Healthy Living Guide 2020/2021

A digest on healthy eating and healthy living.

As we transition from 2020 into 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect nearly every aspect of our lives. For many, this health crisis has created a range of unique and individual impacts—including food access issues, income disruptions, and emotional distress.

Although we do not have concrete evidence regarding specific dietary factors that can reduce risk of COVID-19, we do know that maintaining a healthy lifestyle is critical to keeping our immune system strong. Beyond immunity, research has shown that individuals following five key habits—eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, keeping a healthy body weight, not drinking too much alcohol, and not smoking— live more than a decade longer than those who don’t. Plus, maintaining these practices may not only help us live longer, but also better. Adults following these five key habits at middle-age were found to live more years free of chronic diseases including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

While sticking to healthy habits is often easier said than done, we created this guide with the goal of providing some tips and strategies that may help. During these particularly uncertain times, we invite you to do what you can to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and hopefully (if you’re able to try out a new recipe or exercise, or pick up a fulfilling hobby) find some enjoyment along the way.

Download a copy of the Healthy Living Guide (PDF) featuring printable tip sheets and summaries, or access the full online articles through the links below.

In this issue:

- Understanding the body’s immune system

- Does an immune-boosting diet exist?

- The role of the microbiome

- A closer look at vitamin and herbal supplements

- 8 tips to support a healthy immune system

- A blueprint for building healthy meals

- Food feature: lentils

- Strategies for eating well on a budget

- Practicing mindful eating

- What is precision nutrition?

- Ketogenic diet

- Intermittent fasting

- Gluten-free

- 10 tips to keep moving

- Exercise safety

- Spotlight on walking for exercise

- How does chronic stress affect eating patterns?

- Ways to help control stress

- How much sleep do we need?

- Why do we dream?

- Sleep deficiency and health

- Tips for getting a good night’s rest

Will Healthy Eating Make You Happier? A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings Archive

- Open access

- Published: 14 August 2019

- Volume 16 , pages 221–240, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ruut Veenhoven ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5159-393X 1 , 2

29k Accesses

11 Citations

138 Altmetric

14 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Healthy eating adds to health and thereby contributes to a longer life, but will it also add to a happier life? Some people do not like healthy food, and since we spend a considerable amount of our life eating, healthy eating could make their life less enjoyable. Is there such a trade-off between healthy eating and happiness? Or instead a trade-on , healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance? If there is an effect of healthy eating on happiness, is that effect similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating happiness wise and what kind of people do not? If healthy eating does add to happiness, does it add linearly or is there some optimum for healthy ingredients in one’s diet? I considered the results published in 20 research reports on the relation between nutrition and happiness, which together yielded 47 findings. I reviewed these findings, using a new technique. The findings were entered in an online ‘findings archive’, the World Database of Happiness, each described in a standardized format on a separate ‘findings page’ with a unique internet address. In this paper, I use links to these finding pages and this allows us to summarize the main trends in the findings in a few tabular schemes. Together, the findings provide strong evidence of a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Surprisingly, this effect is not fully mediated by better health. This pattern seems to be universal, the available studies show only minor variations across people, times and places. More than three portions of fruits and vegetables per day goes with the most happiness, how many more for what kind of persons is not yet established.

Similar content being viewed by others

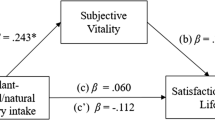

Vitality as a Mediator Between Diet Quality and Subjective Wellbeing Among College Students

Healthy food choices are happy food choices: Evidence from a real life sample using smartphone based assessments

Easy as (Happiness) Pie? A Critical Evaluation of a Popular Model of the Determinants of Well-Being

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Healthy eating, in particular a diet rich in fruit and vegetables (FV) adds to our health; primarily because it reduces our chances of contracting a number of eating related diseases (Oyebode et al. 2014 ; Bazzano et al. 2002 ; Liu et al. 2000 ). Since good health adds to happiness, it is likely that healthy diets will also add to happiness, but a firm connection has not been established.

In recent years, the relationship between obesity and mental states has begun to attract serious research interest (Becker et al. 2001 ; Rooney et al. 2013 ), as has the relationship between specific micro-nutrients and psychological health (Stough et al. 2011 ). As yet, there is little research on the relationship between nutrition and happiness.

It is worth knowing to what extent our eating habits affect our happiness. One reason is that most people are concerned about their happiness and look for ways to increase it. Most determinants of happiness are beyond our control, but what we eat is largely in our own hands. In this context, we would like to know whether there is a trade-off between healthy eating and happy living. Gains in length of life due to healthy eating may be counterbalanced by loss of satisfaction with life, as is argued in the debate on the benefits of drinking alcohol (Baum-Baicker 1985 ). If so, healthy eating may mean that we live longer, but not happier.

Empirical assessment of the effects of healthy eating on happiness is fraught with complications. One complication is that the effect of nutrition is probably not the same for everybody. Hence, we must identify what food pattern is optimal for what kind of person. A second problem is that happiness can influence nutrition behaviour, for example unhappiness can lead to the consumption of unhealthy comfort foods. Cause and effect must be disentangled. If a healthy diet does appear to add to happiness, then a third question arises: Is eating more healthy food always better or is there an optimum amount one should eat? For instance, is one apple a day enough to make us feel happy? Or will we feel better with four daily portions of fruit? How about small sins, such as a bar of chocolate or a daily glass of wine?

Research Questions

Is there a trade-of or between healthy eating and happiness? Or rather a trade-on , healthy eating adding to happiness? Or do the positive and negative effects balance?

Is this effect of healthy eating on happiness similar for everybody? If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not?

Is the shape of the relationship between healthy eating and happiness linear? The healthier one’s diet, the happier one is? Or is there an optimum?

I explored answers to these three questions in the available research literature and took stock of the findings obtained in quantitative studies on the relation between healthy eating and happiness. I applied a new technique for research reviewing, that takes advantage of an on-line findings archive, the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a ), which allows us to present a lot of findings in a few easy to oversee tabular schemes.

To my knowledge, the research literature on this subject has not been reviewed as yet. One review has considered the observed effect of eating fruit and vegetables on psychological well-being (Rooney et al. 2013 ), however, this review does not really deal with happiness, as will be defined in “ Happiness ” section, but is about mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Structure of the Paper

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. I define the key concepts in “ Concepts and Measures ” section; healthy eating and happiness and give a short account of happiness research. Next, I describe the new review technique in more detail: how the available research findings were gathered and how these are presented in an easy to overview way ( Methods section). Then I discuss what answers the available findings have provided for our research questions ( Results section). I found a clear answer to the first research question, but no clear answers to the second and third question. I discuss these findings in “ Discussion ” section and draw conclusions in “ Conclusions ” section.

Concepts and Measures

There are different view on what constitutes ‘healthy eating’ and ‘happiness’; for this reason, a delineation of these notions is required.

Healthy Eating

I follow the WHO ( 2018 ) characterization of a ‘healthy diet’ as involving’: 1) a varied diet, 2) rich in fruit and vegetables 3) a moderate amount of fats and oil and 4) less salt and sugar than usual these days. The typical Mediterranean diet is considered to fit these demands well. Unhealthy foods are considered to be rich in sugar and fat, such as processed meat, fast foods, sweets, cakes, sodas, deserts, alcohol and other foods high in calories, but low in nutritional content.

Throughout history, the word happiness has been used to denote different concepts that are loosely connected. Philosophers typically used the word to denote living a good life and often emphasize moral behaviour. ‘Happiness’ has also been used to denote good living conditions and associated with material affluence and physical safety. Today, many social scientists use the word to denote subjective satisfaction with life , which is also referred to as subjective well-being (SWB).

Definition of Happiness

In that latter line, I defined happiness as the degree to which an individual judge the overall quality of his/her life-as-a-whole favourably Footnote 1 (Veenhoven 1984 ) and in a later paper distinguished this definition of happiness from other notions of the good life (Veenhoven 2000 ). In this paper, I follow this conceptualization as it is also the focus of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018a ) from which the data reported in this paper are drawn.

Components of Happiness

Our overall evaluation of life draws on two sources of information: a) how well one feels most of the time and b) to what extent one perceives one is getting from life what one wants from it. I refer to these sub-assessments as ‘components’ of happiness, called respectively ‘hedonic level of affect’ and ‘contentment’ (Veenhoven 1984 ). The affective component tends to dominate in the overall evaluation of life (Kainulainen et al. 2018 ).

The affective component is also known as ‘affect balance’, which is the degree to which positive affective (PA) experiences outweigh negative affective (NA) experiences Positive experience typically signals that we are doing well and encourages functioning in several ways (Fredrickson 2004 ) and protects health (Veenhoven 2008 ). As such, this aspect of happiness was particularly interesting for this review of effects of healthy eating.

Difference with Wider Notions of Wellbeing

Happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life-as-a-whole’, should not be equated with satisfaction with domains of life, such as satisfaction with one’s life-style, one’s diet in particular. Likewise, happiness in the sense of the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life’ should not be equated with ‘objective’ notions of what is a good life, which are sometimes denoted using the same term. Though strongly related to happiness, mental health is not the same; one can be pathologically happy or be happy in spite of a mental condition.

Differences in wider notions of well-being are discussed in more detail in Veenhoven (15).

Measurement of Happiness

Since happiness is defined as something that is on our mind, it can be measured using questioning. Various ways of questioning have been used, direct questions as well as indirect questions, open questions and closed questions and one-time retrospective questions and repeated questions on happiness in the moment.

Not all questions used fit the above definition of happiness adequately, e.g. not the question whether one thinks one is happier than most people of one’s age, which is an item in the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyobomirsky and Lepper 1999 ). Findings obtained using such invalid measures are not included in the World Database of Happiness and hence were not considered in this research synthesis. Further detail on the validity assessment of questions on happiness is available in the introductory text to the collection Measures of Happiness of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2018b ) chapter 4. Some illustrative questions deemed valid for archiving in the WDH are presented below.

Question on overall happiness:

Taking all together, how happy would you say you are these days?

Questions on hedonic level of affect:

Would you say that you are usually cheerful or dejected?

How is your mood today? (Repeated several days).

Question on contentment:

How important are each of these goals for you?

How successful have you been in the pursuit of these goals?

Happiness Research

Over the ages, happiness has been a subject of philosophical speculation and in the second half of the twentieth century it also became the subject of empirical research. In the 1960’s, happiness appeared as a side-subject in research on successful aging (Neugarten et al. 1961 ) and mental health (Gurin et al. 1960 ). In the 1970’s happiness became a topic in social indicators research (Veenhoven 2017 ) and in the 1980s in medical quality of life research (e.g. Calman 1984 ). Since the 2000’s, happiness has become a main subject in the fields of ‘Positive psychology’ (Lyubomirsky et al. 2005 ) and ‘Happiness Economics’ (Bruni and Porta 2005 ). All this has resulted in a spectacular rise in the number of scholarly publications on happiness and in the past year (2017) some 500 new research reports have been published. To date (May 2018), the Bibliography of Happiness list 6451 reports of empirical studies in which a valid measure of happiness has been used (Veenhoven 2018c ).

Findings Archive: The World Database of Happiness

This flow of research findings on happiness has grown too big to oversee, even for specialists. For this reason, a findings archive has been established, in which quantitative outcomes are presented in a uniform format and are sorted by subject. This ‘World Database of Happiness’ is freely available on the internet at https://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl

Its structure is shown on Fig. 1 and a recent description of this novel technique for the accumulation of research findings can be found with Veenhoven ( 2019 ).

Start page of the World Database of Happiness, showing the structure of this findings archive

One of the subject categories in the collection of correlational findings is ‘Happiness and Nutrition’ (Veenhoven 2018c ). I draw on that source for this paper.

A first step in this review was to gather the available quantitative research findings on the relationship between happiness and healthy eating. The second step was to present these findings in an uncomplicated form.

Gathering of Research Findings

In order to identify relevant papers for this synthesis, I inspected which publications on the subject of healthy eating were already included of the Bibliography of World Database of Happiness, in the subject sections ‘ Health behaviour’ and consumption of ‘ Food ’. Then to further complete the collection of studies, various databases were searched such as Google Scholar, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, PubMed/Medline, using terms such as ‘ happiness ’, ‘ life satisfaction ’, ‘ subjective well-being ’, ‘ well-being ’, ‘ daily affect ’, ‘ positive affect ’, ‘ negative affect ’ in connection with terms such as ‘ food ’, ‘ healthy food ’, ‘ fruit and vegetables ’, ‘ fast food ‘and ‘ soft drinks ’ in different sequences.

All reviewed studies had to meet the following criteria:

A report on the study should be available in English, French, German or Spanish.

The study should concern happiness in the sense of life-satisfaction (cf. Healthy Eating section). I excluded studies on related matters, such as on mental health or wider notions of ‘flourishing’.

The study should involve a valid measure of happiness (cf. Happiness section). I excluded scales that involved questions on different matters, such as the much-used Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985 ).

The study results had to be expressed using some type of quantitative analysis.

Studies Found

Together, I found 20 reports of an empirical investigation that had examined the relationship between healthy eating and happiness, of which two were working papers and one dissertation. None of these publication s reported more than one study . Together, the studies yielded 47 findings.

All the papers were fairly recent, having been published between 2005 and 2017. Most of the papers (44.4%) were published in Medical Journals, including the International Journal of Behavioural Medicine, Journal of Health Psychology, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, The Journal of Psychosomatic Research, The International Journal of Public Health, and Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology.

People Investigated

Together, the studies covered 149.880 respondents and 27 different countries. The publics investigated in these studies, included the general population in countries and particular groups such as students, children, veterans and medical patients. The majority of respondents belonged to a general public group (50%), students made up 27.8%, with children and veterans each forming 11.1%.

Research Methods Used

Most of the studies were cross-sectional 64.4%, longitudinal and daily food diaries accounted for 22% and 10.2% of the total number of studies respectively, and one experimental study accounted for 3.4%.

I present an overview of all the included studies, including information about population, methods and publication in Table 1 .

Format of this Research Synthesis

As announced, I applied a new technique of research reviewing, taking advantage of two technical innovations: a) The availability of an on-line findings-archive (the World Database of Happiness) that holds descriptions of research findings in a standard format and terminology, presented on separate finding pages with a unique internet address. b) The change in academic publishing from print on paper to electronic text read on screen, in which links to that online information can be inserted.

Links to Online Detail

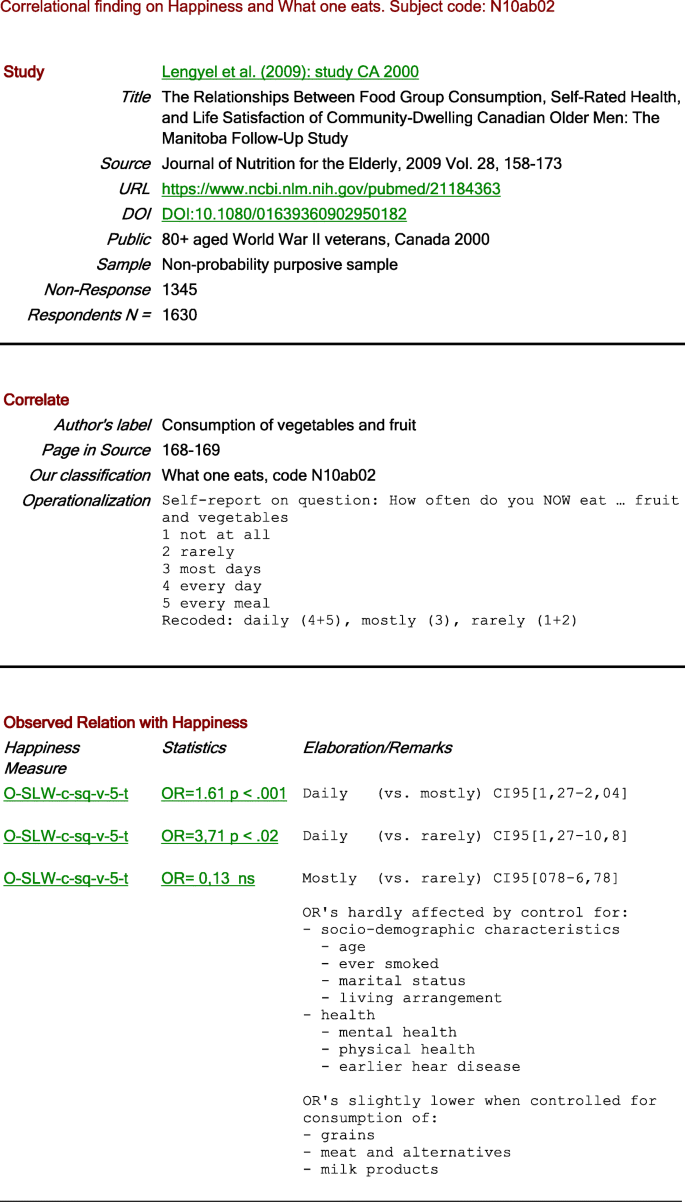

In this review, I summarize the observed statistical relationships as +, − or 0 signs. Footnote 2 These signs link to finding pages in the World Database of Happiness, which serves as an online appendix in this article. If you click on a sign, one such a finding page will open, on which you can see full details of the observed relationship; of the people investigated, sampling, the measurement of both variables and the statistical analysis. An example of such an electronic finding page is presented in Fig. 2 . This technique allows me to present the main trends in the findings, without burdening the reader with all the details, while keeping the paper to a controllable size, at the same time allowing the reader to check in depth any detail they wish.

Example of an online findings page

Organization of the Findings

I first sorted the findings by the research method used and these are presented in three separate tables. I distinguished a) cross-sectional studies, assessing same-time relationships between diet and happiness (Table 2 ), b) longitudinal studies, assessing change in happiness following changes in diet (Table 3 ), and c) experimental studies, assessing the effect of induced changes in diet on happiness (Table 4 ).

In the tables, I distinguish between studies at the micro level, in which the relation between diet and happiness of individuals was assessed and studies at the macro level, in which average diet in nations is linked to average happiness of citizens.

I present kinds of foods consumed vertically and horizontally two kinds of happiness: overall happiness (life-satisfaction) and hedonic level of affect.

Presentation of the Findings

The observed quantitative relationships between diet and happiness are summarized using 3 possible signs: + for a positive relationship, − for a negative relationship and 0 for a non-relationship. Statistical significance is indicated by printing the sign in bold . See Appendix . Each sign contains a link to a particular finding page in the World Database of Happiness, where you can find more detail on the checked finding.

Some of these findings appear in more than one cell of the tables. This is the case for pages on which a ‘raw’ (zero-order) correlation is reported next to a ‘partial’ correlation in which the effect of the control variables is removed. Likewise, you will find links to the same findings page at the micro level and the macro level in Table 2 ; on this page there is a time-graph of sequential studies in Russia from which both micro and macro findings can be read.

Several cells in the tables remain empty and denote blanks in our knowledge.

Advantages and Disadvantages of this Review Technique

There are pros and cons to the use of a findings-archive such as the World Database of Happiness and plusses and minuses to the use of links to an on-line source in a text like this one.

Use of a Findings-Archive

Advantages are: a) efficient gathering of research on a particular topic, happiness in this case, b) sharp conceptual focus and selection of studies on that basis, c) uniform description of research findings on electronic finding pages, using a standard format and a technical terminology, d) storage of these finding pages in a well searchable database, e) which is available on-line and f) to which links can be made from texts. The technique is particular useful for ongoing harvesting of research findings on a particular subject.

Disadvantages are: a) the sharp conceptual focus cannot easily be changed, b) considerable investment is required to develop explicit criteria for inclusion, definition of technical terms and software, Footnote 3 c) which pays only when a lot of research is processed on a continuous basis.

Use of Links in a Review Paper

The use of links to an on-line source allows us to provide extremely short summaries of research findings, in this text by using +, − and 0 signs in bold or not, while allowing the reader access to the full details of the research. This technique was used in an earlier research synthesis on wealth and happiness (Jantsch and Veenhoven 2019 ) and is described in more detail in Veenhoven ( 2019 ). Advantages of such representation are: a) an easy overview of the main trend in the findings, in this case many + signs for healthy foods, b) access to the full details behind the links, c) an easy overview of the white spots in the empty cells in the tables, and d) easy updates, by entering new sign in the tables, possibly marked with a colour.

The disadvantages are: a) much of the detailed information is not directly visible in the + and – signs, b) in particular not the effect size and control variables used, and c) the links work only for electronic texts.

Differences with Traditional Reviewing

Usual review articles cannot report much detail about the studies considered and rely heavily on references to the research reports read by the reviewer, which typically figure on a long list at the end of the review paper that the reader can hardly check. As a result, such reviews are vulnerable to interpretations made by the reviewer and methodological variation can escape the eye.

Another difference is that the conceptual focus of many traditional reviews in this field is often loose, covering fuzzy notions of ‘well-being’ rather than a well-defined concept of ‘happiness’ as used here. This blurs the view on what the data tell and involves a risk of ‘cherry picking’ by reviewers. A related difference is that traditional reviews of happiness research often assume that the name of a questionnaire corresponds with its conceptual contents. Yet, several ‘happiness scales’ measure different things than happiness as defined in “ Healthy Eating ” section, e.g. much used Life Satisfaction Scale (Neugarten et al. 1961 ), which measures social functioning.

Still another difference is that traditional narrative reviews focus on interpretations advanced by authors of research reports, while in this quantitative research synthesis I focus on the data actually presented. An example of such a difference in this review, is the publication by Connor & Brookie (Conner et al. 2015 ) who report no effect of healthier eating on mood in the experimental group, while their data show a small but significant gain in positive affect and a small but insignificant reduction of negative effect (Table 3 ), which together denote a positive effect on affect balance.

Difference with Traditional Meta-Analysis

Though this research synthesis is a kind of meta-analysis, it differs from common meta-analytic studies in several ways. One difference is the above- mentioned conceptual rigor; like narrative reviews many meta-analyses take the names given to variables for their content thus adding apples and oranges. Another difference is the direct online access to full detail about the research findings considered, presented in a standard format and terminology, while traditional meta-analytic studies just provide a reference to research reports from which the data were taken. A last difference is that most traditional meta-analytic studies aim at summarizing the research findings in numbers, such as an average effect size. Such quantification is not well possible for the data at hand here and not required for answering our research questions. My presentation of the separate findings in tabular schemers provides more information, both of the general tendency and of the details.

Let us now revert to the research questions ( Structure of the Paper section) and answer these one by one.

Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness?

Or does healthy eating rather add to happiness or do the positive and negative effects balance.

This question was addressed using different methods, a) same-time comparison of diet and happiness (cross-sectional analysis) b) follow-up of change in happiness following change in diet (longitudinal) and c) assessing the effect on happiness of induced change in diet (experimental). The results are summarized in, respectively, Tables 2 , 3 and 4 .

Cross-Sectional Findings

Together I found 42 correlational findings, which are presented in Table 2 . Of these findings 14 concerned raw correlations, while 28 reflected the results of a multivariate analysis. In Table 2 I see only micro level studies.

There were 16 + signs, which indicates that people who eat healthy tend to be happier than people who do not. A few (3) – signs were linked to unhealthy eating habits, i.e. fast food, soft drinks and sweets, and as such support this pattern.

Not all the findings supported the view that healthy eating goes with greater happiness. Consumption of soft-drinks was positively related to overall happiness, though not significantly, while the correlation with affect balance was significantly negative. A high intake of high caloric protein and fat is generally deemed to be unhealthy but appeared in one case to go with greater overall happiness, a study among medical patients in Arkhangelsk in Russia, where the medical conditions and cold climate may have require a higher intake of such foods.

The findings were mixed with respect to the relation of happiness with consumption of animal products, dairy and meat. For these foods a positive relation with overall happiness was found and a negative relation with affect level, in the case of milk products both relations were insignificant.

Several studies report both raw correlations and partial ones for the same population. Controls reduced the effect size somewhat but did not change the direction of the correlation. Importantly, the control for health and other health behaviours in 8 studies Footnote 4 did not change the direction of the correlation.

Longitudinal Findings

The findings of two studies that assessed the change in happiness following change in diet are presented in Table 3 , one study at the micro level among students and another study at the macro-level among the general population in Russia. Both studies found positive correlations, indicating that healthier eating adds to one’s happiness. The effects of greater consumption of meat and milk were not significant. No control variables were used in these studies. The relationship between healthy eating and affect level was not investigated longitudinally.

Experimental Study

To date, there is only one study on the effect of induced change to a healthier diet on an individual’s happiness. In this study people were randomly assigned to an experimental group and stimulated in various ways to consume more fruit and vegetables (FV), among other things by providing vouchers for health foods and sending e-mail reminders. After 2 weeks of increased FV consumption, the participant’s mood level had increased more than those of the control group.

Together, these findings provide a clear answer to our first research question. The net effect of healthy eating on happiness tends to be positive. If there is any trade-off at all, this is apparently more than compensated by the trade-on . The positive relationship is robust across research methods and measures of happiness.

Is this Effect of Healthy Eating on Happiness Similar for Everybody?

If not, what kind of people profit from healthy eating and what kind of people do not.

The 19 studies reported here cover a wide range of populations, the general public in several parts of the world, children, students, church members, medical patients and elderly war veterans. No great differences in the correlation between diet and happiness appear in these findings, though children seem to be happier when allowed to consume sweets and soft drinks. The cross-national study by Grant et al. ( 2009 ) observed some differences in strength of the correlation between healthy eating and happiness across part of the world, but no difference in direction of the correlation. The micro-level studies by Pettay ( 2008 ) and Warner et al. ( 2017 ) found no differences between males and females, while Ford et al. ( 2013 ) found a slightly bigger negative effect of unhealthy eating among women than among men.

The observed positive effect of healthy eating on happiness seems to be universal. Possible differences in what diet provides the most happiness for whom have not (yet) been identified.

Is the Shape of The Relationship Linear; the Healthier One’s Diet, the Happier One Is?

Or is there an optimum, if so what is optimal for whom.

Two studies find a linear relation between happiness and the number of portions fruits and vegetables per day, Lesani et al. ( 2016 ) among students in Iran and Blanchflower et al. ( 2013 ) among the general public in the UK, the latter study up to 7–8 portion a day. Another study observed an optimum at the lower level of 3–4 portions a day among female Iranian students (Fararouei et al. 2013 ). These thee studies suggest that the optimum is at least beyond three portions a day. As yet the focus of research has been on particular kinds of food, while the relationship between happiness and total diet composition has not been investigated.

Together, our findings leave no doubt that healthy eating ads to happiness, frequent consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular.

Causal Effect

Though happiness may influence nutrition behaviour, happier people being more inclined to follow a healthy diet, there is strong evidence for a causal effect of healthy eating on happiness. Spurious correlation is unlikely to exist, since correlations remain positive after controlling for many different variables. Causality is strongly suggested by 3 out of the 4 longitudinal findings and the experimental study.

This is not to say that healthy eating will always add to the happiness of everybody, but the trend is sufficiently universal and strong to be used in policies that aim at greater happiness for a greater number of people, such as in happiness education.

Causal Paths

Healthy eating will add to good health and good health will add to happiness. An unexpected finding is that the effect of healthy eating on happiness is not fully mediated by better health. As mentioned in “ Is there a Trade-Of between Healthy Eating and Happiness? ” section, significant positive correlations remain when health is controlled. This means that healthy eating also affects happiness in other ways. As yet I can only speculate about what these ways are. Possibly effects are that healthy eaters attract nicer people or that intake of fruit and vegetables has a direct effect on mood.

Limitations

This first synthesis of the research on happiness and healthy eating draws on 20 empirical studies, which together yielded 47 findings. Though these results provide strong indications of a positive effect of healthy eating on happiness, we need more research to be sure. This research synthesis limits to happiness defined as the subjective enjoyment of one’s life as a whole and measure that matter adequately. This conceptual focus has a piece, we came to know more about less. The available research findings do not allow a traditional meta-analysis, both because of the limited numbers and their heterogeneity. Hence, we cannot yet compute effect sizes or test statistical significance of differences.

Topics for Further Research

Although we now know that healthy eating tends to make one’s life more satisfying, we do not know in much detail what particular diets are the most conducive to the happiness of what kinds of people. We are also largely in the dark about the causal mechanisms involved. The focus of current research is very much on particular food items, consumption of fruit and vegetables in particular. Future research should pay more attention to the effect of total diets on happiness.

Conclusions

Healthy eating adds to happiness, not just by protecting one’s health but also in other, as yet unidentified, ways. This finding deserves to be drawn to the public’s attention. People should know that changing to a healthier diet will not be at the cost of their happiness but will add to it. Faulty beliefs and misleading advertisements should be counter-balanced by this established fact.

Likewise, Diener (26) defined ‘life satisfaction’ as an overall judgement of one’s life.

The technique also allows summarization in a number, which can be presented in a stem-leaf diagram, or in short verbal. Statements, such as ‘U shaped relationship’

The archive can be easily adjusted for other subjects. The software is Open Source

Blanchflower et al. ( 2013 ); Fararouei et al. ( 2013 ); Ford et al. ( 2013 ); Huffman and Rizov ( 2016 ); Lesani et al. ( 2016 ); Lengyel et al. ( 2009 ) and Kye and Park ( 2014 )

Studies Included in this Research Synthesis Are Marked with a Link below the Reference. The Links Lead to a Standardized Description of that Study in the World Database of Happiness. The Codes Denote Place and Year of the Study

Averina, M. M., Brox, J. & Nilsson, O. (2005) Social and lifestyle determinants of depression, anxiety, sleeping disorders and self-evaluated quality of life in Russia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40: 511–518 Study RU Archangelsk 1999

Baum-Baicker, C. (1985). The psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: a review of the literature. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 15 (4), 305–322.

Article Google Scholar

Bazzano, L. A., He, J., Ogden, L. G., Loria, C. M., Vupputuri, S., Myers, L., & Whelton, P. K. (2002). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76 (1), 93–99.

Becker, E. S., Margraf, J., Türke, C., Soeder, U., & Neumer, S. (2001). Obesity and mental illness in a representative sample of young women. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders, 25 (Suppl. 1), S5–S9.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2013). Is psychological well-being linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research, 114 , 785–801 Study GB Wales 2007-2010 .

Breslin, G., Donnelly, P., & Nevill, A. M. (2013). Socio-demographic and behavioural differences and associations with happiness for those who are in good and poor health. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1 , 142–154 Study GB 2009 .

Bruni, L., & Porta, P. L. (2005). Economics and happines . UK: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Caligiuri, S., Lengyel, C. O., & Tate, R. B. (2012). Changes in food group consumption and associations with self-rated diet, health, life satisfaction, and mental and physical functioning over 5 years in very old Canadian men: The Manitoba follow-up study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 16 (8), 707–712 Study CA 2000-2005 .

Calman, A. C. (1984). Quality of life in cancer patients--a hypothesis. Journal of Medical Ethics, 10 , 124–127.

Chang, H. H., & Nayga, R. M., Jr. (2010). Childhood obesity and unhappiness: The influence of soft drinks and fast food consumption. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11 , 261–275 Study TW 2001 .

Conner, T.S. & Brookie, K.L. (2017). Let them eat fruit! The effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on the psychological well-being in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. PLOS one , February. 3201 Study NZ Auckland 2015

Conner, T.S., Brookie, K.L. & Richardson, A.C. (2015). On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20: 413–444. Study NZ Auckland 2013

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Griffin, S., & Larsen, R. J. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49 , 71–75.

Fararouei, M., Akbartabar Toori, M. & Brown, I.J. (2013). Happiness and health behaviour in Iranian adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 36: 1187–1192. Study IR 2008

Ford, P.A., Jaceldo-Siegl, K. & Lee, J.W. (2013). Intake of mediterranean foods associated with positive and low negative affect. Journal of Psychosomatic Research , 74 (2013) 142–148. Study ZZ Anglo-America 2002

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden - and - build theory of positive emotions . Philosophical Transactions, Biological Sciences , 359: 1367–1377.

Grant, N.; Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J. (2009). The relationship between life satisfaction and health behaviour: a cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioural Medicine , 16: 259–268 Study ZZ 1999-2001

Gschwandtner, A., Jewell, S. & Kambhampati, U. (2015). On the relationship between lifestyle and happiness in the UK. Paper for 89th Annual Conference of AES, 2015, 1–33, Warwick, England. Study GB 2012

Gurin, G., Feld, S. & Veroff, J. (1960). Americans view their mental health. A nationwide interview survey. Basic Books, New York, USA (Reprint in 1980, Arno Press, New York, USA).

Honkala, S., Al Sahli, N., & Honkala, E. (2006). Consumption of sugar products and associated life- and school- satisfaction and self-esteem factors among schoolchildren in Kuwait. Acta Odonatological Scandinavia, 64 , 79–88 Study KW 2002 .

Huffman, S.K.; Rizov, M. (2016). Life satisfaction and diet: Evidence from the Russian longitudinal monitoring survey. Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, 2016, 1–25, Boston, Massachusetts. Study RU 1994-2005

Jantsch, A & Veenhoven, R. (2019). Private wealth and happiness: A research synthesis using an online findings archive . In Gael Brule & Christian Suter (Eds.), “Wealth(s) and Subjective Well-Being Springer/Nature, pp 17–50.

Kainulainen, S., Saari, J., & Veenhoven, R. (2018). Life-satisfaction is more a matter of how well you feel, than of having what you want . International Journal of Happiness and Development, 4 (3), 209–235.

Kye, S.K. & Park, K. (2014). Health-related determinants of Happiness in Korean Adults. International Journal of Public Health, 59: 731–738. Study KR 2009

Lengyel, C. O., Oberik Blatz, A. K., & Tate, R. B. (2009). The relationships between food group consumption, self-rated health, and life satisfaction of community-dwelling canadian older men: The manitoba follow-up study. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 28 , 158–173 Study CA 2000 .

Lesani, A., Javadi, M., & Mohammadpoorasl, A. (2016). Eating breakfast, fruit and vegetable intake and their relation with happiness in college students. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 21 , 645–651 Study IR Tehran 2011 .

Liu, S., Manson, J. E., Lee, I. M., Cole, S. R., Hennekens, C. H., Willett, W. C., & Buring, J. E. (2000). Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Women’s Health Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72 (4), 922–928.

Lyobomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46 , 137–155.

Lyubomirsky, S., Diener, E., & King, L. A. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131 , 803–855.

Mujcic, R., & Oswald, A. (2016). Evolution of well-being and happiness after increases in consumption of fruit and vegetables. American Journal of Public Health, 106 (8), 1504–1510 Study AU 2007-2009 .

Neugarten, B.L., Havighurst, R.J. & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction . Journal of Gerontology , 16: 134–143.

Oyebode, O., Gordon-Dseagu, V., Walker, A., & Mindell, J. S. (2014). Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality: analysis of Health Survey for England data. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 68 (9), 856–862.

Pettay, R.S. (2008). Health behaviours and life satisfaction in college students . PhD Thesis, Kansas State University, USA. Study US 2006

Rooney, C., McKinley, M.C. & Woodside, J.V. (2013). The Potential Role of Fruit and Vegetables in aspects of Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Literature and Future Directions. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72: 420–432.

Stough, C., Scholey, A., Lloyd, J., Spong, J., Myers, S., & Downey, L. A. (2011). The effect of 90-day administration of a high dose vitamin B-complex on work stress. Human Physio-pharmacology, 26 (7), 470–476.

Google Scholar

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness . Reidel (now Springer), Dordrecht, Netherlands.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). The four qualities of life. Ordering concepts and measures of the good life . Journal of Happiness Studies, 1 , 1–39.

Veenhoven, R. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care . Journal of Happiness Studies, 9 , 449–464.

Veenhoven, R. (2017). Co-development of happiness research: Addition to “fifty years after the social indicator movement . Social Indicators Research , 135: 1001–1007.

Veenhoven, R. (2018a) World database of happiness: Archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life . Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Veenhoven, R. (2018b). Measures of happiness . World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Veenhoven, R. (2018c). Bibliography of happiness . World Database of Happiness, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Veenhoven, R. (2019). World database of happiness: A ‘findings archive’ . Chapter in Handbook of Wellbeing, Happiness and the Environment. Editors: Heinz Welsch, David Maddison and Katrin Rehdanz, Edward Elgar Publishing (forthcoming).

Warner, R.M., Frye, K. & Morrell, J. S. (2017). Fruit and vegetable intake predicts positive affect. Journal of Happiness Studies , 18: 809–826. Study US New England 2013

WHO (2018) Healthy diet. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Erasmus Happiness Economics Research Organization EHERO, Erasmus University Rotterdam, POB 1738, 3000DR, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Ruut Veenhoven

Optentia Research Program, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ruut Veenhoven .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Signs used in Finding Tables

positive correlation, statistically significant

positive correlation, not statistically significant

positive and negative correlations, depending on control variables used

no correlation

negative correlation, not statistically significant

negative correlation, statistically significant

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Veenhoven, R. Will Healthy Eating Make You Happier? A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings Archive. Applied Research Quality Life 16 , 221–240 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09748-7

Download citation

Received : 20 December 2018

Accepted : 20 June 2019

Published : 14 August 2019

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09748-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health behaviour

- Research synthesis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

The Future of Healthy Eating Research

Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change (PSE) strategies are critical tools in the battle for good health in adults and children.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Megan Lott & Mary Story Summer 2019

The most recent national data available on US rates of obesity and diet illustrate that Americans are still not consuming enough fruits, vegetables, dairy, and whole grains, but are eating too many added sugars, saturated fats, and sodium, mostly in the form of sweetened beverages, desserts, and snacks. 1 Relatedly, the United States continues to face significant public health problems, with large geographic-, income-, race-, and ethnicity-based disparities in diet quality, overweight and obesity rates, and chronic health conditions. 2

Healthy Eating, Active Living

This collection of articles, produced for Grantmakers In Health and supported by the Colorado Health Foundation, explores the latest thinking from health funders, researchers, and advocates on healthy eating and active living (HEAL) and healthy communities.

Healthy Eating, Active Living: Reflections, Insights, and Considerations for the Road Ahead | 1

Healthy eating and active living through an equity lens, connecting health and education so children can learn and thrive | 1, the future of healthy eating research | 2, how to improve physical activity and health for all children and families, the colorado health foundation’s heal evolution, how market forces could improve how we eat, the power of business to change food culture for the better | 1, political power as a tool to improve the health of all americans | 1, evaluate, invest in advocacy, and shrink the change.

Policies, systems, and environments are significant determinants of children’s dietary intake, weight, and health. Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change (PSE) strategies go beyond education and information programming to embed changes in a community, and they are designed to be more sustainable and reach a larger number of people than programming alone. PSE changes aim to create communities where healthy choices are easy, safe, practical, and affordable for all.

The Importance of PSE Strategies

Although it is important to target individuals for behavior change, it is also imperative that people live in an environment that supports good decisions. According to “ The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century ,” a 2002 report by the Institute of Medicine, “It is unreasonable to expect that people will change their behavior easily when so many forces in the social, cultural, and physical environment conspire against such change.”

Unfortunately, the food environments that children experience in childcare, schools, restaurants, grocery stores, and other community settings, as well as the widespread marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages, often do not support healthy choices. Inadequate nutrition, poor diet, food insecurity, and obesity are most pronounced in lower-income communities that lack access to healthy foods. Often these households have limited funds to buy—or time to prepare—healthy foods, and they frequently live in neighborhoods surrounded by inexpensive and heavily marketed unhealthy foods and beverages. Until all children in America have access to affordable, healthy foods where they live, learn, and play, efforts to educate children and families on healthy eating will be of limited usefulness.

Along these lines, the 2005 Institute of Medicine report “ Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance ” concludes that environmental and policy influences are potentially the most powerful strategies for addressing childhood obesity. At that time, little was known about the most important food- and diet-related environmental influences that impact children’s eating patterns and weight, or about the most feasible and effective policies for improving children’s food environments. To reduce this knowledge gap, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), the largest US philanthropic foundation dedicated to improving health for all Americans, launched Healthy Eating Research (HER) , a national research program, in 2005.

The Research Program

HER supports research on PSE strategies with strong potential to promote the health and well-being of children at a population level. Specifically, HER aims to help all children receive optimal nutrition and obtain a healthy weight. HER grantmaking focuses on children and adolescents from birth to 18 years old, and their families, giving priority to lower-income and racial and ethnic minority populations that are at risk of poor nutrition and obesity. Findings are expected to advance the field’s efforts to ensure that all children and their families have the opportunity and resources to experience the best physical, social, and emotional health possible and to promote health equity.

Since its inception in 2005, HER has released 18 competitive calls for proposals and awarded more than 200 grants, totaling approximately $25.3 million, focused on the following: improving dietary patterns and feeding practices for infants, toddlers, and young children; improving food environments in schools and after-school, childcare, and preschool settings; increasing healthy food access; agricultural and nutrition policies; food pricing and economic incentives and disincentives; food and beverage marketing and promotion; sugar-sweetened beverages; water access; message framing; and menu labeling.

HER has been a leader in providing evidence in areas where there has previously been little or no research. For instance, HER studies and papers have provided key evidence showing the following:

- Policies to improve school food environments have been implemented without resulting in increased food waste.

- Childcare settings participating in the federal Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) serve healthier foods than nonparticipating settings, but there is room for improvement in nutrition quality in all childcare settings.

- Children and adolescents frequently visit corner stores in close proximity to schools where availability of healthy foods is limited and the most frequently purchased items are energy dense and of low nutrition. But initiatives in communities have begun to demonstrate success in improving the availability of healthy food in these stores.

- Food industry standards for regulating unhealthy food advertising have improved but still have a way to go.

- Current sugar-sweetened beverage taxes are neither large enough nor transparent enough to change behavior without accompanying consumer education, but larger taxes have the potential to improve behavior and weight outcomes.

- While studies of menu labeling have shown limited evidence of changing customers’ purchasing behaviors, they have increased awareness of calorie information.

- PSE strategies to improve healthier food and beverage choices in food retail settings (i.e., grocery stores and restaurants) have largely not been implemented or evaluated.

In addition to making grants, HER launched a new research strategy in 2013 focused on bringing together a panel of national experts and leaders to develop recommendations on timely and relevant topics, and to inform the development of healthy eating and obesity-prevention policies and practices at the local, state, and national levels. To date, HER has convened four panels of national experts to develop comprehensive recommendations regarding age-based definitions of healthier beverages; responsible practices in marketing food to children; minimum stocking levels of healthful food for small retail food stores; and best practices for promoting healthy nutrition and feeding patterns for infants and toddlers. The recommendations have been widely used by several organizations, including Partnership for a Healthier America, 1,000 Days, and Pan American Health Organization, and have been cited frequently by advocates such as the National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity and the American Heart Association during state- or federal-rule-making comment periods. Not all research questions lend themselves well to this format, but the benefits of an expert-panel approach include a multidisciplinary consensus-building process, consolidation and augmentation of existing standards or recommendations, and the opportunity to fill research gaps in a timely manner.

The variety of funding mechanisms that HER offers—competitive calls for proposals, small-scale commissioned studies, rapid-response studies and papers, and expert panels—as well as the methods available for communicating research findings—scientific publications, research reviews, issue briefs, policy briefs, and infographics—has enabled the program to be highly responsive to the needs of advocates, policymakers, and other decision makers, as well as to contribute new scientific knowledge to the field.

HER’s Future

Child obesity remains a critical public health issue. In order to tackle this problem, PSE strategies may need to take a more holistic approach in order to achieve optimal health for children. Our health is shaped by our social conditions and circumstances, including the communities and neighborhoods in which we live, access to education, good jobs with fair pay, housing, quality health care, and social support networks. Many Americans will not achieve good health until systemic barriers—poverty, discrimination, and racism—are dismantled and the social, environmental, and economic conditions of these social determinants of health are improved. 3 Moreover, environmental factors influencing child nutrition, diet quality, and food access are often compounded by social and individual factors such as gender, age, race, ethnicity, education level, socioeconomic status, and disability status.

In her 2017 National Academy of Medicine discussion paper, “Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention,” Shiriki Kumanyika points out that the reported differences in obesity prevalence and trends by racial and ethnic minority groups or those of low socioeconomic status are not chance occurrences. Rather, they reflect certain population groups “whose opportunities and social agency have been systematically and unfairly curtailed to be more exposed to obesity-promoting environmental influences and less able to avoid the associated adverse effects on eating and physical activity.” 4 Thus, Kumanyika argues, we will not be able to tackle the issues of obesity and diet quality equitably without also addressing the social determinants of these issues.

Going forward, HER is broadening its scope to establish a research base on PSE strategies to promote supportive policies and enabling environments for caregivers, families, and communities to foster optimal nutrition, diet quality, and weight. This approach will go beyond the work we have funded in the past to focus on the interaction of social, political, economic, and familial influences and environments on nutrition, healthy eating, and healthy weight.

Ultimately, this work aims to boost healthy eating by providing the evidence needed to promote healthier food environments and establish equitable and supportive policies for caregivers and families. Approaches need to be considered that cut across multiple levels: empowering individuals and families to make healthier choices; creating or adjusting microenvironments where children and families live, learn, work, and play, and building supportive macroenvironments that provide families with adequate economic supports and poverty-reduction strategies. Applying this framework to an early intervention designed to promote diet quality and mitigate obesity risk for new parents and their babies might suggest several different possibilities:

- Educating parents on strategies around what and how to feed their infant in the first year (empowering families)

- Implementing up-to-date nutrition standards and feeding practices in the infant’s childcare setting (enabling microenvironment)

- Improving access to economic supports for the family, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), so that a family has more money available to spend on healthy food

- Examining a parent’s access to paid family leave or breastfeeding supports in the workplace, which would improve a new parent’s ability to follow through on recommended feeding practices

Poor diet and obesity are health equity issues. In order to achieve health equity—whereby everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible—we need to apply an equity lens across all levels of influence and PSE strategies. This includes addressing disparities among communities of color, between rural and urban geographic areas, in socioeconomic status, and among other groups of marginalized children and their caregivers. Not all families and communities operate within the same constraints or have access to the same resources. In cases where resources are lacking, this approach requires an intentional examination of how interventions or PSE strategies may need to be adapted and tested, given these new sets of constraints.

The Link Between Research and Policy

Over the years, HER has succeeded in bridging the gap between researchers and key decision makers by identifying a critical research gap, acting on it, and effectively communicating findings to advocates and policymakers. Research conducted and funded by HER continues to inform high-level federal, state, and local policy as well as garner extensive media coverage, and HER’s grantees have been quite successful in using funding from external agencies and publishing their scholarly work in high-profile peer-reviewed journals. Study findings have often led to meaningful improvements in food and nutrition policies, systems, and environments, which we know to be significant determinants of children’s weight and health.

In order to design research studies to address disparities and inequities in healthy eating and weight, and to identify and target the socioeconomic and contextual barriers contributing to these disparities and inequities, there must be a two-way flow of information between policymakers and the research and advocacy communities. 5 We hope that this new conceptual framework will help drive demand for research focusing on the social determinants of health related to nutrition and enhance the field’s focus on the interactions of individual, environmental, and social factors that influence a child’s health, diet, and risk for obesity. We also hope that others can build on the lessons learned and approach HER to fund PSE strategies in the United States and globally, and communicate research results to a broad array of audiences to improve healthy eating and weight status among children and adults.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Megan Lott & Mary Story .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

- See All Locations

- Primary Care

- Urgent Care Facilities

- Emergency Rooms

- Surgery Centers

- Medical Offices

- Imaging Facilities

- Neurology & Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Orthopaedics

- Pediatrics at Guerin Children's

- Urgent Care

- Medical Records Request

- Insurance & Billing

- Pay Your Bill

- Advanced Healthcare Directive

- Initiate a Request

- Help Paying Your Bill

.cls-1{fill:#2e64ab;}.cls-2{fill:#fff;} CS-Blog Cedars-Sinai Blog

Eating healthy: 8 diet questions answered.

May 16, 2018 Cedars-Sinai Staff

Nutrition is a hotly debated topic and fad diets and conflicting information are everywhere. We sat down with registered dietician Kelly Issokson to answer some common questions.

Q: How do I know which diet is right for me?

Issokson: In general, a Mediterranean diet is recommended to help prevent and manage chronic disease. However, there is no one diet that can meet the needs of everyone. Diet needs are very individual and can depend on many factors—including age, current medical conditions, medications, intestinal function, and more. A registered dietitian can help tailor a diet that meets your individual needs.

Read: The Science of Eating

Q: How many times a day should I be eating?

Issokson: Again, this varies and depends on your goals, medical needs, etc. For example, recent studies suggest that intermittent fasting may be beneficial for weight loss and longevity. On the other hand, people with nausea or reflux may benefit from smaller and more frequent meals.

"No foods should be considered off limits."

Q. What are some simple ways I can improve my nutrition today?

Issokson: Eating foods cooked from scratch is one of the best ways to improve your health. If this isn't possible, try to buy foods that are minimally processed, like roasted chicken as opposed to sausage, baked potatoes instead of chips, or fresh fruit instead of fruit snacks with added sugars. The less processed a food is, the better it is for your health.

Read: Ask a Dietitian: What's in Your Fridge?

Q: Should I count calories?

Issokson: I don't generally recommend this. Being more mindful about what you eat and why you're eating can help with weight management. Savor your meals and think of how your food will nourish your body. Listen to your body's hunger and satiety cues—eat when your body tells you that you need nourishment, and stop when your body tells you you're full. Chewing your foods well and eating slowly helps you better understand your body's needs.

Read: Grilling? Keep It Safe and Healthy with These Tips

Q: Should I avoid carbs?

Issokson: Research shows that carbohydrates do not contribute to weight gain, but overeating does. Eat a balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats for best health—minimally processed versions are best.

Read: Is Eating Gluten-Free a Good Idea?

Q: Does time of day matter when it comes to eating?

Issokson: Our bodies follow a circadian rhythm (24-hour cycle that tells our bodies when to sleep, wake, eat), and some research shows that we metabolize foods poorly when eating at irregular times ( e.g. , sleeping during the day and eating at night). Try to eat at similar times on a daily basis, and don't eat right before going to sleep.

"No one diet can meet the needs of everyone."

Q: Should I do a juice cleanse?

Issokson: Your body naturally cleanses itself. There is no research to support cleanses—they can be expensive, and they can lead to unhealthy relationships with food.

Read: Do Detox Diets and Cleanses Work?

Q: What's one food item or ingredient you advise people to avoid?

Issokson: I get questions like this often, and I think a better way to think about eating is that no foods should be considered "off limits." Try to eat foods that are minimally processed and have little to no additives on a regular basis.

Cooking for yourself and eating a mostly plant-based diet can do wonders for your health—I think this is one of the most underappreciated and basic principles about eating. But having a donut every once in a while is OK, too!

Popular Categories

Blog & magazines, popular topics, make an appointment, call us 7 days a week, 6 am - 9 pm pt, support cedars-sinai.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Year in Well

10 Lessons We’ve Learned About Eating Well

Water vs. seltzer? Can food affect the brain? We’ve rounded up useful research on diet and nutrition to stay healthy in the new year.

As 2021 came to a close, we looked back on our reporting on diet and nutrition to glean tips we could bring into a new year. Here are 10 findings to remember next time you head to the supermarket or to the kitchen.

1. Look at patterns in your diet, rather than focusing on “good” or “bad” foods.

In October, the American Heart Association released new dietary guidelines to improve the hearts and health of Americans of all ages and life circumstances. Instead of issuing a laundry list of “thou shalt not eats,” the committee focused on how people could make lifelong changes, taking into account each individual’s likes and dislikes as well as ethnic and cultural practices and life circumstances. “For example, rather than urging people to skip pasta because it’s a refined carbohydrate, a more effective message might be to tell people to eat it the traditional Italian way, as a small first-course portion,” Jane Brody explained.

2. What you eat can affect your mental health.

As people grappled with higher levels of stress, depression and anxiety during the pandemic, many turned to their favorite comfort foods: ice cream, pastries, pizza, hamburgers. But studies in an emerging field of research known as nutritional psychiatry, which looks at the relationship between diet and mental wellness, suggest that the sugar-laden and high-fat foods we often crave when we are stressed or depressed, as comforting as they may seem, are the least likely to benefit our mental health. Whole foods such as vegetables, fruit, fish, eggs, nuts and seeds, beans and legumes and fermented foods like yogurt may be a better bet.

“The idea that eating certain foods could promote brain health, much the way it can promote heart health, might seem like common sense,” Anahad O’Connor wrote in his story on the research. “But historically, nutrition research has focused largely on how the foods we eat affect our physical health, rather than our mental health.”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.11(5); 2019 May

An Evidence-based Look at the Effects of Diet on Health

Sean kandel.

1 Internal Medicine, University of Connecticut, New Britain, USA

Diet is a daily activity that has a dramatic impact on health. There is much confusion in society, including among medical professionals, about what constitutes a healthy diet. Many reviews focus on one aspect of healthy dietary practices, but few synthesize this data to form more comprehensive recommendations. This article will critically review and holistically synthesize the data on diet with firm morbidity and mortality endpoints derived from three key, high quality studies, which are further supported with several additional articles. Specific recommendations of types and quantities of food to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke will be provided. The effect of these diets on cancer and mood disorders as covered in the articles reviewed will also be discussed.

Introduction and background

Why do we care about diet?

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of death in the United States [ 1 ]. Obesity and type 2 diabetes, both directly diet modifiable, are two of the largest contributors to CVD. Additionally, cancer and mood disorders both also have significant impacts on morbidity and mortality. What we eat may allow us to powerfully intervene on these issues, which are the largest health issues affecting our country.

Article selection methods

A keyword search was performed in the PubMed database through July 2018 using permutations of the phrases: “diet randomized controlled trial,” “diet morbidity mortality,” and “fish coronary artery disease.” Fish was specifically searched for as it has been identified as possibly being cardioprotective, as noted by the American Heart Association. Only randomized controlled trials, large, carefully controlled observational studies, or meta analyses looking at firm morbidity/mortality endpoints were considered. Three such representative articles will be reviewed in depth here, with many supporting articles also referenced. Although some data related to cancer and mood disorders is discussed, the primary focus of this review is the effect of diet on coronary artery disease (CAD) and stroke.

What we already knew about diet and its effects on health

Most of the data we have about diets are from observational studies. Some of these studies are outstanding, but nonetheless are limited by the biases that any observational study can have (i.e. confounding variables and correlation without demonstration of causation). Despite this, several massive studies have been replicated and statistically controlled to afford some general trends worth noting. Studies looking at up to 2.88 million patients have reproducibly shown that being at extremes of weight (either morbidly obese or underweight) leads to an increased risk of death, and being overweight or obese leads to an increased risk of death from diabetes or kidney disease [ 2 - 3 ]. Abdominal obesity has been shown to increase coronary artery plaque deposition on computed tomography (CT) imaging [ 4 ]. Thus, being a healthy body weight is the first step in reducing cardiovascular risk. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet randomized control trial showed that a diet that favors vegetables, fruits, low fat dairy, and minimizes red meats, fats, oils, and snacks/sweets (processed foods with high sugar/simple carbohydrates) leads to a slightly lower blood pressure (about a 5.5 mm Hg and a 3 mm Hg lower systolic and diastolic, respectively) when applied to hypertensive patients [ 5 ]. The causative role of diabetes on (CAD) and kidney disease has been well documented [ 6 ]. Notably, type 2 diabetes has a dramatic role in morbidity and mortality, and despite some people having a genetic predisposition is ultimately diet induced. It can be prevented by eating a healthy diet, and even after its development can usually be completely reversed with diet and exercise, even in later stages [ 7 - 8 ].

Does low cholesterol correlate with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease?

The foundational studies looking at cholesterol and its effects on health, based on the Framingham study, did not definitely show that the cholesterol levels predicted CVD risk in the general population. The study only achieved statistical significance for total cholesterol in certain age groups (men over age 65 years and women between the ages of 50-79 years). The study did show that the total cholesterol to high density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio seemed to be more predictive of cardiovascular events than the absolute cholesterol numbers [ 9 ]. Subsequent to this, 19 studies looking at low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol showed no association or an inverse association between LDL levels and CVD in people over the age of 60 years [ 10 ]. Low HDL did seem to have a correlation with CAD in these studies. Notably, in a review of 115,000 patients who had a myocardial infarction, patients with lower LDLs had higher mortalities post myocardial infarction [ 11 ]. This study is referred to as “The Lipid Paradox.” In addition, despite eating very high levels of saturated fat and cholesterol, the French have very low rates of CVD [ 12 ] - this is referred to as “The French Paradox.”

If we are to follow the logic that the higher the cholesterol level, the more plaque deposits in the coronary arteries, and thus the more cardiac ischemia/infarctions occur, you would expect that as a person ages and continues to eat unhealthy food that the amount of plaque deposition and ischemia/infarction would also increase. However, this is not the pattern seen in the original Framingham study publication. We also have “The Lipid Paradox,” “The French Paradox,” and a meta-analysis of 19 studies showing no or an inverse correlation of LDL with risk of CVD. LDL cholesterol levels likely do not correlate with the development of CAD as well as was once believed.

Effects of diet are hard to study

The above discussion of the lack of correlation of LDL cholesterol levels with the development of CAD is important to understand why the articles discussed in this review were chosen and why others were excluded. The effects of diet are cumulative and take decades to manifest. However, most researchers want answers much sooner than this, and thus turn to surrogates to measure dietary effects on health, with the most common surrogate being cholesterol. However, as discussed above, cholesterol levels may not reliably predict CAD. Studies that evaluate the effects of diet based on firm endpoints, such as a diagnosis of myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, or mood disorder, are the most reliable data from which to draw conclusions. This literature is the focus of the remainder of this article.

The Mediterranean diet

Estruch and his colleagues have produced a large randomized controlled trial looking at the effects of diet on health with hard morbidity and mortality endpoints [ 13 ]. Their study was recently retracted and republished after they discovered that 1588 of the 7400 participants really weren’t randomized. The resubmitted work includes statistical modeling which validates their initial results despite the non-randomized group.