The Applied Sci-Fi Project

How can we apply science fiction storytelling as a tool for imagining and shaping the future of technology?

The Applied Sci-Fi Project, made possible by support from the Sloan Foundation, is an event series and research project that brings together science fiction writers, futurists, scholars, and technologists to survey how science fiction narratives can shape the development of real-world technologies. We will examine the general influence of sci-fi on technology and the people who develop it, as well as the specific ways that sci-fi storytelling is being applied as a tool for innovation and foresight.

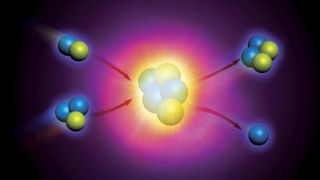

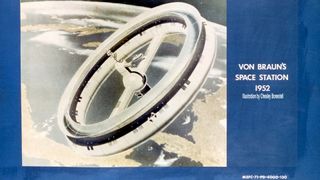

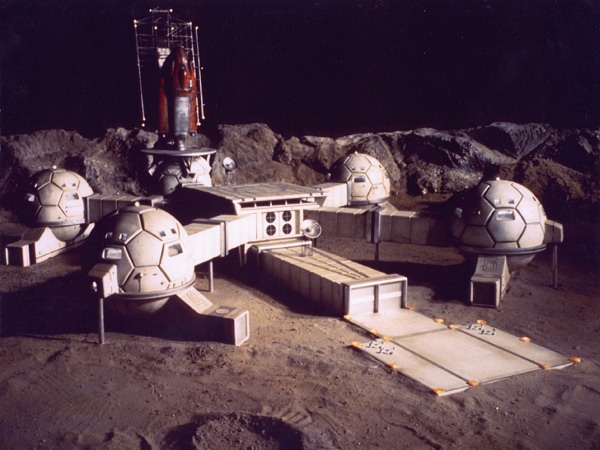

There’s little question that the imaginary futures of science fiction have influenced the direction of technology, from space travel to cell phones to cyberspace.

Recognizing this “Sci-Fi Feedback Loop” between speculative visions and real-world innovations, a growing multi-disciplinary field of practitioners is using science fiction as a tool for thinking about, preparing for, and perhaps even shaping our increasingly uncertain future.

This loosely connected but rapidly expanding field, which we’re calling Applied Sci-Fi, includes:

- strategic foresight consultants who partner with sci-fi writers to develop potential future scenarios for their corporate and government clients;

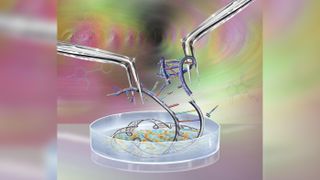

- designers and engineers using design fiction, sci-fi prototyping, and worldbuilding techniques to ideate new technologies and environments;

- policy think tanks commissioning sci-fi to envision creative solutions to societal challenges;

- professors using sci-fi to educate engineers, lawyers, and other professionals about tech ethics;

- venture firms and startup founders mining the latest sci-fi for product ideas;

- technical consultants working to ensure that visions of the future in TV and film reflect real science and technology;

- and much more.

The Applied Sci-Fi Project will bring together this emerging community of experts and practitioners in a series of public conversations and private workshops to examine different aspects of its history and practice. These events will inform a series of papers that will serve as a practical introduction to the Applied Sci-Fi field, its practitioners, and their tools: an Applied Sci-Fi Sourcebook surveying the history of sci-fi as both an unintentional influence on, and intentional tool for, technological innovation.

Reimagining “The Future of [X]”

Science Fictional Scenarios and Strategic Foresight

Designing the Future with Applied Sci-Fi

The Sci-Fi Feedback Loop: Mapping Fiction’s Influence on Real-World Tech

This project has been made possible by a generous grant from the Technology Program of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

Publications

Surveying the contemporary field of sf fiction, media, and scholarship.

The SFRA’s publication of record is the SFRA Review (ISSN 2641-2837). Published quarterly, SFRA Review is devoted to surveying the contemporary field of SF fiction, media, and scholarship as it develops, bringing in-depth reviews with each issue, as well as longer critical articles highlighting key conversations in SF studies, regular retrospectives on recently passed authors and scholars, and reports from members of the SFRA Executive Committee.

The SFRA is also dedicated to promoting research and teaching of science fiction through the publication of anthologies and collections. These include David G. Hartwell and Milton T. Wolf’s Visions of Wonder: The Science Fiction Research Association Reading Anthology (1996), Patricia S. Warrick, Charles G. Waugh, and Martin H. Greenberg’s Science Fiction: The Science Fiction Research Association Anthology (1998), Hal W. Hall, Daryl F. Mallett, and Fiona Kelleghan’s Pilgrims & Pioneers: The History and Speeches of the Science Fiction Research Association Award Winners (1999), and Karen Hellekson, Craig B. Jacobsen, Patrick B. Sharp, and Lisa Yaszek’s Practicing Science Fiction: Critical Essays on Writing, Reading and Teaching the Genre (2010).

Femspec, an interdisciplinary peer-reviewed journal exploring gender in speculative genres, offers discounts to SFRA members negotiated directly with the editor. Contact [email protected] with proof of membership status. See femspec.org for more information.

Join fellow scholars, educators, librarians, editors, authors, publishers, archivists, and artists from across the globe in the SFRA.

Science Fiction & Fantasy: A Research Guide: Articles

- Reference Sources

- Biographical Sources

- New Acquisitions

- Primary Sources

Selected Article Databases

Scholarly and substantive articles on fantasy and science fiction have been appearing in academic journals with regularity since the 1970s. While there is no database exclusively devoted to indexing secondary work these genres, the sources listed below include articles published in academic journals centered on literary, film, and cultural studies.

Note that these resources generally do NOT index creative work in science fiction magazines (e.g., Strange Horizons, Interzone ) or material appearing in fanzines and other amateur publications.

The Library provides networked access to many more secondary source databases -- indexes and full-text -- than can be listed here. Others may be located through the Library Catalog and Databases .

- Academic Search Premier This multi-disciplinary database provides full text for more than 8,500 journals, including full text for more than 4,600 peer-reviewed titles. PDF backfiles to 1975 or further are available for well over one hundred journals, and searchable cited references are provided for more than 1,000 titles.

- America: History & Life America: History and Life (AHL) is a complete bibliographic reference to the history of the United States and Canada from prehistory to the present. Published since 1964, the database comprises over 530,000 bibliographic entries for periodicals dating back to 1954. Additional bibliographical entries are constantly added to the databases from editorial projects such as retrospective coverage of journals issues published prior to 1954.

- Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (ABELL) ABELL covers monographs, periodical articles, critical editions of literary works, scholarly book reviews, collections of essays and doctoral dissertations published anywhere in the world from 1920 onwards. All aspects and periods of English literature are covered, from Anglo-Saxon times to the present day. British, American and Commonwealth writing are all represented. Also accessible through Literature Online .

- FIAF International Index to Film Periodicals Contains over 500,000 article citations from more than 345 academic and popular film journals. Each entry consists of a full bibliographic description, an abstract and comprehensive headings (biographical names, film titles and general subjects). Coverage extends back to 1972.

- Film Literature Index Indexes 150 film and television periodicals from 30 countries cover-to-cover and 200 other periodicals selectively for articles on film and television. The periodicals range from the scholarly to the popular. More than 2,000 subject headings provide detailed analysis of the articles. The FLI Online contains approximately 700,000 citations to articles, film reviews and book reviews published between 1976-2001.

- Humanities International Index Indexes articles and books across the arts and humanities disciplines from a multitude of U.S. and international publications. HII also provides citations for original creative works including poems, fiction, photographs, paintings and illustrations. Many links to full text.

- Performing Arts Periodicals Database Formerly the International Index to the Performing Arts (IIPA) covers dance, film, television, drama, theater, stagecraft, musical theater, broadcast arts, circus performance, comedy, storytelling, opera, pantomime, puppetry, and magic. Full text from 1999 onward.

- JSTOR JSTOR is a fully-searchable database containing the back issues of several hundred scholarly journals in the humanities, social sciences, mathematics, music, ecology and botany, business, and other fields. It includes the following collections: Arts & sciences I, II and III, General science, Ecology and botany, Business, Language and literature.

- ProQuest One Literature Former name: Literature Online. Offers a full-text collection of poetry, drama, and prose with complementary references sources as well as articles, monographs and dissertations from the Annual bibliography of English language and literature (ABELL); full-text articles from literary journals; and biographical information on widely studied authors.

- MLA International Bibliography The premier scholarly bibliography covering languages, literatures, folklore, film and linguistics from all over the world. Online coverage back to 1926. Includes books, articles in books, and journal articles. Does not index book reviews.

- Periodicals Index Online Index to thousands of periodicals in the arts, humanities and social sciences across more than 300 years, covering each periodical from its first issue. Every article is indexed. The scope is international, including journals in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish and other languages. Previously known as Periodicals Contents Index (PCI).

- Project Muse Full text of scholarly journals in the humanities, social sciences, and mathematics. Covers such fields as literature and criticism, history, the visual and performing arts, cultural studies, and others.

- ProQuest Research Library ProQuest Research Library, formerly known as Periodical Abstracts, is a comprehensive database available through the ProQuest online system. It indexes and abstracts general interest magazines and scholarly journals in the social sciences, humanities and sciences. It comprises two components: a core list of periodicals covering about 800 publications, and 15 subject-specific modules that supplement the core list. Modules cover arts, business, children, education, general interest, health, humanities, international studies, law, military, multicultural studies, psychology, sciences, social sciences, and women's interests. Full text of many articles is provided.

- Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Database An on-line, searchable compilation and extension of Science Fiction and Fantasy Reference Index 1878-1985, Science Fiction and Fantasy Reference Index 1985-1991 , and Science Fiction and Fantasy Reference Index 1992-1995 (all by by Halbert W Hall), including material located since publication of the last printed volume. Based at Texas A&M.

- Web of Science Choosing "All Databases" allows you to search an index of journal articles, conference proceedings, data sets, and other resources in the sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities.

Indexes/Bibliographies for Secondary Sources

Bibliographies are rich sources of citations to both journal articles and monographs. To locate these in the Library Catalogs, enter the word bibliography as a Subject term in conjunction with keywords such as fantasy, science fiction, gothic , Asimov , etc. A few general bibliographies appear below.

- Bibliographie der Utopie und Phantastik 1650-1950 im deutschen Sprachraum by Robert N. Bloch Call Number: Olin stacks PN6071 F25 B56 2002 Publication Date: 2002 Bibliography of German-language utopian and fantasy fiction, including translations into German from other languages.

- Ecrits sur la science-fiction : bibliographie analytique des études & essais sur la science-fiction publiés entre 1900 et 1987 : littérature, cinéma, illustration by Norbert Spehner Call Number: Library Annex Z5917 S36 S64x 1988 Publication Date: 1988 International bibliography of secondary works on science fiction (literature, film, art). Covers books, periodical & newspaper articles, and theses published between 1900 and 1987 in English, French, and other languages.

- Science fiction, fantasy, and horror reference : an annotated bibliography of works about literature and film by compiled by Keith L. Justice Call Number: Olin Reference Z5917 S36 J96 Publication Date: 1989 An annotated bibliography of 300 secondary works on science fiction and fantasy literature.

- Fanzine index : listing most fanzines from the beginning through 1952 : including titles, editors’ names, and data on each issue by Bob Pavlat and Bill Evans, editors. Call Number: Uris stacks Z5917 F3 P33 1965 + Publication Date: 1965

Academic SF/Fantasy Journals

The Library subscribes to several academic journals focusing on science fiction and fantasy. Here is a selection of currently received titles, as well as some freely available online:

Bulletin (Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America) - OLIN PS374.S25 S41 Extrapolation - OLIN PN3448.S45 E96 + ( online 1994 -) Femspec - online only Horror Studies - online and print: OLIN P96.H65 H67 Journal of Dracula Studies Journal of the fantastic in the arts - online and print set OLIN PN56.F34 J86 Mythlore online and in print - OLIN PR6039.O49 Z93+ Science fiction film and television - Science-fiction studies online and in print - OLIN PN3448.S45 S44 SFRA Review - freely accessible online from 2001; latest issue available 10 weeks after print publication) Studies in the Fantastic

- << Previous: New Acquisitions

- Next: Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2023 5:03 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/scifi

Welcome to Science & Fiction

Accessible scientific results and exciting fictional stories in one. This is a space for people who like to a) learn about science and b) read science fiction at the same time. The stories are written by different authors and therefore deal with a wide variety of topics - there is something for everyone! New stories are published monthly around the middle of each month.

Each contribution below includes the following:

- A fictional short story, poem or other literary work;

- A scientific publication related to the story;

- An easy-to-understand summary of the publication and explanation of its connection to the story;

- Any content warnings (CWs) to highlight sensitive topics;

- Tags to search for story themes.

Browse through all stories or use the tags to search for specific topics (e.g. romance or utopia). There are not only short stories to read, but also comics! The CW stands for content warnings that you might want to know before you start reading.

A comic about the role of the brain’s immune cells in Alzheimer’s disease.

An unusual encounter during a walk home in Rome.

Getting over heartache is not easy when you cross paths with your ex. CW: breakup.

Soothing sounds of healthy reefs luring fish back to damaged coral habitats.

A cyborg adjusts to his new prosthetics with the help of scientists. CW: Prosthetics

A tired cop tries to make it through a day of crashes. CW: Car accident.

You visit Hilbert in his hotel and find some interesting artifacts.

Sci-fi scientists discuss the nitty gritty of creating a cyborg. CW: Prosthetics

Have you thought of love as an all-or-nothing reaction? CW: Sexual desire and preferences

Today’s mightiest technologies morph into a child’s homework companions tomorrow.

A story about babies and robots understanding intentions through gaze.

Confronting yourself might be easier than it seems. CW: drug use, anxiety, depression.

The brain during swimming. CW: disappearance, reckless behavior, PTSD

Who ist Paula 2.0 and why does she look like me? CW: drug use, anxiety, depression.

If you could avoid every fearful situation in the blink of an eye…would you? CW: death.

A story about meeting someone you did not expect. CW: drug use, anxiety, depression.

A story about an uncomfortable journey and personal space. CW: crowds, mental health.

A story about two dogs behaving very strange. CW: suspense.

An upside down story about being neurodiverse. CW: mental health.

A story about taking a pill that will change your life forever. CW: drug use.

This project is accepting guest contributions, and you can see the author of each story in the corresponding cover image and on the respective story page. If you want to contribute ideas or stories yourself, you have two options:

Are you interested in sending me a story idea or paper you’d like me to write a story around? Submit your ideas here .

Do you want to write your own story, practice your science communication, and share it with the world at the same time? I am happy to publish your work here as part of Science & Fiction as a guest contribution. Submit your work here .

Submission guidelines

- You need a scientific paper and a short story that matches that paper. While the project originally publishes short stories, you can also submit anything else artistic, such as poems, photos, drawings, comic, graphic novels. … you name it! In that case please shortly e-mail me at [email protected] before the submission.

- You don’t need to be an active scientist to submit a contribution, but the story should be connected to scientific work somehow. The paper can be your own work or just a paper you find interesting and relevant.

- You need the full citation and link to the scientific paper and a short summary of the paper in lay language. What you write should be understandable for a non-scientific audience (around 1-2 sentences each for introduction, methods, results and discussion). Also add a few words on how the paper and the story are connected. This is important as the two main goals of Science & Fictions are to entertain and educate. The story-paper connection may be through the results (”painkillers reduce empathy” or “sleeping makes you learn better”) or just the broad topic (”pain” or “placebos”).

- In terms of the story genre or scope, there are no limits, so you can let your creativity run wild. There is also no strict word limit. By sending me your story, you agree to have it published on the Science & Fiction website under your name, and publicised on social media. Be aware of this, when you write about critical or personal topics. You can also submit the story to be published anonymously, in that case just tick the “anonymous” box in the submission form.

- If you need inspiration what to put for some of the fields, check here .

- Stories are reviewed by me (Helena Hartmann) and I reserve the right to reject stories if I think they will hurt certain people or groups of people or violate code of conduct rules (see e.g. here ). You’ll receive an answer from me after max. 4 weeks whether your story is accepted.

Science and Fiction

About the project.

Science & Fiction is a science communication project launched in January 2023. It was created by Dr. Helena Hartmann . Helena is a neuroscientist, psychologist and science communicator from Germany. She currently works at the University Hospital Essen (DE) as a postdoctoral researcher. Before, she completed her PhD at the University of Vienna (AT). During this time, she was a visiting researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience (NL). The project started featuring guest contributions from June 2023 onwards. Since February 2023, the project has its own domain ( www.scienceandfiction.net ) and there is a German version where many stories were translated from English ( www.scienceandfiction.net/de) .

Disclaimers

Please be aware that while this project connects science fiction with science communication about real scientific results, the short stories are purely fictional and sometimes only inspired by the scientific results, for example in terms of the theme or underlying phenomenon. The stories therefore do not attempt to exactly mirror the scientific research or precisely describe its results, they are rather a gateway to make you interested to know more about the science behind it. Please always also have a look at the original publication if you want to know more about the respective studies.

The German version also contains stories that were originally written in English and translated to German either by the authors or by Helena (the latter using support from DeepL). This can be checked at the end of each story.

If I missed a content warning, you can’t access a certain publication or anything is unclear, please write me at [email protected] .

Credit attribution

All artwork is created by the authors themselves or using the free version of Canva . To cite a story, please refer to it as follows: Author (month year). Title. Science & Fiction . URL: https://… (e.g. Hartmann, H. (January 2023). Emotion to go. Science & Fiction . URL: https://scienceandfiction.net/stories/1_emotion-to-go/ ).

Social media

The project is listed as a science communication project on the NaWik . Follow this project on X/Twitter or BlueSky for regular story updates.

Podcast appearances

- In Clarified about Science & Fiction - with Clara Marx and Helena Hartmann.

- In Metaphorigins about storytelling science using fictional stories - with Kevin Mercurio and Helena Hartmann.

- In Research Insider about science communication and science storytelling - with Waywen Loh and Helena Hartmann.

Speculative Fictions and Cultures of Science

Welcome to speculative fictions and cultures of science, mission statement.

The Speculative Fiction and Cultures of Science (SFCS) program, founded in 2013, has its origins in then-Dean Dean Steven Cullenberg's decision to create an academic unit to complement the strength of the Eaton Science Fiction Collection in the UCR library. New faculty members whose research focuses on speculative fiction were hired as part of this initiative, and they were joined by existing CHASS faculty working in related research to found the program.

The SFCS program explores intersections among speculative fiction, science and technology studies (STS), and traditions of speculative thought. We study the pervasive role of speculative discourses in public culture, investigating the complex and reciprocal exchanges among futuristic discourses, research agendas, public policy decisions, media texts, and daily life in technologically saturated societies. Using the combined perspectives of cultural studies and STS helps students develop critical literacy about their media-dominated landscape through which to understand its discourses of science and the future. Bringing speculative fictions and STS into dialogue, our scholars focus on understanding technological change in specific contexts by analyzing the texts and practices that have responded to, critiqued, and build upon the ways science shapes our cultural, material, and economic milieu. Speculative thinking and speculative fictions are central to many of the most compelling contemporary research concerns, such as the Anthropocene, climate change, genetic engineering, and discourses of the posthuman. The power to depict and thus shape the future is similarly key to urgent social justice movements, such as the Black Lives Matter, ongoing struggles for economic equity, and movements for sustainability.

Consistent with other STS programs, we examine the histories and cultures of science, technology, and medicine to understand the role culture plays in the production of science and the reciprocal way changes in science and technology shape culture. Our program uniquely emphasizes the role of popular culture and the genres of speculative fiction, in particular, for serving as an imaginative testing ground for technological innovation, articulating hopes and anxieties regarding technological change, and mediating public understandings of science and its applications.

The program offers a Designated Emphasis (DE) at the PhD level and an undergraduate minor (currently called Science Fiction and Technoculture Studies) at the undergraduate level. Our curriculum encompasses courses in the social study and history of science and medicine, in the history of technology, in speculative thought, in creative expression across media, in new digital cultures, in cultural analysis of texts and contexts shaped by scientific change, and in cultural differences among scientific practices. The DE and minor offer a rich interdisciplinary study of cultural ways of responding to changes in science and technology, and complements program majors in departments such as Anthropology; Comparative Literature; Creative Writing; English; Ethnic Studies; History; Media and Cultural Studies; Philosophy; Theatre, Film and Digital Production, and Gender and Sexuality Studies.

- KGRI Research Projects

- KGRI Research Centers

- Research Project Keio 2040

- News & Events

- Researchers & Achievements

- Great Thinker Series

- Lecture Series

- Virtual Seminar Series

- Research Papers

- Research Frontiers - '18

- Working Papers

- Endowed Courses

- Project Members

- Project List

- Research Centers

- 2023 Projects

- Science Fiction Rese...

Science Fiction Research and Development Center

- Return to Project List

Based on the history of science fiction in art and creation and its transformation, this research center will explore science fiction as a methodology for human society innovation through collaborative exploration of the value of stories by researchers in literature, engineering, and art. The goals of this research center are the following four points: A. Cross-cutting literary, engineering, and aesthetic research on the mechanism of storytelling with a focus on science fiction B. Development of creativity support technology using information technology, etc. C. Dissemination of creativity support methods for people using SF prototyping D. Application and publication of intellectual property based on SF R&D

Operational Period

Members ◎ indicates the project leader.

| Name | Affiliation | Position | Field of Specialization/Research Interests |

|---|---|---|---|

| ◎ Hirotaka Osawa | Faculty of Science and Technology | Associate Professor | Human-Agent Interaction, Science Fiction Prototyping |

| Susumu Niijima | Faculty of Economics | Professor | Modern and contemporary French literature (Raymond Roussel, Jules Verne), bachelor machine art, science fiction |

| Ai Hasegawa | Faculty of Science and Technology | Associate Professor | Speculative Design, Art & Design, Diversity & Equity & Inclusion, Ethics, SF Prototyping |

- About this site

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © Keio University. All rights reserved.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| is an award-winning science-fiction author and scholar, founded the new ( ), directed (and previously helped run) the from 1995-2022, teaches SF and creative writing at KU and elsewhere, and offers workshops and masterclasses around the world. He's been a professional writer and editor for decades, managed a documentation team, freelances for a variety of publishers, worked in the gaming industry, and is a popular public speaker. He writes not just and , but also such as astronomy articles, technical documents, game supplements, journalism (and some , too)... just about every writing genre. He's also edited magazines, developed websites since the 1990s, and more. His newest short fiction, " ," won the . His debut novel, , is now in its second edition. He recently finished a far-future novel, , and has several other projects on the burners, including . Feel free to mine his experience for tips and advice about writing, editing, and the science fiction field.

Read , or check out . Feel free to mine his experience for tips and advice about writing and editing in general, as well as about the science-fiction field. (class communication - please put the course name in the subject line for clarity) Other contact info: (narrow it down by going to my tags; writers, check out my various tags) -->

- Annalee Newitz, . By successfully completing this course, you'll become fluent in SF by studying some of the most-influential novels that shaped the genre and the world we inhabit today - and where we'll live tomorrow. Gain an understanding of contemporary and future science fiction by studying the history of the genre and many of the works that started important conversations about what it means to be human in a changing world. After reading a diversity of novel-length SF, we discuss how the genre got to be what it is today by comparing the works and their place in the evolution of SF, from Wells through more recent books. You will demonstrate your understanding of the genre by writing daily reading responses, writing a mid-term paper, participating in a group presentation, and creating a substantial final project. By the end of the semester, you'll gain significant expertise in the field. Award-winning SF author and scholar leads the course. To empower you to earn your best grade, practice research and participation skills that'll help your scholarly and professional careers, and get the most out of the course, you have endless opportunities to earn bonus ( ) points using an additive (rather than the typical deductive) grading system. You'll find lots of suggestions for additional related research, events, and media throughout the syllabus as well as via Blackboard announcements and in-class discussion. Take full advantage of these opportunities - and exceed minimum writing and participation expectations - to your grade! This course is now exclusively offered for professionalization through the for educators, science-fiction authors, and readers looking to deepen their understanding of the genre. For those enrolling not-for-credit, you can ignore mentions of grading (I've left these in for other educators looking for syllabus-building ideas). , and serves as a capstone course. Available to undergraduate and graduate students. graduate students can take up to two 600-level courses for credit. Ask your advisor for details about how the various ways to enroll best fit your needs.-->Everyone enjoys equal access to our , and we actively encourage students and scholars from diverse backgrounds to study with us. All courses offered by Center-related faculty are also available to be taken not-for-credit for professionalization purposes by community members (if space is available). . The coordinates accommodations and services for all eligible KU students. If you have a disability for which you wish to request accommodation and have not contacted the AAAC, please do so as soon as possible. Their office is located in ; their phone number is (785)864-4064 (V/TTY), or email them at Feel free to contact me privately about your needs in this course. See the reading list, below, for the most-current set of works we'll read and discuss. very useful in finding the stories in our various volumes (for reference only - see the syllabus, below, for which stories we read, when). Always read the short essays that introduce each story, as well as the book introductions whenever we start a new volume.--> Each day, one or two students help lead discussion, bringing enough good questions to keep a lively discussion going for the class period; . (Your instructor also brings lots of his own prompts and notes, so you're not alone.) Discussants should also seek relevant information about the authors, how the stories influenced the science fiction that was to follow. You must lead the daily discussion at least once alone or twice with a partner, but may serve more often. This is a major part of your grade and an important learning opportunity. : In preparation for each session, find, read, and respond to short (or long, if you choose) work that represents the week's topic, time period, author, or literary movement. Include your response to this work as part of your regular response paper. If you find it online, provide a link in your response paper. Otherwise, include bibliographic information. Also please share these recommendations for your classmates via the Blackboard discussion forum. This list reflects important works that helped shape the genre. Here is what we'll read, alphabetical by author. , edited by James Gunn.--> The titles below contain links to online booksellers like and ; click these links to find the books for sale online: ; (Note: These all link to the Scarecrow editions, but any you can find will work. If you use the early paperback editions, be aware you might need to hunt down a couple of missing stories.) : : :Full details about which stories we'll be reading and discussing on each day are available below. --> | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ], book one of the trilogy | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] ) [ | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ]Some of these volumes might be difficult to find, so I urge you seek copies early and, when books are out of print, search used bookstores (such as and Hastings) and online services (we've provided links to two major online booksellers after each title, above). The University of Kansas Jayhawk Ink bookstore has copies of many of these books on hand. The Center also holds a few copies of many of these books, so if you are local to Lawrence or are in town for our other summer programs, check with me to see if we can lend you a copy. These are available on a first-come, first-served basis. This course-specific lending library is primarily supplied by previous students donating copies after completing their course, so if you want to pass on the love to the next generation rather than keep your books, let your teacher know! For further reading - and to - here are the books that I've removed from the required reading list over time to reflect changing understanding of the genre. They're still important and recommended works for understanding the history of the SF novel, but we only have so much time: | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] | ] : , 1998 (White Wolf) : , 1998 (White Wolf)To get a full feel of the complete works from which we read a number of excerpts, be sure to look them up - most are in the public domain. Want more book recommendations? James Gunn and my " " is a go-to internet resource for building reading lists. It's organized by author. -->Want more ideas for Check out the . Most years, the majority of those works could have won the award if the jury had just a few different members. You can find tons more great SF novels in the . Want lots of free SF ebooks and e-zines? Check out . Want more book recommendations? James Gunn's and my " " is a go-to internet resource for building reading lists. It's organized by author. More in the " " at the end of this page. Keep checking back.... Here are the works we'll discuss each day, with links to online booksellers like and ; click these to find the books for sale online. The University of Kansas Jayhawk Ink Bookstore tries to have copies of these books on hand, and many other bookstores carry them, as well. useful in identifying where to find the stories in our various volumes. Be sure to read the short that introduce each story, as well as the book introductions whenever we start a new volume.--> Each week, two or three students lead the discussions, bringing enough good questions to keep a lively discussion going for the entire class period; for each class session. Discussants also seek relevant information about the authors, how the books influenced the science fiction that was to follow, and so forth. You must lead the daily discussion at least twice, but may serve more often. This is a major part of your grade and an important learning opportunity! . : Expect some updates before class; syllabus gets regular updates, including new suggestions to Level Up. " illustration.1.0! 1.1: Added links to free ebooks from some of the classic titles; also added a page about . Oct. 9: Added link to " " page in the section. Oct. 13: Fixed weekly syllabus note about Mid-Term paper. Oct. 28: Some discussion-leader updates. Dec. 2: Posted , added note about the question to answer with your final project. Dec. 12: Links to - and thanks for a great semester! Sept 2: Bonus reading for Week 2, updated office hours. Sept 7: Updated discussion leaders. Sept 8: Updated office - 340 Nichols Hall (Wed's). Sept 14: Bonus readings for Week 4. Sept 17, 24: Updated discussion leaders. Sept 28: Revised Weekly Schedule re: Mid-Term due date, added talk. Oct 8: Added new Level Up projects: for the Mid-Term Paper and Final Project. Nov 27: Added Presentation groups schedule! Watch for 2018 syllabus... -->

Week 2: September 4

Week 3: September 11

Week 4: September 18

Week 5: September 25

Week 6: October 2

Week 7: October 9

Week 8: October 16

Week 9: October 23

Week 10: October 30

Week 11: November 6

Week 12: November 13

Week 13: November 20

Week 2: September 3 In the Beginning / Visions of Humanity's Far Future

Week 3: September 10 The Alien Peril

Week 4: September 17 The Human Condition

Week 5: September 24 Thought Experiments

Week 6: October 1 Powers of the Mind / Evolution Continues

Week 7: October 8 Invoking the Social Sciences

Week 8: October 15 SF and the Literary Mainstream

Week 9: October 22 Dystopia and th e Future

Week 10: October 29 Tinkering with History

Week 11: November 5 The Biological Imperative

Week 12: November 12 Cyberpunk and the Singularity

Week 13: November 19 Looking Backward and Forward: Where Does SF Go Next?

November 25 No Class: Thanksgiving Break

December 3 Awesome Student Presentations! (or awesome final discussion about SF!)

December 10 Awesome Student Presentations!

December 17 - 18 No Class: Final Project Due

Course RequirementsTo successfully complete the course and get out of it all you can, you are required to:

To earn top scores and get a great final grade, be sure to Level Up whenever possible! Class PeriodsEach week we discuss a variety of readings, their authors, the science fiction genre, and the historical context in which they appeared. Occasionally, we might have guest speakers. Class periods revolve largely around discussion, with some lecture. Be civil : These are discussions about ideas, not arguments! Civility and respect for the opinions of others are vital for a free exchange of ideas. You might not agree with everything I or others say in the classroom, but I expect respectful behavior and interaction all times. When you disagree with someone, make a distinction between criticizing an idea and criticizing the person . Similarly, try to remember that discussions can become heated, so if someone seems to be attacking you, keep in mind they take issue with your idea , not who you are , and respond appropriately. Expressions or actions that disparage a person's age, culture, disability, ethnicity, gender, gender identity or expression, nationality, race, religion, or sexual orientation - or their marital, parental, or veteran status - are contrary to the mission of this course and will not be tolerated. If we all strive to be decent human beings, everyone will get the most out of this course! Attendance and Class ParticipationThis is a discussion-based course, so class participation is weighed heavily. Coming to class and getting involved in the discussions is necessary for getting a good grade, but also for getting the most value from the course. The discussions aren't just explication of plot or concept, though we will discuss those; I expect you to exercise your critical-reading skills. That is, don't just read the fiction for pleasure, don't just accept the related scholarship or introductions as canon, and don't feel the need to agree with your classmates' ideas - no one scholar can tell you the One True History of Science Fiction. By the end of this course you should possess expertise of your own in the topic. During the discussions, I want to witness your growing understanding of the genre based on the required readings, your outside research discoveries, and your own experience with SF over the years. Of course, be polite and diplomatic. Avoid dominating discussions, mindlessly blathering, talking over others, or speaking even when someone shyer than you has already raised their hand; doing so frequently can negate possible bonuses. Exercise your socialization: If you're normally shy, here's your chance to talk about something you love! If you're normally domineering, tone it down. If you know you are going to miss a class for an academic event, illness, or other excusable reason, contact me as soon as possible to see if we can work out something so it does not negatively affect your overall grade too much. If appropriate, I can mitigate this loss so your attendance percentage remains unaffected. Otherwise, here is how I score attendance and participation: During discussions, do not expose yourself or others to distractions such as checking email, Facebook, and so forth. If you're looking up relevant content, do so in a way that doesn't distract you or your classmates. Obviously, turn off your phone's ringer/buzzer. I know it's sometimes a challenge to focus during extended discussion, but recent studies show that the human mind cannot pay attention to more than one thing at a time, and fracturing your attention means you're not getting everything possible out of each discussion. Even worse, monkeying around online also interrupts your neighbors' attention. Feel free to take notes on your computer or portable device - for pulling up your notes or looking for content to share - if you choose, just stay away from distractions. It's difficult to remain engaged in discussions if your mind is elsewhere, and doing so also bumps down your overall grade. On the other hand, actively participating in class discussions bumps up your overall grade. I'm sure you have heard this before, but it's as true as ever: You get out of any activity only what you put into it. The more effort and creativity you apply to your projects and to class discussions, the more you will learn and the better the class will be for everyone else, as well. If you do not regularly attend class or do not participate in discussions, you'll miss out on a lot of opportunities to learn and grow as a person. Be sure to show up and get involved! Graduate students and teachers: I expect you to participate every day, providing insightful comments and questions while encouraging those less inclined to participate - but not to dominate the discussions. Attendance and class participation base value ( 3 points per class session ): 15 x 3 = 45 base points possible.

Missing class is the best way to lose points here: -3 points per missed class (after the first). If you know you are going to miss a class for an academic event, illness, or other excusable reason, contact me as soon as possible to see if we can work out something so it does not negatively affect your overall grade too much. If appropriate, I can mitigate this loss so your attendance percentage remains unaffected. DiscussantsYour instructor will likely open each day with some background on science fiction, especially the topics and genre movements relevant to the day's discussions, and some information about the authors. After that, two or more students lead (not monopolize) the discussion. You can split up the tasks among your fellow discussant(s) based on readings, topics, or however you see fit. I simply expect everyone to serve equally. Everyone is required to act as discussant at least twice during the semester. If you have special needs and cannot perform this task, let me know early. Discussants perform additional research prior to class (further readings on the genre movements at hand and the day's authors, identifying possible multimedia content, and so forth) and come prepared with at least six questions and discussion prompts for each book to stimulate discussion among your peers about the day's topic and readings. Turn in these discussion plans as your response for that week (in place of or in addition to your response paper). I expect all students to participate in discussions, but I also request that you avoid talking too much or talking over others. These are discussions about ideas, not arguments or lectures! If you would like to suggest relevant content (stories, comics, shows, movies, other narratives, or so forth) for the week you're leading discussion, by all means drop me an email with links to the materials! Great new SF is always appearing, and you might know of something I don't. This is a cooperative course! I'm happy to add links or suggested readings, given enough time for the rest of the class to read or otherwise study it. Graduate students and teachers : Demonstrate solid pedagogical theory! Act as if you're teaching this course for a day. I expect you to participate every day, providing insightful comments and questions while encouraging those less inclined to participate - but not to dominate the discussions. Base value: 5 x 2 weeks = 10 points.

If you suffer from social anxiety, please talk to me so we can work out an alternative to leading discussions. Papers and ProjectsIn addition to good participation, much of your grade depends on the short response papers you write on a weekly basis, your mid-term paper, plus the longer research project. If you use non-standard software to create your projects, save them in standard formats (I prefer .doc format files, but I'll accept .docx .html, .rtf, and .pdf formats as needed). Turn in papers via Blackboard before class begins on the due date or by end of day on days when we don't meet for class. They will be graded and returned via Blackboard in a reasonable time. Want to enhance your literary-criticism chops and Level Up by incorporating traditional (or novel) lit-crit approaches into your papers? Check out this overview page about " Literary-Criticism Approaches to Studying Science Fiction ." Weekly Response PapersPrior to each class, write a short reading-response paper and turn it in via Blackboard in the "Week [x] Response Paper" slot. Please paste the text from your response into the Submission text box rather than (or in addition to) attaching the document, to make it simpler for me to read everyone's papers each week. Along with participation in each week's discussion, these papers are scored as an important measure of your engagement with the day's topics. This short ( 300-500 words for undergrads, 400-1000 words for graduate students) paper is a brief but thoughtful response to all of the readings for that week. (If you go a little long, that's better than too short, but be kind to your teacher!) Provide your thoughts on the week's assigned works in terms of theme, ideas, character, story, setting, position in the SF canon, influence on other works, and so forth. Don't just provide a plot summary, but instead provide insightful, critical, and thoughtful reflections on the works. When responding to the fiction, ask yourself what the author was trying to say (themes), and how the story responds to the changing times in which it was written. When leading the week's discussion, include your discussion-leader notes as part of your reading response, or in addition to it. As in the discussions, exercise your critical-reading skills when writing these responses; that is, don't just read the fiction simply for pleasure, and don't just accept everything that scholars and critics have written about them as canon. I want to hear how you synthesize new ideas from the assigned materials, your additional readings and other interactions, and your own experiences. Regarding format : Many people use bullets for discussion points, bold the titles of the works you're discussing, or use the titles as headings. Some people write responses that resemble essays, citing the works in tandem, while others merely respond to each individually. However you prefer to handle it is fine, but what's most important is that you've thought through all the works for each day and their relationship to one another as well as to the overall SF genre and its evolution. Tip : Even if you aren't leading the week's discussion, include at least a couple of questions to pose to the class or points to stimulate discussion. I suggest bringing your response to class - especially your questions - to help formulate ideas during discussion. (Also be sure to turn them in via Blackboard in advance of class.) They are usually scored in Blackboard by the following week. Graduate students and teachers: As you might imagine, I expect more from your papers. They should reflect your mastery of the form as well as provide insights worthy of your added experience and education. Additionally, for each topic, please find, read, and respond to an additional work (any length is fine) that matches the week's themes, authors, or so forth. Include your response to this work as part of your regular response paper. If you find it online, provide a link in your response paper. Otherwise, include bibliographic information. Insightfulness and clarity are important. Think about this: If you were teaching this course, what additional short-nonfiction readings might you add to the week's readings to aid the students? What book(s) might you add to the groupings - or what books might you use to replace one of the assigned readings? Keep in mind that the chosen works aren't necessarily the best-ever, but the most representative and influential. Weekly Paper Scoring Base value: 3 points each x 13 = 26 total. Here is how I score the weekly response papers: 0 - no paper, or bad one turned in late. 1 - turned in, but provides no interesting insights and does not convince me you did close readings. 2 - has interesting insights on the readings or convinces me you completed the reading. 3 - convinces me you did all the reading and provides interesting insights. 4 - ( +1 Level Up) references all the required materials and shares thoughtful responses to everything, plus discusses additional materials relevant* to the week's content. That means you could possibly earn one-third bonus over the base score for your Weekly Responses by Leveling Up every week! Up to +13 . * Some examples of additional materials to cover in your response paper include a short story, an episode of a show, a comic (issue of a printed comic or multi-page online comic), an SF event (convention, book-club gathering, book release or reading, significant fan event, or so on), a movie, browsing through (with intent, using your critical skills) a large series of art pieces (such as paintings, sculptures, photographs, and the like), or so forth. You can also count something that you actively create and share with others, such as fanfiction, fan-art, thoughtful blogging, or so forth. This is something that should take the average person at least an hour or two to fully appreciate, consider, and respond to (yes, I have a pretty solid gauge for this). If you've created something that's posted online, just turn in a direct link to it. Please use standard file formats; don't make me have to buy or download software just to see it, or set up an account just to read it. Late papers get -1 point each if turned in after the relevant class session begins. Turn them in on time! Missing response papers are due ASAP, at the very latest during Finals Week . Here is how I score the weekly papers, based on 0-4 points each: 0 - no paper. 1 - paper turned in, but does not convince me that you did all of the reading. 2 - paper convinces me that you did some of the reading. 3 - paper either has interesting insights on most of the readings or convinces me that you did all of the reading. 4 - paper convinces that you did all the reading and provides interesting insights. Missing response papers are due ASAP, at the very latest during Finals Week at a reduced score. Late papers lose 1 point if turned in after class sessions or up to one week late; after that, they might lose more. Turn them in on time!  Mid-Term PaperDuring the semester, choose either a pair of readings from the syllabus or equivalent new ones, perform additional research beyond the required materials for that topic, and write a short, formal paper about them or their themes. Additionally , cover at least three more short pieces or at least one book- or movie-length piece; these may be fiction, nonfiction, multimedia, or other sources that support or illustrate your themes. Think of this project as an extended weekly response with additional support and a bibliography and other references as appropriate (Wikipedia is not a source, but is often a good place to find sources), or a formal paper that uses those works to make an argument or provide interesting insights into SF or its evolution over the years. This paper must be at least 1000 words for undergraduates, at least 2000 words for graduate students , up to a max of 4000 words for undergraduates or 6000 words for graduates (again, longer is okay, just consider how much your teacher needs to read). They are graded on the quality of writing (including grammar and spelling), thesis and argument, diversity of research, and how interesting you make it. Format your bibliography as appropriate for your field of study ( MLA for most Humanities, Chicago for most other fields, and so forth; here's a good list of style guides ). References, bibliographies, artist's statements, and endnote pages do not count toward your word-count. Some resources you might find useful:

Graduate students : In addition to the basics of writing an insightful paper, I expect you to demonstrate mastery of the form. NOTE : This paper takes the place of your regular reading-response paper for one week, but be sure to turn it in to the Blackboard Assignment called " Mid-Term Paper ," not the regular weekly response paper slot. You must leave a note in that week's response assignment slot letting me know that you are turning in your Mid-Term Paper in place of that week's response so I don't think you're missing that response. Due date : You may turn in your paper as early as Week 2 or as late as Week 10; you need not turn this in on the same week that the reading response would be due, but it's due by Week 10 at the latest . Base value: 40 points .

A late Mid-Term Paper gets -2 points per day late for the first five days late (that's -10 after a week), then -2 points per day late after that. "Late" is after Thursday of Week 10. Turn them in on time! Missing papers are due ASAP, at the very latest during Finals Week (at a deduction). Group PresentationThe two last sessions of the course are reserved for student oral or multimedia presentations. Here's your chance to pitch your great idea for the in-class presentation project, build teams, chat, and otherwise prep for the last two class sessions. Your job is to share your understanding of SF through a live or multimedia presentation to your classmates. You can present about particular SF works, genre movements, films, TV shows, other other topics - it's up to you! To help focus your efforts, answer this question: What's the "big picture" you've taken away about science fiction, especially the SF novel? How have you come to understand how SF reflects the human experience when encountering change? Especially strive to elucidate what SF means to you as a group, or how it informs the future as you see it, and share your unique insights into what you see as the future of speculative fiction. The form of the presentation is open: Feel free to make it a panel discussion, debate, movie, live game, quiz-show, radio play, skit, guided interactive activity, or other form. Let your imagination run free! This is a great opportunity to express yourself and your understanding of science fiction and its history as well as its future shape, its creators and creative side, ideas and inspirations, and so forth. Form up with a group of students ( 3-5 is optimal ), and present for a total of about 6 minutes per group member ; that is, a 4-person group presents for 24 minutes, while a 5-person group presents for about 30 minutes. If you're showing a short (5-20 minute) film you created, bring discussion prompts for afterward. Your group chooses a topic that illustrates or dramatizes what you all feel is important about science fiction, works together to develop the idea into a shape suitable for sharing with others, then presents it to the class. Be polite: Don't run over your time limit! We'll have a little extra time after each presentation for a short Q&A session. Every group member provides an equal level of participation overall, including research, preparation, and presentation. You may decide if one member is more of a script-writer or video-editor than actor or presenter, for example, as long as everyone's work is balanced - just let me know how you divided the work in the Submission notes section of the Blackboard assignment slot. You may divide your total number of minutes among the presenters however you see fit; let me know how each participated in the project if you're not dividing your live-presentation time equally. Each individual within the group is graded on the clarity and organization of the presentation, the quality of the analysis, the appropriate use of reference material, and individual contribution. Turn this in via Blackboard if possible, or post a link to where it lives online if not. The majority of how I score this project comes from experiencing your live presentation. Base value: 40 points . Help make this group project outstanding - and be a great individual contributor - to Level Up! ( up to +6 ) Final ProjectThe final project can be a traditional essay, a set of teaching materials, or a creative work. Your project explores a topic in science fiction, preferably something not listed in the syllabus or discussed in class - though you may pursue those if you select an angle we didn't already cover or discuss. Projects must be at least 2000 words for undergraduates (max of max of 7500 words), 3000 words for graduate students (max of 10,000 words) . Non-text-based projects must clearly demonstrate a similar level of effort. To help focus your efforts, answer or consider these questions:

Share your unique insights into what you see as the future of speculative fiction. Especially strive to elucidate what SF means to you , or how it informs the future as you see it. Discuss as usual in a scholarly piece, or define in your creative piece's artist statement. You must include an alphabetized bibliography with a traditional paper or lesson plan, or an annotated bibliography at the end of your document if it is a creative work. An annotated bibliography is a set of references that provide a summary of your readings and research, to give me an idea of where you got your inspiration, scientific or technical resources, and so forth. List your sources alphabetically and include a brief summary or annotation for each work that you quote in the paper or that you use as a reference (or inspiration). Format your bibliography as appropriate for your field of study ( MLA for much of the Humanities, Chicago for most other fields, and so forth; here's a good list of style guides ). Turn in this project via Blackboard . Grad students : In addition to the basics of writing an insightful paper, I expect you to demonstrate mastery of the form. References, bibliographies, artist's statements, and endnote pages do not count toward your word-count. Base value: 80 points . Some suggestions for exceeding the base points on this project:

A late Final Project gets -4 points per day late up to a max of -16. "Late" is any time after the due date. Option A: Traditional PaperI grade formal papers on the quality and diversity of research (both fictional and non-fictional), the writing (including grammar and spelling), and the strength of the topic and argument. What I most want is for you to demonstrate what you've learned from the course readings, your outside readings, and in-class discussions, and how you express this synthesis: Demonstrate your understanding of science fiction and the development of the SF novel. Format your bibliography as appropriate for your field of study ( MLA for much of the Humanities, Chicago for most other fields, and so forth; here's a good list of style guides ). This is not something that you can successfully complete at the last minute. The research paper represents a semester-long investigation of topics that interest you. If you wish to use works from the assigned readings that we discussed in class, I expect you to have something new to say that we didn't already discuss. Option B: Course Outline, Lesson Plan, or Study GuideParticipants who choose this option are often teachers and those pursuing that profession. Choose from these three options or provide another option that fits your pedagogical approach:

All of these options make wonderful additions to AboutSF! I encourage you to share this project with other teachers via this educational-outreach program. Option C: Creative WorkA creative work (story, series of poems, play, short film, collection of artworks, website, creative nonfiction, or so forth) must dramatize how the ideas and themes posed in your work might affect believable, interesting characters living in a convincing, fully realized world in addition to revealing substantial understanding of the science fiction genre. For the purposes of this course, your annotated bibliography (normally not included in creative work) is particularly important if you pursue this option, because I want to see the diversity of readings that helped you develop your work (both fictional and non-fictional). Show your research with a good annotated bibliography, demonstrate your understanding of science fiction, and make your creative work stand on its own. To be crystal-clear in defining how your creative work displays your understanding of SF, its history, its future, and your response to it, also include an " artist's statement ," as it very much helps in evaluating creative work. Write this either as an appendix to your document (but don't count this toward your word-count) or paste it into the Notes to Instructor text box of the Blackboard assignment. If you're creating a multimedia project, please post to an appropriate media host - give me a link to where your project lives, and upload to Blackboard your annotated bibliography and artist's statement, as well. Be aware that this option is more challenging - especially if you haven't taken creative-writing courses - because I expect the same level of research as in the other options plus a good story or other creative expression. Click here for some useful creative-writing resources . Final Project DeadlineYour final project is due by Thursday of Finals Week, before 5:00pm . The completed project is due via Blackboard . If you've created a website, posted a short film to the internet, or otherwise cannot upload the project directly, just provide a link (website URL) to where I can find the project online in the Submission section of the appropriate Blackboard Final Project assignment slot. Your course grade is based upon these factors. Out of a possible 210 (approximate) points:

I want you to be in control of your scores as much as possible, so I've adopted a you-centered method for tracking success (in the academic world, it's called " incentive-centered grading " or " gamification "). Everything you do in this course beyond the basics of the required elements earns you points toward "leveling up" your scores (and, therefore, your grade), while giving you some freedom to choose between options. Your final grade is up to you! By simply completing all the readings, turning in excellent responses on time each week, creating an well-written mid-term project, doing a good job in the group presentation, creating a good final project, attending every class plus engaging in active discussion while there, and partnering to lead at least two class sessions, you are pretty much guaranteed at least a C+ or better for your final grade. Want to reach higher and earn a better grade? See the Level Up! section below and throughout the syllabus. Level Points Needed Grade Legend 309 or above A Hero 298 - 308 A- Master 287 - 297 B+ Guru 276 - 286 B Expert 265 - 275 B- Adept (base) 254 - 264 C+ Apprentice 243 - 253 C Intern 232 - 242 C- Trainee 221 - 231 D+ Novice 210 - 220 D Beginner 199 - 209 D- Conscript 198 or below F So if you're comfortable rising no higher "Adept" (a letter grade of C+ ), you need between 254 and 264 points. You'll easily earn those points by doing solid work on the required course components:

But you have lots of chances to Level Up throughout the semester, making it easy to greatly grow your level. See each section for details on Level Ups and Penalties . See the next section, Chloe's Example Scenario , and every other section for more opportunities. TOTAL possible Level Up points: +79 or more! Graduate students : I have additional expectations for you - see my comments directed to you throughout this document! We use the metaphor of Leveling Up to earn better-than-average grades (think game systems). In place of the traditional deductive-only grade system (where you lose points by not turning in perfect work), our system uses additive grading (which is gaining a lot of pedagogical traction in education theory). You'll have a multitude of opportunities to earn bonus points by (for example) doing additional research, reporting on that added work, and sharing your discoveries in class. You can also Level Up for exceeding my expectations on every project and in every class period; that is, you get more points than the base value when you exceed "average effort" (traditionally graded as C work), thereby raising your grade incrementally toward a B or A. It's up to you! On the other hand, if you choose to simply meet all the basic requirements and do acceptable work on your projects, you'll end up with a grade around a C+. I want you to be in control over your final grade, using a familiar and empowering metaphor. So, want to earn a higher grade in this course? Each section in this syllabus offers some options for Leveling Up! Possible bonuses abound: See each assignment section for details on more ways to earn bonus points. Here are some semester-long examples of how you can gain extra points:

Basically, be an epic student! You might just get bonus points in the end. On the other hand, just like in many game-scoring systems, in this course you have a few ways to lose points, too:

What's My Grade? Chloe's Example Scenario.If you're not familiar with this sort of process (perhaps you've never played a video or role-playing game!), you can determine your progress toward higher grade (aka higher level) as in this example:

She's already Leveled Up from Conscript to Beginner... and she's only a little past half-way through the semester! If she Levels Up her Presentation (let's say she gets 44 points) and Final Project (she kicks it and gets 89 points) in the ways she usually does, that alone is enough to elevate her to Legend level. So, assuming she's just as motivated for the rest of the semester, she'll easily rise through the ranks to Legend status and beyond: Last year, three motivated students earned more than 300 points! You can, too. More Good StuffReady for more? Check out these suggestions. Events and ActivitiesWant to hang out (at least virtually) with other SF folks? See the Lawrence Science Fiction Club on Facebook for details. Check out some of these multimedia offerings. Click here to see them on this site , or click here to see our YouTube channel . Benjamin Cartwright, former Volunteer Coordinator AboutSF, created a wonderful podcast program. Check it out at the AboutSF main page or at our Podomatic site ! To learn about more stuff, more quickly, you can also find events and lots of SF-related chat with the Lawrence Science Fiction Club! Info, discussions, and (hopefully soon!) meeting times are regularly posted at our Facebook page . Know of something of interest to like-minded folks? Join and drop a note there! Here's a cool event each Spring, right after Spring finals: Spectrum Fantastic Art Live Show Friday and Saturday, in mid-May Also the Spectrum Awards Show Grand Ballroom of Bartle Hall Convention Center Kansas City, MO What are you doing on Memorial Day Weekend? Why not attend the ConQuest science fiction convention in Kansas City. Sticking around for the summer? Don't miss the annual Campbell Conference and Awards weekend in June. Want to take more speculative-fiction courses? Check out my growing list of offerings . Go here to see lots more resources . More Recommended ReadingsWant to read more SF? You've come to the right place! Our lending library holds many books, magazines, and more, so if you are local to Lawrence or are in town for our other summer programs, check with McKitterick to see if we can lend you a copy. These are available on a first-come, first-served basis. We also have a course-specific lending library for the SF Literature course - which is primarily supplied by previous students donating copies after completing their course - so if you want to pass on the love to the next generation rather than keep your books, let your teacher know! Want more? Check out the winners of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for best SF novel of the year . To see even more great books, check out the recent finalists for the Campbell Memorial Award - most years, the majority of those works could have won the award if the jury had just a few different members. For short fiction, check out the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award for best short SF winners, and the recent Sturgeon Award finalists . As with the Campbell, you're likely to find something you'll love among the finalists - and many of them live online, and you'll find links to the stories from that page. Slate 's Future Tense Fiction series is pretty cool - all about the consequences and side-effects of tech on human life. Here's their nonfiction section on the same topic. The Guardian asked some of SF's greatest living authors to share what they feel are the best books or authors in the genre, and what they came up with is a brilliant list . Want lots of free SF ebooks and e-zines? Check out Project Gutenberg's growing SF collection . Want even more recommendations? My and James Gunn's " A Basic Science Fiction Library " is a go-to internet resource for building reading lists. It's organized by author. We hold many books, so if you are local to Lawrence or are in town for our other summer programs, check with me to see if we can lend you a copy. These are available on a first-come, first-served basis. This lending library is primarily supplied by previous students donating copies after completing their courses, so if you want to pass on the love to the next generation rather than keep your books, let your teacher know! Want to take more speculative-fiction courses? You're in luck! Check out my growing list of offerings . Go here to see lots more resources on this site. If you like novels, or just want to prepare for next year's SF-novels version of this course, here you go:

Here are the books removed from the SF-novels reading list - still important and recommended works for understanding the history of the SF novel, but we only have so much time:

McKitterick was on Minnesota Public Radio's " The Daily Circuit " show in June 2012, which was a "summer reading" show dedicated to spec-fic and remembering Ray Bradbury. Great to see Public Radio continuing to cover SF after their "100 Best SF Novels" list . Here's what he added to the show's blog : A great resource for finding wonderful SF is to check out the winners and finalists for the major awards. For example, here's a list of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award winners. And here's a list of recent finalists for the Award. Here's the list of the Nebula Award novel winners . And the Hugo Award winners , which has links to each year's finalists, as well. A couple of books I didn't get a chance to mention include Ray Bradbury's R Is for Rocket , which contains a story that turned me into an author: "The Rocket" (along with Heinlein's Rocketship Galileo and Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time ). Bradbury's Dandelion Wine is another, along with books like Frank Herbert's Dune , Douglas Adams' The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy , Clifford Simak's City (a Minnesota native), SF anthologies like James Gunn's Road to Science Fiction and the DAW Annual Year's Best SF , and tons more. Personally, my favorite Bradbury short story is pretty much everything Bradbury every wrote. His writing is moving and evocative like Simak and Theodore Sturgeon's - probably why those three made such an impression on the young-me. But if I had to pick only one that most influenced me as a writer, it would probably be "The Rocket," a beautiful story about a junk-man who has to decide between his personal dreams of space and love of his family. It was adapted into a radio show for NBC's "Short Story" series (you can listen to the MP3 audio recording here ). He was on again in September 2012, when they did a story on " What did science fiction writers predict for 2012? " The other guest was a futurist - an interesting discussion! Stay tuned for more to come! * "' History of Science Fiction ' is a graphic chronology that maps the literary genre from its nascent roots in mythology and fantastic stories to the somewhat calcified post-Star Wars space opera epics of today. The movement of years is from left to right, tracing the figure of a tentacled beast, derived from H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds Martians. Science Fiction is seen as the offspring of the collision of the Enlightenment (providing science) and Romanticism, which birthed gothic fiction, source of not only SF, but crime novels, horror, westerns, and fantasy (all of which can be seen exiting through wormholes to their own diagrams, elsewhere). Science fiction progressed through a number of distinct periods, which are charted, citing hundreds of the most important works and authors. Film and television are covered as well." - Ward Shelly discussing this excellent " History of Science Fiction " infographic - now available for purchase ! Extra CreditOccasionally, we will offer opportunities for you to earn extra credit. We will add these to Blackboard as events become available - and let us know if you've heard about an upcoming opportunity! A good place to look for upcoming talks is the KU Calendar . No one is required to attend these events, so any points you get for reporting on your attendance are added to your overall score. Here's an excellent opportunity coming up very soon: Percival's Planet and Clyde Tombaugh's Discovery of Pluto An Evening With Michael Byers Tuesday, April 19 6:30 - 9:30pm For this event, be sure to check out the excerpts posted on Blackboard. Click the image to open the full-size poster. As a guide for things you might find on your own, here are some events students attended previously: A couple of exhibits at campus museums are relevant to the course. We offer extra credit to students who explore these exhibits and submit a response paper. (These papers add to your total score in the class, often making up for missed papers or low scores.) You are expected to commit an hour or more with an exhibit, plus whatever time it takes to write up the one-page response paper. Maximum point value per exhibit is equivalent to a regular response paper. Recent exhibits have included:

Your response paper should discuss the event or exhibit similarly to how you discuss the weekly readings. Feel free to bring your thoughts to the relevant in-class discussions. Turn in these extra credit papers within a week of the event ; the final deadline is May 18 . If you have any questions, you can either ask us in class or send an email.

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.  View Full Resolution  Science Fiction Studies In this Issue

Science Fiction Studies is a refereed scholarly journal devoted to the study of the genre of science fiction, broadly defined. It publishes articles about science fiction and book reviews on science fiction criticism; it does not publish fiction. SFS is widely considered to be the premier academic journal in its field, with strong theoretical, historical, and international coverage. Roughly one-third of its issues to date have been special issues, with recent topics including Technoculture and Science Fiction, Afrofuturism, Latin American Science Fiction, and Animal Studies and Science Fiction. Founded in 1973, SFS is based at DePauw University and appears three times per year in March, July, and November. published byViewing issue, table of contents.