SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Effects of covid-19-related school closures on student achievement-a systematic review.

- 1 Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany

- 2 Center for Educational Measurement, Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

The COVID-19 pandemic led to numerous governments deciding to close schools for several weeks in spring 2020. Empirical evidence on the impact of COVID-19-related school closures on academic achievement is only just emerging. The present work aimed to provide a first systematic overview of evidence-based studies on general and differential effects of COVID-19-related school closures in spring 2020 on student achievement in primary and secondary education. Results indicate a negative effect of school closures on student achievement, specifically in younger students and students from families with low socioeconomic status. Moreover, certain measures can be identified that might mitigate these negative effects. The findings are discussed in the context of their possible consequences for national educational policies when facing future school closures.

Introduction

In spring 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused severe disruption to everyday life around the world. As one of several measures taken to prevent the spread of the virus, many governments closed schools for several weeks or months. Although school closures are considered to be one of the most efficient interventions to curb the spread of the virus ( Haug et al., 2020 ), many educators and researchers raised concerns about the effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student academic achievement and learning inequalities. For instance, Woessmann (2020) estimated a negative effect of 0.10 SD on student achievement due to COVID-19-related school closures. Moreover, Haeck and Lefebvre (2020) estimated that socioeconomic achievement gaps would increase by up to 30%.

The negative effects of school closures due to summer vacation or natural disasters, and of absenteeism on student achievement are already well documented in the literature (for an overview see Kuhfeld et al., 2020a ). Less is known, however, about the impact of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement. The primary focus of the literature on COVID-19-related school closures to date was on the reception and use of digital learning technologies and remote learning ( Andrew et al., 2020 ; Grewenig et al., 2020 ; Maity et al., 2020 ; Pensiero et al., 2020 ; Blume et al., 2021 ). Moreover, the psychological impact of COVID-19-related school closures, the use of school counseling in connection with COVID-19 ( O'Connor, 2020 ; Xie et al., 2020 ; Ehrler et al., 2021 ; Gadermann et al., 2021 ; O'Sullivan et al., 2021 ), and the effects of the school closures on student motivation ( Zaccoletti et al., 2020 ; Smith et al., 2021 ) were investigated. Existing projections of the impact of COVID-19 on student achievement paint quite a bleak picture. A learning loss of up to 38 points on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 1 ) scale is estimated, which corresponds to an effect size (Cohen's d ) of 0.38 or 0.9 school years ( Azevedo et al., 2020 ; Kuhfeld et al., 2020a ; Wyse et al., 2020 ; Kaffenberger, 2021 ).

Thus, a year into the pandemic, it is a good time for a first stocktaking of the actual, evidence-based impact of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement. Consequently, the present work aimed to answer two research questions. First, what was the general effect of COVID-19-related school closures in spring 2020 on student achievement in primary and secondary education? Second, did school closures have differential effects on specific student groups?

The review is organized following the reporting guidelines of the PRISMA statement ( Page et al., 2021 ) and structured as follows. We first illustrate our systematic literature search, the inclusion criteria, the risk of bias assessment, and the synthesis of the relevant information from the studies selected. We then report the general and differential effects of the COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement, which are discussed in the context of their possible consequences for future national educational policies.

Literature Search

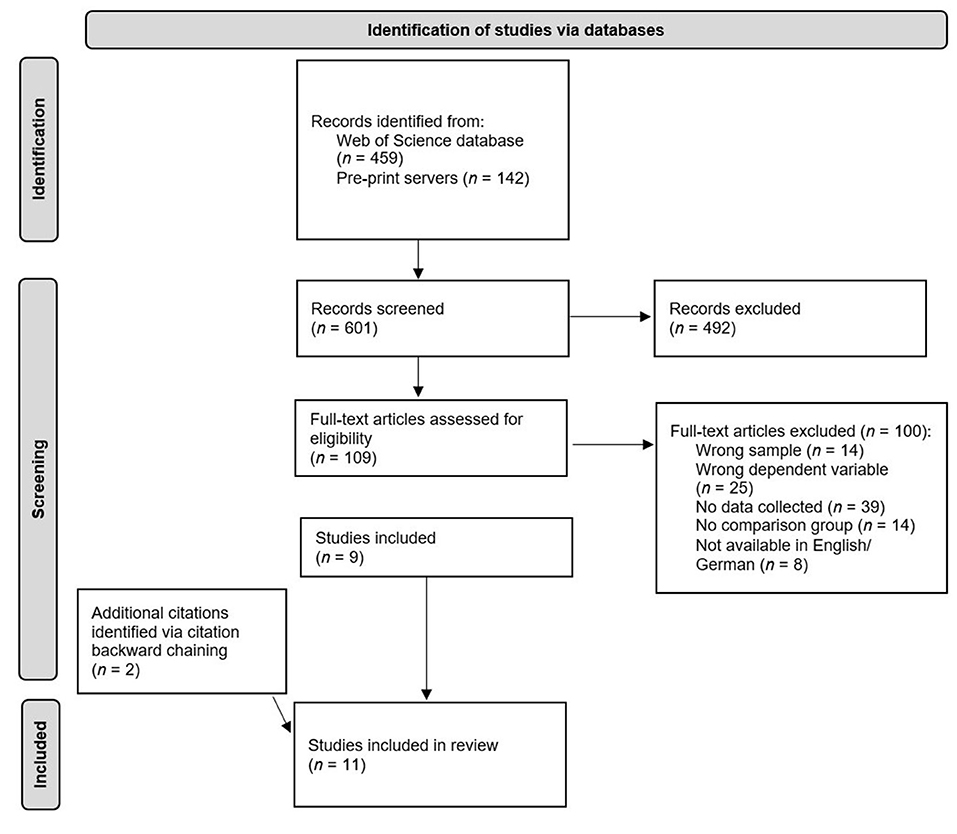

To identify relevant studies that investigated the effect of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement, we searched the Web of Science database for articles published between March 1, 2020 and April 30, 2021. We used the following keywords and search string: [Covid OR Corona OR “SARS-CoV-2” AND school AND learn* OR “test score” OR performance OR competenc* OR achievement OR grades]. The results were refined by using the following categories: education, educational research, economics, education scientific disciplines, psychology educational, psychology multidisciplinary, social sciences interdisciplinary, and education special. The indexes searched were SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, and IC. Because the COVID-19 pandemic was still ongoing at the time this review was written, and the field of research on the effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement is rapidly evolving, we additionally searched the preprint servers PsyArXiv, EdArXiv, and SocArXiv using the aforementioned keywords. With this initial literature search, we obtained 601 potentially relevant studies. After selecting relevant articles out of these studies, we used the backward reference searching method (i.e., examining the works cited in the selected articles) to identify additional potentially relevant studies. See Figure 1 for a PRISMA flowchart of the literature search process.

Figure 1 . PRISMA flowchart of the literature search and screening process.

Selection of Studies

The abstracts of the studies selected were carefully read by the authors, and further inclusion was decided based on the following initial criteria. The studies (1) had to have a clear focus on COVID-19-related school closures, they (2) had to focus on primary and secondary education, and they (3) had to have student achievement (or test scores) as the dependent variable. This initial selection left 109 studies for potential inclusion in the review. These studies were thoroughly read by the authors and two research assistants. We carefully assessed the quality of included studies and based the decision to include studies in the review on the following primary set of inclusion criteria: Studies were required (1) to have collected actual data prior to and during/after COVID-19-related school closures, and (2) to have applied statistical analyses and to report an effect size. This set of inclusion criteria was chosen in order to select studies that provided the aforementioned evidence-based insights. Thus, reviews or discussions on how COVID-19 affects educational processes were excluded. Likewise, exploratory analyses or simple surveys (where only percentages were reported) were also excluded. For example, Chadwick and McLoughlin (2021) investigated the impact of COVID-19 related school closures on student's science learning. However, they only questioned teachers on the impact of COVID-19 related school closures on teaching, learning, and assessment. Because the study did not meet the inclusion criteria of having collected actual data on student achievement, including a comparison of data prior to and during/after COVID-19-related school closures, and applying statistical analyses rather than solely reporting percentages, the study was excluded from the systematic review. Similarly, studies by Haeck and Lefebvre (2020) , Kaffenberger (2021) , and Kuhfeld et al. (2020a) were excluded from the systematic review because they reported predicted effects of COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement but did not collect actual data prior to and during/after COVID-19-related school closures.

To determine the degree of rater agreement on the selection of the studies, a randomly selected subset of 20 studies was evaluated by both the authors and the research assistants. Any remaining divergent evaluations were highlighted in the evaluation forms and subsequently discussed. The second selection procedure yielded nine studies that were suitable for inclusion in the review. Subsequently, a backward search of references within the nine selected studies yielded two additional studies, which were then also included in the review.

Risk of Bias Assessment

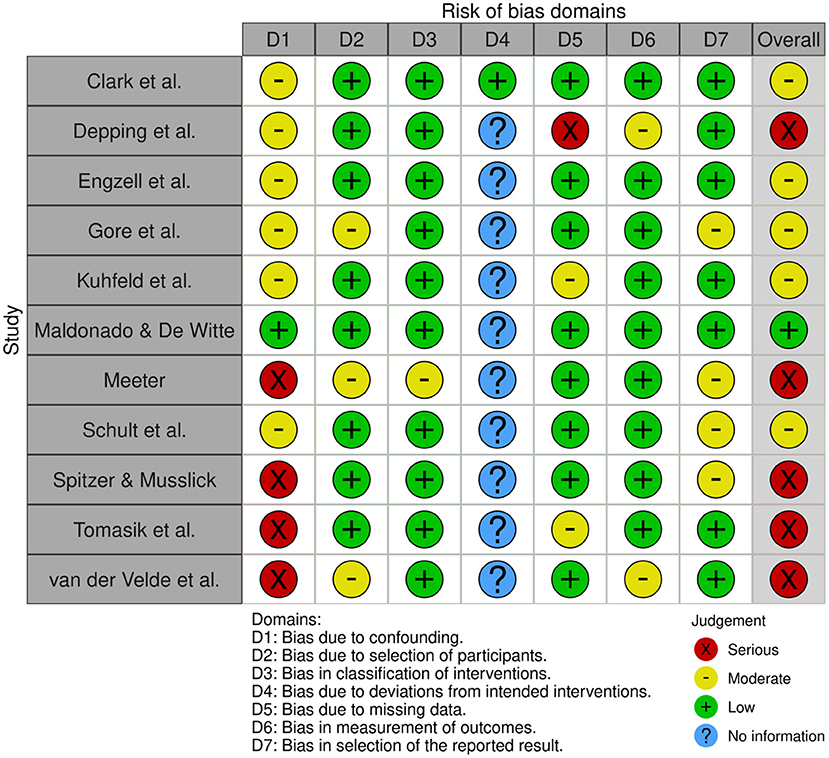

The Cochrane Risk Assessment of the included studies was conducted independently by the first and second author using the “Risk Of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions” tool (ROBINS-I; Sterne et al., 2016 ). The result of the risk assessment is summarized in Figure 2 . Taken together, the highest risk of bias is due to the lack of inclusion of potential confounding variables (Domain 1). Most studies, however, included at least a few relevant controls. Bias due to selection of participants was unlikely as the groups were formed naturally. Similarly, where applicable, interventions were classified correctly. Except for Clark et al. (2020) , no information could be obtained about deviations from intended interventions. This is because the COVID-19 related school closures were not intended interventions. Thus, although there is no information, the risk due to deviations from intended interventions was deemed low. Lastly, bias due to missing data, measurement of outcomes, or selection of reported results is unlikely, as most studies exhibited very small proportions of missing data (except Depping et al., 2021 ), and were highly transparent in their reporting of the results (except, partially, van der Velde et al., 2021 , who only report significant mean differences between groups in sufficient detail). Depping et al. (2021) , however, thoroughly discuss and provide convincing reasons for assuming that missing data does not substantially influence their results.

Figure 2 . Result of the cochrane risk of bias assessment.

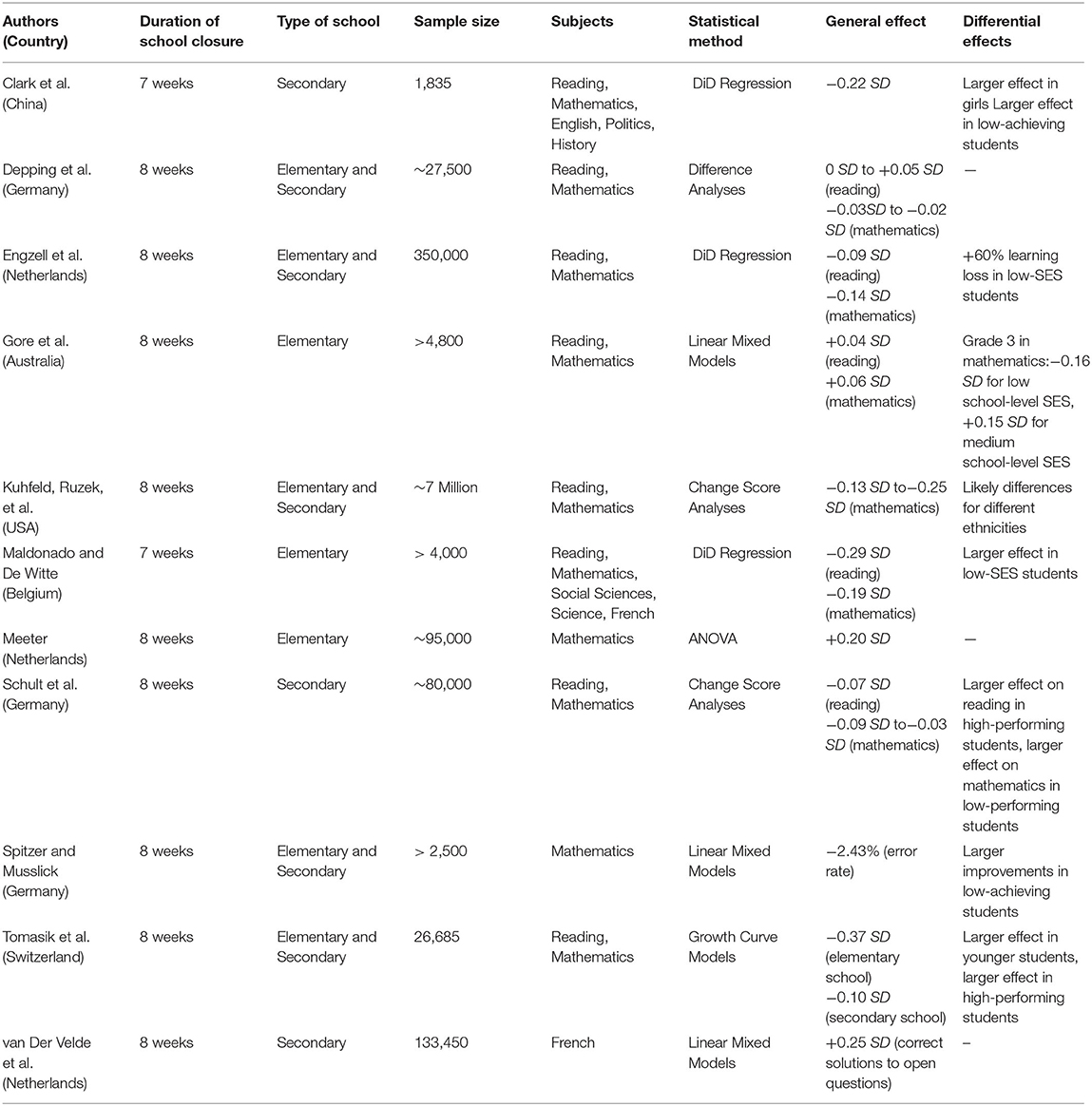

We synthesized the eleven studies by extracting the following information that was relevant for our research questions: (1) country, (2) duration of school closure, (3) sample description (type of school and sample size), (4) subjects for which student achievement was investigated, (5) statistical method, (6) general effects of the COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement, and (7) differential effects as reported by subgroup analyses (see Table 1 for a detailed list of the studies included). The focal piece of information was the reported general and differential effects. Where possible, general effects reported in different metrics (e.g., percentile scores), were converted to changes in SD . We then calculated the median of the reported effects, for the overall general effect, as well as for the general effect on reading and mathematics. In light of the relatively small number of studies, random- or even mixed-effects meta-analytic models were not feasible.

Table 1 . Descriptive criteria of studies included.

General Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement

The studies on the effect of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement selected for our review reported mixed findings, with effects ranging from−0.37 SD to +0.25 SD ( Mdn = −0.08 SD ). Most studies found negative effects of COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement. Seven studies reported a negative effect on mathematics ( Clark et al., 2020 ; Kuhfeld et al., 2020b ; Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 ; Tomasik et al., 2020 ; Depping et al., 2021 ; Engzell et al., 2021 ; Schult et al., 2021 ), five studies on reading ( Clark et al., 2020 ; Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 ; Tomasik et al., 2020 ; Engzell et al., 2021 ; Schult et al., 2021 ), and two studies on other subjects, such as science ( Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 ; Engzell et al., 2021 ). This is in line with expected learning losses due to COVID-19 related school closures and the assumption that, in spring 2020, the ad hoc implementation of online teaching gave students, teachers, schools, and parents little time to prepare for or adapt to measures of remote learning.

Three studies reported positive effects of COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement. Meeter (2021) and Spitzer and Musslick (2021) showed students to improve their mathematics achievement when learning with an online-learning software during the COVID-related school closures. Similarly, van der Velde et al. (2021) reported an increase in correct solutions on open questions within a French learning program. Interestingly, these three studies focused on online-learning software. Thus, the positive effects may be explained by the students under investigation being familiar working with the corresponding online-learning software prior to school closures. Hence, they did not have to adapt to a new learning environment when in-person teaching was interrupted due to COVID-19. Moreover, students increased the time using the online-learning software at home, were less distracted or experienced less time pressure in a home-schooling rather than classroom setting, or were presented with individualized assignments within the online program (see also Meeter, 2021 ; Spitzer and Musslick, 2021 ; van der Velde et al., 2021 ).

Additionally, two studies found positive effects on student achievement in mathematics and reading ( Gore et al., 2021 ), or in reading only ( Depping et al., 2021 ). This result might be accounted for by the achievement measurement being timed some months after school closures in both studies and the possibility of effective compensatory measures being implemented by teachers, schools, and local policy makers during this time to counteract learning losses, such as offering learning groups during summer vacation in parts of Germany ( Depping et al., 2021 ).

Even though the median for the effect on mathematics and reading is comparable when averaging above all studies ( d = −0.10 SD and−0.09 SD for mathematics and reading, respectively), some included studies found different effects for different subjects. On the one hand, reasons for finding larger learning losses in reading than in mathematics might be that “mathematics is easier to teach in distance learning, as it is simple to provide exercises and tests digitally or as worksheets” ( Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 , p. 13). As another explanation, many students might not speak the language in which they are tested in at home, hence, not benefitting much in their language skills during school closures (e.g., Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 ). On the other hand, reasons for finding larger learning losses in mathematics than in reading might be that students spent more time on reading during school closures and that supporting children in their reading skills might have been easier to realize for parents than supporting children in improving their competencies in mathematics (e.g., Depping et al., 2021 ; Schult et al., 2021 ).

Differential Effects on Groups of Students

The studies selected for our review reported three main differential effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement in different groups of students. First, the main finding was that younger children were more negatively affected in their learning than older children were (-0.37 SD vs.−0.10 SD ; Tomasik et al., 2020 ). Second, children from families with a low socioeconomic status (SES) were more affected than children from families with a high SES were ( Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 ; Engzell et al., 2021 ). In this context, one study reported an interaction between grade and SES, that is, for younger children from schools with low school-level SES, learning losses of 0.16 SD were found, while younger children from schools with medium school-level SES experienced learning gains of 0.15 SD ( Gore et al., 2021 ). Third, low-performing students were more affected by COVID-19-related school closures in mathematics, while high-performing students were more affected by COVID-19-related school closures in reading ( Schult et al., 2021 ). Finally, low-performing students benefited more from systematic online-learning methods ( Clark et al., 2020 ; Spitzer and Musslick, 2021 ).

As the original studies were not designed to identify the reasons for these effects, additional studies are required to explain the three main differential effects exhaustively. In the following, we provide potential explanations as stated in the original studies. Regarding the first main differential effect (younger students are more affected compared to older students), Tomasik et al. (2020) state that the slower pace of students in primary school may be due to younger children relying more on cognitive scaffolding during instruction, because their capability for self-regulated learning might not be sufficiently developed. From a socio-emotional perspective, younger children might have been more sensitive to stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic ( Tomasik et al., 2020 ).

The reasons for students from low SES families being more affected relate to access to remote learning, their learning behavior, and the support provided from families and schools. Children from families with a low SES are less likely to have access to remote learning ( UNESCO, 2021 ), are less often provided with active learning assistance from their schools ( Tomasik et al., 2020 ), and spend less time on learning ( Meeter, 2021 ) than children from families with a high SES. Moreover, parents with a high SES are more likely to provide greater psychological support for their children ( OECD, 2019 ), which seems to be specifically relevant in a situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The differential effect on low-performing and high-performing students may be due to high-performing students being capable of improving their performance regardless of the learning environment, while low-performing students specifically benefit from systematic online learning ( Clark et al., 2020 ). Additionally, low-performing students might be less distracted in comparison to learning in a classroom setting ( Spitzer and Musslick, 2021 ). Finally, with the possibility to adapt the assignments in online programs individually to the students, low-performing children might have been addressed more thoroughly according to their needs ( Spitzer and Musslick, 2021 ).

The present work aimed to provide a first systematic overview of studies that reported effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement and to answer two research questions. First, what was the general effect of COVID-19-related school closures in spring 2020 on student achievement in primary and secondary education? Second, did school closures have differential effects on specific student groups?

In sum, there is clear evidence for a negative effect of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement. The reported effects are comparable in size to findings of research on summer losses ( d = −0.005 SD to −0.05 SD per week; see also Kuhfeld et al., 2020a ) and comparable to Woessmann's initial estimate. Hence, even though remote learning was implemented during COVID-19-related school closures, the effects achieved by remote learning were similar to those achieved when no teaching was implemented at all during summer vacation. Alarmingly, specifically younger children ( Tomasik et al., 2020 ) and children from families with a low SES ( Maldonado and De Witte, 2020 ; Engzell et al., 2021 ) were negatively affected by COVID-19-related school closures. This finding is in line with predictions of widening learning gaps and additive learning losses in subsequent school years ( Grewenig et al., 2020 ; Haeck and Lefebvre, 2020 ; Pensiero et al., 2020 ; Kaffenberger, 2021 ). This indicates that most remote learning measures implemented during the first school closures in spring 2020 were not effective for student learning; there was no difference between them and the absence of systematic teaching during summer vacation.

However, the present review can also identify online-learning measures that seem to be beneficial for student learning. Taking a closer look at studies that reported positive effects of school closures on student achievement, three of these studies ( Meeter, 2021 ; Spitzer and Musslick, 2021 ; van der Velde et al., 2021 ) used some kind of online-learning software to assess student achievement. Students in the studies of both Meeter (2021) and Spitzer and Musslick (2021) worked with online-learning software for mathematics, and students in the study of van der Velde et al. (2021) worked on online-learning software for language learning (i.e., for French). Hence, the positive effects of COVID-19-related school closures on performance in such online-learning programs may have occurred due to the increased use of software during school closures and the fact that students from these studies were familiar working with online-learning programs, hence, did not have to adapt to a new learning environment during COVID-19-related school closures. Additionally, Spitzer and Musslick (2021) reported that low-performing students benefited even more than high-performing students regarding their performance during COVID-19-related school closures from using the learning software. The authors explained this finding by considering that low-performing students were potentially less distracted by other students in a home-learning setting. These findings are in line with results by Clark et al. (2020) , showing low-performing students to specifically benefit from systematic online material.

The present review gives insights into the effects of the COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement in spring 2020. It has to be noted that the number of countries for which evidence of these effects are available is still small, and clustered around developed countries. Especially studies from developing countries are not available yet. We know, however, that the reduction in in-person learning was smaller for low-income countries than for medium-income countries ( UNESCO, 2021 ). Nevertheless, the proportion of students enrolled in primary or secondary education is considerably smaller in poorer countries ( Ward, 2020 ). It may be possible that studies coming from developing countries provide novel insights into the general and especially the differential effects of the COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement. The results of our systematic review can serve as a benchmark for these studies, once they emerge in the literature.

The first COVID-19-related school closures in spring 2020 were followed by similar measures in the fall and winter of 2020/2021. Due to the cumulative nature of learning processes and student achievement, additional learning losses are likely. Nevertheless, school closures do not seem to be initiated as quickly now as they were at the beginning of the pandemic, which is positive for learning. To counter the learning losses, on a micro level, educational policy makers should determine potential supportive measures that increase the active learning time on task. On a macro level, national policy makers should determine potential compensatory measures to support students in their learning and to avoid failed educational careers. In this regard, systematic online material and software have been found to compensate for learning losses, specifically in high-risk children. Hence, educational policy makers and educators should be aware of the importance of providing children with systematic material and ensuring that high-risk children, in particular, have access to adequate learning environments in order to circumvent learning losses and widening learning gaps that may be caused by subsequent school closures. We expect future studies focusing on the subsequent school closures to provide a more differentiated picture of the effects of COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement. For instance, studies may investigate whether there are differences in educational outcomes across countries with differing lockdown measures. Similarly, studies may investigate the reasons for the subject-specific general effects and the three main differential effects identified in this systematic review. Such studies require longitudinal approaches, and may provide educational policy makers with crucial additional information.

The goal of this systematic review was to provide a first evidence-based insight into the effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement in primary and secondary education. The onus is now on national educational policy makers to be aware of these effects and, together with educational and psychological research fields, to work toward the implementation of measures to mitigate or even counteract these negative effects. This may be one of the most important societal tasks for the post-COVID time.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SH and CK conducted the literature review and synthesis, with critical input by AF. SH wrote and revised the manuscript with contributions and feedback provided by CK, TD, and AF. All authors have been involved in the conceptual design of the review.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ PISA is an international large-scale assessment testing the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students in three core domains (Mathematics, Reading, and Science). Its main survey is administered every three years, with each rotating as the major domain. The results of the main surveys are scaled to fit approximately normal distributions, with means around 500 score points and standard deviations around 100 score points. A 10-point difference on the PISA scale corresponds to an effect size (Cohen's d ) of 0.10 ( OECD, 2019 ).

Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa-Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., Krutikova, S., et al. (2020). Learning During the Lockdown: REAL-time data on Children's Experiences During Home Learning. The Institute for Fiscal Studies . Available online at: https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14848

Google Scholar

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A., and Geven, K. (2020). Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A Set of Global Estimates . Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

Blume, F., Schmidt, A., Kramer, A. C., Schmiedek, F., and Neubauer, A. B. (2021). Homeschooling during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: the role of students' trait self-regulation and task attributes of daily learning tasks for students' daily self-regulation. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 1–25. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/tnrdj

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chadwick, R., and McLoughlin, E. (2021). Impact of the covid-19 crisis on learning, teaching and facilitation of practical activities in science upon reopening of Irish schools. Irish Educ. Stud. 40, 197–205. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2021.1915838

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Clark, A. E., Nong, H., Zhu, H., and Zhu, R. (2020). Compensating for Academic Loss: Online Learning and Student Performance During the COVID-19 Pandemic. HAL . Available online at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02901505

Depping, D., Lücken, M., Musekamp, F., and Thonke, F. (2021). Kompetenzstände Hamburger Schüler * innen vor und während der Corona-Pandemie [Alternative pupils' competence measurement in Hamburg during the Corona pandemic], “in Schule während der Corona-Pandemie. Neue Ergebnisse und Überblick über ein dynamisches Forschungsfeld , eds D. Fickermann and B. Edelste (Münster: Waxmann), 51–79.

Ehrler, M., Werninger, I., Schnider, B., Eichelberger, D. A., Naef, N., Disselhoff, V., et al. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with and without risk for neurodevelopmental impairments. Acta Paediatr. 110, 1281–1288. doi: 10.1111/apa.15775

Engzell, P., Frey, A., and Verhagen, M. D. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. SocArXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/ve4z7

Gadermann, A. C., Thomson, K. C., Richardson, C. G., Gagné, M., McAuliffe, C., Hirani, S., et al. (2021). Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11:e042871. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042871

Gore, J., Fray, L., Miller, A., Harris, J., and Taggart, W. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: an empirical study. Austr. Educ. Res. 1–33. doi: 10.1007/s13384-021-00436-w

Grewenig, E., Lergetporer, P., Werner, K., Woessmann, L., and Zierow, L. (2020). COVID-19 and Educational Inequality: How School Closures Affect Low-and High-Achieving Students . EconStor. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/227347

Haeck, C., and Lefebvre, P. (2020). Pandemic school closures may increase inequality in test scores. Canad. Pub. Policy 46, S82–S87. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2020-055

Haug, N., Geyrhofer, L., Londei, A., Dervic, E., Desvars-Larrive, A., Loreto, V., et al. (2020). Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0

Kaffenberger, M. (2021). Modelling the long-run learning impact of the Covid-19 learning shock: actions to (more than) mitigate loss. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 81:102326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102326

Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., and Liu, J. (2020a). Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Educ. Res. 49, 549–565. doi: 10.3102/0013189X20965918

Kuhfeld, M., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., and Lewis, K. (2020b). Learning during COVID-19: Initial findings on students' reading and math achievement and growth . NWEA. Available online at: https://www.ewa.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/learning_during_covid-19_brief_nwea_nov2020_final.pdf?1606835922

Maity, S., Sahu, T. N., and Sen, N. (2020). Panoramic view of digital education in COVID-19: a new explored avenue. Rev. Educ. 9, 424–426. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3249

Maldonado, J. E., and De Witte, K. (2020). The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes . KU Leuven, Faculty of Economics and Business. Available online at: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/588087

Meeter, M. (2021). Primary school mathematics during Covid-19: No evidence of learning gaps in adaptive practicing results. PsyArXiv.

O'Connor, M. (2020). School counselling during COVID-19: an initial examination of school counselling use during a 5-week remote learning period. Past. Care Educ. 1–11. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2020.1855674

OECD (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume II): Where All Students Can Succeed . OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/b5fd1b8f-en

O'Sullivan, K., Clark, S., McGrane, A., Rock, N., Burke, L., Boyle, N., et al. (2021). A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:1062. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031062

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.31222/osf.io/v7gm2

Pensiero, N., Kelly, A., and Bokhove, C. (2020). Learning inequalities during the Covid-19 pandemic: How families cope with home-schooling . University of Southampton research report.

Schult, J., Mahler, N., Fauth, B., and Lindner, M. A. (2021). Did students learn less during the COVID-19 pandemic? reading and mathematics competencies before and after the first pandemic wave. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/pqtgf

Smith, J., Guimond, F. A., Bergeron, J., St-Amand, J., Fitzpatrick, C., and Gagnon, M. (2021). Changes in students' achievement motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: a function of extraversion/introversion? Educ. Sci. 11:30. doi: 10.3390/educsci11010030

Spitzer, M., and Musslick, S. (2021). Academic performance of K-12 students in an online-learning environment for mathematics increased during the shutdown of schools in wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE , 16:e0255629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255629

Sterne, J. A. C., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., et al. (2016). ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

Tomasik, M. J., Helbling, L. A., and Moser, U. (2020). Educational gains of in-person vs. distance learning in primary and secondary schools: a natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Switzerland. Int. J. Psychol. 56, 566–576. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12728

UNESCO UNICEF, The World Bank, and OECD. (2021). What's Next? Lessons on Education Recovery . Washington, DC: The World Bank.

van der Velde, M., Sense, F., Spijkers, R., Meeter, M., and van Rijn, H. (2021). Lockdown learning: changes in online study activity and performance of Dutch secondary school students during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/fr2v8

Ward, M. (2020). PISA for Development: Out-of-School Assessment, PISA in Focus . OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/491fb74a-en

Woessmann, L. (2020). Folgekosten ausbleibenden Lernens: Was wir über die Corona-bedingten Schulschließungen aus der Forschung lernen können [Follow-up costs of an absence of learning: What research can teach us about corona-related school closures]. ifo Schnelldienst 73, 38–44. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/225139

Wyse, A. E., Stickney, E. M., Butz, D., Beckler, A., and Close, C. N. (2020). The potential impact of COVID-19 on student learning and how schools can respond. Educ. Measure. Issue Pract. 39, 60–64. doi: 10.1111/emip.12357

Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 174, 898–900. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619

Zaccoletti, S., Camacho, A., Correia, N., Aguiar, C., Mason, L., Alves, R. A., et al. (2020). Parents' perceptions of student academic motivation during the COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-country comparison. Front. Psychol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.592670

Keywords: systematic review, COVID-19, school closure, student achievement, learning loss

Citation: Hammerstein S, König C, Dreisörner T and Frey A (2021) Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement-A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 12:746289. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289

Received: 23 July 2021; Accepted: 20 August 2021; Published: 16 September 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Hammerstein, König, Dreisörner and Frey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Svenja Hammerstein, hammerstein@psych.uni-frankfurt.de

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 30 January 2023

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Bastian A. Betthäuser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4544-4073 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Anders M. Bach-Mortensen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7804-7958 2 &

- Per Engzell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2404-6308 3 , 4 , 5

Nature Human Behaviour volume 7 , pages 375–385 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

75k Accesses

150 Citations

1973 Altmetric

Metrics details

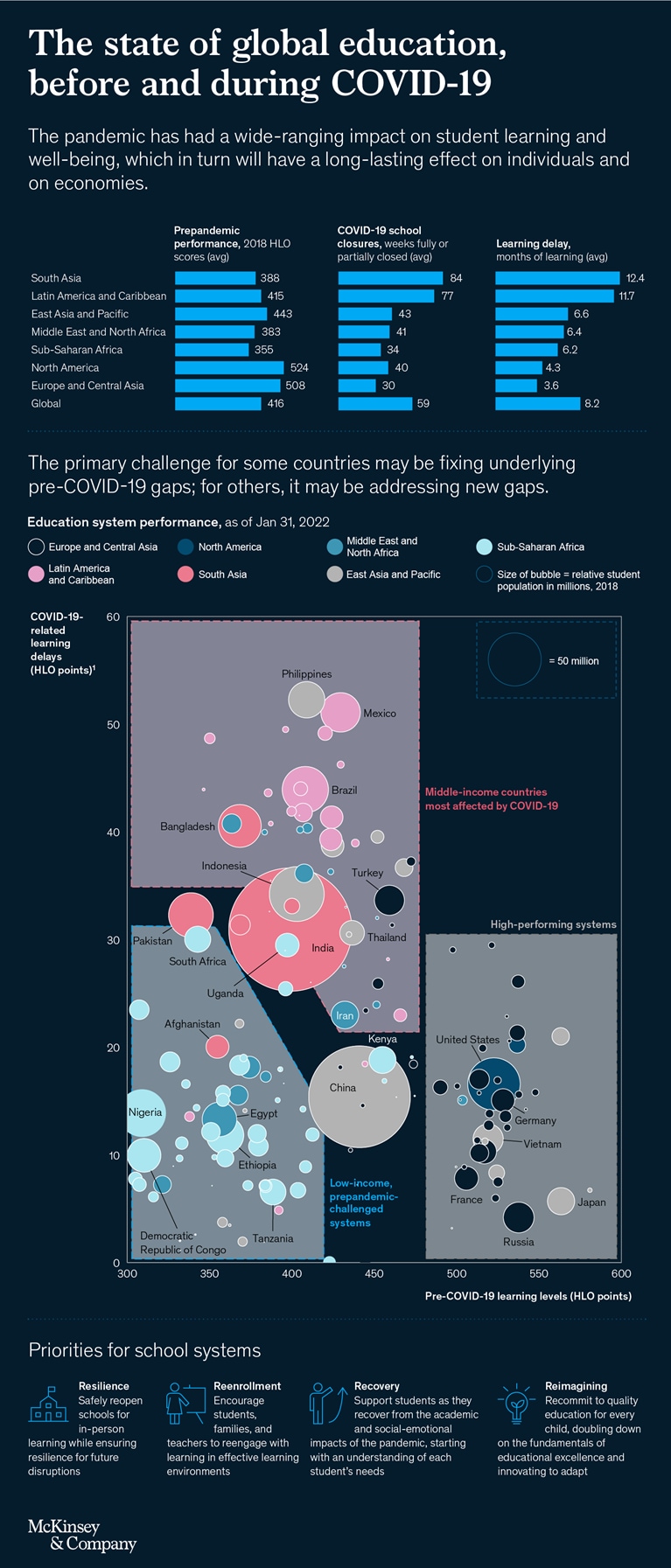

- Social policy

To what extent has the learning progress of school-aged children slowed down during the COVID-19 pandemic? A growing number of studies address this question, but findings vary depending on context. Here we conduct a pre-registered systematic review, quality appraisal and meta-analysis of 42 studies across 15 countries to assess the magnitude of learning deficits during the pandemic. We find a substantial overall learning deficit (Cohen’s d = −0.14, 95% confidence interval −0.17 to −0.10), which arose early in the pandemic and persists over time. Learning deficits are particularly large among children from low socio-economic backgrounds. They are also larger in maths than in reading and in middle-income countries relative to high-income countries. There is a lack of evidence on learning progress during the pandemic in low-income countries. Future research should address this evidence gap and avoid the common risks of bias that we identify.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

A methodological perspective on learning in the developing brain

Measuring and forecasting progress in education: what about early childhood?

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to one of the largest disruptions to learning in history. To a large extent, this is due to school closures, which are estimated to have affected 95% of the world’s student population 1 . But even when face-to-face teaching resumed, instruction has often been compromised by hybrid teaching, and by children or teachers having to quarantine and miss classes. The effect of limited face-to-face instruction is compounded by the pandemic’s consequences for children’s out-of-school learning environment, as well as their mental and physical health. Lockdowns have restricted children’s movement and their ability to play, meet other children and engage in extra-curricular activities. Children’s wellbeing and family relationships have also suffered due to economic uncertainties and conflicting demands of work, care and learning. These negative consequences can be expected to be most pronounced for children from low socio-economic family backgrounds, exacerbating pre-existing educational inequalities.

It is critical to understand the extent to which learning progress has changed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use the term ‘learning deficit’ to encompass both a delay in expected learning progress, as well as a loss of skills and knowledge already gained. The COVID-19 learning deficit is likely to affect children’s life chances through their education and labour market prospects. At the societal level, it can have important implications for growth, prosperity and social cohesion. As policy-makers across the world are seeking to limit further learning deficits and to devise policies to recover learning deficits that have already been incurred, assessing the current state of learning is crucial. A careful assessment of the COVID-19 learning deficit is also necessary to weigh the true costs and benefits of school closures.

A number of narrative reviews have sought to summarize the emerging research on COVID-19 and learning, mostly focusing on learning progress relatively early in the pandemic 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Moreover, two reviews harmonized and synthesized existing estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic 7 , 8 . In line with the narrative reviews, these two reviews find a substantial reduction in learning progress during the pandemic. However, this finding is based on a relatively small number of studies (18 and 10 studies, respectively). The limited evidence that was available at the time these reviews were conducted also precluded them from meta-analysing variation in the magnitude of learning deficits over time and across subjects, different groups of students or country contexts.

In this Article, we conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits 2.5 years into the pandemic. Our primary pre-registered research question was ‘What is the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning progress amongst school-age children?’, and we address this question using evidence from studies examining changes in learning outcomes during the pandemic. Our second pre-registered research aim was ‘To examine whether the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning differs across different social background groups, age groups, boys and girls, learning areas or subjects, national contexts’.

We contribute to the existing research in two ways. First, we describe and appraise the up-to-date body of evidence, including its geographic reach and quality. More specifically, we ask the following questions: (1) what is the state of the evidence, in terms of the available peer-reviewed research and grey literature, on learning progress of school-aged children during the COVID-19 pandemic?, (2) which countries are represented in the available evidence? and (3) what is the quality of the existing evidence?

Our second contribution is to harmonize, synthesize and meta-analyse the existing evidence, with special attention to variation across different subpopulations and country contexts. On the basis of the identified studies, we ask (4) to what extent has the learning progress of school-aged children changed since the onset of the pandemic?, (5) how has the magnitude of the learning deficit (if any) evolved since the beginning of the pandemic?, (6) to what extent has the pandemic reinforced inequalities between children from different socio-economic backgrounds?, (7) are there differences in the magnitude of learning deficits between subject domains (maths and reading) and between age groups (primary and secondary students)? and (8) to what extent does the magnitude of learning deficits vary across national contexts?

Below, we report our answers to each of these questions in turn. The questions correspond to the analysis plan set out in our pre-registered protocol ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021249944 ), but we have adjusted the order and wording to aid readability. We had planned to examine gender differences in learning progress during the pandemic, but found there to be insufficient evidence to conduct this subgroup analysis, as the large majority of the identified studies do not provide evidence on learning deficits separately by gender. We also planned to examine how the magnitude of learning deficits differs across groups of students with varying exposures to school closures. This was not possible as the available data on school closures lack sufficient depth with respect to variation of school closures within countries, across grade levels and with respect to different modes of instruction, to meaningfully examine this association.

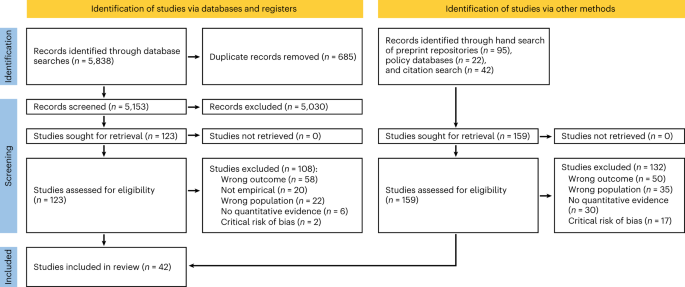

The state of the evidence

Our systematic review identified 42 studies on learning progress during the COVID-19 pandemic that met our inclusion criteria. To be included in our systematic review and meta-analysis, studies had to use a measure of learning that can be standardized (using Cohen’s d ) and base their estimates on empirical data collected since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (rather than making projections based on pre-COVID-19 data). As shown in Fig. 1 , the initial literature search resulted in 5,153 hits after removal of duplicates. All studies were double screened by the first two authors. The formal database search process identified 15 eligible studies. We also hand searched relevant preprint repositories and policy databases. Further, to ensure that our study selection was as up to date as possible, we conducted two full forward and backward citation searches of all included studies on 15 February 2022, and on 8 August 2022. The citation and preprint hand searches allowed us to identify 27 additional eligible studies, resulting in a total of 42 studies. Most of these studies were published after the initial database search, which illustrates that the body of evidence continues to expand. Most studies provide multiple estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits, separately for maths and reading and for different school grades. The number of estimates ( n = 291) is therefore larger than the number of included studies ( n = 42).

Flow diagram of the study identification and selection process, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The geographic reach of evidence is limited

Table 1 presents all included studies and estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits (in brackets), grouped by the 15 countries represented: Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the United States. About half of the estimates ( n = 149) are from the United States, 58 are from the UK, a further 70 are from other European countries and the remaining 14 estimates are from Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. As this list shows, there is a strong over-representation of studies from high-income countries, a dearth of studies from middle-income countries and no studies from low-income countries. This skewed representation should be kept in mind when interpreting our synthesis of the existing evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits.

The quality of evidence is mixed

We assessed the quality of the evidence using an adapted version of the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool 9 . More specifically, we analysed the risk of bias of each estimate from confounding, sample selection, classification of treatments, missing data, the measurement of outcomes and the selection of reported results. A.M.B.-M. and B.A.B. performed the risk-of-bias assessments, which were independently checked by the respective other author. We then assigned each study an overall risk-of-bias rating (low, moderate, serious or critical) based on the estimate and domain with the highest risk of bias.

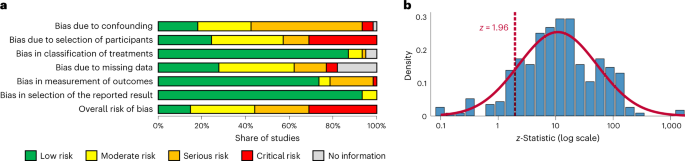

Figure 2a shows the distribution of all studies of COVID-19 learning deficits according to their risk-of-bias rating separately for each domain (top six rows), as well as the distribution of studies according to their overall risk of bias rating (bottom row). The overall risk of bias was considered ‘low’ for 15% of studies, ‘moderate’ for 30% of studies, ‘serious’ for 25% of studies and ‘critical’ for 30% of studies.

a , Domain-specific and overall distribution of studies of COVID-19 learning deficits by risk of bias rating using ROBINS-I, including studies rated to be at critical risk of bias ( n = 19 out of a total of n = 61 studies shown in this figure). In line with ROBINS-I guidance, studies rated to be at critical risk of bias were excluded from all analyses and other figures in this article and in the Supplementary Information (including b ). b , z curve: distribution of the z scores of all estimates included in the meta-analysis ( n = 291) to test for publication bias. The dotted line indicates z = 1.96 ( P = 0.050), the conventional threshold for statistical significance. The overlaid curve shows a normal distribution. The absence of a spike in the distribution of the z scores just above the threshold for statistical significance and the absence of a slump just below it indicate the absence of evidence for publication bias.

In line with ROBINS-I guidance, we excluded studies rated to be at critical risk of bias ( n = 19) from all of our analyses and figures, except for Fig. 2a , which visualizes the distribution of studies according to their risk of bias 9 . These are thus not part of the 42 studies included in our meta-analysis. Supplementary Table 2 provides an overview of these studies as well as the main potential sources of risk of bias. Moreover, in Supplementary Figs. 3 – 6 , we replicate all our results excluding studies deemed to be at serious risk of bias.

As shown in Fig. 2a , common sources of potential bias were confounding, sample selection and missing data. Studies rated at risk of confounding typically compared only two timepoints, without accounting for longer time trends in learning progress. The main causes of selection bias were the use of convenience samples and insufficient consideration of self-selection by schools or students. Several studies found evidence of selection bias, often with students from a low socio-economic background or schools in deprived areas being under-represented after (as compared with before) the pandemic, but this was not always adjusted for. Some studies also reported a higher amount of missing data post-pandemic, again generally without adjustment, and several studies did not report any information on missing data. For an overview of the risk-of-bias ratings for each domain of each study, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 .

No evidence of publication bias

Publication bias can occur if authors self-censor to conform to theoretical expectations, or if journals favour statistically significant results. To mitigate this concern, we include not only published papers, but also preprints, working papers and policy reports.

Moreover, Fig. 2b tests for publication bias by showing the distribution of z -statistics for the effect size estimates of all identified studies. The dotted line indicates z = 1.96 ( P = 0.050), the conventional threshold for statistical significance. The overlaid curve shows a normal distribution. If there was publication bias, we would expect a spike just above the threshold, and a slump just below it. There is no indication of this. Moreover, we do not find a left-skewed distribution of P values (see P curve in Supplementary Fig. 2a ), or an association between estimates of learning deficits and their standard errors (see funnel plot in Supplementary Fig. 2b ) that would suggest publication bias. Publication bias thus does not appear to be a major concern.

Having assessed the quality of the existing evidence, we now present the substantive results of our meta-analysis, focusing on the magnitude of COVID-19 learning deficits and on the variation in learning deficits over time, across different groups of students, and across country contexts.

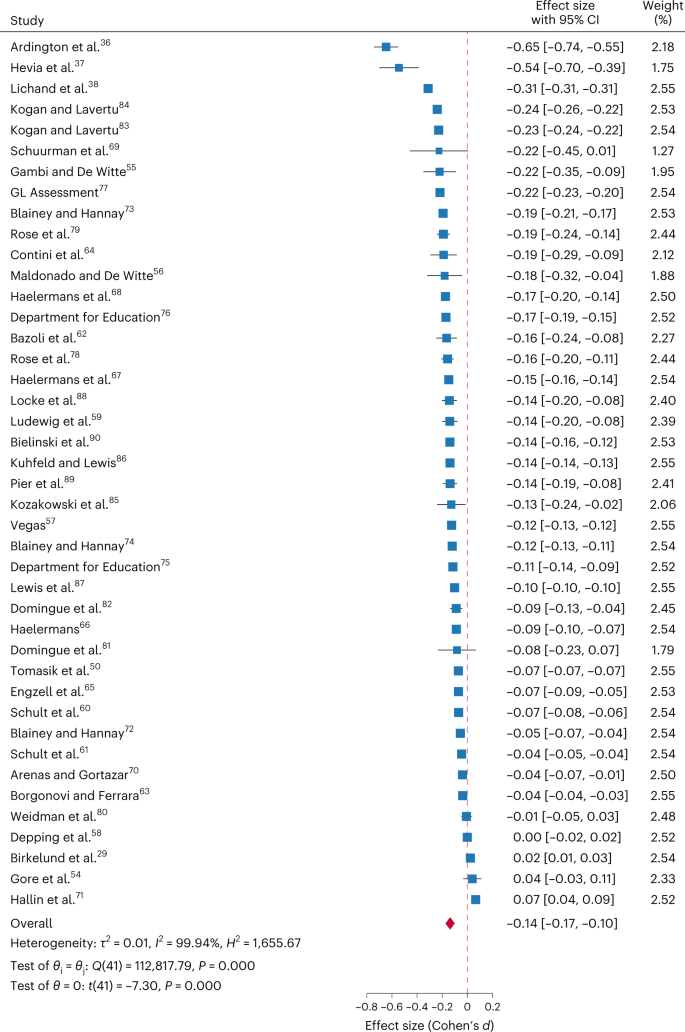

Learning progress slowed substantially during the pandemic

Figure 3 shows the effect sizes that we extracted from each study (averaged across grades and learning subject) as well as the pooled effect size (red diamond). Effects are expressed in standard deviations, using Cohen’s d . Estimates are pooled using inverse variance weights. The pooled effect size across all studies is d = −0.14, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.000, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.17 to −0.10. Under normal circumstances, students generally improve their performance by around 0.4 standard deviations per school year 10 , 11 , 12 . Thus, the overall effect of d = −0.14 suggests that students lost out on 0.14/0.4, or about 35%, of a school year’s worth of learning. On average, the learning progress of school-aged children has slowed substantially during the pandemic.

Effect sizes are expressed in standard deviations, using Cohen’s d , with 95% CI, and are sorted by magnitude.

Learning deficits arose early in the pandemic and persist

One may expect that children were able to recover learning that was lost early in the pandemic, after teachers and families had time to adjust to the new learning conditions and after structures for online learning and for recovering early learning deficits were set up. However, existing research on teacher strikes in Belgium 13 and Argentina 14 , shortened school years in Germany 15 and disruptions to education during World War II 16 suggests that learning deficits are difficult to compensate and tend to persist in the long run.

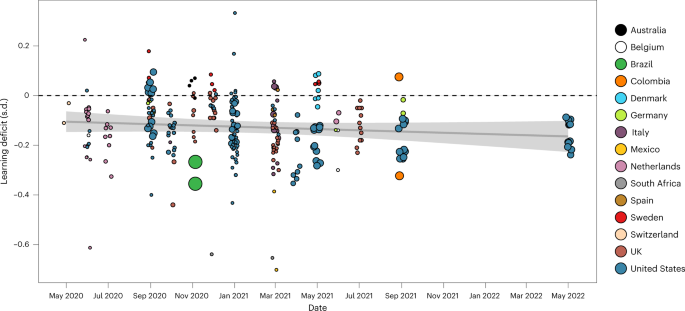

Figure 4 plots the magnitude of estimated learning deficits (on the vertical axis) by the date of measurement (on the horizontal axis). The colour of the circles reflects the relevant country, the size of the circles indicates the sample size for a given estimate and the line displays a linear trend. The figure suggests that learning deficits opened up early in the pandemic and have neither closed nor substantially widened since then. We find no evidence that the slope coefficient is different from zero ( β months = −0.00, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.097, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.00). This implies that efforts by children, parents, teachers and policy-makers to adjust to the changed circumstance have been successful in preventing further learning deficits but so far have been unable to reverse them. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8 , the pattern of persistent learning deficits also emerges within each of the three countries for which we have a relatively large number of estimates at different timepoints: the United States, the UK and the Netherlands. However, it is important to note that estimates of learning deficits are based on distinct samples of students. Future research should continue to follow the learning progress of cohorts of students in different countries to reveal how learning deficits of these cohorts have developed and continue to develop since the onset of the pandemic.

The horizontal axis displays the date on which learning progress was measured. The vertical axis displays estimated learning deficits, expressed in standard deviation (s.d.) using Cohen’s d . The colour of the circles reflects the respective country, the size of the circles indicates the sample size for a given estimate and the line displays a linear trend with a 95% CI. The trend line is estimated as a linear regression using ordinary least squares, with standard errors clustered at the study level ( n = 42 clusters). β months = −0.00, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.097, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.00.

Socio-economic inequality in education increased

Existing research on the development of learning gaps during summer vacations 17 , 18 , disruptions to schooling during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone and Guinea 19 , and the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan 20 shows that the suspension of face-to-face teaching can increase educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds. Learning deficits during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to have been particularly pronounced for children from low socio-economic backgrounds. These children have been more affected by school closures than children from more advantaged backgrounds 21 . Moreover, they are likely to be disadvantaged with respect to their access and ability to use digital learning technology, the quality of their home learning environment, the learning support they receive from teachers and parents, and their ability to study autonomously 22 , 23 , 24 .

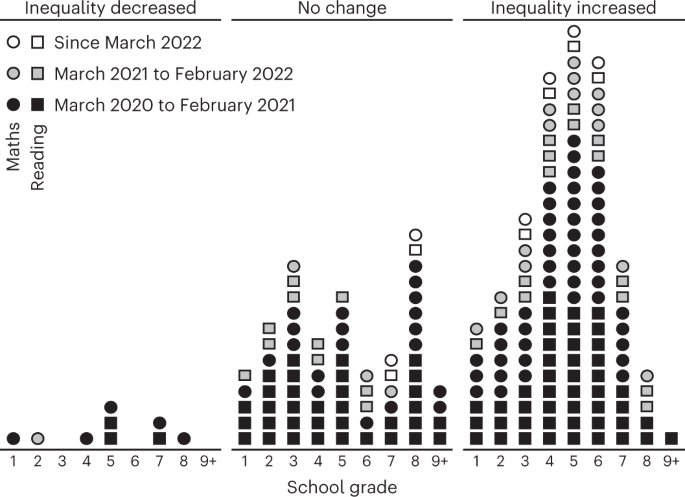

Most studies we identify examine changes in socio-economic inequality during the pandemic, attesting to the importance of the issue. As studies use different measures of socio-economic background (for example, parental income, parental education, free school meal eligibility or neighbourhood disadvantage), pooling the estimates is not possible. Instead, we code all estimates according to whether they indicate a reduction, no change or an increase in learning inequality during the pandemic. Figure 5 displays this information. Estimates that indicate an increase in inequality are shown on the right, those that indicate a decrease on the left and those that suggest no change in the middle. Squares represent estimates of changes in inequality during the pandemic in reading performance, and circles represent estimates of changes in inequality in maths performance. The shading represents when in the pandemic educational inequality was measured, differentiating between the first, second and third year of the pandemic. Estimates are also arranged horizontally by grade level. A large majority of estimates indicate an increase in educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds. This holds for both maths and reading, across primary and secondary education, at each stage of the pandemic, and independently of how socio-economic background is measured.

Each circle/square refers to one estimate of over-time change in inequality in maths/reading performance ( n = 211). Estimates that find a decrease/no change/increase in inequality are grouped on the left/middle/right. Within these categories, estimates are ordered horizontally by school grade. The shading indicates when in the pandemic a given measure was taken.

Learning deficits are larger in maths than in reading

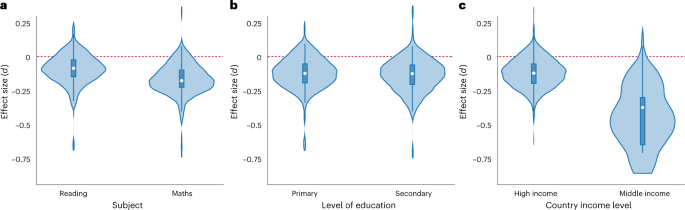

Available research on summer learning deficits 17 , 25 , student absenteeism 26 , 27 and extreme weather events 28 suggests that learning progress in mathematics is more dependent on formal instruction than in reading. This might be due to parents being better equipped to help their children with reading, and children advancing their reading skills (but not their maths skills) when reading for enjoyment outside of school. Figure 6a shows that, similarly to earlier disruptions to learning, the estimated learning deficits during the COVID-19 pandemic are larger for maths than for reading (mean difference δ = −0.07, t (41) = −4.02, two-tailed P = 0.000, 95% CI −0.11 to −0.04). This difference is statistically significant and robust to dropping estimates from individual countries (Supplementary Fig. 9 ).

Each plot shows the distribution of COVID-19 learning deficit estimates for the respective subgroup, with the box marking the interquartile range and the white circle denoting the median. Whiskers mark upper and lower adjacent values: the furthest observation within 1.5 interquartile range of either side of the box. a , Learning subject (reading versus maths). Median: reading −0.09, maths −0.18. Interquartile range: reading −0.15 to −0.02, maths −0.23 to −0.09. b , Level of education (primary versus secondary). Median: primary −0.12, secondary −0.12. Interquartile range: primary −0.19 to −0.05, secondary −0.21 to −0.06. c , Country income level (high versus middle). Median: high −0.12, middle −0.37. Interquartile range: high −0.20 to −0.05, middle −0.65 to −0.30.

No evidence of variation across grade levels

One may expect learning deficits to be smaller for older than for younger children, as older children may be more autonomous in their learning and better able to cope with a sudden change in their learning environment. However, older students were subject to longer school closures in some countries, such as Denmark 29 , based partly on the assumption that they would be better able to learn from home. This may have offset any advantage that older children would otherwise have had in learning remotely.

Figure 6b shows the distribution of estimates of learning deficits for students at the primary and secondary level, respectively. Our analysis yields no evidence of variation in learning deficits across grade levels (mean difference δ = −0.01, t (41) = −0.59, two-tailed P = 0.556, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.03). Due to the limited number of available estimates of learning deficits, we cannot be certain about whether learning deficits differ between primary and secondary students or not.

Learning deficits are larger in poorer countries

Low- and middle-income countries were already struggling with a learning crisis before the pandemic. Despite large expansions of the proportion of children in school, children in low- and middle-income countries still perform poorly by international standards, and inequality in learning remains high 30 , 31 , 32 . The pandemic is likely to deepen this learning crisis and to undo past progress. Schools in low- and middle-income countries have not only been closed for longer, but have also had fewer resources to facilitate remote learning 33 , 34 . Moreover, the economic resources, availability of digital learning equipment and ability of children, parents, teachers and governments to support learning from home are likely to be lower in low- and middle-income countries 35 .

As discussed above, most evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits comes from high-income countries. We found no studies on low-income countries that met our inclusion criteria, and evidence from middle-income countries is limited to Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. Figure 6c groups the estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits in these four middle-income countries together (on the right) and compares them with estimates from high-income countries (on the left). The learning deficit is appreciably larger in middle-income countries than in high-income countries (mean difference δ = −0.29, t (41) = −2.78, two-tailed P = 0.008, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.08). In fact, the three largest estimates of learning deficits in our sample are from middle-income countries (Fig. 3 ) 36 , 37 , 38 .

Two years since the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a growing number of studies examining the learning progress of school-aged children during the pandemic. This paper first systematically reviews the existing literature on learning progress of school-aged children during the pandemic and appraises its geographic reach and quality. Second, it harmonizes, synthesizes and meta-analyses the existing evidence to examine the extent to which learning progress has changed since the onset of the pandemic, and how it varies across different groups of students and across country contexts.

Our meta-analysis suggests that learning progress has slowed substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pooled effect size of d = −0.14, implies that students lost out on about 35% of a normal school year’s worth of learning. This confirms initial concerns that substantial learning deficits would arise during the pandemic 10 , 39 , 40 . But our results also suggest that fears of an accumulation of learning deficits as the pandemic continues have not materialized 41 , 42 . On average, learning deficits emerged early in the pandemic and have neither closed nor widened substantially. Future research should continue to follow the learning progress of cohorts of students in different countries to reveal how learning deficits of these cohorts have developed and continue to develop since the onset of the pandemic.

Most studies that we identify find that learning deficits have been largest for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. This holds across different timepoints during the pandemic, countries, grade levels and learning subjects, and independently of how socio-economic background is measured. It suggests that the pandemic has exacerbated educational inequalities between children from different socio-economic backgrounds, which were already large before the pandemic 43 , 44 . Policy initiatives to compensate learning deficits need to prioritize support for children from low socio-economic backgrounds in order to allow them to recover the learning they lost during the pandemic.

There is a need for future research to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender inequality in education. So far, there is very little evidence on this issue. The large majority of the studies that we identify do not examine learning deficits separately by gender.

Comparing estimates of learning deficits across subjects, we find that learning deficits tend to be larger in maths than in reading. As noted above, this may be due to the fact that parents and children have been in a better position to compensate school-based learning in reading by reading at home. Accordingly, there are grounds for policy initiatives to prioritize the compensation of learning deficits in maths and other science subjects.

A limitation of this study and the existing body of evidence on learning progress during the COVID-19 pandemic is that the existing studies primarily focus on high-income countries, while there is a dearth of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. This is particularly concerning because the small number of existing studies from middle-income countries suggest that learning deficits have been particularly severe in these countries. Learning deficits are likely to be even larger in low-income countries, considering that these countries already faced a learning crisis before the pandemic, generally implemented longer school closures, and were under-resourced and ill-equipped to facilitate remote learning 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 45 . It is critical that this evidence gap on low- and middle-income countries is addressed swiftly, and that the infrastructure to collect and share data on educational performance in middle- and low-income countries is strengthened. Collecting and making available these data is a key prerequisite for fully understanding how learning progress and related outcomes have changed since the onset of the pandemic 46 .

A further limitation is that about half of the studies that we identify are rated as having a serious or critical risk of bias. We seek to limit the risk of bias in our results by excluding all studies rated to be at critical risk of bias from all of our analyses. Moreover, in Supplementary Figs. 3 – 6 , we show that our results are robust to further excluding studies deemed to be at serious risk of bias. Future studies should minimize risk of bias in estimating learning deficits by employing research designs that appropriately account for common sources of bias. These include a lack of accounting for secular time trends, non-representative samples and imbalances between treatment and comparison groups.

The persistence of learning deficits two and a half years into the pandemic highlights the need for well-designed, well-resourced and decisive policy initiatives to recover learning deficits. Policy-makers, schools and families will need to identify and realize opportunities to complement and expand on regular school-based learning. Experimental evidence from low- and middle-income countries suggests that even relatively low-tech and low-cost learning interventions can have substantial, positive effects on students’ learning progress in the context of remote learning. For example, sending SMS messages with numeracy problems accompanied by short phone calls was found to lead to substantial learning gains in numeracy in Botswana 47 . Sending motivational text messages successfully limited learning losses in maths and Portuguese in Brazil 48 .

More evidence is needed to assess the effectiveness of other interventions for limiting or recovering learning deficits. Potential avenues include the use of the often extensive summer holidays to offer summer schools and learning camps, extending school days and school weeks, and organizing and scaling up tutoring programmes. Further potential lies in developing, advertising and providing access to learning apps, online learning platforms or educational TV programmes that are free at the point of use. Many countries have already begun investing substantial resources to capitalize on some of these opportunities. If these interventions prove effective, and if the momentum of existing policy efforts is maintained and expanded, the disruptions to learning during the pandemic may be a window of opportunity to improve the education afforded to children.

Eligibility criteria

We consider all types of primary research, including peer-reviewed publications, preprints, working papers and reports, for inclusion. To be eligible for inclusion, studies have to measure learning progress using test scores that can be standardized across studies using Cohen’s d . Moreover, studies have to be in English, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Norwegian, Spanish or Swedish.

Search strategy and study identification

We identified relevant studies using the following steps. First, we developed a Boolean search string defining the population (school-aged children), exposure (the COVID-19 pandemic) and outcomes of interest (learning progress). The full search string can be found in Section 1.1 of Supplementary Information . Second, we used this string to search the following academic databases: Coronavirus Research Database, the Education Resources Information Centre, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Politics Collection (PAIS index, policy file index, political science database and worldwide political science abstracts), Social Science Database, Sociology Collection (applied social science index and abstracts, sociological abstracts and sociology database), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Web of Science. Second, we hand-searched multiple preprint and working paper repositories (Social Science Research Network, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, IZA, National Bureau of Economic Research, OSF Preprints, PsyArXiv, SocArXiv and EdArXiv) and relevant policy websites, including the websites of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations, the World Bank and the Education Endowment Foundation. Third, we periodically posted our protocol via Twitter in order to crowdsource additional relevant studies not identified through the search. All titles and abstracts identified in our search were double-screened using the Rayyan online application 49 . Our initial search was conducted on 27 April 2021, and we conducted two forward and backward citation searches of all eligible studies identified in the above steps, on 14 February 2022, and on 8 August 2022, to ensure that our analysis includes recent relevant research.

Data extraction

From the studies that meet our inclusion criteria we extracted all estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic, separately for maths and reading and for different school grades. We also extracted the corresponding sample size, standard error, date(s) of measurement, author name(s) and country. Last, we recorded whether studies differentiate between children’s socio-economic background, which measure is used to this end and whether studies find an increase, decrease or no change in learning inequality. We contacted study authors if any of the above information was missing in the study. Data extraction was performed by B.A.B. and validated independently by A.M.B.-M., with discrepancies resolved through discussion and by conferring with P.E.

Measurement and standardizationr

We standardize all estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic using Cohen’s d , which expresses effect sizes in terms of standard deviations. Cohen’s d is calculated as the difference in the mean learning gain in a given subject (maths or reading) over two comparable periods before and after the onset of the pandemic, divided by the pooled standard deviation of learning progress in this subject:

Effect sizes expressed as β coefficients are converted to Cohen’s d :

We use a binary indicator for whether the study outcome is maths or reading. One study does not differentiate the outcome but includes a composite of maths and reading scores 50 .

Level of education

We distinguish between primary and secondary education. We first consulted the original studies for this information. Where this was not stated in a given study, students’ age was used in conjunction with information about education systems from external sources to determine the level of education 51 .

Country income level

We follow the World Bank’s classification of countries into four income groups: low, lower-middle, upper-middle and high income. Four countries in our sample are in the upper-middle-income group: Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. All other countries are in the high-income group.

Data synthesis

We synthesize our data using three synthesis techniques. First, we generate a forest plot, based on all available estimates of learning progress during the pandemic. We pool estimates using a random-effects restricted maximum likelihood model and inverse variance weights to calculate an overall effect size (Fig. 3 ) 52 . Second, we code all estimates of changes in educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds during the pandemic, according to whether they indicate an increase, a decrease or no change in educational inequality. We visualize the resulting distribution using a harvest plot (Fig. 5 ) 53 . Third, given that the limited amount of available evidence precludes multivariate or causal analyses, we examine the bivariate association between COVID-19 learning deficits and the months in which learning was measured using a scatter plot (Fig. 4 ), and the bivariate association between COVID-19 learning deficits and subject, grade level and countries’ income level, using a series of violin plots (Fig. 6 ). The reported estimates, CIs and statistical significance tests of these bivariate associations are based on common-effects models with standard errors clustered by study, and two-sided tests. With respect to statistical tests reported, the data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. The distribution of estimates of learning deficits is shown separately for the different moderator categories in Fig. 6 .

Pre-registration

We prospectively registered a protocol of our systematic review and meta-analysis in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021249944) on 19 April 2021 ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021249944 ).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in the analyses for this manuscript were compiled by the authors based on the studies identified in the systematic review. The data are available on the Open Science Framework repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/u8gaz ). For our systematic review, we searched the following databases: Coronavirus Research Database ( https://proquest.libguides.com/covid19 ), Education Resources Information Centre database ( https://eric.ed.gov ), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ibss-set-c/ ), Politics Collection ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ProQuest-Politics-Collection/ ), Social Science Database ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/pq_social_science/ ), Sociology Collection ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ProQuest-Sociology-Collection/ ), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature ( https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/cinahl-database ) and Web of Science ( https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/ ). We also searched the following preprint and working paper repositories: Social Science Research Network ( https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/DisplayJournalBrowse.cfm ), Munich Personal RePEc Archive ( https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de ), IZA ( https://www.iza.org/content/publications ), National Bureau of Economic Research ( https://www.nber.org/papers?page=1&perPage=50&sortBy=public_date ), OSF Preprints ( https://osf.io/preprints/ ), PsyArXiv ( https://psyarxiv.com ), SocArXiv ( https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv ) and EdArXiv ( https://edarxiv.org ).

Code availability

All code needed to replicate our findings is available on the Open Science Framework repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/u8gaz ).

The Impact of COVID-19 on Children. UN Policy Briefs (United Nations, 2020).

Donnelly, R. & Patrinos, H. A. Learning loss during Covid-19: An early systematic review. Prospects (Paris) 51 , 601–609 (2022).

Hammerstein, S., König, C., Dreisörner, T. & Frey, A. Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289 (2021).

Panagouli, E. et al. School performance among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Children 8 , 1134 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Patrinos, H. A., Vegas, E. & Carter-Rau, R. An Analysis of COVID-19 Student Learning Loss (World Bank, 2022).

Zierer, K. Effects of pandemic-related school closures on pupils’ performance and learning in selected countries: a rapid review. Educ. Sci. 11 , 252 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

König, C. & Frey, A. The impact of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 41 , 16–22 (2022).

Storey, N. & Zhang, Q. A meta-analysis of COVID learning loss. Preprint at EdArXiv (2021).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919 (2016).

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A. & Geven, K. Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A Set of Global Estimates (World Bank, 2020).

Bloom, H. S., Hill, C. J., Black, A. R. & Lipsey, M. W. Performance trajectories and performance gaps as achievement effect-size benchmarks for educational interventions. J. Res. Educ. Effectiveness 1 , 289–328 (2008).

Hill, C. J., Bloom, H. S., Black, A. R. & Lipsey, M. W. Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2 , 172–177 (2008).

Belot, M. & Webbink, D. Do teacher strikes harm educational attainment of students? Labour 24 , 391–406 (2010).

Jaume, D. & Willén, A. The long-run effects of teacher strikes: evidence from Argentina. J. Labor Econ. 37 , 1097–1139 (2019).