Heritage Day Essay Guide for Grade 10 Learners

This page contains an essay guide for Grade 10 History learners on how to write a Heritage Day essay (introduction, body, and conclusion). On the 24th of September every year in South Africa, there is a great celebration of all cultures and heritages of all South Africans. This was after the Inkatha Freedom Party proposal in 1996.

Background on South African Heritage Day

Before you write your essay, you should first know what heritage day is and what it means.

The word ‘heritage’ can be used in different ways. One use of the word emphasises our heritage as human beings. Another use of the word relates to the ways in which people remember the past, through heritage sites, museums, through the construction of monuments and memorials and in families and communities (oral history). Some suggest that heritage is everything that is handed down to us from the past.

One branch of Heritage Studies engages critically (debates) with issues of heritage and public representations of the past, and conservation.

It asks us to think about how the past is remembered and what a person or community or country chooses to remember about the past. It is also concerned with the way the events from the past are portrayed in museums and monuments, and in traditions. It includes the issue of whose past is remembered and whose past has been left unrecognised or, for example, how a monument or museum could be made more inclusive.

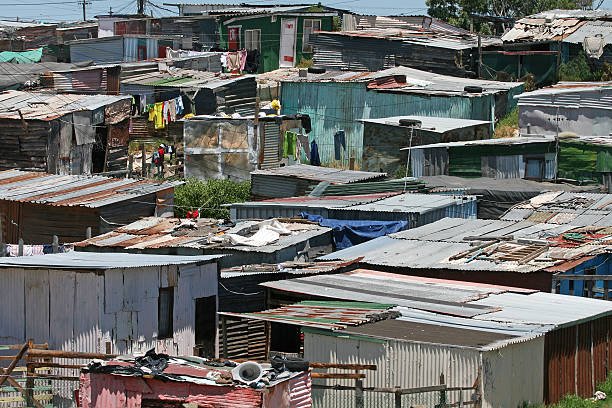

Important: you should include relevant images to go with your key points. You can find plenty of images on the internet, as long as you provide the credits/sources.

When you write your Heritage Day essay as a grade 10 student, you will get great marks if you include the following structure:

- Provide a brief history linked to heritage day

- The main key issues you will be discussing throughout your essay

- Explain the changes that were made to this public holiday.

- Explain how the day is celebrated in schools, families, workplaces and other institutions like churches etc.

- How does the celebration of the holiday bring unity and close the gaps of the past?

- Explain how the celebration of the day enforces the application of the constitution of South Africa.

- What key points did your essay cover?

- What new knowledge did you learn or discover?

- What are your views on “Heritage Day”?

Example of “Heritage Day” Essay for Grade 10 Students

Below is an example of how to write an essay about Heritage Day for grade 10 learners, using the structure discussed above:

Introduction:

Heritage Day, celebrated on the 24th of September, is a South African public holiday that serves as a reminder of the nation’s rich cultural heritage and diverse history. The day was established to honor the various cultures, traditions, and beliefs that make South Africa a truly unique and diverse country. This essay will discuss the history of Heritage Day, the changes made to this public holiday, and how its celebration promotes unity and reinforces the South African Constitution .

Changes to Heritage Day:

Initially known as Shaka Day, Heritage Day was introduced to commemorate the legendary Zulu King Shaka who played a significant role in unifying various Zulu clans into one cohesive nation. However, with the advent of a democratic South Africa in 1994, the day was renamed Heritage Day to promote a broader and more inclusive celebration of the nation’s diverse cultural heritage.

Celebrations in Various Institutions:

Heritage Day is celebrated in numerous ways throughout South Africa, with schools, families, workplaces, and religious institutions all participating. In schools, students and teachers dress in traditional attire, and activities such as cultural performances, food fairs, and storytelling sessions are organized to educate learners about different cultural backgrounds. Families gather to share traditional meals, pass down stories, and engage in cultural activities. Workplaces often host events that encourage employees to showcase their diverse backgrounds, while churches and other religious institutions use the day as an opportunity to emphasize the importance of tolerance and acceptance.

Promoting Unity and Closing Gaps:

The celebration of Heritage Day has played a vital role in fostering unity and bridging the divides of the past. By appreciating and acknowledging the various cultures and traditions, South Africans learn to respect and accept one another, ultimately creating a more harmonious society. The public holiday serves as a platform to engage in conversations about the nation’s history, allowing for a better understanding of the diverse experiences that have shaped South Africa.

Enforcing the South African Constitution:

Heritage Day also reinforces the principles enshrined in the South African Constitution, which guarantees cultural and linguistic rights to all citizens. By celebrating and embracing the diverse cultures, South Africans put into practice the values of equality, dignity, and freedom as envisioned by the Constitution.

Conclusion:

In this essay, we have explored the history and significance of Heritage Day, its transformation from Shaka Day, and how it is celebrated across various institutions in South Africa. We have also discussed how the celebration of this day fosters unity and enforces the principles of the South African Constitution. Heritage Day serves as a reminder that our differences make us stronger, and that through understanding and embracing our diverse backgrounds, we can build a more inclusive and united South Africa.

More Resources

Below are more previous resources you can download in pdf format:

Looking for something specific?

Leave a comment.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You May Also Like

The Social and Economic Impact and Changes Brought about by the Natives Land Act of 1913

History Grade 10 Source-Based Questions and Answers for 2020

How South African lived Before 1913

Reasons Why the District Six Museum is so Famous?

Heritage Day Essay Grade 10

Heritage Day, also known as National Braai Day, is a vibrant celebration of South Africa’s rich canvas of cultures, traditions, and histories. But for me as a Grade 10 learner, it can also mean fun time!

This essay guide will equip you to conquer that Heritage Day essay and impress your teacher.

How to answer “Heritage Day Essay” correctly for Grade 10?

Let us look at the magic term: Essay . When a question asks a student to write an “Heritage day essay,” they (students) are expected to provide a structured and well-organised piece of writing that presents and supports a main idea or a position.

The essay should have an introduction that introduces the topic and states the position or a side of the writer, body paragraphs that support the thesis or position with evidence and examples based on their country of South Africa, and a conclusion that summarises the main points and restates the position (good/bad).

Marks Breakdown

| Section | Marks | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | 10 | Clearly state the significance of Heritage Day and introduce your main points. |

| Body Paragraphs (2-3) | 25 (each) | Discuss different aspects of (e.g., food, music, languages) and their importance. Use specific examples and historical context. |

| Conclusion | 10 | Summarise the key points and emphasise the importance of celebrating heritage. |

| Language & Style | 10 | Use clear, concise, and grammatically correct language. Maintain a formal tone. |

Total: 55 Marks

The Topic for Heritage Day Essay for Grade 10

The red text is my handwritten answer.

I will take my essay and based it to heritage day food.

My Title: A Rainbow on Our Plates on the South Africa’s Food Heritage day ✓

Sample Short Essay (200 words)

Heritage Day in South Africa, the 24th of September, is a day full of life, colours, tunes, and most importantly, delicious food! It is a day when we celebrate the variety of flavours that represent our country’s rich mix of cultures. From the spicy curries made by Durban’s Indian community to the slow-cooked potjiekos of the Dutch settlers’ descendants and to the delicious Mopani worms, every meal has its own tale. ✓

Let’s talk about the braai – it’s the heart of any South African party. It started with the grilling traditions of the Khoisan people and was later picked up by European settlers. Now, the braai brings everyone together, no matter their background, around tasty boerewors and juicy steaks. It’s more than just cooking; it’s a time for joy, a celebration of life, and a way to remember our shared past. ✓

The original people of South Africa have also influenced our food. Samp, a type of maize porridge, has been a main food for ages, and koeksisters – sweet, syrupy pastries – are loved all over. These foods fill us up and also link us to our land and the cleverness of our forebears. ✓

Heritage Day is about more than just enjoying a good braai. It’s a time to value the different food traditions that have helped shape our nation. When we share meals with friends and family from various cultures, we get to know more about them, and together, we build a South Africa that welcomes everyone. ✓

Remember: This is just a sample, adjust the length and content according to your specific essay requirements.

Tips to Score Big:

- Go beyond the braai: Explore lesser-known aspects of heritage like traditional crafts, music, or languages.

- Show, don’t tell: Instead of just stating facts, use vivid descriptions and historical context to bring your essay to life.

- Source it right: Include in-text citations if required, and provide a reference list at the end.

- Proofread like a pro: Typos and grammatical errors can cost you marks. Double-check your work before submission.

By following these tips and understanding the marking scheme, you’ll be well on your way to writing a stellar Heritage Day essay that celebrates the vibrant tapestry of South Africa.

Shama Nathoo

Related articles.

Life Orientation Project Grade 12 Democracy And Human Rights Memo

Black power movement essay memorandum.

HISTORY Gr. 10 T1 W7: The Heritage Research Assignment: Theory - the nature of heritage and debates around it

This term will now focus on The Heritage Research Assignment: Theory. This week will focus on the nature of heritage and debates around it.

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

History Grade 10 Sba Tasks 2020

Total Page: 16

File Type: pdf , Size: 1020Kb

- Abstract and Figures

- Public Full-text

HISTORY GRADE 10 SBA TASKS 2020

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. GRADE 10 PROGRAMME OF ASSESSMENT 3

2. REPORTING AND RECORDING SBA MARKS 5

3. MODERATION OF SBA 7

4. DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 8-10

5. GRADE 10 FRAMEWORK

6. EXAMINATION GUIDELINES

7. ASSESSMENT METHOD FOR SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS

8. ASSESSMENT OF ESSAYS

9. SBA TASK 1 (SOURCE-BASED AND /OR ESSAY TASK)

10. SBA TASK 2 (CONTROLLED TEST 1 (to be requested to the DSA in term1)

11. SBA TASKS 3 – HERITAGE INVESTIGATION

12. SBA TASK 5 (SOURCE – BASED AND /OR ESSAY TASK)

13. SBA TASK 6 (to be requested from the DSA in term 3)

14. LEARNER DECLARATION

15. TEMPLATE FOR PRE-MODERATION TOOL

16. SCHOOL MODERATION TOOL

1. GRADE 10 PROGRAMME OF ASSESSMENT FOR HISTORY

In Grade 10, the Programme of Assessment consists of tasks undertaken during the school year and counts 25% of the final Grade 10 mark. The other 75% is made up of end of the year examination. The learner SBA portfolio is concerned with the 25% internal assessment of tasks.

NUMBER AND FORMS OF ASSESSMENT REQUIRED FOR THE PROGRAMME OF ASSESSMENT (SBA) FOR HISTORY GRADE 10

The Programme of Assessment for History comprises seven tasks which are internally assessed. The following table presents the annual assessment plan for Grade 10.

TABLE 1: THE GRADE 10 ANNUAL ASSESSMENT PLAN TERM 1 TERM 2 TERM 3 TERM 4

2 tasks 2 tasks 2 tasks

Source-Based OR Heritage investigation Source-based OR essay End-of year essay task. (50 marks) 20% task. examination.

(50 marks each) (50 marks for each task (150 marks ) 10% ) 10% Midyear examination Standardised test Standardised test which which includes a ( 100 marks ) 20% includes a source- based source-based and an essay question. question and an (100 marks) 20% essay. (100 marks) 20% 25% of total year mark = 100 marks 75% of total exam mark = 150 marks

From the table it is clear that the Programme of Assessment for History in Grade 10 comprises seven tasks which are internally assessed. Of the seven tasks, two are examinations and two are tests. The remaining three tasks comprise;

• Heritage Investigation task – (Uncontrolled conditions) • Two source based and essays writing tasks ( controlled conditions)

The following table illustrates and enhances this understanding further.

TABLE 2: THE SEVEN ASSESSMENT TASKS

PROGRAMME OF ASSESSMENT

REQUIREMENTS TERM TERM TERM TERM

Two (2) Standardised tests written under controlled conditions 1 1

Source-based or essay: under controlled conditions. 1

One investigation research 1 project : Heritage project (Compulsory)

Source-based or essay task 1 OR essay under controlled conditions.

MID-YEAR EXAMINATION 1

END-OF YEAR 1 EXAMINATION

The weightings of the assessment tasks for Grade 10 as follows

TABLE 3: THE WEIGHTINGS OF THE ASSESSMENT TASKS

ASSESSMENT ACTIVITY REDUCED MARK Midyear: 100 reduced to 20 TWO hours paper.

Two Standardised tests under controlled conditions 2 x 20 reduced to…

Heritage investigation 20

Source-based or essay: under controlled conditions. 10

Total for assessment tasks undertaken during the year 100

End-of-year examination: 150 75

………..( 1 Paper out of 150)

One three hour paper.

2. REPORTING AND RECORDING ON THE PROGRAMME OF ASSESSMENT (SBA)

The marks achieved in each assessment task in the formal Programme of Assessment must be recorded and included in formal reports to parents and School Management Teams. These marks will be submitted as the internal school based assessment (SBA) mark.

NB! As per NPPPPR of NCS, we record in marks, but we report in percentages.

The Programme of Assessment should be recorded in the teacher’s SBA file of assessment. The following should be included in the teacher’s SBA file:

• A contents page; • The formal Programme of Assessment; 5

• The requirements of each of the assessment tasks; • The tools used for assessment for each task; and • Working mark sheets for each class.

Teachers must report regularly and timeously to learners and parents on the progress of learners. Schools will determine the reporting mechanism but it could include written reports, parent-teacher interviews and parents meeting. Schools are required to provide written reports to parents once per term on the Programme of Assessment using a formal reporting tool. This report must indicate the percentage achieved per subject and include the following seven-point scale.

RATING RATING MARKS CODE %

7 Outstanding achievement 80 – 100

6 Meritorious achievement 70 –79

5 Substantial achievement 60 – 69

4 Adequate achievement 50 – 59

3 Moderate achievement 40 – 49

2 Elementary achievement 30 – 39

1 Not achieved 0 – 29

3. MODERATION OF THE ASSESSMENT TASKS IN THE PROGRAMME OF

All schools should have an internal assessment moderation policy in place, which has guidelines for the internal moderation of all significant pieces of assessment. There should also be scheduled dates for the internal moderation of teachers’ SBA file and evidence of learner performance.

The subject head and the School Management Team are responsible for drawing up the moderation plan and for ensuring that school-based moderation happens on a regular basis.

The teacher SBA file required for moderation for promotion requirements should include:

• Planning (School moderation management plan) • Forms of moderation Pre moderation Post moderation • Copies of tasks, tests and exams administered • Assessment criteria and marking guidelines for the above • Working Mark sheets • Diagnostic and statistical analysis • Attendance report

Moderation of the assessment tasks should take place at the three levels tabulated below.

LEVEL MODERATION REQUIREMENTS

School The Programme of Assessment should be submitted to the subject head and School Management Team before the start of the academic year for moderation purposes.

Each task which is to be used as part of the Programme of Assessment should be submitted to the subject head for moderation before learners attempt the task.

Teacher SBA files and evidence of learner performance should be moderated by the head of the subject or her/his delegate before moderation at a cluster/district level.

District/ region Teacher SBA files and a sample of evidence of learner performance must be moderated during the first three terms.

Provincial/ Teacher SBA files and a sample of evidence of learner performance National must be moderated once a year.

4. DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS

HISTORY DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS OF TESTS and EXAMS

NAME OF TASK TERM SCHOOL

Total number

80% 70% 79% 60% 69% 50% 59% 40% 49% 30% 39% 29%

Grade wrote pass Fail average

LEARNER PERFORMANCE IN SPECIFIC HISTORICAL SKILLS PER GRADE

NB: The educator should indicate how the learners have performed with regards to the skill and the cognitive level that is assessed.

COGNITIVE HISTORICAL LEARNER RECOMMENDATIONS/REMEDIAL LEVELS SKILLS PERFORMANCE FOR IMPROVEMENT OF THE SKILL (Indicate if few or most learners were competent or not in the skill/question) LEVEL 1 Extract information from sources Selection and organisation of relevant information from the source Define historical concepts LEVEL 2 Interpretation of evidence from sources Explain information gathered from sources Analyse evidence from sources

Explain concepts in

context LEVEL 3 Interpret and evaluate evidence from sources Engage with sources to determine its usefulness, reliability, bias and limitations Compare and contrast interpretations and perspectives presented in sources and draw independent conclusions. LEVEL 3 Paragraph question: Usage of sources and own knowledge. No copying of sources. Making reference to sources LEVEL 3 Essay question: Stance taken in the introduction PEEL used appropriately. LOA adhered to. No ne content in the conclusion

HISTORY QUESTION PAPER ANALYSIS Remedial measures / suggestions for improvement (State what is going to be done to remedy weaknesses, common errors, misconceptions, etc)

______Subject teacher Signature Date

______HOD Signature Date

SCHOOL STAMP

5. GRADE 10 EXAMINATION FRAMEWORK:

• One 2 hrs paper • The question paper will consist of FOUR questions • TWO questions to be answered • All questions will be set out of 50 • Total=100

GRADE 10 OCT/NOV EXAMINATION: Total= 150

• One 3 hours paper • The question paper will consist of SIX questions • THREE questions to be answered • All questions will be set out of 50

6. GRADE 10 EXAMINATION GUIDELINE

The prescribed topics will be assessed as follows:

JUNE COMMON EXAMINATIONS SECTION A: SOURCE-BASED SECTION B: ESSAY QUESTIONS QUESTIONS ( One question per topic will be set) ( One question per topic will be set)

1.THE WORLD AROUND 1600 1. THE WORLD AROUND 1600

Question focus: Question focus: European societies: Songhai: An African empire in the • Feudal societies 15th and 16th centuries: • Renaissance • Government and society • Change in feudalism • Travel and trade • Learning and culture

2. EUROPEAN EXPANSION AND 2. EUROPEAN EXPANSION AND CONQUEST CONQUEST • Africa: The process of Dutch • The impact of slave trading conquest and on societies. • Colonialism at the Cape.

3. THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 3. THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

Question focus: Question focus; • The social causes of the revolution Causes of the French Revolution • The course of the revolution • Economic causes • Political causes

NOVEMBER COMMON EXAMINATIONS

SECTION A: SOURCE-BASED SECTION B: ESSAY QUESTIONS QUESTIONS ( One question per topic will be set) (One question per topic will be set)

1.TRANSFORMATIONS IN SOUTHERN 1. TRANSFORMATIONS IN AFRICA AFTER 1750 SOUTHERN AFRICA AFTER 1750

Question focus: Question focus: The political revolution 1820 - 1835 The emergence of the Sotho • The rise of the Zulu kingdom kingdom • The consolidation of the Zulu • The Sotho kingdom under kingdom Moshoeshoe • His relationship with his neighbours 2. COLONIAL EXPANSION 1750 2. COLONIAL EXPANSION 1750

Question focus: Question focus: Britain at the Cape Cooperation and conflict on the • Changing labour patterns Highveld • Boer response to the British control • The Boer Republic north of the • Xhosa response to cooperation and Vaal conflict • The Boer Republic between the Orange and Vaal

3.THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR AND 3. THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR UNION AND UNION Question focus: Question focus: The South African War 1899 - 1902 The Native Land Act of 1913 • The role and experience of woman in • The social and economic the war impact of the Land Act • The role and experience of the black • Reactions to the Land Act South Africans in the war • The foundation of the system of • The experience of Afrikaners in the apartheid British concentration camps

7. SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS ASSESSMENT

7.1 The following cognitive levels were used to develop source-based questions:

Cognitive Weighting of Historical skills Levels questions • Extract evidence from sources 40% LEVEL 1 • Selection and organisation of relevant information from sources (20) • Define historical concepts/terms • Interpretation of evidence from sources 40% LEVEL 2 • Explain information gathered from sources (20) • Analyse evidence from sources • Interpret and evaluate evidence from sources • Engage with sources to determine its usefulness, reliability, bias and limitations 20% LEVEL 3 • Compare and contrast interpretations and (10) perspectives presented in sources and draw independent conclusions

7.2 The information below indicates how source-based questions are assessed: • In the marking of source-based questions, credit needs to be given to any other valid and relevant viewpoints, arguments, evidence or examples. • In the allocation of marks, emphasis should be placed on how the requirements of the question have been addressed. • In the marking guideline, the requirements of the question (skills that need to be addressed) as well as the level of the question are indicated in italics. • When assessing open-ended source-based questions, learners should be credited for any other relevant answers. • Learners are expected to take a stance when answering ‘to what extent’ questions in order for any marks to be awarded.

7.3 Assessment procedures for source-based questions • Use a tick (✓) for each correct answer. • Pay attention to the mark scheme e.g. (2 x 2) which translates to two reasons and is given two marks each (✓✓✓✓); (1 x 2) which translates to one reason and is given two marks (✓✓). • If a question carries 4 marks then indicate by placing 4 ticks (✓✓✓✓).

Paragraph question Paragraphs are to be assessed globally (holistically). Both the content and structure of the paragraph must be taken into account when awarding a mark. The following steps must be used when assessing a response to a paragraph question: • Read the paragraph and place a bullet (.) at each point within the text where the candidate has used relevant evidence to address the question. • Re-read the paragraph to evaluate the extent to which the candidate has been able to use relevant evidence to write a paragraph.

• At the end of the paragraph indicate the ticks (√) that the candidate has been awarded for the paragraph; as well as the level (1,2, or 3) as indicated in the holistic rubric and a brief comment e.g. ______. ______. ______. ______Level 2 √√√√√

Used mostly relevant evidence to write a basic paragraph • Count all the ticks for the source-based question and then write the mark on the right- hand bottom margin, e.g. 32 50 • Ensure that the total mark is transferred accurately to the front/back cover of the answer script.

8. ESSAY QUESTIONS

8.1 The essay questions require candidates to: • Be able to structure their argument in a logical and coherent manner. They need to select, organise and connect the relevant information so that they are able to present a reasonable sequence of facts or an effective argument to answer the question posed. It is essential that an essay has an introduction, a coherent and balanced body of evidence and a conclusion.

8.2 Marking of essay questions • Markers must be aware that the content of the answer will be guided by the textbooks in use at the particular centre. • Candidates may have any other relevant introduction and/or conclusion than those included in a specific essay marking guideline for a specific essay.

8.3 Global assessment of the essay The essay will be assessed holistically (globally). This approach requires the teacher to assess the essay as a whole, rather than assessing the main points of the essay separately. This approach encourages the learner to write an original argument by using relevant evidence to support the line of argument. The learner will not be required to simply regurgitate content (facts) in order to achieve a level 7 (high mark). This approach discourages learners from preparing essays and reproducing them without taking the specific requirements of the question into account. Holistic marking of the essay credits learners' opinions that are supported by evidence. Holistic assessment, unlike content- based marking, does not penalise language inadequacies as the emphasis is on the following: • The learner's interpretation of the question • The appropriate selection of factual evidence (relevant content selection) • The construction of an argument (planned, structured and has an independent line of argument)

8.4 Assessment procedures of the essay

8.4.1 Keep the synopsis in mind when assessing the essay.

8.4.2 During the reading of the essay, ticks need to be awarded for a relevant introduction (which is indicated by a bullet in the marking guideline), the main aspects/body of the essay that sustains/defends the line of argument (which is indicated by bullets in the marking guideline) and a relevant conclusion (which is indicated by a bullet in the marking guideline). For example in an essay where there are five (5) main points there could be about seven (7) ticks.

8.4.3 Keep the PEEL structure in mind in assessing an essay.

P Point: The candidate introduces the essay by taking a line of argument/making a major point. Each paragraph should include a point that sustains the major point (line of argument) that was made in the introduction. E Explanation: The candidate should explain in more detail what the main point is about and how it relates to the question posed (line of argument). E Example: Candidates should answer the question by selecting content that is relevant to the line of argument. Relevant examples should be given to sustain the line of argument. L Link: Candidates should ensure that the line of argument is sustained throughout and is written coherently.

8.4.4 The following symbols MUST be used when assessing an essay:

• Introduction, main aspects and conclusion not properly contextualised

^ • Wrong statement ______

• Irrelevant statement | | |

• Repetition R

• Analysis A√

• Interpretation I√

• Line of Argument LOA

8.5 The matrix

8.5.1 Using the matrix in the marking of essays

In the marking of essays, the criteria as provided in the matrix should be used. When assessing the essay note both the content and presentation. At the point of intersection of the content and presentation based on the seven competency levels, a mark should be awarded.

(a) The first reading of the essay will be to determine to what extent the main aspects have been covered and to allocate the content level (on the matrix).

(b) The second reading of the essay will relate to the level (on the matrix) of presentation.

C LEVEL 4 P LEVEL 3

(c) Allocate an overall mark with the use of the matrix.

C LEVEL 4 }26– P LEVEL 3 27

MARKING MATRIX FOR ESSAY: TOTAL: 50

LEVEL 7 LEVEL 6 LEVEL 5 LEVEL 4 LEVEL 3 LEVEL 2 LEVE L 1* PRESENTATION Very well Very well Well planned Planned and Shows some Attempts to Little or planned and planned and and constructed evidence of structure an no structured structured structured an a planned answer. attempt essay. Good essay. essay. argument. and Largely to synthesis of Developed a Attempts to Evidence constructed descriptive structure information. relevant line develop a used to argument. or some the Developed of argument. clear some extent Attempts to attempt at essay. an original, Evidence argument. to support sustain a line developing a CONTENT well- used to Conclusion the line of of argument. line of balanced defend the drawn from argument. Conclusions argument. and argument. the evidence Conclusions not clearly No attempt independent Attempts to to support reached supported by to draw a line of draw an the line of based on evidence. conclusion. argument independent argument. evidence. with the use conclusion of evidence, from the sustained, evidence to and support the defended the line of argument argument. throughout. Independent conclusion is drawn from evidence to support the line of argument.

LEVEL 7 Question has been fully answered. Content 47–50 43–46 selection fully relevant to line of argument. LEVEL 6 Question has been answered. Content selection 43–46 40–42 38–39 relevant to a line of argument. LEVEL 5 Question answered to a great extent. Content 38–39 36–37 34–35 30–33 28–29 adequately covered and relevant. LEVEL 4 Question recognisable in answer. Some omissions or 30–33 28–29 26–27 irrelevant content selection. LEVEL 3 Content selection does relate to the question, but does not answer it, or 26–27 24–25 20–23 does not always relate to the question. Omissions in coverage. LEVEL 2 14– Question inadequately 20–23 18–19 addressed. Sparse 17 content. LEVEL 1* Question inadequately addressed or not at all. 14–17 0–13 Inadequate or irrelevant content.

* Guidelines for allocating a mark for Level 1:

Question not addressed at all/totally irrelevant content; no attempt to structure the essay = 0 Question includes basic and generally irrelevant information; no attempt to structure the essay = 1–6 Question inadequately addressed and vague; little attempt to structure the essay = 7–13

Task 1: Source-based OR essay

QUESTION 1: WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF FEUDALISM ON EUROPE?

The source below is a description of the feudal system in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Feudalism was a hierarchical system of land use and patronage that dominated Europe between the ninth and 14th centuries. Under Feudalism, a monarch's kingdom was divided and subdivided into agricultural estates called manors. The nobles who controlled these manors oversaw agricultural production and swore loyalty to the king. Despite the social inequality it produced, Feudalism helped stabilize European society. But in the 14th century, Feudalism waned. The underlying reasons for this included warfare, disease and political change. And when feudalism finally came to an end, so too did the Middle Ages.

[From: https://classroom.synonym.com/caused-downfall-feudalism-16285.html .Acessed on 15 Febryary 2019.]

The following source focuses on the impact of the Plague on Europe.

The disease (the Plague or Black Death) existed in two varieties, one contracted by insect bite and another airborne. In both cases, victims rarely lasted more than three to four days between initial infection and death, a period of intense fever and vomiting during which their lymph nodes swelled uncontrollably and finally burst. The plague bacteria had lain dormant for hundreds of years before incubating again in the 1320s in the Gobi Desert of Asia, from which it spread quickly in all directions in the blood of fleas that travelled with rodent hosts. Following very precisely the medieval trade routes from China, through Central Asia and Turkey, the plague finally reached Italy in 1347 aboard a merchant ship whose crew had all already died or been infected by the time it reached port. Densely populated Europe, which had seen a recent growth in the population of its cities, was a tinderbox for the disease. The Black Death ravaged the continent for three years before it continued on into Russia, killing one-third to one-half of the entire population in ghastly (terrible) fashion. The plague killed indiscriminately – young and old, rich and poor – but especially in the cities and among groups who had close contact with the sick. Entire monasteries filled with friars were wiped out and Europe lost most of its doctors. In the countryside, whole villages were abandoned. The disease reached even the isolated outposts of Greenland and Iceland, leaving only wild cattle roaming free without any farmers, according to chroniclers who visited years later.

[From: https://www.livescience.com/2497-black-death-changed-world.htm. Accessed on 15 February 2019.]

The source below is a painting called The Triumph of Death by artist Pieter Breugel in 1562 was inspired by the Black Death.

The following source is an extract from Daily History explains how the Plague gave rise to the Renaissance.

In the aftermath of the Black Death, the economy of Italy benefited greatly from trade and thus some areas became industrialized such as Florence. In this city, there was a large class of weavers who wove cloth for home consumption and export. The wealth of Italy increased because of trade but it also changed people’s outlook, who gradually adopted a more rational approach to the world. Italian society had evolved very differently from the rest of Europe. Northern Italy in particular, was much more urbanised than the rest of Europe. Many of the largest cities in Europe were located in Northern Europe such as Florence and Milan. Urban societies are widely believed to be more dynamic than agrarian societies. In towns and cities' people come together and converse and debate. Urban societies are also more open to new ideas as immigrants and traders settled in them. The plazas and taverns of Florence and other cities were often filled with people, many of them outsiders discussing new ideas and exchanging copies of manuscripts. This was a milieu that was beneficial to creative and intellectual endeavours. [From: https://dailyhistory.org/. Accessed on 15 February 2019.]

SECTION A: SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS

1.1 Refer to Source 1A.

1.1.1. Explain the term feudalism. (1 x 2) (2)

1.1.2. What, according to the source, were the responsibilities of the nobles under the feudal system? (2 x 1)(2)

1.1.3. Comment on why it was said that feudalism created ‘social inequality’. (1 x 2)(2) 1.1.4. List THREE reasons for the decline of feudalism in the 14th century. (3 x 1)(3)

1.2 Refer to Source 1B.

1.2.1 In what area did the Plague originate? (1 x 1)(1) 1.2.2 How did the Plague reach Italy by 1357? (1 x 1)(1) 1.2.3 Explain why Europe was a ‘tinderbox’ for the disease. (1 x 2) (2)

1.2.4 Why, in your opinion, were friars and doctors some of the main casualties of the disease? (2 x 2) (4) 1.2.5 QUOTE evidence that shows the enormous destruction of the Plague. (1 x 2) (2) 1.2.6 Explain the usefulness of Source 1B to a historian researching the impact of the Plague on Europe. (2 x 2) (4)

1.3 Study Source 1C.

1.3.1 What message did the artist want to convey about the Plague? (1 x 2) (2)

1.3.2 Give TWO visual clues from the painting that indicate the level Of destruction of the Plague. (2 x 2) (4)

1.3.3 How does Source 1C support the ideas in Source 1B? Use evidence to support your answer. (2 x 2) (4)

1.4 Refer to Source 1D.

1.4.1 List THREE benefits of the Plague for Italy. (3 x 1) (3)

1.4.2 Using Source 1D and your own knowledge, explain why the Renaissance , rebirth of culture and thought, began in Italy (2x2) (4)

1.4.3 How was it possible for the people of Florence to ‘exchange copies of manuscripts’? (1 x 2) (2)

1.5 Using the relevant sources and your own knowledge, write a paragraph (80- 100 words) in which you discuss the impact of feudalism on Europe 8)

TOTAL [50] OR

SECTION B: ESSAYQUESTION

QUESTION 2: SONGHAI EMPIRE

Before its decline, the Songhai Empire was a powerful and prosperous state.

Critically discuss the reasons for Songhai power and prosperity until the 15th century. [50]

MEMORANDUM: GRADE 10 SBA TASK 1 TERM 1

QUESTION 1: THE WORLD AROUND 1600 1.1. QUESTION 1: WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF FEUDALISM ON EUROPE?

Refer to Source 1A. 1.1.1 [Explaining historical concepts from Source 1A – L1] A Feudal system – a social system in which the king gave land to the nobleman in return for their military support and peasants lived the land. (1x2) (2)

B Fief – a piece of land given by the king to the Lords and Nobles. (1x2) (2) 1.1.2 [Extract relevant evidence from Source 1A – L1] • Land was used as a means of payment • Only people who were close to the king such as the knights and nobles owned land as they had received it from the king as a form of payment for the protection and loyalty they provided the king. (Any 1) (1x1) (1) 1.1.3 [Explain information gathered from Source 1A – L1] • Land was a form of payment that made the feudal system to be successful. • Without land the feudal system was not going to be successful. • The king paid the knights and nobles with land and in return they gave him protection. • Land gave the first and estate power over the third estate. (2x2) (4)

1.1.4 [Explain and analyse information gathered from Source 1A – L2] • The first and second estate benefitted from the system. • They had the land and could get the third estate to work on their land and pay them taxes for occupying their land. • The third estate was disadvantaged they were heavily taxed. • They carried the burden of the first and second estate, which was too much for them. (2x2) (4)

1.2. Refer to source 1B

1.2.1 [Extract relevant evidence from Source 1B – L1] Three reasons for the decline of feudalism: • Warfare • Disease • Political change (3x1) (3)

1.2.2 [Extract relevant evidence from Source 1B – L1] Nobles were to: • Oversee agricultural production • Swear loyalty to the king (2x1) (2)

1.2.3 [Comment on the information gathered from Source 1B – L2] • Feudalism was strict with no mobility between classes. • The king and nobles were rich while the serfs struggled. (Use discretion) (2x2) (4)

1.3. Study Source 1C.

1.3.1. [Extract relevant evidence from Source 1C – L1] • Loyalty • Land (2x1) (2) 1.3.2. [Explain and analyse information gathered from Source 1C – L2] • In a feudal system the king is at top, the king gives land to the barons and the barons give land to the knights and the peasants work on the land. • The knights swore an oath to the barons and will fight for the king while barons will swear an allegiance to the king. • Any other relevant response. (2x2) (4) 1.3.3. [Explain and analyse information gathered from Source 1C – L2] Useful because : • The source provides a visual illustration of how the feudal system worked the king is on top and the peasant are at the bottom of this triangle. • It provides us written information on how the feudal system works by explaining how the knights are fighting for the king and the barons swear allegiance to the king. • Any other relevant response. (2x2) (4)

1.4. Refer to Source 1D

1.4.1. [Extract relevant evidence from Source 1D – L1] • Trade meant lead to the growth of towns • Demand for urban workers grew (2x1) (2) 1.4.2. [Explain and analyse information gathered from Source 1D – L2]

• The was labour shortage in the rural in the rural areas • Some people in the rural areas died due to the black death • Due to labour shortage it meant that power would be shifted as they had to treat the little labour that was still available to them with care or else they were going to leave also. (Any 2) (2x2) (4)

1.4.3. [Explain and analyse information gathered from Source 1D – L2] • Europe became peaceful • The king did not have a need to call the nobles to fight for him. • Due to the lack of war it meant that the nobles were weakened and their power was consolidated back to the king. (Any 2) (2x2) (4) [10]

1.5 [Interpretation, evaluation and synthesis of evidence from relevant sources – L3] Candidates could include the following aspects in their response: • The system of feudalism. • Peasants had no rights. • Trade developed – new economic and political system developed in Europe. • Removed social and economic barriers of feudalism • Workers were free to work for themselves • This inspired new ideas in Art, writers and sculptors. • Trading goods improved as the world opened up • Any other relevant response (8)

Use the following rubric to allocate marks:

• Uses evidence in an elementary manner e.g. shows no or little understanding of the Level 1 impact of feudalism on Europe. Marks • Uses evidence partially or cannot write a 0-2 paragraph.

• Evidence is mostly relevant and relates to the topic e.g. shows some understanding of the impact of feudalism on Europe. Level 2 Marks • Uses evidence in a basic manner to write a 3-5 paragraph.

• Uses relevant evidence e.g. demonstrates a thorough understanding of the impact of

feudalism on Europe. • Uses evidence very effectively in an Marks

organised paragraph that shows an 6-8 Level 3 understanding of the topic.

QUESTION 2: ESSAY SONGHAI EMPIRE

Synopsis: Learner must discuss the factors leading to the power and prosperity of the Songhai Empire. Issues such as leadership, trade, learning and culture.

Introduction: Learner must give brief examples of the reasons for Songhai’s power and prosperity during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Main points: • Strategic position of Songhai in West Africa • Role of Sonni Ali and Askia Mohammed • Reorganisation of the army • Establishment of provinces with own governors • Religious tolerance under Ali • New taxation system • Encouragement of learning: Timbuktu • Trade: gold, salt and travel: camel caravans • Any other relevant point

Conclusion: Learner must tie up argument reaffirming the reasons for Songhai’s power and prosperity. [50]

TERM 2: HERITAGE ASSIGNMENT

Grade 10 SBA Task 3

This Heritage assignment consist of 03 pages and a rubric

HOW HAS SOUTH AFRICA CHOSEN TO CELEBRATE THEIR HERITAGE?

Historical context

Since the dawn of democracy in 1994 the South African government has chosen to remember the past by celebrating unity in diversity. What has been the painful past has been changed to a form of celebration, thus bringing in reconciliation and unity in South Africa.

In the context of the above statement, do a research on this public holiday:

HERITAGE DAY

1. The scope of Research: • The brief history linked to the day. • Explain the changes that were made to this public holiday. • Explain how the day is celebrated in schools, families, work places and other institutions like churches etc. • How does the celebration of the holiday bring unity and close the gaps of the past? • Explain how the celebration of the day enforces the application of the constitution of South Africa. • Visual sources should be used within the discussion to reinforce and explain the written information. 2. Instructions for research 1. The learners should have THREE weeks to gather evidence and contextualise it to the research topic. 2. The learners’ response should be in the form of an essay with introduction, body and conclusion. 3. No subheadings, point form and cut and paste in the content. 4. Avoid putting visual sources on separate and isolated page. Visual sources should be given captions that relate to the discussion in the research discussion. 5. The length of Heritage assignment should be about SEVEN (7) pages long: • Cover page • Table of contents page • 3 to 4 pages of both written and visual content • Bibliography page • Rubric page ( provided by the teacher) 6. A mere rewriting of evidence as answers will disadvantage learners. 7. Credit will be given for analysis and interpretation of evidence according to the topic. 8. Plagiarism will be penalised 9. Write an essay in your own words and acknowledge all quotations and sources in the bibliography. 10. Quote from article/ book using in-text reference Example: “Heritage is a nation’s historic buildings, monuments and past events which are regarded as worthy of preservation” (Oxford dictionary, 1996:411) Own words with in -text reference Example: Heritage is part of our past that we choose to commemorate ( Bottaro J, 2011:198) 11. Sources of reference: Internet, media centres and public libraries. 12. Bibliography must be done alphabetically according to the author’s name or the website. 13. Examples of bibliography: 31

• The 1805 Constitution of Haiti: http/ www.webster.edu [accessed on 07 June 2015] • McKay,J.1988, A History Of The World Societies (Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston)

SBA TASK 3. GRADE 10. TERM 2 HERITAGE RUBRIC: TOTAL MARKS-50

SURNAME AND NAME: ______

NAME OF THE SCHOOL: ______

CRITERIA Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Level 4 Marks Not achieved Partially achieved Achieved Excellent Explain the changes Shows no or little Shows a partial Shows an Shows an to the Heritage day understanding of understanding of adequate excellent and the brief changes to the changes to the understanding understanding background of the day, the day, the of changes to of changes to day. background of the background of the the day, the the day, the heritage day and heritage day and background of background of how it is how it is the heritage day the heritage celebrated in celebrated in and how it is day and how it South Africa. South Africa. celebrated in is celebrated in (0-3) (4-6) South Africa. South Africa. . (7-9) (10-12) Presentation, logic Information has no Information has Information Information and coherence of or little logic and some logic and shows logic and presented in an collected information. coherence. coherence. coherent flow of excellent, ideas. logical, (0-2) (3-4) coherent (5-6) manner that shows insight. (7-8) Understanding of Has shown little or Has shown partial Shows Shows an heritage issues and no understanding understanding of adequate excellent whether this change of the heritage the heritage understanding understanding issues and impact issues and impact of the heritage of the heritage has built national of change in of change in issues and issues and unity and identity in South Africa. South Africa. impact of impact of South Africa. change in South change in (0-2) (3-4) Africa. South Africa. (5-6) (7-8) Ability to select Shows little or no Basic information Selected and Excellent relevant information little ability to and visuals applied relevant selection and and visual sources. select and apply selection and information and application of relevant application. relevant visual information and Ability to use and information and sources visual sources. apply the selected use of illustrations (7-8) information and (0-1) (2-4) (5-6) visual sources. Structure of the No or basic essay Attempt at Essay Excellent essay, referencing, structure and structuring the adequately structure with bibliography and acknowledgement essay and little structured and sources plagiarism of sources used. acknowledgement sources used acknowledged Plagiarised of sources used. acknowledged. in an excellent content Some plagiarism No plagiarism in manner. (0-2) in content. content. (7- 8) (3-4) (5-6) How the Shows no or little Shows some Shows relevant Excellent celebration of the understanding of understanding on understanding understanding how the day how the day on how the day on how the day day enforces the enforces the enforces the enforces the enforces the application of the constitution of constitution South constitution constitution constitution of the South Africa. Africa South Africa. South Africa. South Africa. (0-1) (2-3) (4-5) (6)

Term 3 SBA TASK 5

Source-based or essay ADDENDUM

QUESTION 1:HOW DID THE ZULU KINGDOM EMERGE UNDER SHAKA ?

Source 1A: The following source focuses on the rise of the Zulu Kingdom under Shaka.

In 1819 the Zulus attacked the Ndwandwe, destroyed Zwide’s capital and broke up his kingdom. It is now believed that internal divisions also helped to break up the Ndwandwe kingdom. There was disagreement among the Ndwandwe about whether it was better to fight the Zulu or they should focus instead on trading with the north. Some members of the Zwide’s ruling group disagreed with his warlike ideas and moved away to the Delagoa Bay……….

Shaka used the amabutho to expand his power and control by sending them on raids into neighbouring chiefdoms. Older versions of history used to claim that these raids were violent and bloodthirsty, and that Shaka controlled over 50 000 armed men who killed almost a million people. However, historians now believe that is not accurate, and that it was not simply force and warfare that led to the rise of the Zulu state under Shaka. They think that peaceful diplomacy played an equally important role in persuading other chiefdoms to join the Zulu state. Although Shaka tried to break up or drive away chiefdoms that he thought could threaten his own power, he allowed others to remain as they were, provided they did not threaten him. He offered them protection in return. [From In Search Of History Grade 10 page 112] Source 1B: The source below describes the structure of the Zulu Kingdom.

Source 1B: The source below describes the structure of the Zulu Kingdom.

The Zulu state under Shaka certainly became more militarised. Shaka also created amabutho of young women and controlled marriages between them and the male amabutho soldiers. Zulu society under Shaka consisted of three levels. At the top was the king and an aristocracy or inkundla consisting of Zulu royal family and leaders of chiefdoms that had become part of the Zulu state. The second level was the population of the central parts of the kingdom, making up the amabutho and

their families. At the bottom were people of low status who were not members of amabutho and who did the daily tasks of work, such as herding the cattle. [From In Search Of History Grade 10 page 112]

Source 1C: The following photograph shows how trade helped the Zulu Kingdom to rise.

[From South Africa History Online]

Source 1D: The extract below shows how guns helped Shaka to conquer other Kingdoms.

Trade also helped the Zulu kingdom to become powerful. They traded in ivory and cattle with the Portuguese at Delagoa Bay in return for manufactured goods like cloth and guns. After 1824 they also traded with the small settlement of British traders at Port Natal (later to be called Durban). The Zulu bought manufactured goods and firearms from them.

It may have been because Shaka had access to guns and help from the Port Natal traders that he attacked the Ndwandwe kingdom again in 1826. The Ndwandwe was now ruled by Zwide’s son Sikhunyana. Several of the Port Natal traders joined Shaka’s forces in the attack. The Ndwandwe were defeated at the Izindolwane hills, and many were killed and their cattle seized. As a result of this defeat, the Ndwandwe kingdom collapsed. Many Ndwandwe joined the Zulu and promised loyalty to Shaka, while others fled. [From In Search Of History Grade 10 page 113]

QUESTION 1: HOW DID THE ZULU KINGDOM EMERGE UNDER SHAKA?

Study sources 1A, 1B, 1C and 1D and answer the questions that follow.

1.1 Refer to source 1A.

1.1.1 How, according to the source did Shaka expand his power? (1 x 2) (2) 1.1.2 Quote TWO words from the source that suggests that Shaka used force to gain power. (2 x 1) (2) 1.1.3 What do you understand by the term diplomacy? (1 x 2) (2) 1.1.4 What evidence in the source suggests that Shaka did not only use force to grow his Kingdom. (1 x 2) (2) 1.1.5 Comment on the usefulness of the source to a historian studying the rise of Shaka. (2 x 2) (4)

1.2 Study source 1B.

1.2.1 Explain why Shaka favoured young women as ambutho. (1 x 2) (2) 1.2.2 How, according to the source was the Zulu society divided under Shaka’s rule? (3 x 1) (3) 1.2.3 Explain the significance of the militarisation to the rise of the Zulu Kingdom. (2 x 2) (4)

1.3 Study source 1C

1.3.1 What messages is conveyed in the picture regarding the Zulu Kingdom? (2 x 2) (4) 1.3.2 Using the information in the source and your own knowledge, explain how trade helped the Zulu kingdom to be powerful. (2 x 2) (4)

1.4 Refer to source 1D

1.4.1 Name the two countries that traded with Zulus. (2 x 1) (2) 1.4.2 What according source helped Shaka to attack the Ndwandwe kingdom? (1 x 2) (2) 1.4.3 Where according to the source was the Ndwandwe kingdom defeated by the Zulus? (1 x 1) (1) 1.4.4 Comment on why the Ndwandwes promised loyalty to Shaka? (2 x 2) (4)

1.5 Compare source 1C and 1D. Explain how information in 1D supports evidence in source 1C with regarding the trade with foreigners. (1 x 2) (2)

1.6 Using the information in the relevant sources and your own knowledge, write a paragraph of about EIGHT lines (80 words) explaining how the Zulu kingdom emerge under Shaka. (8)

QUESTION 2:ESSAY QUESTION

Critically discuss the emergence and consolidation of the Basotho kingdom under Moshoeshoe. [50]

1.1 SOURCE 1A

1.1.1 [Extraction of evidence from source 1A – L1]

• He used amabutho to attack his enemies. (1 x 2) (2)

1.1.2 [Extraction of evidence from source 1A – L1]

• violent • bloodthirsty (2 x 1) (2)

1.1.3 [Definition of historical concept from source 1A L2]

• Diplomacy: making peaceful agreement. • Any other relevant answer. (2 x 2) (4)

1.1.4 [Extraction of evidence from source 1A – L1]

• “… peaceful diplomacy played an equally important role in Persuading other chiefdoms to join the Zulu state” (1 x 2) (2)

1.1.5 [Ascertaining the usefulness of source 1A – L3]

Useful: • Peaceful diplomacy played an important role. • He used amabutho • Any other relevant answer (2 x 2) (4)

1.2 Source 1B

1.2.1 [Analysis of evidence from source 1B - L1]

• Young women don’t have family commitments. • Any other relevant answer (1 x 2) (2)

1.2.2 [Analysis of evidence from source 1B - L1]

• top level: king and inkundla consisting of Zulu royal family and leaders of chiefdoms • second level: the population of the central parts of the kingdom making up amabutho and their families. • bottom level: people of low status who were not members of amabutho. (3 x 1) (3)

1.2.3 [Analysis of evidence from source 1B - L1]

• helped the Zulu Kingdom to be strong • also helped them to be more feared • any other relevant answer (2 x 2) (4) 1.3 Source 1C

1.3.1 [Interpretation of evidence in source 1C – L2 ]

• Trading between the Zulus and foreigners. • They made contact with the foreigners. • Any other relevant answer. (2 x 2) (4)

1.3.2 [Interpretation of evidence in source 1C – L2 ]

• Helped the Zulus to have guns to protect themselves. • to protect themselves (2 x 2) (4)

1.4 Source 1D

1.4.1 [Extraction of evidence from source 1D – L1]

• Portugal and Britain (2 x 1) (2)

1.4.2 [Extraction of evidence from source 1D – L1]

• the guns. (1 x 2) (2)

1.4.3 [Extraction of evidence from source 1D – L1]

• Izindolwane Hills (1 x 2) (2)

1.4.4 [Interpretation of evidence in source 1 – L2 ]

• Wanted protection. • They feared Shaka. • Any other relevant answer. (2 x 2) (4)

1.5 [Comparison of evidence in source 1C and 1D - L3]

• Both sources explain about the Zulu trading. • Source 1C show the Zulu man holding an ivory with some other Men and in 1D it is explained that the Zulu were trading with ivory in exchange for guns and cloth. (2 x 2) (4)

1.5 [Interpretation, evaluation and synthesis of evidence from relevant sources - L3] • Shaka used amabutho to expand his power (Source 1A) • Shaka persuaded other chiefdoms to join the Zulu state (Source 1A) • He was also trade with other counties for guns. (Source 1D)

Use the following rubric to allocate a mark: 39

• Uses evidence in an elementary manner e.g. shows no or little • understanding of the rise and consolidation of the Zulu Kingdom. Uses evidence partially to report on topic or cannot report on topic.

MARKS LEVEL 1 0–2

• Evidence is mostly relevant and relates to a great extent to the topic e.g. • shows some understanding of the rise and consolidation of the Zulu

Kingdom. MARKS LEVEL 2 Uses evidence in a very basic manner. 3–5

• Uses relevant evidence e.g. demonstrates a thorough understanding • the rise and consolidation of the Zulu Kingdom. Uses evidence very effectively in an organised paragraph that shows an MARKS LEVEL 3 understanding of the topic. 6–8

QUESTION 2: ESSAY QUESTION

The emergence of the Basotho Kingdom under Moshoeshoe and his relationship with his neighbours.

[Plan, construct and discuss an argument based on evidence using analytical and interpretation skills]

SYNOPSIS Learners should indicate how the Basotho Kingdom emerged under Moshoeshoe.

MAIN ASPECTS Candidates should include the following aspects in their response:

Introduction: Learners must go about assessing the emergence of the Basotho Kingdom under Moshoeshoe

ELABORATION: Learners should include the following aspects in their response:

Critically discuss the emergence of the Basotho kingdom under Moshoeshoe and his relationship with his neighbours.

• The Caledon Valley was badly affected by Boer, Kora and Griqua Raiders. • Moshoeshoe of the Bamokotedi (Sotho-speaking) offered people protection and cattle in return for support. • They lived on a mountain, Thaba Bosiu, which was easy to defend. • At first Moshoeshoe raided other groups, especially the Tembu.

• Then he established god relationships with his neighbours. • Many refugees and whole chiefdoms joined him for protection. • He used the mafisa system, giving cattle in return for loyalty. • The Sotho kingdom was not a centralised states – smaller chiefdoms could run their own affairs. • Moshoeshoe could not confront more powerful states – he got Zulu support in return for gifts to Shaka. • He bought horses and guns from traders in the Cape Colony. • He welcomed missionaries to his kingdom. • He established good contact with colonial authorities in the Cape.

LEARNER DECLARATION FORM

SCHOOL :______

NAME OF LEARNER :______

EDUCATOR’S NAME ______

I hereby declare that all pieces of writing in this portfolio are my own, original work and that if I have made used of any sources, I have acknowledged this.

I agree that if it is determined by competent authorities that I have engaged in any fraudulent activities whatsoever in connection with my SBA mark then I shall forfeit completely the marks gained for this assessment.

CANDIDATES SIGNATURE DATE

EDUCATOR’S SIGNATURE DATE

14. SUGGESTED PRE- MODERATION TOOL

NAME OF THE SCHOOL: SUBJECT NAME OF EDUCATOR (S) GRADE NAME OF HOD DISTRICT DATES MARKS DURATION TASK DESCRIPTION CRITERIA FOR MODERATION YES NO REMARKS 1. SUBMISSION Was the question paper, addendum and memo submitted on time? 2.QUESTION PAPER 2.1 Is there a cover page with relevant information? 2.2 Are the instructions clear? 2.3 Are the pages numbered correctly? 2.4 Is the key question the same in the question paper, addendum and memo? 2.5 Are the questions numbered correctly? 2.6 Is the language used appropriate to the grade level? 2.7 Are all cognitive levels addressed? 2.8 Are all questions allocated appropriate marks in question paper and memo? 2.9 Are total marks calculated correctly in the question paper and memo? 2.10 Is the proper format of the followed: Source-based, Paragraph, Essay writing 3. ADDENDUM 3.1 Are chosen sources relevant to the key questions? 3.2 Are sources properly contextualised and acknowledged? 3.3 Are sources numbered correctly and visual sources clearly labelled? 3.4 Is the length of the sources acceptable? 3.5 Did the source clarify difficult words? 3.6 Is variety in sources considered? 4. MEMORANDUM 4.1 Do answers correspond with the questions? 4.2 Are all alternative and relevant responses provided in the memo? 4.3 Does the mark allocation indicated on the memo correspond with the marks on the question paper? 4.4 Is there evidence of the symbols used in marking of paragraphs and essays? 4.5 Are rubric / matrix for paragraphs and essays included? 4.6 Is the analysis grid included?

DISTRICT OFFICE: SUBJECT GRADE NAME OF SCHOOL NAME OF EDUCATOR (S) NAME OF HOD DATES

1. MARKING YES NO COMMENTS

1.1 Is the task marked according to the memo?

1.2 Are all questions in the task properly marked?

1.3 Are all alternative responses considered in the marking process? 1.4 Are the marks correctly added?

1.6 Did the marker submit all learner scripts for moderation ?

1.7 Did the HOD/ Subject Head moderate 10% of learners’ scripts?

1.8 Was the marking fair, consistent and acceptable?

1.9 Are the marks approved for recording?

2.ASSESSMENT TOOLS YES NO COMMENTS 2.1 Did the Teacher use Paragraph rubric to mark the paragraph question?

2.2 Is there evidence of comment at the end of the paragraph?

2.3 Did the Teacher use Essay matrix to mark the essay?

2.4 Is there evidence of comment at the end of the essay? 2.5 Is there evidence of totalling for both source-based and/or Essay questions? 3.RECORDING YES NO COMMENTS Is there evidence of task being recorded after moderation? Are the learners’ marks corresponding with the marks in the mark sheet? Are the marks correctly converted according to the CAPS document? Is there moderation feedback? Where Time Frames on marking and moderation of the task adhered to?

SBA MODERATION

NAME OF SCHOOL DISTRICT MODERATOR

PART 1: TEACHER’S FILE

Quality Indicators Y N Comment

1.1 Is the teacher’s file submitted?

1.2 The teacher’s file is neat, organised and accessible, and contains all the required

documents. ( PoA, mark sheets, moderation reports (school, district), tasks, memos)

1.3 Is there a diagnostic analysis of all task

1.4 School moderation reports: Are they effective?

1.5 Moderation reports: Was feedback given to the

1.6 Moderation reports: Were recommended changes

actioned by the school from previous moderation

Working mark sheets/Marklists/ sasams records

1.7 Was there correct transfer of marks from the

learners’ evidence to the working mark sheet?

1.8 Was there evidence of extended opportunities to learners who did not submit tasks with valid reason reason?

PART 2: LEARNER EVIDENCE OF WORK

4. CRITERION 1 - QUALITY OF MARKING

Quality Indicators Y N Comments

1.1 Is marking consistent with and adheres to the

marking guideline?

1.2 Were all tasks dated and signed by the educator? State your observations in this regard.

1.3 Are the totalling of marks and transfer of marks to

the mark sheet accurate?

5. CRITERION 2 - INTERNAL MODERATION

2.1 Is there evidence that the learners’ work has been moderated at the following levels?

2.1.1 School: Pre and Post

2.1.2 District

2.2 Is there evidence of feedback from moderator?

CRITERION 3- DAIGNOSTIC REPORTS

3.1 Is there evidence of diagnostic reports in the

file? 3.2 Is there breakdown of learner performance

per level? 3.3 Is there narrative feedback and intervention

3.4 Any room for improvement from diagnostic report

CRITERION 4- MODERATOR’S FEEDBACK

Good Practice: ______

Challenges: ______Recommendations: ______

______Signature Date

- Bambatha_Rebellion

- Aleksander_Majkowski

- Belarusians_in_Lithuania

- Godfrey_Lagden

- History_of_South_Africa

- Martin_Legassick

- Anton_Niklas_Sundberg

- Gottfrid_Billing

- History_of_Swedish

- Bhaca_people

- Jane_Cobden

- Reynhard_Sinaga

- Zulu_royal_family

- Agrarian_Union_(Poland)

- Hilda_Kuper

- Isaac_Schapera

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Heritage in contemporary grade 10 South African history textbooks: A case study

2012, Masters Dissertation in History Education

Related Papers

Yesterday&Today No 10

Dr Raymond Nkwenti Fru

Yesterday and Today

Johan Wassermann

Southern African journal of environmental education

Cryton Zazu

This conceptual paper is based on experiences and insights which have emerged from my quest to develop a conceptual framework for working with the term 'heritage' within an education for sustainable development study that I am currently conducting. Of specific interest to me, and having potential to improve the relevance and quality of heritage education in southern Africa, given the region's inherent cultural diversity and colonial history, is the need for 'heritage construct inclusivity' within the processes constituting heritage education practices. Working around this broad research goal, I therefore needed to be clear about what I mean or refer to as heritage. I realised, however, how elusive and conceptually problematic the term 'heritage' is. I therefore, drawing from literature and experiences gained during field observations and focus group interviews, came up with the idea of working with three viewpoints of heritage. Drawing on real life cases ...

Alta Engelbrecht

This article focuses on the analysis of three textbooks that are based on the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), a revised curriculum from the National Curriculum Statement which was implemented in 2008. The article uses one element of a historical thinking framework, the analysis of primary sources, to evaluate the textbooks. In the analysis of primary sources the three heuristics distilled by Wineburg (2001) such as sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing are used to evaluate the utilisation of the primary sources in the three textbooks. According to the findings of this article, the writing of the three textbooks is still framed in an outdated mode of textbooks' writing in a dominant narrative style, influenced by Ranke's scientific paradigm or realism. The three textbooks have many primary sources that are poorly contextualized and which inhibit the implementation of sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing heuristics. Although, some primary sources are contextualized, source-based questions are not reflecting most of the elements of sourcing, corroborating and contextualizing heuristics. Instead, they are mostly focused on the information on the source which is influenced by the authors' conventional epistemological beliefs about school history as a compendium of facts. This poor contextualization of sources impacted negatively on the analysis of primary sources by learners as part and parcel of " doing history " in the classroom.

abram mothiba

School history textbooks are seen to embody ideological messages about whose history is important, as they aim both to develop an 'ideal' citizen and teach the subject of history. Since the 1940s, when the first study was done, there have been studies of South African history textbooks that have analysed different aspects of textbooks. These studies often happen at a time of political change (for example, after South Africa became a republic in 1961 or post-apartheid) which often coincides with a time of curriculum change. This article provides an overview of all the studies of South African history textbooks since the 1940s. We compiled a data base of all studies conducted on history textbooks, including post graduate dissertations, published journal articles, books and book chapters. This article firstly provides a broad overview of all the peer-reviewed studies, noting in particular how the number of studies has increased since 2000. The second section then engages in a more detailed analysis of the studies that did content analysis of textbooks. We compare how each study has engaged with the following issues: the object of study, the methodological approach, the sample of textbooks and the theoretical or philosophical orientation. The aim is to provide a broad picture of the state of textbook analysis studies over the past 75 years, and to build up a database of these studies so as to provide an overview of the nature of history textbook research in South Africa.

Pranitha Bharath

The Southern African Journal of Environmental Education

Felisa Tibbitts

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Katalin Eszter Morgan

Itamar Freitas

Southern African Review of Education

Linda Chisholm

Book Review

Catherine Namono

Carol Bertram

bhekani zondi

Elize Van Eeden

London Review of Education

Kate Angier

Noor Davids

Journal of Southern African Studies

Barbara Wahlberg

Journal of Natal and Zulu History

Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado

Paul Maluleka

Yesterday & Today

Reville Nussey

The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa

Ran Greenstein

Dorothy Sebbowa

South African Historical Journal

Julie Parle

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Essay on Heritage Day

Introduction

Heritage Day, a celebration rooted in the rich tapestry of cultural diversity , holds profound significance in honoring and preserving the heritage of a nation. Originating in South Africa, formerly known as Shaka Day, it officially became Heritage Day in 1996 and is celebrated annually on September 24th. This commemoration serves as a reminder of the collective contributions of various cultural groups to the nation’s identity. It emphasizes the importance of understanding, appreciating, and safeguarding cultural traditions, customs, and histories. Heritage Day stands as a testament to the unity found in diversity and underscores the need to cherish and celebrate cultural heritage.

Origin of Heritage Day

The origin of Heritage Day traces back to the struggles and triumphs of South Africa’s diverse population . Here’s a detailed explanation:

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

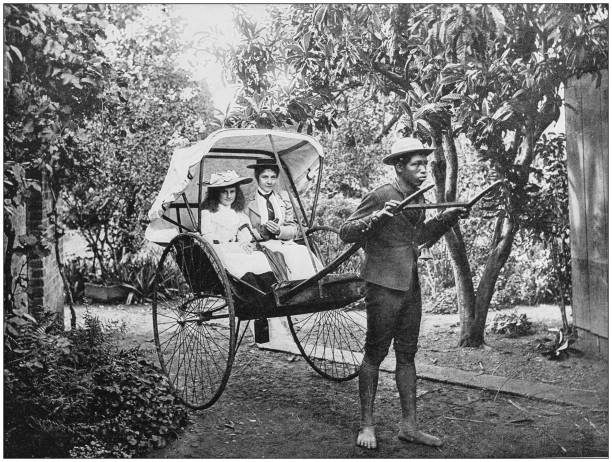

- Pre-Apartheid Era : Before the formal establishment of Heritage Day, South Africa, like many colonized nations, was characterized by a complex social landscape comprising indigenous African tribes, European settlers, and, later, descendants of enslaved peoples from various parts of the world. Each of these groups brought distinct cultures, languages, traditions, and customs, contributing to the vibrant tapestry of South African society.

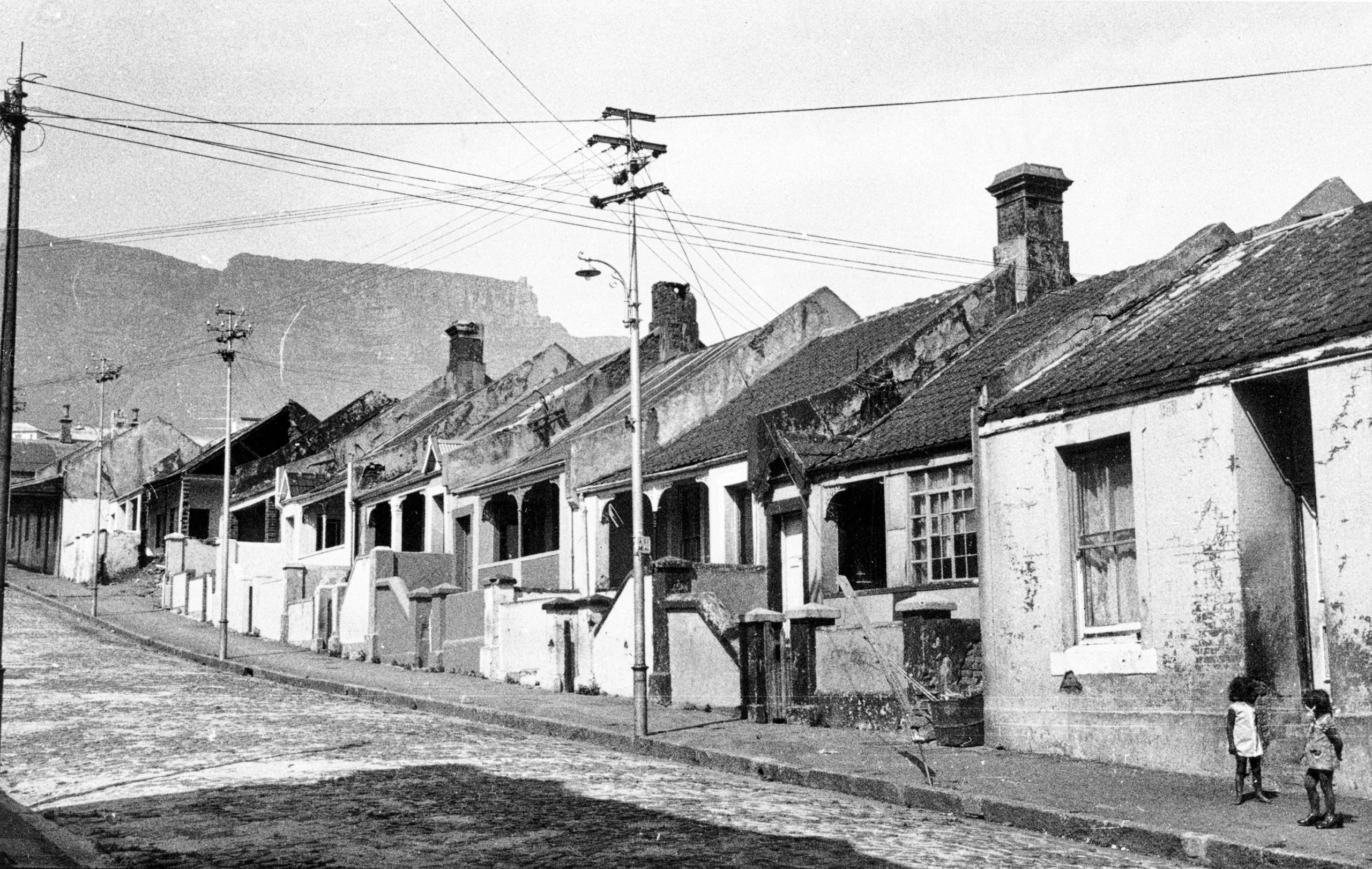

- Apartheid Era : During the apartheid era, which started in 1948 and continued until the early 1990s, South Africa faced systematic racial segregation and discrimination. Apartheid policies sought to divide the population along racial lines, with the white minority exerting political and economic dominance over the majority non-white population. These oppressive policies aimed to suppress the cultural identities and heritage of non-white South Africans, enforcing racial segregation in schools, neighborhoods, and public facilities.

- Emergence of Resistance : Despite the systemic oppression, South Africans from diverse cultural backgrounds resisted apartheid through various means, including protests, strikes, and underground political movements. The struggle against apartheid was not solely a political battle but also a cultural one, as marginalized communities fought to preserve their languages, traditions, and cultural practices in the face of suppression.

- Shift Towards Unity : As the apartheid regime began to unravel in the late 20th century, there was a growing recognition of the need to foster unity and reconciliation among South Africa’s diverse population. Leaders such as Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu advocated for a society based on inclusivity, equality, and respect for all cultural groups. This shift towards unity laid the foundation for initiatives to celebrate and preserve South Africa’s cultural heritage.

- Establishment of Heritage Day : In 1994, with the dawn of democracy in South Africa and the end of apartheid, the new government under President Nelson Mandela sought to promote national unity and reconciliation. In 1996, Heritage Day was officially declared as a public holiday, replacing the previously celebrated Shaka Day in KwaZulu-Natal. The renaming of the holiday to Heritage Day symbolized a broader recognition and celebration of the diverse cultural heritage of all South Africans, irrespective of race, ethnicity, or creed.

- Celebration of Diversity : Since its establishment, Heritage Day has served as an occasion for South Africans to celebrate their cultural heritage and diversity. It encourages people from all walks of life to embrace and showcase their traditions, languages, cuisines, music, dance, and attire. Through various events, including communal gatherings, festivals, and cultural performances, South Africans unite to honor their shared history and heritage while celebrating their unique differences.

Cultural Significance

The cultural significance of Heritage Day lies in its celebration and preservation of the diverse cultural heritage that defines a nation. Here’s an in-depth exploration of its cultural significance:

- Celebrating Diversity : Heritage Day serves as a platform to celebrate the multitude of cultures, languages, traditions, and customs contributing to a nation’s rich tapestry of identity. It acknowledges the unique heritage of various cultural groups, recognizing their distinct contributions to the national cultural mosaic.

- Promoting Understanding and Tolerance : Heritage Day promotes understanding, tolerance, and appreciation among communities by showcasing diverse cultural practices and traditions. It encourages people to learn about and respect the cultural identities of others, fostering a sense of unity and inclusivity.

- Preserving Cultural Heritage : Heritage Day plays a crucial role in preserving cultural heritage by highlighting traditional customs, rituals, and practices that may be at risk of being lost or forgotten. It encourages communities to pass their cultural knowledge and traditions to future generations, ensuring continuity and relevance.

- Empowering Communities : Heritage Day is a source of pride and empowerment for many communities, allowing them to showcase their cultural heritage and assert their identity. It allows marginalized or historically oppressed groups to reclaim and reaffirm their cultural identities in a public forum.

- Strengthening Social Cohesion : Heritage Day fosters social cohesion and unity among people from different backgrounds by celebrating cultural diversity. It promotes a sense of belonging and shared national identity, transcending divisions based on race, ethnicity, religion, or language .

- Promoting Tourism and Economic Development: Heritage Day celebrations attract tourists and visitors interested in experimenting with countries’ local cultures and heritage countries . This influx of visitors can stimulate economic activity in local communities, supporting small businesses, artisans, and cultural institutions.

- Resisting Cultural Erosion : Heritage Day reminds us of the value of maintaining customs and traditions in a time of rapid cultural change and globalization . It provides an opportunity to resist cultural erosion and homogenization, reaffirming the value of cultural diversity and heritage preservation.

Celebrations and Activities

Here’s an in-depth exploration of the celebrations and activities associated with Heritage Day, highlighting various aspects and traditions:

1. National and Local Events

- Parades and Processions : Many cities and towns organize colorful parades and processions featuring participants dressed in traditional attire representing different cultural groups.

- Cultural Festivals : Organizers arrange large-scale cultural festivals showcasing music, dance, art, and cuisine from various communities.

- Heritage Sites Visits : Heritage Day often includes guided tours to historical sites, museums, and cultural landmarks, allowing visitors to learn about the country’s rich heritage.

2. Community Gatherings

- Family Reunions : Families often come together on Heritage Day to reconnect and celebrate their shared cultural heritage.

- Community Picnics : Community picnics or braais (barbecues) are popular, where people gather in parks or open spaces to enjoy traditional foods and socialize.

- Cultural Performances : Local community centers or cultural organizations may host performances featuring traditional music, dance, storytelling, and theatrical presentations.

3. Cultural Demonstrations