You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Thanks for signing up as a global citizen. In order to create your account we need you to provide your email address. You can check out our Privacy Policy to see how we safeguard and use the information you provide us with. If your Facebook account does not have an attached e-mail address, you'll need to add that before you can sign up.

This account has been deactivated.

Please contact us at [email protected] if you would like to re-activate your account.

Lack of access to education is a major predictor of passing poverty from one generation to the next, and receiving an education is one of the top ways to achieve financial stability.

In other words: education and poverty are directly linked.

Increasing access to education can equalize communities, improve the overall health and longevity of a society , and help save the planet .

The problem is that about 258 million children and youth are out of school around the world, according to UNESCO data released in 2018.

Children do not attend school for many reasons — but they all stem from poverty.

Here are all the statistics, facts, and answers to questions you might have that shed light on the connection between poverty and education.

How does poverty affect education?

Families living in poverty often have to choose between sending their child to school or providing other basic needs. Even if families do not have to pay tuition fees, school comes with the added costs of uniforms, books, supplies, and/or exam fees.

Countries across sub-Saharan Africa, where the world’s poorest children live, have made a concerted effort to abolish school fees . While the ratio of students completing lower secondary school increased in the region from 23% in 1990 to 42% in 2014, enrollment is low compared to the 75% global ratio. School remains too expensive for the poorest families. Some children are forced to stay at home doing chores or need to work. In other places, especially in crisis and conflict areas with destroyed infrastructure and limited resources, unaffordable private schools are sometimes the only option .

Why does poverty stop girls from going to school?

Poverty is the most important factor that determines whether or not a girl can access education, according to the World Bank. If families cannot afford the costs of school, they are more likely to send boys than girls. Around 15 million girls will never get the chance to attend school, compared to 10 million boys.

Read More: These Are the Top 10 Best and Worst Countries for Education in 2016

Gender inequality is more prevalent in low-income countries. Women often perform more unpaid work, have fewer assets, are exposed to gender-based violence, and are more likely to be forced into early marriage, all limiting their ability to fully participate in society and benefit from economic growth.

When girls face barriers to education early on, it is difficult for them to recover. Child marriage is one of the most common reasons a girl might stop going to school. More than 650 million women globally have already married under the age of 18. For families experiencing financial hardship, child marriage reduces their economic burden , but it ends up being more difficult for girls to gain financial independence if they are unable to access a quality education.

Lack of access to adequate menstrual hygiene management also stops many girls from attending school. Some girls cannot afford to buy sanitary products or they do not have access to clean water and sanitation to clean themselves and prevent disease. If safety is a concern due to lack of separate bathrooms, girls will stay home from school to avoid putting themselves at risk of sexual assault or harassment.

Read More: 10 Barriers to Education Around the World

An educated girl is not only likely to increase her personal earning potential but can help reduce poverty in her community, too.

“Educated girls have fewer, healthier, and better-educated children,” according to the Global Partnership for Education.

When countries invest in girls’ education, it sees an increase in female leaders, lower levels of population growth, and a reduction of contributions to climate change.

Can education help break the cycle of poverty?

Education promotes economic growth because it provides skills that increase employment opportunities and income. Nearly 60 million people could escape poverty if all adults had just two more years of schooling, and 420 million people could be lifted out of poverty if all adults completed secondary education, according to UNESCO.

Education increases earnings by roughly 10% per each additional year of schooling. For each $1 invested in an additional year of schooling, earnings increase by $5 in low-income countries and $2.5 in lower-middle income countries.

Read More: 264 Million Children Are Denied Access To Education, New Report Says

Education reduces many issues that stop people from living healthy lives, including infant and maternal deaths, stunting, infant and maternal deaths, vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, and violence.

How can we end extreme poverty through education?

There are more children enrolled in school than ever before — developing countries reached a 91% enrollment rate in 2015 — but we must fully close the gap.

World leaders gathered at the United Nations headquarters to address the disparity in 2015 and set 17 Global Goals to end extreme poverty by 2030. Global Goal 4: Quality Education aims to "end poverty in all its forms everywhere."

Read More: How We Can Be the Generation to End Extreme Poverty

The first step to achieving quality education for all is acknowledging that it is a vital part of sustainable development. Citizens, governments, corporations, and philanthropists all have an important role to play. Learn how to ensure global access to education to end poverty by taking action here .

Global Citizen Explains

Defeat Poverty

Understanding How Poverty is the Main Barrier to Education

Feb. 7, 2020

About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

How does education affect poverty?

For starters, it can help end it.

Aug 10, 2023

Access to high-quality primary education and supporting child well-being is a globally-recognized solution to the cycle of poverty. This is, in part, because it also addresses many of the other issues that keep communities vulnerable.

Education is often referred to as the great equalizer: It can open the door to jobs, resources, and skills that help a person not only survive, but thrive. In fact, according to UNESCO, if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills (nothing else), an estimated 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. If all adults completed secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

At its core, a quality education supports a child’s developing social, emotional, cognitive, and communication skills. Children who attend school also gain knowledge and skills, often at a higher level than those who aren’t in the classroom. They can then use these skills to earn higher incomes and build successful lives.

Here’s more on seven of the key ways that education affects poverty.

Go to the head of the class

Get more information on Concern's education programs — and the other ways we're ending poverty — delivered to your inbox.

1. Education is linked to economic growth

Education is the best way out of poverty in part because it is strongly linked to economic growth. A 2021 study co-published by Stanford University and Munich’s Ludwig Maximilian University shows us that, between 1960 and 2000, 75% of the growth in gross domestic product around the world was linked to increased math and science skills.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] rowth rate is extraordinarily strong,” the study’s authors conclude. This is just one of the most recent studies linking education and economic growth that have been published since 1990.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] growth rate is extraordinarily strong.” — Education and Economic Growth (2021 study by Stanford University and the University of Munich)

2. Universal education can fight inequality

A 2019 Oxfam report says it best: “Good-quality education can be liberating for individuals, and it can act as a leveler and equalizer within society.”

Poverty thrives in part on inequality. All types of systemic barriers (including physical ability, religion, race, and caste) serve as compound interest against a marginalization that already accrues most for those living in extreme poverty. Education is a basic human right for all, and — when tailored to the unique needs of marginalized communities — can be used as a lever against some of the systemic barriers that keep certain groups of people furthest behind.

For example, one of the biggest inequalities that fuels the cycle of poverty is gender. When gender inequality in the classroom is addressed, this has a ripple effect on the way women are treated in their communities. We saw this at work in Afghanistan , where Concern developed a Community-Based Education program that allowed students in rural areas to attend classes closer to home, which is especially helpful for girls.

Four ways that girls’ education can change the world

Gender discrimination is one of the many barriers to education around the world. That’s a situation we need to change.

3. Education is linked to lower maternal and infant mortality rates

Speaking of women, education also means healthier mothers and children. Examining 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, researchers from the World Bank and International Center for Research on Women found that educated women tend to have fewer children and have them later in life. This generally leads to better outcomes for both the mother and her kids, with safer pregnancies and healthier newborns.

A 2017 report shows that the country’s maternal mortality rate had declined by more than 70% in the last 25 years, approximately the same amount of time that an amendment to compulsory schooling laws took place in 1993. Ensuring that girls had more education reduced the likelihood of maternal health complications, in some cases by as much as 29%.

4. Education also lowers stunting rates

Children also benefit from more educated mothers. Several reports have linked education to lowered stunting , one of the side effects of malnutrition. Preventing stunting in childhood can limit the risks of many developmental issues for children whose height — and potential — are cut short by not having enough nutrients in their first few years.

In Bangladesh , one study showed a 50.7% prevalence for stunting among families. However, greater maternal education rates led to a 4.6% decrease in the odds of stunting; greater paternal education reduced those rates by 2.9%-5.4%. A similar study in Nairobi, Kenya confirmed this relationship: Children born to mothers with some secondary education are 29% less likely to be stunted.

What is stunting?

Stunting is a form of impaired growth and development due to malnutrition that threatens almost 25% of children around the world.

5. Education reduces vulnerability to HIV and AIDS…

In 2008, researchers from Harvard University, Imperial College London, and the World Bank wrote : “There is a growing body of evidence that keeping girls in school reduces their risk of contracting HIV. The relationship between educational attainment and HIV has changed over time, with educational attainment now more likely to be associated with a lower risk of HIV infection than earlier in the epidemic.”

Since then, that correlation has only grown stronger. The right programs in schools not only reduce the likelihood of young people contracting HIV or AIDS, but also reduce the stigmas held against people living with HIV and AIDS.

6. …and vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change

As the number of extreme weather events increases due to climate change, education plays a critical role in reducing vulnerability and risk to these events. A 2014 issue of the journal Ecology and Society states: “It is found that highly educated individuals are better aware of the earthquake risk … and are more likely to undertake disaster preparedness.… High risk awareness associated with education thus could contribute to vulnerability reduction behaviors.”

The authors of the article went on to add that educated people living through a natural disaster often have more of a financial safety net to offset losses, access to more sources of information to prepare for a disaster, and have a wider social network for mutual support.

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to education — and growing

Last August, UNICEF reported that half of the world’s 2.2 billion children are at “extremely high risk” for climate change, including its impact on education. Here’s why.

7. Education reduces violence at home and in communities

The same World Bank and ICRW report that showed the connection between education and maternal health also reveals that each additional year of secondary education reduced the chances of child marriage — defined as being married before the age of 18. Because educated women tend to marry later and have fewer children later in life, they’re also less likely to suffer gender-based violence , especially from their intimate partner.

Girls who receive a full education are also more likely to understand the harmful aspects of traditional practices like FGM , as well as their rights and how to stand up for them, at home and within their community.

Fighting FGM in Kenya: A daughter's bravery and a mother's love

Marsabit is one of those areas of northern Kenya where FGM has been the rule rather than the exception. But 12-year-old student Boti Ali had other plans.

Education for all: Concern’s approach

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. Last year, our work to promote education for all reached over 676,000 children. Over half of those students were female.

We integrate our education programs into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Concern has brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers.

More on how education affects poverty

6 Benefits of literacy in the fight against poverty

Child marriage and education: The blackboard wins over the bridal altar

Project Profile

Right to Learn

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

A World of Hardship: Deep Poverty and the Struggle for Educational Equity

This post is part of LPI's Learning in the Time of COVID-19 blog series, which explores evidence-based and equity-focused strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity.

One day you get out there and actually see where the children you serve on a daily basis come from. Several teachers came back after delivering food and broke down in tears telling me what they saw. A student was living in a home with no roof; they’ve got a tarp for a roof kept on by bricks and tires. Homes didn’t have doors. —Principal of a rural high-poverty elementary school

As this quote powerfully conveys, families living in deep poverty face profound material, social, and emotional hardships. Households in deep poverty suffer from food shortages, unemployment, unstable housing, inadequate medical care , electrical shutoffs, and isolation.

Children living in households in deep poverty are often “invisible” to more affluent community members—and likely to many educators as well. Too often, the plight of students living in deep poverty is subsumed under the broad definition of poverty, which does not reveal the unique hardships that are endured by those families and children with virtually no material resources . For those of us who believe in educational equity, making the invisible visible is the first step in overcoming deep disadvantage.

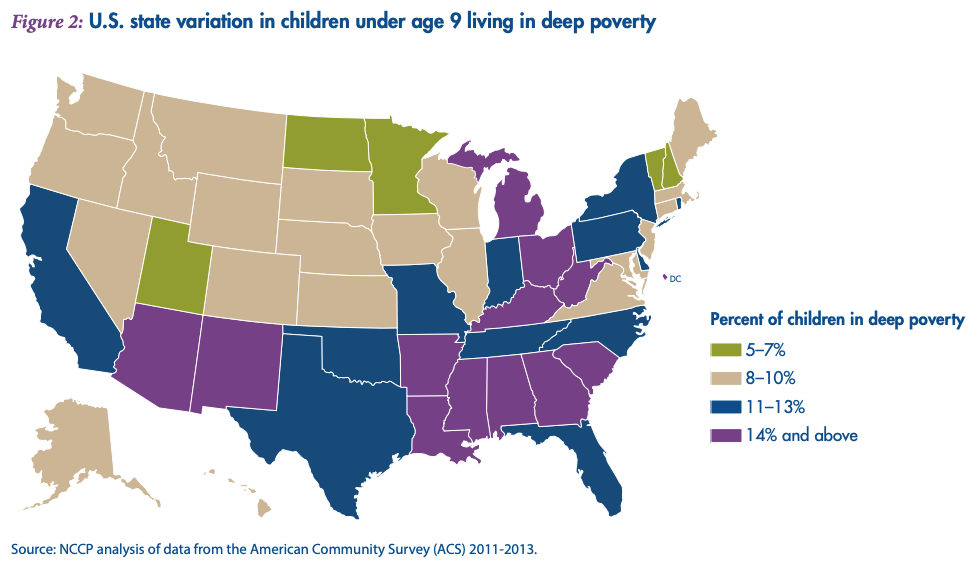

The U.S. Census Bureau defines deep poverty as living in a household with total cash income that is below 50% of the poverty threshold. As the National Center for Children in Poverty map below indicates, no state is without children living in deep poverty. Although the percentage varies considerably across states, all states have at least 5% of their children living far below the poverty line. In total, more than 5 million children in the United States live in deep poverty, including nearly 1 in 5 Black children under the age of 5.

With the explosion of the health and economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, households living in deep poverty have been pushed to the edge of survival: Nearly 4 in 10 Black and Latino households with children are struggling to feed their families . These numbers will no doubt grow as job losses mount, as do the numbers of children and adults of color who are contracting—and, in a disproportionate number of cases, dying from—COVID-19.

Why Deep Poverty Matters for Educators

Recently, Stanford researcher Sean Reardon and his colleagues conducted a national study on racial segregation and achievement gaps. In describing the findings he noted, “While racial segregation is important, it’s not the race of one’s classmates that matters, per se. It’s the fact that in America today, racial segregation brings with it very unequal concentrations of students in high- and low-poverty schools.” Another recent study of poverty and its effects on learning determined that levels of poverty matter in the abilities of students to succeed in school. According to the authors, “The experiences of children living in families with incomes just below the poverty line are likely quite different from those living in extreme poverty. Parents’ struggles to provide sufficient food and shelter for children may affect child academic achievement.”

The authors go on to note that the “depth of the poverty” matters both for the day-to-day life of students and families, and for public policy. “To determine appropriate subsidy levels and the types of services needed by children and families, policymakers need detailed data about the depth of family poverty. Studies have shown that simply classifying people as ‘in poverty’ or ‘not in poverty’ is not sufficient. The diversity in access to economic resources due to the depth of poverty helps explain the gaps in family investment in children’s education.”

The impact of poverty on children’s ability to learn is profound and occurs at an early age. A recent study of the neurological effects of deep poverty on young children’s development found that “poverty is tied to structural differences in several areas of the brain associated with school readiness skills, with the largest influence observed among children from the poorest households…. As much as 20% of the gap in test scores could be explained by maturational lags in the frontal and temporal lobes.” These effects were found to be associated with the consequences of living in deep poverty at an early age, some of which include premature and low-birthweight babies; poor nutrition and living without sufficient food; exposure to toxins, such as lead paint or contaminated drinking water; and lack of access to early learning opportunities.

If we are to educate the whole child , regardless of their family’s income, it is essential to provide an array of academic and social services that ensures that equity of opportunity reaches those students living in deep poverty.

The Importance of Accurately Determining Eligibility for Increased Services

In May 2020, the Learning Policy Institute published Measuring Student Socioeconomic Status: Toward a Comprehensive Approach . This report analyzes the limitations of the current methods used by school systems for measuring students’ socioeconomic status for purposes of allocating resources to meet their needs. Noting the limitations of determining a student’s level of poverty by her or his eligibility for free and reduced-price lunch—even when this measure is enhanced through direct certification of eligibility for other poverty-related programs—the report concludes that the development of new student poverty measures is urgently needed.

Blog Series: Learning in the Time of COVID-19

This blog series explores strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity. View all blogs >

The report also notes that researchers have suggested alternative measures of student poverty, some of which include parental education, student mobility, and community income as proxy measures. These strategies, however, do not appear to be capable of capturing the depth of an individual student’s poverty with the accuracy required to create and maintain academic and social programs designed and funded to meet the needs of students living in households in deep poverty. A more robust, reliable, and valid measure of students experiencing deep poverty is needed.

For several years, researchers at the Bendheim-Thomas Center for Research on Child Wellbeing at Princeton University have felt the pressing need to “move beyond income-based measures of poverty, ” according to Center Co-Director Kathryn Edin. She and her colleagues are currently utilizing measures of hardship that are more likely to reveal depth of poverty beyond income measures alone.

While there are a number of measures that identify deep poverty, perhaps the most direct, reliable, and valid measure available is a survey of a household’s ability to take care of the basic necessities of life. Households in deep poverty regularly experience food and housing insecurity, often can’t pay their bills, and are unable to access health care when they need it. At a time when access to the internet is essential for a student’s ability to learn online, families living in deep poverty often have their electricity shut off for lack of payment.

One of the most valid and reliable of these “material hardship” types of surveys has been used by the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and, later, the Fragile Families Challenge . Material hardship measures ask direct questions about forgone consumption—that is, what families have had to do without when they may have to live on as little as two dollars a day .

Generally, surveys of material hardship consist of 10 or more questions. Below are some of the types of questions that might be included in a school-based survey to better understand the day-to-day realities for students and families:

- In the past 12 months, were you ever hungry, but didn’t eat because you couldn’t afford enough food?

- In the past 12 months, did you move in with other people even for a little while because of financial problems?

- In the past 12 months, was there anyone in your household who needed to see a doctor or go to the hospital but couldn’t go because of the cost?

- In the past 12 months, did you receive free food or meals?

- In the past 12 months, did you not pay the full amount of a gas, oil, or electricity bill?

These measures do not replace income measures; they supplement them in order to get a fuller understanding of the lived experience of families living in deep poverty. For example, as a supplementary measure, a survey of material hardship could be incorporated into the free and reduced-price lunch forms sent to families to determine their eligibility to receive meals at school. When the material hardship surveys are returned, school administrators would have a clear indication of which students are living in deep poverty.

This recommendation can be seen as a first step in a more comprehensive approach to measuring deep poverty of students. Undocumented or mixed-status families might hesitate to complete government forms for fear of deportation; some families might not complete the material hardship survey due to privacy or other concerns. Some of these concerns could be addressed in community school settings, where the ties between families and the school are often close and continuous. The establishment of trust is a bond that can help to overcome the fear of government.

More From the Blog Series

- In the Fallout of the Pandemic, Community Schools Show a Way Forward for Education

- School-Based Health Centers: Trusted Lifelines in a Time of Crisis

- County-Level Coordination Provides Infrastructure, Funding for Community Schools Initiative

To some busy school administrators, adding any survey might seem burdensome, but the returns on a short material hardship survey are very high. With this information, schools and school systems will be able to tailor programs to meet the needs of children and young adults living in families in deep poverty. These programs should support students’ health and well-being, as well as include academic enhancement and enrichment. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, waiting for the perfect measure could result in increased hardship for students trapped in deep poverty.

Toward Educational Equity

Since the 1990s, the social safety net has been basically shredded. As a result, in many communities, the local public school system is often the only entity situated to meet the needs of students from families in deep poverty by providing meals as well as a safe place to be during the day. Early intervention programs, such a free and high-quality early childhood programs , are a very promising approach to mitigating the effects of deep poverty on young children. Community schools , which provide students and families with a range of supports and services to mitigate the impact of deep poverty—from health and mental health care to before- and after-school care and social service supports—are another promising example. Ensuring that these services are available to children in deep poverty can literally mean the difference between life and death—and between a chance in life and none—for many of these young people.

These are just two examples of how information about students’ level of poverty can lead to improved and expanded services and supports to meet their needs. Of course, schools alone cannot reverse the impact of deep poverty on children, families, and communities. But without well-financed schools with the targeted resources needed to enable students’ learning, the negative effects of deep poverty on children will remain, now and in the future.

Sign up for our mailing list

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

‘Could I really cut it?’

For this ring, I thee sue

Speech is never totally free

Robert Sampson, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, is one of the researchers studying the link between poverty and social mobility.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Unpacking the power of poverty

Peter Reuell

Harvard Staff Writer

Study picks out key indicators like lead exposure, violence, and incarceration that impact children’s later success

Social scientists have long understood that a child’s environment — in particular growing up in poverty — can have long-lasting effects on their success later in life. What’s less well understood is exactly how.

A new Harvard study is beginning to pry open that black box.

Conducted by Robert Sampson, the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences, and Robert Manduca, a doctoral student in sociology and social policy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the study points to a handful of key indicators, including exposure to high levels of lead, violence, and incarceration as key predictors of children’s later success. The study is described in an April paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“What this paper is trying to do, in a sense, is move beyond the traditional neighborhood indicators people use, like poverty,” Sampson said. “For decades, people have shown poverty to be important … but it doesn’t necessarily tell us what the mechanisms are, and how growing up in poor neighborhoods affects children’s outcomes.”

To explore potential pathways, Manduca and Sampson turned to the income tax records of parents and approximately 230,000 children who lived in Chicago in the 1980s and 1990s, compiled by Harvard’s Opportunity Atlas project. They integrated these records with survey data collected by the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, measures of violence and incarceration, census indicators, and blood-lead levels for the city’s neighborhoods in the 1990s.

They found that the greater the extent to which poor black male children were exposed to harsh environments, the higher their chances of being incarcerated in adulthood and the lower their adult incomes, measured in their 30s. A similar income pattern also emerged for whites.

Among both black and white girls, the data showed that increased exposure to harsh environments predicted higher rates of teen pregnancy.

Despite the similarity of results along racial lines, Chicago’s segregation means that far more black children were exposed to harsh environments — in terms of toxicity, violence, and incarceration — harmful to their mental and physical health.

“The least-exposed majority-black neighborhoods still had levels of harshness and toxicity greater than the most-exposed majority-white neighborhoods, which plausibly accounts for a substantial portion of the racial disparities in outcomes,” Manduca said.

“It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.” Robert Sampson

“What this paper shows … is the independent predictive power of harsh environments on top of standard variables,” Sampson said. “It’s really about trying to understand some of the earlier findings, the lived experience of growing up in a poor and racially segregated environment, and how that gets into the minds and bodies of children.”

More like this

Cities’ wealth gap is growing, too

Racial and economic disparities intertwined, study finds

The study isn’t solely focused on the mechanisms of how poverty impacts children; it also challenges traditional notions of what remedies might be available.

“This has [various] policy implications,” Sampson said. “Because when you talk about the effects of poverty, that leads to a particular kind of thinking, which has to do with blocked opportunities and the lack of resources in a neighborhood.

“That doesn’t mean resources are unimportant,” he continued, “but what this study suggests is that environmental policy and criminal justice reform can be thought of as social mobility policy. I think that’s provocative, because that’s different than saying it’s just about poverty itself and childhood education and human capital investment, which has traditionally been the conversation.”

The study did suggest that some factors — like community cohesion, social ties, and friendship networks — could act as bulwarks against harsh environments. Many researchers, including Sampson himself, have shown that community cohesion and local organizations can help reduce violence. But Sampson said their ability to do so is limited.

“One of the positive ways to interpret this is that violence is falling in society,” he said. “Research has shown that community organizations are responsible for a good chunk of the drop. But when it comes to what’s affecting the kids themselves, it’s the homicide that happens on the corner, it’s the lead in their environment, it’s the incarceration of their parents that’s having the more proximate, direct influence.”

Going forward, Sampson said he hopes the study will spur similar research in other cities and expand to include other environmental contamination, including so-called brownfield sites.

Ultimately, Sampson said he hopes the study can reveal the myriad ways in which poverty shapes not only the resources that are available for children, but the very world in which they find themselves growing up.

“Poverty is sort of a catchall term,” he said. “The idea here is to peel things back and ask, What does it mean to grow up in a poor white neighborhood? What does it mean to grow up in a poor black neighborhood? What do kids actually experience?

“What it means for a black child on the south side of Chicago is much higher rates of exposure to violence and lead and incarceration, and this has intergenerational consequences,” he continued. “This is particularly important because it provides a way to think about potentially intervening in the intergenerational reproduction of inequality. We don’t typically think about criminal justice reform or environmental policy as social mobility policy. But maybe we should.”

This research was supported with funding from the Project on Race, Class & Cumulative Adversity at Harvard University, the Ford Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation.

Share this article

You might like.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson discusses new memoir, ‘unlikely path’ from South Florida to Harvard to nation’s highest court

Unhappy suitor wants $70,000 engagement gift back. Now court must decide whether 1950s legal standard has outlived relevance.

Cass Sunstein suggests universities look to First Amendment as they struggle to craft rules in wake of disruptive protests

Harvard releases race data for Class of 2028

Cohort is first to be impacted by Supreme Court’s admissions ruling

Parkinson’s may take a ‘gut-first’ path

Damage to upper GI lining linked to future risk of Parkinson’s disease, says new study

High doses of Adderall may increase psychosis risk

Among those who take prescription amphetamines, 81% of cases of psychosis or mania could have been eliminated if they were not on the high dose, findings suggest

- Get involved

The transformative power of education in the fight against poverty

October 16, 2023.

Zubair Junjunia, a Generation17 young leader and the Founder of ZNotes, presents at EdTechX.

Zubair Junjunia

Generation17 Young Leader and founder of ZNotes

Time and again, research has proven the incredible power of education to break poverty cycles and economically empower individuals from the most marginalized communities with dignified work and upward social mobility.

Research at UNESCO has shown that world poverty would be more than halved if all adults completed secondary school. And if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills, almost 171 million people could escape extreme poverty.

With such irrefutable evidence, how do we continue to see education underfunded globally? Funding for education as a share of national income has not changed significantly over the last decade for any developing country. And to exacerbate that, the COVID-19 shock pushed the level of learning poverty to an estimated 70 percent .

I have devoted the past decade of my life to fighting educational inequality, a journey that began during my school years. This commitment led to the creation of ZNotes , an educational platform developed for students, by students. ZNotes was born out of the problem I witnessed first-hand; the inequities in end-of-school examination, which significantly influence access to higher education and career opportunities. It is designed as a platform where students can share their notes and access top-quality educational materials without any limitations. ZNotes fosters collaborative learning through student-created content within a global community and levels the academic playing field with a student-empowered and technology-enabled approach to content creation and peer learning.

Although I started ZNotes as a solo project, today, it has touched the lives of over 4.5 million students worldwide, receiving an impressive 32 million hits from students across more than 190 countries, especially serving students from emerging economies. We’re proud to say that today, more than 90 percent of students find ZNotes resources useful and feel more confident entering exams , regardless of their socio-economic background. These globally recognized qualifications empower our learners to access tertiary education and enter the world of work.

Sixteen-year-old Zubair set up a blog to share the resources he created for his IGCSE exams. Through word of mouth, his revision notes were discovered by students all over the world and ZNotes was born.

In rapidly changing job market, young people must cultivate resilience and adaptability. World Economic Forum highlights the importance of future skills, encompassing technical, cognitive, and interpersonal abilities. Unfortunately, many educational systems, especially in under-resourced regions, fall short in equipping youth with these vital skills.

To address this challenge, I see innovative technology as a crucial tool both within and beyond traditional school systems. As the digital divide narrows and access to devices and internet connectivity becomes more affordable, delivering quality education and personalized support is increasingly achievable through technology. At ZNotes, we are reshaping the role of students, transforming them from passive consumers to active creators and proponents of education. Empowering youth through a community-driven approach, students engage in peer learning and generate quality resources on an online platform.

Participation in a global learning community enhances young people's communication and collaboration skills. ZNotes fosters a sense of global citizenship, enabling learners to communicate with a diverse range of individuals across race, gender, and religion. Such spaces also result in redistributing social capital as students share advice for future university, internship and career pathways.

“Studying for 14 IGCSE subjects wasn't easy, but ZNotes helped me provide excellent and relevant revision material for all of them. I ended up with 7 A* 7 A, and ZNotes played a huge role. I am off to Cornell University this fall now. A big thank you to the ZNotes team!"

Alongside ensuring our beneficiaries are equipped with the resources and support they need to be at a level playing field for such high stakes exams, we also consider the skills that will set them up for success in life beyond academics. Especially for the hundreds of young people who join our internship and contribution programs , they become part of a global social impact startup and develop both academic skills and also employability skills. After engaging with our internship programs, 77% of interns reported improved candidacy for new jobs and internships.

ZNotes addresses the uneven playing field of standardized testing with a student-empowered and technology-enabled approach for content creation and peer learning.

A few years ago, Jess joined our team as a Social Impact Analyst intern having just completed her university degree while she continued to search for a full-time role. She was able to apply her data analytics skills from a theoretical degree into a real-world scenario and was empowered to play an instrumental role in understanding and developing a Theory of Change model for ZNotes. In just 6 months, she had been able to develop the skills and gain experiences that strengthened her profile. At the end of internship, she was offered a full-time role at a major news and media agency that she is continuing to grow in!

Jess’s example applies to almost every one of our interns . As another one of them, Alexa, said “ZNotes offers the rare and wonderful opportunity to be at the center of meaningful change”.

Being part of an organization making a significant impact is profoundly inspiring and empowering for young people, and assuming high-responsibility roles within such organizations accelerates their skills development and sets them apart in the eyes of prospective employers.

On the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, it is a critical moment to reflect and enact on the opportunity that we have to achieving two key SDGs, Goal 1 and 4, by effectively funding and enabling access to quality education globally.

Global Education Monitoring Report

Reducing global poverty through universal primary and secondary education

The eradication of poverty and the provision of equitable and inclusive quality education for all are two intricately linked Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As this year’s High Level Political Forum focuses on prosperity and poverty reduction, this paper, jointly released by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report, shows why education is so central to the achievement of the SDGs and presents the latest estimates on out-ofschool children, adolescents and youth to demonstrate how much is at stake. At the time of writing, the out-of school rate had not budged since 2008 at the primary level, since 2012 at the lower secondary level and since 2013 at the upper secondary level.

The consequences are grave: if all adults completed secondary school, the global poverty rate would be more than halved.

Related content

Monitoring SDG: Access to education

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Paediatr Child Health

- v.12(8); 2007 Oct

Language: English | French

The impact of poverty on educational outcomes for children

Hb ferguson.

1 Community Health Systems Resource Group, The Hospital for Sick Children

2 Department of Psychiatry, Psychology & Public Health Sciences, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Over the past decade, the unfortunate reality is that the income gap has widened between Canadian families. Educational outcomes are one of the key areas influenced by family incomes. Children from low-income families often start school already behind their peers who come from more affluent families, as shown in measures of school readiness. The incidence, depth, duration and timing of poverty all influence a child’s educational attainment, along with community characteristics and social networks. However, both Canadian and international interventions have shown that the effects of poverty can be reduced using sustainable interventions. Paediatricians and family doctors have many opportunities to influence readiness for school and educational success in primary care settings.

Depuis dix ans, l’écart des revenus s’est creusé entre les familles canadiennes, ce qui est une triste réalité. L’éducation est l’un des principaux domaines sur lesquels influe le revenu familial. Souvent, lorsqu’ils commencent l’école, les enfants de familles à faible revenu accusent déjà un retard par rapport à leurs camarades qui proviennent de familles plus aisées, tel que le démontrent les mesures de maturité scolaire. L’incidence, l’importance, la durée et le moment de la pauvreté ont tous une influence sur le rendement scolaire de l’enfant, de même que les caractéristiques de la communauté et les réseaux sociaux. Cependant, tant au Canada que sur la scène internationale, il est possible de réduire les effets de la pauvreté au moyen d’interventions soutenues. Les pédiatres et les médecins de familles ont de nombreuses occasions d’agir sur la maturité et la réussite scolaire dans le cadre des soins de premier recours.

Poverty remains a stubborn fact of life even in rich countries like Canada. In particular, the poverty of our children has been a continuing concern. In 1989, the Canadian House of Commons voted unanimously to eliminate poverty among Canadian children by 2000 ( 1 ). However, the reality is that, in 2003, one of every six children still lived in poverty. Not only have we been unsuccessful at eradicating child poverty, but over the past decade, the inequity of family incomes in Canada has grown ( 2 ), and for some families, the depth of poverty has increased as well ( 3 ). Canadian research confirms poverty’s negative influence on student behaviour, achievement and retention in school ( 4 ).

Persistent socioeconomic disadvantage has a negative impact on the life outcomes of many Canadian children. Research from the Ontario Child Health Study in the mid-1980s reported noteworthy associations between low income and psychiatric disorders ( 5 ), social and academic functioning ( 6 ), and chronic physical health problems ( 7 ). Since that time, Canada has developed systematic measures that have enabled us to track the impact of a variety of child, family and community factors on children’s well-being. The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) developed by Statistics Canada, Human Resources Development Canada and a number of researchers across the country was started in 1994 with the intention of following representative samples of children to adulthood ( 8 ). Much of our current knowledge about the development of Canadian children is derived from the analysis of the NLSCY data by researchers in a variety of settings.

One of the key areas influenced by family income is educational outcomes. The present article provides a brief review of the literature concerning the effects of poverty on educational outcomes focusing on Canadian research. Canadian data are placed in the perspective of research from other ‘rich’ countries. We conclude with some suggestions about what we can do, as advocates and practitioners, to work toward reducing the negative impact of economic disadvantage on the educational outcomes of our children.

POVERTY AND READINESS FOR SCHOOL

School readiness reflects a child’s ability to succeed both academically and socially in a school environment. It requires physical well-being and appropriate motor development, emotional health and a positive approach to new experiences, age-appropriate social knowledge and competence, age-appropriate language skills, and age-appropriate general knowledge and cognitive skills ( 9 ). It is well documented that poverty decreases a child’s readiness for school through aspects of health, home life, schooling and neighbourhoods. Six poverty-related factors are known to impact child development in general and school readiness in particular. They are the incidence of poverty, the depth of poverty, the duration of poverty, the timing of poverty (eg, age of child), community characteristics (eg, concentration of poverty and crime in neighborhood, and school characteristics) and the impact poverty has on the child’s social network (parents, relatives and neighbors). A child’s home has a particularly strong impact on school readiness. Children from low-income families often do not receive the stimulation and do not learn the social skills required to prepare them for school. Typical problems are parental inconsistency (with regard to daily routines and parenting), frequent changes of primary caregivers, lack of supervision and poor role modelling. Very often, the parents of these children also lack support.

Canadian studies have also demonstrated the association between low-income households and decreased school readiness. A report by Thomas ( 10 ) concluded that children from lower income households score significantly lower on measures of vocabulary and communication skills, knowledge of numbers, copying and symbol use, ability to concentrate and cooperative play with other children than children from higher income households. Janus et al ( 11 ) found that schools with the largest proportion of children with low school readiness were from neighbourhoods of high social risk, including poverty. Willms ( 12 ) established that children from lower socioeconomic status (SES) households scored lower on a receptive vocabulary test than higher SES children. Thus, the evidence is clear and unanimous that poor children arrive at school at a cognitive and behavioural disadvantage. Schools are obviously not in a position to equalize this gap. For instance, research by The Institute of Research and Public Policy (Montreal, Quebec) showed that differences between students from low and high socioeconomic neighbourhoods were evident by grade 3; children from low socioeconomic neighbourhoods were less likely to pass a grade 3 standards test ( 13 ).

POVERTY AND EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Studies emanating from successive waves of the NLSCY have repeatedly shown that socioeconomic factors have a large, pervasive and persistent influence over school achievement ( 14 – 16 ). Phipps and Lethbridge ( 15 ) examined income and child outcomes in children four to 15 years of age based on data from the NLSCY. In this study, higher incomes were consistently associated with better outcomes for children. The largest effects were for cognitive and school measures (teacher-administered math and reading scores), followed by behavioural and health measures, and then social and emotional measures, which had the smallest associations.

These Canadian findings are accompanied by a large number of studies in the United States that have shown that socioeconomic disadvantage and other risk factors that are associated with poverty (eg, lower parental education and high family stress) have a negative effect on cognitive development and academic achievement, smaller effects on behaviour and inconsistent effects on socioemotional outcomes ( 17 – 19 ). Living in extreme and persistent poverty has particularly negative effects ( 18 ), although the consequences of not being defined below the poverty line but still suffering from material hardship should not be underestimated ( 20 ). Furthermore, American studies found strong interaction effects between SES and exposure to risk factors. For instance, parents from disadvantaged backgrounds were not only more likely to have their babies born prematurely, but these prematurely born children were also disproportionately at higher risk for school failure than children with a similar neonatal record from higher income families ( 18 ).

It is worth noting that international studies have consistently shown similar associations between socioeconomic measures and academic outcomes. For example, the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) assessed the comprehensive literacy skills of grade 4 students in 35 countries. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessed reading, math and science scores of 15-year-old children in 43 countries ( 21 ). At these two different stages of schooling, there was a significant relationship between SES and educational measure in all countries. This relationship has come to be known as a ‘socioeconomic gradient’; flatter gradients represent greater ‘equity of outcome’, and are generally associated with better average outcomes and a higher quality of life. Generally, the PISA and the NLSCY data support the conclusion that income or SES has important effects on educational attainment in elementary school through high school. Despite the results shown by the PISA and the NLSCY, schools are not the ultimate equalizer and the socioeconomic gradient still exists despite educational attainment. Test results can be misleading and can mask the gradient if the sample does not account for all children who should be completing the test. A study ( 13 ) completed by the Institute of Research and Public Policy demonstrated only small differences between low and high socioeconomic students when test results were compared in those students who sat for the examination. However, when results were compared for the entire body of children who should have written the examination, the differences between low and high socioeconomic students were staggering, mainly due to the over-representation of those who left school early in the low socioeconomic group.

Longitudinal studies carried out in the United States have been crucial in demonstrating some of the key factors in producing and maintaining poor achievement. Their findings have gone well beyond a model that blames schools or a student’s background for academic failure. Comparisons of the academic growth curves of students during the school year and over the summer showed that much of the achievement gap between low and high SES students could be related to their out-of-school environment (families and communities). This result strongly supports the notion that schools play a crucial compensatory role; however, it also shows the importance of continued support for disadvantaged students outside of the school environment among their families and within their communities ( 22 ).

A Human Resource Development Canada study ( 23 ) titled “The Cost of Dropping Out of High School” reported that lower income students were more likely to leave school without graduating, which agrees with international data. In a nonrandom sample for a qualitative study, Ferguson et al ( 24 ) reported that one-half of Ontario students leaving high school before graduating were raised in homes with annual incomes lower than $30,000. Finally, in Canada, only 31% of youth from the bottom income quartile attended postsecondary education compared with 50.2% in the top income quartile ( 25 ). Once again, the evidence indicates that students from low-income families are disadvantaged right through the education system to postsecondary training.

REVERSING THE EFFECTS OF POVERTY

The negative effects of poverty on all levels of school success have been widely demonstrated and accepted; the critical question for us as a caring society is, can these effects be prevented or reversed? A variety of data are relevant to this question, and recent research gives us reason to be both positive and proactive.

Early intervention

There is a direct link between early childhood intervention and increased social and cognitive ability ( 26 ). Decreasing the risk factors in a child’s environment increases a child’s potential for development and educational attainment. Prevention and intervention programs that target health concerns (eg, immunization and prenatal care) are associated with better health outcomes for low-income children and result in increased cognitive ability ( 27 ). However, it is the parent-child relationship that has been proven to have the greatest influence on reversing the impact of poverty. Both parenting style ( 28 ) and parental involvement, inside and outside of the school environment ( 29 ), impact on a child’s early development. Characteristics of parenting such as predictability of behaviour, social responsiveness, verbal behaviour, mutual attention and positive role modelling have been shown to have a positive effect on several aspects of child outcome. Parental involvement, such as frequency of outings ( 29 ) and problem-based play, creates greater intellectual stimulation and educational support for a child, and develops into increased school readiness ( 26 ).

Interventions act to advance a child’s development through a range of supports and services. Their underlying goal is to develop the skills lacking in children, that have already developed in other children who are of a similar age. There is general agreement that interventions should be data driven, and that assessments and interventions should be closely linked. A primary evaluation of a child and family support systems is, therefore, pivotal in the creation of individualized interventions to ensure success in placing children on a normative trajectory ( 30 ). Ramey and Ramey ( 30 ) determined that interventions have sustained success for children when they increase intellectual skills, create motivational changes, create greater environmental opportunities and/or increase continued access to supports.

Karoly et al ( 31 ) reported the magnitude of effects that early intervention programs have on children. Measured at school entry, they found a pooled mean effect size of around 0.3, with many programs having effect sizes between 0.5 and 0.97. This means that for many interventions, children in the program were, on average, one-half to a full standard deviation above their peers who were not in the program. Interestingly, they found that interventions that combined parent education programs with child programs had significantly higher effect sizes. Furthermore, interventions that continued beyond the early years showed significantly lower fade-out effects. The results strongly support the notion that early interventions should include the whole family and be continued beyond the early years. Constant evaluation of interventions should be completed to ensure that the benefits for children are maximized using these key components.

Highly regarded early interventions

The High/Scope active learning approach is a comprehensive early childhood curriculum. It uses cooperative work and communication skills to have children ‘learn by doing’. Individual, and small and large group formats are used for teacher-and-child planned activities in the key subject areas of language and literacy, mathematics, science, music and rhythmic movement. There has been ongoing evaluation of the approach since 1962 using 123 low-income African-American children at high risk of school failure ( 32 ). Fifty-eight children received high-quality early care and an educational setting, as well as home visits from the teachers to discuss their developmental progress. By 40 years of age, children who received the intervention were more likely to have graduated high school, hold a job, have higher earnings and have committed fewer crimes.

Similar positive effects of preschool intervention were found in the evaluation of the Abecedarian project ( 33 ). This project enlisted children between infancy and five years of age from low-income families to receive a high-quality educational intervention that was individualized to their needs. The intervention used games focused on social, emotional and cognitive areas of development. Children were evaluated at 12, 15 and 21 years of age, and those who had received the intervention had higher cognitive test scores, had greater academic achievement in reading and math, had completed more years of education and were more likely to have attended a four-year college. Interestingly, the mothers of children participating in the program also had higher educational and employment status after the intervention.

One of the oldest and most eminent early intervention programs is the Chicago Child Parent Center program. The intervention targets students who are between preschool and grade 3 through language-based activities, outreach activities, ongoing staff development and health services. Importantly, there is no set curriculum; the program is tailored to the needs of each child ( 34 ). One crucial feature of the program is the extensive involvement of parents. Multifaceted parental programs are offered to improve parental knowledge, their engagement in their children’s education and their parental skills. An evaluation of the Chicago Child Parent Center Program was completed by Reynolds ( 34 ) using a sample of 1106 black children from low-income families. They were exposed to the intervention in preschool, kindergarten and follow-up components. Two years after the completion of the intervention, the results indicated that the duration of intervention was associated with greater academic achievement in reading and mathematics, teacher ratings of school adjustment, parental involvement in school activities, grade retention and special education placement ( 34 ). Evaluation of the long-term effects of the intervention was completed by Reynolds ( 35 ) after 15 years of follow-up. Individuals who had participated in the early childhood intervention for at least one or two years had higher rates of school completion, had attained more years of education, and had lower rates of juvenile arrests, violent arrests leaving school early.

Later intervention

A common question concerns the stage at which it is too late for interventions to be successful. Recent findings (N Rowen, personal communication) from an uncontrolled community study in Toronto, Ontario, have suggested that a multisys-temic intervention as students transition to high school can produce dramatic results. The Pathways to Education project began because of a community (parents) request to a local health agency to help their children succeed in high school. The community consisted mainly of people from a public housing complex, with the majority of families being poor, immigrants and from visible minority groups. The Pathways project grew out of a partnership between the community, the health centre and the school board, and was funded by a variety of sources. The core elements of the program include a contract between the student, parents and project; student-parent support workers who advocate for the student at school and connect parents to the project and/or school; four nights a week of tutoring (by volunteers) in the community; group and career mentoring located in the community; and financial support, such as money for public transit and scholarship money for postsecondary education dependent on successful academic work and graduation. The Pathways project has been running for six years, and the results for the first five cohorts of students have been exciting. In comparison to a preproject cohort, the absentee and academic ‘at-risk’ rate (credit accumulation) has fallen by 50% to 60%, the ‘dropout’ rate has fallen by 80% to a level below the average for the board of education and the five-year graduation rate has risen from 42% to 75%. Of the graduates, 80% go on to college or university, compared with 42% before the Pathways project. While these initial results must be replicated in other communities, they suggest that, even at the high school level, interventions can be startlingly effective, even in a community with a long history of poverty, recent immigration and racism. As the proponents of Pathways move to replication, they will need to be careful to untangle the effects of community commitment, school board collaboration and the rich set of collaborations that have been a hallmark of this first demonstration project. Nevertheless, Pathways has made it clear that Canadian communities possess the capacity to change the education outcomes of their children and youth. While it takes resolve and resources to achieve such effects, initial analysis suggests that over the lifetime of the students, each dollar invested will be returned to Canada more than 24 times ( 36 )!

Schools make a difference

Canadian and international research on educational outcomes has revealed important data on the effects of schools and classrooms. Frempong and Willms ( 37 ) used complex analyses of student performance in mathematics to demonstrate that Canadian schools, and even classrooms, do make a difference in student outcomes (ie, students from similar home backgrounds achieve significantly different levels of performance in different schools). Furthermore, schools and classrooms differ in their SES gradients (ie, some schools achieve not just higher scores, but more equitable outcomes than others). These general findings were corroborated by Willms ( 38 ) using reading scores from children in grade 4 and those 15 years of age from 34 countries. Once again, it was demonstrated that schools make a difference and that some schools are more equitable than others. According to Thomas ( 10 ), activities other than academics, such as sports and lessons in the arts, have been shown to increase student’s school readiness despite SES. These activities should be encouraged in all schools to maximize school readiness. A key to making schools more effective at raising the performance of low SES students is to keep schools heterogeneous with regard to the SES of their students (ie, all types of streaming result in markedly poor outcomes for disadvantaged children and youth).

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Balancing the consistent evidence about the pervasive negative impact of poverty on educational outcomes with the hopeful positive outcomes of intervention studies, what can we do in our communities to attenuate the effects of poverty and SES on academic success? Here are some important actions:

- Advocate for and support schools which strive to achieve equity of outcomes;

- Advocate for and support intervention programs that provide academic, social and community support to raise the success of disadvantaged children and youth;

- Make others aware of the short-, medium- and long-term costs of allowing these children and youth to fail or leave school;

- Never miss a personal opportunity to support the potential educational success of the children and youth who we come into contact with;

- Advocate for system changes within schools to maximize educational attainment (eg, longer school days and shorter summer vacations); and

- Advocate for quality early education and care to minimize differences between children’s school readiness before entering school.

Paediatricians and family doctors have many opportunities to influence readiness for school and educational success in primary care settings. Golova et al ( 39 ) reported intriguing results from a primary care setting. They delivered a literacy promoting intervention to low-income Hispanic families in health care settings. At the initial visit (average age 7.4 months), parents received a bilingual handout explaining the benefits of reading aloud to children, literacy-related guidance from paediatric providers or an age-appropriate bilingual children’s board book. Control group families received no handouts or books. At a 10-month follow-up visit (mean age 17.7 months), there was no difference between groups on a screening test for language scores; however, intervention families read more often to their children, reported greater enjoyment of reading to children and had more children’s books in their homes. Given this suggestive finding, there are a number of points that paediatricians and family doctors should consider as they deliver primary care:

- Observe and encourage good parenting – mutual attention and contingency of interaction (taking turns and listening to each other), verbal behaviour (amount of talking and quality), sensitivity and responsiveness (awareness to signs of hunger, fatigue, boredom and providing an appropriate response), role modelling and reading to their children;

- Encourage parents to increase their knowledge of child development, particularly age-appropriate needs of and activities for their children. Explain to them, for instance, how ear infections can severely affect a student’s language development, and that good nutrition and hygiene can lower the frequency and severity of infections;

- Encourage parents who do not have their children in institutionalized care to attend parent-child centres and programs. These programs usually do not charge fees and require no formal arrangements. Examples are the Ontario Early Years Centres, the Aboriginal Head Start Program in Northern communities, and programs related to the Alberta Children and Youth Initiative;

- Indicate the importance of parental support and networks – keep a message board in your office and post a list of community-based organizations in your neighborhood; and

- Keep in mind that poverty is not always obvious. One in five low-income families is headed by a parent who works full-time all year; thus, it is often difficult to tell if a family is in need ( 40 ).

Poverty's impact on educational opportunity

Fifty years ago, communities across America began efforts to make school districts more racially integrated, believing it would ease racial disparities in students’ educational opportunities. But new evidence shows that while racial segregation within a district is a very strong predictor of achievement gaps, school poverty – not the racial composition of schools – accounts for this effect.

In other words, racial segregation remains a major source of educational inequality, but this is because racial segregation almost always concentrates black and Hispanic students in high-poverty schools, according to new research led by Sean Reardon, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR).

“The only school districts in the U.S. where racial achievement gaps are even moderately small are those where there is little or no segregation. Every moderately or highly segregated district has large racial achievement gaps,” said Reardon, the Professor of Poverty and Inequality at the GSE. “But it’s not the racial composition of the schools that matters. What matters is when black or Hispanic students are concentrated in high-poverty schools in a district.”

The findings were released on Sept. 23 in a paper accompanying the launch of a new interactive data tool from the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, an initiative directed by Reardon to support efforts to reduce educational disparities throughout the United States.

Test scores as measures of opportunity

The Educational Opportunity Project gives journalists, educators, policymakers and parents a way to explore and compare data from the groundbreaking Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA), the first comprehensive national database of academic performance.

The database, first made available online in 2016 in a format designed mainly for researchers, is built from 350 million reading and math test scores from third to eighth grade students during 2008-2016 in every public school in the nation. It also includes district-level measures of racial and socioeconomic composition, segregation patterns and other educational conditions.

Researchers have used the massive data set over the past few years to study variations in educational opportunity by race, gender and socioeconomic conditions throughout the United States. The data have also shown that students’ early test scores do not predict academic growth over time, indicating that poverty does not determine the effectiveness of a school.

Now, with an interactive tool on the Educational Opportunity Project’s website, any user can generate charts, maps and downloadable PDFs to illustrate and compare data from individual schools, districts or counties. (Visualizations also can be embedded elsewhere online so that users can access them directly from another site.)

The site provides detailed data on three measures of educational opportunity:

- Average test scores, which reflect all of the educational opportunities children have from birth through middle school

- Learning rates (how much students learn from one year to the next), which reflect the opportunities available in their schools

- Trends in how much average test scores change each year, which reflect changes in the opportunities available to successive cohorts of children

“We can also break it down and look at how students are performing differentially by race, by ethnicity, by gender, by family income,” said Reardon. “That lets us understand not just how a community is providing opportunity for everyone, but whether it’s providing the same amount of opportunity for children from different backgrounds.”

Beyond learning about their own school or districts, users can also find and learn from comparable communities with fewer inequities. For instance, superintendents concerned about the achievement gap between students of different race and ethnicity in their district could use the tool to identify other districts around the country that are similar in size and demographics but have smaller achievement gaps – and then reach out to leaders in those communities to find out about the practices and policies that have been effective.

A better gauge of school quality

The information on learning rates is a key innovation of the site, Reardon said, because these trends provide a picture of educational opportunity that’s vastly different from what average test scores show.

By indicating how much students learn as they go through school, these rates are “a much better measure of school quality,” said Reardon. “If parents were to use the learning rate data to help inform their decisions about where to live, they might make very different choices in many cases.”

What’s more, data on learning rates are largely unavailable elsewhere. “Some states and websites provide some measure of learning rates for a community, but their data are typically based on one year of growth, and they aren’t comparable across states,” he said. “Our learning rates are based on eight years of data, so they’re much more reliable.”

Reardon acknowledged the limitations of measuring student achievement through reading and math scores. “Test scores certainly don’t measure everything we want for our kids,” he said. “We also want them to learn art and music, to learn to be empathetic and kind, creative and collaborative, and to have good friends and be happy – it’s not all about math and reading.”

He also cautioned that differences in average test scores do not reflect differences in students’ intelligence or abilities. “When we look at average test scores in a community, a school district or a school, what we’re measuring is really the amount of educational opportunity provided in those communities – not the average ability,” he said. “Average ability doesn’t vary from one place to another, but opportunity does.”

Identifying the effects of school segregation

In studying segregation in U.S. schools today, Reardon and colleagues sought to discover whether racial segregation has the same harmful effects that it did 50 years ago, when efforts to integrate Southern school districts began in earnest.

The research team used the data now available through the Educational Opportunity Project to investigate first how strongly segregation levels are associated with academic achievement gaps.

What they found was striking: Without exception, the level of segregation correlated not only with the size of the achievement gap, but also with the rate at which that gap grew as students progressed from third to eighth grade.

To determine what accounted for the correlation, they controlled for racial differences in school poverty and found that segregation no longer predicted the achievement gaps. That meant the association between racial segregation and the growth of achievement gaps operated entirely through differences in school poverty.

“While racial segregation is important, it’s not the race of one’s classmates that matters, per se,” said Reardon. “It’s the fact that in America today, racial segregation brings with it very unequal concentrations of students in high- and low-poverty schools.”

Educational epidemiology

With new, accessible evidence for the relationship between test score patterns and socioeconomic status, race and gender, the Educational Opportunity Project lays the groundwork for more targeted policies to address disparities.

Reardon sees the project as a kind of educational epidemiology. “In order to fix problems of inequality and improve schools, we need to have a good understanding of the landscape of the problem,” he said. “In some ways, that’s what epidemiologists do.”

By pinpointing where disparities exist, where they’re getting worse or better and the factors that correlate with local trends, the Educational Opportunity Project aims to bring both researchers and community members closer to understanding how to create more equitable learning opportunities, in and out of school.

Then, said Reardon, “we can get to a place where we can start to have targeted social and educational policy solutions that will really make a difference.”

The Educational Opportunity Project has been supported by grants from the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences, the Spencer Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Overdeck Family Foundation.

Co-authors of the research paper on school segregation are Ericka S. Weathers, PhD ’18, an assistant professor at Penn State College of Education; Erin M. Fahle, PhD ’18, an assistant professor at St. John’s University School of Education; Heewon Jang, a doctoral student at Stanford GSE; and Demetra Kalogrides, a research associate with the Center for Education Policy Analysis (CEPA) at Stanford GSE.

More News Topics

Trump’s tax-cut proposal shakes up social security debate.

- Media Mention

- Politics and Media

- Money and Finance

Can global supply chains be fixed?

- Research Highlight

- Global Development and Trade

- Regulation and Competition

Presidential debate fact check: Analyzing Trump, Harris on abortion, immigration, more