Sourcing in an essay Word Hike [ Answer ]

- by Game Answer

- 2022-10-18 2024-07-08

This topic will be an exclusive one that will provide you the answers of Word Hike Sourcing in an essay , appeared on level 3877. This game is developed by Joy Vendor a famous one known in puzzle games for ios and android devices. From Now on, you will have all the hints, cheats and needed answers to complete this puzzle.You will have in this game to find the words from the clues in order to fulfill the board and find the words of the level. The game is new and we decided to cover it because it is a unique kind of crossword puzzle games.

Word Hike Sourcing in an essay Answers:

PS: if you are looking for another level answers, you will find them in the below topic :

Word Hike Answers

- Referencing

After achieving this level, you can comeback to : Word Hike Level 3877 Or get the answer of the next puzzle here : The ability to move from one place to another I Hope you found the word you searched for.

If you have any suggestion, please feel free to comment this topic.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sourcing in an essay Word Hike – Answers

Few minutes ago, I was playing the game and trying to solve the Clue : Sourcing in an essay in the themed crossword of the game Word Hike and I was able to find the answers. Now, I can reveal the words that may help all the upcoming players.

Now, I will reveal the answer for this clue : And about the game answers of Word Hike, they will be up to date during the lifetime of the game.

Answers of Word Hike Sourcing in an essay:

- Referencing

Please remember that I’ll always mention the master topic of the game : Word Hike Answers , the link to the previous Clue : Smooth the way and the link to the main level Word Hike level 3877 . You may want to know the content of nearby topics so these links will tell you about it !

Please let us know your thoughts. They are always welcome. So, have you thought about leaving a comment, to correct a mistake or to add an extra value to the topic ? I’m all ears.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Word Hike Sourcing in an essay answer

Sourcing in an essay, other questions from this puzzle:, more app solutions.

Sourcing 101

It is the bane of every undergraduate student when it comes to written assignments: finding good sources. One of the biggest gripes that new students have is how long it takes to find the correct sources for their paper. Especially in the case of evidence-based writing, finding the right sources and using them, more often than not, takes up more time than actually writing the paper itself. Given these challenges, here a few tips on how to help you find and use those quality sources.

Start early

The best piece of advice is to start your writing assignments early so that you have time to sift through the literature and find the best sources. Unfortunately, it is impossible to find good sources the night before an assignment is due, so starting a week or two earlier will help immensely.

Use scholarly search engines

Although very basic, this tip is very important. Search engines vary among discipline and it is essential to use one that is appropriate for your discipline. One way to find the right engine is using the Research and journal database from the University of Waterloo library . The engines are relatively easy to use and they can be a great resource for assignments that require you to find peer-reviewed journal articles.

Search for keywords

When you finally find an article, you can assess if it will be useful to your topic by searching for keywords. On a computer Ctrl+F (Command+F for mac users) can be really helpful for finding these keywords, and if they are nowhere to be found in the paper, you know right away that the article is not relevant.

Retrieved from: The Blue Diamond Gallery

Keep track of where to cite

It is better to mark a sentence that needs a citation as you write it. You can mark the sentence with parentheses at the end, which tells you that you need a citation there.

A good trick is to assign each of your sources a different letter. The letter is a placeholder for a specific source. Putting a letter in the parentheses tells you what source you are going to use there. A number after the letter can also make it even more specific by telling you what page of the source the information is on.

For example:

Amino acids are essential nutrients needed by all living things (A12).

The "A" is the letter of the source and the number 12 is the page number you can find the information being referred to.

Hopefully these tips come in handy the next time you have to hand in a ten-page assignment with references. These tips won’t help you write the paper, but at least you’ll have the references down.

- Current students ,

- Current undergraduate students ,

- Current graduate students

- Career Center

- Digital Events

- Member Benefits

- Membership Types

- My Account & Profile

- Chapters & Affiliates

- Awards & Recognition

- Write or Review for ILA

- Volunteer & Lead

- Children's Rights to Read

- Position Statements

- Literacy Glossary

- Literacy Today Magazine

- Literacy Now Blog

- Resource Collections

- Resources by Topic

- School-Based Solutions

- ILA Digital Events

- In-Person Events

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Press & Media

Literacy Now

- ILA Network

- Conferences & Events

- Literacy Leadership

- Teaching With Tech

- Purposeful Tech

- Book Reviews

- 5 Questions With...

- Anita's Picks

- Check It Out

- Teaching Tips

- In Other Words

- Putting Books to Work

- Tales Out of School

- Digital Literacies

- Foundational Skills

- Teacher Educator

- Reading Specialist

- Literacy Education Student

- Literacy Coach

- Classroom Teacher

- Job Functions

- Digital Literacy

- 21st Century Skills

Show Your Students Why Sourcing Matters

Many students struggle with sourcing , specifically, how to use source information to evaluate online sources or how to cite ones’ sources in the essay. Some students may not know how to source while others have knowledge about sourcing, but they don’t typically choose to apply that knowledge in practice This might be because they do not understand the value of sourcing.

When investigating how children respond to information differently from adults and how they select whom to trust, researchers Paul Harris and Kathleen Corriveau found that , even for children, the source of information matters. For example, when two caregivers presented different statements, the children turned to the more familiar caregiver for confirmation. Children seemed to be nonselective in what they learn from others, but not in whom they learn from. This kind of spontaneous attention to sources of information may serve as a starting point for educators when explaining to students why sourcing matters. So, let’s do that!

We will begin by sharing two examples that teachers could use to discuss the value of sourcing with their students. The first example from everyday life takes advantages of students’ spontaneous attention to sources and can also be used with younger students. The second example illustrates how information about the source may affect one's interpretation of a text's reliability. It also shows why one should pay attention to different aspects of the source during online inquiry.

When students have understood the value of source information, they may be better motivated to cite their sources when reporting the results of their online research in a way that serves their readers. To provide informative in-texts citations, students need some guidelines. Our third example introduces two dimensions that students can keep in mind when formulating in-text citations.

Example no. 1: Sourcing in everyday life

- After showing the first note, without the source, begin the conversation by asking students, “Would you like to know who has written the note? Why?”

- After revealing the three other notes and calling attention to the different signatures (or sources) of each, ask students, “How do you interpret and react to the notes with different sources (signatures)?"

Example no. 2: Sourcing when evaluating the reliability of a website

Discuss the value of sourcing by asking students to evaluate the reliability of a fictitious website after showing them one piece of source information at the time, as listed below.

- How reliable do you find the Web text that concerns health effects of chocolate when you know that:

- An expert working at the health institute has been interviewed for the text?

- The text has been published recently?

- The text has been written by a web designer?

- The text is published in the website of a chocolate manufacturer?

- How did your interpretations on reliability change after each new piece of information about the source?

- Do you think that one piece of information about the source is enough to make a proper conclusion about the reliability of the text? Why do you think so?

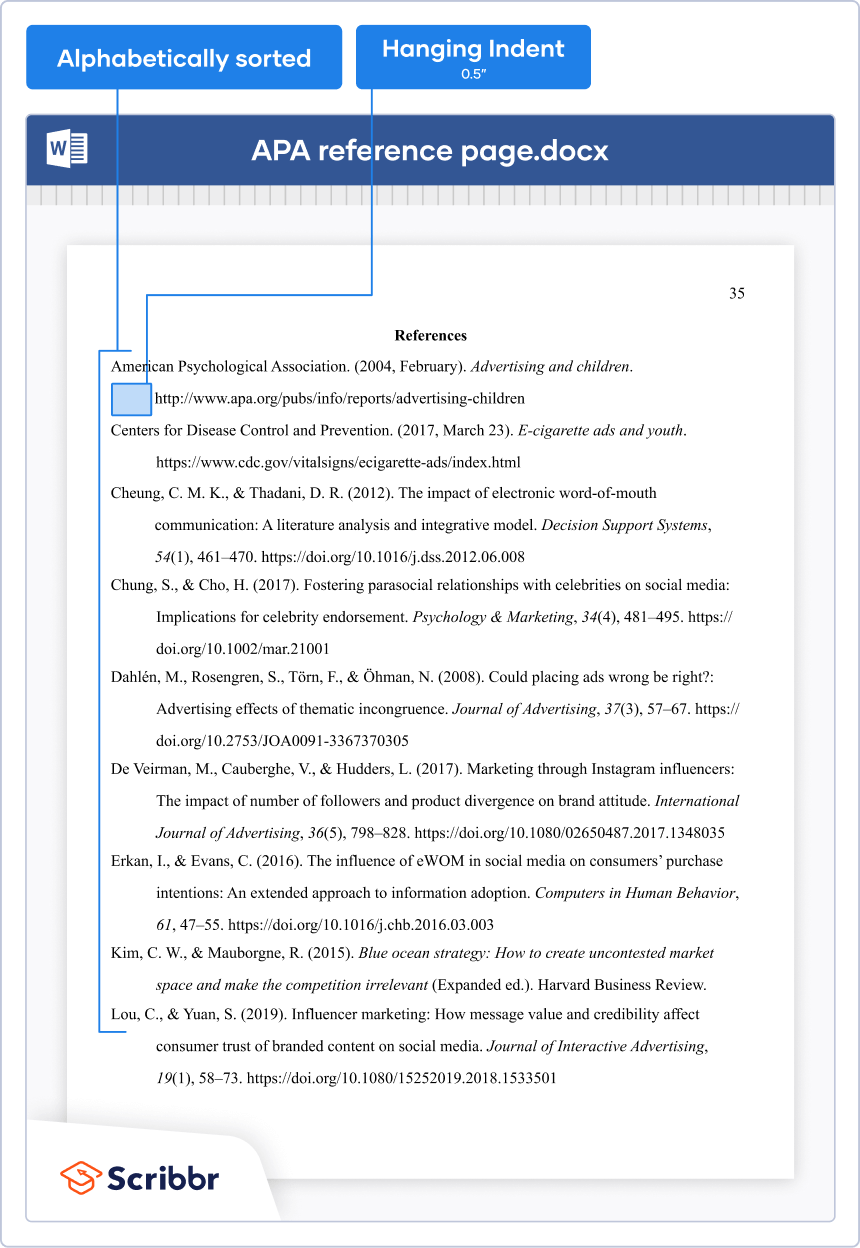

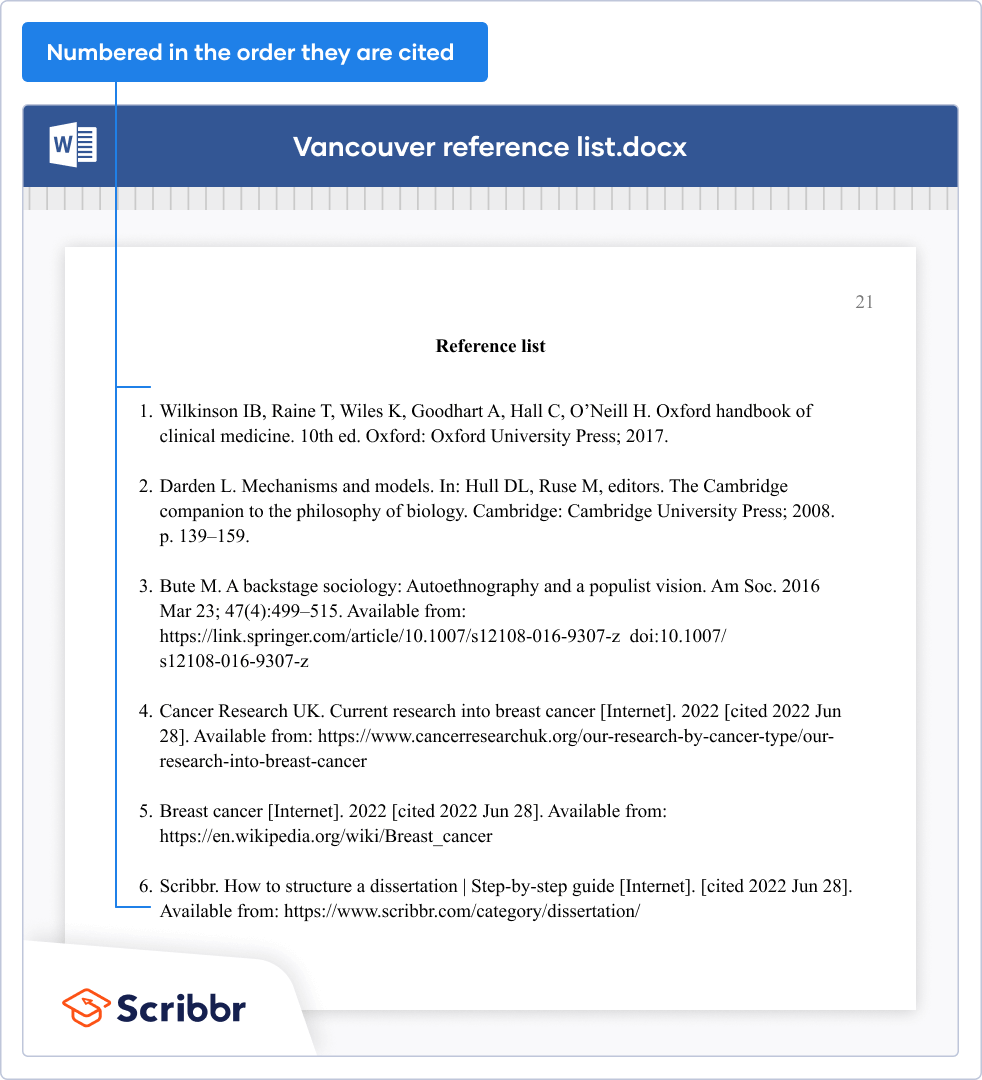

Example no. 3: How to cite your Web sources in an essay? When older students are asked to formulate in-text citations in their essays, it is important that their citations are both accurate and provides rich information about the source. An accurate citation provides precise information about the Web page that students had actually read (e.g., it is published by The Washington Post ). A citation that provides rich information includes two or more pieces of information that helps a reader to understand the nature of the source.

After explaining the dimensions, encourage your students to apply these principles in their essays.

Eva Wennås Brante is a senior lecturer at the University of Malmö, Sweden.

Carita Kiili is a postdoctoral fellows at the Department of Education at the University of Oslo. This article is part of a series from the International Literacy Association’s Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG) .

Integrating Technology and Multiple Texts to Promote Differentiation in Literacy Instruction Across the Discipline Integrating Social and Emotional Learning in the Classroom

- Conferences & Events

- Anita's Picks

Recent Posts

- “A Steel Magnolia”: Remembering Linda B. Gambrell, Past President of ILA and Distinguished Scholar

- How Is It August Already?

- The University of Texas at Tyler’s Reading Specialist Program Receives Highest Honors From the International Literacy Association

- ILA Member Spotlight: Becky Clark

- ILA Names New Editor Team for Journal Of Adolescent & Adult Literacy

- For Network Leaders

- For Advertisers

- Privacy & Security

- Terms of Use

Quoting and integrating sources into your paper

In any study of a subject, people engage in a “conversation” of sorts, where they read or listen to others’ ideas, consider them with their own viewpoints, and then develop their own stance. It is important in this “conversation” to acknowledge when we use someone else’s words or ideas. If we didn’t come up with it ourselves, we need to tell our readers who did come up with it.

It is important to draw on the work of experts to formulate your own ideas. Quoting and paraphrasing the work of authors engaged in writing about your topic adds expert support to your argument and thesis statement. You are contributing to a scholarly conversation with scholars who are experts on your topic with your writing. This is the difference between a scholarly research paper and any other paper: you must include your own voice in your analysis and ideas alongside scholars or experts.

All your sources must relate to your thesis, or central argument, whether they are in agreement or not. It is a good idea to address all sides of the argument or thesis to make your stance stronger. There are two main ways to incorporate sources into your research paper.

Quoting is when you use the exact words from a source. You will need to put quotation marks around the words that are not your own and cite where they came from. For example:

“It wasn’t really a tune, but from the first note the beast’s eyes began to droop . . . Slowly the dog’s growls ceased – it tottered on its paws and fell to its knees, then it slumped to the ground, fast asleep” (Rowling 275).

Follow these guidelines when opting to cite a passage:

- Choose to quote passages that seem especially well phrased or are unique to the author or subject matter.

- Be selective in your quotations. Avoid over-quoting. You also don’t have to quote an entire passage. Use ellipses (. . .) to indicate omitted words. Check with your professor for their ideal length of quotations – some professors place word limits on how much of a sentence or paragraph you should quote.

- Before or after quoting a passage, include an explanation in which you interpret the significance of the quote for the reader. Avoid “hanging quotes” that have no context or introduction. It is better to err on the side of your reader not understanding your point until you spell it out for them, rather than assume readers will follow your thought process exactly.

- If you are having trouble paraphrasing (putting something into your own words), that may be a sign that you should quote it.

- Shorter quotes are generally incorporated into the flow of a sentence while longer quotes may be set off in “blocks.” Check your citation handbook for quoting guidelines.

Paraphrasing is when you state the ideas from another source in your own words . Even when you use your own words, if the ideas or facts came from another source, you need to cite where they came from. Quotation marks are not used. For example:

With the simple music of the flute, Harry lulled the dog to sleep (Rowling 275).

Follow these guidelines when opting to paraphrase a passage:

- Don’t take a passage and change a word here or there. You must write out the idea in your own words. Simply changing a few words from the original source or restating the information exactly using different words is considered plagiarism .

- Read the passage, reflect upon it, and restate it in a way that is meaningful to you within the context of your paper . You are using this to back up a point you are making, so your paraphrased content should be tailored to that point specifically.

- After reading the passage that you want to paraphrase, look away from it, and imagine explaining the main point to another person.

- After paraphrasing the passage, go back and compare it to the original. Are there any phrases that have come directly from the original source? If so, you should rephrase it or put the original in quotation marks. If you cannot state an idea in your own words, you should use the direct quotation.

A summary is similar to paraphrasing, but used in cases where you are trying to give an overview of many ideas. As in paraphrasing, quotation marks are not used, but a citation is still necessary. For example:

Through a combination of skill and their invisibility cloak, Harry, Ron, and Hermione slipped through Hogwarts to the dog’s room and down through the trapdoor within (Rowling 271-77).

Important guidelines

When integrating a source into your paper, remember to use these three important components:

- Introductory phrase to the source material : mention the author, date, or any other relevant information when introducing a quote or paraphrase.

- Source material : a direct quote, paraphrase, or summary with proper citation.

- Analysis of source material : your response, interpretations, or arguments regarding the source material should introduce or follow it. When incorporating source material into your paper, relate your source and analysis back to your original thesis.

Ideally, papers will contain a good balance of direct quotations, paraphrasing and your own thoughts. Too much reliance on quotations and paraphrasing can make it seem like you are only using the work of others and have no original thoughts on the topic.

Always properly cite an author’s original idea, whether you have directly quoted or paraphrased it. If you have questions about how to cite properly in your chosen citation style, browse these citation guides . You can also review our guide to understanding plagiarism .

University Writing Center

The University of Nevada, Reno Writing Center provides helpful guidance on quoting and paraphrasing and explains how to make sure your paraphrasing does not veer into plagiarism. If you have any questions about quoting or paraphrasing, or need help at any point in the writing process, schedule an appointment with the Writing Center.

Works Cited

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. A.A. Levine Books, 1998.

How to Use Sources in College Essays

Written by Emily Smith

When we talk about academic writing, we often refer to it as a conversation. This analogy is an easy way to think about the ways in which scholars respond to, build upon, and challenge the work of other academics through their writing.

In college, you’ll have an opportunity to participate in this dialogue, as many academic writing assignments will require that you utilize sources to support your ideas. Like any good conversationalist, it’s important to adopt the right approach when responding to others’ ideas (i.e., writing from sources) to create a dialogue that is balanced, clear, and dynamic.

How do you do that? We’ve got you covered! In this guide, we’ll show you how to utilize sources strategically so that you can support your ideas, build credibility, and craft papers that are clear and compelling.

Sources and evidence can take a variety of forms, including experiments and observations, depending on your field. For the purposes of this guide, we’ll be focusing on best practices for using academic texts in college-level papers. For more information on other forms of evidence, check out our guide on research.

Table of Contents

Before you write, organizing your sources, four ways to integrate your sources.

Paraphrasing

Summarizing

Synthesizing

Balancing Strategies

How to Assess Your Source Utilization

A strong piece of writing usually begins with thoughtful preparation. In the case of an academic writing assignment, that means understanding your assignment prompt (including your professor’s expectations about the use and citing of sources), conducting careful research to identify credible sources, and carefully reading any materials you plan to use.

That last step is especially important for our purposes: you cannot effectively or ethically use a source if you do not understand it. Admittedly, that’s probably easier said than done, as many academic texts can be downright dense due to their use of jargon and complex theoretical concepts. So how can you know if you’ve really understood what you’re reading?

The key is to read actively by taking the following steps:

SLOW DOWN. Many students try to rush through their reading due to time constraints, but just because your eyes are moving over a page doesn’t mean you’re understanding or retaining information. Check in with yourself to be sure you’re fully engaged in your reading. If you’re not focused, consider taking a break and returning to your work later, if time allows.

Annotate texts by summarizing important concepts or ideas in your notes. If you can easily articulate an idea in your own words, that is a strong indicator that you understand it.

Document your questions. In some cases those questions may help you identify which concepts you do not yet understand, and in other cases, these questions may help you generate ideas for your writing.

After you finish a text, conduct an informal debrief by asking yourself a few questions:

What was the main argument or idea of this text? Summarize it in your own words.

Do you understand all of the key concepts in the text? If not, try rereading the source and seek additional support from classmates, your TA, or your professor. If you need guidance on how to communicate with an instructor and connect with academic support services, check out this guide.

Could you teach this material to someone else? If you have a friend or classmate available, try to explain the material to them. Note what ideas you stumble over, as that can indicate where you might need to invest more time.

How does the text connect to your writing assignment? Does it support, contextualize, refute, or challenge your ideas? Which sections, quotes, or concepts are most relevant to your topic? Make note of your answers to these questions, as they can help you decide if and how to utilize a source (more on that below).

Okay, you’ve done the reading (and you understand it!). Now it’s time to start thinking strategically about the assignment at hand. Looking back over your reading, consider which sources will be most useful for your assignment and how you might like to use them. Sources can be used in a variety of ways:

As evidence to support an idea.

As an artifact to be analyzed (like in a literary analysis).

As context to provide necessary background information about a topic or idea.

To introduce a counterargument to complicate and—hopefully—strengthen an argument.

As you consider these possibilities, take note of what concepts or passages might be most useful throughout your paper, being sure to record citation information (e.g., authors, page numbers, etc.) to make it easy to cite your sources. If you have not yet found a note-taking system that works for you, consider using Steve Runge’s organizational method to keep track of your sources. For more information about how and why you should cite your sources, take a look at our guides on citations and plagiarism.

Once you’ve done the appropriate prep work, you can start writing, which means you need to decide how you want to weave sources into your paper. There are four ways to integrate a source into a draft, and the exact approach you use will depend on the purpose your source serves within your paper.

The way in which you integrate sources using the options below will depend on your assignment and rhetorical goals. As a general rule of thumb, you should strive to utilize multiple techniques and balance outside sources with your own ideas so that you can craft papers that are clear and compelling.

Option 1: Quoting

When you quote a source, you represent the original author’s words exactly . Students often default to quoting as their go-to source integration strategy because it likely seems like the easiest technique, since the writer doesn’t have to articulate an idea in their own words. However, an overabundance of quotations can lead to a few problems:

Relying too heavily on outside sources, particularly in the form of quotations, can create a paper that lacks a point of view or perspective. If your audience is reading a draft that is primarily composed of loosely connected quotations, wouldn’t it be easier for them to just read the original texts?

Papers with an overabundance of quotes can be boring! As the old adage goes, variety is the spice of life … and writing. Our eyes and ears like variety; utilizing multiple source integration strategies in conjunction with your own ideas can help you produce a draft that will grab and maintain your reader’s interest.

With that being said, there are times when quoting is the right call. Quote a text when the language of the original source is important to your paper, like in cases where you are analyzing its language (hello, literary analysis!), or when a quote might add needed emphasis or authority to a point you’re making, or in a case where it might be very difficult to paraphrase due to technical jargon.

Fundamentally, using a quote signals to your reader that that specific language is important. If your reader simply needs to know information from a source (rather than the language used to communicate that information), consider using one of the other source integration techniques discussed below.

How to Quote

We mentioned earlier that quoting can seem like the easiest option when it comes time to use a source, but there are actually a few steps you need to follow to quote a source effectively and ethically:

Select your quote. Quoted materials should generally be used sparingly, so quote as little material as possible. In many cases, you might just need to quote a particular phrase or maybe a sentence. Occasionally, you might need to quote multiple lines or utilize a block quote, which is a longer quote that is set apart from the rest of your paper’s text. Be sure to defer to your discipline’s style guide (e.g., MLA) to determine when and how to use a block quote. Generally speaking, longer quotes, particularly block quotes, should be used VERY judiciously and only in cases where their length can be justified by the content’s relevance to your paper AND by what you have to say about the quoted material (more on that in Step 3).

Introduce your quote. Once you have a quote picked out, you can’t just drop it into your paper and move on, as your reader will need to understand its context. It is unethical to misrepresent someone’s words by taking them out of context, so be sure to explain who said or wrote the quoted material, as well as where it came from. Providing this context will also help you avoid a dropped or standalone quote that is disconnected from the rest of a paper, which can be confusing for a reader. To illustrate the importance of context, here is an example (without context) from Stephen King’s On Writing : “I want you to understand that my basic belief about the making of stories is that they pretty much make themselves.” If you read this quote on its own, you might think that King is saying that good writing just … happens. However, that isn’t the case, since King makes numerous recommendations to aspiring writers in his memoir. In actuality, King is discussing his views on plot and the ways in which a writer’s fixation on plot can be detrimental to their work. So here is how a writer using this quote might introduce it to provide the necessary context to avoid misrepresenting King’s thoughts: In On Writing , King identifies practices that fiction writers can use to strengthen their work, ranging from developing their grammar proficiency to curating an appropriate workspace. However, he actively discourages writers from becoming overly concerned with plot, stating, “I want you to understand that my basic belief about the making of stories is that they pretty much make themselves” (163). King believes that plotting is counterproductive to the creative process, going so far as to suggest that the two are incompatible.

Offer explanation or analysis. Quotations (and any form of evidence for that matter) don’t speak for themselves; as a general rule, assume your reasoning for using a particular quote isn’t obvious to your reader. As a writer, you must create a bridge between your argument and a quotation by interpreting, analyzing, or discussing its content to clarify its relevance to your paper. As a rule of thumb, your explanation or analysis should also balance out your quotation, meaning it should be at least as long as the quote you selected. For example, if you use a block quote, but only have one sentence of analysis to offer about it, that might be a sign that you don’t actually need to use the entirety of that passage (see Step 1 for additional information about quote selection).

Cite your source. Any time you use content from outside sources, you must provide a citation . The exact rules and format for citing sources will vary depending on your field or discipline, so be sure to consult a style guide for specific guidance. If you’re new to the idea of citing sources, you can also review our citation guide for general information about citations’ purpose and logic.

For more guidance on quotations, including how to punctuate and modify them, check out this guide from the UNC Writing Center.

Option 2: Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you communicate the content of a specific line, passage, or idea in your own words. Paraphrasing is often used in cases where a particular excerpt of a text is important, but your reader does not need to be privy to the original author’s exact language. For example, a writer might paraphrase a section of dialogue from a novel before quoting a specific phrase that they want to analyze.

As with quoting, it is important to accurately represent paraphrased material by offering any needed context. Another consideration writers should be mindful of when paraphrasing is being careful to use their own original language and sentence structures. New academic writers sometimes think that they can paraphrase by simply switching up a few words in a quote, but that would actually be considered plagiarism— mosaic plagiarism or patchwriting to be specific. For this reason, writers must paraphrase thoughtfully to ensure they accurately represent a text’s meaning without mirroring its original language or sentence structure. One of the easiest ways to do this is to step away from the content you need to paraphrase and explain it from memory. This approach can help you generate new phrasing and avoid the temptation to borrow elements from the original. For additional guidance on paraphrasing, check out our guide on avoiding plagiarism.

Option 3: Summarizing

A summary provides a brief and, often, broad overview of a source in your own words. Summaries are frequently used to provide context or background information for a reader; for this reason, you’re likely to use summaries early in a paper where you need to orient a reader to your topic. There are a few considerations you should weigh when deciding if and how to summarize:

Summary vs. paraphrase. Summarizing and paraphrasing are similar strategies in that they both require writers to represent a source in their own words. The main way in which these techniques differ is in the scope of the content being discussed. A summary generally covers a broad topic (think the main argument of a journal article or the plotline of a book), while paraphrasing is used to represent a narrower idea, such as a snippet of dialogue or the meaning of a specific concept. Writers should consider the scope of the content they need to discuss when deciding which strategy is most appropriate

Using original language. Another commonality between summary and paraphrase is that students sometimes struggle to translate content (particularly long or complex arguments) into their own words. One strategy that can make it easier to summarize is to use simple language in a rough draft, almost as if you were talking to a friend. You might even look back at your notes and annotations from your reading for help with this step. This approach can help you produce a working summary that is clear and direct that you can then polish to remove any slang or colloquialisms that might not be appropriate for an academic writing assignment. For more information on academic writing, check out our guide on academic writing style in the United States.

Should you be analyzing instead? A common mistake among first-year college students is summarizing material when they should be writing about it analytically or argumentatively. This issue often arises while students are getting acclimated to college-level writing assignments. To avoid this pitfall, be sure to return to your assignment prompt to check whether the content and style of your paper align with your professor’s expectations. If you’re not sure whether your writing counts as summary or analysis, consider what kind of questions you are answering. Are you simply describing the who, what, and when of your topic (Ex: The plot of a book, the history of a particular event, etc.) or are you exploring the “how” and “why” of your topic? Summary tends to focus on basic descriptions or facts, which generally are not up for interpretation, while analysis usually explores more complex ideas that can be questioned.

Option 4: Synthesizing

A perhaps lesser-known form of source integration is synthesis. Similar to summary, synthesizing occurs when a writer discusses sources in tandem with one another, illustrating how those sources agree on a given idea in order to arrive at a conclusion about a topic. You can check out an example of effective and ineffective synthesis on the Purdue OWL site. Synthesis is a useful way to put sources in conversation with one another to contextualize the discourse surrounding a topic or to illustrate support for an idea. For this reason, synthesis is commonly used in literature reviews and research papers. Effective synthesis requires:

Intentional reading and organization. To figure out where sources agree, writers must first read and organize their sources. Aside from the active reading strategies discussed previously, this also involves keeping track of the areas in which sources align. One way to organize this information is to develop a synthesis matrix , which makes it easy to visualize commonalities between sources.

Use of clear transitions. Synthesis hinges on how effectively a writer can explain the relationships between sources. Using clear transitions is one of the best ways to communicate those connections. For more guidance on creating transitions, check out our literary analysis guide and this handout from the UNC Writing Center.

Careful citation. As with any kind of source integration, it’s critical that writers carefully cite material to avoid plagiarism. This step is especially important when synthesizing texts to ensure you clearly distinguish where ideas from one source end and another begin. For more guidance on citations, check out our citation guide.

How to Assess Your Source Utilization—The Color Method

Effective source utilization hinges on a balance of voices (i.e., yours as a writer and those of your sources). One of the easiest ways to gauge your source utilization is to color code your paper.

To use this strategy, select three colors. For the purposes of this example, we’ll use the stoplight method:

Red for quoted material

Yellow for summarized, paraphrased, or synthesized material

Green for your original ideas and analysis

Color code your draft according to this system. Once you are finished, analyze the balance and distribution of color in your draft. Specifically, you might consider:

Do you notice an overabundance of one color in your paper? If so, what might that indicate? For example, a lot of green (i.e., your ideas) might suggest that you need more support from your sources. An abundance of quotes might suggest that you either need to utilize alternative source integration techniques or offer more robust analysis.

Is the color distribution in individual paragraphs appropriate? You might expect a literature review paragraph, for example, to include a lot of summary and synthesis, but if you notice that a body paragraph is all one color, that might indicate that you need more support or you need to offer clearer connections between your evidence and your overarching argument.

Does the color distribution make sense for the assignment and for your discipline? Different styles and genres of writing require various approaches to source utilization. For example, a literary analysis in an English class would likely utilize a decent number of quotations, while a research paper for a sociology class would likely utilize more synthesis.

This basic method can also be adapted to better suit your needs. For example, you can assign colors to additional forms of evidence (e.g., statistics, observation, interviews, etc.) to provide a more granular perspective on your source integration.

As you’ve probably realized by now, effective source utilization can vary depending upon several factors, including your discipline, the kind of assignment you’re completing, and your rhetorical goals. However, in any context, effective source utilization has the following qualities:

Intentionality. Strong writers think critically about what sources they use and how they weave them into their papers. For each quotation, paraphrase, summary, or synthesis you use, try to justify why you are using a particular source and why you have chosen a given source integration technique. If you draw a blank, that might be a sign that you need to spend more time assessing either (a) the relevance of a source or (b) your source integration strategy.

Variety. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, varied writing tends to be stronger writing. Try to use a healthy balance of source integration techniques in conjunction with your own original ideas to create papers that are interesting and well supported.

Connection. No matter how relevant or compelling a source is, it cannot support a paper’s argument or purpose if it is not clearly woven into the draft. Be sure to carefully contextualize and, if necessary, analyze source content to connect it to a paper’s overarching argument.

Citation. Effective source integration cannot happen without clear and consistent citation. Be sure to clearly cite your sources to attribute credit where it’s due and make it possible for your reader to track down additional information about your topic.

Although it can take some practice, falling back on these basic principles will ensure you have the knowledge and skills you need to craft effective source dialogue and make a meaningful contribution to scholarly discourse in your discipline.

Special thanks to Emily Smith for writing this post and contributing to other College Writing Center resources

Emily Smith (she/her) has worked with hundreds of students to become more thoughtful, intentional, and confident writers in her work as a composition instructor, college essay specialist, and, most recently, as a writing center director. Leveraging her background in writing center work, Emily loves to collaborate with students to find ease in the writing process. When not coaching students, she can likely be found baking in pursuit of the perfect chocolate chip cookie, watching TCM, and spoiling her cat.

Top Values: Empathy | Inclusion | Balance

How to Write a Strong Argument

Evaluating Sources

College Writing Center

First-Year Writing Essentials

College-Level Writing

Unpacking Academic Writing Prompts

What Makes a Good Argument?

Evaluating Sources: A Guide for the Online Generation

What Are Citations?

Avoiding Plagiarism

US Academic Writing for College: 10 Features of Style

Applying Writing Feedback

How to Edit a College Essay

Asking for Help in College & Using Your Resources

What Is Academic Research + How To Do It

How to Write a Literature Review

Subject or Context Specific Guides

Literary Analysis–How To

How to Write A History Essay

A Sophomore or Junior’s Guide to the Senior Thesis

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

37 Using Sources in Your Writing

Teaching & Learning, University Libraries and Christina Frasier

Learning Objectives

- Identify different types of sources.

- Recognize what type of information the source has.

- Categorize available sources according to how they meet your needs.

- Books and encyclopedias

- Websites, web pages, and blogs

- Magazine, journal, and newspaper articles

- Research reports and conference papers

- Field notes and diaries

- Photographs, paintings, cartoons, and other art works

- TV and radio programs, podcasts, movies, and videos

- Illuminated manuscripts and artifacts

- Bones, minerals, and fossils

- Preserved tissues and organs

- Architectural plans and maps

- Pamphlets and government documents

- Music scores and recorded performances

- Dance notation and theater set models

With so many sources available, the question usually is not whether sources exist for your project but which ones will best meet your information needs.

Being able to categorize a source helps you understand the kind of information it contains, which is a big clue to (1) whether might meet one or more of your information needs and (2) where to look for it and similar sources.

A source can be categorized by:

- Whether it contains quantitative or qualitative information or both

- Whether the source is objective (factual) or persuasive (opinion) and may be biased

- Whether the source is a scholarly, professional or popular publication

- Whether the material is a primary, secondary or tertiary source

- What format the source is in

As you may already be able to tell, sources can be in more than one category at the same time because the categories are not mutually exclusive.

Knowing the kinds of information in each category of sources will help you choose the right kind of information to meet each of your information needs. And some of those needs are very particular.

Information needs are why you need sources. Meeting those needs is what you’re going to do with sources as you complete your research project.

Here are those needs:

- To learn more background information.

- To answer your research question(s).

- To convince your audience that your answer is correct or, at least, the most reasonable answer.

- To describe the situation surrounding your research question for your audience and explain why it’s important.

- To report what others have said about your question, including any different answers to your research question.

Sources to meet needs

Because there are several categories of sources (see Types of Sources), the options you have to meet your information needs can seem complex.

Our best advice is to pay attention to when only primary and secondary sources are required to meet a need and to when only professional and scholarly sources will work. If your research project is in the arts, also pay attention to when you must use popular sources, because popular sources are often primary sources in the arts.

These descriptions and summaries of when to use what kind of source should help.

1. To Learn Background Information

When you first get a research assignment and perhaps for a considerable time afterward, you will almost always have to learn some background information as you develop your research question and explore how to answer it.

Sources from any category and from any subgroup within a category – except journal articles – can meet students’ need to learn background information and understand a variety of perspectives. Journal articles, are usually too specific to be background. From easy-to-understand to more complex sources, read and/or view those that advance your knowledge and understanding.

For instance, especially while you are getting started, secondary sources that synthesize an event or work of art and tertiary sources such as guidebooks can be a big help. Wikipedia is a good tertiary source of background information.

Sources you use for background information don’t have to be sources that you cite in your final report, although some may be.

Sources to Learn Background Information

- Quantitative or Qualitative: Either—whatever advances your knowledge.

- Fact or Opinion: Any—whatever advances your knowledge.

- Scholarly, Professional, or Popular: Any—whatever advances your knowledge–at this stage, Wikipedia or other general, online references work well.

- Primary, Secondary, or Tertiary: Any—whatever advances your knowledge.

- Publication Format: Any—whatever advances your knowledge.

One important reason for finding background information is to learn the language that professionals and scholars have used when writing about your research question. That language will help you later, particularly when you’re searching for sources to answer your research question.

To identify that language, you can always type the word glossary and then the discipline for which you’re doing your assignment in the search engine search box.

Here are two examples to try:

- Glossary neuroscience

- Glossary “social media marketing”

(Putting a phrase in quotes in most search boxes insures that the phrase will be searched rather than individual words.)

2. To Answer Your Research Question

You have to be much pickier with sources to meet this need because only certain choices can do the job. Whether you can use quantitative or qualitative data depends on what your research question itself calls for.

Only primary and secondary sources (from the category called publication mode) can be used to answer your research question and, in addition, those need to be professional and/or scholarly sources for most disciplines (humanities, social sciences, and sciences). But the arts often require popular sources as primary or secondary sources to answer research questions. Also, the author’s purpose for most disciplines should be to educate and inform or, for the arts, to entertain and perhaps even to sell. (As you may remember, primary sources are those created at the same time as an event you are researching or that offer something original, such as an original performance or a journal article reporting original research. Secondary sources analyze or otherwise react to secondary sources. Because of the information lifecycle, the latest secondary sources are often the best because their creators have had time for better analysis and more information to incorporate.)

- Qualitative or quantitative data Suppose your research question is “How did a a particular king of Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah, work to modernize his country?”That question may lend itself to qualitative descriptive judgments—about what are considered the components of modernization, including, for instance, what were his thoughts about the place of women in society. But it may also be helped by some quantitative data, such as those that would let you compare the numbers of women attending higher education when Abdullah became king and those attending at the time of his death or, for instance, whether manufacturing increased while he reigned.

From the example, we see that looking for sources providing both quantitative and qualitative information (not necessarily in the same resource) is usually a good idea.

If it is not clear to you from the formats of sources you are assigned to read for your course, ask your professor which formats are acceptable to your discipline for answering your research question.

Sources to Answer Your Research Question

- Quantitative or Qualitative: Will be determined by the question itself.

- Fact or Opinion: Professional and scholarly for most disciplines; the arts often use popular, as well.

- Scholarly, Professional, or Popular: Professional and scholarly for most disciplines; the arts often use popular, as well.

- Primary, Secondary, or Tertiary: Primary and secondary.

- Publication Format: Those acceptable to your discipline.

3. To Convince Your Audience

Convincing your audience is similar to convincing yourself and takes the same kinds of sources—as long as your audience is made up of people like you and your professor, which is often true in academic writing. That means using many of those sources you used to answer your research question.

When your audience isn’t very much like you and your professor, you can adjust your choice of sources to meet this need. Perhaps you will include more that are secondary sources rather than primary, some that are popular or professional rather than scholarly, and some whose author intent may not be to educate and inform.

Sources to Convince Your Audience

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: Same as what you used to answer your research question if your audience is like you and your professor. (If you have a different audience, use what is convincing to them.)

- Fact or Opinion: Those with the purpose(s) you used to answer your research question if your audience is like you and your professor. (If you have a different audience, you may be better off including some sources intended to entertain or sell.)

- Scholarly, Professional or Popular: Those with the same expertise level as you used to answer the question if your audience is like you and your professor. (If you have a different audience, you may be better off including some popular.)

- Publication Mode: Primary and secondary sources if your audience is like you and your professor. If you have a different audience, you may be better off including more secondary sources than primary.

- Publication Format: Those acceptable to your discipline, if your audience is like you and your professor.

4. To Describe the Situation

Choosing what kinds of sources you’ll need to meet this need is pretty simple—you should almost always use what’s going to be clear and compelling to your audience. Nonetheless, sources intended to educate and inform may play an out-sized role here.

But even then, they don’t always have to educate and inform formally , which opens the door to using sources such as fiction or the other arts and formats that you might not use with some other information needs.

Sources to Describe the Situation

- Quantitative or Qualitative: Whatever you think will make the description most clear and compelling and your question important to your audience.

- Fact or Opinion: Often to educate and inform, but sources don’t have to do that formally here, so they can also be to entertain or sell.

- Scholarly, Professional, or Popular: Whatever you think will make the description most clear and compelling and your question important to your audience.

- Primary, Secondary or Tertiary: Whatever you think will make the description most clear and compelling and your question important to your audience. Some disciplines will not accept tertiary for this need.

- Publication Format: Whatever you think will make the description most clear and compelling and your question important to your audience. Some discipline will accept only particular formats, so check for your discipline.

5. To Report What Others Have Said

The choices here about kinds of sources are easy: just use the same or similar sources that you used to answer your research question that you also think will be the most convincing to your audience.

Sources to Report What Others Have Said

- Quantitative or Qualitative: Those sources that you used to answer your research question that you think will be most convincing to your audience.

- Fact or Opinion: Those sources that you used to answer your research question that you think will be most convincing to your audience.

- Scholarly, Professional, or Popular: Those sources that you used to answer your research question that you think will be most convincing to your audience.

- Primary, Secondary, or Tertiary: Those sources that you used to answer your research question that you think will be most convincing to your audience.

- Publication Format: Those sources that you used to answer your research question that you think will be most convincing to your audience.

Adapted from English Composition: Connect, Collaborate, Communicate by Ann Inoshita; Karyl Garland; Kate Sims; Jeanne K. Tsutsui Keuma; and Tasha Williams, CC BY 4.0

Using Sources in Your Writing Copyright © by Teaching & Learning, University Libraries and Christina Frasier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Integrating Sources

Once you have evaluated your source materials, you should select your sources and decide how to include them in your work. You can quote directly, paraphrase passages, or simply summarize the main points— and you can use all of these techniques in a single document. It’s important to learn how to quote, when to quote, and when not to quote so that you can utilize examples most effectively. Outside sources can be incredibly supportive in your writing if you know how to incorporate them effectively.

Choosing Sources to Establish Credibility

The main reason writers include sources in their work is to establish credibility with their audience. Credibility is the level of trustworthiness and authority that a reader perceives a writer has on a subject and is one of the key characteristics of effective writing, especially argumentative writing.

Without credibility, a writer's ideas are easily dismissed. Including sources in your writing indicates that your opinions are based on more than a personal or surface knowledge of the subject. It shows that others find your ideas worthy of consideration, that experts in the field corroborate your reasoning, and that there is hard evidence to support your opinion. “Peer Reviewed” sources are generally considered the most credible.

To Show Your Knowledge of the Subject

Writing that "shoots from the hip," without citing sources, is fine for many purposes. It works for an Op-Ed piece, for instance, but not for academic writing.

Without establishing that they have researched and studied their subject, writers can and do appear intelligent and witty, however, the question arises: how much do they really know about their topic?

Citing and documenting source material in your work shows your reader how knowledgeable you are regarding the facts and background of your subject. Your reader will know that you've put time and effort into making sure you "know whereof you speak."

Aligning Yourself with Experts

When establishing credibility with a jury, attorneys often call witnesses to the stand who have expertise in a given field. The "expert witness" provides opinions and presents facts regarding the technical aspects of a case. This is done because the attorney does not have the professional credentials of the witness. By borrowing the credentials of the "expert" the attorney is better able to argue his or her case.

For instance, a brain surgeon has the medical expertise to explain whether, why, or how a certain type of brain injury leads to memory loss. The attorney does not and banks on the jury trusting the "expert testimony" of the surgeon.

As a student, you are often put into this same position. You will be writing about unfamiliar subjects; topics in which you have little or no expertise. By including source material in your writing you, too, are calling upon "expert witnesses."

Researching outside sources helps you find statements from authorities on the subject that you then can quote or paraphrase within your paper. The ideas you express then become not just yours, but those of men and women who have studied and worked in your field of study for years. In effect, you make your case by "borrowing" the knowledge of experts and including it in your paper.

To Show Agreement

One person declaring something to be true can be easily ignored or dismissed. After all, it is only one person's opinion. It may or may not be true. When several people agree that something is true, however, it is not so easy to dismiss.

By including source material in your writing, you tell your reader, in effect, that there is a "chorus" of agreement on your ideas.

That said, be aware that a "chorus" of agreement does not necessarily mean that the "chorus" is right. Citing and documenting the "chorus" simply bolsters the credibility of your argument and gives others the opportunity to research your findings further and come to their own conclusions.

It also indicates that you have done your homework on the subject and that what you have to say can be trusted at least to the extent of your research efforts.

To Introduce Factual Evidence

Because factual information (such as the date a war started) and statistics can be independently verified by your readers through their own research or experimentation, this type of evidence is often the most credible form of support you can offer for your ideas.

As a student, you usually might not have the time to conduct first-hand surveys or experiments of your own to generate this kind of evidence. Instead, you might call on the research conducted by others to bring in factual evidence to back up your ideas (giving full credit to the source of the evidence, of course).

Methods for Synthesizing Sources

After choosing your sources and establishing what you want to do with them, you should synthesize those sources to relate them to your own writing purpose. There are a few different methods you can use to synthesize sources. To synthesize sources is to combine different scholarly works to produce a nuanced understanding or insight. Two of the most common strategies for synthesizing sources are ‘Explanatory Synthesis’ and ‘Argumentative Synthesis’-- they each do different work and should be employed in different writing situations.

Explanatory Synthesis

An explanatory synthesis is generally more factual and not inclusive of writer opinion. In informative or explanatory writing you are bringing related information together, explaining that relatedness, and relaying the implications. When synthesizing explanatory sources, you are using established knowledge from researchers to reach some sort of conclusion. Again, you should stay neutral in an explanatory synthesis and not take one position or another on the topic.

Argumentative Synthesis

An argumentative synthesis is oriented around an opinion or argument, which is explained by the writer. You are bringing together multiple sources and showing how they relate to your argument, either supporting it or disagreeing with it. By combining different sources related to your argument, you can form a new ‘take’ that directly references established research. The analytical comments you provide on those sources should make your stance on the issue clear to the audience.

Quoting Source Material

There are many reasons for quoting source material, a primary one being that captured in the expression: "getting it straight from the horse's mouth."

Quoting authoritative voices in your field lends credence to the arguments you present. By association, your words and those you quote are drawn closer together, creating powerful perceptions for you readers regarding the veracity and validity of your work.

It's especially important in academic writing that original sources be quoted accurately and correctly and that they be cited immediately following their appearance in the text.

Quoting Directly

Quoting Directly means taking a specific statement or passage made directly by an author and including it, word for word, in your work. The words you quote are original to the author you are quoting and are not taken from any other source.

You may not rephrase the statement or passage; simply copy it into your document exactly as you found it, punctuating it with an open quotation mark placed directly before the first word and a closing quotation mark placed directly after the last word.

Example of Quoting Directly

Original Passage:

This first juxtaposition sets up a tension between black reality and the white ideal. The question that arises is how this disparity came about. Readers--particularly white readers as we most closely match that ideal--must ask themselves: "Who or what is, after all, responsible for the soil that is bad for certain kinds of flowers, for seeds it will not nurture, for fruit it will not bear?" (Napieralski 61)

--from Brenda Edmands, "The Gaze That Condemns: White Readers, Othering And Division in Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye" (Unpublished Essay)

Edmonds material quoted directly in the following passage:

It is clear that Toni Morrison is using the excerpt from the classic children's novels, Dick and Jane, for the purpose of establishing a conflict between "the norm"-in this case the white culture-and "the other"-black culture. By following the Dick and Jane excerpt so closely with the short prologue describing Pecola's pregnancy by her father and her subsequent shunning by the townspeople, Morrison "sets up a tension between black reality and the white ideal" (Edmands).

Note how the source citation is documented within the sentence in which the quote appears.

Quoting Previously Quoted Material

Quoting previously quoted material means taking a specific statement or passage that the author of your source material has already taken (directly quoted) from another source, and inserting it into your work.

The rules remain the same as when quoting directly; you may not rephrase the statement or passage, but copy it exactly as it was written, placing the quotation marks in exactly the same manner. You must document previously quoted material differently, however, than other types of quotations.

Example of Quoting Previously Quoted Material

The Original Source Material says:

The question that arises is how this disparity came about. Readers--particularly white readers as we most closely match that ideal--must ask themselves: "Who or what is, after all, responsible for the soil that is bad for certain kinds of flowers, for seeds it will not nurture, for fruit it will not bear?" (Napieralski 61)

Napieralski's statement, previously quoted by Edmonds, quoted in the following passage:

In Morrison's novel, The Bluest Eye, the overriding question is about responsibility according to Professor Edmund A. Napieralski: "Who or what is, after all, responsible for the soil that is bad for certain kinds of flowers, for seeds it will not nurture, for fruit it will not bear?" (qtd. in Edmands)

Note how the citation here tells the reader that this quotation was previously quoted in the source by Edmands and how it appears outside of the sentence in which the quote appears.

Using a Quotation within a Quotation

Using a quotation within a quotation means taking a passage from your source material that is a combination of the author's own words and a passage that he or she has quoted from yet another source, and inserting that into your own work.

While you document these types of quotations in the same manner as direct quotations, you use slightly different punctuation to indicate where the author's own words leave off, and the quoted passage begins.

Example of Using a Quotation within a Quotation

This first juxtaposition sets up a tension between black reality and the white ideal. The question that arises is how this disparity came about. Readers-particularly white readers as we most closely match that ideal-must ask themselves: "Who or what is, after all, responsible for the soil that is bad for certain kinds of flowers, for seeds it will not nurture, for fruit it will not bear?" (Napieralski 61)

Edmands' introductory material, including the previously quoted Napieralski statement, quoted in the following passage:

Many scholars feel there is a need for white readers to wrestle with questions of race in Morrison's The Bluest Eye in a fashion different from readers of other races. Brenda Edmands, a lecturer in the English Department at Colorado State University, argues that white readers must consider questions of racial disparity in the novel more closely. According to Ms. Edmands: "Readers-particularly white readers as we most closely match that ideal-must ask themselves: 'Who or what is, after all, responsible for the soil that is bad for certain kinds of flowers, for seeds it will not nurture, for fruit it will not bear?' (Napieralski 61)" ("The Gaze That Condemns").

Note how the material quoted from Napieralski is enclosed by single quotation marks while the entire passage taken from the Edmands essay, including the Napieralski quote, is enclosed in double quotation marks. As with a direct quotation, the relevant documentation is cited within the sentence in which it appears.

Using Block Quotations

A lengthy quotation—one exceeding three lines of text—is often set off as a"block quotation," or independent passage indented on the left margin. Typically, they appear immediately following the paragraph introducing the quotation.

The general rule is to end the last sentence of the paragraph preceding the block quotation with a colon, then drop down a line in your text—as if beginning a new paragraph—before inserting the quoted material. One inch (about 10 spaces) is the standard.

Be sure to cite the source of your quotation properly: for more on that, please refer to the style rules of the documentation system (MLA, APA, Chicago Manual of Style, etc.) your academic discipline requires.

Note: Unlike other quotations, block quotations do not require the use of quotation marks. Blocking and indenting the text, as well as introducing the quotation in the preceding paragraph, sufficiently notifies the reader of its status.

Example of Block Quoting

In the article "Dispositions for Good Teaching," Gary R. Howard concludes:

Having said this, it remains true that all American citizens have a constitutionally guaranteed First Amendment right to remain imprisoned in their own conditioned narrowness and cultural isolation. This luxury of ignorance, however, is not available to us as teachers. Ours is a higher calling, and for the sake of our students and the future of their world, we are required to grow toward a more adaptive set of human qualities, which would include the dispositions for difference, dialogue, disillusionment, and democracy. These are the capacities that will make it possible for us to thrive together as a species. These are the personal and professional dispositions that render us worthy to teach. (para. 28)

Howard, G. R. (2007). Dispositions for Good Teaching. Journal of Educational Controversy . Retrieved Oct 25, 2007, from http://www.wce.wwu.edu/Resources/CEP/eJournal/v002n002/a009.shtml

When to Quote

Source material should be quoted when it enhances the focus of your document and maximizes the impact of the message you are trying to convey. When it does not, it's best to use your own words. In other words, you should only really quote if some kind of efficacy will be lost by not quoting.

Quoting a Well Known Person

Quoting a well known person helps catch the attention of your reader. A trait of human nature is that people often listen more carefully when a widely recognized authority speaks. When you include statements from such people, quote them directly, rather than paraphrasing or summarizing. Doing so preserves the accuracy of the author's original words.

Quoting Unique or Striking Material

Quoting unique or striking material preserves the freshness, power and beauty of the author's original words. Paraphrasing or summarizing this kind of material will diminish the inherent strength that attracted you to them in the first place.

Direct quotations allow you to "borrow" the writing tone and style of a recognized author. This will enhance your own writing, without plagiarizing, and make it more appealing to your reader while successfully conveying your own ideas.

Example of Unique or Striking Material

When you can "hear" an individual's spoken voice in a written passage or, when the writing is particularly beautiful or unique, quote it directly. The stylistic flair in the following passage, for instance, would be hard to duplicate if not quoted directly.

We've seen a huge rise in the number of fatal Human-Mountain Lion encounters during the past decade (Smith 21). With humans increasingly moving into the lion's natural territory, is it any wonder that these tragedies are occurring? These kinds of attacks must be laid squarely at the pedicured feet of the yuppie mountain dwellers who build million-dollar homes in the foothills, right smack in the middle of the mountain lion's usual hunting ground, and then wonder why their poodle Fifi becomes lion chow or why, when they go to put their garbage out, they find themselves staring into a lion's unblinking golden gaze.

Rephrasing "right smack in the middle" and "lion chow" with "directly in the path of" and "lion food", would diminish the spoken quality and sarcastic tone of the original wording; a "lion's unblinking golden gaze" would lose a great deal of beauty and rhythm if converted to "the lion's staring yellow eyes".

Quoting Controversial Material

Quoting controversial material puts distance between you and the quoted source. This is especially important when readers might react negatively toward information or opinions that contain startling, questionable or overly biased statements and statistics.

Example of Controversial Material

This paragraph contains controversial material. It is blunt, sarcastic and highly opinionated. It is best to quote statements of this nature directly, as they exhibit an overly biased position.

We've seen a huge rise in the number of fatal Human-Mountain Lion encounters during the past decade (Smith 21). With humans increasingly moving into the lion's natural territory, is it any wonder that these tragedies are occurring? These kinds of attacks must be laid squarely at the carefully pedicured feet of the yuppie mountain dwellers who build million-dollar homes in the foothills, right smack in the middle of the mountain lion's usual hunting ground, and then wonder why their poodle Fifi becomes lion chow or why, when they go to put their garbage out, they find themselves staring into a lion's unblinking golden gaze.

By directly quoting this material, you will avoid leaving the impression that the thoughts conveyed in the passage are yours. A quotation clearly indicates that you are not the author.

When Not to Quote

Source material should be quoted when it enhances the focus of your document and maximizes the impact of the message you are trying to convey. When it does not, it's best to use your own words.

In an argumentative piece, it’s especially important to ensure that your own voice is present and at the forefront at all times.

Overusing Quotations

Overusing quotations may leave the impression that you are simply cutting and pasting the words and opinions of other people into your document rather than expressing your own ideas. It may lead a reader to question your originality and understanding of the material you are quoting.

Example of Overusing Quotations

In the following paragraph, a series of quotations about smoking have been cut and pasted together. Each quote has a specific focus, ranging from medical dangers to lingering bad odors, and yet, none build up to or explain their relevance.

Smoking should be banned from restaurants. "The regulation is long overdue" (Jones 12). "We need to ban smoking to help prevent diseases such as cancer, asthma, and bronchitis" (Smith 45). According to one restaurant customer: "I find someone smoking next to me really destroys my meal. I can't taste it anymore" (qtd. in Smith 45). "Too many restaurant owners ignore how dangerous second hand smoke is. They don't take steps voluntarily to make sure their nonsmoking customers aren't exposed, so we need to force the issue through regulations" (Jones 21). "Smoking makes my hair and clothes smell. I always have to take a shower after I've been out to eat in a restaurant that allows smoking" (Andrews 5).

As it stands, the paragraph is no more than a list of random complaints serving no clear purpose. The quotes could easily be paraphrased and placed in a bulleted list entitled "Reasons Why Smoking Should be Banned from Restaurants".

Not only does the paragraph lack purpose as a result of overusing quotes, the author’s voice isn’t present either. It’s completely overshadowed by other people’s words. Each quote should be introduced, and the purpose of its inclusion should be made clear in the author’s own words.

Unmemorable Material

Unmemorable material contains widely accepted statements of fact that are unlikely to generate debate (i.e. "Smoking causes cancer"). There is nothing to be gained by quoting this kind of statement. Source material containing a generally neutral tone or stated without some sort of stylistic flourish that strengthens your own thoughts and ideas can just as easily be paraphrased or summarized.

Example of Unmemorable Material

There is nothing particularly memorable, stylish, or controversial in the highlighted sentence below. Since it can be rephrased without losing any meaning, quoting makes little sense.

Immediately upon opening Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye we are confronted with the idea of othering and, in particular, that this othering is a result of establishing the white culture as the norm. The novel begins with a section from a classic children's book that paints an idealized picture of a family. We assume the family being described is white both because we are familiar with the book being excerpted and because of the era in which it was written.

--from Brenda Edmands, "The Gaze That Condemns: White Readers, Othering And Division in Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye"

Irrelevant Material

Irrelevant Material contains information or opinions that have little to do with the point you are trying to make. Briefly summarizing this kind of material rather than quoting it will help keep your writing focused on a specific idea. In addition, your reader will not get the idea that quotations have been included as filler rather than as meaningful and useful information. Using a quote without reason can derail the focus of a paper and therefore confuse the reader.

Example of Irrelevant Material

In the passage below, the writer discusses how the Pulitzer Prize winning author Toni Morrison uses children's literature in her own writing. For an essay arguing that adult novelists frequently use children's literature in their works, quoting the passage might support the argument.

Including all, or even part of it, may leave your reader wondering who Pecola is, however, and why the details of her pregnancy are relevant to your focus.

Toni Morrison's novel begins with a section from a classic children's book that paints an idealized picture of a family. We assume the family being described is white both because we are familiar with the book being excerpted and because of the era in which it was written. Mother, father, sister, brother, cat and dog all live in harmony in a white and green house. Contrasted with this portrait on the very next page is an image of utterly frightening disharmony in a family--Pecola's father has gotten her pregnant--and of two sisters in disagreement over seeds being planted in black dirt. This first juxtaposition sets up a tension between black reality and white ideal. --from Brenda Edmands, "The Gaze That Condemns: White Readers, Othering And Division in Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye"

The particular point Morrison makes when quoting The Bluest Eye has nothing to with an essay on novelists citing children's literature. It would be better to simply summarize the idea that Morrison quotes a child's book to set up tension and introduce her major themes, rather than quote the entire passage.

Overly Wordy Material

Overly Wordy Material should not be quoted. When you can restate the same information or the general idea in a more succinct fashion, do so. While it is tempting to include original wording to help increase the length of your essay, don’t do it. Similar to Irrelevant Material, Overly Wordy Material confuses the reader and makes your overall focus less clear.

Readers can spot this kind of filler easily and will cause them to question your integrity. Are you trying to present your points clearly and convincingly, or are you simply trying to fill up pages?

Example of Overly Wordy Material

Each sentence in the sample paragraph below says essentially the same thing, though in a slightly different manner. Together, they are a tangle of unnecessary, confusing and repetitive subordinate clauses. It would be better and more efficient to summarize what Bowers is saying, rather than quote the whole passage.

Teachers from all levels of the education process, from kindergarten to graduate schools, need to take immediate steps to ensure that all students leave school fully prepared to be contributing members of society. We must make certain that they graduate ready to give back to their communities, not just to take from them; that they walk out the doors of our institutions not just thinking about how to make a buck, but how to make a difference. Students must be taught to be civic minded, to think in terms not only of what will benefit them individually, but also in terms of what will benefit society as a whole. We have to teach them not to be selfish isolationists, but generous, willing contributors to our communities. --from Angela Bowers, "Our Responsibility to the Community" *

*This is a fictional source created solely for the purpose of providing an example.

Sample Summary:

Angela Bowers, a professor of human development, feels that one of our duties as educators is to teach civic responsibility to our students. ("Our Responsibility" 21)

Note how this cuts to the chase of the main point of the source material, neither leaving out crucial points, nor repeating any statements included in the original passage.

Editing Quotations

In order to clarify vague references, avoid irrelevant details or blend a quoted passage smoothly into the surrounding text. You may also need to edit the quotations you use.

Omitting Words and Phrases

At times, you may wish to quote only parts of a passage, omitting words and phrases to avoid irrelevant details or combine it smoothly with the sentences in which it is framed. You may do so at the beginning, middle or end of the quoted material, but remember, your reader must be informed of the omission.