ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia research: a bibliometric analysis.

- 1 Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, West China Hospital/West China School of Medicine, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2 Department of Periodical Press and National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 3 Chinese Evidence-Based Medicine Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

Background: Citation analysis is a type of quantitative and bibliometric analytic method designed to rank papers based on their citation counts. Over the last few decades, the research on dyslexia has made some progress which helps us to assess this disease, but a citation analysis on dyslexia that reflects these advances is lacking.

Methods: A retrospective bibliometric analysis was performed using the Web of Science Core Collection database. The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were retrieved after reviewing abstracts or full-texts to May 20th, 2021. Data from the 100 top-cited studies were subsequently extracted and analyzed.

Results: The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were cited between 245 to 1,456 times, with a median citation count of 345. These studies were published in 50 different journals, with the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America” having published the most ( n = 10). The studies were published between 1973 and 2012 and the most prolific year in terms of number of publications was 2000. Eleven countries contributed to the 100 top-cited studies, and nearly 75% articles were either from the USA ( n = 53) or United Kingdom ( n = 21). Eighteen researchers published at least two different studies of the 100 top-cited list as the first author. Furthermore, 71 studies were published as an original research article, 28 studies were review articles, and one study was published as an editorial material. Finally, “Psychology” was the most frequent study category.

Conclusions: This analysis provides a better understanding on dyslexia and may help doctors, researchers, and stakeholders to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of classic studies, new discoveries, and trends regarding this research field, thus promoting ideas for future investigation.

Introduction

Dyslexia is a common learning disorder that affects between 4 and 8% of children ( 1 – 3 ), and often persists into adulthood ( 4 , 5 ). This neurodevelopmental disorder is characterized by reading and spelling impairments that develop in a context of normal intelligence, educational opportunities, and perceptual abilities ( 4 , 6 ). Reading and spelling abilities can be affected together or separately. The learning abilities of children with dyslexia are significantly lower than those of their unaffected pairs of the same age. Generally, difficulties begin to show during the early school years. Dyslexia is a complex multifactorial disorder whose etiology has not been fully elucidated, and it has caused great social and economic burdens. Over the last few decades, the research on dyslexia has made some progress. For example, some studies have shown that dyslexia has a strong genetic background that can affect brain anatomy ( 7 , 8 ) and function ( 9 , 10 ). But a citation analysis on dyslexia that reflects these advances is lacking.

The publication of study results in scientific journals is the most effective strategy to disseminate new research findings. A high number of citations can indicate the potential of a paper to influence the research community and to generate meaningful changes in clinical practice ( 11 ). Citation analysis is a type of quantitative and bibliometric analytic method designed to rank papers based on their citation counts. The latest and up-to-date research findings on dyslexia are well-reflected in recent scientific papers ( 12 ), particularly in the most cited ones ( 13 , 14 ). By analyzing the most cited studies, especially the 100 top-cited studies, we can gain better insight into the most significant advances made in the field of dyslexia research over the course of the past several decades ( 15 ). This retrospective bibliometric approach has been used for many other diseases, such as diabetes ( 16 ), endodontics ( 17 ), cancer ( 18 ). However, to date, no bibliometric analyses have been conducted in the field of dyslexia. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to analyze the 100 top-cited studies in the field of dyslexia.

Materials and Methods

Search method and inclusion criteria.

This retrospective bibliometric analysis was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection database. The Web of Science Core Collection is a multidisciplinary database with searchable authors and abstracts covering a vast science journal literature ( 19 ). It indexes the major journals of more than 170 subject categories, providing access to retrospective data between 1945 and the present ( 20 ). On May 20th, 2021, we conducted an exhaustive literature retrieval, regardless of the country of origin, publication year, and language. The only search term used was “dyslexia” and the search results were sorted by the number of citations.

Article Selection

Two authors independently screened the abstracts or full-texts to identify the 100 top-cited articles about dyslexia. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Only studies that focused on dyslexia were included in subsequent analyses. Studies that only mentioned dyslexia in passing were excluded.

Data Extraction

The final list of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia was determined by total article citation counts. We extracted the following data for each article: title, authors, journal, language, total citation count, publication year, country, journal impact factor, type of article, and Web of Science subject category. If the reprint author had two or more affiliations from different countries, we used the first affiliation as the country of origin. If one article was listed in more than one subject category, the first category was selected. If one article had more than one author, we selected the first-ranked author as the first author and the last-ranked author as the last-author.

Data Analysis

SPSS 11.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) was used to count the frequency. We analyzed the following data: citation count, year of publication, country, the first author, journal, language, type of study, and Web of Science subject category.

Citation Analysis

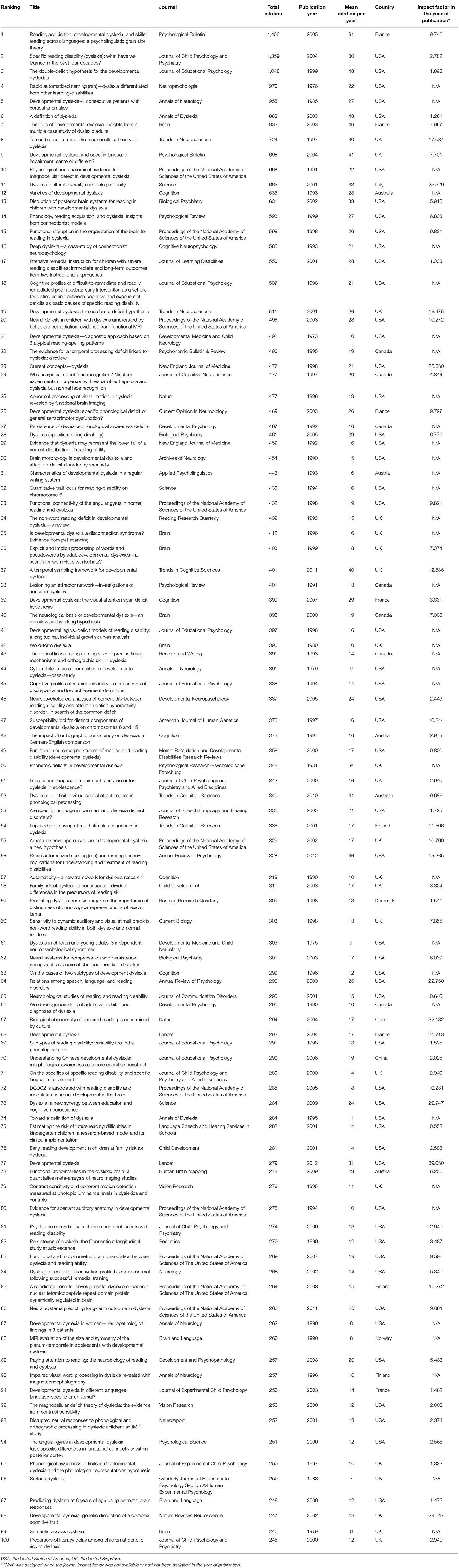

The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia based on total citations are listed in Table 1 . The total citation count for these 100 articles combined was 42,222. The total citation count of per study ranged from 245 to 1,456 times, with a median citation count of 345. Only 3 studies were cited more than 1,000 times, and the rest of the studies were cited between 100 and 1,000 times. The title of the top-cited study, which also had the largest mean citation per year count ( n = 91), was “Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages: a psycholinguistic grain size theory,” which was published by Ziegler et al. in Psychological Bulletin in 2005 ( 21 ). The second top-cited study, which also had the second-highest mean citation per year count ( n = 80), was published by Vellutino et al. ( 22 ). In addition, we also identified the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia based on mean citation per year, whose results were shown in Supplementary Table 1 .

Table 1 . The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia based on total citations.

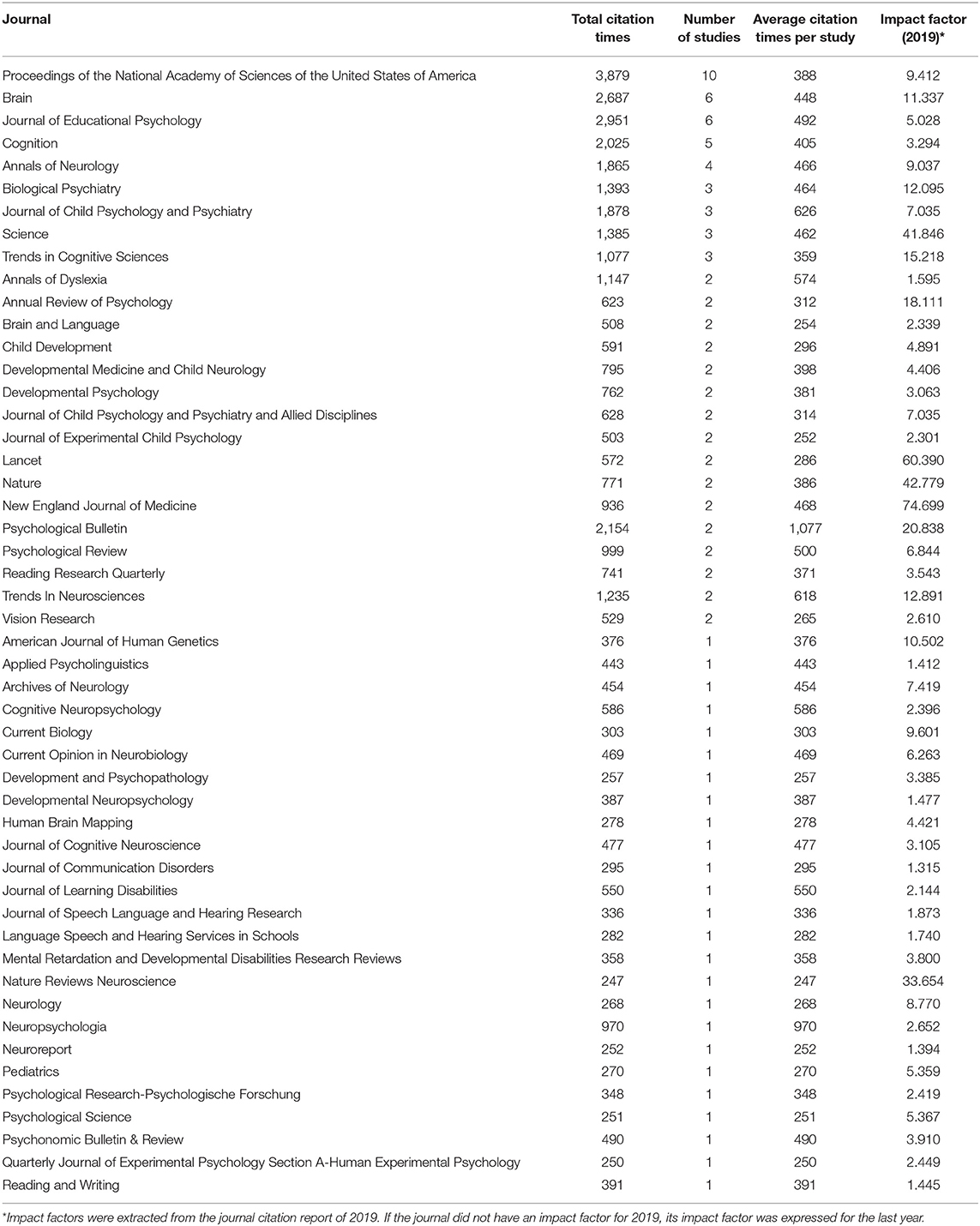

The different journals of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia and their associated impact factors are listed in Table 2 . The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were published in 50 different journals, with the top three in frequency being “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America” ( n = 10), “Brain” ( n = 6), and “Journal of Educational Psychology” ( n = 6).

Table 2 . Journals of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia.

The journal with the highest total citation count was “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.” However, the highest average citation count per study belonged to the journal “Psychological Bulletin.” The journal impact factors of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia ranged from 1.315 to 74.699. Of the 100 top-cited studies, 29 were published in a journal with an impact factor greater than 10. The standard “CNS” journals, with the exception of “Cell,” “Nature,” and “Science” published 2 and 3 studies, respectively. Regarding the top four medical journals, while the “New England Journal of Medicine” and “Lancet” published 2 studies each, no top-cited study was published by the “Journal of the American Medical Association” or the “British Medical Journal.”

Language and Year of Publication

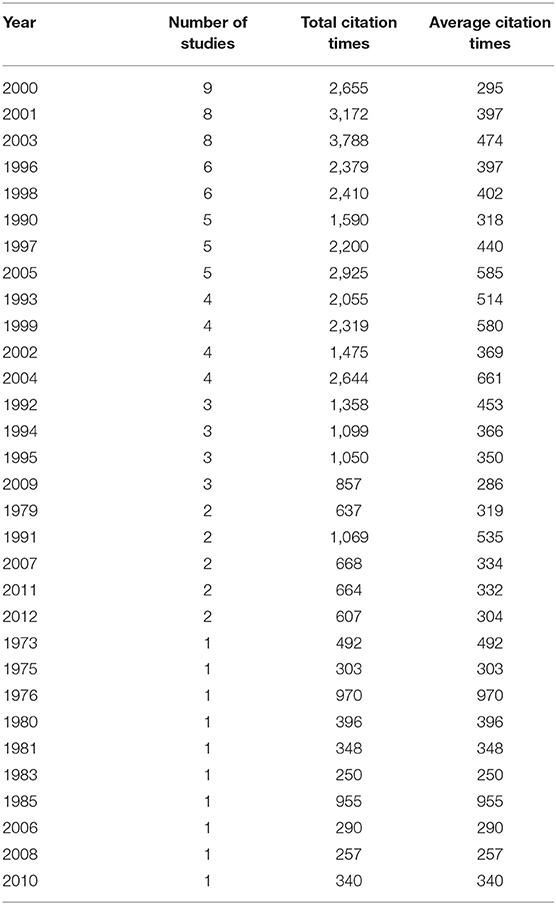

The 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were all published in English and were published between 1973 [by Boder et al. ( 23 )] and 2012 [by Norton et al. ( 24 ) and Peterson et al. ( 25 )] ( Table 3 ). The most productive years were 2000, 2001 and 2003, with 9, 8 and 8 published articles, respectively. The year of 2003 had the most total citations with a total count of 3,788 and an average citation count per study of 474.

Table 3 . Publication year of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia.

Countries and Authors

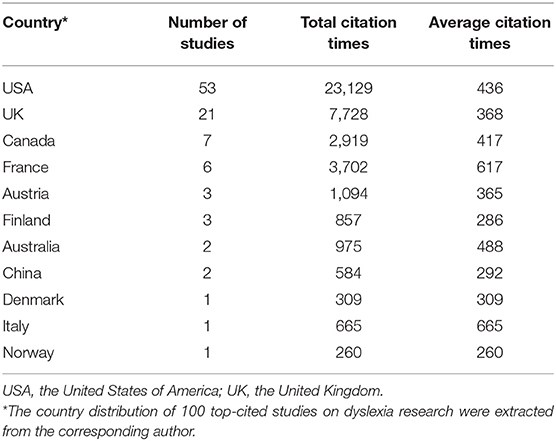

Eleven countries contributed articles to the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia ( Table 4 ). Most of the articles were from the USA ( n = 53), United Kingdom ( n = 21), Canada ( n = 7), and France ( n = 6). In addition, the USA had the highest total citation count (23,129), and Italy had the highest average citation count per study (665).

Table 4 . Countries of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia.

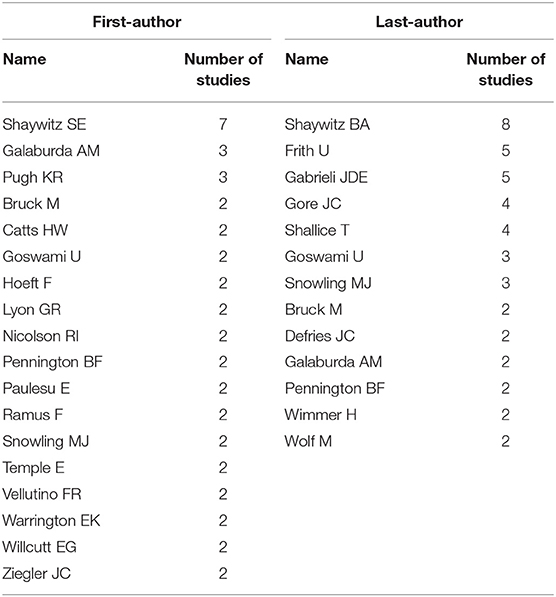

As shown in Table 5 , there were 18 first-authors and 13 last-authors who published more than one of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia. Among them, Shaywitz SE published the most top 100 articles ( n = 7) on dyslexia as the first author, followed by Galaburda AM ( n = 3) and Pugh KR ( n = 3). And for the last author, 8 studies of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia research were published by Shaywitz BA who was the most productive.

Table 5 . Authors with at least two first-author or last-author publications in the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia.

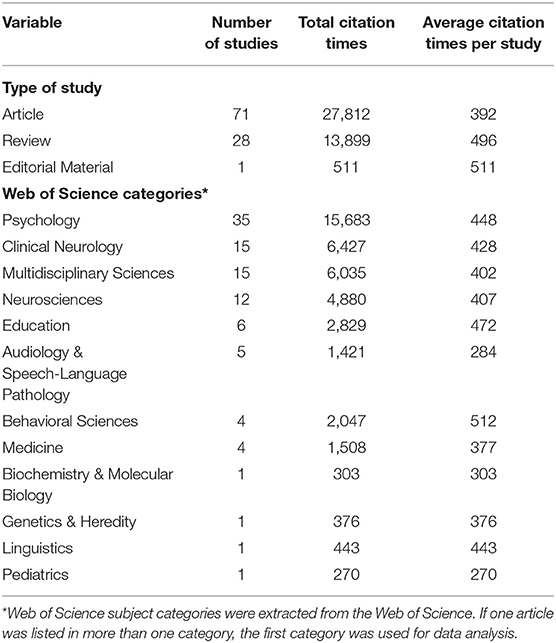

Publication Type and Web of Science Subject Categories

As shown in Table 6 , there were 71 studies in the form of an original research article, 28 studies in the form of a review article, and one study in the form of an editorial material publication. The total citation counts for each publication type were 27,812, 13,899, and 511, respectively. Although the type of original research article had the highest total citation count, it had the lowest average citation count per study. In addition, a total of 12 Web of Science subject categories were extracted. Among them, “Psychology” was the most frequent category associated with studies [35], followed by “Clinical Neurology” [15], and “Multidisciplinary Sciences” [15], “Neurosciences” [12], and “Education” [6]. Consistent with the number of studies, the subject categories of “Psychology” and “Clinical Neurology” also had the highest total citation counts (15,683 and 6,427, respectively). The “Behavioral Sciences” subject category had the highest average citation count.

Table 6 . Type of study and subject categories for the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia.

Although retrospective bibliometric approach has been conducted in many other diseases, to our knowledge, no citation analyses have examined publications on dyslexia. Therefore, this study is the first comprehensive analysis summarizing several features of the most influential studies on dyslexia. It has been suggested that a highly cited study can be considered as a milestone study in a related field and has the potential to generate meaningful changes in clinical practice ( 26 ). We believe that the present analysis of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia may be beneficial to the research community for the following reasons. First, the present study not only provides a historical projection of the scientific progress with regards to dyslexia research, but it also shows associated research trends and gaps in the field ( 27 ). Second, our findings provide critical quantitative information about how both the classic studies and recent advancements in the field have improved our understanding of dyslexia ( 28 ). Third, the present analysis may help journal editors, funding agencies, and reviewers critically evaluate studies and funding applications ( 28 ).

Our analysis discovered that the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were published in 50 different journals. This may reflect the fact that the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were very multidisciplinary in nature, unlike the top studies of other fields (e.g., psoriatic arthritis) where there is a more inherent researcher bias for journal selection ( 29 ). Of the 100 top-cited studies, 29 were published in a journal with an impact factor >10, and 62 studies were published in journal with an impact factor >5. However, there were only five studies published in the standard “CNS” journals and only four published in the top four medical journals, which suggests that most dyslexia researchers are more inclined to choose the most influential journals in their respective professional fields when submitting articles ( 30 ). This is in marked contrast with some other fields (e.g. vaccines), where the majority of top-cited articles are published in either the standard “CNS” journals or in the top four medical journals ( 15 ). Several other factors, such as the review turnaround time, likelihood of manuscript acceptance, publication costs, journal publication frequency, will all invariably also affect a researcher's journal selection ( 13 , 20 ).

According to the results of our analysis, nearly 80% of the 100 top-cited studies on dyslexia were published between 1990 and 2005, and the years of 2000 was found to have the most publications. The increase of landmark publications between 1990 and 2005 might reflect an increase in the interest in dyslexia research or that researchers had made some important scientific breakthroughs during this time period. All the top-cited studies on dyslexia were published in English, likely because English is the most commonly used language for knowledge dissemination in the world.

The top countries with regards to total citation count and number of papers in the top 100 list were the USA ( n = 53) and United Kingdom ( n = 21), which accounted for ~75% of the 100 top-cited studies. The USA published the most studies from the list, and this is probably because some of the world's top research centers are located in the USA and likely also the USA receives more research funding ( 31 ). Furthermore, the most prolific first-author (Shaywitz SE) and last-author (Shaywitz BA) were also from the USA. It is also worth mentioning that China had two studies on the top 100 list, which attests to the improvement of our national scientific research community with regards to knowledge dissemination.

In the present study, there were more original research articles ( n = 71) than review articles ( n = 28), but the latter had higher average citation counts per study. These results indicate that even though researchers pay significant attention to new findings on dyslexia, they regularly use information from review articles to convey relevant points in their own papers. We found that “Psychology” was the most frequent subject category associated with the top 100 articles, which indicates that researchers have been working to find effective treatments for people with dyslexia and that research in this field will continue to progress.

Like with other bibliometric analyses, there are some study limitations that should be highlighted. First, the 100 top-cited studies were extracted from the Web of Science Core Collection, which might have excluded some top-cited studies from other databases, such as Scopus and Google Scholar. Second, there was no citation data for recently published studies. Third, self-citations might have substantially influenced the results of the citation analysis. Moreover, this was a cross-sectional study, which implies that the identified 100 top-cited studies could change in the future. Despite these limitations, this descriptive bibliometric study could contribute new information about the scientific interest in dyslexia.

In conclusion, the present analysis is the first analysis to recognize the 100 top-cited studies in the field of dyslexia. This analysis provides a better understanding on dyslexia and may help doctors, researchers, and stakeholders to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of classic studies, new discoveries, and trends regarding this research field. As new data continue to emerge, this bibliometric analysis will become an important quantitative instrument to ascertain the overall direction of a given field, thus promoting ideas for future investigation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

YZ and HF designed the study. SZ and YZ acquired the data and performed statistical analyses. SZ, YZ, and HF drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the article and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was partly supported by National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Z2018B016).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714627/full#supplementary-material

1. Fortes IS Paula CS Oliveira MC Bordin IA de Jesus Mari J Rohde LA. A cross-sectional study to assess the prevalence of DSM-5 specific learning disorders in representative school samples from the second to sixth grade in Brazil. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2016) 25:195–207. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0708-2

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Landerl K, Moll K. Comorbidity of learning disorders: prevalence and familial transmission. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl. (2010) 51:287–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02164.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Castillo A, Gilger JW. Adult perceptions of children with dyslexia in the USA. Ann Dyslexia. (2018) 68:203–17. doi: 10.1007/s11881-018-0163-0

4. Peterson RL, Pennington BF. Developmental dyslexia. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. (2015) 11:283–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112842

5. Cavalli E, Colé P, Brèthes H, Lefevre E, Lascombe S, Velay JL. E-book reading hinders aspects of long-text comprehension for adults with dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia. (2019) 69:243–59. doi: 10.1007/s11881-019-00182-w

6. Wang LC, Liu D, Xu Z. Distinct effects of visual and auditory temporal processing training on reading and reading-related abilities in Chinese children with dyslexia. Ann Dyslexia. (2019) 69:166–85. doi: 10.1007/s11881-019-00176-8

7. Skeide MA, Kraft I, Müller B, Schaadt G, Neef NE, Brauer J, et al. NRSN1 associated grey matter volume of the visual word form area reveals dyslexia before school. Brain. (2016) 139:2792–803. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww153

8. Kraft I, Schreiber J, Cafiero R, Metere R, Schaadt G, Brauer J, et al. Predicting early signs of dyslexia at a preliterate age by combining behavioral assessment with structural MRI. NeuroImage. (2016) 143:378–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.09.004

9. Neef NE, Müller B, Liebig J, Schaadt G, Grigutsch M, Gunter TC, et al. Dyslexia risk gene relates to representation of sound in the auditory brainstem. Dev Cogn Neurosci. (2017) 24:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.01.008

10. Männel C, Meyer L, Wilcke A, Boltze J, Kirsten H, Friederici AD. Working-memory endophenotype and dyslexia-associated genetic variant predict dyslexia phenotype. Cortex. (2015) 71:291–305. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.06.029

11. Perazzo MF, Otoni ALC, Costa MS, Granville-Granville AF, Paiva SM, Martins-Júnior PA. The top 100 most-cited papers in paediatric dentistry journals: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Paediatr Dentist. (2019) 29:692–711. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12563

12. Daley EM, Vamos CA, Zimet GD, Rosberger Z, Thompson EL, Merrell L. The feminization of HPV: reversing gender biases in US human papillomavirus vaccine policy. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:983–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303122

13. Kolkailah AA, Fugar S, Vondee N, Hirji SA, Okoh AK, Ayoub A, et al. Bibliometric analysis of the top 100 most cited articles in the first 50 years of heart transplantation. Am J Cardiol. (2019) 123:175–86. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.09.010

14. Zhao X, Guo L, Lin Y, Wang H, Gu C, Zhao L, et al. The top 100 most cited scientific reports focused on diabetes research. Acta Diabetol. (2016) 53:13–26. doi: 10.1007/s00592-015-0813-1

15. Zhang Y, Quan L, Xiao B, Du L. The 100 top-cited studies on vaccine: a bibliometric analysis. Hum Vacc Immunother. (2019) 15:3024–31. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1614398

16. Beshyah WS, Beshyah SA. Bibliometric analysis of the literature on Ramadan fasting and diabetes in the past three decades (1989-2018). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2019) 151:313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.03.023

17. Adnan S, Ullah R. Top-cited articles in regenerative endodontics: a bibliometric analysis. J Endodontics. (2018) 44:1650–64. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.07.015

18. Gao Y, Shi S, Ma W, Chen J, Cai Y, Ge L, et al. Bibliometric analysis of global research on PD-1 and PD-L1 in the field of cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. (2019) 72:374–84. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.03.045

19. Yu T, Jiang Y, Gamber M, Ali G, Xu T, Sun W. Socioeconomic status and self-rated health in China: findings from a cross-sectional study. Medicine. (2019) 98:e14904. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014904

20. Yoon DY, Yun EJ, Ku YJ, Baek S, Lim KJ, Seo YL, et al. Citation classics in radiology journals: the 100 top-cited articles, 1945-2012. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2013) 201:471–81. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10489

21. Ziegler JC, Goswami U. Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages: a psycholinguistic grain size theory. Psychol Bull. (2005) 131:3–29. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.3

22. Vellutino FR, Fletcher JM, Snowling MJ, Scanlon DM. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): what have we learned in the past four decades? J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discipl. (2004) 45:2–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00305.x

23. Boder E. Developmental dyslexia: a diagnostic approach based on three atypical reading-spelling patterns. Dev Med Child Neurol. (1973) 15:663–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1973.tb05180.x

24. Norton ES, Wolf M. Rapid automatized naming (RAN) and reading fluency: implications for understanding and treatment of reading disabilities. Ann Rev Psychol. (2012) 63:427–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100431

25. Peterson RL, Pennington BF. Developmental dyslexia. Lancet. (2012) 379:1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60198-6

26. Van Noorden R, Maher B, Nuzzo R. The top 100 papers. Nature. (2014) 514:550–3. doi: 10.1038/514550a

27. Fardi A, Kodonas K, Gogos C, Economides N. Top-cited articles in endodontic journals. J Endodontics. (2011) 37:1183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.037

28. Gondivkar SM, Sarode SC, Gadbail AR, Gondivkar RS, Choudhary N, Patil S. Citation classics in cone beam computed tomography: the 100 top-cited articles. Int J Dentistry. (2018) 2018:9423281. doi: 10.1155/2018/9423281

29. Berlinberg A, Bilal J, Riaz IB, Kurtzman DJB. The 100 top-cited publications in psoriatic arthritis: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Dermatol. (2019) 58:1023–34. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14261

30. Bullock N, Ellul T, Bennett A, Steggall M, Brown G. The 100 most influential manuscripts in andrology: a bibliometric analysis. Basic Clin Androl. (2018) 28:15. doi: 10.1186/s12610-018-0080-4

31. Shadgan B, Roig M, Hajghanbari B, Reid WD. Top-cited articles in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabilit. (2010) 91:806–15. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.011

Keywords: dyslexia, bibliometric analysis, top-cited, citation analysis, citation

Citation: Zhang S, Fan H and Zhang Y (2021) The 100 Top-Cited Studies on Dyslexia Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 12:714627. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.714627

Received: 25 May 2021; Accepted: 28 June 2021; Published: 22 July 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Zhang, Fan and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Fan, fanhongfan@qq.com ; Yonggang Zhang, jebm_zhang@yahoo.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Dyslexia, Literacy Difficulties and the Self-Perceptions of Children and Young People: a Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 09 November 2019

- Volume 40 , pages 5595–5612, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rosa Gibby-Leversuch ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1695-877X 1 ,

- Brettany K. Hartwell 2 &

- Sarah Wright ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6500-370X 2

25k Accesses

25 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This systematic review investigates the links between literacy difficulties, dyslexia and the self-perceptions of children and young people (CYP). It builds on and updates Burden’s ( 2008 ) review and explores how the additional factors of attributional style and the dyslexia label may contribute to CYP’s self-perceptions. Nineteen papers are included and quality assessed. Quantitative papers measured the self-reported self-perceptions of CYP with literacy difficulties and/or dyslexia (LitD/D) and compared these with the CYP without LitD/D. Qualitative papers explored the lived experiences of CYP with LitD/D, including their self-views and how these were affected by receiving a dyslexia diagnosis. Results suggest that CYP with LitD/D may be at greater risk of developing negative self-perceptions of themselves as learners, but not of their overall self-worth. Factors found to be relevant in supporting positive self-perceptions include adaptive attributional styles, good relationships with peers and parents, and positive attitudes towards dyslexia and neurodiversity. In some cases, CYP with LitD/D felt that others perceived them as unintelligent or idle; for these CYP, a diagnosis led to more positive self-perceptions, as it provided an alternative picture of themselves. There is a need for further research to explore the impact of attributional style and the potential for intervention, as well as CYPs’ experiences of diagnosis and the associated advantages or disadvantages.

Similar content being viewed by others

What Norwegian Individuals Diagnosed with Dyslexia, Think and Feel About the Label “Dyslexia”

Dyslexia in the twenty-first century: a commentary on the IDA definition of dyslexia

Do we really need a new definition of dyslexia a commentary, explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A broad field of dyslexia research exists, some of which has focused on the social and emotional aspects of dyslexia, specifically self-perceptions. Research in this area has revealed mixed findings: some papers indicate that dyslexia is linked with experiences of stigmatisation and lowered self-concept (e.g. Polychroni et al. 2006 ; Riddick 2000 ) whereas others find that dyslexia is not associated with negative self-perceptions (e.g. Burden and Burdett 2005 ) or that the labelling of dyslexia can increase self-esteem (e.g. Gibson and Kendall 2010 ; Solvang 2007 ). Some of the differences in findings can certainly be attributed to the array of definitions and measurement tools used, with some papers conflating self-esteem and self-concept.

Two reviews have looked specifically at LitD/D and self-perceptions: Chapman and Tunmer ( 2003 ) and Burden ( 2008 ). Chapman and Tunmer found that reading self-perceptions develop in response to actual reading performance as early as the first year of school. Burden found that while academic self-concept tended to be lower in CYP with dyslexia, compared to typically achieving peers, this did not necessarily impact on self-esteem. His paper is highly relevant to the current review, however, the majority of papers included were written prior to 2000. Both review papers suggested that attributional style may be an important factor in developing self-perceptions and should be further researched.

This review extends Chapman and Tunmer’s ( 2003 ) and Burden’s ( 2008 ) reviews by looking at literature in the 10 years since, by operationalising self-perception terms and considering the impact of differing definitions of dyslexia. This review imposes definitions on a dataset that uses multiple definitions and terms relating to self-perceptions, one of the weaknesses of the previous literature that was highlighted by Burden’s review.

In addition, this review will evaluate the research within the context of current systems of education and dyslexia assessment, including considering some of the pertinent issues that were not explored in previous reviews: looking beyond within-child factors by exploring the impact of the CYP’s educational setting on their self-perceptions. It has been suggested that there are differences in the self-perceptions of CYP educated in specialist compared to mainstream settings (e.g. Tracey and Marsh 2000 ). Furthermore, researchers have questioned whether the label itself may influence experiences, beliefs and self-perceptions (e.g. Riddick 2000 ) so this is also considered.

Definitions

Definitional confusions have been key to the mixed findings in this area of research and will be addressed in this first section.

Despite the reported prevalence of dyslexia, the diagnostic term itself is not consistently defined in professional, research or social domains (Solvang 2007 ). A wide range of associated terms are also used within Europe (e.g. ‘specific learning disability’ ‘literacy difficulties’) without clear distinction or agreement on what they mean (Elliott and Grigorenko 2014 ). Educational Psychologists (EPs) in Britain often use the BPS definition (British Psychological Society 2005 ):

‘Dyslexia is evident when accurate and fluent word reading and/or spelling develops very incompletely or with great difficulty. This focuses on literacy learning at the ‘word level’ and implies that the problem is severe and persistent despite appropriate learning opportunities. It provides the basis for a staged process of assessment through teaching.’ (p.11).

This definition clearly highlights the importance of appropriate teaching and that dyslexia cannot be a result of inadequate teaching, but is evident when difficulties persist in spite of good teaching. The definition does not make a distinction between dyslexia and other forms of literacy difficulties, or provide a cut-off for what should be considered ‘severe and persistent’. An alternative is the discrepancy definition, which defines dyslexia as reading at a level significantly below what would be expected based on predictions from intelligence scores (Siegel 1992 ). However, this has been largely discredited as it only identifies a certain subset of individuals and lacks empirical validity (Elliott and Grigorenko 2014 ; Snowling 2013 ; Tanaka et al. 2011 ). Despite this, it continues to be used in research (e.g. Novita 2016 ) and perpetuated by organisations such as The International Dyslexia Association (‘Definition of Dyslexia’, n.d.).

For the purposes of this review, the terms dyslexia and literacy difficulties will both be used, but not to imply that they are necessarily distinguishable, only that, in one case, a diagnosis has been given and in another, it has not. In reviewing the research, the terminology used will reflect the paper being discussed. The term ‘literacy difficulties and/or dyslexia’ (LitD/D) will be used to speak generally about children and young people (CYP) who have difficulties with literacy, diagnosed or not.

Self-esteem, self-concept and self-efficacy have been explored by researchers looking at similar constructs, but are not always appropriately defined. As Marsh ( 1990a , 1990b ) pointed out: ‘Self-concept, like many other psychological constructs, suffers in that ‘everybody knows what it is,’ so that researchers do not feel compelled to provide any theoretical definition of what they are measuring’ (p. 79). In order to review and discuss the included papers, the different terminologies are operationalised in Table 1 .

The Current Review

This review investigates the links between literacy difficulties, dyslexia and the self-perceptions of CYP, highlighting their voices and experiences. Five research questions were addressed. The first two aim to update Burden’s ( 2008 ) review and the following three offer novel contributions to a review of this field:

What is the impact of LitD/D on global self-perceptions?

What is the impact of LitD/D on domain-specific self-perceptions?

Does the type of educational setting that a child attends impact on self-perceptions?

How are attributional styles linked with self-perceptions amongst CYP with LitD/D?

Does the dyslexia label influence self-perceptions?

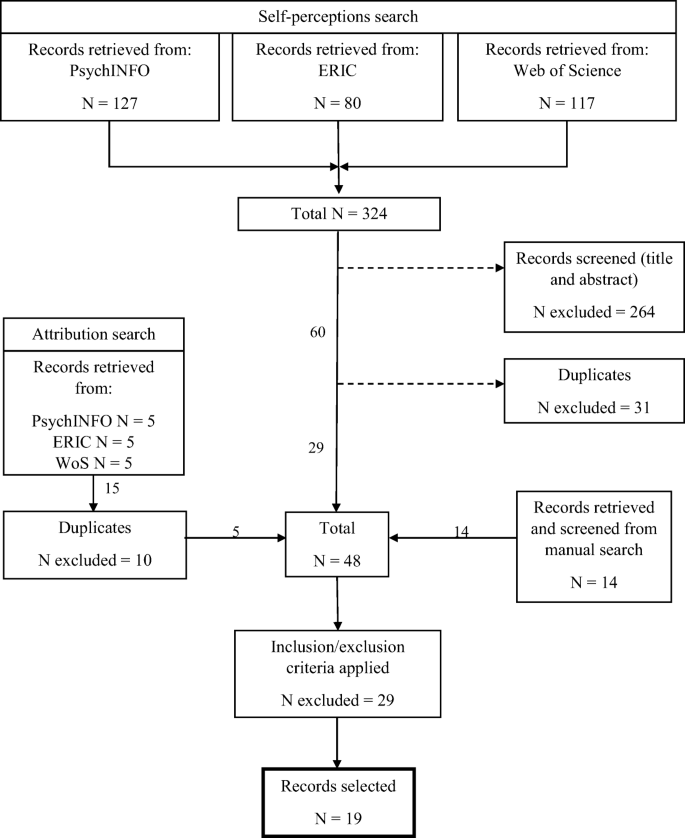

Search Strategy

The papers included in this review were sourced via systematic searching and a manual search of relevant papers (Fig. 1 ). The systematic searches were conducted within three electronic databases: PsychINFO, Web of Science (WoS) and ERIC. Search terms relating to dyslexia, self-perception and attribution were generated based on reading of known papers on these topics (Table 2 ). The databases were searched for papers with titles containing dyslexia AND self-perception terms, then dyslexia AND attribution terms. Only papers published in the English language, between 2000 and 2017, in academic journals were retrieved.

Paper identification and screening process

Additional papers were identified through manual searches, including searching two relevant review articles (Burden 2008 ; Chapman and Tunmer 2003 ). The two review papers themselves were excluded as the majority of papers cited were written prior to the year 2000.

Once papers from the self-perceptions, attributions and manual searches were complete and screened, 48 papers remained, at this point, all of the pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied (Table 3 ). The papers in this review were restricted to studies conducted in Europe due to differences in diagnosis in other parts of the world.

The initial systematic search was conducted on 08-09-2017 and the search for papers including attribution terms was conducted on 13-10-2017 (Table 4 ).

Selected Papers

Data extraction.

The 19 selected papers were reviewed systematically and data were extracted relating to authors, year and country, sample characteristics, design and methods, measures and inclusion criteria, and main relevant findings. The extracted data is detailed in Table 7 .

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of the qualitative papers was completed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme 2017 ). The CASP Checklist was adapted to include two additional criteria relevant to the review question.

Quantitative studies were assessed using a checklist created by the author, based on two well-used checklists; the Downs and Black Checklist (Downs and Black 1998 ) and the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute 2014 ). A new quantitative checklist was created to ensure that it included questions most appropriate to the cross-sectional methodologies of the included studies, as well as the addition of further items designed specifically to answer the review question. Tables 5 and 6 give the outcome of the quality assessment for each paper (Table 7 ).

The contribution of each individual paper has been considered and assessed for quality. Based on the results of the quality assessment (Tables 5 and 6 ), the authors afford more emphasis and weight to reporting and analysing the findings of higher quality studies.

Qualitative Papers

The majority of papers used individual semi-structured interviews, which allowed researchers to uncover the priorities of participants and be flexible in the topics discussed, meaning that the researcher reduced the impact of their own beliefs and expectations of the research and gathered rich data. However, only two of the studies provided their interview schedules (Gibson and Kendall 2010 ; Glazzard 2010 ), which reduced transparency and replicability.

As a dataset, there were a number of weaknesses. No papers adequately considered the researcher-participant relationship nor reflected on the researcher’s role in data collection and analysis. As many of the participants were children, considering the balance of power and influence of the researcher as an adult is important.

Further weaknesses were apparent in the reporting of procedures and data analysis. Five studies did not provide sufficient description of their data analysis. However, Casserly ( 2013 ) and Singer ( 2005 ) gave detailed descriptions of the frameworks used and the process of coding and drawing out themes. Singer ( 2005 ) also transposed coded data into a numerical system and determined interrater reliability.

Three papers (Burton 2004 ; Casserly 2013 ; Humphrey and Mullins 2002b ) gave adequate consideration to their use of self-perception terms. Armstrong and Humphrey ( 2009 ) looked at individuals’ conception of the self and identity, incorporating a range of self-perceptions, although no definitions were provided. Four papers (Gibson and Kendall 2010 ; Glazzard 2010 ; Singer 2005 ; Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou 2009 ) discussed self-esteem without providing any definition. Glazzard, and Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou used a number of self-perception terms interchangeably without explanation.

Six of the eight studies scored >6 out of 12 and all studies were deemed to make a valuable contribution to their area of research and to the review question.

Quantitative Papers

Ten out of 13 papers clearly described the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation although fewer provided sufficient information on recruitment procedures. Sample sizes ranged from 19 to 242, with some studies analysing data from large comparison groups and others only including CYP with LitD/D.

A wide range of outcome measures were utilised and all papers clearly described these. Five papers gave insufficient evidence to demonstrate the accuracy, validity and reliability of their outcome measures. One of these (Saday Duman et al. 2017 ), used a measure of self-concept (The Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale) that has been criticised by previous researchers for using a composite measure of global self-concept (Bear et al. 2002 ).

The self-perception measures used were almost entirely self-report by CYP. Given that participants in every study had literacy difficulties, any self-report measures needed to be appropriately administered, either orally or with consideration of reading level. However, only three papers (Burden and Burdett 2005 ; Frederickson and Jacobs 2001 ; Lindeblad et al. 2016 ) acknowledged this and reported steps taken to address the issue.

A strength of the dataset is that 10 of the 13 studies provided definitions of their self-perception terms and used them consistently and accurately. In addition to providing definitions, several papers discussed the importance of terminology in detail. However, this was still a weakness in some papers (Polychroni et al. 2006 ; Saday Duman et al. 2017 ; Terras et al. 2009 ).

Burton’s ( 2004 ) intervention study provided a clear and replicable description of the intervention that was carried out, however Saday Duman et al.’s ( 2017 ) intervention was insufficiently described.

On the whole, the quantitative studies provided valuable information to the review question and scored well in terms of quality, with all but 3 studies scoring ≥8 out of 16.

Findings from Papers

The results of the review are discussed in terms of the five research questions.

What is the Impact of LitD/D on Global Self-Perceptions (GSP)?

Seven papers utilised quantitative measures of self-esteem or self-worth, including two papers from Burden’s ( 2008 ) review. In order for useful comparison and conclusions to be made, only measures that fit with the definitions of this review were included.

When drawing conclusions, the results of quality assessment should be considered. The three studies that found no difference in GSP amongst CYP with LitD/D (Frederickson and Jacobs 2001 ; Lindeblad et al. 2016 ; Terras et al. 2009 ) were high and medium scoring papers, whereas the three papers that did detect a difference (Alexander-Passe 2006 ; Humphrey and Mullins 2002b ; Saday Duman et al. 2017 ) were all low scoring. This suggests, especially if taken in conjunction with the findings from Burden’s 2008 review, that LitD/D are not directly linked with lowered GSP in any consistent or predictable way. Two papers suggest that task-based coping styles may be a protective factor in preventing difficulties in specific areas from impacting on overall sense of self-worth (Alexander-Passe 2006 ; Singer 2005 ). Other influencing factors will be considered throughout this review.

Across the seven studies discussed, six different GSP measures were used; both Frederickson and Jacobs ( 2001 ) and Terras et al. ( 2009 ) used the Self-Perception Profile for Children (Harter 1985 ) and found no differences in GSP for CYP with LitD/D. The measures used in some studies appeared to have greater construct validity than others, with the Self-Perception Profile’s self-worth scale fitting well with the definition used for this review.

Two of the seven papers reported cross-sectional studies that assessed GSP in groups of children with and without dyslexia. Frederickson and Jacobs ( 2001 ) found no significant differences between scores in each group on their self-worth subscale. However, Humphrey and Mullins ( 2002b ) reported significantly lower global self-concept amongst CYP with dyslexia in mainstream schools, compared with a control group, although not amongst CYP with dyslexia attending specialist provision. However, Humphrey and Mullins’ ( 2002b ) findings are treated with caution as the ‘total self’ scale of the SDQ (Marsh 1990b ) includes accrued scores from responses to domain-specific statements. As GSP is its own distinct aspect of self-perception, it should not be a composite of domain-specific items (Mruk 2006 ). An individual may have low self-perceptions in a specific domain but still view themselves highly in terms of overall self-worth.

Three of the studies assessed GSP by comparing participants with dyslexia to previously gathered data. Terras et al. ( 2009 ) and Lindeblad et al. ( 2016 ) found no discrepancy between participants’ self-reported self-esteem and norm-referenced data, using two different GSP measures. Terras et al.’s findings were also corroborated by parent reports.

Alexander-Passe ( 2006 ) did find differences between 19 adolescent participants with dyslexia and norm-referenced data for self-esteem, depression and coping style. The participants reported below-expected self-esteem; however, this was accounted for entirely by the female participants. The difference in self-esteem and gender seemed to be explained by differences in coping styles: the female participants used more emotion-based coping styles (internalising or externalising behaviours), whereas the male participants used task-based coping (being proactive and persistent), which has previously been associated with more effective coping. Similar effects around coping style were found in Singer’s ( 2005 ) qualitative study: task-based coping methods were found to effectively protect self-esteem.

In Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou’s ( 2009 ) qualitative research, 9 out of 16 university students reported low self-esteem related to their dyslexia. The remaining seven students did not feel dyslexia affected their self-esteem. Clearly, these are mixed findings in terms of the link between LitD/D and self-worth; individual differences in coping style (emotion-based vs. task-based) may be one factor influencing this link.

Two intervention studies aimed to increase the self-perceptions of CYP with dyslexia; one by directly targeting self-perception (Burton 2004 ) and the other through literacy intervention (Saday Duman et al. 2017 ). Both of these studies reported some positive findings, but both were rated as being of low quality. No real conclusions can be drawn from these two intervention studies; however, further research of this nature could be extremely useful in determining causal links between LitD/D and self-perceptions.

What is the Impact of LitD/D on Domain-Specific Self-Perceptions?

Ten papers used self-perception measures related to specific domains. The most commonly assessed domain was academic self-concept: beliefs about the self in terms of academic performance. These scales had various names (e.g. perceived scholastic competence, school-based self-esteem) but related to the same construct. Generally, research suggests that individuals with dyslexia are less likely than their peers to develop positive self-perceptions in certain domains. These domains relate directly to the difficulties that are typically experienced by CYP with LitD/D: reading, writing and school achievement. Preliminary findings also suggest that CYP with dyslexia may hold lower self-perceptions than CYP who are reading at the same level, but do not have a dyslexia diagnosis (Frederickson and Jacobs 2001 ). Although there appears to be a risk factor associated with LitD/D, an individual’s environment, as well as their personal characteristics and social support, seem to also play an important role.

Many papers utilised other subscales in addition to those relating to academic self-perceptions. Commonly, self-perceptions relating to social/peer acceptance, physical appearance/performance and behaviour were assessed. Findings were mixed, but available evidence suggests that LitD/D is not linked with differences in these other domains.

Novita ( 2016 ) found that children with dyslexia reported significantly lower school-based self-esteem than a control group, with a weak-medium effect size. Similar findings were reported by Alexander-Passe ( 2006 ), Saday Duman et al. ( 2017 ) and Frederickson and Jacobs ( 2001 ), and by Terras et al. ( 2009 ) who compared their participants with dyslexia to norm-referenced data and found significantly poorer perceptions of scholastic competence as rated by children and their parents.

Terras et al. also found that when parents held positive attitudes towards dyslexia and had a good understanding of their child’s difficulties, their children had higher self-esteem. The authors concluded that children’s close relationships, social support and knowledge about their difficulties contributed to psycho-social adjustment and positive self-image.

Five qualitative studies also found that social and family support were integral to coping with dyslexia and maintaining self-esteem (Armstrong and Humphrey 2009 ; Gibson and Kendall 2010 ; Glazzard 2010 ; Singer 2005 ; Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou 2009 ). Singer found that children whose parents responded more negatively to their emotions about dyslexia were more likely to experience shame, hide their feelings and develop internalising coping styles; they emphasised their powerlessness as a method of protecting self-esteem. Other children demonstrated externalising behaviours that aimed to conceal their feelings of shame or guilt; these children were also less likely to share feelings with parents. On the other hand, children who described their parents as academically and emotionally supportive showed greater desire for self-improvement and experienced fewer negative emotions. Being able to safely discuss feelings with parents seems to be a protective factor in developing more positive self-perceptions and coping styles.

Frederickson and Jacobs ( 2001 ) and Polychroni et al. ( 2006 ) additionally looked at the impact of actual academic performance amongst children with dyslexia and their peers. Frederickson and Jacobs administered word reading tests and used this data to evaluate self-perceptions whilst controlling for actual reading performance. The children with dyslexia were found to be more likely to hold negative self-perceptions of their scholastic competence, even when compared to peers reading with the same level of accuracy, but without dyslexia.

Polychroni et al. ( 2006 ) compared children with dyslexia separately to high and low achieving peers. The children with dyslexia reported significantly more negative self-concepts regarding penmanship/neatness, arithmetic and school satisfaction, when compared with both high and low achieving peers without dyslexia, and regarding reading/spelling and general ability compared to the high achieving peers only. Unfortunately, the authors do not provide information that makes it possible to compare the achievement levels of the different groups; therefore, it is unclear whether the children with dyslexia had comparable achievement to either of the other groups.

Humphrey and Mullins ( 2002b ) was a low quality paper that reported mixed findings, but highlighted slightly lower than average school-based self-concept for children with dyslexia in mainstream schools. In Humphrey’s other paper (Humphrey 2002 ), he used an alternative method of measuring self-perceptions, known as the ‘semantic differential method’ (p.31). This measure reflects the difference between a person’s current self-concept and their ideal self in relation to a number of different constructs, providing the evaluative element of self-esteem. Using this method, Humphrey ( 2002 ) found that, in comparison to children with no learning difficulties, a sample of children with dyslexia in mainstream schools demonstrated significantly lower self-perceptions in the domains of reading, writing, spelling, intelligence, English ability, popularity and importance, but not maths or being hardworking.

A Swedish study (Lindeblad et al. 2016 ), looked at literacy related self-efficacy through a questionnaire designed to assess participants’ beliefs about how they would perform on a specific task (e.g. ‘I can read an email from a friend’) (p.456). Based on standardised literacy assessment, the participants were not performing at the level typically expected, but the GSP of these children had not been negatively impacted. The results of the self-efficacy assessment indicated that the majority of participants felt confident to manage their school work and perceived few, or very few, limitations in their literacy ability. Although this is in contrast with their actual performance, the authors linked the positive self-attitudes of these participants with broader changes in the country towards inclusive schooling and improved attitudes and understanding of dyslexia, perhaps leading students to make fewer peer comparisons and focus more on their own progress.

Does the Type of Educational Setting that a Child Attends Impact Self-Perceptions?

One qualitative and one quantitative study specifically explored the impact of mainstream versus specialist educational settings on the self-perceptions of CYP with dyslexia. There is very little research to be drawn upon to make conclusions about the impacts of different educational settings. However, by comparing mainstream and special settings, Casserly ( 2013 ) provides some useful insight into the factors that were beneficial in terms of improving the self-perceptions of CYP with dyslexia. Given the limited research available, this would be a key area for future explorations.

Humphrey’s research (Humphrey 2002 ; Humphrey and Mullins 2002b ) used two self-report methods and a teacher-report method; the semantic differential method and the questionnaire indicated that CYP with dyslexia in mainstream education held the most negative self-perceptions, whereas CYP in specialist provision held self-perceptions only marginally lower than the control group. However, teacher reports, measuring behavioural manifestations of self-esteem, showed the highest level of maladaptive behaviours to occur in the specialist setting, which both contradicts, and calls in to question the validity of the findings. Humphrey’s qualitative data (Humphrey and Mullins 2002b ) also revealed some themes that seemed to contradict the quantitative findings, with more CYP in the specialist setting than the mainstream setting reporting feeling ‘less intelligent than their peers’ (p.5).

Casserly ( 2013 ) followed 20 participants over four years, during which time all participants moved from mainstream to a specialist dyslexia setting and then back to mainstream. Through interviews with children, their parents and teachers, Casserly found that children generally had low reading self-concept and self-esteem upon entry to their specialist setting, which was increased through the targeted support that they received in their specialist setting and remained good after their return to mainstream.

When asked what they thought had improved their children’s self-perceptions, parents cited the benefits of increased praise and encouragement, teachers’ belief in their child’s ability, making academic progress, positive relationships, and peers with similar difficulties that they could relate to. The teachers reported a long list of strategies and approaches that they felt supported children’s self-perceptions, including teaching them about learning differences, promoting positive attitudes towards literacy and highlighting their strengths. They also cited smaller classes, with more individual attention as well as the benefits of being able to make more favourable peer comparisons.

Casserly discussed social comparison theory as a possible reason for improvements in self-esteem within the specialist settings. However, although social comparisons were mentioned by participants, it could be argued that this ignores the many strategies that were also put in place to support these children in their learning and wellbeing. Self-esteem remained high once they had left the provision and spent a year in mainstream class, even though they still reported finding things more difficult than other children. It may be the case that, due to the specialist provision, the children developed resilience that protected their self-esteem, suggesting that intervention in this area may be useful.

How are Attributional Styles Linked with Self-Perceptions Amongst CYP with LitD/D?

Four quantitative papers measured the attributional styles of CYP with LitD/D and one examined goal orientations, which link with attributions. Four out of five of these studies indicated that children with dyslexia are more likely to make attributions for success and failure that are outside of their control, meaning they have attributional styles that are associated with lower achievement, more negative self-perceptions and less effective approaches to learning. However, this is not always the case and research showed that with the right environment and support, children with dyslexia will make more adaptive attributions, linked to improvements in both performance and self-perceptions (Burden and Burdett 2005 ). Two qualitative papers also showed that some individuals developed a strong sense of determination associated with their dyslexia and adaptive attributional styles. However, Singer ( 2005 ) found that these children were in the minority. At this stage, the causal links are unclear; research into the impact of attribution retraining programmes on the performance and self-perceptions of CYP with dyslexia will help to shed light on this.

Humphrey looked specifically at the attributional styles of CYP with and without dyslexia (Humphrey and Mullins 2002a ) by asking CYP to rank order possible reasons for success or failure in fictional test scenarios. In success scenarios, participants with dyslexia were more likely to attribute their achievement to teacher quality (an external factor) than the children without dyslexia. This was seen as potentially detrimental by the authors, as children would not receive positive self-referential information as a result of their success (p.201). However, the authors were comparing the second most commonly cited reason for success, when, in fact, the most commonly cited reason given by both groups was effort.

In failure scenarios, the control group felt that lack of effort, followed by the difficulty of the test, would be the most likely causes, suggesting a belief that they could succeed on a difficult test in the future if they applied more effort. However, the children with dyslexia cited difficulty of the subject, followed by difficulty of the test as the most likely reasons for failure. As both of these things are outside of the individual’s control, this might imply that they could not control whether they succeeded on a difficult test in the future.

In Pasta et al.’s ( 2013 ) study, the attributional styles of children with SpLD also tended to reflect more emphasis on external, uncontrollable factors such as luck and task difficulty than their equally and higher achieving classmates. Teachers perceived children with SpLD as more dependent than their peers, including those with matched achievement. The authors suggested that this reflects the children’s external LoC and indicates that the children with SpLD underestimated their potential as independent learners.

Correlations between attributional style and test performance showed that the more pupils attributed results to effort (internal LoC), the better they performed and the more pupils attributed results to task difficulty (external LoC), the worse they performed. Emphasising the importance of effort is seen as an adaptive attributional style as it is within the control of the individual and is not fixed. Although the children with SpLD generally had less adaptive attributional styles, those who did have more adaptive styles achieved more highly. This could be an important area for intervention.

In Gibson and Kendall’s ( 2010 ) qualitative research, participants expressed a range of attributional styles relating to their success in school. One participant conveyed feelings of determination to do well in the face of others’ beliefs that they could not overcome their difficulties. Other participants demonstrated resignation at being assigned to lower sets that were perceived as being for less intelligent students. These participants seemed to have their sense of control stripped from them by an educational system that wanted to categorise and restrict them.

Burden and Burdett ( 2005 ) provided valuable insight into the nature of attributional styles amongst CYP with dyslexia by looking at a context in which students with dyslexia were thriving. Questionnaire responses revealed that the majority of students did not demonstrate learned helplessness or perceive themselves as being held back by their dyslexia. These successful pupils believed that effort is essential for success and would enable them to achieve their goals, suggesting strong internal LoC. Responses to certain items indicated that their internal LoC may be a protective factor for good self-esteem. Burden and Burdett concluded that whole-school promotion of personal responsibility and self-worth is essential for producing learners with a positive sense of self.

In Singer’s ( 2005 ) study, 16% of all participants were characterised as having adaptive approaches to protecting their self-esteem, including desire for self-improvement. These children emphasised the importance of effort and belief in their ability to improve, and maintained high levels of self-esteem. Compared with the others in the study, these children showed signs of having developed adaptive attributional styles.

Frederickson and Jacobs ( 2001 ) provided further evidence, finding that children with dyslexia were significantly more likely to make uncontrollable attributions than their peers and that uncontrollable attributions were associated with lower reading scores. Furthermore, children making uncontrollable attributions had significantly lower perceived scholastic competence than those who showed controllable attributions, even after controlling for actual reading accuracy. This was the case for both the children with and without dyslexia. The authors suggested a need for research evaluating the impact of attribution retraining programmes to further explore the causal relationships and practical implications of this research. They also suggested a link with learners’ goal orientations and the effects of learning vs. performance goals on self-perceptions amongst learners with dyslexia.

Goal orientations were explored by Polychroni et al. ( 2006 ): ‘surface’ approaches to learning are characterised by the intention to reproduce learned material for the sake of performance (performance orientation), and a ‘deep’ approaches to learning are characterised by an internal desire to seek meaning (learning orientation) (p.418). In this study, both the children with dyslexia and the children with matched achievement but no dyslexia, reported significantly higher levels of surface approaches than the higher achieving children. Amongst children with dyslexia, there were correlations between having a surface approach and having lower academic self-concept, suggesting that a deep approach to learning could be a protective factor against lowered self-perceptions, as well as being associated with more enjoyment, intrinsic motivation and greater achievement (Watkins 2010 ), making this a potential area for intervention.

Does the Dyslexia Label Influence Self-Perceptions?

Four qualitative papers explored the impact of receiving a diagnosis of dyslexia for their participants. Three of these were thematic analysis studies (Gibson and Kendall 2010 ; Glazzard 2010 ; Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou 2009 ), all of which reported themes relating to labelling. The studies included a total of 29 participants between the ages of 14 and 26 attending school or university. Mixed results suggest that reactions to receiving a dyslexia label are individual and can be conceptualised as lying on a continuum from resistance to accommodation. A number of factors seem to influence where one may lie on this continuum; individuals who were labelled for the first time in late adolescence perceived dyslexia as stigmatising, did not feel they needed help, did not perceive the label as informative or supportive, and were more likely to resist the label. On the other hand, those who felt they had already been labelled with negative terms such as ‘lazy’, the label of dyslexia was a welcome alternative, providing a boost to their self-esteem.

In each study, references were made to the negative consequences of not having a recognised diagnosis; Gibson and Kendall described feelings of school failure amongst their participants, as well as lack of appropriate support and, in some cases, very negative attitudes and low expectations from teachers. Glazzard reported that having a diagnosis of dyslexia and owning that label was essential for creating a positive self-image amongst participants. Glazzard noted feelings of increased self-esteem once the diagnosis had been made, partly because it enabled them to explain their difficulties to themselves and others. This is mirrored by a quote from Gibson and Kendall’s research from a participant who said ‘ I didn’t know what it was, I thought I was thick .’ (p.192) indicating that the diagnosis of dyslexia relieved these feelings.

Amongst Greek participants (Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou 2009 ), there were similar stories of not understanding difficulties prior to diagnosis and 9/16 participants reported having had low self-esteem. For most participants, diagnosis was associated with feelings of relief and increased understanding. However, some felt it was not helpful as it did not give useful information.

In all of the qualitative studies, references were made to alternative labels to dyslexia. Primarily, these included ‘thick’ ‘lazy’ or ‘stupid’. Many participants spoke about applying these labels to themselves, or having them applied by others who did not know about, or understand, their dyslexia. Some participants felt that their label changed others’ perceptions (Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou 2009 ) and Glazzard ( 2010 ) alluded to the dyslexia label replacing these negative judgements and boosting participants’ perceptions of their own intelligence. In Singer’s ( 2005 ) study, children who tended to internalise their emotions of guilt or shame found that emphasising their label, and taking responsibility away from themselves, helped to protect their self-esteem. Negative comments from other people generally made participants feel bad about themselves, although, in one case, low expectations and negative attitudes from teachers added to a participant’s determination to succeed (Gibson and Kendall 2010 ).

The study by Armstrong and Humphrey ( 2009 ) was designed specifically to look at college students’ reactions to diagnosis. Using grounded theory, the authors developed a model of psychological reactions to diagnosis conceptualised on a continuum from resistance to accommodation. Resistance is characterised by not accepting dyslexia as part of the self and holding negative connotations of dyslexia, whereas accommodation involves integrating dyslexia into the notion of self and recognising both positive and negative aspects. The amount of resistance or accommodation displayed by individuals clearly stemmed in part from their perception of dyslexia: those who felt dyslexia was equal to stupidity were less likely to accept it into their notion of self, as this would damage self-perceptions. The authors suggested that individuals diagnosed later in life may require additional psychological support to accommodate their diagnosis, as participants who had been described as having dyslexia at a younger age seemed more willing to accommodate it.

Individuals who accommodated dyslexia were more likely to be motivated and successful in their studies, take up support, and adjust to their difficulties. Failure to accommodate, however, was suggested as a risk factor for increased negative self-views, use of self-defeating strategies, lowered self-esteem and negative emotions.

This paper addressed five research questions; the first two concerned the evidence base around the impact of LitD/D on both global and domain-specific self-perceptions. Consistent with findings from an earlier review (Burden 2008 ), evidence suggests that CYP with LitD/D are very aware of their specific difficulties and may experience negative self-perceptions relating to their academic competence and literacy skills. However, these domain-specific self-perceptions do not appear to have a consistent impact on overall self-worth; evidence suggests that CYP with LitD/D do not hold less positive global self-perceptions than their peers. Protective factors that contribute to maintaining positive self-worth include supportive family, teacher and peer relationships, and recognition of their successes in other areas.

The third research question addressed attributional style. Current evidence suggests that CYP with dyslexia are at greater risk of developing maladaptive attributional styles, based on an external LoC. However, those who emphasise the importance of their own effort in their achievement are more likely to succeed academically and to hold positive self-concepts. This suggests a link between maladaptive attributional styles, lower self-perceptions, and poorer performance amongst CYP with dyslexia, making this a potentially important area for intervention and support. Although the causal links amongst CYP with LitD/D are not yet clear, researchers have suggested that in the general population maladaptive attributions lead to lowered self-esteem, which impacts motivation and consequently academic performance (Chodkiewicz and Boyle 2014 ). Therefore, it may be the case that attribution retraining programmes could have a positive impact on both self-perceptions and performance amongst CYP with LitD/D. Preliminary evidence suggests that more adaptive attributional styles develop in the context of supportive and accepting environments in which CYP can experience success, however, more evidence around this is needed, along with research looking at the effects of attribution retraining interventions.

The fourth research question explored the impact of different educational settings for CYP with LitD/D. In this area, there were only a small number of research studies to review and more research is needed to draw conclusions about differences in the self-perceptions of those attending mainstream versus specialist settings. However, initial findings from one qualitative study have shed some light on the features of educational settings that may support CYP to hold positive self-perceptions. CYP with LitD/D and, arguably, all CYP, may benefit from settings that provide nurturing and acceptance, which support their students to understand dyslexia and provide high quality differentiated teaching. These approaches may contribute to more positive self-perceptions amongst pupils and the development of resilient learners. Findings from this review suggest that CYP with dyslexia thrive when they are accepted and their needs are understood, something that is not unique to any one setting, or to those with dyslexia.

The final research question addressed the potential impact of labelling on the self-perceptions of CYP with LitD/D. Frederickson and Jacobs ( 2001 ) found that children with literacy difficulties, but no dyslexia diagnosis, did not experience the same negative impact on self-perceptions. It may be that having attention drawn to one’s literacy difficulties (through diagnosis) increases the likelihood of a negative effect on self-perceptions. However, qualitative research sheds a different light on experiences of receiving a diagnosis. Individual reactions to diagnosis vary and may lie on a continuum between resistance and accommodation of the label (Armstrong and Humphrey 2009 ). Many CYP reported having been labelled, prior to their diagnosis, as ‘lazy’ or ‘stupid’ and felt that their label of dyslexia counteracted this experience. For others, the label was perceived as stigmatising and unhelpful. Given the mixed nature of these findings, there is a need for further research, carried out with CYP currently in education, to explore the subtle differences in how individuals with LitD/D respond to a label of dyslexia and their own perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of this label.

When considered as a whole, the findings from this data set illuminate some key factors that may be influential for CYP with LitD/D, whilst also revealing gaps in our current understanding and raising some interesting and important questions. It appears that CYP benefit from LitD/D being identified, recognised and explicitly supported in terms of having a positive overall sense of self. The findings also strongly suggest that it is particularly helpful for CYP when parental, cultural and school attitudes towards LitD/D are understanding and help to cultivate a sense of personal responsibility, high expectations and self-worth. What is not yet known is whether the type of label used to recognise the LitD/D makes any difference, whether there are any gender differences to account for, how much variation there is in individual CYP’s resistance or accommodation of the label, and whether social comparison factors, or being placed in a special education group for LitD/D, has a significant impact.

The overall findings also suggest that the good overall self-concept associated with having widely-recognised and explicitly labelled LitD/D may be a ‘trade off’ that occurs at the expense of declines in CYP’s academic self-concept and a tendency to make unhelpful external attributions, when learning. The relief obtained from the difficulty not being construed as negatively (or from others taking a more tolerant and supportive approach) seems offset by CYP’s sense that their LitD/D is beyond personal control and they have less academic potential than peers. Whether it is possible to effectively support CYP with LitD/D to reduce any external attributions through intervention is, as yet, unclear.

Interesting and important questions raised by these mixed overall findings include whether CYP with LitD/D are a sufficiently homogenous group to allow us to draw generalisable conclusions, whether the support and encouragement from the culture and context are more important factors in determining positive global and domain specific self-perceptions than having an identified LitD/D label and, finally whether the benefit in having a positive overall self-concept outweighs the risk and detrimental effects that may come as a result of having a low academic self-concept and a less adaptive attribution style.

Implications

Mixed findings relating to the impact of the dyslexia label indicate that psychologists, dyslexia specialists, and school staff should continue to treat every student as an individual and exercise caution in terms of using the dyslexia label, considering, alongside the child, whether the label is justified and useful to the individual. Furthermore, it is important that an accessible and accurate explanation of any LitD/D is given, dispelling any pre-existing stigmatising or negative connotations that the child may have.

The evidence of the role of attributional style in the development of self-perceptions amongst CYP with LitD/D is emerging, but currently limited. However, there is evidence that teaching CYP about attributions can be beneficial for their achievement and motivation (e.g. Blackwell et al. 2007 ) and this is something that should be further explored amongst a sample of CYP with LitD/D.

Preliminary evidence from two intervention studies suggests that interventions targeting both self-perceptions and literacy skills can be beneficial for CYP with LitD/D. One such intervention, which is readily available to schools, is Precision Teaching (Lindsley 1995 ). Recent research suggests that Precision Teaching can have motivational benefits and increase self-esteem, as well as being highly effective for teaching literacy skills (Griffin and Murtagh 2015 ).

Self-efficacy is more malleable and less stable over time than self-concept or self-esteem; furthermore, it can be seen as an active precursor to self-concept (Bong and Skaalvik 2003 ). In which case, it may be useful to target interventions for CYP with LitD/D at self-efficacy rather than self-esteem, for example, asking students to make self-efficacy judgements before completing tasks. With repeated exposure and success, greater self-efficacy in specific domains may lead to enhanced self-concept in those domains. There would be benefit from future research evaluating this type of intervention amongst learners with LitD/D who are suffering from negative self-perceptions.

The importance of social and familial support in coping with LitD/D and maintaining self-esteem was highlighted in several studies. Being able to safely discuss feelings with parents helped children with LitD/D to maintain positive self-views, whereas negative interactions with peers could damage them (Glazzard 2010 ; Singer 2005 ). Furthermore, parents having a good understanding of dyslexia and associated needs may be a protective factor (Terras et al. 2009 ). Lindeblad et al. ( 2016 ) suggested that recent political reforms in Sweden, aiming to achieve greater equality within the education system, may be responsible for the positive psychological adjustment and self-perceptions found amongst their sample of CYP with LitD/D. They noted that being exposed to positive attitudes from significant others such as teachers or peers has the potential to protect against the development of negative self-perceptions. This highlights the importance of creating an accepting, understanding and inclusive atmosphere within schools.

Limitations

One major limitation of the body of research in this area relates to how researchers identify participants for their studies. It is important to note that at least half of research papers included in this review utilised a discrepancy-based definition, and most of the remaining papers did not specify whether a discrepancy-based definition had been used or not. This is likely to have impacted the findings of the review as children who meet the discrepancy-based definition of dyslexia have average or above-average IQ scores. Higher IQ scores are typically linked with better academic performance (Laidra et al. 2007 ), which may well lead to more positive academic self-concept. Therefore, individuals with LitD/D who do not meet the discrepancy-based definition may be at greater risk of low academic self-concept than the participants in the majority of studies reported here.