- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

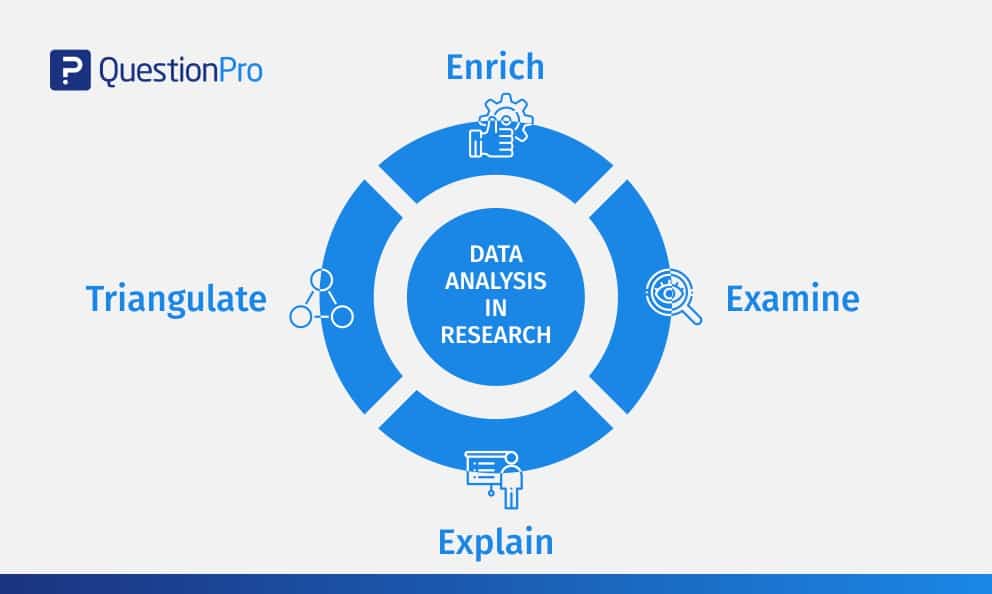

Data Analysis in Research: Types & Methods

Content Index

Why analyze data in research?

Types of data in research, finding patterns in the qualitative data, methods used for data analysis in qualitative research, preparing data for analysis, methods used for data analysis in quantitative research, considerations in research data analysis, what is data analysis in research.

Definition of research in data analysis: According to LeCompte and Schensul, research data analysis is a process used by researchers to reduce data to a story and interpret it to derive insights. The data analysis process helps reduce a large chunk of data into smaller fragments, which makes sense.

Three essential things occur during the data analysis process — the first is data organization . Summarization and categorization together contribute to becoming the second known method used for data reduction. It helps find patterns and themes in the data for easy identification and linking. The third and last way is data analysis – researchers do it in both top-down and bottom-up fashion.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

On the other hand, Marshall and Rossman describe data analysis as a messy, ambiguous, and time-consuming but creative and fascinating process through which a mass of collected data is brought to order, structure and meaning.

We can say that “the data analysis and data interpretation is a process representing the application of deductive and inductive logic to the research and data analysis.”

Researchers rely heavily on data as they have a story to tell or research problems to solve. It starts with a question, and data is nothing but an answer to that question. But, what if there is no question to ask? Well! It is possible to explore data even without a problem – we call it ‘Data Mining’, which often reveals some interesting patterns within the data that are worth exploring.

Irrelevant to the type of data researchers explore, their mission and audiences’ vision guide them to find the patterns to shape the story they want to tell. One of the essential things expected from researchers while analyzing data is to stay open and remain unbiased toward unexpected patterns, expressions, and results. Remember, sometimes, data analysis tells the most unforeseen yet exciting stories that were not expected when initiating data analysis. Therefore, rely on the data you have at hand and enjoy the journey of exploratory research.

Create a Free Account

Every kind of data has a rare quality of describing things after assigning a specific value to it. For analysis, you need to organize these values, processed and presented in a given context, to make it useful. Data can be in different forms; here are the primary data types.

- Qualitative data: When the data presented has words and descriptions, then we call it qualitative data . Although you can observe this data, it is subjective and harder to analyze data in research, especially for comparison. Example: Quality data represents everything describing taste, experience, texture, or an opinion that is considered quality data. This type of data is usually collected through focus groups, personal qualitative interviews , qualitative observation or using open-ended questions in surveys.

- Quantitative data: Any data expressed in numbers of numerical figures are called quantitative data . This type of data can be distinguished into categories, grouped, measured, calculated, or ranked. Example: questions such as age, rank, cost, length, weight, scores, etc. everything comes under this type of data. You can present such data in graphical format, charts, or apply statistical analysis methods to this data. The (Outcomes Measurement Systems) OMS questionnaires in surveys are a significant source of collecting numeric data.

- Categorical data: It is data presented in groups. However, an item included in the categorical data cannot belong to more than one group. Example: A person responding to a survey by telling his living style, marital status, smoking habit, or drinking habit comes under the categorical data. A chi-square test is a standard method used to analyze this data.

Learn More : Examples of Qualitative Data in Education

Data analysis in qualitative research

Data analysis and qualitative data research work a little differently from the numerical data as the quality data is made up of words, descriptions, images, objects, and sometimes symbols. Getting insight from such complicated information is a complicated process. Hence it is typically used for exploratory research and data analysis .

Although there are several ways to find patterns in the textual information, a word-based method is the most relied and widely used global technique for research and data analysis. Notably, the data analysis process in qualitative research is manual. Here the researchers usually read the available data and find repetitive or commonly used words.

For example, while studying data collected from African countries to understand the most pressing issues people face, researchers might find “food” and “hunger” are the most commonly used words and will highlight them for further analysis.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

The keyword context is another widely used word-based technique. In this method, the researcher tries to understand the concept by analyzing the context in which the participants use a particular keyword.

For example , researchers conducting research and data analysis for studying the concept of ‘diabetes’ amongst respondents might analyze the context of when and how the respondent has used or referred to the word ‘diabetes.’

The scrutiny-based technique is also one of the highly recommended text analysis methods used to identify a quality data pattern. Compare and contrast is the widely used method under this technique to differentiate how a specific text is similar or different from each other.

For example: To find out the “importance of resident doctor in a company,” the collected data is divided into people who think it is necessary to hire a resident doctor and those who think it is unnecessary. Compare and contrast is the best method that can be used to analyze the polls having single-answer questions types .

Metaphors can be used to reduce the data pile and find patterns in it so that it becomes easier to connect data with theory.

Variable Partitioning is another technique used to split variables so that researchers can find more coherent descriptions and explanations from the enormous data.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

There are several techniques to analyze the data in qualitative research, but here are some commonly used methods,

- Content Analysis: It is widely accepted and the most frequently employed technique for data analysis in research methodology. It can be used to analyze the documented information from text, images, and sometimes from the physical items. It depends on the research questions to predict when and where to use this method.

- Narrative Analysis: This method is used to analyze content gathered from various sources such as personal interviews, field observation, and surveys . The majority of times, stories, or opinions shared by people are focused on finding answers to the research questions.

- Discourse Analysis: Similar to narrative analysis, discourse analysis is used to analyze the interactions with people. Nevertheless, this particular method considers the social context under which or within which the communication between the researcher and respondent takes place. In addition to that, discourse analysis also focuses on the lifestyle and day-to-day environment while deriving any conclusion.

- Grounded Theory: When you want to explain why a particular phenomenon happened, then using grounded theory for analyzing quality data is the best resort. Grounded theory is applied to study data about the host of similar cases occurring in different settings. When researchers are using this method, they might alter explanations or produce new ones until they arrive at some conclusion.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Data analysis in quantitative research

The first stage in research and data analysis is to make it for the analysis so that the nominal data can be converted into something meaningful. Data preparation consists of the below phases.

Phase I: Data Validation

Data validation is done to understand if the collected data sample is per the pre-set standards, or it is a biased data sample again divided into four different stages

- Fraud: To ensure an actual human being records each response to the survey or the questionnaire

- Screening: To make sure each participant or respondent is selected or chosen in compliance with the research criteria

- Procedure: To ensure ethical standards were maintained while collecting the data sample

- Completeness: To ensure that the respondent has answered all the questions in an online survey. Else, the interviewer had asked all the questions devised in the questionnaire.

Phase II: Data Editing

More often, an extensive research data sample comes loaded with errors. Respondents sometimes fill in some fields incorrectly or sometimes skip them accidentally. Data editing is a process wherein the researchers have to confirm that the provided data is free of such errors. They need to conduct necessary checks and outlier checks to edit the raw edit and make it ready for analysis.

Phase III: Data Coding

Out of all three, this is the most critical phase of data preparation associated with grouping and assigning values to the survey responses . If a survey is completed with a 1000 sample size, the researcher will create an age bracket to distinguish the respondents based on their age. Thus, it becomes easier to analyze small data buckets rather than deal with the massive data pile.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

After the data is prepared for analysis, researchers are open to using different research and data analysis methods to derive meaningful insights. For sure, statistical analysis plans are the most favored to analyze numerical data. In statistical analysis, distinguishing between categorical data and numerical data is essential, as categorical data involves distinct categories or labels, while numerical data consists of measurable quantities. The method is again classified into two groups. First, ‘Descriptive Statistics’ used to describe data. Second, ‘Inferential statistics’ that helps in comparing the data .

Descriptive statistics

This method is used to describe the basic features of versatile types of data in research. It presents the data in such a meaningful way that pattern in the data starts making sense. Nevertheless, the descriptive analysis does not go beyond making conclusions. The conclusions are again based on the hypothesis researchers have formulated so far. Here are a few major types of descriptive analysis methods.

Measures of Frequency

- Count, Percent, Frequency

- It is used to denote home often a particular event occurs.

- Researchers use it when they want to showcase how often a response is given.

Measures of Central Tendency

- Mean, Median, Mode

- The method is widely used to demonstrate distribution by various points.

- Researchers use this method when they want to showcase the most commonly or averagely indicated response.

Measures of Dispersion or Variation

- Range, Variance, Standard deviation

- Here the field equals high/low points.

- Variance standard deviation = difference between the observed score and mean

- It is used to identify the spread of scores by stating intervals.

- Researchers use this method to showcase data spread out. It helps them identify the depth until which the data is spread out that it directly affects the mean.

Measures of Position

- Percentile ranks, Quartile ranks

- It relies on standardized scores helping researchers to identify the relationship between different scores.

- It is often used when researchers want to compare scores with the average count.

For quantitative research use of descriptive analysis often give absolute numbers, but the in-depth analysis is never sufficient to demonstrate the rationale behind those numbers. Nevertheless, it is necessary to think of the best method for research and data analysis suiting your survey questionnaire and what story researchers want to tell. For example, the mean is the best way to demonstrate the students’ average scores in schools. It is better to rely on the descriptive statistics when the researchers intend to keep the research or outcome limited to the provided sample without generalizing it. For example, when you want to compare average voting done in two different cities, differential statistics are enough.

Descriptive analysis is also called a ‘univariate analysis’ since it is commonly used to analyze a single variable.

Inferential statistics

Inferential statistics are used to make predictions about a larger population after research and data analysis of the representing population’s collected sample. For example, you can ask some odd 100 audiences at a movie theater if they like the movie they are watching. Researchers then use inferential statistics on the collected sample to reason that about 80-90% of people like the movie.

Here are two significant areas of inferential statistics.

- Estimating parameters: It takes statistics from the sample research data and demonstrates something about the population parameter.

- Hypothesis test: I t’s about sampling research data to answer the survey research questions. For example, researchers might be interested to understand if the new shade of lipstick recently launched is good or not, or if the multivitamin capsules help children to perform better at games.

These are sophisticated analysis methods used to showcase the relationship between different variables instead of describing a single variable. It is often used when researchers want something beyond absolute numbers to understand the relationship between variables.

Here are some of the commonly used methods for data analysis in research.

- Correlation: When researchers are not conducting experimental research or quasi-experimental research wherein the researchers are interested to understand the relationship between two or more variables, they opt for correlational research methods.

- Cross-tabulation: Also called contingency tables, cross-tabulation is used to analyze the relationship between multiple variables. Suppose provided data has age and gender categories presented in rows and columns. A two-dimensional cross-tabulation helps for seamless data analysis and research by showing the number of males and females in each age category.

- Regression analysis: For understanding the strong relationship between two variables, researchers do not look beyond the primary and commonly used regression analysis method, which is also a type of predictive analysis used. In this method, you have an essential factor called the dependent variable. You also have multiple independent variables in regression analysis. You undertake efforts to find out the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable. The values of both independent and dependent variables are assumed as being ascertained in an error-free random manner.

- Frequency tables: The statistical procedure is used for testing the degree to which two or more vary or differ in an experiment. A considerable degree of variation means research findings were significant. In many contexts, ANOVA testing and variance analysis are similar.

- Analysis of variance: The statistical procedure is used for testing the degree to which two or more vary or differ in an experiment. A considerable degree of variation means research findings were significant. In many contexts, ANOVA testing and variance analysis are similar.

- Researchers must have the necessary research skills to analyze and manipulation the data , Getting trained to demonstrate a high standard of research practice. Ideally, researchers must possess more than a basic understanding of the rationale of selecting one statistical method over the other to obtain better data insights.

- Usually, research and data analytics projects differ by scientific discipline; therefore, getting statistical advice at the beginning of analysis helps design a survey questionnaire, select data collection methods , and choose samples.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

- The primary aim of data research and analysis is to derive ultimate insights that are unbiased. Any mistake in or keeping a biased mind to collect data, selecting an analysis method, or choosing audience sample il to draw a biased inference.

- Irrelevant to the sophistication used in research data and analysis is enough to rectify the poorly defined objective outcome measurements. It does not matter if the design is at fault or intentions are not clear, but lack of clarity might mislead readers, so avoid the practice.

- The motive behind data analysis in research is to present accurate and reliable data. As far as possible, avoid statistical errors, and find a way to deal with everyday challenges like outliers, missing data, data altering, data mining , or developing graphical representation.

LEARN MORE: Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research The sheer amount of data generated daily is frightening. Especially when data analysis has taken center stage. in 2018. In last year, the total data supply amounted to 2.8 trillion gigabytes. Hence, it is clear that the enterprises willing to survive in the hypercompetitive world must possess an excellent capability to analyze complex research data, derive actionable insights, and adapt to the new market needs.

LEARN ABOUT: Average Order Value

QuestionPro is an online survey platform that empowers organizations in data analysis and research and provides them a medium to collect data by creating appealing surveys.

MORE LIKE THIS

Jotform vs SurveyMonkey: Which Is Best in 2024

Aug 15, 2024

360 Degree Feedback Spider Chart is Back!

Aug 14, 2024

Jotform vs Wufoo: Comparison of Features and Prices

Aug 13, 2024

Product or Service: Which is More Important? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Data Analysis

- Introduction to Data Analysis

- Quantitative Analysis Tools

- Qualitative Analysis Tools

- Mixed Methods Analysis

- Geospatial Analysis

- Further Reading

What is Data Analysis?

According to the federal government, data analysis is "the process of systematically applying statistical and/or logical techniques to describe and illustrate, condense and recap, and evaluate data" ( Responsible Conduct in Data Management ). Important components of data analysis include searching for patterns, remaining unbiased in drawing inference from data, practicing responsible data management , and maintaining "honest and accurate analysis" ( Responsible Conduct in Data Management ).

In order to understand data analysis further, it can be helpful to take a step back and understand the question "What is data?". Many of us associate data with spreadsheets of numbers and values, however, data can encompass much more than that. According to the federal government, data is "The recorded factual material commonly accepted in the scientific community as necessary to validate research findings" ( OMB Circular 110 ). This broad definition can include information in many formats.

Some examples of types of data are as follows:

- Photographs

- Hand-written notes from field observation

- Machine learning training data sets

- Ethnographic interview transcripts

- Sheet music

- Scripts for plays and musicals

- Observations from laboratory experiments ( CMU Data 101 )

Thus, data analysis includes the processing and manipulation of these data sources in order to gain additional insight from data, answer a research question, or confirm a research hypothesis.

Data analysis falls within the larger research data lifecycle, as seen below.

( University of Virginia )

Why Analyze Data?

Through data analysis, a researcher can gain additional insight from data and draw conclusions to address the research question or hypothesis. Use of data analysis tools helps researchers understand and interpret data.

What are the Types of Data Analysis?

Data analysis can be quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods.

Quantitative research typically involves numbers and "close-ended questions and responses" ( Creswell & Creswell, 2018 , p. 3). Quantitative research tests variables against objective theories, usually measured and collected on instruments and analyzed using statistical procedures ( Creswell & Creswell, 2018 , p. 4). Quantitative analysis usually uses deductive reasoning.

Qualitative research typically involves words and "open-ended questions and responses" ( Creswell & Creswell, 2018 , p. 3). According to Creswell & Creswell, "qualitative research is an approach for exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem" ( 2018 , p. 4). Thus, qualitative analysis usually invokes inductive reasoning.

Mixed methods research uses methods from both quantitative and qualitative research approaches. Mixed methods research works under the "core assumption... that the integration of qualitative and quantitative data yields additional insight beyond the information provided by either the quantitative or qualitative data alone" ( Creswell & Creswell, 2018 , p. 4).

- Next: Planning >>

- Last Updated: Jun 25, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.georgetown.edu/data-analysis

Quantitative Data Analysis 101

The lingo, methods and techniques, explained simply.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) and Kerryn Warren (PhD) | December 2020

Quantitative data analysis is one of those things that often strikes fear in students. It’s totally understandable – quantitative analysis is a complex topic, full of daunting lingo , like medians, modes, correlation and regression. Suddenly we’re all wishing we’d paid a little more attention in math class…

The good news is that while quantitative data analysis is a mammoth topic, gaining a working understanding of the basics isn’t that hard , even for those of us who avoid numbers and math . In this post, we’ll break quantitative analysis down into simple , bite-sized chunks so you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Quantitative Data Analysis 101

- What (exactly) is quantitative data analysis?

- When to use quantitative analysis

- How quantitative analysis works

The two “branches” of quantitative analysis

- Descriptive statistics 101

- Inferential statistics 101

- How to choose the right quantitative methods

- Recap & summary

What is quantitative data analysis?

Despite being a mouthful, quantitative data analysis simply means analysing data that is numbers-based – or data that can be easily “converted” into numbers without losing any meaning.

For example, category-based variables like gender, ethnicity, or native language could all be “converted” into numbers without losing meaning – for example, English could equal 1, French 2, etc.

This contrasts against qualitative data analysis, where the focus is on words, phrases and expressions that can’t be reduced to numbers. If you’re interested in learning about qualitative analysis, check out our post and video here .

What is quantitative analysis used for?

Quantitative analysis is generally used for three purposes.

- Firstly, it’s used to measure differences between groups . For example, the popularity of different clothing colours or brands.

- Secondly, it’s used to assess relationships between variables . For example, the relationship between weather temperature and voter turnout.

- And third, it’s used to test hypotheses in a scientifically rigorous way. For example, a hypothesis about the impact of a certain vaccine.

Again, this contrasts with qualitative analysis , which can be used to analyse people’s perceptions and feelings about an event or situation. In other words, things that can’t be reduced to numbers.

How does quantitative analysis work?

Well, since quantitative data analysis is all about analysing numbers , it’s no surprise that it involves statistics . Statistical analysis methods form the engine that powers quantitative analysis, and these methods can vary from pretty basic calculations (for example, averages and medians) to more sophisticated analyses (for example, correlations and regressions).

Sounds like gibberish? Don’t worry. We’ll explain all of that in this post. Importantly, you don’t need to be a statistician or math wiz to pull off a good quantitative analysis. We’ll break down all the technical mumbo jumbo in this post.

Need a helping hand?

As I mentioned, quantitative analysis is powered by statistical analysis methods . There are two main “branches” of statistical methods that are used – descriptive statistics and inferential statistics . In your research, you might only use descriptive statistics, or you might use a mix of both , depending on what you’re trying to figure out. In other words, depending on your research questions, aims and objectives . I’ll explain how to choose your methods later.

So, what are descriptive and inferential statistics?

Well, before I can explain that, we need to take a quick detour to explain some lingo. To understand the difference between these two branches of statistics, you need to understand two important words. These words are population and sample .

First up, population . In statistics, the population is the entire group of people (or animals or organisations or whatever) that you’re interested in researching. For example, if you were interested in researching Tesla owners in the US, then the population would be all Tesla owners in the US.

However, it’s extremely unlikely that you’re going to be able to interview or survey every single Tesla owner in the US. Realistically, you’ll likely only get access to a few hundred, or maybe a few thousand owners using an online survey. This smaller group of accessible people whose data you actually collect is called your sample .

So, to recap – the population is the entire group of people you’re interested in, and the sample is the subset of the population that you can actually get access to. In other words, the population is the full chocolate cake , whereas the sample is a slice of that cake.

So, why is this sample-population thing important?

Well, descriptive statistics focus on describing the sample , while inferential statistics aim to make predictions about the population, based on the findings within the sample. In other words, we use one group of statistical methods – descriptive statistics – to investigate the slice of cake, and another group of methods – inferential statistics – to draw conclusions about the entire cake. There I go with the cake analogy again…

With that out the way, let’s take a closer look at each of these branches in more detail.

Branch 1: Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics serve a simple but critically important role in your research – to describe your data set – hence the name. In other words, they help you understand the details of your sample . Unlike inferential statistics (which we’ll get to soon), descriptive statistics don’t aim to make inferences or predictions about the entire population – they’re purely interested in the details of your specific sample .

When you’re writing up your analysis, descriptive statistics are the first set of stats you’ll cover, before moving on to inferential statistics. But, that said, depending on your research objectives and research questions , they may be the only type of statistics you use. We’ll explore that a little later.

So, what kind of statistics are usually covered in this section?

Some common statistical tests used in this branch include the following:

- Mean – this is simply the mathematical average of a range of numbers.

- Median – this is the midpoint in a range of numbers when the numbers are arranged in numerical order. If the data set makes up an odd number, then the median is the number right in the middle of the set. If the data set makes up an even number, then the median is the midpoint between the two middle numbers.

- Mode – this is simply the most commonly occurring number in the data set.

- In cases where most of the numbers are quite close to the average, the standard deviation will be relatively low.

- Conversely, in cases where the numbers are scattered all over the place, the standard deviation will be relatively high.

- Skewness . As the name suggests, skewness indicates how symmetrical a range of numbers is. In other words, do they tend to cluster into a smooth bell curve shape in the middle of the graph, or do they skew to the left or right?

Feeling a bit confused? Let’s look at a practical example using a small data set.

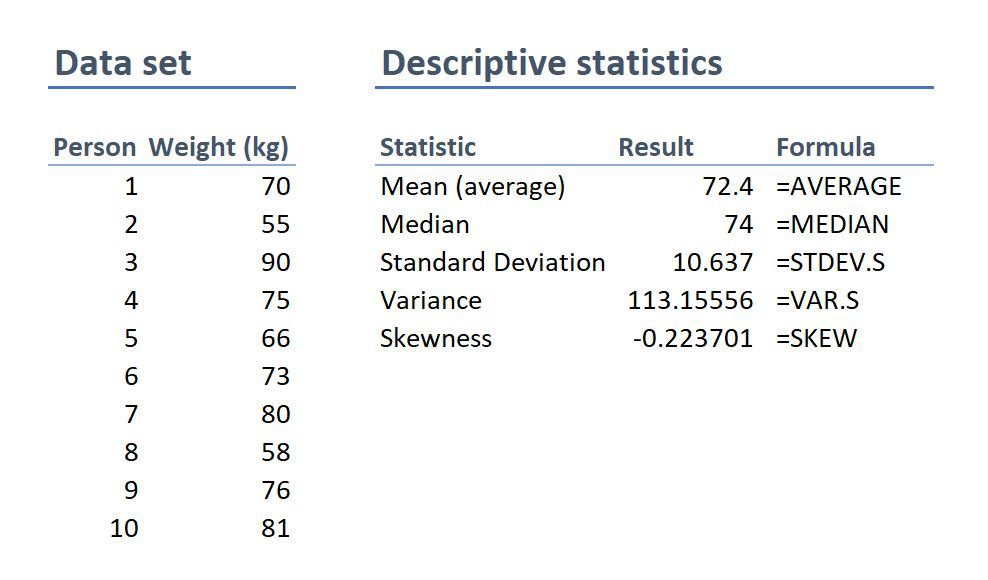

On the left-hand side is the data set. This details the bodyweight of a sample of 10 people. On the right-hand side, we have the descriptive statistics. Let’s take a look at each of them.

First, we can see that the mean weight is 72.4 kilograms. In other words, the average weight across the sample is 72.4 kilograms. Straightforward.

Next, we can see that the median is very similar to the mean (the average). This suggests that this data set has a reasonably symmetrical distribution (in other words, a relatively smooth, centred distribution of weights, clustered towards the centre).

In terms of the mode , there is no mode in this data set. This is because each number is present only once and so there cannot be a “most common number”. If there were two people who were both 65 kilograms, for example, then the mode would be 65.

Next up is the standard deviation . 10.6 indicates that there’s quite a wide spread of numbers. We can see this quite easily by looking at the numbers themselves, which range from 55 to 90, which is quite a stretch from the mean of 72.4.

And lastly, the skewness of -0.2 tells us that the data is very slightly negatively skewed. This makes sense since the mean and the median are slightly different.

As you can see, these descriptive statistics give us some useful insight into the data set. Of course, this is a very small data set (only 10 records), so we can’t read into these statistics too much. Also, keep in mind that this is not a list of all possible descriptive statistics – just the most common ones.

But why do all of these numbers matter?

While these descriptive statistics are all fairly basic, they’re important for a few reasons:

- Firstly, they help you get both a macro and micro-level view of your data. In other words, they help you understand both the big picture and the finer details.

- Secondly, they help you spot potential errors in the data – for example, if an average is way higher than you’d expect, or responses to a question are highly varied, this can act as a warning sign that you need to double-check the data.

- And lastly, these descriptive statistics help inform which inferential statistical techniques you can use, as those techniques depend on the skewness (in other words, the symmetry and normality) of the data.

Simply put, descriptive statistics are really important , even though the statistical techniques used are fairly basic. All too often at Grad Coach, we see students skimming over the descriptives in their eagerness to get to the more exciting inferential methods, and then landing up with some very flawed results.

Don’t be a sucker – give your descriptive statistics the love and attention they deserve!

Branch 2: Inferential Statistics

As I mentioned, while descriptive statistics are all about the details of your specific data set – your sample – inferential statistics aim to make inferences about the population . In other words, you’ll use inferential statistics to make predictions about what you’d expect to find in the full population.

What kind of predictions, you ask? Well, there are two common types of predictions that researchers try to make using inferential stats:

- Firstly, predictions about differences between groups – for example, height differences between children grouped by their favourite meal or gender.

- And secondly, relationships between variables – for example, the relationship between body weight and the number of hours a week a person does yoga.

In other words, inferential statistics (when done correctly), allow you to connect the dots and make predictions about what you expect to see in the real world population, based on what you observe in your sample data. For this reason, inferential statistics are used for hypothesis testing – in other words, to test hypotheses that predict changes or differences.

Of course, when you’re working with inferential statistics, the composition of your sample is really important. In other words, if your sample doesn’t accurately represent the population you’re researching, then your findings won’t necessarily be very useful.

For example, if your population of interest is a mix of 50% male and 50% female , but your sample is 80% male , you can’t make inferences about the population based on your sample, since it’s not representative. This area of statistics is called sampling, but we won’t go down that rabbit hole here (it’s a deep one!) – we’ll save that for another post .

What statistics are usually used in this branch?

There are many, many different statistical analysis methods within the inferential branch and it’d be impossible for us to discuss them all here. So we’ll just take a look at some of the most common inferential statistical methods so that you have a solid starting point.

First up are T-Tests . T-tests compare the means (the averages) of two groups of data to assess whether they’re statistically significantly different. In other words, do they have significantly different means, standard deviations and skewness.

This type of testing is very useful for understanding just how similar or different two groups of data are. For example, you might want to compare the mean blood pressure between two groups of people – one that has taken a new medication and one that hasn’t – to assess whether they are significantly different.

Kicking things up a level, we have ANOVA, which stands for “analysis of variance”. This test is similar to a T-test in that it compares the means of various groups, but ANOVA allows you to analyse multiple groups , not just two groups So it’s basically a t-test on steroids…

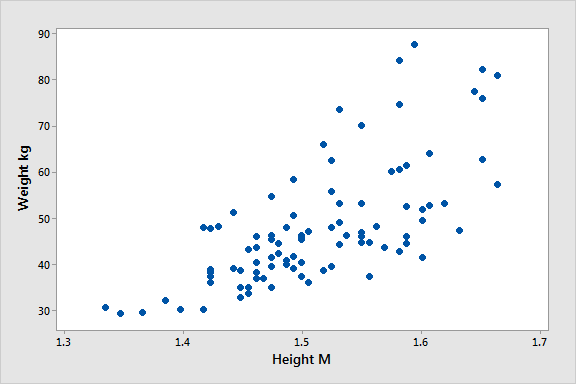

Next, we have correlation analysis . This type of analysis assesses the relationship between two variables. In other words, if one variable increases, does the other variable also increase, decrease or stay the same. For example, if the average temperature goes up, do average ice creams sales increase too? We’d expect some sort of relationship between these two variables intuitively , but correlation analysis allows us to measure that relationship scientifically .

Lastly, we have regression analysis – this is quite similar to correlation in that it assesses the relationship between variables, but it goes a step further to understand cause and effect between variables, not just whether they move together. In other words, does the one variable actually cause the other one to move, or do they just happen to move together naturally thanks to another force? Just because two variables correlate doesn’t necessarily mean that one causes the other.

Stats overload…

I hear you. To make this all a little more tangible, let’s take a look at an example of a correlation in action.

Here’s a scatter plot demonstrating the correlation (relationship) between weight and height. Intuitively, we’d expect there to be some relationship between these two variables, which is what we see in this scatter plot. In other words, the results tend to cluster together in a diagonal line from bottom left to top right.

As I mentioned, these are are just a handful of inferential techniques – there are many, many more. Importantly, each statistical method has its own assumptions and limitations .

For example, some methods only work with normally distributed (parametric) data, while other methods are designed specifically for non-parametric data. And that’s exactly why descriptive statistics are so important – they’re the first step to knowing which inferential techniques you can and can’t use.

How to choose the right analysis method

To choose the right statistical methods, you need to think about two important factors :

- The type of quantitative data you have (specifically, level of measurement and the shape of the data). And,

- Your research questions and hypotheses

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

Factor 1 – Data type

The first thing you need to consider is the type of data you’ve collected (or the type of data you will collect). By data types, I’m referring to the four levels of measurement – namely, nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio. If you’re not familiar with this lingo, check out the video below.

Why does this matter?

Well, because different statistical methods and techniques require different types of data. This is one of the “assumptions” I mentioned earlier – every method has its assumptions regarding the type of data.

For example, some techniques work with categorical data (for example, yes/no type questions, or gender or ethnicity), while others work with continuous numerical data (for example, age, weight or income) – and, of course, some work with multiple data types.

If you try to use a statistical method that doesn’t support the data type you have, your results will be largely meaningless . So, make sure that you have a clear understanding of what types of data you’ve collected (or will collect). Once you have this, you can then check which statistical methods would support your data types here .

If you haven’t collected your data yet, you can work in reverse and look at which statistical method would give you the most useful insights, and then design your data collection strategy to collect the correct data types.

Another important factor to consider is the shape of your data . Specifically, does it have a normal distribution (in other words, is it a bell-shaped curve, centred in the middle) or is it very skewed to the left or the right? Again, different statistical techniques work for different shapes of data – some are designed for symmetrical data while others are designed for skewed data.

This is another reminder of why descriptive statistics are so important – they tell you all about the shape of your data.

Factor 2: Your research questions

The next thing you need to consider is your specific research questions, as well as your hypotheses (if you have some). The nature of your research questions and research hypotheses will heavily influence which statistical methods and techniques you should use.

If you’re just interested in understanding the attributes of your sample (as opposed to the entire population), then descriptive statistics are probably all you need. For example, if you just want to assess the means (averages) and medians (centre points) of variables in a group of people.

On the other hand, if you aim to understand differences between groups or relationships between variables and to infer or predict outcomes in the population, then you’ll likely need both descriptive statistics and inferential statistics.

So, it’s really important to get very clear about your research aims and research questions, as well your hypotheses – before you start looking at which statistical techniques to use.

Never shoehorn a specific statistical technique into your research just because you like it or have some experience with it. Your choice of methods must align with all the factors we’ve covered here.

Time to recap…

You’re still with me? That’s impressive. We’ve covered a lot of ground here, so let’s recap on the key points:

- Quantitative data analysis is all about analysing number-based data (which includes categorical and numerical data) using various statistical techniques.

- The two main branches of statistics are descriptive statistics and inferential statistics . Descriptives describe your sample, whereas inferentials make predictions about what you’ll find in the population.

- Common descriptive statistical methods include mean (average), median , standard deviation and skewness .

- Common inferential statistical methods include t-tests , ANOVA , correlation and regression analysis.

- To choose the right statistical methods and techniques, you need to consider the type of data you’re working with , as well as your research questions and hypotheses.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

77 Comments

Hi, I have read your article. Such a brilliant post you have created.

Thank you for the feedback. Good luck with your quantitative analysis.

Thank you so much.

Thank you so much. I learnt much well. I love your summaries of the concepts. I had love you to explain how to input data using SPSS

Very useful, I have got the concept

Amazing and simple way of breaking down quantitative methods.

This is beautiful….especially for non-statisticians. I have skimmed through but I wish to read again. and please include me in other articles of the same nature when you do post. I am interested. I am sure, I could easily learn from you and get off the fear that I have had in the past. Thank you sincerely.

Send me every new information you might have.

i need every new information

Thank you for the blog. It is quite informative. Dr Peter Nemaenzhe PhD

It is wonderful. l’ve understood some of the concepts in a more compréhensive manner

Your article is so good! However, I am still a bit lost. I am doing a secondary research on Gun control in the US and increase in crime rates and I am not sure which analysis method I should use?

Based on the given learning points, this is inferential analysis, thus, use ‘t-tests, ANOVA, correlation and regression analysis’

Well explained notes. Am an MPH student and currently working on my thesis proposal, this has really helped me understand some of the things I didn’t know.

I like your page..helpful

wonderful i got my concept crystal clear. thankyou!!

This is really helpful , thank you

Thank you so much this helped

Wonderfully explained

thank u so much, it was so informative

THANKYOU, this was very informative and very helpful

This is great GRADACOACH I am not a statistician but I require more of this in my thesis

Include me in your posts.

This is so great and fully useful. I would like to thank you again and again.

Glad to read this article. I’ve read lot of articles but this article is clear on all concepts. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you so much. This is a very good foundation and intro into quantitative data analysis. Appreciate!

You have a very impressive, simple but concise explanation of data analysis for Quantitative Research here. This is a God-send link for me to appreciate research more. Thank you so much!

Avery good presentation followed by the write up. yes you simplified statistics to make sense even to a layman like me. Thank so much keep it up. The presenter did ell too. i would like more of this for Qualitative and exhaust more of the test example like the Anova.

This is a very helpful article, couldn’t have been clearer. Thank you.

Awesome and phenomenal information.Well done

The video with the accompanying article is super helpful to demystify this topic. Very well done. Thank you so much.

thank you so much, your presentation helped me a lot

I don’t know how should I express that ur article is saviour for me 🥺😍

It is well defined information and thanks for sharing. It helps me a lot in understanding the statistical data.

I gain a lot and thanks for sharing brilliant ideas, so wish to be linked on your email update.

Very helpful and clear .Thank you Gradcoach.

Thank for sharing this article, well organized and information presented are very clear.

VERY INTERESTING AND SUPPORTIVE TO NEW RESEARCHERS LIKE ME. AT LEAST SOME BASICS ABOUT QUANTITATIVE.

An outstanding, well explained and helpful article. This will help me so much with my data analysis for my research project. Thank you!

wow this has just simplified everything i was scared of how i am gonna analyse my data but thanks to you i will be able to do so

simple and constant direction to research. thanks

This is helpful

Great writing!! Comprehensive and very helpful.

Do you provide any assistance for other steps of research methodology like making research problem testing hypothesis report and thesis writing?

Thank you so much for such useful article!

Amazing article. So nicely explained. Wow

Very insightfull. Thanks

I am doing a quality improvement project to determine if the implementation of a protocol will change prescribing habits. Would this be a t-test?

The is a very helpful blog, however, I’m still not sure how to analyze my data collected. I’m doing a research on “Free Education at the University of Guyana”

tnx. fruitful blog!

So I am writing exams and would like to know how do establish which method of data analysis to use from the below research questions: I am a bit lost as to how I determine the data analysis method from the research questions.

Do female employees report higher job satisfaction than male employees with similar job descriptions across the South African telecommunications sector? – I though that maybe Chi Square could be used here. – Is there a gender difference in talented employees’ actual turnover decisions across the South African telecommunications sector? T-tests or Correlation in this one. – Is there a gender difference in the cost of actual turnover decisions across the South African telecommunications sector? T-tests or Correlation in this one. – What practical recommendations can be made to the management of South African telecommunications companies on leveraging gender to mitigate employee turnover decisions?

Your assistance will be appreciated if I could get a response as early as possible tomorrow

This was quite helpful. Thank you so much.

wow I got a lot from this article, thank you very much, keep it up

Thanks for yhe guidance. Can you send me this guidance on my email? To enable offline reading?

Thank you very much, this service is very helpful.

Every novice researcher needs to read this article as it puts things so clear and easy to follow. Its been very helpful.

Wonderful!!!! you explained everything in a way that anyone can learn. Thank you!!

I really enjoyed reading though this. Very easy to follow. Thank you

Many thanks for your useful lecture, I would be really appreciated if you could possibly share with me the PPT of presentation related to Data type?

Thank you very much for sharing, I got much from this article

This is a very informative write-up. Kindly include me in your latest posts.

Very interesting mostly for social scientists

Thank you so much, very helpfull

You’re welcome 🙂

woow, its great, its very informative and well understood because of your way of writing like teaching in front of me in simple languages.

I have been struggling to understand a lot of these concepts. Thank you for the informative piece which is written with outstanding clarity.

very informative article. Easy to understand

Beautiful read, much needed.

Always greet intro and summary. I learn so much from GradCoach

Quite informative. Simple and clear summary.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your informative and inspiring piece. Your profound insights into this topic truly provide a better understanding of its complexity. I agree with the points you raised, especially when you delved into the specifics of the article. In my opinion, that aspect is often overlooked and deserves further attention.

Absolutely!!! Thank you

Thank you very much for this post. It made me to understand how to do my data analysis.

its nice work and excellent job ,you have made my work easier

Wow! So explicit. Well done.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

8 Types of Data Analysis

The different types of data analysis include descriptive, diagnostic, exploratory, inferential, predictive, causal, mechanistic and prescriptive. Here’s what you need to know about each one.

Data analysis is an aspect of data science and data analytics that is all about analyzing data for different kinds of purposes. The data analysis process involves inspecting, cleaning, transforming and modeling data to draw useful insights from it.

Types of Data Analysis

- Descriptive analysis

- Diagnostic analysis

- Exploratory analysis

- Inferential analysis

- Predictive analysis

- Causal analysis

- Mechanistic analysis

- Prescriptive analysis

With its multiple facets, methodologies and techniques, data analysis is used in a variety of fields, including energy, healthcare and marketing, among others. As businesses thrive under the influence of technological advancements in data analytics, data analysis plays a huge role in decision-making , providing a better, faster and more effective system that minimizes risks and reduces human biases .

That said, there are different kinds of data analysis with different goals. We’ll examine each one below.

Two Camps of Data Analysis

Data analysis can be divided into two camps, according to the book R for Data Science :

- Hypothesis Generation: This involves looking deeply at the data and combining your domain knowledge to generate hypotheses about why the data behaves the way it does.

- Hypothesis Confirmation: This involves using a precise mathematical model to generate falsifiable predictions with statistical sophistication to confirm your prior hypotheses.

More on Data Analysis: Data Analyst vs. Data Scientist: Similarities and Differences Explained

Data analysis can be separated and organized into types, arranged in an increasing order of complexity.

1. Descriptive Analysis

The goal of descriptive analysis is to describe or summarize a set of data . Here’s what you need to know:

- Descriptive analysis is the very first analysis performed in the data analysis process.

- It generates simple summaries of samples and measurements.

- It involves common, descriptive statistics like measures of central tendency, variability, frequency and position.

Descriptive Analysis Example

Take the Covid-19 statistics page on Google, for example. The line graph is a pure summary of the cases/deaths, a presentation and description of the population of a particular country infected by the virus.

Descriptive analysis is the first step in analysis where you summarize and describe the data you have using descriptive statistics, and the result is a simple presentation of your data.

2. Diagnostic Analysis

Diagnostic analysis seeks to answer the question “Why did this happen?” by taking a more in-depth look at data to uncover subtle patterns. Here’s what you need to know:

- Diagnostic analysis typically comes after descriptive analysis, taking initial findings and investigating why certain patterns in data happen.

- Diagnostic analysis may involve analyzing other related data sources, including past data, to reveal more insights into current data trends.

- Diagnostic analysis is ideal for further exploring patterns in data to explain anomalies .

Diagnostic Analysis Example

A footwear store wants to review its website traffic levels over the previous 12 months. Upon compiling and assessing the data, the company’s marketing team finds that June experienced above-average levels of traffic while July and August witnessed slightly lower levels of traffic.

To find out why this difference occurred, the marketing team takes a deeper look. Team members break down the data to focus on specific categories of footwear. In the month of June, they discovered that pages featuring sandals and other beach-related footwear received a high number of views while these numbers dropped in July and August.

Marketers may also review other factors like seasonal changes and company sales events to see if other variables could have contributed to this trend.

3. Exploratory Analysis (EDA)

Exploratory analysis involves examining or exploring data and finding relationships between variables that were previously unknown. Here’s what you need to know:

- EDA helps you discover relationships between measures in your data, which are not evidence for the existence of the correlation, as denoted by the phrase, “ Correlation doesn’t imply causation .”

- It’s useful for discovering new connections and forming hypotheses. It drives design planning and data collection .

Exploratory Analysis Example

Climate change is an increasingly important topic as the global temperature has gradually risen over the years. One example of an exploratory data analysis on climate change involves taking the rise in temperature over the years from 1950 to 2020 and the increase of human activities and industrialization to find relationships from the data. For example, you may increase the number of factories, cars on the road and airplane flights to see how that correlates with the rise in temperature.

Exploratory analysis explores data to find relationships between measures without identifying the cause. It’s most useful when formulating hypotheses.

4. Inferential Analysis

Inferential analysis involves using a small sample of data to infer information about a larger population of data.

The goal of statistical modeling itself is all about using a small amount of information to extrapolate and generalize information to a larger group. Here’s what you need to know:

- Inferential analysis involves using estimated data that is representative of a population and gives a measure of uncertainty or standard deviation to your estimation.

- The accuracy of inference depends heavily on your sampling scheme. If the sample isn’t representative of the population, the generalization will be inaccurate. This is known as the central limit theorem .

Inferential Analysis Example

A psychological study on the benefits of sleep might have a total of 500 people involved. When they followed up with the candidates, the candidates reported to have better overall attention spans and well-being with seven to nine hours of sleep, while those with less sleep and more sleep than the given range suffered from reduced attention spans and energy. This study drawn from 500 people was just a tiny portion of the 7 billion people in the world, and is thus an inference of the larger population.

Inferential analysis extrapolates and generalizes the information of the larger group with a smaller sample to generate analysis and predictions.

5. Predictive Analysis

Predictive analysis involves using historical or current data to find patterns and make predictions about the future. Here’s what you need to know:

- The accuracy of the predictions depends on the input variables.

- Accuracy also depends on the types of models. A linear model might work well in some cases, and in other cases it might not.

- Using a variable to predict another one doesn’t denote a causal relationship.

Predictive Analysis Example

The 2020 United States election is a popular topic and many prediction models are built to predict the winning candidate. FiveThirtyEight did this to forecast the 2016 and 2020 elections. Prediction analysis for an election would require input variables such as historical polling data, trends and current polling data in order to return a good prediction. Something as large as an election wouldn’t just be using a linear model, but a complex model with certain tunings to best serve its purpose.

6. Causal Analysis

Causal analysis looks at the cause and effect of relationships between variables and is focused on finding the cause of a correlation. This way, researchers can examine how a change in one variable affects another. Here’s what you need to know:

- To find the cause, you have to question whether the observed correlations driving your conclusion are valid. Just looking at the surface data won’t help you discover the hidden mechanisms underlying the correlations.

- Causal analysis is applied in randomized studies focused on identifying causation.

- Causal analysis is the gold standard in data analysis and scientific studies where the cause of a phenomenon is to be extracted and singled out, like separating wheat from chaff.

- Good data is hard to find and requires expensive research and studies. These studies are analyzed in aggregate (multiple groups), and the observed relationships are just average effects (mean) of the whole population. This means the results might not apply to everyone.

Causal Analysis Example

Say you want to test out whether a new drug improves human strength and focus. To do that, you perform randomized control trials for the drug to test its effect. You compare the sample of candidates for your new drug against the candidates receiving a mock control drug through a few tests focused on strength and overall focus and attention. This will allow you to observe how the drug affects the outcome.

7. Mechanistic Analysis

Mechanistic analysis is used to understand exact changes in variables that lead to other changes in other variables . In some ways, it is a predictive analysis, but it’s modified to tackle studies that require high precision and meticulous methodologies for physical or engineering science. Here’s what you need to know:

- It’s applied in physical or engineering sciences, situations that require high precision and little room for error, only noise in data is measurement error.

- It’s designed to understand a biological or behavioral process, the pathophysiology of a disease or the mechanism of action of an intervention.

Mechanistic Analysis Example

Say an experiment is done to simulate safe and effective nuclear fusion to power the world. A mechanistic analysis of the study would entail a precise balance of controlling and manipulating variables with highly accurate measures of both variables and the desired outcomes. It’s this intricate and meticulous modus operandi toward these big topics that allows for scientific breakthroughs and advancement of society.

8. Prescriptive Analysis

Prescriptive analysis compiles insights from other previous data analyses and determines actions that teams or companies can take to prepare for predicted trends. Here’s what you need to know:

- Prescriptive analysis may come right after predictive analysis, but it may involve combining many different data analyses.

- Companies need advanced technology and plenty of resources to conduct prescriptive analysis. Artificial intelligence systems that process data and adjust automated tasks are an example of the technology required to perform prescriptive analysis.

Prescriptive Analysis Example

Prescriptive analysis is pervasive in everyday life, driving the curated content users consume on social media. On platforms like TikTok and Instagram, algorithms can apply prescriptive analysis to review past content a user has engaged with and the kinds of behaviors they exhibited with specific posts. Based on these factors, an algorithm seeks out similar content that is likely to elicit the same response and recommends it on a user’s personal feed.

More on Data Explaining the Empirical Rule for Normal Distribution

When to Use the Different Types of Data Analysis

- Descriptive analysis summarizes the data at hand and presents your data in a comprehensible way.

- Diagnostic analysis takes a more detailed look at data to reveal why certain patterns occur, making it a good method for explaining anomalies.

- Exploratory data analysis helps you discover correlations and relationships between variables in your data.

- Inferential analysis is for generalizing the larger population with a smaller sample size of data.

- Predictive analysis helps you make predictions about the future with data.

- Causal analysis emphasizes finding the cause of a correlation between variables.

- Mechanistic analysis is for measuring the exact changes in variables that lead to other changes in other variables.

- Prescriptive analysis combines insights from different data analyses to develop a course of action teams and companies can take to capitalize on predicted outcomes.

A few important tips to remember about data analysis include:

- Correlation doesn’t imply causation.

- EDA helps discover new connections and form hypotheses.

- Accuracy of inference depends on the sampling scheme.

- A good prediction depends on the right input variables.

- A simple linear model with enough data usually does the trick.

- Using a variable to predict another doesn’t denote causal relationships.

- Good data is hard to find, and to produce it requires expensive research.

- Results from studies are done in aggregate and are average effects and might not apply to everyone.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an example of data analysis.

A marketing team reviews a company’s web traffic over the past 12 months. To understand why sales rise and fall during certain months, the team breaks down the data to look at shoe type, seasonal patterns and sales events. Based on this in-depth analysis, the team can determine variables that influenced web traffic and make adjustments as needed.

How do you know which data analysis method to use?

Selecting a data analysis method depends on the goals of the analysis and the complexity of the task, among other factors. It’s best to assess the circumstances and consider the pros and cons of each type of data analysis before moving forward with a particular method.

Recent Data Science Articles

What is Data Analysis? (Types, Methods, and Tools)

- Couchbase Product Marketing December 17, 2023

Data analysis is the process of cleaning, transforming, and interpreting data to uncover insights, patterns, and trends. It plays a crucial role in decision making, problem solving, and driving innovation across various domains.

In addition to further exploring the role data analysis plays this blog post will discuss common data analysis techniques, delve into the distinction between quantitative and qualitative data, explore popular data analysis tools, and discuss the steps involved in the data analysis process.

By the end, you should have a deeper understanding of data analysis and its applications, empowering you to harness the power of data to make informed decisions and gain actionable insights.

Why is Data Analysis Important?

Data analysis is important across various domains and industries. It helps with:

- Decision Making : Data analysis provides valuable insights that support informed decision making, enabling organizations to make data-driven choices for better outcomes.

- Problem Solving : Data analysis helps identify and solve problems by uncovering root causes, detecting anomalies, and optimizing processes for increased efficiency.

- Performance Evaluation : Data analysis allows organizations to evaluate performance, track progress, and measure success by analyzing key performance indicators (KPIs) and other relevant metrics.

- Gathering Insights : Data analysis uncovers valuable insights that drive innovation, enabling businesses to develop new products, services, and strategies aligned with customer needs and market demand.

- Risk Management : Data analysis helps mitigate risks by identifying risk factors and enabling proactive measures to minimize potential negative impacts.

By leveraging data analysis, organizations can gain a competitive advantage, improve operational efficiency, and make smarter decisions that positively impact the bottom line.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Data

In data analysis, you’ll commonly encounter two types of data: quantitative and qualitative. Understanding the differences between these two types of data is essential for selecting appropriate analysis methods and drawing meaningful insights. Here’s an overview of quantitative and qualitative data:

Quantitative Data

Quantitative data is numerical and represents quantities or measurements. It’s typically collected through surveys, experiments, and direct measurements. This type of data is characterized by its ability to be counted, measured, and subjected to mathematical calculations. Examples of quantitative data include age, height, sales figures, test scores, and the number of website users.

Quantitative data has the following characteristics:

- Numerical : Quantitative data is expressed in numerical values that can be analyzed and manipulated mathematically.

- Objective : Quantitative data is objective and can be measured and verified independently of individual interpretations.

- Statistical Analysis : Quantitative data lends itself well to statistical analysis. It allows for applying various statistical techniques, such as descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, regression analysis, and hypothesis testing.

- Generalizability : Quantitative data often aims to generalize findings to a larger population. It allows for making predictions, estimating probabilities, and drawing statistical inferences.

Qualitative Data

Qualitative data, on the other hand, is non-numerical and is collected through interviews, observations, and open-ended survey questions. It focuses on capturing rich, descriptive, and subjective information to gain insights into people’s opinions, attitudes, experiences, and behaviors. Examples of qualitative data include interview transcripts, field notes, survey responses, and customer feedback.

Qualitative data has the following characteristics:

- Descriptive : Qualitative data provides detailed descriptions, narratives, or interpretations of phenomena, often capturing context, emotions, and nuances.

- Subjective : Qualitative data is subjective and influenced by the individuals’ perspectives, experiences, and interpretations.

- Interpretive Analysis : Qualitative data requires interpretive techniques, such as thematic analysis, content analysis, and discourse analysis, to uncover themes, patterns, and underlying meanings.

- Contextual Understanding : Qualitative data emphasizes understanding the social, cultural, and contextual factors that shape individuals’ experiences and behaviors.

- Rich Insights : Qualitative data enables researchers to gain in-depth insights into complex phenomena and explore research questions in greater depth.

In summary, quantitative data represents numerical quantities and lends itself well to statistical analysis, while qualitative data provides rich, descriptive insights into subjective experiences and requires interpretive analysis techniques. Understanding the differences between quantitative and qualitative data is crucial for selecting appropriate analysis methods and drawing meaningful conclusions in research and data analysis.

Types of Data Analysis

Different types of data analysis techniques serve different purposes. In this section, we’ll explore four types of data analysis: descriptive, diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive, and go over how you can use them.

Descriptive Analysis

Descriptive analysis involves summarizing and describing the main characteristics of a dataset. It focuses on gaining a comprehensive understanding of the data through measures such as central tendency (mean, median, mode), dispersion (variance, standard deviation), and graphical representations (histograms, bar charts). For example, in a retail business, descriptive analysis may involve analyzing sales data to identify average monthly sales, popular products, or sales distribution across different regions.

Diagnostic Analysis

Diagnostic analysis aims to understand the causes or factors influencing specific outcomes or events. It involves investigating relationships between variables and identifying patterns or anomalies in the data. Diagnostic analysis often uses regression analysis, correlation analysis, and hypothesis testing to uncover the underlying reasons behind observed phenomena. For example, in healthcare, diagnostic analysis could help determine factors contributing to patient readmissions and identify potential improvements in the care process.

Predictive Analysis

Predictive analysis focuses on making predictions or forecasts about future outcomes based on historical data. It utilizes statistical models, machine learning algorithms, and time series analysis to identify patterns and trends in the data. By applying predictive analysis, businesses can anticipate customer behavior, market trends, or demand for products and services. For example, an e-commerce company might use predictive analysis to forecast customer churn and take proactive measures to retain customers.

Prescriptive Analysis

Prescriptive analysis takes predictive analysis a step further by providing recommendations or optimal solutions based on the predicted outcomes. It combines historical and real-time data with optimization techniques, simulation models, and decision-making algorithms to suggest the best course of action. Prescriptive analysis helps organizations make data-driven decisions and optimize their strategies. For example, a logistics company can use prescriptive analysis to determine the most efficient delivery routes, considering factors like traffic conditions, fuel costs, and customer preferences.

In summary, data analysis plays a vital role in extracting insights and enabling informed decision making. Descriptive analysis helps understand the data, diagnostic analysis uncovers the underlying causes, predictive analysis forecasts future outcomes, and prescriptive analysis provides recommendations for optimal actions. These different data analysis techniques are valuable tools for businesses and organizations across various industries.

Data Analysis Methods

In addition to the data analysis types discussed earlier, you can use various methods to analyze data effectively. These methods provide a structured approach to extract insights, detect patterns, and derive meaningful conclusions from the available data. Here are some commonly used data analysis methods:

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis involves applying statistical techniques to data to uncover patterns, relationships, and trends. It includes methods such as hypothesis testing, regression analysis, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and chi-square tests. Statistical analysis helps organizations understand the significance of relationships between variables and make inferences about the population based on sample data. For example, a market research company could conduct a survey to analyze the relationship between customer satisfaction and product price. They can use regression analysis to determine whether there is a significant correlation between these variables.

Data Mining

Data mining refers to the process of discovering patterns and relationships in large datasets using techniques such as clustering, classification, association analysis, and anomaly detection. It involves exploring data to identify hidden patterns and gain valuable insights. For example, a telecommunications company could analyze customer call records to identify calling patterns and segment customers into groups based on their calling behavior.

Text Mining

Text mining involves analyzing unstructured data , such as customer reviews, social media posts, or emails, to extract valuable information and insights. It utilizes techniques like natural language processing (NLP), sentiment analysis, and topic modeling to analyze and understand textual data. For example, consider how a hotel chain might analyze customer reviews from various online platforms to identify common themes and sentiment patterns to improve customer satisfaction.

Time Series Analysis

Time series analysis focuses on analyzing data collected over time to identify trends, seasonality, and patterns. It involves techniques such as forecasting, decomposition, and autocorrelation analysis to make predictions and understand the underlying patterns in the data.

For example, an energy company could analyze historical electricity consumption data to forecast future demand and optimize energy generation and distribution.

Data Visualization

Data visualization is the graphical representation of data to communicate patterns, trends, and insights visually. It uses charts, graphs, maps, and other visual elements to present data in a visually appealing and easily understandable format. For example, a sales team might use a line chart to visualize monthly sales trends and identify seasonal patterns in their sales data.

These are just a few examples of the data analysis methods you can use. Your choice should depend on the nature of the data, the research question or problem, and the desired outcome.

How to Analyze Data

Analyzing data involves following a systematic approach to extract insights and derive meaningful conclusions. Here are some steps to guide you through the process of analyzing data effectively:

Define the Objective : Clearly define the purpose and objective of your data analysis. Identify the specific question or problem you want to address through analysis.

Prepare and Explore the Data : Gather the relevant data and ensure its quality. Clean and preprocess the data by handling missing values, duplicates, and formatting issues. Explore the data using descriptive statistics and visualizations to identify patterns, outliers, and relationships.

Apply Analysis Techniques : Choose the appropriate analysis techniques based on your data and research question. Apply statistical methods, machine learning algorithms, and other analytical tools to derive insights and answer your research question.

Interpret the Results : Analyze the output of your analysis and interpret the findings in the context of your objective. Identify significant patterns, trends, and relationships in the data. Consider the implications and practical relevance of the results.

Communicate and Take Action : Communicate your findings effectively to stakeholders or intended audiences. Present the results clearly and concisely, using visualizations and reports. Use the insights from the analysis to inform decision making.

Remember, data analysis is an iterative process, and you may need to revisit and refine your analysis as you progress. These steps provide a general framework to guide you through the data analysis process and help you derive meaningful insights from your data.

Data Analysis Tools

Data analysis tools are software applications and platforms designed to facilitate the process of analyzing and interpreting data . These tools provide a range of functionalities to handle data manipulation, visualization, statistical analysis, and machine learning. Here are some commonly used data analysis tools:

Spreadsheet Software

Tools like Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets, and Apple Numbers are used for basic data analysis tasks. They offer features for data entry, manipulation, basic statistical functions, and simple visualizations.

Business Intelligence (BI) Platforms

BI platforms like Microsoft Power BI, Tableau, and Looker integrate data from multiple sources, providing comprehensive views of business performance through interactive dashboards, reports, and ad hoc queries.

Programming Languages and Libraries