- Sign up and Get Listed

Outside of US & canada

Be found at the exact moment they are searching. Sign up and Get Listed

- For Professionals

- Worksheets/Resources

- Get Help

- Learn

- For Professionals

- About

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Marriage Counselor

- Find a Child Counselor

- Find a Support Group

- Find a Psychologist

- If You Are in Crisis

- Self-Esteem

- Sex Addiction

- Relationships

- Child and Adolescent Issues

- Eating Disorders

- How to Find the Right Therapist

- Explore Therapy

- Issues Treated

- Modes of Therapy

- Types of Therapy

- Famous Psychologists

- Psychotropic Medication

- What Is Therapy?

- How to Help a Loved One

- How Much Does Therapy Cost?

- How to Become a Therapist

- Signs of Healthy Therapy

- Warning Signs in Therapy

- The GoodTherapy Blog

- PsychPedia A-Z

- Dear GoodTherapy

- Share Your Story

- Therapy News

- Marketing Your Therapy Website

- Private Practice Checklist

- Private Practice Business Plan

- Practice Management Software for Therapists

- Rules and Ethics of Online Therapy for Therapists

- CE Courses for Therapists

- HIPAA Basics for Therapists

- How to Send Appointment Reminders that Work

- More Professional Resources

- List Your Practice

- List a Treatment Center

- Earn CE Credit Hours

- Student Membership

- Online Continuing Education

- Marketing Webinars

- GoodTherapy’s Vision

- Partner or Advertise

- For Professionals >

- Software Technology >

- Practice Management >

- Article >

Assigning Homework in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

It’s certainly true that therapy outcomes depend in part on the work taking place in each session. But for this progress to reach its full impact, clients need to use what they learn in therapy during their daily lives.

Assigning therapy “homework” can help your clients practice new skills during the week. While many types of therapy may involve some form of weekly assignment, homework is a key component of cognitive behavior therapy.

Types of Homework

Some clients may respond well to any type of homework, while others may struggle to complete or find benefit in certain assignments. It’s important for clients to step outside of their comfort zone in some ways. For example, it’s essential to learn to challenge unwanted thoughts and increase understanding of feelings and emotions, especially for people who struggle with emotional expression.

But there isn’t just one way to achieve these goals. Finding the right type of homework for each client can make success more likely.

There are many different types of therapy homework. Asking your client to practice breathing exercises when they feel anxious or stressed? That’s homework. Journaling about distressing thoughts and ways to challenge them, or keeping track of cognitive distortions ? Also homework.

Some clients may do well with different assignments each week, while others may have harder times with certain types of homework. For example:

- An artistic client may not get much from written exercises. They might, however, prefer to sketch or otherwise illustrate their mood, feelings, or reactions during the week.

- Clients who struggle with or dislike reading may feel challenged by even plain-language articles. If you plan to assign educational materials, ask in your first session whether your client prefers audio or written media.

When you give the assignment, take a few minutes to go over it with your client. Give an example of how to complete it and make sure they understand the process. You’ll also want to explain the purpose of the assignment. Someone who doesn’t see the point of a task may be less likely to put real effort into it. If you give a self-assessment worksheet early in the therapy process, you might say, “It can help to have a clear picture of where you believe you’re at right now. Later in therapy I’ll ask you to complete another assessment and we can compare the two to review what’s changed.”

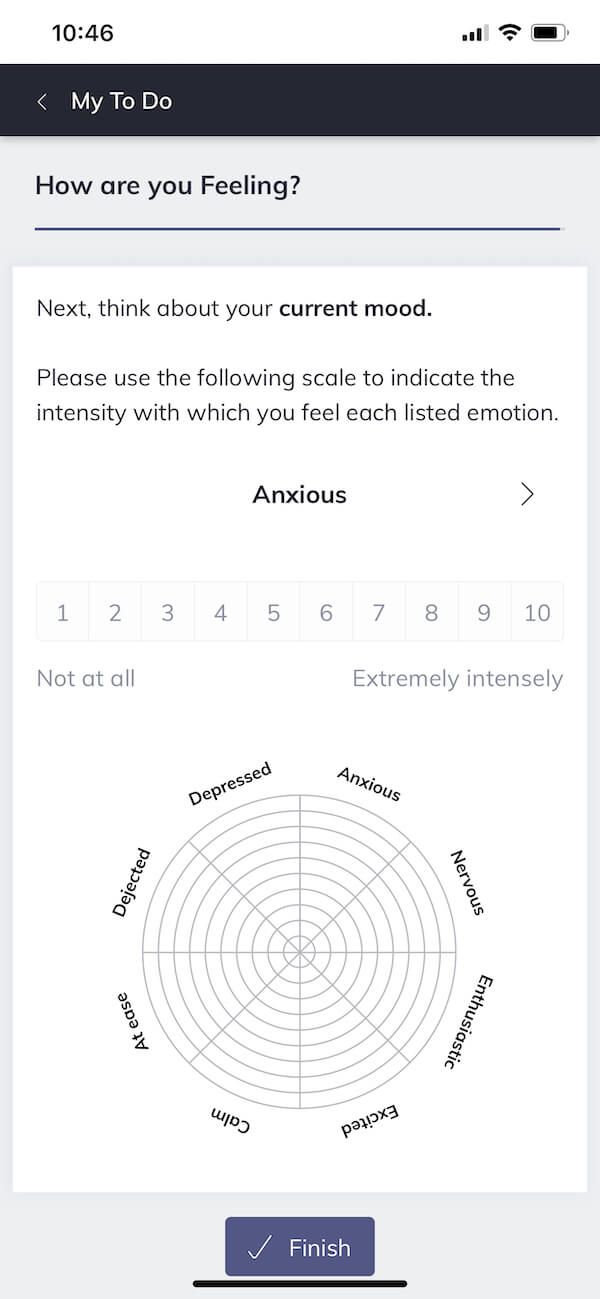

Mental Health Apps

Some people may also find apps a useful way to develop and practice emotional wellness coping skills outside of therapy. Therapy apps can help people track their moods, emotions, or other mental health symptoms. They can provide a platform to practice CBT or other therapy skills. They can also offer structured mindfulness meditations or help clients practice other grounding techniques.

If you’re working with a client who’s interested in therapy apps, you might try using them in treatment. Just keep in mind that not all apps offer the same benefits. Some may have limitations, such as clunky or confusing interfaces and potential privacy concerns. It’s usually a good idea to check whether there’s any research providing support for—or against—a specific app before recommending it to a client.

Trusted mental health sources, such as the American Psychological Association or Anxiety and Depression Association of America websites, may list some popular mental health apps, though they may not specifically endorse them. These resources can be a good starting place. Other organizations, including Northwestern University’s Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies and the Defense Department of the United States, have developed their own research-backed mental health apps.

You can also review apps yourself. Try out scenarios or options within the app to get to know how the app works and whether it might meet your client’s needs. This will put you in a position to answer their questions and help give them tips on getting the most out of the app.

Benefits of Homework

Some of your clients may wonder why you’re assigning homework. After all, they signed up for therapy, not school.

When clients ask about the benefits of therapy homework, you can point out how it provides an opportunity to put things learned in session into practice outside the therapy session. This helps people get used to using the new skills in their toolbox to work through issues that come up for them in their daily lives. More importantly, it teaches them they can use these skills on their own, when a therapist or other support person isn’t actively providing coaching or encouragement. This knowledge is an important aspect of therapy success.

A 2010 review of 23 studies on homework in therapy found evidence to suggest that clients who completed therapy homework generally had better treatment outcomes. This review did have some limitations, such as not considering the therapeutic relationship or how clients felt about homework. But other research supports these findings, leading many mental health experts to support the use of therapy homework, particularly in CBT. Homework can be one of many effective tools in making therapy more successful.

Improving Homework Compliance

You may eventually work with a client who shows little interest in homework and doesn’t complete the assignments. You know this could impede their progress in therapy, so you’ll probably want to bring this up in session and ask why they’re having difficulty with the homework. You can also try varying the types of homework you assign or asking if your client is interested in trying out a mental health app that can offer similar benefits outside your weekly sessions.

When you ask a client about homework non-compliance, it’s important to do it in a way that doesn’t anger them, make them feel defensive, or otherwise damage the relationship you’re working to develop. Here are some tips for having this conversation:

- Let them know homework helps them practice their skills outside of therapy. In short, it’s helping them get more out of therapy (more value for their money) and may lead to more improvement, sometimes in a shorter period of time than one weekly session would alone.

- Bring up the possibility of other types of homework. “If you don’t want to write anything down, would you want to try listening to a guided meditation or tips to help manage upsetting emotions?”

- Ask about it, in a non-confrontational way. You might say something like, “Is something making it difficult for you to complete the homework assignments? How can I help make the process easier for you?”

The prospect of homework in therapy may surprise some clients, but for many people, it’s an essential element of success. Those put off by the term “homework” may view “skills practice” or similar phrasing more favorably, so don’t feel afraid to call it something else. The important part is the work itself, not what you call it. References:

- Ackerman, C. (2017, March 20). 25 CBT techniques and worksheets for cognitive behavioral therapy. Retrieved from https://positivepsychology.com/cbt-cognitive-behavioral-therapy-techniques-worksheets

- ADAA reviewed mental health apps. (n.d.). Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Retrieved from https://adaa.org/finding-help/mobile-apps

- Mausbach, B. T., Moore, R., Roesch, S., Cardenas, V., & Patterson, T. L. (2010). The relationship between homework compliance and therapy outcomes: An updated meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34 (5), 429-438. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2939342

- Mental health apps. (n.d.). The American Institute of Stress. Retrieved from https://www.stress.org/mental-health-apps

- Novotney, A. (2016). Should you use an app to help that client? Monitor on Psychology, 47 (10), 64. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2016/11/client-app

- Tang, W, & Kreindler, D. (2017). Supporting homework compliance in cognitive behavioural therapy: Essential features of mobile apps. JMIR Mental Health, 4(2). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5481663

Professional Resources

- Starting a Private Practice

- Setting Sliding Scale Fees

- Tips for Intake Sessions

- How Salaries Vary Across Industries

- 10 Ways to Strengthen Therapeutic Relationships

Learn from Experts: Improve Your Practice and Business

Trusted by thousands of mental health professionals just like you.

Every month, GoodTherapy will send you great content, curated from leading experts, on how to improve your practice and run a healthier business. Get the latest on technology, software, new ideas, marketing, client retention, and more... Sign up today .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Therapy Homework?

Astrakan Images / Getty Images

Types of Therapy That Involve Homework

If you’ve recently started going to therapy , you may find yourself being assigned therapy homework. You may wonder what exactly it entails and what purpose it serves. Therapy homework comprises tasks or assignments that your therapist asks you to complete between sessions, says Nicole Erkfitz , DSW, LCSW, a licensed clinical social worker and executive director at AMFM Healthcare, Virginia.

Homework can be given in any form of therapy, and it may come as a worksheet, a task to complete, or a thought/piece of knowledge you are requested to keep with you throughout the week, Dr. Erkfitz explains.

This article explores the role of homework in certain forms of therapy, the benefits therapy homework can offer, and some tips to help you comply with your homework assignments.

Therapy homework can be assigned as part of any type of therapy. However, some therapists and forms of therapy may utilize it more than others.

For instance, a 2019-study notes that therapy homework is an integral part of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) . According to Dr. Erkfitz, therapy homework is built into the protocol and framework of CBT, as well as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) , which is a sub-type of CBT.

Therefore, if you’re seeing a therapist who practices CBT or DBT, chances are you’ll regularly have homework to do.

On the other hand, an example of a type of therapy that doesn’t generally involve homework is eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. EMDR is a type of therapy that generally relies on the relationship between the therapist and client during sessions and is a modality that specifically doesn’t rely on homework, says Dr. Erkfitz.

However, she explains that if the client is feeling rejuvenated and well after their processing session, for instance, their therapist may ask them to write down a list of times that their positive cognition came up for them over the next week.

"Regardless of the type of therapy, the best kind of homework is when you don’t even realize you were assigned homework," says Erkfitz.

Benefits of Therapy Homework

Below, Dr. Erkfitz explains the benefits of therapy homework.

It Helps Your Therapist Review Your Progress

The most important part of therapy homework is the follow-up discussion at the next session. The time you spend reviewing with your therapist how the past week went, if you completed your homework, or if you didn’t and why, gives your therapist valuable feedback on your progress and insight on how they can better support you.

It Gives Your Therapist More Insight

Therapy can be tricky because by the time you are committed to showing up and putting in the work, you are already bringing a better and stronger version of yourself than what you have been experiencing in your day-to-day life that led you to seek therapy.

Homework gives your therapist an inside look into your day-to-day life, which can sometimes be hard to recap in a session. Certain homework assignments keep you thinking throughout the week about what you want to share during your sessions, giving your therapist historical data to review and address.

It Helps Empower You

The sense of empowerment you can gain from utilizing your new skills, setting new boundaries , and redirecting your own cognitive distortions is something a therapist can’t give you in the therapy session. This is something you give yourself. Therapy homework is how you come to the realization that you got this and that you can do it.

"The main benefit of therapy homework is that it builds your skills as well as the understanding that you can do this on your own," says Erkfitz.

Tips for Your Therapy Homework

Below, Dr. Erkfitz shares some tips that can help with therapy homework:

- Set aside time for your homework: Create a designated time to complete your therapy homework. The aim of therapy homework is to keep you thinking and working on your goals between sessions. Use your designated time as a sacred space to invest in yourself and pour your thoughts and emotions into your homework, just as you would in a therapy session .

- Be honest: As therapists, we are not looking for you to write down what you think we want to read or what you think you should write down. It’s important to be honest with us, and yourself, about what you are truly feeling and thinking.

- Practice your skills: Completing the worksheet or log are important, but you also have to be willing to put your skills and learnings into practice. Allow yourself to be vulnerable and open to trying new things so that you can report back to your therapist about whether what you’re trying is working for you or not.

- Remember that it’s intended to help you: Therapy homework helps you maximize the benefits of therapy and get the most value out of the process. A 2013-study notes that better homework compliance is linked to better treatment outcomes.

- Talk to your therapist if you’re struggling: Therapy homework shouldn’t feel like work. If you find that you’re doing homework as a monotonous task, talk to your therapist and let them know that your heart isn’t in it and that you’re not finding it beneficial. They can explain the importance of the tasks to you, tailor your assignments to your preferences, or change their course of treatment if need be.

"When the therapy homework starts 'hitting home' for you, that’s when you know you’re on the right track and doing the work you need to be doing," says Erkfitz.

A Word From Verywell

Similar to how school involves classwork and homework, therapy can also involve in-person sessions and homework assignments.

If your therapist has assigned you homework, try to make time to do it. Completing it honestly can help you and your therapist gain insights into your emotional processes and overall progress. Most importantly, it can help you develop coping skills and practice them, which can boost your confidence, empower you, and make your therapeutic process more effective.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Conklin LR, Strunk DR, Cooper AA. Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression . Cognit Ther Res . 2018;42(1):16-23. doi:10.1007/s10608-017-9873-6

Lebeau RT, Davies CD, Culver NC, Craske MG. Homework compliance counts in cognitive-behavioral therapy . Cogn Behav Ther . 2013;42(3):171-179. doi:10.1080/16506073.2013.763286

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

The importance of homework in therapy

by Elyssa Barbash | Jul 25, 2018 | change , growth , Self-improvement , success , Therapy , Uncategorized , worry | 0 comments

There has been significant research conducted on the use of homework in therapy. Findings consistently indicate that homework maximizes the benefit of therapy and allows clients to realize gains in their life.

At the beginning of therapy, homework is a topic that I review with all of my patients. However, there still comes the times where I have to re-review the importance of homework with my patients after they share they have not completed their work!

Purpose of Homework

Homework in therapy is intended to allow the person to implement the strategies that are being learned in therapy so that they can actualize the changes and gains they are seeking to make in their life. I like to put it this way: therapy sessions do not consume a very large portion of your life. At most, we are talking about 45 to 50 minutes out of your week that you are in a therapy session. While the therapy session lays the foundation for the changes to occur in your life, the actual therapy session is such a small portion of your time and is a false reality.

The place is where you will actually see the gains and progress being made is in your every day life.

This is where homework comes in. To maximize the value of therapy, homework helps you to implement the strategies being learned in your life so you can actually see changes. Homework is usually skills oriented, though not always. When it is skills oriented, it teaches the person how to deal with their problems on their own and not have to rely on their therapist. (Bonus: Any ethical therapist will approach treatment in this way. However, not all therapies are intended to be skills building so this is not to say that those therapist to don’t assign homework are unethical!).

Benefits of Homework

Remember, this is not school. Homework being assigned is not being given to you to keep you busy. If your therapist assigned the homework, it is with the best intentions that what they are asking you to do is going to help you. It is also likely to lead to shortened treatment times, which means overall reduced costs related to treatment and less time dedicated to the therapy process in the long run.

A Strong Indication of your commitment to Therapy, and to yourself

Finally, completing your homework is an indication of your commitment to therapy, which is a greater indication of your commitment to yourself. When you do not follow through and complete your homework, the message that you are sending is that you really don’t care. And a therapist cannot truly help you if you do not care.

So the next time you want to skip that homework assignment your therapist gave you, remember what the true purpose of it is and how much you want that change in your life.

We are here to help

Contact us today to schedule an appointment. Whatever the reason, give us a call. Remember, there are many reasons why people seek therapy. Professional mental health assistance can greatly benefit you in many ways, including making important changes in your life.

We are committed to providing therapy and counseling services in a comfortable, relaxing, encouraging, and non-judgmental environment to yield the most realistic and best outcomes. Give us a call or email us today to schedule an appointment.

Email Address

Phone Number

Sign-up for our mailing list.

Join Our Mailing List

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- 6 Signs You Should Break Up With Your Therapist | by Anja Vojta, MSc - BestBlog - […] your therapy sessions lay a good foundation, you cannot expect 50 minutes to miraculously change all the (bad) patterns…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Recent Posts

- Thanksgiving: Something to be Thankful For

- Anxiety, Trauma, and PTSD in the Aftermath of Hurricanes

- Therapy with a REAL Trauma Therapist – Part 3

- HOW TO FIND A REAL TRAUMA THERAPIST AND WHAT YOU SHOULD LOOK FOR – PART 2

- Not all Therapists Are Equal: Therapy with a Real Trauma Therapist – Part 1

How to Design Homework in CBT That Will Engage Your Clients

Take-home assignments provide the opportunity to transfer different skills and lessons learned in the therapeutic context to situations in which problems arise.

These opportunities to translate learned principles into everyday practice are fundamental for ensuring that therapeutic interventions have their intended effects.

In this article, we’ll explore why homework is so essential to CBT interventions and show you how to design CBT homework using modern technologies that will keep your clients engaged and on track to achieving their therapeutic goals.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will provide you with a detailed insight into positive CBT and give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

Why is homework important in cbt, how to deliver engaging cbt homework, using quenza for cbt: 3 homework examples, 3 assignment ideas & worksheets in quenza, a take-home message.

Many psychotherapists and researchers agree that homework is the chief process by which clients experience behavioral and cognitive improvements from CBT (Beutler et al., 2004; Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2000).

We can find explanations as to why CBT homework is so crucial in both behaviorist and social learning/cognitive theories of psychology.

Behaviorist theory

Behaviorist models of psychology, such as classical and operant conditioning , would argue that CBT homework delivers therapeutic outcomes by helping clients to unlearn (or relearn) associations between stimuli and particular behavioral responses (Huppert, Roth Ledley, & Foa, 2006).

For instance, imagine a woman who reacts with severe fright upon hearing a car’s wheels skidding on the road because of her experience being in a car accident. This woman’s therapist might work with her to learn a new, more adaptive response to this stimulus, such as training her to apply new relaxation or breathing techniques in response to the sound of a skidding car.

Another example, drawn from the principles of operant conditioning theory (Staddon & Cerutti, 2003), would be a therapist’s invitation to a client to ‘test’ the utility of different behaviors as avenues for attaining reward or pleasure.

For instance, imagine a client who displays resistance to drawing on their support networks due to a false belief that they should handle everything independently. As homework, this client’s therapist might encourage them to ‘test’ what happens when they ask their partner to help them with a small task around the house.

In sum, CBT homework provides opportunities for clients to experiment with stimuli and responses and the utility of different behaviors in their everyday lives.

Social learning and cognitive theories

Scholars have also drawn on social learning and cognitive theories to understand how clients form expectations about the likely difficulty or discomfort involved in completing CBT homework assignments (Kazantzis & L’Abate, 2005).

A client’s expectations can be based on a range of factors, including past experience, modeling by others, present physiological and emotional states, and encouragement expressed by others (Bandura, 1989). This means it’s important for practitioners to design homework activities that clients perceive as having clear advantages by evidencing these benefits of CBT in advance.

For instance, imagine a client whose therapist tells them about another client’s myriad psychological improvements following their completion of a daily thought record . Identifying with this person, who is of similar age and presents similar psychological challenges, the focal client may subsequently exhibit an increased commitment to completing their own daily thought record as a consequence of vicarious modeling.

This is just one example of how social learning and cognitive theories may explain a client’s commitment to completing CBT homework.

Let’s now consider how we might apply these theoretical principles to design homework that is especially motivating for your clients.

In particular, we’ll be highlighting the advantages of using modern digital technologies to deliver engaging CBT homework.

Designing and delivering CBT homework in Quenza

Gone are the days of grainy printouts and crumpled paper tests.

Even before the global pandemic, new technologies have been making designing and assigning homework increasingly simple and intuitive.

In what follows, we will explore the applications of the blended care platform Quenza (pictured here) as a new and emerging way to engage your CBT clients.

Its users have noted the tool is a “game-changer” that allows practitioners to automate and scale their practice while encouraging full-fledged client engagement using the technologies already in their pocket.

To summarize its functions, Quenza serves as an all-in-one platform that allows psychology practitioners to design and administer a range of ‘activities’ relevant to their clients. Besides homework exercises, this can include self-paced psychoeducational work, assessments, and dynamic visual feedback in the form of charts.

Practitioners who sign onto the platform can enjoy the flexibility of either designing their own activities from scratch or drawing from an ever-growing library of preprogrammed activities commonly used by CBT practitioners worldwide.

Any activity drawn from the library is 100% customizable, allowing the practitioner to tailor it to clients’ specific needs and goals. Likewise, practitioners have complete flexibility to decide the sequencing and scheduling of activities by combining them into psychoeducational pathways that span several days, weeks, or even months.

Importantly, reviews of the platform show that users have seen a marked increase in client engagement since digitizing homework delivery using the platform. If we look to our aforementioned drivers of engagement with CBT homework, we might speculate several reasons why.

- Implicit awareness that others are completing the same or similar activities using the platform (and have benefitted from doing so) increases clients’ belief in the efficacy of homework.

- Practitioners and clients can track responses to sequences of activities and visually evidence progress and improvements using charts and reporting features.

- Using their own familiar devices to engage with homework increases clients’ self-belief that they can successfully complete assigned activities.

- Therapists can initiate message conversations with clients in the Quenza app to provide encouragement and positive reinforcement as needed.

The rest of this article will explore examples of engaging homework, assignments, and worksheets designed in Quenza that you might assign to your CBT clients.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find new pathways to reduce suffering and more effectively cope with life stressors.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Let’s now look at three examples of predesigned homework activities available through Quenza’s Expansion Library.

Urge Surfing

Many of the problems CBT seeks to address involve changing associations between stimulus and response (Bouton, 1988). In this sense, stimuli in the environment can drive us to experience urges that we have learned to automatically act upon, even when doing so may be undesirable.

For example, a client may have developed the tendency to reach for a glass of wine or engage in risky behaviors, hoping to distract themselves from negative emotions following stressful events.

Using the Urge Surfing homework activity, you can help your clients unlearn this tendency to automatically act upon their urges. Instead, they will discover how to recognize their urges as mere physical sensations in their body that they can ‘ride out’ using a six-minute guided meditation, visual diagram, and reflection exercise.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Moving From Cognitive Fusion to Defusion

Central to CBT is the understanding that how we choose to think stands to improve or worsen our present emotional states. When we get entangled with our negative thoughts about a situation, they can seem like the absolute truth and make coping and problem solving more challenging.

The Moving From Cognitive Fusion to Defusion homework activity invites your client to recognize when they experience a negative thought and explore it in a sequence of steps that help them gain psychological distance from the thought.

Finding Silver Linings

Many clients commencing CBT admit feeling confused or regretful about past events or struggle with self-criticism and blame. In these situations, the focus of CBT may be to work with the client to reappraise an event and have them look at themselves through a kinder lens.

The Finding Silver Linings homework activity is designed to help your clients find the bright side of an otherwise grim situation. It does so by helping the user to step into a positive mindset and reflect on things they feel positively about in their life. Consequently, the activity can help your client build newfound optimism and resilience .

As noted, when you’re preparing homework activities in Quenza, you are not limited to those in the platform’s library.

Instead, you can design your own or adapt existing assignments or worksheets to meet your clients’ needs.

You can also be strategic in how you sequence and schedule activities when combining them into psychoeducational pathways.

Next, we’ll look at three examples of how a practitioner might design or adapt assignments and worksheets in Quenza to help keep them engaged and progressing toward their therapy goals.

In doing so, we’ll look at Quenza’s applications for treating three common foci of treatment: anxiety, depression, and obsessions/compulsions.

When clients present with symptoms of generalized anxiety, panic, or other anxiety-related disorders, a range of useful CBT homework assignments can help.

These activities can include the practice of anxiety management techniques, such as deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and mindfulness training. They can also involve regular monitoring of anxiety levels, challenging automatic thoughts about arousal and panic, and modifying beliefs about the control they have over their symptoms (Leahy, 2005).

Practitioners looking to support these clients using homework might start by sending their clients one or two audio meditations via Quenza, such as the Body Scan Meditation or S.O.B.E.R. Stress Interruption Mediation . That way, the client will have tools on hand to help manage their anxiety in stressful situations.

As a focal assignment, the practitioner might also design and assign the client daily reflection exercises to be completed each evening. These can invite the client to reflect on their anxiety levels during the day by responding to a series of rating scales and open-ended response questions. Patterns in these responses can then be graphed, reviewed, and used to facilitate discussion during the client’s next in-person session.

As with anxiety, there is a range of practical CBT homework activities that aid in treating depression.

It should be noted that it is common for clients experiencing symptoms of depression to report concentration and memory deficits as reasons for not completing homework assignments (Garland & Scott, 2005). It is, therefore, essential to keep this in mind when designing engaging assignments.

CBT assignments targeted at the treatment of depressive symptoms typically center around breaking cycles of negative events, thinking, emotions, and behaviors, such as through the practice of reappraisal (Garland & Scott, 2005).

Examples of assignments that facilitate this may include thought diaries , reflections that prompt cognitive reappraisal, and meditations to create distance between the individual and their negative thoughts and emotions.

To this end, a practitioner looking to support their client might design a sequence of activities that invite clients to explore their negative cognitions once per day. This exploration can center on responses to negative feedback, faced challenges, or general low mood.

A good template to base this on is the Personal Coping Mantra worksheet in Quenza’s Expansion Library, which guides clients through the process of replacing automatic negative thoughts with more adaptive coping thoughts.

The practitioner can also schedule automatic push notification reminders to pop up on the client’s device if an activity in the sequence is not completed by a particular time each day. This function of Quenza may be particularly useful for supporting clients with concentration and memory deficits, helping keep them engaged with CBT homework.

Obsessions/compulsions

Homework assignments pertaining to the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder typically differ depending on the stage of the therapy.

In the early stages of therapy, practitioners assigning homework will often invite clients to self-monitor their experience of compulsions, rituals, or responses (Franklin, Huppert, & Roth Ledley, 2005).

This serves two purposes. First, the information gathered through self-monitoring, such as by completing a journal entry each time compulsive thoughts arise, will help the practitioner get clearer about the nature of the client’s problem.

Second, self-monitoring allows clients to become more aware of the thoughts that drive their ritualized responses, which is important if rituals have become mostly automatic for the client (Franklin et al., 2005).

Therefore, as a focal assignment, the practitioner might assign a digital worksheet via Quenza that helps the client explore phenomena throughout their day that prompt ritualized responses. The client might then rate the intensity of their arousal in these different situations on a series of Likert scales and enter the specific thoughts that arise following exposure to their fear.

The therapist can then invite the client to complete this worksheet each day for one week by assigning it as part of a pathway of activities. A good starting point for users of Quenza may be to adapt the platform’s pre-designed Stress Diary for this purpose.

At the end of the week, the therapist and client can then reflect on the client’s responses together and begin constructing an exposure hierarchy.

This leads us to the second type of assignment, which involves exposure and response prevention. In this phase, the client will begin exploring strategies to reduce the frequency with which they practice ritualized responses (Franklin et al., 2005).

To this end, practitioners may collaboratively set a goal with their client to take a ‘first step’ toward unlearning the ritualized response. This can then be built into a customized activity in Quenza that invites the client to complete a reflection.

For instance, a client who compulsively hoards may be invited to clear one box of old belongings from their bedroom and resist the temptation to engage in ritualized responses while doing so.

17 Science-Based Ways To Apply Positive CBT

These 17 Positive CBT & Cognitive Therapy Exercises [PDF] include our top-rated, ready-made templates for helping others develop more helpful thoughts and behaviors in response to challenges, while broadening the scope of traditional CBT.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Developing and administering engaging CBT homework that caters to your client’s specific needs or concerns is becoming so much easier with online apps.

Further, best practice is becoming more accessible to more practitioners thanks to the emergence of new digital technologies.

We hope this article has inspired you to consider how you might leverage the digital tools at your disposal to create better homework that your clients want to engage with.

Likewise, let us know if you’ve found success using any of the activities we’ve explored with your own clients – we’d love to hear from you.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free .

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist , 44 (9), 1175–1184.

- Beutler, L. E., Malik, M., Alimohamed, S., Harwood, T. M., Talebi, H., Noble, S., & Wong, E. (2004). Therapist variables. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed.) (pp. 227–306). Wiley.

- Bouton, M. E. (1988). Context and ambiguity in the extinction of emotional learning: Implications for exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy , 26 (2), 137–149.

- Franklin, M. E., Huppert, J. D., & Roth Ledley, D. (2005). Obsessions and compulsions. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R., Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 219–236). Routledge.

- Garland, A., & Scott, J. (2005). Depression. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R., Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 237–261). Routledge.

- Huppert, J. D., Roth Ledley, D., & Foa, E. B. (2006). The use of homework in behavior therapy for anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration , 16 (2), 128–139.

- Kazantzis, N. (2005). Introduction and overview. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R., Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 1–6). Routledge.

- Kazantzis, N., Deane, F. P., & Ronan, K. R. (2000). Homework assignments in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A meta‐analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice , 7 (2), 189–202.

- Kazantzis, N., & L’Abate, L. (2005). Theoretical foundations. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R., Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 9–34). Routledge.

- Leahy, R. L. (2005). Panic, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R., Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 193–218). Routledge.

- Staddon, J. E., & Cerutti, D. T. (2003). Operant conditioning. Annual Review of Psychology , 54 (1), 115–144.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Positive CBT Triangle Explained (+11 Worksheets)

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a popular and highly effective intervention model for dealing with multiple mental health conditions (Early & Grady, 2017; Yarwood et [...]

Fundamental Attribution Error: Shifting the Blame Game

We all try to make sense of the behaviors we observe in ourselves and others. However, sometimes this process can be marred by cognitive biases [...]

Halo Effect: Why We Judge a Book by Its Cover

Even though we may consider ourselves logical and rational, it appears we are easily biased by a single incident or individual characteristic (Nicolau, Mellinas, & [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (22)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (37)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

3 Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

- Last edited on September 9, 2020

Homework in CBT

Table of contents, why do homework in cbt, how to deliver homework, strategies to increase confidence.

Homework assignments in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can help your patients educate themselves further, collect thoughts, and modify their thinking.

Homework is not something that you just assign randomly. You should make sure you:

- tailor the homework to the patient

- provide a rationale for why the patient needs to do the homework

- uncover any obstacles that might prevent homework from being done (i.e. - busy work schedule, significant neurovegetative symptoms)

Types of homework

Types of homework assignments.

| Behavioural Activation | Getting active, depressed patients out of bed or off the couch, and helping them resume normal activity |

|---|---|

| Monitoring automatic thoughts | From the first session forward, you will encourage your patients to ask themselves, “What’s going through my mind right now?” |

| Evaluating and responding to automatic thoughts | At virtually every session, you will help patients modify their inaccurate and dysfunctional thoughts and write down their new way of thinking. Patients will also learn to evaluate their own thinking and practice doing so between sessions. |

| Problem-solving | At virtually every session, you will help patients devise solutions to their problems, which they will implement between sessions. |

| Behavioural skills | To effectively solve their problems, patients may need to learn new skills, which they will practice for homework. |

| Behavioural experiments | Patients may need to directly test the validity of automatic thoughts that seem distorted, such as “I’ll feel better if I stay in bed” |

| Bibliotherapy | Important concepts you are discussing in session can be greatly reinforced when patients read about them in black and white. |

| Preparing for the next session | Preparing for the next therapy session. The beginning part of each therapy session can be greatly speeded up if patients think about what is important to tell you before they enter your office. |

You should also decide the frequency of the homework should be assigned: should it be daily, weekly?

If your patient does not do homework, that’s OK! Explore as a team, in a non-judgmental way, to explore why the homework was not done. Here are some ways to increase adherence to homework:

- Tailor the assignments to the individual

- Provide a rationale for how and why the assignment might help

- Determine the homework collaboratively

- Try to start the homework during the session. This creates some momentum to continue doing the homework

- Set up systems to remember to do the assignments (phone reminders, sticky notes

- It is better to start with easier homework assignments and err on the side of caution

- They should be 90-100% confident they will be able to do this assignment

- Covert rehearsal - running through a thought experiment on a situation

- Change the assignment - It is far better to substitute an easier homework assignment that patients are likely to do than to have them establish a habit of not doing what they had agreed to in session

- Intellectual/emotional role play - “I’ll be the intellectual part of you; you be the emotional part. You argue as hard as you can against me so I can see all the arguments you’re using not to read your coping cards and start studying. You start.”

Is Therapy Homework Getting You Down? 8 Ways to Help

There is no failing with therapy homework, as long as you try..

Posted October 6, 2023 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

- What Is Therapy?

- Take our Do I Need Therapy?

- Find counselling near me

Homework between therapy sessions is a practice dating back decades and based on the idea that a client can improve therapy outcomes through practice. But what happens if therapy homework itself is too challenging or difficult? I have eight ways you can explore to understand and navigate therapy homework.

Before we go any further, though, I want to highlight the most important idea for you to take away: there is no failing with therapy homework, as long as you try .

History, Theory, Practical Use

So, what is the theory behind therapy homework? It's based on the principles of cognitive behavior therapy: by changing ways of thinking, we can change how we react and behave in challenging situations. Also, the inverse is true: by changing the ways we behave, we can change the way we think. Some therapy homework offers practice to help change the way we think, while other approaches focus on changing behavior.

There are three practical reasons to do therapy homework:

- If you’re able to practice noticing the state of mind and emotion you fall into during problematic moments, you’re halfway on your way to changing.

- Then, you have the opportunity to “talk back” to the difficult mindset that gets triggered.

- From there, you have the opportunity to nudge yourself into taking more healthy or intentional actions, instead of acting on impulse or out of detachment.

But the main reason is a classic that is still important: practice makes you better at what you’re doing .

Common Challenges to Doing Therapy Homework

Overcoming challenges always starts with beliefs and feelings. CBT therapists like to use the term “home practice” instead of homework to try and limit your association with school homework. Most of us have negative feelings or dread about homework and link it to the idea of getting a grade and the possibility of “getting it wrong.”

Negative Reactions to Homework

If your therapist suggests home practice, you may notice thoughts and feelings such as:

- Anticipating shame

- Drawing attention to your perceived flaws

- Intense self-criticism

- Anticipating disruptive ruminating

- Fear that you will be criticized for doing a “bad job”

Common Problems Completing Homework

Sometimes, behaviors communicate thoughts and feelings. So, if you find yourself doing the following, you may want to explore underlying feelings and beliefs:

- Procrastinating

- Avoiding or forgetting

- “Doing it in your head”

- Faking it (giving answers you think your therapist is looking for)

The Therapist's Role

As a therapist, I know our homework goal is complete when you simply tried to do the home practice. That’s it. It doesn’t have to be perfect, it doesn’t have to be exactly what the assignment was, it doesn’t have to be complete. As long as you give it a try, we start there. (Of course, if you had trouble with getting started, we start there!)

If you had a hard time motivating yourself to do the home practice, were unclear on how to complete it, or it just didn’t work as intended, I consider that my responsibility. I can change the assignment, improve our communication, or just try at a more opportune time in the therapy process.

8 Ways to Success with Therapy Homework

- Home practice is all about the experience, not the result. This means seeing what thoughts and feelings come up, or what behavior change challenges appear. As long as that is happening, the homework is a success.

- Be sure that you feel you understand the home practice, the goals and reasoning behind doing it, and that you are comfortable doing it. If you have any concerns, don’t hesitate to share.

- Be practical: Ensure you clearly understand what actions or steps are involved in completing the homework, so you’re not stuck wondering later.

- Be sure you have a specific plan for completing homework, including when you will do it, how long you will spend on it, and any obstacles you anticipate. Once you have a plan, ask yourself, on a scale of 1-10, how confident are you that you can do it?

- Be sure your therapist follows up with you on homework. It keeps you motivated and keeps the therapy on track.

- From the beginning, be as honest and direct as you can about your reactions and feelings on the topic of homework. If you have a history of difficulty with homework, it is important for your therapist to know. This will improve the odds of therapeutic success and make the process easier for you.

- Collaborate with your therapist on goals, assignments, and steps. The best therapy home practice is one where the client helps create it.

- Maybe now is not the time for homework? Maybe there is too much going on in your life, and you need more support or insight now.

If you follow these guidelines, you can take the discomfort and dread out of home practice, improve understanding with your therapist, and increase the odds that the therapy will be successful.

Oh, and you may also find yourself with some skills you can use to take care of yourself long after the therapy has ended.

Richard Brouillette, LCSW, is an online schema therapist working with entrepreneurs, creatives, and professionals.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Applications for the Beck Institute Certified Master Clinician program are open! Learn more .

- Impact of CBT

What is the Status of “Homework” in Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 50 Years On?

By Nikolaos Kazantzis, PhD

The comedian Jerry Seinfeld once asked:

“ What’s the deal with ‘homework?’ It’s not like you’re doing work on your home… ”

The great thing about that quote is that it conveys that the “H” word has some of the most unpleasant associations for clients in CBT. In July 2016, Dr. Judith S. Beck and Dr. Francine Broder wrote an important contribution to the Beck Institute blog giving good reason for a move away from the “H” word in practice.

When developing Cognitive Therapy, Dr. Aaron T. Beck was inspired by existing therapies, including behavior therapy, wherein the educative model to generate clinically meaningful change had been adopted. The inclusion of homework as a crucial feature of Cognitive Therapy made perfect sense 1 . Homework is a collaborative endeavor. It is also ideally empirical and can help to promote the reappraisal of key cognitions 2 .

Asking clients to engage with therapeutic tasks between sessions, in a form of action plan has been subject to more empirical study than any other process in CBT 3 . However, the evidence supporting homework is almost wholly derived from dismantling studies that contrast CBT with CBT without homework, or correlational studies of homework adherence and symptom reduction. Findings from our most recent meta-analysis suggest that homework quantity and quality have little difference in their relations with outcome 4 . As clinicians, we can take from this that we should use homework consistently and be especially encouraged when clients engage with tasks 5 .

However, if we try to seriously answer Jerry’s question above, we have to ask ourselves another important question – what are we actually really interested in with CBT homework?

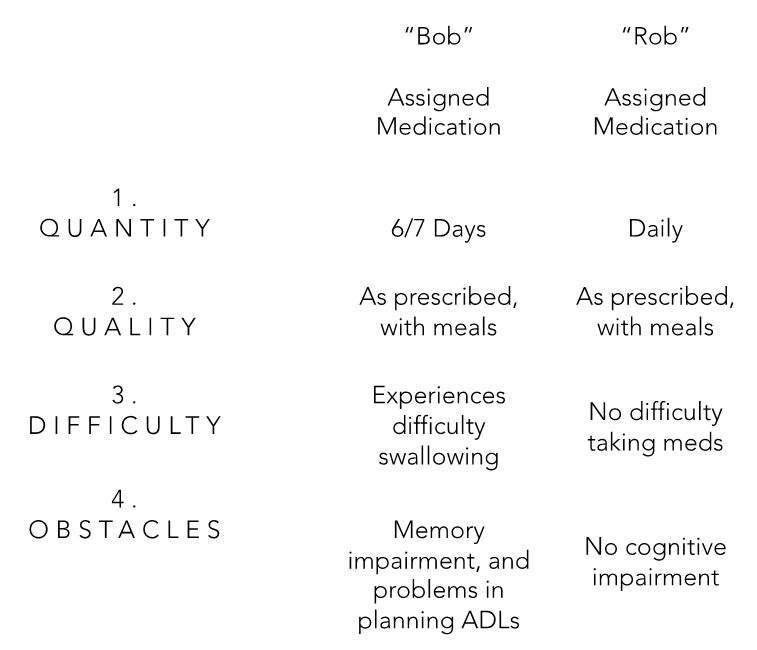

Current definitions of homework adherence have been derived from the literature on pharmacotherapy, and that might be the source of the problem. Take our two client examples below, Bob and Rob. Both have been prescribed a daily medication script, and if we look at the quantity of what was “done,” Rob looks more “adherent” than Bob.

However, when we take into account the cognitive impairment that Bob has, as well as his capacity to swallow medication following a head injury, then his 6/7 days’ worth of adherence is particularly noteworthy. Of course, in CBT, the content of homework varies on a weekly basis, and is tailored for the client in its design and plan. Therefore, the scope for subjective views of difficulty, and array of unique practical barriers is considerable. Thus, if we are genuinely interested in “engagement,” we need to take into account the inherent difficulties of the homework and practical obstacles to it for each individual client, at each session 6 .

Dr. Judith Beck’s earliest teachings emphasize the importance of the client’s subjective evaluation of homework. Those who are depressed are less likely to recognize their achievements, those with anxiety presentations often have negative predictions about its utility or their ability to carry it out, and many clients abandon the task when encountering obstacles. Those with pervasive interpersonal difficulties often have their core beliefs triggered in carrying out the action plan. When they do, they may experience intense negative emotion, viewing themselves and/or their therapist negatively. The working alliance may become strained. Dr. Beck has also advocated for use of the cognitive case conceptualization to understand clients’ patterns of engagement and anticipate problems of this nature 7-8 .

Fortunately, the research underpinning CBT homework is moving towards more clinically meaningful studies. Therapist skill in using homework has been shown to predict outcomes 9-10 , and recently a study found that greater consistency of homework with the therapy session resulted in more adherence. 11 Our Cognitive Behavior Therapy Research Lab (currently based at the Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health at Monash University) is centrally focused on how clients’ adaptive beliefs about homework strengthen their sense of self-efficacy in engaging in homework tasks, despite the difficulties and obstacles they experience. Thus, for several reasons, we can be optimistic that the evidence for homework is an example of how a bridge between science and practice is being built on solid foundations.

A half century after the first practice guide for Cognitive Therapy was published (Beck et al, 1979), we can be curious in the personal meaning our clients attribute to the action plan. How do beliefs about coping and change affect engagement? Are there important maladaptive assumptions and compensatory strategies that might make it difficult for the client to engage? How does the task align with the client’s values? What might be the pros and cons to the client in choosing not to engage? It’s important to focus less on trying to achieve perfect – or even a close approximation of perfect – “adherence” and to focus more on facilitating engagement. An empathic understanding of challenges clients face completing the homework tasks will better equip us to design and plan future homework. Rather than a focus on “compliance,” let us inspire our clients to tolerate the discomfort and uncertainty in their homework. Let us also celebrate in their discovery of new ideas and perspectives that homework brings.

Nikolaos Kazantzis, PhD is Editor of “Using Homework Assignments in Cognitive Behavior Therapy” (2 nd edition), currently in preparation with Routledge publishers of New York.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression . New York: Guilford Press.

- Kazantzis, N., Dattilio, F. M., & Dobson, K. A. (2017). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive behavioral therapy: A clinician’s guide. New York: Guilford.

- Kazantzis, N., Luong, H. K., Usatoff, A. S., Impala, T., Yew, R. Y., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). The processes of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42 (4), 349-357. doi: 10.1007/s10608-018-9920-y

- Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C. J., Zelencich, L., Norton, P. J., Kyrios, M., & Hofmann, S. G. (2016). Quantity and quality of homework compliance: A meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47 , 755-772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.002

- Callan, J. A., Kazantzis, N., Park, S. Y., Moore, C., Thase, M. E., Emeremni, C. A., Minhajuddin, A., Kornblith, S., & Siegle, G. J. (2019). Effects of cognitive behavior therapy homework adherence on outcomes: Propensity score analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50 (2), 285-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.05.010

- Holdsworth, E., Bowen, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. (2014). Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 34 (5), 428–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive therapy for challenging problems: What to do when the basics don’t work . New York: Guilford.

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

- Weck, F., Richtberg, S., Esch, S., Hofling, V., & Stangier, U. (2013). The relationship between therapist competence and homework compliance in maintenance cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Behavior Therapy, 44 (1), 162–172. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2012.09.004

- Conklin, L. R., Strunk, D. R., & Cooper, A. A. (2018). Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42 (1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9873-6

- Jensen, A., Fee, C., Miles, A. L., Beckner, V. L., Owen, D., & Persons, J. B. (in press). Congruence of patient takeaways and homework assignment content predicts homework compliance in psychotherapy. Behavior Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.005

10 September 2024: Due to technical disruption, we are experiencing some delays to publication. We are working to restore services and apologise for the inconvenience. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist

- > Volume 8

- > Homework in therapy: a case of it ain't what you do,...

Article contents

Homework in therapy: a case of it ain't what you do, it's the way that you do it.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 August 2015

It is argued, illustrated by a case example, that homework quality and end of therapy outcomes can be positively affected when ideas of compassion and attention to individual frames of reference are considered. It is suggested that by exploring the affect experienced when completing tasks and being mindful of client learning (i.e. the zone of proximal development), engagement and emotional connection with homework increase.

Access options

Follow-up reading.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Duncan L. Harris (a1) (a2) and Syd Hiskey (a2)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X15000549

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Do You Need a Homework Therapist?

By Natalie Proulx

- April 5, 2018

How do you feel about homework? Do you find it helps you learn more? Is it ever enjoyable, or does it only stress you out? Why?

In “ Homework Therapists’ Job: Help Solve Math Problems, and Emotional Ones ,” Kyle Spencer writes:

On a recent Sunday, Bari Hillman, who works during the week as a clinical psychologist at a New York mental health clinic, was perched at a clear, plastic desk inside a 16-year-old’s Manhattan bedroom, her shoeless feet resting on a fluffy white rug. Dr. Hillman was helping a private school sophomore manage her outsize worry over a long-term writing project. The student had taped the project outline on the wall above the desk, at Dr. Hillman’s prodding. It was designed to serve both as a reminder that the project was due, and an empowering indicator of progress. Dr. Hillman mused about the way worry can morph into unhealthy avoidance, the cathartic power of deep breathing and the soothing nature of to-do lists. Dr. Hillman, 30, represents a new niche in the $100 billion tutoring industry. Neither a traditional tutor nor a straight-up therapist, she is an amalgam of the two. “Homework therapists,” as they are now sometimes called, administer academic help and emotional support as needed. Via Skype, email and text, and during pricey one-on-one sessions, they soothe cranky students, hoping to steer them back to the path of achievement. The service is not cheap. Parents in New York generally pay between $200 and $600 for regularly scheduled in-person sessions that range from 50 to 75 minutes. This on top of the hefty fees New York mothers and fathers already pay to help their children get ahead, or just stay on pace, from coaching for kindergarten gifted and talented tests, to subject tutoring, SAT prep and help with writing their college essays. Tutors make themselves available for last-minute interventions before midterms or when writing projects are due. They respond to texts and emails and often send their own, nudging students to finish a homework assignment or stay positive before and during a big exam. Some have teenagers create playlists on Spotify that express their feelings about homework. Others hand out blobs of scented putty, known as therapy dough, that is designed to calm. Others use meditation and mindfulness to refocus their charges on the hunt for a 4.0 and higher SAT scores.

Students: Read the entire article, then tell us:

— Do you ever feel overwhelmed by homework and studying? If so, what strategies do you have for dealing with the pressure? Are there any ideas from the article that you could use when doing homework in the future?

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

The Role of Homework Engagement, Homework-Related Therapist Behaviors, and Their Association with Depressive Symptoms in Telephone-Based CBT for Depression

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 22 July 2020

- Volume 45 , pages 224–235, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Elisa Haller 1 &

- Birgit Watzke 1

13k Accesses

19 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy (tel-CBT) ascribes importance to between-session learning with the support of the therapist. The study describes patient homework engagement (HE) and homework-related therapist behaviors (TBH) over the course of treatment and explores their relation to depressive symptoms during tel-CBT for patients with depression.

Audiotaped sessions (N = 197) from complete therapies of 22 patients (77% female, age: M = 54.1, SD = 18.8) were rated by five trained raters using two self-constructed rating scales measuring the extent of HE and TBH (scored: 0–4).

Average scores across sessions were moderate to high in both HE ( M = 2.71, SD = 0.74) and TBH ( M = 2.1, SD = 0.73). Multilevel mixed models showed a slight decrease in HE and no significant decrease in TBH over the course of treatment. Higher TBH was related to higher HE and higher HE was related to lower symptom severity.

Conclusions

Results suggest that HE is a relevant therapeutic process element related to reduced depressive symptoms in tel-CBT and that TBH is positively associated with HE. Future research is needed to determine the causal direction of the association between HE and depressive symptoms and to investigate whether TBH moderates the relationship between HE and depressive symptoms.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02667366. Registered on 3 December 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Homework Completion via Telephone and In-Person Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Among Latinos

Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression.

Mediators and Moderators of Homework–Outcome Relations in CBT for Depression: A Study of Engagement, Therapist Skill, and Client Factors

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Therapeutic homework in terms of inter-session activity presents a central component of psychotherapy and is particularly inherent to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Beck et al. 1979 ). The core principle of this treatment is to equip patients with tools to change thoughts, behaviors, emotions, and their interplay. Homework may be defined as activities carried out between sessions in order to practice skills outside of therapy and to generalize to the natural environment (Kazantzis and L’Abate 2007 ; Lambert et al. 2007 ). Rather than exclusively discussing problems in an isolated setting, patients are encouraged to address the problem in their everyday life with the intention to produce and maintain a therapeutic effect (Lambert et al. 2007 ). The theorized mechanisms of the effect of homework build upon the skills-building approach of CBT (Beck et al. 1979 ; Detweiler and Whisman, 1999 ), as therapeutic exercises provide an opportunity for the patient to gather information and practice newly gained skills. Ultimately, practicing skills outside therapy helps becoming aware of the problem and consolidating new beliefs and behaviors (Beck et al. 1979 ). Homework thus serves as a means of transferring strategies outside the therapy context and enables the patient to practice new skills in real-life situations in order to maintain therapeutic gain (Kazantzis and Ronan 2006 ).

Homework is a commonly studied process variable in CBT and has empirically been investigated primarily in association with treatment outcome. Previous research has demonstrated that a high level of homework compliance is related to improvements in depressive symptoms (e.g., Kazantzis et al. 2010 ). Meta-analyses have established correlational evidence for the homework compliance and outcome relationship (e.g., Mausbach et al. 2010 ) as well as experimental evidence for the superiority of treatments that incorporate homework over treatments without homework (Kazantzis et al. 2010 , 2016 ).

It has previously been noted that an “evidence-based” assessment of homework compliance (Dozois 2010 , p. 158) requires the consideration of qualitative aspects of homework completion throughout the course of the treatment (Dozois 2010 ; Kazantzis et al. 2010 , 2017 ). This has been neglected in previous studies on the homework-outcome relationship, which rely solely on adherence or compliance measures that focus on the proportion of completed homework or global single-item measures of whether the patient attempted the homework or not (e.g., Bryant et al. 1999 ; Aguilera et al. 2018 ). In a recent systematic review of homework adherence assessments in major depressive disorder (MDD), Kazantzis et al. ( 2017 ) found that only 2 out of 25 studies reported the measures that addressed the quality of homework completion. Furthermore, the single-item Assignment Compliance Rating Scale (ACRS; Primakoff et al. 1986 ) does not capture the depth of HE and the Homework Rating Scale (HRS; Kazantzis et al. 2004 ) is a client self-report measure, which might over- or underestimate homework compliance compared to objective measures. Studies increasingly put effort on focusing on qualitative aspects of homework completion. For this reason, the term and concept of homework engagement (HE) has been deemed relevant: it refers to the extent to which a patient has completed homework in an elaborate and clinically meaningful manner (Dozois 2010 ; Conklin and Strunk 2015 ). Furthermore, less empirical attention has been paid to underlying mechanisms going beyond patient factors, including therapist behaviors influencing HE and their relation to depressive symptoms.

Homework-Related Therapist Behaviors

Theoretical considerations and clinical recommendations of therapist behaviors related to homework (TBH) mainly build on four strategies suggested by Beck et al. ( 1979 ): (1) Homework should be described clearly and should be specific; (2) homework should be assigned with a cogent rationale; (3) patients’ reactions and should be elicited and in order to troubleshoot difficulties; (4) progress should be summarized when reviewing homework. Expert clinicians have also pointed out the value of formulating simple and feasible homework tasks and emphasized the patient involvement when developing homework assignments that are agreeable to the patient (Kazantzis et al. 2003 ; Tompkins 2002 ). Moreover, factors such as the match between the assignment and the client, as well as the wording of the homework task should be considered (Detweiler and Whisman 1999 ).

The suggested domains have also received some empirical attention. To our knowledge, four studies have focused on TBH in face-to-face treatment of MDD, which provide inconsistent findings. First, Startup and Edmonds ( 1994 ) investigated whether patient ratings of therapist behaviors promoting homework compliance were associated with therapist-rated homework compliance in a sample of 25 patients. The results did not demonstrate a significant relation between any facet of TBH (providing rationale, clear description, anticipation of problems, involving the patient) and homework compliance, which was largely attributed to ceiling effects of the patients’ ratings of TBH. Second, Bryant et al. ( 1999 ) assessed observer-rated homework compliance and TBH (reviewing previous assignment, providing rationale, clearly assigning and tailoring, seeking reactions and troubleshooting problems) in 26 depressed patients receiving cognitive therapy (CT). The study confirmed that patients that are more compliant experienced greater symptom improvement, and demonstrated a non-significant trend that suggests a relation between the overall score of the therapist homework behavior scale and homework compliance. Item-based analyses, however, demonstrated that therapist reviewing (TBH-R), but not therapist assigning behavior (TBH-A), was related to homework compliance. Third, in a sample of adolescents with depression, Jungbluth and Shirk ( 2013 ) demonstrated that providing a strong rationale and allocating more time in the beginning of treatment predicted greater homework compliance in the subsequent session, especially for initially resistant individuals. Fourth, the most recent study, conducted by Conklin et al. ( 2018 ), evaluated three classes of TBH in a sample of 66 patients with MDD undergoing CT. The authors reported that TBH-A, but not TBH-R were predictive of HE in the early sessions of CT, which stands in contrast to the findings of Bryant et al. ( 1999 ).

In consideration of the therapist’s prominent role in making use of therapeutic homework and the available inconclusive findings, the contribution of TBH to HE and their relation to depressive symptoms needs further exploration.

Homework Engagement in Telephone-Based CBT