An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Bioethics Resources for Investigators & Research Ethics Committees

A collection of resources for scientific investigators conducting research in the developing world, and ethics committees reviewing it.

- Guidelines (non-regulatory)

Regulations

Practical aids, research ethics committees, guidelines and regulations.

Guidelines (non-regulatory) Human Subjects Research in General These are the key non-regulatory documents that are likely to be cited by ethicists and research ethics committees. The Nuremberg Code The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects . The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research (USA) PREVENT Project: Pregnant Women & Vaccines Against Emerging Epidemic Threats: Ethics Guidance for Preparedness, Research, and Response , September 2018 HIV/AIDS UNAIDS 2012. Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials National Institutes of Health, USA. NIH Guidance for Addressing the Provision of Antiretroviral Treatment for Trial Participants Following their Completion of NIH-Funded HIV Antiretroviral Treatment Trials in Developing Countries Research in Developing Countries The Nuffield Council. The Ethics of Research Related to Healthcare in Developing Countries . 2002. The Nuffield Council is a UK-based independent body that researches and reports on topical issues in bioethics. They published a follow-up discussion paper on this same topic in 2005. National Bioethics Advisory Commission, USA. Ethical and Policy Issues in International Research: Clinical Trials in Developing Countries . Research in Humanitarian Crises Post-Research Ethics Analysis (PREA) - A research project investigating ethical issues in health research in humanitarian crises. PREA tool - Provides researchers and other stakeholders with a pragmatic tool that assists learning lessons about the actual ethical challenges that develop during health research in humanitarian crises. R2HC Research Ethics Tool Elrha, September 2017 Disasters: Core Concepts and Ethical Theories [Open access] Springer Nature, supported by Disaster Bioethics/COST Action, 2018 Genetics and Genomics Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) - HUGO Ethics Committee . Statements on several issues, including genetics research and benefit sharing. UNESCO. Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights . The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) in the US has guidance on the application of US regulations to genetic research and research on biological samples . See "Coded Private Information," "Biological Specimens," and "Tissue Storage/Repositories." The US National Institutes of Health also have guidance documents relating to Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS). National Bioethics Advisory Commission, USA. Research Involving Human Biological Materials: Ethical Issues and Policy Guidance .

US Regulations Code of Federal Regulations Title 45 Part 46 . Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Title 21 Part 50 Protection Of Human Subjects . A helpful FDA and HHS comparison chart showing the similarities and differences between FDA and HHS regulations. Compilations of National Regulations ClinRegs from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). A central resource for exploring and comparing international clinical research regulations. Global Research Ethics Map . Harvard School of Public Health. As of March 2009, provides guides to the human subjects protections in 11 countries: Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Kuwait, Malawi, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania. From the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) at HHS: International Compilation of Human Research Protections - Lists the approximately 1,100 laws, regulations, and guidelines that govern human subjects research in over 100 countries, as well as standards from a number of international and regional organizations. Compilation of European GDPR guidances as of July 24, 2018 UNESCO Global Ethics Observatory includes a database containing ethics related legislation and guidelines from 34 countries.

- Research Ethics in Epidemics and Pandemics: A Casebook published by PAHO in 2024, free through Springer Open Access.

- WHO's Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR). Standards and Operational Guidance for Ethics Review of Health-Related Research with Human Participants . Provides guidance for setting up and developing standard operating procedures for research ethics committees and ethical review systems.

- Foreign Grants Information . NIH Office of Extramural Research (OER) has a website for foreign applicants and grantees. It goes through the grants process and includes a section on human subjects protections.

- OER also have a page providing HHS and NIH requirements and resources for all members of the extramural community involved in human subjects research

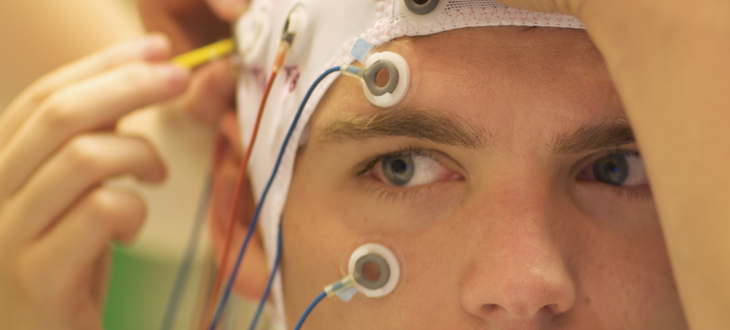

- The Elements of a Successful Informed Consent [Video] created by the Human Subjects Protection Team of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Office of the Clinical Director. This video is intended for use by novice clinical investigators and clinical research staff.

- Global Health Reviewers A "resource for all those involved in the ethical and regulatory review of research, particularly in resource-limited settings. A variety of materials and forums are provided to assist committee members from Ethics Review Committees, Institutional Review Boards, and Food and Drug Administration regulatory committees."

- Iberoamerican Bioethics Network The network, with headquarters at FLACSO-Argentina, has subcoordinator centers in Brazil, Mexico and Spain. The Iberoamerican Bioethics Network is a dependent of the IAB (International Association of Bioethics).

- Inventory of research ethics committees in Africa and for Latin America and the Caribbean From Health Research Web, the inventory includes contact information for each REC.

- IRB Primer: Incidental and Secondary Findings [Archive] From the from the archive of the U.S. Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues , the IRB Primer is designed to help institutional review boards (IRBs) understand and implement the Bioethics Commission's recommendations regarding how to manage incidental and secondary findings ethically in the research setting.

The PAHO Regional Program on Bioethics strengthens the development of bioethics. The program builds capacity in bioethics in the region and support PAHO and Member States in the integration of bioethics in all health-related activities.

- Research Ethics in Africa , by Mariana Kruger, Paul Ndebele, Lyn Horn This free e-book for research ethics committee members focuses on research ethics issues in Africa.

- Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER) A network of independently established regional fora for ethical review committees, health researchers and invited partner organizations with an interest in the development of ethical review. The regional fora are composed of Asia and Western Pacific (FERCAP), former Russian states (FECCIS), Latin America (FLACEIS), Africa (PABIN) and North America (FOCUS).

- Africa - The Pan-African Bioethics Initiative (PABIN) aims to strengthen ethical awareness and discussion across the African continent. They are currently surveying research ethics committees in Africa.

- Asia - The Forum for Ethical Review Committees in Asia and the Western Pacific Region (FERCAP) is a regional organization of researchers and members of ethics review committees.

- Latin America - The Latin American Forum of Research Ethics Committees in Health (FLACEIS) is located at FLACSO-Argentina. From its creation in 2002 there have been three or four lectures each year about issues relevant for research ethics committees.

To view Adobe PDF files, download current, free accessible plug-ins from the Adobe's website .

Updated April 29, 2024

Country selection

Regulatory Authority

Scope of assessment, regulatory fees, ethics committee, scope of review, ethics committee fees, oversight of ethics committees.

Clinical Trial Lifecycle

Submission Process

Submission content, timeline of review, initiation, agreements & registration, safety reporting, progress reporting.

Sponsorship

Definition of Sponsor

Site/investigator selection, insurance & compensation, risk & quality management, data & records management, personal data protection.

Informed Consent

Documentation Requirements

Required elements, participant rights, emergencies, vulnerable populations, children/minors, pregnant women, fetuses & neonates, mentally impaired.

Investigational Products

Definition of Investigational Product

Manufacturing & import, quality requirements, product management, definition of specimen, specimen import & export, consent for specimen, requirements, additional resources.

Information Not Yet Incorporated Into Country Profile:

New FDA Final Rule Issued for Informed Consent Exceptions for Minimal Risk Clinical Investigations The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a final rule , which went into effect on January 22, 2024. The final rule allows an institutional review board (IRB) to waive or alter certain informed consent elements, or waive the informed consent requirement for certain FDA-regulated minimal risk clinical investigations.

Clinical Trials Registries

- ClinicalTrials.gov listing of studies in United States

- International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) consolidated listing of studies in United States

Ethics Committees

- Database of institutional review boards/ethics committees registered with the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)

Funding & Institutions

- World RePORT database of funding organizations, research organizations, and research programs in United States

- HHS OHRP database of institutions with approved Federalwide Assurances (FWAs) for the protection of human subjects

US Profile Updated

Us profile updated in clinregs, united states: ohrp issues guidance for research impacted by covid-19, united states: fda and nih issue guidance for clinical trials impacted by covid-19.

Other Regulatory Databases

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) International Compilation of Human Research Standards for United States

- Health Research Web - United States

This profile covers the role of the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) ’s Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in reviewing and authorizing investigational new drug applications (INDs) to conduct clinical trials using investigational drug or biological products in humans in accordance with the FDCAct , 21CFR50 , and 21CFR312 . Regulatory requirements for federally funded or sponsored human subjects research, known as the Common Rule ( Pre2018-ComRule and RevComRule ), which the HHS and its Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) implements in subpart A of 45CFR46, are also examined. Lastly, additional HHS requirements included in subparts B through E of 45CFR46 are described in this profile, where applicable, using the acronym 45CFR46-B-E . (Please note: ClinRegs does not provide information on state level requirements pertaining to clinical trials.)

Food & Drug Administration

As per the FDCAct , 21CFR50 , and 21CFR312 , the FDA is the regulatory authority that regulates clinical investigations of medical products in the United States (US). According to USA-92 , the FDA is responsible for protecting public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices.

An overview of the FDA structure is available in USA-33 . Several centers are responsible for pharmaceutical and biological product regulation, including the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) . Additionally, per USA-88 , the Office of Clinical Policy (OCLiP) develops good clinical practice and human subject protection policies, regulation, and guidance.

See USA-47 for a list of FDA clinical trials related guidance documents.

Office for Human Research Protections and Common Rule Agencies

Per USA-93 , the OHRP provides leadership in the protection of the rights, welfare, and well-being of human research subjects for studies conducted or supported by the HHS. The OHRP helps ensure this by providing clarification and guidance, developing educational programs and materials, maintaining regulatory oversight, and providing advice on ethical and regulatory issues in biomedical and social-behavioral research.

USA-65 states that the Common Rule ( Pre2018-ComRule and RevComRule ) outlines the basic provisions for institutional ethics committees (ECs) (referred to as institutional review boards (IRBs) in the US), informed consent, and Assurances of Compliance. See USA-65 for a list of US departments and agencies that follow the Common Rule, which are referred to as Common Rule departments/agencies throughout the profile.

The RevComRule applies to all human subjects research that is federally funded or sponsored by a Common Rule department/agency (as identified in USA-65 ), and: 1) was initially approved by an EC on or after January 21, 2019; 2) had EC review waived on or after January 21, 2019; or 3) was determined to be exempt on or after January 21, 2019. (Per USA-55 and USA-74 , the RevComRule is also known as the “2018 Requirements.”) For 2018 Requirements decision charts consistent with the RevComRule , including how to determine if research is exempt, see USA-74 . For more information about the RevComRule , see USA-66 .

Per the RevComRule , the Pre2018-ComRule requirements apply to research funded by a Common Rule department/agency (as identified in USA-65 ) that, prior to January 21, 2019, was either approved by an EC, had EC review waived, or was determined to be exempt from the Pre2018-ComRule . Institutions conducting research approved prior to January 21, 2019 may choose to transition to the RevComRule requirements. The institution or EC must document and date the institution's determination to transition a study on the date the determination to transition was made. The research must comply with the RevComRule beginning on that date. For pre-2018 Requirements decision charts consistent with the Pre2018-ComRule , including how to determine if research is exempt, see USA-74 .

See USA-54 for additional information regarding compliance with the Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule .

USA-65 indicates that the FDA, despite being a part of the HHS, is not a Common Rule agency. Rather, the FDA is governed by its own regulations, including the FDCAct and 21CFR50 . However, the FDA is required to harmonize with the Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule whenever permitted by law.

If a study is funded or sponsored by HHS, and involves an FDA-regulated product, then both sets of regulations will apply. See G-RevComRule-FDA for additional information.

Other Considerations

Per USA-16 , the US is a founding regulatory member of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). The US has adopted several ICH guidance documents, including the E11(R1) Addendum: Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products in the Pediatric Population ( US-ICH-E11 ), E17 General Principles for Planning and Design of Multiregional Clinical Trials ( US-ICH-E17 ), and E6(R2) Good Clinical Practice: Integrated Addendum to ICH E6(R1) ( US-ICH-GCPs ), which are cited throughout this profile.

Contact Information

As per USA-81 , USA-91 , and USA-90 , the contact information for the FDA is as follows:

Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20993 Telephone (general inquiries): (888) 463-6332

CDER Telephone (drug information): (301) 796-3400 CDER Email: [email protected]

CBER Telephone: (800) 835-4709 or (240) 402-8010 CBER Email (manufacturers assistance): [email protected] CBER Email (imports): [email protected] CBER Email (exports): [email protected]

Office for Human Research Protections

Per USA-82 , the contact information for the OHRP is as follows:

Office for Human Research Protections 1101 Wootton Parkway, Suite 200 Rockville, MD 20852 Telephone: (866) 447-4777 or (240) 453-6900 Email (general inquiries): [email protected]

Department of Health & Human Services

According to USA-83 , the contact information for the HHS is as follows:

US Department of Health & Human Services Hubert H. Humphrey Building 200 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20201 Call Center: (877) 696-6775

In accordance with the FDCAct , 21CFR50 , and 21CFR312 , the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has authority over clinical investigations for drug and biological products regulated by the agency. 21CFR312 specifies that the scope of the FDA’s assessment for investigational new drug applications (INDs) includes all clinical trials (Phases 1-4). Based on 21CFR56 and 21CFR312 , institutional ethics committee (EC) review of the proposed clinical investigation may be conducted in parallel with the FDA review of the IND. However, EC approval must be obtained prior to the sponsor being permitted to initiate the clinical trial. (Note: Institutional ECs are referred to as institutional review boards (IRBs) in the United States (US)).

As delineated in 21CFR312 and USA-42 , sponsors are required to submit an IND to the FDA to obtain an agency exemption to ship investigational drug(s) across state lines to conduct drug or biologic clinical trial(s). An IND specifically exempts an investigational drug or biologic from FDA premarketing approval requirements that would otherwise be applicable. 21CFR312 states that “‘IND’ is synonymous with ‘Notice of Claimed Investigational Exemption for a New Drug.’"

According to USA-42 , the FDA categorizes INDs as either commercial or non-commercial (research) and classifies them into the following types:

- Investigator INDs - Submitted by physicians who both initiate and conduct the investigation, and who are directly responsible for administering or dispensing the investigational drug.

- Emergency Use INDs - Enable the FDA to authorize experimental drugs in an emergency situation where normal IND submission timelines cannot be met. Also used for patients who do not meet the criteria of an existing study protocol, or if an approved study protocol does not exist.

- Treatment INDs - Submitted for experimental drugs showing potential to address serious or immediately life-threatening conditions while the final clinical work is conducted and the FDA review takes place.

Per the G-PharmeCTD , non-commercial products refer to products not intended to be distributed commercially and include the above listed IND types.

As indicated in the G-IND-Determination , in general, human research studies must be conducted under an IND if all of the following research conditions apply:

- A drug is involved as defined in the FDCAct

- A clinical investigation is being conducted as defined in 21CFR312

- The clinical investigation is not otherwise exempt from 21CFR312

The G-IND-Determination states that biological products may also be considered drugs within the meaning of the FDCAct .

Further, per 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Determination , whether an IND is required to conduct an investigation of a marketed drug primarily depends on the intent of the investigation and the degree of risk associated with the use of the drug in the investigation. See 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Determination for detailed exemption conditions for marketed drugs.

Clinical Trial Review Process

As delineated in 21CFR312 , the FDA's primary objectives in reviewing an IND are to ensure human participant safety and rights in all phases of the investigation. Phase 1 submission reviews focus on assessing investigation safety, and Phase 2 and 3 submission reviews also include an assessment of the investigation’s scientific quality and ability to yield data capable of meeting marketing approval statutory requirements. An IND may be submitted for one (1) or more phases of an investigation.

As per USA-41 and USA-94 , the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) receive IND submissions for drugs, therapeutic biological products, and other biologicals. Per the FDCAct and 21CFR312 , an IND automatically goes into effect 30 calendar days from receipt, unless the FDA notifies the sponsor that the IND is subject to a clinical hold, or the FDA has notified the sponsor earlier that the trial may begin. A clinical hold is an order the FDA issues to delay or suspend a clinical investigation. If the FDA determines there may be grounds for imposing a clinical hold, an attempt will be made to discuss and resolve any issues with the sponsor prior to issuing the clinical hold order. See 21CFR312 for more information on clinical holds.

According to USA-41 , with respect to sponsor-investigators, once the FDA receives the IND, an IND number will be assigned and the application will be forwarded to the appropriate reviewing division. A letter will be sent to the sponsor-investigator providing notification of the assigned IND number, date of receipt of the original application, address where future submissions to the IND should be sent, and the name and telephone number of the FDA person to whom questions about the application should be directed.

As indicated in 21CFR312 , the FDA may at any time during the course of the investigation communicate with the sponsor orally or in writing about deficiencies in the IND or about the FDA's need for more data or information. Furthermore, on the sponsor's request, the FDA will provide advice on specific matters relating to an IND.

21CFR312 indicates that once an IND is in effect, a sponsor must submit a protocol amendment if intending to conduct a study that is not covered by a protocol already contained in the IND, there is any change to the protocol that significantly affects the safety of subjects, or a new investigator is added to carry out a previously submitted protocol. A sponsor must submit a protocol amendment for a new protocol or a change in protocol before its implementation, while protocol amendments to add a new investigator or to provide additional information about investigators may be grouped and submitted at 30-day intervals. See 21CFR312 for more information on protocol amendments.

As per 21CFR312 , if no subjects are entered into a clinical study two (2) years or more under an IND, or if all investigations under an IND remain on clinical hold for one (1) year or more, the IND may be placed by the FDA on inactive status. An IND that remains on inactive status for five (5) years or more may be terminated. See 21CFR312 for more information on inactive status.

21CFR312 indicates that the FDA may propose to terminate an IND based on deficiencies in the IND or in the conduct of an investigation under an IND. If the FDA proposes to terminate an IND, the agency will notify the sponsor in writing, and invite correction or explanation within a period of 30 days. If at any time the FDA concludes that continuation of the investigation presents an immediate and substantial danger to the health of individuals, the FDA will immediately, by written notice to the sponsor, terminate the IND. See 21CFR312 for more information on FDA termination.

For more information on CDER and CBER internal policies and procedures for accepting and reviewing applications, see USA-96 and USA-95 , respectively.

Expedited Processes

USA-84 further indicates that the FDA has several approaches to making drugs available as rapidly as possible:

- Breakthrough Therapy – expedites the development and review of drugs which may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy

- Accelerated Approval – allow drugs for serious conditions that fill an unmet medical need to be approved based on a surrogate endpoint

- Priority Review – a process by which the FDA’s goal is to take action on an application within six (6) months

- Fast Track – facilitates the development and expedites the review of drugs to treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need

See USA-84 and USA-85 for more information on each process. Additionally, see the FDCAct , as amended by the FDORA , for changes to the accelerated approval process.

The G-RWDRWE-Reg , issued as part of the FDA’s Real-World Evidence (RWE) Program (see USA-17 ), discusses the applicability of the 21CFR312 IND regulations to various clinical study designs that utilize real-world data (RWD). See the G-RWDRWE-Reg for more information.

For information on the appropriate use of adaptive designs for clinical trials and additional information to provide the FDA to support its review, see G-AdaptiveTrials .

For research involving cellular and gene therapy, see the guidance documents at USA-80 .

The Food & Drug Administration (FDA) does not levy a fee to review investigational new drug submissions.

However, per the FDCAct , FDARA , and USA-45 , the FDA has the authority to assess and collect user fees from companies that produce certain human drug and biological products as part of the New Drug Application (NDA). Per USA-43 , the NDA is the vehicle through which drug sponsors formally propose that the FDA approve a new pharmaceutical for sale and marketing in the United States. The data gathered during the animal studies and human clinical trials of an investigational new drug become part of the NDA.

As indicated in 21CFR50 , 21CFR56 , and 21CFR312 , the United States (US) has a decentralized process for the ethics review of clinical investigations. The sponsor must obtain institutional level ethics committee (EC) approval for each study. (Note: Institutional ECs are referred to as institutional review boards (IRBs) in the US.)

As set forth in 21CFR50 , 21CFR56 , and 21CFR312 , all clinical investigations for drug and biological products regulated by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) require institutional EC approval.

The Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule also require that human subjects research receive institutional EC approval. However, note that these regulations’ definition of “human subject” does not include the use of non-identifiable biospecimens. Therefore, the use of non-identifiable biospecimens in research does not, on its own, mandate the application of the Pre2018-ComRule to such research. However, the RevComRule does require federal departments or agencies implementing the policy to work with data experts to reexamine the meaning of “identifiable private information” and “identifiable specimen” within one (1) year of the effective date and at least every four (4) years thereafter. In particular, these agencies will collaboratively assess whether there are analytic technologies or techniques that could be used to generate identifiable private information or identifiable specimens.

(See USA-65 for a list of Common Rule departments/agencies, and the Regulatory Authority section for more information on when the Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule apply to research.)

Per the RevComRule , for non-exempt research (or exempt research that requires limited EC review) reviewed by an EC not operated by the institution doing the research, the institution and the EC must document the institution's reliance on the EC for research oversight and the responsibilities that each entity will undertake to ensure compliance with the RevComRule . Compliance can be achieved in a variety of ways, such as a written agreement between the institution and a specific EC, through the research protocol, or by implementing an institution-wide policy directive that allocates responsibilities between the institution and all ECs not operated by the institution. Such documentation must be part of the EC’s records. The G-HHS-Inst-Engagemt can help an institution to determine if a research study can be classified as non-exempt.

Ethics Committee Composition

As stated in 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule , an EC must be composed of at least five (5) members with varying backgrounds to promote complete and adequate research proposal review. The EC must be sufficiently qualified through member experience, expertise, and diversity, in terms of race, gender, cultural backgrounds, and sensitivity to issues such as community attitudes, to promote respect for its advice and counsel in safeguarding human participants’ rights and welfare. EC members must possess the professional competence to review research activities and be able to ascertain the acceptability of proposed research based on institutional commitments and regulations, applicable laws, and standards. In addition, if an EC regularly reviews research involving vulnerable populations, the committee must consider including one (1) or more individuals knowledgeable about and experienced in working with those participants. See the Vulnerable Populations section for details on vulnerable populations.

At a minimum, each EC must also include the following members:

- One (1) primarily focused on scientific issues

- One (1) focused on nonscientific issues

- One (1) unaffiliated with the institution, and not part of the immediate family of a person affiliated with the institution

No EC member may participate in the initial or continuing review of any project in which the member has a conflicting interest, except to provide EC requested information.

Terms of Reference, Review Procedures, and Meeting Schedule

As delineated in 21CFR56 , ECs must follow written procedures for the following:

- Conducting initial and continuing reviews, and reporting findings and actions

- Determining which projects require review more often than annually, and which projects need verification from sources other than the investigator that no material changes have occurred since the previous EC review

- Ensuring that changes in approved research are not initiated without EC review and approval except where necessary to eliminate apparent immediate hazards to participants

- Ensuring prompt reporting to the EC, institution, and FDA of changes in research activity; unanticipated problems involving risks to participants or others; any instance of serious or continuing noncompliance with these regulations or EC requirements or determinations; or EC approval suspension/termination

Per the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and the US-ICH-GCPs , ECs must establish and follow written procedures for the following:

- Conducting initial and continuing reviews, and reporting findings and actions to the investigator and the institution

- Ensuring prompt reporting to the EC of proposed changes in research and ensuring that investigators conduct the research in accordance with the terms of the EC approval until any proposed changes have received EC review and approval, except where necessary to eliminate apparent immediate hazards to participants

- Ensuring prompt reporting to the EC, the institution, the FDA, and the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) ’ Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) of any unanticipated problems involving risks to participants or others; any instance of serious or continuing noncompliance with these regulations or EC requirements or determinations; or EC approval suspension/termination.

21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule further require that an institution, or where appropriate an EC, prepare and maintain adequate documentation of EC activities, including copies of all research proposals reviewed. The applicable records must be retained for at least three (3) years after completion of the research. For more details on the EC records included in this requirement, see the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and 21CFR56 .

See G-IRBProcs for detailed FDA guidance on EC written procedures to enhance human participant protection and reduce regulatory burden. The guidance includes a Written Procedures Checklist that incorporates regulatory requirements as well as recommendations on operational details to support the requirements.

Per 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule , proposed research must be reviewed during convened meetings at which a majority of the EC members are present, including at least one (1) member whose primary concerns are nonscientific, except when an expedited review procedure is used. Research is only considered approved if it receives the majority approval of attending members.

Refer to the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , 21CFR56 , the G-IRBProcs , and the G-IRBFAQs for detailed EC procedural requirements.

In addition, per the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and the G-HHS-Inst-Engagemt , any institution engaged in non-exempt human subjects research conducted or supported by a Common Rule department/agency (as identified in USA-65 ) must also submit a written assurance of compliance to OHRP. According to USA-59 , the Federalwide Assurance (FWA) is the only type of assurance of compliance accepted and approved by OHRP for HHS-funded research. See USA-57 for more information on FWAs.

21CFR56 , 21CFR312 , the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and the US-ICH-GCPs state that the primary scope of information assessed by the institutional ethics committee (EC) (referred to as an institutional review board (IRB) in the United States (US)) relates to maintaining and protecting the dignity and rights of research participants and ensuring their safety throughout their participation in a clinical trial. As delineated in 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule , the EC must also pay special attention to reviewing informed consent and to protecting the welfare of certain classes of participants deemed to be vulnerable. (See the Vulnerable Populations; Children/Minors; Pregnant Women, Fetuses, & Neonates; Prisoners; and Mentally Impaired sections for additional information about these populations). The EC is also responsible for ensuring a competent review of the research protocol, evaluating the possible risks and expected benefits to participants, and verifying the adequacy of confidentiality safeguards.

See USA-65 for a list of Common Rule departments/agencies, and the Regulatory Authority section for more information on when the Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule apply to research.

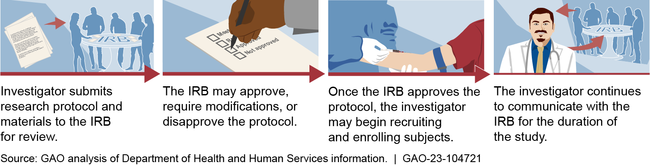

Role in Clinical Trial Approval Process

In accordance with 21CFR56 and 21CFR312 , the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) must review an investigational new drug application (IND) and an EC must review and approve the proposed study prior to a sponsor initiating a clinical trial. The institutional EC review of the clinical investigation may be conducted in parallel with the FDA review of the IND. However, EC approval must be obtained prior to the sponsor being permitted to initiate the clinical trial. According to 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule , the EC may approve, require modifications in (to secure approval), or disapprove the research.

Refer to the G-RevComRule-FDA for information on the impact of the RevComRule on studies conducted or supported by the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) that must also comply with FDA regulations.

Per 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and the G-IRBContRev , an EC has the authority to suspend or terminate approval of research that is not being conducted in accordance with the EC’s requirements or that has been associated with unexpected serious harm to participants. Any suspension or termination of approval will include a statement of the reasons for the EC’s action and will be reported promptly to the investigator, appropriate institutional officials, and the department or agency head (e.g., the FDA). See the G-IRBContRev for additional information and FDA recommendations on suspension or termination of EC approval.

Expedited Review

21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule indicate that the FDA and HHS maintain a list of research categories that may be reviewed by an EC through an expedited review procedure (see the G-IRBExpdtdRev for the list). An EC may use the expedited review procedure to review the following:

- Some or all of the research appearing on the list and found by the reviewer(s) to involve no more than minimal risk

- Minor changes in previously approved research during the period (of one (1) year or less) for which approval is authorized

- Under the RevComRule , research for which limited EC review is a condition of exemption

21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule specify that under an expedited review procedure, the review may be carried out by the EC chairperson or by one (1) or more experienced reviewers designated by the chairperson from among the EC’s members. In reviewing the research, the reviewers may exercise all of the authorities of the EC except that the reviewers may not disapprove the research. A research activity may be disapproved only after review in accordance with the EC’s non-expedited review procedure.

Continuing Review and Re-approval

21CFR56 and the G-IRBContRev state that any clinical investigation must not be initiated unless the reviewed and approved study remains subject to continuing review at intervals appropriate to the degree of risk, but not less than once a year. The G-IRBContRev notes that when continuing review of the research does not occur prior to the end of the approval period specified by the EC, EC approval expires automatically. A lapse in EC approval of research occurs whenever an investigator has failed to provide continuing review information to the EC, or the EC has not conducted continuing review and re-approved the research by the expiration date of the EC approval. In such circumstances, all research activities involving human participants must stop. Enrollment of new participants cannot occur after the expiration of EC approval.

In addition, per the G-IRBContRev , research that qualified for expedited review at the time of initial review will generally continue to qualify for expedited continuing review. For additional information and FDA recommendations regarding continuing review, see the G-IRBContRev .

The Pre2018-ComRule similarly indicates that the EC must conduct reviews at intervals appropriate to the degree of risk, but not less than once per year. However, the RevComRule provides the following exceptions to the continuing review requirement, unless an EC determines otherwise:

- Research eligible for expedited review

- Research reviewed by the EC in accordance with the limited EC review described in Section 46.104 of the RevComRule

- Research that has progressed to the point that it involves data analysis and/or accessing follow-up clinical data from procedures that are part of clinical care

Exemptions under the Revised Common Rule

Per the RevComRule , certain categories of research are exempt from EC review, and some “exempt” activities require limited EC review or broad consent. Users should refer to Section 46.104 of the RevComRule for detailed information on research categories specifically exempt from EC review, or exempt activities requiring limited EC review or broad consent.

Per USA-54 , for secondary research that does not qualify for an exemption under the RevComRule , the applicant must either apply for a waiver of the informed consent requirement from the EC, obtain study-specific informed consent, or obtain broad consent.

Further, the RevComRule modifies what constitutes research to specifically exclude the following types of research:

- Scholarly and journalistic activities

- Public health surveillance activities authorized by a public health authority to assess onsets of disease outbreaks or conditions of public health importance

- Collection and analysis of information, biospecimens, or records by or for a criminal justice agency for criminal investigative activities

- Authorized operational activities in support of intelligence, homeland security, defense, or other national security missions

See the G-IRBFAQs , the G-OHRP-IRBApprvl , and USA-54 for frequently asked questions regarding EC procedures, approval with conditions, example research, expedited review, limited review, and continuing review.

Per the FDA’s G-IRBReview , an EC may review studies that are not performed on-site. When an institution has a local EC, the written procedures of that EC or of the institution should define the scope of studies subject to review by that EC. A non-local EC may not become the EC of record for studies within that defined scope unless the local EC or the administration of the institution agree. Any agreement to allow review by a non-local EC should be in writing. For more information, see G-IRBReview .

Cooperative Research Studies

In the event of multicenter clinical studies, also known as cooperative research studies, taking place at US institutions that are subject to the RevComRule , the institutions must rely on a single EC to review that study for the portion of the study conducted in the US. The reviewing EC will be identified by the Common Rule department/agency (as identified in USA-65 ) supporting or conducting the research or proposed by the lead institution subject to the acceptance of the department/agency. The exceptions to this requirement include: when multicenter review is required by law (including tribal law) or for research where any federal department or agency supporting or conducting the research determines that the use of a single EC is not appropriate.

Designed to complement the RevComRule , per the NIHNotice16-094 and the NIHNotice17-076 , the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a final policy requiring all institute-funded multicenter clinical trials conducted in the US to be overseen by a single EC, unless prohibited by any federal, tribal, or state law, regulation, or policy.

For more information on multicenter research, see the FDA’s G-CoopRes . For more information on how new sites added to ongoing cooperative research can follow the same version of the Common Rule, see the HHS Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) ’s G-ComRuleCnsstncy .

Many institutional ethics committees (ECs) (referred to as institutional review boards (IRBs) in the United States (US)) charge fees to review research proposals submitted by industry-sponsored research or other for-profit entities. However, this varies widely by institution. Neither the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) nor the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) regulate institutional EC review fees. Because each EC has its own requirements, individual ECs should be contacted to confirm their specific fees.

As delineated in 21CFR56 and 45CFR46-B-E , the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) and the HHS’ Food & Drug Administration (FDA) have mandatory registration programs for institutional ethics committee (ECs), referred to as institutional review boards (IRBs) in the United States (US). A single electronic registration system ( USA-28 ) for both agencies is maintained by HHS’ Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) .

Registration, Auditing, and Accreditation

In accordance with the G-IRBReg-FAQs and USA-61 , EC registration with the HHS OHRP system ( USA-28 ) is not a form of accreditation or certification by either the FDA that the EC is in full compliance with 21CFR56 , or by the HHS that the EC is in full compliance with 45CFR46-B-E . Neither EC competence nor expertise is assessed during the registration review process by either agency.

According to 21CFR56 and the G-IRBReg-FAQs , the FDA requires each EC in the US, that either reviews clinical investigations regulated by the agency under the FDCAct or reviews investigations intended to support research or marketing permits for agency-regulated products, to register electronically in the HHS OHRP system ( USA-28 ). Only individuals authorized to act on the EC’s behalf are permitted to submit registration information. Non-US ECs may register voluntarily. The G-IRBReg-FAQs also indicates that while registration of non-US ECs is voluntary, the information the FDA receives from them is very helpful.

As stated in 21CFR56 and the G-IRBReg-FAQs , any EC not already registered in the HHS OHRP system ( USA-28 ) must submit an initial registration prior to reviewing a clinical investigation in support of an investigational new drug application (IND). The HHS OHRP system ( USA-28 ) provides instructions to assist users, depending on whether the EC is subject to regulation by only the OHRP, only the FDA, or both the OHRP and the FDA.

21CFR56 and the G-IRBReg-FAQs indicate that FDA EC registration must be renewed every three (3) years. EC registration becomes effective after review and acceptance by the HHS.

See 21CFR56 and the G-IRBReg-FAQs for detailed EC registration submission requirements. See the G-IRBInspect for FDA inspection procedures of ECs.

Per the Pre2018-ComRule and RevComRule , institutions engaging in research conducted or supported by a Common Rule department/agency (as identified in USA-65 ) must obtain an approved assurance that it will comply with the Pre2018-ComRule or RevComRule requirements and certify to the department/agency heads that the research has been reviewed and approved by an EC provided for in the assurance.

Per USA-59 , a Federalwide Assurance (FWA) of compliance is a document submitted by an institution (not an EC) engaged in non-exempt human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS that commits the institution to complying with Pre2018-ComRule or RevComRule requirements. FWAs also are approved by the OHRP for federalwide use, which means that other federal departments and agencies that have adopted the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects ( Pre2018-ComRule or RevComRule ) may rely on the FWA for the research that they conduct or support. Institutions engaging in research conducted or supported by non-HHS federal departments or agencies should consult with the sponsoring department or agency for guidance regarding whether the FWA is appropriate for the research in question.

Per USA-54 , institutions do not need to change an existing FWA because of the RevComRule . See USA-57 for more information on FWAs.

Per 45CFR46-B-E and USA-61 , all ECs that review human subjects research conducted or supported by HHS and are to be designated under an OHRP FWA must register electronically with the HHS OHRP system ( USA-28 ). An individual authorized to act on behalf of the institution operating the EC must submit the registration information. EC registration becomes effective for three (3) years when reviewed and approved by OHRP.

Per USA-59 , an institution must either register its own EC (an “internal” EC) or designate an already registered EC operated by another organization (“external” EC) after establishing a written agreement with that other organization. Additionally, each FWA must designate at least one (1) EC registered with the OHRP. The FWA is the only type of assurance of compliance accepted and approved by the OHRP.

See 45CFR46-B-E , USA-58 , and USA-61 for detailed registration requirements and instructions.

As delineated in 21CFR312 , USA-42 , and USA-52 , the United States (US) requires the sponsor to submit an investigational new drug application (IND) for the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) 's review and authorization to obtain an exemption to ship investigational drug or biological products across state lines and to administer these investigational products in humans. Per 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Determination , whether an IND is required to conduct an investigation of a drug to be marketed (this includes biological products under the FDCAct ) primarily depends on the intent of the investigation, and the degree of risk associated with the use of the drug in the investigation. See the Scope of Assessment section for more information.

In addition, per 21CFR56 and 21CFR312 , institutional ethics committee (EC) (institutional review board (IRB) in the US) review of the clinical investigation may be conducted in parallel with the FDA review of the IND. However, EC approval must be obtained prior to the sponsor being permitted to initiate the clinical trial.

Regulatory Submission

According to 21CFR312 , meetings between a sponsor and the FDA may be useful in resolving questions and issues raised during the course of a clinical investigation. The FDA encourages such meetings to the extent that they aid in the evaluation of the drug and in the solution of scientific problems concerning the drug, to the degree the FDA's resources permit. See 21CFR312 for more information on meetings with the FDA.

A sponsor who is conducting a clinical trial to support a future marketing application may ask to meet with the FDA for a special protocol assessment (SPA) to help ensure the clinical trial can support the application. For more information, see G-SPA .

Additionally, the G-FDAComm describes the FDA’s philosophy regarding timely interactive communication with IND sponsors, the scope of appropriate interactions between review teams and sponsors, the types of advice appropriate for sponsors to seek from the FDA in pursuing their drug development programs, and general expectations for the timing of FDA response to sponsor inquiries. See the G-FDAComm for more information.

According to the G-PharmeCTD , which implements FDCAct requirements, and as described in USA-34 and USA-53 , commercial IND submissions must be submitted in the Electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) format. Noncommercial INDs are exempt from this eCTD format submission requirement. “Noncommercial products” refer to products not intended to be distributed commercially, including investigator-sponsored INDs and expanded access INDs (e.g., emergency use and treatment INDs). However, the G-AltrntElecSubs indicates that sponsors and applicants who receive an exemption or a waiver from filing in eCTD format should still provide those exempted or waived submissions electronically, in an alternate format.

The G-AltrntElecSubs and USA-35 indicate that for both eCTD and alternate electronic formats, submissions should include only FDA fillable forms and electronic signatures. Scanned images of FDA fillable forms should not be submitted. In addition, before making an electronic submission, a pre-assigned application number should be obtained by contacting the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) or Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) . See USA-35 for more information on requesting an application number.

For more information and detailed requirements on eCTD submissions, see the G-PharmeCTD , the G-eCTDTech , USA-35 , and USA-36 . Additionally, the G-CBER-ElecINDs provides instructions on how to submit an IND using an electronic folder structure on a CD-ROM.

According to the G-eCTDspecs and USA-7 , eCTD submissions sized 10 GB and under for most applications must be submitted via the FDA Electronic Submissions Gateway (ESG) ( USA-44 ). However, the G-eCTDspecs adds that the FDA also recommends the use of USA-44 for submissions greater than 10 GB when possible. See USA-8 for information on how to create an account.

As indicated in the G-eCTDspecs , physical media greater than 10 GB should be submitted using a USB drive. For specific instructions on how to submit physical media, email CDER at [email protected] or CBER at [email protected] . See the G-eCTDspecs for additional physical media information.

The IND must be submitted in English. As indicated in 21CFR312 , the sponsor must submit an accurate and complete English translation of each part of the IND that is not in English. The sponsor must also submit a copy of each original literature publication for which an English translation is submitted.

According to USA-41 and USA-94 , paper submissions of INDs should be sent to CDER or CBER at the following locations, as appropriate:

Drugs (submitted by Sponsor-Investigators):

Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Central Document Room 5901-B Ammendale Rd. Beltsville, MD 20705-1266

Therapeutic Biological Product (submitted by Sponsor-Investigators) :

Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Therapeutic Biological Products Document Room 5901-B Ammendale Rd. Beltsville, MD 20705-1266

Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research-Regulated Products:

Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) Document Control Center 10903 New Hampshire Avenue WO71, G112 Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002

(Note: Per USA-94 , CBER also accepts electronic media via mail, but electronic or email submission is preferred.)

Based on information provided in 21CFR312 , for paper IND submissions, the sponsor must submit an original and two (2) copies, including the original submission and all amendments and reports.

Ethics Review Submission

Each EC maintains its own procedures and processes for review. Consequently, there is no stated regulatory requirement for clinical trial submission processes.

Regulatory Authority Requirements

As specified in 21CFR312 , an investigational new drug application (IND) to the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) must include the following documents, in the order provided below:

- Cover sheet (Form FDA 1571 ( USA-76 )) (including, but not limited to: sponsor contact information, investigational product (IP) name, application date, phase(s) of clinical investigation to be conducted, and commitment that the institutional ethics committee (EC) (institutional review board (IRB) in the United States (US)) will conduct initial and continuing review and approval of each study proposed in the investigation)

- Table of contents

- Introductory statement and general investigational plan

- Investigator’s brochure (IB)

- Chemistry, manufacturing, and control data

- Pharmacology and toxicology data

- Previous human experience with the IP

- Additional information (e.g., drug dependence and abuse potential, radioactive drugs, pediatric studies)

- Relevant information (e.g., foreign language materials and number of copies - see Submission Process section for details)

For detailed application requirements, see 21CFR312 . In addition, see USA-40 for other IND forms and instructions.

Furthermore, for information on the appropriate use of adaptive designs for clinical trials and additional information to provide to the FDA to support its review, see G-AdaptiveTrials .

The G-RWDRWE-Doc states that to facilitate the FDA’s internal tracking of submissions that include real-world data (RWD) and real-world evidence (RWE), sponsors and applicants are encouraged to identify in their submission cover letters certain uses of RWD/RWE. For more information, see the G-RWDRWE-Doc .

The FDCAct , as amended by the FDORA , requires sponsors to submit diversity action plans for certain clinical trials, such as a clinical investigation of a new drug that is a phase 3 study. See the FDORA for more details. (Note: The FDA’s guidance on diversity action plans is currently in draft. The ClinRegs team will continue to monitor this requirement and incorporate any updates as appropriate).

According to the G-PedStudyPlans , a sponsor who is planning to submit to the FDA a marketing application (or supplement to an application) for a new active ingredient, new indication, new dosage form, new dosing regimen, or new route of administration is required to submit an initial pediatric study plan (iPSP), if required by the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA) . An exception to this is if the drug is for an indication granted an orphan designation. For additional details and recommendations to sponsors regarding the submission of an iPSP, see the G-PedStudyPlans .

Ethics Committee Requirements

Each EC has its own application form and clearance requirements, which can differ significantly regarding application content requirements. However, the requirements listed below comply with 21CFR56 as well as the US-ICH-GCPs and are basically consistent across all US ECs.

As per 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and the US-ICH-GCPs , the EC should obtain the following documents and must ensure the listed requirements are met prior to approving the study (Note: The regulations provide overlapping and unique elements so each of the items listed below will not necessarily be in each source):

- Clinical protocol

- Informed consent forms (ICFs) and participant information (the RevComRule also requires information regarding whether informed consent was appropriately sought and documented, or waived)

- Participant recruitment procedures

- Safety information

- Participant payments and compensation

- Investigator(s) current Curriculum Vitaes (CVs)

- Additional required EC documentation

- Risks to participants are minimized and are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits

- Participant selection is equitable

- Adequate provisions are made to protect participant privacy and maintain confidentiality of data, where appropriate; the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) will issue guidance to assist ECs in assessing what provisions are adequate to protect participant privacy and maintain the confidentiality of data

Per the RevComRule , where limited EC review applies, the EC does not need to make the determinations outlined above. Rather, limited EC review includes determinations that broad consent will be/was obtained properly, that adequate protections are in place for safeguarding the privacy and confidentiality of participants, and (for secondary studies) that individual research results will not be returned to participants. See USA-65 for a list of Common Rule departments/agencies, and the Regulatory Authority section for more information on when the Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule apply to research.

See 21CFR56 , the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and section 3 of the US-ICH-GCPs for additional EC submission requirements.

Clinical Protocol

According to the US-ICH-GCPs , the clinical protocol should contain the following elements:

- General information

- Background information

- Trial objectives and purpose

- Trial design

- Participant selection/withdrawal

- Participant treatment

- Efficacy assessment

- Safety assessment

- Direct access to source data/documents

- Quality control/quality assurance

- Data handling/recordkeeping

- Financing/insurance

- Publication policy

- For complete protocol requirements, see section 6 of the US-ICH-GCPs .

Per the NIHNotice17-064 , and provided in USA-29 and USA-27 , the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the FDA developed a clinical trial protocol template with instructional and example text for NIH-funded investigators to use when writing protocols for phase 2 and 3 clinical trials that require IND applications.

As delineated in 21CFR56 and 21CFR312 , institutional ethics committee (EC) (institutional review board (IRB) in the United States (US)) review of the clinical investigation may be conducted in parallel with the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) 's review of the investigational new drug application (IND). However, EC approval must be obtained prior to the sponsor being permitted to initiate the clinical trial.

Regulatory Authority Approval

Per the FDCAct and 21CFR312 , initial INDs submitted to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) or Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) automatically go into effect in 30 calendar days, unless the FDA notifies the sponsor that the IND is subject to a clinical hold, or the FDA has notified the sponsor earlier that the trial may begin. As indicated in 21CFR312 , the FDA will provide the sponsor with a written explanation of the basis for the hold as soon as possible, and no more than 30 days after the imposition of the clinical hold. See 21CFR312 for more information on clinical hold timelines. For more information on CDER and CBER internal policies and procedures for reviewing applications, see USA-96 and USA-95 , respectively.

According to USA-41 and USA-42 , clinical studies must not be initiated until 30 days after the FDA receives the IND, unless the FDA provides earlier notification that studies may begin.

Ethics Committee Approval

Each EC maintains its own procedures and processes for review. Consequently, there is no stated regulatory requirement for a standard timeline of review and approval of the clinical trial. However, according to the US-ICH-GCPs , the institutional EC should review a proposed clinical trial within a reasonable time.

In accordance with 21CFR312 , USA-41 , and USA-42 , a clinical trial can only commence after the investigational new drug application (IND) is reviewed by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) , which will provide a written determination within 30 days of receiving the IND. No waiting period is required following the 30-day FDA review period, unless the agency imposes a clinical hold on the IND or sends an earlier notification that studies may begin. Per 21CFR312 and 21CFR56 , ethics approval from an institutional ethics committee (EC) (known as institutional review board (IRB) in the United States (US)) is also required before a clinical trial can commence.

As per 21CFR312 , once an IND has been submitted and following the 30-day review period, the sponsor is permitted to import an investigational product (IP). (See the Manufacturing & Import section for additional information).

See the G-CTDiversity for FDA recommendations to sponsors on increasing enrollment of underrepresented populations in their clinical trials.

Clinical Trial Agreement

Prior to the trial’s commencement, as addressed in the 21CFR312 and the G-1572FAQs , the sponsor must obtain from the investigator(s) a signed Statement of Investigator, Form FDA 1572 ( USA-77 ). This form serves as the investigator’s agreement to provide certain information to the sponsor and to ensure compliance with the FDA’s clinical investigation regulations. Refer to the 21CFR312 , the G-1572FAQs , and USA-40 for further information.

The US-ICH-GCPs indicates that the sponsor must obtain the investigator’s/institution’s agreement:

- To conduct the trial in compliance with good clinical practice (GCP), with the applicable regulatory requirement(s), and with the protocol agreed to by the sponsor and given approval/favorable opinion by the EC;

- To comply with procedures for data recording/reporting;

- To permit monitoring, auditing, and inspection; and

- To retain the trial-related essential documents until the sponsor informs the investigator/institution these documents are no longer needed.

The sponsor and the investigator/institution must sign the protocol, or an alternative document, to confirm this agreement.

Clinical Trial Registration

The FDAMA , the FDAAA , and 42CFR11 require the responsible party, either the sponsor or the principal investigator (PI) designated by the sponsor, to register electronically with the ClinicalTrials.gov databank ( USA-78 ). Per the FDAAA and 42CFR11 , the sponsor/PI must register no later than 21 calendar days after the first human participant is enrolled in a trial.

42CFR11 expands the legal requirements for submitting clinical trial registration information and results for investigational products that are approved, licensed, or cleared by the FDA.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued NIHTrialInfo to complement 42CFR11 requirements. This policy requires all NIH-funded awardees and investigators conducting clinical trials, funded in whole or in part by the NIH, regardless of study phase, type of intervention, or whether they are subject to the regulation, to ensure that they register and submit trial results to ClinicalTrials.gov ( USA-78 ).

See 42CFR11 , the NIHTrialInfo , and USA-49 for detailed information on ClinicalTrials.gov ( USA-78 ). See also the FDA’s G-DataBankPnlty for clarification on the types of civil money penalties that may be issued for failing to register a clinical trial.

Safety Reporting Definitions

In accordance with 21CFR312 , the G-IND-Safety , 42CFR11 , and USA-38 , the following definitions provide a basis for a common understanding of safety reporting requirements in the United States (US):

- Adverse Event – Any untoward medical occurrence associated with the use of a drug in humans, whether or not considered drug related

- Suspected Adverse Reaction – Any adverse event where there is a reasonable possibility that the drug caused the adverse event

- Adverse Reaction – Any adverse event caused by a drug. Adverse reactions are a subset of all suspected adverse reactions where there is reason to conclude that the drug caused the event

- Serious Adverse Event/Serious Suspected Adverse Reaction – An adverse event/suspected adverse reaction that results in death, is life-threatening, requires inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, causes persistent or significant disability/incapacity, results in a congenital anomaly/birth defect, or leads to a substantial disruption of the participant’s ability to conduct normal life functions

- Unexpected Adverse Event/Unexpected Suspected Adverse Reaction – An adverse event/suspected adverse reaction that is not listed in the investigator’s brochure (IB), or is not listed at the specificity or severity that has been observed; or if an IB is not required or available, is not consistent with the risk information described in the general investigational plan or elsewhere in the application

- Life-threatening Adverse Event/Life-threatening Suspected Adverse Reaction – An adverse event/suspected adverse reaction is considered “life-threatening” if its occurrence places the participant at immediate risk of death. It does not include an adverse event/suspected adverse reaction that, had it occurred in a more severe form, might have caused death

According to the G-HHS-AEReqs , the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) ’s 45CFR46 regulations (the Pre2018-ComRule , the RevComRule , and 45CFR46-B-E ) do not define the terms “adverse event” or “unanticipated problems.” However, the Pre2018-ComRule and the RevComRule do contain requirements relevant to reviewing and reporting these incidents. See the G-HHS-AEReqs , the G-IRBRpting , the Pre2018-ComRule , and the RevComRule for further information.

Safety Reporting Requirements

Investigator Responsibilities

As delineated in 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Safety , the investigator must comply with the following reporting requirements:

- Serious adverse events, whether or not considered drug related, must be reported immediately to the sponsor

- Study endpoints that are serious adverse events must be reported in accordance with the protocol unless there is evidence suggesting a causal relationship between the drug and the event. In that case, the investigator must immediately report the event to the sponsor

- Non-serious adverse events must be recorded and reported to the sponsor according to the protocol specified timetable

- Report promptly to the ethics committee (EC) all unanticipated problems involving risk to human participants or others where adverse events should be considered unanticipated problems

Sponsor Responsibilities

As delineated in 21CFR312 , the G-IND-Safety , and USA-38 , the sponsor must report any suspected adverse reaction or adverse reaction that is both serious and unexpected. An adverse event is only required to be reported as a suspected adverse reaction if there is evidence to suggest a causal relationship between the drug and the adverse event .

The sponsor is required to notify the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and all participating investigators in a written safety report of potential serious risks, from clinical trials or any other source, as soon as possible, but no later than 15 calendar days after the sponsor determines the information qualifies for reporting. Additionally, the sponsor must notify the FDA of any unexpected fatal or life-threatening suspected adverse reaction as soon as possible, but no later than seven (7) calendar days following receipt of the information. The sponsor is required to submit a follow-up safety report to provide additional information obtained pertaining to a previously submitted safety report. This report should be submitted without delay, as soon as the information is available, but no later than 15 calendar days after the sponsor initially receives the information.

Per 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Safety , the sponsor must also report the following:

- Any findings from epidemiological studies, pooled analyses of multiple studies, or clinical studies (other than those reported in the safety report), whether or not conducted under an investigational new drug application (IND), and whether or not conducted by the sponsor, that suggest a significant risk in humans exposed to the drug

- Any findings from animal or in vitro testing, whether or not conducted by the sponsor, that suggest a significant risk in humans exposed to the drug

- Any clinically important increase in the rate of a serious suspected adverse reaction over that listed in the protocol or IB

In each safety report, the sponsor must identify all safety reports previously submitted to the FDA concerning a similar suspected adverse reaction and must analyze the significance of the suspected adverse reaction in light of previous, similar reports, or any other relevant information. Refer to 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Safety for more details on these safety reporting requirements.

As part of the clinical trial results information submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov ( USA-78 ), 42CFR11 requires the responsible party, either the sponsor or the principal investigator (PI) designated by the sponsor, to submit three (3) tables of adverse event information. The tables should consist of the following summarized data:

- All serious adverse events

- All adverse events, other than serious adverse events, that exceed a frequency of five (5) percent in any arm of the trial

- All-cause mortalities

Per 42CFR11 and USA-70 , this information must be submitted no later than one (1) year after the primary completion date of the clinical trial. Submission of trial results may be delayed as long as two (2) years if the sponsor or PI submits a certification to ClinicalTrials.gov ( USA-78 ) that either: 1) the FDA has not yet approved, licensed, or cleared for marketing the investigational product (IP) being studied; or 2) the manufacturer is the sponsor and has sought or will seek approval within one (1) year.

See 42CFR11 for detailed adverse event reporting requirements.

Form Completion & Delivery Requirements

As per 21CFR312 , the G-IND-Safety , and USA-38 , the sponsor must submit each safety report in a narrative format on Form FDA 3500A ( USA-75 ), or in an electronic format that the FDA can process, review, and archive, and be accompanied by Form FDA 1571 ( USA-76 ) (cover sheet).

As per the G-IND-Safety and USA-38 , the submission must be identified as follows:

- “IND safety report” for 15-day reports

- “7-day IND safety report” for unexpected fatal or life-threatening suspected adverse reaction reports

- “Follow-up IND safety report” for follow-up information

The report must be submitted to the appropriate review division (i.e., Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) or Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) ). Per USA-38 , the FDA recommends that sponsors submit safety reports electronically. Other means of rapid communication to the respective review division’s Regulatory Project Manager (e.g., telephone, facsimile transmission, email) may also be used. Per USA-90 , fatality reports to CBER should be sent to [email protected] .

Additionally, 21CFR312 and the G-IND-Safety indicate that the FDA will accept foreign suspected adverse reaction reports on CIOMS Form I (See USA-13 and USA-3 ) instead of Form FDA 3500A ( USA-75 ). See USA-38 and USA-48 for additional information.

Interim and Annual Progress Reports

As per the US-ICH-GCPs , the investigator should promptly provide written reports to the sponsor and the institutional ethics committee (EC) (institutional review board (IRB) in the United States (US)) on any changes significantly affecting the conduct of the trial, and/or increasing the risk to participants.

As specified in 21CFR312 , the investigator must furnish all reports to the sponsor who is responsible for collecting and evaluating the results obtained. In addition, per 21CFR56 and the US-ICH-GCPs the investigator should submit written summaries of the trial status to the institutional EC annually, or more frequently, if requested by the institutional EC.

21CFR312 states that the sponsor must submit a brief annual progress report on the investigation to the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) within 60 days of the anniversary date that the investigational new drug went into effect. The report must contain the following information for each study:

- Title, purpose, and description of patient population, and current status

- Summary of the participants screened (e.g., failed screenings; participants enrolled, withdrawn, or lost to follow-up; and other challenges)

- Summary information - including information obtained during the previous year’s clinical and nonclinical investigations

- Description of the general investigational plan for the coming year

- Updated investigator’s brochure, if revised

- Description of any significant Phase 1 protocol modifications not previously reported in a protocol amendment

- Brief summary of significant foreign marketing developments with the drug

- A log of any outstanding business for which the sponsor requests a reply, comment, or meeting

As indicated in 42CFR11 , trial updates must be submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov ( USA-78 ) according to the following guidelines:

- Not less than once every 12 months for updated general trial registration information

- Not later than 30 calendar days for any changes in overall recruitment status

- Not later than 30 calendar days after the trial reaches its actual primary completion date, the date the final participant was examined or received an intervention for the purposes of final collection data for the primary outcome

Final Report

As indicated in 21CFR312 , an investigator must provide the sponsor with an adequate report shortly after completion of the investigator’s participation in the investigation. There is no specific timeframe stipulated for when the report should be completed.

The US-ICH-GCPs also states that upon the trial’s completion, the investigator should inform the institution and the investigator/institution should provide the EC with a summary of the trial’s outcome, and supply the FDA with any additional report(s) required of the investigator/institution.

Additionally, per 42CFR11 and USA-70 , the sponsor or the principal investigator (PI) designated by the sponsor must submit results for applicable investigational product (IP) clinical trials to USA-78 no later than one (1) year following the study’s completion date. Submission of trial results may be delayed as long as two (2) years if the sponsor or PI submits a certification to USA-78 that indicates either: 1) the FDA has not yet approved, licensed, or cleared the IP being studied for marketing; or 2) the manufacturer is the sponsor and has sought or will seek approval within one (1) year. The results information must include data on the following:

- Participant flow

- Demographic and baseline characteristics

- Outcomes and statistical analysis

- Adverse events

- The protocol and statistical analysis plan

- Administrative information

See USA-49 for more information and 42CFR11 for more detailed requirements. See NIHTrialInfo for specific information on dissemination of NIH-funded clinical trial data.

As per 21CFR312 , 21CFR50 , and the US-ICH-GCPs , a sponsor is defined as a person who takes responsibility for and initiates a clinical investigation. The sponsor may be an individual or pharmaceutical company, governmental agency, academic institution, private organization, or other organization. The sponsor does not actually conduct the investigation unless the sponsor is a sponsor-investigator. 21CFR312 , 21CFR50 , and the US-ICH-GCPs define a sponsor-investigator as an individual who both initiates and conducts an investigation, and under whose immediate direction the investigational product is administered or dispensed.

In addition, 21CFR312 and the US-ICH-GCPs state that a sponsor may transfer responsibility for any or all obligations to a contract research organization (CRO).