- Submit your COVID-19 Pandemic Research

- Research Leap Manual on Academic Writing

- Conduct Your Survey Easily

- Research Tools for Primary and Secondary Research

- Useful and Reliable Article Sources for Researchers

- Tips on writing a Research Paper

- Stuck on Your Thesis Statement?

- Out of the Box

- How to Organize the Format of Your Writing

- Argumentative Versus Persuasive. Comparing the 2 Types of Academic Writing Styles

- Very Quick Academic Writing Tips and Advices

- Top 4 Quick Useful Tips for Your Introduction

- Have You Chosen the Right Topic for Your Research Paper?

- Follow These Easy 8 Steps to Write an Effective Paper

- 7 Errors in your thesis statement

- How do I even Write an Academic Paper?

- Useful Tips for Successful Academic Writing

Digital Technologies Supporting SMEs – A Survey in Albanian Manufacturers’ Websites

A taxonomy of knowledge management systems in the micro-enterprise, immigrant entrepreneurship in europe: insights from a bibliometric analysis.

- Enhancing Employee Job Performance Through Supportive Leadership, Diversity Management, and Employee Commitment: The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

- Relationship Management in Sales – Presentation of a Model with Which Sales Employees Can Build Interpersonal Relationships with Customers

- Promoting Digital Technologies to Enhance Human Resource Progress in Banking

- Enhancing Customer Loyalty in the E-Food Industry: Examining Customer Perspectives on Lock-In Strategies

- Self-Disruption As A Strategy For Leveraging A Bank’s Sustainability During Disruptive Periods: A Perspective from the Caribbean Financial Institutions

- Slide Share

Developing effective research collaborations: Strategies for building successful partnerships

Research collaborations have become increasingly popular in recent years, with more and more researchers recognizing the benefits of working together to achieve common research goals. Collaborative research offers a range of advantages, including increased funding opportunities, access to specialized expertise, and the potential for greater impact and reach of research outcomes. However, building successful partnerships requires careful planning and execution, as well as a willingness to overcome the challenges that can arise when working with others. In this article, we will explore the strategies for developing effective research collaborations and building successful partnerships.

Identify shared research interests and goals:

The first step in building a successful research collaboration is to identify shared research interests and goals. This requires careful consideration of the research areas that are of interest to all parties involved, as well as an understanding of the specific research questions that each party seeks to answer. This may involve conducting a thorough literature review to identify knowledge gaps or areas where additional research is needed. Once shared research interests and goals have been identified, a clear research plan can be developed that outlines the objectives, research methods, and expected outcomes of the collaboration.

Establish clear roles and responsibilities:

In order to avoid confusion and ensure that everyone involved in the research collaboration is working towards the same objectives, it is important to establish clear roles and responsibilities from the outset. This means clearly defining the tasks and responsibilities of each member of the research team, as well as outlining the timelines and milestones for the project. This can help to avoid duplication of effort, reduce the risk of misunderstandings, and ensure that everyone is aware of their contribution to the collaboration.

Foster open communication and collaboration:

Effective research collaborations require open communication and collaboration between all parties involved. This means creating a supportive and inclusive research environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their ideas and perspectives, and where constructive feedback is encouraged. Regular meetings and check-ins can help to ensure that everyone is on track, and that any issues or concerns are addressed in a timely manner. Collaborative research platforms, such as shared online spaces or project management software, can also help to facilitate communication and collaboration among team members.

Build trust and mutual respect:

Building trust and mutual respect is essential for developing effective research collaborations. This means creating a culture of transparency and honesty, where everyone feels comfortable sharing their thoughts and concerns without fear of judgment or reprisal. It also means respecting the expertise and opinions of other team members, and being willing to compromise and find common ground when differences arise. By building trust and mutual respect, research collaborations can create a strong foundation for success and ensure that all members feel valued and supported.

Manage conflicts and challenges:

Despite the best planning and execution, conflicts and challenges can arise when working on collaborative research projects. These may include differences in research approaches or methodologies, competing priorities or interests, or misunderstandings about roles or responsibilities. Effective conflict management is essential for maintaining the momentum of the collaboration and ensuring that everyone remains focused on achieving the shared research goals. This may involve implementing clear conflict resolution protocols, establishing open lines of communication for addressing concerns, or seeking external mediation when necessary.

Research collaborations offer a range of benefits, from increased funding opportunities to access to specialized expertise and resources. However, building successful partnerships requires careful planning and execution, as well as a willingness to overcome the challenges that can arise when working with others. By following the strategies outlined in this article, researchers can develop effective research collaborations that are based on shared research interests and goals, clear roles and responsibilities, open communication and collaboration, trust and mutual respect, and effective conflict management. By doing so, they can increase the impact and reach of their research outcomes, and make meaningful contributions to their respective fields.

Suggested Articles

Creation Process of the Successful Research Project. Follow these Steps while doing a research in…

The Role of Primary and Secondary Research Tools in Your Survey Try a New Method…

If you are embarking on a research project, the first step is to develop a…

How to organize your research paper effectively Wondering about organizing your paper wisely? And here…

Related Posts

Comments are closed.

10 Key Steps to Secure Effective Academic Research Collaboration

Oct 6, 2023 | Research FAQs

How Can I Effectively Collaborate with Other Researchers on a Project?

Research collaboration is a fundamental aspect of academia that has gained increasing prominence in recent years. It refers to the practice of multiple researchers working together on a common project, sharing their expertise, resources, and ideas to achieve a common goal. In today’s complex academic landscape, research collaboration has become indispensable, as it allows scholars to tackle complex problems, pool resources, and produce innovative solutions. In this article, we will explore the strategies, benefits, challenges, and key tips for effective research collaboration. Whether you are a student embarking on your first collaborative project or an experienced researcher seeking to enhance your collaboration skills, this guide will provide you with valuable insights and actionable advice.

10 Key Steps to Secure Effective Collaboration

#1 establish clear objectives and roles.

Successful research collaboration begins with a clear understanding of project objectives and the roles of each team member. Define the scope, goals, and expected outcomes of the project from the outset. For example, in a study on renewable energy sources, one researcher may focus on solar energy technology, while another specialises in wind energy. By delineating roles, you ensure that each team member contributes their unique expertise effectively.

The foundation of a successful research collaboration lies in the establishment of clear objectives and the definition of each team member’s roles. These objectives serve as guiding lights throughout the project, ensuring that everyone involved is on the same page. When embarking on a project, it’s essential to delineate the scope, goals, and expected outcomes right from the outset. For example, in a study centred around renewable energy sources, you might have one team member focusing on solar energy technology, while another specialises in wind energy. This clear division of responsibilities ensures that each team member can leverage their unique expertise effectively.

Example: The Human Genome Project, a monumental collaboration involving multiple research institutions, had a clear objective: to map and understand all the genes of the human genome. Different teams were responsible for various aspects of this ambitious project, from sequencing to data analysis.

#2 Select Complementary Team Members

Collaborative success often hinges on assembling a team with complementary skills, knowledge, and backgrounds. Seek individuals who bring diverse perspectives and expertise to the table. Collaborators should enhance, rather than duplicate, each other’s strengths.

The composition of your collaborative team plays a critical role in its success. Collaborative efforts thrive when the team members possess complementary skills, knowledge, and backgrounds. It’s not just about gathering a group of experts; it’s about finding individuals whose strengths bolster one another. Seek out collaborators who bring diverse perspectives to the table. Instead of duplicating skills, they should enhance each other’s strengths, resulting in a more robust and well-rounded research team.

Example: In a study examining the impact of climate change on coastal ecosystems, researchers with backgrounds in marine biology, environmental science, and climate modelling might collaborate to provide a comprehensive analysis.

#3 Establish Effective Communication Channels

Communication is the lifeblood of research collaboration. Choose efficient communication tools and platforms that facilitate seamless information sharing, such as project management software, video conferencing, and cloud-based document sharing. Regular meetings and updates are essential to keep the team aligned.

In the digital age, effective communication is the lifeblood of research collaboration. To ensure seamless information sharing, it’s imperative to choose communication tools and platforms that are both efficient and convenient. Project management software, video conferencing, and cloud-based document sharing are just a few examples. Regular meetings and updates are also crucial to keep the team aligned and informed about progress, challenges, and adjustments in the research process.

Example: Researchers from different time zones can use virtual collaboration tools like Slack or Microsoft Teams to ensure real-time communication and document sharing.

#4 Develop a Research Collaboration Agreement

A research collaboration agreement is a formal document that outlines the terms, responsibilities, and expectations of all collaborators. It helps prevent misunderstandings and conflicts by clearly defining issues like authorship, data ownership, and intellectual property rights.

A research collaboration agreement is more than a formality; it’s a safeguard for your project. This formal document outlines the terms, responsibilities, and expectations of all collaborators, preventing misunderstandings and conflicts down the line.

Key issues, such as authorship, data ownership, and intellectual property rights, should be clearly defined. This agreement provides a solid foundation on which the collaboration can thrive.

Example: In a collaboration between a university and a pharmaceutical company to develop a new drug, the research collaboration agreement would specify how any resulting patents and royalties would be shared.

#5 Leverage Technology for Data Sharing

With the increasing volume of data in research, effective data sharing is crucial. Employ secure and standardised methods for data storage, access, and sharing to ensure data integrity and accessibility among collaborators .

With the exponential growth of data in research, effective data sharing is paramount. Collaborators should employ secure and standardised methods for data storage, access, and sharing. This not only ensures data integrity but also facilitates accessibility among team members. The right technology can make data management more efficient, allowing the team to focus on analysis and interpretation.

Example: Large-scale particle physics experiments, like those at CERN, rely on advanced data-sharing infrastructure to process and analyse vast amounts of data from experiments conducted by researchers worldwide.

#6 Foster a Collaborative Culture

Building a collaborative culture within your research team is vital. Encourage open dialogue, value diverse perspectives, and promote a culture of trust and respect. A positive collaborative environment enhances creativity and problem-solving.

Beyond logistics, building a collaborative culture within your research team is vital. Encouraging open dialogue, valuing diverse perspectives, and promoting a culture of trust and respect can transform your research environment. Such an atmosphere encourages creativity and problem-solving, as team members feel safe sharing ideas and taking calculated risks.

Example: The Linux operating system is a product of global collaboration, with thousands of developers contributing their expertise voluntarily, driven by a shared passion for open-source software.

#7 Manage Conflicts Effectively

Conflicts can arise in any collaborative situation. Address them promptly and constructively. Encourage team members to express concerns and work together to find solutions. A conflict resolution plan can help mitigate disputes.

No matter how well-organised a research collaboration is, conflicts can still arise. The key is to address them promptly and constructively. Encouraging team members to express concerns and work together to find solutions can turn conflicts into opportunities for growth. Having a pre-established conflict resolution plan in place can provide a roadmap for mitigating disputes, ensuring they don’t derail the project.

Example: In a research project studying the effects of a new medical treatment, disagreements among researchers on the interpretation of clinical trial results were resolved through impartial data analysis and discussion.

#8 Celebrate Achievements and Milestones

Recognise and celebrate the achievements and milestones reached throughout the collaboration. Acknowledging the contributions of team members fosters a sense of accomplishment and motivates continued collaboration.

Recognising and celebrating the achievements and milestones reached throughout the collaboration is essential for morale and motivation. Acknowledging the contributions of team members fosters a sense of accomplishment and a desire to continue collaborating on future endeavours.

These celebrations can be both formal, such as awards or acknowledgments in publications, and informal, like team gatherings or acknowledgments in meetings.

Example: In a collaborative effort to map the human brain, researchers marked significant discoveries and breakthroughs with publications, press releases, and public presentations.

#9 Evaluate and Reflect on the Collaboration

Periodically assess the progress and effectiveness of the collaboration. Collect feedback from team members to identify areas for improvement and make necessary adjustments to the research process .

Periodic reflection on the collaboration’s progress and effectiveness is necessary for continuous improvement. Collecting feedback from team members can reveal areas where adjustments are needed in the research process. This feedback loop ensures that the collaboration remains dynamic and responsive to changing circumstances and project requirements.

Example: Research institutions often conduct post-project evaluations to gauge the impact and success of collaboration, allowing for continuous improvement.

#10 Disseminate Findings and Share Knowledge

Effective research collaboration should culminate in the dissemination of findings to the academic community and beyond. Publish papers, present at conferences, and engage in knowledge-sharing activities to ensure the research has a meaningful impact.

Effective research collaboration culminates in the dissemination of findings to the academic community and beyond. Publishing papers, presenting at conferences, and engaging in knowledge-sharing activities are essential steps to ensure that the research has a meaningful impact. It’s the bridge that connects your collaborative efforts with the broader world, allowing others to benefit from your collective expertise and discoveries.

Example: Collaborative research in astronomy led to the publication of ground-breaking discoveries, such as the first image of a black hole, which captured global attention and expanded our understanding of the cosmos.

Key Collaboration Tips

Clear Communication : Maintain open and frequent communication with your collaborators to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Collaborative Tools : Utilise digital tools and platforms to streamline collaboration and data sharing.

Conflict Resolution : Develop a plan for addressing conflicts that may arise during the research collaboration.

Feedback Loop : Regularly seek feedback from team members to improve the collaboration’s efficiency and effectiveness.

Publication Plan : Discuss authorship and publication plans early in the project to avoid disputes later.

In the ever-evolving landscape of academia, research collaboration stands as a beacon of progress and innovation. It empowers scholars to pool their knowledge, skills, and resources, thereby tackling complex challenges and making substantial contributions to their fields. However, effective research collaboration demands careful planning, clear communication, and a commitment to nurturing a collaborative culture.

As you embark on your collaborative journey, remember the importance of defining clear objectives, selecting complementary team members, and establishing robust communication channels. Develop a research collaboration agreement, leverage technology for data sharing, and foster a culture of collaboration within your team. Be prepared to manage conflicts constructively and celebrate your achievements along the way. Regular evaluation and knowledge dissemination will ensure that your collaborative efforts have a lasting impact on your field.

Useful Resources

Research collaboration is not without its challenges, but with the right strategies and a dedicated team, you can overcome them and contribute to the advancement of knowledge. Embrace the opportunities that research collaboration offers, and may your collaborative endeavours lead to ground-breaking discoveries and meaningful contributions to your academic discipline.

Way With Words – Offers professional transcription services that can assist in research collaboration efforts by providing accurate and timely transcriptions of academic materials, interviews, and meetings.

Research Gate – A platform that connects researchers, providing access to a vast repository of academic papers and collaborative research opportunities.

Engagement Questions

- What challenges have you encountered in your research collaborations, and how did you address them?

- How do you think emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and data analytics, will impact the future of research collaboration?

- Can you share an example of a research collaboration that had a significant impact on your academic field, and what lessons can be drawn from it?

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Office of Undergraduate Research

Tips for successful collaborative research projects.

By Grace Vaidian, Peer Research Ambassador

Establish Clear Communication Channels

I started my first collaborative research project as a sophomore. The project had a big scope, with the UConn School of Pharmacy, UConn Health, and St. Francis Hospital being involved. Various professors, clinicians, and undergraduates had to work together. This project was the first time I undertook research with a team. There was definitely a learning curve as I adjusted to the collaborative aspects of the study. One of the first things I learned was that the cornerstone of any successful collaboration is clear and open communication.

Establishing effective channels for communication is essential, whether it’s through regular meetings or shared online platforms. Platforms like Google Workspace, Microsoft Teams, or project management tools such as Trello can enhance communication, facilitate document sharing, and streamline project organization.

Define Roles and Responsibilities

Collaboration with a partner came up again when I decided to apply for a Change Grant. I recruited a partner to help me with the project and balance the workload. One of the first things we did together was establish who was doing what. This allowed the process of starting the project once we received the grant to go very smoothly. Clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of each team member from the outset is vital to a group project. Establishing expectations regarding individual contributions, deadlines, and specific tasks helps in maintaining accountability and ensures that everyone plays a vital role in the project’s success.

Establish a Clear Project Timeline

For the Change Grant, my project partner and I wrote out a timeline detailing when we wanted to have each goal done by. Since the project has many smaller subtasks, this was extremely helpful to keep everything on track. A well-structured timeline helps manage expectations and ensures that the project progresses smoothly, avoiding last-minute rushes and unnecessary stress.

Embrace Diversity of Perspectives

Something I did not consider when starting my first collaborative project was how important the team members’ different perspectives would be. As time went on, I realized that our best solutions were products of group discussion. Encouraging open discussions and valuing the unique perspectives that each team member brings to the table can allow a project to thrive. Embracing diversity leads to a richer pool of ideas and fosters a dynamic and innovative research environment.

Regular Check-ins and Progress Updates

In line with establishing communication channels, schedule regular check-ins to discuss progress, address challenges, and provide updates. For my sophomore year research study, we had biweekly Teams meetings where we went over project progress. During those meetings we were able to identify weaknesses in our methods and implement necessary changes.

Cultivate a Positive Team Culture

Lastly, fostering a positive team culture is crucial for the success of collaborative research. I have seen this firsthand in the research lab I am currently in. I n the lab up to eight undergrads work together at a time. I noticed our tasks went smoother and we made less mistakes when we conversed and became friendly. A supportive and positive environment contributes to higher morale, increased productivity, and a more enjoyable research experience.

Conclusion

As an undergraduate navigating the realm of collaborative projects, I’ve come to realize the value of working on a team for research. Through effective collaboration, not only do you contribute to advancing your research, but you also cultivate skills that will serve you well in your academic and professional journey.

Grace is a senior double majoring in Molecular & Cell Biology and Drugs, Disease, and Illness (Individualized Major). Click here to learn more about Grace.

A Nature Research Service

- On-demand Courses

- Work with others

Introduction to Collaboration

For researchers in the natural sciences who wish to participate in collaborative projects

14 experts in collaboration, including researchers, funders, editors and professionals

2.5 hours of learning

15-minute bite-sized lessons

1-module course with certificate

About this course

‘Introduction to Collaboration’ introduces the idea of research collaboration and how becoming a more effective collaborator could help to further both your research and your career. Even if you’ve already participated in collaborative research, this course provides a useful introduction to the topic of research collaboration, as well as valuable context and advice around the pros and cons of collaborative projects and how they can help you reach your goals.

What you’ll learn

- Why collaborative research is becoming more prevalent

- The pros and cons of collaborating

- The specifics of collaborating with industry

- How collaborative projects can help advance your research and career

Free Sample Introduction to collaboration

8 lessons 2h 30m

Free Sample Introduction to collaboration: Free sample - section

No subscription yet? Try this free sample to preview lessons from the course

2 lessons 30m

Start this module

Developed with expert academics and professionals

This course has been created with an international team of experts with a wide range of experience, including:

- Interdisciplinary and international collaborations

- Publications resulting from collaborative research

- The sociology of collaboration

- Collaborative tools

- Science communication

- Funding opportunities for collaborative efforts

- Institutional support for research collaboration

Tulika Bose

Professor of Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Senior Editor and Team Leader, Nature , Springer Nature

Mark Hahnel

Founder, Figshare

W. John Kao

Chair Professor of Translational Medical Engineering, The University of Hong Kong

Chief Editor, Nature Biomedical Engineering, Springer Nature

Paola Quattroni

Research Funding Manager (Data), Cancer Research UK

Kathrin Zippel

Professor of Sociology, Northeastern University

Advice from experienced collaborators

The course has additional insights through video interviews from:

Louise Ashton

Assistant Professor, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong

J. Michael Cherry

Professor of Genetics, Stanford University

Adriane Esquivel Muelbert

Research Fellow, University of Birmingham

Brian Nosek

Executive Director, The Center for Open Science

George Pankiewicz

Unified Model Partnerships Manager, Met Office

Doris Schroeder

Director of Centre for Professional Ethics, UCLan School of Sport and Health Sciences

Malcolm Skingle

Director, Academic Liaison, GlaxoSmithKline

Discover related courses

Participating in a collaboration.

Build your skills to make a more meaningful contribution to your collaborative projects

Leading a collaboration

Prepare yourself for all aspects of leading on a collaborative project

Access options

For researchers.

- Register and complete our free course offering , or try a free sample of any of our paid-for courses

- Recommend our courses to your institution, so that we can contact them to discuss becoming a subscriber

For institutions, departments and labs

Find out which of our subscription plans best suits your needs See our subscription plans

Does my institution provide full course access?

When registering, you’ll be asked to select your institution first. If your institution is listed, it has subscribed and provides full access to our on-demand courses catalogue.

My institution isn’t listed!

Select „other“ and register with an individual account. This allows you to access all our free sample course modules, and our entirely free course on peer review. You might also want to recommend our courses to your institution.

I am in charge of purchasing training materials for our lab / department / institution. Buy a subscription

Start this course

Full course access via institutional subscription only. More info

Institutions, departments and labs: Give your research full access to our entire course catalogue

Image Credits

View the latest institution tables

View the latest country/territory tables

How to collaborate more effectively: 5 tips for researchers

Participating in a collaborative effort can be extremely challenging. To get the most out of it, you need a strategic approach.

Andrea Aguilar

Credit: DrAfter123/Getty Images

28 January 2020

DrAfter123/Getty Images

A successful collaboration can achieve high-impact findings and give you access to new funding sources and expertise. It can also be a great opportunity to think about the tools and outputs that can make your research more accessible to your peers and the public.

Here are five tips to help you manage collaborative projects more efficiently, from the Nature Masterclasses + online course, Effective Collaboration in Research .

1. Be strategic – and don’t overcommit

It can be tempting to accept every offer to team up, but it’s not a quick, easy, or cheap way to achieve a goal.

Carefully assess the time and resources that would be required for a potential collaborative project and decide whether it fulfils a specific need in your research and if it will help you achieve your career objectives.

2. Create a collaboration agreement

Whether you’re setting up a research collaboration or participating in someone else’s project, it’s a good idea to record a framework in a formal document (“collaboration agreement”).

These contracts are often used in large and medium-sized collaborations, or in partnerships with industry, but you can choose to create a written collaboration agreement for a project of any size and scope.

“It sounds very dry and impersonal, but it’s a way to show that this is being done professionally and is done with good intention,” says John Kao, chair professor of translational medical engineering at the University of Hong Kong, in the Nature Masterclasses ’ online course on research collaboration.

“That transparency really helps to build trust.”

Your collaboration agreement can outline the key goals for the project, as well as timelines, roles and responsibilities, intellectual property, and authorship for any written outputs (especially publications).

Discussing, agreeing, and recording these things at an early stage helps to ensure that there are no surprises partway through the project.

3. Communicate your failures, not just your success

Clear and regular communication is crucial to the success of any research collaboration, and communicating delays or problems should not be seen as ‘admitting failure’.

Knowing about a delay as early as possible will be useful for the leader of the collaboration and will enable them to adapt the timeline or task-list accordingly.

Mark Hahnel, founder and CEO of online open access repository, Figshare, and expert contributor to the Nature Masterclasses ’ online course, says there is no such thing as too much communication in a collaborative project. “If you think you are over-communicating, you’re not,” says Hahnel. “Communication is only ever a good thing [in a collaboration].”

4. Embrace all types of outputs, not just papers

Common outputs of collaborative efforts include scientific publications, preprints, datasets, and conference presentations and posters. These will likely be built into your collaboration framework and management plan.

But you might decide to create further types of outputs to help you generate additional value and impact.

Creating a website can help you communicate your results to the public, and make your project more visible and accessible to other academics and potential collaborators. This can also be a good place to share other outputs you might create, such as images, maps, videos, or animations.

Interactive outputs such as simple video games and smartphone applications can also be good option, depending on the goals of your project.

Be sure to revisit your outputs regularly throughout your collaboration to see if there are any new opportunities that you might not have considered earlier. This becomes particularly important as you reach the end of a planned set of experiments or grant funding.

“We created a website where people can come and measure their own implicit biases,” Brian Nosek, executive director of the Center for Open Science and a Nature Masterclasses collaboration expert, says of one of his first psychology projects.

“It's a great instructional tool about this area of research and a great way to collect some data about how these biases might operate,” says Nosek. “The datasets generated from that have potential uses far beyond what we considered as the initial collaborative team.”

5. Learn what it takes to be a good team player

One of the great strengths of collaborative research is the innovation that comes from bringing together researchers of different backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives. Sometimes it can seem hard to adapt to different ways of thinking and working, but being flexible and open to new ideas will pay dividends.

“Even though you might be the world expert on something, be prepared to allow yourself to think that you might not know everything about it,” says Nature Masterclasses collaboration expert, George Pankiewicz, a collaborations manager at the MET Office in the UK.

“There are others who will bring great insight. They may not be a world expert, but they may have something to contribute.”

For more tips on how to collaborate, see the Nature Masterclasses online course, Effective Collaboration in Research and try the one-hour free sample .

+ Disclosure: Nature Masterclasses are run by Nature Research, part of Springer Nature, which also publishes the Nature Index.

Sign up to the Nature Index newsletter

Get regular news, analysis and data insights from the editorial team delivered to your inbox.

- Sign up to receive the Nature Index newsletter. I agree my information will be processed in accordance with the Nature and Springer Nature Limited Privacy Policy .

Collaborative Science

It is essential for collaborating researchers to establish a clear management plan at the beginning of the endeavor in order to avoid the potential difficulties which they might otherwise encounter. This plan should include the goals and direction of the study, responsibilities of each contributor, research credit and ownership details, and publication technique. Team members must be open with one another, keeping colleagues informed of developments, changes and problems.

Transparency and communication are key to building successful research collaborations

Further reading

- How to build up big team science: A practical guide for large-scale collaborations Baumgartner, H. A., et al., Royal Society Open Science , 2023

- Adversarial collaboration Rakow, T., In O’Donohue, W., et al. (Eds.), Avoiding Questionable Research Practices in Applied Psychology, Springer, 2022

- Ghosted in science: How to move on when a potential collaborator suddenly stops responding Simha, A., Nature , May 26, 2023

- TSAG pilot Implementation study of team science trainings and interventions University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research

- Enhancing the effectiveness of team science Cooke, N. J., & Hilton, M. L. (Eds.), The National Academies Press, 2015

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Collaborative Research: What It Is, Types & Advantages

As the world becomes increasingly complex, collaboration has become more critical. Researchers must work together to solve complex problems and make informed decisions. Collaborative research is the key to developing solutions that can have a significant impact on society.

In the field of market research, collaborative research can take many forms. For example, a business might partner with a university to conduct research on consumer behavior. The business can provide real-world data and insights, while the university can provide the academic rigor and expertise needed to analyze the data and draw meaningful conclusions.

While research is the foundation for forming knowledge, collaboration is a strategy to deal with situations that seem challenging to solve individually. Therefore, this article aims to discuss the potentialities of collaborative research in practice, analyze how this collaboration can be developed, and reflect on problems that may arise during the development of these works. Let’s talk about that.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

What is Collaborative Research?

Collaborative research is a partnership between two or more parties who work together to achieve common goals. In the context of market research, it is a way for researchers from different backgrounds, such as industry and academia, to bridge the gap between the theoretical and the practical.

LEARN ABOUT: Theoretical Research

When done correctly, collaborative research can lead to groundbreaking discoveries and innovations that benefit everyone involved. It refers to subjects in which several entities -generally of a different nature- share an interest in the execution of a project, the effort to develop it, the risks, and ownership of the results according to their diverse contribution to obtaining them.

The grounds or principles from which this knowledge is built can be identified in two areas: on the one hand, the reflective and consolidated capacity of the teacher to carry out an analysis and, based on this, assess the results of their experience. On the other hand, the paradigm, schemes, models, and frames of reference support and endorse this functional knowledge’s construction.

Collaborative Research Types

Collaborative research can be either homogeneous or heterogeneous. Homogeneous research involves individuals or groups that share similar backgrounds or perspectives, while heterogeneous research involves individuals or groups with diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Both types of collaborative research have their advantages and can lead to new insights and discoveries.

1. Homogeneous

It occurs when the research team members are similar in terms of their backgrounds, expertise, and research interests. This type of collaborative research can be beneficial because team members may share similar perspectives and approaches to research, which can lead to more efficient and effective collaboration.

2. Heterogeneous

On the other hand, involves team members with diverse backgrounds, expertise, and research interests. While this type of collaboration can be more challenging, it can also lead to more innovative and creative research outcomes. Heterogeneous teams can bring different perspectives and ideas to the table, which can lead to new insights and approaches that might not have been possible with a more homogeneous team.

Various types of research can be considered collaborative. Some of the main types include participatory action research, community-based participatory research, and interdisciplinary research. Let’s explore them.

- Participatory action research involves researchers and community members working together to identify and address issues within the community. This type of research aims to empower the community and promote social change.

- Community-based participatory research involves community members and researchers working together to develop and conduct research that addresses the needs and concerns of the community. The community is an equal partner in the research process, and the ultimate goal is to improve the health and well-being of the community.

- Interdisciplinary research involves researchers from different disciplines working together to address a complex research question. This type of research allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the research problem and can lead to innovative solutions.

Collaborative research is a powerful approach that brings together individuals from diverse backgrounds to work towards a common goal. It promotes shared learning and innovation, ultimately leading to better outcomes than traditional research methods.

By combining the strengths of multiple perspectives, collaborative research creates a stronger foundation for the development of new ideas and solutions.

It’s essential to understand the different types of collaborative research and how they can contribute to advancing knowledge in various fields. With this understanding, we can begin to appreciate the value of collaborative research and its potential for creating positive change in the world.

Advantages & Disadvantages of Collaborative Research

One of the biggest advantages of collaborative research is that it allows businesses to tap into the expertise of researchers who have spent years studying a particular field. By working with experts in a particular field, businesses can gain a deeper understanding of the market and develop more effective strategies for success.

Another advantage of collaborative research is that it can help businesses stay ahead of the curve. By partnering with universities and other research institutions, businesses can gain early access to the latest research and technology. This can be a significant advantage in a rapidly changing market.

However, collaborative research is not without its challenges. For example, businesses and researchers may have different goals and priorities. Businesses are often focused on the bottom line, while researchers may be more concerned with the pursuit of knowledge. Additionally, different organizations may have different cultures and ways of working, which can lead to conflicts and misunderstandings.

Despite these challenges, collaborative research is a powerful tool that can drive innovation and change. By working together, businesses and researchers can create solutions that are more effective, efficient, and sustainable than those that either party could develop on their own.

Collaborative research is a critical tool for businesses and researchers in the field of market research. It allows for the creation of new ideas, technologies, and solutions that benefit society as a whole. With collaboration, we can bridge the gap between theory and practice and create a brighter future for all.

QuestionPro provides a platform where multiple researchers or team members can collaborate on a single survey or research project, share insights, and analyze data together in real time.

It offers various features such as customizable surveys, question branching, and skip logic that allows researchers to create complex surveys tailored to their research needs.

Join QuestionPro today for free and start conducting collaborative research with ease! Our platform offers a wide range of features and tools that will help you gather and analyze data, collaborate with your team members, and make informed decisions. Sign up now and take your research to the next level!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Employee Recognition Programs: A Complete Guide

Sep 11, 2024

A guide to conducting agile qualitative research for rapid insights with Digsite

Cultural Insights: What it is, Importance + How to Collect?

Sep 10, 2024

Was The Experience Memorable? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Collaborative Research: Best Practices for Successful Partnerships

Collaborative research has been on the rise in the past decades. It holds particular significance in its potential to deal with complex research problems effectively. However, given the diverse group of people involved in a typical research project (across disciplines, institutions, or countries) and the varied goals and expectations that follow, the possibilities for challenges and difficulties are much more significant. Today, with the growing trend toward collaborative research projects , it is crucial for researchers to follow some basic guidelines that will help foster effective collaboration and lead to eventual success. The following section presents a discussion of the best practices that can be adopted for successful research partnerships.

Table of Contents

Best practices for successful research partnerships

Clear communication .

Clear, unambiguous, and regular communication and information sharing are crucial for successful research partnerships. This cannot be compromised as it can lead to confusion and misunderstanding. The criticality of effective communication becomes even more relevant in international collaborations. Experts suggest creating a schedule or a formal agreement that clearly outlines from the very start the roles and responsibilities of each collaborator, the timelines, authorship, intellectual property rights and other details pertaining to the research and study process.

Further, team meetings are essential and must be organized regularly to ensure team members are aligned with the research goals and are able to provide updates on developments and challenges. This not only ensures that the research project stays on track but also lends a certain transparency and clarity to all collaborators. Also, creating a schedule or to-do list and updating it regularly ensures that the momentum of the project can be maintained. When establishing clear communication channels, it is essential that collaborators mutually decide on the frequency of communication, the agreeable method of communication (in person, via email or virtual communication), the point of contact, and the work-time cultures to be followed.

Maintain a supportive environment

Cultivating mutual trust and respect is essential in making collaborative research projects work efficiently and productively. Where team members may be from different disciplines, institutions or regions depending on the type of collaboration, it is essential to leverage the diverse perspectives and skill sets that they bring to the table. Active listening, valuing diverse views, keeping an open mind, and encouraging constructive feedback are all needed to maintain a supportive environment in the collaborative process.

Foster an inclusive space for the team

For an effective research collaboration process, it is important to encourage interdisciplinary interactions and cross-pollination of ideas from the initial stages so that they can result in innovative, integrated, methodological, and conceptual frameworks. A culture of collaboration and knowledge sharing needs to be promoted to spark a healthy sharing of innovative ideas and concepts.

Ensure effective project management

The creation of a project management framework and project plan is a helpful resource for effective collaborative research. Vagueness in roles and responsibilities or timelines can cause delays and hinder the progress of the research project. Hence, the project management framework should lay out the objectives, assign clear roles and responsibilities to each member, establish project deliverables and define clear timelines. These need to be discussed with all the team members at the planning stage itself so that everyone is aligned and agreeable to the expectations. These also need to be periodically reviewed so that necessary plan adjustments can be carried out, taking on board the views of the team members.

Allocation and management of resources

Equitable research partnerships need to be emphasized in collaborative research. Clearly defining research needs and allocating resources without disparities need to be ensured by both the team lead and funding agencies. In cooperative research, the presence and management of a wide variety of data is a challenge. Organizational mechanisms and measures need to be put in place to enable the sharing of such data with all the members and make select data accessible on public research sites. For efficient conduct of research, mechanisms for equipment usage by team members also need to be ensured.

Addressing conflicts

Collaborative research can face numerous internal challenges and conflicts. For example, there may be strong disagreements among team members, or some members may feel that the project is not in line with the agreed goals and expectations, while some may feel the absence of clear communication. It is essential to be sensitive to these challenges and conflicts and address them proactively as they arise through open discussions and collaborative solutions. Wherever necessary, support from project mentors should also be enlisted.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Research Impact: Types and Tips for Academics

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

212-460-1500

5 Types of Research Collaboration

October 5, 2023

In a bygone era, nostalgically deemed “little science” researchers worked independently on projects that were only widely shared with others after completion. World War II, however, ushered in the age of “ big science ,” with a movement towards large-scale projects, often supported by outside funding, and conducted by teams of researchers.

Since then, these collaborative practices have continuously expanded alongside technology, global economics, and digital communication. Today, researchers work in diverse teams unbound by the limitations of geography, status, or even field of expertise.

Because contemporary research addresses complex global issues, sharing knowledge and resources through collaboration is vita l. By exploring the 5 main types of collaborative research, this article can help researchers prepare for developing these mutually rewarding partnerships.

1. Collaboration within an academic institution

This category includes various configurations of faculty, staff, administrators, and students who will collaborate on research projects. The situation may be as informal as senior students helping novices navigate the research process, or as formal as tenured faculty offering unique skills to complicated research questions.

While these teams may form within a single department, they develop between departments and across disciplines. One advantage of partnering within an institution is the ease of communication. It allows members to meet face to face regularly, review their progress, and make adjustments in real time.

2. Collaboration with other academic institutions

Collaboration between academic institutions typically forms when a Primary Investigator invites Junior researchers to help carry out various components in the research methods of an already funded project. Collaboration between institutions creates mutual benefits through the sharing of often expensive and limited resources, like specialized equipment and broader study participants.

For Senior researchers, these partnerships often offer fortuitous insights and unique viewpoints that enrich the research process and ultimately improve the project’s outcomes. On the other hand, Junior researchers gain valuable experience, expand their professional network, and improve their credibility through association with an established research program.

3. Collaboration with a government entity

When policy makers and researchers share a common concern or question, collaboration can significantly improve the progression towards an outcome beneficial to society. The form and extent of these partnerships depends on both the contributions and the requirements of each participant.

Government agencies may act as financial collaborators by offering resources and funding opportunities for research projects related to specific interests and targeted goals. In other instances, they may solicit support from research experts to address a definitive issue, like COVID-19.

While governmental organizations often post research collaboration opportunities, the possibilities are reciprocal. Researchers may also contact relevant agencies to submit proposals requesting cooperation on a project.

4. Collaboration with private industry

Rapidly changing businesses that thrive on innovation are pushing the scope and influence of collaboration between academic researchers and the private sector. In exchange for resources and visibility, researchers provide expertise in the development of new products and technologies.

Partnerships with academic researchers can further invigorate companies, extricating them from stagnant best practices by inciting continuous improvement. Overall, the skills and knowledge of both groups are essential to the transition from research to development of the advancements in products, methods, and services that drive society forward.

5. Collaboration with international researchers

As globalization continues to alter the ways that people, organizations, and nations interact, the need for collaboration between international researchers and institutions grows. By broadening the cultural perspectives and applications of a research project, these partnerships increase the value of both the process and its outcomes.

Sometimes connections made during global conferences are nurtured into collaborative efforts. Students and junior researchers may forge relationships through study abroad and exchange programs. And, other times, researchers who share common goals and yet are separated by political borders and national objectives can find a common ground through collaboration.

Communication in collaboration

The success of every type of research collaboration hinges on the quality of communication between team members . While the forms of communication seem to expand daily, not all are appropriate or even plausible in every situation.

Because face to face interactions typically produce rich and meaningful results in real time, they are consistently worthwhile. Other modes of communication like phones, mail, digital platforms, and video conferencing should be used to supplement, not replace, in person meetings when collaborators are in close proximity to one another.

When differences in time and distance prevent face to face communication, collaborators must create synergy by updating one another on progress and setbacks, and sharing amended interpretations and objectives. The best way to accomplish these goals is by establishing several formal and informal contact options from the beginning with regularly scheduled meetings.

Bottom line

In this interconnected world, researchers must recognize the power of collaboration in the advancement of scientific knowledge and the discovery of global solutions. Through these collaborations, researchers break down geographical barriers, disciplinary boundaries, and institutional limitations to form diverse teams that work together to address complex research questions.

Effective communication stands as the cornerstone of success through each step of the collaborative process, from initial team building to post-publication. While technology enables a range of communication methods, face-to-face interactions remain crucial for meaningful and rich results.

Through mutually rewarding partnerships, researchers can pave the way for the realization of innovations that positively impact humanity. By understanding the types of research collaboration, scientific knowledge will undoubtedly become more diverse, shaping an increasingly democratic and equitable world.

About the author

Charla Viera, MS

Charla Viera graduated from The University of Washington with a BA in Urban Studies and a BA in Environmental Studies. Her undergraduate research included household energy consumption and practical greywater systems. She later earned an MS in Library and Information Science from Texas Woman's University. Her graduate thesis focused on the role of libraries as community anchors in rural Texas communities.

Jonny Rhein

Leave a comment

Please note, comments must be approved before they are published

Use this popup to embed a mailing list sign up form. Alternatively use it as a simple call to action with a link to a product or a page.

Age verification

By clicking enter you are verifying that you are old enough to consume alcohol.

Search solutions

Your cart is currently empty..

- Getting Published

- Open Research

- Communicating Research

- Life in Research

- For Editors

- For Peer Reviewers

- Research Integrity

5 ways that collaboration can further your research and your career

Author: guest contributor.

Collaborative research has become more prevalent globally over the past 50 years and researchers are increasingly required to work across disciplines, institutions and borders. With the goal of helping researchers make the most of these collaborations, Nature Masterclasses has launched a new online course called " Effective Collaboration in Research ." Read on for more information about the course and to learn how collaborating efficiently can help advance your research and your career.

Collaborative projects are inevitably associated with challenges that you might not experience with an individual research project. However, they can also offer many benefits. Here are just some of the ways in which collaborations can benefit your research and your career.

- Maximise outputs. By combining expertise and resources you can answer bigger and more complex scientific questions and expand the breadth of your research.

- Maximise impact. Research shows a positive correlation between collaborative papers and a high level of citations. For example, in one analysis of 28 million papers from the humanities and the natural, medical, and social sciences published between 1900 and 2011, papers with more authors received more citations, particularly if the authors were from different institutions 1 .

- Attract funding. Generating outputs that have an impact on policy, practice, industry, or the general public can increase your chances of getting funded. In addition, some funding bodies now give priority to international and industry-academia collaborations. For example, the EU Commission’s Horizon 2020 program, which offered nearly 80 billion Euros of funding between 2014 and 2020 for research projects tackling societal challenges, prioritized collaborative projects.

- Expand your network. Working collaboratively can help you meet potential future employers, mentors, and collaborators.

- Embrace the new. Collaborations are opportunities to learn new skills, make new friends, gain a new perspective, and join stimulating discussions and with experts in your field or complementary fields.

To help researchers maximise the benefits of collaborating, Nature Masterclasses has launched a new online course called " Effective Collaboration in Research ." The 8-hour course was developed with a panel of experts of researchers from across the international scientific community (academic and industry), Nature Research Editors, funding bodies and creators of collaborative tools for researchers—all of whom have extensive experience and expertise in conducting, publishing and funding collaborative research.

The course includes a 1-hour free sample , enabling researchers to try the course for free after registering on Nature Masterclasses . Access to the full course requires a subscription; subscriptions are available to labs, departments and institutions.

Nature Masterclasses is a Springer Nature product providing professional development training to researchers, via online courses and face-to-face workshops.

Claire Hodge is a Senior Marketing Manager at Nature Research. She is a member of the Researcher Services team, which provides services such as Nature Research Academies , Nature Research Editing Service and Nature Masterclasses to build the skills, confidence and careers of researchers.

Guest Contributors include Springer Nature staff and authors, industry experts, society partners, and many others. If you are interested in being a Guest Contributor, please contact us via email: [email protected] .

- career advice

- early career researchers

- Open science

- Tools & Services

- Account Development

- Sales and account contacts

- Professional

- Press office

- Locations & Contact

We are a world leading research, educational and professional publisher. Visit our main website for more information.

- © 2024 Springer Nature

- General terms and conditions

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Your Privacy Choices / Manage Cookies

- Accessibility

- Legal notice

- Help us to improve this site, send feedback.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Pharmacol

- v.51(3); May-Jun 2019

Collaborative research in modern era: Need and challenges

Seema bansal.

Department of Pharmacology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India

Saniya Mahendiratta

Subodh kumar, phulen sarma, ajay prakash, bikash medhi.

Most critically important scientific issues or innovative technologies can often be solved by working together of team of researchers from different backgrounds. The merging of different fields can make possible achieving of incredible goals. Collaborative research, therefore, can be defined as research involving coordination between the researchers, institutions, organizations, and/or communities. This cooperation can bring distinct expertise to a project. Collaboration can be classified as voluntary, consortia, federation, affiliation, and merger and can occur at five different levels: within disciplinary, interdisciplinary, multi-disciplinary, trans-disciplinary or national vs international. Collaborative research has the capabilities for exchanging ideas across disciplines, learning new skills, access to funding, higher quality of results, radical benefits, and personal factors such as fun and pleasure.

Need of Collaborative Research

Collaboration encourages the establishment of effective communication and partnerships and also offers equal opportunities among the team members. It honors and respects each member's individual and organizational style. Collaboration also increases the ethical conduct maintaining honesty, integrity, justice, transparency, and confidentiality.

Why Collaboration Required

Increased collaborations can save considerable time and money, and most often, breakthrough research comes through collaborative research rather than by adhering to tried and true methods. Further legislation, industry, and academia encouraged the collaboration between private sector and academia (e.g., the Bayh–Dole Patent Reform Act of 1980 is the United States legislation which allowed universities to negotiate patent rights with industrial partners).

Elements of Collaboration

- Collaboration establishes channels for open communication where participants need to be encouraged to take opportunities for the renewal of the older systems

- Engaging all partners and others where they should provide feedback and engage in self-reflection

- There should be an identification of stakeholders which can serve as the feedback loop as it will help better to understand cause and effect

- Collaboration also defines the clarity of roles and responsibilities

- To establish a professional environment and to respect different cultures of different organizations.

Various Forms of Collaborative Research

Mentor–mentee.

A mentor–mentee relationship is very crucial as the challenges experienced by the mentor will be faced by the mentees and it will be the duty of the current scientists to mentor the next generation of scientists. The mentor is responsible for holding regular meetings with mentees and to make sure that they are familiar with academic and nonacademic policies.

Collaborative research within disciplinary, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, and transdisciplinary

There are different kinds of collaboration such as intradisciplinary (team of researcher within the same department), interdisciplinary (team of researcher of different departments but different background), multidisciplinary (team of researcher of different background), or transdisciplinary (involvement of people from outside academia into the research process) and everyone aspire for common demands such as making of operational plans, communication between different research groups, sharing of credit and money, holding frequent meetings, and encouraging open communications.

Miscommunications can also be caused by working among different research disciplines and can be due to different understandings about science, vocabulary, or methods. Each and every working researcher has their own perspective of working, for example, some prefer verbal agreements and some consider written contracts. On the other hand, few are in favor of publishing every new finding and others prefer a single large publication after compilation of whole data.[ 1 ]

Challenges of collaboration

Collaborations can be a frequent source of problems. This can be due to many reasons such as sharing of credit and responsibility after joining of more than two people for a common purpose. Sometimes, collaborations do not get initiated due to unwillingness of sharing or working together. Sometimes, collaborations are often spoiled because of misunderstandings among the participants due to disagreement about what and when to publish and also due to discontent with a slow collaborator.

Global contribution of Indian scientists in research

According to Research Trends (2014), among the top 20 countries, on the basis of research output, India holds the position on the 12 th place, China on the 5 th place, Russia on the 10 th place, and Brazil on the 18 th place. On the contrary, ranking based on citations, India comes in the 19 th place, China in the 13 th place, Russia in the 17 th place, and Brazil in the 23 rd place. Among the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) countries, in terms of total number of documents produced, China leads the research output, whereas India and South Africa dominate depending on citation per document. It is also seen that South Africa is involved in a number of international collaborations, followed by Russia, Brazil, India, and China. The USA and some European countries such as the UK, Germany, France, and Italy seem to have considerable collaborations among the BRICS nation, but very little partnership is realized. Of these, India and China are active participating nations, whereas Russia and Brazil do not seem to be very enthusiastic.[ 2 ]

Even according to comparison made by the research group, India takes the lead in terms of research quality even if China produces more number of papers than India. This is on the basis of citations per article (CPA) which was an average of 2.71 between 2006 and 2010 while that for China was 2.21. It is evident that India's CPA is far below than that of the US, i.e., 6.45; however, it is shown that it is tremendously improved for India in the past 5 years. This is due to major contribution in the field of chemistry to the scientific society which is around 38% and was relatively low in health sciences (3.5%).[ 3 ]

Impact of Indian collaborative research globally

The contribution of India toward research globally is quite influential and hence has achieved the 6 th rank for publication of research papers. This is growing at an annual rate of 14% and at global level at an average of 4%. India is actively involved in bilateral science and technology agreements with over 40 countries and has also participated in global megaprojects such as CERN, the Thirty Meter Telescope International Observatory, and Gates Grand Challenges. India also supports three science and technology centers: independent organizations established under intergovernmental bilateral agreements with France, Germany, and the USA. Moreover, the government contributes to international networks such as the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, the European Molecular Biology Organization, and the Human Frontier Science Program.

Challenges of Collaborative Research in India

Individual challenges.

There is a scarcity of competent researchers in India. Most of the researches going on in our country are not methodologically sound. As far as scholarship is considered, it is an individualized endeavor, and academic frameworks for recognition, rewards, and promotions are supposed at individual level. For the promotion and tenure process, single-authored publications are given more credit as compared to collaborative work. Intellectual property rights are the central issue and occur in various categories of members in collaborative research.

Institutional challenges

This is because of differences in different approaches among the collaborating partners. For example, if a collaboration occurs between industry and institutional level, discrepancies do occur between objectives, different hypothesis, cultural differences, and issues with technology.

Challenges regarding funds

The most important challenge is less funds granted for research to universities as compared to small elite research institutions. This leads to less focus on research and more on teaching by the universities resulting in separation of education and research. Due to funding restrictions, most of the significant work of Indian research is in theoretical domain. For example, a collaborative project was undertaken by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in which a developmental study was conducted taking 30 HIV-positive patients and 18 HIV-related service providers for understanding of sexual risk-taking HIV-related disclosure and other behavioral patterns among HIV-positive individuals in Baroda, Gujarat. Patel et al .[ 4 ] shared that it took roughly 1½ years by the Institutional Review Board at Medical College of Baroda which was already reviewed by NIH, University of North Carolina, and ICMR, and as per the guidelines of ICMR, the compensation was also reduced to 500/day from 1000.

Systematic challenges

In India, the success of the scientists is prioritized by becoming an administrative head in research institutions rather than advancing research. Furthermore, the prevalence of ineptitude among the spectrum has made incompetent scientists to strengthen their weakness.

There is a culture of elitism in our Indian laboratories, where the manual work is done by laboratory assistants and scientists mostly just command orders.[ 5 ]

After thorough understanding of collaboration, it can be assumed that language, financial commitment, inadequate regulatory frameworks, and diverse interests are among the potential challenges in collaborative research. This can be successful if the collaborators respect each other and without involving their ego and also willing to give and take constructive criticism without being defensive. To conclude, the results of these collaborations will not only be seen in specific work done at the time of collaboration but also during the professional lifetimes of scholarship and publication.

- Open access

- Published: 20 January 2021

What makes a ‘successful’ collaborative research project between public health practitioners and academics? A mixed-methods review of funding applications submitted to a local intervention evaluation scheme

- Peter van der Graaf ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2466-2792 1 ,

- Lindsay Blank 2 ,

- Eleanor Holding 2 &

- Elizabeth Goyder 2

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 19 , Article number: 9 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5062 Accesses

5 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

The national Public Health Practice Evaluation Scheme (PHPES) is a response-mode funded evaluation programme operated by the National Institute for Health Research School for Public Health Research (NIHR SPHR). The scheme enables public health professionals to work in partnership with SPHR researchers to conduct rigorous evaluations of their interventions. Our evaluation reviewed the learning from the first five years of PHPES (2013–2017) and how this was used to implement a revised scheme within the School.

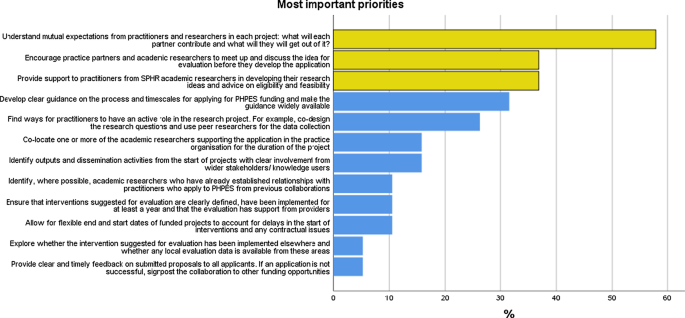

We conducted a rapid review of applications and reports from 81 PHPES projects and sampled eight projects (including unfunded) to interview one researcher and one practitioner involved in each sampled project ( n = 16) in order to identify factors that influence success of applications and effective delivery and dissemination of evaluations. Findings from the review and interviews were tested in an online survey with practitioners (applicants), researchers (principal investigators [PIs]) and PHPES panel members ( n = 19) to explore the relative importance of these factors. Findings from the survey were synthesised and discussed for implications at a national workshop with wider stakeholders, including public members ( n = 20).

Strengths : PHPES provides much needed resources for evaluation which often are not available locally, and produces useful evidence to understand where a programme is not delivering, which can be used to formatively develop interventions. Weaknesses : Objectives of PHPES were too narrowly focused on (cost-)effectiveness of interventions, while practitioners also valued implementation studies and process evaluations. Opportunities : PHPES provided opportunities for novel/promising but less developed ideas. More funded time to develop a protocol and ensure feasibility of the intervention prior to application could increase intervention delivery success rates. Threats : There can be tensions between researchers and practitioners, for example, on the need to show the 'success’ of the intervention, on the use of existing research evidence, and the importance of generalisability of findings and of generating peer-reviewed publications.

Conclusions

The success of collaborative research projects between public health practitioners (PHP) and researchers can be improved by funders being mindful of tensions related to (1) the scope of collaborations, (2) local versus national impact, and (3) increasing inequalities in access to funding. Our study and comparisons with related funding schemes demonstrate how these tensions can be successfully resolved.

Peer Review reports