What was the "Checkers Speech" and why is it so important?

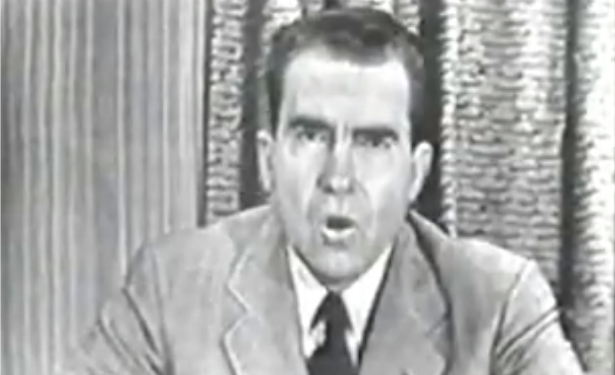

Fifty-six years ago yesterday, Republican VP candidate Richard Nixon went on TV to give what's known as the "Checkers Speech." Why does a speech named after a dog live on in our cultural subconscious more than half a century later? Let's find out.

Checkers, the speech

After practicing law and serving in the Navy during World War II, Nixon's political star rose quickly. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1946 and made a name for himself on the House Un-American Activities Committee. In 1950, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, where he continued to rage against Communism.

At the 1952 Republican National Convention, presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower chose Nixon as his running mate. Two months later, the New York Post ran the headline "Secret Rich Men's Trust Fund Keeps Nixon in Style Far Beyond His Salary" above an article claiming that campaign donors were buying influence with Nixon by keeping a secret fund stocked with cash for his personal expenses (some $140,000 in today's dollars). Outrage followed, and many Republicans urged Eisenhower to take Nixon off the ticket.

On September 23, Nixon appeared on national television from the El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood to defend himself. He said that the fund did exist, but the money wasn't secret, was strictly for covering campaign expenses, and that no contributor to the campaign fund ever received any special treatment. He produced the results of an independent audit of his finances and proceeded to reveal his financial history, touching on everything from money he made from speaking engagements, to the rent he paid for an apartment in Virginia the four years he was there ($80 a month!), to the $10 check he received from a supporter too young to vote that he promised never to cash.

He then challenged the Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson to also provide a history of his finances to the public and urged the public to contact the Republican National Committee and give their opinion on whether he should remain on the ticket or not.

The speech was a triumph. Nixon gained sympathy from both the public and from the powerful Republicans who had been calling for his head. Eisenhower summoned Nixon to West Virginia and greeted his running mate at the airport with, "Dick, you're my boy." Eisenhower and Nixon defeated the Democrats in November by seven million votes.

Checkers, the dog

There was one campaign donation that Nixon did admit to receiving and keeping for himself. Lou Carrol, a traveling salesman from Texas, had heard Nixon's wife mention during a radio interview how much the Nixon children wanted a dog. So he sent them a black and white spotted American Cocker Spaniel that Nixon's daughter Tricia named Checkers. Nixon admitted that the dog could become an issue, but said he didn't care. His kids loved the dog and no matter what his critics said, they were keeping it.

Checkers died in 1964 and is buried in Wantagh, New York, on Long Island's Bide-A-Wee Pet Cemetery.

The Checkers Legacy

It seems strange that we still remember Tricky Dick disclosing his financial situation in a speech named after a dog that's really only mentioned in passing. But the speech changed the way that politicians and the public interact. Nixon was perhaps one of the first to recognize the power that TV had in shaping a politician's image and the tube helped him in 1952 just as much as it hurt him during his debate with Kennedy in 1960.

The very idea of a politician making his case directly in front of the public—in their own living rooms, no less—was a novel concept at the time. And the combination of the studio set (a faux middle-class den) and Nixon's financial disclosures, which were both entrancing and agonizing to watch, closed the gap between him and the public even more.

The bit about Checkers, which take up less than a minute of airtime, is the clincher. By invoking the name of man's best friend, as cheesy as the speech may sound, Nixon helped give birth to a political landscape where personality is as important as policy, and where a person's vote hinges on which candidate they'd rather have a beer—or sit in a dog park—with.

Here's the speech:

If you've got a burning question that you'd like to see answered here, shoot me an email at flossymatt (at) gmail.com . Twitter users can also make nice with me and ask me questions there. Be sure to give me your name and location (and a link, if you want) so I can give you a little shout out.

|

some of the same columnists, some of the same radio commentators who are attacking me now and misrepresenting my position, were violently opposing me at the time I was after Alger Hiss. But I continued to fight because I knew I was right, and I can say to this great television and radio audience that I have no apologies to the American people for my part in putting Alger Hiss where he is today. And as far as this is concerned, I intend to continue to fight.

isn't qualified to be President of the United States. And I say that the only man who can lead us in this fight to rid the Government of both those who are Communists and those who have corrupted this Government is Eisenhower, because Eisenhower, you can be sure, recognizes the problem, and he knows how to deal with it.

: : The Miller Center ; Courtesy the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (National Archives and Records Administration) : Archives.gov : Audio enhanced by AmericanRhetoric.com : AI enhanced. Upscaled, cropped, color lightly tinted, and lighting modestly adjusted. Stereo widened, re-equalized, and normalized audio. : 9/7/24 : |

|

|

|

Help inform the discussion

- X (Twitter)

Presidential Speeches

September 23, 1952: "checkers" speech, about this speech.

Richard M. Nixon

September 23, 1952

As a candidate for vice president, Richard Nixon gives a televised address to the public after being accused of accepting illegal gifts. Nixon provides a detailed account of his and his family's finances to remove any suspicion. The title of the speech refers to the Nixon's family dog, Checkers, who was a gift but one which Nixon declines to return.

- Download Full Video

- Download Audio

My Fellow Americans: I come before you tonight as a candidate for the Vice Presidency and as a man whose honesty and integrity have been questioned. The usual political thing to do when charges are made against you is to either ignore them or to deny them without giving details. I believe we've had enough of that in the United States, particularly with the present Administration in Washington, D.C. To me the office of the Vice Presidency of the United States is a great office and I feel that the people have got to have confidence in the integrity of the men who run for that office and who might obtain it. I have a theory, too, that the best and only answer to a smear or to an honest misunderstanding of the facts is to tell the truth. And that's why I'm here tonight. I want to tell you my side of the case. I am sure that you have read the charge and you've heard that I, Senator Nixon, took $18,000 from a group of my supporters. Now, was that wrong? And let me say that it was wrong—I'm saying, incidentally, that it was wrong and not just illegal. Because it isn't a question of whether it was legal or illegal, that isn't enough. The question is, was it morally wrong? I say that it was morally wrong if any of that $18,000 went to Senator Nixon for my personal use. I say that it was morally wrong if it was secretly given and secretly handled. And I say that it was morally wrong if any of the contributors got special favors for the contributions that they made. And now to answer those questions let me say this: Not one cent of the $18,000 or any other money of that type ever went to me for my personal use. Every penny of it was used to pay for political expenses that I did not think should be charged to the taxpayers of the United States. It was not a secret fund. As a matter of fact, when I was on "Meet the Press," some of you may have seen it last Sunday—Peter Edson came up to me after the program and he said, "Dick, what about this fund we hear about?" And I said, "Well, there's no secret about it. Go out and see Dana Smith, who was the administrator of the fund." And I gave him his address, and I said that you will find that the purpose of the fund simply was to defray political expenses that I did not feel should be charged to the Government. And third, let me point out, and I want to make this particularly clear, that no contributor to this fund, no contributor to any of my campaign, has ever received any consideration that he would not have received as an ordinary constituent. I just don't believe in that and I can say that never, while I have been in the Senate of the United States, as far as the people that contributed to this fund are concerned, have I made a telephone call for them to an agency, or have I gone down to an agency in their behalf. And the records will show that, the records which are in the hands of the Administration. But then some of you will say and rightly, "Well, what did you use the fund for, Senator? Why did you have to have it?" Let me tell you in just a word how a Senate office operates. First of all, a Senator gets $15,000 a year in salary. He gets enough money to pay for one trip a year, a round trip that is, for himself and his family between his home and Washington, D.C. And then he gets an allowance to handle the people that work in his office, to handle his mail. And the allowance for my State of California is enough to hire thirteen people. And let me say, incidentally, that that allowance is not paid to the Senator—it's paid directly to the individuals that the Senator puts on his payroll, but all of these people and all of these allowances are for strictly official business. Business, for example, when a constituent writes in and wants you to go down to the Veterans Administration and get some information about his GI policy. Items of that type for example. But there are other expenses which are not covered by the Government. And I think I can best discuss those expenses by asking you some questions. Do you think that when I or any other Senator makes a political speech, has it printed, should charge the printing of that speech and the mailing of that speech to the taxpayers? Do you think, for example, when I or any other Senator makes a trip to his home state to make a purely political speech that the cost of that trip should be charged to the taxpayers? Do you think when a Senator makes political broadcasts or political television broadcasts, radio or television, that the expense of those broadcasts should be charged to the taxpayers? Well, I know what your answer is. It is the same answer that audiences give me whenever I discuss this particular problem. The answer is, "no." The taxpayers shouldn't be required to finance items which are not official business but which are primarily political business. But then the question arises, you say, "Well, how do you pay for l these and how can you do it legally?" And there are several ways that it can be done, incidentally, and that it is done legally in the United States Senate and in the Congress. The first way is to be a rich man. I don't happen to be a rich man so I couldn't use that one. Another way that is used is to put your wife on the payroll. Let me say, incidentally, my opponent, my opposite number for the Vice Presidency on the Democratic ticket, does have his wife on the payroll. And has had her on his payroll for the ten years—the past ten years. Now just let me say this. That's his business and I'm not critical of him for doing that. You will have to pass judgment on that particular point. But I have never done that for this reason. I have found that there are so many deserving stenographers and secretaries in Washington that needed the work that I just didn't feel it was right to put my wife on the payroll. My wife's sitting over here. She's a wonderful stenographer. She used to teach stenography and she used to teach shorthand in high school. That was when I met her. And I can tell you folks that she's worked many hours at night and many hours on Saturdays and Sundays in my office and she's done a fine job. And I'm proud to say tonight that in the six years I've been in the House and the Senate of the United States, Pat Nixon has never been on the Government payroll. There are other ways that these finances can be taken care of. Some who are lawyers, and I happen to be a lawyer, continue to practice law. But I haven't been able to do that. I'm so far away from California that I've been so busy with my Senatorial work that I have not engaged in any legal practice. And also as far as law practice is concerned, it seemed to me that the relationship between an attorney and the client was 80 personal that you couldn't possibly represent a man as an attorney and then have an unbiased view when he presented his case to you in the event that he had one before the Government. And so I felt that the best way to handle these necessary political expenses of getting my message to the American people and the speeches I made, the speeches that I had printed, for the most part, concerned this one message—of exposing this Administration, the communism in it, the corruption in it—the only way that I could do that was to accept the aid which people in my home state of California who contributed to my campaign and who continued to make these contributions after I was elected were glad to make. And let me say I am proud of the fact that not one of them has ever asked me for a special favor. I'm proud of the fact that not one of them has ever asked me to vote on a bill other than as my own conscience would dictate. And I am proud of the fact that the taxpayers by subterfuge or otherwise have never paid one dime for expenses which I thought were political and shouldn't be charged to the taxpayers. Let me say, incidentally, that some of you may say, "Well, that's all right, Senator; that's your explanation, but have you got any proof7" And I'd like to tell you this evening that just about an hour ago we received an independent audit of this entire fund. I suggested to Gov. Sherman Adams, who is the chief of staff of the Dwight Eisenhower campaign, that an independent audit and legal report be obtained. And I have that audit here in my hand. It's an audit made by the Price, Waterhouse & Co. firm, and the legal opinion by Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, lawyers in Los Angeles, the biggest law firm and incidentally one of the best ones in Los Angeles. I'm proud to be able to report to you tonight that this audit and this legal opinion is being forwarded to General Eisenhower. And I'd like to read to you the opinion that was prepared by Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and based on all the pertinent laws and statutes, together with the audit report prepared by the certified public accountants. It is our conclusion that Senator Nixon did not obtain any financial gain from the collection and disbursement of the fund by Dana Smith; that Senator Nixon did not violate any Federal or state law by reason of the operation of the fund, and that neither the portion of the fund paid by Dana Smith directly to third persons nor the portion paid to Senator Nixon to reimburse him for designated office expenses constituted income to the Senator which was either reportable or taxable as income under applicable tax laws. (signed) Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher by Alma H. Conway." Now that, my friends, is not Nixon speaking, but that's an independent audit which was requested because I want the American people to know all the facts and I'm not afraid of having independent people go in and check the facts, and that is exactly what they did. But then I realize that there are still some who may say, and rightly so, and let me say that I recognize that some will continue to smear regardless of what the truth may be, but that there has been understandably some honest misunderstanding on this matter, and there's some that will say: "Well, maybe you were able, Senator, to fake this thing. How can we believe what you say? After all, is there a possibility that maybe you got some sums in cash? Is there a possibility that you may have feathered your own nest?" And so now what I am going to do-and incidentally this is unprecedented in the history of American politics-I am going at this time to give this television and radio audience a complete financial history; everything I've earned; everything I've spent; everything I owe. And I want you to know the facts. I'll have to start early. I was born in 1913. Our family was one of modest circumstances and most of my early life was spent in a store out in East Whittier. It was a grocery store — one of those family enterprises. he only reason we were able to make it go was because my mother and dad had five boys and we all worked in the store. I worked my way through college and to a great extent through law school. And then, in 1940, probably the best thing that ever happened to me happened, I married Pat—who is sitting over here. We had a rather difficult time after we were married, like so many of the young couples who may be listening to us. I practiced law; she continued to teach school. Then in 1942 I went into the service. Let me say that my service record was not a particularly unusual one. I went to the South Pacific. I guess I'm entitled to a couple of battle stars. I got a couple of letters of commendation but I was just there when the bombs were falling and then I returned. I returned to the United States and in 1946 I ran for the Congress. When we came out of the war, Pat and I—Pat during the war ad worked as a stenographer and in a bank and as an economist for Government agency—and when we came out the total of our saving from both my law practice, her teaching and all the time that I as in the war—the total for that entire period was just a little less than $10,000. Every cent of that, incidentally, was in Government bonds. Well, that's where we start when I go into politics. Now what I've I earned since I went into politics? Well, here it is—I jotted it down, let me read the notes. First of all I've had my salary as a Congressman and as a Senator. Second, I have received a total in this past six years of $1600 from estates which were in my law firm the time that I severed my connection with it. And, incidentally, as I said before, I have not engaged in any legal practice and have not accepted any fees from business that came to the firm after I went into politics. I have made an average of approximately $1500 a year from nonpolitical speaking engagements and lectures. And then, fortunately, we've inherited a little money. Pat sold her interest in her father's estate for $3,000 and I inherited $l500 from my grandfather. We live rather modestly. For four years we lived in an apartment in Park Fairfax, in Alexandria, Va. The rent was $80 a month. And we saved for the time that we could buy a house. Now, that was what we took in. What did we do with this money? What do we have today to show for it? This will surprise you, Because it is so little, I suppose, as standards generally go, of people in public life. First of all, we've got a house in Washington which cost $41,000 and on which we owe $20,000. We have a house in Whittier, California, which cost $13,000 and on which we owe $3000. * My folks are living there at the present time. I have just $4,000 in life insurance, plus my G.I. policy which I've never been able to convert and which will run out in two years. I have no insurance whatever on Pat. I have no life insurance on our our youngsters, Patricia and Julie. I own a 1950 Oldsmobile car. We have our furniture. We have no stocks and bonds of any type. We have no interest of any kind, direct or indirect, in any business. Now, that's what we have. What do we owe? Well, in addition to the mortgage, the $20,000 mortgage on the house in Washington, the $10,000 one on the house in Whittier, I owe $4,500 to the Riggs Bank in Washington, D.C. with interest 4 1/2 per cent. I owe $3,500 to my parents and the interest on that loan which I pay regularly, because it's the part of the savings they made through the years they were working so hard, I pay regularly 4 per cent interest. And then I have a $500 loan which I have on my life insurance. Well, that's about it. That's what we have and that's what we owe. It isn't very much but Pat and I have the satisfaction that every dime that we've got is honestly ours. I should say this—that Pat doesn't have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat. And I always tell her that she'd look good in anything. One other thing I probably should tell you because if we don't they'll probably be saying this about me too, we did get something-a gift-after the election. A man down in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention the fact that our two youngsters would like to have a dog. And, believe it or not, the day before we left on this campaign trip we got a message from Union Station in Baltimore saying they had a package for us. We went down to get it. You know what it was. It was a little cocker spaniel dog in a crate that he'd sent all the way from Texas. Black and white spotted. And our little girl-Tricia, the 6-year old-named it Checkers. And you know, the kids, like all kids, love the dog and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we're gonna keep it. It isn't easy to come before a nation-wide audience and air your life as I've done. But I want to say some things before I conclude that I think most of you will agree on. Mr. Mitchell, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, made the statement that if a man couldn't afford to be in the United States Senate he shouldn't run for the Senate. And I just want to make my position clear. I don't agree with Mr. Mitchell when he says that only a rich man should serve his Government in the United States Senate or in the Congress. I don't believe that represents the thinking of the Democratic Party, and I know that it doesn't represent the thinking of the Republican Party. I believe that it's fine that a man like Governor Stevenson who inherited a fortune from his father can run for President. But I also feel that it's essential in this country of ours that a man of modest means can also run for President. Because, you know, remember Abraham Lincoln, you remember what he said: "God must have loved the common people—he made so many of them." And now I'm going to suggest some courses of conduct. First of all, you have read in the papers about other funds now. Mr. Stevenson, apparently, had a couple. One of them in which a group of business people paid and helped to supplement the salaries of state employees. Here is where the money went directly into their pockets. And I think that what Mr. Stevenson should do is come before the American people as I have, give the names of the people that have contributed to that fund; give the names of the people who put this money into their pockets at the same time that they were receiving money from their state government, and see what favors, if any, they ave out for that. I don't condemn Mr. Stevenson for what he did. But until the facts are in there is a doubt that will be raised. And as far as Mr. Sparkman is concerned, I would suggest the same thing. He's had his wife on the payroll. I don't condemn him for that. But I think that he should come before the American people and indicate what outside sources of income he has had. I would suggest that under the circumstances both Mr. parkman and Mr. Stevenson should come before the American people as I have and make a complete financial statement as to their financial history. And if they don't, it will be an admission that they have something to hide. And I think that you will agree with me. Because, folks, remember, a man that's to be President of the United States, a man that's to be Vice President of the United States must have the confidence of all the people. And that's why I'm doing what I'm doing, and that's why I suggest that Mr. Stevenson and Mr. Sparkman since they are under attack should do what I am doing. Now, let me say this: I know that this is not the last of the smears. In spite of my explanation tonight other smears will be made; others have been made in the past. And the purpose of the mears, I know, is this—to silence me, to make me let up. Well, they just don't know who they're dealing with. I'm going l tell you this: I remember in the dark days of the Hiss case some of the same columnists, some of the same radio commentators who are attacking me now and misrepresenting my position were violently opposing me at the time I was after Alger Hiss. But I continued the fight because I knew I was right. And I an say to this great television and radio audience that I have no pologies to the American people for my part in putting Alger Hiss vhere he is today. And as far as this is concerned, I intend to continue the fight. Why do I feel so deeply? Why do I feel that in spite of the mears, the misunderstandings, the necessity for a man to come up here and bare his soul as I have? Why is it necessary for me to continue this fight? And I want to tell you why. Because, you see, I love my country. And I think my country is in danger. And I think that the only man that can save America at this time is the man that's runing for President on my ticket — Dwight Eisenhower. You say, "Why do I think it's in danger?" and I say look at the record. Seven years of the Truman-Acheson Administration and that's happened? Six hundred million people lost to the Communists, and a war in Korea in which we have lost 117,000 American casualties. And I say to all of you that a policy that results in a loss of six hundred million people to the Communists and a war which costs us 117,000 American casualties isn't good enough for America. And I say that those in the State Department that made the mistakes which caused that war and which resulted in those losses should be kicked out of the State Department just as fast as we can get 'em out of there. And let me say that I know Mr. Stevenson won't do that. Because he defends the Truman policy and I know that Dwight Eisenhower will do that, and that he will give America the leadership that it needs. Take the problem of corruption. You've read about the mess in Washington. Mr. Stevenson can't clean it up because he was picked by the man, Truman, under whose Administration the mess was made. You wouldn't trust a man who made the mess to clean it up— that's Truman. And by the same token you can't trust the man who was picked by the man that made the mess to clean it up—and that's Stevenson. And so I say, Eisenhower, who owes nothing to Truman, nothing to the big city bosses, he is the man that can clean up the mess in Washington. Take Communism. I say that as far as that subject is concerned, the danger is great to America. In the Hiss case they got the secrets which enabled them to break the American secret State Department code. They got secrets in the atomic bomb case which enabled them to get the secret of the atomic bomb, five years before they would have gotten it by their own devices. And I say that any man who called the Alger Hiss case a "red herring" isn't fit to be President of the United States. I say that a man who like Mr. Stevenson has pooh-poohed and ridiculed the Communist threat in the United States—he said that they are phantoms among ourselves; he's accused us that have attempted to expose the Communists of looking for Communists in the Bureau of Fisheries and Wildlife—I say that a man who says that isn't qualified to be President of the United States. And I say that the only man who can lead us in this fight to rid the Government of both those who are Communists and those who have corrupted this Government is Eisenhower, because Eisenhower, you can be sure, recognizes the problem and he knows how to deal with it. Now let me say that, finally, this evening I want to read to you just briefly excerpts from a letter which I received, a letter which, after all this is over, no one can take away from us. It reads as follows: Dear Senator Nixon: Since I'm only 19 years of age I can't vote in this Presidential election but believe me if I could you and General Eisenhower would certainly get my vote. My husband is in the Fleet Marines in Korea. He's a corpsman on the front lines and we have a two-month-old son he's never seen. And I feel confident that with great Americans like you and General Eisenhower in the White House, lonely Americans like myself will be united with their loved ones now in Korea. I only pray to God that you won't be too late. Enclosed is a small check to help you in your campaign. Living on $85 a month it is all I can afford at present. But let me know what else I can do. Folks, it's a check for $10, and it's one that I will never cash. And just let me say this. We hear a lot about prosperity these days but I say, why can't we have prosperity built on peace rather than prosperity built on war? Why can't we have prosperity and an honest government in Washington, D.C., at the same time. Believe me, we can. And Eisenhower is the man that can lead this crusade to bring us that kind of prosperity. And, now, finally, I know that you wonder whether or not I am going to stay on the Republican ticket or resign. Let me say this: I don't believe that I ought to quit because I'm not a quitter. And, incidentally, Pat's not a quitter. After all, her name was Patricia Ryan and she was born on St. Patrick's Day, and you know the Irish never quit. But the decision, my friends, is not mine. I would do nothing that would harm the possibilities of Dwight Eisenhower to become President of the United States. And for that reason I am submitting to the Republican National Committee tonight through this television broadcast the decision which it is theirs to make. Let them decide whether my position on the ticket will help or hurt. And I am going to ask you to help them decide. Wire and write the Republican National Committee whether you think I should stay on or whether I should get off. And whatever their decision is, I will abide by it. But just let me say this last word. Regardless of what happens I'm going to continue this fight. I'm going to campaign up and down America until we drive the crooks and the Communists and those that defend them out of Washington. And remember, folks, Eisenhower is a great man. Believe me. He's a great man. And a vote for Eisenhower is a vote for what's good for America.

More Richard M. Nixon speeches

The Checkers Speech After 60 Years

The first-ever nationally televised address both saved and scarred young Richard Nixon, opening a new communications era and upending conventional political imagery.

Sunday marks the 60th anniversary of one of the 20th century's most significant public addresses -- Richard Nixon's much-praised, oft-scorned " Checkers Speech ." Delivered by then-Senator Nixon on the evening of September 23, 1952, in a dramatic attempt to answer charges that he abused a political expense fund, the half-hour address was the first American political speech to be televised live for a national audience and was watched or heard by some 60 million people. At stake was Nixon's place as General Dwight Eisenhower's running-mate on the Republican national ticket. The audience was the largest ever assembled.

Viewed through the prism of Nixon's roller-coaster career, the speech resonates today largely because of a single passage: the mention of Nixon's family dog, Checkers. Yet, a 1999 poll of leading communication scholars ranked the address as the sixth most important American speech of the 20th century -- close behind the soaring addresses of Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy and Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The "Checkers" speech wins this high rank for one stand-out reason: It marked the beginning of the television age in American politics. It also salvaged Nixon's career, plucking a last-second success from the jaws of abject humiliation, and profoundly shaped Nixon's personal and professional outlook, convincing him that television was a way to do an end-run around the press and the political "establishment."

The "Checkers Speech" foreshadowed the emergence of a new conservative populism in America, emphasizing appeals to social and cultural "identity" rather than economic interests.

Perhaps most interestingly, the address foreshadowed the emergence of a new conservative populism in America, emphasizing appeals to social and cultural "identity" rather than economic interests. The trend would ultimately end the domination of the New Deal Democratic coalition and create a base for Reagan Republicanism and its extended aftermath.

Nixon's began his speech that September evening by explaining the purposes of the fund that some of his supporters had set up after the 1950 election to help their new senator pay for continuing political expenses. The speech went on to emphasize the fund's record of prudent, transparent management. And Nixon ended the address by moving from defense to offense, describing the campaign against him as retribution for his recent effectiveness as an anti-communist crusader, including his role in exposing Alger Hiss as a likely Soviet spy, and delivering a blistering attack on the incumbent Truman administration.

It was, however, the middle passages of the speech, laying out his family's financial circumstances in excruciating -- and what Nixon accurately described as "unprecedented" -- detail that galvanized an instantaneous turnaround in popular opinion. It was the largest such swing ever. The discussion, later described as Nixon's "financial striptease," concluded with words that are still among his best-remembered -- touching a responsive chord among many millions, even as they lay bare his sense of embattled resentment:

That's what we have. And that's what we owe. It isn't very much. But Pat and I have the satisfaction that every dime that we have got is honestly ours. I should say this, that Pat doesn't have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat, and I always tell her she would look good in anything. One other thing I probably should tell you, because if I don't they will probably be saying this about me, too. We did get something, a gift, after the election.... You know what it was? It was a little cocker spaniel dog ... black and white, spotted, and our little girl Tricia, the six year old, named it Checkers. And you know, the kids, like all kids, loved the dog, and I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we're going to keep it.

When Whittaker Chambers published Witness , the mammoth memoir of his conversion from communism, he concluded by describing the Alger Hiss controversy -- in which he had played the central role as Hiss's accuser in 1948 -- as an epic social conflict. On one side were "the plain men and women of the nation" and on the other "those who affected to act, think and speak for them ... the 'best' people ... the enlightened and the powerful."

In Chambers' view, those who prosecuted Hiss, including Nixon (with his "somewhat martial Quakerism"), came mostly "from the wrong side of the railroad tracks." They were "humble people, strong in common sense, in common goodness, in common forgiveness, because all felt bowed together under the common weight of life."

The division between beleaguered commoners and a privileged elite had long been a familiar theme in American politics, normally used by Democrats to champion the cause of farmers and laborers against business-oriented Republicans. But Chambers' formulation recast the division in social and cultural terms, moving beyond pocketbook controversies to focus on "values," "lifestyles" and so-called "social issues." It heralded an emerging new strain of grassroots conservatism, and Nixon was quick to seize the rhetorical opportunity. Like Chambers, he saw mirrored in his personal struggles the dichotomy between sophisticated privilege and humble endeavor, and drew political and psychological sustenance from the support of what he would come to call "the silent majority."

When Witness was published in May of l952, Nixon reviewed it enthusiastically for The Saturday Review of Literature . The book topped The New York Times best seller list for three months that summer, and, on September 23, its outlook and some of its language made its way into Nixon's television address.

Nixon and his staff would always and only refer to it as "The Fund Speech," resenting the "Checkers" label as one that trivialized his remarks. Yet even supporters who came to consider the speech "an American masterpiece" would observe that it was less about his "Fund" as a symbol of alleged corruption than about "Checkers" as a symbol of middle American values.

Nixon, then 39, prepared the speech during a period he later described as the "hardest," "sharpest" and "most scarring" of his young life. His salvation, as he saw it, would lie with "millions of Americans," gathered around radios and television sets in homes across the land. "God must love the common people; He made so many of them," Chambers wrote in Witness , quoting Lincoln. Nixon's speech would highlight the same quotation.

The lasting accomplishment of the "Checkers" speech was not so much that Nixon explained his "Fund," nor even that he saved his candidacy. In the process of accomplishing those goals, he also took America's conventional political imagery and turned it upside down.

Scripps-Howard columnist Robert Ruark , saw the point immediately. "The sophisticates...sneer," he wrote just after the address, "but this came closer to humanizing the Republican Party than anything that has happened in my memory....Tuesday night the nation saw a little man, squirming his way out of a dilemma, and laying bare his most private hopes, fears, and liabilities. This time the common man was a Republican, for a change....[one who] suddenly placed the burden of old-style Republican aloofness on the Democrats."

If the Fund crisis presented Nixon with an extraordinary ordeal, it also handed him an extraordinary opportunity. New technology gave him the rapt attention of 60 million people; a recent firestorm of media criticism had positioned him as the ultimate underdog in an unprecedented drama. And yet the charges against him were entirely unproven.

Nixon's later, Watergate-logged history, is often read back into the 1952 context -- feeding a casual assumption that the Fund allegations must have had "something" to them. But neither journalistic investigation in that day nor historical research since have substantiated the charges that the money had been secretly gathered, improperly used or had purchased special influence.

In retrospect, some have even suggested that the crisis was somehow "manufactured," so weak was the case against Nixon. For one thing, private funds to cover travel and mailing expenses for elected officials were a common and widely accepted practice. And Nixon had taken pains to immunize his Fund from criticism.

As the Fund's organizer, Dana Smith, a Pasadena lawyer and Nixon's campaign treasurer, told prospective donors a year earlier, the "pool" of contributors would include only people "who have supported Dick from the start," preventing "second guessers" from making "any claim on the senator's interest." Contributions were limited to a maximum of $500, so that no one could think he was "entitled to special favors." The money, finally totaling $18,000, went into a regularly audited, openly-acknowledged trust account.

Rather than exemplifying the emerging, unhealthy influence of money in politics, as historian Roger Morris has suggested, the Nixon fund can plausibly be seen as an early attempt to respond to that problem.

When Nixon was first asked about the Fund on Sunday, September 14, he gave Smith's name and assumed the matter was ended. Nor is it surprising that his aides took the matter too casually at first, especially given their isolation on a campaign train in central California.

The first major Fund stories appeared on Thursday, September 18, and by Friday the candidate was responding to them at each whistle-stop, though initially with an attack on the motives of his critics that may have overshadowed his explanation of the Fund. An independent examination by prestigious legal and accounting firms was also set in motion -- and a list of contributors was prepared for public release.

Three factors allowed the Fund story to get out of control. The first was the inaccuracy of some journalists -- including their misuse of the word "secret." The New York Post headline screamed: "Secret Rich Men's Trust Fund Keeps Nixon in Style Far Beyond his Salary." It launched a tsunami of scandalized coverage.

A second factor in the escalating furor was the aggressiveness of political opponents (especially Democratic Party chairman Stephen Mitchell, who called immediately for Nixon's resignation). But the third and perhaps most important factor was the ambivalent reaction from General Eisenhower and his entourage, themselves traveling on a campaign train in the Midwest.

Press and public antagonism toward Nixon had mounted since his emergence as a national figure (though only a freshman congressman) during the Hiss controversy. The hot rhetoric of his successful 1950 Senate campaign in California against Helen Gahagan Douglas had sharply amplified his partisan image.

His oratorical fervor escalated as he became the GOP vice presidential nominee and party "point man," flaying the Democrats while Eisenhower stayed above the battle. As the contest heated up, he responded to his "hatchet-man" label by shouting: "If the record itself smears, let it smear. If the dry rot of corruption and communism ... can only be chopped out with a hatchet, then let's call for a hatchet."

Frustrated and frightened Democrats, after 20 years of White House control, were more than ready to seize on the Fund charges, given their relative inability to attack the heroic Eisenhower. The result, however, was that they rushed into a trap. As one historian has put it, the Democrats' handling of the Fund crisis was "criminally stupid." Interestingly, the one prominent Democrat who did not join in the frenzy was Adlai Stevenson, partly because his own private expense funds were so similar to Nixon's.

The reaction of Eisenhower's advisors was a puzzle to many. They had, after all, welcomed Nixon to the ticket two months earlier. Nixon had been an early Eisenhower supporter, helping ensure the general's narrow convention victory over Senator Robert Taft, the conservative hero.

Nonetheless, Eisenhower's closest associates were remarkably ready to believe the fund-related rumors. They had not known Nixon well beforehand -- some were put off by his occasional awkwardness in the urbane world of "drinks and jokes." They were mostly non-politicians, unaccustomed to campaign hyperbole and worried, too, that Nixon's anti-communist rhetoric linked him too closely to Senator Joseph McCarthy.

For the Eisenhower crew, moreover, the campaign was a moral crusade against "politics as usual," and stories about the Fund deeply unsettled them. The immediate charges, some warned, could be the tip of a larger iceberg.

When journalists on the Eisenhower train voted (rather unprofessionally) by a count of 40 to 2 for Nixon's removal, and when letters and telegrams began to run 3 to 1 against Nixon, the pressure on the general intensified. It culminated in an anti-Nixon editorial in the influential New York Herald Tribune , a strongly Republican newspaper published by Ike's good friend, Bill Robinson.

Eisenhower, characteristically, refused to be stampeded. But waiting itself exacted a high cost. And Ike's comment that his anti-corruption campaign must be "as clean as a hound's tooth" was widely regarded as a reproach, drowning out the senator's efforts to defend himself.

The hope -- and expectation -- of Eisenhower's advisors was that Nixon would simply withdraw from the ticket. California's arch-conservative senior senator, William Knowland, was asked to stand by as a substitute running mate. And Nixon seriously considered resigning. He would spare himself an enormous agony -- and avoid being remembered as the man who dragged down Eisenhower.

But two considerations argued the other way. First, resigning would give credence to the charges and hand his enemies a victory. The thought of yielding deeply offended him -- and it outraged his wife. Pat Nixon had opposed his accepting the vice presidential nomination, but her fierce sense of pride now came into play. Nixon must not "crawl," she urged in an anguished 2 a.m. conversation after they first learned of the devastating Herald-Tribune editorial.

Meanwhile, there were strong political arguments for hanging tough. While staying in the race meant risking blame for Ike's defeat, leaving the ticket would by no means ensure success; early polls showed the race to be a close contest. Nixon's resignation would offend conservatives and party regulars, and could drive away swing voters. And Nixon would still be the scapegoat.

Nixon decided to fight. He would agree, of course, to do the general's bidding, but he would not "draw up" his own "death warrant."

Remarkably, it was only on the night of Sunday, September 21st, that the two men spoke by phone. Ike, perhaps still half-hoping for Nixon's resignation, avoided words of direct support. He endorsed the idea of a televised effort to explain the Fund, an idea that had been championed and charted from the start by Robert Humphreys, media guru for the Republican National Committee. But Eisenhower refused to commit himself to a quick up or down decision, even after such an appeal.

Nixon reacted angrily. "This thing has got to be decided at the earliest possible time," he lectured the five star general. "...There comes a time in matters like these when you have to shit or get off the pot!"

In his 1961 book Six Crises , Nixon rephrased his retort to read, "You've got to fish or cut bait," but in his l978 memoirs he acknowledged the earthier language. It expressed not only his mounting frustration but also his sense, as he put it to Eisenhower, that "the great trouble here is the indecision."

Eisenhower's stance, on the other hand, clarified Nixon's challenge. As he later remembered: "Now everything was up to me."

But the challenge was daunting. New York Governor Thomas Dewey, instrumental in putting both "Ike and Dick" on the ticket, had warned Nixon that a mildly favorable response to a televised explanation would not be enough -- perhaps a 90 to 10 approval ratio might be required.

It soon became clear, as Humphreys had argued, that neither an interview program nor free time from the networks would do the job. Only by paying $75,000 for a half hour of prime time could Nixon maximize the audience and control the format.

It is remarkable, in retrospect, that so many tactical media decisions were made so well, despite limited time, the absence of precedents, and the enormous pressure. They included: paying for exposure rather than scrounging for free time; avoiding a coveted Monday night spot (after I Love Lucy) because it would allow insufficient time for preparation and for building the audience; selecting a Tuesday spot (following Milton Berle's popular show) rather than a later date which might dissipate the dramatic tension; building suspense by refusing to discuss the speech (not even to disclaim rumors that Nixon would be quitting); eliminating any studio audience (even press and staff watched from another room); and finally, selecting as a stage setting "a GI bedroom den," an intimate middle-American set, including a desk, a bookcase and an armchair for Pat Nixon.

Underlying these decisions was a concept still new to the television era, although it had characterized Franklin Roosevelt's fireside chats on radio. For this speech, the camera would not be a journalistic instrument, looking in upon an event and conveying that story to the public. For the first time, a national television audience would participate directly in a living room to living room encounter.

It would be Nixon, alone, with the people. The reporters and the politicians -- his own staff and Eisenhower's -- would all watch on television. And none of them would know what he was going to say.

Nixon flew to Los Angles from Portland, Oregon, where his train tour had ended, on Monday morning, the day before the address. He isolated himself for the next 30 hours at the Ambassador Hotel, sleeping a mere four hours, and working through a fog of personal despair that was becoming a major concern of his associates.

Working from preliminary notes made on airplane postcards, piecing in new information as it was delivered to him, Nixon sketched out the speech on legal pads, finishing one outline, then starting a new one.

Several rhetorical elements had already been "audience tested" on the campaign trail (Pat's Republican "cloth coat" for example, had first appeared in whistle-stop remarks a week earlier, a veiled reference to the so-called "mink-coat scandals" of the Truman years). And the Checkers passage itself was prompted, as Nixon later acknowledged, by Franklin Roosevelt's effective references to his "little dog Fala."

Nixon decided against using a manuscript -- it would forfeit the "spark of spontaniety" he valued so highly. He intended to prepare a third draft outline, and then, remarkably, to speak from memory.

This plan was upset, however, by a bizarre development. Just as Nixon finished the fifth and final page of his second outline on Tuesday afternoon, Thomas Dewey phoned, relaying Eisenhower's request that Nixon end the speech by submitting his resignation for Eisenhower's consideration.

Devastated by the request, Nixon stood his ground. "Just tell them that I haven't the slightest idea what I am going to do," he responded when Dewey pressed him. "And if they want to find out they'd better listen to the broadcast."

There was no time now for a third outline, no time to memorize, nor even to reconsider his path. Grabbing his five pages of notes, he left for the El Capitan theater twenty minutes away in Hollywood. When Ted Rogers, his television advisor, asked how he would close, Nixon replied, "I don't know..." Three minutes before airtime, he told his wife, "I just don't think I can go through with this." "Of course you can," she responded, taking his hand and leading him to the set.

The last page of his hurriedly scribbled notes read: "The decision must be made by Nat'l Committee. I will abide by their decision. You help them -- let them know either way...." And he stayed with that formulation, though it meant defying Eisenhower's request.

Perhaps because of his uncertainty, he mistimed his closing remarks and never gave an address for the Republican National Committee -- the only group with the legal power to change the party nominees once the convention had ended. At the moment, the error seemed fatal. "I loused it up, and I'm sorry. It was a flop" was the first thing he said after going off the air, throwing his notes to the floor and burying his head in the stage draperies. But even this slip turned to his advantage as supporters, unsure of where to send their responses, sent multiple copies in many directions.

By one count, there were some four million responses to the speech -- virtually all of them pro-Nixon. The National Committee alone reported 300,000 letters and telegrams signed by a million people. The count ran 350 to 1 in Nixon's favor.

The address not only touched a responsive nerve in the body politic, it seemed to open a national tear duct. Nixon's first hint that the speech was not "a flop," he said, came when he noticed tears in the eyes of the cameramen. Eisenhower's wife Mamie wept as the speech ended and even Bill Robinson (who sat with the Eisenhowers in Cleveland) found that his eyes were moist with emotion. In California, the man who removed Nixon's makeup told him, "There's never been a broadcast like it before." Ted Rogers reported that the theater switchboard was lit up "like a Christmas tree." "Thousands were in tears of emotion," wrote the Los Angeles Examiner , describing the effect as a "wildfire." A cowboy in Missoula, Montana, handed a $100 bill to a Nixon associate with the comment, "That's the best speech I ever heard." Back in Cleveland, some 15,000 tearful Republicans chanted "We Want Nixon" as they waited for Eisenhower to greet them.

But Eisenhower, who had watched the speech with cool detachment, remained non-committal. "I shall make up my mind ... as soon as I have had a chance to meet Senator Nixon face-to-face," he concluded, summoning Nixon to meet him the next evening in Wheeling, West Virginia.

When reports of Eisenhower's reaction reached Nixon amid a jubilant celebration back at the Ambassador Hotel, the Californian "blew his stack" as he later put it. "What more can he possibly want from me?" he asked his aide, Murray Chotiner, adding, "I'm not going to crawl on my hands and knees to him." And he dictated a telegram of resignation.

Chotiner tore up the telegram and convinced Nixon to go to Wheeling, provided he could be assured of Eisenhower's support in advance. But this response was interpreted as "insolent" by the General's camp, and for a few hours ragged nerves and wounded pride on both sides threatened to tear the ticket apart again.

In the end, Nixon went to Wheeling, persuaded by his old friend, journalist Bert Andrews, calling from the Eisenhower train. Nixon need not worry about the outcome, said Andrews: "The broadcast decided that. Eisenhower knows it as well as anyone else. But you must remember who he is... He is the boss of this outfit." Meanwhile, Eisenhower, impressed by the swelling public reaction, "shrugged and nodded" his assent to a quiet pre-meeting commitment.

By the time Nixon arrived in Wheeling, Eisenhower was "grinning all over," as he climbed aboard Nixon's plane to announce, "You're my boy." At a stadium rally, he announced the National Committee's 107 to 0 endorsement of his running mate. Nixon told the crowd of the two moments in his life when he was proudest to be an American: the first was looking down from a Manhattan window while Ike rode by in a postwar victory parade; the other had come that very day when he realized that "all you have got to do in this country of ours is just to tell the people the truth."

In fact, the lessons of the fund crisis were far more complex than that -- for Nixon and for America.

To begin with, there were significant political legacies, including a persistent wariness in the Eisenhower-Nixon relationship. The Republican Old Guard, on the other hand, rose even higher in Nixon's affections, including leading supporters such as Robert Taft, Joe McCarthy and Herbert Hoover. And while Nixon was bitter about colleagues who abandoned his cause, he carefully remembered those who stood with him that September, including two whose warm letters of support almost leap from the archival box as one explores the "Fund speech" files at the Nixon Presidential Library. One was from a young Minnesota lawyer named Warren Burger, whom President Nixon would later make Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Another came from a junior Michigan Congressman named Gerald Ford.

Nixon's response to the crisis that Autumn was a series of even rougher assaults on the opposition, rhetoric he would later describe as "unconscious overreacting" to the Fund attacks. But the overreaction would further magnify his partisan image.

Nixon's attitudes to the press also were transformed. He felt profoundly wronged by what he saw as the malevolence or sheer sloppiness of many reporters, and disillusioned by a pattern of journalistic indifference as he tried to get his own story out. Simply telling the truth had not been enough. Only a direct broadcast appeal over the heads of the press and the politicians had saved him.

When he asked his chief media assistant, James Bassett, how the press had reacted to the speech, Bassett would mark a new chapter in the life of the candidate -- and the country -- with his casual response: "It's not important now."

Above all, the Fund speech marked a turning point in the history of political communication. While more people witnessed the speech on radio than on television, it was the still-novel impact of the televised images that would long linger in public memory -- especially among the political classes. In one-half hour, television had become a central instrument of political leverage, and neither the traditional press nor traditional forms of power brokering would recover their previous influence.

When Walter Lippman described the Fund speech as one of the most "demeaning experiences" the country had been through, he was objecting less to Nixon's emotional appeals than to the fact that a leader like Eisenhower had been forced to count telegrams and telephone calls. "Mob rule" Lippmann called it.

With this new medium came new rules, new requirements that Nixon anticipated. Though Pat Nixon was shaken, for example, by the need to reveal personal financial data, her husband reconciled himself to living "in a fishbowl." While his proudly private parents cringed as he told of family struggles, their equally reserved son saw in such details a new way to build public rapport. Candidates' families -- not to mention their pets -- had been only occasionally visible in American politics; Pat Nixon's presence on the "Checkers" set was jarring and inexplicable to many. After "Checkers," families would become central participants in a new political dramaturgy.

Nixon's central challenge was not simply to address the immediate charges against him, but to inoculate himself against future ones. It was not enough to prove himself a non-liability -- he had to become a positive asset. He accomplished this goal by identifying himself not only with the circumstances of "ordinary" Americans, but also with their resentments of the fancy and facile elite. The attacks on him, in this context, became yet another symbol of privileged arrogance. And the apparent normalcy of his life convinced millions that he was truly "one of us."

To be sure, if many wept as this picture unfolded, many others scoffed; and their scorn would become another legacy of the crisis. "The "Checkers speech" would account, in significant measure, for a visceral sense of distaste and distrust among many of Nixon's permanent critics, forever suspicious of what they saw as his "maudlin" or "corny" appeals.

Nixon would later describe the Fund speech, like the Hiss affair, as an immediate triumph which sowed the seeds of future defeats. These important events persuaded his enemies to demonize him.

But the Fund crisis, in particular, was also important because of what it did to Nixon.

On the one hand, it put him into the first rank of American celebrities, a star shining now under its own power and not because of reflected light. And it reinforced his confidence that he could rescue himself from even the most perilous of difficulties by appealing directly, through television, to his silent majority.

The Checkers speech surely qualifies as one of the most successful rhetorical exercises in American history. Yet those six September days left deeper wounds than any of Nixon's political crises prior to Watergate. While he buoyantly created an informal club, "The Order of the Hound's Tooth," for those who had shared the ordeal, this was not a drama he was ever eager to recall. Pat Nixon simply refused ever to talk about the matter. The bitter legacy of the Fund experience would color Nixon's perspectives, and sometimes skew his judgments, for the rest of his career.

It is impossible to read or to watch the Fund speech six decades later without thinking of a later Nixon, and of later crises. But it is worth trying, nonetheless, to return to this speech much as 60 million Americans came to it in September of 1952, knowing very little about Richard Nixon except that he was a very young man with a very big problem, his back against the wall, making a last ditch effort to rescue his already embattled career.

About the Author

The New York Times

The learning network | sept. 23, 1952 | nixon’s ‘checkers’ speech.

Sept. 23, 1952 | Nixon’s ‘Checkers’ Speech

Historic Headlines

Learn about key events in history and their connections to today.

- Go to related On This Day page »

- Go to related post from our partner, findingDulcinea »

- See all Historic Headlines »

On Sept. 23, 1952, Richard Nixon, California senator and running mate of the Republican presidential candidate, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, gave a televised address defending his acceptance of more than $18,000 of secret — though legal — funds from political donors. The scandal threatened Mr. Nixon’s position on the ticket, as many Republicans called for General Eisenhower to choose a new running mate.

The Sept. 24 New York Times described the speech as “a half-hour talk that was partly personal, including a frank exposition of his finances, and partly an appeal for support of the Republican ticket.” With his wife, Patricia, seated beside him, Mr. Nixon spoke with “composure and assurance” as he emphasized that he lived a humble lifestyle and did not use the money for personal use.

The Times made no mention of what would become the most famous part of the speech: Nixon’s reference to his dog Checkers, given to the Nixon family by a Texas businessman. “And you know, the kids, like all kids, loved the dog, and I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we are going to keep it,” he declared.

The viewing public strongly supported Mr. Nixon as a result of the speech, and General Eisenhower decided to keep him on the ticket, which easily defeated the Democratic ticket in the election. The speech is generally credited with keeping Mr. Nixon on the career path that eventually led to his election as president in 1968.

His “Checkers” speech is one of the first examples of television’s power to broadcast a political candidate’s messages and control over public opinion. Mr. Nixon’s ability to make a personal, emotional appeal directly to the American people was revolutionary for the time.

Connect to Today:

In the 2008 election, Senator Barack Obama’s campaign used new technology more effectively than any previous major campaign. For example, Mr. Obama announced his running mate (Senator Joseph R. Biden Jr.) via text messages sent to those who had registered with his campaign. The tactic made supporters feel more connected to Mr. Obama and allowed the campaign to reach voters, particularly youth, much more inexpensively than traditional methods like advertisements, mailings and automated phone calls.

In a November 2008 blog post on Mr. Obama’s effective use of the Internet, Claire Cain Miller quoted the political consultant Joe Trippi, who said, “The tools changed between 2004 and 2008. Barack Obama won every single caucus state that matters, and he did it because of those tools, because he was able to move thousands of people to organize.”

Do you believe that technology can influence your support for political candidates? For example, are you more likely to watch a YouTube video of a candidate than a televised speech or commercial? Why? Which uses of technology do you think are most effective and which are least effective? Can you think of any new or different ways politicians might use technology?

Learn more about what happened in history on Sept. 23»

Comments are no longer being accepted.

What's Next

- This Day In History

- History Classics

- HISTORY Podcasts

- HISTORY Vault

- Link HISTORY on facebook

- Link HISTORY on twitter

- Link HISTORY on youtube

- Link HISTORY on instagram

- Link HISTORY on tiktok

Speeches & Audio

Richard nixon's checkers speech.

On September 23, 1952, as a candidate for vice president, Richard M. Nixon appears on national television to defend himself against reports that he had taken $18,000 from his supporters for his personal use. In his defense, he denies personal use of any funds, with one exception: the family dog, Checkers, which was given to Nixon as a gift.

Create a Profile to Add this show to your list!

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

It's All Politics

- Follow The Money

On This Day In 1952: Richard Nixon Gives Famous 'Checkers' Speech

Sept. 23, 1952 :

In a nationwide TV and radio broadcast, Sen. Richard Nixon of California, the Republican nominee for vice president, defends his financial dealings and ethics in an attempt to remain on the GOP ticket.

The so-called "Checkers" speech is a success; the following day, presidential nominee Dwight Eisenhower announces he will keep him as his running mate.

Today in Campaign History is a daily feature on Political Junkie .

- A Look Back in Politics

Richard Nixon, “Checkers” Speech, September 1952

Use this primary source text to explore key historical events.

Suggested Sequencing

- Use this primary source with The Nixon-Khrushchev Kitchen Debate Narrative and the Kennedy vs. Nixon: TV and Politics Lesson to have students analyze the impact television made on the perception of politicians in the 1950s and 1960s.

Introduction

Senator Richard M. Nixon, who had made a name for himself as a staunch opponent of domestic communism, was chosen as the vice presidential running mate for Dwight Eisenhower’s presidential campaign in 1952. When Nixon’s opponents raised doubts concerning a campaign fund and questioned gifts that Nixon had received, many thought Eisenhower would dump Nixon from the Republican ticket. Instead of giving up, Richard Nixon gave a televised speech to the nation to defend his integrity and character. Providing many details about his family’s modest lifestyle, Nixon stated that he only used the fund to reimburse legitimate travel and office expenses. Nixon mentioned one gift, a cocker spaniel puppy that his young daughter had named Checkers. The “Checkers” speech is remembered as one of the most important speeches of Nixon’s political career.

Sourcing Questions

- What advantages did Senator Richard M. Nixon bring to Dwight Eisenhower and the Republican ticket during the Presidential election of 1952?

- What issues were raised concerning Nixon’s integrity and character during the campaign that led him to give this televised speech?

| I have a theory, too, that the best and only answer to a smear or to an honest misunderstanding of the facts is to tell the truth. And that’s why I’m here tonight. I want to tell you my side of the case. I’m sure that you have read the charge, and you’ve heard it, that I, Senator Nixon, took 18,000 dollars from a group of my supporters. . . . | |

| . . . I say that it was morally wrong if it was secretly given and secretly handled. And I say that it was morally wrong if any of the contributors got special favors for the contributions that they made. | |

| And now to answer those questions let me say this: Not one cent of the 18,000 dollars or any other money of that type ever went to me for my personal use. Every penny of it was used to pay for political expenses that I did not think should be charged to the taxpayers of the United States. . . . | |

| (n): one of the people politicians have been elected to represent | And third, let me point out—and I want to make this particularly clear—that no contributor to this fund, no contributor to any of my campaigns, has ever received any consideration that he would not have received as an ordinary . I just don’t believe in that, and I can say that never, while I have been in the Senate of the United States, as far as the people that contributed to this fund are concerned, have I made a telephone call for them to an agency, or have I gone down to an agency in their behalf. And the records will show that, the records which are in the hands of the administration. . . . |

| Do you think that when I or any other Senator makes a political speech, has it printed, should charge the printing of that speech and the mailing of that speech to the taxpayers? Do you think, for example, when I or any other Senator makes a trip to his home State to make a purely political speech that the cost of that trip should be charged to the taxpayers? Do you think when a Senator makes political broadcasts or political television broadcasts, radio or television, that the expense of those broadcasts should be charged to the taxpayers? Well I know what your answer is. It’s the same answer that audiences give me whenever I discuss this particular problem: The answer is no. The taxpayers shouldn’t be required to finance items which are not official business but which are primarily political business.. . . | |

| (n): an official analysis of the financial records of an individual or an organization | I am proud to be able to report to you tonight that this and this legal opinion is being forwarded to General Eisenhower. And I’d like to read to you the opinion that was prepared by Gibson, Dunn, & Crutcher, and based on all the pertinent laws and statutes, together with the audit report prepared by the certified public accountants. Quote: |

| (signed) | |

| One other thing I probably should tell you, because if I don’t they’ll probably be saying this about me, too. We did get something, a gift, after the election. A man down in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention the fact that our two youngsters would like to have a dog. And believe it or not, the day before we left on this campaign trip we got a message from Union Station in Baltimore, saying they had a package for us. We went down to get it. You know what it was? It was a little cocker spaniel dog in a crate that he’d sent all the way from Texas, black and white, spotted. And our little girl Tricia, the six year old, named it “Checkers.” And you know, the kids, like all kids, love the dog, and I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it. . . . | |

| (n): something that completes or enhances something else when added to it | . . . First of all, you have read in the papers about other funds, now. Mr. Stevenson apparently had a couple—one of them in which a group of business people paid and helped to the salaries of State employees. Here is where the money went directly into their pockets, and I think that what Mr. Stevenson should do should be to come before the American people, as I have, give the names of the people that contributed to that fund, give the names of the people who put this money into their pockets at the same time that they were receiving money from their State government and see what favors, if any, they gave out for that.. . . |

| . . . I intend to continue to fight. | |

| Why do I feel so deeply? Why do I feel that in spite of the smears, the misunderstanding, the necessity for a man to come up here and bare his soul as I have—why is it necessary for me to continue this fight? And I want to tell you why. Because, you see, I love my country. And I think my country is in danger. And I think the only man that can save America at this time is the man that’s running for President, on my ticket—Dwight Eisenhower. |

Comprehension Questions

- What did Richard Nixon state was his main purpose for giving his televised speech?

- What was Nixon’s response to the charge of corruption?

- What was Nixon trying to demonstrate to the viewing voter when he stated that he called no government agency on behalf of any contributor to the fund?

- Why did Nixon pose these questions to the voting viewer? What point was he trying to prove to them?

- What purpose did Nixon have in discussing the findings of the audit of the fund?

- Why do you believe Nixon’s reference to the dog, Checkers, aided him in winning over numerous voters during this televised speech?

- How did Nixon help his cause of protecting his integrity and character by referring to the use of a fund by Democratic candidate Mr. Stevenson?

- Why do you think Nixon’s reference to Eisenhower in this paragraph may have aided him in gaining the support of the Republican party in keeping him on the Presidential ticket in 1952?

Historical Reasoning Questions

- Why do you believe this speech before the nation was so crucial in securing Richard Nixon’s place on the Republican presidential ticket in 1952?

- How did this speech potentially save Richard Nixon’s political career?

“Checkers” Speech https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/richardnixoncheckers.html

714.993.5075 [email protected]

Open 7 Days a Week 10am – 5pm

Checkers Speech

Sep 23, 1952 | Nixon Speeches , Nixon TV

[youtube https://youtu.be/JpWwgwytdzk]

September 23, 1952: President Nixon’s famous Checkers Speech.

'Checkers' Speech

Responding to allegations that he operated an illegal “slush” fund, Senator Nixon talked about his finances and denied any wrongdoing. He al… read more

Responding to allegations that he operated an illegal “slush” fund, Senator Nixon talked about his finances and denied any wrongdoing. He also outlined the case for electing Dwight Eisenhower and himself in the coming elections. The address is often referred to as the “Checkers speech” because he referred to his dog Checkers as the type of gift he received from supporters. Mrs. Nixon sat in a chair near her husband. close

Javascript must be enabled in order to access C-SPAN videos.

- Text type Closed Captioning Record People Graphical Timeline

- Filter by Speaker All Speakers Richard "Dick" M. Nixon

- Search this text

*This text was compiled from uncorrected Closed Captioning.

People in this video

Hosting Organization

- Republican National Committee Republican National Committee

Airing Details

- Nov 15, 1999 | 4:42pm EST | C-SPAN 1

- Nov 15, 1999 | 8:00pm EST | C-SPAN 2

- Nov 16, 1999 | 3:01am EST | C-SPAN 1

- Nov 16, 1999 | 6:01am EST | C-SPAN 2

Related Video

Eisenhower Press Conference

President Eisenhower talked to reporters during a news conference on March 30, 1955. He focused on foreign policy, the U…

Eisenhower 1956 Election Eve Program

This is a program produced for the 1956 re-election campaign of President Dwight Eisenhower. Aired on the eve of the gen…

Dwight Eisenhower: From General to President

President Eisenhower is one of the few presidents who was elected immediately after a long and prominant military career…

Eisenhower Presidency

U.S. Attorney General William Rogers under President Dwight Eisenhower offered his recollection on the general turned pr…

User Created Clips from This Video

An Excerpt of the Checkers Speech

User Clip: Nixon Checkers Gibson Dunn

User Clip: "Checkers" Speech

User Clip: Pat's coat

- Paired Texts

- Related Media

- Teacher Guide

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser.

- CommonLit is a nonprofit that has everything teachers and schools need for top-notch literacy instruction: a full-year ELA curriculum, benchmark assessments, and formative data. Browse Content Who We Are About

President Richard M. Nixon

36th President of the United States under the Constitution of 1787: January 20, 1969 – August 9, 1974

- Richard M. Nixon

Checkers Speech

- Inaugural Addresses

- Patricia Ryan Nixon

- The Forgotten First Ladies

- America's Four Republics

- Article The First

- Historic.us

- Feds Finally Agree: Samuel Huntington 1st USCA President

| Note: In this speech, in an attempt to save his Vice Presidency, Richard Nixon, counters critics who claim he took a $18,000 contribution and used it for personal expenses. In the speech his denies the accusation except that he admits that his family dog, Checkers, was a political gift. |

| Century Term | |||

| (1745-1783) | |||

| (1741- 1761) Deceased | |||

| (1745–1783) | |||

| (1747-1830) | |||

| (1747-1830) | |||

| (1731- 1770) Deceased | |||

| (1756-1802) | |||

| (1738/39–1794) | |||

| (1738/39–1794) | |||

| (1756-1820) | |||

| (1726-1812) | |||

| (1736-1808) | |||

| (1747-1790) | |||

| (1738-1796) | |||

| (1747-1830) | |||

| (1744-1812) | |||

| (1743-1818) | |||

| (1751-1807) |

| & | ||

| - | ||

| - | ||

| - |

No comments:

Post a comment.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.

Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)