From Use to Overuse: Digital Inequality in the Age of Communication Abundance

- Social Science Computer Review 39(1):089443931985116

- 39(1):089443931985116

- Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca

- University of Zurich

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

Supplementary resource (1)

- Xiaoming Zhang

- BEHAV INFORM TECHNOL

- Elizabeth Hunt

- NEW MEDIA SOC

- Miriana Cascone

- INT J INFORM MANAGE

- ADDICT BEHAV

- Christoph Klimmt

- Marco Fasoli

- COMMUN THEOR

- JiHye J. Kim

- James C. Witte

- Susan E. Mannon

- SOC SCI COMPUT REV

- Detlef H. Rost

- Theodora Sutton

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS & VIEWS FORUM

- 10 February 2020

Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health

- Jonathan Haidt &

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

The topic in brief

• There is an ongoing debate about whether social media and the use of digital devices are detrimental to mental health.

• Adolescents tend to be heavy users of these devices, and especially of social media.

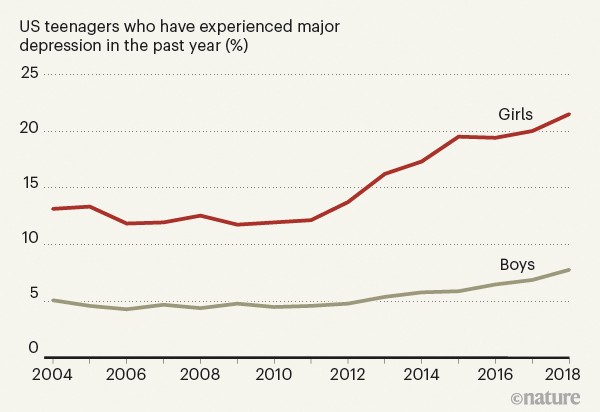

• Rates of teenage depression began to rise around 2012, when adolescent use of social media became common (Fig. 1).

• Some evidence indicates that frequent users of social media have higher rates of depression and anxiety than do light users.

• But perhaps digital devices could provide a way of gathering data about mental health in a systematic way, and make interventions more timely.

Figure 1 | Depression on the rise. Rates of depression among teenagers in the United States have increased steadily since 2012. Rates are higher and are increasing more rapidly for girls than for boys. Some researchers think that social media is the cause of this increase, whereas others see social media as a way of tackling it. (Data taken from the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Table 11.2b; go.nature.com/3ayjaww )

JONATHAN HAIDT: A guilty verdict

A sudden increase in the rates of depression, anxiety and self-harm was seen in adolescents — particularly girls — in the United States and the United Kingdom around 2012 or 2013 (see go.nature.com/2up38hw ). Only one suspect was in the right place at the right time to account for this sudden change: social media. Its use by teenagers increased most quickly between 2009 and 2011, by which point two-thirds of 15–17-year-olds were using it on a daily basis 1 . Some researchers defend social media, arguing that there is only circumstantial evidence for its role in mental-health problems 2 , 3 . And, indeed, several studies 2 , 3 show that there is only a small correlation between time spent on screens and bad mental-health outcomes. However, I present three arguments against this defence.

First, the papers that report small or null effects usually focus on ‘screen time’, but it is not films or video chats with friends that damage mental health. When research papers allow us to zoom in on social media, rather than looking at screen time as a whole, the correlations with depression are larger, and they are larger still when we look specifically at girls ( go.nature.com/2u74der ). The sex difference is robust, and there are several likely causes for it. Girls use social media much more than do boys (who, in turn, spend more of their time gaming). And, for girls more than boys, social life and status tend to revolve around intimacy and inclusion versus exclusion 4 , making them more vulnerable to both the ‘fear of missing out’ and the relational aggression that social media facilitates.

Second, although correlational studies can provide only circumstantial evidence, most of the experiments published in recent years have found evidence of causation ( go.nature.com/2u74der ). In these studies, people are randomly assigned to groups that are asked to continue using social media or to reduce their use substantially. After a few weeks, people who reduce their use generally report an improvement in mood or a reduction in loneliness or symptoms of depression.

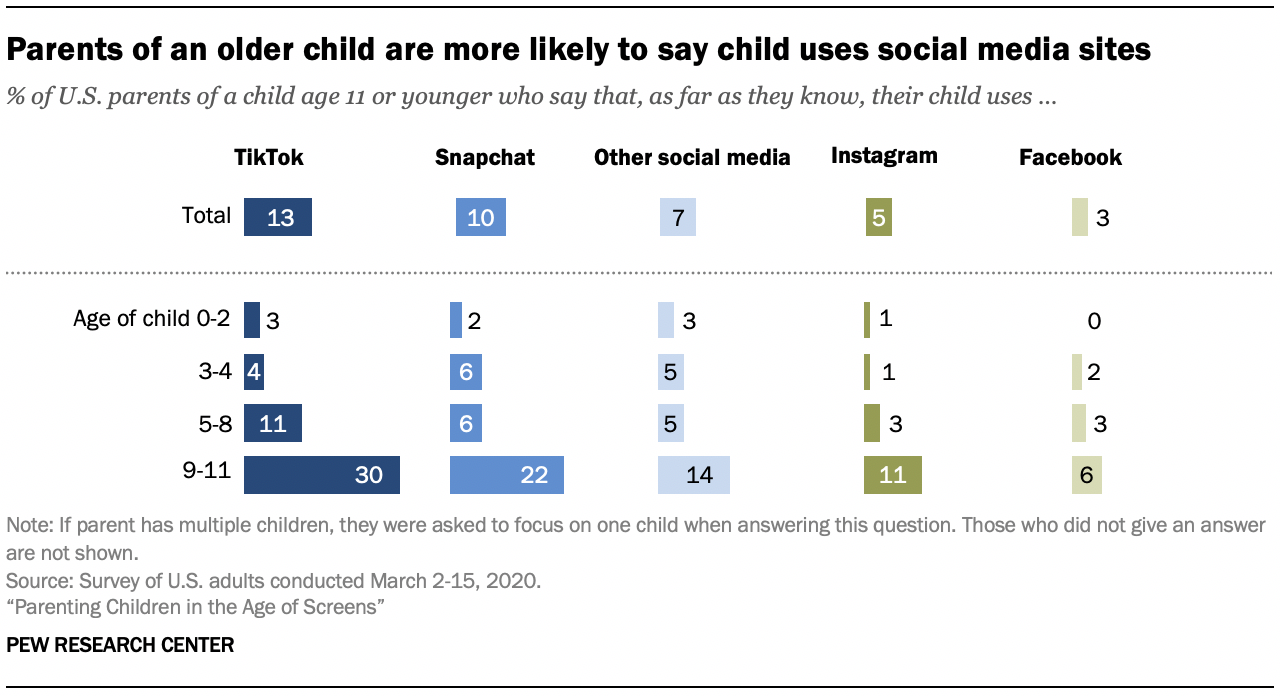

The best way forward

Third, many researchers seem to be thinking about social media as if it were sugar: safe in small to moderate quantities, and harmful only if teenagers consume large quantities. But, unlike sugar, social media does not act just on those who consume it. It has radically transformed the nature of peer relationships, family relationships and daily activities 5 . When most of the 11-year-olds in a class are on Instagram (as was the case in my son’s school), there can be pervasive effects on everyone. Children who opt out can find themselves isolated. A simple dose–response model cannot capture the full effects of social media, yet nearly all of the debate among researchers so far has been over the size of the dose–response effect. To cite just one suggestive finding of what lies beyond that model: network effects for depression and anxiety are large, and bad mental health spreads more contagiously between women than between men 6 .

In conclusion, digital media in general undoubtedly has many beneficial uses, including the treatment of mental illness. But if you focus on social media, you’ll find stronger evidence of harm, and less exculpatory evidence, especially for its millions of under-age users.

What should we do while researchers hash out the meaning of these conflicting findings? I would urge a focus on middle schools (roughly 11–13-year-olds in the United States), both for researchers and policymakers. Any US state could quickly conduct an informative experiment beginning this September: randomly assign a portion of school districts to ban smartphone access for students in middle school, while strongly encouraging parents to prevent their children from opening social-media accounts until they begin high school (at around 14). Within 2 years, we would know whether the policy reversed the otherwise steady rise of mental-health problems among middle-school students, and whether it also improved classroom dynamics (as rated by teachers) and test scores. Such system-wide and cross-school interventions would be an excellent way to study the emergent effects of social media on the social lives and mental health of today’s adolescents.

NICK ALLEN: Use digital technology to our advantage

It is appealing to condemn social media out of hand on the basis of the — generally rather poor-quality and inconsistent — evidence suggesting that its use is associated with mental-health problems 7 . But focusing only on its potential harmful effects is comparable to proposing that the only question to ask about cars is whether people can die driving them. The harmful effects might be real, but they don’t tell the full story. The task of research should be to understand what patterns of digital-device and social-media use can lead to beneficial versus harmful effects 7 , and to inform evidence-based approaches to policy, education and regulation.

Long-standing problems have hampered our efforts to improve access to, and the quality of, mental-health services and support. Digital technology has the potential to address some of these challenges. For instance, consider the challenges associated with collecting data on human behaviour. Assessment in mental-health care and research relies almost exclusively on self-reporting, but the resulting data are subjective and burdensome to collect. As a result, assessments are conducted so infrequently that they do not provide insights into the temporal dynamics of symptoms, which can be crucial for both diagnosis and treatment planning.

By contrast, mobile phones and other Internet-connected devices provide an opportunity to continuously collect objective information on behaviour in the context of people’s real lives, generating a rich data set that can provide insight into the extent and timing of mental-health needs in individuals 8 , 9 . By building apps that can track our digital exhaust (the data generated by our everyday digital lives, including our social-media use), we can gain insights into aspects of behaviour that are well-established building blocks of mental health and illness, such as mood, social communication, sleep and physical activity.

Stress and the city

These data can, in turn, be used to empower individuals, by giving them actionable insights into patterns of behaviour that might otherwise have remained unseen. For example, subtle shifts in patterns of sleep or social communication can provide early warning signs of deteriorating mental health. Data on these patterns can be used to alert people to the need for self-management before the patterns — and the associated symptoms — become more severe. Individuals can also choose to share these data with health professionals or researchers. For instance, in the Our Data Helps initiative, individuals who have experienced a suicidal crisis, or the relatives of those who have died by suicide, can donate their digital data to research into suicide risk.

Because mobile devices are ever-present in people’s lives, they offer an opportunity to provide interventions that are timely, personalized and scalable. Currently, mental-health services are mainly provided through a century-old model in which they are made available at times chosen by the mental-health practitioner, rather than at the person’s time of greatest need. But Internet-connected devices are facilitating the development of a wave of ‘just-in-time’ interventions 10 for mental-health care and support.

A compelling example of these interventions involves short-term risk for suicide 9 , 11 — for which early detection could save many lives. Most of the effective approaches to suicide prevention work by interrupting suicidal actions and supporting alternative methods of coping at the moment of greatest risk. If these moments can be detected in an individual’s digital exhaust, a wide range of intervention options become available, from providing information about coping skills and social support, to the initiation of crisis responses. So far, just-in-time approaches have been applied mainly to behaviours such as eating or substance abuse 8 . But with the development of an appropriate research base, these approaches have the potential to provide a major advance in our ability to respond to, and prevent, mental-health crises.

These advantages are particularly relevant to teenagers. Because of their extensive use of digital devices, adolescents are especially vulnerable to the devices’ risks and burdens. And, given the increases in mental-health problems in this age group, teens would also benefit most from improvements in mental-health prevention and treatment. If we use the social and data-gathering functions of Internet-connected devices in the right ways, we might achieve breakthroughs in our ability to improve mental health and well-being.

Nature 578 , 226-227 (2020)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x

Twenge, J. M., Martin, G. N. & Spitzberg, B. H. Psychol. Pop. Media Culture 8 , 329–345 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. Nature Hum. Behav. 3 , 173–182 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Odgers, C. L. & Jensen, M. R. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13190 (2020).

Maccoby, E. E. The Two Sexes: Growing Up Apart, Coming Together Ch. 2 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1999).

Google Scholar

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S. & Prinstein, M. J. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 21 , 267–294 (2018).

Rosenquist, J. N., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Molec. Psychiatry 16 , 273–281 (2011).

Orben, A. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4 (2020).

Mohr, D. C., Zhang, M. & Schueller, S. M. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 13 , 23–47 (2017).

Nelson, B. W. & Allen, N. B. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 , 718–733 (2018).

Nahum-Shani, I. et al. Ann. Behav. Med. 52 , 446–462 (2018).

Allen, N. B., Nelson, B. W., Brent, D. & Auerbach, R. P. J. Affect. Disord. 250 , 163–169 (2019).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Competing Interests

N.A. has an equity interest in Ksana Health, a company he co-founded and which has the sole commercial licence for certain versions of the Effortless Assessment of Risk States (EARS) mobile-phone application and some related EARS tools. This intellectual property was developed as part of his research at the University of Oregon’s Center for Digital Mental Health (CDMH).

Related Articles

See all News & Views

- Human behaviour

How ‘green’ electricity from wood harms the planet — and people

News Feature 20 AUG 24

The science of protests: how to shape public opinion and swing votes

News Feature 26 JUN 24

‘It can feel like there’s no way out’ — political scientists face pushback on their work

News Feature 19 JUN 24

Found: a brain-wiring pattern linked to depression

News 04 SEP 24

Substrate binding and inhibition mechanism of norepinephrine transporter

Article 14 AUG 24

MDMA therapy for PTSD rejected by FDA panel

News 05 JUN 24

How to change people’s minds about climate change: what the science says

News 06 SEP 24

Loss of plasticity in deep continual learning

Article 21 AUG 24

Are brains rewired for caring during pregnancy? Why the jury’s out

Correspondence 20 AUG 24

Tenure-Track Faculty Positions at the rank of Assistant Professor

Nashville, Tennessee

Vanderbilt University

Faculty Positions in Biology and Biological Engineering: Caltech, Pasadena, CA, United States

The Division of Biology and Biological Engineering (BBE) at Caltech is seeking new faculty in the area of Molecular Cell Biology.

Pasadena, California

California Institute of Technology (Caltech)

Assistant Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology

We seek applications for a tenure-track faculty position in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology.

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Harvard University - Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher - Developmental Biology of Medulloblastoma (Paul Northcott Lab)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Listen to the essay, as read by Antero Garcia, associate professor in the Graduate School of Education.

As a professor of education and a former public school teacher, I’ve seen digital tools change lives in schools.

I’ve documented the ways mobile technology like phones can transform student engagement in my own classroom.

I’ve explored how digital tools might network powerful civic learning and dialogue for classrooms across the country – elements of education that are crucial for sustaining our democracy today.

And, like everyone, I’ve witnessed digital technologies make schooling safer in the midst of a global pandemic. Zoom and Google Classroom, for instance, allowed many students to attend classrooms virtually during a period when it was not feasible to meet in person.

So I want to tell you that I think technologies are changing education for the better and that we need to invest more in them – but I just can’t.

Given the substantial amount of scholarly time I’ve invested in documenting the life-changing possibilities of digital technologies, it gives me no pleasure to suggest that these tools might be slowly poisoning us. Despite their purported and transformational value, I’ve been wondering if our investment in educational technology might in fact be making our schools worse.

Let me explain.

When I was a classroom teacher, I loved relying on the latest tools to create impressive and immersive experiences for my students. We would utilize technology to create class films, produce social media profiles for the Janie Crawfords, the Holden Caulfields, and other literary characters we studied, and find playful ways to digitally share our understanding of the ideas we studied in our classrooms.

As a teacher, technology was a way to build on students’ interests in pop culture and the world around them. This was exciting to me.

But I’ve continued to understand that the aspects of technology I loved weren’t actually about technology at all – they were about creating authentic learning experiences with young people. At the heart of these digital explorations were my relationships with students and the trust we built together.

“Part of why I’ve grown so skeptical about this current digital revolution is because of how these tools reshape students’ bodies and their relation to the world around them.”

I do see promise in the suite of digital tools that are available in classrooms today. But my research focus on platforms – digital spaces like Amazon, Netflix, and Google that reshape how users interact in online environments – suggests that when we focus on the trees of individual tools, we ignore the larger forest of social and cognitive challenges.

Most people encounter platforms every day in their online social lives. From the few online retail stores where we buy groceries to the small handful of sites that stream our favorite shows and media content, platforms have narrowed how we use the internet today to a small collection of Silicon Valley behemoths. Our social media activities, too, are limited to one or two sites where we check on the updates, photos, and looped videos of friends and loved ones.

These platforms restrict our online and offline lives to a relatively small number of companies and spaces – we communicate with a finite set of tools and consume a set of media that is often algorithmically suggested. This centralization of internet – a trend decades in the making – makes me very uneasy.

From willfully hiding the negative effects of social media use for vulnerable populations to creating tools that reinforce racial bias, today’s platforms are causing harm and sowing disinformation for young people and adults alike. The deluge of difficult ethical and pedagogical questions around these tools are not being broached in any meaningful way in schools – even adults aren’t sure how to manage their online lives.

You might ask, “What does this have to do with education?” Platforms are also a large part of how modern schools operate. From classroom management software to attendance tracking to the online tools that allowed students to meet safely during the pandemic, platforms guide nearly every student interaction in schools today. But districts are utilizing these tools without considering the wider spectrum of changes that they have incurred alongside them.

Antero Garcia, associate professor of education (Image credit: Courtesy Antero Garcia)

For example, it might seem helpful for a school to use a management tool like Classroom Dojo (a digital platform that can offer parents ways to interact with and receive updates from their family’s teacher) or software that tracks student reading and development like Accelerated Reader for day-to-day needs. However, these tools limit what assessment looks like and penalize students based on flawed interpretations of learning.

Another problem with platforms is that they, by necessity, amass large swaths of data. Myriad forms of educational technology exist – from virtual reality headsets to e-readers to the small sensors on student ID cards that can track when students enter schools. And all of this student data is being funneled out of schools and into the virtual black boxes of company databases.

Part of why I’ve grown so skeptical about this current digital revolution is because of how these tools reshape students’ bodies and their relation to the world around them. Young people are not viewed as complete human beings but as boxes checked for attendance, for meeting academic progress metrics, or for confirming their location within a school building. Nearly every action that students perform in schools – whether it’s logging onto devices, accessing buildings, or sharing content through their private online lives – is noticed and recorded. Children in schools have become disembodied from their minds and their hearts. Thus, one of the greatest and implicit lessons that kids learn in schools today is that they must sacrifice their privacy in order to participate in conventional, civic society.

The pandemic has only made the situation worse. At its beginnings, some schools relied on software to track students’ eye movements, ostensibly ensuring that kids were paying attention to the tasks at hand. Similarly, many schools required students to keep their cameras on during class time for similar purposes. These might be seen as in the best interests of students and their academic growth, but such practices are part of a larger (and usually more invisible) process of normalizing surveillance in the lives of youth today.

I am not suggesting that we completely reject all of the tools at our disposal – but I am urging for more caution. Even the seemingly benign resources we might use in our classrooms today come with tradeoffs. Every Wi-Fi-connected, “smart” device utilized in schools is an investment in time, money, and expertise in technology over teachers and the teaching profession.

Our focus on fixing or saving schools via digital tools assumes that the benefits and convenience that these invisible platforms offer are worth it.

But my ongoing exploration of how platforms reduce students to quantifiable data suggests that we are removing the innovation and imagination of students and teachers in the process.

Antero Garcia is associate professor of education in the Graduate School of Education .

In Their Own Words is a collaboration between the Stanford Public Humanities Initiative and Stanford University Communications.

If you’re a Stanford faculty member (in any discipline or school) who is interested in writing an essay for this series, please reach out to Natalie Jabbar at [email protected] .

September 11, 2018

Are Digital Devices Altering Our Brains?

Some say our gadgets and computers can help improve intelligence. Others say they make us stupid and violent. Which is it?

By Elena Pasquinelli

Do video games make people more aggressive, or are they beneficial—improving certain abilities, such as reaction time? Probably a bit of both, according to recent research, although any benefits are modest.

John Lund Getty Images

Ten years ago technology writer Nicholas Carr published an article in the Atlantic entitled “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” He strongly suspected the answer was “yes.” Himself less and less able to focus, remember things or absorb more than a few pages of text, he accused the Internet of radically changing people’s brains. And that is just one of the grievances leveled against the Internet and at the various devices we use to access it–including cell phones, tablets, game consoles and laptops. Often the complaints target video games that involve fighting or war, arguing that they cause players to become violent.

But digital devices also have fervent defenders—in particular the promoters of brain-training games, who claim that their offerings can help improve attention, memory and reflexes. Who, if anyone, is right?

The answer is less straightforward than you might think. Take Carr’s accusation. As evidence, he quoted findings of neuroscientists who showed that the brain is more plastic than previously understood. In other words, it has the ability to reprogram itself over time, which could account for the Internet’s effect on it. Yet in a 2010 opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times, psychologists Christopher Chabris, then at Union College, and Daniel J. Simons of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign rebutted Carr’s view: “There is simply no experimental evidence to show that living with new technologies fundamentally changes brain organization in a way that affects one’s ability to focus,” they wrote. And the debate goes on.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Case for Stupidity

Where does the idea that we are becoming “stupid” come from? It derives in part from the knowledge that digital devices capture our attention. A message from a friend, an anecdote shared on social networks or a sales promotion on an online site can act like a treat for the human brain. The desire for such “treats” can draw us to our screens repeatedly and away from other things we should be concentrating on.

People may feel overwhelmed by the constant input, but some believe they have become multitaskers: they imagine they can continually toggle back and forth between Twitter and work, even while driving, without losing an ounce of efficiency. But a body of research confirms that this impression is an illusion. When individuals try to do two or more things at once that require their attention, their performance suffers. Moreover, in 2013 Stéphane Amato, then at Aix-Marseille University in France, and his colleagues showed that surfing Web pages makes people susceptible to a form of cognitive bias known as the primacy effect: they weight the first few pieces of information they see more heavily than the rest.

Training does not improve the ability to multitask. In 2009 Eyal Ophir, then at Stanford University, and his colleagues discovered that multitasking on the Internet paradoxically makes users less effective at switching from one task to another. They are less able to allocate their attention and are too vulnerable to distractions. Consequently, even members of the “digital native” generation are unlikely to develop the cognitive control needed to divide their time between several tasks or to instantly switch from one activity to another. In other words, digital multitasking does little more than produce a dangerous illusion of competence.

The good news is that you do not need to rewire your brain to preserve your attention span. You can help yourself by thinking about what distracts you most and by developing strategies to immunize yourself against those distractions. And you will need to exercise some self-control. Can’t resist Facebook notifications? Turn them off while you’re working. Tempted to play a little video game? Don’t leave your device where you can see it or within easy reach.

Evidence for Aggression

What about the charge that video games increase aggression? Multiple reports support this view. In a 2015 review of published studies, the American Psychological Association concluded that playing violent video games accentuates aggressive thoughts, feelings and behavior while diminishing empathy for victims. The conclusion comes both from laboratory research and from tracking populations of online gamers. In the case of the gamers, the more they played violent games, the more aggressive their behavior was.

The aggression research suffers from several limitations, however. For example, lab studies measure aggressiveness by offering participants the chance to inflict a punishment, such as a dose of very hot sauce to swallow—actions that are hardly representative of real life. Outside the lab, participants would probably give more consideration to the harmful nature of their actions. And studies of gamers struggle to make sense of causality: Do video games make people more violent, or do people with a fundamentally aggressive temperament tend to play video games?

Thus, more research is needed, and it will require a combination of different methods. Although the findings so far are preliminary, researchers tend to agree that some caution is in order, beginning with moderation and variety: an hour here and there spent playing fighting games is unlikely to turn you into a brainless psychopath, but it makes sense to avoid spending entire days at it.

Gaming for Better Brains?

On the benefit side of the equation, a number of studies claim that video games can improve reaction time, attention span and working memory. Action games, which are dynamic and engaging, may be particularly effective: immersed in a captivating environment, players learn to react quickly, focus on relevant information and remember. In 2014, for example, Kara Blacker of Johns Hopkins University and her colleagues studied the impact games in the Call of Duty series—in which players control soldiers—on visual working memory (short-term memory). The researchers found that 30 hours of playing improved this capacity.

The assessment consisted of asking participants a number of times whether a group of four to six colored squares was identical to another group, presented two minutes earlier. Once again, however, this situation is far from real life. Moreover, the extent to which players “transfer” their learning to everyday activities is debatable.

This issue of skill transfer is also a major challenge for the brain-training industry, which has been growing since the 2000s. These companies are generally very good at promoting themselves and assert that engaging in various exercises and computer games for a few minutes a day can improve memory, attention span and reaction time.

Posit Science, which offers the BrainHQ series of brain training and assessment, is one such company. Its tools include UFOV (for “useful field of view). In one version of a UFOV-based game, a car and a road sign appear on a screen. Then another car appears. The player clicks on the original car and also clicks on where the road sign appeared. By having groups of objects scroll faster and faster, the activity is supposed to improve reaction time.

The company’s Web site touts user testimonials and says its customers report that BrainHQ “has done everything from improving their bowling game, to enabling them to get a job, to reviving their creativity, to making them feel more confident about their future.” Findings from research, however, are less clear-cut. On one hand, Posit Science cites the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Elderly (ACTIVE) Study to claim that UFOV training can improve overall reaction time in elderly players and reduce the risk that they will cause car crashes by almost 50 percent. But in a 2016 analysis of research on brain-training programs, Simons and his colleagues are far less laudatory. The paper, which includes an in-depth analysis of the ACTIVE study, says that the overall risk of having an accident—the most relevant criterion—decreased very little. Several reviews of the scientific literature come to much the same conclusion: brain-training products enhance performance on tasks that are trained directly, but the transfer is often weak.

Dr. Kawashima’s Brain Traininggame, released by Nintendo in the mid-2000s, provides another example of contrary results. In addition to attention and memory exercises, this game has a player do calculations. Does the program improve overall arithmetic skills? No, according to work done in 2012 by Siné McDougall and Becky House, both at Bournemouth University in England on a group of seniors. A year earlier, though, Scottish psychologists David Miller and Derek Robertson found that the game did increase how fast children could calculate.

Overall then, the results from studies are mixed. The benefits need to be evaluated better, and many questions need answering, such as how long an intervention should last and at what ages might it be effective. The answers may depend on the specific interventions being considered.

No Explosive Growth in Capacity

Any cognitive improvements from brain-training games probably will be marginal rather than an “explosion” of human mental capacities. Indeed, the measured benefits are much weaker and ephemeral than the benefits obtained through traditional techniques. For remembering things, for example, rather than training your recall with abstract tasks that have little bearing on reality, try testing your memory regularly and making the information as meaningful to your own life as possible: If you memorize a shopping list, ask yourself what recipe you are buying the ingredients for and for which day’s dinner. Unlike brain-training games, this kind of approach involves taking some initiative and makes you think about what you know.

Exercising our cognitive capacities is important to combating another modern hazard: the proliferation of fake news on social networks. In the same way that digital devices accentuate our tendency to become distracted, fake news exploits our natural inclination to believe what suits us. The solution to both challenges is education: more than ever, young people must be taught to develop their concentration, self-control and critical-thinking skills.

Elena Pasquinelli is a project manager at La Main à la Pâte Foundation, which works to improve science instruction in higher education, and an associate member of the Jean Nicod Institute, a cognitive science laboratory in Paris.

Home — Essay Samples — Information Science and Technology — Digital Era — Digital Devices And Well-Being

Digital Devices and Well-being

- Categories: Digital Era

About this sample

Words: 849 |

Published: Sep 19, 2019

Words: 849 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Works Cited

- Davoudi, S., & Curtis, S. (2018). Well-being in the digital age: A literature review. Future Cities and Environment, 4(1), 1-12.

- Demirci, K., Akgönül, M., & Akpinar, A. (2015). Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(2), 85-92.

- Gao, F., Luo, T., & Zhang, K. (2018). The impact of smartphone dependency on the perceived need for mobile phones in college students: Implications for behavioral intervention. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 578.

- Griffiths, M. D., & Kuss, D. J. (2011). Adolescent social networking: Should parents and teachers be worried? Education and Health, 29(3), 23-25.

- Johnson, R. E., & Spector, P. E. (2007). Service with a smile: Do emotional intelligence, gender, and autonomy moderate the emotional labor process? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(4), 319-333.

- Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 343-350.

- Lin, L. Y., Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Radovic, A., Miller, E., Colditz, J. B., ... & Primack, B. A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 323-331.

- Rozgonjuk, D., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2020). Comparing digital behavior measures and psychopathological symptoms among adolescents and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Computers in Human Behavior, 114, 106524.

- Schilhab, T. S. S., & Moeslund, T. B. (2017). The digital Danish childcare system: Stakeholder views on childcare apps. Early Child Development and Care, 187(12), 1859-1873.

- Thomée, S., Härenstam, A., & Hagberg, M. (2011). Mobile phone use and stress, sleep disturbances, and symptoms of depression among young adults: A prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 66.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Information Science and Technology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 703 words

3 pages / 1226 words

1 pages / 598 words

4 pages / 1815 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Digital Era

In an era defined by interconnectedness and virtual interactions, the question "Who am I in the digital world?" takes on new dimensions. As we navigate the complexities of online spaces, social media platforms, and digital [...]

The question of whether students should have limited access to the internet is a complex and timely one, given the pervasive role of technology in education. While the internet offers a wealth of information and resources, [...]

Pallasmaa J, Mallgrave HF, Arbib M. Architecture and Neuroscience. Tidwell P, editor. Finland: Tapio Wirkkala Rut Bryk Foundation; 2015.Colomina B, Wigley M. Are we human? notes on an archaeology of design. Netherlands: Lars [...]

The provision of free internet access is a topic of growing importance in our increasingly digital society. The internet has transformed the way we communicate, access information, and engage with the world. However, access to [...]

"Is digital transformation making its presence felt? Surely, if one goes by the contribution that only apps have been making to our national income. Data suggests that in 2015-16, apps have contributed 1.4 lakh crore to our GDP. [...]

Not since the arrival of the camera has something come along to change the style of art making's possibilities on such a grand scale as digital art. Digital art captures an artistic work or practice that uses any form of digital [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Overuse of Digital Technologies: Human Weaknesses, Design Strategies and Ethical Concerns

- Research Article

- Published: 08 July 2021

- Volume 34 , pages 1409–1427, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Marco Fasoli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6176-8257 1

2233 Accesses

13 Citations

280 Altmetric

38 Mentions

Explore all metrics

This is an interdisciplinary article providing an account of a phenomenon that is quite widespread but has been thus far mostly neglected by scholars: the overuse of digital technologies. Digital overuse (DO) can be defined as a usage of digital technologies that subjects perceive as dissatisfactory and non-meaningful a posteriori. DO has often been implicitly conceived as one of the main obstacle to so-called digital well-being . The article is structured in two parts. The first provides a definition of the phenomenon and a brief review of the explanations provided by various disciplines, in particular psychology and the evolutionary and behavioural sciences. Specifically, the article distinguishes between the endogenous and exogenous factors underlying digital overuse, that is between causes that seem to be intrinsic to digital technologies, and design techniques intentionally aimed at nudging users towards this behaviour. The second part is devoted to a discussion of the ethical concerns surrounding the phenomenon of the overuse of digital technologies, and how it may be possible to reduce such overuse among users.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital Humanism: Navigating the Tensions Ahead

The Road Less Taken: Pathways to Ethical and Responsible Technologies

Ethics Issues in Digital Methods Research

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Medical Ethics

I thank a reviewer for signalling this point.

Ainslie, G., & George, A. (2001). Breakdown of will . Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Ala-Mutka, K., Punie, Y., & Redecker, C. (2008). Digital competence for lifelong learning . Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS), European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Technical Note: JRC, 48708 , 271–282.

Angner, E. (2010). Subjective well-being. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39 (3), 361–368.

Baethge, A., & Rigotti, T. (2013). Interruptions to workflow: Their relationship with irritation and satisfaction with performance, and the mediating roles of time pressure and mental demands. Work & Stress, 27 (1), 43–63.

Bartsch, A., & Oliver, M. B. (2016). Appreciation of meaningful entertainment experiences and eudaimonic wellbeing. The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects , 98–110.

Beyens, I., Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 64 , 1–8.

Bianchi, M. (2007). If happiness is so important, why do we know so little about it (pp. 127–150). Edward Elgar.

Brey, P. (2015). Design for the value of human well-being. Handbook of ethics, values, and technological design: Sources, theory, values and application domains , 365–382.

Burr, C., & Floridi, L. (2020). Ethics of digital well-being . Springer.

Burr, C., Cristianini, N., & Ladyman, J. (2018). An analysis of the interaction between intelligent software agents and human users. Minds and Machines, 28 (4), 735–774.

Calvo, R. A., & Peters, D. (2014). Positive computing: Technology for wellbeing and human potential . MIT Press.

Calvo, R. A., Peters, D., Vold, K., & Ryan, R. M. (2020). Supporting human autonomy in AI systems: A framework for ethical enquiry. In Ethics of Digital Well-Being (pp. 31–54). Springer.

Calvo, R. A., Peters, D., & Cave, S. (2020b). Advancing impact assessment for intelligent systems. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2 (2), 89–91.

European Parliament and the Council (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union , L394.

Davidow, B. (2013). Skinner marketing: We’re the rats, and Facebook likes are the reward. The Atlantic , 10.

Davis, H., & McLeod, S. L. (2003). Why humans value sensational news: An evolutionary perspective. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24 (3), 208–216.

Dennis, M. J. (2021). Towards a theory of digital well-being: Reimagining online life after lockdown. Science and Engineering Ethics, 27 (3), 1–19.

Dunbar, R. I. (2004). Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Review of General Psychology, 8 (2), 100.

Elster, J., & Jon, E. (2000). Ulysses unbound: Studies in rationality, precommitment, and constraints . Cambridge University Press.

Entertainment Software Association. (2014). Games: Improving the economy. Entertainment Software Association , 4 .

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked: How to build habit-forming products . Penguin.

Fasoli, M. (2018). Super artifacts: Personal devices as intrinsically multifunctional, meta-representational artifacts with a highly variable structure. Minds and Machines, 28 (3), 589–604.

Ferster, C. B., & Skinner, B. F. (1957). Schedules of reinforcement . Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Fogg, B. J., Cueller, G., & Danielson, D. (2007). Motivating, influencing, and persuading users: An introduction to captology. In The human-computer interaction handbook (pp. 159–172). CRC Press.

Friedman, B. (1996). Value-sensitive design. Interactions, 3 (6), 16–23.

Gazzaley, A., & Rosen, L. D. (2016). The distracted mind: Ancient brains in a high-tech world . Mit Press.

Greene, J. A., Seung, B. Y., & Copeland, D. Z. (2014). Measuring critical components of digital literacy and their relationships with learning. Computers & Education, 76 , 55–69.

Gui, M., Fasoli, M., & Carradore, R. (2017). “Digital well-being”. Developing a new theoretical tool for media literacy research. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 9 (1).

Gui, M., & Büchi, M. (2019). From use to overuse: Digital inequality in the age of communication abundance. Social Science Computer Review, 0894439319851163.

Gui, M., Gerosa, T., Garavaglia, A., Petti, L., & Fasoli, M. (2018). Digital well-being. Validation of a digital media education programme in high schools. Report, Research Center on Quality of Life in the Digital Society .

Gui, M., Shanahan, J., & Tsay-Vogel, M. (2021). Theorizing inconsistent media selection in the digital environment. The Information Society , 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2021.1922565

Hanin, M. L. (2020). Theorizing digital distraction. Philosophy & Technology , 1–12.

Hefner, D., & Vorderer, P. (2016). Permanent connectedness and multitasking. The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects, 237.

Hertwig, R., & Grüne-Yanoff, T. (2017). Nudging and boosting: Steering or empowering good decisions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12 (6), 973–986.

Hills, T. T., Noguchi, T., & Gibbert, M. (2013). Information overload or search-amplified risk? Set size and order effects on decisions from experience. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20 (5), 1023–1031.

Hsee, C. K., & Hastie, R. (2006). Decision and experience: Why don’t we choose what makes us happy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10 (1), 31–37.

Huta, V. (2016). An overview of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being concepts. Handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects , 14–33.

Jachimowicz, J. M., Duncan, S., Weber, E. U., & Johnson, E. J. (2019). When and why defaults influence decisions: A meta-analysis of default effects. Behavioural Public Policy, 3 (2), 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.43

Article Google Scholar

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . Macmillan.

Klenk, M. (2020). Digital well-being and manipulation online. In C. Burr & L. Floridi (Eds.), Ethics of Digital Well-Being. Springer.

Kozyreva, A., Lewandowsky, S., & Hertwig, R. (2019). Citizens versus the internet: Confronting digital challenges with cognitive tools.

Lanzing, M. (2019). “Strongly recommended” revisiting decisional privacy to judge hypernudging in self-tracking technologies. Philosophy & Technology, 32 (3), 549–568.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping . Springer publishing company.

Lee, A. R., Son, S. M., & Kim, K. K. (2016). Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 55 , 51–61.

Lortie, C. L., & Guitton, M. J. (2013). Internet addiction assessment tools: Dimensional structure and methodological status. Addiction, 108 (7), 1207–1216.

Lukoff, K., Yu, C., Kientz, J., & Hiniker, A. (2018). What makes smartphone use meaningful or meaningless? Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2 (1), 1–26.

Meshi, D., Tamir, D. I., & Heekeren, H. R. (2015). The emerging neuroscience of social media. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19 (12), 771–782.

Mill, J. S. (1963). Collected works .

Miller, G. A. (1984). Informavores. The study of information: Interdisciplinary messages , 111–113.

Murray, J., Scott, H., Connolly, C., & Wells, A. (2018). The attention training technique improves children’s ability to delay gratification: A controlled comparison with progressive relaxation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 104 , 1–6.

Noggle, R. The ethics of manipulation. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition). URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/ethics-manipulation/ . Accessed Dec 2019

OFCOM (2016). The Communications Market Report. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/26826/cmr_uk_2016.pdf . Accessed Dec 2019

Peters, D., Calvo, R. A., & Ryan, R. M. (2018). Designing for motivation, engagement and wellbeing in digital experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 797.

Pinker, S. (2003). The language instinct: How the mind creates language . Penguin.

Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (4), 1841–1848.

Rahwan, I., Cebrian, M., Obradovich, N., Bongard, J., Bonnefon, J. F., Breazeal, C., … & Jennings, N. R. (2019). Machine behaviour. Nature , 568(7753), 477-486. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1138-y .

Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2016). Motivation for entertainment media and its eudaimonic aspects through the lens of self-determination theory. The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects , 34–48.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness . Guilford Publications.

Schüll, N. D. (2014). Addiction by design: Machine gambling in Las Vegas . Princeton University Press.

Seaver, N. (2018). Captivating algorithms: Recommender systems as traps. Journal of Material Culture , 1359183518820366.

Simon, H. A. (1990). Invariants of human behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 41 (1), 1–20.

Stanca, L., Gui, M., & Gallucci, M. (2013). Attracted but unsatisfied: The effects of sensational content on television consumption choices. Journal of Media Economics, 26 (2), 82–97.

Susser, D., Roessler, B., & Nissenbaum, H. (2018). Online manipulation: Hidden influences in a digital world. Georgetown Law Technology Review , Forthcoming.

Tamir, D. I., & Mitchell, J. P. (2012). Disclosing information about the self is intrinsically rewarding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (21), 8038–8043.

Toma, C. L. (2016). Taking the good with the bad. The Routledge handbook of media use and well-being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects , 170–182.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness . Penguin.

Turkle, S. (2017). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other . Hachette.

Van de Poel, I. (2012). 21 Can we design for well-being? The Good Life in a Technological Age, 17 , 295.

Van den Hoven, J., Vermaas, P. E., & Van de Poel, I. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of ethics, values, and technological design: Sources, theory, values and application domains . Springer.

Williams, J. (2018). Stand out of our light: Freedom and resistance in the attention economy . Cambridge University Press.

Wu, T. (2017). The attention merchants: The epic scramble to get inside our heads . Vintage.

Yeung, K. (2017). ‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a mode of regulation by design. Information, Communication & Society, 20 (1), 118–136.

Download references

The article was supported by the Italian project MOM “The Mark of the mental” PRIN 2020.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

IUSS Pavia, Piazza della Vittoria, 15, 27100, Pavia, PV, Italy

Marco Fasoli

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marco Fasoli .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fasoli, M. The Overuse of Digital Technologies: Human Weaknesses, Design Strategies and Ethical Concerns. Philos. Technol. 34 , 1409–1427 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00463-6

Download citation

Received : 01 December 2020

Accepted : 30 June 2021

Published : 08 July 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00463-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital technologies

- Overuse design

- Design ethics

- Technological manipulation

- Digital well-being

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Use and abuse of digital devices: influencing factors of child and adolescent neuropsychology.

Author Contributions

Conflicts of interest.

- Weinstein, A.; Lejoyeux, M. Internet Addiction or Excessive Internet Use. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2010 , 36 , 277–283. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y.; Yen, C.F.; Chen, C.S.; Chen, C.C. The Association between Internet Addiction and Psychiatric Disorder: A Review of the Literature. Eur. Psychiatry 2012 , 27 , 1–8. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Manago, A.M. Media and the Development of Identity. Emerg. Trends Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015 , 2015 , 1–14. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- La Barbera, D.; Caretti, V. Psicopatologia Delle Realtà Virtuali: Comunicazione, Identità e Relazione Nell’era Digitale ; Masson: London, UK, 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liew, J.; Chang, Y.P.; Kelly, L.; Yalvac, B. Self-Regulated and Social Emotional Learning in the Multitasking Generation Special Issue of Journal of Social Issues: Hate Crime View Project Project ABC-EAT View Project ; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Prensky, M. The Emerging Online Life of the Digital Native: What They Do Differently Because of Technology, and How They Do It. Recuper. El 2004 , 28 , 9–11. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parisi, L.; Ruberto, M.; Precenzano, F.; Filippo, T.D.; Russotto, C.; Maltese, A.; Salerno, M.; Roccella, M. The Quality of Life in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2016 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Goldberg, I. Internet addiction disorder. Psychol. Behav. 1996 , 3 , 403–412. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Internet Addiction: Does It Really Exist? In Psychology and the Internet: Intrapersonal, Interpersonal and Transpersonal Applications ; Gackenbach, J., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 61–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online Gaming Addiction in Children and Adolescents: A Review of Empirical Research. J. Behav. Addict 2012 , 1 , 3–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Haand, R.; Shuwang, Z. The Relationship between Social Media Addiction and Depression: A Quantitative Study among University Students in Khost, Afghanistan. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020 , 25 , 780–786. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kurniasih, N. Internet Addiction, Lifestyle or Mental Disorder? A Phenomenological Study on Social Media Addiction in Indonesia. KnE Soc. Sci. 2017 , 2017 , 135–144. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; van Driel, I.I.; Beyens, I. The Associations of Active and Passive Social Media Use with Well-Being: A Critical Scoping Review. New Media Soc. 2022 , 24 , 530–549. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baker, Z.G.; Krieger, H.; LeRoy, A.S. Fear of Missing out: Relationships with Depression, Mindfulness, and Physical Symptoms. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2016 , 2 , 275–282. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Adelhardt, Z.; Markus, S.; Eberle, T. Teenagers’ Reaction on the Long-Lasting Separation from Smartphones, Anxiety and Fear of Missing Out. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series ; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 212–216. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Parisi, L.; Salerno, M.; Maltese, A.; Tripi, G.; Romano, P.; Di Folco, A.; Di Filippo, T.; Messina, G.; Roccella, M. Emotional Intelligence and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome in Children: Preliminary Case-Control Study. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2017 , 33 , 485. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tuberquia, L.C.M.; Peláez, A.F.V. Fenómeno Del Vamping y El Impacto Que Genera Los Dispositivos Electrónicos En Los Jóvenes a Altas Horas de La Noche. Rev. Virtual Univ. 2021 , 16 , 163–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodríguez-García, A.-M.; Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J.; López-Belmonte, J. Nomophobia: An Individual’s Growing Fear of Being without a Smartphone—A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 580. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Notara, V.; Vagka, E.; Gnardellis, C.; Lagiou, A. The Emerging Phenomenon of Nomophobia in Young Adults: A Systematic Review Study. Addict. Health 2021 , 13 , 120. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Tamaki, S.; Angles, J.T. Hikikomori: Adolescence without End ; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kato, T.A.; Kanba, S.; Teo, A.R. Hikikomori: Multidimensional Understanding, Assessment, and Future International Perspectives. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019 , 73 , 427–440. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Costanza, C.; Vetri, L.; Carotenuto, M.; Roccella, M. Use and Abuse of Digital Devices: Influencing Factors of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychology. Clin. Pract. 2023 , 13 , 1331-1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13060119

Costanza C, Vetri L, Carotenuto M, Roccella M. Use and Abuse of Digital Devices: Influencing Factors of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychology. Clinics and Practice . 2023; 13(6):1331-1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13060119

Costanza, Carola, Luigi Vetri, Marco Carotenuto, and Michele Roccella. 2023. "Use and Abuse of Digital Devices: Influencing Factors of Child and Adolescent Neuropsychology" Clinics and Practice 13, no. 6: 1331-1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract13060119

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Addictive use of digital devices in young children: Associations with delay discounting, self-control and academic performance

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Business and Economics, Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany

- Tim Schulz van Endert

- Published: June 22, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253058

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The use of smartphones, tablets and laptops/PCs has become ingrained in adults’ and increasingly in children’s lives, which has sparked a debate about the risk of addiction to digital devices. Previous research has linked specific use of digital devices (e.g. online gaming, smartphone screen time) with impulsive behavior in the context of intertemporal choice among adolescents and adults. However, not much is known about children’s addictive behavior towards digital devices and its relationship to personality factors and academic performance. This study investigated the associations between addictive use of digital devices, self-reported usage duration, delay discounting, self-control and academic success in children aged 10 to 13. Addictive use of digital devices was positively related to delay discounting, but self-control confounded the relationship between the two variables. Furthermore, self-control and self-reported usage duration but not the degree of addictive use predicted the most recent grade average. These findings indicate that children’s problematic behavior towards digital devices compares to other maladaptive behaviors (e.g. substance abuse, pathological gambling) in terms of impulsive choice and point towards the key role self-control seems to play in lowering a potential risk of digital addiction.

Citation: Schulz van Endert T (2021) Addictive use of digital devices in young children: Associations with delay discounting, self-control and academic performance. PLoS ONE 16(6): e0253058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253058

Editor: Baogui Xin, Shandong University of Science and Technology, CHINA

Received: April 8, 2021; Accepted: May 27, 2021; Published: June 22, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Tim Schulz van Endert. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

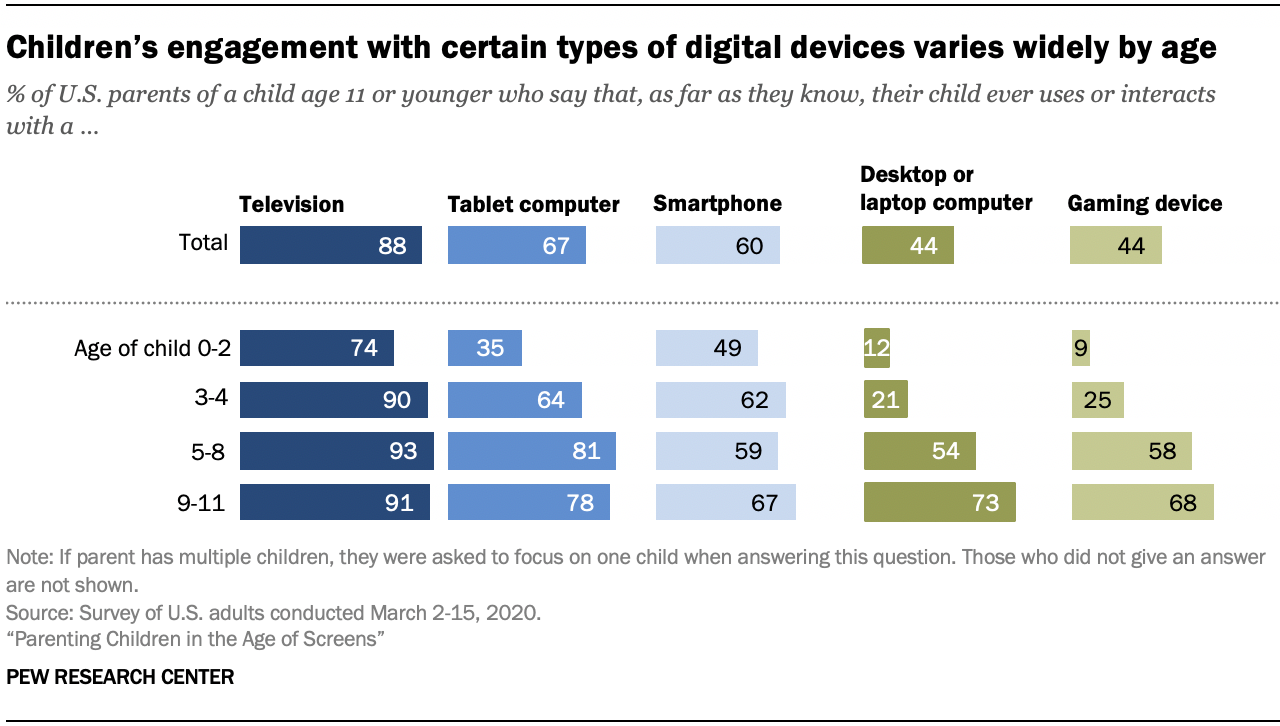

Digital devices, such as smartphones, tablets and laptops, have become an integral part in the lives of the majority of people around the world. Recent surveys e.g. in the US estimate that 81% of adults own a smartphone, 74% own a laptop and 52% own a tablet [ 1 ]. Notably, not only adults but also children have been increasingly surrounded by digital devices; a report from the UK states that in 2019 more than two thirds of 5- to 16-year-olds owned a smartphone and that 80% of 7- to 16-year-olds had internet access in their own room [ 2 ]. The same report also estimates that children’s average time spent online is 3.4 hours per day, with the main activities being watching videos (e.g. on YouTube and TikTok), using social media (e.g. Instagram and Snapchat) or gaming (e.g. Fortnite or Minecraft). These numbers have seen an unprecedented increase since the COVID-19 pandemic, which has, to a large extent, forced children to remain home, receive online schooling and interact with friends digitally. While the effects of these measures vary from country to country, a 163% increase in daily screen time during the first lockdown in Germany is not an unusual occurrence as observed by Schmidt et al. [ 3 ].

These developments have added momentum to the debate about the addiction potential of digital devices—especially for children, who are particularly at risk of developing addictive behaviors [ 4 ]. Evidence of negative implications of excessive digital device use, such as stress [ 5 ], sleep disturbance [ 6 ] or poor academic performance [ 7 ], has accumulated in recent years. However, researchers have not yet agreed on a standardized definition of digital addiction, which clearly separates it from other, possibly underlying disorders [ 8 ]. For one aspect of problematic use of digital devices, namely Internet Gaming Disorder, existing research has matured to stage where it suggests a potential future inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), as an officially diagnosable condition. Other aspects, such as smartphone addiction, are less mature and the literature has so far only identified a significant overlap between addiction to smartphones and substance-related disorders defined in the DSM-5 [ 9 , 10 ]. One area of research, which seeks to explore overall addiction to digital devices, encompassing various media (e.g. smartphones, tablets and laptops/PCs) and activities (e.g. gaming, social media), seems promising but is still in its infancy [ 11 ]. Unlike the aforementioned strands of literature, research on overall digital addiction takes into account the newly emerged usage behavior of performing a multitude of activities on and across several different digital devices (e.g. sending WhatsApp messages on a smartphone, playing games on a tablet and watching movies on a laptop). This may promote a degree of consolidation of the large number of concepts of technology addiction and their corresponding scales, which have emerged over the years but have recently been shown to be highly similar on a dimensional level [ 12 ].

A scale assessing digital addiction particularly among young children was recently introduced [ 11 ]. The Digital Addiction Scale for Children (DASC) measures to which degree children’s use of smartphones, tablets and laptops/PCs negatively affects their educational, psychological, social and physical well-being. To account for the ongoing debate about a standardized definition of digital addiction and the corresponding lack of a firm diagnosis, throughout this paper the softer formulation “addictive use of digital devices” is used rather than “digital addiction” when referring to children’s use of digital devices with adverse consequences. To further our understanding of this behavioral pattern and enable possible future intervention, the scale needs to be investigated in connection with personality factors, which may contribute to problematic behavior towards digital devices [ 13 ].

In this context, delay discounting, i.e. the tendency to discount rewards as a function of the delay of their delivery, suggests itself as an avenue for research. This cognitive process underlies human and non-human animals’ preference for smaller, immediate rewards over larger, delayed rewards and is often used as a measure of impulsivity [ 14 ]. Delay discounting has been studied extensively in the past decades, mostly by means of intertemporal choice problems, in which participants are faced with the tradeoff between the amount and the delay of a reward (e.g. choosing between 100€ today or 150€ in one month). Several models seeking to capture behavior have emerged, with hyperbolic discounting providing the best fit for most empirical data [ 15 ]. Its equation V = A / (1+kD) (V is the present value of the future reward, A is the reward amount and D is the delay to the reward) contains one free parameter k, which represents an individual’s discount rate. The lower this discounting parameter, the less the individual devalues future rewards and is therefore relatively less impulsive than a person with a higher discount rate. Due to the relative temporal stability of individuals’ discount rates, delay discounting may be seen as a trait variable [ 16 ]. Also, a plethora of studies has shown an association between delay discounting and a variety of maladaptive behaviors, such as substance abuse [ 17 ], smoking [ 18 ] and pathological gambling [ 19 , 20 ] or overeating [ 21 ]. In these studies, addicted individuals discounted future rewards more steeply than control subjects, which makes delay discounting a reliable indicator for various kinds of addictions [ 22 ]. Given that the discounting of future rewards is not only related to substance-based but also to behavioral addictions, this raises the question if delay discounting is also associated with addictive use of digital devices. Past studies have only been able to show relationships between delay discounting and single aspects of digital use, such as internet gaming [ 23 ] or smartphone screen time [ 24 ]. In addition, the samples studied consisted of adolescents or adults, despite regular use of digital devices already starting in childhood [ 2 ].

Furthermore, researchers agree on the key role of self-control in the development [ 25 ] and treatment [ 26 ] of addictive behaviors. On the one hand, a decreased ability to regulate thoughts and emotions contributes to risk-taking behavior, such as initiating use of addictive drugs, which is a common phenomenon in adolescents [ 27 ]. On the other hand, impaired self-control is a key symptom of addicted individuals, i.e. the inability to stop engaging in addictive behavior despite a willingness to do so. Thus, behavioral training to strengthen control functions has been proposed as an effective approach to reduce addiction [ 28 ]. Additionally, prominent models of decision-making have also highlighted self-control as a mechanism underlying delay discounting [ 22 , 29 ]. According to these accounts, exertion of self-control suppresses the impulse of choosing a smaller, immediate reward and biases choice behavior towards the larger, delayed reward. However, the interrelationships between delay discounting, addictive use of digital devices and self-control have yet to be explored.

Lastly, a number of studies have shown an association between various kinds of addictive behavior and poor academic performance [ 30 – 32 ]. Being distracted in the classroom or while studying, concentration lapses due to lack of sleep or missing classes and exams have been put forth as explanations for this finding. Given the novelty of the concept of digital addiction, the question whether the pattern suggested by the literature also holds in the context of addictive use of digital devices, particularly by young children, needs empirical investigation. This issue is of great importance as fundamental reading, writing and mathematics skills are taught at this stage. It is also relevant for the debate about increasingly integrating digital media in classroom activities and homework as part of the digitalization of schools. Therefore, this present study examines the following three hypotheses:

- H1: Delay discounting is positively correlated with children’s addictive use of digital devices

- H2: Self-control is negatively correlated with children’s addictive use of digital devices

- H3: Children’s addictive use of digital devices is negatively correlated with academic success

This study contributes to the literature by showing behavioral similarities between addictive use of digital devices and other problematic behaviors, by highlighting the central role that self-control seems to play in the context of digital addiction and by uncovering an intriguing pattern when comparing the relationships of problematic use vs. raw usage duration of digital devices with academic success.

Participants

75 children aged 10 to 13 (mean 11.3 years, 47% female) with no officially diagnosed mental disorders (e.g. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder) were recruited from a public elementary school in Berlin, Germany. The participants were 5 th and 6 th grade students and were selected for two reasons. On the one hand, participants needed to be able to understand the tasks and questionnaires employed in this study. On the other hand, this age represents a major crossroad for the children of Berlin; within the city’s school system, students graduate from elementary school after 6 th grade and progress to either high school (“Gymnasium”) or integrative secondary school (“Integrierte Sekundarschule”) depending on their academic performance (a German high school diploma provides eligibility to attend University, while students from Integrative Secondary School graduate after 9 th or 10 th grade in order to start an apprenticeship). This age group, prior to above-mentioned separation, thus had the positive side effect of implying a variety of academic skills as well as socio-economic backgrounds. Furthermore, the school’s headmaster affirmed that there was a significant diversity of ethnicities and nationalities among students and that no mental disorders existed in the observed classes. Parents (or guardians) of all participants were informed that participation was voluntary as well as anonymous and did not have an impact on their children’s grades. Roughly 15% of invited students chose not to participate in the study. Informed consent documents were signed before each study session.

Addictive use of digital devices.