- Life at Reid Avenue

- Clubs & Societies

Commemoration of Our National Heroes.

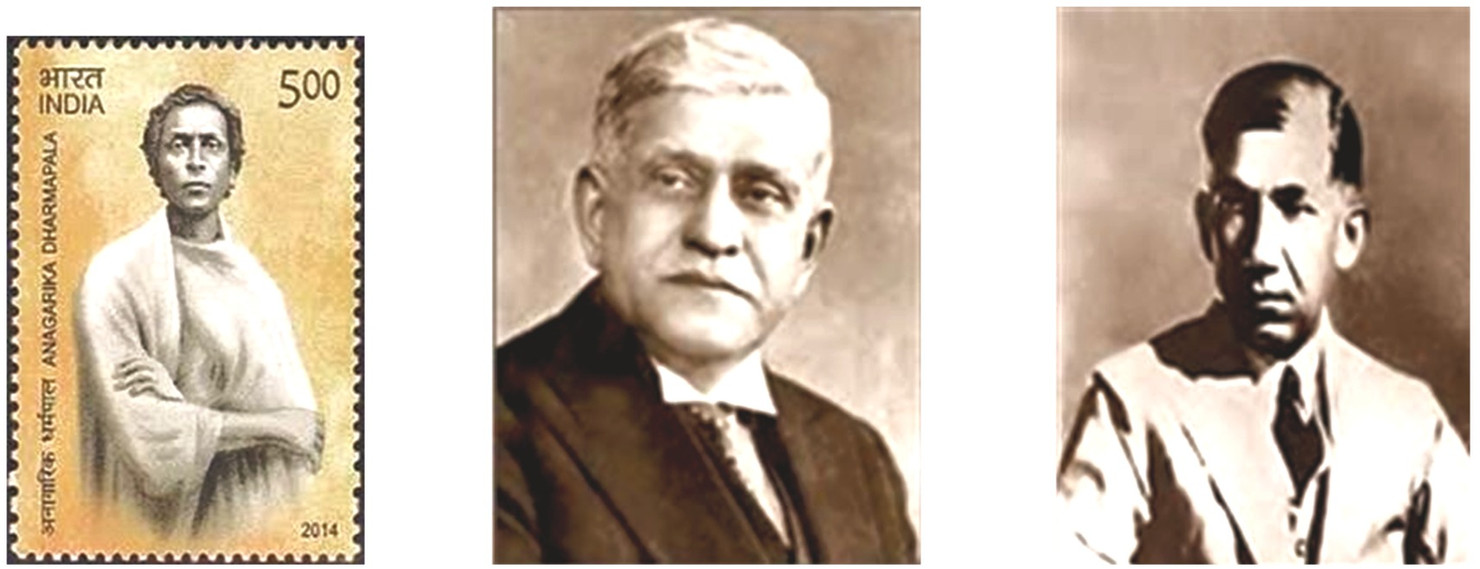

Sri Lanka was a country which was ruled by different European nations from 1505. British administration was the final European nation which ruled Sri Lanka before its independence. In 1948, ending the colonial era which lasted over 400 years, there was a switch of powers. Though there were battles in the initial stages of getting freedom from the Europeans finally there was a peaceful transfer of power from the British administration to Ceylon representatives. There were number of people who involved directly as indirectly with this independence movement. Veera Puran Appu, Kepppatipola Adikaram, Gongalegoda Banda, Kudhapola Hamuduruwo, S. Mahinda Thero were the pioneers of this movement at the initial phases. They kindled the flame of the battle to free mother Sri Lanka from the British empire. This battle was continued with the support of patriots like Anagarika Dharmapala, Walisingha Harshichandra, Sir D.B.Jayathilaka , F.R.Senanayake, D.R. Wijewardena , D.S. Senanyake etc. This movement of freedom was not only supported by the Sinhalese nationality but flag wavers of other nationality such as Ponnambalam Arunachalam, Ponnambalam Ramanadhan,Siddhi Lebbe also gave an immense backing to this.

With all these contribution mother Sri Lanka was freed from British Empire on 1948 February 04th. In the initial phase it was a semi – independent ‘dominion status’and on 22 May, 1972 Sri Lanka became full republic. This independent status of the country helped to save its cultural heritage and natural resources for its future children.They were the pillars of independent Sri Lanka and hence it is the utmost duty of all the Sri Lankans to pay their gratitude for the national heroes who dedicated their lives to make ‘Pearl of the Indian Ocean’ a free country.

- Philately vs Stamp Collecting

- Stamp issue: Deshabandu Ayur. Dr. Victor Hettigoda (LittD)

- 12th Sept -Workshop by Ethugalpura Philatelic Society

- Stamps with Keshan – Video 03

- විශේෂ මුද්දර නිර්මාණ චිත්ර තරගය

- Keshan Hareshu launches new stamp video channel

- ගුවන් ලිපි (Aerogrammes)

- Youtube Channel

Philately.lk

Home for all Ceylon & Sri Lanka stamp knowledge portal

Bulletin 262 – 25.05.1989 – National Heroes

Stamp Bulletin No. 262 NATIONAL HEROES 1989-05-22 Department of Posts, Lotus Road, Colombo 01, Sri Lanka. The Philatelic Bureau of the Department of Posts will issue on 22nd May, 1989 five commemorative stamps in the denomination of .75 cents to honour the following National Heroes: (a) Ven. Parawahera Vajiragnana Nayaka Maha Thero The Most Venerable Dr. Parawahera Vajiragnana Nayaka Maha Thero who was born in an autocratic Sinhala Buddhist Family on 26.09.1893, in Parawahera, Matara and received his first initiation as a Samanera in Purana Vihara, Meegahagoda, Pelmadulla, Ratnapura in 1909. He obtained his Upasampada ordination from Malwatte Chapter, Kandy in 1913, and was educated in the Vidyodaya Maha Pirivena, Maligakanda, Colombo, wherein he was appointed as an assistant lecturer from 1921 to 1928 in the same College. He also as a Dhammachariva served in the Ananda Maha Vidyalaya and Nalanda Maha Vidyalaya during the same period. In 1928 as the leader of the first Buddhist Mission to Europe and America, was sent by the Maha Bodhi Society of Sri Lanka. He went to the western countries and did his sefless mission very successfully for eight years. He was the first Buddhist monk to receive Ph.D. degree from a western university like Cambridge University by writing a very authentic and monumental Thesis called “Buddhist Meditation in Theory and Practice” in 1936. Holding the Presidentship of the Ceylon Maha Bodhi Society for 23 years Dr. P. Vajiragnana Nayaka Thero opened a golden chapter to its history by erecting two Aggasavaka Maha Vihara in Sanchi, Bhopal State, India and at Maha Bodhi Society, Maligakanda, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Being appointed as the Chief Inspector of Pirivenas he raised up the Buddhist education to a higher standard of its functioning. During 2500th Buddha Jayanthi Celebration as the Editor and Secretary in Chief to the Tripitake Translation and Revising Board Dr. Vajiragnana Neyaka Maha Thero rendered a monumental service to the course of Buddhasasana. In 1959 he became the Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, in the Vidyodaya University of Sri Lanka and gradually was appointed as the Vice Chancellor and the Vice Chancellor Emeritus till he peacefully passed away in 1970. (b) Fr. Maurice J. Le Goc Fr. Maurice Jacques Le Goc was one of the greatest educationists among the Christian Missionaries in Sri Lanka. He was born on 21st February, 1881 in Brittany, France and joined the Oblate Congregation in 1903. He was Ordained priest in Rome in 1907. He studied there obtaining the Ph.D. and Licentiate degrees in Theology at the Gregorian University, Rome. The first Rector of St. Joseph’s College, Colombo, Fr. C. Collin, chose him for training in the United Kingdom for teaching in Sri Lanka. He secured the B.A. at Cambridge (1911) and the Bs.C. in London with a first class and M.A. in 1914. He arrived in Colombo on 3rd January, 1914 and was appointed to St. Joseph’s College in the same year. He became Rector of St. Joseph’s in 1919 and served in that capacity for 21 years. He retired from school work in 1941 and then worked for the church as Vicar General, Colombo Archdiocese. He was lecturer in Botany at the Ceylon Medical College and in Nature study at the Government Training College. His publications include “Introduction to Tropical Botany”, “Simplified Astronomy” and “Dignity of Labour”. From St. Joseph’s, he founded three other schools in the suburbs of Colombo, St. John’s Dematagoda, St. Peter’s College, Bambalapitiya and St. Paul’s, Waragoda, Kelaniya. He died of a car accident during the war in March, 1945. A man of rare distinction, he endeared himself to all his students and had an impact on the educational scene beyond the confines of his own college. A whole generation of students passed through his hands. The nation as a whole has good reason to be thankful for his life and service. (c) Hemapala Munidasa Hemapala Munidasa was an unimitable writer who weilded his powerful pen for 35 years (1922-1957) for the enrichment of the Sinhala language and Literature. Born on 22.06.1903 in the village of Ambagasdowa in Welimada, his preliminary education was only upto the 6th standard. But reading every book and paper that reached his hand he felt an unquenchable thirst of knowledge and literal taste. He came down to the capital to get a practical education to be a weaving instructor. Though he succeeded in this attempt, his yearning towards writing and literary taste made him to write and publish his first novel ” Viola “when he was 19 years of age. His real literary life began when he joined the Editorial Staff of “Swadesa Mitraya”, the then most popular weekly in 1922. There he formed a lucid and vivid style of Sinhala writing and earned a reputation through his special articles, “Legal Court Scenes” and “Life Sketche of Heroes”. Later he joined the ” Sinhala Bauddhaya” as its co-editor and in 1934 became its Editor-in-Chief, which paper he served with abundance of writing on various topics. The young sinhala poets rallied round him due to the artistic matter and style of this able writer whose patriotic writing generated a new enthusiasm among them in addition to a religious ferver. Later he started” Sinhala Balaya” as the organ of the Sinhala Maha Sabha and later “The Sinhale” in 1951. While editing the above mentioned weeklies, he wrote a number of novels, short stories and classical translations. Malawun Atara Jeevitaya, Sekaya, Sakala sena, Punaralokaya, Kinnara Pissuwa, Nari Getaya, Wahal Wendesiya, Rasawadanaya, Ratu Keta, Yaka Bas, Jeevita Poojava were some of them. Pancha Thantra translation was acclaimed as a classic. Combining the essence of Maha-Bharata and Bhagavat Geetha he wrote his largest work entitled “Bharatha Geethaya” in his last days. He passed away on 29th December 1957 when he was only 54 years of age. (d) Ananda Samarakoon Mr. Ananda Samarakoon, the composer of the national anthem of Sri Lanka was born in the village of Liyanwala, Padukka in the Colombo District on the 13th of January, 1911. He was educated at the Wewala Government School, Piliyandala and the Christian School, Kotte and was later appointed as the Arts and Music teacher of the same Christian School. Mr. Samarakoon who was highly impressed by the performances of Ravindranath Tagore when the latter visited Sri Lanka in 1934 with a group of forty dancers left for India in 1936 in quest of the Tagore arts tradition. There, he joined the Tagore’s Shanthinikethan and studied arts and music from teachers like Nandalal Bose and Shanthilal Ghose. Mr. Ananda Samarakoon, on his return to the Island, became extremely popular among the people by the songs he sang for Gramaphone Records. “Endada Menike Mamath Diyambata Nelanna Kekatiya Mal”, “Podimal Ethana”, “Wile Malak Pipila Kadimayi”, “Punchi Suda Sudu Ketiya”, “Ese Madura Jeevanaye Geetha”, “Besa Seethala Gangule, Peena Peena Namuko Nago”, “Ramya Wana Male” and “Pudamu Me Kusum” are some of his songs which became very popular. In fact, the song that is presently being used as our national anthem was also a popular gramaphone record. In April 1950, the then Minister of Finance Hon. J. R. Jayewardene in a memorandum to the Cabinet proposed that the song “Namo Namo Matha” which had become very popular among the people be adopted as the national anthem. Accordingly, the Cabinet decided on 22.11.1951 that the song ” Namo Namo Matha” should be our national anthem. It is not only his composition of the national anthem that carned him such widespread popularity. At a time when our musicians and singers were composing Sinhala songs by copying the tunes of Hindi and Tamil songs, it was Mr. Samarakoon who started composing songs independent of the tunes of other languages and became very popular. Further, Mr. Samarakoon was the first person who took pains to trace the national identities of music and who significantly improved the standard of composition of Sinhala songs utilising his wide knowledge of folk literature. Mr. Ananda Samarakoon has conducted arts exhibitions in the cities of Bombay, Singapore, Kualar Lumpur, Keang, Penang, Bangalore, Lucknow and New Delhi and most of these exhibitions won the admiration of foreign experts and enthusiasts of art. (e) Simon Casie Chitty Simon Casie Chitty was born at Kalpitiya in the Puttalam District on 21.03.1807 and commenced his education in the Tamil School there and later in Puttalam. Without any formal educational facilities, besides his mother tongue Tamil, he acquired a mastery of Sinhala, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Arabic and English and proficiency in four European languages, Portuguese, Dutch, Latin and Greek. His father Gabriel Casic Chitty was the Tamil Translator to Government and was later appointed Mudliar of Calpentyn, a post to which his son succeeded him to on his death in 1833. While holding this post he was allowed to practise as a Proctor of the District Court of Puttlam. His study perserverance and unremitting application enabled him to surmount many obstacies and lay the foundation of his Scholastic and literary career. He made his debut as an author with 3 essays. Sir Alexander Johnston later Chief Justice of Ceylon, President of the Royal Asiatic Society of London proposed him as a corresponding member of the Society. In 1832 he published his magnum opus. The Ceylon Gazetteer, the first attempt of its kind and a mine of information on the topography of Ceylon. This book was highly commended by many eminent contemporary scholars. In 1850 he printed and published the Tamil Plutarach. A full list of his literary undertaking by D.P.E. Hettiaratchi is published in Vol.30 No.80 of the Journal of the R.A.S. (Ceylon) Branch in 1927. In 1838 he was appointed to the Legislative Council in succession to Coomarasamy Mudliar, deceased. He established and maintained at his own expense a Tamil School at Calpentyn for about 50 students to be taught free of charge. He put out a Tamil Newspaper called “Udaya ditya” or “The Rising Sun” which enjoyed an extensive circulation. In 1845 Mr. Casie Chitty resigned his seat in the Legislative Council. He accepted the Police Magistracy of Calpentyn. Shortly afterwards his appointment to the Civil Service was confirmed making him the first native appointed to the Service. In 1847 he was appointed Acting District Judge, Chilaw and confirmed as District Judge in 1847. Despite his heavy Court duties he continued his unremitting literary output. He succumbed to a virulent attack of endemic fever and passed away peacefully on 5.11.1860 at Calpentyn. Simon Casie Chitty’s literary achievements and the Social impact he made will continue to inspire all these who want to work for the improvement of society in modern Sri Lanka. He was an ornament of public life, one who thought and lived as a true Sri Lankan.

Philatelic Details

| Date of issue | 1989.05.22 |

| Denomination | .75 cents |

| Designer | S. S. Silva |

| Stamp size | 29.85mm ‹ 40.64mm |

| Printing process | Offset Lithography |

| Sheet Composition | 50 stamps per sheet |

| Perforations | 13 |

| Printer | Security Printers, Malaysia |

| Colours used | Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black |

| Paper | 102 gsm stamp security paper |

| Gum | Tropical gum |

| Quantity printed | 1,000,000 |

| Catalogue Codes | Stanley Gibbons LK 1064 Michel LK 863 Stamp Number LK 913 Yvert et Tellier LK 871 |

Related Posts

Bulletin 651- 31-10-2007- Udawalawe National Park

Department of Posts,Postal Headquarters,D. R. Wijewardane Mawatha,Colombo 01000 The Philatelic Bureau of the Department of…

Bulletin 119 – 1982.05.22 – Dr. C. W. W. Kannangara

Stamp Bulletin No. 119 Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications, Lotus Road, Colombo 1, Sri Lanka.…

Ceylon Stamp News Vol. 2 No.6 – March 1968

Oriental Stamp Service, more popularly known today as O.S.S used to issue a magazine/bulletin called…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

National Heroes of Sri Lanka

- Ceylonese proctors · 41T

- Buddhist social scientists · 13T

- Chief Government Whips (Sri Lanka) · 14T

- Buddhist and Christian interfaith dialogue · 11T

- Sinhalese monks · 24T

- Buildings and structures in Panadura · 2T

- Kandyan period · 7T

- Sri Lankan independence movement · 15T

- Sri Lankan military leaders · 4T

- Anagārikas · 5T

- Buddhist apologists · 11T

- Buddhist revivalists · 10T

- Sri Lankan Theravada Buddhists · 47T

- Sri Lankan religious leaders · 4T

- British Ceylon period · 14T

- People executed by the United Kingdom by firing squad · 6T

- Faculty of Ananda College · 9T

- Writers from Sikkim · 5T

- 20th-century Indian non-fiction writers · 231T

- Sinhalese military personnel · 101T

- Ceylonese military personnel of World War I · 8T

- Browse Lists by

- Film Decade

- A-Z of Sri Lankan English

- Banyan News Reporters

- Longing and Belonging

- LLRC Archive

- End of war | 5 years on

- 30 Years Ago

- Mediated | Art

- Moving Images

- Remember the Riots

- Site Guidelines

Kumar Sangakkara: The greatest hero of our time

on 08/24/2015 08/23/2015

The Cricketing world will pause for a moment, to celebrate the legendary career of Kumar Sangakkara that draws to a close, and then move on; a bit richer for the legacy he leaves behind, for the standards he raised, expectations he upheld and for his story being entwined with the story of Cricket. He has already confirmed his place among the greatest test batsmen the game has ever seen.

Yet the people of Sri Lanka will pause for longer and with heavier hearts; not merely beset by doubts about who now will rescue their hopes the next time their openers get dismissed in quick succession. To most Sri Lankans, he is more than the greatest Cricketer their country has ever produced. By far the most loved and respected Sri Lankan on his generation in Sri Lanka and throughout the Cricket playing world, for Sri Lankans, he is also their Hero.

Our choice of heroes – as individuals and as nations – reflect more deeply and authentically, our history and character as well as our hopes and aspirations. Every civilization, culture and historical epoch is characterised by the heroes they spawn, whose lives personify the values and aspirations of their time and whose tales become the template by which heroes of subsequent generations will be cast, and judged by.

The first popular hero of the Sinhalese was a king named Gamini from Sri Lanka’s Deep South, whose mythology is constructed around his vanquish of a popular Tamil king from South India who ruled over the Northern half of the island. Gamini was a rebel from his younger days, raging against his father’s inhibition to evict Ellalan: a Cholan invader who occupied richly irrigated Northern plains – the rice bowl of Sri Lanka. It earned him the nickname ‘Dutugamunu’, meaning ‘Gamini the Wicked’.

When Gamini eventually waged his successful military campaign against Ellalan, he did so with the army that his father had built, having marched along the East Coast through Tamil villages where his father had nurtured friendships in order to supply his troops. Gamini’s army is said to have been led by ten ‘giant’ generals with superhuman powers that his father had recruited and around whom he had organised his troops. The impassioned king and his ten giants led a heroic campaign against many odds to unify the island politically – in 205 BC – for the first time in the islands recorded history. Despite the connotations of this event, Tamils and Sinhalese continued to live rather peacefully together for centuries to come.

Yet, for two millennia, as Sri Lanka came under constant attack and threat of invasion, the quintessential Sri Lankan hero conformed to a version of Gamini’s prototype – usually a tragic-heroic king or royal princeling who defended his race from foreign invaders and protected of his faith from heresies. Every generation and historical epoch that followed was characterised by the nationalism and fervour of heroes they spawned; whose lives reflected the fears and aspirations of their time and whose tales become the progenitor of heroes that came after. The stereotypical Sri Lankan hero therefore, was invariably a brave nationalist. From Dutugamunu in the third century BC, to Veera Puran Appu in the nineteenth century, this type of heroism crystallized in the national psyche to the exclusion of all others. The notion of a stable, independent and unified Sri Lanka did not materialise for another two thousand years, and the intermittence of political and geographic unity never allowed a coherent and inclusive national identity to emerge, let alone the unity of hearts and minds of the diversity of people that inhabited the island and came from afar to trade and settle.

Like Gamini, for much of the island’s long, rich and conflicted history, its heroes have been cast on the field of battle. They distinguished themselves in conquests waged to unify their land politically; but opinions about their heroism or villainy remained divisive because they often fought to protect their own ethnic, religious or cultural identity to the exclusion of others. It has therefore been a common feature even during its struggle for independence from British rule in the aftermath of WWII, that Sri Lankan heroes of one community were often perceived as villains by others.

Therefore at its birth as a modern nation state in 1948, the Dominion of Ceylon faced a serious deformity that would cripple it for decades to come. Strong nation states – more often than not – are born out of collective struggles; through which emerge their defining values, legends, myths and – perhaps most importantly – heroes that personify and embody all the vital elements of a nation’s identity as well as the aspirations of its people. While each community had their own leaders and historic legends, there weren’t a single heroic figure that represented the identity and aspirations of the young nation as a modern, united and pluralistic state. Instead, narrow visions of national identity and short-sighted politics led to decades of divisive communal violence. Most notably at the end of the war in 2009, Sri Lanka needed – more than ever – a voice of intelligent cosmopolitanism that could elevate the island nation from the divisive legacy of its past heroes and give cause for the myriad cultural and religious groups to unite. Yet, it was a void that the island’s conflicted history was ill-equipped to solve by itself.

Sri Lanka required a different kind of battlefield and a new and revolutionarily new type of heroes to emerge – who could unite its ancient peoples in heart and mind like never before. They came in the form of Arjuna Ranatunga and his own band of ten ‘not quite giant like’ men. As diverse a group as the people they represented – they came from the all walks of life including the urban middle class and the rural heartlands that had rarely filled the heroic template of heroes past. Their vocation was even more peculiar. Cricket was very much a symbol of foreign conquest and occupation of the island. Heroes were more likely to be made fighting it than playing the game. Besides, heroes and are often those inclined to imperil themselves in pursuit of immortal glory – not those who side with pragmatism or caution as Cricketers were required to be. Upul Tharanga was ever lauded for bravely chasing deliveries outside off stump nor Chandimal for courageously hooking bouncers down deep square-leg’s throat. But they nevertheless managed to achieve something that Sri Lankan heroes have never done before. 2201 years after the famous campaign of Dutugamunu and his ten giant worriers had briefly united it politically, a contrastingly modest and unassuming band of eleven men united Sri Lanka in heart and mind for the first time in the island’s history in 1996: when they won a world cup (or “THE world cup” – if you are Sri Lankan).

Until 1996 and then again in the early 2000s, Sri Lanka’s cricketers, much like the celebrated kings and rebels of their ancient past, were tragic heroes who valiantly resisted foreign attacks; but often failed despite their own bravery and ingenuity. Most notably, they failed against better equipped and organised conquerors. Yet, whereas history had often trickled down in little streams, they were a torrent that carved out in the space of a decade – a special space for Cricketers to stand among its pantheon of heroes. The legends of Aravinda and Sanath were created on the field. Underdogs for much of their careers, they rose heroically to often rescue Sri Lanka against intimidating oppositions and sometimes, singlehandedly carried the hopes of their nations to victory. But they were hardly consistent enough to be relied upon and their legends rarely not extend beyond the boundary ropes the same way their shots did.

The colonial legacy in Sri Lanka had left a deep and enduring imprint in its society and culture, and Cricket was no exception. Aside from a few exceptions like Duleep Mendis – Sri Lankan Cricketers were rather timid – easily satisfied with a draw against major test nations. Much like the Israelites who had to wonder in the wilderness for 44 years after being rescued from slavery in Egypt, it took the passing of two generations of Sri Lankan Cricketers, for them to unshackle themselves from the game they were drilled to play, and discover the way they were meant to play it. So, it was only with the generation of Cricketers that emerged in the 90s, that they had the lightness of memory and force of their own identity to disregard the text-books and express themselves more authentically. Romesh Kaluwitharana, Mahela Jayawardene, Avishka Gunawardene and Kumar Sangakkara – unlike even Arjuna and Aravinda’s generation – had no direct links to the Cricketers who had only played the game as they were taught by the masters of a forgotten era.

With the opening up of the Indian economy and the advent of dedicated sports TV channels in the 90s, the modern international game transformed into a commercial enterprise – almost unrecognisable from the refined pastime that it used to be, both on and off the field. In that context, it makes little sense to compare modern Cricketers against the greats of its past; the yardstick had changed. Yet, even in that comparison, Kumar Sangakkara statistically ranks among the best three test batsmen of all time. But Sri Lankans who celebrate his heroism don’t often cite statistics to quantify their argument. Where Cricket is much more than a sport, even numbers don’t mean what they say. As much as he has been relied upon consistently to bat his team and country to victory, people all over the world remained glued to their TVs after the match was over – to hear him speak. Though his hero’s journey had started on the pitch with bat in hand, he came to the fore with a microphone in hand at a podium.

Heroes are more inclined to monopolise the limelight than share it, so it would not have been a surprise if the war hero of Sri Lanka’s past and the Cricket hero of its present eventually clashed before one would emerge dominant while the other is relegated to the shadows of time. At an august gathering at Lord’s, two years after what mercifully turned out to be merely an ordeal in Lahore, Kumar recalled an encounter he had with an unknown soldier, at an obscure checkpoint somewhere in the labyrinth of Colombo’s streets. By the soldier’s own admission, the Cricketer was the more dominant and valuable of the two. Remarkably, Kumar had survived an armed attack just a week earlier. It is possible to imagine that the soldier would have never experienced the heat of battle himself – but could only hope that the next vehicle he hailed down to inspect would not be a fatal choice. Yet, the unknown soldier and the great Cricketer took turns appreciating each other’s contribution to their own lives and the life of their country – calling each other ‘heroes’ before departing, perhaps never to meet again. They were both right of course; but the Cricket star and soldier both were enhanced by that experience.

In that speech, Kumar went on to brew a cocktail of emotion, wit, humour passion and rage with his words that tugged at the heartstrings of the Cricketing world. From Sri Lankans in his worldwide audience, it drew tears. A few months earlier in November 2010, Mathews and Malinga had turned an impossible chase against the odds at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Jayawardene had scored a match saving century just weeks before. But, in the years since Arjuna and his team won the world cup in 1996, it was through Kumar’s voice that Cricket spoke most compellingly to Sri Lanka’s identity and aspirations. They were note merely tears of joy – his words also made Sri Lankans look at themselves in a way that made them sad, and angry, and laugh. That story and the broader content of his speech, has since become a mirror in with Sri Lankans can look at themselves and take stock in their bravest moments. Cricket writers all over the world have invariably wove it into the story of Cricket. Kumar grabbed the conscience of the world on that day in a way that it could never escape. Those who doubted him before could not escape his charm afterwards. His moving lecture at Lord’s was perhaps the inception of his heroic status in the international game, and the way he spoke and conducted himself outside the field has been the foundation of its longevity. But the roots of his legend lay buried deeper in the land and its history, up in the hills of Kandy.

Through much of the island’s history, the irrigated lowlands of the North and the fertile South Western plains nurtured Sri Lanka’s cultural, political and economic centres. The wealth of ancient Sri Lanka and its heroic architects were made in its northern and western plains. Vestiges of great monuments that had witnessed bygone times of immense prosperity and creativity, as well as the continuous cycles of conflict that raged over them, still lie in ruins there. Kandy did not feature in any legend or myth in all that time; no hero of consequence in Sri Lanka’s glorious past was ever known to have been born or raised there. Even with the ripening of time, Kandy could not produce a hero on its own accord. It required a long and remarkable collaboration with an occupying enemy and a struggle with its own geography.

A game like Cricket could never grow organically in the mountains around Kandy. Even when it was brought in as a foreign implant, roads had to be straightened and mountains – quite literally – had to be moved before the game could dig in its roots and draw from its fertile soils. One such effort was sparked by the vision of a man named Alek Garden Fraser who took over as Principal of Trinity College at the turn of the twentieth century. He wanted Trinity to have a Cricket field and ambitiously acquired crown land spanning over two nearby hills to build one. There was no heavy machinery or equipment at hand, so the students and staff of the school made their way to the site a few hundred yards from the school premises, every day; where over a couple of years, they cut down the bigger hill and filled the valley below to make a Cricket field. Kandy nurtured the two greatest Cricketers that Sri Lanka ever produced. Kumar learned his Cricket at Trinity and played much of his Cricket on the Ground that Fraser built; and nearly a century later, scored two test centuries and a double century there.

Fraser was not done however. Much to the displeasure of his own colonial secretary, he envisioned that his school should nurture Sri Lankan leaders who were immersed in their own culture and learn about their own history and proud heritage. Fraser made social service, the teaching of local languages and comparative religion a cornerstone of his education policies, much to the dismay of the colonial authorities at the time. Perhaps Kumar Sangakkara was innately predisposed to reach out to his own people with respect and empathy and speak against injustice. Perhaps it was instilled in him but the individuals and institutions that nurtured him. Whatever the case may be, the quality that people of Sri Lanka would later celebrate as his ‘heroism’ was not cultivated on the Cricket pitch alone. His empathy for the struggles and triumphs of life in many corners of Sri Lanka and of the world not only reflects the best features of the rebellious past and proud heritage of his people, but is also informed by a deep and heart-felt knowledge of it.

Heroism is always bestowed by popular consensus. It is the common man who elevates heroes to their status and immortalise them in legend. Heroes are made exceptional among the common and ordinary men and women of the land and that relationship is symbiotic. The legend of Kumar Sangakkara the man was made among victims of a Tsunami and inhabitants of a war-ravaged landscape in the North and East as much as by a fairy-tale test century at Lord’s. Kumar still speaks of the power of Cricket to unite and heal the diverse communities of his war ravaged country. If the reception he gets whenever he visits the north and east of Sri Lanka is anything to go by, few Sri Lankans have personified that message as effectively as he has. That is what makes him a hero. If heroes like him had lent themselves to previous generations, Sri Lanka could well have been a different place. Loved and respected by Sri Lankans of all cultural and religious backgrounds, as well as fans and opponents all over the world – the power of his personality has been unique among Sri Lanka’s pantheon of heroes in its ability to unite as well as inspire humility.

Especially in contemporary Sri Lanka – emerging from three decades of war – celebration of the lives of ‘war heroes’ comes naturally. Cricketers – at least until they won the World Cup in 1996 – were not more than celebrities, among actors and music stars. Merely six years after the war ended, Kumar and Mahela in particular have become iconic and exceptional heroes of their time – eclipsing even the heroes of contemporary military campaigns. The association of Cricketers to heroism – even after 1996 – especially in a country at war, was not only improbable but cut against the grain of the traditional mould of the nationalist heroes of the past. Yet, the privileged place that Cricket occupies in hearts and minds of people has deep roots in the grand and conflicting historical narrative of the island. ‘The boys’ – as Arjuna and Aravinda often referred to their teammates – have been a beacon of hope and an example of what Sri Lankans could be as a nation and as individuals. Heroics on the Cricket field infuse hope – and that hope is very different from the kind that military victories inspired. Kumar Sangakkara’s sensitivity to the heartbeat of his people and the humility with which he served the game and its fans has entwined his story and the story of Cricket with the proud history of his country and of the people for whom he played his Cricket.

But it was with these famous words, that he unites them;

I am Tamil, Sinhalese, Muslim and Burgher. I am a Buddhist, a Hindu, a follower of Islam and Christianity. I am today, and always, proudly Sri Lankan.

Through those words, he epitomised the hero that Sri Lanka, in his generation, so desperately needs. Described by Michael Roberts as an ecumenical Sri Lankan; in him, the diverse ethnic, religious and cultural communities of the island have found a hero they could all love and possess in equal measure. For a country that enjoys neither great influence nor privileged status among world powers, he has risen to capture the love and admiration of the world and represent the best of the proud history and rich culture of his people in a way that hardly any Sri Lankan has been able to do before. For that alone, he is without equal among all the heroes of our generation, and is arguably unparalleled in his Sir Lanka’s history and civilisation.

In a post-match interview, Kumar once famously called on his team mates to understand their place in history. As much as history is made by heroes, they are nevertheless fallible human beings. As much as they reflect what we can hope to be, they also stand to warn us against blindly attaching our future hopes and ambitions to individuals no matter how brave or virtuous they may be. Very few Cricketers have retained their ability to inspire and awe in life beyond the boundary. Some have even turned into villains. Therefore, being the astute student of history that he is, he will have an important message to deliver to his fans and team mates on the eve of his retirement; that the legends of heroes like him are not meant to be venerated, but to inspire. Their heroism is worth nothing if all they inspire is nostalgia and longing. The greatest heroes are those who make others feel they too can, and indeed must, become heroes themselves. Kumar is the son of a lawyer and a teacher – not of a Jewish carpenter and his virgin wife. In the years after his retirement, he will probably devote his time to raising his own children to be independent and productive citizens because every parent must by default, also be a hero. As much as he became a hero to his people when his country desperately needed one, the greatest tribute to his legacy would be to see more heroes like him emerge in years to come; not only from the Cricket fields but from many other walks of life.

Harendra Alwis as a Cricketer of dubious significance and an umpire with an incurable prejudice against batsmen who have bad footwork. He currently lives in Melbourne, Australia.

Related Articles

The need for humanitarianism is greater than ever, seventy five years of the geneva conventions, shared encounters from sri lanka, myanmar and thailand, lending sri lanka’s voice to the palestinian cause, gaza in end times, middle east madness and militias, anti-war protests: a missing dimension, south africa challenges israel’s final solution for palestine, emigration or death: us-israeli offer to gazans, zionism plus impunity: the mathematics of israel.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Duṭṭhagāmaṇī

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Duṭṭhagāmaṇī (died 137 bce or 77 bce , Anurādhapura , Sri Lanka) was a king of Sri Lanka who is remembered as a national hero for temporarily ending the domination of the Indian Tamil Hindus over the Sinhalese , most of whom were Buddhist . Though a historical figure, details of his life have become indistinguishable from myth , adding uncertainty to the precise dating of his reign and death.

The elder son of a petty Sinhalese king in the southeast, Duṭṭhagāmaṇī made plans to campaign against the Tamils in northern Sri Lanka by organizing 10 young chiefs to attack. His father opposed the plan and had him bound in chains; he escaped, however, and went into exile until after his father’s death. He twice fought his brother, Saddhā Tissa, and won the crown, as well as the state elephant Kaṇḍula, which was instrumental in his later victories. Saddhā Tissa penitently returned and pledged his loyalty to Duṭṭhagāmaṇī’s campaign. Duṭṭhagāmaṇī then led his troops and Kaṇḍula north to Anurādhapura, where he defeated and killed the Tamil leader Eḷāra. He later defeated Indian-recruited troops led by Eḷāra’s nephew Bhalluka and restored Sinhalese control of the entire island.

Duṭṭhagāmaṇī constructed the 1,600-pillared Brazen Palace in Anurādhapura and commenced building the Ruanveli dāgaba, a colossal stupa (shrine) containing the Buddha’s begging bowl and many of his bones. Duṭṭhagāmaṇī died before the shrine was completed, being deceived into thinking it had been finished by his followers, who had hastily constructed an imitation dome and spire before his death.

Sri Lanka Poems

Poems by Sri Lankans about life, nature, love, hate, war and many more……

S. Mahinda Thero

Serky Mahinda , better known as Tibet Jathika S. Mahinda Himi or S. Mahinda Thero, was born in 1901 in Gangtok, Sikkim, Tibet. He was a Bhikkhu (Buddhist monk) who became a well-known Sri Lankan poet and writer, and did an immense contribution to the independence movement of Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Before becoming a Buddhist monk, his name was Pempa Tendupi Serky Cherin and he lived with his family in Sikkim’s capital, Gangtok. He was the youngest son of a family with four brothers. In Sri Lanka he used the alias ‘S. Mahinda’ which later led everyone to believe that it was his real name. The “S” in his alias is believed to stand for Serky .

When Serki was about 14 years old he was offered a scholarship to learn about Buddhism in Sri Lanka. According to many sources he arrived to Sri Lanka in 1914. He was accompanied by one of his elder brothers, Sikkim Punnaji, who was also a Buddhist priest. He attained the Buddhist priesthood on the 14 th of June 1914. The name “Mahinda” was given to him by Gnanaloka Thero, the German monk who offered him the opportunity to come to Sri Lanka.

S. Mahinda Thero and his brother began to study Buddhism under Gnanaloka Thero in Polgasduwa temple in southern Sri Lanka. There Mahinda was ordained into the Amarapura Nikaya at Shailabimbaramaya in Dodanduwa by Piyaratana Nayake Thero (Chief Monk, Piyaratana). After that he went to the famous Vidyodaya Piriwena in Maradana (Colombo, Sri Lanka). While in Colombo he also entered to a college to study English. Then he came back to Polgasduwa temple to learn Pali and Sinhala languages. On 16 th of June 1930 S. Mahinda Thero became re-ordained to Shyamopali Nikaya. Later that same year Mahinda Thero raised Upasampada. Between 1934 and 1936 he worked as one of the teachers in Nalanda College in Colombo.

S. Mahinda Thero was able to become fluent in Sinhala language very quickly, and managed to establish as a renowned Sinhalese poet and writer. He was one of the most active members of the Sri Lankan independence movement. At a time when a British colonial government was ruling Sri Lanka, Mahinda Thero used his Sinhalese writing skills to draw Sri Lankans together to fight against the British rulers to get back their freedom. Because of his work, he was recognized as a national hero after Sri Lanka gained freedom on 1948.

Around 1921 Mahinda Thero wrote his first book ‘Ova Muthu Dama’ . He has authored more than 40 books. Most of his writings are poems and children’s books, which were intended to inspire patriotism of the readers. It is also believed that he has written many unpublished work. In most of his writings, he tried to focus on the former glory of Sri Lanka, and the flaws of its present citizens, and strived to urge them to rise up from their slumber and fight for their freedom. The book ‘Sri Pada’ is believed to be his final book.

Mahinda Thero passed away on the 16 th of May, 1951 when he was about 51 years old. Some believe that his ashes are kept in a container hanging on the roof top of the Mahabellana temple in Panadura with no proper means of protection.

A short verse from one of the most famous poetry written by Mahinda Thero:

English Translation:

Freedom is like the ocean And you, dear son, is the fountain of it Keep that in mind And try to fulfill the duty of protecting your motherland from various challenges

Poetry written by S. Mahinda Thero

- Ada Lak Mawage Puttu

- Jathika Thotilla

- Kumara Maha Vehera Venuma

- Kusumaanjalee

- Lama Kawu Kalamba

- Lanka Matha

- Morakola Gangarama Venuma

- Nandana Geetha

- Nidahase Dahena

- Nidahase Mantharaya

- Ova Muthu Dama

- Sinhala Jathiya

- Videshikayekugen Lak Mawta Namaskarayak

- Vil Lihini Sandeshaya

Books Written By S. Mahinda Thero

- Asadrusha Jathaka Vivaranaya

- Devani Rajasinghe

- Maha Parakramabahu

- Rahula Kumaraya

- Saddharma Maargaya (1, 2, 3, 4)

- Sinhala Saddhammopayanaya

Unpublished books written by S. Mahinda Thero

- Dodandoowa Sandeshaya

- Mithra Sandeshaya

Follow Sri Lanka Poems

Get every new post delivered to your Inbox

Join other followers:

- Book Reviews

- Pictorial Images

- Sinhala Mind-Set

- Speeding Up Links: Mirigama-Kurunegala Expressway Soon Operational

- Why Thuppahi

- Young Tourism Ambassadors in Jaffna

Remembering DS Senanayake on Sri Lanka’s Independence Day

Senanayake Foundation, I tem in Daily Mirror, 4 Feb 2022

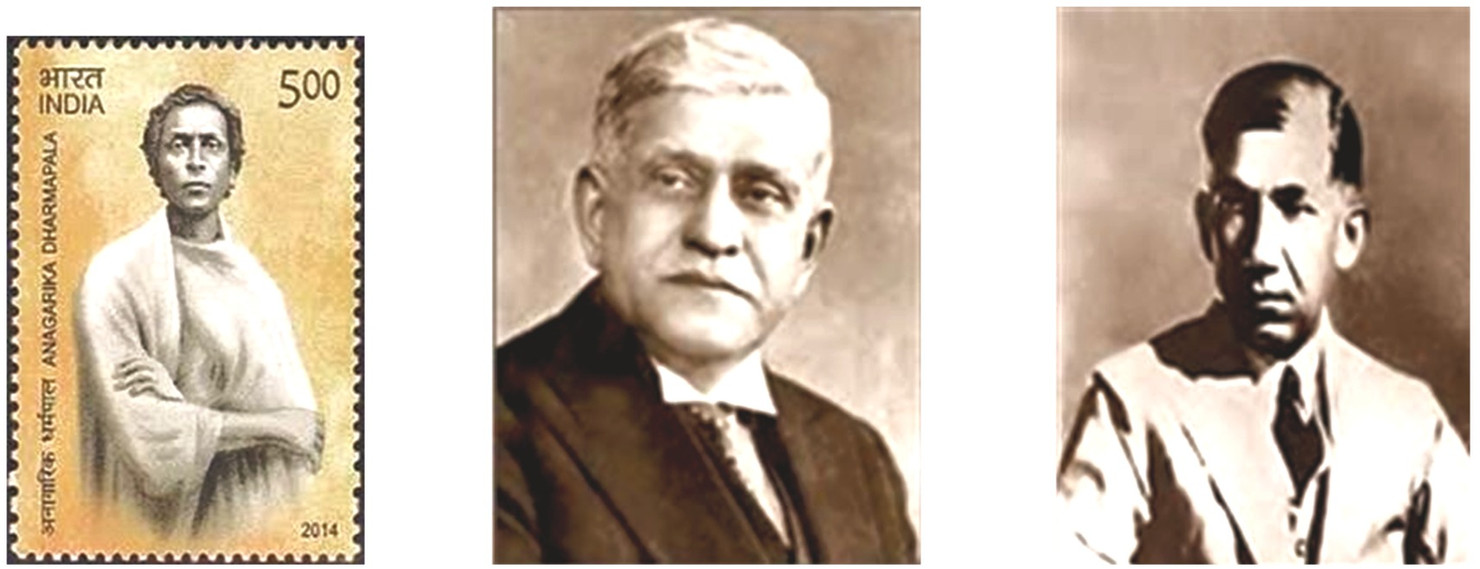

The first Prime Minister of Sri Lanka (Ceylon) D.S. Senanayake entered the National Legislature in 1924. He was relatively unknown in the country and was pushed into prominence by his elder brother F.R. Senanayake, who was a very popular and active figure in the social and political arena. Many were surprised and taken aback to see D.S. entering the political field, as they were expecting his brother F.R. to fit the role. Perhaps the only person who had faith in D.S’s capability at that time was none other but F.R. Senanayake himse lf.

Ceylon (Sri Lanka) as it was then known was under foreign domination from 1505 to 1948. Three Colonial Powers namely the Portuguese, Dutch and the British ruled parts of the island till 1815 when the entire country was subjugated to the British Government. Many a battle fought by our heroes at different times to free the country remained unsuccessful and the freedom struggles thus brutally subjugated became dormant until its last phase was initiated by F.R. Senanayake in 1915, after being released from imprisonment on false accusations. The Colonial Government imprisoned F.R. Senanayake along with his brother D.S. and a host of other Sinhala Buddhist leaders of the Temperance Movement on trumped-up charges. However, they had to be released as they could not find a shred of evidence against them. But the massacre of innocents under Martial Law continued unabated and F.R. Senanayake vowed to free the country from colonial bondage. He set about revitalizing the freedom movement that lay dormant for many years.

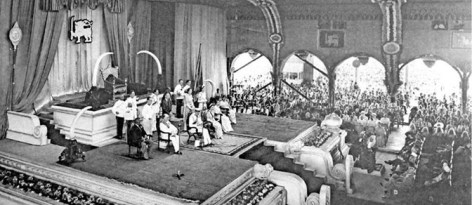

He became a dominant member of the Ceylon National Congress. Continuous agitation for reforms by the newly created Congress resulted in elections being held on a limited scale for the National Legislature in 1924 and F.R. supported his brother D.S. Senanayake to become an elected member of the Legislature. However, just two years later, in 1926, F.R. met with an untimely death at a relatively young age of 44. He was D.S.’s mentor and his death was not only an enormous blow to D.S. Senanayake but also a severe setback to the freedom movement. In fact, many thought that it was the end of the freedom struggle. But D.S. kept his brother’s dream alive and carefully planned and plotted the path to freedom. On 4th February 1948, twenty-four years after entering the National Legislature, D.S. Senanayake raised Lanka’s flag that was brought down by the British in 1815 and proclaimed to the world, Lanka’s Independence.

“Sir, when The Donoughmore Report was accepted I was one of those who were rather apprehensive of the success of the Committee system. At that time, I was not certain how the Constitution would work and what difficulties we would have to contend with. But since I have been in charge of a Committee for about a year I must say that my faith in the Committee system has increased considerably”

Freedom was achieved by many nations all over the world by pursuing either a path of non-violence or by the barrel of the gun. Polemics of revolt have shown us the methodologies advocated by Gandhi to Guevara, from the apostle of peace to the votary of violence. D.S. Senanayake, however, followed another way, the way of effective negotiations. It may have him taken twenty-four years to achieve this goal but he did so by periodically advancing towards freedom without spilling one drop of blood to achieve independence. Perhaps it was this peaceful transition that had created a misconception in the minds of some that freedom for Sri Lanka was gifted when India was granted her freedom.

India and Sri Lanka had their independent freedom struggles. While Indian leaders were seeking freedom through passive resistance, Sri Lankan leaders were represented in the Legislature following a path of active negotiations. It was the capabilities shown by our leaders in the administrative affairs of the country that prompted the then Governor Sir Hugh Clifford to recommend to the British Government in 1926, that the existing Constitution should be viewed as transitional and that a more representative Constitution should be installed. On this recommendation, the British Government appointed the Donoughmore Commission in 1927 to bring about reforms. India received a similar commission, namely the Simon Commission in 1928.

India, however, totally rejected the Simon Commission. They took up the position that the Simon Commission had no right to bring a constitution to India. Demanding Swaraj (independence outside the Commonwealth), non-corporation was unleashed by the Indian leaders throughout the streets of India. Sri Lankan leaders did not resort to the same manner. Though they did not accept the recommendations of the Donoughmore Commission in Toto, it was not rejected. The recommendations were taken up in the National Legislature, amended through debate and discussion, and the amended version was accepted as a step towards achieving self-government. In 1931, Sri Lanka became the first country in the whole of Asia to adopt universal suffrage with women being given the same voting rights as men; a feature that even some advanced European countries did not possess.

Though the Donoughmore Constitution did not measure up to the requirements of the elected representatives who were expecting a Westminster system of government, they were quite pleased with Adult Franchise and abolition of Communal Representation which were viewed as an obstruction to unification. The other main feature, Executive Committee System was received with mixed feelings. Deeply suspicious, D.S. Senanayake was very critical of the proposed Committee system. Having been involved in the functioning of existing committees, the unwanted delays experienced made him to view them as a hindrance rather than an asset to development. However, the amended form was accepted by him on the firm understanding that reforms were to follow.

Bitterly divided, the amended Donoughmore Constitution was accepted by only a slender majority. Leaders such as Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, E.W. Perera and C.W.W. Kannagara opposed the proposals while Sir D.B. Jayatilaka, D.S. Senanayake and W.A. De Silva supported the proposals. It was well known that it was D.S. Senanayake who used his influence to win over the majority for the proposals. He was of the view that though the proposed reforms did not measure up to what was expected, the proposals were a halfway measure to self-government and that it should be given a trial period. The Donoughmore Constitution gave birth to the State Council in 1931 and for the first time elected Representatives entered the realm of the executive. In the election process of the seven Executive Committees announced, chairmen of each committee were designated as Ministers, they were,

It is well known that no member of the Board of Ministers utilized Committees as much as D.S. Senanayake. Having realized that the mere possession of Executive power was meaningless unless it was utilized for the betterment of the masses, he used his Committee to restore all ancient tanks and embarked on massive irrigation schemes to provide water to the rural masses. He opened up the neglected Dry zone which was once the granary of ancient Lanka and settled the landless villages in vast colonization schemes making them a great asset to the nation. Speaking on the Committee system in the State Council on 19th July 1932, D.S. Senanayake said, “Sir, when The Donoughmore Report was accepted I was one of those who were rather apprehensive of the success of the Committee system. At that time, I was not certain how the Constitution would work and what difficulties we would have to contend with. But since I have been in charge of a Committee for about a year I must say that my faith in the Committee system has increased considerably.”

“I feel it is a mistake, a great mistake, to make an attempt to separate the people communally, and make a Constitution whereby the people will forever remain separated communally. If we want to progress, let us all unite. If we try to pander to the feelings of a section of the people, all that will happen is that we will be dividing the people, and that is the greatest danger that can befall any country”

Though many an achievement was made under the Donoughmore Constitution which was in operation for sixteen years, it did not always bring about smooth administration. There were many clashes between the elected Representatives and the Colonial bureaucrats; as such there was continuous agitation for reforms by both the State Council and the Ceylon National Congress. As a result, in May 1943, the Colonial government made a declaration authorizing the Board of Ministers to draft a Constitution within certain parameters and stipulated that the proposed Constitution should be ratified by at least seventy-five percent of the State Council. The Ministers welcomed this offer and proceeded to draft a Constitution with the aim of obtaining ‘Dominion Status’, the surest way for attaining independence. The task was completed in four months, and the draft was submitted to the Governor to be presented to the Secretary of State for approval. However, what they received was a rude shock.

On 5th July 1944, the House of Commons made an announcement that a Commission will be appointed to: ‘To visit Ceylon in order to examine and discuss any proposals for constitutional reforms in the Island which have the object of giving effect to the Declaration of His Majesty’s Government on that subject dated 26th May 1943, and after consultation with various interests in the Island, including minority communities, concerned with the subjects of constitutional reforms, to advise His Majesty’s Government on all measures necessary to attain that object.’ This was a sinister deviation from the original Declaration and a gross breach of trust. Sir John Kotelawala in his autobiography “An Asian Prime Minister’s Story” refers to this incident. He states,

“Sir Ivor Jennings, the great authority on Constitutional questions, has expressed the view that the terms of reference of the Soulbury Commission, appointed in 1944, were undoubtedly a breach of an understanding given by the British Government in May 1943. ‘What is worse,’ says Sir Ivor, ‘was the manner in which this breach was brought about. It left a very nasty taste in one’s mouth.’ When it was all over, Colonel Oliver Stanley, Secretary of State for Colonies, remarked with typical English understatement that this affair had been badly handled.” Many Members of the State Council and of the Ceylon National Congress were aghast at this decision. They began to doubt the sincerity of the British Government. D.S. Senanayake, though disappointed and critical of what had happened, realized that sabotage had emanated from within and not from outside. Referring to this in the State Council on 23rd November 1944, he said,

“As the hon. Members are aware, we received a Declaration to which we gave our interpretation, and on that interpretation, we grafted a constitution. We then decided – at least I had stated our decision was – that we should submit that Constitution to the Secretary of State first and that if it was considered acceptable to him we should bring it here for the approval of a 75 per cent majority of Members of this house ….. You see, Sir, when we drafted that Constitution we sent it to the Secretary of State and I believe, up to this day there was no conditions stipulated that a Commission should come out to examine the views of the interests that were here. If that was so, there was no need for them to tell us that it should get the approval of a 75 per cent majority in this House.

I believe, and I honestly believe, that the reasons for sending a Commission here to consider various interests is due to the fact that the draft Constitution which was submitted by the Board of Ministers and which met with the requirements of the Secretary of State laid down in his Declaration is not the kind of Constitution that those who had influence with the Secretary of State expected us to bring out. So they felt that it was time to sabotage it.”

He went on to say,

“… I feel it is a mistake, a great mistake, to make an attempt to separate the people communally, and make a Constitution whereby the people will forever remain separated communally. If we want to progress, let us all unite. If we try to pander to the feelings of a section of the people, all that will happen is that we will be dividing the people, and that is the greatest danger that can befall any country. It is because of that danger that I do not want communal representation; it is not that I object to two seats here or two seats there. As long as there is this feeling that each community should be separated politically, that there should be this cleavage between community and community, those ideas will penetrate into our whole social life, our whole economic life, into all our activities in this country.

DS and OEG in London in 1946(?) to press for independence

Dismissing the minority phobia, DS said,

“When I suggested the procedure we adopted first, namely, that we deal with the Secretary of State and then the Council, I can honestly tell you that in my own mind I had no desire for Sinhalese domination, or Tamil domination, or European domination; my whole desire was for Ceylonese domination, and the freedom I wanted was for the people of Ceylon.” There was huge agitation to boycott the Soulbury Commission that arrived on the island on 22nd December 1945. D.S. Senanayake, however, did not identify himself with such clamour. He was of the view that the Soulbury Commission should be won over to their way of thinking, and though the Ministers never gave evidence officially, they had many discussions with the Commissioners. D.S. Senanayake in particular had numerous discussions with the Commissioners and even accompanied them on their visits to all parts of the Island. Lord Soulbury was greatly impressed by D.S. Senanayake took an instant liking to him. Lord Soulbury’s attitude and D.S. Senanayake’s commitment helped to rectify the stained relationship between the Imperial Government and the Board of Ministers, and most importantly it paved the way for D.S. Senanayake to obtain the approval for the Constitution that he was eagerly waiting for.

The Soulbury Report was published in September 1945, and a White Paper on the intentions of His Majesty’s Government was published on 31st October 1945. Though D.S.

Senanayake’s recommendations were included and further advancement had been made, the granting of Dominion Status was postponed. It is believed that the defeat of the Conservative Government in 1945 and the Labour Party assuming office caused this change as the new Secretary of State George Hall, who replaced Colonel Oliver Stanley, was not so amiable to the granting of Dominion Status. Had there been no change of government, Colonel Stanley would have remained as the Secretary of State and Sri Lanka on track to receive Dominion Status in 1945. Anyhow it was conceded that the New Constitution if adopted by the State Council, the Imperial Government would pave the way for the attainment of Dominion Status within a short space of time. On this understanding, on 8th November 1945, D.S. Senanayake moved the following motion in the State Council.

“This House expresses disappointment that His Majesty’s Government has deferred the admission of Ceylon to full Dominion status, but in view of the assurance contained in the White Paper of October 31, 1945, that His Majesty’s Government will co-operate with the people of Ceylon so that such status may be attained by this country in a comparatively short time, this House resolves that the Constitution offered in the said White Paper “’be accepted during the interim period.”

Addressing the State Council on 8th November 1945, D.S. Senanayake went on to say,

“I was invited to London by Colonel Stanley, but my negotiations were conducted with the new Secretary of State, Mr Hall. I should like at the outset to bear witness to the encouragement which I received from both of them. It has been a weakness in our case that we have had to correspond by telegram. They have not known the depth of our feelings; we have been suspicious of their intentions. Colonel Stanley was Colonial Secretary for most of the war. He was aware of the importance of our co-operation in the war effort; he was anxious to secure our political advancement; in him, I am convinced, we have a true friend. Mr Hall – who is, if I may say so, a miner like myself – came fresh to the problems of Ceylon. It was inevitable that he, and the Government of which he was a member, should require time for the consideration of our problems. That he and they approached with sympathy is proved by the result. For the Declaration which I ask you to accept is better than the Declaration of 1943, better than the Minister’s draft and better than the Soulbury Report.”

In his lengthy speech, he touched upon all aspects from the freedom movement, its origin, obstacles encountered, sabotage experienced and finally the achievement of the moment of freedom.

Allaying the fears of the Minority, he said,

“The road to freedom was by no means straight. That we were correct in our procedure is proved by paragraph 12 of the White Paper, and I am glad that His Majesty’s Government has had the generosity to admit that we were right. We did all that we were asked to do and with a speed which, I think, surprised Whitehall. The procedure was changed not by us but by His Majesty’s Government, and the change was due solely to the representations of the minorities. After those representations, His Majesty’s Government felt the whole question should be examined by a Commission. We protested as we were bound to do, at what we regarded as a breach of an undertaking. I am convinced, after hearing the case put in London, that the charge was due to an excess of caution. It was felt that the minorities should be given every opportunity of proving their case if they could. They were given every opportunity, and they took it. The Ministers allowed their draft to speak for itself. If the Commissioners wanted to see anything, we showed it to them, but we gave no evidence. The fact that we gave no evidence has had two excellent results.

“First, the minorities said what they pleased and how they pleased. The Ministers were relieved of the temptation to retaliate. In this way we were, I hope, able to avoid adding to the bitterness and ill-will that we so correctly prophesied in 1941. If anybody ought to feel aggrieved it was those who were so bitterly attacked, but we do not feel aggrieved because the verdict has been in our favour. Secondly, that verdict is more impressive because we left our proposals to speak for themselves. “No reasonable person can now doubt the honesty of our intentions. We devised a scheme which gave heavy weightage to the minorities; we deliberately protected them against discriminatory legislation; we vested important powers in the Governor-General because we thought that the minorities would regard him as impartial; we decided upon an independent Public Service Commission so as to give an assurance that there should be no communalism in the Public Service. All these have been accepted by the Soulbury Commission and quoted by them as devices to protect the minorities.

Commending the White Paper, he said,

“The great advantage of the White Paper is that it gives us complete self-government and puts an end to Commissions. If hon. Members who study the White Paper alone will obtain a false picture. It emphasizes the restrictions and precautions. What they should study is the new Constitution. I have had a new draft prepared and I have compared it with the Constitutions of the Dominions. I can assure the House that there is nothing in it that might not be in the Constitution of a Dominion. In fact, in one respect it goes much further than any Dominion Constitution except that of Eire. It provides specifically and positively for responsible government; and this means responsible government in all matters of administration, civil and military, internal and external.”

He concluded his speech by saying,

“The present proposal is for an interim period. We want Dominion Status in the shortest possible space of time. To achieve it we must show not only that we have successfully worked the self-government that the White Paper promises, but also that we are fundamentally agreed no matter what may be our politics or communities. In a short time, the Cabinet will demand the fulfilment of the promises in the White Paper. Their hands can be immensely strengthened by this House and now. Every time we ask for a constitutional advance we are met by the argument that we are not agreed. Let us show that we are agreed by accepting this motion with a majority so overwhelming that nobody dares to use the argument against us again. I am not asking for a majority; I am asking for a unanimous vote.

“It is because of that danger that I do not want communal representation; it is not that I object to two seats here or two seats there. As long as there is this feeling that each community should be separated politically, that there should be this cleavage between community and community, those ideas will penetrate into our whole social life, our whole economic life, into all our activities in this country”

And for what are you being asked to vote? It is a motion to wipe out the Donoughmore Constitution with all its qualifications and limitations and to place the destinies of this country in the hands of its people. It is a motion to end our political subjection and to enable us to devote ourselves to the welfare of the Island freed from these interminable constitutional disputes. A vote for this motion is a vote for Lanka, and it is a pleasure and a privilege to move it.”

The State Council endorsed the Motion in an unprecedented manner; fifty-one Members voted for it while only three voted against it. Those who voted against were two Indian Tamils and one Sinhalese namely W. Dahanayake. D.S. Senanayake triumphantly cabled Lord Soulbury that he obtained 95% of the vote in favour of the proposals. Dominion Status that was promised within three years after the adoption of the White Paper was granted in two years. In February 1947, D.S. Senanayake addressed a personal letter to the Secretary of State through the Governor requesting that Dominion Status be granted to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). This request was supported by the Governor. Three months later, in June 1947, an announcement was made in the House of Commons that, as soon as the new government assumes office, negotiations would begin to confer ‘fully self-governing Status’ to Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

The General Election was held in August 1947, The United National Party became the largest party in the House of Representatives, and since D.S Senanayake had the support of the majority of the Members he became the obvious choice as Prime Minister. The Ceylon Independence Bill was introduced in the House of Commons on 13th November 1947, and on 10th December 1947, The Ceylon Independence Act received Royal Assent. On 3rd February 1948 Ceylon (Sri Lanka) ceased to be a Colony. Four Hundred years of foreign domination came to an end and D.S. Senanayake took his rightful position as the ‘Father of the Nation’.

Sri Lanka never modelled itself or followed India’s path to Independence. Until the eleventh hour, India was demanding Swaraj and not Dominion Status. During this period India was involved in widespread demonstrations advocating non-corporation and asking the Imperial Government to quit India while almost all their leaders were languishing in jail. It was perhaps the decision to create Pakistan that made them change their demand to Dominion Status within the Empire, the position Ceylon (Sri Lanka) clung to from the very inception. The creation of Pakistan not only marked the division of India but also brought about unprecedented communal violence where millions lost their lives. The only country that took India’s demand of ‘Swaraj’ to its logical conclusion was Burma and even Burma after becoming an independent nation outside the Empire, proceeded to sign a defence agreement with the United Kingdom. On the other hand, D.S. Senanayake never deviated from his demand for Dominion Status. He was successful in uniting all communities and united, marched to freedom without shedding a drop of blood. It is the sheer ignorance of these facts that has prompted some to erroneously believe that Sri Lanka’s freedom was an extension of India’s Independence.

Sceptics have castigated our independence as a half-baked measure and that it was not real freedom. “Defence Agreements entered into with the British Government have been highlighted to show that Sri Lanka was never really free and that real freedom came in 1956 when the Defence Pact was abrogated. One begins to wonder how a Pact can be abrogated unless the Country concerned had the right to do so. It was the inherent right of Independence that allowed the abrogation of the Defence Pact.

The independence of a country is not judged by the presence of defence pacts or the presence of foreign forces in the country concerned, but on the right of that country to abrogate such pacts or remove foreign troops if they so desire. Even today free nations stationing of foreign troops and holding defence pacts can be seen all over the world. D.S. Senanayake did enter into a Defense pact with the United Kingdom not because it was forced on him but because he wanted it as a safeguard from external aggression. Introducing these agreements in Parliament on 3rd December 1947, D.S. Senanayake told Parliament that,

“The agreements became necessary for no other reason but because of the obligations that Britain had undertaken on our behalf. There was, therefore, this necessity for an agreement before Dominion Status was granted. Besides that, our own interest needed to have an agreement to provide for our defence.”

“Now with regard to this Agreement, my Good Friend was not quite logical when he said that we would be prevented from terminating this agreement by virtue of the fact it did not stipulate a definite period, and that therefore we have no remedy. But these are mutual agreements to be entered into at different times. There is no question of giving bases to anyone. There was a question bases being found in Ceylon, but I was certainly not prepared to grant any. What I felt was that if at any time we wanted the assistance of England we should be able to get that assistance by agreement, and if necessary for that purpose to get their aeroplanes we should give them aerodromes. There is no question of any bases being given to her. They were only to be given when it becomes necessary, in our own interest, and after entering into an agreement.” So far as these agreements are concerned, it has definitely stated that they will be in force only during such time as they are necessary.” Referring to the Defence Agreement sought by Burma that had become independent from the United Kingdom, he went on to say, “As far as Burma is concerned, she has got independence outside the British Empire, but she has come to an agreement with Britain. She is independent, but there is an agreement with Britain –

……. Now that is a country that has obtained independence. But the people feel that it is in the interest of Burma itself and in the common interest to come to such an agreement. But as far we are concerned, what is the position? We say we belong to one family, we have mutual interests, and it is by mutual agreement that we are able to decide what is to be done. I feel that does not in any way remove our independence; it only means that we can maintain our independence” in our country. There is a good deal more that I should like to say, but I think I have said enough. I feel sure that no’ Member of this House or anyone outside can say that we could have more speedily better and more secure Agreements than those we have got. All those who have the love of this country at heart should rejoice not only over our getting freedom but over securing these Agreements, so that we may be safe in Ceylon.”

Parliament approved these agreements on 3rd December 1947. Incidentally, even S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike who abrogated this pact in 1956, voted in favour of these agreements. What he did may have been a popular decision as cutting off ties with the former Colonial Ruler was widely acceptable emotionally. But it certainly did expose Sri Lanka to brazen interference by our giant neighbour and we still continue to pay a heavy price for it.

D.S. Senanayake never advocated that Sri Lanka should have a permanent Defence Pact with the United Kingdom but that to protect our newly won freedom we need the protection of a powerful Nation and at that time the best source was the United Kingdom. Referring to this predicament as far back as 23rd November 1944, speaking in the State Council of Ceylon on Reforms (Introduction of Constituent Bill), he stated, “It may be that there will be a time when perhaps the British will not be our best shield; we may then join some other Commonwealth or come to some arrangement with some other people. But as long as there is no nation I could think of which is better than the British, I would like to get Dominion Status for Ceylon within the Empire. Now at this time, when countries, even big nations, consider it necessary that they should come to some arrangement for the protecting each other, I think it would be foolhardy on our part to think that we can stand by ourselves.”

Harbouring deep suspicions on the intentions of our giant neighbour; D.S. Senanayake was convinced that we need a defence arrangement with a powerful country for our safety. However, after his demise in 1952, the United National Party Government led by Sir John Kotelawala was defeated in 1956 and S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike who was elected Prime Minister proceeded to abrogate the defence pact with the United Kingdom. What followed thereafter was blatant interference in our internal affairs and continued infringement of our sovereignty. What we had to experience and continue to experience to date, more than justifies D.S. Senanayake’s suspicions.

Sri Lanka was plagued with a foreign-sponsored armed terrorist organization committed to the division of our country. It took a herculean effort from our armed forces to free the country from this brutal terror. Now, in the name of peace, another threat armed with international repercussions has emerged that threatens the very existence of this nation. It is our bounden duty to save our country from being dismembered and its dominance passed to Foreign Nations. If not greatest .disservice will be done to our National Heroes and another despicable betrayal will be featured in our history.

***** *****

Share this:

Filed under accountability , architects & architecture , British imperialism , colonisation schemes , constitutional amendments , democratic measures , governance , historical interpretation , legal issues , life stories , nationalism , patriotism , politIcal discourse , power politics , Sinhala-Tamil Relations , sri lankan society , truth as casualty of war , unusual people , welfare & philanthophy , world events & processes

One response to “ Remembering DS Senanayake on Sri Lanka’s Independence Day ”

Sri Lankans love to live in the past remembering, commemorating leaders and kings. Time to change the gear from reverse position to a forward position.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Sri Lanka A beat South Africa in South Africa … A Feat

- Chance Encounters: A Pot Pourri of Books on Sri Lanka

- The Roberts Oral History Project, 1964-1969: Its Conception, Inception & Outcomes

- Up Yours! The English Middle Finger INSULT Directed at the French

- The Stark Political Choices Facing Sri Lanka’s Voters

- Professor EOE Pereira’s Central Role in Fostering Engineering Education

- Gamini Goonetilleke’s Wide-ranging Medical Work in Lanka

- An Intriguing Photo: Charlie Chaplin at the Dalada Maligawa in 1932

- The “Deep State”– Threats to Democracy within Today’s Western States’its

- Face-to-Face in Admonishment: Drama at the Adelaide Oval, 23rd January 1998

- 9/11 Attacks (1)

- Aboriginality (30)

- accountability (3,512)

- Afghanistan (47)

- Africans in Asia (6)

- Afro-Asians (8)

- Al Qaeda (70)

- american imperialism (674)

- ancient civilisations (137)

- anti-racism (117)

- anton balasingham (26)

- arab regimes (106)

- architects & architecture (277)

- architectural innovation (4)

- art & allure bewitching (806)

- Artic exploration (1)

- asylum-seekers (248)

- atrocities (591)

- Australian culture (445)

- australian media (653)

- authoritarian regimes (1,044)

- biotechnology (35)

- Bodu Bala Sena (23)

- Britain's politics (24)

- British colonialism (576)

- British imperialism (314)

- Buddhism (184)

- Canadian politics (5)

- caste issues (91)

- centre-periphery relations (1,442)

- charitable outreach (407)

- chauvinism (145)

- China and Chinese influences (274)

- citizen journalism (286)

- climate change issues (7)

- Colombo and Its Spaces (77)

- colonisation schemes (43)

- commoditification (198)

- communal relations (989)

- conspiracies (216)

- constitutional amendments (205)

- coronavirus (110)

- counter-insurgency (23)

- cricket for amity (473)

- cricket selections (196)

- Cuba in this world (3)

- cultural transmission (2,562)

- de-mining (4)

- debt restructuring (38)

- democratic measures (685)

- demography (130)

- devolution (143)

- disaster relief team (51)

- discrimination (416)

- disparagement (821)

- doctoring evidence (250)

- Dutch colonialism (33)

- economic processes (1,845)

- education (1,055)

- education policy (99)

- Eelam (213)

- electoral structures (193)

- elephant tales (54)

- Empire loyalism (31)

- energy resources (68)

- environmental degradation (29)

- espionage (4)

- ethnicity (1,210)

- European history (86)

- evolution of languages(s) (11)

- export issues (60)

- Fascism (108)

- female empowerment (307)

- foreign policy (459)

- fundamentalism (357)

- gender norms (53)

- gordon weiss (48)

- governance (1,835)

- growth pole (78)

- hatan kavi (18)

- heritage (2,030)

- Hinduism (40)

- historical interpretation (3,830)

- historical novel (7)

- Hitler (62)

- human rights (487)

- IDP camps (68)

- IMF as monster (16)

- immigration (114)

- immolation (15)

- indian armed forces (25)

- Indian General Elections (10)

- Indian Ocean politics (1,056)

- Indian Premier League cricket (1)

- Indian religions (145)

- Indian traditions (256)