Essays About Moving to a New Place: Top 5 Examples and 5 Writing Prompts

Moving homes may seem daunting, no matter where you go. If you are writing essays about moving to a new place, you can use our guide to inspire you.

Almost all of us have experienced moving to a new place at least once. As hard as it is for some, it is simply a part of life. Frequently-given reasons for moving include financial difficulty or success, family issues, career opportunities, or just a change of scenery.

Whether you are moving to a new house, village, city, or even country, it can seem scary at first. However, embracing a more positive outlook is crucial so as not to get burnt out. We should think about moving and all changes in our life as encouraging us to learn more and become better people.

5 Essay Examples To Inspire Your Writing

1. finding a new house by ekrmaul haque, 2. first impressions by isabel hui, 3. reflections on moving by colleen quinn, 4. downsizing and moving to the countryside two years on. what it’s really like and some tips if you’re thinking of upping sticks too by jessica rose williams.

- 5. The Dos and Don’ts of Moving to a New City by Aoife Smith

1. How to Cope with Moving Homes

2. would you choose to move to a new place, 3. a dream location, 4. my experience moving to a new place, 5. moving homes alone vs. with your family.

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

“Sometimes it’s really hard to find a place that I like to live and a house that is suitable for me. This time I learn so many things that I can found a new house quickly. While finding a new house I was bit frustrated, however gaining new experience and working with new people was always fun for me. Finally I am happy, and I have started living peacefully in my new place.”

Haque writes about concerns he and many others have when looking for a new house to move into, including safety, cost, and accessibility. These concerns made it quite difficult for him to find a new place to move into; however, he was able to find a nice neighborhood with a place he could move into, one near school and work. You might also be interested in these articles about immigration .

“I didn’t want to come off as a try-hard, but I also didn’t want to be seen as a slob. Not only was it my first day of high school, but it was my first day of school in a new state; first impressions are everything, and it was imperative for me to impress the people who I would spend the next four years with. For the first time in my life, I thought about how convenient it would be to wear the horrendous matching plaid skirts that private schools enforce.”

Hui, whose essay was featured in the New York Times, writes about her anxiety on her first day of school after having moved to a new place. She wanted to make an excellent first impression with what she would wear; Hui coincidentally wore the same outfit as her teacher and could connect with her and share her anxiety and concern. She also gave a speech to the class introducing herself. This, Hui says, was an unforgettable experience that she would treasure. Check out these essays about home .

“In the end, I confess that I am a creature of habit and so moving is always a traumatic experience for me. I always wait until the last minute to start organizing, I always have stuff left over that I’m frantically dealing with on the last day, and I’m always much sadder about leaving than I am excited about my new adventure.”

In her essay, Quinn discusses her feelings when she moves houses: she is excited for the future yet mournful for what once was and all the memories associated with the old house. She takes pictures of her houses to remind her of her life there. She also grows so attached that she holds off on packing up until the last minute. However, she acknowledges that life goes on and is still excited for what comes next.

“Two years later and I’m sat writing this outside said cottage. The sun is filtering through the two giant trees that shade our house and the birds are singing as if they’re in a choir. I can confirm I’m happy and with hindsight I had nothing to worry about, though I do think my concerns were valid. So many of us dream of a different kind of life – a quieter, slower paced life surrounded by nature, yet one that still allows us to enjoy 21st century pleasures.

Williams reminisces about her anxiety when moving into a country cottage, a drastic change from her previous home. However, she has learned to love country living, and moving to a new place has made her happier. She discusses the joys of her new life, such as gardening, the scenic countryside, and peace and quiet. She enjoys her current house more than city living.

5. The Dos and Don’ts of Moving to a New City by Aoife Smith

“But the primary element this ample free time has offered me is time to think about what truly makes an ideal, comfortable life, and what’s necessary for a positive living environment. Of course, the grass is always greener, but perhaps, this awakening has offered me an insight into what the grass needs to grow. It’s tough to hear, but all your bad habits will translate to your new culture so don’t expect to go ‘Eat, Pray, Love’ overnight.”

Smith gives tips on how to adjust to city life well. For example, he tells readers to stay in contact with friends and get out of their comfort zone while also saying not to buy a “too-small” apartment and get a remote job without face-to-face interaction. His tips, having come from someone who has experienced this personally, are perfect for those looking to move to a big city.

5 Prompts for Essays About Moving to a New Place

Moving is challenging at first, but overcoming your fear and anxiety is essential. Based on research, personal experience, or both, come up with some tips on how to cope with moving to a new place; elaborate on these in your essay. Explain your tips adequately, and perhaps include some words of reassurance for readers that moving is a good thing.

For a strong argumentative essay, write about whether you would prefer to stay in the home you live in now or to move somewhere else. Then, support your argument, including a discussion and rebuttal of the opposing viewpoint, and explain the benefits of your choice.

Everyone has their own “dream house” of some sort. If you could, where would you move to, and why? It could be a real place or something based on a real place; describe it and explain what makes it so appealing to you.

Almost all of us have experienced moving. In your essay, reflect on when you moved to a new place. How did you adjust? Do you miss your old house? Explain how this moving experience helped form you and be descriptive in your narration.

Most people can attest that moving as a child or with one’s family is a much different experience from moving alone. Based on others; testimonials and anecdotes, compare and contrast these two experiences. To add an interesting perspective, you can also include which of the two you prefer.

For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .If you still need help, our guide to grammar and punctuation explains more.

Essay on Moving To A New House

Students are often asked to write an essay on Moving To A New House in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Moving To A New House

Moving: an overview.

Moving to a new house is a big change. It can be exciting, but also a bit scary. It means leaving a familiar place and starting fresh in a new one. We have to pack up all our things, say goodbye to our old home, and get ready for a new adventure.

The Packing Process

Packing is a big part of moving. We need to put all our things in boxes. We might find old toys or books we forgot about. It’s a good time to sort through our stuff and decide what to keep and what to give away.

The New House

The new house might feel strange at first. It takes time to get used to a new place. We need to find where everything goes and make it feel like home. This can be fun, like a big puzzle to solve.

Meeting New Friends

Moving also means meeting new people. We might make new friends in our new neighborhood or at our new school. It’s a chance to learn about different people and places.

250 Words Essay on Moving To A New House

Introduction.

Moving to a new house is a big event for everyone. It can be exciting and scary at the same time. You get to live in a new place, make new friends, and start a new life. But also, you have to leave behind your old house, old friends, and familiar things.

Feelings About Moving

Some people feel happy about moving because they look forward to new experiences. They want to see new places and meet new people. Others feel sad because they will miss their old house and friends. They are also scared because they don’t know what the new place will be like.

Preparing for the Move

Moving to a new house needs a lot of work. You have to pack all your things in boxes. You have to sort out what to keep and what to throw away. You also have to clean the old house and the new house. It can be tiring but it can also be fun. You can find old things that you forgot about and remember good times.

Settling in the New House

Once you move, you have to unpack and arrange your things in the new house. It takes time to get used to the new place. You have to learn where things are, like the shops and the school. You also have to make new friends. It can be hard at first, but after some time, it can feel like home.

Moving to a new house is a big change. It can be hard and it can be fun. It is a chance to start a new life and make new memories. So, even if it is scary, it can also be a good thing.

500 Words Essay on Moving To A New House

The feeling of moving.

When you first find out you’re moving, you might feel a lot of different emotions. You might feel happy about the chance to start fresh in a new place. You might also feel sad about leaving your old house, your friends, and everything that’s familiar to you. It’s normal to feel all these things. It’s part of the process of moving and starting a new chapter in your life.

Getting ready to move to a new house involves a lot of work. First, you have to pack up all your things. This can be a good chance to get rid of stuff you don’t need anymore. You can donate it, sell it, or just throw it away. Then, you have to make sure everything is clean and ready for the people who will live in your old house after you.

The Day of the Move

Settling into the new house.

Once you’ve moved all your things into your new house, it’s time to start making it feel like home. You can arrange your furniture, hang up pictures, and start getting to know your new neighborhood. It might take a little while to get used to your new house and feel comfortable there. But with time, it will start to feel like home.

Moving to a new house is a big change. It can be hard to leave your old house and everything that’s familiar to you. But it can also be an exciting adventure. You get to start fresh in a new place, meet new people, and make new memories. So even though it can be scary, it’s also something to look forward to. And remember, home is not just a place, it’s a feeling. So no matter where you move, you can always make your new house feel like home.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Human Migration — Embracing Change: A Narrative of Moving to a New Place

Embracing Change: a Narrative of Moving to a New Place

- Categories: Human Migration

About this sample

Words: 644 |

Published: Sep 5, 2023

Words: 644 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The decision and anticipation, navigating the transition, embracing the unfamiliar, conclusion: a continuum of change and discovery.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 719 words

2 pages / 991 words

1 pages / 558 words

1 pages / 648 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Human Migration

Immigration has been a driving force in the development and progress of nations throughout history. The contributions of immigrants have left indelible marks on the cultural, economic, and social fabric of their adopted [...]

Assault On Paradise by Tatiana Lobo is a compelling novel that sheds light on the harsh realities of colonialism and its impact on indigenous communities in Costa Rica. The book follows the story of Altagracia, a young [...]

Immigration is a complex and divisive issue that has been at the forefront of political debates in many countries. The question of whether immigration laws should be reformed is one that requires careful consideration and [...]

Mohsin Hamid's novel Exit West is a powerful and thought-provoking exploration of the refugee experience and the human desire for freedom and belonging. The novel follows the journey of Nadia and Saeed, two young lovers who [...]

The American Dream a phrase that was once the foundation of many immigrants’ hopes for a new life now feels fanciful and almost cruel. Not only do immigrants face economic difficulties upon arrival to the U.S., but they also [...]

Humans have been migrating from a very early age when civilized life started evolving around the world. The first ever-human migration started 60,000 years before from Africa (Maps of Human Migration, n.d, para.Since then, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Stanley tumblers, Tiny Tags and more new Target arrivals we’re eyeing for fall

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

- TODAY Plaza

My childhood home became my world during the pandemic. Then, we moved

When I first moved away from home and into my college dorm, my family bought a new couch.

They replaced our brown, well-worn leather sofa with a tan sectional, featuring cupholders and a reclining option for every family member — even a corner for the dog. Then, they fostered a puppy. He was young and hyperactive and antagonized our dog by jumping on his back and stealing his bed.

I thought our house — a place I had called home my entire life — couldn’t have changed any more than that. But in March 2020, I moved back home because of the coronavirus pandemic .

And then, in what had already become an upside-down world, we moved out of my childhood home altogether.

A house full of memories

My parents moved into our white house with hunter green doors and matching shutters right after it was built in 1999. It was a new neighborhood in Charlotte, North Carolina, with one main street lined with tract houses, each with a square plot of land out front marked with a tree. As I grew up, so did the neighborhood, expanding into the community that it is today.

That house was where I first met my two younger brothers after they were taken home from the hospital. It’s where we all learned to walk, watched “The Wiggles” for hours on end and memorized multiplication tables. At that kitchen table, I was told about my mom’s pregnancy, the marriage of my aunt and the death of grandparents. Every monumental event in my life was rooted to that house.

My move back home mid-sophomore year became yet another defining experience tied to that physical space.

The pandemic transformed my house into my entire world. With local stay-at-home orders, there was nowhere else to go. My desk became my classroom, and, later that summer, it served as my newsroom during my first journalism internship. Our kitchen table became part office, part co-working space. The playroom turned into a dorm lounge, where I would talk with my brothers and sometimes join them for a video game when the boredom really sunk in.

And my favorite place of all, our living room, turned into our movie theater as we watched a full lineup of shows and movies each night, starting with “Jeopardy!” and usually ending with a rerun of “The Office.”

Nostalgia was a comforting emotion to surround myself with. The past was fixed. And the future had never been more uncertain.

Our house was well lived in. Closets overflowed, our attic was full, and in every drawer, you could find old crayons, a lost pair of scissors and a drawing from someone’s elementary school art class. I didn’t like to throw things away. What if I needed it one day? Every nook and cranny was occupied by something, and even if it seemed like we didn’t have enough room, we’d make some.

My parents had always said we would move one day. But it was always one of those far-off notions — something that may happen someday but not anytime soon.

But when our house became our whole world and our weekends were limited to entertainment inside, my parents started taking on home improvement projects. We repainted my room from neon turquoise to a neutral beige. We fixed the doorknob-shaped hole in our playroom wall and painted over the crayon drawings hidden in our old playroom. I remember having a passing thought that maybe it was all done just so we could live more comfortably here.

But I soon found out the reality: We were getting it ready to sell it.

Uprooting — fueled in large part by remote work — has become a part of the pandemic narrative. Data from the United States Postal Service shows that in 2020, more than 7 million households moved to a different county as many people moved from big cities to the suburbs, an increase of half a million compared to 2019. But the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University found that these upticks in early and late 2020 did not represent "a significant change from prior years in the total number of moves."

Whatever trend the data ultimately end up validating, my family's move was just one of many during remarkably unsettling times.

Growing up, I liked the idea of moving. It always sounded exciting. Anytime a new student joined my class, I would pepper them with questions: How did you pack everything? How could you carry it? How did your furniture fit through doors?

But in June 2020, my parents told us over dinner that we were officially selling the house. It was finally my turn to go through the excitement of a big move, but I felt more like a child forced to part with her security blanket.

During the early days of the pandemic, my friends and I joked that we had regressed. I started re-watching my favorite show from high school, “The Vampire Diaries,” and reread every single “Percy Jackson” book, including the spinoff series. I forced my brothers to play old board games like the Game of Life, Trouble and Sorry with me. Nostalgia was a comforting emotion to surround myself with. The past was fixed. And the future had never been more uncertain.

So the idea of packing everything up and moving into a new space gave me a feeling of grief for the 20 years I had spent there. I’d never again look out my window and see the view of our empty backyard, which had been occupied by a play set and then a trampoline at various times in my life. I’d miss running in our neighborhood’s perfect loop or walking my dog on his favorite route. And I’d miss being able to lean over the railing of the second story to have a conversation with my family downstairs.

For (my brothers), the new house looked like a brand new playground. To me, I felt like I was finally leaving one.

My family moved just as Charlotte was entering a hot seller's market, mirroring a real estate trend seen across the country. By the end of 2020, inventory in the city shrank 28.4% and sales increased by 8.5%, leading to a 32% decrease in the supply of homes, according to the Charlotte Business Journal .

In a sign of the times — with many buyers waiving contingencies and home inspections — the family who bought our old house wrote my parents a letter when they submitted an offer, expressing their vision of raising their two young children there. It felt like we were passing our house down to a family with kids who would grow up there, just like my brothers and I had.

My parents bought a house about 10 minutes away, and we were set to move the first week of August. This coincided with the last week of my summer internship and was exactly one week before I was set to move back to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to start my junior year of college.

Packing was the worst part. I tried to keep everything organized, but as I continued to put off the task, I ended up throwing everything into brown boxes, refusing to think about the experience of unpacking it all.

On the last day, everything was bare. The furniture was gone, the closets were empty and it didn’t even look like a home anymore. My best friend came over to help me move the essentials, and so she could get one last look at the house that was the backdrop of our friendship.

I recorded a video while walking through each of the rooms. I remember being so terrified that I’d forget what it looked like. I took a picture with my parents in front of our green door. I’m smiling, but there are tears on my cheeks.

I took a picture with my parents in front of our green door. I’m smiling, but there are tears on my cheeks.

Moving into the new house was a blur. Breaking news meant that I was constantly glued to my computer as the university desk editor of The Daily Tar Heel, and I barely looked up to notice what the new house looked like. My room remained filled with boxes, with just a desk for work and a bed to sleep in. I’ll unpack later, I remember telling myself.

My brothers were ecstatic about the move. The new house meant more space and a flat driveway, so they could finally set up a basketball hoop outside. For them, the new house looked like a brand new playground. To me, I felt like I was finally leaving one.

But then I moved into my first college apartment the next week. And it wasn’t until winter break that I finally went back home. I told myself that I was too busy to visit, which was true. But there was a part of me that worried that “going home” just wouldn’t feel like being home.

Making a house a home

Due to the pandemic, our winter break that year was long, almost double its normal length. When I got home, the room I had left, sparse and filled with cardboard boxes, was gone. My mom had unpacked everything, even down to setting up my bookshelf and filling it. She found a painting of a blue flower at Home Goods and hung it behind my bed. She put old canvases I had made on the opposite walls and turned the room into something comfortable.

But I didn’t see the physical space. What I saw was my mother’s love and care, wanting to make sure that this new house wasn’t just my family’s home, but mine as well. She always says her favorite times are when we are all under the same roof.

And I realized that’s why I loved my old house so much. Because it marked the place where we all sheltered together in one space, just a few feet away from each other. College took that away. Then a pandemic gave it back. And I perceived moving as taking it away again.

Over that break, I started my first book stack right beside my bed — the first of many. I hung up pictures on the wall and organized my shelves. I moved my desk and ordered my clothes by style, the way I like it.

It marked the first change toward becoming my room in the new house — the house that kept my family together under one roof, and the place I can always come home to.

Maddie Ellis is a weekend editor at TODAY Digital.

As the mom to a neurodivergent child, seeing Gus Walz in the spotlight gives me courage

Everyone told me I was ‘so tiny’ when I was pregnant. Here’s why that’s not OK

After my daughter beat cancer, I wanted to control her entire life. Then she went to college

Joining the infertility community is complicated. Leaving it can be, too

The lasting power of ‘Sweet Valley Twins’: How my daughter and I are connecting over the series

I wasn’t anxious about back-to-school because of my kids. It was the other moms

Like Colin Farrell, I have a son with Angelman syndrome. What I wish I'd known

Dear daughter: Why you’re not getting a phone until high school

I’m child-free by choice. It’s time to change the narrative of what that means

I kept my first marriage a secret from my kids. I wish I'd just told them truth

- 5 Best Tips to Prepare for NAATI CCL Test in Australia

- Mistakes to Avoid During NAATI CCL Test

- How to Improve Listening Score before the IELTS Exam?

- 4 Tips and Examples for IELTS Essay Writing

- 5 IELTS Reading Tips

Example essay on Moving to a New House

Moving to a new house is an equally difficult experience for youngsters or maybe even more than the children because children have more ability and natural excitement which help them cope up with the new changes in their lifestyles and environment. Whether it’s a new town, city, or a county, the decision of moving to a new house itself is one of the huge transformations in one’s life. Children usually take less time in breaking the old attachments and establishing new ones. While on the other side, the youngster may take more than the expected time to get used to of their new surroundings and people.

Communication, Choice, and Excitement

It is really important for both the parents and children to offer helping hands and have open communication with each other after moving to a new house. As a parent, I would suggest to allow children to talk about the difficulties they are facing currently to give them the confidence that they are not alone in anything.

It might be equally helpful for the children if their parents ask them about their “choices” of color, paint, or any little accessory of the home. It would make them feel that they somehow have some control over the entire process of moving into an entirely new home and place. Moreover, the fear of the unknown is quite natural and common which needs to be transformed into excitement by making a visit to new places and people.

Celebrations & Memories

Parents or siblings can throw a goodbye party at their old home before leaving the place to be able to acknowledge the fact gracefully that they are about to leave. Similarly, it is suggested to make celebrations with your family at your new place as well to create beautiful memories.

Since your family members are the people who are the closest to you in the entire world, you must help the shy and reserved ones among you by making their social life interactions easier and fun for them.

Shortcomings & Perks

Since every new place is different from the previous one, it is quite natural to focus on the shortcomings of your new home and area. As in my case, the shortcomings include a long distance from the work, shortage of water, and no parking space. But what I noticed is that you should focus on the perks instead which you were not able to enjoy in your old home.

I sat down and realized the beautiful greenery, fresh air and environment of my new home where I can spend a lot of quality and relaxing time in my lawn. It is equally important to try to fix the shortcomings to add as much convenience to your life as possible.

So, the decision of moving to a new home is just like a rollercoaster ride in which you experience different emotional phases at different points. However, the need of the hour is to make new attachments, relations, and restart everything thinking that you are gifted with a new life.

- Example essay on My Favorite City New York

- Sample essay on the Invasion of Privacy in This Digital World

You May Also Like

Essay on the Importance of Saving Water

Sample Essay on Election

Essay on Disease Control

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2024

Exploring the impact of housing insecurity on the health and wellbeing of children and young people in the United Kingdom: a qualitative systematic review

- Emma S. Hock 1 ,

- Lindsay Blank 1 ,

- Hannah Fairbrother 1 ,

- Mark Clowes 1 ,

- Diana Castelblanco Cuevas 1 ,

- Andrew Booth 1 ,

- Amy Clair 2 &

- Elizabeth Goyder 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 2453 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Housing insecurity can be understood as experiencing or being at risk of multiple house moves that are not through choice and related to poverty. Many aspects of housing have all been shown to impact children/young people’s health and wellbeing. However, the pathways linking housing and childhood health and wellbeing are complex and poorly understood.

We undertook a systematic review synthesising qualitative data on the perspectives of children/young people and those close to them, from the United Kingdom (UK). We searched databases, reference lists, and UK grey literature. We extracted and tabulated key data from the included papers, and appraised study quality. We used best fit framework synthesis combined with thematic synthesis, and generated diagrams to illustrate hypothesised causal pathways.

We included 59 studies and identified four populations: those experiencing housing insecurity in general (40 papers); associated with domestic violence (nine papers); associated with migration status (13 papers); and due to demolition-related forced relocation (two papers). Housing insecurity took many forms and resulted from several interrelated situations, including eviction or a forced move, temporary accommodation, exposure to problematic behaviour, overcrowded/poor-condition/unsuitable property, and making multiple moves. Impacts included school-related, psychological, financial and family wellbeing impacts, daily long-distance travel, and poor living conditions, all of which could further exacerbate housing insecurity. People perceived that these experiences led to mental and physical health problems, tiredness and delayed development. The impact of housing insecurity was lessened by friendship and support, staying at the same school, having hope for the future, and parenting practices. The negative impacts of housing insecurity on child/adolescent health and wellbeing may be compounded by specific life circumstances, such as escaping domestic violence, migration status, or demolition-related relocation.

Housing insecurity has a profound impact on children and young people. Policies should focus on reducing housing insecurity among families, particularly in relation to reducing eviction; improving, and reducing the need for, temporary accommodation; minimum requirements for property condition; and support to reduce multiple and long-distance moves. Those working with children/young people and families experiencing housing insecurity should prioritise giving them optimal choice and control over situations that affect them.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The impacts of socioeconomic position in childhood on adult health outcomes and mortality are well documented in quantitative analyses (e.g., [ 1 ]). Housing is a key mechanism through which social and structural inequalities can impact health [ 2 ]. The impact of housing conditions on child health are well established [ 3 ]. Examining the wellbeing of children and young people within public health overall is of utmost importance [ 4 ]. Children and young people (and their families) who are homeless are a vulnerable group with particular difficulty in accessing health care and other services, and as such, meeting their needs should be a priority [ 5 ].

An extensive and diverse evidence base captures relationships between housing and health, including both physical and mental health outcomes. Much of the evidence relates to the quality of housing and specific aspects of poor housing including cold and damp homes, poorly maintained housing stock or inadequate housing leading to overcrowded accommodation [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. The health impacts of housing insecurity, together with the particular vulnerability of children and young people to the effects of not having a secure and stable home environment, continue to present a cause for increased concern [ 7 , 8 , 11 , 14 ]. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Reviews (PHR) Programme commissioned the current review in response to concerns about rising levels of housing insecurity and the impact of housing insecurity on the health and wellbeing of children and young people in the United Kingdom (UK).

Terminology and definitions related to housing insecurity

Numerous diverse terms are available to define housing insecurity, with no standard definition or validated instrument. For the purpose of our review, we use the terminology and definitions used by the Children’s Society, which are comprehensive and based directly on research with children that explores the relationship between housing and wellbeing [ 15 ]. They use the term “housing insecurity” for those experiencing and at risk of multiple moves that are (i) not through choice and (ii) related to poverty [ 15 ]. This reflects their observation that multiple moves may be a positive experience if they are by choice and for positive reasons (e.g., employment opportunities; moves to better housing or areas with better amenities). This definition also acknowledges that the wider health and wellbeing impacts of housing insecurity may be experienced by families that may not have experienced frequent moves but for whom a forced move is a very real possibility. The Children’s Society definition of housing insecurity encompasses various elements (see Table 1 ).

Housing insecurity in the UK today – the extent of the problem

Recent policy and research reports from multiple organisations in the UK highlight a rise in housing insecurity among families with children [ 19 , 22 , 23 ]. Housing insecurity has grown following current trends in the cost and availability of housing, reflecting in particular the rapid increase in the number of low-income families with children in the private rental sector [ 19 , 22 , 24 ], where housing tenures are typically less secure. The ending of a tenancy in the private rental sector was the main cause of homelessness given in 15,500 (27% of claims) of applications for homelessness assistance in 2017/18, up from 6,630 (15% of claims) in 2010/11 for example [ 25 ]. The increased reliance on the private rented sector for housing is partly due to a lack of social housing and unaffordability of home ownership [ 23 ]. The nature of tenure in the private rental sector and gap between available benefits and housing costs means even low-income families that have not experienced frequent moves may experience the negative impacts of being at persistent risk of having to move [ 26 ]. Beyond housing benefit changes, other changes to the social security system have been linked with increased housing insecurity. The roll-out of Universal Credit Footnote 1 , with its built-in waits for payments, has been linked with increased rent arrears [ 27 , 28 ]. The introduction of the benefit cap, which limits the amount of social security payments a household can receive, disproportionately affects housing support and particularly affecting lone parents [ 29 , 30 , 31 ].

The increase in families experiencing housing insecurity, including those living with relatives or friends (the ‘hidden homeless’) and those in temporary accommodation provided by local authorities, are a related consequence of the lack of suitable or affordable rental properties, which is particularly acute for lone parents and larger families. The numbers of children and young people entering the social care system or being referred to social services because of family housing insecurity contributes further evidence on the scale and severity of the problem [ 32 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated housing insecurity in the UK [ 24 ], with the impacts continuing to be felt. In particular, the pandemic increased financial pressures on families (due to loss of income and increased costs for families with children/young people at home). These financial pressures were compounded by a reduction in informal temporary accommodation being offered by friends and family due to social isolation precautions [ 24 ]. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the risks to health posed by poor housing quality (including overcrowding) and housing insecurity [ 24 , 33 ]. Recent research with young people in underserved communities across the country also highlighted their experience of the uneven impact of COVID-19 for people in contrasting housing situations [ 34 ].

While the temporary ban on bailiff-enforced evictions, initiated due to the pandemic, went some way towards acknowledging the pandemic’s impact on housing insecurity, housing organisations are lobbying for more long-term strategies to support people with pandemic-induced debt and rent-arrears [ 33 ]. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has warned of the very real risk of a ‘two-tier recovery’ from the pandemic, highlighting the ‘disproportionate risks facing people who rent their homes’ ([ 35 ], para. 1). Their recent large-scale survey found that one million renting households worry about being evicted in the next three months, and half of these were families with children [ 35 ]. The survey also found that households with children, renters from ethnic minority backgrounds and households on low incomes are disproportionately affected by pandemic-induced debt and rent arrears [ 35 ].

The cost-of-living crisis is exacerbating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with many households experiencing or set to experience housing insecurity due to relative reductions in income accompanying increases in rent and mortgage repayments [ 36 ]. People experiencing or at risk of housing insecurity are disproportionately affected, due to higher food and utility costs [ 37 ].

Research evidence on relationships between housing in childhood and health

Housing is a key social determinant of health, and a substantive evidence base of longitudinal cohort studies and intervention studies supports a causal relationship between the quality, affordability and stability of housing and child health [ 38 ]. Evidence includes immediate impacts on mental and physical health outcomes and longer-term life course effects on wider determinants of health including education, employment and income as well as health outcomes [ 39 ].

The negative health impact of poor physical housing conditions has been well documented [ 40 , 41 ]. Housing instability and low housing quality are associated with worse psychological health among young people and parents [ 42 , 43 ]. The UK National Children’s Bureau [ 22 ] draws attention to US-based research showing that policies that reduced housing insecurity for young children can help to improve their emotional health [ 44 ], and that successful strategies for reducing housing insecurity have the potential to reduce negative outcomes for children with lived experience of housing insecurity, including emotional and behavioural problems, lower academic attainment and poor adult health and wellbeing [ 45 ]. A variety of pathways have been implicated in the relationship between housing insecurity and child health and wellbeing, including depression and psychological distress in parents, material hardships and difficulties in maintaining a good bedtime routine [ 38 ]. Frequent moves are also associated with poorer access to preventive health services, reflected, for example, in lower vaccination rates [ 46 , 47 ].

Housing tenure, unstable housing situations and the quality or suitability of homes are inter-related [ 48 ]. For example, if families are concerned that if they lost their home they would not be able to afford alternative accommodation, they may be more likely to stay in smaller or poor-quality accommodation or in a neighbourhood where they are further from work, school or family support. In this way, housing insecurity can lead to diverse negative health and wellbeing impacts relating to housing and the neighbourhoods, even if in the family does not experience frequent moves or homelessness [ 49 ]. Thus, the relationship between housing insecurity and child health is likely to be complicated by the frequent coexistence of poor housing conditions or unsuitable housing with housing insecurity. The relationship between unstable housing situations and health outcomes is further confounded by other major stressors, such as poverty and changes in employment and family structure, which may lead to frequent moves.

The evidence from cohort studies that show a relationship between housing insecurity, homelessness or frequent moves in childhood and health related outcomes can usefully quantify the proportion of children/young people and families at risk of poorer health associated with housing instability. It can, however, only suggest plausible causal associations. Further, the ‘less tangible aspects of housing’ such as instability are poorly understood [ 40 ]. Additional (and arguably stronger) evidence documenting the relationship between housing insecurity and health/wellbeing comes from the case studies and qualitative interviews with children and young people and families that explore the direct and indirect impacts of housing insecurity on their everyday lives and wellbeing. Thus, the current review aimed to identify, appraise and synthesise research evidence that explores the relationship between housing insecurity and the health and wellbeing among children and young people. We aimed to highlight the relevant factors and causal mechanisms to make evidence-based recommendations for policy, practice and future research priorities.

We undertook a systematic review synthesising qualitative data, employing elements of rapid review methodology in recognition that the review was time-constrained. This involved two steps: (1) a single screening by one reviewer of titles and abstracts, with a sample checked by another reviewer; and (2) a single data extraction and quality assessment, with a sample checked by another reviewer) [ 50 , 51 , 52 ]. The protocol is registered on the PROSPERO registry, registration number CRD42022327506.

Search strategy

Searches of the following databases were conducted on 8th April 2022 (from 2000 to April 2022): MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO (via Ovid); ASSIA and IBSS (via ProQuest) and Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science). Due to the short timescales for this project, searches aimed to balance sensitivity with specificity, and were conceptualised around the following concepts: (housing insecurity) and (children or families) and (experiences); including synonyms, and with the addition of a filter to limit results to the UK where available [ 53 ]. To expedite translation of search strings across different databases, searches prioritised free text search strings (including proximity operators), in order to retrieve relevant terms where they occurred in titles, abstracts or any other indexing field (including subject headings). The searches of ASSIA and IBSS (via ProQuest) and Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science) used a simplified strategy adapted from those reproduced in Additional File 1. Database searching was accompanied by scrutiny of reference lists of included papers and relevant systematic reviews (within search dates), and grey literature searching (see Supplementary Table 1, Additional File 2), which was conducted and documented using processes outlined by Stansfield et al . [ 54 ].

Inclusion criteria

We included qualitative studies, including qualitative elements of mixed methods studies from published and grey literature (excluding dissertations and non-searchable books), that explored the impact of housing insecurity, defined according to the Children’s Society [ 15 ] definition (which includes actual or perceived insecurity related to housing situations), on immediate and short-term outcomes related to childhood mental and physical health and wellbeing (up to the age of 16), among families experiencing / at risk of housing insecurity in the UK (including low-income families, lone-parent families, and ethnic minority group families including migrants, refugees and asylum seekers). Informants could include children and young people themselves, parents / close family members, or other informants with insight into the children and young people’s experiences. Children and young people outside a family unit (i.e., who had left home or were being looked after by the local authority) and families from Roma and Irish Traveller communities were excluded, as their circumstances are likely to differ substantially from the target population.

Study selection

Search results from electronic databases were downloaded to a reference management application (EndNote). The titles and abstracts of all records were screened against the inclusion criteria by one of three reviewers and checked for agreement by a further reviewer. Full texts of articles identified at abstract screening were screened against the inclusion criteria by one reviewer. A proportion (10%) of papers excluded at the full paper screening stage were checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Grey literature searches and screening were documented in a series of tables [ 54 ]. One reviewer (of two) screened titles of relevant web pages and reports against the inclusion criteria for each web platform searched, and downloaded and screened the full texts of potentially eligible titles. Queries relating to selection were checked by another reviewer, with decisions discussed among the review team until a consensus was reached.

One reviewer (of two) screened reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews for potentially relevant papers. One reviewer downloaded the abstracts and full texts of relevant references and assessed them for relevance.

Data extraction

We devised a data extraction form based on forms that the team has previously tested for similar reviews of public health topics. Three reviewers piloted the extraction form and suggested revisions were agreed before commencing further extraction. Three reviewers extracted and tabulated key data from the included papers and grey literature sources, with one reviewer completing data extraction of each study and a second reviewer formally checking a 10% sample for accuracy and consistency. The following data items were extracted: author and year, location, aims, whether housing insecurity was an aim, study design, analysis, who the informants were, the housing situation of the family, reasons for homelessness or housing insecurity, conclusion, relevant policy/practice implications and limitations. Any qualitative data relating to housing insecurity together with some aspect of health or wellbeing in children and young people aged 0–16 years were extracted, including authors’ themes (to provide context), authors’ interpretations, and verbatim quotations from participants. We sought to maintain fidelity to author and participant terminologies and phrasing throughout.

Quality appraisal

Peer-reviewed academic literature was appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies [ 55 ] and the quality of grey literature sources (webpages and reports) was appraised using the Authority, Accuracy, Coverage, Objectivity, Date, Significance (AACODS) checklist [ 56 ]. Because of concerns about the lack of peer review and/or the absence of a stated methodology, it was decided to use the AACODS tool that extends beyond simple assessment of study design. A formal quality assessment checklist was preferred for journal articles that passed these two entry criteria. One reviewer performed quality assessment, with a second reviewer formally checking a 10% sample for accuracy and consistency.

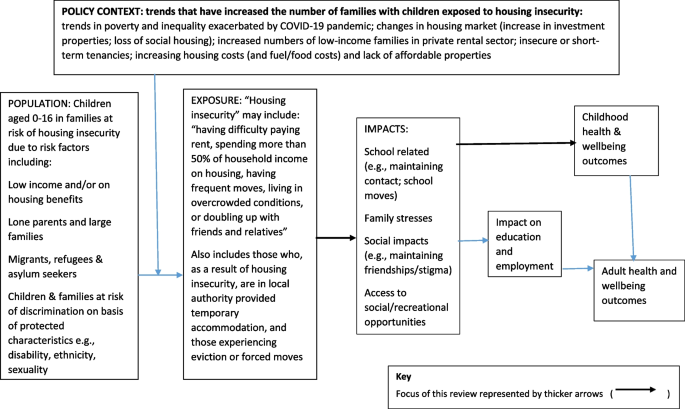

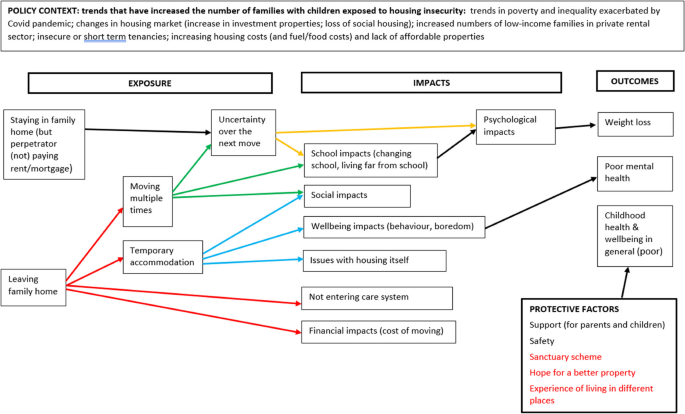

Development of the conceptual framework

Prior to undertaking the current review, we undertook preliminary literature searches to identify an appropriate conceptual framework or logic model to guide the review and data synthesis process. However, we were unable to identify a framework that specifically focused on housing insecurity among children and young people and that was sufficiently broad to capture relevant contexts, exposures and impacts. We therefore developed an a priori conceptual framework based on consultation with key policy and practice stakeholders and topic experts and examination of key policy documents (see Fig. 1 ).

A priori conceptual framework for the relationship between housing insecurity and the health and wellbeing of children and young people

We initially consulted policy experts who identified relevant organisations including research centres, charities and other third sector organisations. We obtained relevant policy reports from organisational contacts and websites, including Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), Crisis, Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) and HACT (Housing Association Charitable Trust), NatCen (People Living in Bad Housing, 2013), the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE), and the Centre on Household Assets and Savings Management (CHASM) (Homes and Wellbeing, 2018). We also identified a key report on family homelessness from the Children’s Commissioner (Bleak Houses. 2019) and a joint report from 11 charities and advocacy organisations published by Shelter (Post-Covid Policy: Child Poverty, Social Security and Housing, 2022). We also consulted local authority officers with responsibility for housing and their teams in two local councils and third sector providers of housing-related support to young people and families (Centrepoint). Stakeholders and topic experts were invited to comment on the potential focus of the review and the appropriate definitions and scope for the ‘exposure’ (unstable housing), the population (children and young people) and outcomes (health and wellbeing). Exposures relate to how children and families experience housing insecurity, impacts are intermediate outcomes that may mediate the effects of housing insecurity on health and wellbeing (e.g., the psychological, social, and environmental consequences of experiencing housing insecurity), and outcomes are childhood health and wellbeing effects of housing insecurity (including the effects of the impacts/intermediate outcomes).

The contextual factors and main pathways between housing-related factors and the health and wellbeing of children and young people identified were incorporated into the initial conceptual framework. We then used this conceptual framework to guide data synthesis.

Data synthesis

We adopted a dual approach whereby we synthesised data according to the a priori conceptual framework and sought additional themes, categories and nuance inductively from the data, in an approach consistent with the second stage of ‘best fit framework synthesis’ [ 57 , 58 ]. We analysed inductive themes using the Thomas and Harden [ 59 ] approach to thematic synthesis, but coded text extracts (complete sentences or clauses) instead of coding line by line [ 60 , 61 ].

First, one reviewer (of two) coded text extracts inductively and within the conceptual framework, simultaneously, linking each relevant text extract to both an inductive code based on the content of the text extract, and to an element of the conceptual framework. We assigned multiple codes to some extracts, and the codes could be linked to any single element or to multiple elements of the conceptual framework. During the process of data extraction, we identified four distinct populations, and coded (and synthesised) data discretely for each population. We initially coded data against the ‘exposure’, ‘impacts’ and ‘outcomes’ elements of the conceptual framework, however we subsequently added a further element within the data; ‘protective factors’. One reviewer then examined the codes relating to each element of the conceptual framework and grouped the codes according to conceptual similarity and broader meaning, reporting the thematic structure and relationships between concepts apparent from the text extracts both narratively and within a diagram to illustrate hypothesised causal pathways within the original conceptual framework, to highlight links between specific exposures, impacts and outcomes for each population. While we synthesised the findings by population initially, and present separate diagrams for each population, we present overall findings in this manuscript due to several similarities and then highlight any important differences for the domestic violence, migrant/refugee/asylum seeker, and relocation populations.

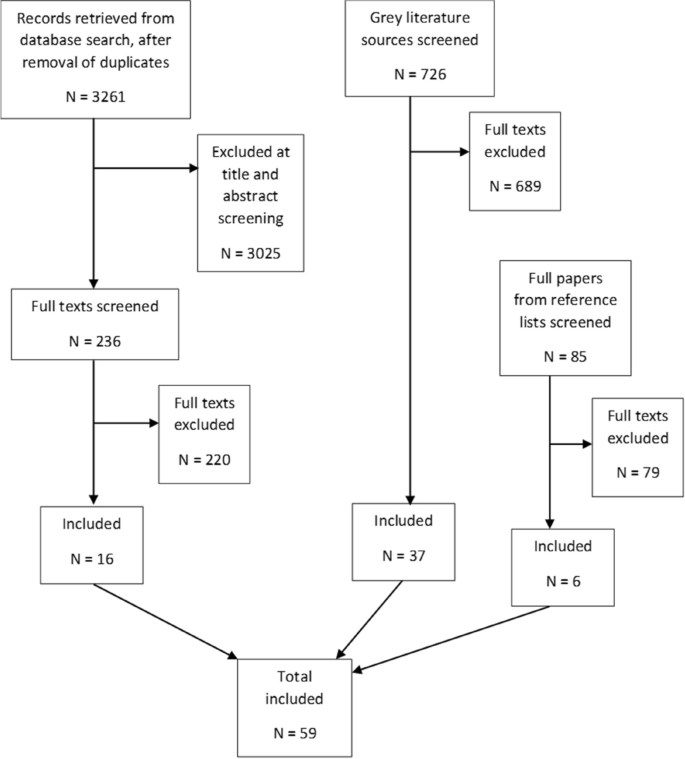

Study selection and included studies

Here we report the results of our three separate searchers. First, the database searches generated 3261 records after the removal of duplicates. We excluded 3025 records after title and abstract screening, examined 236 full texts, and included 16 peer-reviewed papers (reporting on 16 studies). The reasons for exclusion of each paper are provided in the Supplementary Table 2, Additional File 3. Second, we examined 726 grey literature sources (after an initial title screen) and included 37 papers. Third, we examined 85 papers that we identified as potentially relevant from the references lists of included papers and relevant reviews, and included six (two of which were peer-reviewed publications). Figure 2 summarises the process of study selection and Table 2 presents a summary of study characteristics. Of the included studies, 16 took place across the UK as a whole, one was conducted in England and Scotland, one in England and Wales and 17 in England. In terms of specific locations, where these were reported, 13 were reported to have been conducted in London (including specific boroughs or Greater London), two in Birmingham, one in Fife, two in Glasgow, one in Leicester, one in Rotherham and Doncaster, and one in Sheffield. The location of one study was not reported (Table 2 ).

Flow diagram of study selection

We identified four distinct populations for which research evidence was available during the process of study selection and data extraction:

General population (evidence relating to housing insecurity in general) (reported in 40 papers);

Domestic violence population (children and young people experiencing housing insecurity associated with domestic violence) (reported in nine papers);

Migrant, refugee and asylum seeker population (children and young people experiencing housing insecurity associated with migration status) (reported in 13 papers);

Relocation population (evidence relating to families forced to relocate due to planned demolition) (reported in two papers).

Evidence relating to each of these populations was synthesised separately as the specific housing circumstances may impact health and wellbeing differently and we anticipated that specific considerations would relate to each population. Some studies reported evidence for more than one population.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence varied across the studies, with published literature generally being of higher quality than grey literature and containing more transparent reporting of methods, although reporting of methods of data collection and analysis varied considerably within the grey literature. All 18 peer-reviewed studies reported an appropriate methodology, addressing the aim of the study with an adequate design. Eleven of the 18 peer-reviewed studies reported ethical considerations, and only two reported reflexivity. Most studies had an overall assessment of moderate-high quality (based on the endorsement of most checklist items) and no studies were excluded based on quality. Most of the grey literature originated from known and valued sources (e.g., high-profile charities specialising in poverty and housing, with the research conducted by university-based research teams). Although methodologies and methods were often poorly described (or not at all), primary data in the form of quotations was usually available and suitable to contribute to the development of themes within the evidence base as a whole. Quality appraisals of included studies are presented in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, Additional File 4.

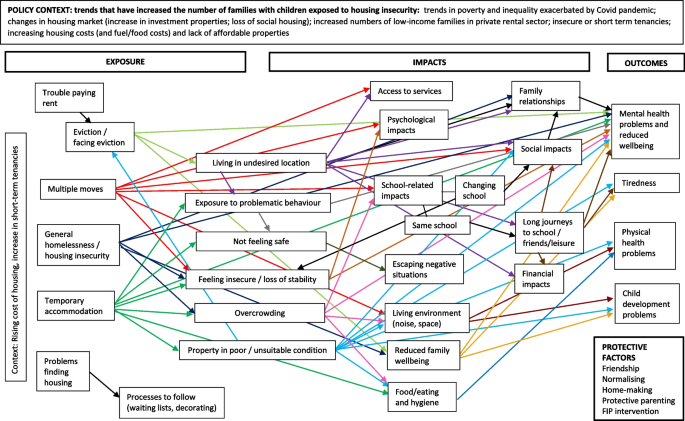

Housing insecurity and the health and wellbeing of children and young people

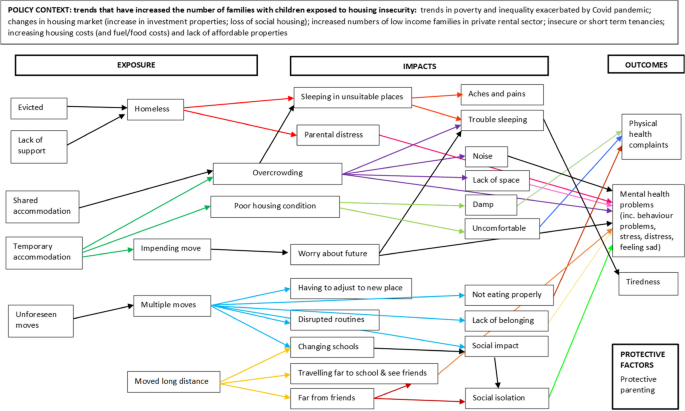

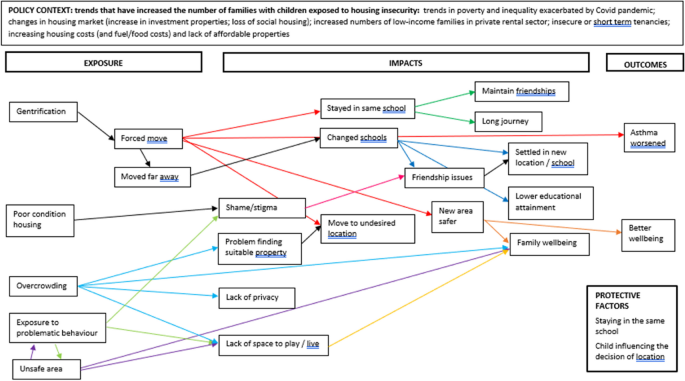

The updated conceptual framework for the impact of housing insecurity on the health and wellbeing of children aged 0–16 years in family units is presented in Fig. 3 for the general population, Fig. 4 for the domestic violence population, Fig. 5 for the refugee/migrant/asylum seeker population, and Fig. 6 for the relocation population (arrows represent links identified in the evidence and coloured arrows are used to distinguish links relating to each element of the model). Table 3 outlines the themes, framework components and studies reporting data for each theme.

Conceptual framework for the relationship between housing insecurity and health and wellbeing in the general population

Conceptual framework for the relationship between housing insecurity and health and wellbeing in the domestic violence population

Conceptual framework for the relationship between housing insecurity and health and wellbeing in the migrant, refugee and asylum seeker population

Conceptual framework for the relationship between housing insecurity and health and wellbeing in the relocation population

Exposures are conceptualised as the manifestations of housing insecurity – that is, how the children and young people experience it – and housing insecurity was experienced in multiple and various ways. These included trouble paying for housing, eviction or the prospect of eviction, making multiple moves, living in temporary accommodation, and the inaccessibility of suitable accommodation.

Fundamentally, a key driver of housing insecurity is poverty. Parents and, in some cases, young people cited the high cost of housing, in particular housing benefit not fully covering the rent amount [ 116 ], trouble making housing payments and falling into arrears [ 15 , 92 , 97 ]. Sometimes, families were evicted for non-payment [ 15 , 102 ], often linked to the rising cost of housing [ 109 ] or loss of income [ 102 ]. Some children and young people were not aware of reasons for eviction [ 90 ], and the prospect of facing eviction was also a source of housing insecurity [ 116 ].

The cost of housing could lead to families having to move multiple times [ 116 ], with lack of affordability and the use of short-term tenancies requiring multiple moves [ 109 , 116 ]. Children and young people were not always aware of the reasons for multiple moves [ 15 ]. Multiple moves could impact upon education and friendships [ 77 , 82 ].

Living in temporary housing was a common experience of housing insecurity [ 15 , 71 , 87 , 90 , 94 , 98 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 ]. Temporary housing caused worry at the thought of having to move away from school and friends [ 91 ] and acute distress, which manifested as bedwetting, night waking and emotional and behavioural issues at school [ 66 ]. Living in a hostel for a period of time could lead to friendship issues due to not being able to engage in sleepovers with friends [ 102 ].

The inaccessibility of suitable accommodation also contributed to insecurity. Sometimes, when a family needed to move, they had to fulfil certain requirements, for instance, to decorate their overcrowded 3-bedroom accommodation to be eligible for a more suitable property [ 15 ]. Further, some families encountered the barrier of landlords who would not accept people on benefits [ 15 , 85 , 117 ]. Waiting lists for social housing could be prohibitively long [ 97 , 98 , 116 ].

Dual exposures and impacts

Some phenomena were found to be both exposures and impacts of housing insecurity, in that some issues and experiences that were impacts of housing insecurity further exacerbated the living situation, causing further insecurity. These included not feeling safe, exposure to problematic behaviour, living far away from daily activities, overcrowding, and poor or unsuitable condition properties.

Not feeling safe was frequently reported by children and young people, and by parents in relation to the safety of children and young people. Parents and children and young people described being moved to neighbourhoods or localities [ 15 , 69 , 87 , 90 , 103 ] and accommodation [ 87 , 97 , 109 , 112 , 113 , 114 ] that did not feel safe. For one family, this was due to racial abuse experienced by a parent while walking to school [ 69 ]. In one case, a young person’s perception of safety improved over time, and they grew to like the neighbours and area [ 15 ], although this was a rare occurrence.

Often, this experience of being unsafe was due to exposure to problematic behaviour in or around their accommodation, including hearing other children being treated badly [ 112 ], being exposed to violence (including against their parents) [ 111 , 112 , 114 ], witnessing people drinking and taking drugs [ 69 , 83 , 90 , 111 , 112 , 114 ], finding drug paraphernalia in communal areas [ 112 , 114 ] or outside spaces [ 69 ], hearing threats of violence [ 111 ], hearing shouting and screaming in other rooms [ 114 ], witnessing people breaking into their room [ 83 ], and witnessing their parent/s receiving racist abuse and being sworn at [ 83 ].

‘There’s a lot [of] drugs and I don’t want my kids seeing that… One time he said ‘mummy I heard a woman on the phone saying ‘I’m going to set fire to your face’’ She was saying these things and my son was hearing it.’ ( [ 111 ] , p.15)

Another impact related to the family and children and young people being isolated and far away from family, friends, other support networks, work, shops, school and leisure pursuits due to the location of the new or temporary housing [ 15 , 83 , 87 , 97 , 104 , 109 ]. This affected education, friendships, finances and access to services (see ‘ Impacts ’).

Overcrowding was another issue that was both a source or feature of housing insecurity, as this created a need to move, as well as being an impact, in that families moved to unsuitable properties because they had little alternative. Overcrowding was largely a feature of temporary accommodation that was too small for the family [ 67 , 91 ], including hostels/shared houses where whole families inhabited one room and washing facilities were shared [ 100 , 102 ]. In turn, overcrowding could mean siblings sharing a room and/or bed [ 15 , 41 , 64 , 71 , 78 , 109 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 116 ] (which could lead to disturbed sleep [ 15 ]), children/young people or family members sleeping on the floor or sofa [ 15 , 71 , 102 , 110 ] (which caused aches and pains in children/young people; [ 100 ]), children/young people sharing a room with parents [ 64 , 71 , 94 , 109 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 ], a room being too small to carry out day to day tasks [ 112 , 113 , 114 ], a lack of privacy in general (e.g., having to change clothes in front of each other) [ 70 , 111 , 112 , 114 ], living in close proximity to other families [ 114 ], and cramped conditions with little room to move when too many people and possessions had to share a small space [ 15 , 64 , 90 , 97 , 103 , 109 , 114 ].

It’s all of us in one room, you can imagine the tension…. everyone’s snapping because they don’t have their own personal space …it’s just a room with two beds. My little brother has to do his homework on the floor.’ ( [ 97 ] , p..43)

It was thus difficult for children and young people to have their own space, even for a short time [ 98 ], including space to do schoolwork [ 102 , 103 ], play [ 91 ] or invite friends over [ 103 ]. Families sometimes ended up overcrowded due to cohabiting with extended family [ 110 ] or friends [ 91 , 102 ] (‘hidden homelessness’). Other families outgrew their property, or anticipated they would in future, when children grew older [ 70 , 116 ]. Overcrowding sometimes meant multiple families inhabiting a single building (e.g., a hostel or shelter), where single parents had difficulties using shared facilities, due to not wanting to leave young children alone [ 100 ]. Overcrowding could also lead to children feeling unsafe, including being scared of other people in shared accommodation [ 102 ], experiencing noise [ 102 ], and feeling different from peers (due to not having their own room or even bed) [ 102 ]. Living in overcrowded conditions could lead to, or exacerbate, boredom, aggressive behaviour, and mental health problems among children and young people (see ‘ Outcomes ’) [ 72 , 79 , 91 ]. Overcrowded conditions caused a ‘relentless daily struggle’ for families ([ 83 ], p.48).

Similarly, the need to take whatever property was on offer led to families living in properties in poor condition, which in turn could exacerbate housing insecurity, both because families needed to escape the poor condition housing and because they were reluctant to complain and ask for repairs on their current property in case the landlord increased the rent or evicted them [ 86 , 96 ]. Eviction was perceived as a real threat and families described being evicted after requesting environmental health issues [ 74 ] and health and safety issues [ 116 ] be addressed. Families experienced issues relating to poor condition properties, including accommodation being in a poor state of decoration [ 98 ], broken or barely useable fixtures and fittings [ 86 , 90 , 96 ], no laundry or cooking facilities [ 102 ], no electricity [ 67 ], no or little furniture [ 67 , 102 ], broken appliances [ 71 , 96 , 97 ], structural failings [ 97 ], unsafe gardens [ 90 ], mould [ 71 , 90 , 96 , 97 , 104 , 109 ], and bedbugs and/or vermin [ 67 , 76 , 77 ]. Even where the property condition was acceptable, accommodation could be unsuitable in other ways. Many families with young children found themselves living in upper floor flats, having to navigate stairs with pushchairs and small children [ 71 , 74 , 78 , 83 , 87 , 92 , 109 ]. One study reported how a family with a child who had cerebral palsy and asthma were refused essential central heating and so had to request a property transfer [ 75 ]. Lack of space to play was a particular issue in relation to temporary accommodation, often due to overly small accommodation or a vermin infestation [ 80 , 87 , 91 ]. In small children, the effects included health and safety risks [ 87 , 112 ] and challenges keeping them occupied [ 112 ]. In older children and young people, a lack of space meant a lack of privacy [ 63 , 112 ]. School holidays could be particularly challenging, particularly when outside play spaces were unsuitable due to safety concerns (e.g., people selling drugs, broken glass) [ 87 , 106 ], and some temporary accommodation restricted access during the daytime [ 112 ]. With shared temporary accommodation, such as a refuge or hostel, came the threat of possessions being removed by others [ 80 ].

Impacts are defined here as intermediate outcomes that may mediate the effects of housing insecurity on health and wellbeing, for instance, the psychological, social, and environmental consequences of experiencing housing insecurity. According to the evidence reviewed, these were overwhelmingly negative, with only a very small number of positive impacts, and, in many cases, these were offset by other negative impacts. Impacts on friendships, education, family relationships, diet, hygiene, access to services, feelings of being different, feelings of insecurity, parental wellbeing, the financial situation of the family, experiences of noise, leaving negative situations behind, and other impacts, such as leaving pets behind and time costs, were noted. Overlaying all of the above was a lack of choice and control experienced by the children/young people and their families.

A particularly large and disruptive impact of housing insecurity was the effect on friendships and social networks. Over multiple moves, children and young people faced the challenge of building new social networks and reputations each time [ 15 , 90 , 106 ], and worried about maintaining existing friendships [ 90 ]. The beneficial side to this was the potential to have friends all over town, although this was offset by difficulty in forming close friendships due to frequent moves [ 15 ]. Children and young people in temporary, overcrowded or poor condition accommodation often felt ashamed of their housing and concealed it from their friends [ 15 , 73 , 78 , 111 , 112 , 114 , 115 ], and in one case missing out on sleepovers with friends [ 102 ]. Moving far from friends presented difficulties in maintaining friendships and a social life, leading to boredom and isolation [ 102 , 114 ]. The threat of an impending long-distance move could cause sadness and worry [ 114 ] and young people missed the friends they had left behind [ 15 , 90 ]. Other associated social impacts of housing insecurity exacerbated by the wider experience of poverty included turning turn down invitations to go out with friends for financial reasons [ 115 ] or to avoid leaving a parent alone with younger sibling/s [ 114 ], and feeling different from peers, either because of looking unkempt or lacking in confidence [ 115 ].

Another key impact of housing insecurity was the effect on education, and this was closely intertwined with friendship impacts. Faced with moving, often multiple times, sometimes to uncertain locations, families were faced with the decision to keep the same school or to change schools. Multiple moves and/or an unfeasibly long journey to school, led to either a decision to, or anticipating the prospect of having to, change schools [ 15 , 66 , 90 , 91 , 102 , 106 , 108 , 111 , 116 ]. This could in turn impact on the child’s sense of stability, academic performance and friendships [ 90 , 105 , 106 , 111 , 115 , 116 ] and make them feel sad [ 102 ]. In the case of one family, staying at the same school during a move resulted in decreased educational attainment [ 69 ].

Staying at the same school created some stability and allowed for friendships and connections with teachers and the school to be maintained [ 15 , 102 ]. This was, however, quite often the only option, due to the family not knowing their next location, and thus which school they would be near [ 15 , 102 , 113 ], and was not without issues. Those who were unhappy with school were thus effectively prevented from changing schools due to housing insecurity [ 15 , 90 ]. Families were often re-housed at a considerable distance from the school [ 15 , 70 , 93 , 94 , 113 ]. This meant having to get up very early for a long journey by public transport [ 15 , 66 , 70 , 77 , 88 , 90 , 94 , 102 , 105 , 106 , 111 , 113 ], which also caused problems maintaining friendships [ 115 ], increased tiredness and stress [ 15 , 66 , 77 , 102 , 111 , 113 , 114 , 115 ] and left little time for homework and extra-curricular activities [ 113 , 114 , 115 ]. Some children and young people stayed with friends or relatives closer to school on school nights, although these arrangements were not sustainable longer-term [ 15 , 90 ].

Living in temporary housing was associated with practical challenges in relation to schooling, for instance, keeping track of uniform and other possessions, limited laundry facilities, and limited washing facilities [ 112 , 115 ]. Parents noted academic performance worsened following the onset of housing problems [ 111 , 113 , 116 ]. Limited space and time to do homework or revision [ 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 ], tiredness and poor sleep [ 111 , 113 ], travelling and disrupted routines [ 114 ], disruptions from other families (e.g. in a hostel) [ 114 ], a lack of internet connection [ 114 ], and the general impact of the housing disruption [ 111 , 113 , 116 ] made it challenging for those experiencing housing insecurity to do well at school. Families often had to wake up early to access shared facilities in emergency accommodation before school [ 113 , 114 ]. Some children and young people missed school altogether during periods of transience, due to multiple moves rendering attendance unviable [ 71 , 106 , 111 ], lack of a school place in the area [ 109 ], or not being able to afford transport and lunch money [ 81 ], which in turn affected academic performance [ 106 , 111 ].

‘Their education was put on hold. My daughter was ahead on everything in her class and she just went behind during those two weeks.’ ([ 111 ] , p.15)

Children and young people also experienced an impact on immediate family relationships. Housing insecurity led to reduced family wellbeing [ 82 ], and family relationships becoming more strained, for instance, due to spending more time at friends’ houses that were far away [ 15 ]. In some cases, however, housing insecurity led to improved family relationships, for instance, in terms of a non-resident father becoming more involved [ 15 ], or children feeling closer to their parents [ 106 ].

Some impacts related to the child’s health and wellbeing. Impacts on diet were reported, including refusal of solid food (which affected growth) [ 113 ], stress and repeated moves leading to not eating properly (which resulted in underweight) [ 91 ], insufficient money to eat properly [ 15 , 99 , 106 ], a lack of food storage and preparation space [ 102 , 103 , 112 ], and a hazardous food preparation environment [ 112 ]. Unsuitable temporary accommodation, including converted shipping containers, hostels, B&Bs and poorly maintained houses were particularly likely to be associated with a wide range of other well-being related impacts. Unsuitable accommodation presented various problems, including excessive heat, dripping water, overcrowding, damp, dirt, electrical hazards, vermin, flooding and a lack of washing and laundry facilities [ 41 , 67 , 71 , 74 , 76 , 77 , 81 , 87 , 88 , 102 , 104 , 106 , 109 , 112 , 116 ]. Moving could also impact on access to services and continuity of care, including being unable to register with general practitioners [ 82 ], and difficulty in maintaining continuity of medical care [ 65 ].

Psychological impacts of housing insecurity included feeling different from peers [ 115 ], feeling disappointed in each new property after being initially hopeful [ 15 ], and having trouble fitting in, in a new area [ 15 ]. Feeling insecure (including uncertainty over when and where the next move will be, or if another move is happening) was a further impact of living in insecure housing situations (including temporary housing, making multiple moves, being evicted) [ 15 , 87 , 90 , 114 , 116 ], leading to stress and worry [ 15 , 114 ].

One of the major issues that [she] says affects her mental health is the uncertainty of their situation. She says it is hard to not know where they will be staying one night to the next. It is also difficult to adjust to living without her furniture and clothes ( [ 114 ] , p.17)

Multiple moves, or anticipating a move, disrupted children and young people’s sense of continuity and led to the experience of a loss of security and stability more generally [ 15 , 85 , 87 ]. This led children and young people to feel responsible for helping and providing support to their parents, including hiding their feelings [ 111 , 114 ], or not requesting things be bought [ 15 , 113 ]. Children and young people also felt a sense of displacement and a lack of belonging [ 15 , 115 ]. Loss of stability and security triggered a desire for stability, to be able to settle, have friends over, and not have to worry about moving [ 109 ].

Housing insecurity also had a negative effect on parent-wellbeing, and this impacted the wellbeing of young people both directly [ 15 , 65 , 102 , 106 ] and indirectly through increased arguments and family stress [ 15 , 93 ] and reduced parental ability to care for children with chronic conditions [ 41 ]. Parents also perceived their reduced wellbeing as negatively impacting their children's development [ 41 ]. The threat of sanctions for missed housing payment could lead to reduced well-being among the whole family, characterised by feelings of despair, failure and a loss of hope [ 93 ].