with careful organization, good teamwork and very great experience, it is possible to perform individual surgical steps with several surgical teams at the same time without extending the total surgical time. One-stage surgery also avoids scarring adhesions in the vaginal area, which are disadvantageous in a second operation. If the breast is removed at the same time, we can use the excess skin for coverage and, if necessary, do without other skin removal sites (fewer scars). Not to be forgotten are stress factors that are eliminated when the patient has to undergo surgery only once.

Do you work with microsurgery? Yes. In phalloplasty, the penoid is formed from skin and subcutaneous tissue, including nerves and blood vessels of the forearm (called the forearm flap) in a microsurgical surgery.

How many surgeries are necessary until a final result? At Klinik Sanssouci Potsdam, two surgeries are necessary for complete female-to-male gender reassignment: The first surgery includes removal of the uterus (hysterectomy), removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes (ovarectomy, adnectomy), removal of the breast (mastectomy), removal of the vagina (colpectomy), and penoid reconstruction (phalloplasty). In a second surgery (about eight to ten months after the first surgery), an erectile prosthesis and a silicone testicle are implanted into the newly formed scrotum.

How long does a patient have to stay in the clinic? For the first surgery, during which the penoid reconstruction (phalloplasty) takes place, you will need to plan for about 14 to 16 days of hospitalization.

What is the sensitivity of the penoid (neophallus)? The sensitivity, i.e. the sensation of the penoid, corresponds to normal skin sensitivity, comparable to the sensitivity of the skin on the forearm. Sensitivity is achieved by the ingrowth of nerves about eight to ten months after the initial surgery. Some erotic sensitivity, starting from nerves of the clitoris, is also possible.

What happens to the clitoris? Will it be removed or how will this important organ be preserved? During the phalloplasty surgery we preserve the clitoris completely and with it the sensitivity and sexual experience. We achieve this by only removing (deepithelializing) the clitoris from its epidermis, placing it at the base of the penoid and only covering it with skin so that arousal is possible as before the procedure. We do not consider the removal of the clitoris to be useful.

Have serious problems occurred at the forearm collection site? No. In the first days and weeks after the phalloplasty surgery, the hand may swell a little and become thicker. Then you should keep it elevated. We also recommend regular exercise of the hand. Serious, for example motor (movement) problems have not occurred – even fine motor movements of the hand are not affected.

Where are scars found on the penoid and are they visible? The only scar that will be visible on the penis is on the back of the penoid, so it will not be visible from the front.

Is there an acorn buildup? And when does it take place? Yes, glans reconstruction (glansplasty) is performed as standard together with phalloplasty in the first procedure.

Will a sensitive clitoris be created and how is it done? Microsurgically, while preserving the blood vessels, a clitoris is constructed from a portion of the glans (penis) in such a way that it is sexually aroused and placed in a typical location.

Are additional surgeries performed at the same time and what are they often? If desired, we perform breast reconstruction, i.e. implantation of a silicone prosthesis, in the same session. If desired, a thyroid cartilage reduction is also possible. These procedures extend the total operation time only insignificantly.

Will follow-up procedures be necessary and how often? Due to invagination of the original penile skin for the construction of the neovagina, there is often a fold at the posterior vaginal entrance, which we leave intraoperatively in order not to endanger blood circulation and thus good healing of the penile skin in the pelvis. Therefore, in about 30% of our patients we perform a widening of the vaginal entrance about 3-6 months after the initial procedure. During this procedure, small labia are formed at the same time and, if desired, the clitoris is reduced in size. As a rule, the clitoris is created during the initial operation in such a way that the safety of blood circulation and sensitivity are ensured, so that for many patients the clitoris primarily appears to be somewhat large. This is corrected during the follow-up surgery.

Are other procedures performed in your clinic for optical adaptation to the female gender? Reduction of the larynx can be performed. Likewise, nose correction and other procedures from the repertoire of aesthetic plastic surgery are possible.

When is sexual intercourse possible after surgery? There is no set rule, but medically it is possible to have normal sexual intercourse about 6 weeks after surgery.

Where are visible scars found? There are scars only on the labia majora, which are formed by reduction of the scrotum.

At what point is vaginal dilatation possible and do you use a so-called stent? After surgery, a loose tamponade is inserted into the neovagina, which is replaced on the 5th to 6th day. Careful stretching with a small dildo is possible about 10 to 14 days after surgery. It is not necessary to use a stent.

Can there be problems with sexual intercourse after surgery? Every transsexual patient should keep in mind that the pelvis of a man is much smaller and narrower than usually the pelvis of a so-called biological woman. In addition, the pelvic floor muscles are usually more strongly developed and not as soft and stretchy as in bio-women. For these reasons, it is not uncommon for muscular constriction to occur, which can persist over a longer period of time and can also lead to difficulties during sexual intercourse. Consistent stretching and relaxation is helpful in this case.

Specialist in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Specialist in Gynecology and Obstetrics

Specialist in Surgery Specialist in Plastic and Cosmetic Surgery Specialist in Hand Surgery

Specialist in Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery Hand Surgeon

Physician Assistant

Dr. med. Olivier Bauquis

www.olivierbauquis.ch

Specializations Transsexuality surgery

Range of Medical Services Gender reassignment surgery female-to-male and male-to-female

Contact / Consultation Hours Consultation Center Potsdam Helene-Lange-Straße 11 14469 Potsdam ✆ +49 (0) 331 280 87 200 🖷 +49 (0) 331 280 87 209 📧 [email protected]

More Information „Transsexualität: Im falschen Körper“ mit Dr. Olivier Bauquis (in German, SRF)

- Senior physician at the University Hospital of Lausanne, Switzerland

- Co-director of the transgender network Vaud-Genève since 2017

- Medical expert for transgender surgery

- Stays abroad: 2011, Montréal, Canada, Dr. P. Brassard: surgery of transsexuality 2014, Ghent, Belgium, Prof. S. Monstrey: surgery of transsexuality

- 2006 Start of specialization in surgery of transsexuality

- Conference president “Transsexualité” at the Women’s Health Congress, 2012

- Session chair: “Surgery of gender reassignment” at the annual congress of the Swiss Society of Surgery, 2013

- Article “Gender reassignment surgery” in the Swiss Med Forum (PDF in German, 921k)

- Article „Chaque semaine au CHUV un patient change de sexe“ in VAUD (JPEG in French, 803k)

Memberships

- Swiss Medical Association (FMH)

- Swiss Society for Hand Surgery

- Swiss Society for Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- European Society for Surgery of Transsexuality

Dr. med. Florian Müller

www.krankenhaus-waldfriede.de

Specializations Minimally invasive gynecological procedures

Contact / Consultation Hours Krankenhaus Waldfriede Gynäkologie, Haus A, 3. OG Argentinische Allee 40 14163 Berlin ✆ +49 (0) 30 81 810 245 oder ✆ +49 (0) 30 81 810 207 🖷 +49 (0) 30 81 810-77245 📧 [email protected]

More Information Chief Physician of the Department of “Gynecology and Obstetrics” at Waldfriede Hospital

Dr. med. Jürgen Schaff

www.drschaff.de

Range of Medical Services Male-to-female feminization surgery, feminizing breast surgery, facial feminization.

More Information

- 1988 Beginning of specialization in surgery of transsexuality

- Medical practice at the Klinikum Rechts der Isar TU Munich until 1994

- Chief physician at Amperklinikum Dachau until 2004

- Head physician Red Cross Clinic Munich and Praxisklinik until 2019

- 2006 Foundation of the Quality Circle Transsexuality in Munich with Dr. Werner Ettmeier, 3-4 events per year

- 2008 Foundation of a symposium for transsexual surgery, annual events at different locations

- Foundation of the Working Group Transsexuality of the German Society of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons

- Expert witness for transgender surgery

- Live surgeries at several hospitals in Germany and abroad

- Development of several new surgical techniques and surgical standards

- German Society for Surgery

- German Society of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (DGPRÄC)

- Association of German Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (VDÄPC)

- Interplast Germany

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)

Priv.-Doz. Dr. med. Andreas E. Steiert

www.steiert.berlin

Specializations Surgery of transsexuality

Range of Medical Services Plastic surgery and microsurgery with a focus on gender reassignment surgery female-to-male and male-to-female

Contact / Consultation Hours Sprechstundenzentrum Potsdam Helene-Lange-Straße 11 14469 Potsdam ✆ +49 (0) 331 280 87 200 🖷 +49 (0) 331 280 87 209 📧 [email protected]

More information General surgery training at the Charité and the RWTH-Aachen.

Publications: Author of numerous publications on various topics in internationally renowned journals:

- Aesthetic Surgery Journal (Official Journal of The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery).

- Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Journal (Springer-Verlag)

- Journal of Biomedical Materials Type A

- Journal of Surgical Research

- Medical Devices

- Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery

and is the author of several book chapters, including “Facelift” in “Praxis der Plastischen Chirurgie, edited by Prof. Peter M. Vogt, Springer Verlag.

10/2001 Clinic for Plastic, Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Hanover Medical School Univ.-Prof. Dr. P.M. Vogt

06/2007 Appointment as senior physician of the clinic Clinic for Plastic, Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Hanover Medical School Univ.-Prof. Dr. P.M. Vogt

04/2011 Appointment as Managing Senior Physician of the Clinic, Deputy of the Clinic Director Clinic for Plastic, Hand and Reconstructive Surgery, Hanover Medical School Univ.-Prof. Dr. P.M. Vogt

12/2012 Additional qualification in hand surgery

09/2015 Habilitation Award of the Venia Legendi for Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery

- International Confederation for Plastic Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery (IPRAS)

- German Society for Senology (DGS)

- German Society for Surgery (DGCH)

- Professional Association of German Surgeons (BDC)

Contact our transgender division

- What We Treat

- Consultation Center

- Anesthesiologists

- Physician Assistants

- Contact People

- [email protected]

- TEL 0331 – 280 87 0 FAX 0331 – 280 40 86

- Klinik Sanssouci Potsdam Helene-Lange-Straße 13 14469 Potsdam

© 2024 Klinik Sanssouci. Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Datenschutz

Please choose the relevant department and send us a message..

Appointment request with* Dr. med. Bernd Dreithaler Dr. med. Holm Edelmann Prof. Dr. med. Peter Hertel Dr. med. Joh.-Stephan von Ruediger Dr. med. Jürgen Schaff Prof. Dr. med. Markus Scheibel

Not sure who the right contact person is?

DIRECTO EN INSTAGRAM: 26 de junio, a las 19 h, "Hablemos de cirugía de afirmación de género" con el Dr Ivan Mañero. / 3 de julio, a las 13h, "Sexualidad después de la vaginoplastia" con la Dra. Labanca.

WORLD LEADER IN GENDER REASSIGNMENT SURGERY

The most advanced clinic in Europe

Gender reassignment surgery, what is gender reassignment surgery.

Gender reassignment surgery, confirmation surgery or sex reassignment surgery means a variety of procedures that allow people transition to their self-identified gender. These surgical treatments modify a physical person’s appearance and sexual characteristics to approach their identified gender.

The most common treatments are feminization surgeries are vaginoplasty, breast augmentation or facial aesthetic procedures. In the cases FTM, phalloplasty, breast reduction or facial masculinization operations are the most demanded surgeries.

Our gender affirming treatments and procedures

We offer a wide range of gender confirmation procedures to help our patients to achieve the results they are looking for, supporting and providing professional advice throughout the transformation process.

Feminisation surgery

MTF Vaginoplasty

Facial feminization

BREAST AUGMENTATION

MTF body surgery

FEMINIZING VOICE SURGERY

AESTHETIC MEDICINE

Masculinisation surgery.

Phalloplasty

Metoidioplasty

FTM top surgery

FTM Hysterectomy

Body Masculinization

OTHER MASCULINIZATION

Before and after gender-affirming surgery results.

Knowing the results of some sex reassignment surgeries could be helpful to make a decision and to have an idea about what to expect.

Dr. Ivan Mañero, a reference

Dr. Ivan Mañero, reconstructive and aesthetic plastic surgeon, is an international leader in gender affirmation surgery (ies) for trans people. He has been performing and perfecting gender reassignment surgeries for more than two decades, both inside and outside our borders.

His professionalism has led him to be internationally known and sought after, participating and moderating events in conferences. From the beginning of his professional career, he has always advocated for specialized and sensitive care for trans people. However, in the beginning, he had to deal with other peers who did not understand why a specialist like him cared about this matter.

A pioneer in unique surgical techniques for gender reassignment, Dr. Ivan Mañero has collaborated with various administrations to ensure that this type of a surgeries re included within the public health service in Spain. . In order to be able to offer greater and better care to trans people who require it.

The IM GENDER team, led by Dr Ivan Mañero, is a leading international reference in sex reassignment surgery and genital reassignment surgery.

World leader in gender reassignment surgery

The IM GENDER Gender Unit opened its doors over twenty years ago and has become an international benchmark in Gender Reassignment Surgery. IM GENDER has cared for more than 3,000 trans people who have decided to carry out some treatment or surgical procedure at the Unit, whether genital affirmation surgery – vaginoplasty, phalloplasty, metoidioplasty -, body surgery – mastectomy, breast augmentation, feminizing liposculpture, among others -, facial surgery – facial feminization, thyroplasty, masculinization of features, etc.- or other plastic surgery procedures.

IM GENDER offers all the advantages of IM CLINIC, a pioneering clinic for its concept of understanding healthcare in a global and personalized way. Our clinic confers differentiating characteristics that allow us to offer a high quality of care.

At IM GENDER you will find a clear commitment to the most cutting-edge and reliable technology, with technologically cutting-edge operating rooms and the most innovative equipment in the sector. All this, added to a medical team expert in gender surgery with more than two decades of experience led by Dr. Ivan Mañero, the most recognized plastic surgeon specialized in gender reassignment surgery in Europe and even internationally. In addition, Dr. Mañero was a pioneer in unique/specific surgical techniques for genital affirmation, such as vaginoplasty with graft.

The entire human team that makes up IM GENDER, from Patient Care to medical, health professionals, psychologists and physiotherapists, are trained in health care based on human rights, respect and privacy of all patients. Our goal is to offer all the necessary information before, during and after the surgery through close treatment and personalized attention.

YEARS OF EXPERIENCE

Im gender specialists.

THEIR EXPERIENCE COULD BE YOURS

Meet IM GENDER’s true stars and learn about their personal experiences, from preoperative consultations to postoperative follow-up care. Discover how our comprehensive approach to gender-affirming surgery, (ies) coupled with our psychological support and family guidance, has made a difference in their lives.

At IM GENDER, we understand that every patient’s journey is unique, and we are committed to providing personalised care that caters to individual needs. Our testimonials are a testament to our dedication to patient satisfaction, and we are proud to share the stories of our satisfied clients with you.

We invite you to explore our website and learn more about our services, team, and testimonials. Our team is available to answer any questions or concerns you may have and to help you start your journey towards gender affirmation.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT

Type of consultation: Physical appointment Online consultation

I read and accept the privacy law

IM CLINIC FACILITIES

IM GENDER is the Gender Unit at IM CLINIC, one of the most advanced sex reassignment surgery centers Internationally. A new concept of clinic born from our commitment to experience in the field. IM GENDER is a team of highly qualified professionals, who all believe in the same philosophy of exquisite patient care.

Prepare for your surgery

(18 years in Spain)

Are you 18 years or older?

Home - Transgender

Transgender – sex reassignment surgery

When a person cannot identify with the gender assigned at birth, that person’s status is referred to as transgender (formerly transsexuality). Primarily, transgender is not a problem per se, but simply the certainty of feeling you belong to a sex other than the one assigned to you, or to neither, and the wish to be acknowledged in that affiliation both socially and juridically. There are a number of possible gender identities that come under the umbrella term ‘trans’ or stand alone. Ultimately, each of them is a very individual, alterable identity. The road to sex reassignment has now been smoothed, though it does still feature some bureaucratic hurdles. Talk to us about it. We’ll help you find your own individual way forward, and we’ll be at your side to advise you. Given that the medical services at the place where they live are often limited, many transident individuals are prepared to travel long distances, sometimes even going abroad, to adapt their phenotype, though the aftercare in such cases may not necessarily be assured to an appropriate degree. If you have already had surgery, we can offer post-operational care here at the practice and will advise you if there are any complications. In Germany, the diagnosis of the transgender characteristic is geared to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and associated health problems (ICD – transsexualism according to ICD F64.0) issued by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Many transgender and non-binary individuals feel hurt when their gender feeling is classified as a disease or disorder. However, categorisation in ICD-10 and recognition as a disease pursuant to SGB V (Book V of the German Social Security Code) do at least have the advantage for those concerned that the health insurance providers meet the costs for diagnostics and treatment once the diagnosis has been confirmed. If you are considering applying for the costs of sex reassignment surgery to be borne by your statutory health insurance provider, there are as a rule some conditions that need to be fulfilled. Having said that, we would like to draw your attention to the fact that in our practice clinic we cannot perform any operations with reimbursement for out-patient care services as defined by the statutory health insurance providers (on the so-called standard assessment scale [EBM]). In individual cases, however, you may be able to come to a special agreement with your provider. For direct payers and privately insured patients, (depending on their individual contract profile), these restrictions do not apply. As a rule, paramount to sex reassignment surgery is the removal of the protruding chest with the aim of adapting to an appearance that corresponds to the patient’s gender perception, or the construction of a protruding chest. A chest that does not fit in with the person’s sexual identity often constitutes the greatest visible stigma for the patient. Which surgical procedures are suitable in your particular case depends on your initial findings. We can offer you either realignment to a flat chest for trans people assigned female at birth (AFAB), or the creation of a protruding chest for trans people assigned male at birth (AMAB). We can perform all the operations that are necessary to achieve an optimum result for you, so that you can get just that little bit closer to your long awaited goal of uniting your body with the way you feel. We work together with a network of microsurgeons, gynaecologists, urologists and endocrinologists who will also advise and assist you. In a detailed consultation, we can talk about the gender reassignment measures which will achieve the result that is best for you.

FAQs on the law on self-determination with regard to gender entry (SBGG)

The Self-Determination Act, which was passed by the German Bundestag on 12 April 2024, is intended to make it easier for transgender, intersex and non-binary people to change their gender entry. The website of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ) provides an overview of the most important FAQs on the draft law. Find out more here.

Ask our advice.

We’ll be glad to provide you with detailed information about this treatment. Simply get in touch with us now and obtain advice at an individual and absolutely personal level. +49 30 - 94 041 144

Wolff & Edusei Practice Clinic

Specialist practice for plastic and aesthetic surgery Taubenstraße 26 10117 Berlin (Mitte)

- +49 30 - 94 041 144

- [email protected]

Follow us on Social Media

Site notice | Privacy policy

- Testimonials

- Book a Botulinal toxin consultation

- Botulinal toxin

- Hyaluronic acid

- Biostimulation

- Thread lift

- Chemical skin peel

- Lipofilling

- Surgical needling

- Dermabrasion

- Breast correction

- Breast removal

- Breast lift

- Breast augmentation by fat transfer

- Breast augmentation with implants

- Breast reduction

- Nipple correction

- Breast reconstruction

- Breast operations for him

- Labial reduction

- Correction of the mons pubis

- Transgender

- Eyelid lift

- Volume replenishment

- Facial injuries

- Hair transplantation

- Abdominal wall lift

- Liposuction

- Buttock lift

- Upper arm lift

- Excessive perspiration

- Skin alterations

- Microsurgical scar correction

- FAQ Breast surgery

- FAQ Breast augmentation

- FAQ Breast reduction & breast lift

- FAQ Tubular breast deformity

- FAQ Breast implants

- FAQ Intimate surgery

- FAQ Beauty & Wrinkle Injections

- FAQ Anesthesia

- FAQ Gender reassignment

- Make an appointment on line Dr. med. Andrea Wolff

- Make an appointment on line Dr. med. Isabel Edusei

- Book an appointment for your botulinum toxin and glow consultation!

Online appointments

You can make an appointment on line at any time quickly and easily via the free ‘Doctolib’ doctor booking platform.

Contact form

Outside our opening hours, you can also get in touch with us via our contact form. We will get back to you as soon as possible.

Terminvereinbarung online

Über die Arzt-Buchungsplattform »Doctolib« können Sie jederzeit schnell, einfach und kostenlos einen Termin online vereinbaren.

Kontaktformular

Our Response to COVID-19 →

Medical Tourism

Best countries in the world for gender reassignment surgery.

Gender reassignment surgery (GRS) is a life-changing medical procedure that can help individuals align their physical appearance with their gender identity. Across the globe, various countries have gained recognition for offering top-notch GRS procedures, comprehensive healthcare, and experienced medical professionals. In this article, we will delve into the best countries in the world for gender reassignment surgery, shedding light on the remarkable destinations where individuals can embark on their transformative journey.

Thailand: Pioneering Excellence

Thailand has earned a reputation as a pioneer in gender reassignment surgery. Renowned for its world-class medical facilities and a cadre of skilled surgeons, Thailand offers a safe and comfortable environment for individuals seeking GRS. The country's medical tourism infrastructure is well-developed, with Bangkok serving as a hub for transformative surgeries.

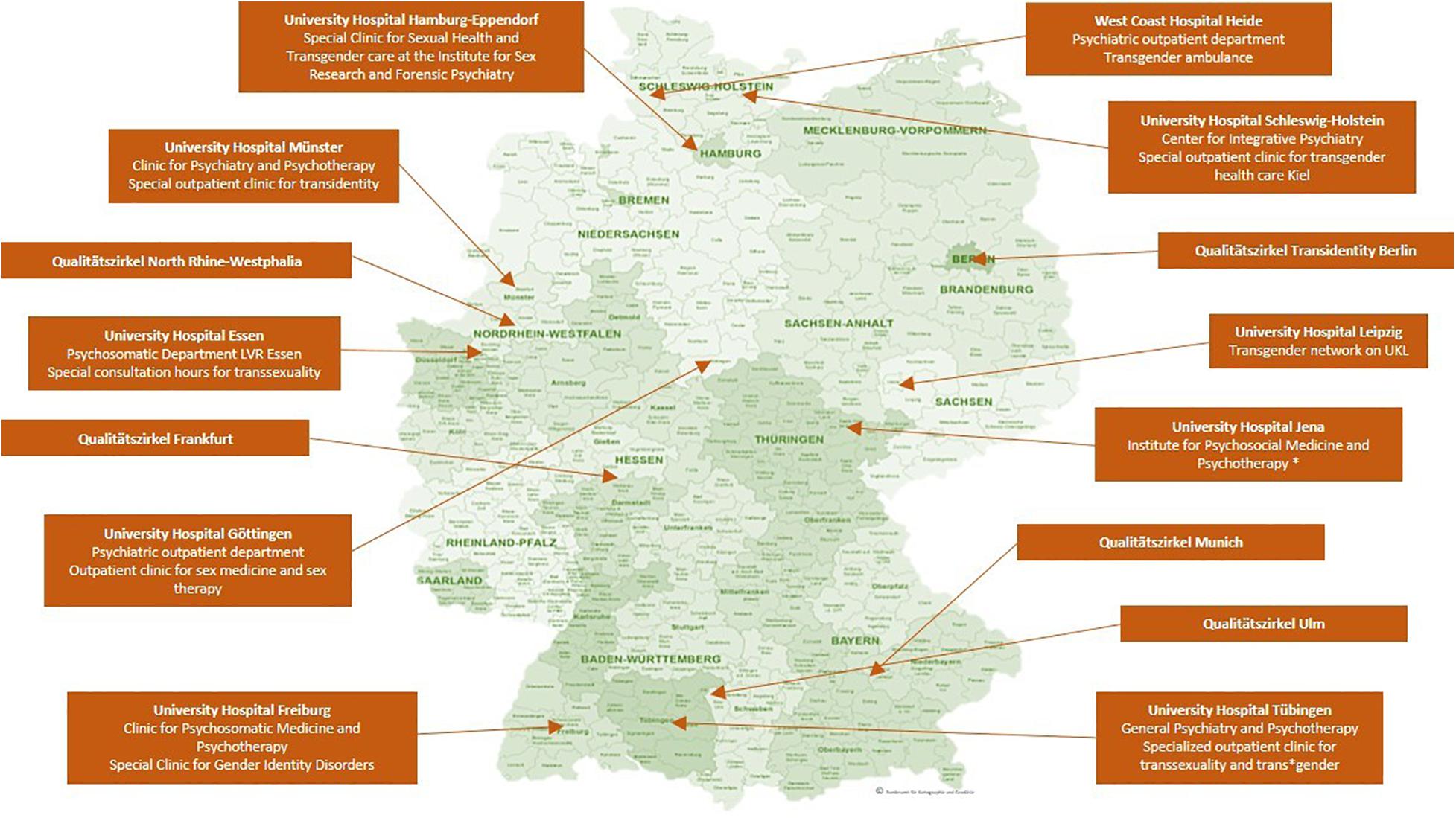

Germany: Leading the Way in Europe

Germany stands out as a prominent European destination for gender reassignment surgery. The country boasts cutting-edge technology, rigorous medical standards, and an array of experienced surgeons. Berlin, in particular, is recognized for its excellence in GRS procedures, drawing patients from around the world.

United States: A Hub of Expertise

The United States, with its vast healthcare network and innovative medical centers, remains a popular choice for gender reassignment surgery. Cities like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles have world-renowned gender clinics that offer a wide range of procedures and comprehensive care.

Canada: A Compassionate Approach

Canada's inclusive healthcare system and commitment to LGBTQ+ rights make it a compassionate choice for gender reassignment surgery. Major cities like Toronto and Vancouver provide access to skilled surgeons and supportive medical facilities, ensuring patients receive top-tier care throughout their journey.

Brazil: Combining Beauty and Expertise

Known for its stunning landscapes and a reputation for cosmetic surgery, Brazil also shines in the realm of gender reassignment surgery. The country boasts experienced surgeons who are well-versed in GRS procedures, making it a sought-after destination for those seeking comprehensive transformations.

Belgium: Precision and Expertise

Belgium stands out as a hub for precision and expertise in GRS. The country's surgeons are renowned for their attention to detail, ensuring the best possible outcomes for patients. Brussels, the capital, is a prominent location for gender reassignment surgeries.

India: Affordable Excellence

For those seeking affordability without compromising on quality, India emerges as a viable choice for gender reassignment surgery. The country offers world-class medical facilities, experienced surgeons, and competitive pricing, making it an attractive option for international patients.

Argentina: Advocating Inclusivity

Argentina has made significant strides in advocating for LGBTQ+ rights and gender-affirming healthcare. Buenos Aires, in particular, boasts a thriving transgender community and skilled medical professionals who specialize in gender reassignment surgery.

South Korea: Excellence in Aesthetic

South Korea, renowned for its expertise in aesthetic procedures, has also gained recognition in the field of gender reassignment surgery. The country's commitment to precision and advanced medical techniques makes it a standout destination for those seeking facial feminization surgeries and other GRS procedures.

Embarking on a gender reassignment journey is a profound and life-changing decision. Choosing the right destination for gender reassignment surgery is crucial for ensuring a safe, supportive, and successful experience. The countries mentioned in this article have distinguished themselves as some of the best in the world for GRS, offering exceptional medical facilities, skilled surgeons, and inclusive environments where individuals can achieve their desired transformations. Before making a decision, it is essential to conduct thorough research, consult with healthcare professionals, and consider personal preferences and needs. Ultimately, the journey towards aligning one's gender identity with their physical appearance should be met with understanding, compassion, and excellence in medical care.

To receive a free quote for this procedure please click on the link: https://www.medicaltourism.com/get-a-quote

For those seeking medical care abroad, we highly recommend hospitals and clinics who have been accredited by Global Healthcare Accreditation (GHA). With a strong emphasis on exceptional patient experience, GHA accredited facilities are attuned to your cultural, linguistic, and individual needs, ensuring you feel understood and cared for. They adhere to the highest standards, putting patient safety and satisfaction at the forefront. Explore the world's top GHA-accredited facilities here . Trust us, your health journey deserves the best.

Unveiling the Power of Social Media Marketing in Medical Tourism

Korea: turning the focus to an emerging global leader in medical tourism, exploring the surge of cosmetic tourism: trends and considerations in aesthetic procedures abroad, holistic healing: exploring integrative medicine and wellness retreats, meeting the surge: the growing demand for knee replacement surgeries and advances in the field, bridging culture and care: insights from dr. heitham hassoun, chief executive of cedars-sinai international, mastercard and the medical tourism association join forces to revolutionize cross-border healthcare payments, in pursuit of excellence: ceo spotlight with ms. artirat charukitpipat, stem cells show promise for hair thickening, stem cell injection for back and neck pain, continue reading, south korea, a medical tourism leader pioneering the future of medicine , best countries for stomach cancer treatment: a global perspective, ponderas academic hospital: elevating medical tourism with jci accreditation and personalized care, featured reading, medical tourism magazine.

The Medical Tourism Magazine (MTM), known as the “voice” of the medical tourism industry, provides members and key industry experts with the opportunity to share important developments, initiatives, themes, topics and trends that make the medical tourism industry the booming market it is today.

- For authors

- Ärztestellen

- English Edition

Review article

Hormonal gender reassignment treatment for gender dysphoria, meyer, g ; boczek, u ; bojunga, j.

- Figures & Tables

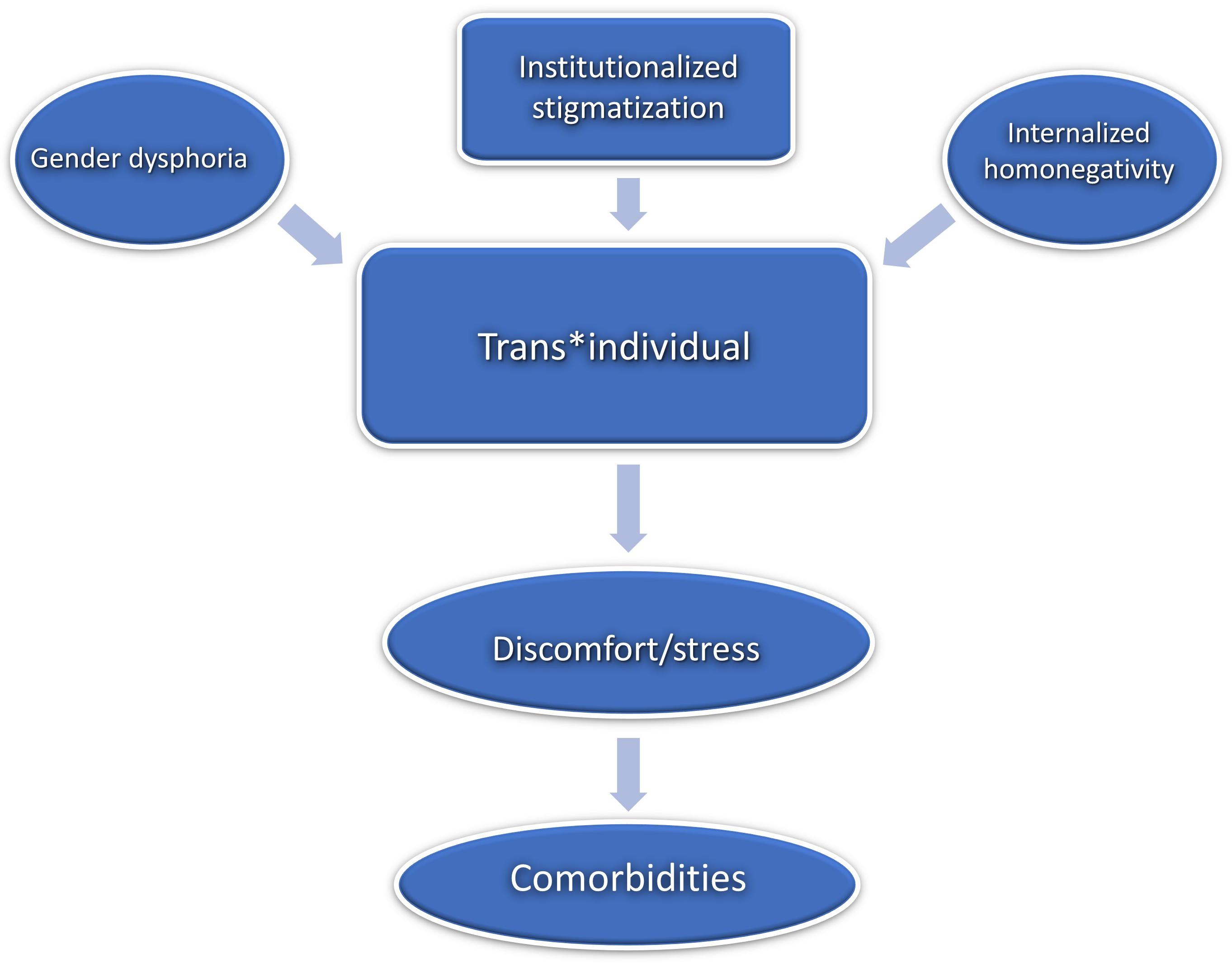

Background: No data are available at present on the prevalence of gender dysphoria (trans-identity) in Germany. On the basis of estimates from the Netherlands, it can be calculated that approximately 15 000 to 25 000 persons in Germany are affected. Persons suffering from gender dysphoria often experience significant distress and have a strong desire for gender reassignment treatment.

Method: This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search in the PubMed database employing the searching terms “transsexualism,” “transgender,” “gender incongruence,” “gender identity disorder,” “gender-affirming hormone therapy,” and “gender dysphoria.”

Results: In view of its far-reaching consequences, some of which are irreversible, hormonal gender reassignment treatment should only be initiated after meticulous individual consideration, with the approval of the treating psychiatrist/psychotherapist and after extensive information of the patient by an experienced endocrinologist. Before the treatment is begun, the patient must be extensively screened for risk factors. The contraindications include severe preexisting thromboembolic diseases (mainly if untreated), hormone-sensitive tumors, and uncontrolled preexisting chronic diseases such as arterial hypertension and epilepsy. Finding an appropriate individual solution is the main objective even if contraindications are present. Male-to-female treatment is carried out with 17β-estradiol or 17β-estradiol valerate in combination with cyproterone acetate or spironolactone as an antiandrogen, female-to-male treatment with transdermal or intramuscular testosterone preparations. The treatment must be monitored permanently with clinical and laboratory follow-up as well as with gynecological and urological early-detection screening studies. Prospective studies and a meta-analysis (based on low-level evidence) have documented an improvement in the quality of life after gender reassignment treatment. Female-to-male gender-incongruent persons often have difficulty being accepted in a gynecological practice as a male patient.

Conclusion: Further prospective studies for the quantification of the risks and benefits of hormonal treatment would be desirable. Potential interactions of the hormone preparations with other medications must always be considered.

Gender dysphoria—or gender incongruence or transsexuality–is characterized by a mismatch between the biological sex and the inner sense of gender (gender identity). A transgender woman is a biologically male person with female gender identity; correspondingly, a transgender man is a biologically female person with male gender identity. In the Netherlands, the prevalence of gender dysphoria is estimated to be 0.02–0.03% ( 1 ). For Germany, no estimates have yet been published. Based on the above figures, it can be assumed that approximately 15 000 to 25 000 people are affected. While earlier studies ( 1 , e1 , e2 ) reported a gender ratio of transgender women to transgender men of approximately 2 : 1, more recent studies found increasingly similar proportions ( e3 ) or even a reversal of this ratio ( 2 ).

With the onset of puberty, transgender persons typically experience significant psychological distress (gender dysphoria) and consequently seek gender-affirming—or gender reassignment—treatment ( e4 ). With 9% to 11% and 1.5% to 2%, the rates of suicide attempts ( 3 ) and committed suicides ( 4 ), respectively, are increased among people with gender dysphoria compared to the general population. In 2010, a meta-analysis found a decrease in mental and physical complaints as well as an increase in quality of life after the start of gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) ( 5 ), but the data quality of this study was limited. However, later prospective studies confirmed these findings ( 6 , e5 ). The two-year follow-up after GAHT revealed the following differences compared to the pre-treatment status:

- Decrease in depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI] II scores: transgender women −1.41, p<0.001; transgender men −1.31, p<0.001)

- Reduction in body uneasiness (Body Uneasiness Test [BUT] index: transgender women −0.24, p<0.001; transgender men −0.24, p = 0.001)

- Decrease in gender dysphoria (GIDYQ AA score: transgender women −0.06, p 6 ).

For persons with gender dysphoria, treatment with cross-sex hormones delivers a sense of identity. However, since gender-affirming hormone therapy has a significant effect on a person’s hormonal balance, it is associated with a risk of adverse effects which is particularly high in the event of unsupervised treatment or overdosing.

Using treatment data from a large Dutch gender identity clinic collected in the period from 1980 to 2015, Wiepjes et al. demonstrated a 20-fold increase in newly started GAHT ( 1 ). Similarly, many treatment providers in Germany have observed an increase in the number of affected persons in recent years (personal communication from colleagues of other institutes). Factors potentially contributing to this trend include growing societal acceptance and a significant increase in public attention and media coverage ( e6 , e7 , e8 , e9 , e10 ). Nevertheless, in Germany, too, those affected do frequently not receive optimal care ( 7 , 8 , e4 , e11 ).

The aim of this article is to provide up-to-date insights into and recommendations for gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) as well as information about special aspects that should be taken into account by general practitioners and specialists involved in the care of transgender persons.

Overall, the evidence from studies on the effects and risks of GAHT—which also forms the basis of the guidelines of the Endocrine Society which were initially created under US and European co-authorship in 2009 and then updated in 2017 ( 9 )—is weak. Most studies are retrospective data analyses, frequently based on comparatively few cases. Prospective studies are scarce. There are no randomized controlled trials and, ultimately, it is difficult to imagine that studies designed will ever be conducted, not least for ethical reasons. A German or European guideline on GAHT has not yet been created.

This review is based on a selective search of the PubMed database for original publications and review articles up to December 2019. The following search terms were used: “transsexualism”, “transgender”, “gender incongruence“, “gender identity disorder“, “gender affirming hormone therapy“, “gender dysphoria”.

Requirements

Treatment with GAHT quickly causes marked and partly irreversible changes. Thus, prior to the start of treatment, it is critical to confirm the diagnosis and to ensure that a clear, written indication for GAHT is established by a psychotherapist or psychiatrist ( 9 , 10 , 11 , e12 ). There are no strict requirements for the duration of preceding psychotherapy and, given the very different circumstances and needs of the affected individuals, any such requirement may not be helpful after all.

GAHT can be started at about age 16 years, provided a written, documented informed consent is obtained from the adolescent’s parents or guardian and the adolescent is mature enough to make this decision. In gender-dysphoric younger children and adolescents, a reversible puberty-suppressing therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs can be initiated with the onset of puberty ( 9 ). In minors, confirmation of the indication by an independent second therapist should be required ( 9 ). Prior to the initiation of treatment, the patient must be informed in detail about the treatment effects, their course over time, the limitations of the treatment and potential adverse effects ( 9 , 10 ).

Medical diagnostic work-up prior to treatment initiation

A comprehensive pre-treatment risk screening, including thorough medical history, family history and physical examination as well as clinical chemistry testing of relevant parameters is required to identify potential contraindications and risk factors. This screening also helps to adapt the planned treatment to a patient’s individual risk profile (Box).

Many healthcare payers require that a somatic variation of sex development is ruled out before treatment is started ( e13 ). These differential diagnostic conditions, such as Klinefelter syndrome and complete androgen resistance syndrome, are rare and can be excluded based on the medical history, physical examination and measuring of basal hormone levels. Only in the presence of major clinical abnormalities and grossly abnormal laboratory findings, further diagnostic work-up, including chromosomal analysis, should be performed.

Pre-existing conditions, such as arterial hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and HIV, require adequate treatment. Adequately controlled, they are not considered absolute contraindications. In the presence of elevated liver enzyme levels, a pre-existing hepatic condition should be ruled out. Further diagnostic testing may be required.

GAHT is so essential for patients with gender dysphoria that priority even over contraindications can be given to this treatment on an individual basis after detailed discussion of associated risks. The decision to provide the treatment should also be broadly supported by all clinicians involved in the patient’s care. Absolute contraindications are very rare. Unsupervised self-medication is associated with high risks. Thus, instead of withholding therapeutically controlled hormone treatment in patients with contraindications, ideally an experienced endocrinologist should carefully evaluate each case individually to find a personalized solution.

Male-to-female gender dysphoria

Treatment recommendations

GAHT of male-to-female transsexuals is based on the oral or transdermal administration of 17ß-estradiol or 17ß-estradiol valerate ( 9 ). Because of the significantly more unfavorable risk profile, treatment with ethinyl estradiol is obsolete ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). Since thromboembolic complications are more common with oral estradiol treatment ( 15 ), preference is given to the transdermal route of application if additional risk factors, such as overweight, older age and smoking, are present.

Since reducing androgen levels is another important requirement for the desired feminization of the body ( 16 , e14 ), patients also receive supplementary anti-androgen therapy. Here, the standard treatment is the administration of cyproterone acetate ( 17 ). Alternatively, treatment with spironolactone may be considered. Administration of a GnRH analog is another treatment option, but the significantly higher costs of this approach need to be taken into consideration. Anti-androgen treatment is discontinued, at the latest, once orchiectomy has been performed as part of the gender-affirming surgical procedure. An additional benefit on breast development by supplemental progesterone treatment has not yet been confirmed ( 18 , 19 ). There is a lack of randomized controlled trials evaluating this aspect. Given the increased risk of breast cancer and thromboembolic events associated with hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women ( e15 ), additional administration of progesterone in transgender women is currently not recommended ( 9 ). Information about the medications used for GAHT and their standard dosing schedules is provided in Table 1.

Course and limitations of treatment

Table 2 gives an overview of the course of treatment over time and its limitations. GAHT cannot alter the size and shape of the male larynx and consequently the pitch of the voice. While body and facial hear growth are diminished, they usually do not stop completely; consequently, epilation treatment is required in most cases.

Adverse reactions and risks

Table 3 gives an overview of adverse reactions and risks. The development of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a relevant risk. Older, retrospective data from the time when ethinyl estradiol (today considered obsolete) was still commonly used show a significant increase in the risk of thromboembolism with the occurrence of a VTE in 5.5% to 6.3% of ethinyl estradiol-treated patients ( 12 , 20 ). With the advent of modern treatment regimens, the prevalence of VTEs has declined to about 0.6% to 2% ( 21 , 22 ). To date, no studies evaluating the perioperative risk of thromboembolism have been conducted in patients receiving feminizing hormone therapy. Studies investigating this risk in postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy found heterogeneous results ( e16 , e17 , e18 ). Transdermal estradiol therapy without co-administration of progestin appears to be no significant additive risk factor in this patient population. The potential negative effect of temporarily discontinuing GAHT on mind and body, the risk profile and the treatment used have to be taken into consideration when making recommendations on the perioperativen management of GAHT ( 23 ). Most treating clinicians currently recommend to discontinue the hormone therapy for two weeks prior to scheduled surgical interventions ( 24 ).

Occasionally, weight gain of 3 to 4 kg, on average, is observed ( 25 , 26 ). In addition, older studies showed an increase in triglycerides ( 26 , 27 ) from 76 mg/dL to 128 mg/dL, on average, (p 12 ). When transdermal estradiol formulations are used, unfavorable changes in these laboratory parameters are significantly less common ( 27 ) or levels even decrease to the female reference range ( 17 ).

Long-term data on cardiovascular risk are scarce. However, a recent study found an increased occurrence of cerebral ischemia in transgender individuals receiving GAHT compared to age-matched women (2.4-fold risk increase) and men (1.8-fold risk increase) ( 28 ). The rate of myocardial infarction was higher compared to biological women but comparable with the rate in age-matched men ( 28 , 29 ). From about age 50 years onwards, it is recommended to reduce the estradiol dose, mimicking the normal age-related hormonal changes ( 30 ). Nevertheless, it may be useful to continue treatment with a low maintenance dose beyond the statistical age of menopause to preserve bone density ( 31 ). If additional risk factors for osteoporosis are present and especially in the rare cases where GAHT is not continued after orchiectomy, e.g. because of contraindications, it is recommended to measure bone density using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) ( 9 ). However, the costs of DXA for this indication are not covered by German statutory health insurance funds.

While, especially in patients receiving high doses of estradiol, mild increases in prolactin levels are common and considered acceptable, relevant increases of prolactin levels >2x ULN may require an adjustment of the estradiol dose, once functional causes of hyperprolactinemia (e.g. preceding palpation of the breast) have been ruled out. If elevated levels persist, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary gland should be performed since isolated cases of prolactinoma have been reported among patients receiving long-term high-dose estradiol therapy ( 32 ). In a recent Dear Doctor letter (“Rote-Hand-Brief”), a dose-dependent increase in the risk of meningioma occurrence has been described for patients treated with cyproterone acetate.

GAHT leads to testicular atrophy and over the course of treatment potentially to irreversible infertility ( 33 ). Information about theses consequences of the therapy and the options for preserving fertility (eBox) should be an integral part of the informed consent discussion.

Female-to-male gender dysphoria

Gender-affirming hormone therapy of female-to-male transsexual persons is based on testosterone administered as a transdermal gel or intramuscular depot preparation. A progestin can be added temporarily to the regimen to suppress menstruation until adequate suppression of the gonadotropic axis is achieved by testosterone ( 9 ). Progestin preparations need to be taken very regularly to ensure reliable menstrual suppression. Typically, treatment is started with a low dose taken once daily. If this is not successful, the dose can be increased to twice daily or, alternatively, a GnRH analog may be used. Further information about the preparations used and the recommended doses is presented in Table 1.

Table 2 gives an overview of the course of treatment over time and its limitations.