You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Key Foreign Language Teaching Methods

How do you teach your foreign language students?

Consider for a moment the manners in which you teach reading , writing, listening, speaking, grammar and culture . Why do you use those methods?

In my experience, knowing the history of how your subject has been taught will help you understand your teaching methods.

It will also help you learn to select the best ones for your students at any given moment.

Read on for the most common foreign language teaching methods of today, as well as how to choose which ones to employ.

Grammar-translation

Audio-lingual, total physical response, communicative, task-based learning, community language learning, the silent way, functional-notional, other methods, how to choose a foreign language teaching method.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Those who’ve studied an ancient language like Latin or Sanskrit have likely used this method . It involves learning grammar rules, reading original texts and translating both from and into the target language.

You don’t really learn to speak—although, to be fair, it’s hard to practice speaking languages that have no remaining native speakers.

For the longest time, this approach was also commonly used for teaching modern foreign languages. Though it’s fallen out of favor, there are some benefits to it for occasional use.

With grammar-translation , you might give your students a brief passage in the target language, provide the new vocabulary and give them time to try translating. The reading might include a new verb tense, a new case or a complex grammatical construction.

When it occurs, speaking might only consist of a word or phrase and is typically in the context of completing the exercises. Explanations of the material are in the native language.

After the assignment, you could give students a series of translation sentences or a brief paragraph in the native language for them to translate into the target language as homework.

The direct method , also known as the natural approach, was a response to the grammar-translation method. Here, the emphasis is on the spoken language.

Based on observations of children learning their native tongues, this approach centers on listening and comprehension at the beginning of the language learning process.

Lessons are taught in the target language —in fact, the native language is strictly forbidden. A typical lesson might involve viewing pictures while the teacher repeats the vocabulary words, then listening to recordings of these words used in a comprehensible dialogue.

Once students have had time to listen and absorb the sounds of the target language, speaking is encouraged at all times, especially because grammar instruction isn’t taught explicitly.

Rather, students should learn grammar inductively. Allow them to use the language naturally, then gently correct mistakes and give praise to proper language usage. (Note that many have found this method of grammar instruction insufficient.)

Direct method activities might include pantomiming, word-picture association, question-answer patterns, dialogues and role playing.

The theory behind the audio-lingual approach is that repetition is the mother of all learning. This methodology emphasizes drill work in order to make answers to questions instinctive and automatic.

This approach gives highest priority to the spoken form of the target language. New information is first heard by students; written forms come only after extensive drilling. Classes are generally held in the target language.

An example of an audio-lingual activity is a substitution drill. The instructor might start with a basic sentence, such as “I see the ball.” Then they hold up a series of other photos for students to substitute for the word “ball.” These exercises are drilled into students until they get the pronunciations and rhythm right.

The audio-lingual approach borrows from the behaviorist school of psychology, so languages are taught through a system of reinforcement . Reinforcements are anything that makes students feel good about themselves or the situation—clapping, a sticker, etc.

Full immersion is difficult to achieve in a foreign language classroom—unless, of course, you’re teaching that language in a country where it’s spoken and your students are doing everything in the target language.

For example, ESL students have an immersion experience if they’re studying in an Anglophone country. In addition to studying English, they either work or study other subjects in English for the complete experience.

Attempts at this methodology can be seen in foreign language immersion schools, which are becoming popular in certain districts in the US. The challenge is that, as soon as students leave school, they are once again surrounded by the native language.

One way to get closer to the core of this method is to use an online language immersion program, such as FluentU . The authentic videos are made by and for native speakers and come with a multitude of learning tools.

Expert-vetted, interactive subtitles provide definitions, photo references, example sentences and more. Each lesson contains a quiz personalized to every individual student.

You can also import your own flashcard lists and assign tasks directly to learners with FluentU in order to encourage immersive learning outside of class.

Also known as TPR , this teaching method emphasizes aural comprehension. Gestures and movements play a vital role in this approach.

Children learning their native language hear lots of commands from adults: “Catch the ball,” “Pick up your toy,” “Drink your water.” TPR aims to teach learners a second language in the same manner with as little stress as possible.

The idea is that when students see movement and move themselves, their brains create more neural connections, which makes for more efficient language acquisition.

In a TPR-based classroom, students are therefore trained to respond to simple commands: stand up, sit down, close the door, open your book, etc.

The teacher might demonstrate what “jump” looks like, for example, and then ask students to perform the action themselves. Or, you might simply play Simon Says!

This style can later be expanded to storytelling , where students act out actions from an oral narrative, demonstrating their comprehension of the language.

The communicative approach is the most widely used and accepted approach to classroom-based foreign language teaching today.

It emphasizes the learner’s ability to communicate various functions, such as asking and answering questions, making requests, describing, narrating and comparing.

Task assignment and problem solving —two key components of critical thinking—are the means through which the communicative approach operates.

A communicative classroom includes activities where students can work out a problem or situation through narration or negotiation—composing a dialogue about when and where to eat dinner, for instance, or creating a story based on a series of pictures.

This helps them establish communicative competence and learn vocabulary and grammar in context. Error correction is de-emphasized so students can naturally develop accurate speech through frequent use. Language fluency comes through communicating in the language rather than by analyzing it.

Task-based learning is a refinement of the communicative approach and focuses on the completion of specific tasks through which language is taught and learned.

The purpose is for language learners to use the target language to complete a variety of assignments. They will acquire new structures, forms and vocabulary as they go. Typically, little error correction is provided.

In a task-based learning environment, three- to four-week segments are devoted to a specific topic, such as ecology, security, medicine, religion, youth culture, etc. Students learn about each topic step-by-step with a variety of resources.

Activities are similar to those found in a communicative classroom, but they’re always based around the theme. A unit often culminates in a final project such as a written report or presentation.

In this type of classroom, the teacher serves as a counselor rather than an instructor.

It’s called community language learning because the class learns together as one unit —not by listening to a lecture, but by interacting in the target language.

For instance, students might sit in a circle. You don’t need a set lesson since this approach is learner-led; the students will decide what they want to talk about.

Someone might say, “Hey, why don’t we talk about the weather?” The student will turn to the teacher ( standing outside the circle ) and ask for the translation of this statement. The teacher will provide the translation and ask the student to say it while guiding their pronunciation.

When the pronunciation is correct, the student will repeat the statement to the group. Another student might then say, “I had to wear three layers today!” And the process repeats.

These conversations are always recorded and then transcribed and mined for lesson continuations featuring grammar, vocabulary and subject-related content.

Proponents of this approach believe that teaching too much can sometimes get in the way of learning. It’s argued that students learn best when they discover rather than simply repeat what the teacher says.

By saying as little as possible, you’re encouraging students to do the talking themselves to figure out the language. This is seen as a creative, problem-solving process —an engaging cognitive challenge.

So how does one teach in silence ?

You’ll need to employ plenty of gestures and facial expressions to communicate with your students.

You can also use props. A common prop is Cuisenaire Rods —rods of different colors and lengths. Pick one up and say “rod.” Pick another, point at it and say “rod.” Repeat until students understand that “rod” refers to these objects.

Then, you could pick a green one and say “green rod.” With an economy of words, point to something else green and say, “green.” Repeat until students get that “green” refers to the color.

The functional-notional approach recognizes language as purposeful communication. That is, we use it because we need to communicate something.

Various parts of speech exist because we need them to express functions like informing, persuading, insinuating, agreeing, questioning, requesting, evaluating, etc. We also need to express notions (concepts) such as time, events, action, place, technology, process, emotion, etc.

Teachers using the functional-notional method must evaluate how the students will be using the language .

For example, very young kids need language skills to help them communicate with their parents and friends. Key social phrases like “thank you,” “please” or “may I borrow” are ideal here.

For business professionals, you might want to teach the formal forms of the target language, how to delegate tasks and how to vocally appreciate a job well done. Functions could include asking a question, expressing interest or negotiating a deal. Notions could be prices, quality or quantity.

You can teach grammar and sentence patterns directly, but they’re always subsumed by the purpose for which the language will be used.

A student who wants to learn with the reading method probably never intends to interact with native speakers in the target language.

Perhaps they’re a graduate student who simply needs to read scholarly articles. Maybe they’re a culinary student who only wants to understand the French techniques in her cookbook.

Whoever it is, these students only require one linguistic skill: reading comprehension.

Do away with pronunciation and dialogues. No need to practice listening or speaking, or even much (if any) writing.

With the reading approach, simply help your students build their vocabulary. They’ll likely need a lot of specialized words in a specific field, though they’ll also need to know elements like conjunctions and negation—enough grammar to make it through a standard article in their field.

These approaches are not necessarily as common in the classroom setting but deserve a mention nonetheless:

- Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL): A number of commercial products ( Pimsleur , Rosetta Stone ) and online products ( Duolingo , Babbel ) use the CALL method. With careful planning, you can likely employ some in the classroom as well.

- Cognitive-code: Developed in response to the audio-lingual method , this approach requires essential language structures to be explicitly laid out in examples (dialogues, readings) by the teacher, with lots of opportunities for students to practice .

- Suggestopedia: The idea here is that the more relaxed and comfortable students feel, the more open they are to learning , which therefore makes language acquisition easier.

Now that you know a number of methodologies and how to use them in the classroom, how do you choose the best?

You should always try to choose the methods and approaches that are most effective for your students. After all, our job as teachers is to help our students to learn in the best way for them— not for us or for researchers or for administrators.

So, the best teachers choose the best methodology and the best approach for each lesson or activity. They aren’t wedded to any particular methodology but rather use principled eclecticism:

- Ever taught a grammatical construction that only appears in written form? Had your students practice it by writing? Then you’ve used the grammar-translation method.

- Ever talked to your students in question/answer form, hoping they’d pick up the grammar point? Then you’ve used the direct method.

- Every repeatedly drilled grammatical endings, or numbers, or months, perhaps before showing them to your students? Then you’ve used the audio-lingual method.

- Ever played Simon Says? Or given your students commands to open their textbook to a certain page? Then you’ve used the total physical response method.

- Ever written a thematic unit on a topic not covered by the textbook, incorporating all four skills and culminating in a final assignment? Then you’ve used task-based learning.

If you’ve already done all of these, then you’re already practicing principled eclecticism!

The point is: The best teachers make use of all possible approaches at the appropriate time, for the appropriate activities and for those students whose learning styles require that approach.

The ultimate goal is to choose the foreign language teaching methods that best fit your students, not to force them to adhere to a particular or method.

Remember: Teaching is always about our students! You got this!

Related posts:

Enter your e-mail address to get your free pdf.

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

ESL Speaking

Games + Activities to Try Out Today!

in Activities for Adults · Activities for Kids · ESL Speaking Resources

Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: CLT, TPR

Teaching a foreign language can be a challenging but rewarding job that opens up entirely new paths of communication to students. It’s beneficial for teachers to have knowledge of the many different language learning techniques including ESL teaching methods so they can be flexible in their instruction methods, adapting them when needed.

Keep on reading for all the details you need to know about the most popular foreign language teaching methods. Some of the ESL pedagogy ideas covered are the communicative approach, total physical response, the direct method, task-based language learning, suggestopedia, grammar-translation, the audio-lingual approach and more.

Language teaching methods

Most Popular Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

Here’s a helpful rundown of the most common language teaching methods and ESL teaching methods. You may also want to take a look at this: Foreign language teaching philosophies .

#1: The Direct Method

In the direct method ESL, all teaching occurs in the target language, encouraging the learner to think in that language. The learner does not practice translation or use their native language in the classroom. Practitioners of this method believe that learners should experience a second language without any interference from their native tongue.

Instructors do not stress rigid grammar rules but teach it indirectly through induction. This means that learners figure out grammar rules on their own by practicing the language. The goal for students is to develop connections between experience and language. They do this by concentrating on good pronunciation and the development of oral skills.

This method improves understanding, fluency , reading, and listening skills in our students. Standard techniques are question and answer, conversation, reading aloud, writing, and student self-correction for this language learning method. Learn more about this method of foreign language teaching in this video:

Please enable JavaScript

#2: Grammar-Translation

With this method, the student learns primarily by translating to and from the target language. Instructors encourage the learner to memorize grammar rules and vocabulary lists. There is little or no focus on speaking and listening. Teachers conduct classes in the student’s native language with this ESL teaching method.

This method’s two primary goals are to progress the learner’s reading ability to understand literature in the second language and promote the learner’s overall intellectual development. Grammar drills are a common approach. Another popular activity is translation exercises that emphasize the form of the writing instead of the content.

Although the grammar-translation approach was one of the most popular language teaching methods in the past, it has significant drawbacks that have caused it to fall out of favour in modern schools . Principally, students often have trouble conversing in the second language because they receive no instruction in oral skills.

#3: Audio-Lingual

The audio-lingual approach encourages students to develop habits that support language learning. Students learn primarily through pattern drills, particularly dialogues, which the teacher uses to help students practice and memorize the language. These dialogues follow standard configurations of communication.

There are four types of dialogues utilized in this method:

- Repetition, in which the student repeats the teacher’s statement exactly

- Inflection, where one of the words appears in a different form from the previous sentence (for example, a word may change from the singular to the plural)

- Replacement, which involves one word being replaced with another while the sentence construction remains the same

- Restatement, where the learner rephrases the teacher’s statement

This technique’s name comes from the order it uses to teach language skills. It starts with listening and speaking, followed by reading and writing, meaning that it emphasizes hearing and speaking the language before experiencing its written form. Because of this, teachers use only the target language in the classroom with this TESOL method.

Many of the current online language learning apps and programs closely follow the audio-lingual language teaching approach. It is a nice option for language learning remotely and/or alone, even though it’s an older ESL teaching method.

#4: Structural Approach

Proponents of the structural approach understand language as a set of grammatical rules that should be learned one at a time in a specific order. It focuses on mastering these structures, building one skill on top of another, instead of memorizing vocabulary. This is similar to how young children learn a new language naturally.

An example of the structural approach is teaching the present tense of a verb, like “to be,” before progressing to more advanced verb tenses, like the present continuous tense that uses “to be” as an auxiliary.

The structural approach teaches all four central language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. It’s a technique that teachers can implement with many other language teaching methods.

Most ESL textbooks take this approach into account. The easier-to-grasp grammatical concepts are taught before the more difficult ones. This is one of the modern language teaching methods.

Most popular methods and approaches and language teaching

#5: Total Physical Response (TPR)

The total physical response method highlights aural comprehension by allowing the learner to respond to basic commands, like “open the door” or “sit down.” It combines language and physical movements for a comprehensive learning experience.

In an ordinary TPR class, the teacher would give verbal commands in the target language with a physical movement. The student would respond by following the command with a physical action of their own. It helps students actively connect meaning to the language and passively recognize the language’s structure.

Many instructors use TPR alongside other methods of language learning. While TPR can help learners of all ages, it is used most often with young students and beginners. It’s a nice option for an English teaching method to use alongside some of the other ones on this list.

An example of a game that could fall under TPR is Simon Says. Or, do the following as a simple review activity. After teaching classroom vocabulary, or prepositions, instruct students to do the following:

- Pick up your pencil.

- Stand behind someone.

- Put your water bottle under your chair.

Are you on your feet all day teaching young learners? Consider picking up some of these teacher shoes .

#6: Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

These days, CLT is by far one of the most popular approaches and methods in language teaching. Keep reading to find out more about it.

This method stresses interaction and communication to teach a second language effectively. Students participate in everyday situations they are likely to encounter in the target language. For example, learners may practice introductory conversations, offering suggestions, making invitations, complaining, or expressing time or location.

Instructors also incorporate learning topics outside of conventional grammar so that students develop the ability to respond in diverse situations.

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Bolen, Jackie (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 301 Pages - 12/21/2022 (Publication Date)

CLT teachers focus on being facilitators rather than straightforward instructors. Doing so helps students achieve CLT’s primary goal, learning to communicate in the target language instead of emphasizing the mastery of grammar.

Role-play , interviews, group work, and opinion sharing are popular activities practiced in communicative language teaching, along with games like scavenger hunts and information gap exercises that promote student interaction.

Most modern-day ESL teaching textbooks like Four Corners, Smart Choice, or Touchstone are heavy on communicative activities.

#7: Natural Approach

This approach aims to mimic natural language learning with a focus on communication and instruction through exposure. It de-emphasizes formal grammar training. Instead, instructors concentrate on creating a stress-free environment and avoiding forced language production from students.

Teachers also do not explicitly correct student mistakes. The goal is to reduce student anxiety and encourage them to engage with the second language spontaneously.

Classroom procedures commonly used in the natural approach are problem-solving activities, learning games , affective-humanistic tasks that involve the students’ own ideas, and content practices that synthesize various subject matter, like culture.

#8: Task-Based Language Teaching (TBL)

With this method, students complete real-world tasks using their target language. This technique encourages fluency by boosting the learner’s confidence with each task accomplished and reducing direct mistake correction.

Tasks fall under three categories:

- Information gap, or activities that involve the transfer of information from one person, place, or form to another.

- Reasoning gap tasks that ask a student to discover new knowledge from a given set of information using inference, reasoning, perception, and deduction.

- Opinion gap activities, in which students react to a particular situation by expressing their feelings or opinions.

Popular classroom tasks practiced in task-based learning include presentations on an assigned topic and conducting interviews with peers or adults in the target language. Or, having students work together to make a poster and then do a short presentation about a current event. These are just a couple of examples and there are literally thousands of things you can do in the classroom. In terms of ESL pedagogy, this is one of the most popular modern language teaching methods.

It’s considered to be a modern method of teaching English. I personally try to do at least 1-2 task-based projects in all my classes each semester. It’s a nice change of pace from my usually very communicative-focused activities.

One huge advantage of TBL is that students have some degree of freedom to learn the language they want to learn. Also, they can learn some self-reflection and teamwork skills as well.

#9: Suggestopedia Language Learning Method

This approach and method in language teaching was developed in the 1970s by psychotherapist Georgi Lozanov. It is sometimes also known as the positive suggestion method but it later became sometimes known as desuggestopedia.

Apart from using physical surroundings and a good classroom atmosphere to make students feel comfortable, here are some of the main tenants of this second language teaching method:

- Deciphering, where the teacher introduces new grammar and vocabulary.

- Concert sessions, where the teacher reads a text and the students follow along with music in the background. This can be both active and passive.

- Elaboration where students finish what they’ve learned with dramas, songs, or games.

- Introduction in which the teacher introduces new things in a playful manner.

- Production, where students speak and interact without correction or interruption.

TESOL methods and approaches

#10: The Silent Way

The silent way is an interesting ESL teaching method that isn’t that common but it does have some solid footing. After all, the goal in most language classes is to make them as student-centred as possible.

In the Silent Way, the teacher talks as little as possible, with the idea that students learn best when discovering things on their own. Learners are encouraged to be independent and to discover and figure out language on their own.

Instead of talking, the teacher uses gestures and facial expressions to communicate, as well as props, including the famous Cuisenaire Rods. These are rods of different colours and lengths.

Although it’s not practical to teach an entire course using the silent way, it does certainly have some value as a language teaching approach to remind teachers to talk less and get students talking more!

#11: Functional-Notional Approach

This English teaching method first of all recognizes that language is purposeful communication. The reason people talk is that they want to communicate something to someone else.

Parts of speech like nouns and verbs exist to express language functions and notions. People speak to inform, agree, question, persuade, evaluate, and perform various other functions. Language is also used to talk about concepts or notions like time, events, places, etc.

The role of the teacher in this second language teaching method is to evaluate how students will use the language. This will serve as a guide for what should be taught in class. Teaching specific grammar patterns or vocabulary sets does play a role but the purpose for which students need to know these things should always be kept in mind with the functional-notional Approach to English teaching.

#12: The Bilingual Method

The bilingual method uses two languages in the classroom, the mother tongue and the target language. The mother tongue is briefly used for grammar and vocabulary explanations. Then, the rest of the class is conducted in English. Check out this video for some of the pros and cons of this method:

#13: The Test Teach Test Approach (TTT)

This style of language teaching is ideal for directly targeting students’ needs. It’s best for intermediate and advanced learners. Definitely don’t use it for total beginners!

There are three stages:

- A test or task of some kind that requires students to use the target language.

- Explicit teaching or focus on accuracy with controlled practice exercises.

- Another test or task is to see if students have improved in their use of the target language.

Want to give it a try? Find out what you need to know here:

Test Teach Test TTT .

#14: Community Language Learning

In Community Language Learning, the class is considered to be one unit. They learn together. In this style of class, the teacher is not a lecturer but is more of a counsellor or guide.

In general, there is no set lesson for the day. Instead, students decide what they want to talk about. They sit in the a circle, and decide on what they want to talk about. They may ask the teacher for a translation or for advice on pronunciation or how to say something.

The conversations are recorded, and then transcribed. Students and teacher can analyze the grammar and vocabulary, as well as subject related content.

While community language learning may not comprehensively cover the English language, students will be learning what they want to learn. It’s also student-centred to the max. It’s perhaps a nice change of pace from the usual teacher-led classes, but it’s not often seen these days as the only method of teaching a class.M

#15: The Situational Approach

This approach loosely falls under the behaviourism view of language as habit formation. The situational approach to teaching English was popular in England, starting in the 1930s. Find out more about it:

Language Teaching Approaches FAQs

There are a number of common questions that people have about second or foreign language teaching and learning. Here are the answers to some of the most popular ones.

What is language teaching approaches?

A language teaching approach is a way of thinking about teaching and learning. An approach produces methods, which is the way of teaching something, in this case, a second or foreign language using techniques or activities.

What are method and approach?

Method and approach are similar but there are some key differences. An approach is the way of dealing with something while a method involves the process or steps taken to handle the issue or task.

What is presentation practice production?

How many approaches are there in language learning.

Throughout history, there have been just over 30 popular approaches to language learning. However, there are around 10 that are most widely known including task-based learning, the communicative approach, grammar-translation and the audio-lingual approach. These days, the communicative approach is all the rage.

What is the best method of English language teaching?

It’s difficult to choose the best single approach or method for English language teaching as the one used depends on the age and level of the students as well as the material being taught. Most teachers find that a mix of the communicative approach, audio-lingual approach and task-based teaching works well in most cases.

What is micro teaching?

What are the most effective methods of learning a language.

The most effective methods for learning a language really depends on the person, but in general, here are some of the best options: total immersion, the communicative approach, extensive reading, extensive listening, and spaced repetition.

The Modern Methods of Teaching English

There are several modern methods of teaching English that focus on engaging students and making learning more interactive and effective. Some of these methods include:

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

This approach emphasizes communication and interaction as the main goals of language learning. It focuses on real-life situations and encourages students to use English in meaningful contexts.

Task-Based Learning (TBL)

TBL involves designing activities or tasks that require students to use English to complete a specific goal or objective. This approach helps students develop language skills while focusing on the task at hand.

Technology-Enhanced Learning

Using technology such as computers, tablets, and smartphones can make learning more engaging and interactive. Online resources, apps, and educational games can be used to supplement traditional teaching methods.

Flipped Classroom

In a flipped classroom, students learn new material at home through videos or online resources, and then use class time for activities, discussions, and practice exercises. This approach allows for more individualized learning and interaction in the classroom.

Project-Based Learning (PBL)

PBL involves students working on projects or tasks that require them to use English in a real-world context. This approach helps students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills while improving their language abilities.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)

CLIL involves teaching subjects such as science or history in English, rather than teaching English as a separate subject. This approach helps students learn English while also learning about other subjects.

Gamification

Using game elements such as points, badges, and leaderboards can make learning English more fun and engaging. Educational games can help students practice language skills in a playful and interactive way.

These modern methods of teaching English focus on making learning more student-centered, interactive, and engaging, leading to better outcomes for students.

Have your say about Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

What’s your top pick for a language teaching method? Is it one of the options from this list or do you have another one that you’d like to mention? Leave a comment below and let us know what you think. We’d love to hear from you. And whatever approach or method you use, you’ll want to check out these top 1o tips for new English teachers .

Also, be sure to give this article a share on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter. It’ll help other busy teachers, like yourself, find this useful information about approaches and methods in language teaching and learning.

Last update on 2024-08-04 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

About Jackie

Jackie Bolen has been teaching English for more than 20 years to students in South Korea and Canada. She's taught all ages, levels and kinds of TEFL classes. She holds an MA degree, along with the Celta and Delta English teaching certifications.

Jackie is the author of more than 100 books for English teachers and English learners, including 101 ESL Activities for Teenagers and Adults , Great Debates for ESL/EFL , and 1001 English Expressions and Phrases . She loves to share her ESL games, activities, teaching tips, and more with other teachers throughout the world.

You can find her on social media at: YouTube Facebook Pinterest Instagram

This is wonderful, I have learned a lot!

You’re welcome!

What year did you publish this please?

Recently! Only a few months ago.

Wonderful! Thank you for sharing such useful information. I have learned a lot from them. Thank you!

I am so grateful. Thanks for sharing your kmowledge.

Hi thank you so much for this amazing article. I just wanted to confirm/ask is PPP one of the methods of teaching ESL if so was there a reason it wasn’t included in the article(outdated, not effective etc.?).

PPP is more of a subset of these other ones and not an approach or method in itself.

Good explanation, understandable and clear. Congratulations

That’s good, very short but clear…👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

I meant the naturalistic approach

This is amazing! Thank you for writing this article, it helped me a lot. I hoped this will reach more people so I will definitely recommend this to others.

Thank you, sir! I just used this article in my PPT presentation at my Post Grad School. More articles from you!

I think this useful because it is teaching me a lot about english. Thank you bro! 😀👍

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Our Top-Seller

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

More ESL Activities

Weekend plans (easy english dialogue for beginners), ordering sushi (easy english dialogue for beginners), feeling under the weather: english dialogue & practice questions, meeting someone new dialogue (for english learners), about, contact, privacy policy.

Jackie Bolen has been talking ESL speaking since 2014 and the goal is to bring you the best recommendations for English conversation games, activities, lesson plans and more. It’s your go-to source for everything TEFL!

About and Contact for ESL Speaking .

Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Email: [email protected]

Address: 2436 Kelly Ave, Port Coquitlam, Canada

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Teaching Writing to Second Language Learners: Insights from Theory and Research

Related Papers

International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies [IJELS]

This paper briefly reviews the literature on writing skill in second language. It commences with a discussion on the importance of writing and its special characteristics. Then, it gives a brief account of the reasons for the weakness of students' writing skill as well as addressing some of the most important topics in L2 writing studies ranging from disciplinary to interdisciplinary to metadisciplinary field of inquiry. In addition, it presents a historical sketch of L2 writing studies, consisting of approaches to teaching writing including behavioristic and contrastive rhetoric as well as discussing approaches to the study of writing including product-oriented, process-oriented, and post-process ones. It also introduces different types of feedback in writing consisting of peer feedback, conferences as feedback, teachers' comments as feedback, and self-monitoring. Finally, it deals with holistic vs. analytic dichotomy in administration of writing assessment.

Hacer Hande Uysal

Abbas Zare-ee

Studies in Second Language Acquisition

John Hedgcock

Aseel Kanakri-Ghashmari

This article discusses the academic writing challenges and needs of English as second language (ESL) students. Specifically, it aims at in-depth understanding of the needs of ESL students in academic environments with regards to academic writing across the disciplines. It also elaborates on the role of genre study (theory) in helping ESL students overcome their challenges and meet the requirements of their academic disciplines. This article calls for the importance of understanding ESL student' needs and challenges which can help in developing better instruction, dictate the curriculum, and provide a systematic support for these students to succeed and complete their degrees.

The Modern Language Journal

Melinda Reichelt

Svjetlana Curcic

Guadalupe Valdes

Learning and Instruction

Alasdair Archibald

Writing is a complex activity whose components and sub-components involve action on a number of levels. It is multifaceted, requiring proficiency in several areas of skill and knowledge that make up writing only when taken together. Research into writing has mirrored this complexity and has developed concurrently in a number of disciplines — in psychology and the cognitive sciences, text linguistics and pragmatics, applied linguistics and first and second language education.This special issue of Learning and Instruction is a collection of four papers that represent different aspects of current research into writing in a second language. They do not cover the full range of research into this area of writing, but serve as examples of the depth and breadth of study in this one particular part of the field. They are introduced here within the context of a discussion of current interests in writing research and each of the papers will be presented within the research area into which it most reasonably fits.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Investigating the L2 Writing Strategies Used by Skillful English Students

Syaadiah Arifin

Nizar Ibrahim

Imelda Hermilinda Abas

Michael Khirallah

Language learning and language teaching

Heidi Byrnes

Neslişah Güneş

Jackie Ridley

Dr.Huma Zaidi

Lisya Seloni

Sajjad Pouromid

Studies in Writing

Marie-Laure Barbier , Sarah Ransdell

Journal of Second Language Writing

Melinda Reichelt , Tony Silva

In P. Matsuda &R. Manchon (eds.) Handbook of Second and Foreign Language Writing. Mouton pp 45-64.

Journal of School of Foreign Studies, Nagoya University of Foreign Studies

Anthony Brian Gallagher

English Journal

Margo DelliCarpini

IJES, International Journal of English Studies

Monique Bournot-Trites

Mehdi Riazi

Dr. Prudhvi Raju

Porta Linguarum

Pieter de Haan

hicham zyad

Shehla Khan

Applied Linguistics

Saeideh Ahangari

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

PERSPECTIVE article

Review of effective methods of teaching a foreign language to university students in the framework of online distance learning: international experience.

- 1 Sibai Institute (Branch), Bashkir State University, Sibai, Russia

- 2 Bashkir State University, Ufa, Russia

- 3 Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia

- 4 Kolomna Institute (Branch) of Moscow Polytechnic University, Kolomna, Russia

The research goal is to analyze the existing and most frequently used methods and competency-based approaches to distance learning of a foreign language. The tasks are formulated to achieve the goal. They involve classifying the methods of foreign language teaching based on the competency approach and identifying the effective methods. The methodological basis of this research includes methods of analyzing the practical experience of foreign language teaching based on a competency-based approach, synthesis of national and international experience, comparison of national models of the language environment, and generalization of sociological data. As a result of the conducted research, it has been revealed that among various methods, approaches related to information and communication technologies [ICT] are utilized most often. We believe that when teachers conduct courses using synchronous computer-mediated communication [SCMC] tools or platforms, students should be given opportunities to express their opinions. Most teachers recognize the creation of instructional videos as the most effective. According to the students, this type of activity also has the greatest learning effect and stimulates creativity. The scientific novelty of the research is the study of foreign language teaching methods based on a competency-based approach within the framework of online distance learning and the relationship of all interested parties, in other words, teachers, students, and educational institutions.

1. Introduction

Global integrative trends, expansion of intercultural interaction, and rapid social development contribute to mastering one or more foreign languages not only to communicate with representatives of other cultures but also to improve professional skills since modern society requires specialists to solve global issues ( Berger, 2021 ). Teaching a foreign language has long gone beyond the boundaries of classrooms. The very term “distance learning of foreign languages” includes an entire educational paradigm related to the socio-cognitive, pragmatic, and ethical aspects of the foreign-speaking world.

Both foreign language learners and teachers in the process of communication face not only issues related to ethnicity and dilemmas associated with historically, socially, and culturally different psychology and worldviews. It includes ways of rationalizing perception, knowledge structures, attitudes, and the choice of expressing these feelings and beliefs. For both students and teachers, language learning and cognition are inseparable from the emotional component, which regulates adaptation to changes caused by external and internal educational events. Considering these issues within the framework of the psycholinguistic discipline, several studies ( Ko and Rossen, 2017 ; Marlina, 2018 ; Liu et al., 2021 ; McCallum, 2022 ) propose a set of interrelated methods and actions, including (1) systematic approach to developing the competencies of a foreign language learner and teacher; (2) introduction of a psycholinguistic approach to the study/teaching of a foreign language [ELL/ELT – English Language Learning and English Language Teaching], which highlights the student, their personality; (3) support of language training programs for graduates and postgraduates with ethnolinguistic components of intercultural learning; (4) development of compatible formats of teacher and student research activities and mechanisms for the use of these products ( Marlina, 2018 ). This collective monograph examines the tasks related to implementing these actions, with recommendations leading to a methodological basis for developing a linguistic personality in ELT. The proposed methodologies appeared by virtue of a series of studies by scholars ( Kholod, 2018 ; Marlina, 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ) in the field of linguistic categorization of emotions, language acquisition, and bilingual identity, as well as the basics of culture research in language education.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on education. Almost overnight, it stopped teaching in most educational institutions and gradually affected all levels of education. The situation was unprecedented. Educational institutions had to switch to a new form of education rapidly. The pandemic has affected both the means and the forms, methods, and teaching approaches, including the competency paradigm in teaching a foreign language ( Wang and Zou, 2021 ; Samorodova et al., 2022 ). The tasks of the pedagogical community are to create conditions for building up the information technology base of educational institutions, developing, and implementing adapted teaching methods based on the potential of information technologies. For example, Russia is implementing the National Project “Education,” which plans to “…create by 2024 a new and secure digital educational environment in all educational institutions at every level, which will ensure high quality and accessibility of education of all types and levels” ( Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation, 2022 ). The Modern Digital Educational Environment (MDEE) was created as part of the project, uniting more than 100 Russian universities and 70 different educational platforms. Currently, MDEE offers 1,560 courses on various subjects where students can improve their knowledge, skills, and abilities in their major ( Akubekova and Kulyeva, 2021 ).

The transformation of foreign language teaching methods based on a competency-based approach within the framework of online distance learning has affected all interested parties, for example, teachers, students, and educational institutions. Therefore, the research on these relationships is scientifically significant.

The research aim is to analyze the existing and most frequently used methods and competency-based approaches to teaching a foreign language remotely (online).

The following tasks have been actualized to achieve the aim:

1. Classifying the methods of teaching a foreign language based on the competency approach;

2. Identifying the most effective methods according to teachers and students.

Combining creativity and new technologies in teaching and learning a foreign language achieves these tasks. The basis for the current research is the scientific work of specialists from different countries ( Alipichev and Takanova, 2020 ; Baker, 2020 ; Almehlafi, 2021 ; Wang and Zou, 2021 ). It covers the issues of teaching foreign languages and the results of a survey of teachers and students of bachelor’s and master’s degrees ( Bailey et al., 2021 ; Zubr and Sokolova, 2021 ). The analytical methods of this work include the study and analysis of the work of some Eurasian scientists and teachers ( Marlina, 2018 ; Ogbonna et al., 2019 ; Hovhannisyan, 2022 ; McCallum, 2022 ). This choice is justified by methodological limitations, namely the use of relevant literature over the past 5 years in the field of effective methods of teaching a foreign language to university students in the framework of online distance learning, mainly in Europe and Asia. All literature is freely available (Springer Nature Switzerland AG.) and allows determining the development trends of foreign language online education today. Besides, we used the method of interviewing teachers and students in the form of an anonymous questionnaire.

The methodological basis includes methods of analyzing the practical experience of teaching foreign languages based on the competency approach, synthesis of national and international teaching experience, comparison of national models of the language environment, and generalization of sociological data in the distance segment.

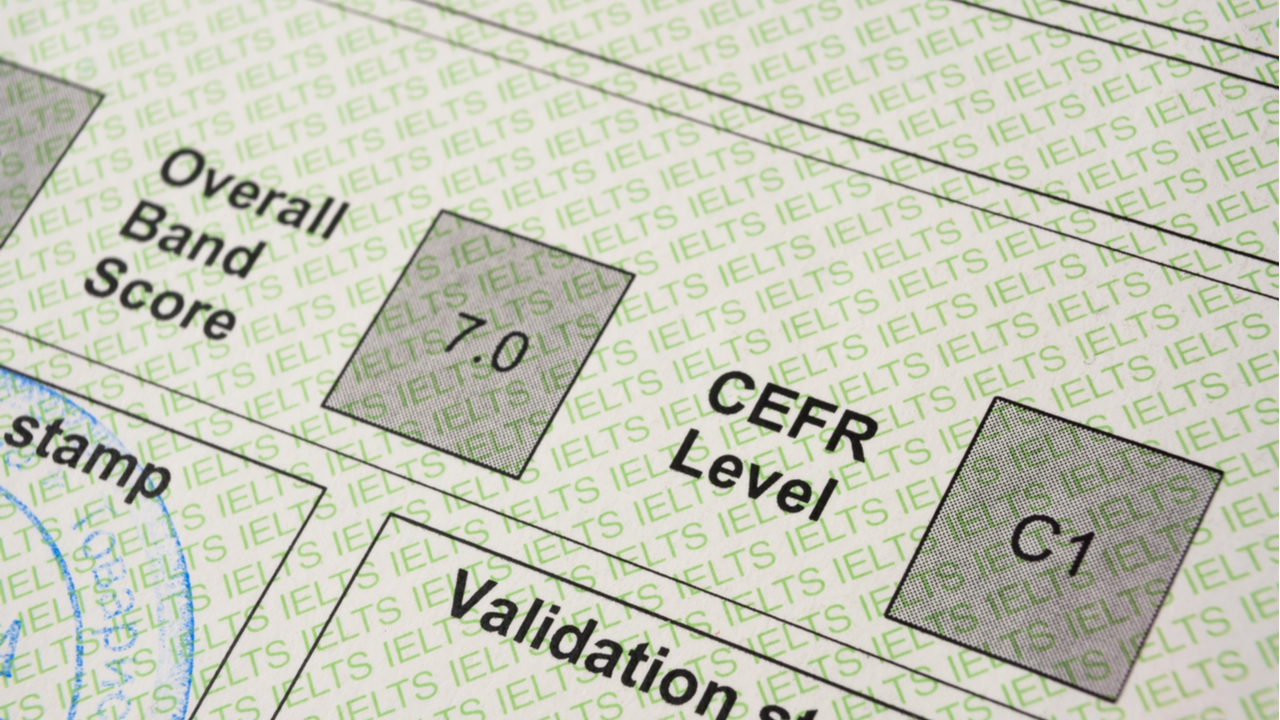

2. Assessing the effectiveness of distance learning in foreign languages

When describing methods and approaches to learning foreign languages directly, it is crucial and relevant to evaluate the effectiveness of online learning. Active academic mobility in Eurasia is also supported by a great variety of English-language programs at all three stages of the Bologna process. According to the Masterportal.com portal, there are over 20,000 bachelor’s programs in English, 22,000 master’s programs, 2,500 Ph.D. programs, and about 5,000 online degree programs in Europe ( Balan, 2022 ). From 2014 to 2021, the number of English-taught bachelor’s programs increased by 2.47 times. Simultaneously, English-language programs are equally available at state universities on a paid and budgetary basis. For international students from outside the EU jurisdiction, free English-language programs are available in Germany and Norway; in France, Austria, and Belgium, programs are available at a low cost of 200 to 3,000 euros per year ( Balan, 2022 ). To study in English-language programs, students must submit diplomas of international exams confirming the level of English proficiency (PTE Academic, IELTS Academic, TOEFL iBT) ( Balan, 2022 ). The largest share of English-language programs is among educational programs in Switzerland (80%), the Netherlands (60%), Denmark (56%), Finland (55%), and Sweden (50%).

The future of education is defined in the Open University (OU) innovative pedagogy report 2022 ( Hulme, 2022 ). The goal of the research by Zubr and Sokolova (2021) is to present the survey questionnaire results, which focus on the experience of distance learning students. The questionnaire contains feedback from students regarding the distance learning form (distance mode) they have encountered. The study was conducted at the Faculty of Informatics and Management [FIM] at the University of Hradec Králové (Czech Republic). The interviewed students studied during the 2020/2021 academic year using distance learning. A total of 122 students took part in the study. The results show that FIM often uses online tools such as Microsoft Teams and BlackBoard. Students pointed out that the BlackBoard Learning Management System [LMS] is the most useful tool. In general, respondents are equally satisfied with distance learning and face-to-face training. The researchers emphasize that it is impossible to determine whether students prefer distance learning or full-time education ( Zubr and Sokolova, 2021 ). The survey “Digital Learning at the Bashkir State University” (Bashkir State University) among 204 s-year bachelor students at the beginning of the 2021/2022 academic year revealed that 84% of students prefer distance learning in a foreign language. In total, 95% of students always attend online classes and video conferences. The majority (80%) increased their level of motivation for distance learning ( Akubekova and Kulyeva, 2021 ). We agree that it is difficult to say unequivocally that distance learning is 100% a priority. Our teaching experience shows that blended learning is the most effective method. The most interesting digital methods of learning foreign languages will be considered further.

3. Methods of formation of multi-literacy

An interesting technique is the formation of multi-literacy. Multimodal writing positively impacts students’ written competency, ability to cooperate, and motivation to learn. The study by Zhang et al. (2021) , based on the theory of multi-literacy and the use of technology, is aimed at studying the influence of multimodal writing on vocabulary acquisition by EFL students (English as a foreign language). Seventy students were recruited, including 35 in the experimental group (EG) and 35 in the control group (CG). The selection criteria were teaching multimodal writing and EFL students mastering the English vocabulary in tweet-based writing in the official WeChat account. The experimental group mastered the multimodality technique, and the control group mastered the traditional technique. After a 7-week experiment for EG, positive improvements were noted in the acquisition of vocabulary, especially in the use of the dictionary. There were no significant differences when comparing traditional writing and multimodal writing. Questionnaires and interviews about the perception and attitude of students toward writing tweets on the official account were conducted among 35 students in EG. Most students considered multimodal writing a pleasant and effective way to improve vocabulary acquisition ( Zhang et al., 2021 ). The methodology of multi-literacy and teaching Russian to Greek-speaking students has also been tested in European countries. As practice shows, the most preferable is the division of students into microgroups (3–4 students). According to the gender composition of microgroups, it is recommended to adhere to the proportions of 50:50 and 60:40 ( Kholod, 2016 ).

From 2016 until today, the dilemmas method has been applied during online foreign language classes in groups of pedagogical and historical faculties of Yaroslavl State Pedagogical University named after K. D. Ushinsky (Yaroslavl, Russia). On average, the method is used several times per semester. The parameters adopted for evaluating heuristic (sounding) speech in foreign practice were used during the control: accuracy, fluency (freedom), interaction with the communicant, pronunciation, variety, and goal achievement. Compared with the control groups, where the method was not applied, the students of the considered groups showed an increase in fluency by 30%, a variety of language structures and an improvement in pronunciation – by 16%, accuracy – by 20%, and communication with a partner and achievement of a goal – by 25% ( Kholod, 2018 ). At the Sibay Institute (branch) of Bashkir State University (Sibay, Russia), Bashkir State University (Ufa, Russia), and Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation (Moscow, Russia), the distance learning system is organized in the Moodle educational platform, which allows work effectively in tandem for both teachers and students. The system is accessible; it is designed for different levels of learners. Marinina emphasizes, “Providing access to the platform and its content from any remote point of the country and the world is another of its absolute advantages compared to traditional teaching methods” ( Marinina and Kruchinkina, 2020 ). The teaching staff develops their own electronic courses with theoretical and practical material on multi-literacy and tests based on the approved DWP (disciplines work programs). The Sibay Institute (branch) of Bashkir State University, Bashkir State University, and Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation offer a large set of interactive elements for the formation of foreign language multi-literacy: forums, glossaries, chats, blogs, video conferences.

4. Methods of learning English using artificial intelligence methods

Methods based on artificial intelligence are of undoubted interest for teachers of higher educational institutions. In the studies of Liu et al. (2021) , an application for studying the concept of a foreign language is proposed, combining the study of the concept of English and artificial intelligence technologies, such as automatic generation of options and speech recognition analysis. The app is based on a WeChat mini program aimed at helping and conducting English language learning by providing various exercises such as multiple-choice and phonetic questions. To generate incorrect variants of multiple-choice questions, scientists utilize new words from WordNet. It is a large English lexical database in which word combinations are detected using statistical processing of natural language and neural network models, such as Continuous bag of words [CBOW] in Word2vec or BERT [Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers]. The user’s voice input is built into the speech interaction for recognition and analysis. Based on the framework, scholars expect that this application will be combined with other artificial intelligence [AI] technologies to analyze user performance and adjust the subsequent curriculum accordingly ( Liu et al., 2021 ).

The study by Ogbonna et al. (2019) provides an example of the use of synchronous computer-mediated communication [SCMC] in English lessons at Wuhan University (China) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The goal is to identify the advantages and disadvantages of using applications with synchronous technologies in online English courses. The data set consists of ethnographic observations and in-depth interviews with the teacher and students. Thematic analysis shows that the advantages of SCMC include the availability of extensive learning resources, the availability of instant information exchange, and a relatively calm learning environment. The two main drawbacks are that face-to-face communication generally leads to the teacher showing “one person,” and the limited screen size reduces eye contact between the teacher and the students. The research ( Ogbonna et al., 2019 ) shows that SCMC can be used during and after a pandemic to stimulate student discussion and cooperation.

5. Methodology of formation of communicative foreign language digital competency

Both voice and video blogs are widely used in various fields. Their use in learning English as a foreign language [EFL], mainly at universities, aims at improving the listening and speaking skills of students ( Ogbonna et al., 2019 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ). Few studies have examined how involving EFL students in creating video blogs can help improve their conversational speech ( Liu et al., 2021 ; McCallum, 2022 ). Therefore, the publication of Wang and Zou (2021) is a study of the impact of the creation of voice and video blogs on the spoken language of EFL students and their perception of digital multimodal composition based on video blogs [DMC]. Sixty-seven high school students from Guangdong Province, China, participated in the 10-week study. The data included their preliminary and post-test performance evaluations, two videos, a questionnaire, and a semi-structured interview. The research results displayed a positive effect of DMC on conversational speech based on video blogs. The students showed better fluency from the first to the second video blogs. Additionally, EFL students leading video blogs surpassed their colleagues in accuracy but lost in fluency, in which they demonstrated some significant changes ( Wang and Zou, 2021 ). The Russian experience of testing the methodology for the formation of communicative foreign language digital competency is focused on the use of YouTube video hosting in teaching a foreign language.

Portal features included in classroom and extracurricular activities can enhance learning quality ( Ezhova and Pats, 2020 ). By producing, sharing, and commenting on educational videos, YouTube promotes student engagement in a creative and collaborative learning environment. The advantages of the portal in teaching a foreign language are the following. A wide range of video materials – from video lessons created specifically to use in teaching a foreign language to vlogs edited by bloggers, which can also be included in the educational process – make it possible to work with authentic texts, listen to the speech of native speakers, and enter into dialogues with them. The visibility of information makes it possible to increase the efficiency of the learning process. While watching, it is possible to pay attention to articulatory features, facial expressions, and pantomime ( Borshcheva and Kuzmina, 2021 ). Teachers of Bashkir State University, Bashkir State University, and Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation during the survey indicated that it is also important that the student receives information about the appearance of the communication participants and the environment in which events take place. Videos can become a means of providing background information, an idea of the life, traditions, and reality of the countries of the studied language; these contribute to the implementation of such an important requirement of the communicative methodology of language cognition as immersion in a foreign language reality and its comprehension.

6. Conclusion

Among the wide variety of methods, competency-based approaches related to information and communication technologies [ICT] are utilized most often. We also suggest that when language teachers conduct courses using SCMC tools or platforms, students should be given wide opportunities to express their opinions. Additionally, most teachers recognize creating instructional videos as the most effective for forming students’ creative abilities. According to students, this type of activity also has the greatest learning effect and stimulates creativity, making the learning process more interesting and effective.

The consideration of several relevant competency-based approaches is the practical significance of reviewing effective methods of teaching a foreign language to university students in the framework of distance online learning based on national and international experience.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Akubekova, D. G., and Kulyeva, A. A. (2021). Digitalization of academic forms of teaching English. Kazan Pedagogical J. 6, 113–119. doi: 10.51379/KPJ.2021.150.6.016

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alipichev, A., and Takanova, O. (2020). Independent research activity of MSc and PhD students: case-study of the development of academic skills FFL classes. XLinguae 13, 237–252. doi: 10.18355/XL.2020.13.01.18

Almehlafi, S. S. (2021). Online study of English language courses using blackboard at Saudi universities in the era of COVID-19: perception and use. PSU Res. Rev. 5, 16–32. doi: 10.1108/PRR-08-2020-0026

Bailey, D., Almusharraf, N., and Hatcher, R. (2021). Finding satisfaction: intrinsic motivation for synchronous and asynchronous communication in the online language learning context. Educ. Inform. Technol. 26, 2563–2583. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10369-z

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baker, W. (2020). “English as a lingua franca and transcultural communication: rethinking competencies and pedagogy for ELT” in Ontologies of the English language: conceptualizing language for learning, teaching and evaluation . eds. C. Hall and R. Wicaksono (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 253–272.

Google Scholar

Balan, R. S. (2022). Best English-Taught Universities in Europe in 2022. Available at: https://www.mastersportal.com/articles/2979/best-english-taught-universities-in-europe-in-2022.html

Berger, A. (2021). “Advanced English language competency at the intersection of programme design, pedagogical practice, and teacher research: an introduction. Developing advanced English language competency,” in Developing Advanced English Language Competence . Vol 22. eds. A. Berger, H. Heaney, P. Resnik, A. Rieder-Bünemann and G. Savukova (English Language Education, Springer, Cham).

Borshcheva, O. V., and Kuzmina, G. Y. (2021). YouTube in teaching foreign languages at university. Available at: https://scipress.ru/pedagogy/articles/videokhosting-youtube-v-obuchenii-inostrannomu-yazyku-v-vuze.html

Ezhova, Y. V., and Pats, M. V. (2020). YouTube as a training resource (foreign language, non-language university). Int. J. Human. Nat. Sci. 7-2, 36–39. doi: 10.24411/2500-1000-2020-10880

Hovhannisyan, G. R. (2022). Psycholinguistic competencies and interculturality in ELT. Eng. Lang. Educ. 24, 15–33.

Hulme, A. K. (2022). Future of education is identified in the OU’s innovating pedagogy report 2022. Available at: https://ou-iet.cdn.prismic.io/ou-iet/5c334004-5f87-41f9-8570-e5db7be8b9dc_innovating-pedagogy-2022.pdf

Kholod, N. I. (2016). Application of the dilemmas method in teaching a foreign language at higher education institution. Language Culture. Available at: https://vestnik.tspu.edu.ru/files/vestnik/PDF/articles/kholod_n._i._92_95_7_196_2018.pdf

Kholod, N. I. (2018). Application of moral dilemmas method for students’ communicative competency development in classes of foreign language at higher education institution. Bull. Tomsk State Pedagogical Univ. 7, 92–95. doi: 10.23951/1609-624X-2018-7-92-95

Ko, S., and Rossen, S. (2017). Online learning: A practical guide , 4th. London: Rutledge.

Liu, R., Shu, H., Li, P., Xu, Y., Yong, P., and Li, R. (2021). AI-based language chatbot 2.0 – the design and implementation of English language concept learning agent app. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 13089, 25–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-92836-0_3

Marinina, Y. A., and Kruchinkina, G. A. (2020). Digital humanities: the possibility of using intelligent learning systems. Lecture Notes Netw. Syst. 129, 395–402.

Marlina, R. (2018). “Teaching language skills” in The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching . ed. J. Liontas (New York: Wiley), 1–15.

McCallum, L. (2022). “English language teaching in the EU: an introduction” in English language teaching. English language teaching: theory, research and pedagogy . ed. L. McCallum (Singapore: Springer), 3–10.

Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation (2022). National project “Education.” Available at: https://edu.gov.ru/national-project

Ogbonna, K. G., Ibezim, N. E., and Obi, K. A. (2019). Synchronous and asynchronous e-learning in text processing training: an experimental approach. S. Afr. J. 39, 1–15. doi: 10.15700/saje.v39n2a1383

Samorodova, E. A., Belyaeva, I. G., Birova, J., and Kobylarek, A. (2022). Technology-based methods for creative teaching and learning of foreign languages. Lecture Notes Netw. Syst. 345, 797–810. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-89708-6_65

Wang, Z., and Zou, D. (2021). Synchronous computer mediated communication in English language classes during the pandemic: a case study of Wuhan. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci 13089, 325–333. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-92836-0_28

Zhang, N., Liu, H., and Liu, K. (2021). Enhancing EFL learners’ English vocabulary acquisition in WeChat official account tweet-based writing. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 13089, 71–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-92836-0_7

Zubr, V., and Sokolova, M. (2021). Evaluation of distance learning from the perspective of university students – a case study. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci 13089, 61–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-92836-0_6

Keywords: ELL competencies, education, ELT competencies, online learning, students, video blog, synchronous communication

Citation: Akhmetzadina ZR, Mukhtarullina AR, Starodubtseva EA, Kozlova MN and Pluzhnikova YA (2023) Review of effective methods of teaching a foreign language to university students in the framework of online distance learning: international experience. Front. Educ . 8:1125458. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1125458

Received: 16 December 2022; Accepted: 02 May 2023; Published: 30 May 2023.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2023 Akhmetzadina, Mukhtarullina, Starodubtseva, Kozlova and Pluzhnikova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zulfiya R. Akhmetzadina, [email protected] ; [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 30 June 2020

Effects of using inquiry-based learning on EFL students’ critical thinking skills

- Bantalem Derseh Wale 1 &

- Kassie Shifere Bishaw 2

Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education volume 5 , Article number: 9 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

34 Citations

Metrics details

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of using inquiry-based learning on students’ critical thinking skills. A quasi-experimental design which employed time series design with single group participants was used. A total of 20 EFL undergraduate students who took advanced writing skills course were selected using comprehensive sampling method. Tests, focus group discussion, and student-reflective journal were used to gather data on the students’ critical thinking skills. The participants were given a series of three argumentative essay writing pretests both before and after the intervention, inquiry-based argumentative essay writing instruction. While the quantitative data were analyzed using One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA, the qualitative data were analyzed through narration. The findings of the study revealed that using inquiry-based argumentative writing instruction enhances students’ critical thinking skills. Therefore, inquiry-based instruction is suggested as a means to improve students’ critical thinking skills because the method enhances students' interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation skills which are the core critical thinking skills.

Introduction

Critical thinking is the ability to ask and/or answer insightful questions in a most productive way in order to reach on a comprehensive understanding (Hilsdon, 2010 ). It consists interpretation, analysis, evaluation, synthesize explanation, inference, and self-regulation. Empowering critical thinking skills among students in higher education especially in academic writing through the integration of critical thinking into the teaching learning process is essential in order to develop students’ problem solving, decision making and communication skills (Abdullah, 2014 ; Adege, 2016 ; McLean, 2005 ). Inquiry-based learning develops students’ critical thinking skills because it helps students to develop interpreting, analyzing, evaluating, inferring, explaining, and self-regulation skills which are the core critical thinking skills (Facione, 2011 ; Facione & Facione, 1994 ; Hilsdon, 2010 ).

The level of thinking depends on the level of questioning as long as the questioning leads to new perspectives (Buranapatana, 2006 ). When students learn to ask their own thought-provoking questions in and outside the classroom, and provide explanatory answers, they are well on the way to self-regulation of their learning. In inquiry-based writing instruction, students engaged in writing lessons and tasks that enhance their ability to apply these critical thinking skills because the method emphasize to produce texts through inquisition and investigation. In writing, when students’ written papers realize these skills, the students considered that their critical thinking skills are developed.

Inquiry-based learning is the act of gaining knowledge and skills through asking for information (Lee, 2014 ). It is a discovery method of learning that involves students in making observations; posing questions; examining sources; gathering, analyzing, interpreting, and synthesizing data; proposing answers, explanations and predictions; communicating findings through discussion and reflection; applying findings to the real situation, and following up new questions that may arise in the process. Inquiry-based learning emphasizes students’ abilities to critically view, question, and explore various perspectives and concepts of the real world. It takes place when the teacher facilitates and scaffolds learning than gives facts and knowledge so that students engage in investigating, questioning, and explaining their world in a student-centered learning environment.

Although inquiry-based learning is intended for science as it is classified as scientific approach, it can be implemented in language field. Rejeki ( 2017 ) mentioned that inquiry-based language learning is useful in promoting lifelong education that enables EFL learners to continue the quest for knowledge throughout life. Similarly, Lee ( 2014 ) stated that inquiry-based learning is an analogy for communicative approach. The principles of inquiry-based learning are compatible with Communicative Language Teaching because communicative approach focuses on communicative proficiency rather than mere mastery of structure to develop learners’ communicative competence as to inquiry-based learning. Inquiry-based learning is, therefore, a form of Communicative Language Teaching which serves to bring down the general principles of communicative approach, and implement in language classrooms in an inquisitive and discovery manner (Lee, 2014 ; Qing & Jin, 2007 ; Richards & Rodgers, 2001 ). While communicative approach is an umbrella of various active language learning methods, inquiry-based learning is one of the active learning methods that drive learning through inquisition and investigation. It mainly focuses on discovery and learner cognitive development to be achieved using thoughtful questions.

In inquiry-based writing instruction, students engaged in pre-writing tasks through generating ideas, narrowing and clarifying topics; exploring information on their writing topics from various sources; explaining their discoveries gained from the exploration, and elaborating their thinking through transforming their understanding into the real world situation. When students come up through this distinct process in manipulating such tasks, their critical thinking skills can be enhanced because this process develops students’ ability to analyze, synthesis, and evaluate concepts.

This study also revealed that students’ critical thinking skills has been enhanced through inquiry-based writing instruction because the method focuses on the process of knowledge discovery that involves students in seeking, collecting, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information; creating ideas, and solving problems through communication, collaboration, deep thinking, and learner autonomy. The study can contribute to the field of foreign language learning by possibly leading English language teachers and learners into a more effective language learning method. The study has applicable significances to EFL teachers to understand the nature and application of inquiry-based learning.

Literature review