Understanding psychotherapy and how it works

Learn how to choose a psychologist, how therapy works, how long it lasts, and what should and shouldn’t happen during psychotherapy

- Psychotherapy

Do you ever feel too overwhelmed to deal with your problems? If so, you’re not alone.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health , more than a quarter of American adults experience depression, anxiety, or another mental disorder in any given year. Others need help coping with a serious illness, losing weight, or stopping smoking. Still others struggle to cope with relationship troubles, job loss, the death of a loved one, stress, substance abuse, or other issues. And these problems can often become debilitating.

What is psychotherapy?

A psychologist can help you work through such problems. Through psychotherapy, psychologists help people of all ages live happier, healthier, and more productive lives.

In psychotherapy, psychologists apply scientifically validated procedures to help people develop healthier, more effective habits. There are several approaches to psychotherapy—including cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal, and other kinds of talk therapy—that help individuals work through their problems.

Psychotherapy is a collaborative treatment based on the relationship between an individual and a psychologist. Grounded in dialogue, it provides a supportive environment that allows you to talk openly with someone who’s objective, neutral, and nonjudgmental. You and your psychologist will work together to identify and change the thought and behavior patterns that are keeping you from feeling your best.

By the time you’re done, you will not only have solved the problem that brought you in, but you will have learned new skills so you can better cope with whatever challenges arise in the future.

When should you consider psychotherapy?

Because of the many misconceptions about psychotherapy , you may be reluctant to try it out. Even if you know the realities instead of the myths, you may feel nervous about trying it yourself.

Some people seek psychotherapy because they have felt depressed, anxious, or angry for a long time. Others may want help for a chronic illness that is interfering with their emotional or physical well-being. Still others may have short-term problems they need help navigating. They may be going through a divorce, facing an empty nest, feeling overwhelmed by a new job, or grieving a family member’s death, for example.

Signs that you could benefit from therapy include:

- You feel an overwhelming, prolonged sense of helplessness and sadness

- Your problems don’t seem to get better despite your efforts and help from family and friends

- You find it difficult to concentrate on work assignments or to carry out other everyday activities

- You worry excessively, expect the worst, or are constantly on edge

- Your actions, such as drinking too much alcohol, using drugs, or being aggressive, are harming you or others

What are the different kinds of psychotherapy?

There are many different approaches to psychotherapy. Psychologists generally draw on one or more of these. Each theoretical perspective acts as a roadmap to help the psychologist understand their patients and their problems and develop solutions.

The kind of treatment you receive will depend on a variety of factors: current psychological research, your psychologist’s theoretical orientation, and what works best for your situation.

Your psychologist’s theoretical perspective will affect what goes on in his or her office. Psychologists who use cognitive-behavioral therapy, for example, have a practical approach to treatment. Your psychologist might ask you to tackle certain tasks designed to help you develop more effective coping skills. This approach often involves homework assignments.

Your psychologist might ask you to gather more information, such as logging your reactions to a particular situation as they occur. Or your psychologist might want you to practice new skills between sessions, such as asking someone with an elevator phobia to practice pushing elevator buttons. You might also have reading assignments so you can learn more about a particular topic.

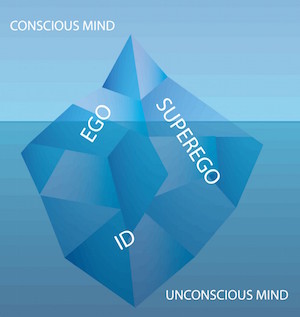

In contrast, psychoanalytic and humanistic approaches typically focus more on talking than doing. You might spend your sessions discussing your early experiences to help you and your psychologist better understand the root causes of your current problems.

Your psychologist may combine elements from several styles of psychotherapy. In fact, most therapists don’t tie themselves to any one approach. Instead, they blend elements from different approaches and tailor their treatment according to each patient’s needs.

The main thing to know is whether your psychologist has expertise in the area you need help with and whether your psychologist feels he or she can help you.

Finding a psychologist

Once you’ve decided to try psychotherapy, you need to find a psychologist.

Why choose a psychologist for psychotherapy?

Psychologists who specialize in psychotherapy and other forms of psychological treatment are highly trained professionals with expertise in mental health assessment, diagnosis, and treatment, and behavior change.

After graduating from a four-year undergraduate college or university, psychologists spend an average of seven years in graduate education and training to earn a doctoral degree. That degree may be a PhD, PsyD or EdD.

Psychologists pass a national examination and must be licensed by the state or jurisdiction in which they practice. Licensure laws are intended to protect the public by limiting licensure to those who are qualified to practice psychology as defined by state law. Most states also require psychologists to stay up-to-date by earning several hours of continuing education credits annually.

In addition, APA members adhere to a strict code of professional ethics.

How do I find a psychologist?

If you plan to use your insurance or employee assistance program to pay for psychotherapy, you may need to select a psychologist who is part of your insurance plan or employee assistance program. But if you’re free to choose, there are many ways to find a psychologist:

- Ask trusted family members and friends.

- Ask your primary care physician, obstetrician/gynecologist, pediatrician, or another health professional. If you’re involved in a divorce or other legal matters, your attorney may also be able to provide referrals.

- Search online for psychologists’ websites.

- Contact your area community mental health center.

- Consult a local university or college department of psychology.

- Call your local or state psychological association , which may have a list of practicing psychologists organized by geographic area or specialty.

Or use a trusted online directory, such as APA’s Psychologist Locator service . This service makes it easy for you to find practicing psychologists in your area.

Psychologists may work in their own private practice or with a group of other psychologists or health care professionals. Practicing psychologists also work in schools, colleges and universities, hospitals, health systems and health management organizations, veterans’ medical centers, community health and mental health clinics, businesses and industry, and rehabilitation and long-term care centers.

Selecting a psychologist

APA estimates that there are about 85,000 licensed psychologists in the United States. How can you find the one who’s right for you?

Psychologists and patients work together, so the right match is important. Good “chemistry” with your psychologist is critical, so don’t be afraid to interview potential candidates about their training, clinical expertise, and experience treating problems like yours. Whether you interview a psychologist by phone, during a special 15-minute consultation, or at your first session, look for someone who makes you feel comfortable and inspires confidence.

But it’s also important to check more practical matters, too.

What should you ask yourself?

When you’re ready to select a psychologist, think about the following points:

- Do you want to do psychotherapy by yourself, with your partner or spouse, or with your children?

- What are your main goals for psychotherapy?

- Will you use your health insurance or employee assistance program to pay for psychotherapy?

- If you’ll be paying out of pocket, how much can you afford?

- How far are you willing to drive?

- What days and times would be convenient?

What should you ask a psychologist?

You’ll need to gather some information from the psychologists whose names you have gathered.

The best way to make initial contact with a psychologist is by phone. While you may be tempted to use email, it’s less secure than the telephone when it comes to confidentiality. A psychologist will probably call you back anyway. And it’s faster for everyone to talk rather than have to write everything down.

Psychologists are often with patients and don’t always answer their phones right away. Just leave a message with your name, phone number, and brief description of your situation.

Once you connect, some questions you can ask a psychologist are:

- Are you accepting new patients?

- Do you work with men, women, children, teens, couples, or families? (Whatever group you are looking for.)

- Are you a licensed psychologist in the state where I live?

- How many years have you been practicing?

- What are your areas of expertise?

- Do you have experience helping people with symptoms or problems like mine?

- What is your approach to treatment? Have the treatments you use been proven effective for dealing with my problem?

- What are your fees? Do you have a sliding-scale policy if I can’t afford your regular fees? Do you accept credit cards or personal checks? Do you expect payment at the time of service?

- Do you accept my insurance? Are you affiliated with any managed care organizations? Do you accept Medicare or Medicaid?

- Will you accept direct billing to or payment from my insurance company?

- What are your policies concerning things like missed appointments?

If you have particular concerns that are deal-breakers for you, ask the psychologist about them. You might want to work with a psychologist who shares your religious views or cultural background, for example. While some psychologists are more open to disclosing personal information than others, the response will give you important information about whether you’ll work well together.

While you’re assessing a psychologist, he or she will also be assessing you. To ensure that psychotherapy is successful, the psychologist must determine whether there’s a good match when it comes to personality as well as professional expertise. If the psychologist feels the fit isn’t right—perhaps because you need someone with a different specialty area—he or she will refer you to another psychologist who can help.

Getting started

How can i pay for psychotherapy.

If you have private health insurance or are enrolled in a health maintenance organization or other type of managed care plan, it may cover mental health services such as psychotherapy. Before you start psychotherapy, you should check with your insurance plan to see what is covered.

Thanks to the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 , group insurers of more than 50 employees that offer mental health and substance use services must cover both mental and physical health equally. That means insurers are no longer allowed to charge higher copays or deductibles for psychological services or arbitrarily limit the number of psychotherapy sessions you can receive.

However, insurance companies vary in terms of which mental health conditions they cover. That means some insurance policies may not cover certain mental health disorders.

Government-sponsored health care programs are another potential source of mental health services. These include Medicare for people age 65 and older and people with disabilities, as well as health insurance plans for military personnel and their dependents. In some states, Medicaid programs may also cover mental health services provided by psychologists.

Other options include community mental health centers, free clinics, religious organizations, and university and medical center training programs. These groups often offer high-quality services at low cost.

What should I ask my insurance company?

Look on the back of your insurance card for a phone number for mental or behavioral health or call your insurance company’s customer service number. Before your first psychotherapy appointment, ask your insurer the following questions:

- Does my plan cover mental health services?

- Do I have a choice about what kind of mental health professionals I can see? Ask whether your plan covers psychologists and what kinds of treatments are covered and excluded.

- Is there a deductible? In some plans, you have to pay a certain amount yourself before your benefits start paying. Also ask how much the deductible is, what services count toward your deductible and when your deductible amount starts over again. Some deductibles re-set at the first of the year, for example, while others re-set at the beginning of your employer’s fiscal year.

- What is my copayment? Your plan probably requires you to pay for part of treatment yourself by paying either a set amount or a percentage of the fee directly to your psychologist for each treatment session.

- Is there a limit to the number of sessions? Unlike group or employer-based insurance that must provide mental health parity, private insurance does not. It may only be willing to pay for a certain number of sessions.

Making your first appointment

You may feel nervous about contacting a psychologist. That anxiety is perfectly normal. But having the courage to overcome that anxiety and make a call is the first step in the process of empowering yourself to feel better. Just making a plan to call and sticking to it can bring a sense of relief and put you on a more positive path.

Psychologists understand how difficult it can be to make initial contact. The first call is something new for you, but it’s something they handle regularly. Leave a message with your name, your contact number, and why you are calling. It’s enough to just say that you are interested in knowing more about psychotherapy. Once your call is returned, they’ll lead a brief conversation to get a better sense of what you need, whether they are able to help, and when you can make an appointment.

You might be tempted to take the first available appointment slot. Take a few minutes to stop and think before you do. If it does not fit with your schedule, you can ask if there are other times available that might fit better for you.

What factors should you consider?

You’ll need to think about the best time of day and week to see your psychologist. Factors to consider include:

- Your best time of day. Whether you’re a morning person or a night owl, know when you’re at your best and schedule your appointment accordingly.

- Work. If you have to take time off from work, ask your human resources department if you can use sick leave for your psychotherapy sessions. You might also want to schedule your first appointment later in the day so you don’t have to go back to work afterward. If you have an upsetting topic to discuss, you may be tired, emotionally spent, puffy-eyed, or distracted after your first session.

- Family responsibilities. Unless your children are participating in treatment, it’s usually not a good idea to bring them along. Choose a time when you will have child care available.

- Other commitments. A psychotherapy session typically lasts 45 to 50 minutes. Try to schedule your session at a time when you won’t have to rush to your next appointment afterward. Worrying about being late to your next commitment will distract you from your psychotherapy session.

How should I prepare for the appointment?

Once you’ve made an appointment, ask your psychologist how you should prepare. A psychologist might ask you to:

- Call your insurer to find out what your outpatient mental health benefits cover, what your copay is, and whether you have a deductible. If you don’t get this information ahead of time, your psychologist may ask you to come to your appointment a little early so he or she can help you verify your benefits.

- Fill out new patient paperwork for your psychologist. Your psychologist may have a website with forms you can download and fill out before you arrive at your appointment. If not, you can ask your psychologist to get you the forms and fill them out at home rather than while sitting in the psychologist’s waiting room. Your psychologist may also provide a packet of materials covering logistical issues, such as cancellation fees and confidentiality.

- Get records from other psychologists or health care providers you’ve seen.

- You may also want to prepare a list of questions, such as the average treatment duration, the psychologist’s feelings about medication, or good books on your issue.

- Learn about therapy. If any of your friends have done psychotherapy, ask them what it was like. Or read up on the subject. If you’ve had psychotherapy before, think about what you liked and didn’t like about your former psychologist’s approach.

- Keep an open mind. Even if you’re skeptical about psychotherapy or are just going because someone told you to, be willing to give it a try. Be willing to be open and honest so you can take advantage of this opportunity to learn more about yourself.

- Make sure you know where you’re going. Check the psychologist’s website or do a map search for directions to the psychologist’s office.

Going to your first appointment

It’s normal to feel nervous when you head off to your first psychotherapy appointment. But preparing ahead of time and knowing what to expect can help calm your nerves.

What should I bring?

A typical psychotherapy session lasts 45 to 50 minutes. To make the most of your time, make a list of the points you want to cover in your first session and what you want to work on in psychotherapy. Be prepared to share information about what’s bringing you to the psychologist. Even a vague idea of what you want to accomplish can help you and your psychologist proceed efficiently and effectively.

If you’re on any medications, jot down which medications and what dosage so your psychologist can have that information.

It can be difficult to remember everything that happens during a psychotherapy session. A notebook can help you capture your psychologist’s questions or suggestions and your own questions and ideas. Jotting a few things down during your session can help you stay engaged in the process.

Most people have more than a single session of psychotherapy. Bring your calendar so you can schedule your next appointment before you leave your psychologist’s office.

You’ll also need to bring some form of payment. If you’ll be using your health insurance to cover your psychotherapy, bring along your insurance card so your psychologist will be able to bill your insurer. (Some insurers require psychologists to check photo IDs, so bring that along, too.) If you’ll be paying for psychotherapy out of pocket, bring along a credit card, checkbook, or cash.

What should I expect?

For your first session, your psychologist may ask you to come in a little early to fill out paperwork if you haven’t already done so.

Don’t worry that you won’t know what to do once the session actually begins. It’s normal to feel a little anxious in the first few sessions. Psychologists have experience setting the tone and getting things started. They are trained to guide each session in effective ways to help you get closer to your goals. In fact, the first session might seem like a game of 20 questions.

Sitting face to face with you, your psychologist could start off by acknowledging the courage it takes to start psychotherapy. He or she may also go over logistical matters, such as fees, how to make or cancel an appointment, and confidentiality, if he or she hasn’t already done so by phone.

Your psychologist will also want to know about your own and your family’s history of psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, or similar issues. You’ll also explore how your problem is affecting your everyday life. Your psychologist will ask questions like whether you’ve noticed any changes in your sleeping habits, appetite or other behaviors. A psychologist will also want to know what kind of social support you have, so he or she will also ask about your family, friends and coworkers.

It’s important not to rush this process, which may take more than one session. While guiding you through the process, your psychologist will let you set the pace when it comes to telling your story. As you gain trust in your psychologist and the process, you may be willing to share things you didn’t feel comfortable answering at first.

Once your psychologist has a full history, the two of you will work together to create a treatment plan. This collaborative goal-setting is important, because both of you need to be invested in achieving your goals. Your psychologist may write down the goals and read them back to you so you’re both clear about what you’ll be working on. Some psychologists even create a treatment contract that lays out the purpose of treatment, its expected duration, and goals, with both the individual’s and psychologist’s responsibilities outlined.

At the end of your first session, the psychologist may also have suggestions for immediate action. If you’re depressed, for example, the psychologist might suggest seeing a physician to rule out any underlying medical conditions, such as a thyroid disorder. If you have chronic pain, you may need physical therapy, medication, and help for insomnia as well as psychotherapy.

By the end of the first few sessions, you should have a new understanding of your problem, a game plan, and a new sense of hope.

Undergoing psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is often referred to as talk therapy, and that’s what you’ll be doing as your treatment continues. You and your psychologist will engage in a dialogue about your problems and how to fix them.

What should I expect as I continue psychotherapy?

As your psychotherapy goes on, you’ll continue the process of building a trusting, therapeutic relationship with your psychologist.

As part of the ongoing getting-to-know-you process, your psychologist may want to do some assessment. Psychologists are trained to administer and interpret tests that can help to determine the depth of your depression, identify important personality characteristics, uncover unhealthy coping strategies such as drinking problems, or identify learning disabilities.

If parents have brought in a bright child who’s nonetheless struggling academically, for example, a psychologist might assess whether the child has attention problems or an undetected learning disability. Test results can help your psychologist diagnose a condition or provide more information about the way you think, feel and behave.

You and your psychologist will also keep exploring your problems through talking. For some people, just being able to talk freely about a problem brings relief. In the early stages, your psychologist will help you clarify what’s troubling you. You’ll then move into a problem-solving phase, working together to find alternative ways of thinking, behaving, and managing your feelings.

You might role-play new behaviors during your sessions and do homework to practice new skills in between. As you go along, you and your psychologist will assess your progress and determine whether your original goals need to be reformulated or expanded.

In some cases, your psychologist may suggest involving others. If you’re having relationship problems, for instance, having a spouse or partner join you in a session can be helpful. Similarly, an individual having parenting problems might want to bring his or her child in. And someone who has trouble interacting with others may benefit from group psychotherapy.

As you begin to resolve the problem that brought you to psychotherapy, you’ll also be learning new skills that will help you see yourself and the world differently. You’ll learn how to distinguish between situations you can change and those you can’t and how to focus on improving the things within your control.

You’ll also learn resilience, which will help you better cope with future challenges. A 2006 study of treatment for depression and anxiety , for example, found that the cognitive and behavioral approaches used in psychotherapy have an enduring effect that reduces the risk of symptoms returning even after treatment ends. Another study found a similar result when evaluating the long-term effects of psychodynamic psychotherapy .

Soon you’ll have a new perspective and new ways of thinking and behaving.

How can I make the most of psychotherapy?

Psychotherapy is different from medical or dental treatments, where patients typically sit passively while professionals work on them and tell them their diagnosis and treatment plans. Psychotherapy isn’t about a psychologist telling you what to do. It’s an active collaboration between you and the psychologist.

So be an active, engaged participant in psychotherapy. Help set goals for treatment. Work with your psychologist to come up with a timeline. Ask questions about your treatment plan. If you don’t think a session went well, share that feedback and have a dialogue so that the psychologist can respond and tailor your treatment more effectively. Ask your psychologist for suggestions about books or websites with useful information about your problems.

And because behavior change is difficult, practice is also key. It’s easy to fall back into old patterns of thought and behavior, so stay mindful between sessions. Notice how you’re reacting to things and take what you learn in sessions with your psychologist and apply it to real-life situations. When you bring what you’ve learned between sessions back to your psychologist, that information can inform what happens in his or her office to further help you.

Through regular practice, you’ll consolidate the gains you’ve made, get through psychotherapy quicker, and maintain your progress after you’re done.

Should I worry about confidentiality?

Psychologists consider maintaining your privacy extremely important. It is a part of their professional code of ethics. More importantly, it is a condition of their professional license. Psychologists who violate patient confidentiality risk losing their ability to practice psychology in the future.

To make your psychotherapy as effective as possible, you need to be open and honest about your most private thoughts and behaviors. That can be nerve-wracking, but you don’t have to worry about your psychologist sharing your secrets with anyone except in the most extreme situations.

If you reveal that you plan to hurt yourself or others, for example, your psychologist is duty-bound to report that to authorities for your own protection and the safety of others. Psychologists must also report abuse, exploitation, or neglect of children, the elderly, or people with disabilities. Your psychologist may also have to provide some information in court cases.

Of course, you can always give your psychologist written permission to share all or part of your discussions with your physician, teachers, or anyone else if you desire.

Psychologists take confidentiality so seriously that they may not even acknowledge that they know you if they bump into you at the supermarket or anywhere else. And it’s OK for you to not say hello either. Your psychologist won’t feel bad; he or she will understand that you’re protecting your privacy.

Understanding medication

In our quick-fix culture, people often hope a pill will offer fast relief from such problems as depression or anxiety. And primary care physicians or nurse practitioners—most people’s first contact when they have a psychological problem—are typically trained to prescribe medication. They don’t have the extensive training or the time to provide psychotherapy.

Is medication effective?

There are some psychological conditions, such as severe depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia, where medication is clearly warranted. But many other cases are less clear-cut.

Evidence suggests that in many cases, medication doesn’t always work. In a 2010 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association , for instance, researchers reviewed previous research on the effectiveness of antidepressants . They found that antidepressants did help people with severe cases of depression. For mild to moderate depression, however, the medication wasn’t any more effective than a placebo.

What’s more, medications don’t help you develop the skills you need to deal with life’s problems. Once you stop taking medication, your problems often remain or come back. In contrast, psychotherapy will teach you new problem-solving strategies that will also help you cope with future problems.

Do I need medication?

If you can function relatively well—meaning you can function well at work or school and have healthy relationships with family and friends—the answer is probably no. Psychotherapy alone can be very effective. Or you might just need a more balanced lifestyle—one that combines work, exercise, and social interactions.

Medication can be useful in some situations, however. Sometimes, people need medication to get to a point where they’re able to engage in psychotherapy. Medication can also help those with serious mental health disorders. For some conditions, combining psychotherapy and medication works best.

How can I get medication if I need it?

If you need medication, your psychologist will work with your primary care provider or a psychiatrist to ensure a coordinated approach to treatment that is in your best interest.

Five states, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, and New Mexico, have laws allowing licensed psychologists with advanced training to prescribe certain medications to treat emotional and mental health problems. In those states, the psychologists must have completed a specialized training program (often earning a master’s degree in psychopharmacology), passed an examination for prescribing, and be additionally licensed as prescribing psychologists.

Assessing psychotherapy’s effectiveness

Some people wonder why they can’t just talk about their problems with family members or friends. Psychologists offer more than someplace to vent. Psychologists have years of training and experience that help people improve their lives. And there is significant evidence showing that psychotherapy is a very effective treatment.

How does psychotherapy work?

Successful treatment is the result of three factors working together:

- Evidence-based treatment that is appropriate for your problem

- The psychologist’s clinical expertise

- Your characteristics, values, culture, and preferences

When people begin psychotherapy, they often feel that their distress is never going to end. Psychotherapy helps people understand that they can do something to improve their situation. That leads to changes that enhance healthy behavior, whether it’s improving relationships, expressing emotions better, doing better at work or school, or thinking more positively.

While some issues and problems respond best to a particular style of therapy, what remains critical and important is the therapeutic alliance and relationship with your psychologist.

What if psychotherapy doesn’t seem to be working?

When you began psychotherapy, your psychologist probably worked with you to develop goals and a rough timeline for treatment. As you go along, you should be asking yourself whether the psychologist seems to understand you, whether the treatment plan makes sense, and whether you feel like you’re making progress.

Keep in mind that as psychotherapy progresses, you may feel overwhelmed. You may feel more angry, sad, or confused than you did at the beginning of the process. That doesn’t mean psychotherapy isn’t working. Instead, it can be a sign that your psychologist is pushing you to confront difficult truths or do the hard work of making changes. In such cases, these strong emotions are a sign of growth rather than evidence of a standstill. Remember, sometimes things may feel worse before they get better.

In some cases, of course, the relationship between a patient and the psychologist isn’t as good as it should be. The psychologist should be willing to address those kinds of issues, too. If you’re worried about your psychologist’s diagnosis of your problems, it might be helpful to get a second opinion from another psychologist, as long as you let your original psychologist know you’re doing so.

If the situation doesn’t improve, you and your psychologist may decide it’s time for you to start working with a new psychologist. Don’t take it personally. It’s not you; it’s just a bad fit. And because the therapeutic alliance is so crucial to the effectiveness of psychotherapy, you need a good fit.

If you do decide to move on, don’t just stop coming to your first psychologist. Instead, tell him or her that you’re leaving and why you’re doing so. A good psychologist will refer you to someone else, wish you lucky, and urge you not to give up on psychotherapy just because your first attempt didn’t go well. Tell your next psychologist what didn’t work to help ensure a better fit.

Knowing when you’re done

You might think that undergoing psychotherapy means committing to years of weekly treatment. Not so.

How long should psychotherapy take?

How long psychotherapy takes depends on several factors: the type of problem or disorder, the patient’s characteristics and history, the patient’s goals, what’s going on in the patient’s life outside psychotherapy, and how fast the patient is able to make progress.

Some people feel relief after only a single session of psychotherapy. Meeting with a psychologist can give a new perspective, help them see situations differently, and offer relief from pain. Most people find some benefit after a few sessions, especially if they’re working on a single, well-defined problem and didn’t wait too long before seeking help.

Other people and situations take longer—maybe a year or two—to benefit from psychotherapy. They may have experienced serious traumas, have multiple problems, or just be unclear about what’s making them unhappy. It’s important to stick with psychotherapy long enough to give it a chance to work.

People with serious mental illness or other significant life changes may need ongoing psychotherapy. Regular sessions can provide the support they need to maintain their day-to-day functioning.

Others continue psychotherapy even after they solve the problems that brought them there initially. That’s because they continue to experience new insights, improved well-being, and better functioning.

How do I know when I’m ready to stop?

Psychotherapy isn’t a lifetime commitment.

In one classic study, half of psychotherapy patients improved after eight sessions. And 75% improved after six months.

You and your psychologist will decide together when you are ready to end psychotherapy. One day, you’ll realize you’re no longer going to bed and waking up worrying about the problem that brought you to psychotherapy. Or you will get positive feedback from others. For a child who was having trouble in school, a teacher might report that the child is no longer disruptive and is making progress both academically and socially. Together you and your psychologist will assess whether you’ve achieved the goals you established at the beginning of the process.

What happens after psychotherapy ends?

You probably visit your physician for periodic check-ups. You can do the same with your psychologist.

And don’t think of psychotherapy as having a beginning, middle and end. You can solve one problem, then face a new situation in your life and feel the skills you learned during your last course of treatment need a little tweaking. Just contact your psychologist again. After all, he or she already knows your story.

Of course, you don’t have to wait for a crisis to see your psychologist again. You might just need a “booster” session to reinforce what you learned last time. Think of it as a mental health tune-up.

The American Psychological Association gratefully acknowledges the assistance of June Ching, PhD; Angela Londoño-McConnell, PhD; Elaine Ducharme, PhD; Terry Gock, PhD; Bethe Lonning, PsyD; Nancy Molitor, PhD; Dianne Polowczyk, PhD; and Michael Ritz, PhD, in developing this material.

Related Reading

- Protecting your privacy: Understanding confidentiality

You may also like

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Psychotherapy: A World of Meanings

Despite a wealth of findings that psychotherapy is an effective psychological intervention, the principal mechanisms of psychotherapy change are still in debate. It has been suggested that all forms of psychotherapy provide a context which enables clients to transform the meaning of their experiences and symptoms in such a way as to help clients feel better, and function more adaptively. However, psychotherapy is not the only health care intervention that has been associated with “meaning”: the reason why placebo has effects has also been proposed to be a “meaning response.” Thus, it has been argued that the meaning of treatments has a central impact on beneficial (and by extension, negative) health-related responses. In light of the strong empirical support of a contextual understanding of psychotherapy and its effects, the aim of this conceptual analysis is to examine the role of meaning and its transformation in psychotherapy—in general—and within three different, commonly used psychotherapy modalities.

Introduction

Psychotherapy is an effective psychological intervention for a multitude of psychological, behavioral, and somatic problems, symptoms, and disorders and thus rightfully considered as a main approach in mental and somatic health care management ( Prince et al., 2007 ; Goldfried, 2013 ). But despite the wealth of empirical findings, the principal mechanisms of psychotherapy change are still in debate ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ). Two rival models have been contested ever since the very beginning of psychotherapy research, when some 80 years ago Saul Rosenzweig wondered, “whether the factors alleged to be operating in a given therapy are identical with the factors that actually are operating and whether the factors that actually are operating in several different therapies may not have much more in common than have the factors alleged to be operating.” ( Rosenzweig, 1936 , p. 412). Rosenzweig questioned the common understanding of psychotherapy, in which it is assumed that specific techniques have specific effects. This proposition was later elaborated through the work of Jerome Frank who argued that all forms of psychotherapy provide a context which enables patients to transform the meaning of their experiences and symptoms in such a way as to help them to feel better, function more favorably, and think more adaptively ( Frank, 1986 ).

Interestingly and central to this paper, psychotherapy is not the only psychological intervention which has been associated with meaning. Following the assumption that “meaning responses are always there” ( Moerman, 2006 , p. 234)—i.e., in any medical and psychological treatment—the attribution of meaning has also been considered as an overarching mechanism for those treatment effects which placebo controls for in clinical trials. Thus, the attribution of a therapeutic meaning to a given intervention has a central impact on health-related responses ( Barrett et al., 2006 ).

The contextual model of psychotherapy remains topical ( Kirsch et al., 2016 ), and also controversial ( Marcus et al., 2014 ). The model has been developed to propose that it is the “common factors” (e.g., client-therapist relationship, clients’ expectations, trust, understanding, and expertise) across different versions of psychotherapy that explain their effectiveness (for details, see Wampold et al. (2011) ). The hypothesis for the general equivalence of various forms of psychotherapies is usually referred to as the dodo bird conjecture ( Rosenzweig, 1936 ). Hence, the contextual model of psychotherapy is markedly in contrast with the long-held assumption that specific methods are at the root of psychotherapy’s effects. The assumption that psychotherapy’s effects can be reduced to incidental—or contextual—constituents, which are typically called common or unspecific factors, has been a constant in psychotherapy research ( Luborsky et al., 2002 ; Gaab et al., 2016 ) but at least in terms of empirical evidence, there is sound reason and accumulating empirical support for a contextual understanding of psychotherapy ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ). For example, a number of meta-analyses showed that various bona fide psychotherapies, i.e., therapies with a clear treatment rationale but with very different underlying theories, aims, and methods appear to be equally effective ( Spielmans et al., 2007 ; Cuijpers et al., 2008 ; Barth et al., 2013 ; Frost et al., 2014 ). In addition, opposing treatment approaches with the same treatment rationale have shown to be equally effective in a trial on clients with panic disorder ( Kim et al., 2012 ) as much as similar treatments provided with opposing treatment rationales have shown to differ in their effects ( Tondorf et al., 2017 ).

Building on the strong empirical support for a contextual understanding of psychotherapy ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ), which proposes the transformation of meaning as its central mechanisms, the aim of this conceptual analysis is to examine the role of meaning and its transformation in psychotherapy in general and in three different and commonly used psychotherapy approaches.

In Search of a New Meaning

The main incentive to undergo a psychotherapy treatment is to change the general level of functioning, as well as to reduce the symptoms of suffering ( Strong and Matross, 1973 ). Clients’ belief that they are unable or incapable of solving disturbing problems contributes to demoralization and feelings of confusion, despair, and incompetence ( Vissers et al., 2010 ) or as Frank (1986) put it: “Often an important feature of demoralization is a sense of confusion resulting from the client’s inability to make sense out of his experiences or to control them, leading to the commonly expressed fear of going insane” (p. 341). This demoralization is not only a shared aspect of various psychological disorders, but can also be considered as a starting point for change in psychotherapy. Therapeutic change is thereby accompanied by clients “working through” their problems, gaining insight, achieving personal fulfillment, and becoming self-actualized, eventually transforming their problems and symptoms, self-perception, and experiences with their social environment ( Evans, 2013 ; Krause et al., 2015 ).

Frank (1986) stated that psychotherapy seeks to help clients to transform the meanings of their problems and symptoms and to overcome confusion with newly acquired clarity, i.e., by offering a narrative that links symptoms with hypothesized causes and providing a collaborative procedure for overcoming the suffering. Likewise, Wampold (2007) defined the core of psychotherapy in the transformation of non-adaptive explanations for their problems into new and more adaptive ones. Also, Dan Moerman ( Moerman, 2002 ) stated that “it sounds reasonable to me to say that psychotherapy evokes meaning responses” (p. 94) and that psychotherapy supports clients to create their stories and myths, although therapists are not considered a mandatory requirement for this ( Moerman, 2002 ). It should be noted that other mechanisms underlying positive response to psychotherapy have been proposed, e.g., reward mechanisms in psychotherapy ( Northoff and Boeker, 2006 ; Panksepp and Solms, 2012 ).

Considering processes of change in diverse interventions, narratives are thought to be created in order to render the demoralization less painful and promote remoralization ( Moerman, 2002 ). In this perspective, the therapists help their clients to give new meanings to their experiences or stories they tell, the language they use, and the beliefs they have ( Shaw, 2010 ).

Similar processes have been proposed to underlie placebo responses, which are “most likely to occur when the meaning of the illness experience is altered in a positive direction” ( Brody, 2000 ). These beneficial changes in meaning occur when three core conditions are present, which again resemble those proposed in the context of psychotherapy: (1) the clients feel listened to and receive a satisfactory, coherent explanation of their mental suffering and demoralization; (2) the client feels care and concern from the therapist; and (3) the clients feel an enhanced sense of mastery and control over their mental suffering (i.e., remoralization). A direct implementation can be seen in so-called narrative therapies, which are defined as “an approach that focuses on client stories with the goal of challenging existing meaning systems and creating more functional ones” ( Kropf and Tandy, 1998 ). Narrative approaches have come to a central role in systemic family therapy ( Carr, 1998 ; Wallis et al., 2011 ), emphasizing the role of language and how it affects the way clients frame their ideas of self and identity, while the therapist directly deals with clients’ concerns and the meaning of the worlds they live in ( Besley, 2002 ). Furthermore, it has been assumed that relying on the clients’ individual narratives is more significant than focusing on a pathological psychiatric diagnosis ( Gysin-Maillart et al., 2016 ). Of course, narrative therapies should not be mistaken as the exception of (dodo) rule, i.e., to be instances of “specific” therapies, but rather as possibilities to operationalize the rule in real life, i.e., to employ meaning processes in psychotherapy. Accordingly, it has been shown that meaning-making through language enhances clients’ well-being after a traumatic experience—which mainly stems from the connection, abstraction, and reflection of the whole experience ( Freda and Martino, 2015 ; Park et al., 2016 ).

Co-Construction of Narratives

To bring about these meaning transformations, psychotherapists mostly rely “on the use of words to form attitudes or induce actions” ( Frank, 1986 ). The overarching definition of a narrative is as a sequence of actions and events that involves a certain number of human beings as characters or actors ( Bruner, 1990 ). However, narratives differ from conventional discourse forms in variety of ways as narratives have an inherent sequentiality which is more than a just chronological sequence of lived experiences as it links the past to the present and future ( Bruner, 1990 ). A narrative creates a coherent whole out of a sequence of events ( Mattingly, 1994 ). In order to report an experience in a meaningful way, the protagonists not only focus on overt characteristics, but also reflect on their beliefs and feelings and how these are connected to their personal life in general ( Ochs and Capps, 1996 ). In regard to a broader social context, Justman (2011) argues that any information about a given intervention has an influence on the experience of clients receiving the intervention, which of course is particularly applicable for any form of psychotherapy.

In this understanding, any psychotherapy alleviates the symptoms of a target illness through meaning transformation. Thus, the relationship between narrative and illness—understood as the subjective experience of a given pathological process and their embedment in social context ( Engel, 1977 )—should briefly be exemplified. An illness narrative is defined as the important channel through which the meaning of an illness is created ( Kleinman, 1988 ). Thus, illness narratives do not merely reflect an illness experience, but they have been shown to be clinically relevant as they significantly impact on health behaviors and coping strategies as well as treatment outcomes ( Broadbent et al., 2004 ; Horne et al., 2007 ; Frenkel, 2008 ; Galli et al., 2010 ).

Furthermore, narratives are interdependent with the social context, so that therapists should use “images from the same sensory modality as that of the patient’s own imagery” ( Frank, 1986 ). The alternative narratives which are provided to the client in order to offer new and adaptive perspectives should be different but not too far off the client’s general beliefs ( Wampold, 2007 ) as much as exploring the clients’ narrative through attentive listening—both considered as key factors of healing processes ( Egnew, 2005 ; Mauksch et al., 2008 )—as they allow the therapist to reformulate and interpret the perceived meanings in a way that the clients can connect them with their personal conception of the world on the background of their beliefs and culture ( Strupp, 1986 ). Considering narratives in the psychotherapeutic encounter, the importance of the therapist’s and client’s co-construction of the narrative has been considered as a significant element of psychotherapy ( Brody, 1994 ) as jointly developed narratives significantly contribute to new forms of self-understanding and of being in the world ( Levitt et al., 2016 ). According to Brody (1994) , a shorter form of the client’s possible plea to the psychotherapist might be, “My story is broken; can you help me fix it?” (p. 85). Recovery in this understanding includes a deepening of a client’s experience and the development of a more comprehensive and coherent personal narrative ( Lysaker et al., 2011 ).

Truth Matters?

As outlined, the transformation of non-adaptive narratives into more adaptive ones is central to the contextual understanding of psychotherapy. This raises the question of the relationship between the narratives, i.e., their quality to induce subjective understanding, and the “real world,” i.e., the actual facts of a client’s life and actual causes of symptoms ( Kendler et al., 2011 ). Importantly, two kinds of narratives should be distinguished. First is the narrative behind the therapeutic approach, i.e., the healing narrative. Frank reasoned “that the chief criterion of the truth of any psychotherapeutic formulation is its plausibility” ( Frank, 1986 ). Hence, the explanation for why the treatment works should be plausible for both the therapist and the client. When the healing narrative is credible for the clients, they will discern and pick up on the aims and goals of therapy. Common factors associated with the healing narrative are for example the provision of an explanation for the client’s problems, therapeutic actions that are consistent with the explanation, as well as education ( Kirsch et al., 2016 ).

A second narrative is the client narrative that may emerge from therapy. This kind of narrative amounts to the actual change in the personal story, i.e., explanations that clients in therapy come to acquire about their own personality and reasons for their suffering. Common factors related with the client narrative are insight, corrective emotional experience, emotion regulation, and mindfulness among others ( Kirsch et al., 2016 ). Forming personal experiences into a narrative has further been associated with both physical and mental well-being and, accordingly, “psychotherapy is a more formal venue that often involves putting together a story” ( Pennebaker and Seagal, 1999 ). While this concept resonates with the now sadly predominant concept of “truthiness” (i.e., the quality of stating concepts or facts one wishes or believes to be true, rather than concepts or facts known to be true) in everyday life ( Metcalf, 2005 ), the understanding of plausibility in the context of a narrative is basically subjunctive or put otherwise: something is subjectively perceived to be possible ( Kleinman, 1988 ; Bruner, 1990 ). Further, this subjunctivity emphasizes that the anticipated future course is indispensably reported with some level of uncertainty, thus “to make a story good, it would seem, you must make it somewhat uncertain, somehow open to variant readings, rather subject to the vagaries of intentional states, undermined” ( Bruner, 1990 ). Likewise, Frank (1986) pointed out that “life histories do not provide adequate causal explanations of clients’ symptoms” (p. 343) and Jopling notes that “insights such as these may strike clients as entirely plausible and coherent, but neither plausibility nor coherence are, in themselves, a guarantee that the insights are true and that they fit the facts” ( Jopling, 2011 ). This corresponds with the idea that a client narrative emphasizes possibilities rather than predefined certainties ( Bruner, 2004 ) and that it not only copies reality as it is, but gives meaning to it through language ( Bruner, 1990 ). In turn, constructing the reality according to own beliefs and experiences affects as well as constitutes one’s self-perception. Accordingly, a client narrative is not only considered a personal report, but it also creates the identity of the story-teller ( Ricoeur, 1991 ). The self is reformed, which means that narrative and self are actually inseparable ( Ochs and Capps, 1996 ).

With these considerations in mind, the necessity of truth of an adaptive explanation for the client’s healing process comes into question. In this regard, it has been assumed that it might not be the truth itself that makes a narrative meaningful, yet rather its plausibility and “the extent to which a client is convinced by it” ( Frank, 1986 ). A plausible narrative for a mental disorder or a therapeutic change, respectively, invokes new information and is related to previous explanatory structures and networks of a client, when the new explanation is not too divergent from the previous one and takes a client’s perception of the world into account ( Wampold, 2007 ). Likewise, for clients who accept the treatment rationale, psychotherapeutic success occurs more quickly and psychotherapy outcomes are significantly better than for those who do not agree with the treatment rationale ( Addis and Jacobson, 2000 ; Overholser et al., 2010 ). However, the position that truth of a narrative is not the prerequisite for its meaningfulness does of course and in no way preclude psychotherapy and psychotherapists from the ethical obligations to respect clients’ autonomy. First, clients should not be deceived by providing false, but plausible narratives under any circumstances. Second, therapists should be aware to not withhold proven but possible implausible evidence about psychotherapy and psychotherapy change ( Blease et al., 2016 ; Gaab et al., 2016 ; Trachsel and Gaab, 2016 ).

Meaning Transformation in Psychotherapeutic Schools

Each psychotherapeutic school relies on a specific treatment theory, which addresses the connection between symptoms and hypothesized causes, as well as the process of therapeutic change. This treatment theory defines which treatment constituents are to be considered characteristic and which incidental ( Grünbaum, 1981 ). Although the various therapy approaches not only differ substantially in their operationalization of their constituents, but also in assignment to be either characteristic or incidental (e.g., the therapeutic alliance, Flückiger et al. (2012) ), they explicitly or implicitly promote a meaningful transformation regarding how clients understand and cope with their problems and symptoms, which in turn affects their self-perception and the interaction with their social environment. In the following, this shall be exemplified on three psychotherapeutic approaches. We decided to focus on three prominent psychotherapeutic approaches, with no claim to be complete in terms of therapeutic theories and methods. The following arguments guided our decision: first, the chosen psychotherapy approaches differ substantially in their underlying treatment theory; second, we decided to not focus on the link between psychodynamic psychotherapy with the “narrative feature of psychotherapy ‘which may be’ its main therapeutic engine” (cited from Blease, 2015 , p. 178) since this has been discussed elsewhere ( Jopling, 2011 ; Blease, 2015 ); third, popular third wave approaches (e.g., dialectical behavior therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy) conceptualize cognitions and cognitive thought processes as a way of “private behavior” ( Hayes et al., 2006 ), focusing primarily on the function of cognitions ( Churchill et al., 2010 ). We assume that the reflections on cognitive therapies will exhibit at least some comparable inferences.

Cognitive Therapies

The cognitive approach is based on the assumptions that the cognitive representation of clients’ experiences influences how they respond, act, and feel and that humans have the potential to metacognitize, thus to observe and change their thoughts and beliefs through reflection and practice, resulting in a different perception of one’s symptoms, self, and social environment ( Beck, 1996 ). The process of transformation through metacognition is embedded in a caring, collaborative, and respectful therapeutic relationship ( Alford et al., 1998 ; DeRubeis et al., 2001 ; Dobson and Dozois, 2001 ; Beck, 2005 ) and therapists should be competent not only in technical but also in interpersonal skills ( Beck and Padesky, 1989 ; Gaston et al., 1998 ).

The cognitive approach was initially formulated as a treatment for depression; later, it became very popular as an approach for treating a multitude of other mental disorders including anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorders. However, even from its early days, reception to cognitive therapy included the criticisms that the approach faced “formidable conceptual, methodological, and empirical difficulties” ( Coyne and Gotlib, 1983 ) and that “it has the force of a good story, and does not ask us to believe in any cognitive mechanism beyond those that have been familiar to playwrights and novelists for centuries.” ( Lang, 1988 ).

Interestingly, the conceptualization of clients’ cognitions soon developed from being a merely covert behavior or the result of erroneous information-processing to the notion that clients are constructors of their own representation of the world and that the reality is “a product of personal meanings that individuals create” ( Meichenbaum, 1993 ). As such the cognitive therapist “helps clients to construct narratives that fit their particular present circumstances, that are coherent, and that are adequate in capturing, and explaining their difficulties” ( Meichenbaum, 1993 ). Besides this kind of meaning, where the cognitive therapist and the client create meaningful narratives, there is also another kind: the meaningfulness or plausibility of the therapy itself. In an earlier publication, Don Meichenbaum—a major proponent of cognitive therapies—also addressed the supremacy of plausibility over validity stating that “although the theory (i.e., Schachter’s model of emotional arousal) and research upon which it is based have been criticized (…), the theory has an aura of plausibility that the clients tend to accept. The logic of the treatment plan is clear to clients in light of this conceptualization” ( Wampold and Imel, 2015 ).

Addressing the lack of differences in efficacy between cognitive and clearly non-cognitive treatments for panic disorder and the lack of a clear confirmation of the validity of underlying cognitive theories, Roth (2010) noted that “there is little doubt that therapists have been able to greatly help clients in spite of giving rationales that have turned out to be questionable or demonstrably false” ( Roth, 2010 ). In the same vein, it is interesting to note that although the hyperventilation theory (i.e., clients are instructed to counteract hyperventilation by breathing slowly and abdominally, which is expected to increase Pco₂) has been falsified as well as the suffocation false alarm theory (i.e., clients are thought to lower their Pco₂) is difficult to falsify ( Roth et al., 2005 ), treatments on the basis of these—interestingly opposing!—theories have been shown to be equally effective in the treatment of panic disorder ( Kim et al., 2012 ). As a solution of the ethical conundrum to provide effective therapies despite them being false or questionable, Roth (2010) referred to Williams James’ pragmatic approach ( James, 1896 ) and to “simply teach clients a practice that has prevented attacks in others (such as breathing control) but without its pseudoscientific rationale, asking clients to test whether that practice helps them as individuals.”

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy is based on the assumption that a system is constructed by shared representations of realities, building a consensus on how to interpret the internal and external environment ( Reiss and Olivieri, 1980 ) and that this collective perception is largely determined by the emotional experiences of the members of the given system. The pattern of meaning within a system is mediated by its use of language and its narrative tradition. Behaviors, symptoms, and expression of emotions are thus not considered as objective and independent entities, but rather as functional to the mutual relationships within a system and as constructed through the actions and communications of and between its members. Therefore, systemic therapy intends to change the shared patterns of meaning and definitions of realities in the context of the particular system, i.e., therapists aim to understand and accept the individual pattern of meaning as much as the systems’ narrative about their reality. Neutrality and unconditional therapeutic curiosity ( Cecchin, 1987 ), i.e., the therapist does not side or support individual members of a given system, are thought to encourage all involved members of a system to share ideas and problem perceptions, while subjective truths are appreciated in the same way. This attitude of neutrality is contrary to the idea that a system could be understood entirely, i.e., that “truth” exists, and thus attempts to explore the systems’ narratives ( Selvini et al., 1980 ).

The meaning-changing nature of systemic therapy shall be exemplified on the basis of a commonly used method in systematic therapy, the “genogram”, which consists of a structural diagram of a family’s generational relationship system using specific symbols for illustration ( Guerin and Pendagast, 1976 ). The “genogram” aims to unravel idiosyncratic perceptions, trigger the unfolding of shared narratives with a given system, and capture the communicative meaning of behavior, symptoms, or expression of emotions ( McGoldrick and Gerson, 1985 ). When relationship patterns become apparent and members of a given system are challenged to perceive reality by another perspective, this can result in new illness narratives and eventually new meanings ( Satir et al., 1991 ). Another approach in systemic therapy to change meaning is to reframe communication without changing its content ( Watzlawick et al., 2011 ). For example, the otherwise negatively and non-adaptive connoted behavior of acting-out is reframed as functional to make yourself heard in the context of a demanding and bullying school environment, thus transforming a formerly non-adaptive meaning of symptom into a new and more adaptive justification. Also, systemic therapy makes use of externalizing, i.e., to differentiate a problem and the identity of the client in order to enable a new context of meaning and to change the assumptions of what is driving and maintaining the problem ( White et al., 1990 ). According to De Shazer’ (1985) solution-focused approach, a system is viewed as having all resources that it needs for solving the problem but it is not using them currently. Thus, idiosyncratic meanings of a problem on the one hand are thought to underlie the presenting problems and on the other hand are also considered as the starting point for change: building new shared narratives involve all relevant members of the system and activate individual processes.

Person-Centered Therapy

The subjective experience of a person, i.e., the self-concept, is both the starting point as much as the therapeutic focus of the person-centered approach which is based on the principles of humanistic psychology. The person-centered approach originated in the works of Carl Rogers, who defined the necessary and sufficient condition for personality change ( Rogers, 1957 ). The self-concept is viewed as fluid and associated with changing idiosyncratic interpretations and attributions of subjective meanings. The driving force behind any change is the self-actualizing tendency for development, enhancement, and growth ( Rogers and Carmichael, 1951 ). Accordingly, a discrepancy between self-concept and the actual experience leads to incongruence, i.e., a state of tension and internal confusion, resembling Frank’s term demoralization ( Frank, 1986 ). This incongruence can either be the starting point for personality change and development or—in case of too large a discrepancy—be distorted, i.e., denied, biased, and not fully represented in experience.

The aim of person-centered therapy is congruence, i.e., to enable the clients to understand their own experiences and to be able to integrate them with their self-concept ( Rogers and Carmichael, 1951 ). A meaning transformation is understood as the clients revising their self-concept in a way to allow congruence with their experience ( Rogers, 1957 ). In this therapeutic process, the therapist is central and thus acknowledges the subjective experience of the client as much as specific techniques are only advocated when they “become a channel for communicating the essential conditions” (i.e., empathy, congruence and unconditional positive regard) (cited from Rogers, 1957 , p. 247). Thus, in person-centered therapy, the therapist and client construct a shared narrative as the therapist empathically understands the client’s inner representation of its experience and to carefully offer meanings to the client’s experience of which the client is scarcely aware ( Rogers, 1957 ).

Based on the contextual understanding of psychotherapy, we set out to examine the role and construction of meaning as a means to induce change in general and in three different psychotherapy approaches. The described psychotherapeutic approaches differ in their etiological assumptions and their therapeutic implications, but clearly all share the aim to promote a meaningful transformation in order to generate convincing narratives that “persuasively influence clients to accept more adaptive explanations for their disorders and take ameliorative actions” ( Wampold, 2007 ).

However, the exemplified approaches differ with regard to the extent this is communicated in both the treatment rationale and to the clients. Therefore, different kinds of psychotherapy can be distinguished by the way in which they explicitly engage and lead to transform clients’ meaning in more adaptive ways. Considering the importance of the transformation of meaning through narratives in psychotherapy and the varying degree this is openly defined as a characteristic constituent of the given approach and communicated to clients, we believe that psychotherapy would benefit from acknowledging this within education and training, and (arguably) in communicating this to clients.

The described therapeutic schools are all placed in an interpersonal context marked by empathy, warmth, cooperation, and transparency ( Langhoff et al., 2008 ). However, different emphases of the therapist’s and client’s roles are apparent. In cognitive therapies, the therapists assist their clients in constructing narratives that fit their perception of the world and their particular present challenges ( Meichenbaum, 1993 ). In systemic therapy, therapists aim to understand and accept how each member of a system understands reality and which unique narratives describe the current problem ( Selvini et al., 1980 ), while person-centered therapists promote a shared and empathetic understanding of clients’ narratives ( Rogers, 1957 ).

The current conceptual analysis has the limitation to focus only on a selective choice of therapeutic approaches, with no claim to be complete regarding therapeutic theories, rationales, techniques, and strategies ( Blease, 2015 ). However, the chosen psychotherapy approaches are illustrative as they differ significantly in focus, underlying treatment theory and paradigmatic orientation.

To conclude, the meaning and their underlying narratives matter—regardless of the specific psychotherapy approach. However, this importance is not equally well acknowledged by the examined approaches or to rephrase this observation in the terms of Grünbaum’s ( Grünbaum, 1981 ; Howick, 2017 ) definition of intervention constituents and with regard to Rosenzweig’s (1936) early and seminar observation: The characteristic factors that actually are operating in several different therapies—the transformation of meaning—may not have much more in common than have the factors alleged to be operating. The ethical obligation at hand is to make these characteristic elements of psychotherapy, which promote the change from non-adaptive into adaptive explanations, allowing the client to feel better, function more favorably, and think more adaptively, transparent in both, therapeutic manuals and the informed consent of clients ( Blease et al., 2016 ; Gaab et al., 2016 ; Trachsel and Gaab, 2016 ).

Author Contributions

CL, SM, and JG conceived and designed the conceptual analysis. CL drafted the paper. CL, SM, and JG wrote the final paper, critically revised the manuscript and gave important intellectual contribution to it.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Deborah Meier, Cora Wagner, Sarah Bürgler, and Linda Kost for their assistance with editing the manuscript. Further, we would like to thank Süheyla Seker for her conceptual contribution.

Funding. CL, PhD, received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF): P400PS_180730.

- Addis M. E., Jacobson N. S. (2000). A closer look at the treatment rationale and homework compliance in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression . Cognit. Ther. Res. 24 , 313–326. 10.1023/A:1005563304265 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alford B. A., Beck A. T., Jones J. V., Jr. (1998). The integrative power of cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrett B., Muller D., Rakel D., Rabago D., Marchand L., Scheder J. (2006). Placebo, meaning, and health . Perspect. Biol. Med. 49 , 178–198. 10.1353/pbm.2006.0019, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barth J., Munder T., Gerger H., Nuesch E., Trelle S., Znoj H., et al.. (2013). Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis . PLoS Med. 10 :e1001454. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T. (1996). “ Beyond belief: a theory of modes, personality, and psychopathology ” in Frontiers of cognitive therapy. ed. Salkovskis P. M. (New York: Guilford Press; ), 1–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T. (2005). The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective . Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 , 953–959. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Padesky C. A. (1989). Love is never enough. London: Penguin. [ Google Scholar ]

- Besley A. C. T. (2002). Foucault and the turn to narrative therapy . Br. J. Guid. Counc. 30 , 125–143. 10.1080/03069880220128010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blease C. R. (2015). “ Informed consent, the placebo effect and psychodynamic psychotherapy ” in New perspectives on paternalism and health care. ed. Schramme T. (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; ), 163–181. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blease C. R., Lilienfeld S. O., Kelley J. M. (2016). Evidence-based practice and psychological treatments: the imperatives of informed consent . Front. Psychol. 7 :1170. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01170 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blease C. R., Trachsel M., Holtforth M. G. (2016). Paternalism and placebos: the challenge of ethical disclosure in psychotherapy . Verhaltenstherapie 26 , 22–30. 10.1159/000442928 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Broadbent E., Petrie K. J., Ellis C. J., Ying J., Gamble G. (2004). A picture of health - myocardial infarction patients’ drawings of their hearts and subsequent disability- a longitudinal study . J. Psychosom. Res. 57 , 583–587. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.014, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brody H. (1994). “My story is broken, can you help me fix it?”: medical ethics and the joint construction of narrative . Lit. Med. 13 , 79–92. 10.1353/lm.2011.0169, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brody H. (2000). The placebo response - recent research and implications for family medicine . J. Fam. Pract. 49 , 649–654. PMID: . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruner J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruner J. (2004). Life as narrative . Soc. Res. 71 , 691–710. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr A. (1998). Michael White’s narrative therapy . Contemp. Fam. Ther. 20 , 485–503. 10.1023/A:1021680116584 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cecchin G. (1987). Hypothesizing, circularity, and neutrality revisited - an invitation to curiosity . Fam. Process 26 , 405–413. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1987.00405.x, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Churchill R., Moore T. H., Davies P., Caldwell D., Jones H., Lewis G., et al. (2010). Mindfulness-based ‘third wave’ cognitive and behavioural therapies versus treatment as usual for depression . The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 :CD008705. 10.1002/14651858.CD008705 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coyne J. C., Gotlib I. H. (1983). The role of cognition in depression - a critical appraisal . Psychol. Bull. 94 , 472–505. 10.1037/0033-2909.94.3.472, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuijpers P., van Straten A., Andersson G., van Oppen P. (2008). Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies . J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76 , 909–922. 10.1037/a0013075, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Shazer S. (1985). Keys to solution in brief therapy. New York: Ww Norton. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeRubeis R. J., Tang T. Z., Beck A. T. (2001). Cognitive therapy. New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dobson K., Dozois D. J. (2001). Historical and philosophical bases of the cognitive behavioral therapies. New York: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Egnew T. R. (2005). The meaning of healing: transcending suffering . Ann. Fam. Med. 3 , 255–262. 10.1370/afm.313, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Engel G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine . Science 196 , 129–136. 10.1126/science.847460, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans I. M. (2013). How and why people change: Foundations of psychological therapy. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flückiger C., Del Re A. C., Wampold B. E., Symonds D., Horvath A. O. (2012). How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis . J. Couns. Psychol. 59 , 10–17. 10.1037/a0025749, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank J. D. (1986). Psychotherapy - the transformation of meanings: discussion paper . J. R. Soc. Med. 79 , 341–346. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freda M. F., Martino M. L. (2015). Health and writing: meaning-making processes in the narratives of parents of children with leukemia . Qual. Health Res. 25 , 348–359. 10.1177/1049732314551059 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frenkel O. (2008). A phenomenology of the ‘placebo effect’: taking meaning from the mind to the body . J. Med. Philos. 33 , 58–79. 10.1093/jmp/jhm005, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frost N. D., Laska K. M., Wampold B. E. (2014). The evidence for present-centered therapy as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder . J. Trauma. Stress 27 , 1–8. 10.1002/jts.21881, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaab J., Blease C., Locher C., Gerger H. (2016). Go open: a plea for transparency in psychotherapy . Psychol. Conscious 3 , 175–198. 10.1037/cns0000063 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Galli U., Ettlin D. A., Palla S., Ehlert U., Gaab J. (2010). Do illness perceptions predict pain-related disability and mood in chronic orofacial pain patients? A 6-month follow-up study . Eur. J. Pain 14 , 550–558. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.08.011, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaston L., Thompson L., Gallagher D., Cournoyer L. G., Gagnon R. (1998). Alliance, technique, and their interactions in predicting outcome of behavioral, cognitive, and brief dynamic therapy . Psychother. Res. 8 , 190–209. [ Google Scholar ]