Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Recent quantitative research on determinants of health in high income countries: A scoping review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Centre for Health Economics Research and Modelling Infectious Diseases, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Institute, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

- Vladimira Varbanova,

- Philippe Beutels

- Published: September 17, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Identifying determinants of health and understanding their role in health production constitutes an important research theme. We aimed to document the state of recent multi-country research on this theme in the literature.

We followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines to systematically identify, triage and review literature (January 2013—July 2019). We searched for studies that performed cross-national statistical analyses aiming to evaluate the impact of one or more aggregate level determinants on one or more general population health outcomes in high-income countries. To assess in which combinations and to what extent individual (or thematically linked) determinants had been studied together, we performed multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis.

Sixty studies were selected, out of an original yield of 3686. Life-expectancy and overall mortality were the most widely used population health indicators, while determinants came from the areas of healthcare, culture, politics, socio-economics, environment, labor, fertility, demographics, life-style, and psychology. The family of regression models was the predominant statistical approach. Results from our multidimensional scaling showed that a relatively tight core of determinants have received much attention, as main covariates of interest or controls, whereas the majority of other determinants were studied in very limited contexts. We consider findings from these studies regarding the importance of any given health determinant inconclusive at present. Across a multitude of model specifications, different country samples, and varying time periods, effects fluctuated between statistically significant and not significant, and between beneficial and detrimental to health.

Conclusions

We conclude that efforts to understand the underlying mechanisms of population health are far from settled, and the present state of research on the topic leaves much to be desired. It is essential that future research considers multiple factors simultaneously and takes advantage of more sophisticated methodology with regards to quantifying health as well as analyzing determinants’ influence.

Citation: Varbanova V, Beutels P (2020) Recent quantitative research on determinants of health in high income countries: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 15(9): e0239031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031

Editor: Amir Radfar, University of Central Florida, UNITED STATES

Received: November 14, 2019; Accepted: August 28, 2020; Published: September 17, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Varbanova, Beutels. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This study (and VV) is funded by the Research Foundation Flanders ( https://www.fwo.be/en/ ), FWO project number G0D5917N, award obtained by PB. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Identifying the key drivers of population health is a core subject in public health and health economics research. Between-country comparative research on the topic is challenging. In order to be relevant for policy, it requires disentangling different interrelated drivers of “good health”, each having different degrees of importance in different contexts.

“Good health”–physical and psychological, subjective and objective–can be defined and measured using a variety of approaches, depending on which aspect of health is the focus. A major distinction can be made between health measurements at the individual level or some aggregate level, such as a neighborhood, a region or a country. In view of this, a great diversity of specific research topics exists on the drivers of what constitutes individual or aggregate “good health”, including those focusing on health inequalities, the gender gap in longevity, and regional mortality and longevity differences.

The current scoping review focuses on determinants of population health. Stated as such, this topic is quite broad. Indeed, we are interested in the very general question of what methods have been used to make the most of increasingly available region or country-specific databases to understand the drivers of population health through inter-country comparisons. Existing reviews indicate that researchers thus far tend to adopt a narrower focus. Usually, attention is given to only one health outcome at a time, with further geographical and/or population [ 1 , 2 ] restrictions. In some cases, the impact of one or more interventions is at the core of the review [ 3 – 7 ], while in others it is the relationship between health and just one particular predictor, e.g., income inequality, access to healthcare, government mechanisms [ 8 – 13 ]. Some relatively recent reviews on the subject of social determinants of health [ 4 – 6 , 14 – 17 ] have considered a number of indicators potentially influencing health as opposed to a single one. One review defines “social determinants” as “the social, economic, and political conditions that influence the health of individuals and populations” [ 17 ] while another refers even more broadly to “the factors apart from medical care” [ 15 ].

In the present work, we aimed to be more inclusive, setting no limitations on the nature of possible health correlates, as well as making use of a multitude of commonly accepted measures of general population health. The goal of this scoping review was to document the state of the art in the recent published literature on determinants of population health, with a particular focus on the types of determinants selected and the methodology used. In doing so, we also report the main characteristics of the results these studies found. The materials collected in this review are intended to inform our (and potentially other researchers’) future analyses on this topic. Since the production of health is subject to the law of diminishing marginal returns, we focused our review on those studies that included countries where a high standard of wealth has been achieved for some time, i.e., high-income countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or Europe. Adding similar reviews for other country income groups is of limited interest to the research we plan to do in this area.

In view of its focus on data and methods, rather than results, a formal protocol was not registered prior to undertaking this review, but the procedure followed the guidelines of the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews [ 18 ].

We focused on multi-country studies investigating the potential associations between any aggregate level (region/city/country) determinant and general measures of population health (e.g., life expectancy, mortality rate).

Within the query itself, we listed well-established population health indicators as well as the six world regions, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO). We searched only in the publications’ titles in order to keep the number of hits manageable, and the ratio of broadly relevant abstracts over all abstracts in the order of magnitude of 10% (based on a series of time-focused trial runs). The search strategy was developed iteratively between the two authors and is presented in S1 Appendix . The search was performed by VV in PubMed and Web of Science on the 16 th of July, 2019, without any language restrictions, and with a start date set to the 1 st of January, 2013, as we were interested in the latest developments in this area of research.

Eligibility criteria

Records obtained via the search methods described above were screened independently by the two authors. Consistency between inclusion/exclusion decisions was approximately 90% and the 43 instances where uncertainty existed were judged through discussion. Articles were included subject to meeting the following requirements: (a) the paper was a full published report of an original empirical study investigating the impact of at least one aggregate level (city/region/country) factor on at least one health indicator (or self-reported health) of the general population (the only admissible “sub-populations” were those based on gender and/or age); (b) the study employed statistical techniques (calculating correlations, at the very least) and was not purely descriptive or theoretical in nature; (c) the analysis involved at least two countries or at least two regions or cities (or another aggregate level) in at least two different countries; (d) the health outcome was not differentiated according to some socio-economic factor and thus studied in terms of inequality (with the exception of gender and age differentiations); (e) mortality, in case it was one of the health indicators under investigation, was strictly “total” or “all-cause” (no cause-specific or determinant-attributable mortality).

Data extraction

The following pieces of information were extracted in an Excel table from the full text of each eligible study (primarily by VV, consulting with PB in case of doubt): health outcome(s), determinants, statistical methodology, level of analysis, results, type of data, data sources, time period, countries. The evidence is synthesized according to these extracted data (often directly reflected in the section headings), using a narrative form accompanied by a “summary-of-findings” table and a graph.

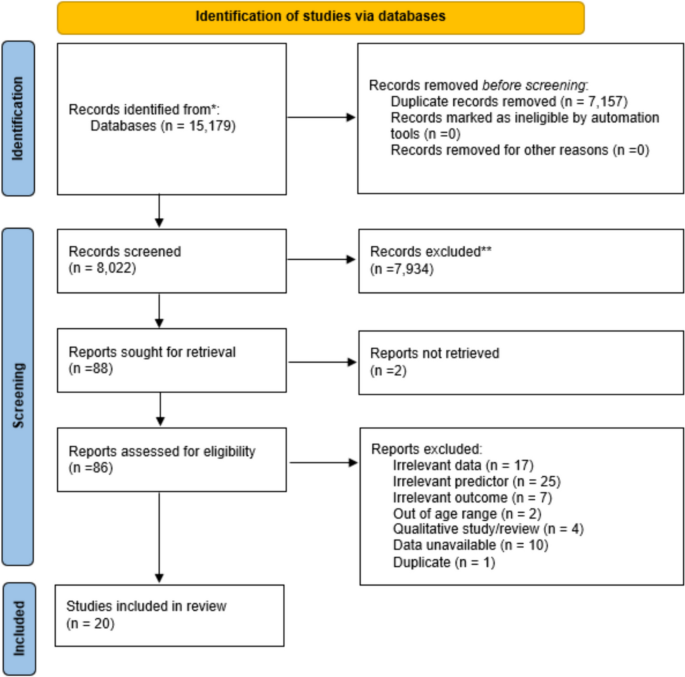

Search and selection

The initial yield contained 4583 records, reduced to 3686 after removal of duplicates ( Fig 1 ). Based on title and abstract screening, 3271 records were excluded because they focused on specific medical condition(s) or specific populations (based on morbidity or some other factor), dealt with intervention effectiveness, with theoretical or non-health related issues, or with animals or plants. Of the remaining 415 papers, roughly half were disqualified upon full-text consideration, mostly due to using an outcome not of interest to us (e.g., health inequality), measuring and analyzing determinants and outcomes exclusively at the individual level, performing analyses one country at a time, employing indices that are a mixture of both health indicators and health determinants, or not utilizing potential health determinants at all. After this second stage of the screening process, 202 papers were deemed eligible for inclusion. This group was further dichotomized according to level of economic development of the countries or regions under study, using membership of the OECD or Europe as a reference “cut-off” point. Sixty papers were judged to include high-income countries, and the remaining 142 included either low- or middle-income countries or a mix of both these levels of development. The rest of this report outlines findings in relation to high-income countries only, reflecting our own primary research interests. Nonetheless, we chose to report our search yield for the other income groups for two reasons. First, to gauge the relative interest in applied published research for these different income levels; and second, to enable other researchers with a focus on determinants of health in other countries to use the extraction we made here.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.g001

Health outcomes

The most frequent population health indicator, life expectancy (LE), was present in 24 of the 60 studies. Apart from “life expectancy at birth” (representing the average life-span a newborn is expected to have if current mortality rates remain constant), also called “period LE” by some [ 19 , 20 ], we encountered as well LE at 40 years of age [ 21 ], at 60 [ 22 ], and at 65 [ 21 , 23 , 24 ]. In two papers, the age-specificity of life expectancy (be it at birth or another age) was not stated [ 25 , 26 ].

Some studies considered male and female LE separately [ 21 , 24 , 25 , 27 – 33 ]. This consideration was also often observed with the second most commonly used health index [ 28 – 30 , 34 – 38 ]–termed “total”, or “overall”, or “all-cause”, mortality rate (MR)–included in 22 of the 60 studies. In addition to gender, this index was also sometimes broken down according to age group [ 30 , 39 , 40 ], as well as gender-age group [ 38 ].

While the majority of studies under review here focused on a single health indicator, 23 out of the 60 studies made use of multiple outcomes, although these outcomes were always considered one at a time, and sometimes not all of them fell within the scope of our review. An easily discernable group of indices that typically went together [ 25 , 37 , 41 ] was that of neonatal (deaths occurring within 28 days postpartum), perinatal (fetal or early neonatal / first-7-days deaths), and post-neonatal (deaths between the 29 th day and completion of one year of life) mortality. More often than not, these indices were also accompanied by “stand-alone” indicators, such as infant mortality (deaths within the first year of life; our third most common index found in 16 of the 60 studies), maternal mortality (deaths during pregnancy or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy), and child mortality rates. Child mortality has conventionally been defined as mortality within the first 5 years of life, thus often also called “under-5 mortality”. Nonetheless, Pritchard & Wallace used the term “child mortality” to denote deaths of children younger than 14 years [ 42 ].

As previously stated, inclusion criteria did allow for self-reported health status to be used as a general measure of population health. Within our final selection of studies, seven utilized some form of subjective health as an outcome variable [ 25 , 43 – 48 ]. Additionally, the Health Human Development Index [ 49 ], healthy life expectancy [ 50 ], old-age survival [ 51 ], potential years of life lost [ 52 ], and disability-adjusted life expectancy [ 25 ] were also used.

We note that while in most cases the indicators mentioned above (and/or the covariates considered, see below) were taken in their absolute or logarithmic form, as a—typically annual—number, sometimes they were used in the form of differences, change rates, averages over a given time period, or even z-scores of rankings [ 19 , 22 , 40 , 42 , 44 , 53 – 57 ].

Regions, countries, and populations

Despite our decision to confine this review to high-income countries, some variation in the countries and regions studied was still present. Selection seemed to be most often conditioned on the European Union, or the European continent more generally, and the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), though, typically, not all member nations–based on the instances where these were also explicitly listed—were included in a given study. Some of the stated reasons for omitting certain nations included data unavailability [ 30 , 45 , 54 ] or inconsistency [ 20 , 58 ], Gross Domestic Product (GDP) too low [ 40 ], differences in economic development and political stability with the rest of the sampled countries [ 59 ], and national population too small [ 24 , 40 ]. On the other hand, the rationales for selecting a group of countries included having similar above-average infant mortality [ 60 ], similar healthcare systems [ 23 ], and being randomly drawn from a social spending category [ 61 ]. Some researchers were interested explicitly in a specific geographical region, such as Eastern Europe [ 50 ], Central and Eastern Europe [ 48 , 60 ], the Visegrad (V4) group [ 62 ], or the Asia/Pacific area [ 32 ]. In certain instances, national regions or cities, rather than countries, constituted the units of investigation instead [ 31 , 51 , 56 , 62 – 66 ]. In two particular cases, a mix of countries and cities was used [ 35 , 57 ]. In another two [ 28 , 29 ], due to the long time periods under study, some of the included countries no longer exist. Finally, besides “European” and “OECD”, the terms “developed”, “Western”, and “industrialized” were also used to describe the group of selected nations [ 30 , 42 , 52 , 53 , 67 ].

As stated above, it was the health status of the general population that we were interested in, and during screening we made a concerted effort to exclude research using data based on a more narrowly defined group of individuals. All studies included in this review adhere to this general rule, albeit with two caveats. First, as cities (even neighborhoods) were the unit of analysis in three of the studies that made the selection [ 56 , 64 , 65 ], the populations under investigation there can be more accurately described as general urban , instead of just general. Second, oftentimes health indicators were stratified based on gender and/or age, therefore we also admitted one study that, due to its specific research question, focused on men and women of early retirement age [ 35 ] and another that considered adult males only [ 68 ].

Data types and sources

A great diversity of sources was utilized for data collection purposes. The accessible reference databases of the OECD ( https://www.oecd.org/ ), WHO ( https://www.who.int/ ), World Bank ( https://www.worldbank.org/ ), United Nations ( https://www.un.org/en/ ), and Eurostat ( https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat ) were among the top choices. The other international databases included Human Mortality [ 30 , 39 , 50 ], Transparency International [ 40 , 48 , 50 ], Quality of Government [ 28 , 69 ], World Income Inequality [ 30 ], International Labor Organization [ 41 ], International Monetary Fund [ 70 ]. A number of national databases were referred to as well, for example the US Bureau of Statistics [ 42 , 53 ], Korean Statistical Information Services [ 67 ], Statistics Canada [ 67 ], Australian Bureau of Statistics [ 67 ], and Health New Zealand Tobacco control and Health New Zealand Food and Nutrition [ 19 ]. Well-known surveys, such as the World Values Survey [ 25 , 55 ], the European Social Survey [ 25 , 39 , 44 ], the Eurobarometer [ 46 , 56 ], the European Value Survey [ 25 ], and the European Statistics of Income and Living Condition Survey [ 43 , 47 , 70 ] were used as data sources, too. Finally, in some cases [ 25 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 36 , 41 , 69 ], built-for-purpose datasets from previous studies were re-used.

In most of the studies, the level of the data (and analysis) was national. The exceptions were six papers that dealt with Nomenclature of Territorial Units of Statistics (NUTS2) regions [ 31 , 62 , 63 , 66 ], otherwise defined areas [ 51 ] or cities [ 56 ], and seven others that were multilevel designs and utilized both country- and region-level data [ 57 ], individual- and city- or country-level [ 35 ], individual- and country-level [ 44 , 45 , 48 ], individual- and neighborhood-level [ 64 ], and city-region- (NUTS3) and country-level data [ 65 ]. Parallel to that, the data type was predominantly longitudinal, with only a few studies using purely cross-sectional data [ 25 , 33 , 43 , 45 – 48 , 50 , 62 , 67 , 68 , 71 , 72 ], albeit in four of those [ 43 , 48 , 68 , 72 ] two separate points in time were taken (thus resulting in a kind of “double cross-section”), while in another the averages across survey waves were used [ 56 ].

In studies using longitudinal data, the length of the covered time periods varied greatly. Although this was almost always less than 40 years, in one study it covered the entire 20 th century [ 29 ]. Longitudinal data, typically in the form of annual records, was sometimes transformed before usage. For example, some researchers considered data points at 5- [ 34 , 36 , 49 ] or 10-year [ 27 , 29 , 35 ] intervals instead of the traditional 1, or took averages over 3-year periods [ 42 , 53 , 73 ]. In one study concerned with the effect of the Great Recession all data were in a “recession minus expansion change in trends”-form [ 57 ]. Furthermore, there were a few instances where two different time periods were compared to each other [ 42 , 53 ] or when data was divided into 2 to 4 (possibly overlapping) periods which were then analyzed separately [ 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 65 ]. Lastly, owing to data availability issues, discrepancies between the time points or periods of data on the different variables were occasionally observed [ 22 , 35 , 42 , 53 – 55 , 63 ].

Health determinants

Together with other essential details, Table 1 lists the health correlates considered in the selected studies. Several general categories for these correlates can be discerned, including health care, political stability, socio-economics, demographics, psychology, environment, fertility, life-style, culture, labor. All of these, directly or implicitly, have been recognized as holding importance for population health by existing theoretical models of (social) determinants of health [ 74 – 77 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.t001

It is worth noting that in a few studies there was just a single aggregate-level covariate investigated in relation to a health outcome of interest to us. In one instance, this was life satisfaction [ 44 ], in another–welfare system typology [ 45 ], but also gender inequality [ 33 ], austerity level [ 70 , 78 ], and deprivation [ 51 ]. Most often though, attention went exclusively to GDP [ 27 , 29 , 46 , 57 , 65 , 71 ]. It was often the case that research had a more particular focus. Among others, minimum wages [ 79 ], hospital payment schemes [ 23 ], cigarette prices [ 63 ], social expenditure [ 20 ], residents’ dissatisfaction [ 56 ], income inequality [ 30 , 69 ], and work leave [ 41 , 58 ] took center stage. Whenever variables outside of these specific areas were also included, they were usually identified as confounders or controls, moderators or mediators.

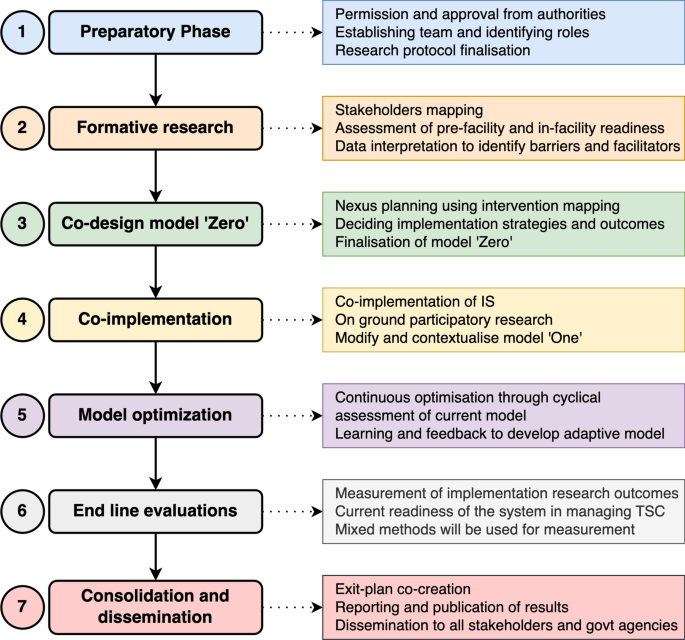

We visualized the combinations in which the different determinants have been studied in Fig 2 , which was obtained via multidimensional scaling and a subsequent cluster analysis (details outlined in S2 Appendix ). It depicts the spatial positioning of each determinant relative to all others, based on the number of times the effects of each pair of determinants have been studied simultaneously. When interpreting Fig 2 , one should keep in mind that determinants marked with an asterisk represent, in fact, collectives of variables.

Groups of determinants are marked by asterisks (see S1 Table in S1 Appendix ). Diminishing color intensity reflects a decrease in the total number of “connections” for a given determinant. Noteworthy pairwise “connections” are emphasized via lines (solid-dashed-dotted indicates decreasing frequency). Grey contour lines encircle groups of variables that were identified via cluster analysis. Abbreviations: age = population age distribution, associations = membership in associations, AT-index = atherogenic-thrombogenic index, BR = birth rate, CAPB = Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance, civilian-labor = civilian labor force, C-section = Cesarean delivery rate, credit-info = depth of credit information, dissatisf = residents’ dissatisfaction, distrib.orient = distributional orientation, EDU = education, eHealth = eHealth index at GP-level, exch.rate = exchange rate, fat = fat consumption, GDP = gross domestic product, GFCF = Gross Fixed Capital Formation/Creation, GH-gas = greenhouse gas, GII = gender inequality index, gov = governance index, gov.revenue = government revenues, HC-coverage = healthcare coverage, HE = health(care) expenditure, HHconsump = household consumption, hosp.beds = hospital beds, hosp.payment = hospital payment scheme, hosp.stay = length of hospital stay, IDI = ICT development index, inc.ineq = income inequality, industry-labor = industrial labor force, infant-sex = infant sex ratio, labor-product = labor production, LBW = low birth weight, leave = work leave, life-satisf = life satisfaction, M-age = maternal age, marginal-tax = marginal tax rate, MDs = physicians, mult.preg = multiple pregnancy, NHS = Nation Health System, NO = nitrous oxide emissions, PM10 = particulate matter (PM10) emissions, pop = population size, pop.density = population density, pre-term = pre-term birth rate, prison = prison population, researchE = research&development expenditure, school.ref = compulsory schooling reform, smoke-free = smoke-free places, SO = sulfur oxide emissions, soc.E = social expenditure, soc.workers = social workers, sugar = sugar consumption, terror = terrorism, union = union density, UR = unemployment rate, urban = urbanization, veg-fr = vegetable-and-fruit consumption, welfare = welfare regime, Wwater = wastewater treatment.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.g002

Distances between determinants in Fig 2 are indicative of determinants’ “connectedness” with each other. While the statistical procedure called for higher dimensionality of the model, for demonstration purposes we show here a two-dimensional solution. This simplification unfortunately comes with a caveat. To use the factor smoking as an example, it would appear it stands at a much greater distance from GDP than it does from alcohol. In reality however, smoking was considered together with alcohol consumption [ 21 , 25 , 26 , 52 , 68 ] in just as many studies as it was with GDP [ 21 , 25 , 26 , 52 , 59 ], five. To aid with respect to this apparent shortcoming, we have emphasized the strongest pairwise links. Solid lines connect GDP with health expenditure (HE), unemployment rate (UR), and education (EDU), indicating that the effect of GDP on health, taking into account the effects of the other three determinants as well, was evaluated in between 12 to 16 studies of the 60 included in this review. Tracing the dashed lines, we can also tell that GDP appeared jointly with income inequality, and HE together with either EDU or UR, in anywhere between 8 to 10 of our selected studies. Finally, some weaker but still worth-mentioning “connections” between variables are displayed as well via the dotted lines.

The fact that all notable pairwise “connections” are concentrated within a relatively small region of the plot may be interpreted as low overall “connectedness” among the health indicators studied. GDP is the most widely investigated determinant in relation to general population health. Its total number of “connections” is disproportionately high (159) compared to its runner-up–HE (with 113 “connections”), and then subsequently EDU (with 90) and UR (with 86). In fact, all of these determinants could be thought of as outliers, given that none of the remaining factors have a total count of pairings above 52. This decrease in individual determinants’ overall “connectedness” can be tracked on the graph via the change of color intensity as we move outwards from the symbolic center of GDP and its closest “co-determinants”, to finally reach the other extreme of the ten indicators (welfare regime, household consumption, compulsory school reform, life satisfaction, government revenues, literacy, research expenditure, multiple pregnancy, Cyclically Adjusted Primary Balance, and residents’ dissatisfaction; in white) the effects on health of which were only studied in isolation.

Lastly, we point to the few small but stable clusters of covariates encircled by the grey bubbles on Fig 2 . These groups of determinants were identified as “close” by both statistical procedures used for the production of the graph (see details in S2 Appendix ).

Statistical methodology

There was great variation in the level of statistical detail reported. Some authors provided too vague a description of their analytical approach, necessitating some inference in this section.

The issue of missing data is a challenging reality in this field of research, but few of the studies under review (12/60) explain how they dealt with it. Among the ones that do, three general approaches to handling missingness can be identified, listed in increasing level of sophistication: case-wise deletion, i.e., removal of countries from the sample [ 20 , 45 , 48 , 58 , 59 ], (linear) interpolation [ 28 , 30 , 34 , 58 , 59 , 63 ], and multiple imputation [ 26 , 41 , 52 ].

Correlations, Pearson, Spearman, or unspecified, were the only technique applied with respect to the health outcomes of interest in eight analyses [ 33 , 42 – 44 , 46 , 53 , 57 , 61 ]. Among the more advanced statistical methods, the family of regression models proved to be, by and large, predominant. Before examining this closer, we note the techniques that were, in a way, “unique” within this selection of studies: meta-analyses were performed (random and fixed effects, respectively) on the reduced form and 2-sample two stage least squares (2SLS) estimations done within countries [ 39 ]; difference-in-difference (DiD) analysis was applied in one case [ 23 ]; dynamic time-series methods, among which co-integration, impulse-response function (IRF), and panel vector autoregressive (VAR) modeling, were utilized in one study [ 80 ]; longitudinal generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were developed on two occasions [ 70 , 78 ]; hierarchical Bayesian spatial models [ 51 ] and special autoregressive regression [ 62 ] were also implemented.

Purely cross-sectional data analyses were performed in eight studies [ 25 , 45 , 47 , 50 , 55 , 56 , 67 , 71 ]. These consisted of linear regression (assumed ordinary least squares (OLS)), generalized least squares (GLS) regression, and multilevel analyses. However, six other studies that used longitudinal data in fact had a cross-sectional design, through which they applied regression at multiple time-points separately [ 27 , 29 , 36 , 48 , 68 , 72 ].

Apart from these “multi-point cross-sectional studies”, some other simplistic approaches to longitudinal data analysis were found, involving calculating and regressing 3-year averages of both the response and the predictor variables [ 54 ], taking the average of a few data-points (i.e., survey waves) [ 56 ] or using difference scores over 10-year [ 19 , 29 ] or unspecified time intervals [ 40 , 55 ].

Moving further in the direction of more sensible longitudinal data usage, we turn to the methods widely known among (health) economists as “panel data analysis” or “panel regression”. Most often seen were models with fixed effects for country/region and sometimes also time-point (occasionally including a country-specific trend as well), with robust standard errors for the parameter estimates to take into account correlations among clustered observations [ 20 , 21 , 24 , 28 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 52 , 59 , 60 , 63 , 66 , 69 , 73 , 79 , 81 , 82 ]. The Hausman test [ 83 ] was sometimes mentioned as the tool used to decide between fixed and random effects [ 26 , 49 , 63 , 66 , 73 , 82 ]. A few studies considered the latter more appropriate for their particular analyses, with some further specifying that (feasible) GLS estimation was employed [ 26 , 34 , 49 , 58 , 60 , 73 ]. Apart from these two types of models, the first differences method was encountered once as well [ 31 ]. Across all, the error terms were sometimes assumed to come from a first-order autoregressive process (AR(1)), i.e., they were allowed to be serially correlated [ 20 , 30 , 38 , 58 – 60 , 73 ], and lags of (typically) predictor variables were included in the model specification, too [ 20 , 21 , 37 , 38 , 48 , 69 , 81 ]. Lastly, a somewhat different approach to longitudinal data analysis was undertaken in four studies [ 22 , 35 , 48 , 65 ] in which multilevel–linear or Poisson–models were developed.

Regardless of the exact techniques used, most studies included in this review presented multiple model applications within their main analysis. None attempted to formally compare models in order to identify the “best”, even if goodness-of-fit statistics were occasionally reported. As indicated above, many studies investigated women’s and men’s health separately [ 19 , 21 , 22 , 27 – 29 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 45 , 50 , 51 , 64 , 65 , 69 , 82 ], and covariates were often tested one at a time, including other covariates only incrementally [ 20 , 25 , 28 , 36 , 40 , 50 , 55 , 67 , 73 ]. Furthermore, there were a few instances where analyses within countries were performed as well [ 32 , 39 , 51 ] or where the full time period of interest was divided into a few sub-periods [ 24 , 26 , 28 , 31 ]. There were also cases where different statistical techniques were applied in parallel [ 29 , 55 , 60 , 66 , 69 , 73 , 82 ], sometimes as a form of sensitivity analysis [ 24 , 26 , 30 , 58 , 73 ]. However, the most common approach to sensitivity analysis was to re-run models with somewhat different samples [ 39 , 50 , 59 , 67 , 69 , 80 , 82 ]. Other strategies included different categorization of variables or adding (more/other) controls [ 21 , 23 , 25 , 28 , 37 , 50 , 63 , 69 ], using an alternative main covariate measure [ 59 , 82 ], including lags for predictors or outcomes [ 28 , 30 , 58 , 63 , 65 , 79 ], using weights [ 24 , 67 ] or alternative data sources [ 37 , 69 ], or using non-imputed data [ 41 ].

As the methods and not the findings are the main focus of the current review, and because generic checklists cannot discern the underlying quality in this application field (see also below), we opted to pool all reported findings together, regardless of individual study characteristics or particular outcome(s) used, and speak generally of positive and negative effects on health. For this summary we have adopted the 0.05-significance level and only considered results from multivariate analyses. Strictly birth-related factors are omitted since these potentially only relate to the group of infant mortality indicators and not to any of the other general population health measures.

Starting with the determinants most often studied, higher GDP levels [ 21 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 43 , 48 , 52 , 58 , 60 , 66 , 67 , 73 , 79 , 81 , 82 ], higher health [ 21 , 37 , 47 , 49 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 68 , 72 , 82 ] and social [ 20 , 21 , 26 , 38 , 79 ] expenditures, higher education [ 26 , 39 , 52 , 62 , 72 , 73 ], lower unemployment [ 60 , 61 , 66 ], and lower income inequality [ 30 , 42 , 53 , 55 , 73 ] were found to be significantly associated with better population health on a number of occasions. In addition to that, there was also some evidence that democracy [ 36 ] and freedom [ 50 ], higher work compensation [ 43 , 79 ], distributional orientation [ 54 ], cigarette prices [ 63 ], gross national income [ 22 , 72 ], labor productivity [ 26 ], exchange rates [ 32 ], marginal tax rates [ 79 ], vaccination rates [ 52 ], total fertility [ 59 , 66 ], fruit and vegetable [ 68 ], fat [ 52 ] and sugar consumption [ 52 ], as well as bigger depth of credit information [ 22 ] and percentage of civilian labor force [ 79 ], longer work leaves [ 41 , 58 ], more physicians [ 37 , 52 , 72 ], nurses [ 72 ], and hospital beds [ 79 , 82 ], and also membership in associations, perceived corruption and societal trust [ 48 ] were beneficial to health. Higher nitrous oxide (NO) levels [ 52 ], longer average hospital stay [ 48 ], deprivation [ 51 ], dissatisfaction with healthcare and the social environment [ 56 ], corruption [ 40 , 50 ], smoking [ 19 , 26 , 52 , 68 ], alcohol consumption [ 26 , 52 , 68 ] and illegal drug use [ 68 ], poverty [ 64 ], higher percentage of industrial workers [ 26 ], Gross Fixed Capital creation [ 66 ] and older population [ 38 , 66 , 79 ], gender inequality [ 22 ], and fertility [ 26 , 66 ] were detrimental.

It is important to point out that the above-mentioned effects could not be considered stable either across or within studies. Very often, statistical significance of a given covariate fluctuated between the different model specifications tried out within the same study [ 20 , 49 , 59 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 73 , 80 , 82 ], testifying to the importance of control variables and multivariate research (i.e., analyzing multiple independent variables simultaneously) in general. Furthermore, conflicting results were observed even with regards to the “core” determinants given special attention, so to speak, throughout this text. Thus, some studies reported negative effects of health expenditure [ 32 , 82 ], social expenditure [ 58 ], GDP [ 49 , 66 ], and education [ 82 ], and positive effects of income inequality [ 82 ] and unemployment [ 24 , 31 , 32 , 52 , 66 , 68 ]. Interestingly, one study [ 34 ] differentiated between temporary and long-term effects of GDP and unemployment, alluding to possibly much greater complexity of the association with health. It is also worth noting that some gender differences were found, with determinants being more influential for males than for females, or only having statistically significant effects for male health [ 19 , 21 , 28 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 64 , 65 , 69 ].

The purpose of this scoping review was to examine recent quantitative work on the topic of multi-country analyses of determinants of population health in high-income countries.

Measuring population health via relatively simple mortality-based indicators still seems to be the state of the art. What is more, these indicators are routinely considered one at a time, instead of, for example, employing existing statistical procedures to devise a more general, composite, index of population health, or using some of the established indices, such as disability-adjusted life expectancy (DALE) or quality-adjusted life expectancy (QALE). Although strong arguments for their wider use were already voiced decades ago [ 84 ], such summary measures surface only rarely in this research field.

On a related note, the greater data availability and accessibility that we enjoy today does not automatically equate to data quality. Nonetheless, this is routinely assumed in aggregate level studies. We almost never encountered a discussion on the topic. The non-mundane issue of data missingness, too, goes largely underappreciated. With all recent methodological advancements in this area [ 85 – 88 ], there is no excuse for ignorance; and still, too few of the reviewed studies tackled the matter in any adequate fashion.

Much optimism can be gained considering the abundance of different determinants that have attracted researchers’ attention in relation to population health. We took on a visual approach with regards to these determinants and presented a graph that links spatial distances between determinants with frequencies of being studies together. To facilitate interpretation, we grouped some variables, which resulted in some loss of finer detail. Nevertheless, the graph is helpful in exemplifying how many effects continue to be studied in a very limited context, if any. Since in reality no factor acts in isolation, this oversimplification practice threatens to render the whole exercise meaningless from the outset. The importance of multivariate analysis cannot be stressed enough. While there is no “best method” to be recommended and appropriate techniques vary according to the specifics of the research question and the characteristics of the data at hand [ 89 – 93 ], in the future, in addition to abandoning simplistic univariate approaches, we hope to see a shift from the currently dominating fixed effects to the more flexible random/mixed effects models [ 94 ], as well as wider application of more sophisticated methods, such as principle component regression, partial least squares, covariance structure models (e.g., structural equations), canonical correlations, time-series, and generalized estimating equations.

Finally, there are some limitations of the current scoping review. We searched the two main databases for published research in medical and non-medical sciences (PubMed and Web of Science) since 2013, thus potentially excluding publications and reports that are not indexed in these databases, as well as older indexed publications. These choices were guided by our interest in the most recent (i.e., the current state-of-the-art) and arguably the highest-quality research (i.e., peer-reviewed articles, primarily in indexed non-predatory journals). Furthermore, despite holding a critical stance with regards to some aspects of how determinants-of-health research is currently conducted, we opted out of formally assessing the quality of the individual studies included. The reason for that is two-fold. On the one hand, we are unaware of the existence of a formal and standard tool for quality assessment of ecological designs. And on the other, we consider trying to score the quality of these diverse studies (in terms of regional setting, specific topic, outcome indices, and methodology) undesirable and misleading, particularly since we would sometimes have been rating the quality of only a (small) part of the original studies—the part that was relevant to our review’s goal.

Our aim was to investigate the current state of research on the very broad and general topic of population health, specifically, the way it has been examined in a multi-country context. We learned that data treatment and analytical approach were, in the majority of these recent studies, ill-equipped or insufficiently transparent to provide clarity regarding the underlying mechanisms of population health in high-income countries. Whether due to methodological shortcomings or the inherent complexity of the topic, research so far fails to provide any definitive answers. It is our sincere belief that with the application of more advanced analytical techniques this continuous quest could come to fruition sooner.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (prisma-scr) checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.s001

S1 Appendix.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.s002

S2 Appendix.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239031.s003

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 75. Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and Strategies to Promote Equity in Health. Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Future Studies; 1991.

- 76. Brunner E, Marmot M. Social Organization, Stress, and Health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson RG, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1999.

- 77. Najman JM. A General Model of the Social Origins of Health and Well-being. In: Eckersley R, Dixon J, Douglas B, editors. The Social Origins of Health and Well-being. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

- 85. Carpenter JR, Kenward MG. Multiple Imputation and its Application. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

- 86. Molenberghs G, Fitzmaurice G, Kenward MG, Verbeke G, Tsiatis AA. Handbook of Missing Data Methodology. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2014.

- 87. van Buuren S. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2018.

- 88. Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010.

- 89. Shayle R. Searle GC, Charles E. McCulloch. Variance Components: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992.

- 90. Agresti A. Foundations of Linear and Generalized Linear Models. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2015.

- 91. Leyland A. H. (Editor) HGE. Multilevel Modelling of Health Statistics: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2001.

- 92. Garrett Fitzmaurice MD, Geert Verbeke, Geert Molenberghs. Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2008.

- 93. Wolfgang Karl Härdle LS. Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2015.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

| Research method | How to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Control or manipulate an to measure its effect on a dependent variable. | To test whether an intervention can reduce procrastination in college students, you give equal-sized groups either a procrastination intervention or a comparable task. You compare self-ratings of procrastination behaviors between the groups after the intervention. | |

| Ask questions of a group of people in-person, over-the-phone or online. | You distribute with rating scales to first-year international college students to investigate their experiences of culture shock. | |

| (Systematic) observation | Identify a behavior or occurrence of interest and monitor it in its natural setting. | To study college classroom participation, you sit in on classes to observe them, counting and recording the prevalence of active and passive behaviors by students from different backgrounds. |

| Secondary research | Collect data that has been gathered for other purposes e.g., national surveys or historical records. | To assess whether attitudes towards climate change have changed since the 1980s, you collect relevant questionnaire data from widely available . |

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Archer Library

Quantitative research: literature review .

- Archer Library This link opens in a new window

- Research Resources handout This link opens in a new window

- Locating Books

- Library eBook Collections This link opens in a new window

- A to Z Database List This link opens in a new window

- Research & Statistics

- Literature Review Resources

- Citations & Reference

Exploring the literature review

Literature review model: 6 steps.

Adapted from The Literature Review , Machi & McEvoy (2009, p. 13).

Your Literature Review

Step 2: search, boolean search strategies, search limiters, ★ ebsco & google drive.

1. Select a Topic

"All research begins with curiosity" (Machi & McEvoy, 2009, p. 14)

Selection of a topic, and fully defined research interest and question, is supervised (and approved) by your professor. Tips for crafting your topic include:

- Be specific. Take time to define your interest.

- Topic Focus. Fully describe and sufficiently narrow the focus for research.

- Academic Discipline. Learn more about your area of research & refine the scope.

- Avoid Bias. Be aware of bias that you (as a researcher) may have.

- Document your research. Use Google Docs to track your research process.

- Research apps. Consider using Evernote or Zotero to track your research.

Consider Purpose

What will your topic and research address?

In The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students , Ridley presents that literature reviews serve several purposes (2008, p. 16-17). Included are the following points:

- Historical background for the research;

- Overview of current field provided by "contemporary debates, issues, and questions;"

- Theories and concepts related to your research;

- Introduce "relevant terminology" - or academic language - being used it the field;

- Connect to existing research - does your work "extend or challenge [this] or address a gap;"

- Provide "supporting evidence for a practical problem or issue" that your research addresses.

★ Schedule a research appointment

At this point in your literature review, take time to meet with a librarian. Why? Understanding the subject terminology used in databases can be challenging. Archer Librarians can help you structure a search, preparing you for step two. How? Contact a librarian directly or use the online form to schedule an appointment. Details are provided in the adjacent Schedule an Appointment box.

2. Search the Literature

Collect & Select Data: Preview, select, and organize

Archer Library is your go-to resource for this step in your literature review process. The literature search will include books and ebooks, scholarly and practitioner journals, theses and dissertations, and indexes. You may also choose to include web sites, blogs, open access resources, and newspapers. This library guide provides access to resources needed to complete a literature review.

Books & eBooks: Archer Library & OhioLINK

| Books | |

Databases: Scholarly & Practitioner Journals

Review the Library Databases tab on this library guide, it provides links to recommended databases for Education & Psychology, Business, and General & Social Sciences.

Expand your journal search; a complete listing of available AU Library and OhioLINK databases is available on the Databases A to Z list . Search the database by subject, type, name, or do use the search box for a general title search. The A to Z list also includes open access resources and select internet sites.

Databases: Theses & Dissertations

Review the Library Databases tab on this guide, it includes Theses & Dissertation resources. AU library also has AU student authored theses and dissertations available in print, search the library catalog for these titles.

Did you know? If you are looking for particular chapters within a dissertation that is not fully available online, it is possible to submit an ILL article request . Do this instead of requesting the entire dissertation.

Newspapers: Databases & Internet

Consider current literature in your academic field. AU Library's database collection includes The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Wall Street Journal . The Internet Resources tab in this guide provides links to newspapers and online journals such as Inside Higher Ed , COABE Journal , and Education Week .

The Chronicle of Higher Education has the nation’s largest newsroom dedicated to covering colleges and universities. Source of news, information, and jobs for college and university faculty members and administrators

The Chronicle features complete contents of the latest print issue; daily news and advice columns; current job listings; archive of previously published content; discussion forums; and career-building tools such as online CV management and salary databases. Dates covered: 1970-present.

Offers in-depth coverage of national and international business and finance as well as first-rate coverage of hard news--all from America's premier financial newspaper. Covers complete bibliographic information and also subjects, companies, people, products, and geographic areas.

Comprehensive coverage back to 1984 is available from the world's leading financial newspaper through the ProQuest database.

Newspaper Source provides cover-to-cover full text for hundreds of national (U.S.), international and regional newspapers. In addition, it offers television and radio news transcripts from major networks.

Provides complete television and radio news transcripts from CBS News, CNN, CNN International, FOX News, and more.

Search Strategies & Boolean Operators

There are three basic boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

Used with your search terms, boolean operators will either expand or limit results. What purpose do they serve? They help to define the relationship between your search terms. For example, using the operator AND will combine the terms expanding the search. When searching some databases, and Google, the operator AND may be implied.

Overview of boolean terms

| Search results will contain of the terms. | Search results will contain of the search terms. | Search results the specified search term. |

| Search for ; you will find items that contain terms. | Search for ; you will find items that contain . | Search for online education: you will find items that contain . |

| connects terms, limits the search, and will reduce the number of results returned. | redefines connection of the terms, expands the search, and increases the number of results returned. | excludes results from the search term and reduces the number of results. |

|

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

About the example: Boolean searches were conducted on November 4, 2019; result numbers may vary at a later date. No additional database limiters were set to further narrow search returns.

Database Search Limiters

Database strategies for targeted search results.

Most databases include limiters, or additional parameters, you may use to strategically focus search results. EBSCO databases, such as Education Research Complete & Academic Search Complete provide options to:

- Limit results to full text;

- Limit results to scholarly journals, and reference available;

- Select results source type to journals, magazines, conference papers, reviews, and newspapers

- Publication date

Keep in mind that these tools are defined as limiters for a reason; adding them to a search will limit the number of results returned. This can be a double-edged sword. How?

- If limiting results to full-text only, you may miss an important piece of research that could change the direction of your research. Interlibrary loan is available to students, free of charge. Request articles that are not available in full-text; they will be sent to you via email.

- If narrowing publication date, you may eliminate significant historical - or recent - research conducted on your topic.

- Limiting resource type to a specific type of material may cause bias in the research results.

Use limiters with care. When starting a search, consider opting out of limiters until the initial literature screening is complete. The second or third time through your research may be the ideal time to focus on specific time periods or material (scholarly vs newspaper).

★ Truncating Search Terms

Expanding your search term at the root.

Truncating is often referred to as 'wildcard' searching. Databases may have their own specific wildcard elements however, the most commonly used are the asterisk (*) or question mark (?). When used within your search. they will expand returned results.

Asterisk (*) Wildcard

Using the asterisk wildcard will return varied spellings of the truncated word. In the following example, the search term education was truncated after the letter "t."

| Original Search | |

| adult education | adult educat* |

| Results included: educate, education, educator, educators'/educators, educating, & educational |

Explore these database help pages for additional information on crafting search terms.

- EBSCO Connect: Basic Searching with EBSCO

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Boolean Operators

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Wildcards and Truncation Symbols

- ProQuest Help: Search Tips

- ERIC: How does ERIC search work?

★ EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

Tips for saving research directly to Google drive.

Researching in an EBSCO database?

It is possible to save articles (PDF and HTML) and abstracts in EBSCOhost databases directly to Google drive. Select the Google Drive icon, authenticate using a Google account, and an EBSCO folder will be created in your account. This is a great option for managing your research. If documenting your research in a Google Doc, consider linking the information to actual articles saved in drive.

EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

EBSCOHost Databases & Google Drive: Managing your Research

This video features an overview of how to use Google Drive with EBSCO databases to help manage your research. It presents information for connecting an active Google account to EBSCO and steps needed to provide permission for EBSCO to manage a folder in Drive.

About the Video: Closed captioning is available, select CC from the video menu. If you need to review a specific area on the video, view on YouTube and expand the video description for access to topic time stamps. A video transcript is provided below.

- EBSCOhost Databases & Google Scholar

Defining Literature Review

What is a literature review.

A definition from the Online Dictionary for Library and Information Sciences .

A literature review is "a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works" (Reitz, 2014).

A systemic review is "a literature review focused on a specific research question, which uses explicit methods to minimize bias in the identification, appraisal, selection, and synthesis of all the high-quality evidence pertinent to the question" (Reitz, 2014).

Recommended Reading

About this page

EBSCO Connect [Discovery and Search]. (2022). Searching with boolean operators. Retrieved May, 3, 2022 from https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

EBSCO Connect [Discover and Search]. (2022). Searching with wildcards and truncation symbols. Retrieved May 3, 2022; https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

Machi, L.A. & McEvoy, B.T. (2009). The literature review . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press:

Reitz, J.M. (2014). Online dictionary for library and information science. ABC-CLIO, Libraries Unlimited . Retrieved from https://www.abc-clio.com/ODLIS/odlis_A.aspx

Ridley, D. (2008). The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Archer Librarians

Schedule an appointment.

Contact a librarian directly (email), or submit a request form. If you have worked with someone before, you can request them on the form.

- ★ Archer Library Help • Online Reqest Form

- Carrie Halquist • Reference & Instruction

- Jessica Byers • Reference & Curation

- Don Reams • Corrections Education & Reference

- Diane Schrecker • Education & Head of the IRC

- Tanaya Silcox • Technical Services & Business

- Sarah Thomas • Acquisitions & ATS Librarian

- << Previous: Research & Statistics

- Next: Literature Review Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ashland.edu/quantitative

Archer Library • Ashland University © Copyright 2023. An Equal Opportunity/Equal Access Institution.

Emotion Regulation and Academic Burnout Among Youth: a Quantitative Meta-analysis

- META-ANALYSIS

- Open access

- Published: 10 September 2024

- Volume 36 , article number 106 , ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ioana Alexandra Iuga ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9152-2004 1 , 2 &

- Oana Alexandra David ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8706-1778 2 , 3

Emotion regulation (ER) represents an important factor in youth’s academic wellbeing even in contexts that are not characterized by outstanding levels of academic stress. Effective ER not only enhances learning and, consequentially, improves youths’ academic achievement, but can also serve as a protective factor against academic burnout. The relationship between ER and academic burnout is complex and varies across studies. This meta-analysis examines the connection between ER strategies and student burnout, considering a series of influencing factors. Data analysis involved a random effects meta-analytic approach, assessing heterogeneity and employing multiple methods to address publication bias, along with meta-regression for continuous moderating variables (quality, female percentage and mean age) and subgroup analyses for categorical moderating variables (sample grade level). According to our findings, adaptive ER strategies are negatively associated with overall burnout scores, whereas ER difficulties are positively associated with burnout and its dimensions, comprising emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of efficacy. These results suggest the nuanced role of ER in psychopathology and well-being. We also identified moderating factors such as mean age, grade level and gender composition of the sample in shaping these associations. This study highlights the need for the expansion of the body of literature concerning ER and academic burnout, that would allow for particularized analyses, along with context-specific ER research and consistent measurement approaches in understanding academic burnout. Despite methodological limitations, our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of ER's intricate relationship with student burnout, guiding future research in this field.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transitional stages of late adolescence and early adulthood are characterized by significant physiological and psychological changes, including increased stress (Matud et al., 2020 ). Academic stress among students has long been studied in various samples, most of them focusing on university students (Bedewy & Gabriel, 2015 ; Córdova Olivera et al., 2023 ; Hystad et al., 2009 ) and, more recently, high school (Deb et al., 2015 ) and middle school students (Luo et al., 2020 ). Further, studies report an exacerbation of academic stress and mental health difficulties in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Guessoum et al., 2020 ), with children facing additional challenges that affect their academic well-being, such as increasing workloads, influences from the family, and the issue of decreasing financial income (Ibda et al., 2023 ; Yang et al., 2021 ). For youth to maintain their well-being in stressful academic settings, emotion regulation (ER) has been identified as an important factor (Santos Alves Peixoto et al., 2022 ; Yildiz, 2017 ; Zahniser & Conley, 2018 ).

Emotion regulation, referring to”the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express their emotions” (Gross, 1998b ), represents an important factor in youth’s academic well-being even in contexts that are not characterized by outstanding levels of stress. Emotion regulation strategies promote more efficient learning and, consequentially, improve youth’s academic achievement and motivation (Asareh et al., 2022 ; Davis & Levine, 2013 ), discourage academic procrastination (Mohammadi Bytamar et al., 2020 ), and decrease the chances of developing emotional problems such as burnout (Narimanj et al., 2021 ) and anxiety (Shahidi et al., 2017 ).

Approaches to Emotion Regulation

Numerous theories have been proposed to elucidate the process underlying the emergence and progression of emotional regulation (Gross, 1998a , 1998b ; Koole, 2009 ; Larsen, 2000 ; Parkinson & Totterdell, 1999 ). One prominent approach, developed by Gross ( 2015 ), refers to the process model of emotion regulation, which lays out the sequential actions people take to regulate their emotions during the emotion-generative process. These steps involve situation selection, situation modification, attentional deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation. The kind and timing of the emotion regulation strategies people use, according to this paradigm, influence the specific emotions people experience and express.

Recent theories of emotion regulation propose two separate, yet interconnected approaches: ER abilities and ER strategies. ER abilities are considered a higher-order process that guides the type of ER strategy an individual uses in the context of an emotion-generative circumstance. Further, ER strategies are considered factors that can also influence ER abilities, forming a bidirectional relationship (Tull & Aldao, 2015 ). Researchers use many definitions and classifications of emotion regulation, however, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that there are notable similarities across these concepts. While there are many models of emotion regulation, it's important to keep from seeing them as competing or incompatible since each one represents a unique and important aspect of the multifaceted concept of emotion regulation.

Emotion Regulation and Emotional Problems

The connection between ER strategies and psychopathology is intricate and multifaceted. While some researchers propose that ER’s effectiveness is context-dependent (Kobylińska & Kusev, 2019 ; Troy et al., 2013 ), several ER strategies have long been attested as adaptive or maladaptive. This body of work suggests that certain emotion regulation strategies (such as avoidance and expressive suppression) demonstrate, based on findings from experimental studies, inefficacy in altering affect and appear to be linked to higher levels of psychological symptoms. These strategies have been categorized as ER difficulties. In contrast, alternative emotion regulation strategies (such as reappraisal and acceptance) have demonstrated effectiveness in modifying affect within controlled laboratory environments, exhibiting a negative association with clinical symptoms. As a result, these strategies have been characterized as potentially adaptive (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012a , 2012b ; Aldao et al., 2010 ; Gross, 2013 ; Webb et al., 2012 ).

A long line of research highlights the divergent impact of putatively maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies on psychopathology and overall well-being (Gross & Levenson, 1993 ; Gross, 1998a ). Increased negative affect, increased physiological reactivity, memory problems (Richards et al., 2003 ), a decline in functional behavior (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2011 ), and a decline in social support (Séguin & MacDonald, 2018 ) are just a few of the negative effects that have consistently been linked to emotional regulation difficulties, which include but are not limited to the use of avoidance, suppression, rumination, and self-blame strategies. Additionally, a wide range of mental problems, such as depression (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008 ), anxiety disorders (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006a , 2006b ; Mennin et al., 2007 ), eating disorders (Prefit et al., 2019 ), and borderline personality disorder (Lynch et al., 2007 ; Neacsiu et al., 2010 ) are connected to self-reports of using these strategies.

Conversely, putatively adaptive strategies, including acceptance, problem-solving, and cognitive reappraisal, have consistently yielded beneficial outcomes in experimental studies. These outcomes encompass reductions in negative emotional responses, enhancements in interpersonal relationships, increased pain tolerance, reductions in physiological reactivity, and lower levels of psychopathological symptoms (Aldao et al., 2010 ; Goldin et al., 2008 ; Hayes et al., 1999 ; Richards & Gross, 2000 ).

Notably, despite the fact that therapeutic techniquest for enhancing the use of adaptive ER strategies are core elements of many therapeutic approaches, from traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to more recent third-wave interventions (Beck, 1976 ; Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008 ; Linehan, 1993 ; Roemer et al., 2008 ; Segal et al., 2002 ), the association between ER difficulties and psychopathology frequently show a stronger positive correlation compared to the inverse negative association with adaptive ER strategies, as highlighted by Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema ( 2012a ).

Pines & Aronson ( 1988 ) characterize burnout that arises in the workplace context as a state wherein individuals encounter emotional challenges, such as experiencing fatigue and physical exhaustion due to heightened task demands. Recently, driven by the rationale that schools are the environments where students engage in significant work, the concept of burnout has been extended to educational contexts (Salmela-Aro, 2017 ; Salmela-Aro & Tynkkynen, 2012 ; Walburg, 2014 ). Academic burnout is defined as a syndrome comprising three dimensions: exhaustion stemming from school demands, a cynical and detached attitude toward one's academic environment, and feelings of inadequacy as a student (Salmela-Aro et al., 2004 ; Schaufeli et al., 2002 ).

School burnout has quickly garnered international attention, despite its relatively recent emergence, underscoring its relevance across multiple nations (Herrmann et al., 2019 ; May et al., 2015 ; Meylan et al., 2015 ; Yang & Chen, 2016 ). Similar to other emotional difficulties, it has been observed among students from various educational systems and academic policies, suggesting that this phenomenon transcends cultural and geographical boundaries (Walburg, 2014 ).

The link between ER and school burnout can be understood through Gross's ( 1998a ) process model of emotion regulation. This model suggests that an individual's emotional responses are influenced by their ER strategies, which are adaptive or maladaptive reactions to stressors like academic pressure. Given that academic stress greatly influences school burnout (Jiang et al., 2021 ; Nikdel et al., 2019 ), the ER strategies students use to manage this stress may impact their likelihood of experiencing burnout. In essence, whether a student employs efficient ER strategies or encounters ER difficulties could influence their susceptibility to school burnout.