Economic Synopses

Comparing the covid-19 recession with the great depression.

The COVID-19-induced U.S. recession has been frequently compared with past recessions, including the Great Depression of the 1930s. Many commentators note that the economic contraction of 2020 is the deepest since 1947, when the Commerce Department's quarterly estimates of GDP begin, and possibly since the Great Depression. The Great Depression was likely the largest and longest slump in economic activity in U.S. history, though records for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are sketchy. Comparing the 2020 recession with the Great Depression is also fraught with measurement difficulties, but some rough comparisons based on various measures of economic activity are possible.

The Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research determined that on a quarterly basis economic activity peaked in the fourth quarter of 2019; though on a monthly basis, the peak occurred in February 2020 (https://www.nber.org/cycles/main.html). The Commerce Department estimates that inflation-adjusted (i.e., "real") gross domestic product (GDP) fell at annual rates of 5.0 percent in the first quarter of 2020 and 32.9 percent in the second quarter. Though severe, the contraction apparently was relatively brief; economic activity began to increase in May or June, and most forecasters currently expect that output will increase in the second half of 2020 unless the pandemic resurges to the point of necessitating widespread business closures.

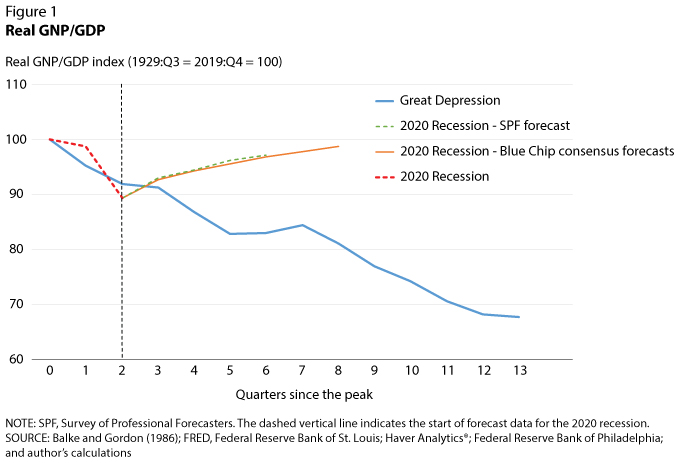

Although official estimates of GDP begin in 1947, quarterly estimates of GNP (i.e., gross national product) are available for the Depression and earlier years. 1 Figure 1 plots the real GNP series for the Depression alongside the path of real GDP from the fourth quarter of 2019 through the first two quarters of 2020. The data are set equal to 100 in the cycle peak quarters (the third quarter of 1929 and fourth quarter of 2019). The figure also plots forecasts for real GDP over the remainder of 2020 and 2021. 2 As the figure shows, the cumulative decline in economic activity during the first two quarters of the 2020 recession was somewhat larger than the GNP decline during the first two quarters of the Great Depression. Moreover, the fall in real GDP during the second quarter of 2020 exceeded the largest one-quarter real GNP contraction during the Depression. The Depression-era contraction continued for more than three years, however. At its low point in the first quarter of 1933, real GNP was just 68 percent of its 1929 peak. By contrast, consensus forecasts predict that the U.S. economy will expand in the second half of 2020 and into 2021 but that output will remain below the 2019 peak for at least several quarters.

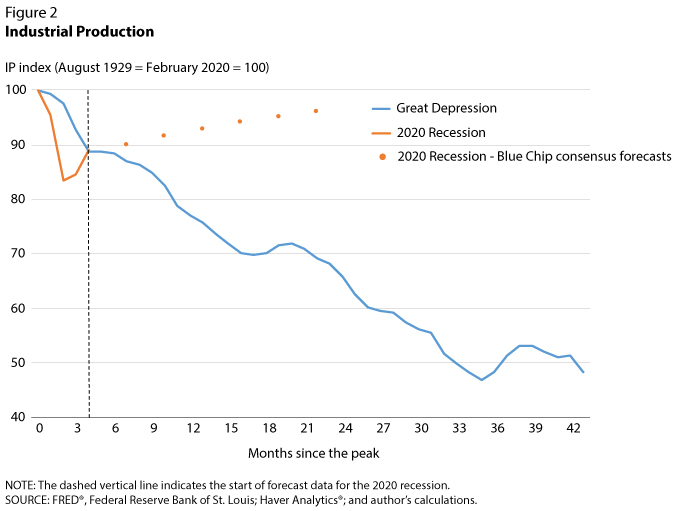

A more consistently measured, but narrower, indicator of economic activity is the Index of Industrial Production (IP). 3 The index fell sharply during the first two months of the 2020 recession, as shown in Figure 2, but then began to rise. In April the index was just 83 percent of its February level, but by June it was 89 percent of its February level. The February-to-April decline in IP was the largest two-month decline in the history of the index, which begins in 1919. The cumulative declines in IP during the first four months of the Depression and the 2020 recession were similar. Although IP continued to fall for several quarters during the Depression, forecasters currently expect that IP will rise in coming months. (The orange dots on Figure 2 indicate Blue Chip consensus forecasts. 4 )

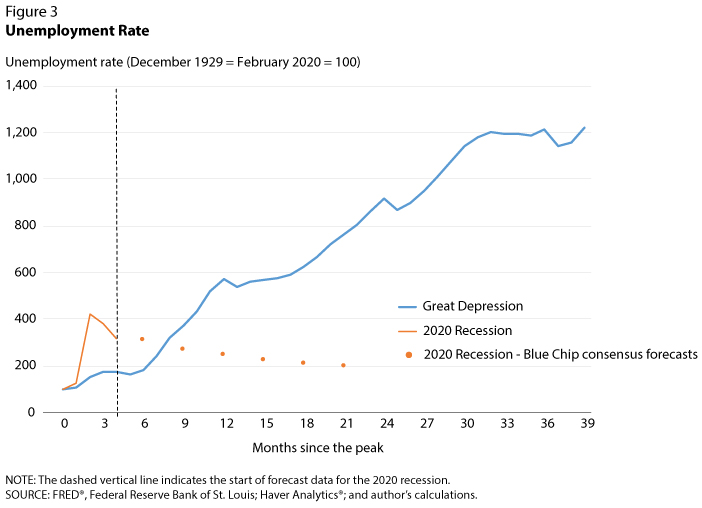

The unemployment rate increased sharply in the 2020 recession, from 3.5 percent in February to nearly 15 percent in April before falling back to 11.1 percent in June. Figure 3 compares the unemployment rate in the 2020 recession and Great Depression. 5 In contrast with the sharp rise at the beginning of the 2020 recession, the unemployment rate rose gradually during the initial months of the Great Depression, from about 2 percent in late 1929 to a bit less than 4 percent in June 1930. 6 The unemployment rate continued to rise, however, reaching 25 percent in 1933, and remained above 10 percent throughout the 1930s. 7 The Blue Chip consensus forecasts project a decline in the unemployment rate to below 10 percent by the end of 2020 and continued declines in 2021.

In addition to large declines in economic activity and employment, the price level also fell considerably during the Great Depression, as shown in Figure 4. At the business cycle trough in March 1933, the consumer price index (CPI) was 27 percent below its August 1929 level. Although the CPI fell during the first two months of the 2020 recession, it has since recovered to near its pre-recession level and is forecast to gradually rise.

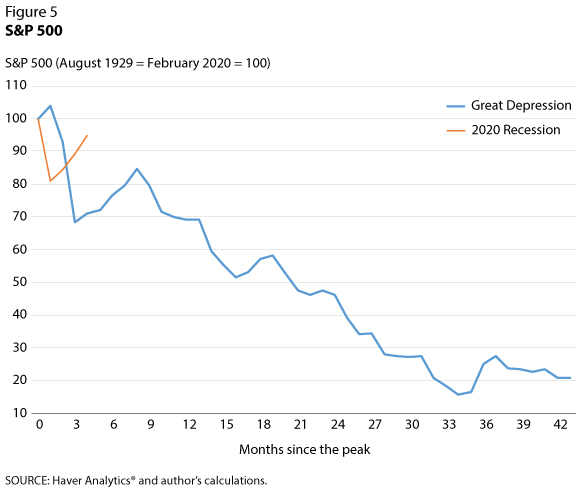

Finally, Figure 5 plots the S&P 500 (Standard and Poor's stock price index). Stock prices peaked in early October 1929 then famously crashed, plunging some 30 percent over the first three months of the Great Depression. By 1932, stock prices were down nearly 85 percent from their August 1929 level. Stock prices also fell sharply in the early days of the 2020 recession. From February to March, the S&P 500 fell some 20 percent. However, by June, it had rebounded to 94 percent of its February level.

By almost any measure, the 2020 recession began with sharp declines in economic activity, employment, and equity prices that rivaled or exceeded the initial declines of the Great Depression. The Great Depression persisted, however, and when it finally reached a trough nearly four years later, economic activity, employment, and consumer and equity prices were all far below their initial levels. The 2020 contraction might turn out to be the sharpest, but also the shortest, in modern times and perhaps of all time in the United States. The debate among forecasters has recently focused on the likely pace of the recovery and whether the increase in economic activity since May will be sustained or turn out to be merely an uptick before a second dip. The virus and the public's response to it will likely make that determination.

1 GNP is a measure of the total finished goods and services produced by U.S. producers, regardless where production takes place, whereas GDP captures total production within the United States and its territories, regardless of the nationality of the producers. The GNP estimates used here are from Balke and Gordon (1986).

2 Figure 1 plots the Blue Chip consensus forecasts for 2020:Q2-2021:Q4 (as of July 10) and the Survey of Professional Forecasters forecast for 2020:Q2-202:Q2 (as of May 15, 2020).

3 Data are from FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/INDPRO ).

4 Figure 2 assigns quarterly forecasts to the third month of each quarter.

5 The unemployment rate for the 2020 recession is the Bureau of Labor Statistics U-3 measure ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ). The rate for the Great Depression was produced by G. H. Moore for the National Industrial Conference Board ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M0892AUSM156SNBR ).

6 The monthly unemployment rate series for the Depression begins in April 1929 and is quite volatile during 1929. Consequently, we use the value in December 1929 (set equal to 100) as the starting point, rather than the value at the business cycle peak in August 1929.

7 However, if persons employed in government relief jobs are included, the rate fell below 10 percent in 1936. See Margo (1993) for a discussion of unemployment rate measures and other labor market indicators for the Depression.

Balke, Nathan and Gordon, Robert J. "Data Appendix," in Robert J. Gordon, ed., The American Business Cycle, Continuity and Change . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, pp. 781-850.

Margo, Robert A. "Employment and Unemployment in the 1930s." Journal of Economic Perspectives , Spring 1993, 7 (2), pp. 41-59.

© 2020, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLOG POST

The COVID Crisis in Comparison with the Great Depression

Price fishback .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { width: 80px important; height: 80px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { border-radius: 50% important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { background-color: #655997 important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a:hover { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-title { border-bottom-style: dotted important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-item { text-align: left important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-style: none important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { color: #3c434a important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-radius: px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul { display: flex; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul li { margin-right: 10px }.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-post-id-69046.box-instance-id-1.ppma_boxes_69046 ul li > div:nth-child(1) {flex: 1 important;}.

By Price Fishback, May 6 2020

People have been asking how the Great Depression and the New Deal compare with the current COVID-19 crisis. The economic situations are nothing alike, and the current response by U.S. governments is several orders of magnitude larger than the New Deal response to the Great Depression.

Currently, we know exactly why the economy has fallen off a cliff. To stop the expansion of a nasty disease that can lead to horrifying deaths, officials from all levels of government have required all but “essential workers” to stay at home and practice social distancing when going to grocery and drug stores. The move has “flattened the curve” and reduced transmission of the disease. As a result, economic sectors that involve face-to-face activity have mostly gone dormant, causing workers to lose work opportunities and businesses to struggle to survive.

By contrast, even now we still do not fully understand the causes of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Real output in both 1932 and 1933 was 30 percent lower than in 1929. It did not reach the 1929 level again until 1937. Unemployment rates rose from around 2 percent in 1929 to nearly 10 percent in 1930 and then stayed above 10 percent through 1940, including four years above 20 percent. We know we made policy mistakes: the Hawley-Smoot tariff, monetary policy that offered too little too late, and the 1932 tax increase that raised income taxes for the top 10 percent and added new excise taxes that hit all members of the economy. Yet, there were other factors that are not as easy to identify that contributed to such a huge drop in economic activity.

Before 1929 the populace did not ask much of the federal government. State and local governments had responsibility for labor and poverty policies. Federal government outlays were 3 percent of GDP in 1929. Few realize that Herbert Hoover’s government by 1932 had raised federal outlays to 6 percent of 1929 GDP (8 percent of a shrunken 1932 GDP) because Herbert Hoover did it within existing programs, loudly called for balanced budgets, and did not increase the outlays in his last year in office. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal then established dozens of new programs while expanding federal outlays in 1939 to 11 percent of 1929 GDP (10 percent of 1939 GDP). Most of the outlays went to poverty work relief programs like the FERA and the WPA, which paid wages of about half to two-thirds of wages paid on public works projects. As a share of lost wages, the payouts were somewhat better than modern unemployment insurance benefits, but there was a work requirement in the 1930s programs. Part of the New Deal money went to public works projects that paid full wages. About 10 percent went to payments to farmers that helped them but pushed tenants, croppers, and farm workers out of agriculture. Other programs included loan programs for farmers, homeowners, and businesses; recognition of labor unions; new financial regulations; and the National Recovery Administration’s unconstitutional attempt to allow each industry to avoid cutthroat competition by setting prices, wages, weekly hours, and quality of goods. For the long run, the Social Security Act established old-age pensions, federal matching grants for state poverty programs, and unemployment insurance. Like Hoover, Roosevelt also tried to balance the budget, and deficits as a share of GDP were lower than deficits in multiple years under Reagan, the first Bush, Obama, and Trump.

Someone recently asked me if society today has the will to call on governments to help the way they did during the New Deal. That struck me as an odd statement. Above we showed that it took ten years to raise federal outlays to rise from 3 to 11 percent of 1929 GDP. This crisis has arisen because the President, governors, and mayors in trying to save lives have ordered people to stay home and businesses to shut down. In the past few weeks, the Federal Reserve has opened up lending facilities throughout the economy in unprecedented ways. Unemployment benefits for the first time are going to workers whose employers did not contribute to the system, and the federal government is adding $600 weekly payments that raise benefits well above the usual 50 percent of the weekly wage. Finally, a sharply divided Congress and President have established 2.7 trillion dollars in spending authority in emergency packages that are raising federal outlays from about 21 percent to 34 percent of 2019 GDP. This will drive the federal deficit to from 5 to at least 18 percent of GDP, and nearly every state will run substantial deficits as well. On Thursday, Nancy Pelosi called for an additional trillion dollars in support for state and local governments. That trillion raises government outlays as a share of GDP to 39 percent, just short of the 40 percent that American spent fighting World War II at the peak of the war in 1944. The American public and leaders on both sides of the aisle today are clearly willing to allow governments to take steps that go far beyond what the New Deal government did in the 1930s. They may well soon rival federal spending at the peak of World War II.

Price Fishback is the Thomas R. Brown Professor of Economics at the University of Arizona.

RELATED CONTENT

John nye on the great depression, political economy, and the evolution of the state, reader comments.

- READ COMMENT POLICY

May 6 2020 at 12:00pm

Our government, our society has decided that we have a class of business enterprises that are “too big to fail.” Right now we are putting money behind companies like Boeing, the airlines, and the oil companies. The 1930s depression lasted a decade. I understand (a little) the academic arguments against government action, but I wonder about the cost of several years of downturn versus a quicker fix. I recognize that a certain amount of cronyism is inevitable whenever the government acts.

May 6 2020 at 1:42pm

I think that there is a mythologizing of FDR that tells a story of how he was willing to try anything to get people back to work, including by using the government to directly employ people. I think that people aren’t wondering about why people are unemployed at this moment in time, but rather are worried about how quickly the labor market will recover after the pandemic is no longer such a threat.

The experience of the very slow recovery of the labor market during the Great Recession seems to be the relevant comparison, with people worried that leaders will not make jobs and the economy their number one priority, which I think is contrasted with the folk history of the Great Depression.

Thomas Hutcheson

May 7 2020 at 11:20pm.

The common element is that the Fed failed to provide enough monetary stimulus to keep NDGP rising.

Comments are closed.

RECENT POST

The other great shutdown: opening statement..., bryan caplan .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { width: 80px important; height: 80px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { border-radius: 50% important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { background-color: #655997 important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a:hover { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-title { border-bottom-style: dotted important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-item { text-align: left important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-style: none important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { color: #3c434a important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-radius: px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul { display: flex; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul li { margin-right: 10px }.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-post-id-69046.box-instance-id-1.ppma_boxes_69046 ul li > div:nth-child(1) {flex: 1 important;}.

Here's my opening statement for last night's Soho Forum debate with Mark Krikorian. I've debated Mark Krikorian on immigration many times before, but today's crisis provides a new and gripping argument against immigration. Almost anyone can see the force of it: Coronavirus originated in China, migration brough...

Remember "Remember the Maine"?

Scott sumner .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { width: 80px important; height: 80px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { border-radius: 50% important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { background-color: #655997 important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a:hover { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-title { border-bottom-style: dotted important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-item { text-align: left important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-style: none important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { color: #3c434a important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-radius: px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul { display: flex; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul li { margin-right: 10px }.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-post-id-69046.box-instance-id-1.ppma_boxes_69046 ul li > div:nth-child(1) {flex: 1 important;}.

If you are my age, you might have been taught about how "Remember the Maine" was used as a rallying cry by the government and certain corrupt media outlets as a pretext for war against Spain. In fact, there was never any evidence that Spain attacked the Maine. About the time I was being taught about this event, ...

The COVID Crisis in Comparison with the Great Depr...

People have been asking how the Great Depression and the New Deal compare with the current COVID-19 crisis. The economic situations are nothing alike, and the current response by U.S. governments is several orders of magnitude larger than the New Deal response to the Great Depression. Currently, we know exactly why ...

The impact of coronavirus could compare to the Great Depression

And a corresponding rise in nationalism and xenophobia may follow, just as it did in the 1930s.

The coronavirus crisis will be the biggest financial crisis of our generation, much larger than the 2007-2009 global financial crisis.

It is very likely that the economic impact of the coronavirus crisis will be comparable with the Great Depression, the period of devastating economic decline between 1929 and 1939, which saw mass unemployment, factory closures and the accompanying personal trauma.

The coronavirus outbreak will bring an economic depression – that is, a severe and prolonged economic decline with high levels of unemployment and company closures.

Record numbers of people will likely suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the combination of stress, anxiety and depression that develops in some people who have experienced a traumatic event.

The coronavirus outbreak is already such an event. More than three million people around the world have been infected by the virus and more than 200,000 have died of it. Estimates show that the coronavirus may kill 100,000 Americans, the equivalent to double the number of Americans who died in the Vietnam War.

By comparison, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 infected 500 million people, or one-third of the world’s population, with 50 million deaths, of which 675,000 occurred in the US. The world’s population in 1918-1919 was estimated at 1.5 billion. If one translates this to today’s figures, with a world population of 7.8 billion, it would be the equivalent of 2.6 billion people infected and 250 million deaths.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the UN’s trade and development agency, says the slowdown in the global economy caused by the coronavirus outbreak is likely to cost at least $1 trillion in 2020 alone, in terms of reduced growth measured in gross domestic product (GDP).

Over time, the cost to the global economy is likely to be three or four times that figure.

As a comparison, it is estimated that the 2007-2009 global financial crisis cost the US around $4.6 trillion in terms of lost growth in GDP, or 15 percent of its GDP compared to the years before the financial crisis.

During the Great Depression, unemployment in many countries hovered around 25 percent, with one in four people in industrial countries made jobless by it. In the US, nearly half of the banks collapsed, 20,000 companies went bankrupt and 23,000 people committed suicide.

The current pandemic will cause individual economies to plunge into recession; businesses will close down and jobs will be lost at similar levels to that of the Great Depression. Moreover, the pandemic is impacting both industrial and developing countries; whereas the Great Depression was largely concentrated in industrial countries.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has predicted that the pandemic will wipe out 6.7 percent of working hours in the second quarter of this year – the equivalent of 195 million full-time workers.

This is already playing out. In the US, more than 22 million people filed claims for jobless benefits in the four weeks ending April 11, according to the US Department of Labour. To put these latest numbers into context, in 2008, at the height of the global financial crisis, 2.6 million people in the US filed for unemployment in that year, making 2008 the year with the biggest employment loss since 1945.

Suicides, domestic violence and murders increase during times of economic hardship and this may be further exacerbated by lockdowns and self-isolation.

Wealthier countries such as Germany, the UK and the US have rolled out large aid programmes – larger than those which appeared in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis – to support businesses, the self-employed and the unemployed for loss of income during the lockdown. Germany will give unlimited loans to large companies, pay 60 percent of salaries of troubled companies to allow them to reduce the working hours of employees without having to lay them off and financial support to the self-employed.

The US has unveiled a $2 trillion coronavirus rescue package for struggling companies and employees, which includes loans, equity stakes for government in businesses in strategic sectors and direct cash payments to individuals.

While these bailouts might provide interim relief, they will plunge countries, companies and families into debt for years, while we will also have to deal with the social crises of deaths, suicides and mental disintegration for a long time after the coronavirus pandemic.

After the Great Depression there was a rise in nationalism around the world – as a direct result of the financial, social and emotional hardships of the depression – creating the conditions that eventually led to the second world war.

There has been a similar rise in nationalism , populism and xenophobia during the coronavirus outbreak. Of course, this had been growing for many years before the pandemic, in part as a result of austerity measures that caused financial hardship in the aftermath of the 2007-2009 financial crisis.

The coronavirus crisis will likely make those austerity measures worse.

Although there have been pockets of solidarity in response to the coronavirus – Cuba sending medical personnel to Italy and China sending medical equipment to Poland, for example – some countries have stopped vital medicines, equipment and food from being exported to other countries.

Once the crisis has passed, some countries may continue turning themselves into fortresses, excluding outsiders, whether immigrants, refugees or foreign companies.

Nationalist, populist and extremist leaders and governments could ride the wave of post-coronavirus financial and emotional hardships, in the same way they did after the Great Depression. There is a real danger that the hardships caused by the coronavirus pandemic will lead to authoritarian governments coming to power in many countries, while those already in power become more entrenched.

If they do, the methods used to prevent the virus from spreading: sealing off borders, tracking infected individuals using surveillance technology and restricting people’s movements, could be used for more menacing purposes.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- West Virginia

- Online hoaxes

- Coronavirus

- Health Care

- Immigration

- Environment

- Foreign Policy

- Kamala Harris

- Donald Trump

- Mitch McConnell

- Hakeem Jeffries

- Ron DeSantis

- Tucker Carlson

- Sean Hannity

- Rachel Maddow

- PolitiFact Videos

- 2024 Elections

- Mostly True

- Mostly False

- Pants on Fire

- Biden Promise Tracker

- Trump-O-Meter

- Latest Promises

- Our Process

- Who pays for PolitiFact?

- Advertise with Us

- Suggest a Fact-check

- Corrections and Updates

- Newsletters

Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy. We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Covid-19 could be the worst economic crisis since the great depression.

Shoppers leave a Target store after shopping in Niles, Ill., on Nov. 28, 2020. (AP)

If Your Time is short

Economic crises are based on factors such as gross domestic product, unemployment rate, and duration.

COVID-19 caused the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, but the current recession is different from the recessions we’ve seen in the past 100 years.

It’s too soon to say what the long-term effects of the pandemic will be, since it is still going on.

With COVID-19 cases rising, and parts of California shutting down again, some economists say the COVID-19 recession is going to get worse.

In a Nov. 29 Facebook post, Cori Bush made her own claim about the economy. Bush, a Democrat, was elected on Nov. 3 to serve Missouri’s 1st Congressional District.

"Decades of incremental change led to a moment where we have 265K dead from COVID-19, the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, an impending climate catastrophe, & a police brutality epidemic," Bush said.

Can Bush really say that it is the worst economy since the Great Depression?

We decided not to give the statement a rating — largely because it is too soon to determine that and given the degree of uncertainty about the future. Still, we wanted to look into how the current economy compares to the past eight decades.

Bush didn’t respond to PolitiFact’s emails, so we don’t know how she defines an economic crisis. But we know COVID-19 is creating a different economic crisis than any we’ve had in the past 100 years, according to previous PolitiFact reporting .

A big factor: COVID-19 is limiting people’s ability to spend the money that many have. By contrast, MU economics professor Alina Malkova said during the Great Recession in 2008, people were running out of money or going into debt.

That recession took years to recover from. In early 2020, people had money, but they couldn’t spend it because of business closures and shut-downs.

There’s still plenty of uncertainty to when, where and how the pandemic will pass, which leaves uncertainty about the economy as well. According to Allan MacNeill, a professor of political economy at Webster University, there are two common ways to define an economic crisis.

"The two biggest things we look at for an economic crisis are the GDP decline and unemployment," MacNeill said.

Gross Domestic Product , or GDP, is the market value for goods and services within a country over a specific time period. GDP helps measure a company’s economic health.

In order to find out if the current economy is the worst since the Great Depression, we need to compare it with the Great Recession (2007-09), which before 2020 was considered to be the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. (The Great Depression lasted from 1929-1933 by some accounts, but some argue it lasted until 1939.)

The GDP decline in 2020 far exceeded the decline of the Great Recession. GDP decline in the second quarter of 2020 was 31.4%. MacNeill says this is unprecedented. According to the Federal Reserve, GDP fell by only 4.3% over the two years of the Great Recession.

The unemployment rate in April was also higher than it was during the Great Recession. In April 2020, the unemployment rate was almost 15%, while the Great Recession never went higher than 10%.

Since the GDP decline and the unemployment rate are the highest since the Great Depression, wouldn’t that make it the worst economic crisis? Well, experts say it’s not that simple.

MU economics and public affairs professor Peter Mueser says it’s hard to compare the COVID-19 economy to other recessions and crises. The Great Depression lasted about a decade, while the Great Recession spanned about three years.

In just several months, COVID-19 caused the GDP to decline by 31.4% and the unemployment rate rose from 3.5% to 14.7%. Mueser says the speed at which COVID-19 did this was unheard of.

"It has almost no comparison, in that, in that period," he said. "You know the number of people put out of work and in a short period of time, was essentially unprecedented in the U.S."

But with the unprecedented decline came an unprecedented bounceback. According to the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics report, the unemployment rate is now at 6.7%. In the third quarter, the GDP went up by 33.1%, which MacNeill says is an amazing recovery.

While the Great Recession took years to improve significantly, the COVID-19 economy is recovering in just a few months. The problem is, economists don’t know where the economy will go from here. The key unknowns are how much assistance the federal government provides to support the recovery, and how well, and how quickly, a coronavirus vaccine enables economic activities to go back to normal.

MacNeill says he hopes this crisis doesn’t last several years, but there’s a real possibility that things could get worse.

"You know, in the Great Recession, there were lots of job losses that were permanent. That wasn't that long ago, really. And this is another big hit," MacNeill said.

Mueser says if the vaccine comes out and everything continues improving within the next year, the COVID-19 economy will not be considered worse than the Great Recession, which would mean it is not the worst economy since the Great Depression, either. However, Mueser can’t rule out that the economy will take a dip again.

"I think the best guess is that we aren't going to have improvement in the next four or five months," Mueser said.

Both MacNeill and Mueser agree it's too early to call it the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. There’s simply no way of telling how long it will last.

Our Sources

Interview, Allan MacNeill, Webster University professor of Political Economy, Dec. 2

Interview, Peter Mueser, MU professor of economics and public affairs, Dec. 3

Cori Bush Facebook Page, Nov. 29 Facebook Post , Nov. 29.

Investopedia, Gross Domestic Produc t, Dec. 5

Trading Economics, United States GDP , Dec. 5

St. Louis Federal Reserve, Unemployment Rate , Dec. 5

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation Summary , Dec. 5

The Balance, US Unemployment Rate History , Dec. 5

Federal Reserve History, The Great Recession , Dec. 5

Interview, Alina Malkova, MU professor of economics, Nov. 13, 2020

PolitiFact, Vicky Hartzler Fact-Check , Nov. 18 2020

Politifact, How the 2008 and 2020 recessions will be different , Dec. 8 2020

Browse the Truth-O-Meter

More by veronica mohesky.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The fiscal and monetary response to COVID‐19: What the Great Depression has – and hasn't – taught us

George selgin.

1 Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives, The Cato Institute, USA

Although some regard the New Deal of the 1930s as exemplifying an aggressive fiscal and monetary response to a severe economic crisis, the US fiscal and monetary policy responses to the COVID‐19 crisis have actually been far more substantial – and, so far, much more effective in reviving aggregate spending. Although many fear that these responses, and the large‐scale increase in bank reserves especially, must eventually cause unwanted inflation, the concurrent sharp decline in money's velocity has thus far more than offset any inflationary effects of money growth, while forward bond prices reflect a general belief that inflation will remain below 2 per cent for at least another decade. Notwithstanding the growth of the Fed's balance sheet, Fed authorities can always check inflation by sufficiently raising the interest return on bank reserves. Nonetheless, recent developments have heightened the risk of ‘fiscal dominance’ of monetary policy at some point in the future.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Great Depression remains ‘great’ in the particular sense of holding the record for severity that every downturn since has vied for, albeit in vain. It was therefore inevitable that the sharp downturn that followed the outbreak of the COVID‐19 crisis in March 2020 would be compared to it. In April, Gita Gopinath, the IMF's Chief Economist, said it was “very likely that this year the global economy will experience its worst recession since the Great Depression” – one “far worse” than the 2009 crisis (Rappeport & Smialek, 2020 ). And recently World Bank President David Malpass observed that the current crisis is itself “truly a depression, a catastrophic event” that continues “to add to the ranks of those in extreme poverty” (New One Entertainment, 2020 ).

Just as inevitably, some have looked to the 1930s, and to the US Roosevelt Administration's New Deal especially, for ways to cope with, if not end, the present crisis. “For many Americans”, writes Harvard American Studies Professor Lizabeth Cohen, “the New Deal … remains the standard for how the federal government should respond to a major national emergency. … Many hope to replicate that achievement today.” But to do so, Professor Cohen says, “We need to know not just what [Roosevelt and his associates] did, but how they pulled it off” (Cohen, 2020 ).

Professor Cohen herself offers a very good, if brief, account of how the New Dealers ‘pulled off’ their programme. Here I wish to consider just what they did, and whether and how their successes and their failures might assist efforts to deal with today's crisis.

2. CRUCIAL DIFFERENCES

If we're to make good use of the New Deal experience in formulating or revising policy responses to the current downturn, we must first recognise that, despite some similarities, today's crisis is very different from the Great Depression. It follows that some policies that helped then may not be relevant today, whereas others may prove useful now that wouldn't have been useful then.

One especially important difference between the Great Depression and the present downturn is that today's crisis hasn't involved a collapse of the financial system. Deposit insurance has ruled out 1930s‐style bank runs, while the shoring up of bank capital ratios since 2008 has helped to reassure holders of uninsured or only partially insured deposits.

The banking system's present strength has several important implications. Most obviously it means that we've been spared a dramatic collapse of money and credit of the sort that took place in the early 1930s. To be sure, spending has collapsed, both suddenly and much more severely than it did in 2008. Yet this collapse, which has mainly been a consequence of travel restrictions and lockdowns, has still been small compared with that of the 1930s (see Figure 1 ).

Downturn and recovery in the 1930s Great Depression and the 2020 recession

Note: SPF, Survey of Professional Forecasters

Source: Wheelock ( 2020 )

Furthermore, the recovery from the present downturn is already well under way, and (as the following figures show) proceeding at an encouraging pace, whereas recovery was slow both in the 1930s and after 2008, as is often the case when downturns are caused or accompanied by financial crises. 1

An important implication of these differences is that at least one set of New Deal policies, considered by many to among be its greatest triumphs, cannot be of any use to policymakers today. I refer to the national bank holiday and steps taken during it to end banking crises and get the banking system back on its feet. Those steps marked the end of the ‘Great Contraction’ that began in 1929, and the start of a process of recovery, albeit one that would suffer many setbacks (Selgin, 2020a ).

For obvious reasons, President Roosevelt's decisions to suspend the gold standard, and, after an interval of ‘dirty’ floating, to officially devalue the dollar, which are also supposed by many to have assisted the recovery, can also have no analogues in today's world of irredeemable fiat money. Neither, for that matter, can the heavy gold inflows that occurred between 1933 and the outbreak of World War II. Yet those inflows, which were the result of European unrest rather than any New Deal measure, were the most important factor behind the post‐1933 recovery (Selgin, 2020b ).

Instead, for lessons we might fruitfully apply to today's saturation, we must look at other aspects of the New Deal, and especially at both New Deal fiscal policies and Federal Reserve credit policies. And lessons we shall find. Unfortunately, those lessons are mainly negative: if, as David Kennedy claims, “the Depression demonstrated the indispensable role of government … when it comes to dealing with the kinds of crises we face now and that we faced in the 1930s” (De Witte, 2020 ), it did so mainly by showing what happens when the government doesn't take appropriate steps. We have, in other words, more to learn from the New Deals failures than from its successes.

3. FISCAL STIMULUS

Many still suppose that the unprecedented growth in government spending, and deficit spending in particular, during the New Deal together played an important role in promoting whatever recovery took place prior to World War II. But while both total and debt‐financed federal spending did indeed increase to record levels during the New Deal, their levels were not remarkably greater than those seen during the last years of the Hoover administration (1929–33); and in both cases the deficit grew to record levels not because either government had actually embraced deficit spending (though Roosevelt's finally did so starting in 1938), but despite concerted efforts to avoid them through higher tax rates, new taxes, or both.

And while New Deal fiscal policy was indeed more expansionary than anything seen before then, as a share of GNP both total and deficit spending were very modest in comparison with recent pre‐crisis levels, let alone current ones. Indeed, the scale of New Deal government spending was, according to Christina Romer ( 1992 ), Price Fishback ( 2010 ), and other economic historians, too small to have contributed to any substantial degree to the post‐1933 recovery. Only the far greater outlays following the outbreak of World War II, which eventually raised government spending to over 44 per cent of GDP (a record still not surpassed), but which was not itself part of the New Deal's recovery programme, can truly be said to have ended the depression.

Congress's response to the present crisis has, in contrast, been both rapid and substantial. Whereas “it took ten years to raise federal outlays … from 3 to 11 percent of 1929 GDP”, Fishback ( 2020 ) observes, by May 2020 the fiscal response to COVID‐19 was already “several orders of magnitude larger than the New Deal response to the Great Depression”.

According to recent Congressional Budget Office projections, as reported by Chris Edwards ( 2020 ), the current spike in deficit‐financed outlays (see Figure 2 ) will be followed by more modest but continually rising future deficits, owing mainly to the rising cost of servicing the debt (Figure 3 ), causing the publicly held share of federal debt to surpass its previous record of 106 per cent of GDP sometime in 2023, and to approach 200 per cent of GDP by 2050.

Total US government outlays and revenues, 2005–2050 Source: Edwards ( 2020 )

Breakdown of US government spending, 2005–2050 Source: Edwards ( 2020 )

Although mandatory unemployment insurance was the main cause of the recent spikes in total and deficit spending, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020 also provided for a substantial increase in discretionary spending. Among other things, Fishback explains, that Act extended unemployment benefits to workers whose employers had not paid for their insurance, while adding $600 to ordinary weekly payments – enough to avoid the normal 7 per cent decline in spending among the newly unemployed. 2 Finally, by providing for another $3.7 trillion in emergency spending, including a trillion dollars to support state and local governments, Congress raised government spending to a share of GDP approaching that of World War II. In short, despite being divided, the government, having long since overcome its New Deal‐era fear of deficit spending, was willing “to take steps that go far beyond what the New Deal government did in the 1930s” (Fishback, 2020 ).

Thanks in large part to this aggressive fiscal response, the pace of aggregate spending recovered relatively rapidly from its sharp decline between late January and mid‐April. As Figure 4 shows, by late September it had almost returned to its value a year before. However, that return still leaves the level of spending well below its former trend. Nor should the revival of total spending, so far as it goes, be allowed to obscure the dramatic change in its composition, which has left whole industries languishing even as it has invigorated others.

Change in all consumer spending, 2020 Source: Opportunity Insights Economic tracker ( https://tracktherecovery.org/ )

4. RELIEF, RECOVERY, AND REFORM

Although the scale of the fiscal response to COVID‐19 seems more reminiscent of that witnessed at the outbreak of World War II than of New Deal fiscal policy, today's fiscal response shares one important – and deleterious – feature with its 1930s counterpart, to wit, a tendency to conflate fiscal policies conducive to genuine recovery with policies that serve instead either to provide temporary relief only or to implement reforms that, whatever their long‐term merit, do little if anything to revive private market activity.

While President Roosevelt famously insisted upon distinguishing the ‘three R's’ of Relief, Recovery, and Reform, the distinction has not always been adequately appreciated by later students of the New Deal. Some, for example, insist on gauging the pace of recovery during the 1930s using Michael Darby's revised unemployment statistics (Darby, 1976 ), which include those working in the Works Progress Administration and other New Deal work‐relief programmes among the employed, instead of conventional series that consider them ‘unemployed’. Although one may well complain that ‘unemployed’ is the wrong word to describe persons who were in fact working, if only for modest wages, the fact remains that the series that commits this terminological offence is also the more reliable indicator of the progress of recovery.

Some assessments of the CARES Act's success likewise conflate its effectiveness as a source of temporary relief with its ability to promote lasting recovery. According to a recently published study (Ganong, Pascal, & Vavra, 2020 ), by August CARES Act relief recipients, having used up most of their emergency support, began to rein in their spending again, thereby exposing the US economy to a further downturn. “With savings dwindling and no further economic relief in sight”, the Wall Street Journal observes in reporting on the study, “nearly 11 million jobless workers may curb spending even further or fall behind on debt or rent payments” (Davidson, 2020 ). The same report has Peter Ganong, one of the study's authors, observing more bluntly that “[t]he economy right now is essentially running – or not running – on the exhaust fumes of the CARES Act”. In other words, notwithstanding claims made by President Trump and some other Trump administration officials, the (partial) revival of spending since April, like the post‐1933 decline in Darby's New Deal unemployment measure, may reflect the extent of relief only, rather than the true extent of recovery. 3 Only once the public's fear of infection subsides and presently restricted activities are allowed to resume will a more complete disgorgement of savings accumulated by those whose livelihoods were not cut off by the crisis (Bird, 2020 ) provide the basis for a sustained recovery.

It is also the case that some actual New Deal programmes seemed to honour the distinction between relief, recovery, and reform more in the breach than the observance. This was especially true of the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which was based on the premise that reforms long sought by labour representatives on the one hand and businessmen on the other would also serve, if implemented, to spur recovery. For reasons very thoroughly set forth in a 1935 Brookings Institution study, that premise was tragically mistaken; and the NRA, instead of hastening recovery, impeded it until the Supreme Court, by declaring it unconstitutional, brought the ill‐fated experiment to an end (Selgin, 2020c ).

A similar confusion of the goals of reform and recovery has also limited the effectiveness of the government's response to the COVID‐19 crisis. It has done so, most obviously, by inspiring attempts to treat both the original CARES Act and negotiations concerning a second stimulus package as Trojan horses by which to introduce or expand government programmes that, whatever their other merits, are unlikely to help to either shorten the COVID‐19 crisis or render it less painful. The $25 million in CARES Act support earmarked for the Kennedy Center was an especially notorious (and successful) instance of such an attempt; but there have been many others, both Republican and Democratic (Waldman, 2020 ). Mostly unsuccessful attempts by clean‐energy trade groups and environmentalists to include ‘green’ legislation in the CARES Act were an important cause of disagreements that delayed its passage (Brady, 2020 ). Similar attempts to smuggle (mostly progressive) reforms into a second stimulus package (Boehm, 2020 ) in turn contributed to the gridlock that dashed any hope for its passage by the Trump administration (Kane, 2020 ; Schalatek, 2020 ).

5. MONETARY POLICY

If the difference between New Deal and recent fiscal policy measures is great, that between the Fed's conduct during the New Deal and its recent conduct is even more pronounced. Indeed, it comes close to being a difference between doing nothing and doing (or trying to do) everything!

Thanks to Friedman and Schwartz ( 1963 ), the fact that the Fed failed to make adequate use of open‐market security purchases to prevent a ‘Great Contraction’ of the US money stock between 1929 and March 1933 is now notorious – so much so that former Fed governor Ben Bernanke felt obliged, on the occasion of Friedman's 90th birthday on November 2002, to apologise on the Fed's behalf to him and Anna Schwartz, while promising that the Fed would never “do it again” (Bernanke, 2002 ). What is not so well appreciated is the Fed's almost entirely passive role throughout the remainder of the 1930s, when, as Figure 5 shows, the Fed's total security and commercial bill holdings remained almost constant. The Fed's balance sheet did grow, thereby allowing the money stock to grow as well; but that growth was fuelled almost entirely by gold imports over which the Fed itself exercised no control and for which neither it nor the US government deserved credit. Instead, their main cause was the increasing likelihood of war following Hitler's rise to power. Even President Roosevelt's official devaluation of dollar in January 1934 contributed much less to US money growth than it might have: although the devaluation meant an immediate increase in the nominal US gold stock, instead of adding to banks' reserves the proceeds from it were appropriated by the US Treasury, which used most of them to establish its Exchange Stabilization Fund.

Federal Reserve's total security and commercial bill holdings, 1933–1939 Source: National Bureau of Economic Research

True to Bernanke's word, both during his tenure and since the Fed has avoided a repetition of its performance during the 1930s – and how! In one month starting in mid‐September 2008, the Fed's assets doubled; by early 2015 three rounds of quantitative easing had doubled them again, to about $4.1 trillion. The Fed's response to the current crisis has been even more dramatic: at the start of 2020 its assets were at roughly their level five years earlier (see Figure 6 ). They have since increased by another $3 trillion, and for the time being the Fed remains committed to buying at least $120 billion more each month.

Federal Reserve's total assets (2007–2020) less elimination from consolidation (Wednesday level) Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

While the impressive scale of the Fed's open‐market purchases makes for a sharp contrast with the situation in the 1930s, low interest rates were a feature of both episodes. Those low rates discouraged Fed authorities from buying securities during the New Deal, and have limited the stimulus effect of their recent purchases. In March 1934, the New York Fed reduced its discount rate to 1.5 per cent – its lowest level since the Fed was established; in September 1937 it lowered it another 50 basis points, to just 1 per cent, where it remained until the start of 1948. Yet even those record‐low discount rates were high compared to then‐prevailing rates on Treasury securities. The rates for three‐month Treasury bills are shown in Figure 7 , from a 2010 article by Gerald Dwyer. As Dwyer ( 2010 ) explains,

Interest rates on three‐month Treasury bills, January 1931 to December 1941

Note: The two average monthly rates are the interest rates at auctions of new issues of three‐month Treasury bills and the rate quoted by dealers on three‐month Treasury bills.

Sources: Auction rate, National Bureau of Economic Research ( www.nber.org/series no. m1302b); dealer quote, from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

With the exception of a brief period in 1937, interest rates on these securities never averaged as high as 25 basis points in any month from October 1934 to November 1941. Although interest rates on reserves were zero, interest rates on three‐month Treasury bills were not far from zero.

As Figure 8 shows, between them, banks' desire to keep liquid following the trauma of the Great Contraction, and the trivial opportunity cost of reserve holding caused them to accumulate reserves acquired as a result of heavy gold imports. Fed officials therefore concluded that open market purchases would only supply banks with that many more reserves to stockpile. This view was aired by then Fed Governor Marriner Eccles in his now famous exchange, during the hearings on what became the 1935 Banking Act, with Democratic Representative Prentice Brown and Republican Senator Phillip Lee Goldsborough. The exchange began when Representative Brown asked Eccles what the Fed might do were granted greater freedom to engage in open market operations:

Total reserves and excess reserves, January 1931 to December 1941

Notes: Assets in banks that were members of the Federal Reserve System were about 85 per cent of all assets in US banks. Data on excess reserves for March 1933 are missing in the source document.

Source: Dwyer (2010)

GOVERNOR ECCLES: Under present circumstances there is very little, if anything, that can be done.

MR. GOLDSBOROUGH: You mean you cannot push a string.

GOVERNOR ECCLES: That is a good way to put it, one cannot push a string. We are in the depths of a depression and, as I have said several times before this committee, beyond creating an easy money situation through reduction of discount rates and through the creation of excess reserves, there is very little, if anything that the reserve organization can do toward bringing about recovery. I believe that in a condition of great business activity that is developing to a point of credit inflation monetary action can very effectively curb undue expansion. (Banking Act of 1935 , 1935, p. 377)

The accumulation of excess reserves also caused Fed and Treasury officials to worry that, despite the economy's still depressed state, banks would soon attempt to shed those excess reserves, triggering unwanted inflation. In hearing this Keynes is supposed to have quipped that the officials in question “profess to fear that for which they dared not hope”. But the officials were all too in earnest. To avert the risk of inflation, the Fed took advantage of powers granted it by the 1935 Banking Act to double banks' reserve requirements, while the Treasury for its part began to sterilise gold inflows (Irwin, 2012 ). Inflation, sure enough, never broke out. On the contrary: the measures helped cause the ‘Roosevelt Recession’ of 1937–38, which undid much of the recovery of the preceding four years.

Treasury rates today are roughly as low as they were during the New Deal; and the result now as then is that banks have been accumulating reserves 4 sent their way, instead of employing them to achieve any corresponding growth in loans or deposits. Figure 9 , comparing the relative response of reserves, banks deposits, and M2, to the Fed's asset purchases, shows just how slight the effect of reserve growth has been on broader money measures. If one considers as well the sharp decline in M2 velocity that has taken place since February, it becomes evident that, if the Fed's asset purchases have indeed been helping to revive aggregate demand, they have not done so by way of any of the more conventional money and credit transmission mechanisms. So far as those mechanisms are concerned, today's Fed officials might well be said to have entirely overcome their predecessor's reluctance to go on ‘pushing on a string’.

Response of reserves, banks deposits, and M2, to the Fed's asset purchases, 2020 Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Banks' accumulation of reserves has nonetheless raised concerns about future inflation echoing those of 1930s – and just as misplaced. As the Fed's balance sheet expanded in April, various experts warned that the long‐term result might be “an ugly spell of high inflation ” (Long, 2020 ). Observing that in six weeks the “M2 money supply has increased by 7.7 percent, an annual compounded rate of 90.4 percent”, Martin Hutchinson ( 2020 ) claimed on 23 April that “you can't produce money at that rate without the dollar going the way of the continental, the assignat, the reichsmark or the 1946 Hungarian pengo”. In a Wall Street Journal opinion piece published that same day, Tim Congdon ( 2020 ) employed similar reasoning, albeit more soberly. The going rate of M2 growth, he wrote, approaches peak rates previously seen during the two world wars and the Vietnam War, all of which “were followed by nasty bouts of inflation”. Were inflation to break out again, Congdon concluded, “policy makers today being cheered for their swift, decisive action will instead have to answer for their grave lack of foresight”. The Fed's more recent decision to embrace average inflation targeting raised further alarms: writing in the Financial Times , Gavyn Davies ( 2020 ) observed that, although the Fed was “justified in deciding to risk higher inflation for the immediate future”, a similar regime “triggered the great inflation of five decades ago”.

Such dire warnings all share the implicit view that banks are bound eventually to try to rid themselves of all the new reserves the Fed's purchases have placed at their disposal, and that this will confront the Fed with an increase in the base money multiplier too sudden and large to be fully offset by any concurrent shrinkage of its balance sheet. But neither view is correct: under the Fed's post‐2008 ‘floor’ operating system (Selgin, 2018 ), the inflation rate no longer depends on the size of the Fed's balance sheet. Instead, to check excessive money growth the Fed has only to raise the interest rate it pays on bank reserves sufficiently to keep the base multiplier at a level consistent with its inflation target. Of course, it might fail to do so; but that possibility, far from being imminent, appears remote at present. Nor, to judge from the ten‐year breakeven inflation rate, which on 21 October 2020 was just over 0.142 per cent, do bond speculators suppose otherwise.

Justified or not, the fear that we may be risking a serious outbreak of inflation has thus far been voiced by pundits only, and not by any government officials. That is just as well, because it means that the government is not about to resort prematurely to anti‐inflation measures that might prove fatal to the ongoing recovery.

6. NEW DEAL ‘CREDIT’ POLICY

It is now common for economists to distinguish between monetary policy in the strict sense and ‘fiscal’ or ‘credit’ policy, where credit policy consists of direct central bank support to particular private firms and markets or foreign government entities, while monetary policy operations seek to regulate the general state of credit and liquidity, whether by means of central bank purchases and sales of domestic government securities or by adjusting central bank‐administered interest rates.

According to this distinction, the Fed's ‘credit policy’ undertakings during the 1930s were just as limited as its monetary policy undertakings. The Fed's direct lending then was almost entirely confined to Fed member banks (meaning all national banks and the relatively small number of state banks that chose to join the system); and even that aid was legally limited to very short‐term loans secured by ‘real’ (commercial) bills. The trivial scale of the Fed's New Deal‐era discount‐window lending is evident from Figure 10 , comparing the value of the Fed's commercial (‘real’) bill purchases with that of total member bank reserves. In January of 1939, for example, member banks held over $10 billion in reserve balances, while Fed's bill purchases amounted to just $1 million.

The value of the Fed's commercial (‘real’) bill purchases versus the value of total member bank reserves, 1929–1941 Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; National Bureau of Economic Research

It was mainly to supplement the Fed's limited lending, and especially to make emergency credit available to non‐member banks, that the Treasury‐funded Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) was established at the start of 1932. With the coming of the New Deal, the scale of the RFC's support for banks increased dramatically. The cause of this was an amendment to the 1933 Banking Act that allowed the RFC to purchase and lend upon banks' preferred stock, and also to purchase their unsecured debt instruments. The amendment law made it possible for banks to take advantage of the RFC's support without having to part with their best collateral. Over the course of the New Deal the RFC purchased over $1 billion in preferred stock, capital stock, and debentures from thousands of banks. In addition to supporting banks directly, the RFC helped them indirectly by lending to railroads, whose bonds were an important component of many bank portfolios. Eventually it also helped to finance federal public works projects and state unemployment relief programmes. Finally, in mid‐1934 the RFC was authorised to lend to ordinary business firms.

Two attempts were also made during the Great Depression to involve the Fed in lending to non‐bank businesses. The first, enacted in July 1932 as an alternative to allowing the RFC to lend to ordinary businesses, gave rise to the Federal Reserve Act's now notorious section 13(3) (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2017 ). In its original form, 13(3) granted the Federal Reserve Board the authority, under certain conditions, to authorise member banks

to discount for any individual, partnership, or corporation, notes, drafts, and bills of exchange of the kinds and maturities made eligible for discount for member banks under other provisions of this Act when such notes, drafts, and bills of exchange are indorsed and otherwise secured to the satisfaction of the Federal Reserve Bank.

However, because few businesses held the stipulated collateral, section 13(3) was almost stillborn: throughout the entire Great Depression the Fed only made 123 13(3) loans, amounting to just $1.5 million. Nor would the Fed make any further 13(3) loans until 2008, when modified 13(3) collateral requirements allowed it to lend extensively to non‐bank borrowers for the first time (Fettig, 2008 ).

The second Great Depression attempt to have the Fed lend to ordinary businesses left no permanent mark, but was more important at the time. This took place in 1934, and consisted of another Federal Reserve Act amendment – section 13(b) – which allowed Fed banks to make loans of up to five years to non‐bank businesses either directly or in partnership with commercial lenders (Selgin, 2020d ). Although the Fed made many more 13(b) than 13(3) loans during the depression – by the end of 1935, the former summed to $124.5 million spread among 1,993 businesses – this outcome was still disappointing, amounting as it did to a tiny fraction only of concurrent private sector business lending. Even so, the Fed continued to make 13(b) loans until 1958, when section 13(b) was repealed.

7. COVID‐19 CREDIT POLICY

Just as the Fed's limited Great Depression‐era open market purchases contrast sharply with its massive post‐COVID purchases, its Great Depression exercises in credit policy pale in comparison with those of recent months. Indeed, the Fed's recent undertakings, undertaken mainly on the basis of its 13(3)‐lending authority, overshadow the combined efforts of the Fed and the RFC during the 1930s, exceeding them in both scale and scope. Among other steps, the Fed has lent to ordinary business firms both through its own ‘Main Street’ lending facilities and by extending credit to banks taking part in the Small Business Administration's Paycheck Protection Program; it has provided short‐term funding to state and local governments through its Municipal Funding facility; and it has contributed to the supply of credit to larger enterprises through both direct and secondary‐market purchases of their securities via its Primary and Secondary Market Corporate Credit facilities.

The Fed's heavy involvement in credit policy has been extremely controversial. Politicians have berated it for doing too much for Wall Street and not enough for Main Street (Saraiva & Matthews, 2020 ); and even the Wall Street Journal ( 2020 ) agrees with them. Economists have in turn argued that, by involving itself so heavily in credit policy instead of leaving it to Congress and the Treasury, the Fed has put its independence at risk. Observing that, thanks its extensive 13(3) programmes, the Fed now resembles a “giant, multi‐faceted GSE [government sponsored enterprise]”, former Richmond Fed economist Robert Hetzel wonders whether its independence can long survive politicians' discovery that the change allows them “to transfer risk to the Fed's books where it is invisible to taxpayers” (Hetzel, 2020 , pp. 25, 35).

8. MAIN STREET DÉJÀ VU

Of the Fed's current emergency lending programmes, only those aimed at Main Street have a close Great Depression counterpart, consisting of the Fed's previously‐mentioned 13(b) lending. As we have seen, the results of that earlier programme were disappointing. One might therefore expect Fed officials this time around to have launched their Main Street facilities only after studying that earlier experiment and convincing themselves that the new plan would be free of its predecessor's shortcomings.

Alas, that doesn't seem to have happened. Instead, so far as the record reveals, in designing the Fed's Main Street facilities, neither Fed nor Treasury officials referred to the earlier experience. In any event, the new Main Street lending programme very much resembles its predecessor both in its particulars and in its disappointing results thus far (Selgin, 2020d ). According to the Fed's disclosure of 8 October, 5 in four months the Main Street facilities have only taken part in 253 business loans summing to under $2.2 billion, or just 0.366 per cent of the Main Street facilities' capacity. In comparison, commercial banks had almost $2.8 trillion in ordinary commercial and industrial loans outstanding in September. The number of banks that have taken part in the Main Street programme this far has been even more disappointing: so far fewer than 100 have done so, and just one – the City National Bank of Florida – has originated 40 per cent of the programme's loans, worth almost one‐quarter of the outstanding total (McCombie, 2020 ). It is all but impossible to reflect upon this record, and that of the Fed's depression‐era 13(b) lending, without thinking of Santayana's hackneyed saying about the past. 6

9. AN UNEQUAL RECOVERY

There is one further, unflattering respect in which current efforts to counter the economic damage from COVID‐19 and the activity restrictions it has inspired resemble the New Deal: both have been charged with racial discrimination.

As NPR's Christopher Klein reports ( 2018 ), the New Deal's Civilian Conservation Corps assigned African Americans to separate camps, while the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure mortgages made to their neighbourhoods. African Americans were also denied Social Security benefits. Otis Rolley, Senior Vice President of the Rockefeller Foundation's U.S. Equity and Economic Opportunity Initiative, adds that they were also denied the protections that the National Labor Relations Act afforded to other workers. Most of all, African Americans suffered from the Agricultural Adjustment Association, which by paying (mostly white) farm owners to grow fewer crops, forced hundreds of thousands of African‐American sharecroppers to take part in the Great Migration from the rural South to northern and western cities, were they added to the already bloated ranks of unemployed African Americans. According to Rolley, this discrimination was not at all inadvertent. “Roosevelt”, he explains, “intentionally cut out occupations dominated by people of color, including domestic and agriculture workers, from New Deal initiatives as part of a strategy to win the support of Southern Democrats in Congress.” Nor were the consequences temporary. Instead, discriminatory New Deal legislation “created deeply‐entrenched racial and financial inequities that persist to the present day” (Rolley, 2020 ).

The CARES Act has likewise been accused of neglecting African Americans and racial minorities, who thanks to their relative poverty have also suffered disproportionately from the COVID‐19 virus itself (Bouie, 2020 ). Because it relied on tax filers' bank account information, the Treasury Department's chosen method for delivering stimulus checks delayed payments to poorer persons, a disproportionate share of whom are minorities (Davison, 2020 ). It also denied many immigrants the COVID‐19 testing and care benefits offered to US citizens (Waheed & Moussavian, 2020 ). That only $10 million of the CARES Act's $2.3 trillion in relief funding went to the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) has also been seen by some as evidence of deliberate discrimination (Perry & Hopkinson, 2020 ).

For all their merit, such complaints inevitably suffer from some blurring of the distinction between recovery and reform pointed out in section 4 . That is, they often call, implicitly if not explicitly, not simply for measures calculated to hasten the general pace of economic recovery, but also for ones that would help to lesson racial inequality regardless of their effects on macroeconomic aggregates. This doesn't mean that some trading‐off of one objective for the other isn't worthwhile – nor could there be any scientific basis for such a claim. It is merely a reminder that the two objectives are not always congruent.

LEGISLATION CITED

Banking Act of 1935 (US). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2010-title12/USCODE-2010-title12-chap3-subchapI-sec228/context (accessed 8 December 2020).

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act 2020 (US). https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr748/BILLS-116hr748enr.pdf (accessed 8 December 2020).

Federal Reserve Act 1913 (US). https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fract.htm (accessed 8 December 2020).

Selgin G. The fiscal and monetary response to COVID‐19: What the Great Depression has – and hasn't – taught us . Economic Affairs . 2021; 41 :3–20. 10.1111/ecaf.12443 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

1 See Cerra and Saxena ( 2008 ), Reinhart and Rogoff ( 2009 ), Reinhart and Reinhart ( 2010 ), and Ikeda and Kurozumi ( 2018 ).

2 See Farrell et al. ( 2020 ). According to this study, “unemployed households actually increased their spending beyond pre‐unemployment levels once they began receiving benefits. The fact that spending by benefit recipients rose during the pandemic instead of falling, like in normal times, suggests that the $600 supplement has helped households to smooth consumption and stabilized aggregate demand.”

3 In fact, as Jason Taylor ( 2011 ) explains, because almost all the decline in unemployment between 1933 and 1937 was due to “work sharing” policies rather than to an increase in total working hours, even the conventional unemployment numbers exaggerate the pace of economic recovery during that time.

4 Because reserve requirements were eliminated in March, it is no longer possible to refer to ‘excess’ reserves.

5 See Excel file mslp‐transaction‐specific‐disclosures‐10‐8‐20.xlsx.

6 “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

- Banking Act of 1935 (1935). Hearings Before the Committee on Banking and Currency. House of Representatives, Seventy‐Fourth Congress. First Session, on H. R. 5357 . Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/banking-act-1935-831 (accessed 3 December 2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernanke, B. (2002). On Milton Friedman's Ninetieth Birthday. Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke at the Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, 8 November, University of Chicago. Federal Reserve Board . https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2002/20021108/ (accessed 3 December 2020).

- Bird, M. (2020). The coronavirus savings glut . Wall Street Journal , 23 June.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2017). Federal Reserve Act, Section 13: Powers of the Federal Reserve Banks . About the Fed , 13 February. https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section13.htm (accessed 3 December 2020).