Bill of Rights Project: Gordon: Thesis Statement

- Thesis Statement

- Creating the Outline

- Bibliography & Chicago Style

- A Note on Plagiarism

What is a Thesis Statement?

What is a thesis statement*.

A thesis statement:

- Tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter.

- Is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- Remember: A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war.

- Makes a claim that others might dispute, takes a side.

- Is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

* The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill [http://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/]

Questions to ask yourself when creating a Thesis Statement

Need help narrowing your research into a thesis statement? Try asking yourself these questions to help bring your ideas into focus:*

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question.

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

- << Previous: Resources

- Next: Creating the Outline >>

- Last Updated: Jan 15, 2020 8:38 AM

- URL: https://macduffie.libguides.com/c.php?g=754104

Bill of Rights

Primary tabs.

- First Amendment [Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, Petition (1791)] (see explanation )

- Second Amendment [Right to Bear Arms (1791)] (see explanation )

- Third Amendment [Quartering of Troops (1791)] (see explanation )

- Fourth Amendment [Search and Seizure (1791)] (see explanation )

- Fifth Amendment [Grand Jury, Double Jeopardy, Self-Incrimination, Due Process (1791)] (see explanation )

- Sixth Amendment [Criminal Prosecutions - Jury Trial, Right to Confront and to Counsel (1791)] (see explanation )

- Seventh Amendment [Common Law Suits - Jury Trial (1791)] (see explanation )

- Eighth Amendment [Excess Bail or Fines, Cruel and Unusual Punishment (1791)] (see explanation )

- Ninth Amendment [Non-Enumerated Rights (1791)] (see explanation )

- Tenth Amendment [Rights Reserved to States or People (1791)] (see explanation )

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, the declaration, the constitution, and the bill of rights.

by Jeffrey Rosen and David Rubenstein

At the National Constitution Center, you will find rare copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. These are the three most important documents in American history. But why are they important, and what are their similarities and differences? And how did each document, in turn, influence the next in America’s ongoing quest for liberty and equality?

There are some clear similarities among the three documents. All have preambles. All were drafted by people of similar backgrounds, generally educated white men of property. The Declaration and Constitution were drafted by a congress and a convention that met in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia (now known as Independence Hall) in 1776 and 1787 respectively. The Bill of Rights was proposed by the Congress that met in Federal Hall in New York City in 1789. Thomas Jefferson was the principal drafter of the Declaration and James Madison of the Bill of Rights; Madison, along with Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson, was also one of the principal architects of the Constitution.

Most importantly, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are based on the idea that all people have certain fundamental rights that governments are created to protect. Those rights include common law rights, which come from British sources like the Magna Carta, or natural rights, which, the Founders believed, came from God. The Founders believed that natural rights are inherent in all people by virtue of their being human and that certain of these rights are unalienable, meaning they cannot be surrendered to government under any circumstances.

At the same time, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are different kinds of documents with different purposes. The Declaration was designed to justify breaking away from a government; the Constitution and Bill of Rights were designed to establish a government. The Declaration stands on its own—it has never been amended—while the Constitution has been amended 27 times. (The first ten amendments are called the Bill of Rights.) The Declaration and Bill of Rights set limitations on government; the Constitution was designed both to create an energetic government and also to constrain it. The Declaration and Bill of Rights reflect a fear of an overly centralized government imposing its will on the people of the states; the Constitution was designed to empower the central government to preserve the blessings of liberty for “We the People of the United States.” In this sense, the Declaration and Bill of Rights, on the one hand, and the Constitution, on the other, are mirror images of each other.

Despite these similarities and differences, the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are, in many ways, fused together in the minds of Americans, because they represent what is best about America. They are symbols of the liberty that allows us to achieve success and of the equality that ensures that we are all equal in the eyes of the law. The Declaration of Independence made certain promises about which liberties were fundamental and inherent, but those liberties didn’t become legally enforceable until they were enumerated in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In other words, the fundamental freedoms of the American people were alluded to in the Declaration of Independence, implicit in the Constitution, and enumerated in the Bill of Rights. But it took the Civil War, which President Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address called “a new birth of freedom,” to vindicate the Declaration’s famous promise that “all men are created equal.” And it took the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868 after the Civil War, to vindicate James Madison’s initial hope that not only the federal government but also the states would be constitutionally required to respect fundamental liberties guaranteed in the Bill of Rights—a process that continues today.

Why did Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence?

When the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in 1775, it was far from clear that the delegates would pass a resolution to separate from Great Britain. To persuade them, someone needed to articulate why the Americans were breaking away. Congress formed a committee to do just that; members included John Adams from Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin from Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman from Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston from New York, and Thomas Jefferson from Virginia, who at age 33 was one of the youngest delegates.

Although Jefferson disputed his account, John Adams later recalled that he had persuaded Jefferson to write the draft because Jefferson had the fewest enemies in Congress and was the best writer. (Jefferson would have gotten the job anyway—he was elected chair of the committee.) Jefferson had 17 days to produce the document and reportedly wrote a draft in a day or two. In a rented room not far from the State House, he wrote the Declaration with few books and pamphlets beside him, except for a copy of George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights and the draft Virginia Constitution, which Jefferson had written himself.

The Declaration of Independence has three parts. It has a preamble, which later became the most famous part of the document but at the time was largely ignored. It has a second part that lists the sins of the King of Great Britain, and it has a third part that declares independence from Britain and that all political connections between the British Crown and the “Free and Independent States” of America should be totally dissolved.

The preamble to the Declaration of Independence contains the entire theory of American government in a single, inspiring passage:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

When Jefferson wrote the preamble, it was largely an afterthought. Why is it so important today? It captured perfectly the essence of the ideals that would eventually define the United States. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” Jefferson began, in one of the most famous sentences in the English language. How could Jefferson write this at a time that he and other Founders who signed the Declaration owned slaves? The document was an expression of an ideal. In his personal conduct, Jefferson violated it. But the ideal—“that all men are created equal”—came to take on a life of its own and is now considered the most perfect embodiment of the American creed.

When Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address during the Civil War in November 1863, several months after the Union Army defeated Confederate forces at the Battle of Gettysburg, he took Jefferson’s language and transformed it into constitutional poetry. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” Lincoln declared. “Four score and seven years ago” refers to the year 1776, making clear that Lincoln was referring not to the Constitution but to Jefferson’s Declaration. Lincoln believed that the “principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society,” as he wrote shortly before the anniversary of Jefferson’s birthday in 1859. Three years later, on the anniversary of George Washington’s birthday in 1861, Lincoln said in a speech at what by that time was being called “Independence Hall,” “I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender” the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

It took the Civil War, the bloodiest war in American history, for Lincoln to begin to make Jefferson’s vision of equality a constitutional reality. After the war, the Declaration’s vision was embodied in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, which formally ended slavery, guaranteed all persons the “equal protection of the laws,” and gave African-American men the right to vote. At the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, when supporters of gaining greater rights for women met, they, too, used the Declaration of Independence as a guide for drafting their Declaration of Sentiments. (Their efforts to achieve equal suffrage culminated in 1920 in the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.) And during the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said in his famous address at the Lincoln Memorial, “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In addition to its promise of equality, Jefferson’s preamble is also a promise of liberty. Like the other Founders, he was steeped in the political philosophy of the Enlightenment, in philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, Francis Hutcheson, and Montesquieu. All of them believed that people have certain unalienable and inherent rights that come from God, not government, or come simply from being human. They also believed that when people form governments, they give those governments control over certain natural rights to ensure the safety and security of other rights. Jefferson, George Mason, and the other Founders frequently spoke of the same set of rights as being natural and unalienable. They included the right to worship God “according to the dictates of conscience,” the right of “enjoyment of life and liberty,” “the means of acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety,” and, most important of all, the right of a majority of the people to “alter and abolish” their government whenever it threatened to invade natural rights rather than protect them.

In other words, when Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and began to articulate some of the rights that were ultimately enumerated in the Bill of Rights, he wasn’t inventing these rights out of thin air. On the contrary, 10 American colonies between 1606 and 1701 were granted charters that included representative assemblies and promised the colonists the basic rights of Englishmen, including a version of the promise in the Magna Carta that no freeman could be imprisoned or destroyed “except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” This legacy kindled the colonists’ hatred of arbitrary authority, which allowed the King to seize their bodies or property on his own say-so. In the revolutionary period, the galvanizing examples of government overreaching were the “general warrants” and “writs of assistance” that authorized the King’s agents to break into the homes of scores of innocent citizens in an indiscriminate search for the anonymous authors of pamphlets criticizing the King. Writs of assistance, for example, authorized customs officers “to break open doors, Chests, Trunks, and other Packages” in a search for stolen goods, without specifying either the goods to be seized or the houses to be searched. In a famous attack on the constitutionality of writs of assistance in 1761, prominent lawyer James Otis said, “It is a power that places the liberty of every man in the hands of every petty officer.”

As members of the Continental Congress contemplated independence in May and June of 1776, many colonies were dissolving their charters with England. As the actual vote on independence approached, a few colonies were issuing their own declarations of independence and bills of rights. The Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776, written by George Mason, began by declaring that “all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

When Jefferson wrote his famous preamble, he was restating, in more eloquent language, the philosophy of natural rights expressed in the Virginia Declaration that the Founders embraced. And when Jefferson said, in the first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence, that “[w]hen in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another,” he was recognizing the right of revolution that, the Founders believed, had to be exercised whenever a tyrannical government threatened natural rights. That’s what Jefferson meant when he said Americans had to assume “the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.”

The Declaration of Independence was a propaganda document rather than a legal one. It didn’t give any rights to anyone. It was an advertisement about why the colonists were breaking away from England. Although there was no legal reason to sign the Declaration, Jefferson and the other Founders signed it because they wanted to “mutually pledge” to each other that they were bound to support it with “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” Their signatures were courageous because the signers realized they were committing treason: according to legend, after affixing his flamboyantly large signature John Hancock said that King George—or the British ministry—would be able to read his name without spectacles. But the courage of the signers shouldn’t be overstated: the names of the signers of the Declaration weren’t published until after General George Washington won crucial battles at Trenton and Princeton and it was clear that the war for independence was going well.

What is the relationship between the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution?

In the years between 1776 and 1787, most of the 13 states drafted constitutions that contained a declaration of rights within the body of the document or as a separate provision at the beginning, many of them listing the same natural rights that Jefferson had embraced in the Declaration. When it came time to form a central government in 1776, the Continental Congress began to create a weak union governed by the Articles of Confederation. (The Articles of Confederation was sent to the states for ratification in 1777; it was formally adopted in 1781.) The goal was to avoid a powerful federal government with the ability to invade rights and to threaten private property, as the King’s agents had done with the hated general warrants and writs of assistance. But the Articles of Confederation proved too weak for bringing together a fledgling nation that needed both to wage war and to manage the economy. Supporters of a stronger central government, like James Madison, lamented the inability of the government under the Articles to curb the excesses of economic populism that were afflicting the states, such as Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts, where farmers shut down the courts demanding debt relief. As a result, Madison and others gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 with the goal of creating a stronger, but still limited, federal government.

The Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia in the Pennsylvania State House, in the room where the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Jefferson, who was in France at the time, wasn’t among them. After four months of debate, the delegates produced a constitution.

During the final days of debate, delegates George Mason and Elbridge Gerry objected that the Constitution, too, should include a bill of rights to protect the fundamental liberties of the people against the newly empowered president and Congress. Their motion was swiftly—and unanimously—defeated; a debate over what rights to include could go on for weeks, and the delegates were tired and wanted to go home. The Constitution was approved by the Constitutional Convention and sent to the states for ratification without a bill of rights.

During the ratification process, which took around 10 months (the Constitution took effect when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify in late June 1788; the 13th state, Rhode Island, would not join the union until May 1790), many state ratifying conventions proposed amendments specifying the rights that Jefferson had recognized in the Declaration and that they protected in their own state constitutions. James Madison and other supporters of the Constitution initially resisted the need for a bill of rights as either unnecessary (because the federal government was granted no power to abridge individual liberty) or dangerous (since it implied that the federal government had the power to infringe liberty in the first place). In the face of a groundswell of popular demand for a bill of rights, Madison changed his mind and introduced a bill of rights in Congress on June 8, 1789.

Madison was least concerned by “abuse in the executive department,” which he predicted would be the weakest branch of government. He was more worried about abuse by Congress, because he viewed the legislative branch as “the most powerful, and most likely to be abused, because it is under the least control.” (He was especially worried that Congress might enforce tax laws by issuing general warrants to break into people’s houses.) But in his view “the great danger lies rather in the abuse of the community than in the legislative body”—in other words, local majorities who would take over state governments and threaten the fundamental rights of minorities, including creditors and property holders. For this reason, the proposed amendment that Madison considered “the most valuable amendment in the whole list” would have prohibited the state governments from abridging freedom of conscience, speech, and the press, as well as trial by jury in criminal cases. Madison’s favorite amendment was eliminated by the Senate and not resurrected until after the Civil War, when the 14th Amendment required state governments to respect basic civil and economic liberties.

In the end, by pulling from the amendments proposed by state ratifying conventions and Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights, Madison proposed 19 amendments to the Constitution. Congress approved 12 amendments to be sent to the states for ratification. Only 10 of the amendments were ultimately ratified in 1791 and became the Bill of Rights. The first of the two amendments that failed was intended to guarantee small congressional districts to ensure that representatives remained close to the people. The other would have prohibited senators and representatives from giving themselves a pay raise unless it went into effect at the start of the next Congress. (This latter amendment was finally ratified in 1992 and became the 27th Amendment.)

To address the concern that the federal government might claim that rights not listed in the Bill of Rights were not protected, Madison included what became the Ninth Amendment, which says the “enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” To ensure that Congress would be viewed as a government of limited rather than unlimited powers, he included the 10th Amendment, which says the “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Because of the first Congress’s focus on protecting people from the kinds of threats to liberty they had experienced at the hands of King George, the rights listed in the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights apply only to the federal government, not to the states or to private companies. (One of the amendments submitted by the North Carolina ratifying convention but not included by Madison in his proposal to Congress would have prohibited Congress from establishing monopolies or companies with “exclusive advantages of commerce.”)

But the protections in the Bill of Rights—forbidding Congress from abridging free speech, for example, or conducting unreasonable searches and seizures—were largely ignored by the courts for the first 100 years after the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791. Like the preamble to the Declaration, the Bill of Rights was largely a promissory note. It wasn’t until the 20th century, when the Supreme Court began vigorously to apply the Bill of Rights against the states, that the document became the centerpiece of contemporary struggles over liberty and equality. The Bill of Rights became a document that defends not only majorities of the people against an overreaching federal government but also minorities against overreaching state governments. Today, there are debates over whether the federal government has become too powerful in threatening fundamental liberties. There are also debates about how to protect the least powerful in society against the tyranny of local majorities.

What do we know about the documentary history of the rare copies of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights on display at the National Constitution Center?

Generally, when people think about the original Declaration, they are referring to the official engrossed —or final—copy now in the National Archives. That is the one that John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, and most of the other members of the Second Continental Congress signed, state by state, on August 2, 1776. John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer, published the official printing of the Declaration ordered by Congress, known as the Dunlap Broadside, on the night of July 4th and the morning of July 5th. About 200 copies are believed to have been printed. At least 27 are known to survive.

The document on display at the National Constitution Center is known as a Stone Engraving, after the engraver William J. Stone, whom then Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned in 1820 to create a precise facsimile of the original engrossed version of the Declaration. That manuscript had become faded and worn after nearly 45 years of travel with Congress between Philadelphia, New York City, and eventually Washington, D.C., among other places, including Leesburg, Virginia, where it was rolled up and hidden during the British invasion of the capital in 1814.

To ensure that future generations would have a clear image of the original Declaration, William Stone made copies of the document before it faded away entirely. Historians dispute how Stone rendered the facsimiles. He kept the original Declaration in his shop for up to three years and may have used a process that involved taking a wet cloth, putting it on the original document, and creating a perfect copy by taking off half the ink. He would have then put the ink on a copper plate to do the etching (though he might have, instead, traced the entire document by hand without making a press copy). Stone used the copper plate to print 200 first edition engravings as well as one copy for himself in 1823, selling the plate and the engravings to the State Department. John Quincy Adams sent copies to each of the living signers of the Declaration (there were three at the time), public officials like President James Monroe, Congress, other executive departments, governors and state legislatures, and official repositories such as universities. The Stone engravings give us the clearest idea of what the original engrossed Declaration looked like on the day it was signed.

The Constitution, too, has an original engrossed, handwritten version as well as a printing of the final document. John Dunlap, who also served as the official printer of the Declaration, and his partner David C. Claypoole, who worked with him to publish the Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser , America’s first successful daily newspaper founded by Dunlap in 1771, secretly printed copies of the convention’s committee reports for the delegates to review, debate, and make changes. At the end of the day on September 15, 1787, after all of the delegations present had approved the Constitution, the convention ordered it engrossed on parchment. Jacob Shallus, assistant clerk to the Pennsylvania legislature, spent the rest of the weekend preparing the engrossed copy (now in the National Archives), while Dunlap and Claypoole were ordered to print 500 copies of the final text for distribution to the delegates, Congress, and the states. The engrossed copy was signed on Monday, September 17th, which is now celebrated as Constitution Day.

The copy of the Constitution on display at the National Constitution Center was published in Dunlap and Claypoole’s Pennsylvania Packet newspaper on September 19, 1787. Because it was the first public printing of the document—the first time Americans saw the Constitution—scholars consider its constitutional significance to be especially profound. The publication of the Constitution in the Pennsylvania Packet was the first opportunity for “We the People of the United States” to read the Constitution that had been drafted and would later be ratified in their name.

The handwritten Constitution inspires awe, but the first public printing reminds us that it was only the ratification of the document by “We the People” that made the Constitution the supreme law of the land. As James Madison emphasized in The Federalist No. 40 in 1788, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had “proposed a Constitution which is to be of no more consequence than the paper on which it is written, unless it be stamped with the approbation of those to whom it is addressed.” Only 25 copies of the Pennsylvania Packet Constitution are known to have survived.

Finally, there is the Bill of Rights. On October 2, 1789, Congress sent 12 proposed amendments to the Constitution to the states for ratification—including the 10 that would come to be known as the Bill of Rights. There were 14 original manuscript copies, including the one displayed at the National Constitution Center—one for the federal government and one for each of the 13 states.

Twelve of the 14 copies are known to have survived. Two copies —those of the federal government and Delaware — are in the National Archives. Eight states currently have their original documents; Georgia, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania do not. There are two existing unidentified copies, one held by the Library of Congress and one held by The New York Public Library. The copy on display at the National Constitution Center is from the collections of The New York Public Library and will be on display for several years through an agreement between the Library and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania; the display coincides with the 225th anniversary of the proposal and ratification of the Bill of Rights.

The Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are the three most important documents in American history because they express the ideals that define “We the People of the United States” and inspire free people around the world.

Read More About the Constitution

The constitutional convention of 1787: a revolution in government, on originalism in constitutional interpretation, democratic constitutionalism, modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Why was the Bill of Rights added?

How was the bill of rights added to the u.s. constitution, does the bill of rights apply to the states.

- Does the Second Amendment allow owning guns for self-defense?

- Which U.S. Supreme Court justices think the Second Amendment recognizes the individual’s right to bear arms in self-defense?

Bill of Rights

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- U.S. History - The Bill of Rights

- Online Library of Liberty - 1791: US Bill of Rights (1st 10 Amendments) - with commentary

- UShistory.org - Historic Documents - Bill of Rights and Later Amendments

- Cornell University Law School - Legal Information Institute - Bill of Rights

- Khan Academy - The Bill of Rights

- Bill of Rights Institute - Bill of Rights of the United States of America (1791)

- The Free Speech Center - Bill of Rights

- Social Science LibreTexts - The Bill of Rights

- National Archives - Bill of Rights

What is the Bill of Rights?

The Bill of Rights is the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution , adopted as a single unit in 1791. It spells out the rights of the people of the United States in relation to their government.

Three delegates to the Constitutional Convention , most prominently George Mason , did not sign the U.S. Constitution largely because it lacked a bill of rights. He was among those arguing against ratification of the document because of that omission, and several states ratified it only on the understanding that a bill of rights would be quickly added.

James Madison drew on the Magna Carta , the English Bill of Rights , and Virginia ’s Declaration of Rights , mainly written by George Mason , in drafting 19 amendments, which he submitted to the U.S. House of Representatives on June 8, 1789. The House approved 17 of them and sent it to the U.S. Senate , which approved 12 of them on September 25. Ten were ratified by the states and became law on December 15, 1791.

How does the Bill of Rights protect individual rights?

The Bill of Rights says that the government cannot establish a particular religion and may not prohibit people or newspapers from expressing themselves. It also sets strict limits on the lengths that government may go to in enforcing laws . Finally, it protects unenumerated rights of the people.

Originally, the Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government. (One of the amendments that the U.S. Senate rejected would have applied those rights to state laws as well.) However, the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) did forbid states to abridge the rights of any citizen without due process, and, beginning in the 20th century, the U.S. Supreme Court gradually applied most of the guarantees of the Bill of Rights to state governments as well.

Recent News

Bill of Rights , in the United States , the first 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution , which were adopted as a single unit on December 15, 1791, and which constitute a collection of mutually reinforcing guarantees of individual rights and of limitations on federal and state governments.

The Bill of Rights derives from the Magna Carta (1215), the English Bill of Rights (1689), the colonial struggle against king and Parliament , and a gradually broadening concept of equality among the American people. Virginia’s 1776 Declaration of Rights, drafted chiefly by George Mason , was a notable forerunner. Besides being axioms of government, the guarantees in the Bill of Rights have binding legal force. Acts of Congress in conflict with them may be voided by the U.S. Supreme Court when the question of the constitutionality of such acts arises in litigation ( see judicial review ).

The Constitution in its main body forbids suspension of the writ of habeas corpus except in cases of rebellion or invasion (Article I, section 9); prohibits state or federal bills of attainder and ex post facto laws (I, 9, 10); requires that all crimes against the United States be tried by jury in the state where committed (III, 2); limits the definition, trial, and punishment of treason (III, 3); prohibits titles of nobility (I, 9) and religious tests for officeholding (VI); guarantees a republican form of government in every state (IV, 4); and assures each citizen the privileges and immunities of the citizens of the several states (IV, 2).

Popular dissatisfaction with the limited guarantees of the main body of the Constitution expressed in the state conventions called to ratify it led to demands and promises that the first Congress of the United States satisfied by submitting to the states 12 amendments. Ten were ratified. (The second of the 12 amendments, which required any change to the rate of compensation for congressional members to take effect only after the subsequent election in the House of Representatives , was ratified as the Twenty-seventh Amendment in 1992.) Individual states being subject to their own bills of rights, these amendments were limited to restraining the federal government. The Senate refused to submit James Madison ’s amendment (approved by the House of Representatives) protecting religious liberty, freedom of the press, and trial by jury against violation by the states.

Under the First Amendment , Congress can make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise, or abridging freedom of speech or press or the right to assemble and petition for redress of grievances. Hostility to standing armies found expression in the Second Amendment ’s guarantee of the people’s right to bear arms and in the Third Amendment ’s prohibition of the involuntary quartering of soldiers in private houses.

The Fourth Amendment secures the people against unreasonable searches and seizures and forbids the issuance of warrants except upon probable cause and directed to specific persons and places. The Fifth Amendment requires grand jury indictment in prosecutions for major crimes and prohibits double jeopardy for a single offense. It provides that no person shall be compelled to testify against himself and forbids the taking of life, liberty, or property without due process of law and the taking of private property for public use ( eminent domain ) without just compensation . By the Sixth Amendment , an accused person is to have a speedy public trial by jury, to be informed of the nature of the accusation, to be confronted with prosecution witnesses, and to have the assistance of counsel . The Seventh Amendment formally established the right to trial by jury in civil cases. Excessive bail or fines and cruel and unusual punishment are forbidden by the Eighth Amendment . The Ninth Amendment protects unenumerated residual rights of the people, and, by the Tenth , powers not delegated to the United States are reserved to the states or the people.

After the American Civil War (1861–65), slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment , and the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) declared that all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction are citizens thereof. It forbids the states to abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States or to deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Beginning in the early 20th century, the Supreme Court used the due process clause to gradually incorporate, or apply against the states, most of the guarantees contained in the Bill of Rights, which formerly had been understood to apply only against the federal government. Thus, the due process clause finally made effective the major portion of Madison’s unaccepted 1789 proposal.

The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Founding a new nation: the bill of rights.

Bibliography

The original text of the Constitution did not contain a special article or section on civil rights and freedoms, although some of them included separate prescriptions. Namely, a number of important regulations can be found in the text of the Constitution; for example, Section 9 of Article I refers to the prohibition of the suspension of habeas corpus unless public security requires it in the event of an insurrection or invasion. Such negligence of civil rights and freedoms caused great dissatisfaction among democratically-oriented citizens and even jeopardized the ratification of the Constitution. This paper will argue that the Bill of Rights played a rather significant role in democracy and equality establishment based on clarifying rights and freedoms of citizens that are to be guaranteed by the Constitution.

Initially, the Bill of Rights was considered only as a law that protects citizens from the arbitrariness of the federal authorities. It went back to the British Magna Carta of 1215, which legislatively limited the power of the King. 1 During the first session of the Congress gathered to discuss the new Constitution, the politician Madison took the initiative to propose the Bill of Rights even though he believed that the Constitution itself might ensure liberty. In 1789, the first ten amendments convened on the basis of the Constitution were introduced at the suggestion of Madison, which by 1791 were ratified by the states and simultaneously came into force. 2 It seems critical to point out the fact that the amendments that make up the Bill of Rights are equivalent in definition to the legal status of an American citizen.

The review of the mentioned document shows that Locke’s ideas about natural human rights were interwoven with quite objective protection against specific abuses. 3 It is noted that Congress should consider the needs of people. Therefore, while formulating the text of the document, the legislators proceeded from the idea of natural rights and freedoms and the establishment of the limits of the state’s power in relation to a person. The ninth amendment established the principle of the inadmissibility of restricting the rights of citizens, which are not directly mentioned in the Constitution. The third amendment that regulates the order of soldiers in peacetime and wartime seems to be an anachronism in the modern era. The remaining seven amendments referred to political and personal rights and freedoms of a person.

The first amendment proclaims freedom of speech, press, and religion, focusing on the basic rights of citizens and political associations. It claims that “the people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.” 4 It is one of the essential amendments that provide fundamental rights to every person in the US, thus following democracy and equality. According to the above point, it was prohibited to legislate with regards to religion, assembly, speech, and the press. One may note that the identified amendment became a vital building block of American democracy.

The adoption of the Bill of Rights in terms of the Civil War may be regarded as a great victory for American democracy. At the same time, it is important to claim that this document, likewise the Constitution itself, does not say anything about socio-economic rights and freedoms. Therefore, the brief prescriptions contained in the Bill of Rights have received a detailed interpretation in numerous decisions of the Supreme Court as well as in hundreds of acts of Congress. However, the very process of ratification and the ultimate approval of the Bill was a significant step towards democracy.

This most important part of the Constitution proceeds from the recognition for every person of his or her natural and inalienable rights. One should emphasize that the deprivation of a person’s life, liberty, and the property is possible only through an independent Court, and the protection of rights is the primary duty of the state. 5 The Bill of Rights became a confirmation of the US Basic Law and eliminated any doubts regarding fundamental human rights.

Analyzing the origins and content of the Bill of Rights, it seems essential to pay attention to the specific language and rules used by legislators. In particular, some parts of the document about the prohibition of excessive bail and brutal punishment apparently reflect English roots. This point may be traced back to the declaration issued by the House of Lords in 1316 and then in the English Bill of Rights. 6

At the same time, other amendments such as the acceptance of religious freedom refer to the changes in American society, especially those that occurred after the Revolution. Unlike the English document, the American version is secular as it separates the state and the church. Only after the approval of ten amendments is it possible to consider the Constitution sufficiently complete, and the American Revolution finally consolidated in its political structures as it received a powerful constitutional and legal adjustment and support.

The US Constitution was altered several times, for example, to allow voting from the age of 18 or establish direct elections of senators. On the contrary, the Bill of Rights has not yet been changed. Some of its provisions are controversial today, such as the interpretation of the second amendment on the right to bear arms and the well-organized police, which are constantly under scrutiny. Nevertheless, the Bill of Rights remains the quintessence of the system of individual freedoms, the limitation of executive power, and the rule of law, which Americans call critical to shaping their worldviews. The freedom of expression now becomes a symbol of American democracy, when every person has the constitutional right to speak and be heard by others.

To conclude, it should be emphasized that in its original form, the US Constitution did not consolidate the rights and freedoms of citizens since they were contained in the constitutions of the states. In this regard, the paramount goal of the US Constitution was limited to the creation of a system of public authorities. The introduction of the Bill of Rights can be considered a fundamental step towards democracy and the provision of equal rights to every US citizen.

The first amendment serves as a vital point in determining and ensuring one’s freedom of speech, religion, and the press – the elements that are unalienable to everyone. Even though some of its aspects may seem to be contentious such as the second amendment, the Bill of Rights remains an essential part of the Constitution.

Cogan, Neil H. The Complete Bill of Rights: The drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins . New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty! An American History . 4th ed. New York: WW Norton & Company, 2013.

Fraser, Russell. A Machine that Would Go of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture . New York: Routledge, 2017.

Grant, Carl A., and Melissa Leigh Gibson. ““The Path of Social Justice”: A Human Rights History of Social Justice Education.” Equity & Excellence in Education 46, no. 1 (2013): 81-99.

Klug, Francesca. “A Magna Carta for All Humanity: Homing in on Human Rights.” Soundings 2, no. 60 (2015): 130-144.

Thornhill, Chris. “Natural Law, State Formation and the Foundations of Social Theory.” Journal of Classical Sociology 13, no. 2 (2013): 197-221.

- Francesca Klug, “A Magna Carta for All Humanity: Homing in on Human Rights,” Soundings 2, no. 60 (2015): 135.

- Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty! An American History , 4th ed. (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2013), 258.

- Chris Thornhill, “Natural Law, State Formation and the Foundations of Social Theory,” Journal of Classical Sociology 13, no. 2 (2013): 209.

- Neil H. Cogan, The complete Bill of Rights: The drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 147.

- Carl A. Grant and Melissa Leigh Gibson,”“The Path of Social Justice”: A Human Rights History of Social Justice Education,” Equity & Excellence in Education 46, no. 1 (2013): 82.

- Russell Fraser, A Machine that Would Go of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture (New York: Routledge, 2017), 157.

- Jeffersonian Worldview in American History

- Chapters 1-2 of "US: A Narrative History Volume 1"

- James Madison and the United States Constitution

- Founding Fathers of America

- Prohibition Benefits and Detriments

- Thanksgiving Day and Its History Myth

- The Early 1960s and Civil Rights

- Industrial Development in the USA

- American History, the Civil War and Reconstruction

- The History of the United States Army

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 7). The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-bill-of-rights-its-origins-and-historic-role/

"The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role." IvyPanda , 7 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-bill-of-rights-its-origins-and-historic-role/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-bill-of-rights-its-origins-and-historic-role/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-bill-of-rights-its-origins-and-historic-role/.

IvyPanda . "The Bill of Rights, Its Origins and Historic Role." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-bill-of-rights-its-origins-and-historic-role/.

America's Founding Documents

The Bill of Rights: How Did it Happen?

Writing the bill of rights.

The amendments James Madison proposed were designed to win support in both houses of Congress and the states. He focused on rights-related amendments, ignoring suggestions that would have structurally changed the government.

Opposition to the Constitution

Many Americans, persuaded by a pamphlet written by George Mason, opposed the new government. Mason was one of three delegates present on the final day of the convention who refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a bill of rights.

James Madison and other supporters of the Constitution argued that a bill of rights wasn't necessary because - “the government can only exert the powers specified by the Constitution.” But they agreed to consider adding amendments when ratification was in danger in the key state of Massachusetts.

Introducing the Bill of Rights in the First Congress

Few members of the First Congress wanted to make amending the new Constitution a priority. But James Madison, once the most vocal opponent of the Bill of Rights, introduced a list of amendments to the Constitution on June 8, 1789, and “hounded his colleagues relentlessly” to secure its passage. Madison had come to appreciate the importance voters attached to these protections, the role that enshrining them in the Constitution could have in educating people about their rights, and the chance that adding them might prevent its opponents from making more drastic changes to it.

Ratifying the Bill of Rights

The House passed a joint resolution containing 17 amendments based on Madison’s proposal. The Senate changed the joint resolution to consist of 12 amendments. A joint House and Senate Conference Committee settled remaining disagreements in September. On October 2, 1789, President Washington sent copies of the 12 amendments adopted by Congress to the states. By December 15, 1791, three-fourths of the states had ratified 10 of these, now known as the “Bill of Rights.”

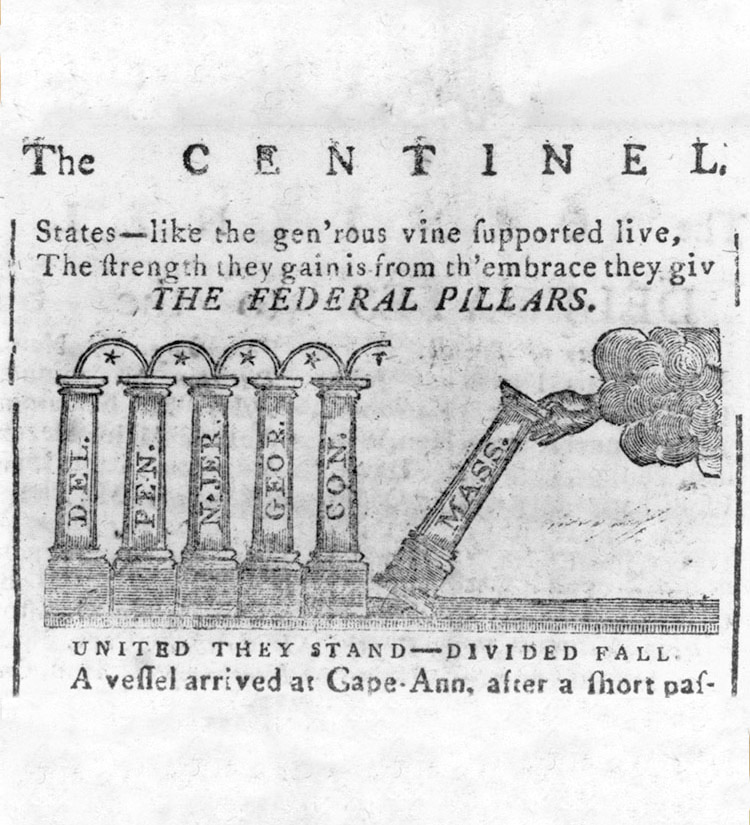

The Federal Pillars, 1789

The Massachusetts Compromise, in which the states agreed to ratify the Constitution provided the First Congress consider the rights and other amendments it proposed, secured ratification and paved the way for the passage of the Bill of Rights. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Federal Hall, Seat of Congress 1790, by Amos Doolittle

Federal Hall, originally New York’s city hall, served as the first capitol building of the United States. The Bill of Rights was introduced there. Courtesy of the Library of CongressCourtesy of the Library of Congress

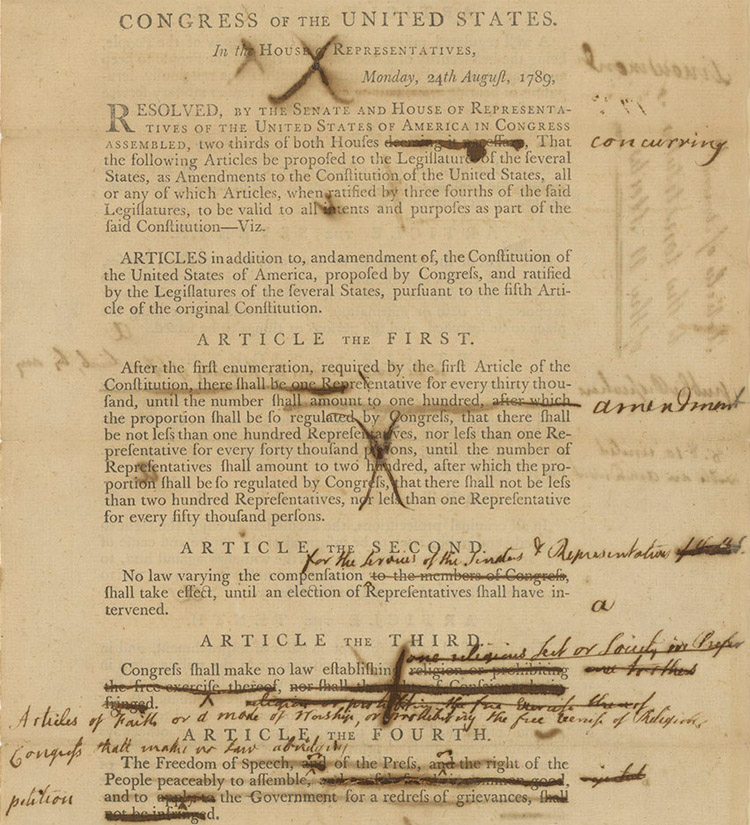

Senate Revisions to House Proposed Amendments, 1789

This is a working copy of the Articles of Amendment to be submitted to the State Legislatures. Of the 12 articles submitted, 10 were ratified by the states. National Archives

What Does it Say? How Was it Made?

- Visit Our Blog about Russia to know more about Russian sights, history

- Check out our Russian cities and regions guides

- Follow us on Twitter and Facebook to better understand Russia

- Info about getting Russian visa , the main airports , how to rent an apartment

- Our Expert answers your questions about Russia, some tips about sending flowers

Russian regions

- Belgorod oblast

- Bryansk oblast

- Ivanovo oblast

- Kaluga oblast

- Kostroma oblast

- Kursk oblast

- Lipetsk oblast

- Moskovskaya oblast

- Orlovskaya oblast

- Ryazan oblast

- Smolensk oblast

- Tambov oblast

- Tula oblast

- Tver oblast

- Vladimir oblast

- Voronezh oblast

- Yaroslavl oblast

- Map of Russia

- All cities and regions

- Blog about Russia

- News from Russia

- How to get a visa

- Flights to Russia

- Russian hotels

- Renting apartments

- Russian currency

- FIFA World Cup 2018

- Submit an article

- Flowers to Russia

- Ask our Expert

Voronezh Oblast, Russia

The capital city of Voronezh oblast: Voronezh .

Voronezh Oblast - Overview

Voronezh Oblast is a federal subject of Russia, part of the Central Federal District. Voronezh is the capital city of the region.

The population of Voronezh Oblast is about 2,288,000 (2022), the area - 52,216 sq. km.

Voronezh oblast flag

Voronezh oblast coat of arms.

Voronezh oblast map, Russia

Voronezh oblast latest news and posts from our blog:.

9 September, 2015 / Kalacheevskaya Cave - the longest cave in Voronezh region .

10 May, 2010 / Voronezh oblast palace of the princess photos .

History of Voronezh Oblast

The first people began to settle in the territory of the present Voronezh region in the Paleolithic age, about 30 thousand years ago. In the Iron Age, this region became part of Scythia. Then the Sarmatians came to replace the Scythians. It is assumed that they gave the name to the Don River.

In the early Middle Ages, the Alans, the descendants of the Sarmatians, moved on to a settled way of life, mastered the skills of urban culture and entered into a complex symbiosis with nomads (the Bulgars and the Khazars). In the 7th century, the steppe part of the region became the territory of the Khazar Kaganate.

In the 9th-10th centuries, the Slavs began to settle in the north of the region. Central and southern areas were controlled by nomadic tribes. In the first half of the 13th century, during the Mongol invasion, the ancient Russian settlements were destroyed, and Voronezh land for several centuries turned into a so-called “wild field” crossed by the main Tatar roads - Nogai and Kalmius roads.

In the 15th century, several districts up to the Khopyor River, the Vorona River and the mouth of the Voronezh River were part of the Ryazan principality, but the Russian settlements here were few in number. Between the Russian territory and the Tatar nomads lay a vast, devastated by nomadic raids, neutral buffer land.

More historical facts…

In 1521, the Ryazan principality became part of the Moscow state, which opened the way for the beginning of the Russian colonization of these territories. The Cossacks began to form from the Christian population of the region that assimilated certain elements of the culture of nomads.

In 1585, in place of the Cossack village, Voronezh was founded as a fortress of the Moscow state on the border of the Wild Field. For more than 50 years Voronezh was the only town on the territory of the present Voronezh region. Up to the 17th century, the Tatar raids on the Voronezh land continued.

In 1696, by decision and with the personal participation of Peter I, a shipyard was built on Voronezh land for the construction of the first Russian fleet - the foothold for the development of the Black Sea region. From here the Azov campaigns of Peter I began. The centers of Russian colonization in the east of the region were the towns of Borisoglebsk (1698) and Novokhopersk (1716).

In 1711, (after the loss of Azov), Voronezh became a provincial town, the administrative center of the Azov gubernia (province). In the 18th century, the development of the entire territory of the region began. In 1725, the province received the name of Voronezh.

Voronezh Governorate became one of the main bread baskets of the Russian Empire. In the 1860-1870s, railways passed through the territory of the region and connected Central Russia with South Ukraine, the North Caucasus and the Trans-Volga. The region’s economy remained largely agrarian.

In 1934, Voronezh Oblast was established. In 1937, Tambov Oblast was singled out of the Voronezh region. During the Second World War, it became the scene of fierce battles. The city of Voronezh was almost completely destroyed. In 1954, large western and northern territories were transferred to Belgorod and Lipetsk oblasts. In 1957, the boundaries of Voronezh Oblast took the current form.

In the mid-1960s, the Novovoronezh nuclear power plant was built, the Stavropol-Moscow gas pipeline passed through the territory of the region. Voronezh became a major center of the country’s military-industrial complex. In 1972, the Voronezh reservoir was created.

Nature of Voronezh Oblast

Birches in the middle of the field in the Voronezh region

Author: Stepygin Evgeny

Golden autumn in Voronezh Oblast

Author: Constantin Silkin

Cows in the Voronezh region

Author: Galina Linn

Voronezh Oblast - Features

Voronezh Oblast is located in the south-west of the European part of Russia. The length of the region from north to south is 277.5 km, from west to east - 352 km. In the south it borders on the Lugansk region of Ukraine.

The climate is moderately continental. The average temperature in January is minus 10 degrees Celsius, in July - plus 20 degrees Celsius.

The largest cities and towns of Voronezh Oblast are Voronezh (1,048,700), Rossosh (61,800), Borisoglebsk (57,200), Liski (52,000).

The most important resource of Voronezh Oblast is its fertile black soil rich in humus (chernozem), which occupy most of the territory. The largest rivers are the Don, Voronezh, Khopyor, Bityug.

Voronezh Oblast has rich deposits of non-metallic raw materials, mainly building materials (sands, clays, chalk, granites, cement raw materials, ocher, limestone, sandstone). Also there are deposits of phosphorites, nickel, copper, and platinum.

The local economy is an industrial-agrarian one. The main industries are mechanical engineering, electric power industry, chemical industry, and processing of agricultural products. This region is a major supplier of agricultural products: wheat, sugar beet, sunflower, potatoes, and vegetables. There is a nuclear power plant on the territory of Voronezh oblast - Novovoronezh Nuclear Power Plant.

Two federal highways pass through the territory of the Voronezh region: E 115 - M4 “Moscow-Novorossiysk” and E 119 - M6 “Moscow-Astrakhan”.

Attractions of Voronezh Oblast

Voronezh Oblast has a significant recreational and tourist potential. There are 7 historical towns in the region (Bobrov, Boguchar, Borisoglebsk, Voronezh, Novokhopersk, Ostrogozhsk, Pavlovsk), about 2,700 historical and cultural monuments, 20 museums and 3 reserves.

Pine forests and oak groves in the valley of the Voronezh River are known for their favorable effect on human health. There are a lot of summer and winter tourist bases and sanatoriums.

The main sights of the Voronezh region:

- Natural Architectural-Archaeological Museum-Reserve Divnogorye in Liskinsky district - one of the most popular and recognizable sights of the Voronezh region. One of the main attractions is a church built by monks inside a chalk cliff;

- Archeological Museum-Reserve “Kostyonki” in the village of Kostyonki in the Khokholsky district;

- Museum-Estate of D. V. Venevitinov in the village of Novozhivotinoye in Ramonsky district - a complex of residential and park buildings that belonged to the old Russian noble family in the second half of the 17th - early 20th centuries;

- Castle of the Princess of Oldenburg in Ramon - a picturesque manor house built in the style of brick neo-Gothic in the late 19th century;

- Voronezh Biosphere Reserve with the world’s only experimental beaver cattery;

- “Village of the 17th-19th centuries” - a museum in the open air in the town of Ertil;

- Khrenovskaya and Chesma stud farms;

- Museums and memorial places in Voronezh.

Voronezh oblast of Russia photos

Churches in the voronezh region.

Country life in Voronezh Oblast

Church in the Voronezh region

Author: Lantsov Dmitriy

Orthodox cathedral in Voronezh Oblast

Author: Feliks Radev

Voronezh Oblast scenery

Lonely locomotive in the Voronezh region

Author: Gribanov D.

- Currently 2.92/5

Rating: 2.9 /5 (245 votes cast)

Essay: Native Americans

Native Americans have experienced discrimination at the hands of European settlers during the colonial era and the white majority in the United States for over four hundred years. In that time, there have been a wide variety of policies towards Native Americans, some with good intentions and some bad, but none seemed to resolve the clash of cultures and the difficulties faced by Native Americans. They have rarely enjoyed liberty and equality in the American system of self-government.

The first encounters of European colonists and Native Americans in North America set the patterns for the relationship for nearly two centuries. First, and most devastatingly, Europeans unwittingly brought many diseases for which Natives had no immunity, and hundreds of thousands died. Second, Native Americans sometimes benefitted from trading furs and other goods to Europeans, but the trade often altered traditional commercial routes or Native ways of life. Third, colonists and Natives engaged in a series of massacres and wars throughout the Eastern Seaboard that resulted in brutality and a large number of deaths on each side. Native American scalping of enemy combatants and civilians in the wars caused the Europeans to think them uncivilized savages. King Philip’s War, fought in New England in 1675-1676, remains the bloodiest war in American history in casualty rates. The British and Americans supposedly used germ warfare against Native Americans, but there was in fact only one unproven claim of the British army spreading smallpox through blankets. Finally, the European population grew rapidly, and colonists expanded onto Native lands through war, broken treaties, and land grabs.

Before, during, and after the American Revolution, there were a number of wars fought on the Ohio Valley and Mid-West. Native Americans on the frontier had generally sided with the French during the French and Indian War and on the side of the British during the American Revolution. Native Americans found that they lost large amounts of land after the American Revolution and did not have a say in the peace treaty. Some of the Founding Fathers expressed the hope that Natives would be integrated into American society by adopting private property and agriculture, white styles of dress, and education and written languages. They believed that this was a benevolent, humane, and enlightened policy, and that, if accomplished, the two peoples could live in relative peace. Nevertheless, after the American Revolution, white Americans continued to flood the frontier for agricultural land. This was spurred on by the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803. Americans believed that they had a “Manifest Destiny” or divine mission to expand westward and conquer the entire continent. Native Americans would either be paid for their land or compelled to give it up by force. Either way, keeping all of their lands did not seem to be an option for white settlers.

Native Americans on the frontier had generally sided with the French during the French and Indian War and on the side of the British during the American Revolution. Native Americans found that they lost large amounts of land after the American Revolution and did not have a say in the peace treaty.

Manifest Destiny found support in federal law when Congress passed the Indian Removal Act (1830) that allowed the national government to relocate Natives beyond the Mississippi River.

Even though the Cherokee people adopted white ways, Georgia supported those whites who sought to take Native lands. In the Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) decision, Native Americans sued to protect their property rights from encroachment by the state of Georgia on behalf of land-hungry white settlers. In the decision, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall broke with the custom of treating Natives as independent nations that theoretically protected the sanctity of land treaties and declared that the tribes were “domestic dependent nations” rather than an independent nation with sovereign treaty rights. In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), another case dealing with the relationship of Cherokee and the Georgia state government, Marshall reversed his earlier decision and declared that Native tribes were foreign nations who were immune to state laws. However, President Andrew Jackson used his executive power and sided with the white Georgians. In a famous statement of the exercise of executive power President Jackson retorted when he heard of the decision: “John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce it.”

In 1838, despite the legal victory, more than 16,000 Cherokees were forcibly removed to the Oklahoma Territory and an estimated 4,000 died tragically in this “Trail of Tears.” It followed the removal of several other tribes from the Southeast including tens of thousands of Choctaw, Seminoles, Creek, and Chickasaw throughout the 1830s.

In 1838, despite the legal victory, more than 16,000 Cherokees were forcibly removed to the Oklahoma Territory and an estimated 4,000 died tragically in this “Trail of Tears.”

In 1851, the Indian Appropriations Act initiated the policy of establishing reservations, or land parcels set aside for Native tribes, as an attempt to balance the demand of Western settlers for land and to protect lands for Natives. The land however was often poor, away from ancestral homes, and forced Natives to adopt white agriculture. Moreover, individual Americans demanded Native lands and chiseled away at the size of reservations. In addition, the reservations worsened the lot of Native Americans, but Americans continued in their advance to settle the continent.

After the Civil War, the brutal wars between the Native Americans and federal troops continued with casualties on both sides. In 1876, General George Custer and the Seventh Cavalry attacked Chief of the Hunkpapa Lakota tribe, Sitting Bull, who led an alliance of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors at Little Bighorn. Custer recklessly attacked the Natives led by Crazy Horse, war leader of Oglala Lakota tribe, who killed Custer and all his 250 soldiers. In late 1890, at the Wounded Knee massacre, the U.S. Seventh Cavalry took revenge by slaughtering 150 Sioux men, women, and children after the warriors refused to surrender their arms.

During the mid-to-late nineteenth century, America industrialized as migrants continued to settle the West, using the Transcontinental Railroad and marking off private properties with barbed wire. Thus was it clear that the settlers were moving rapidly westward, establishing farms, and depleting massive herds of buffalo that the Natives depended upon for food. Reformers were outraged by the mistreatment of Native Americans as chronicled in Helen Hunt Jackson’s A Century of Dishonor (1881). Reformers sought to implement integration into American society with the Dawes Act (1887), which imposed a system of individual ownership of land and allotted parcels of land to Natives while selling off “surplus” land to white Americans. However, the Act both failed to protect Native lands or integrate them into American culture.

In 1934, the New Deal reinforced the idea that the federal government would care for dependent Native Americans with the Indian Reorganization Act.

The new law ended the policy of allotting land to individual Native Americans and supported tribal sovereignty over the lands. The federal government moreover provided funds for health care, social welfare, and education on the reservations. Although reservations had been embraced by reformers, they soon fell out of favor as a symbol of white control. The federal government also seemed to fail just as much as the reservations in ameliorating the conditions of Native Americans which continued to worsen compared to an affluent postwar America.

After World War II, the conditions on reservations were shown to be well below that of middle-class America. Poverty, unemployment, crime, and malnutrition were endemic on reservations. Rates for suicide, alcohol and drug abuse, depression, and infant mortality were startlingly high. Reformers sought a remedy by removing Natives from oppressive reservations and their historical stigma into mainstream America in what was called “Indian termination” policy. Whereas critics complained that Natives were forced into reservations, they now fought against being forced to assimilate. It seemed that both segregation and integration were abject failures and the elusive search for a successful policy respecting the liberty and equality of Natives would not be found.

After World War II, the conditions on reservations were shown to be well below that of middle-class America. Poverty, unemployment, crime, and malnutrition were endemic on reservations.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of a movement in pursuit of Native American rights just as other groups engaged in similar reform movements. In several incidents occupying historic monuments, activists on the left sought to publicize the plight of Native Americans.

In late 1969, hundreds of Natives and their white supporters occupied Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay to expose the historical discrimination and “genocide” suffered by Natives and to demand a center there for the study of Native American history and culture. The last occupiers did not leave Alcatraz until 1971. Politically radical Native Americans joined the American Indian Movement (AIM), and hundreds took over Wounded Knee in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota in February, 1973. The members of AIM occupied the town for 71 days, and there were several exchanges of gunfire with federal law enforcement officials. For Native activists, it seemed more evidence of oppression by the federal government, but the charges were dropped against the leaders. The reservation suffered a crime rate nearly ten times that of Detroit after the federal officials departed, and the lofty aims of the activists were not achieved.

The violent protest by radicals soon gave way to the multicultural and diversity trends in education during the 1980s and beyond. The term “American Indian” fell into disfavor as a symbol of European oppression and “Native Americans” became the accepted term. Activists called depictions of Native Americans as sports mascots racist and applied pressure to use more innocuous symbols. For example, Stanford University changed their mascot from Indians to Cardinals, and Dartmouth University from Indians to Big Green. Many historians began to portray the European settlement of America as an “invasion” or “genocide.” After Indian reservations gained the right to open gaming casinos, tribes began to earn large sums, and some non-Natives claimed Indian ancestry to take advantage of the windfall of revenue. Similar questions of who was a Native American were applicable to college applications and federal contracts, both of which employed affirmative action programs.

Native Americans have rarely enjoyed the benefits of liberty and equality under the American republic. They have had a status throughout the centuries that has alternated between separation and assimilation. Federal policies related to Native Americans have changed many times over the last two hundred years, but none have seemed to improve their freedom or equality in American society. Unlike women or African Americans, who have won greater liberty and equality in recent decades to fulfill American ideals, Native Americans can point to few examples of progress. Over the past century, federal policies that have attempted both separation and integration have failed because they have been unable to resolve the tension of preserving the unique autonomy of Native Americans while at the same time integrating them into the American character.

Related Content

Native Americans

Native Americans have experienced discrimination at the hands of European settlers during the colonial era and the white majority in the United States for over four hundred years. In that time, there have been a wide variety of policies towards Native Americans, some with good intentions and some bad, but none seemed to resolve the clash of cultures and the difficulties faced by Native Americans. They have rarely enjoyed liberty and equality in the American system of self-government.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

A thesis statement: Tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter. Is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper. Remember: A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be ...

The Bill of Rights Institute teaches civics. We equip students and teachers to live the ideals of a free and just society. Board and Staff; BRI Blog; ... Tips for Thesis Statements and Essays; 1310 North Courthouse Rd. #620 Arlington, VA 22201. [email protected] (703) 894-1776 ©2024. Bill of Rights ...

The Bill of Rights as a Constitution Akhil Reed Amart To many Americans, the Bill of Rights stands as the centerpiece of our constitutional order-and yet constitutional scholars lack an adequate account of it. Instead of being studied holistically, the Bill has been chopped up into discrete chunks of text, with each bit examined in isolation.

Concluding Paragraph for the Bill of Rights 1. Revisit/Reword the thesis statement: The conclusion of any paper is to revisit/reword the thesis statement. For the Bill of Rights essay, the following basic example sentence would be acceptable: There can be no denying the vital importance of the First, Second and Ninth Amendments.

On June 8, 1789, Madison delivered a speech in favor of a bill of rights. He wanted to achieve a united political order with harmony and justice. A bill of rights would promote the civic virtues of friendship and moderation, or self-control, because the Anti-Federalists would support the new government.

Analysis of «Bill of Rights» Definition Essay. In the United States, the Bill of Rights refers to the first ten constitutional amendments. The constitution was amended to safeguard the natural rights of liberty and material goods. Through the bill of rights, an individual is assured of a number of personal freedoms, including the right to own ...

Bill of Rights Essay. As you know, the first ten amendments to the Constitution are known as the Bill of Rights. Even though the Bill of Rights was written over two hundred years ago, these amendments continue to have a direct impact on our daily lives. These ten amendments guarantee many of our rights as citizens of the United States ...

This writing practice should be completed at the end of Chapter 1, although it can be adapted for other units if students continue to demonstrate a need for practice in constructing thesis statements. Students will be able to construct thesis statements that will earn a full point on the Document-Based Question (DBQ) and Long Essay Question ...

Bill of Rights. First Amendment [Religion, Speech, Press, Assembly, Petition (1791)] (see explanation) Second Amendment [Right to Bear Arms (1791)] (see explanation) Third Amendment [Quartering of Troops (1791)] (see explanation) Fourth Amendment [Search and Seizure (1791)] (see explanation) Fifth Amendment [Grand Jury, Double Jeopardy, Self ...