- Insights blog

How to write and structure a journal article

Sharing your research data can be hugely beneficial to your career , as well as to the scholarly community and wider society. But before you do so, there are some important ethical considerations to remember.

What are the rules and guidance you should follow, when you begin to think about how to write and structure a journal article? Ruth First Prize winner Steven Rogers, PhD said the first thing is to be passionate about what you write.

Steven Nabieu Rogers, Ruth First Prize winner.

Let’s go through some of the best advice that will help you pinpoint the features of a journal article, and how to structure it into a compelling research paper.

Planning for your article

When planning to write your article, make sure it has a central message that you want to get across. This could be a novel aspect of methodology that you have in your PhD study, a new theory, or an interesting modification you have made to theory or a novel set of findings.

2018 NARST Award winner Marissa Rollnick advised that you should decide what this central focus is, then create a paper outline bearing in mind the need to:

Isolate a manageable size

Create a coherent story/argument

Make the argument self-standing

Target the journal readership

Change the writing conventions from that used in your thesis

Get familiar with the journal you want to submit to

It is a good idea to choose your target journal before you start to write your paper. Then you can tailor your writing to the journal’s requirements and readership, to increase your chances of acceptance.

When selecting your journal think about audience, purposes, what to write about and why. Decide the kind of article to write. Is it a report, position paper, critique or review? What makes your argument or research interesting? How might the paper add value to the field?

If you need more guidance on how to choose a journal, here is our guide to narrow your focus.

Once you’ve chosen your target journal, take the time to read a selection of articles already published – particularly focus on those that are relevant to your own research.

This can help you get an understanding of what the editors may be looking for, then you can guide your writing efforts.

The Think. Check. Submit. initiative provides tools to help you evaluate whether the journal you’re planning to send your work to is trustworthy.

The journal’s aims and scope is also an important resource to refer back to as you write your paper – use it to make sure your article aligns with what the journal is trying to accomplish.

Keep your message focused

The next thing you need to consider when writing your article is your target audience. Are you writing for a more general audience or is your audience experts in the same field as you? The journal you have chosen will give you more information on the type of audience that will read your work.

When you know your audience, focus on your main message to keep the attention of your readers. A lack of focus is a common problem and can get in the way of effective communication.

Stick to the point. The strongest journal articles usually have one point to make. They make that point powerfully, back it up with evidence, and position it within the field.

How to format and structure a journal article

The format and structure of a journal article is just as important as the content itself, it helps to clearly guide the reader through.

How do I format a journal article?

Individual journals will have their own specific formatting requirements, which you can find in the instructions for authors.

You can save time on formatting by downloading a template from our library of templates to apply to your article text. These templates are accepted by many of our journals. Also, a large number of our journals now offer format-free submission, which allows you to submit your paper without formatting your manuscript to meet that journal’s specific requirements.

General structure for writing an academic journal article

The title of your article is one of the first indicators readers will get of your research and concepts. It should be concise, accurate, and informative. You should include your most relevant keywords in your title, but avoid including abbreviations and formulae.

Keywords are an essential part of producing a journal article. When writing a journal article you must select keywords that you would like your article to rank for.

Keywords help potential readers to discover your article when conducting research using search engines.

The purpose of your abstract is to express the key points of your research, clearly and concisely. An abstract must always be well considered, as it is the primary element of your work that readers will come across.

An abstract should be a short paragraph (around 300 words) that summarizes the findings of your journal article. Ordinarily an abstract will be comprised of:

What your research is about

What methods have been used

What your main findings are

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements can appear to be a small aspect of your journal article, however it is still important. This is where you acknowledge the individuals who do not qualify for co-authorship, but contributed to your article intellectually, financially, or in some other manner.

When you acknowledge someone in your academic texts, it gives you more integrity as a writer as it shows that you are not claiming other academic’s ideas as your own intellectual property. It can also aid your readers in their own research journeys.

Introduction

An introduction is a pivotal part of the article writing process. An introduction not only introduces your topic and your stance on the topic, but it also (situates/contextualizes) your argument in the broader academic field.

The main body is where your main arguments and your evidence are located. Each paragraph will encapsulate a different notion and there will be clear linking between each paragraph.

Your conclusion should be an interpretation of your results, where you summarize all of the concepts that you introduced in the main body of the text in order of most to least important. No new concepts are to be introduced in this section.

References and citations

References and citations should be well balanced, current and relevant. Although every field is different, you should aim to cite references that are not more than 10 years old if possible. The studies you cite should be strongly related to your research question.

Clarity is key

Make your writing accessible by using clear language. Writing that is easy to read, is easier to understand too.

You may want to write for a global audience – to have your research reach the widest readership. Make sure you write in a way that will be understood by any reader regardless of their field or whether English is their first language.

Write your journal article with confidence, to give your reader certainty in your research. Make sure that you’ve described your methodology and approach; whilst it may seem obvious to you, it may not to your reader. And don’t forget to explain acronyms when they first appear.

Engage your audience. Go back to thinking about your audience; are they experts in your field who will easily follow technical language, or are they a lay audience who need the ideas presented in a simpler way?

Be aware of other literature in your field, and reference it

Make sure to tell your reader how your article relates to key work that’s already published. This doesn’t mean you have to review every piece of previous relevant literature, but show how you are building on previous work to avoid accidental plagiarism.

When you reference something, fully understand its relevance to your research so you can make it clear for your reader. Keep in mind that recent references highlight awareness of all the current developments in the literature that you are building on. This doesn’t mean you can’t include older references, just make sure it is clear why you’ve chosen to.

How old can my references be?

Your literature review should take into consideration the current state of the literature.

There is no specific timeline to consider. But note that your subject area may be a factor. Your colleagues may also be able to guide your decision.

Researcher’s view

Grasian Mkodzongi, Ruth First Prize Winner

Top tips to get you started

Communicate your unique point of view to stand out. You may be building on a concept already in existence, but you still need to have something new to say. Make sure you say it convincingly, and fully understand and reference what has gone before.

Editor’s view

Professor Len Barton, Founding Editor of Disability and Society

Be original

Now you know the features of a journal article and how to construct it. This video is an extra resource to use with this guide to help you know what to think about before you write your journal article.

Expert help for your manuscript

Taylor & Francis Editing Services offers a full range of pre-submission manuscript preparation services to help you improve the quality of your manuscript and submit with confidence.

Related resources

How to write your title and abstract

Journal manuscript layout guide

Improve the quality of English of your article

How to edit your paper

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- APA format for academic papers and essays

APA Formatting and Citation (7th Ed.) | Generator, Template, Examples

Published on November 6, 2020 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on January 17, 2024.

The 7th edition of the APA Publication Manual provides guidelines for clear communication , citing sources , and formatting documents. This article focuses on paper formatting.

Generate accurate APA citations with Scribbr

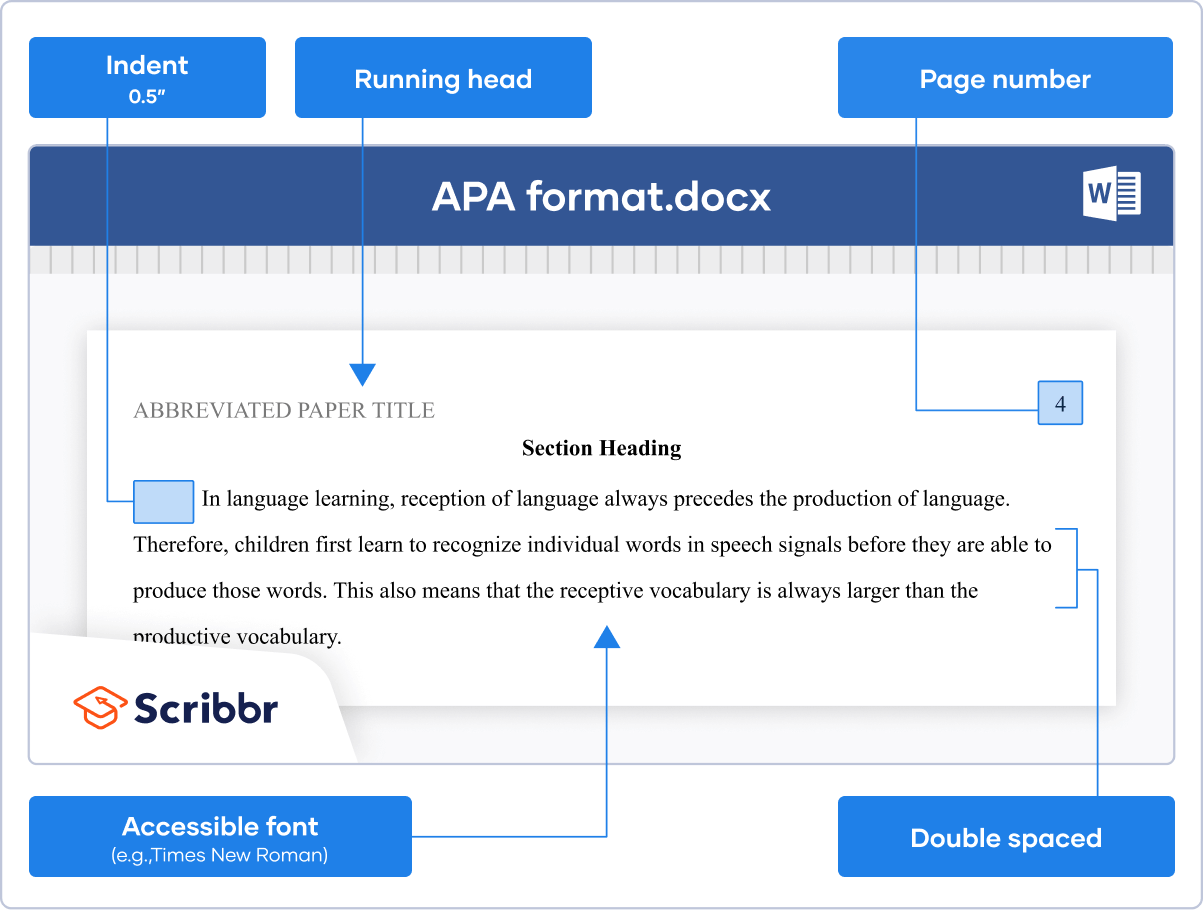

Throughout your paper, you need to apply the following APA format guidelines:

- Set page margins to 1 inch on all sides.

- Double-space all text, including headings.

- Indent the first line of every paragraph 0.5 inches.

- Use an accessible font (e.g., Times New Roman 12pt., Arial 11pt., or Georgia 11pt.).

- Include a page number on every page.

Let an expert format your paper

Our APA formatting experts can help you to format your paper according to APA guidelines. They can help you with:

- Margins, line spacing, and indentation

- Font and headings

- Running head and page numbering

Table of contents

How to set up apa format (with template), apa alphabetization guidelines, apa format template [free download], page header, headings and subheadings, reference page, tables and figures, frequently asked questions about apa format.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

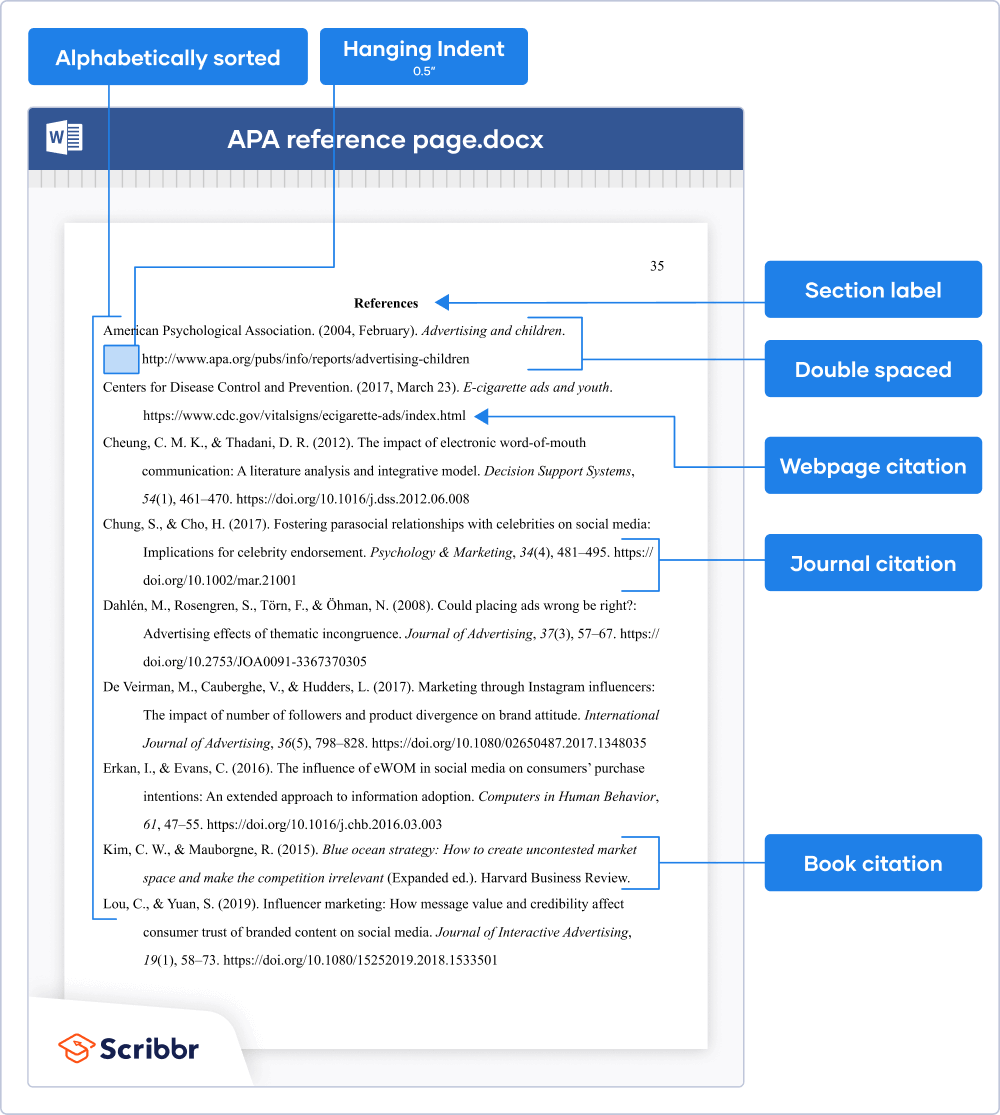

References are ordered alphabetically by the first author’s last name. If the author is unknown, order the reference entry by the first meaningful word of the title (ignoring articles: “the”, “a”, or “an”).

Why set up APA format from scratch if you can download Scribbr’s template for free?

Student papers and professional papers have slightly different guidelines regarding the title page, abstract, and running head. Our template is available in Word and Google Docs format for both versions.

- Student paper: Word | Google Docs

- Professional paper: Word | Google Docs

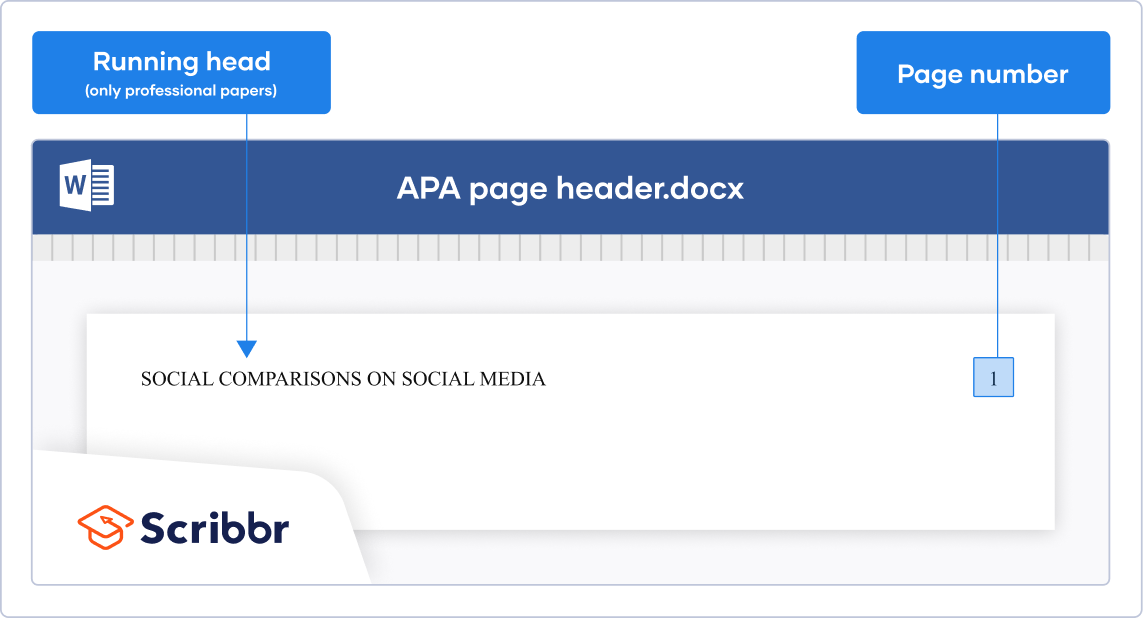

In an APA Style paper, every page has a page header. For student papers, the page header usually consists of just a page number in the page’s top-right corner. For professional papers intended for publication, it also includes a running head .

A running head is simply the paper’s title in all capital letters. It is left-aligned and can be up to 50 characters in length. Longer titles are abbreviated .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

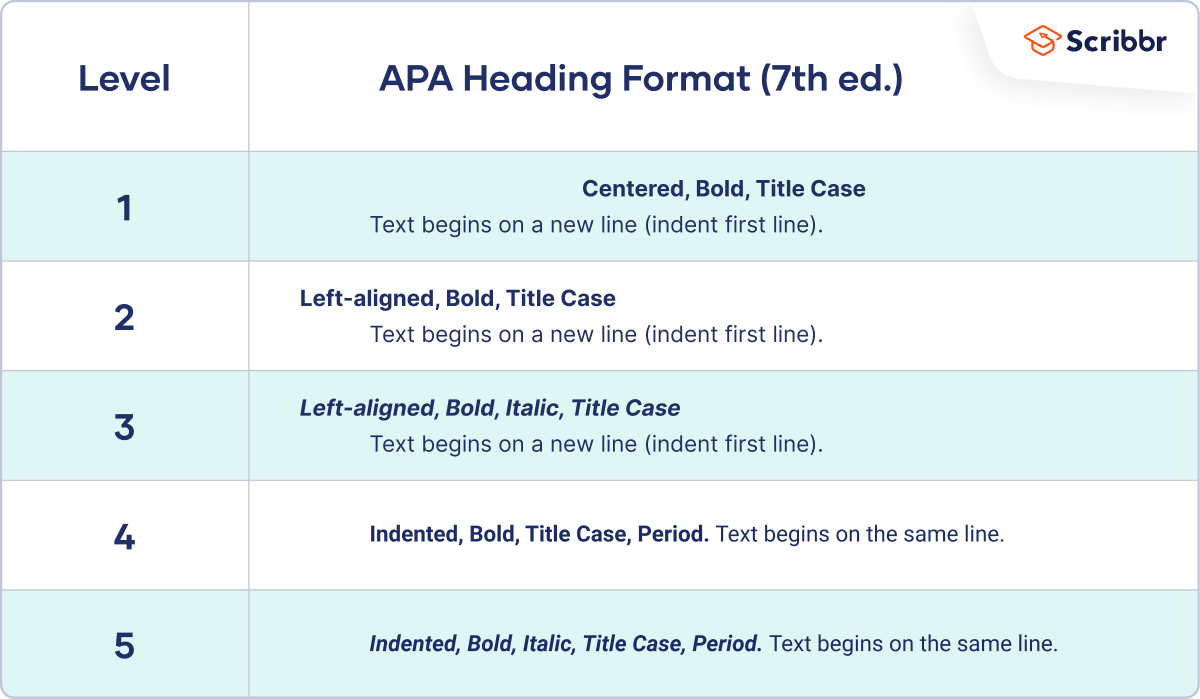

APA headings have five possible levels. Heading level 1 is used for main sections such as “ Methods ” or “ Results ”. Heading levels 2 to 5 are used for subheadings. Each heading level is formatted differently.

Want to know how many heading levels you should use, when to use which heading level, and how to set up heading styles in Word or Google Docs? Then check out our in-depth article on APA headings .

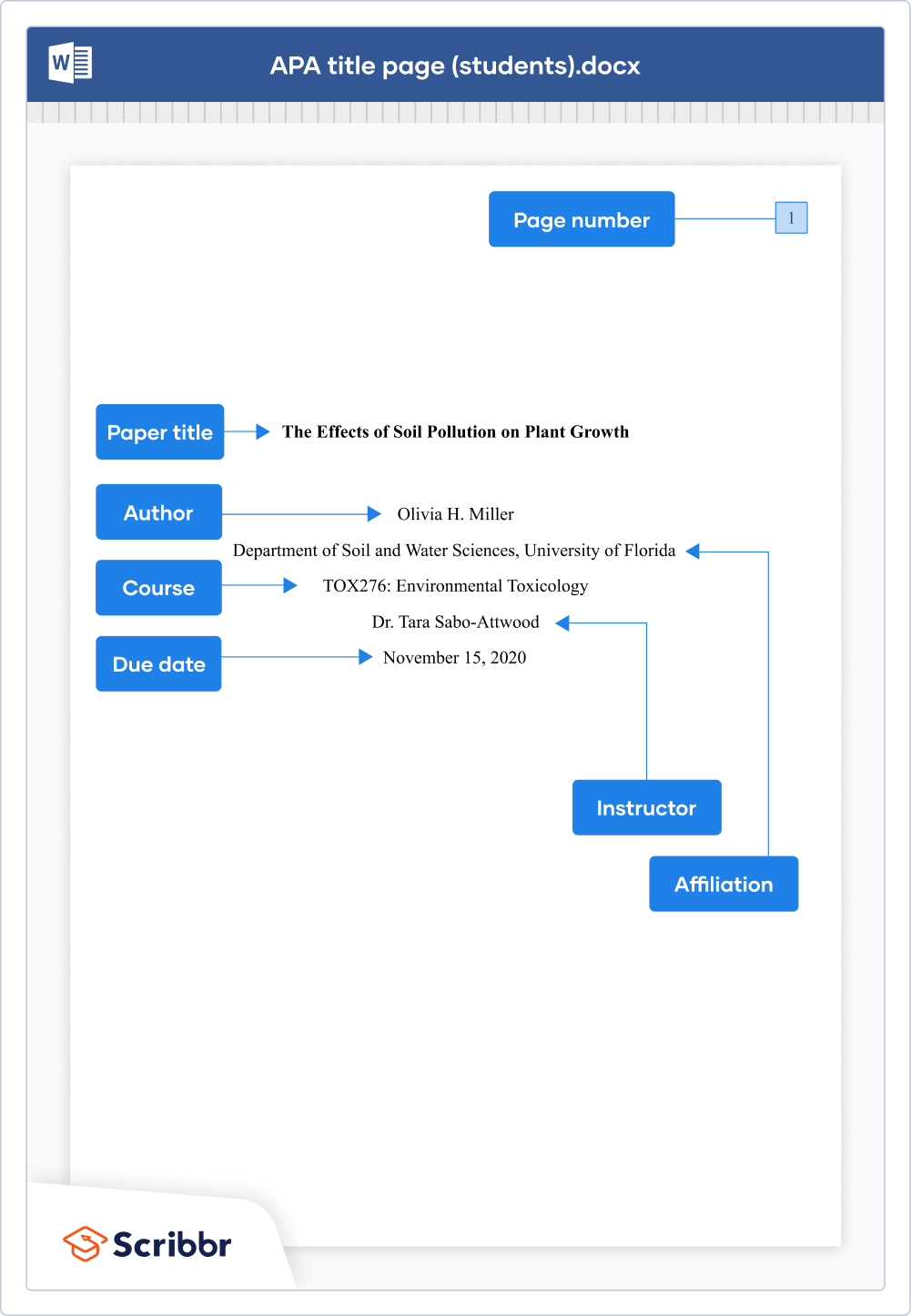

The title page is the first page of an APA Style paper. There are different guidelines for student and professional papers.

Both versions include the paper title and author’s name and affiliation. The student version includes the course number and name, instructor name, and due date of the assignment. The professional version includes an author note and running head .

For more information on writing a striking title, crediting multiple authors (with different affiliations), and writing the author note, check out our in-depth article on the APA title page .

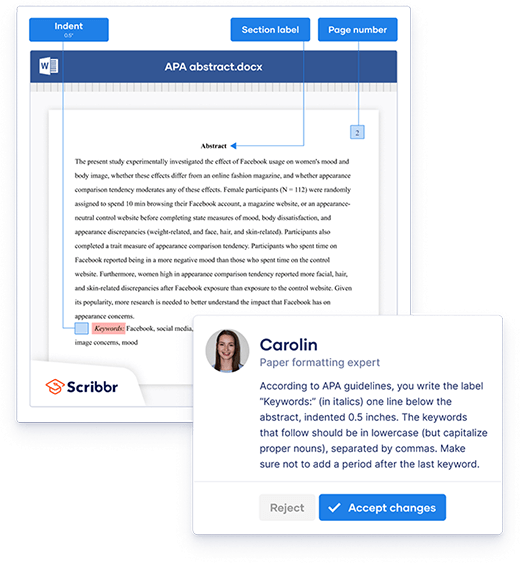

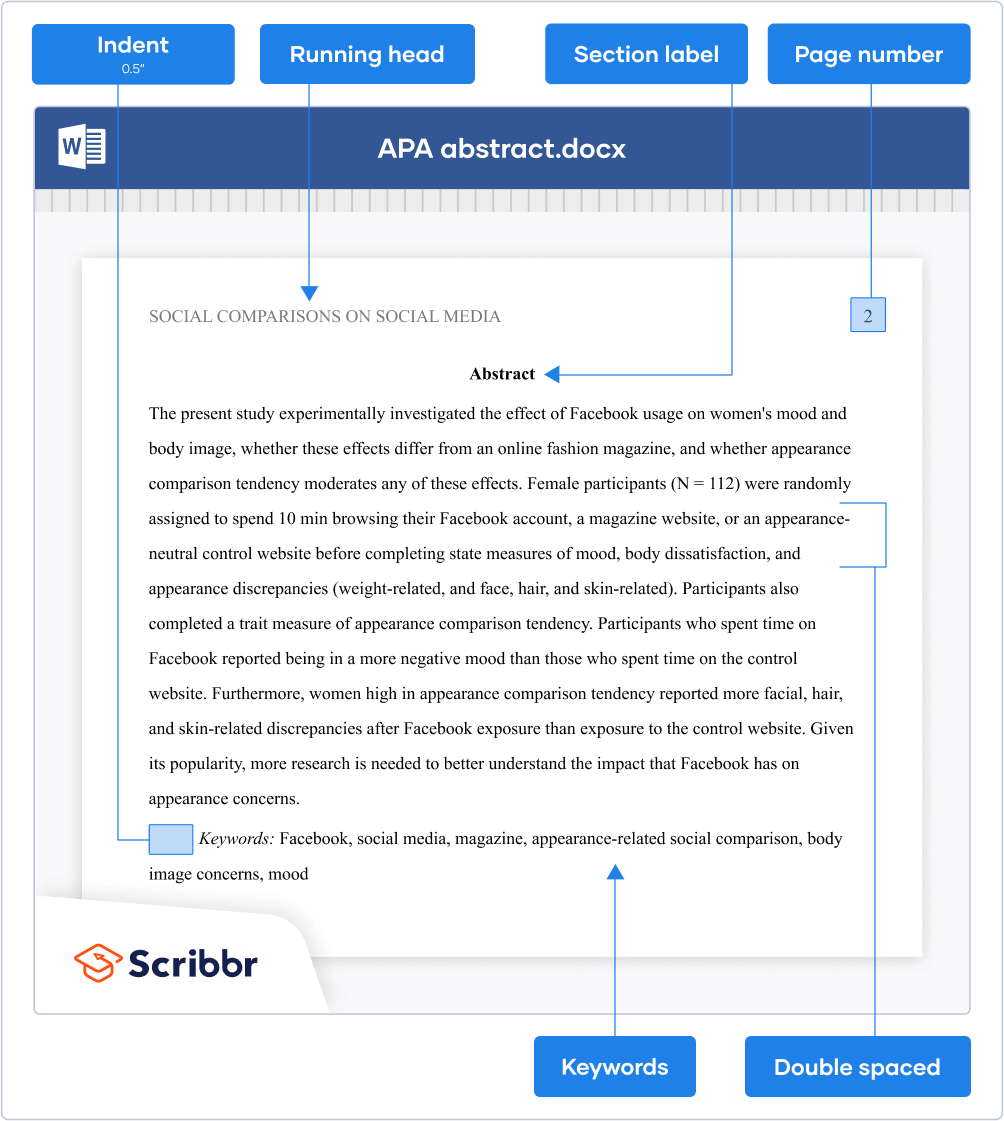

The abstract is a 150–250 word summary of your paper. An abstract is usually required in professional papers, but it’s rare to include one in student papers (except for longer texts like theses and dissertations).

The abstract is placed on a separate page after the title page . At the top of the page, write the section label “Abstract” (bold and centered). The contents of the abstract appear directly under the label. Unlike regular paragraphs, the first line is not indented. Abstracts are usually written as a single paragraph without headings or blank lines.

Directly below the abstract, you may list three to five relevant keywords . On a new line, write the label “Keywords:” (italicized and indented), followed by the keywords in lowercase letters, separated by commas.

APA Style does not provide guidelines for formatting the table of contents . It’s also not a required paper element in either professional or student papers. If your instructor wants you to include a table of contents, it’s best to follow the general guidelines.

Place the table of contents on a separate page between the abstract and introduction. Write the section label “Contents” at the top (bold and centered), press “Enter” once, and list the important headings with corresponding page numbers.

The APA reference page is placed after the main body of your paper but before any appendices . Here you list all sources that you’ve cited in your paper (through APA in-text citations ). APA provides guidelines for formatting the references as well as the page itself.

Creating APA Style references

Play around with the Scribbr Citation Example Generator below to learn about the APA reference format of the most common source types or generate APA citations for free with Scribbr’s APA Citation Generator .

Formatting the reference page

Write the section label “References” at the top of a new page (bold and centered). Place the reference entries directly under the label in alphabetical order.

Finally, apply a hanging indent , meaning the first line of each reference is left-aligned, and all subsequent lines are indented 0.5 inches.

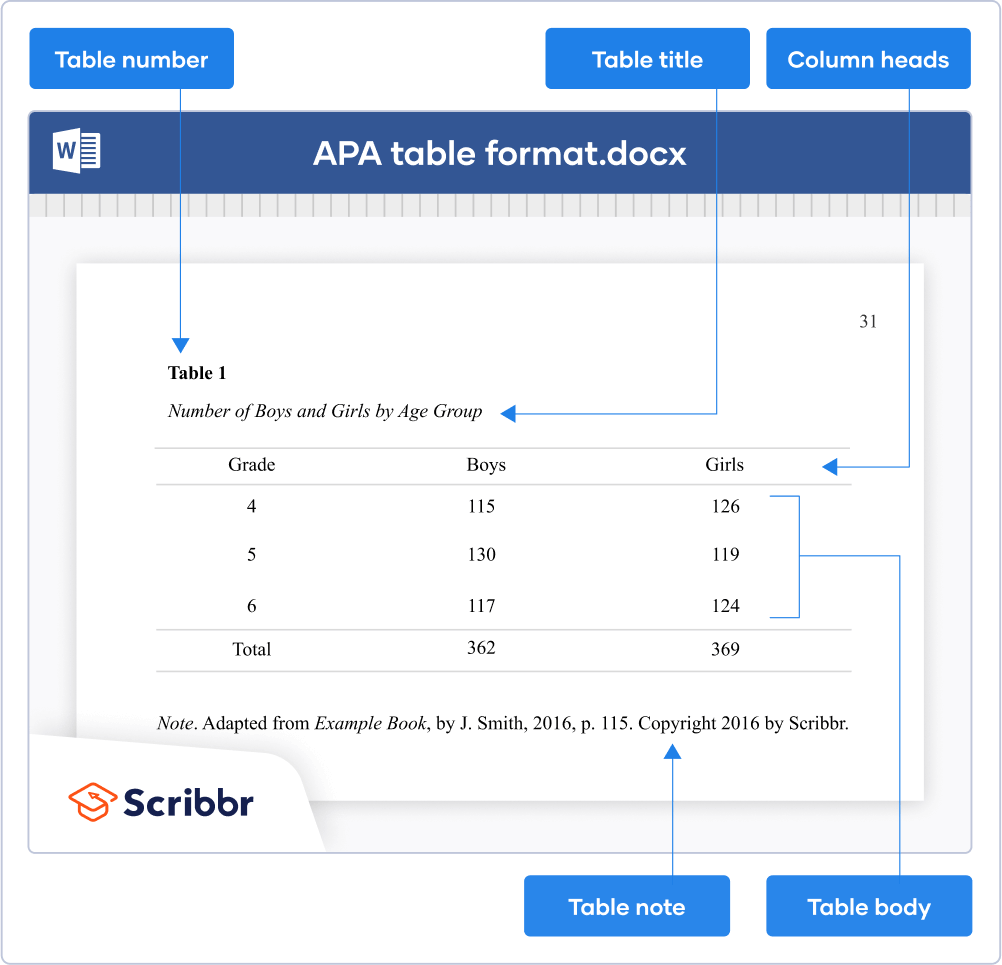

Tables and figures are presented in a similar format. They’re preceded by a number and title and followed by explanatory notes (if necessary).

Use bold styling for the word “Table” or “Figure” and the number, and place the title on a separate line directly below it (in italics and title case). Try to keep tables clean; don’t use any vertical lines, use as few horizontal lines as possible, and keep row and column labels concise.

Keep the design of figures as simple as possible. Include labels and a legend if needed, and only use color when necessary (not to make it look more appealing).

Check out our in-depth article about table and figure notes to learn when to use notes and how to format them.

The easiest way to set up APA format in Word is to download Scribbr’s free APA format template for student papers or professional papers.

Alternatively, you can watch Scribbr’s 5-minute step-by-step tutorial or check out our APA format guide with examples.

APA Style papers should be written in a font that is legible and widely accessible. For example:

- Times New Roman (12pt.)

- Arial (11pt.)

- Calibri (11pt.)

- Georgia (11pt.)

The same font and font size is used throughout the document, including the running head , page numbers, headings , and the reference page . Text in footnotes and figure images may be smaller and use single line spacing.

You need an APA in-text citation and reference entry . Each source type has its own format; for example, a webpage citation is different from a book citation .

Use Scribbr’s free APA Citation Generator to generate flawless citations in seconds or take a look at our APA citation examples .

Yes, page numbers are included on all pages, including the title page , table of contents , and reference page . Page numbers should be right-aligned in the page header.

To insert page numbers in Microsoft Word or Google Docs, click ‘Insert’ and then ‘Page number’.

APA format is widely used by professionals, researchers, and students in the social and behavioral sciences, including fields like education, psychology, and business.

Be sure to check the guidelines of your university or the journal you want to be published in to double-check which style you should be using.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2024, January 17). APA Formatting and Citation (7th Ed.) | Generator, Template, Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/format/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, apa title page (7th edition) | template for students & professionals, creating apa reference entries, beginner's guide to apa in-text citation, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Career Advice

Writing Effective Journal Essay Introductions

By James Phelan and Faye Halpern

You have / 5 articles left. Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/Ranjltsinh Rathod

Authors and editors in the humanities know that journals are more likely to accept scholarly essays with strong introductions and that such essays are more likely to influence academic conversations. Yet from our experiences as journal editors and authors, we also know that writers often struggle with introductions.

That’s understandably so: not only is a lot riding on an essay’s introduction, but it also needs to accomplish multiple rhetorical tasks efficiently. And while everyone knows the general purpose of the introduction -- to state the essay's thesis -- many people have trouble determining how best to get to that statement. In this article, our thesis is threefold. First, there are many effective strategies for building up to that statement. Second, underlying these strategies is a smaller set of common purposes. And finally, working with an awareness of both the first and second principles is a sound way to write strong introductions.

Strategies and Purposes

Here is an illustrative list of strategies, neither comprehensive nor mutually exclusive.

The Problem-Solution Strategy. You start by identifying a problem and unpacking its key dimensions and then propose your solution in the thesis statement or statements. (You no doubt recognize that we have just used this strategy.) For another example, see Catherine Gallagher, “ The Rise of Fictionality .”

The Question-Answer Strategy. You interweave descriptions of noteworthy phenomena and questions that they raise; you then propose answers in your thesis statement or statements. Some examples include Peter J. Rabinowitz’s “ Truth in Fiction: A Re-Examination of Audiences ” and Sarah Iles Johnston’s " The Greek Mythic Storyworld ."

The Revision of Received Wisdom Strategy. You begin by respectfully setting out a plausible and generally accepted view about the essay's central issue; you then point out flaws in this view and formulate an alternative view in your thesis statement or statements. Examples are Gerald Graff’s “ Why How We Read Trumps What We Read ” and John Hardwig’s “ The Role of Trust in Knowledge .”

The Bold Pronouncement Strategy. You announce an especially arresting thesis in your opening sentence or sentences. You then proceed to provide the relevant context for that thesis. For examples, see Brian McHale, “ Beginning to Think About Narrative in Poetry ” and Susan Wolf, “ Moral Saints .”

The Storytelling Strategy. You use an anecdote that illustrates salient aspects of the essay's central issue and then link the anecdote to your thesis about that issue. This strategy is often combined with one of the others, especially No. 1 and No. 2. Examples are Miriam Schoenfield’s “ Permission to Believe: Why Permissivism Is True and What It Tells Us About Irrelevant Influences on Belief ” and Jane Tompkins’s “ Sentimental Power: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Politics of Literary History .”

These strategies are ultimately means to accomplish three interrelated rhetorical purposes of strong introductions. All three are concerned with your readers, but the second also pays attention to your dialogic partners: the other scholars whose work you engage. Those three purposes are to:

- Immediately garner your audience’s interest. You and your readers know that problems beg for solutions, questions for answers. Revising received wisdom promises your audience something fresh and even perhaps contrarian. Making bold pronouncements invites your audience to see whether you can back them up. Telling stories asks your audience to engage in their instabilities and complications and to look for their resolution in your thesis and its supporting arguments.

- Situate yourself in the relevant scholarly conversations. Introductions aren’t the place for extensive reviews of previous scholarship, but they are the place for combining attention to issues raised by earlier commentators with giving your writing an argumentative edge. Questions, problems, revisions, pronouncements and storytelling in the service of argument -- all these rhetorical acts arise from the intersection between your distinctive take on your object of study and the takes of previous commentators. Consequently, regardless of your particular strategies, your introduction should orient your audience to the general intervention your essay wants to make in the scholarly conversation. Are you intervening by saying “yes and,” “yes but,” “no” or some combination of those responses?

- Help provide what Gordon Harvey calls a “motive,” which underlies and drives your argument. To put it another way, the strategies push you toward answering the “So what?” question. A strong introduction will signal to your readers that you’re aware of what’s at stake in your argument and why it matters. Although you can work with problems, questions, revisions, pronouncements and storytelling without addressing the “So what?” question, you are more likely to address it, at least implicitly, by pursuing the first two purposes. By pursuing all three, you are more likely not only to have your essay accepted but also to have it make a difference in your field.

Applying the Strategies

In practical terms, the main challenge of writing effective introductions is finding the sweet spot in which you properly balance your presentation of others’ work with your own ideas. We have two main suggestions for hitting that spot. The first involves a general approach to the challenge, and the second builds on it with more specific advice.

First, think of your introduction as needing both “a hook and an I,” a precept that becomes clearer when you think of introductions that have only one of those components. The “all hook and no I” introduction has paragraph upon paragraph (or even page upon page) describing how other scholars have viewed the issue the article addresses with little indication of how the author’s thesis fits into this conversation. Conversely, “the no hook and all I” introduction immediately launches into the author’s argument without establishing the current scholarly conversation that makes it meaningful.

This advice about avoiding the no hook and all I introduction may initially seem to run counter to the bold-pronouncement strategy we outlined above, but a closer look reveals that it is a distinctive variation, a “first I and then hook” progression. The strategy involves moving from your arresting assertion to the context that sharpens its stakes. At the same time, this possible objection helps clarify the situations in which it makes sense to employ the bold-pronouncement strategy: those in which readers of the journal will immediately recognize the striking quality of the thesis, the ways it seeks to take the scholarly conversation in a substantially new direction.

Why might authors go for just the hook or just the I? You might opt for the all-hook intro because you want to demonstrate up front your mastery of a body of relevant scholarship. A noble rationale, but one that often has the unfortunate effect of suggesting to readers that you are so immersed in that scholarship that you haven’t figured out your own point of view.

You might opt for the all-I intro because you want to give your readers credit for knowing a lot about the relevant scholarly conversation rather than rehearsing points you believe they are already familiar with. Another honorable justification, but one that often has the unfortunate effect of suggesting that you are actually not familiar with what other scholars have said.

We also want to note that using the hook and an I approach is ultimately less a matter of sheer quantity -- X number of sentences or paragraphs to others, and Y number to your ideas -- than of argumentative quality. Good introductions do not just repeat what other scholars have said; they analyze it and find an opening in it for their contribution.

Effective uses of the hook and an I can create that opening in numerous ways: they can point to significant aspects of your object or objects of study that previous work has overlooked; they can indicate how previous work explains some phenomena well but others less well; they can point to unrecognized but valuable implications or extensions of previous work; or they can begin to make the case that previous work needs to be corrected. The list could go on, but the key point is that you want to make your audience see the same opening you do and pique their interest in how you propose to fill it.

Consequences

This approach to introductions has ripple effects on the larger activity of writing an effective essay.

Introductions and abstracts. We often find that authors use their first paragraphs for their abstracts. We do not recommend this tactic, because, as we have discussed in a related article , introductions and abstracts have different purposes. As we say, abstracts are spoilers not teasers, because they give your audience a condensed version of your whole article: what your claim is, why it matters and how you will conduct your argument for it. Introductions, by contrast, are teasers that soon stop teasing. The tease comes with the hook, the construction of the opening for your argument, and ends with the full expression of the I, the articulation of your thesis statement or statements.

Order of composition. We have all heard the advice that one should write the introduction last. But as with most rhetorical matters, one size does not fit all. “Intro last” can be good advice when you’re writing an argument with many moving parts, and you need to write in some detail about all the parts before you are ready to craft your hook and I. “Intro first” can be good advice when you recognize that you need to do for yourself the kinds of things that we’re recommending your introduction needs to do for your reader. Beginning to write by constructing the opening you want to fill and how you want to fill it can be a productive way to guide your whole argument.

Two-way traffic between the introduction and the rest of the argument can also be an effective strategy. In such cases, the draft of the introduction guides the conduct of the argument, and then the details and directions of the argument lead you to revise that draft. And so on for as many rounds as you need to make everything as clear and compelling as possible.

Choosing a strategy. As for the issue of how to choose among viable strategies, again we say that there’s no one right answer. In other words, for most scholarly arguments more than one strategy can be adopted in the service of a strong introduction. Thus, you can try out different strategies in order to decide which one will be most likely to help you to convince your audience of the significance of your answer to the “So what?” question.

Introductions are often difficult to write. Some of the difficulty comes with the territory: writing an effective introduction requires you to have a thorough grasp of your own argument and why it matters for your audience. But we hope we can lessen that difficulty: our ideas about the underlying purposes of introductions and about the various ways to achieve those purposes aim to show you that good introductions are neither random nor mysterious. There are principles and patterns to follow, even if there’s no magic formula. We hope that your work with those principles and patterns can help you construct introductions that both you and your readers will regard as strong and appealing.

Why Did Shafik Step Down Now?

Congress grilled seven leaders over campus antisemitism in three hearings.

Share This Article

More from career advice.

How to Mitigate Bias and Hire the Best People

Patrick Arens shares an actionable approach to reviewing candidates that helps you make sure you select those most su

4 Ways to Reduce Higher Ed’s Leadership Deficit

Without good people-management skills, we’ll perpetuate the workforce instability and turnover on our campuses, warns

Shared Governance in Tumultuous Times

As the tradition is strongly tested, a faculty senate leader, Stephen J. Silvia, and a former provost, Scott A.

- Become a Member

- Sign up for Newsletters

- Learning & Assessment

- Diversity & Equity

- Career Development

- Labor & Unionization

- Shared Governance

- Academic Freedom

- Books & Publishing

- Financial Aid

- Residential Life

- Free Speech

- Physical & Mental Health

- Race & Ethnicity

- Sex & Gender

- Socioeconomics

- Traditional-Age

- Adult & Post-Traditional

- Teaching & Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Publishing

- Data Analytics

- Administrative Tech

- Alternative Credentials

- Financial Health

- Cost-Cutting

- Revenue Strategies

- Academic Programs

- Physical Campuses

- Mergers & Collaboration

- Fundraising

- Research Universities

- Regional Public Universities

- Community Colleges

- Private Nonprofit Colleges

- Minority-Serving Institutions

- Religious Colleges

- Women's Colleges

- Specialized Colleges

- For-Profit Colleges

- Executive Leadership

- Trustees & Regents

- State Oversight

- Accreditation

- Politics & Elections

- Supreme Court

- Student Aid Policy

- Science & Research Policy

- State Policy

- Colleges & Localities

- Employee Satisfaction

- Remote & Flexible Work

- Staff Issues

- Study Abroad

- International Students in U.S.

- U.S. Colleges in the World

- Intellectual Affairs

- Seeking a Faculty Job

- Advancing in the Faculty

- Seeking an Administrative Job

- Advancing as an Administrator

- Beyond Transfer

- Call to Action

- Confessions of a Community College Dean

- Higher Ed Gamma

- Higher Ed Policy

- Just Explain It to Me!

- Just Visiting

- Law, Policy—and IT?

- Leadership & StratEDgy

- Leadership in Higher Education

- Learning Innovation

- Online: Trending Now

- Resident Scholar

- University of Venus

- Student Voice

- Academic Life

- Health & Wellness

- The College Experience

- Life After College

- Academic Minute

- Weekly Wisdom

- Reports & Data

- Quick Takes

- Advertising & Marketing

- Consulting Services

- Data & Insights

- Hiring & Jobs

- Event Partnerships

4 /5 Articles remaining this month.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

- Sign Up, It’s FREE

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Journal article analysis assignments require you to summarize and critically assess the quality of an empirical research study published in a scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer-reviewed] journal. The article may be assigned by the professor, chosen from course readings listed in the syllabus, or you must locate an article on your own, usually with the requirement that you search using a reputable library database, such as, JSTOR or ProQuest . The article chosen is expected to relate to the overall discipline of the course, specific course content, or key concepts discussed in class. In some cases, the purpose of the assignment is to analyze an article that is part of the literature review for a future research project.

Analysis of an article can be assigned to students individually or as part of a small group project. The final product is usually in the form of a short paper [typically 1- 6 double-spaced pages] that addresses key questions the professor uses to guide your analysis or that assesses specific parts of a scholarly research study [e.g., the research problem, methodology, discussion, conclusions or findings]. The analysis paper may be shared on a digital course management platform and/or presented to the class for the purpose of promoting a wider discussion about the topic of the study. Although assigned in any level of undergraduate and graduate coursework in the social and behavioral sciences, professors frequently include this assignment in upper division courses to help students learn how to effectively identify, read, and analyze empirical research within their major.

Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Benefits of Journal Article Analysis Assignments

Analyzing and synthesizing a scholarly journal article is intended to help students obtain the reading and critical thinking skills needed to develop and write their own research papers. This assignment also supports workplace skills where you could be asked to summarize a report or other type of document and report it, for example, during a staff meeting or for a presentation.

There are two broadly defined ways that analyzing a scholarly journal article supports student learning:

Improve Reading Skills

Conducting research requires an ability to review, evaluate, and synthesize prior research studies. Reading prior research requires an understanding of the academic writing style , the type of epistemological beliefs or practices underpinning the research design, and the specific vocabulary and technical terminology [i.e., jargon] used within a discipline. Reading scholarly articles is important because academic writing is unfamiliar to most students; they have had limited exposure to using peer-reviewed journal articles prior to entering college or students have yet to gain exposure to the specific academic writing style of their disciplinary major. Learning how to read scholarly articles also requires careful and deliberate concentration on how authors use specific language and phrasing to convey their research, the problem it addresses, its relationship to prior research, its significance, its limitations, and how authors connect methods of data gathering to the results so as to develop recommended solutions derived from the overall research process.

Improve Comprehension Skills

In addition to knowing how to read scholarly journals articles, students must learn how to effectively interpret what the scholar(s) are trying to convey. Academic writing can be dense, multi-layered, and non-linear in how information is presented. In addition, scholarly articles contain footnotes or endnotes, references to sources, multiple appendices, and, in some cases, non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts] that can break-up the reader’s experience with the narrative flow of the study. Analyzing articles helps students practice comprehending these elements of writing, critiquing the arguments being made, reflecting upon the significance of the research, and how it relates to building new knowledge and understanding or applying new approaches to practice. Comprehending scholarly writing also involves thinking critically about where you fit within the overall dialogue among scholars concerning the research problem, finding possible gaps in the research that require further analysis, or identifying where the author(s) has failed to examine fully any specific elements of the study.

In addition, journal article analysis assignments are used by professors to strengthen discipline-specific information literacy skills, either alone or in relation to other tasks, such as, giving a class presentation or participating in a group project. These benefits can include the ability to:

- Effectively paraphrase text, which leads to a more thorough understanding of the overall study;

- Identify and describe strengths and weaknesses of the study and their implications;

- Relate the article to other course readings and in relation to particular research concepts or ideas discussed during class;

- Think critically about the research and summarize complex ideas contained within;

- Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

- Model the type of source summary and critique you should do for any college-level research paper; and,

- Increase interest and engagement with the research problem of the study as well as with the discipline.

Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946.

Structure and Organization

A journal article analysis paper should be written in paragraph format and include an instruction to the study, your analysis of the research, and a conclusion that provides an overall assessment of the author's work, along with an explanation of what you believe is the study's overall impact and significance. Unless the purpose of the assignment is to examine foundational studies published many years ago, you should select articles that have been published relatively recently [e.g., within the past few years].

Since the research has been completed, reference to the study in your paper should be written in the past tense, with your analysis stated in the present tense [e.g., “The author portrayed access to health care services in rural areas as primarily a problem of having reliable transportation. However, I believe the author is overgeneralizing this issue because...”].

Introduction Section

The first section of a journal analysis paper should describe the topic of the article and highlight the author’s main points. This includes describing the research problem and theoretical framework, the rationale for the research, the methods of data gathering and analysis, the key findings, and the author’s final conclusions and recommendations. The narrative should focus on the act of describing rather than analyzing. Think of the introduction as a more comprehensive and detailed descriptive abstract of the study.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the introduction section may include:

- Who are the authors and what credentials do they hold that contributes to the validity of the study?

- What was the research problem being investigated?

- What type of research design was used to investigate the research problem?

- What theoretical idea(s) and/or research questions were used to address the problem?

- What was the source of the data or information used as evidence for analysis?

- What methods were applied to investigate this evidence?

- What were the author's overall conclusions and key findings?

Critical Analysis Section

The second section of a journal analysis paper should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the study and analyze its significance and impact. This section is where you shift the narrative from describing to analyzing. Think critically about the research in relation to other course readings, what has been discussed in class, or based on your own life experiences. If you are struggling to identify any weaknesses, explain why you believe this to be true. However, no study is perfect, regardless of how laudable its design may be. Given this, think about the repercussions of the choices made by the author(s) and how you might have conducted the study differently. Examples can include contemplating the choice of what sources were included or excluded in support of examining the research problem, the choice of the method used to analyze the data, or the choice to highlight specific recommended courses of action and/or implications for practice over others. Another strategy is to place yourself within the research study itself by thinking reflectively about what may be missing if you had been a participant in the study or if the recommended courses of action specifically targeted you or your community.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the analysis section may include:

Introduction

- Did the author clearly state the problem being investigated?

- What was your reaction to and perspective on the research problem?

- Was the study’s objective clearly stated? Did the author clearly explain why the study was necessary?

- How well did the introduction frame the scope of the study?

- Did the introduction conclude with a clear purpose statement?

Literature Review

- Did the literature review lay a foundation for understanding the significance of the research problem?

- Did the literature review provide enough background information to understand the problem in relation to relevant contexts [e.g., historical, economic, social, cultural, etc.].

- Did literature review effectively place the study within the domain of prior research? Is anything missing?

- Was the literature review organized by conceptual categories or did the author simply list and describe sources?

- Did the author accurately explain how the data or information were collected?

- Was the data used sufficient in supporting the study of the research problem?

- Was there another methodological approach that could have been more illuminating?

- Give your overall evaluation of the methods used in this article. How much trust would you put in generating relevant findings?

Results and Discussion

- Were the results clearly presented?

- Did you feel that the results support the theoretical and interpretive claims of the author? Why?

- What did the author(s) do especially well in describing or analyzing their results?

- Was the author's evaluation of the findings clearly stated?

- How well did the discussion of the results relate to what is already known about the research problem?

- Was the discussion of the results free of repetition and redundancies?

- What interpretations did the authors make that you think are in incomplete, unwarranted, or overstated?

- Did the conclusion effectively capture the main points of study?

- Did the conclusion address the research questions posed? Do they seem reasonable?

- Were the author’s conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented?

- Has the author explained how the research added new knowledge or understanding?

Overall Writing Style

- If the article included tables, figures, or other non-textual elements, did they contribute to understanding the study?

- Were ideas developed and related in a logical sequence?

- Were transitions between sections of the article smooth and easy to follow?

Overall Evaluation Section

The final section of a journal analysis paper should bring your thoughts together into a coherent assessment of the value of the research study . This section is where the narrative flow transitions from analyzing specific elements of the article to critically evaluating the overall study. Explain what you view as the significance of the research in relation to the overall course content and any relevant discussions that occurred during class. Think about how the article contributes to understanding the overall research problem, how it fits within existing literature on the topic, how it relates to the course, and what it means to you as a student researcher. In some cases, your professor will also ask you to describe your experiences writing the journal article analysis paper as part of a reflective learning exercise.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the conclusion and evaluation section may include:

- Was the structure of the article clear and well organized?

- Was the topic of current or enduring interest to you?

- What were the main weaknesses of the article? [this does not refer to limitations stated by the author, but what you believe are potential flaws]

- Was any of the information in the article unclear or ambiguous?

- What did you learn from the research? If nothing stood out to you, explain why.

- Assess the originality of the research. Did you believe it contributed new understanding of the research problem?

- Were you persuaded by the author’s arguments?

- If the author made any final recommendations, will they be impactful if applied to practice?

- In what ways could future research build off of this study?

- What implications does the study have for daily life?

- Was the use of non-textual elements, footnotes or endnotes, and/or appendices helpful in understanding the research?

- What lingering questions do you have after analyzing the article?

NOTE: Avoid using quotes. One of the main purposes of writing an article analysis paper is to learn how to effectively paraphrase and use your own words to summarize a scholarly research study and to explain what the research means to you. Using and citing a direct quote from the article should only be done to help emphasize a key point or to underscore an important concept or idea.

Business: The Article Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing, Grand Valley State University; Bachiochi, Peter et al. "Using Empirical Article Analysis to Assess Research Methods Courses." Teaching of Psychology 38 (2011): 5-9; Brosowsky, Nicholaus P. et al. “Teaching Undergraduate Students to Read Empirical Articles: An Evaluation and Revision of the QALMRI Method.” PsyArXi Preprints , 2020; Holster, Kristin. “Article Evaluation Assignment”. TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology . Washington DC: American Sociological Association, 2016; Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reviewer's Guide . SAGE Reviewer Gateway, SAGE Journals; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Gyuris, Emma, and Laura Castell. "To Tell Them or Show Them? How to Improve Science Students’ Skills of Critical Reading." International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 21 (2013): 70-80; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students Make the Most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Writing Tip

Not All Scholarly Journal Articles Can Be Critically Analyzed

There are a variety of articles published in scholarly journals that do not fit within the guidelines of an article analysis assignment. This is because the work cannot be empirically examined or it does not generate new knowledge in a way which can be critically analyzed.

If you are required to locate a research study on your own, avoid selecting these types of journal articles:

- Theoretical essays which discuss concepts, assumptions, and propositions, but report no empirical research;

- Statistical or methodological papers that may analyze data, but the bulk of the work is devoted to refining a new measurement, statistical technique, or modeling procedure;

- Articles that review, analyze, critique, and synthesize prior research, but do not report any original research;

- Brief essays devoted to research methods and findings;

- Articles written by scholars in popular magazines or industry trade journals;

- Academic commentary that discusses research trends or emerging concepts and ideas, but does not contain citations to sources; and

- Pre-print articles that have been posted online, but may undergo further editing and revision by the journal's editorial staff before final publication. An indication that an article is a pre-print is that it has no volume, issue, or page numbers assigned to it.

Journal Analysis Assignment - Myers . Writing@CSU, Colorado State University; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Giving an Oral Presentation >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Thursday, February 23: The Clark Library is closed today.

APA Style (7th Edition) Citation Guide: Journal Articles

- Introduction

- Journal Articles

- Magazine/Newspaper Articles

- Books & Ebooks

- Government & Legal Documents

- Biblical Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Films/Videos/TV Shows

- How to Cite: Other

- Additional Help

Table of Contents

Journal article from library database with doi - one author, journal article from library database with doi - multiple authors, journal article from a website - one author.

Journal Article- No DOI

Note: All citations should be double spaced and have a hanging indent in a Reference List.

A "hanging indent" means that each subsequent line after the first line of your citation should be indented by 0.5 inches.

This Microsoft support page contains instructions about how to format a hanging indent in a paper.

- APA 7th. ed. Journal Article Reference Checklist

If an item has no author, start the citation with the article title.

When an article has one to twenty authors, all authors' names are cited in the References List entry. When an article has twenty-one or more authors list the first nineteen authors followed by three spaced ellipse points (. . .) , and then the last author's name. Rules are different for in-text citations; please see the examples provided.

Cite author names in the order in which they appear on the source, not in alphabetical order (the first author is usually the person who contributed the most work to the publication).

Italicize titles of journals, magazines and newspapers. Do not italicize or use quotation marks for the titles of articles.

Capitalize only the first letter of the first word of the article title. If there is a colon in the article title, also capitalize the first letter of the first word after the colon.

If an item has no date, use the short form n.d. where you would normally put the date.

Volume and Issue Numbers

Italicize volume numbers but not issue numbers.

Retrieval Dates

Most articles will not need these in the citation. Only use them for online articles from places where content may change often, like a free website or a wiki.

Page Numbers

If an article doesn't appear on continuous pages, list all the page numbers the article is on, separated by commas. For example (4, 6, 12-14)

Library Database

Do not include the name of a database for works obtained from most academic research databases (e.g. APA PsycInfo, CINAHL) because works in these resources are widely available. Exceptions are Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ERIC, ProQuest Dissertations, and UpToDate.

Include the DOI (formatted as a URL: https://doi.org/...) if it is available. If you do not have a DOI, include a URL if the full text of the article is available online (not as part of a library database). If the full text is from a library database, do not include a DOI, URL, or database name.

In the Body of a Paper

Books, Journals, Reports, Webpages, etc.: When you refer to titles of a “stand-alone work,” as the APA calls them on their APA Style website, such as books, journals, reports, and webpages, you should italicize them. Capitalize words as you would for an article title in a reference, e.g., In the book Crying in H Mart: A memoir , author Michelle Zauner (2021) describes her biracial origin and its impact on her identity.

Article or Chapter: When you refer to the title of a part of a work, such as an article or a chapter, put quotation marks around the title and capitalize it as you would for a journal title in a reference, e.g., In the chapter “Where’s the Wine,” Zauner (2021) describes how she decided to become a musician.

The APA Sample Paper below has more information about formatting your paper.

- APA 7th ed. Sample Paper

Author's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number. https://doi.org/doi number

Smith, K. F. (2022). The public and private dialogue about the American family on television: A second look. Journal of Media Communication, 50 (4), 79-110. https://doi.org/10.1152/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02864.x

Note: The DOI number is formatted as a URL: https://doi.org/10.1152/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02864.xIf

In-Text Paraphrase:

(Author's Last Name, Year)

Example: (Smith, 2000)

In-Text Quote:

(Author's Last Name, Year, p. Page Number)

Example: (Smith, 2000, p. 80)

Author's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given., & Last Name of Second Author, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number. https://doi.org/doi number

Note: Separate the authors' names by putting a comma between them. For the final author listed add an ampersand (&) after the comma and before the final author's last name.

Note: In the reference list invert all authors' names; give last names and initials for only up to and including 20 authors. When a source has 21 or more authors, include the first 19 authors’ names, then three ellipses (…), and add the last author’s name. Don't include an ampersand (&) between the ellipsis and final author.

Note : For works with three or more authors, the first in-text citation is shortened to include the first author's surname followed by "et al."

Reference List Examples

Two to 20 Authors

Case, T. A., Daristotle, Y. A., Hayek, S. L., Smith, R. R., & Raash, L. I. (2011). College students' social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 3 (2), 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.010

21 or more authors

Kalnay, E., Kanamitsu, M., Kistler, R., Collins, W., Deaven, D., Gandin, L., Iredell, M., Saha, J., Mo, K. C., Ropelewski, C., Wang, J., Leetma, A., . . . Joseph, D. (1996). The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society , 77 (3), 437-471. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>2.0.CO;2

In-Text Citations

Two Authors/Editors

(Case & Daristotle, 2011)

Direct Quote: (Case & Daristotle, 2011, p. 57)

Three or more Authors/Editors

(Case et al., 2011)

Direct Quote: (Case et al., 2011, p. 57)

Author's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number if given). URL

Flachs, A. (2010). Food for thought: The social impact of community gardens in the Greater Cleveland Area. Electronic Green Journal, 1 (30). http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6bh7j4z4

Example: (Flachs, 2010)

Example: (Flachs, 2010, Conclusion section, para. 3)

Note: In this example there were no visible page numbers or paragraph numbers; in this case you can cite the section heading and the number of the paragraph in that section to identify where your quote came from. If there are no page or paragraph numbers and no marked section, leave this information out.

Journal Article - No DOI

Author's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number. URL [if article is available online, not as part of a library database]

Full-Text Available Online (Not as Part of a Library Database):

Steinberg, M. P., & Lacoe, J. (2017). What do we know about school discipline reform? Assessing the alternatives to suspensions and expulsions. Education Next, 17 (1), 44–52. https://www.educationnext.org/what-do-we-know-about-school-discipline-reform-suspensions-expulsions/

Example: (Steinberg & Lacoe, 2017)

(Author's Last Name, Year, p. Page number)

Example: (Steinberg & Lacoe, 2017, p. 47)

Full-Text Available in Library Database:

Jungers, W. L. (2010). Biomechanics: Barefoot running strikes back. Nature, 463 (2), 433-434.

Example: (Jungers, 2010)

Example: (Jungers, 2010, p. 433)

- << Previous: How to Cite: Common Sources

- Next: Magazine/Newspaper Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 13, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://libguides.up.edu/apa

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Oral Maxillofac Pathol

- v.17(1); Jan-Apr 2013

Art of reading a journal article: Methodically and effectively

Rv subramanyam.

Department of Oral Pathology, Drs Sudha and Nageswara Rao Siddhartha Institute of Dental Sciences, Gannavaram, Andhra Pradesh, India

Background:

Reading scientific literature is mandatory for researchers and clinicians. With an overflow of medical and dental journals, it is essential to develop a method to choose and read the right articles.

To outline a logical and orderly approach to reading a scientific manuscript. By breaking down the task into smaller, step-by-step components, one should be able to attain the skills to read a scientific article with ease.

The reader should begin by reading the title, abstract and conclusions first. If a decision is made to read the entire article, the key elements of the article can be perused in a systematic manner effectively and efficiently. A cogent and organized method is presented to read articles published in scientific journals.

Conclusion:

One can read and appreciate a scientific manuscript if a systematic approach is followed in a simple and logical manner.

INTRODUCTION

“ We are drowning in information but starved for knowledge .” John Naisbitt

It has become essential for the clinicians, researchers, and students to read articles from scientific journals. This is not only to keep abreast of progress in the speciality concerned but also to be aware of current trends in providing optimum healthcare to the patients. Reading scientific literature is a must for students interested in research, for choosing their topics and carrying out their experiments. Scientific literature in that field will help one understand what has already been discovered and what questions remain unanswered and thus help in designing one's research project. Sackett (1981)[ 1 ] and Durbin (2009)[ 2 ] suggested various reasons why most of us read journal articles and some of these are listed in Table 1 .

Common reasons for reading journal articles

The scientific literature is burgeoning at an exponential rate. Between 1978 and 1985, nearly 272,344 articles were published annually and listed in Medline. Between 1986 and 1993, this number reached 344,303 articles per year, and between 1994 and 2001, the figure has grown to 398,778 articles per year.[ 3 ] To be updated with current knowledge, a physician practicing general medicine has to read 17 articles a day, 365 days a year.[ 4 ]

In spite of the internet rapidly gaining a strong foothold as a quick source of obtaining information, reading journal articles, whether from print or electronic media, still remains the most common way of acquiring new information for most of us.[ 2 ] Newspaper reports or novels can be read in an insouciant manner, but reading research reports and scientific articles requires concentration and meticulous approach. At present, there are 1312 dentistry journals listed in Pubmed.[ 5 ] How can one choose an article, read it purposefully, effectively, and systematically? The aim of this article is to provide an answer to this question by presenting an efficient and methodical approach to a scientific manuscript. However, the reader is informed that this paper is mainly intended for the amateur reader unaccustomed to scientific literature and not for the professional interested in critical appraisal of journal articles.

TYPES OF JOURNAL ARTICLES

Different types of papers are published in medical and dental journals. One should be aware of each kind; especially, when one is looking for a specific type of an article. Table 2 gives different categories of papers published in journals.

Types of articles published in a journal

In general, scientific literature can be primary or secondary. Reports of original research form the “primary literature”, the “core” of scientific publications. These are the articles written to present findings on new scientific discoveries or describe earlier work to acknowledge it and place new findings in the proper perspective. “Secondary literature” includes review articles, books, editorials, practice guidelines, and other forms of publication in which original research information is reviewed.[ 6 ] An article published in a peer-reviewed journal is more valued than one which is not.

An original research article should consist of the following headings: Structured abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD) and may be Randomized Control Trial (RCT), Controlled Clinical Trial (CCT), Experiment, Survey, and Case-control or Cohort study. Reviews could be non-systematic (narrative) or systematic. A narrative review is a broad overview of a topic without any specific question, more or less an update, and qualitative summary. On the other hand, a systematic review typically addresses a specific question about a topic, details the methods by which papers were identified in the literature, uses predetermined criteria for selection of papers to be included in the review, and qualitatively evaluates them. A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review in which numeric results of several separate studies are statistically combined to determine the outcome of a specific research question.[ 7 – 9 ] Some are invited reviews, requested by the Editor, from an expert in a particular field of study.

A case study is a report of a single clinical case, whereas, a case series is a description of a number of such cases. Case reports and case series are description of disease (s) generally considered rare or report of heretofore unknown or unusual findings in a well-recognized condition, unique procedure, imaging technique, diagnostic test, or treatment method. Technical notes are description of new, innovative techniques, or modifications to existing procedures. A pictorial essay is a teaching article with images and legends but has limited text. Commentary is a short article on an author's personal opinion of a specific topic and could be controversial. An editorial, written by the editor of the journal or invited, can be perspective (about articles published in that particular issue) or persuasive (arguing a specific point of view). Other articles published in a journal include letters to the editor, book reviews, conference proceedings and abstracts, and abstracts from other journals.[ 10 ]

WHAT TO READ IN A JOURNAL? – CHOOSING THE RIGHT ARTICLE

Not all research articles published are excellent, and it is pragmatic to decide if the quality of the study warrants reading of the manuscript. The first step for a reader is to choose a right article for reading, depending on one's individual requirement. The next step is to read the selected article methodically and efficiently.[ 2 ] A simple decision-making flowchart is depicted in [ Figure 1 ], which helps one to decide the type of article to select. This flowchart is meant for one who has a specific intent of choosing a particular type of article and not for one who intends to browse through a journal.

Schematic flowchart of the first step in choosing an article to read

HOW TO START READING AN ARTICLE?

“ There is an art of reading, as well as an art of thinking, and an art of writing .” Clarence Day

At first glance, a journal article might appear intimidating for some or confusing for others with its tables and graphs. Reading a research article can be a frustrating experience, especially for the one who has not mastered the art of reading scientific literature. Just like there is a method to extract a tooth or prepare a cavity, one can also learn to read research articles by following a systematic approach. Most scientific articles are organized as follows:[ 2 , 11 ]

- Title: Topic and information about the authors.

- Abstract: Brief overview of the article.

- Introduction: Background information and statement of the research hypothesis.

- Methods: Details of how the study was conducted, procedures followed, instruments used and variables measured.

- Results: All the data of the study along with figures, tables and/or graphs.

- Discussion: The interpretation of the results and implications of the study.

- References/Bibliography: Citations of sources from where the information was obtained.

Review articles do not usually follow the above pattern, unless they are systematic reviews or meta-analysis. The cardinal rule is: Never start reading an article from the beginning to the end. It is better to begin by identifying the conclusions of the study by reading the title and the abstract.[ 12 ] If the article does not have an abstract, read the conclusions or the summary at the end of the article first. After reading the abstract or conclusions, if the reader deems it is interesting or useful, then the entire article can be read [ Figure 2 ].

Decision-making flowchart to decide whether to read the chosen article or not

Like the title of a movie which attracts a filmgoer, the title of the article is the one which attracts a reader in the first place. A good title will inform the potential reader a great deal about the study to decide whether to go ahead with the paper or dismiss it. Most readers prefer titles that are descriptive and self-explanatory without having to look at the entire article to know what it is all about.[ 2 ] For example, the paper entitled “Microwave processing – A blessing for pathologists” gives an idea about the article in general to the reader. But there is no indication in the title whether it is a review article on microwave processing or an original research. If the title had been “Comparison of Microwave with Conventional Tissue Processing on quality of histological sections”, even the insouciant reader would have a better understanding of the content of the paper.

Abstract helps us determine whether we should read the entire article or not. In fact, most journals provide abstract free of cost online allowing us to decide whether we need to purchase the entire article. Most scientific journals now have a structured abstract with separate subheadings like introduction (background or hypothesis), methods, results and conclusions making it easy for a reader to identify important parts of the study quickly.[ 13 ] Moreover, there is usually a restriction about the number of words that can be included in an abstract. This makes the abstract concise enough for one to read rapidly.

The abstract can be read in a systematic way by answering certain fundamental questions like what was the study about, why and how was the study conducted, the results and their inferences. The reader should make a note of any questions that were raised while reading the abstract and be sure that answers have been found after reading the entire article.[ 12 ]

Reading the entire article

Once the reader has decided to read the entire article, one can begin with the introduction.

The purpose of the introduction is to provide the rationale for conducting the study. This section usually starts with existing knowledge and previous research of the topic under consideration. Typically, this section concludes with identification of gaps in the literature and how these gaps stimulated the researcher to design a new study.[ 12 ] A good introduction should provide proper background for the study. The aims and objectives are usually mentioned at the end of the introduction. The reader should also determine whether a research hypothesis (study hypothesis) was stated and later check whether it was answered under the discussion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This section gives the technical details of how the experiments were carried out. In most of the research articles, all details are rarely included but there should be enough information to understand how the study was carried out.[ 12 ] Information about the number of subjects included in the study and their categorization, sampling methods, the inclusion criteria (who can be in) and exclusion criteria (who cannot be in) and the variables chosen can be derived by reading this section. The reader should get acquainted with the procedures and equipment used for data collection and find out whether they were appropriate.

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

In this section, the researchers give details about the data collected, either in the form of figures, tables and/or graphs. Ideally, interpretation of data should not be reported in this section, though statistical analyses are presented. The reader should meticulously go through this segment of the manuscript and find out whether the results were reliable (same results over time) and valid (measure what it is supposed to measure). An important aspect is to check if all the subjects present in the beginning of the study were accounted for at the end of the study. If the answer is no, the reader should check whether any explanation was provided.

Results that were statistically significant and results that were not, must be identified. One should also observe whether a correct statistical test was employed for analysis and was the level of significance appropriate for the study. To appreciate the choice of a statistical test, one requires an understanding of the hypothesis being tested.[ 14 , 15 ] Table 3 provides a list of commonly used statistical tests used in scientific publications. Description and interpretation of these tests is beyond the scope of this paper. It is wise to remember the following advice: It is not only important to know whether a difference or association is statistically significant but also appreciate whether it is large or substantial enough to be useful clinically.[ 16 ] In other words, what is statistically significant may not be clinically significant.

Basic statistics commonly used in scientific publications